Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

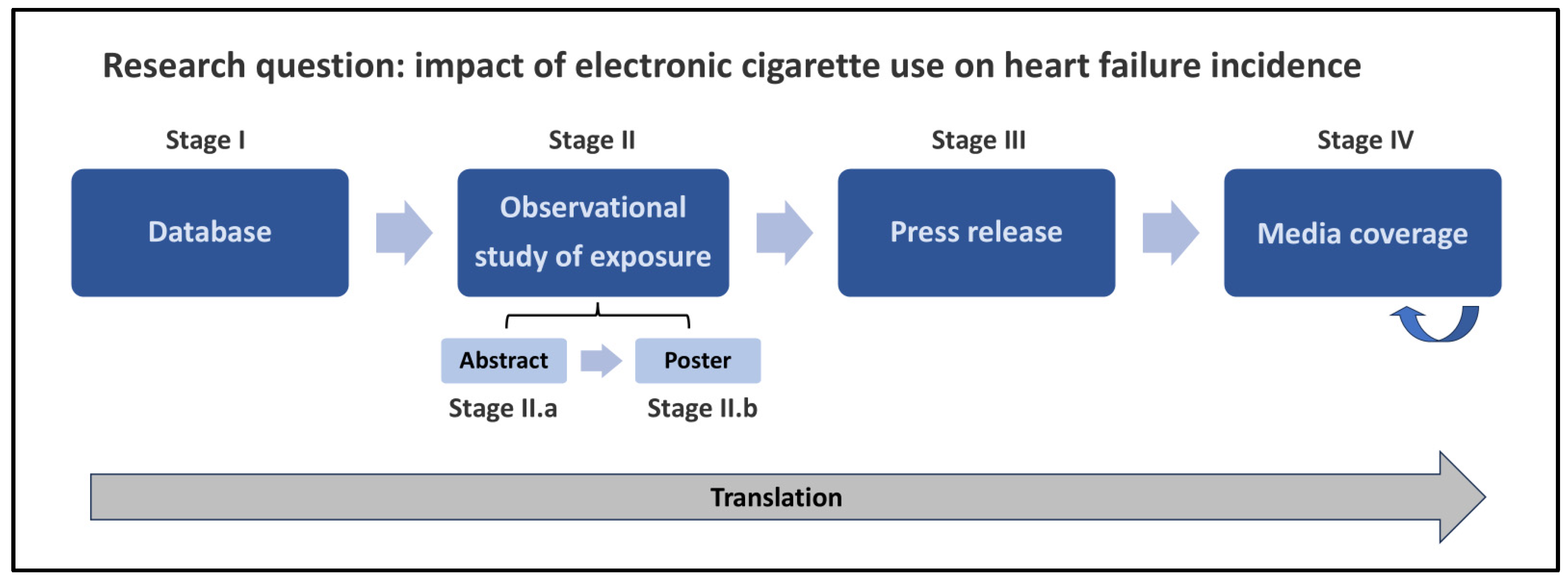

Overview

Methods

- Non-smoking EC users did not have a significant increase in heart failure incidence. As previously discussed, the press release and poster omitted this item which was only included in the abstract. Subsequently, all news reports but one omitted this finding, and one reported the opposite.

-

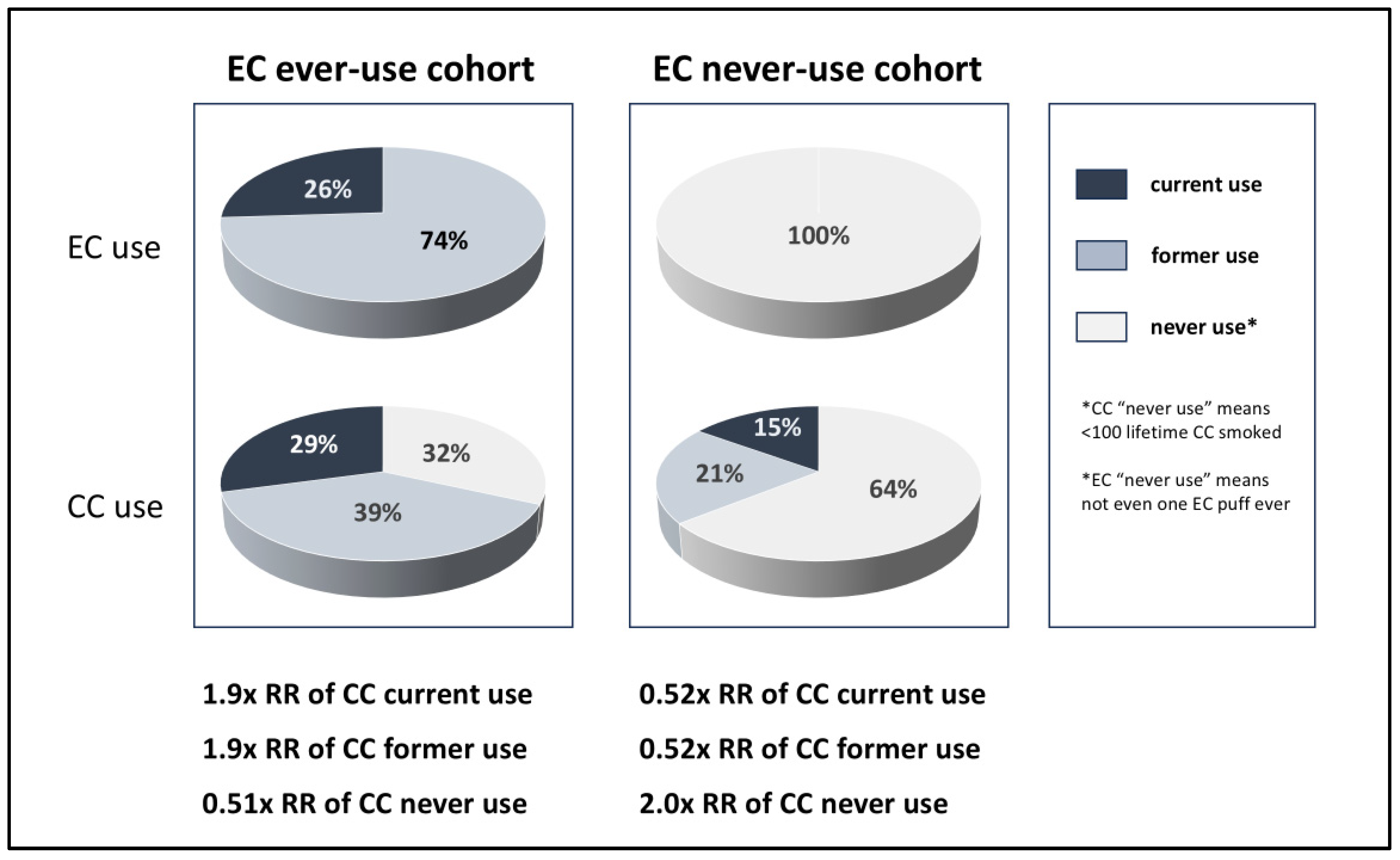

CC use was 1.9x higher in the EC use group, but CC use was surprisingly reported as having a minimal association with HF risk, calling the entire study into question. This data was omitted from the press release and most subsequent news reports.

- Medpage Today was the only site which reported that the EC group smoked CC 1.9X more than the non-EC group, and that the EC group smoked CC more than it vaped EC [13].

- Almost all news reports were not aware and/or did not question why the impact of the 1.9x difference in CC use was only a 2% increase in HF risk in the Medstar adjusted model. Two exceptions, reports by Health.com and Healthline, are discussed below.[22,26]

- 3.

-

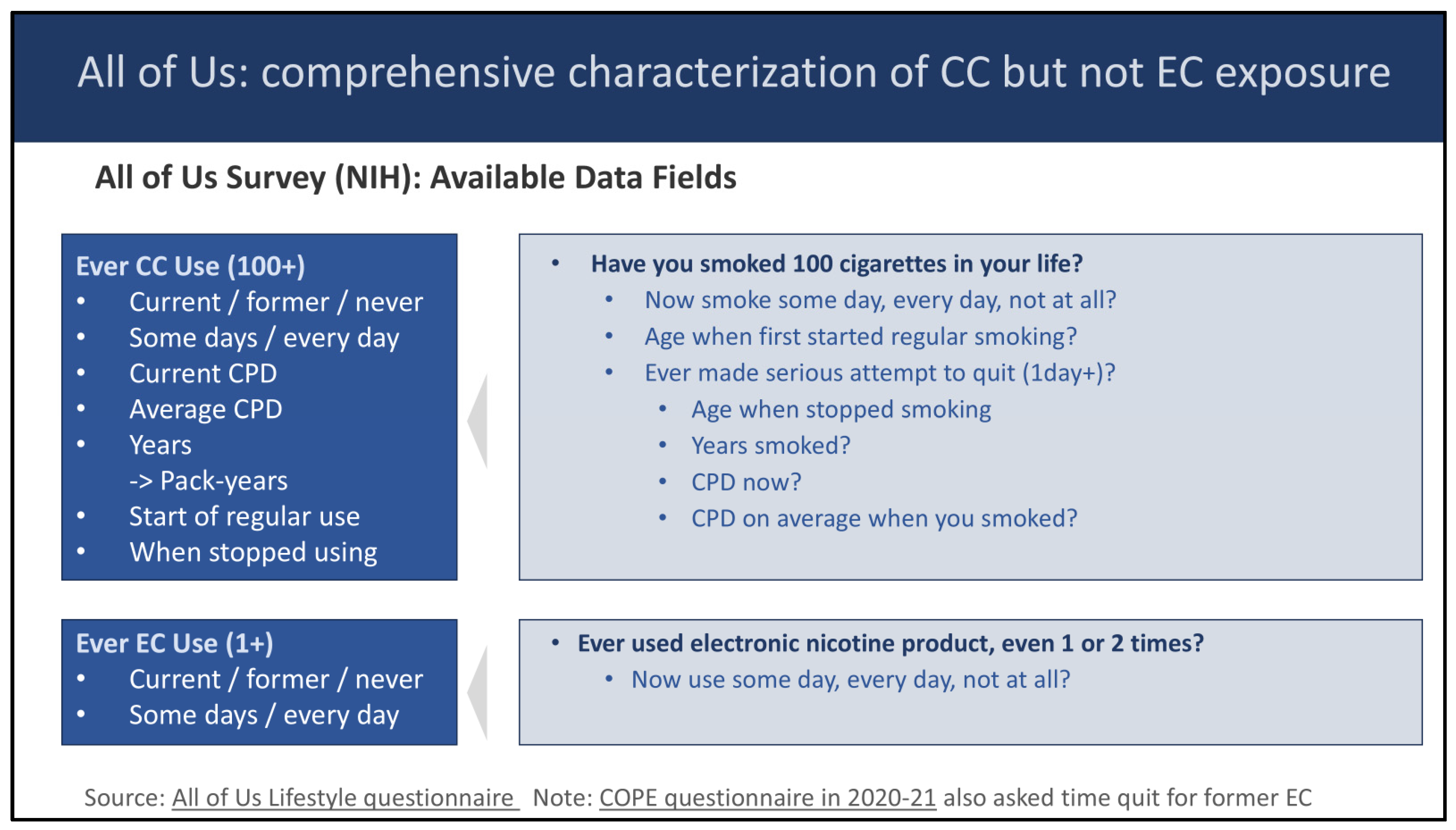

Two news reports claimed that “vaping, even once, may raise the risk of heart failure. As discussed previously, the impact of a single use of EC product was not studied by the Medstar authors; moreover, the underlying All of Us database did not collect the duration of vaping (see Figure 5).

- Medical News Today originated this claim on 4/27/24 [32]. In an email communication, the Medical News Today author asserted that a statement in the ACC press release (“people who used e-cigarettes at any point had a 19% higher risk of heart failure”) validated their headline.

- This claim was then repeated two days later by CBS News [4].

- 4.

- The Sun reported “VAPING can damage your heart even if you have never smoked cigarettes, according to a study.” [6] As previously discussed, the Medstar authors in actuality reported the opposite, that there was no significant impact in the subset of EC users who didn’t use CC. However, this was disclosed only in the abstract and not the press release.

- 5.

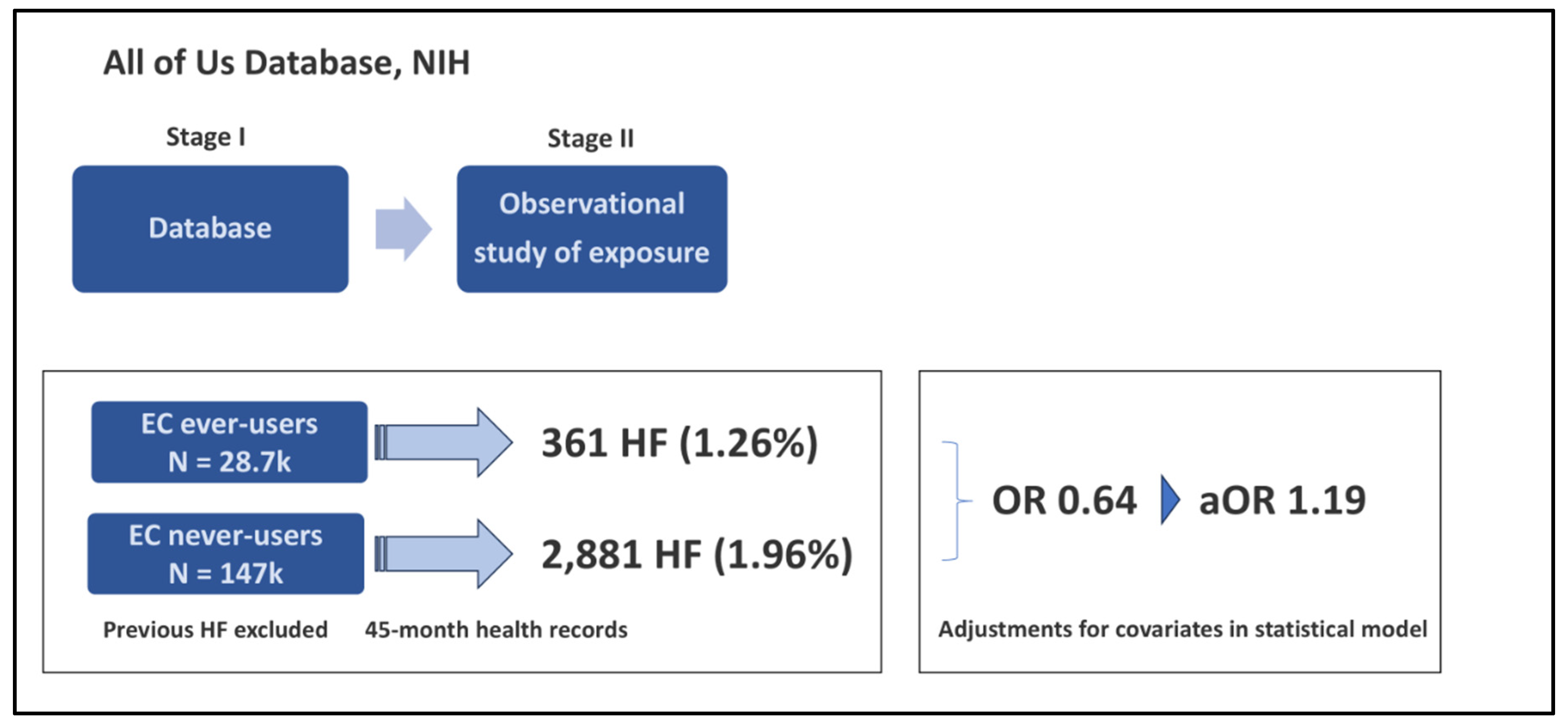

- One news site reported that “one in five EC users went on to develop heart failure.” [24] This was likely a misunderstanding of the 19% increased adjusted risk of HF reported in the EC group (which was also correctly cited elsewhere in the news article). In actuality, 1.26% of EC ever-users were diagnosed with heart failure during the prospective period, vs. 1.96% of EC never-users in the unadjusted data.

- 6.

- Dr. Nicotine Saphier, of Fox News, acknowledged, “This is not surprising… let’s be honest here. It’s great news because sometimes we need to point to these studies to really hone this in on people.” [3]

Discussion

Where Did It Go Wrong?

- 1.

-

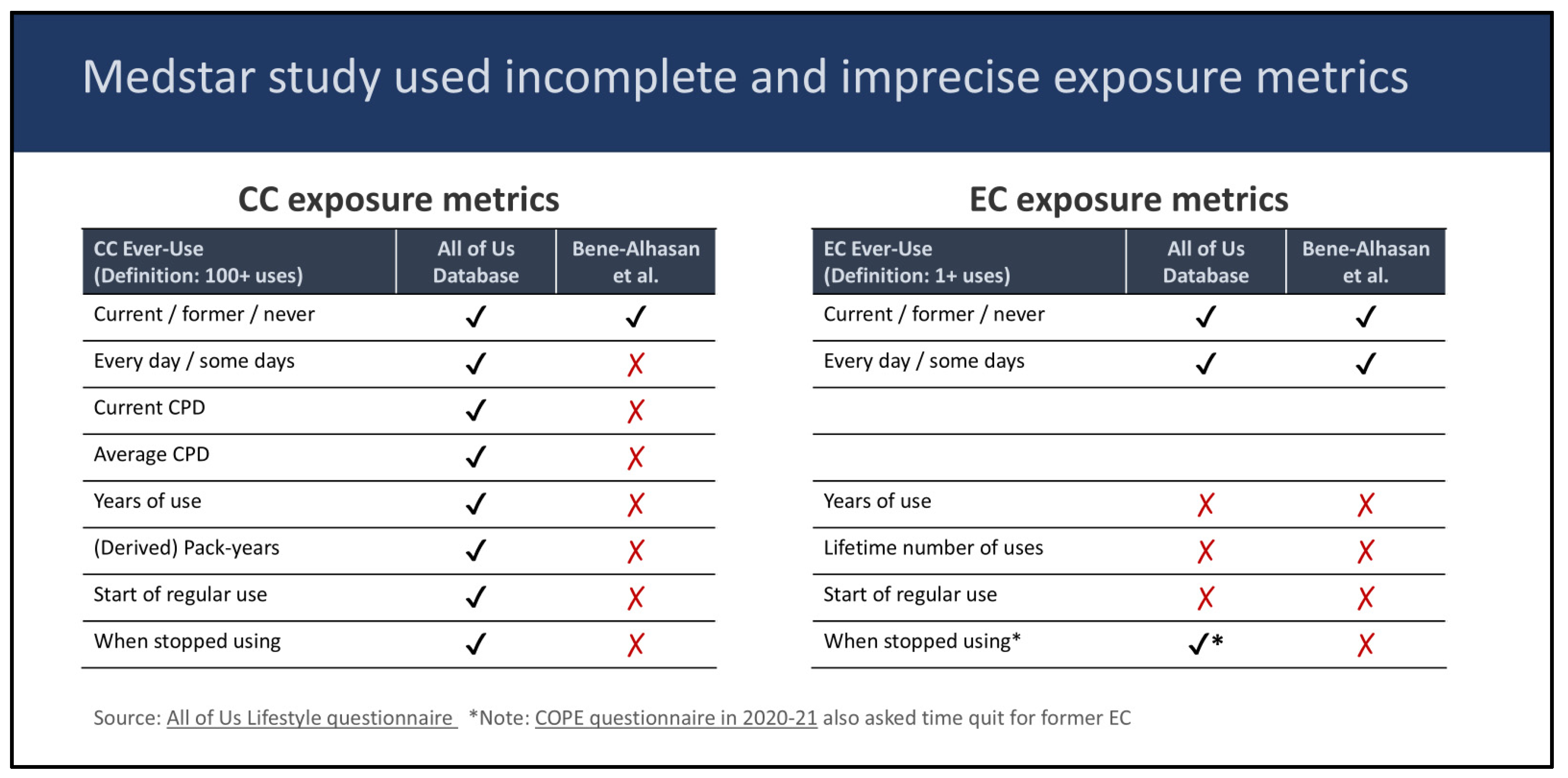

All of Us Study (NIH Database):

- Did not collect EC use duration data

- 2.

-

Abstract / Poster:

- a.

-

Imprecise measurement of EC and CC exposure

- Did not use CC use duration data available from the All of Us database.

- Did not measure EC and CC use during the prospective period.

- Used a case-control design which is especially subject to confounding if EC and CC use are not independent of each other.

- b.

- Omitted the finding that CC never use had a non-significant aOR of 1.04 in the poster.

- c.

- Did not directly report the aOR associated with CC use; rather, indirectly reported that 1.9X difference in CC use was accounted for by a 2% change in aOR.

- 3.

-

Press Release:

- Changed quote from “EC should not be used by youth” to “EC should not be used for stopping smoking” even though the study did not address this.

- Did not mention that the 1.9X increased CC smoking of the EC-ever-use group was “accounted for” as a 2% change in HF risk.

- Did however obscure this by stating that “smoking was accounted for.”

- Omitted that EC users who did not smoke did not show a significant increase in HF risk.

- Omitted that no dose response was found, in contrast to a previous year press release on the impact of cannabis by the same Medstar authors [12].

- 4.

-

News Reports

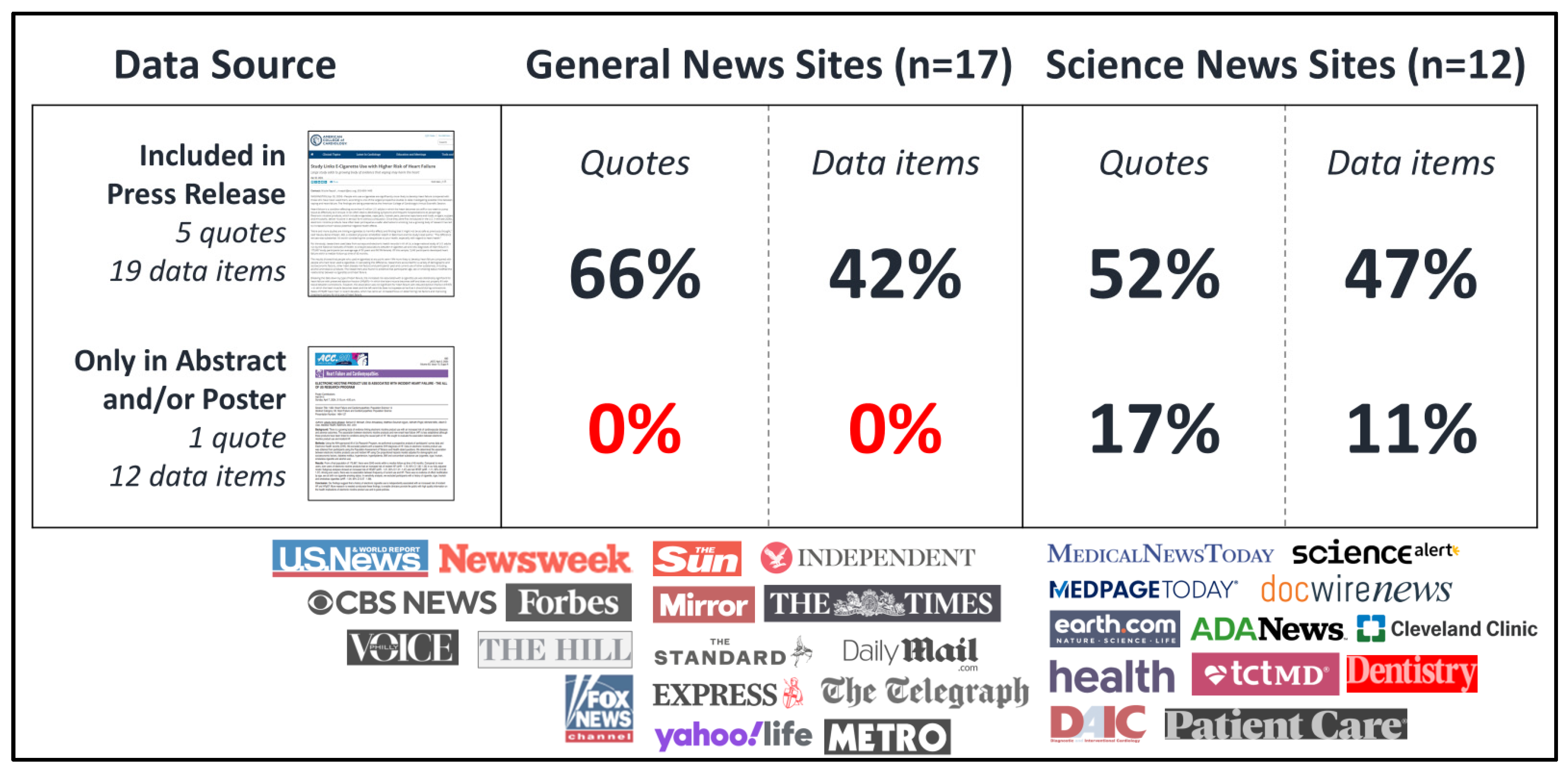

- All general news sites, and most science news sites, did not report content which was not in the press release.

- General news sites in particular relied heavily on quotations from the press release in their reporting.

- Even the science news sites did not question why CC use was viewed as harmless in this study.

- News media created and repeated a new claim that vaping even once could cause heart failure

- News media acknowledged confirmation bias in their reporting.

- Sensationalized headlines included characterization of the findings as “shocking” or indicating a “threat.” [3,14,21]

What Could Have Helped?

Lessons Learned

Postscript

Disclosures

Acknowledgments

References

- American College of Cardiology (2024) Study Links E-Cigarette Use with Higher Risk of Heart Failure. ACC.org. [Online]. Available online: https://www.acc.org/About-ACC/Press-Releases/2024/04/01/21/51/study-links-e-cigarette-use-with-higher-risk-of-heart-failure (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- NIH, National Cancer Institute (2025) Compared to smoking cigarettes, would you say that using e-cigarettes that contain nicotine is…? | HINTS[Online]. Available online: https://hints.cancer.gov/view-questions/question-detail.aspx?PK_Cycle=14&qid=1929 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Penley, T. (2024) Smoking cigarettes can destroy lungs, but shocking new study reveals why vaping can harm the heart | Fox News. Fox News. [Online]. Available online: https://www.foxnews.com/media/smoking-cigarettes-destroy-lungs-shocking-new-study-vaping-harm-heart (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Marshall, M. (2024) Could vaping one time put you at a higher risk of heart failure? - CBS Boston. CBS News. [Online]. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/boston/news/heart-failure-vaping-danger/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Buzby, S. (2024) E-cigarette use could raise heart failure risk up to 19%. Healio. [Online]. Available online: https://www.healio.com/news/cardiology/20240417/ecigarette-use-could-raise-heart-failure-risk-up-to-19 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Blanchard, S. (2024) Vaping increases your risk of deadly heart failure by a fifth, study shows. The Sun. [Online]. Available online: https://www.thesun.co.uk/health/27074532/vaping-deadly-heart-failure-risk-health/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Bene-Alhasan, Y. et al. (2024) ELECTRONIC NICOTINE PRODUCT USE IS ASSOCIATED WITH INCIDENT HEART FAILURE - THE ALL OF US RESEARCH PROGRAM. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 83, 695.

- All of Us Research Program (2025) Lifestyle Questionnaire[Online]. Available online: https://www.researchallofus.org/wp-content/themes/research-hub-wordpress-theme/media/surveys/Survey_Lifestyle_Eng_Src.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Cohen, G. and Cook, S. (2025) Observational studies of exposure to tobacco and nicotine products: Best practices for maximizing statistical precision and accuracy. iScience 28, 111985.

- Farsalinos, K.E. et al. (2019) Is e-cigarette use associated with coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction? Insights from the 2016 and 2017 National Health Interview Surveys. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease 10, 204062231987774.

- Lubin, J.H. et al. (2016) Risk of Cardiovascular Disease from Cumulative Cigarette Use and the Impact of Smoking Intensity: Epidemiology 27, 395–404.

- Bene-Alhasan, Y. et al. (2023) Abstract 13812: Daily Marijuana Use is Associated With Incident Heart Failure: “All of Us” Research Program. Circulation 148.

- Short, E. (2024) E-Cigarettes Tied to Heart Failure. Medpage Today. [Online]. Available online: https://www.medpagetoday.com/pulmonology/smoking/109470 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Johnson, A. (2024) Vaping Health Risks: Study Suggests Nearly 20% Increased Threat Of Heart Disease From E-Cigarette Use. Forbes. [Online]. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ariannajohnson/2024/04/02/vaping-health-risks-study-suggests-nearly-20-increased-threat-of-heart-disease-from-e-cigarette-use/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- DICardiology.com (2024) Study Links E-Cigarette Use with Higher Risk of Heart Failure. DAIC. [Online]. Available online: http://www.dicardiology.com/content/study-links-e-cigarette-use-higher-risk-heart-failure (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Fortinsky, S. (2024) E-cigarette users 20 percent more likely to develop heart failure: Study. The Hill.

- Jennings, S. (2024) Vaping Associated with Increased Risk of Heart Failure, According to New Research. Patient Care Online. [Online]. Available online: https://www.patientcareonline.com/view/vaping-associated-with-increased-risk-of-heart-failure-according-to-new-research (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Mundell, E. (2024) Vaping Could Raise Your Risk for Heart Failure. US News & World Report. [Online]. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2024-04-02/vaping-could-raise-your-risk-for-heart-failure (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Ionescu, A. (2024) E-cigarettes linked to increased risk of heart failure. Earth.com. [Online]. Available online: https://www.earth.com/news/e-cigarettes-linked-to-increased-risk-of-heart-failure/ (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Harris Bond, C. (2024) Vaping increases risk of heart failure by nearly 20%, study suggests. PhillyVoice. [Online]. Available online: https://www.phillyvoice.com/vaping-heart-failure-e-cigarettes-health-effects/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Pickles, K. (2024) Fresh health warning over vaping as shock study finds e-cigarettes may raise risk of heart failure | Daily Mail Online. Daily Mail. [Online]. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-13263505/vaping-study-e-cigarettes-raise-risk-heart-failure.html (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Loeppky, J. (2024) Heart Failure: E-Cigarettes Can Increase Risk By 21%. Healthline. [Online]. Available online: https://www.healthline.com/health-news/e-cigarettes-can-increase-heart-failure-risk-by-19 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Hampson, L. (2024) Vaping increases risk of heart failure by almost 20%, study finds. Yahoo Life!. [Online]. Available online: https://uk.style.yahoo.com/vape-heart-failure-study-110841496.html (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Thomas, R. (2024) Vaping could increase heart failure by 19%, study says - Dentistry. Dentistry.co.uk.

- Howse, I. (2024) Vaping increases risk of heart failure by almost 20%. Metro. [Online]. Available online: https://metro.co.uk/2024/04/02/vaping-increases-risk-heart-failure-almost-20-20571960/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Sullivan, K. (2024) Are E-Cigarettes Bad for Your Heart? New Research Suggests Vaping Could Raise Heart Failure Risk. Health.com. [Online]. Available online: https://www.health.com/study-vaping-e-cigarettes-heart-failure-8625237 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- McKeown, L.A. (2024) Vaping Linked to Higher Risk of HFpEF, NIH Data Show. TCTMD.com. [Online]. Available online: https://www.tctmd.com/news/vaping-linked-higher-risk-hfpef-nih-data-show (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Searles, M. (2024) Vaping causes substantial increase in risk of heart failure, study findsThe Telegraph.

- Watson, C. (2024) Massive Study Links Vaping to a Much Higher Risk of Heart Failure. ScienceAlert. [Online]. Available online: https://www.sciencealert.com/massive-study-links-vaping-to-a-much-higher-risk-of-heart-failure (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Dewan, P. (2024) Vaping may cause “substantial” heart failure risk increase. Newsweek. [Online]. Available online: https://www.newsweek.com/vaping-cause-substantial-heart-failure-risk-1885920 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Massey, N. and Ahmed, J. (2024) Doctors reveal what vaping can do to your heart. The Independent. [Online]. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/vaping-vapes-heart-failure-smoking-b2522832.html (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Pelc, C. (2024) Heart health: Vaping may raise heart failure risk by 19%. Medical News Today. [Online]. Available online: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/vaping-even-once-may-raise-risk-heart-failure-study-finds (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Hayward, E. (2024) Vaping linked to increased risk of heart failure[Online]. Available online: https://www.thetimes.com/uk/article/vaping-increases-risk-of-heart-failure-researchers-find-n5bw36dms (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Dillard, R. (2024) E-Cigarette Use Linked to Higher Risk of Heart Failure. Docwire News. [Online]. Available online: https://www.docwirenews.com/post/e-cigarette-use-linked-to-higher-risk-of-heart-failure (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Geissler, H. (2024) Daily Express. One million facing health alert over “harmful effects” of vapes. [Online]. Available online: https://www.pressreader.com/uk/daily-express/20240403/281977497636261 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Cleveland Clinic News Service (2024) Vaping Linked to Heart Failure, Research Shows. Cleveland Clinic. [Online]. Available online: https://newsroom.clevelandclinic.org/2024/11/20/vaping-linked-to-heart-failure-research-shows (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- American College of Cardiology (2024) Heart failure risk of vapers 20% greater. Mirror. [Online]. Available online: https://www.pressreader.com/uk/daily-mirror/20240403/281943137898006/textview (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- ADA News Service (2024) Vaping increases risk of heart disease. ADA News. [Online]. Available online: https://adanews.ada.org/huddles/vaping-increases-risk-of-heart-disease/ (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Massey, N. (2024) Vaping may increase the risk of heart failure, study suggests. The Standard. [Online]. Available online: https://www.standard.co.uk/news/science/vaping-people-uk-government-baltimore-nhs-b1149123.html (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Hogue, M. (2024) Study links heart failure risk to e-cigarette use. American Pharmacists Association. [Online]. Available online: http://www.pharmacist.com/Blogs/CEO-Blog/Article/study-links-heart-failure-risk-to-e-cigarette-use (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Steinberg, M.B. et al. (2021) Nicotine Risk Misperception Among US Physicians. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 3888–3890.

- Jensen, R.P. et al. (2015) Hidden Formaldehyde in E-Cigarette Aerosols. N Engl J Med 372, 392–394.

- FDA Center for Tobacco Products (2022) Technical Project Lead (TPL) Review of PMTAs: NJOY AceUS Food and Drug Administration.

- Rigotti, N.A. (2024) Electronic Cigarettes for Smoking Cessation — Have We Reached a Tipping Point? N Engl J Med 390, 664–665.

- Benam, K.H. (2024) Multidisciplinary approaches in electronic nicotine delivery systems pulmonary toxicology: emergence of living and non-living bioinspired engineered systems. Commun Eng 3, 123.

- Nagy, S.; et al. (2025) The Impacts of Vaping on the Cardiovascular System: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Vaid, R.; et al. (2024) Asia’s Teen Vaping Surge: Unmasking Risks and Mobilizing Solutions. Asia Pac J Public Health 36, 646–647.

- Erhabor, J. et al. (2025) E-cigarette Use and Incident Cardiometabolic Conditions in the All of Us Research Program. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G. (2024) “it’s good news”: case studies in the fact-checking of statistical bias in the scientific literature and its translation by the news media | CORESTACohen G. “it’s good news”: case studies in the fact-checking of statistical bias in the scientific literature and its translation by the news media | CORESTA [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.coresta.org/abstracts/its-good-news-case-studies-fact-checking-statistical-bias-scientific-literature-and-its (accessed on 19 April 2025).

| EC Ever-Users | EC Never-Users | HF aOR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | n=28,660 Age 40 (+/- 14) |

n=147,007 Age 54 (+/- 16) |

|

| HF Incident cases | 361 (1.26%) | 2,881 (1.96%) |

Risk of HF (unadjusted) OR = 0.64 |

| Odds ratio adjustments in the model - adjustments applied sequentially in 3 steps | |||

| Model 1 | Adjustments for age and demographic factors doubled the relative risk of HF associated with EC use in the model |

Risk of HF (adjusted) 0.64 -> 1.19 aOR of HF |

|

| Model 2 “accounted for the impact of CC smoking and substance use” |

Adjustments for tobacco and substance use reduced the EC group risk by only 2% (from 1.19 to 1.17) even though the EC group smoked CC almost twice as much as the EC non-use group | 1.19 - > 1.17 aOR of HF | |

| Model 3 (main model includes all 3 adjustments) |

Adjustments for diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia | 1.17 -> 1.19 aOR of HF aOR = 1.19 [1.04-1.34] |

|

| Medstar / ACC data releases | Date | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Abstract | 4/2/24 | Abstract published in Journal of ACC |

| Poster presentation | 4/7/24 | The 4/7 poster time of presentation was mentioned in the 4/2 press release; actual poster was released behind paywall or available from authors |

| Press release | 4/2/24 | Press release by ACC |

| Date | General news sites | Date | Science news sites | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4/2/24 | Forbes [14] | 4/2/24 | DAIC [15] | |

| 4/2/24 | The Hill [16] | 4/2/24 | Patient Care [17] | |

| 4/2/24 | US News & World Report [18] | 4/2/24 | Earth.com [19] | |

| 4/2/24 | Philly Voice [20] | 4/2/24-3/24 | MedPage Today [13] | |

| 4/2/24 | Daily Mail (UK) [21] | 4/3/24 | Healthline [22] | |

| 4/2/24 | Yahoo Life! (UK) [23] | 4/4/24 | Dentistry (UK) [24] | |

| 4/2/24 | Metro (UK) [25] | 4/11/24 | Health [26] | |

| 4/2/24 | The Sun (UK) [6] | 4/12/24 | TCTMD [27] | |

| 4/2/24 | Telegraph (UK) [28] | 4/15/24 | Science Alert [29] | |

| 4/3/24 | Newsweek [30] | 4/17/24 | Healio [5] | |

| 4/3/24 | The Independent (UK) [31] | 4/27/24 | Medical News Today [32] | |

| 4/3/24 | The Times (UK) [33] | 7/24/24 | DocWire News [34] | |

| 4/3/24 | Daily Express (UK) [35] | 11/20/24 | Cleveland Clinic [36] | |

| 4/3/24 | Mirror (UK) [37] | Not disclosed | ADA News [38] | |

| 4/3/24 | Standard (UK) [39] | Not disclosed | Pharmacist.com [40] | |

| 4/7/24 | Fox News [3] | |||

| 4/29/24 | CBS News [4] |

| Inclusion in Abstract, Poster, Press Release | Translation Frequency |

|

|||

| Abstr. | Poster | Press Rel. |

News Rpt. n=17 |

Sci. Rpt. n=12 |

|

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 100% | 100% | The results showed that people who used e-cigarettes at any point were 19% more likely to develop heart failure compared with people who had never used e-cigarettes. |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 100% | 93% | 175,667 study participants (an average age of 52 years and 60.5% female). |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 94% | 80% | “More and more studies are linking e-cigarettes to harmful effects and finding that it might not be as safe as previously thought,” said Yakubu Bene-Alhasan, MD, a resident physician at MedStar Health in Baltimore and the study’s lead author. |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 94% | 73% | Presented at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) annual scientific session |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 82% | 80% | Of this sample, 3,242 participants developed heart failure within a median follow-up time of 45 months. |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 76% | 73% | “The difference we saw was substantial. It’s worth considering the consequences to your health, especially with regard to heart health.” |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 71% | 40% | Heart failure affects 6M US adults, heart too stiff or weak |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 65% | 80% | Breaking the data down by type of heart failure, the increased risk associated with e-cigarette use was statistically significant for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)—in which the heart muscle becomes stiff and does not properly fill with blood between contractions. |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 65% | 60% | “I think this research is long overdue, especially considering how much e-cigarettes have gained traction,” |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 65% | 60% | “We don’t want to wait too long to find out eventually that it might be harmful, and by that time a lot of harm might already have been done. With more research, we will get to uncover a lot more about the potential health consequences and improve the information out to the public.” |

| ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | 53% | 33% | EC have been portrayed as safer but growing research lead to increased concern |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 47% | 7% | 5-10% of teens and adults use EC. Surgeon General called youth EC use an epidemic* |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 35% | 73% | Accounted for demographic, socioeconomic, heart disease factors, and current use of other substances, including alcohol and tobacco products. |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 35% | 53% | Bene-Alhasan said EC are not recommended for quitting smoking*** |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 35% | 40% | Researchers said the new study findings point to a need for additional investigations of the potential impacts of vaping on heart health, especially considering the prevalence of e-cigarette use among younger people. |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 35% | 40% | Bene-Alhasan said this study was one of the most comprehensive / largest studies to date |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 35% | 40% | EC impact on HFrEF was not significant |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 29% | 67% | Study used the All of Us database from NIH |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 29% | 40% | Results align with previous studies in animals and humans, though some studies inconclusive |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 29% | 40% | Researchers said the observational design allows them to infer, but not conclusively determine a causal relationship |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 29% | 20% | Rates of HFpEF have risen in recent decades, increased focus on determining risk factors |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 18% | 47% | People who use e-cigarettes are significantly more likely to develop heart failure compared with those who have never used them (2nd mention, without 19% statistic) |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 18% | 47% | No evidence that age, sex or smoking status modified the relationship between EC and HF |

| ✘ | ✘ | ✔ | 18% | 20% | Bene-Alhasan said previous studies had limitations including smaller sizes |

| ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | 6% | 27% | Electronic nicotine products include e-cigarettes, and deliver nicotine in aerosol form without combustion. |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 33% | HFpEF aOR 1.21 [1.01-1.47], HFrEF aOR 1.11 CI [ 0.90-1.37] |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 27% | Dual users had 59% increased risk of incident HF |

| ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | 0% | 27% | PATH-styled questions on EC use. |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 27% | EC ever-use: aOR for HF 1.19, 95% CI [1.06 -1.35] in the fully adjusted model factoring in all covariates. |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 13% | Exclusion: patients with baseline HF diagnosis |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 13% | 70% were White, 20% were Black, and 10% were Asian or Hispanic |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 13% | Conclusion: Electronic nicotine product use should be discouraged among the youths while further studies are conducted |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 7% | Inclusion: Adults 18+ |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 7% | EC ever-user group: current EC use 27%, current CC use 29% (EC group smoked more than it vaped). |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 7% | EC never-use group: current CC use 15% |

| ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | 0% | 7% | No difference between EC current users who were every-day and some-day users (no dose-response) |

| ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | 0% | 7% | Conclusion: More research is needed to corroborate these findings, to enable clinicians to provide the public with high quality information on the health implications of electronic nicotine product use and to guide policies. |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 7% | EC ever-users n=28,660 EC never-users n=147,007 |

| ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | 0% | 7% | EC exclusive users (never smokers) had 4% increased risk, CI [0.57-1.89] (not significant). |

| ✘ | ✔ | ✘ | 0% | 0% | The impact of a 1.9x difference in CC use in the EC group was only a 2% increase in HF risk in the fully adjusted model |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).