Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

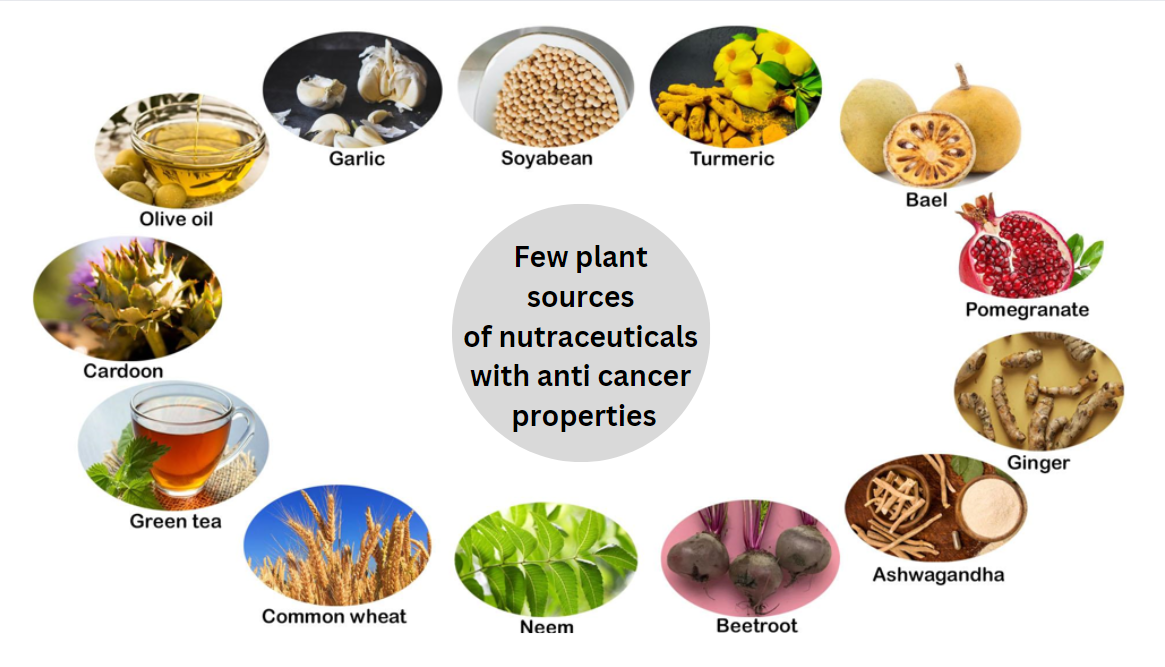

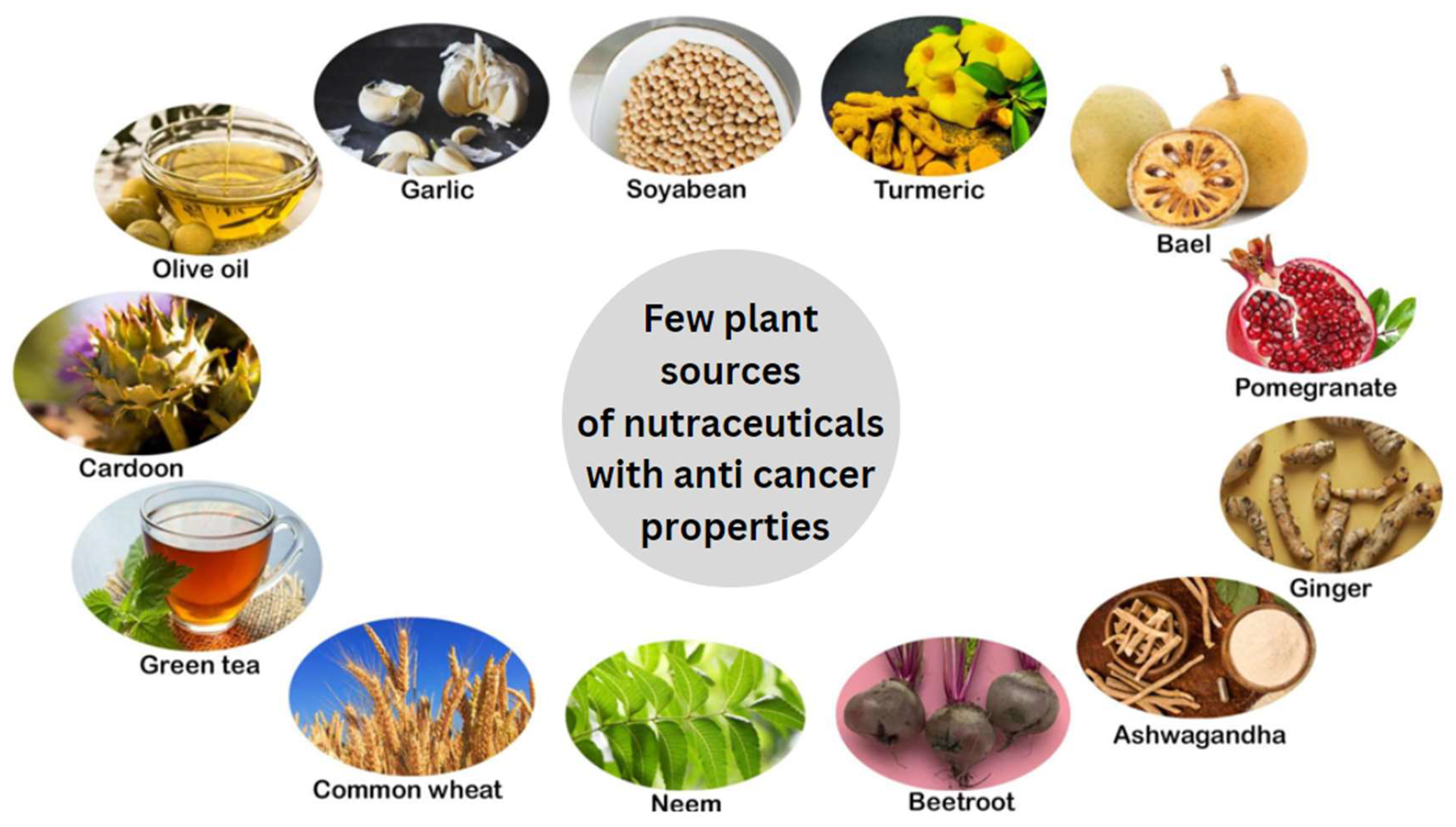

Introduction

Bael Fruit (Aegle marmelos Correa)

Soybean (Glycine max)

Garlic (Allium sativum)

Ginger (Zingiber officinale)

Olive Oil (Olea europaeae)

Pomegranate (Punica granatum)

Beetroot (Beta vulgaris)

Green Tea (Camellia sinensis)

Artichoke (Cynara cardunculus L.)

Neem (Azadirachta indica)

Turmeric (Curcuma longa)

Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera)

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

References

- Ronis, Martin J J et al. “Adverse Effects of Nutraceuticals and Dietary Supplements.” Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology vol. 58 (2018): 583-601. [CrossRef]

- Salami, A., Seydi, E., & Pourahmad, J. (2013). Use of nutraceuticals for prevention and treatment of cancer. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research : IJPR, 12(3), 219–220.

- Yoshida, T., Maoka, T., Das, S. K., Kanazawa, K., Horinaka, M., Wakada, M., Satomi, Y., Nishino, H., & Sakai, T. (2007). Halocynthiaxanthin and peridinin sensitize colon cancer cell lines to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Molecular cancer research : MCR, 5(6), 615–625. [CrossRef]

- Suh, Y., Afaq, F., Johnson, J. J., & Mukhtar, H. (2009). A plant flavonoid fisetin induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells by inhibition of COX2 and Wnt/EGFR/NF-kappaB-signaling pathways. Carcinogenesis, 30(2), 300–307. [CrossRef]

- Choi, E. J., Park, J. S., Kim, Y. J., Jung, J. H., Lee, J. K., Kwon, H. C., & Yang, H. O. (2011). Apoptosis-inducing effect of diketopiperazine disulfides produced by Aspergillus sp. KMD 901 isolated from marine sediment on HCT116 colon cancer cell lines. Journal of applied microbiology, 110(1), 304–313. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. C., Giovannucci, E., Erdman, J. W., Jr, Bahnson, R., Schwartz, S. J., & Clinton, S. K. (2002). Tomato products, lycopene, and prostate cancer risk. The Urologic clinics of North America, 29(1), 83–93. [CrossRef]

- Al-Wadei, H. A., Ullah, M. F., & Al-Wadei, M. (2011). GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid), a nonprotein amino acid counters the β-adrenergic cascade-activated oncogenic signaling in pancreatic cancer: a review of experimental evidence. Molecular nutrition & food research, 55(12), 1745–1758. [CrossRef]

- Jang, M., Cai, L., Udeani, G. O., Slowing, K. V., Thomas, C. F., Beecher, C. W., Fong, H. H., Farnsworth, N. R., Kinghorn, A. D., Mehta, R. G., Moon, R. C., & Pezzuto, J. M. (1997). Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science (New York, N.Y.), 275(5297), 218–220. [CrossRef]

- Illahi, A. F., Muhammad, F., & Akhtar, B. (2019). Nanoformulations of Nutraceuticals for Cancer Treatment. Critical reviews in eukaryotic gene expression, 29(5), 449–460. [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, S. N., & Tollefsbol, T. O. (2012). The role of nutraceuticals in chemoprevention and chemotherapy and their clinical outcomes. Journal of oncology, 2012, 192464. [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, G., Menniti-Ippolito, F., Moro, P. A., Cassetti, F., Raschetti, R., Santuccio, C., & Mastrangelo, S. (2009). Hepatotoxicity from green tea: a review of the literature and two unpublished cases. European journal of clinical pharmacology, 65(4), 331–341. [CrossRef]

- Akingbemi, B. T., Braden, T. D., Kemppainen, B. W., Hancock, K. D., Sherrill, J. D., Cook, S. J., He, X., & Supko, J. G. (2007). Exposure to phytoestrogens in the perinatal period affects androgen secretion by testicular Leydig cells in the adult rat. Endocrinology, 148(9), 4475–4488. [CrossRef]

- Allred, C. D., Allred, K. F., Ju, Y. H., Virant, S. M., & Helferich, W. G. (2001). Soy diets containing varying amounts of genistein stimulate growth of estrogen-dependent (MCF-7) tumors in a dose-dependent manner. Cancer research, 61(13), 5045–5050.

- Kothari, S., Mishra, V., Bharat, S., & Tonpay, S. D. (2011). Antimicrobial activity and phytochemical screening of serial extracts from leaves of Aegle marmelos (Linn.). Acta poloniae pharmaceutica, 68(5), 687–692.

- Chockalingam, V., Kadali, S. S., & Gnanasambantham, P. (2012). Antiproliferative and antioxidant activity of Aegle marmelos (Linn.) leaves in Dalton's Lymphoma Ascites transplanted mice. Indian journal of pharmacology, 44(2), 225–229. [CrossRef]

- Narender, T., Shweta, S., Tiwari, P., Papi Reddy, K., Khaliq, T., Prathipati, P., Puri, A., Srivastava, A. K., Chander, R., Agarwal, S. C., & Raj, K. (2007). Antihyperglycemic and antidyslipidemic agent from Aegle marmelos. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters, 17(6), 1808–1811. [CrossRef]

- Sharma RK, Bhagwan D. Agnivesa’s Charaka Samhita. Vol. 3. Varanasi, India: Chaukhambha Orientalia; 1988.

- Agrawal, A., Jahan, S., & Goyal, P. K. (2011). Chemically induced skin carcinogenesis in mice and its prevention by Aegle marmelos (an Indian medicinal plant) fruit extract. Journal of environmental pathology, toxicology and oncology : official organ of the International Society for Environmental Toxicology and Cancer, 30(3), 251–259. [CrossRef]

- George, Suraj & Radhakrishnan, Rajesh & Kumar S, Sunil & TT, Sreelekha & Balaram, Prabha. (2014). Chemopreventive Efficacy of Aegle marmelos on Murine Transplantable Tumors. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 1. 10.1177/1534735413490234.

- Pynam, H., & Dharmesh, S. M. (2018). Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of marmelosin from Bael (Aegle marmelos L.); Inhibition of TNF-α mediated inflammatory/tumor markers. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 106, 98–108. [CrossRef]

- Mujeeb, F., Khan, A. F., Bajpai, P., & Pathak, N. (2018). Phytochemical Study of Aegle marmelos: Chromatographic Elucidation of Polyphenolics and Assessment of Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Potential. Pharmacognosy magazine, 13(Suppl 4), S791–S800. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S., Bahorun, T., Singh, R. K., Aruoma, O. I., & Kumar, A. (2013). Effect of Aegle marmelos leaf extract on N-methyl N-nitrosourea-induced hepatocarcinogensis in BALB/c mice. Pharmaceutical biology, 51(10), 1272–1281. [CrossRef]

- Karawya, M. S., Mirhom, Y. W., Shehata, IA. (1980). Sterols, triterpenes, coumarins and alkaloids of Aegle marmelos Correa, cultivated in Egypt. Egypt Journal of Pharmaceutical Science, 1:388-389.

- Maity, P., Hansda, D., Bandyopadhyay, U., & Mishra, D. K. (2009). Biological activities of crude extracts and chemical constituents of Bael, Aegle marmelos (L.) Corr. Indian journal of experimental biology, 47(11), 849–861.

- Subramaniam, D., Giridharan, P., Murmu, N., Shankaranarayanan, N. P., May, R., Houchen, C. W., Ramanujam, R. P., Balakrishnan, A., Vishwakarma, R. A., & Anant, S. (2008). Activation of apoptosis by 1-hydroxy-5,7-dimethoxy-2-naphthalene-carboxaldehyde, a novel compound from Aegle marmelos. Cancer research, 68(20), 8573–8581. [CrossRef]

- Atsumi, T., Fujisawa, S., Satoh, K., Sakagami, H., Iwakura, I., Ueha, T., Sugita, Y., & Yokoe, I. (2000). Cytotoxicity and radical intensity of eugenol, isoeugenol or related dimers. Anticancer research, 20(4), 2519–2524.

- Dudai, N., Weinstein, Y., Krup, M., Rabinski, T., & Ofir, R. (2005). Citral is a new inducer of caspase-3 in tumor cell lines. Planta medica, 71(5), 484–488. [CrossRef]

- Moteki, H., Hibasami, H., Yamada, Y., Katsuzaki, H., Imai, K., & Komiya, T. (2002). Specific induction of apoptosis by 1,8-cineole in two human leukemia cell lines, but not an in human stomach cancer cell line. Oncology reports, 9(4), 757–760.

- Jagetia, G. C., Venkatesh, P., & Baliga, M. S. (2004). Evaluation of the radioprotective effect of bael leaf (Aegle marmelos) extract in mice. International journal of radiation biology, 80(4), 281–290. [CrossRef]

- Quassinti, L., Maggi, F., Barboni, L., Ricciutelli, M., Cortese, M., Papa, F., Garulli, C., Kalogris, C., Vittori, S., & Bramucci, M. (2014). Wild celery (Smyrnium olusatrum L.) oil and isofuranodiene induce apoptosis in human colon carcinoma cells. Fitoterapia, 97, 133–141. [CrossRef]

- Saravankumar V., Anusha R., Balasubramanyam M., Vishwanathan M. Phytochemical analysis and evaluation of antioxidants, antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory properties of Aegle marmelos and its validation and its validation in an in vitro cell model. Cureus. 2024;16(9);e70491. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Liu, L., Ji, F., Jiang, J., Yu, Y., Sheng, S., & Li, H. (2018). Soybean (Glycine max) prevents the progression of breast cancer cells by downregulating the level of histone demethylase JMJD5. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics, 14(Supplement), S609–S615. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Pi, C., & Wang, G. (2018). Inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway by apigenin induces apoptosis and autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 103, 699–707. [CrossRef]

- Ravindranath, M. H., Muthugounder, S., Presser, N., & Viswanathan, S. (2004). Anticancer therapeutic potential of soy isoflavone, genistein. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 546, 121–165. [CrossRef]

- de Mejia, E. G., & Dia, V. P. (2009). Lunasin and lunasin-like peptides inhibit inflammation through suppression of NF-kappaB pathway in the macrophage. Peptides, 30(12), 2388–2398. [CrossRef]

- Pratama DAO, Annesia, F. Riccadonna, R, Fazar SP, and Muhammad LN. Black soybean extract inhibits rat mammary carcinogenesis through BRCA1 and TNF-α expression: In silico and in vivo study. Open Vet J. 2024 Oct;14(10):2678-2686. [CrossRef]

- Roy, N., Davis, S., Narayanankutty, A., Nazeem, P., Babu, T., Abida, P., Valsala, P., & Raghavamenon, A. C. (2016). Garlic Phytocompounds Possess Anticancer Activity by Specifically Targeting Breast Cancer Biomarkers - an in Silico Study. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP, 17(6), 2883–2888.

- Akira Sato, Ayano Yabuki, Genta Sato, Hina Nemoto, Yuta Ogawa and Makoto Ohira. Garlic (Allium sativum L.) Organosulfur compounds inhibit breast cancer cell proliferation by decreasing steroid sulfatase levels. Anticancer Res.2025 Jan; 45(1):145-152;. [CrossRef]

- Perchellet, J. P., Perchellet, E. M., & Belman, S. (1990). Inhibition of DMBA-induced mouse skin tumorigenesis by garlic oil and inhibition of two tumor-promotion stages by garlic and onion oils. Nutrition and cancer, 14(3-4), 183–193. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. C., Chung, J. G., Tsai, S. J., Yang, J. H., & Sheen, L. Y. (2004). Differential effects of allyl sulfides from garlic essential oil on cell cycle regulation in human liver tumor cells. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association, 42(12), 1937–1947. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D., Herman-Antosiewicz, A., Antosiewicz, J., Xiao, H., Brisson, M., Lazo, J. S., & Singh, S. V. (2005). Diallyl trisulfide-induced G(2)-M phase cell cycle arrest in human prostate cancer cells is caused by reactive oxygen species-dependent destruction and hyperphosphorylation of Cdc 25 C. Oncogene, 24(41), 6256–6268. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Benson, P. J., Srivastava, S. K., Xia, H., Bleicher, R. J., Zaren, H. A., Awasthi, S., Awasthi, Y. C., & Singh, S. V. (1997). Induction of glutathione S-transferase pi as a bioassay for the evaluation of potency of inhibitors of benzo(a)pyrene-induced cancer in a murine model. International journal of cancer, 73(6), 897–902. [CrossRef]

- Wu, P. P., Liu, K. C., Huang, W. W., Chueh, F. S., Ko, Y. C., Chiu, T. H., Lin, J. P., Kuo, J. H., Yang, J. S., & Chung, J. G. (2011). Diallyl trisulfide (DATS) inhibits mouse colon tumor in mouse CT-26 cells allograft model in vivo. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 18(8-9), 672–676. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z. H., Zhang, G. M., Hao, T. L., Zhou, B., Zhang, H., & Jiang, Z. Y. (1994). Effect of diallyl trisulfide on the activation of T-cell and macrophage-mediated cytotoxicity. Journal of Tongji Medical University = Tong ji yi ke da xue xue bao, 14(3), 142–147. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K. L., Chen, H. W., Wang, R. Y., Lei, Y. P., Sheen, L. Y., & Lii, C. K. (2006). DATS reduces LPS-induced iNOS expression, NO production, oxidative stress, and NF-kappaB activation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 54(9), 3472–3478. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Li, H. Q., Wang, Y., Xu, H. X., Fan, W. T., Wang, M. L., Sun, P. H., & Xie, X. Y. (2004). An intervention study to prevent gastric cancer by microselenium and large dose of allitridum. Chinese medical journal, 117(8), 1155–1160.

- Xiao, J., Ching, Y. P., Liong, E. C., Nanji, A. A., Fung, M. L., & Tipoe, G. L. (2013). Garlic-derived S-allylmercaptocysteine is a hepato-protective agent in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in vivo animal model. European journal of nutrition, 52(1), 179–191. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Xia, Y., Zhang, X., Liu, L., Tu, S., Zhu, W., Yu, L., Wan, H., Yu, B., & Wan, F. (2018). Roles of the MST1-JNK signaling pathway in apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells induced by Taurine. The Libyan journal of medicine, 13(1), 1500346. [CrossRef]

- Oommen, S., Anto, R. J., Srinivas, G., & Karunagaran, D. (2004). Allicin (from garlic) induces caspase-mediated apoptosis in cancer cells. European journal of pharmacology, 485(1-3), 97–103. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q., Lee, D. T., Tsao, S. W., Wang, X., & Wong, Y. C. (2007). S-allylcysteine, a water-soluble garlic derivative, suppresses the growth of a human androgen-independent prostate cancer xenograft, CWR22R, under in vivo conditions. BJU international, 99(4), 925–932. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M. M., Haniadka, R., Chacko, P. P., Palatty, P. L., & Baliga, M. S. (2011). Zingiber officinale Roscoe (ginger) as an adjuvant in cancer treatment: a review. Journal of B.U.ON. : official journal of the Balkan Union of Oncology, 16(3), 414–424.

- Habib, S. H., Makpol, S., Abdul Hamid, N. A., Das, S., Ngah, W. Z., & Yusof, Y. A. (2008). Ginger extract (Zingiber officinale) has anticancer and anti-inflammatory effects on ethionine-induced hepatoma rats. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil), 63(6), 807–813. [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, M., Iizuka, M., Kanematsu, R., Yoshida, M., & Takenaga, K. (2015). Anticancer Effect of Ginger Extract against Pancreatic Cancer Cells Mainly through Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Autotic Cell Death. PloS one, 10(5), e0126605. [CrossRef]

- Bode, A. M., & Dong, Z. (2011). The Amazing and Mighty Ginger. In I. Benzie (Eds.) et al., Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. (2nd ed.). CRC Press/Taylor & Francis.

- Zick SM, Djuric Z, Ruffin MT, Litzinger AJ, Normolle DP, Alrawi S, Feng MR, Brenner DE. Pharmacokinetics of 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, 10-gingerol, and 6-shogaol and conjugate metabolites in healthy human subjects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Aug;17(8):1930-6. PMID: 18708382; PMCID: PMC2676573. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Y., Li, Y. W., & Kuo, S. Y. (2009). Effect of [10]-gingerol on [ca2+]i and cell death in human colorectal cancer cells. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 14(3), 959–969. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Hsieh, M. C., Lo, C. Y., Liu, C. B., Sang, S., Ho, C. T., & Pan, M. H. (2010). 6-Shogaol is more effective than 6-gingerol and curcumin in inhibiting 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate-induced tumor promotion in mice. Molecular nutrition & food research, 54(9), 1296–1306. [CrossRef]

- Mukkavilli, R., Yang, C., Tanwar, R. S., Saxena, R., Gundala, S. R., Zhang, Y., Ghareeb, A., Floyd, S. D., Vangala, S., Kuo, W. W., Rida, P., & Aneja, R. (2018). Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic correlations in the development of ginger extract as an anticancer agent. Scientific reports, 8(1), 3056. [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, K., Ando, T., Maeda, O., Ohmiya, N., Niwa, Y., Kadomatsu, K., & Goto, H. (2007). Ginger ingredients reduce viability of gastric cancer cells via distinct mechanisms. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 362(1), 218–223. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S., & Tyagi, A. K. (2015). Ginger and its constituents: role in prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2015, 142979. [CrossRef]

- Terzuoli, E., Nannelli, G., Frosini, M., Giachetti, A., Ziche, M., & Donnini, S. (2017). Inhibition of cell cycle progression by the hydroxytyrosol-cetuximab combination yields enhanced chemotherapeutic efficacy in colon cancer cells. Oncotarget, 8(47), 83207–83224. [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, R. S., & Wagner, K. (2012). Influence of dietary phytochemicals and microbiota on colon cancer risk. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 60(27), 6728–6735. [CrossRef]

- Khanfar, M. A., Bardaweel, S. K., Akl, M. R., & El Sayed, K. A. (2015). Olive Oil-derived Oleocanthal as Potent Inhibitor of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin: Biological Evaluation and Molecular Modeling Studies. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 29(11), 1776–1782. [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, R., Rosignoli, P., De Bartolomeo, A., Fuccelli, R., Servili, M., Montedoro, G. F., & Morozzi, G. (2008). Oxidative DNA damage is prevented by extracts of olive oil, hydroxytyrosol, and other olive phenolic compounds in human blood mononuclear cells and HL60 cells. The Journal of nutrition, 138(8), 1411–1416. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, A., Mosca, L., Puca, R., Mangino, G., Rossi, A., & Lendaro, E. (2016). Extravirgin olive oil phenols block cell cycle progression and modulate chemotherapeutic toxicity in bladder cancer cells. Oncology reports, 36(6), 3095–3104. [CrossRef]

- Fezai, M., Senovilla, L., Jemaà, M., & Ben-Attia, M. (2013). Analgesic, anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of extra virgin olive oil. Journal of lipids, 2013, 129736. [CrossRef]

- LeGendre, O., Breslin, P. A., & Foster, D. A. (2015). (-)-Oleocanthal rapidly and selectively induces cancer cell death via lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Molecular & cellular oncology, 2(4), e1006077. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Yang, P., Luo, X., Su, C., Chen, Y., Zhao, L., Wei, L., Zeng, H., Varghese, Z., Moorhead, J. F., Ruan, X. Z., & Chen, Y. (2019). High olive oil diets enhance cervical tumor growth in mice: transcriptome analysis for potential candidate genes and pathways. Lipids in health and disease, 18(1), 76. [CrossRef]

- Martos, M. V., López, J. F., Pérez-Álvarez, J. A. (2010). .Pomegranate and its Many Functional Components as Related to Human Health: A Review. Comprehensive Review in Food Science and Food Safety, 9(6), 635-654. [CrossRef]

- Adhami, V. M., Khan, N., & Mukhtar, H. (2009). Cancer chemoprevention by pomegranate: laboratory and clinical evidence. Nutrition and cancer, 61(6), 811–815. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., Choi, H. S., Zhen, X., Kim, S. L., Kim, J. H., Ko, Y. C., Yun, B. S., & Lee, D. S. (2020). Betavulgarin Isolated from Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris) Suppresses Breast Cancer Stem Cells through Stat3 Signaling. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 25(13), 2999. [CrossRef]

- Ninfali, P., Antonini, E., Frati, A., & Scarpa, E. S. (2017). C-Glycosyl Flavonoids from Beta vulgaris Cicla and Betalains from Beta vulgaris rubra: Antioxidant, Anticancer and Antiinflammatory Activities-A Review. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 31(6), 871–884. [CrossRef]

- Esatbeyoglu, T., Huebbe, P., Ernst, I. M., Chin, D., Wagner, A. E., & Rimbach, G. (2012). Curcumin--from molecule to biological function. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English), 51(22), 5308–5332. [CrossRef]

- Ren, K., Zhang, W., Wu, G., Ren, J., Lu, H., Li, Z., & Han, X. (2016). Synergistic anticancer effects of galangin and berberine through apoptosis induction and proliferation inhibition in esophageal carcinoma cells. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 84, 1748–1759. [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, L., Vigneron, P., Rotellini, L., Cazzola, H., Merlier, F., Prost, E., Ralanairina, R., Gadonna, J. P., Rossi, C., & Vayssade, M. (2015). Betanin-Enriched Red Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) Extract Induces Apoptosis and Autophagic Cell Death in MCF-7 Cells. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 29(12), 1964–1973. [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, R., Hallmann, E., Lipowski, J., Drela, N., Kowalik, A., Püssa, T., Matt, D., Luik, A., Gozdowski, D., & Rembiałkowska, E. (2014). Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) and naturally fermented beetroot juices from organic and conventional production: metabolomics, antioxidant levels and anticancer activity. Journal of the science of food and agriculture, 94(13), 2618–2629. [CrossRef]

- Coimbra PPS, Silva-e-Silva ACAG, Silva Antonio A, Pereira HMG, Veiga Junior VF, Felzenszwalb I, Araujo-Lima CF, and Teodoro AJ. Antioxidant capacity, antitumour activity, and metabolomic profile of a beetroot peel flour. Metabolites.2023,13(2):277:. [CrossRef]

- Farhan, Mohd. “Green Tea Catechins: Nature's Way of Preventing and Treating Cancer.” International journal of molecular sciences vol. 23,18 10713. 14 Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Farhan M., Rizvi A., Naseem I., Hadi S.M., Ahmad A. Targeting increased copper levels in diethylnitrosamine induced hepatocellular carcinoma cells in rats by epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Tumor Biol. 2015;36:8861–8867. [CrossRef]

- Toden S., Tran H.M., Tovar-Camargo O.A., Okugawa Y., Goel A. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate targets cancer stem-like cells and enhances 5-fluorouracil chemosensitivity in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:16158–16170. [CrossRef]

- Bonuccelli G., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. Matcha green tea (MGT) inhibits the propagation of cancer stem cells (CSCs), by targeting mitochondrial metabolism, glycolysis, and multiple cell signaling pathways. Aging. 2018;10:1867–1883. [CrossRef]

- Khan N., Mukhtar H. Tea and health: Studies in humans. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013;19:6141–6147. [CrossRef]

- Fujiki H., Watanabe T., Sueoka E., Rawangkan A., Suganuma M. Cancer Prevention with Green Tea and Its Principal Constituent, EGCG: From Early Investigations to Current Focus on Human Cancer Stem Cells. Mol. Cells. 2018;41:73–82.

- Fu H., He J., Mei F., Zhang Q., Hara Y., Ryota S. Lung cancer inhibitory effect of epigallocatechin-3-gallate is dependent on its presence in a complex mixture (polyphenon E) Cancer Prev. Res. 2009;2:531–537. [CrossRef]

- Mahboub, F. A., Khorshid, F.A. (2010). The Role of Green Tea Extract on the Proliferation of Human Ovarian Cancer Cells (in vitro) Study. International Journal of Cancer Research, 6(2), 78-88. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. C., Kim, J. H., Prasad, S., & Aggarwal, B. B. (2010). Regulation of survival, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis of tumor cells through modulation of inflammatory pathways by nutraceuticals. Cancer metastasis reviews, 29(3), 405–434. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Wan, S. B., Yang, H., Yuan, J., Chan, T. H., & Dou, Q. P. (2011). EGCG, green tea polyphenols and their synthetic analogs and prodrugs for human cancer prevention and treatment. Advances in clinical chemistry, 53, 155–177. [CrossRef]

- Raad C, Raad A and Pandey S. Green Tea Leaves and Rosemary Extracts Selectively Induce Cell Death in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells and Cancer Stem Cells and Enhance the Efficacy of Common Chemotherapeutics. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2024 Jan 25:2024:9458716. [CrossRef]

- Hassabou, N. F., & Farag, A. F. (2020). Anticancer effects induced by artichoke extract in oral squamous carcinoma cell lines. Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute, 32(1), 17. [CrossRef]

- Park, B. H., Lim, J. E., Jeon, H. G., Seo, S. I., Lee, H. M., Choi, H. Y., Jeon, S. S., & Jeong, B. C. (2016). Curcumin potentiates antitumor activity of cisplatin in bladder cancer cell lines via ROS-mediated activation of ERK1/2. Oncotarget, 7(39), 63870–63886. [CrossRef]

- Chan, M. M., Soprano, K. J., Weinstein, K., & Fong, D. (2006). Epigallocatechin-3-gallate delivers hydrogen peroxide to induce death of ovarian cancer cells and enhances their cisplatin susceptibility. Journal of cellular physiology, 207(2), 389–396. [CrossRef]

- Senthil, B., Devasena, T., Prakash, B., & Rajasekar, A. (2017). Noncytotoxic effect of green synthesized silver nanoparticles and its antibacterial activity. Journal of photochemistry and photobiology. B, Biology, 177, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Samuggam, S., Vasanthi, S., Sivadasan, S., 3, Chinni, S. V., 1, Gopinath, S. C. B., Kathiresan, S., Anbu, P., Ravichandran, V. (2019). Durio zibethinus rind extract mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and biomedical applications.Pharmacognosy Magazine, 15(30), 52-58. [CrossRef]

- Antonenko, Y. N., Kotova, E. A., Omarova, E. O., Rokitskaya, T. I., Ol'shevskaya, V. A., Kalinin, V. N., Nikitina, R. G., Osipchuk, J. S., Kaplan, M. A., Ramonova, A. A., Moisenovich, M. M., Agapov, I. I., & Kirpichnikov, M. P. (2014). Photodynamic activity of the boronated chlorin e6 amide in artificial and cellular membranes. Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1838(3), 793–801. [CrossRef]

- Braathen, L. R., Szeimies, R. M., Basset-Seguin, N., Bissonnette, R., Foley, P., Pariser, D., Roelandts, R., Wennberg, A. M., Morton, C. A., & International Society for Photodynamic Therapy in Dermatology (2007). Guidelines on the use of photodynamic therapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: an international consensus. International Society for Photodynamic Therapy in Dermatology, 2005. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 56(1), 125–143. [CrossRef]

- Abel, F., Sjöberg, R. M., Nilsson, S., Kogner, P., & Martinsson, T. (2005). Imbalance of the mitochondrial pro- and anti-apoptotic mediators in neuroblastoma tumors with unfavorable biology. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990), 41(4), 635–646. [CrossRef]

- Balasenthil, S., Arivazhagan, S., Ramachandran, C. R., Ramachandran, V., & Nagini, S. (1999). Chemopreventive potential of neem (Azadirachta indica) on 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced hamster buccal pouch carcinogenesis. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 67(2), 189–195. [CrossRef]

- Morris, J., Gonzales, C. B., De La Chapa, J. J., Cabang, A. B., Fountzilas, C., Patel, M., Orozco, S., & Wargovich, M. J. (2019). The Highly Pure Neem Leaf Extract, SCNE, Inhibits Tumorigenesis in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma via Disruption of Pro-tumor Inflammatory Cytokines and Cell Signaling. Frontiers in oncology, 9, 890. [CrossRef]

- Patra, A., Satpathy, S., & Hussain, M. D. (2019). Nanodelivery and anticancer effect of a limonoid, nimbolide, in breast and pancreatic cancer cells. International journal of nanomedicine, 14, 8095–8104. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. M., Patel, V., Shyur, L. F., & Lee, W. L. (2016). Copper supplementation amplifies the anti-tumor effect of curcumin in oral cancer cells. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 23(12), 1535–1544. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Xu, T., & Chen, C. (2015). The critical roles of miR-21 in anticancer effects of curcumin. Annals of translational medicine, 3(21), 330. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Peng, Y., Wu, L. C., Xie, Z., Deng, Y., Hughes, T., He, S., Mo, X., Chiu, M., Wang, Q. E., He, X., Liu, S., Grever, M. R., Chan, K. K., & Liu, Z. (2013). Curcumin downregulates DNA methyltransferase 1 and plays an anti-leukemic role in acute myeloid leukemia. PloS one, 8(2), e55934. [CrossRef]

- Shi, L., Fei, X., & Wang, Z. (2015). Demethoxycurcumin was prior to temozolomide on inhibiting proliferation and induced apoptosis of glioblastoma stem cells. Tumor biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine, 36(9), 7107–7119. [CrossRef]

- Mengjie Li, Lihua Chen, Miao Wang, Xia Huang, Qiaodan Ke and Chenxia Hu. Curcumin alleviates the aggressiveness of breast cancer through inhibiting cell adhesion mediated by TEAD4-fibronectin axis. Biochemical Pharmacol.2024 Nov.29:232:116690. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. C., Jan, T. R., & Yeh, S. F. (1992). Inhibitory effect of curcumin, an anti-inflammatory agent, on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. European journal of pharmacology, 221(2-3), 381–384. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., & Aggarwal, B. B. (1995). Activation of transcription factor NF-kappa B is suppressed by curcumin (diferuloylmethane) [corrected]. The Journal of biological chemistry, 270(42), 24995–25000. [CrossRef]

- Heger, M., van Golen, R. F., Broekgaarden, M., & Michel, M. C. (2013). The molecular basis for the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of curcumin and its metabolites in relation to cancer. Pharmacological reviews, 66(1), 222–307. [CrossRef]

- Yallapu, M. M., Jaggi, M., & Chauhan, S. C. (2012). Curcumin nanoformulations: a future nanomedicine for cancer. Drug discovery today, 17(1-2), 71–80. [CrossRef]

- Yue, G. G., Chan, B. C., Hon, P. M., Lee, M. Y., Fung, K. P., Leung, P. C., & Lau, C. B. (2010). Evaluation of in vitro anti-proliferative and immunomodulatory activities of compounds isolated from Curcuma longa. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association, 48(8-9), 2011–2020. [CrossRef]

- Mukunthan, K. S., Satyan, R. S., & Patel, T. N. (2017). Pharmacological evaluation of phytochemicals from South Indian Black Turmeric (Curcuma caesia Roxb.) to target cancer apoptosis. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 209, 82–90. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Wang, X., & Yu, L. (1996). Zhonghua zhong liu za zhi [Chinese journal of oncology], 18(3), 169–172.

- Zhao, S., Wu, J., Zheng, F., Tang, Q., Yang, L., Li, L., Wu, W., & Hann, S. S. (2015). β-elemene inhibited expression of DNA methyltransferase 1 through activation of ERK1/2 and AMPKα signaling pathways in human lung cancer cells: the role of Sp1. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 19(3), 630–641. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. S., Dang, Y. Y., Guo, J. J., Wu, G. S., Lu, J. J., Chen, X. P., & Wang, Y. T. (2012). Furanodiene induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and presents antiproliferative activities in lung cancer cells. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2012, 426521. [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.I., Nizamutdinova I. T., Kim Y. M., et al. (2008). Bisacurone inhibits adhesion of inflammatory monocytes or cancer cells to endothelial cells through downregulation of VCAM-1 expression. International Immunopharmacology, 8(9):1272-1281. [CrossRef]

- Kataria, H., Kumar, S., Chaudhary, H., & Kaur, G. (2016). Withania somnifera Suppresses Tumor Growth of Intracranial Allograft of Glioma Cells. Molecular neurobiology, 53(6), 4143–4158. [CrossRef]

- Asifa Khan, Asad ur Rehman, Shumaila Siddiqui, Jiyauddin Khan, Sheersh Massey, Prithvi Singh, Daman Saluja, Syed Akhtar Husain and Mohammad Askandar Iqbal. Withaferin A decreases glycolytic reprogramming in breast cancer. Scientific Reports 2024(14) -23147. [CrossRef]

- Barua, A., Bradaric, M. J., Bitterman, P., Abramowicz, J. S., Sharma, S., Basu, S., Lopez, H., & Bahr, J. M. (2013). Dietary supplementation of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera, Dunal) enhances NK cell function in ovarian tumors in the laying hen model of spontaneous ovarian cancer. American journal of reproductive immunology (New York, N.Y. : 1989), 70(6), 538–550. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R., Hammers, H. J., Bargagna-Mohan, P., Zhan, X. H., Herbstritt, C. J., Ruiz, A., Zhang, L., Hanson, A. D., Conner, B. P., Rougas, J., & Pribluda, V. S. (2004). Withaferin A is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Angiogenesis, 7(2), 115–122. [CrossRef]

- Min, K. J., Choi, K., & Kwon, T. K. (2011). Withaferin A downregulates lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression and PGE2 production through the inhibition of STAT1/3 activation in microglia. International immunopharmacology, 11(8), 1137–1142. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., & Anderson, J. J. (2001). Isoflavones inhibit proliferation of ovarian cancer cells in vitro via an estrogen receptor-dependent pathway. Nutrition and cancer, 41(1-2), 165–171. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., Wu, X., Cao, Y., Hou, Y., Chen, H., Wu, L., Lu, L., Zhu, W., & Gu, Y. (2016). Daidzein exerts anti-tumor activity against bladder cancer cells via inhibition of FGFR3 pathway. Neoplasma, 63(4), 523–531. [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y. Q., Feng, Y. Y., Luo, Y. H., Zhai, Y. Q., Ju, X. Y., Feng, Y. C., Wang, J. R., Yu, C. Q., & Jin, C. H. (2019). Glycitein induces reactive oxygen species-dependent apoptosis and G0/G1 cell cycle arrest through the MAPK/STAT3/NF-κB pathway in human gastric cancer cells. Drug development research, 80(5), 573–584. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P., Wang, C., Hu, Z., Chen, W., Qi, W., & Li, A. (2017). Genistein induces apoptosis of colon cancer cells by reversal of epithelial-to-mesenchymal via a Notch1/NF-κB/slug/E-cadherin pathway. BMC cancer, 17(1), 813. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. H., Rajamanickam, V., & Nagarajan, S. (2018). Antiproliferative effect of p-Coumaric acid targets UPR activation by downregulating Grp78 in colon cancer. Chemico-biological interactions, 291, 16–28. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. W., Lee, S. Y., Kim, M., Cheon, C., & Ko, S. G. (2018). Kaempferol induces autophagic cell death via IRE1-JNK-CHOP pathway and inhibition of G9a in gastric cancer cells. Cell death & disease, 9(9), 875. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Xia, Y., Zhang, X., Liu, L., Tu, S., Zhu, W., Yu, L., Wan, H., Yu, B., & Wan, F. (2018). Roles of the MST1-JNK signaling pathway in apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells induced by Taurine. The Libyan journal of medicine, 13(1), 1500346. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Pi, C., & Wang, G. (2018). Inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway by apigenin induces apoptosis and autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 103, 699–707. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Zhang, H., Liu, T., Yang, W., Lv, W., He, D., Guo, P., & Li, L. (2020). 6-Gingerol induces cell-cycle G1-phase arrest through AKT-GSK 3β-cyclin D1 pathway in renal-cell carcinoma. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology, 85(2), 379–390. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S. M., Yao, X. H., Hao, Y. H., Pan, A. H., & Zhou, X. W. (2020). 8-Gingerol regulates colorectal cancer cell proliferation and migration through the EGFR/STAT/ERK pathway. International journal of oncology, 56(1), 390–397. [CrossRef]

- Ediriweera, M. K., Moon, J. Y., Nguyen, Y. T., & Cho, S. K. (2020). 10-Gingerol Targets Lipid Rafts Associated PI3K/Akt Signaling in Radio-Resistant Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 25(14), 3164. [CrossRef]

- Bawadood, A. S., Al-Abbasi, F. A., Anwar, F., El-Halawany, A. M., & Al-Abd, A. M. (2020). 6-Shogaol suppresses the growth of breast cancer cells by inducing apoptosis and suppressing autophagy by targeting notch signaling pathway. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 128, 110302. [CrossRef]

- Hong, M. Y., Seeram, N. P., & Heber, D. (2008). Pomegranate polyphenols downregulate expression of androgen-synthesizing genes in human prostate cancer cells overexpressing the androgen receptor. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry, 19(12), 848–855. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Palencia, L. A., Noratto, G., Hingorani, L., Talcott, S. T., & Mertens-Talcott, S. U. (2008). Protective effects of standardized pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) polyphenolic extract in ultraviolet-irradiated human skin fibroblasts. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 56(18), 8434–8441. [CrossRef]

- Costantini, S., Rusolo, F., De Vito, V., Moccia, S., Picariello, G., Capone, F., Guerriero, E., Castello, G., & Volpe, M. G. (2014). Potential anti-inflammatory effects of the hydrophilic fraction of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) seed oil on breast cancer cell lines. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 19(6), 8644–8660. [CrossRef]

- Boussetta, T., Raad, H., Lettéron, P., Gougerot-Pocidalo, M. A., Marie, J. C., Driss, F., & El-Benna, J. (2009). Punicic acid a conjugated linolenic acid inhibits TNFalpha-induced neutrophil hyperactivation and protects from experimental colon inflammation in rats. PloS one, 4(7), e6458. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., Choi, H. S., Zhen, X., Kim, S. L., Kim, J. H., Ko, Y. C., Yun, B. S., & Lee, D. S. (2020). Betavulgarin Isolated from Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris) Suppresses Breast Cancer Stem Cells through Stat3 Signaling. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 25(13), 2999. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., You, P., Luo, Y., Yang, M., & Liu, Y. (2018). Galangin Induces Apoptosis in MCF-7 Human Breast Cancer Cells Through Mitochondrial Pathway and Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt Inhibition. Pharmacology, 102(1-2), 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Hua, W., Li, Y., Xian, X., Zhao, Z., Liu, C., Zou, J., Li, J., Fang, X., & Zhu, Y. (2020). Berberine suppresses colon cancer cell proliferation by inhibiting the SCAP/SREBP-1 signaling pathway-mediated lipogenesis. Biochemical pharmacology, 174, 113776. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Song, J., Li, E., Geng, H., Li, Y., Yu, D., & Zhong, C. (2019). (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits bladder cancer stem cells via suppression of sonic hedgehog pathway. Oncology reports, 42(1), 425–435. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L., Zhou, M., Huang, D., Wasan, H. S., Zhang, K., Sun, L., Huang, H., Ma, S., Shen, M., & Ruan, S. (2019). Resveratrol inhibits the invasion and metastasis of colon cancer through reversal of epithelial- mesenchymal transition via the AKT/GSK-3β/Snail signaling pathway. Molecular medicine reports, 20(3), 2783–2795. [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, Perumal, and Jagadeesan Arunakaran. “Review on molecular and chemopreventive potential of nimbolide in cancer.” Genomics & informatics vol. 12,4 (2014): 156-64. [CrossRef]

- Sophia, J., Kowshik, J., Dwivedi, A., Bhutia, S. K., Manavathi, B., Mishra, R., & Nagini, S. (2018). Nimbolide, a neem limonoid inhibits cytoprotective autophagy to activate apoptosis via modulation of the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway in oral cancer. Cell death & disease, 9(11), 1087. [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R., Gonzalez, E., Nandy, S. B., Arumugam, A., Camacho, F., Medel, J., Alabi, D., & Lakshmanaswamy, R. (2017). Gedunin inhibits pancreatic cancer by altering sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. Oncotarget, 8(7), 10891–10904. [CrossRef]

- Song, X., Zhang, M., Dai, E., & Luo, Y. (2019). Molecular targets of curcumin in breast cancer (Review). Molecular medicine reports, 19(1), 23–29. [CrossRef]

- Soni, D., & Salh, B. (2012). A neutraceutical by design: the clinical application of curcumin in colonic inflammation and cancer. Scientifica, 2012, 757890. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z., Chen, X., Tan, W., Xu, Z., Zhou, K., Wu, T., Cui, L., & Wang, Y. (2011). Germacrone inhibits the proliferation of breast cancer cell lines by inducing cell cycle arrest and promoting apoptosis. European journal of pharmacology, 667(1-3), 50–55. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z., Xu, J., Shao, M., & Zou, J. (2020). Germacrone Induces Apoptosis as Well as Protective Autophagy in Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer management and research, 12, 4009–4016. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A. K., Prasad, S., Majeed, M., & Aggarwal, B. B. (2016). Calebin A downregulates osteoclastogenesis through suppression of RANKL signaling. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics, 593, 80–89. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Li, S., Han, Y., Liu, J., Zhang, J., Li, F., Wang, Y., Liu, X., & Yao, L. (2008). Calebin-A induces apoptosis and modulates MAPK family activity in drug resistant human gastric cancer cells. European journal of pharmacology, 591(1-3), 252–258. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q., Ren, L., Liu, J., Li, W., Zheng, X., Wang, J., & Du, G. (2020). Withaferin A triggers G2/M arrest and intrinsic apoptosis in glioblastoma cells via ATF4-ATF3-CHOP axis. Cell proliferation, 53(1), e12706. [CrossRef]

- Widodo, N., Priyandoko, D., Shah, N., Wadhwa, R., & Kaul, S. C. (2010). Selective killing of cancer cells by Ashwagandha leaf extract and its component Withanone involves ROS signaling. PloS one, 5(10), e13536. [CrossRef]

- Cook M. T. (2018). Mechanism of metastasis suppression by luteolin in breast cancer. Breast cancer (Dove Medical Press), 10, 89–100. [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S., Raza, M. H., Younas, M., Naeem, F., Adeeb, R., Iqbal, J., Anwar, P., Sajid, U. & Manzoor, H. M. (2018) Molecular Targets of Curcumin and Future Therapeutic Role in Leukemia. Journal of Biosciences and Medicines, 6, 33-50. [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y. Q., Feng, Y. Y., Luo, Y. H., Zhai, Y. Q., Ju, X. Y., Feng, Y. C., Wang, J. R., Yu, C. Q., & Jin, C. H. (2019). Glycitein induces reactive oxygen species-dependent apoptosis and G0/G1 cell cycle arrest through the MAPK/STAT3/NF-κB pathway in human gastric cancer cells. Drug development research, 80(5), 573–584. [CrossRef]

- Bishayee A. (2009). Cancer prevention and treatment with resveratrol: from rodent studies to clinical trials. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa.), 2(5), 409–418. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).