Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

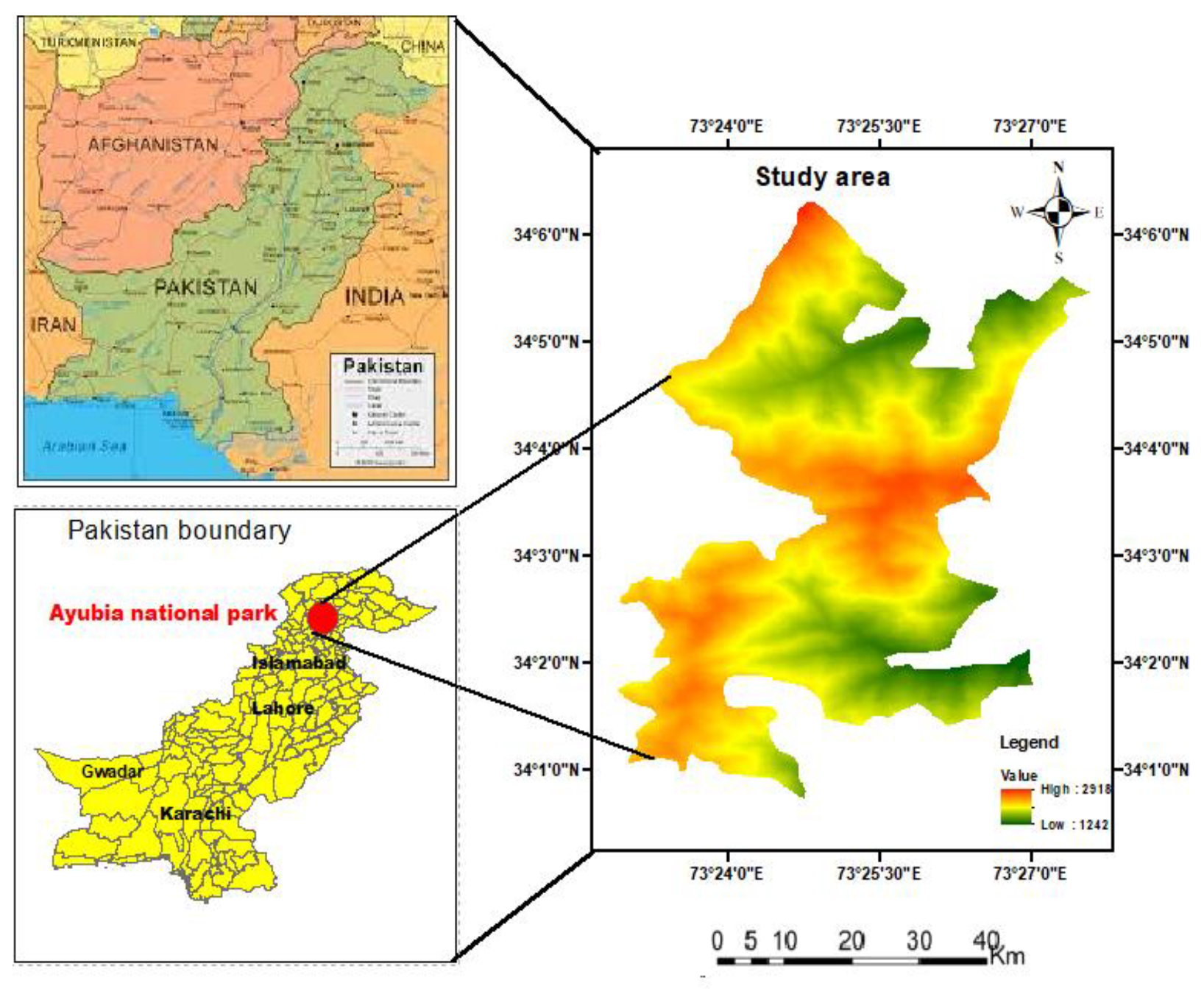

2.1. Study Area

2.1. Data Acquisition

2.1. Land-Use Classification

| Serial no | LULC Classes | Descrption |

| 1 | Bare Land | A land with no vegetation or grasses |

| 2 |

Conifer forest | Trees that grow needles instead of leaves and cones instead of flowers conifers tend to be evergreen they bear needles all year long. |

| 3 |

Built-up/Settlements | Includes residential areas like town, roads,villages,strip transportation and commercial areas |

| 4 |

Grassland | A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominated by grasses with flat large area |

| 5 |

Mixed Forest | Mixed forest is a vegetation type dominated by a mixture of broadleaf trees and shadow conifers. |

2.1. Image Pre-Processing

2.1. Image Classification and Accuracy

2.6. Markov Chain Model

2.7. Land Use Change Analysis

2.7. Biomass Carbon Change

2.9. Carbon Loss Assessment

3. Results and Analysis

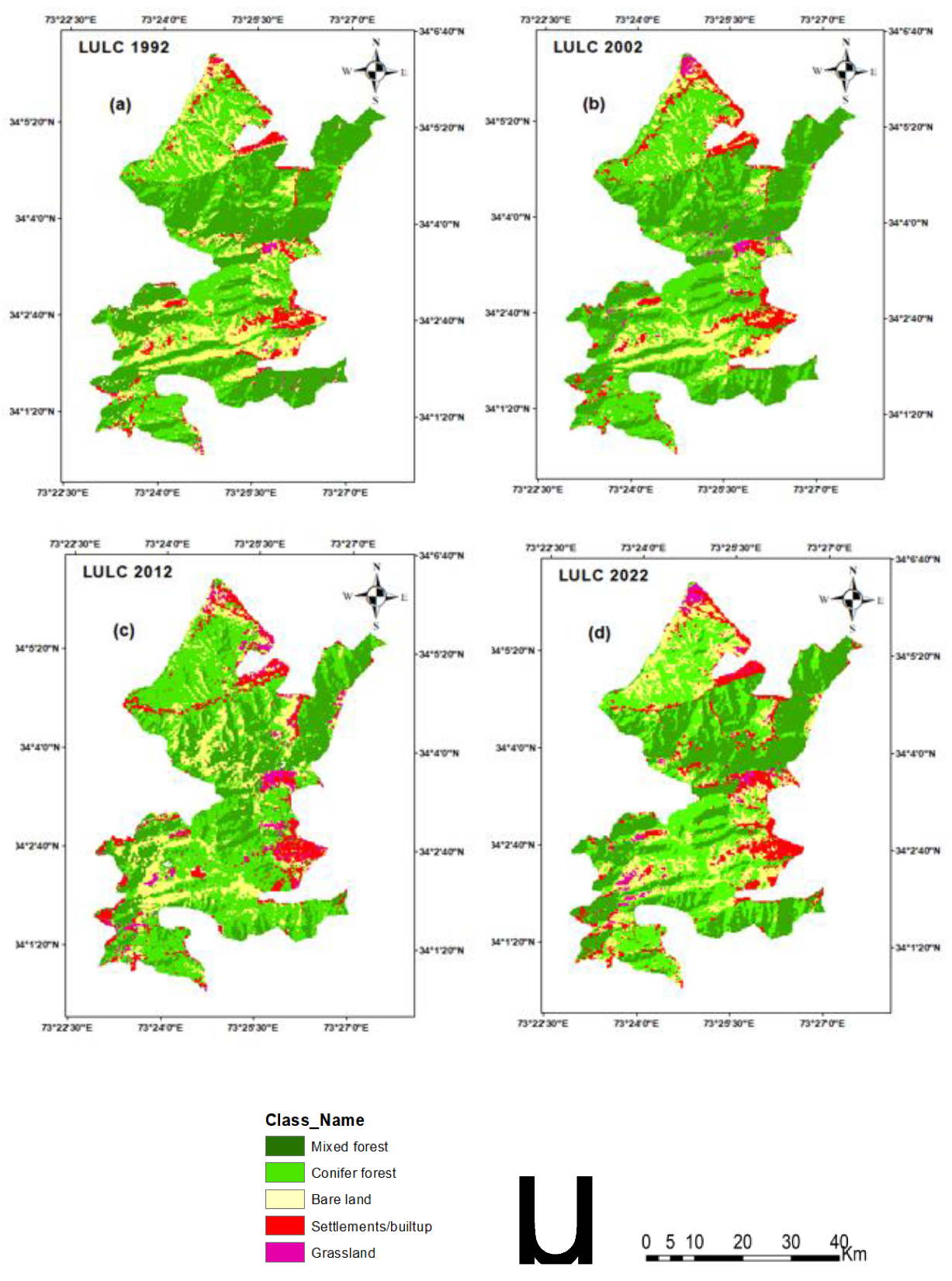

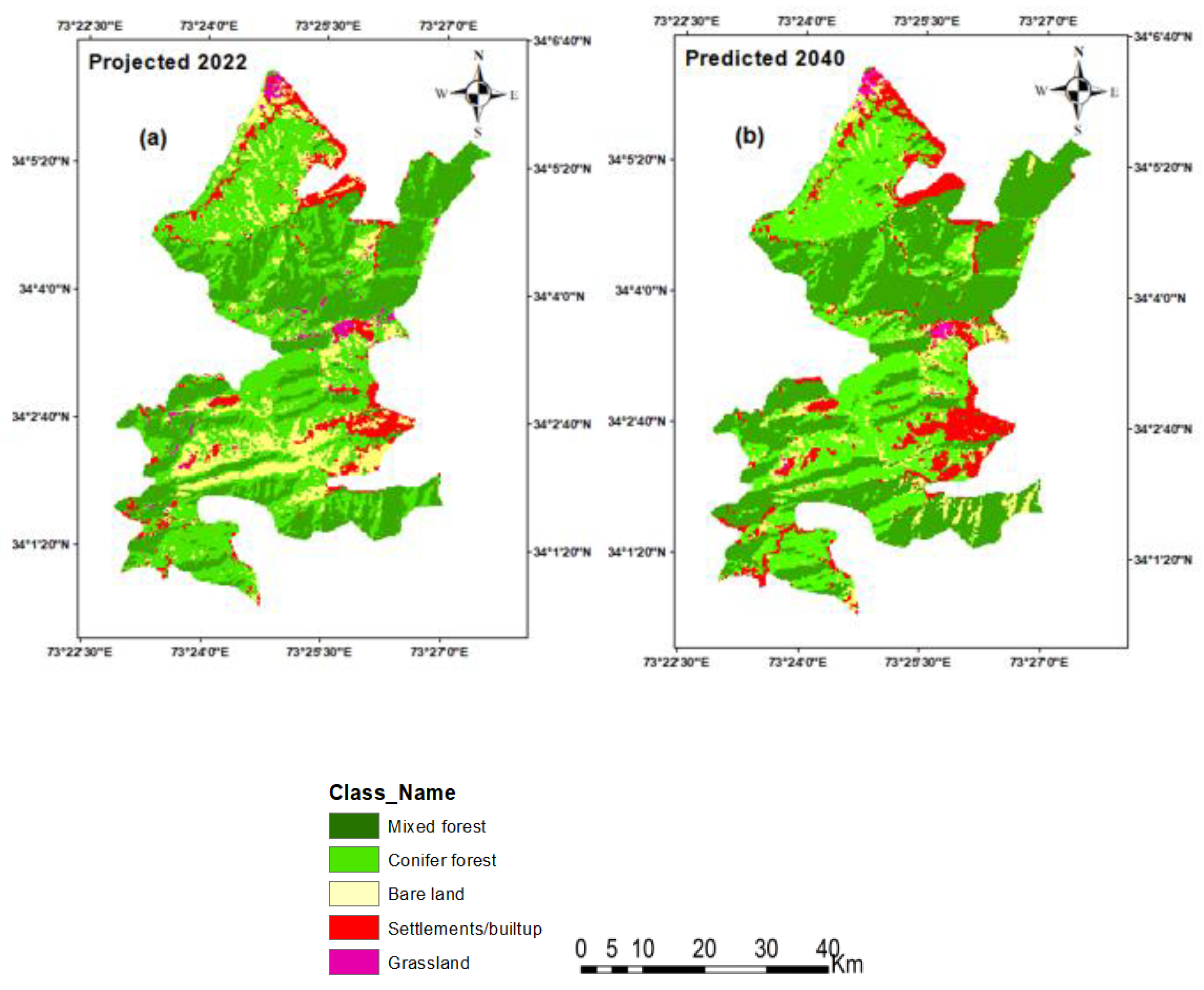

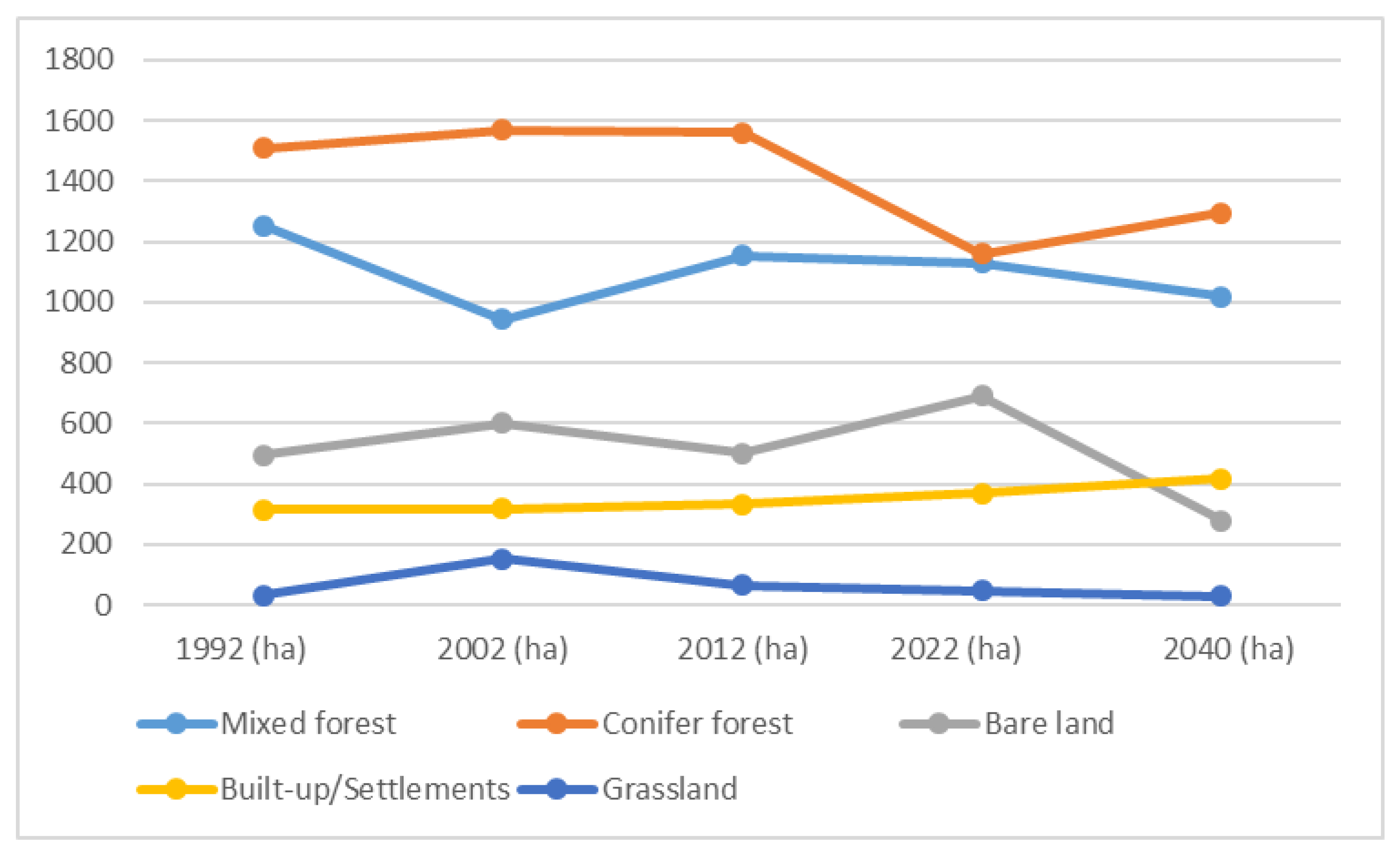

3.1. Land Use Land Change Analysis

| Land use categories | 1992-2002 change (%) | Annual change (%) | 2002-2012 change (%) | Annual change (%) | 2012-2022 change (%) | Annual change (%) | 2022-2040 change (%) | Annual change (%) |

| Mixed forest | -16.7 | -0.167 | +10.49 | +0.104 | +18.3 | +0.183 | +16.47 | +0.164 |

| Conifer forest | +3.98 | +0.039 | -0.65 | -0.0065 | -25.57 | -0.255 | +11.57 | +0.11 |

| Bare land | +25.7 | +0.257 | -14.6 | -0.146 | +30.07 | +0.30 | -59.4 | - 0.59 |

| Built-up/settlements | +0.92 | +0.09 | -10.12 | -0.101 | +13.80 | +0.138 | +34.18 | +0.341 |

| Grassland | +65.3 | +0.653 | +25.62 | +0.256 | -29.00 | -0.290 | -41.04 | -0.410 |

| Land use type | Land use changes to other land uses | Area change (ha) (1992-2022) | Total area change (ha) |

| Conifer forest | Bare land | 104.94 | 472.95 |

| Mixed forest | 241.92 | ||

| Settlement | 126.09 | ||

| Mix forest | Bare land | 7.740 | 61.7 |

| Settlements | 5.490 | ||

| Conifer forest | 48.51 | ||

| Built-up/Settlements | Mixed forest | 0.81 | 29.34 |

| Bare land | 22.86 | ||

| Grassland | 5.67 | ||

| Grassland | Conifer forest | 2.340 | 25.11 |

| Bare land | 14.40 | ||

| Settlements | 8.37 | ||

3.1. Accuracy Assessment of LULCC

| Classified map |

Overall Accuracy |

Kappa Coefficient |

| LULC map 1992 |

86.81 % |

0.845 |

| LULC map 2002 |

89.43% |

0.862 |

| LULC map 2012 |

90.43% |

0.873 |

| LULC map 2022 |

94.08% |

0.928 |

| Agreement/Disagreement (%) | |

|---|---|

| Allocation disagreement | 7.45 |

| Quantity disagreement | 5.16 |

| Allocation agreement | 14.95 |

| Quantity agreement | 62.10 |

| Chance agreement | 10.34 |

| Probability to change from-to | |||||

| Mixed forest | Conifer forest | Bare land | Built-up/Settlements | Grassland | |

| Mixed forest | 0.8836 | 0.1014 | 0.0108 | 0.0030 | 0.0012 |

| Conifer forest | 0.2726 | 0.6831 | 0.0367 | 0.0006 | 0.0071 |

| Bare land | 0.1178 | 0.2279 | 0.5990 | 0.0082 | 0.0471 |

| Builtup/Settlements | 0.0012 | 0.4710 | 0.1765 | 0.2796 |

0.0718 |

| Grassland | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.7272 | 0.0000 | 0.2728 |

| |

|||||

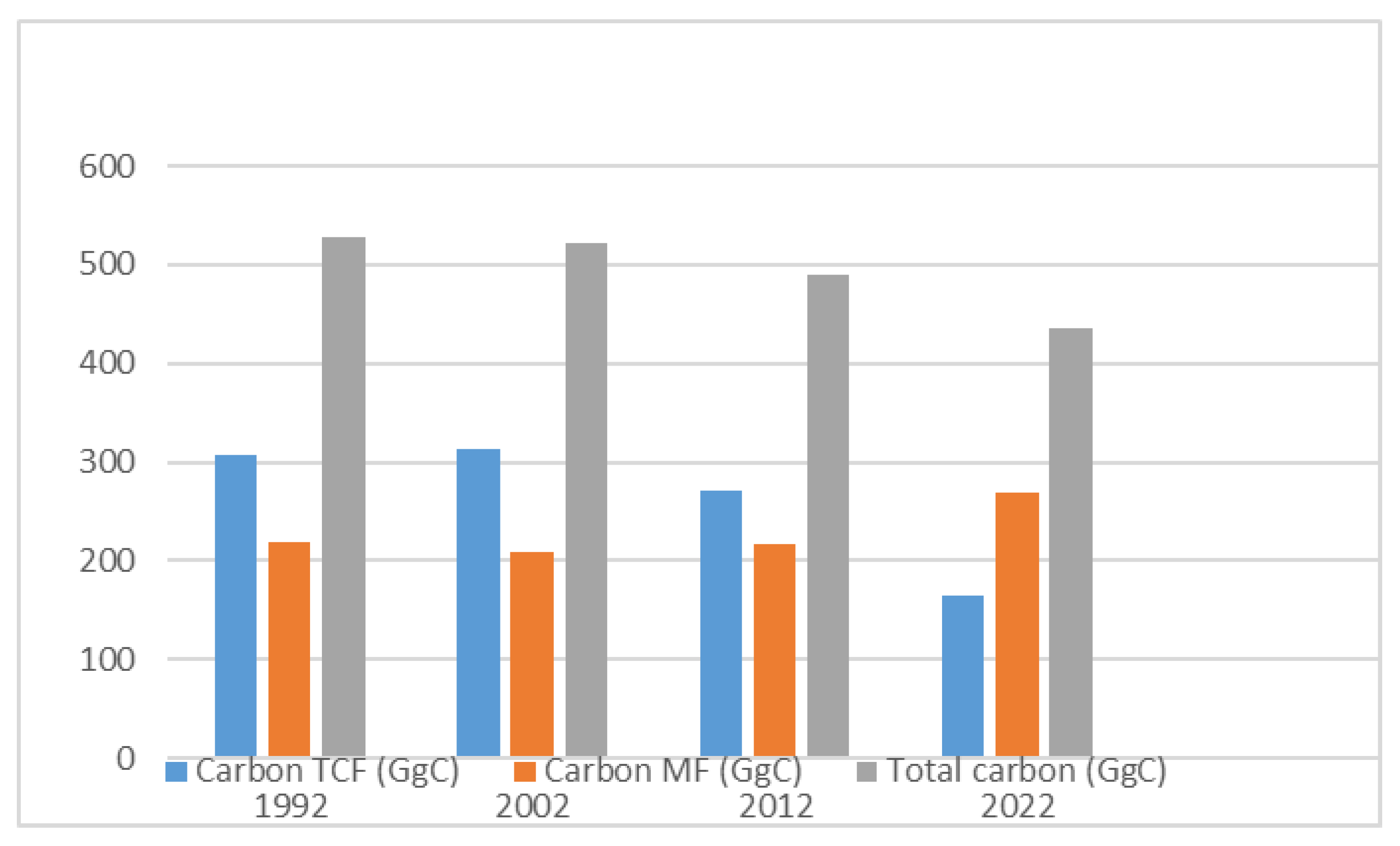

3.3. Carbon Dynamics

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Land Use Land Cover and Carbon Change

5. Conclusion

Availability of data and materials

Funding

Conflict of interest

References

- Hassan, Z., R. Shabbir, S. S. Ahmad, A. H. Malik, N. Aziz, A. Butt and S. Erum (2016). "Dynamics of land use and land cover change (LULCC) using geospatial techniques: a case study of Islamabad Pakistan." SpringerPlus 5(1): 812.

- Winkler, K., R. Fuchs, M. Rounsevell and M. Herold (2021). "Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated." Nature Communications 12(1): 2501.

- Tewabe, D. and T. Fentahun (2020). "Assessing land use and land cover change detection using remote sensing in the Lake Tana Basin, Northwest Ethiopia." Cogent Environmental Science 6(1): 1778998.

- Lambin, E.., & Ehrlich, D. (1997). Land Cover Changes in Sub-Saharan Africa (1982-1991): Application of a Change Index Based on Remotely Sensed Surface Temperature and Vegetation Indices at a Continental Scale. Remote Sensing of Environment, 61, 181-200. [CrossRef]

- Gondwe, J. F., S. Lin and R. M. Munthali (2021). "Analysis of Land Use and Land Cover Changes in Urban Areas Using Remote Sensing: Case of Blantyre City." Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society 2021: 8011565.

- Abebe, G., D. Getachew and A. Ewunetu (2021). "Analysing land use/land cover changes and its dynamics using remote sensing and GIS in Gubalafito district, Northeastern Ethiopia." SN Applied Sciences 4(1): 30.

- Kumar, S. and S. Arya (2021). "Change Detection Techniques for Land Cover Change Analysis Using Spatial Datasets: a Review." Remote Sensing in Earth Systems Sciences 4(3): 172-185.

- Ahmad, A. and S. M. Nizami (2015). "Carbon stocks of different land uses in the Kumrat valley, Hindu Kush Region of Pakistan." Journal of forestry research 26: 57-64.

- Reis, S. (2008). "Analyzing Land Use/Land Cover Changes Using Remote Sensing and GIS in Rize, North-East Turkey." Sensors (Basel) 8(10): 6188-6202. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A., Pariva, R. Badola and S. A. Hussain (2012). "A review of protocols used for assessment of carbon stock in forested landscapes." Environmental Science & Policy 16: 81-89.

- Sun, W. and X. Liu (2019). "Review on carbon storage estimation of forest ecosystem and applications in China." Forest Ecosystems 7(1): 4.

- Nandal, A., S. S. Yadav, A. S. Rao, R. S. Meena and R. Lal (2023). "Advance methodological approaches for carbon stock estimation in forest ecosystems." Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 195(2): 315.

- Song, X.-D., F. Yang, G.-L. Zhang (2021). "Significant loss of soil inorganic carbon at the continental scale." National Science Review 9(2).

- Ahmad, S. S. and S. Javed (2007). "Exploring the economic value of underutilized plant species in Ayubia National Park." Pakistan Journal of Botany 39(5): 1435-1442.

- Rukya, S.A., Rashid, F., Rashid, A., Mahmood, T., Nisa, W., 2014. Impact of population dynamics on Margalla hills ecosystem: A community-level case study. Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment 12 (4), 345e353.

- Mannan, M. A., et al. (2009). "Impacts of land-use change on biodiversity and ecosystem services in tropical Asia." Journal of Environmental Management, 90(1), 326-343.

- Saeed, S., et al. (2016). "Impacts of land use/land cover change on climate and future research priorities." Environmental Reviews, 24(4), 462-484. This review likely covers the impacts of LULCC on climate, including its effects on carbon dynamics in forests.

- Khan, I. A., W. R. Khan, A. Ali and M. Nazre (2021). "Assessment of above-ground biomass in pakistan forest ecosystem’s carbon pool: A review." Forests 12(5): 586.

- Waseem, M., I. Mohammad, S. Khan, S. Haider and S. K. Hussain (2005). "Tourism and solid waste problem in Ayubia National Park, Pakistan (a case study, 2003–2004)." Peshawar, Pakistan: WWF–P Nathiagali office.

- Lambin, E. F., H. J. Geist and E. Lepers (2003). "Dynamics of land-use and land-cover change in tropical regions." Annual review of environment and resources 28(1): 205-241.

- Musetsho, K. D., M. Chitakira and W. Nel (2021). "Mapping Land-Use/Land-Cover Change in a Critical Biodiversity Area of South Africa." Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(19).

- Rijal, S., B. Rimal, R. P. Acharya and N. E. Stork (2021). "Land use/land cover change and ecosystem services in the Bagmati River Basin, Nepal." Environ Monit Assess 193(10): 651.

- Weng Q (2002) A remote sensing-GIS evaluation of urban expansion and its impacts on temperature in the Zhujang Delta, China. Int J Remote Sens 22(10):1999–2014.

- Araya, Y. H., & Cabral, P. (2009). "Assessing the impacts of land use/land cover change on ecosystem services: The role of future scenarios and spatial configuration." Applied Geography, 29(4), 577-590.

- Damjan, V. V., & Kilibarda, M. (2009). "Analysis of land use and land cover changes using Markov chain model in Belgrade region." Journal of the Geographical Institute "Jovan Cvijić" SASA, 59(2), 109-121.

- Williams, D. R., B. Phalan, C. Feniuk, R. E. Green and A. Balmford (2018). "Carbon Storage and Land-Use Strategies in Agricultural Landscapes across Three Continents." Curr Biol 28(15): 2500-2505.e2504.

- Woltz, V. L., E. I. Peneva-Reed, Z. Zhu, E. L. Bullock, R. A. MacKenzie, M. Apwong, K. W. Krauss and D. B. Gesch (2022). "A comprehensive assessment of mangrove species and carbon stock on Pohnpei, Micronesia." PLoS One 17(7): e0271589.

- Zeng, L., X. Liu, W. Li, J. Ou, Y. Cai, G. Chen, M. Li, G. Li, H. Zhang and X. Xu (2022). "Global simulation of fine resolution land use/cover change and estimation of aboveground biomass carbon under the shared socioeconomic pathways." J Environ Manage 312: 114943.

- Zhou, Y., A. E. Hartemink, Z. Shi, Z. Liang and Y. Lu (2019). "Land use and climate change effects on soil organic carbon in North and Northeast China." Sci Total Environ 647: 1230-1238.

- Olorunfemi, I. E., A. A. Komolafe, J. T. Fasinmirin and A. A. Olufayo (2019). "Biomass carbon stocks of different land use management in the forest vegetative zone of Nigeria." Acta Oecologica 95: 45-56.

- Rashid, I., M. A. Bhat and S. A. Romshoo (2017). "Assessing changes in the above ground biomass and carbon stocks of Lidder valley, Kashmir Himalaya, India." Geocarto international 32(7): 717-734.

- Morreale, L. L., J. R. Thompson, X. Tang, A. B. Reinmann and L. R. Hutyra (2021). "Elevated growth and biomass along temperate forest edges." Nat Commun 12(1): 7181.

- Amir, A., S. Muhammad, H. Nawaz, M. Tayyab, U. F. Awan, K. Rasool and K. Zaheer-ud-din (2022). "Growth response of four dominant conifer species in moist temperate region of Pakistan (Ayubia National Park)." Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 50(2): 12674-12674.

- Malik, A., & Ali, S. (2019). "Impacts of land-use change on carbon dynamics in forest ecosystems: A review." Forest Ecology and Management, 430, 206-222.

- Ahmad, S., & Javed, M. (2008). "Land use/land cover change detection and its impact on carbon stock using remote sensing and GIS techniques." Journal of Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 142(1-3), 297-310.

- Avtar, R., K. Tsusaka and S. Herath (2020). "Assessment of forest carbon stocks for REDD+ implementation in the muyong forest system of Ifugao, Philippines." Environ Monit Assess 192(9): 571.

- Gandhi, D. S. and S. Sundarapandian (2017). "Large-scale carbon stock assessment of woody vegetation in tropical dry deciduous forest of Sathanur reserve forest, Eastern Ghats, India." Environ Monit Assess 189(4): 187.

- MohanRajan, S. N., A. Loganathan and P. Manoharan (2020). "Survey on Land Use/Land Cover (LU/LC) change analysis in remote sensing and GIS environment: Techniques and Challenges." Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 27(24): 29900-29926.

- Núñez-Regueiro, M. M., S. F. Siddiqui and R. J. Fletcher, Jr. (2021). "Effects of bioenergy on biodiversity arising from land-use change and crop type." Conserv Biol 35(1): 77-87.

- Ohler, K., V. C. Schreiner, M. Link, M. Liess and R. B. Schäfer (2023). "Land use changes biomass and temporal patterns of insect cross-ecosystem flows." Glob Chang Biol 29(1): 81-96.

- Iqbal, M. F. and I. A. Khan (2014). "Spatiotemporal land use land cover change analysis and erosion risk mapping of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan." the Egyptian journal of remote sensing and space science 17(2): 209-229.

- Hao, S., F. Zhu and Y. Cui (2021). "Land use and land cover change detection and spatial distribution on the Tibetan Plateau." Scientific Reports 11(1): 7531.

- Jiyuan, L., L. Mingliang, D. Xiangzheng, Z. Dafang, Z. Zengxiang and L. Di (2002). "The land use and land cover change database and its relative studies in China." Journal of Geographical Sciences 12: 275-282.

- Justice, C., G. Gutman and K. P. Vadrevu (2015). "NASA Land Cover and Land Use Change (LCLUC): an interdisciplinary research program." J Environ Manage 148: 4-9.

- Tao, F., et al. (2015). "Global warming, climate change, and land use and land cover change: A review." Journal of Advanced Research, 6(6), 759-765.

- Li, X., et al. (2020). "Impacts of land use and land cover change on ecosystem services: A review." Journal of Geographical Sciences, 30(5), 689-709.

- Xiang, Z., et al. (2022). "Assessing the effects of land use and land cover change on carbon dynamics in tropical forests: A case study in Southeast Asia." Forest Ecology and Management, 509, 119464.

- Kauffman, J. B., R. F. Hughes and C. Heider (2009). "Carbon pool and biomass dynamics associated with deforestation, land use, and agricultural abandonment in the neotropics." Ecol Appl 19(5): 1211-1222.

- Lambin, E. F., B. L. Turner, H. J. Geist, S. B. Agbola, A. Angelsen, J. W. Bruce, O. T. Coomes, R. Dirzo, G. Fischer, C. Folke, P. S. George, K. Homewood, J. Imbernon, R. Leemans, X. Li, E. F. Moran, M. Mortimore, P. S. Ramakrishnan, J. F. Richards, H. Skånes, W. Steffen, G. D. Stone, U. Svedin, T. A. Veldkamp, C. Vogel and J. Xu (2001). "The causes of land-use and land-cover change: moving beyond the myths." Global Environmental Change 11(4): 261-269.

- Li, X. L., L. X. Yang, W. Tian, X. F. Xu and C. S. He (2018). "Land use and land cover change in agro-pastoral ecotone in Northern China: A review." Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao 29(10): 3487-3495.

- Luo, M., G. Hu, G. Chen, X. Liu, H. Hou and X. Li (2022). "1 km land use/land cover change of China under comprehensive socioeconomic and climate scenarios for 2020-2100." Sci Data 9(1): 110.

- Reis, S. (2008). "Analyzing Land Use/Land Cover Changes Using Remote Sensing and GIS in Rize, North-East Turkey." Sensors (Basel) 8(10): 6188-6202. [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, H., Khan, A., & Ahmed, M. (2018). "Impact of Land Use and Land Cover Change on Ecosystem Services: A Case Study." Journal of Environmental Management, 220, 165-175.

- Rokityanskiy, D., P. C. Benítez, F. Kraxner, I. McCallum, M. Obersteiner, E. Rametsteiner and Y. Yamagata (2007). "Geographically explicit global modeling of land-use change, carbon sequestration, and biomass supply." Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74(7): 1057-1082.

- Ahmad, S., et al. (2017). "Assessment of Land Use/Land Cover Change and Forest Fragmentation in Peshawar Valley Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques." Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 189(8), 400.

- Ahmad, A., & Nizami, S. M. (2015). Carbon Stocks of Different Land Uses in the Kumrat Valley, Hindu Kush Region of Pakistan. Journal of Forest Research, 26, 57-64.

- Sasmito, S. D., P. Taillardat, J. N. Clendenning, C. Cameron, D. A. Friess, D. Murdiyarso and L. B. Hutley (2019). "Effect of land-use and land-cover change on mangrove blue carbon: A systematic review." Glob Chang Biol 25(12): 4291-4302.

- Tan, L. S., Z. M. Ge, S. H. Li, K. Zhou, D. Y. F. Lai, S. Temmerman and Z. J. Dai (2023). "Impacts of land-use change on carbon dynamics in China's coastal wetlands." Sci Total Environ 890: 164206.

- Tiwari, S., C. Singh, S. Boudh, P. K. Rai, V. K. Gupta and J. S. Singh (2019). "Land use change: A key ecological disturbance declines soil microbial biomass in dry tropical uplands." J Environ Manage 242: 1-10.

- de Groot, R. S., et al. (2009). "Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making." Ecological Complexity, 7(3), 260-272.

| Sensor | Year | Date | Image Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landsat 8 OLI . (Path/Row:150/36, 150/37) |

2022 |

17/10/2022 |

30m |

| | |||

| Landsat 5 Imagery (Path/Row:150/36,150/37) |

2012 |

14/07/2012 | 30m |

| | |||

| Landsat 5 Imagery (Path/Row:150/36, 150/37) |

2002 |

25/09/2002 | 30m |

| | |||

| Landsat 5 TM imagery (Path/Row:150/36, 150/37) |

1992 | 20/09/1992 | 30m |

| Land use | 1992 (ha) | 2002 (ha) | 2012 (ha) | 2022 (ha) Projected 2022 | 2040 (ha) |

| Mixed forest | 1253.79 | 943.21 | 1152.74 | 1129.71 1102.9 | 1019.56 |

| Conifer forest | 1510.20 | 1570.32 | 1560.06 | 1161.09 1182.45 | 1295.45 |

| Bare land | 493.56 | 601.65 | 499.79 | 689.13 432.2 | 278.76 |

| Built-up/Settlements | 315.06 | 317.97 | 332.78 | 368.23 398.76 | 416.29 |

| Grassland | 31.6 | 152.37 | 65.79 | 46.71 34.6 | 27.54 |

| Carbon pool | Temperate conifer forest (MgC∙ha-1) | Mixed forest (MgC∙ha-1) |

| Above ground | 90.71 ±31.96 | 34.31 ±18.76 |

| Below ground | 1.93 ±0.22 | 1.53 ±0.48 |

| Litter and dead wood | 1.27 ±0.37 | 0.88 ±0.36 |

| Soil carbon | 49.72 ±9.47 | 46.24 ±8.92 |

| Total carbon | 135.19 ±9.74 | 86.43 ±8.25 |

| Temperate coniferous forest (ha) | Mixed forest (ha) | Carbon TCF (GgC) | Carbon MF (GgC) | Total carbon (GgC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1510.20 | 1253.79 | 308 | 219 | 527 |

| 2002 | 1570.32 | 943.21 | 313 | 209 | 522 |

| 2012 | 1560.06 | 1152.74 | 272 | 217 | 489 |

| 2022 | 1161.09 | 1019.56 | 165 | 270 | 435 |

| Total carbon loss/gain (MgC) | Net carbon loss (MgC) | Net annual carbon loss (MgC∙yr-1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCF | MF | |||

| 1992-2002 | 435.12 | -140 | 295.12 | 29.5 |

| 2002-2012 | 410 | +120 | 530 | 53.0 |

| 2012-2022 | 325 | 270 | 595 | 59.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).