Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

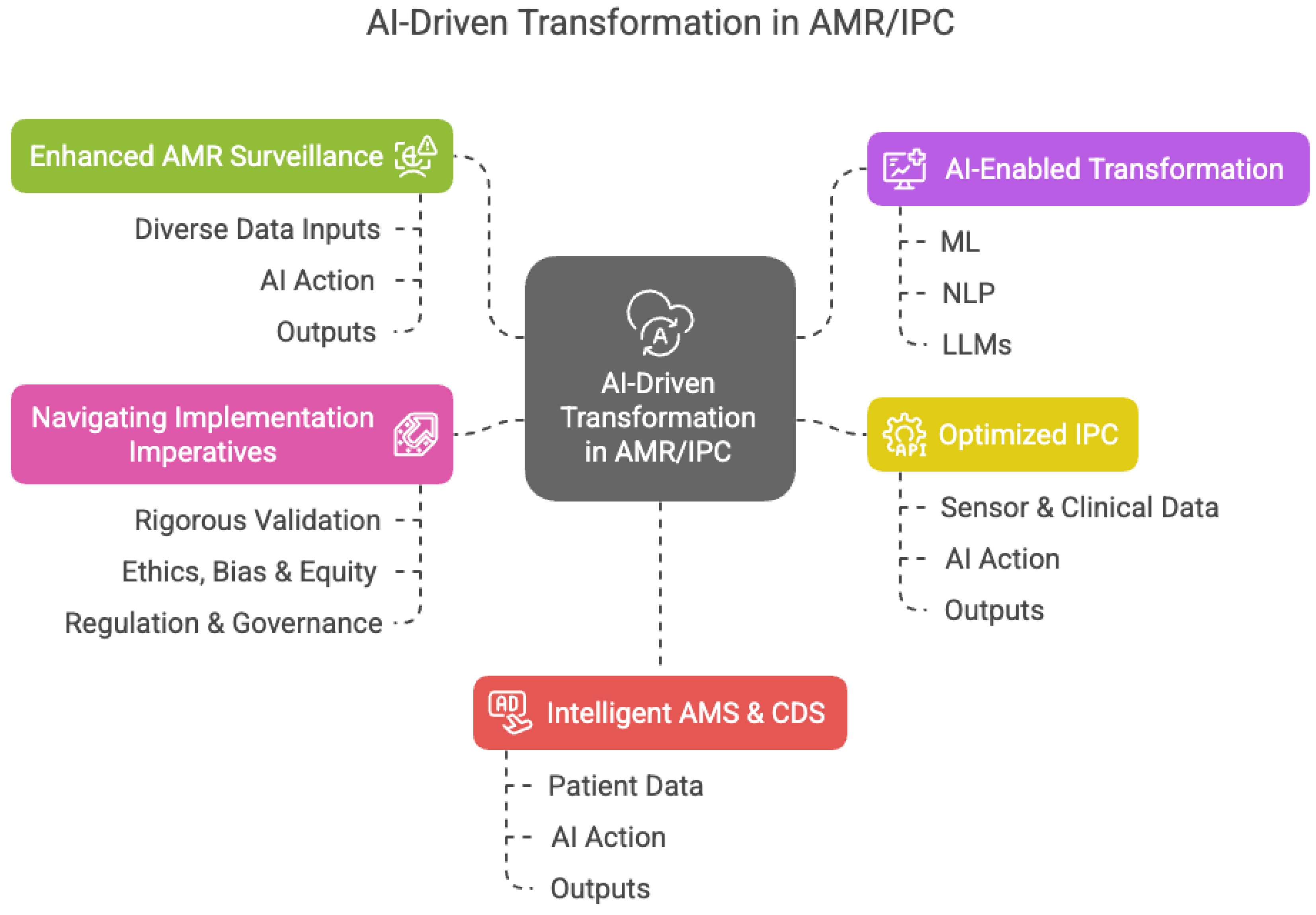

1. Introduction: A Confluence of Crises and Capabilities at a Critical Tipping Point

- Synthesize diverse knowledge: Dynamically integrate guidelines, formularies, real-time local antibiograms (crucial given demonstrated regional variations in resistance), complex patient EHR data (including unstructured notes), genomic data, and research findings.

- Identify complex patterns: Detect early outbreak signals or predict resistance risk by analyzing multi-modal data streams, potentially identifying trends far faster than traditional surveillance allows. This is vital for tracking rapidly increasing threats like carbapenem resistance.

- Personalize guidance: Tailor antimicrobial and IPC recommendations based on individual patient factors, pathogen genomics, real-time local resistance epidemiology, and stewardship principles, offering precise decision support.

- Automate processes: Enhance IPC efficiency through automated surveillance, adherence monitoring, and contact tracing.

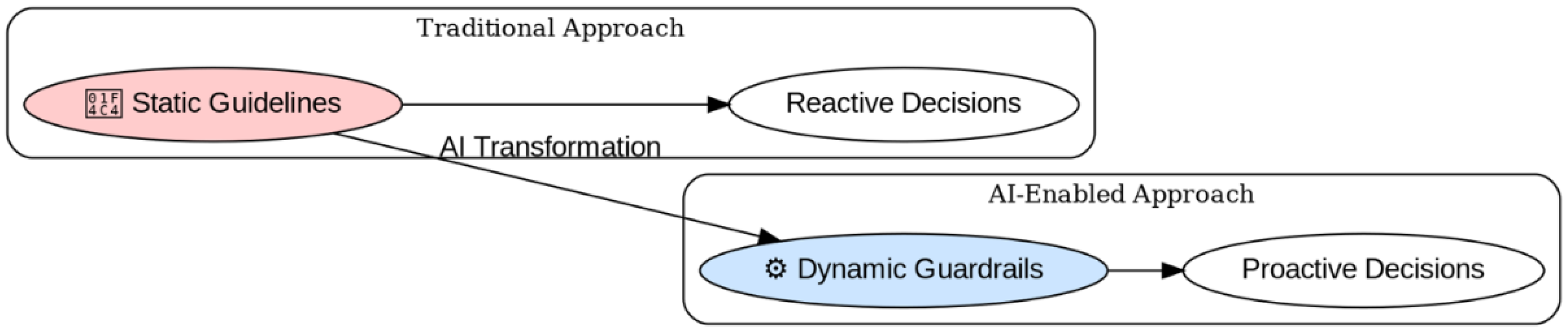

2. From Static Documents to Dynamic Decision Support: Reimagining Guideline Implementation

- Integrate Multi-Source Data Dynamically: Continuously synthesize guidelines, regulations, AWaRe classifications, frequently updated local/regional antibiogram data reflecting real trends [6], formulary information, and patient-specific EHR data [13,14]. ML algorithms can effectively model the complex interactions influencing resistance [14].

- Generate Context-Sensitive, Reasoned Outputs: Provide nuanced recommendations tailored to the specific clinical scenario and local resistance context. For example, when treating a suspected Gram-negative infection in a region with high documented carbapenem resistance [3], the system could prioritize alternative agents or combination therapies based on integrated evidence and local susceptibility data, explaining the rationale [14].

- Standardize Terminology and Facilitate Interoperability: Use LAMs to map local terms to standardized codes, improving data quality for surveillance that can feed into burden estimation models and enabling communication between systems. This is something Campania Region has engaged as system to link different healthcare priority [https://www.forumriskmanagement.it/atti2024/formaforum/Borriello.pdf].

- Enable Real-Time Updates and Learning: Incorporate new evidence and resistance alerts rapidly [3]. Future systems might incorporate feedback loops learning from local treatment outcomes to refine guidance, although requiring rigorous validation [6].

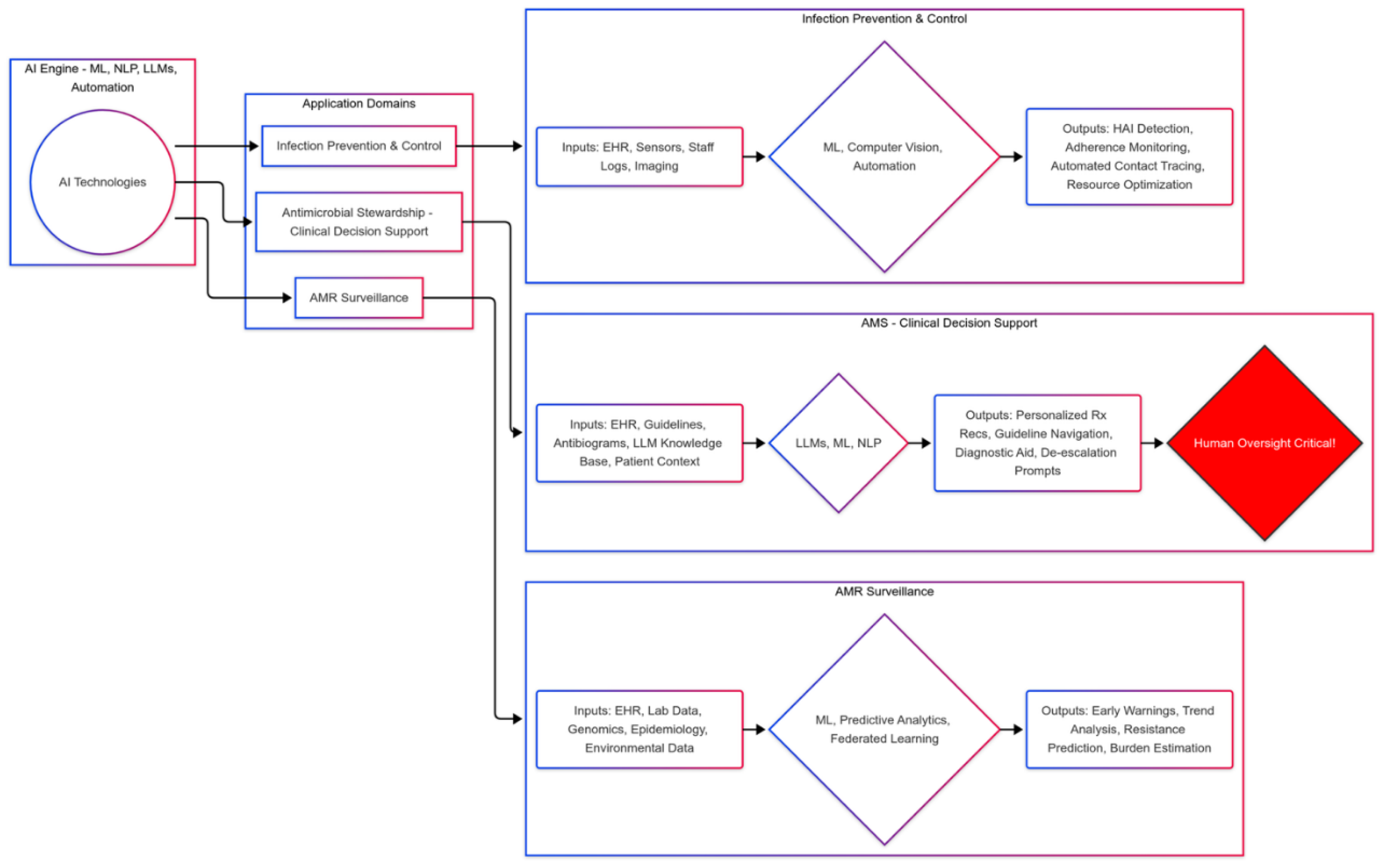

3. Expanding the Frontier: Concrete Applications in Computationally-Enhanced Infection Management

3.1. Revolutionizing AMR Surveillance with Predictive Analytics and Federated Systems

- Real-Time Pattern Recognition and Prediction: ML algorithms detect statistically significant deviations in resistance patterns or HAI clusters earlier than traditional methods [9,10,11,14]. Predictive models can forecast outbreaks or stratify patient risk, potentially focusing resources on high-burden pathogens like MRSA or specific resistant Gram-negatives identified in burden studies [3,6].

- Federated Learning for Scalable, Private Collaboration: Crucial for overcoming data privacy barriers and addressing data scarcity highlighted in global burden studies [15]. By enabling collaborative model training across diverse institutions (including those in data-sparse regions) without sharing raw patient data, federated learning can generate more robust, representative surveillance insights and improve the accuracy of burden estimation in LMICs [9,10,11,14,15].

- Integrating Diverse Data Streams: AI facilitates analysis of pathogen WGS data for transmission tracking [3]. Future systems could integrate pharmacy data, environmental surveillance (e.g., wastewater), and animal health data to provide a comprehensive One Health perspective, crucial for understanding AMR drivers beyond direct human infection [3]. AI could potentially identify correlations between these data streams and the AMR burden trends documented by Naghavi et al. [3].

3.2. Automating and Optimizing Infection Prevention and Control (IPC)

- Intelligent Monitoring and Automated Alerts: Systems analyze sensor and clinical data, automating tasks like hand hygiene monitoring and flagging patients for targeted IPC interventions based on risk factors or potential HAI development [16,17,18]. This can free up IPC professionals to focus on implementing interventions targeting high-burden HAIs [16].

- Streamlined Response and Optimized Resource Allocation: Automation speeds up contact tracing and predictive analytics optimize resource use (e.g., cleaning, PPE, isolation capacity), potentially leading to more efficient and effective outbreak management [19].

3.3. Empowering Clinicians with Advanced Decision Support Systems

- Knowledge Dissemination and Stewardship Support: Systems act as accessible knowledge resources, interpreting guidelines and supporting diagnostic/antimicrobial stewardship, particularly for non-specialists [1,2,3,20]. They can help clinicians navigate the complexity of managing infections caused by pathogens identified as high-burden threats [12].

- Personalized Therapeutic Optimization: CDS integrating patient data with real-time local resistance trends (informed by surveillance mirroring GBD findings [3]) can recommend optimized therapy, promoting narrow-spectrum use where possible and guiding choices against resistant organisms like MRSA or CRE [2,3]. Personalized antibiograms generated by ML [21] are a key example.

- Addressing Current System Limitations & Cognitive Load: The documented unreliability of current LLMs in complex clinical reasoning, their potential for hallucination, and struggles with nuanced interpretation remain major safety concerns [21,22]. Validation studies show performance varies significantly by task complexity [21]. While AI can potentially reduce cognitive load by synthesizing complex information, poorly designed systems risk increasing it through excessive or poorly timed alerts (alert fatigue) and demanding complex interactions [21]. The probabilistic nature requires users to understand outputs are predictions based on patterns, not deterministic truths, necessitating critical evaluation.

- Critical Oversight is Non-Negotiable: These tools augment, not replace, human judgment [12]. Clinicians must critically appraise outputs, verify against primary sources, and integrate suggestions with clinical context, especially considering the potential life-and-death consequences highlighted by AMR burden data [2,3,6].

4. Navigating the Labyrinth: Critical Ethical, Legal, and Regulatory Considerations

- Safety, Accuracy, and Reliability: Rigorous validation against diverse, representative datasets is paramount, including specific testing in populations disproportionately affected by AMR (e.g., older adults, specific geographic regions [2,3]) [12]. Continuous monitoring and strategies to mitigate LLM limitations (hallucinations, variability) are essential [21,22].

- Bias and Fairness: Algorithmic bias can amplify health inequities, particularly if models are trained primarily on data from well-resourced settings while the AMR burden is highest elsewhere [9,10,11,12,21,22]. Mitigation requires diverse datasets, fairness audits, and conscious efforts to ensure equitable access and benefit [9,10,11,12].

- Explainability and Transparency (XAI - Explainable Artificial Intelligence): Understanding system reasoning is crucial for trust [20]. While XAI methods offer insights [4], true transparency about limitations and data provenance is vital [23].

- Data Privacy and Security: Adherence to GDPR/HIPAA and use of privacy-preserving techniques are mandatory [12,24,25].

- Accountability and Liability: Clear legal frameworks defining responsibility are needed [12,24,25].

- Regulatory Oversight and Global Disparities: Evolving frameworks (EU AI Act, FDA SaMD) provide guidance in some regions [12,24,25,26]. However, the significant disparity in regulatory capacity between high-income countries and many LMICs poses a major global risk [24,25,26]. Lack of effective governance in high-AMR-burden regions could lead to unsafe AI deployment or hinder the adoption of beneficial tools, allowing resistance to spread globally. International bodies and wealthier nations have a responsibility to support regulatory capacity building and promote adaptable standards in LMICs, leveraging data like the GBD AMR study to prioritize efforts [12,24,25,26].

-

Rigorous Validation (The Validation Roadmap): As previously argued. [12], clinical AI requires validation akin to therapeutics. This implies a structured, phased approach:

- ○

- Phase 1/2 Equivalents: Focus on technical validation, feasibility, usability, and safety in controlled or simulated settings. Establish accuracy against ground truths, assess workflow integration potential, and refine algorithms based on early feedback. Define clear performance metrics beyond simple accuracy (e.g., sensitivity/specificity for specific tasks, calibration).

- ○

- Phase 3 Equivalents: Prospective, adequately powered clinical trials (ideally RCTs, potentially pragmatic trials or stepped-wedge designs) comparing AI-augmented practice against the current standard of care. Primary endpoints should be clinically relevant outcomes (e.g., patient mortality, length of stay, HAI rates, appropriate antibiotic use duration, resistance emergence rates, adverse events) and secondary endpoints could include process measures (guideline adherence, time to optimal therapy) and human factors (clinician satisfaction, workload impact) [12,24]. Sample sizes must be sufficient for subgroup analyses (e.g., by age, comorbidity, setting).

- ○

- Phase 4 Equivalents: Post-market surveillance in real-world settings to monitor long-term effectiveness, detect rare adverse events or safety issues, assess performance drift, and evaluate generalizability across diverse populations and evolving clinical practices [12,24]. This necessitates ongoing data collection and analysis infrastructure.

4.1. Methodological Considerations in System Evaluation

- Study Design: Prioritizing prospective designs (RCTs, implementation studies) assessing impact on clinically relevant outcomes, particularly in diverse settings reflecting global AMR burden [4,6].

- Validation Practices: Adopting standardized protocols emphasizing external validation across different populations/systems, transparent reporting of performance metrics (including fairness and subgroup analyses) [20,22].

- Reporting Transparency: Consistent use of guidelines (TRIPOD, STARD-AI, CONSORT-AI) detailing data, methods, performance, limitations, and code/model availability where feasible [23,24,25].

- Implementation Science: Rigorously evaluating usability, workflow integration (including cognitive load impact), cost-effectiveness, and health equity alongside technical performance [12,23,24,25]. User-centered design methodologies should be integral, not an afterthought.

5. Envisioning the Future: Towards an Integrated, Computationally-Enabled Stewardship Ecosystem

- Federated Architecture: Enabling privacy-preserving analysis across diverse settings, crucial for capturing global AMR trends and developing generalizable models [15].

- Seamless Workflow Integration & Human Factors Engineering: Embedding validated tools into clinical systems with user-centered interfaces (UCD) that minimize disruption and optimize cognitive load [27]. This requires co-design with end-users (clinicians, IPC staff, pharmacists) throughout the development process, focusing on intuitive data presentation, efficient interaction paradigms, and managing alert frequency and relevance to avoid fatigue. Cognitive ergonomics must be a primary design consideration.

- Dynamic, Learning Knowledge Systems: Continuously updated "living guidelines" informed by global evidence and real-time local/regional surveillance reflecting actual burden shifts [28].

- Augmented Clinical and Public Health Teams: Systems handling complex analytics, freeing human experts for interpretation, intervention, and addressing equity issues revealed by burden data [29].

- Robust Interdisciplinary Governance: Oversight structures involving diverse stakeholders to guide ethical development, ensure fair access, and monitor real-world impact [24,30,31].

- Bridging Care Interfaces and One Health Integration: Facilitating data flow across healthcare settings and integrating human, animal, and environmental surveillance data for a holistic approach, guided by understanding where the AMR burden is highest [3,12,15]. Scenario modeling [3] underscores the need to embed AI within wider health system strengthening efforts.

6. Conclusion

Call to Action: Building Intelligent and Equitable Guardrails for a Resilient Future

- Investment in High-Quality Validation Research: Prioritizing prospective, multi-center trials (including RCTs and implementation studies) focusing on clinically relevant outcomes, safety, and human factors, especially in high-burden regions [3,4,6]. Define clear metrics for efficacy based on the phased validation model [5].

- Development of Secure Data Infrastructure and Standards: Fostering federated networks and interoperability to enable secure, equitable data sharing [15,24,25,36].

- Global Cooperation on Regulation, Equity, and Capacity Building: Working towards harmonized or adaptable regulatory standards, promoting ethical AI principles, and providing targeted support to LMICs for infrastructure and governance, informed by AMR burden data [12,24,25,33,34,37].

- Enhanced Clinician Training and Human-Centered Design: Equipping professionals for critical AI use and designing tools through co-design processes that genuinely augment clinical workflows and manage cognitive load effectively [12,35].

- Promotion of Transparent, Interdisciplinary Governance: Establishing robust oversight structures for the entire AI lifecycle [12,33,34].

- Adherence to Therapeutic-Level Validation Benchmarks: Ensuring clinical AI systems undergo scrutiny appropriate for their impact on patient safety, following a structured, phased validation pathway [3,12,19,20].

Acknowledgments

References

- Chetty, S.; Swe-Han, K.S.; Mahabeer, Y.; Essack, S.Y. Interprofessional education in antimicrobial stewardship, a collaborative effort. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 6, dlae054. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Aguilar, G.R.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [CrossRef]

- McDonnell A, Countryman A, Laurence T, et al (2024). – Forecasting the Fallout from AMR: Economic Impacts of Antimicrobial Resistance in Humans – A report from the EcoAMR series. Paris (France) and Washington, DC (United States of America): World Organisation for Animal Health and World Bank, pp. 58. [CrossRef]

- Olesińska, W.; Biernatek, M.; Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S.; Piątek, J. Systematic Review of the Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Systems and Society—The Role of Diagnostics and Nutrition in Pandemic Response. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2482. [CrossRef]

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–1465. [CrossRef]

- Francke AL, Smit MC, de Veer AJ, Mistiaen P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:38. [CrossRef]

- Ho CS, Wong CTH, Aung TT, Lakshminarayanan R, Mehta JS, Rauz S, McNally A, Kintses B, Peacock SJ, de la Fuente-Nunez C, Hancock REW, Ting DSJ. Antimicrobial resistance: a concise update. Lancet Microbe. 2025 Jan;6(1):100947. [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, D.R.; Guastavino, S.; Marelli, C.; Murgia, Y.; Mora, S.; Signori, A.; Rosso, N.; Giacomini, M.; Campi, C.; Piana, M.; et al. Antibiotics and Artificial Intelligence: Clinical Considerations on a Rapidly Evolving Landscape. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2025, 14, 493–500. [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, F.; Pinto, A.; Ricciardi, G.E.; Signorelli, C.; Gianfredi, V. The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Models in Antimicrobial Stewardship in Public Health: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics (Basel) 2025, 14, 134. [CrossRef]

- El Arab, R.A.; Almoosa, Z.; Alkhunaizi, M.; Abuadas, F.H.; Somerville, J. Artificial intelligence in hospital infection prevention: an integrative review. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1547450. [CrossRef]

- Perrella, A.; Bernardi, F.F.; Bisogno, M.; Trama, U. Bridging the gap in AI integration: enhancing clinician education and establishing pharmaceutical-level regulation for ethical healthcare. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1514741. [CrossRef]

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Scales, N.; Chowdhery, A.; Heneghan, C.; Fiedel, N.; Suleman, M.; et al. Large Language Models Encode Clinical Knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, A.; Hoffman, S.C.; Das, P.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C. Challenges and applications of artificial intelligence in infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 3, 2. [CrossRef]

- Sheller, M.J.; Edwards, B.; Reina, G.A.; Martin, J.; Pati, S.; Kotrotsou, A.; Milchenko, M.; Xu, W.; Marcus, D.; Colen, R.R.; et al. Federated learning in medicine: facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12598. [CrossRef]

- Baddal B, Taner F, Uzun Ozsahin D. Harnessing of Artificial Intelligence for the Diagnosis and Prevention of Hospital-Acquired Infections: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024 Feb 23;14(5):484. [CrossRef]

- Tsai WC, Liu CF, Ma YS, Chen CJ, Lin HJ, Hsu CC, et al. Real-time artificial intelligence system for bacteremia prediction in adult febrile emergency department patients. IntJMedInform.(2023) 178:105176. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Balado Á, Castresana Méndez C, Herrero González A, Mesón Gutierrez R. de las Casas Cámara G, Vila Cordero B, et al. Using artificial intelligence to reduce orthopedic surgical site infection surveillance workload: Algorithm design, validation, and implementation in 4 Spanish hospitals. Am J Infect Control. (2023) 51:1225–9. [CrossRef]

- Barchitta M, Maugeri A, Favara G, Riela PM, Gallo G, Mura I, et al. A machine learning approach to predict healthcare-associated infections at intensive care unit admission: findings from the SPIN-UTI project. J Hosp Infect. (2021) 112:77–86. [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.-H.; Beam, A.L.; Kohane, I.S. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 719-731. [CrossRef]

- Behnke M, Valik JK, Gubbels S, Teixeira D, Kristensen B, Abbas M, et al. Information technology aspects of large-scale implementation of automated surveillance of healthcare-associated infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2021) 27:S29– 39. [CrossRef]

- Ren R, Wang Y, Qu Y, Zhao WX, Liu J, Tian H, Wu H, Wen J-R, Wang H. Investigating the Factual Knowledge Boundary of Large Language Models with Retrieval Augmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.11019, 2023.

- Tjoa E, Guan C. A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Toward Medical XAI. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021 Nov;32(11):4793-4813. Epub 2021 Oct 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, F.; Kather, J.N.; Johner, C.; et al. Navigating the European Union Artificial Intelligence Act for Healthcare. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 210. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act). COM/2021/206 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Palaniappan, K.; Lin, E.Y.T.; Vogel, S. Global regulatory frameworks for the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the healthcare services sector. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12, 562. [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, J. et al. Developing a User-Centered Digital Clinical Decision Support App for Type 2 Diabetes: Applying Human Factors Methods to Reduce Cognitive Load. JMIR Hum. Factors 9, e33470 (2022).

- Elliott, J. H. et al. From Conventional to Living Guidelines—Faster Updates for Better Patient Care. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 140, 204–212 (2021.

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.-H., Beam, A. L. & Kohane, I. S. Artificial Intelligence in Health Care. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2, 719–731 (2018). Reviews how AI tools can augment rather than replace human teams across clinical and public health workflows.

- N.I.; Gheorghe, G.; Ionescu, V.A.; Tiucă, L.-C.; Diaconu, C.C. The Role of ChatGPT and AI Chatbots in Optimizing Antibiotic Therapy: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Antibiotics (Basel) 2025, 14, 60. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence for Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029200.

- Rajkomar, A.; Hardt, M.; Howell, M.D.; Corrado, G.; Chin, M.H. Ensuring Fairness in Machine Learning to Advance Health Equity. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 866–872. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Fostering a European approach to Artificial Intelligence (Coordinated Plan on AI). COM/2021/205 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- N.I.; Gheorghe, G.; Ionescu, V.A.; Tiucă, L.-C.; Diaconu, C.C. The Role of ChatGPT and AI Chatbots in Optimizing Antibiotic Therapy: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Antibiotics (Basel) 2025, 14, 60. [CrossRef]

- Perrella A, Bisogno M. The strength and resilience of Italy's health data system. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2025 Mar 1;51:101255. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509763 (accessed on 13/03/2025).

| Category | Challenge | Proposed Mitigation Strategy / Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical / Social | Algorithmic Bias & Health Equity | Use diverse, representative datasets; conduct fairness audits; employ bias mitigation techniques; ensure equitable access to technology; involve diverse stakeholders in design. |

| Data Privacy & Confidentiality | Implement robust privacy-preserving techniques (federated learning, differential privacy, encryption); adhere strictly to GDPR/HIPAA; ensure transparent data governance. | |

| Accountability & Liability | Develop clear legal frameworks defining responsibilities (developers, implementers, clinicians); maintain comprehensive, immutable audit trails; establish shared responsibility models. | |

| Technical / Data | Data Quality, Standardization & Interoperability | Promote standardized data formats (e.g., FHIR); invest in data infrastructure; implement data quality checks; encourage data sharing agreements; use NLP for unstructured data. |

| Model Reliability, Accuracy & Robustness (incl. LLM Hallucinations) | Conduct rigorous, standardized validation (internal & extensive external); continuous post-deployment monitoring; use techniques like retrieval-augmented generation; report confidence scores. | |

| Explainability & Transparency (XAI) | Employ XAI methods (e.g., SHAP, LIME) where appropriate; prioritize transparency about model limitations, training data, and intended use; balance performance with interpretability. | |

| Validation Rigor & Consistency | Mandate prospective, multi-center validation studies against clinical benchmarks; adhere to reporting guidelines (TRIPOD, STARD-AI); assess real-world clinical outcomes. | |

| Operational / Implementable | Workflow Integration & Usability | Employ user-centered design principles; ensure seamless integration with EHRs/existing systems; develop intuitive interfaces; conduct usability testing with end-users. |

| Clinician Trust, Training & Adoption | Implement comprehensive education on AI capabilities/limitations; foster critical appraisal skills; engage clinicians early in development; demonstrate value proposition clearly. | |

| Resource Constraints & Infrastructure | Invest in necessary IT infrastructure; develop scalable and adaptable solutions for varied resource settings; explore cost-effective models; prioritize based on burden/need. | |

| Regulatory / Global | Fragmented Global Regulations & Standards | Foster international collaboration (e.g., via WHO) for harmonized or adaptable standards; develop clear guidelines for development, validation, and deployment. |

| Lack of Capacity & Resources in LMICs | Provide technical assistance and capacity-building support to LMICs; ensure AI solutions are designed considering LMIC contexts; promote equitable global access. | |

| Need for Post-Market Surveillance | Establish mechanisms for ongoing monitoring of deployed AI systems for safety, performance drift, and unintended consequences, mirroring pharmaceutical practices. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).