Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

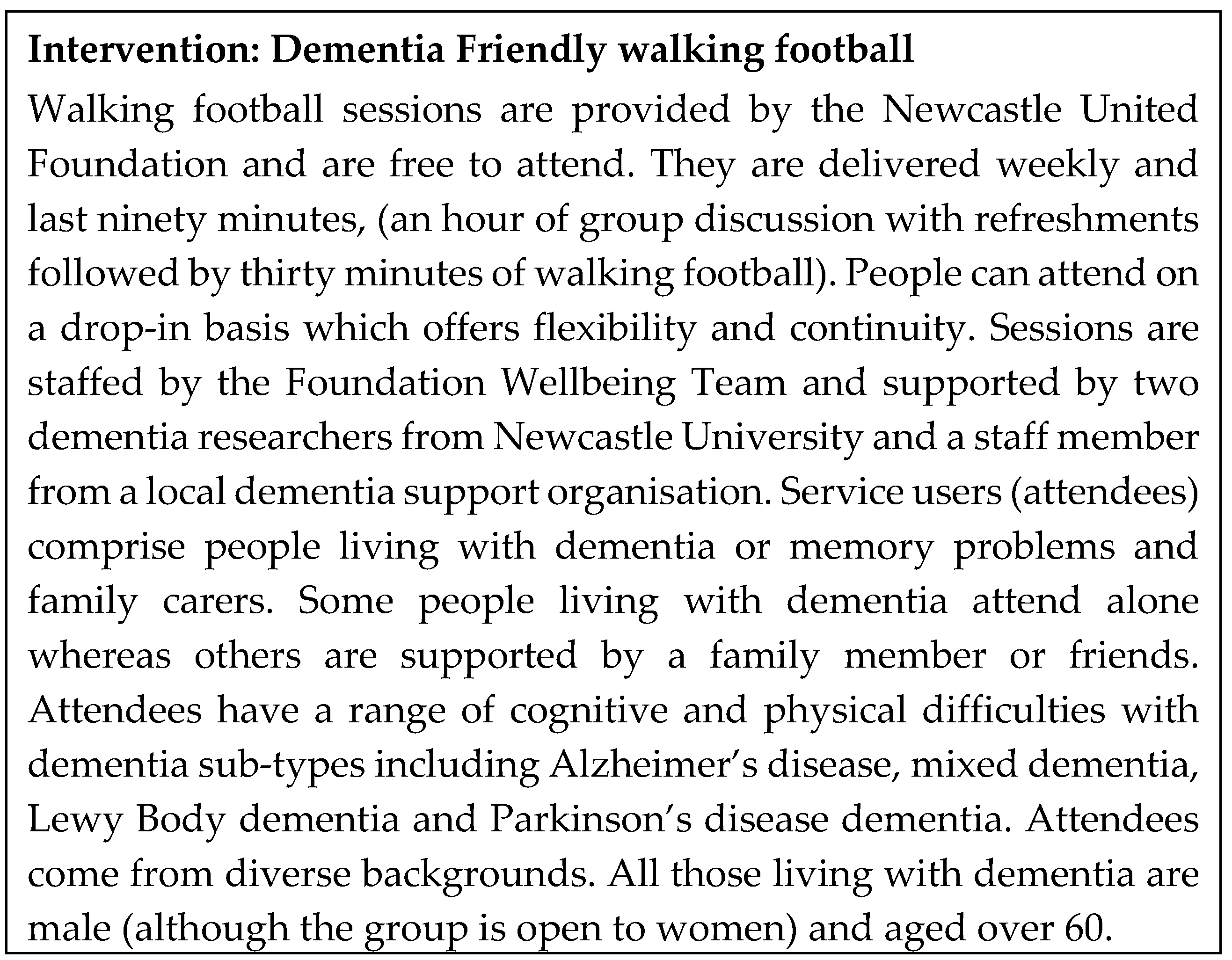

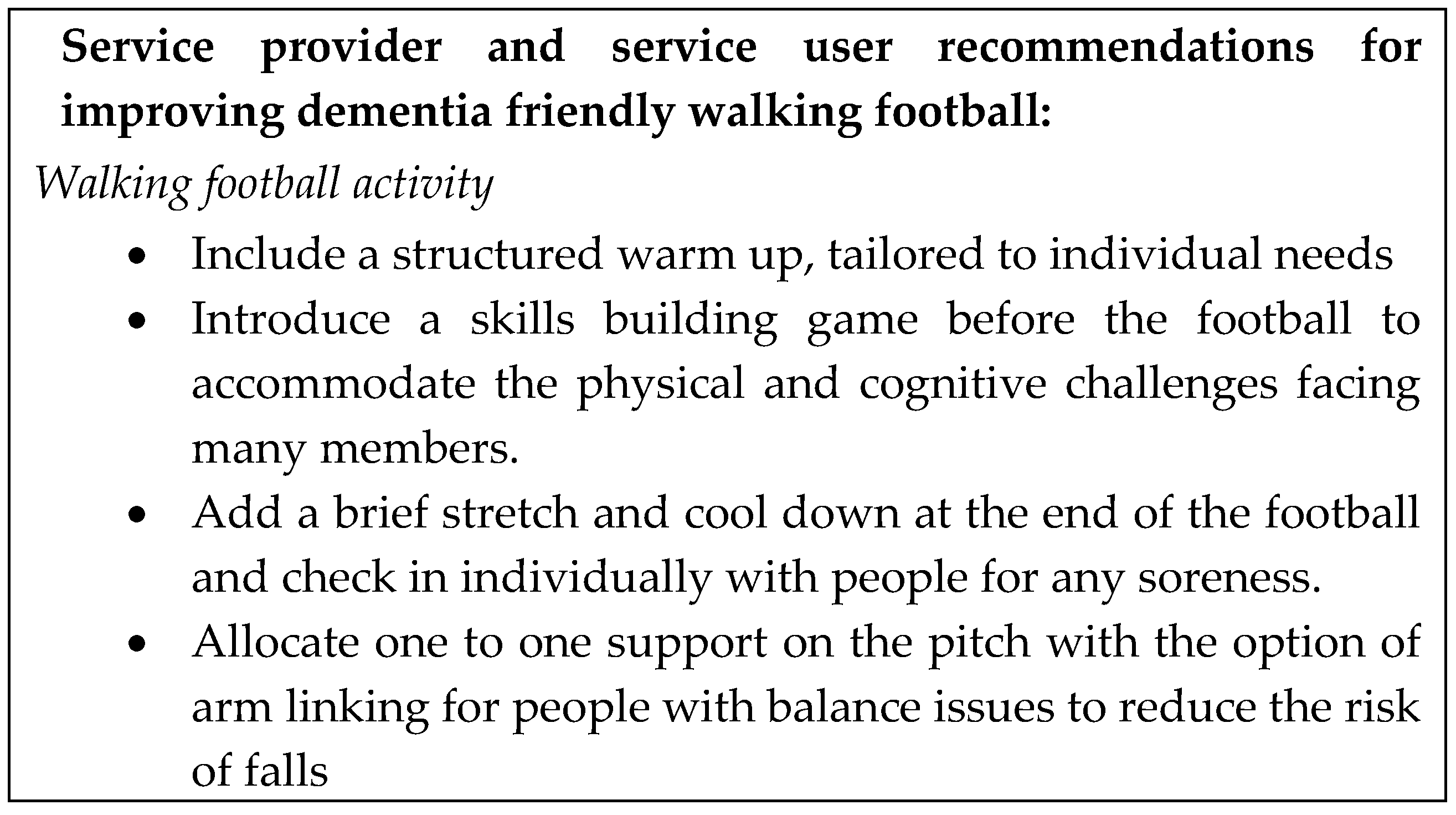

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

Theme 1. For the Love of the Game

"Football is more than a game; it is a passion. It is something that comes from inside and touches people's hearts." - Yaya Touré

Theme 2. Team Players

"I am constantly being asked about individuals. The only way to win is as a team." – Pelé

Theme 3. To Be the Best

“My game is based on improvisation. Often a forward does not know what he will do until he sees the defenders’ reactions.” - Ronaldinho

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARC | Applied Research Collaboration |

| EFPN | European Football Development Network |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| NIHR | National Institute for Health and Care Research |

| UK | United Kingdom |

References

- Telenius, E.W., G. G. Tangen, S. Eriksen, and A.M.M. Rokstad, Fun and a meaningful routine: the experience of physical activity in people with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer's Society. Physical activity, movement and exercise for people with dementia. [21.03.2025]. Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/daily-living/exercise.

- Nuzum, H. , et al., Potential benefits of physical activity in MCI and dementia. Behav. Neurol. 2020, 2020, 7807856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, Y.A. , et al., Dementia patients are more sedentary and less physically active than age-and sex-matched cognitively healthy older adults. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2018, 46, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, N. , et al., Barriers, motivators and facilitators of physical activity in people with dementia and their family carers in England: dyadic interviews. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walking Football World. Play walking football. 2023 [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://walkingfootballworld.com/play-walking-football.

- Bailey, L. , Still in the game: The rapid rise of walking football – in pictures, in The Guardian. 2023.

- The Walking Football Association. What is Walking Football? 2023, [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://thewfa.co.uk/.

- Andersson, H.; et al. Walking football for Health–physiological response to playing and characteristics of the players. Science and medicine in football 2025, 9, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences Medicine. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system; National Academies Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson's, UK. Walking Football. [21.03.2025]. Available online: https://localsupport.parkinsons.org.uk/activity/walking-football.

- Newcastle United Foundation. Newcastle United Foundation launches walking football programme for head injury survivors. 21.03.2025]. Available online: https://www.nufoundation.org.uk/news/newcastle-united-foundation-launches-walking-football-programme-for-head-injury-survivors.

- Prince, M. , et al., World Alzheimer Report 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. 2015, Alzheimer's Disease International.

- Ahmadi-Abhari, S. , et al., Temporal trend in dementia incidence since 2002 and projections for prevalence in England and Wales to 2040: modelling study. BMJ 2017, 358. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, B., L. Zheng, S. Kootar, and K.J. Anstey, Sex and gender differences in risk scores for dementia and Alzheimer's disease among cisgender, transgender, and non-binary adults. Alzheimer's Dement. 2024, 20, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, E.; Coughlin, D.G.; Banks, S.J.; Litvan, I. Sex differences for phenotype in pathologically defined dementia with Lewy bodies. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2021, 92, 745–750. [Google Scholar]

- Giebel, C. , et al., A systematic review on inequalities in accessing and using community-based social care in dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Giebel, C. and B. Heath, A 3-UK-nation survey on dementia and the cost of living crisis: contributions of gender and ethnicity on struggling to pay for social care. Aging Ment. Health 2023, 27, 2368–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.M., A. Killett, and E. Mioshi, What factors predict family caregivers’ attendance at dementia cafés? J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2018, 64, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solari, C.A. and L. Solomons, The World Cup effect: Using football to engage men with dementia. Dementia, 2012, 11, 699–702. [Google Scholar]

- Tolson, D. and I. Schofield, Football reminiscence for men with dementia: lessons from a realistic evaluation. Nurs. Inq. 2012, 19, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, N.J., A. Parker, and S. Swain, Sport, theology, and dementia: reflections on the sporting memories network, UK, in Theology, Disability and Sport. 2020, Routledge. p. 121-135.

- Williams, J. , A game for rough girls?: a history of women's football in Britain. 2013: Routledge.

- Caspers, A. , et al., Walking Football for Men and Women 60+: A 12-Week Non-Controlled Intervention Affects Health Parameters. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 2025: p. 1-13.

- Madsen, M. , Krustrup, and M.N. Larsen, Exercise intensity during walking football for men and women aged 60+ in comparison to traditional small-sided football–a pilot study. Manag. Sport Leis. 2021, 26, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, R., E. MacRae, and L. Carlin, Modifying walking football for people living with dementia: lessons for best practice. Sport Soc. 2022, 25, 1405–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carone, L., V. Tischler, and T. Dening, Football and dementia: A qualitative investigation of a community based sports group for men with early onset dementia. Dementia 2016, 15, 1358–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. and A. Pringle, Investigating the effect of walking football on the mental and social wellbeing of men. Soccer Soc. 2022, 23, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.M. , ‘It’s lovely to have that sense of belonging’: older men’s involvement in walking football. Leisure Studies, 2024: p. 1-13.

- Russell, C., G. Z. Kohe, D. Brooker, and S. Evans, Sporting identity, memory, and people with dementia: Opportunities, challenges, and potential for oral history. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2019, 36, 1157–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, M. Working together for vital community dementia support through football. 2024 [cited 2024 24.07.2024]. Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/blog/working-together-vital-community-dementia-support-through-football.

- Hodgson, S., H. Hayes, Cubi-Molla, and M. Garau, Inequalities in Dementia: Unveiling the Evidence and Forging a Path Towards Greater Understanding. 2024, Office of Health Economics.

- Hospice Care North Northumberland. Our dementia support services. 2025, [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://www.hospicecare-nn.org.uk/dementia-support-services.

- Glasgow Life. Dementia Walking Football. 2025, [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://glasgowlife.sportsuite.co.uk/activity-finder/activity/dementia-walking-football.

- Right at Home. Dementia friendly football in Petersfield. 2023, [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://www.rightathome.co.uk/havant/news-item/dementia-walking-football/.

- Dunstable Town Football Club. DTFC Walking Football Partner with Tibbs Dementia. 2024, [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://www.dunstabletownfc.co.uk/post/dtfc-walking-football-partner-with-tibbs-dementia.

- Salford Age UK. Walking Football. [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/salford/about-us/walking-football/.

- Lincolnshire Football Association. Dementia Friendly Walking Football. 2023, [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://www.lincolnshirefa.com/news/2023/may/30/dementia-friendly-walking-football.

- Walking Football Scotland. Football Memories Scotland. 2023, [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://www.walkingfootballscotland.org/news/2023/12/20/football-memories-scotland.

- Newcastle United Foundation. Walking Football. 2025, [21.03.2025]. Available online: https://www.nufoundation.org.uk/get-involved/walking-football.

- Haringey Council, Haringey Future Services Co-Design: Dementia and Older People Day Opportunites.

- Brighton and Hove Albion Foundation. Walking football session is tackling impact of dementia. 2018, [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://bhafcfoundation.org.uk/walking-football-session-is-tackling-impact-of-dementia/.

- Foundation 92. Dementia Walking Sports & Activities Group. [10.01.25]. Available online: https://foundation92.co.uk/our-work/health-wellbeing/young-people-programmes-2-2/youth-clubs-2-2-2-2-2/.

- Dementia, UK. Brian's story: "Walking football has so many benefits for people living with dementia". [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://www.dementiauk.org/information-and-support/stories/brians-story-walking-football-has-so-many-benefits-for-people-living-with-dementia/.

- Stebbins, R.A. , Exploratory research in the social sciences. Vol. 48. 2001: Sage.

- Bowling, A. , Research methods in health: investigating health and health services. 2014: McGraw-hill education (UK).

- Department for Constitutional Affairs, The Mental Capacity Act 2005 Code of Practice. 2005, The Stationery Office: London.

- Braun, V. , et al., Doing reflexive thematic analysis, in Supporting research in counselling and psychotherapy: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research. 2023, Springer. p. 19-38.

- Johnson, R. Rosie Johnson Illustrates. [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://rosiejohnsonillustrates.com/.

- Wheatley, A. , et al., Implementing post-diagnostic support for people living with dementia in England: a qualitative study of barriers and strategies used to address these in practice. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer's Disease International, World Alzheimer Report 2022. Life after diagnosis: Navigating treatment, care and support. 2022, Alzheimer's Disease International: London.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. NICE guidance [NG97]. 2018.

- Coyle, C.E. and E. Dugan, Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J. Aging Health 2012, 24, 1346–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caddell, L.S. and L. Clare, Interventions supporting self and identity in people with dementia: A systematic review. Aging Ment. Health 2011, 15, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. Can dementia be prevented? 2023, [21.03.2025]. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dementia/about-dementia/prevention/#:~:text=Exercise%20and%20dementia&text=Older%20adults%20who%20do%20not,brisk%20walking%2C%20cycling%20or%20dancing.

- Department of Health and Social Care, Major conditions strategy: case for change and our strategic framework. 2023, Department of Health and Social Care.

- Hadley, R. Mathie, E. Pike, and C. Goodman, Physical Activity Inclusion in Dementia-Friendly Communities: A Mixed Methods Study. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity 2024, 32, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dementia UK, Moving for your mental health. 2024.

- Alzheimer's Society. Sport United Against Dementia [01.01.2025]. Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-involved/events-and-fundraising/sport-united-against-dementia-suad.

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Improvement Leaders’ Guide: Evaluating improvement. 2005, [10.01.2025]. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/ILG-1.5-Evaluating-Improvement.pdf.

- MacRae, R. Macrae, and L. Carlin, An Evaluation of the Social Impact of a Pilot Dementia Friendly Walking football Programme 2020, University of the West of Scotland.

- Health Innovation West of England and NIHR Applied Research Collaboration West. NHS Evaluation Toolkit. 2024, [28.03.2025]. Available online: https://nhsevaluationtoolkit.net/.

- Inside FIFA, Explaining the walking football phenomenon. 2019, FIFA.

- Dementia Austraila. 2024 12.12.2024. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/DementiaAustralia/posts/pfbid02ipLEn4PEhq9sDYhqwt16JJVsiAVJ26F4MwrpDn7vKrtgdtJwpymQYPkcaK8cst9Kl?rdid=tHSo7d7istTedkSu#.

- European Football for Development Network. 2025 [cited 07.04.2025]. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/EFDN.org/?locale=en_GB.

- Thomas, G.M. , The dark side of (later-life) leisure: the case of walking football. Leisure Sciences, 2024: p. 1-17.

| Focus group | Initial themes | Overarching themes |

| Service Users | More than just a game! - Meeting the need for dementia support | Theme 1. For the love of the game |

| Match ready – Motivation and prompts to attend | Theme 1. For the love of the game | |

| Local heroes – Foundation staff | Theme 2. Team players | |

| Team talk - Benefits and challenges of themed discussions | Theme 3. To be the best | |

| Game plan - Identifying challenges and finding solutions | Theme 3. To be the best | |

| Service Providers | United - Meeting the need for dementia support | Theme 1. For the love of the game |

| Supporters club - Positive interactions for people living with dementia | Theme 1. For the love of the game | |

| Local heroes - Personal impact | Theme 1. For the love of the game | |

| Team players - Experience and knowledge of dementia and team skills; benefits to staff team | Theme 2. Team players | |

| Team tactics - Planning the sessions | Theme 2. Team players | |

| A game of two halves - Progression and adaptations | Theme 3. To be the best | |

| Next season – Future plans | Theme 3. To be the best |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. Dr Marie Poole’s research is jointly funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) North East and North Cumbria (NIHR200173) and Newcastle University. Dr Alison Killen’s research is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). Professor Dame Louise Robinson’s research is funded by the NIHR. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).