Submitted:

26 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Creation of Genes for Wild Type and Mutant Shsps

HPLC-SEC

AUC Measurements

Protein Aggregation Measurements

Monomer–C-Terminal Domain Docking Simulation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MJsHsp | sHsp of Methanocaldococcus jannaschii with T33M mutation |

| MMsHsp | sHsp of Methanococcus maripaludis |

| HPLC-SEC | High-performance liquid chromatography size-exclusion chromatography (HPLC-SEC) |

| AUC | Analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) |

| CS | Citrate synthase from porcine heart |

| NMCJsHsp | MJsHsp with the N-terminal domain of MMsHsp |

| NJCMsHsp | MMsHsp with the N-terminal domain of MJsHsp |

| MJsHsp-Q36E | MJsHsp with Q36E mutation |

| MJsHsp-Q52E | MJsHsp with Q52E mutation |

| MJsHsp-E118G | MJsHsp with E118G mutation |

| MJsHsp-N145D | MJsHsp with N145D mutation |

| MMsHsp-E43Q | MMsHsp with E43Q mutation |

| MMsHsp-E59Q | MMsHsp with E59Q mutation |

| MMsHsp-G125E | MMsHsp with G125E mutation |

| MMsHsp-D152N | MMsHsp with D152N mutation |

| MMsHsp | MMsHsp with E43Q and D152N mutations |

| MJsHsp | MJsHsp with Q36E and N145D mutations |

| NJCMsHsp | NJCMsHsp with E43Q and D152N mutations |

| NMCJsHsp | NMCJsHsp with Q36E and N145D mutations |

| MMsHsp-3M | MMsHsp with E43Q, G125E and D152 mutations |

| MJsHsp-3M | MJsHsp with Q36E, E118G and N145D mutations |

| NMCJsHsp-3M | NMCJsHsp with Q36E, E118G and N145D mutations |

| MMsHsp-Chimera | A chimera sHsp of NMCJsHsp-3M and MMsHsp-3M |

| MMsHsp-3M-A94M | MMsHsp with E43Q, A94M, G125E and D152 mutations |

| MMsHsp-3M-M96T | MMsHsp with E43Q, M96T, G125E and D152 mutations |

| MJsHsp-3M-T89M | MJsHsp with Q36E, T89M and N145D mutations |

| MJsHsp-Cmut | MJsHsp with K141R, K142T and N145D mutations |

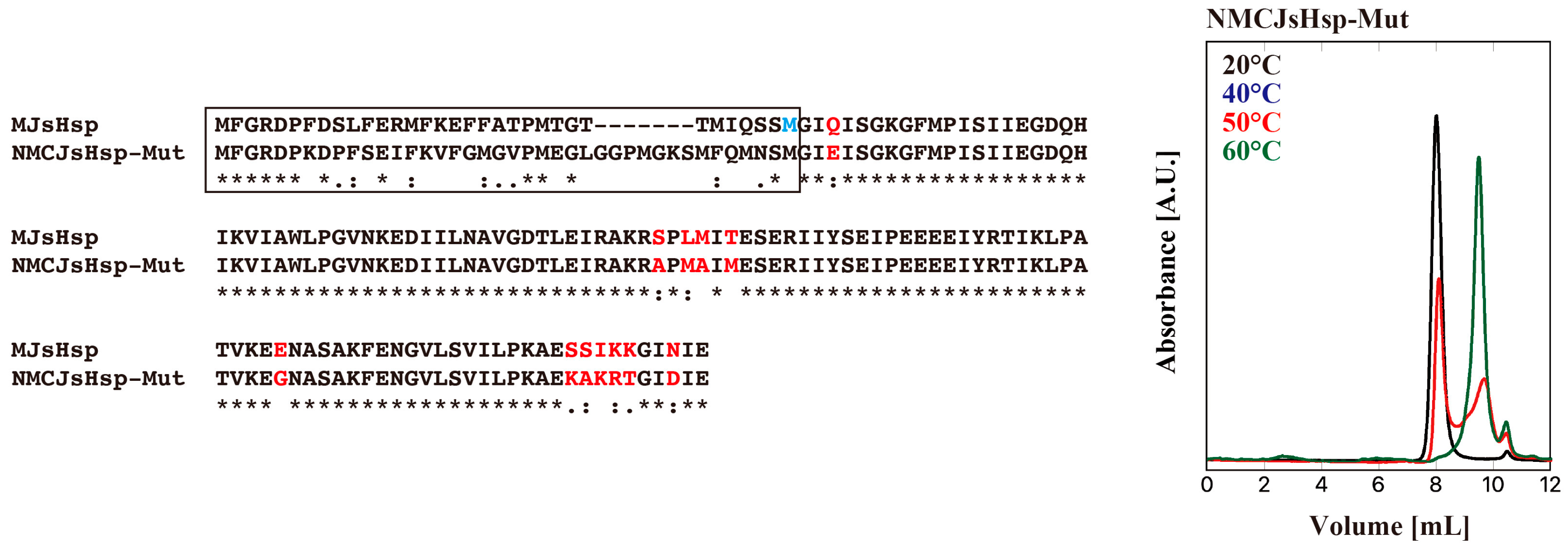

| NMCJsHsp-Mut | NMCJsHsp with Q36E, S84A, L86M, M87A, T89M, E118G, S138K, S139A, I140K, K141R, K142T and N145D mutations |

References

- Garrido, C.; Paul, C.; Seigneuric, R.; Kampinga, H.H. The small heat shock proteins family: The long forgotten chaperones. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 44, 1588–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakthisaran, R.; Tangirala, R.; Rao, C.M. Small heat shock proteins: Role in cellular functions and pathology. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Proteins Proteom. 2015, 1854, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspers, G. J.; Leunissen, J. A.; de Jong, W. W. , The expanding small heat-shock protein family, and structure predictions of the conserved "alpha-crystallin domain". J Mol Evol 1995, 40, (3), 238–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbecq, S.P.; Jehle, S.; Klevit, R. Binding determinants of the small heat shock protein, αB-crystallin: recognition of the ‘IxI’ motif. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 4587–4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanagopalan, I.; Degiacomi, M.T.; Shepherd, D.A.; Hochberg, G.K.A.; Benesch, J.L.P.; Vierling, E. It takes a dimer to tango: Oligomeric small heat shock proteins dissociate to capture substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 19511–19521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.K.; Kim, R.; Kim, S.-H. Crystal structure of a small heat-shock protein. Nature 1998, 394, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanazono, Y.; Takeda, K.; Yohda, M.; Miki, K. Structural Studies on the Oligomeric Transition of a Small Heat Shock Protein, StHsp14.0. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 422, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Montfort, R.L.M.; Basha, E.; Friedrich, K.L.; Slingsby, C.; Vierling, E. Crystal structure and assembly of a eukaryotic small heat shock protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2001, 8, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanazono, Y.; Takeda, K.; Oka, T.; Abe, T.; Tomonari, T.; Akiyama, N.; Aikawa, Y.; Yohda, M.; Miki, K. Nonequivalence Observed for the 16-Meric Structure of a Small Heat Shock Protein, SpHsp16.0, from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Structure 2012, 21, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckenstein, T.; Kastenmüller, A.; Stein, M.L.; Peters, C.; Daake, M.; Krause, M.; Weinfurtner, D.; Haslbeck, M.; Weinkauf, S.; Groll, M.; et al. The Chaperone Activity of the Developmental Small Heat Shock Protein Sip1 Is Regulated by pH-Dependent Conformational Changes. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappe, G.; Franck, E.; Verschuure, P.; Boelens, W. C.; Leunissen, J. A.; de Jong, W. W. , The human genome encodes 10 alpha-crystallin-related small heat shock proteins: HspB1-10. Cell Stress Chaperones 2003, 8, (1), 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, L.; Aguda, A.H.; Al Nakouzi, N.; Lelj-Garolla, B.; Beraldi, E.; Lallous, N.; Thi, M.; Moore, S.; Fazli, L.; Battsogt, D.; et al. Ivermectin inhibits HSP27 and potentiates efficacy of oncogene targeting in tumor models. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 130, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurokawa, N.; Midorikawa, R.; Nakamura, M.; Noguchi, K.; Morishima, K.; Inoue, R.; Sugiyama, M.; Yohda, M. Oligomeric Structural Transition of HspB1 from Chinese Hamster. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, M.; Tohda, H.; Giga-Hama, Y.; Tsushima, R.; Zako, T.; Iizuka, R.; Pack, C.; Kinjo, M.; Ishii, N.; Yohda, M. Interaction of a Small Heat Shock Protein of the Fission Yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, with a Denatured Protein at Elevated Temperature. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 32586–32593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzmann, T.M.; Wühr, M.; Richter, K.; Walter, S.; Buchner, J. The Activation Mechanism of Hsp26 does not Require Dissociation of the Oligomer. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 350, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Oka, T.; Nakagome, A.; Tsukada, Y.; Yasunaga, T.; Yohda, M. StHsp14.0, a small heat shock protein of Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7, protects denatured proteins from aggregation in the partially dissociated conformation. J. Biochem. 2011, 150, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostenko, S.; Moens, U. Heat shock protein 27 phosphorylation: kinases, phosphatases, functions and pathology. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 3289–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saji, H.; Iizuka, R.; Yoshida, T.; Abe, T.; Kidokoro, S.; Ishii, N.; Yohda, M. Role of the IXI/V motif in oligomer assembly and function of StHsp14.0, a small heat shock protein from the acidothermophilic archaeon, Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2007, 71, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Whitman, W.B. Metabolic, Phylogenetic, and Ecological Diversity of the Methanogenic Archaea. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2008, 1125, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.J.; Leigh, J.A.; Mayer, F.; Woese, C.R.; Wolfe, R.S. Methanococcus jannaschii sp. nov., an extremely thermophilic methanogen from a submarine hydrothermal vent. Arch. Microbiol. 1983, 136, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bult, C.J.; White, O.; Olsen, G.J.; Zhou, L.; Fleischmann, R.D.; Sutton, G.G.; Blake, J.A.; FitzGerald, L.M.; Clayton, R.A.; Gocayne, J.D.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of the Methanogenic Archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science 1996, 273, 1058–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Koteiche, H.A.; McDonald, E.T.; Fox, T.L.; Stewart, P.L.; Mchaourab, H.S. Cryoelectron Microscopy Analysis of Small Heat Shock Protein 16.5 (Hsp16.5) Complexes with T4 Lysozyme Reveals the Structural Basis of Multimode Binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 4819–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Ryu, B.; Kim, T.; Kim, K.K. Cryo-EM structure of a 16.5-kDa small heat-shock protein from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 258, 128763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.J.; Whitman, W.B.; Fields, R.D.; Wolfe, R.S. Growth and Plating Efficiency of Methanococci on Agar Media. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 46, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usui, K.; Hatipoglu, O.F.; Ishii, N.; Yohda, M. Role of the N-terminal region of the crenarchaeal sHsp, StHsp14.0, in thermal-induced disassembly of the complex and molecular chaperone activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 315, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.L.; Pei, G.K. Modification of a PCR-Based Site-Directed Mutagenesis Method. BioTechniques 1997, 23, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Cai, G.; Hall, E. O.; Freeman, G. J. , In-fusion assembly: seamless engineering of multidomain fusion proteins, modular vectors, and mutations. Biotechniques 2007, 43, (3), 354–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuck, P. Size-Distribution Analysis of Macromolecules by Sedimentation Velocity Ultracentrifugation and Lamm Equation Modeling. Biophys. J. 2000, 78, 1606–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MMsHsp | |||||||||||

| c [mg/mL] | f/f0 | Peak | s20,w [S] | M [kDa] | N | w [%] | |||||

| 1.0 | 1.46 | a | 2.37 | 34 | 2 | 16.8 | |||||

| b | 5.81 | 132 | 8 | 4.6 | |||||||

| c | 9.72 | 285 | 17 | 5.3 | |||||||

| d | 12.33 | 408 | 24 | 73.3 | |||||||

| 0.1 | 1.43 | a | 2.25 | 31 | 2 | 31.3 | |||||

| b | 5.81 | 128 | 8 | 4.2 | |||||||

| c | 10.31 | 303 | 18 | 10.9 | |||||||

| d | 12.44 | 402 | 24 | 53.6 | |||||||

| MJsHsp | |||||||||||

| c [mg/mL] | f/f0 | Peak | s20,w [S] | M [kDa] | N | w [%] | |||||

| 1.0 | 1.37 | a | 4.57 | 82 | 5 | 2.1 | |||||

| b | 7.62 | 176 | 11 | 1.7 | |||||||

| c | 8.97 | 225 | 14 | 2.0 | |||||||

| d | 12.87 | 386 | 23 | 38.7 | |||||||

| e | 16.08 | 540 | 33 | 8.8 | |||||||

| f | 18.45 | 663 | 40 | 27.6 | |||||||

| g | 22.01 | 864 | 52 | 12.1 | |||||||

| h | 25.39 | 1071 | 65 | 7.0 | |||||||

| 0.1 | 1.36 | a | 3.39 | 52 | 3 | 7.3 | |||||

| b | 5.76 | 114 | 7 | 5.7 | |||||||

| c | 9.48 | 242 | 15 | 4.8 | |||||||

| d | 13.04 | 391 | 24 | 35.7 | |||||||

| e | 18.28 | 648 | 39 | 30.7 | |||||||

| f | 23.02 | 916 | 55 | 10.6 | |||||||

| g | 27.26 | 1179 | 71 | 5.2 | |||||||

| sHsp | Mutation | Sequence | ΔG (Kcal/mol) | ΔΔG |

| Hyperythermophilic | WT | KKGINIE | -12.87 | - |

| Mutant 1 | N145D | KKGIDIE | -12.81 | 0.059 |

| Mutant 2 | K142T | KTGINIE | -12.65 | 0.223 |

| Mutant 3 | K141R | RKGINIE | -12.53 | 0.346 |

| Thermophilc | K141R/K142R | RRGINIE | -12.68 | 0.189 |

| Mesophilic | K141R/K142T/N145D | RTGIDIE | -12.41 | 0.458 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).