1. Introduction

Bird migrations are one of the largest migrations in nature. Their migratory routes, which span nearly the entire globe, shape ecosystems along their way [

1]. However, various human activities – such as unregulated infrastructural and urban development, unsustainable agriculture, illegal hunting and climate change – can highly disrupt migratory bird routes and make these species exceptionally vulnerable in their search for food and nesting sites [

2].

In the search for a solution to this problem, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary in the aspects of sustainable urban development and urban biodiversity, which are important subjects of development agendas at both the European and global levels. Within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, under the section

“Our vision”, it calls for “One [World] in which development and the application of technology are climate-sensitive, respect biodiversity and are resilient. One in which humanity lives in harmony with nature and in which wildlife and other living species are protected. “ This task combines various aspects of sustainable development, defined by Chapters 9 (

Build resilient infrastructure), 11 (

Sustainable cities and communities), and 15 (

Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems) [

3]. Furthermore, On European level, The Birds Directive (Directive 79/409/EEC) was adopted in 1979, making it one of the first pieces of environmental legislation to be adopted by the EU. It states: “Whereas the species of wild birds naturally occurring in the European territory of the Member States are mainly migratory species; whereas such species constitute a common heritage and whereas effective bird protection is typically a trans-frontier environmental problem entailing common responsibilities. “ [

4] Regarding this document, The European Union highlights various perils that hinder their protection: “Habitat loss and degradation are the most serious threats to their conservation. Urban sprawl and transport networks have fragmented and reduced the birds’ habitats. Intensive agriculture, forestry, and the use of pesticides have diminished their food supplies, resting places and nesting habitats. They are also heavily impacted by pollution, unsustainable hunting, inadequate building designs and illegal killing. “ [

5]

However, the historical neglect of bird migration in urban planning is particularly visible in the case of Belgrade, a booming capital city of Serbia, with over 1.6 million residents [

6]. The specific structure of Belgrade consists of three spatial-urban units that developed at different times and under different socio-historical circumstances. The historical core of the city is Old Belgrade, with its fortress, from which the city further expanded. Today’s New and Third Belgrade were once vast green zones of wetland ecosystems, of great ecological significance for the city’s wildlife – including migratory birds passing through the area. Today, the banks of the Sava and Danube rivers are heavily built and urbanized [

7]. The protection of remaining riparian habitats and the restoration of degraded areas are necessary steps toward creating a balance between urban development and the preservation of key migratory flyways [

8].

This research was carried out as part of a studio project (16 students per studio) in the final year of Master’s academic studies. The assignment focused on exploring the reuse potential of heritage — specifically the Old Railway Bridge in Belgrade — with three main objectives that had to be met according to three theoretical positions discussed during the studio: to be socially just, ecologically sustainable, and culturally enriching. Unlike the historical principles of Belgrade’s development, the methodology of this project aims to promote ecosystem services by integrating nature and its principles into the built structure (and vice versa), while maintaining the urban character of the environment. The hybridity of this solution required the erasure of clear boundaries between the natural and the artificial, strengthening their mutual positive impact. On one hand, the methodology was based on the study of birds and the potential of their habitats, contemplating ways in which sustainable coexistence between birds and humans can be achieved in modern cities. On the other hand, the research focused on the potentials of the (abandoned) bridge, or how that architecture could redefine the synergy between man and nature’s environments, returning transformed spaces back to birds. Can industrial heritage become a new infrastructure that fosters biodiversity and the overall well-being of the urban ecosystem? In addition to this ecological goal, the intention was to include social and cultural activities, making the space socially just and culturally enriching. Thus, ecosystem services in the project were observed through several categories:

Supporting services – Ensure the long-term sustainability of ecosystems that birds use during migration, in terms of habitat and biodiversity conservation.

Regulating services – Contribute to the stability of migratory routes and ecosystems through which birds pass, through regulation of climate and microclimate, as well as water flows.

Provisioning services – Directly provide birds with food, water, and shelter during migration. Designing a migratory bird station particularly emphasizes this aspect of ecosystem services.

Cultural services – These services are not essential for the survival of birds, but they are important for people in terms of the protection and conservation of migratory species through raising public awareness about them. In this way, cultural services indirectly protect birds by calling for their future protection.

Hence, the paper evolves through three stages. The first one introduces the topic theoretically, discussing the systemic neglect of bird migrations in urban planning, with a focus on the city of Belgrade and its position and structure in relation to this issue. The second stage provides an explanation of research on specific bird species that migrate through Belgrade, their artificial habitat, and the potential of the Old Railway Bridge. The last one proposes a design of a migratory station, discussing its key values and the results it aims to achieve.

2. Theoretical Background: Bird Migrations and Urban Environment

2.1. Human-Driven Global Threats to Migratory Birds

Urbanization – Urbanization poses two major problems for wildlife and migratory birds – habitat loss and fragmentation. Habitat loss primarily involves deforestation and the draining of wetlands that serve as resting places for migratory birds. Unregulated urbanisation often results in a highly fragmented landscape, caused by the construction of high-rise buildings and associated infrastructure, which act as barriers along migratory routes and bird habitats. Under such conditions, collisions with windows, glass surfaces and vehicles become more frequent. In addition, the remaining green spaces in cities have been altered and no longer include native plants that are naturally part of the birds’ diet [

9,

10]. Other urbanization-related factors affecting birds and wildlife on a global scale include chemical, noise and light pollution, and human proximity. Chemical pollution includes emissions from the burning of fossil fuels, as well as contamination from heavy metals, plastics or other chemicals that make foraging more difficult and dangerous. Light and noise pollution, together with chemical pollution, have been linked to phenotypic changes and general deterioration in the health and offspring viability of birds [

10,

11]. For migratory birds, light pollution - also known as ALAN (artificial lighting at night) - is particularly dangerous. Birds that migrate at night, especially during the autumn migration, can be attracted to artificial lighting and can be ‘trapped’ by the beam of light. When caught in the beam, migrating birds become disoriented, fixate on the light and fly in circles [

12,

13]. In terms of human proximity, it often provides migratory birds with an increased food supply (usually of low nutritional value compared to natural sources) and alters local temperatures (due to the urban heat island effect). Given that the main reason for bird migration is to escape harsh winters and secure essential resources for the breeding season, the new living conditions imposed by urbanisation alter migration patterns or even lead to their complete cessation [

10,

14].

Climate change – Climate change is altering temperature and precipitation patterns, causing significant shifts in the natural conditions of seasonal and permanent habitats, and leading to ecological changes across global systems [

15]. As a result, we are seeing changes in the timing of bird migrations, shifts in established migration routes between wintering and breeding grounds, and variations in the duration of their stays. There are also changes in breeding and egg-laying times (some species are leaving their breeding grounds earlier or later than usual, which can be highly problematic if resources are scarce at their final destinations), declining reproduction rates and consequent changes in overall population numbers. Due to changes in the timing of migration and the availability of food (insects or plants) at nesting sites, birds (especially long-distance migratory birds) often arrive after peak food availability has passed, just when they need it most - during the breeding season [

2,

16,

17]. Furthermore, long-distance migratory birds are usually more vulnerable than those migrating shorter distances. They rely on stopover sites for critical feeding and survival. However, climate change is making the ecosystem services provided by these sites unreliable and unpredictable, putting the birds that depend on them at risk. While climate change may advance the phenology of their breeding habitats, the migration timing od long-distance migratory birds is not adjusted to it. On top of that, it is noticeable that some species have begun to migrate shorter distances [

16,

17,

18]. Additionally, a study [

19] shows that wetland ecosystems, which include parts of Belgrade, are significantly threatened by the impact of climate change, and consequently, so are the birds that live in them. Furthermore, this study indicates that projected climate change will reduce habitat suitability for waterbirds at 57.5% of existing Critical Sites within Africa-Eurasia. Although African and Middle Eastern ecosystems are particularly vulnerable, the Balkans are also recording negative results [

19]. Many migratory birds, which connect ecosystems across the globe, are also exposed to and threatened by extreme weather conditions, such as cyclones and droughts, which are likely to worsen with climate change [

20]. Although the negative consequences of climate change on birds and global biodiversity are already evident, this negative trend is expected to continue and deepen in the future. Under such conditions, birds will have to adapt their behaviour to the changing characteristics of their environment [

21,

22].

As numerous studies [

2,

23,

24] show the extremely negative impact of human activity on birds and their migrations due to inadequate urbanization and habitat destruction – calling for urgent and habitat conservation – there is also a hypothesis that urban birds actually possess broader environmental tolerance, making them more resilient to human activity [

25]. Here, environmental tolerance is defined as “the ability to survive and reproduce in a given environment”. This study compared the elevational and latitudinal distributions of 217 urban birds found in 73 of the world’s largest cities with the distributions of 247 rural congeners in order to test this hypothesis. This study [

25] found that urban birds indeed “had significantly broader elevational and latitudinal distributions that rural congeners”, and that “behavioral, physiological and ecological flexibility may contribute to an urban bird’s ability to tolerate a broad array of environmental conditions, including disturbed habitat.” This flexibility is shown in the ability to develop new traits that allow birds to adapt their behavior to novel urban conditions — such as utilizing new resources (for food or nesting) or exhibiting resistance to the psychological effects of city life. The authors cite examples of birds that have adjusted their singing habits in response to urban noise levels or exhibit lower stress hormone levels compared to their rural conspecifics.

This trait of resilience and adaptability in urban environments is predominantly associated with bird groups that inhabit broad and diverse regions of the world and various climates, which is particularly interesting in the context of bird migration, as migratory birds pass through different landscapes on their journey. Additionally, it could apply to birds that have ceased their winter migrations and now permanently reside in cities, having adapted to human proximity. Nevertheless, a key aspect of this study highlights that only a portion of birds possess broad environmental tolerance, leaving the rest – the majority – highly vulnerable due to unregulated urbanization and the harmful impact of human activity. The goal is to create a resting area, habitat, and feeding ground for all bird species, regardless of their innate or learned adaptability, their relationship with humans and built environments, or their general habits in life and diet.

2.2. Belgrade as an “Important Bird Area“ (IBA)

BirdLife International, the world’s largest organization for bird conservation, is the founder of the pan-European international project called

“Important Bird Areas” (IBAs), with a goal of identifying and evaluating areas of importance for birds, registering them in international records, and taking active measures for their protection and improvement. Three core areas of bird conservation include: direct protection of individual birds and pairs, protection of significant bird habitats, and identification and protection of key bird areas. As a method to achieve these goals, an important part of the work of this organization and its partners is focused on developing a network of local collaborators and encouraging their motivation to monitor birds in IBAs, as well as raising public awareness about the importance of birds and their habitats [

26]. This project aims to contribute to that effort.

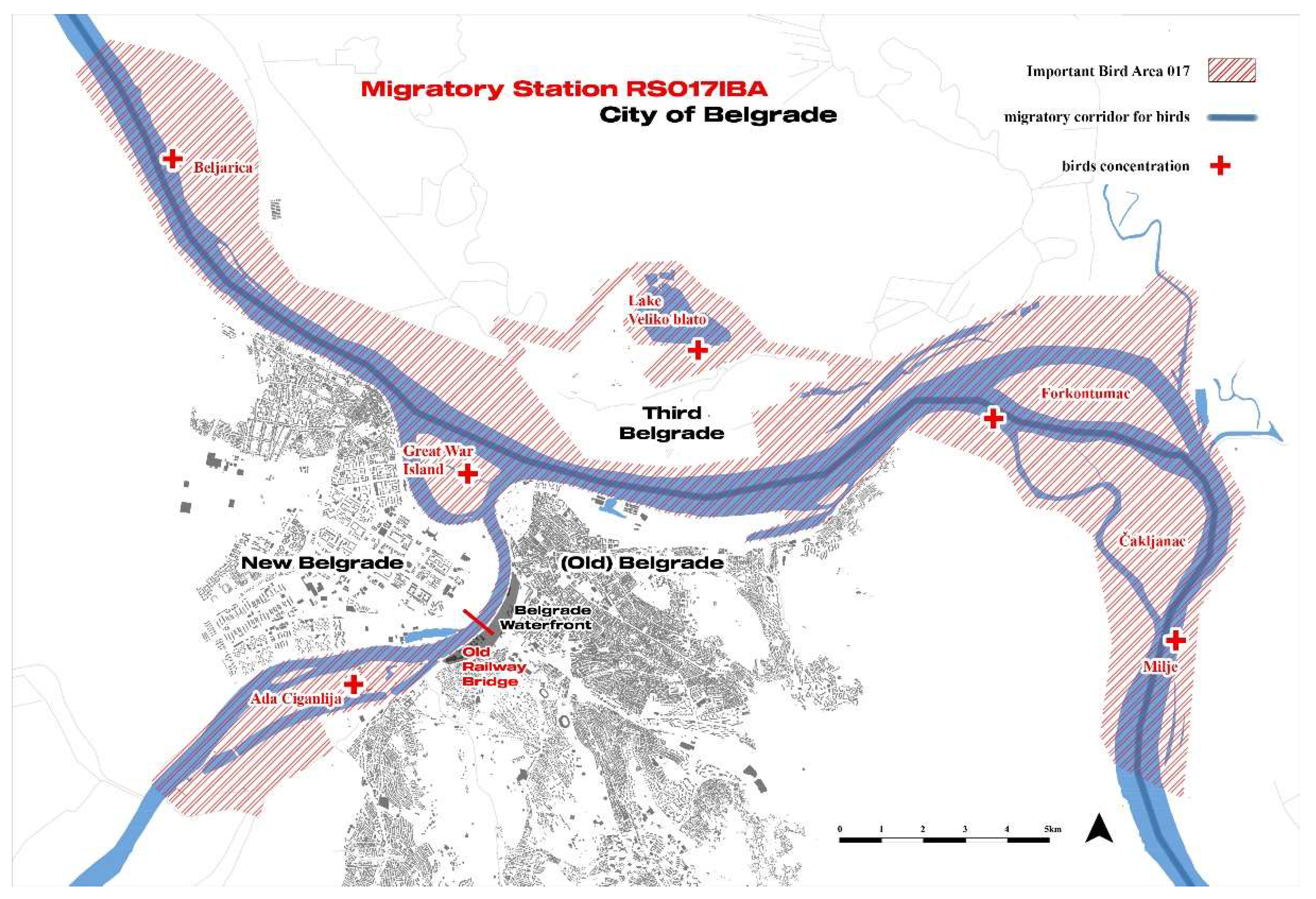

In the Republic of Serbia, there are a total of 79 areas classified as important for birds – IBAs and KBAs (“Key Biodiversity Areas”), of which 72 are identified for migratory bird species. Out of 311 total bird species in Serbia, 258 are migratory birds. Two main threats to important bird sites (IBAs/KBAs) are defined as

Biological resource use and

Natural system modifications [

27]. Belgrade’s river coastline, specifically the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and its surroundings, has been recognized as an Important Bird Area, with the international designation RS017IBA (

Figure 1). With an area of 9,808 ha, it falls into categories B1i (areas that regularly support 1% or more of the migratory or isolated populations of wetland bird species) and B2 (areas where species with an unfavorable conservation status in Europe are found, with the majority of the population outside of Europe). The IBA covers a total of 49 kilometers of river course, consisting of 10 kilometers of the Sava and 39 kilometers of the Danube River. A significant feature of this Important Bird Area is its highly urban character [

8] (pp. 88–91).

2.3. Geographical Position of Belgrade

The City of Belgrade, Serbia, is located at a very favorable geographic point on one of Europe’s vital migratory routes. Its specific location at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers, between the Pannonian Plain to the north and the hilly Balkan Peninsula to the south, makes it a significant point along the migratory path for birds crossing the continent during seasonal migrations [

28]. This area is naturally characterized by its terrain, hydrological, and climatic features, which together create optimal conditions for rest, feeding, and navigation for birds during their long journeys.

With that in mind, Belgrade is part of the so-called Black Sea–Mediterranean Flyway that runs from northern Europe, through the central Balkans, to the Middle East and Africa. A deeply concerning fact was shown by a 2003 study, which found that population trends for wetland birds taking this route had decreased by as much as 65% in the past decade, with three times as many species in decline compared to those whose numbers were increasing [

29]. In addition to the Black Sea–Mediterranean Flyway, Serbia (and Belgrade) also lies within the Adriatic Flyway, connecting birds from Central, Northern and Eastern Europe to North Africa via the Adriatic Sea [

30].

The relevance of Belgrade in this migratory network is the result of several geographical factors:

The Danube and Sava Rivers – These two major rivers serve as natural navigation landmarks and food sources for birds. Belgrade’s unique river ecosystem, with Sava flowing into Danube, is characterized by wetlands and various coastal habitats, crucial for migratory birds. Since most of the area is exposed to regular flooding, there is a significant diversity of habitats - vast water surfaces, sandy and muddy banks and coastal shoals, flooded forests and meadows, as well as backwaters – provide abundant food, safe refuges, and vast areas for resting of migratory birds. However, the banks of the Sava and the right bank of the Danube are largely build up and urbanized [

8] (pp. 88–91).

The Pannonian Plain – The Pannonian Plain, extending through much of Central Europe, was once a vast complex of wetlands, marshes, shallow lakes, and floodplains. These ecosystems used to be one of the most important habitats for migratory birds in this part of Europe, as they combined several key factors: (1) abundant food (the ecosystems yielded insects, fish and amphibians, as well as a variety of plants), (2) shelter and safe stopover habitats, (3) natural navigation markers (rivers) and (4) favorable microclimates. Most of the old wetlands have since been drained and irreversibly transformed for urbanization and agriculture. The Serbian part of the Pannonian Plain - the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina – contains the highest concentration of Important Bird Areas in the country (21) [

8] (pp. 24–84).

The Mixing of Climatic Zones – The proximity of temperate, continental, and sub-Mediterranean climates creates various ecological niches that favor a diversity of species. Belgrade lies at the intersection of several climatic zones, including temperate-continental climate with Mediterranean influences. However, due to inadequate urban development of Belgrade, the heat island effect is quite noticeable, making this city the hottest one in the country [

31].

2.4. Urban Structure of Belgrade

Research on Belgrade regarding this topic has been conducted through a comparative analysis of research and planning documentation, with a focus on guidelines for the conservation and protection of “Important Bird Areas“ in Serbia, and globally [

8].

Before the construction of

New Belgrade, the area between the Sava and Danube rivers was covered by extensive wetland ecosystems, which were valuable for birds. However, intensive urbanization in the mid-20th century led to the complete draining of this ecosystem, with little regard for its wildlife. The construction of New Belgrade was carried out in accordance with modernist urban planning principles, focused on functionality and infrastructure development, while natural habitats were systematically altered – greenery was seen through a modernist idea of Garden City, creating green zones of park-garden space near the river. However, while greenery did have an important place in the design of New Belgrade, it was seen as a ‘common good’ for people, not wildlife (including migratory birds) [

7,

8,

32,

33].

In the context of the urban ecosystem of Belgrade, it is necessary to emphasize

Veliko Ratno Ostrvo (Great War Island) as a significant bird (and other wildlife) protection zone. Despite its proximity to the city center, the island remains uninhabited and rich in dense willow and poplar forests. Unlike most of the Belgrade coastline, this place has retained its original wetland ecosystem, and has had the status of a protected natural asset since 2005. The diversity of plant species allows for a rich avifauna – with over 160 species having been recorded. The number and structure of these birds depend on the water level and the season of the year. A significant portion of them are migratory (such as

Ciconia ciconia, Egretta garzeta, Circus aeruginosus), which mostly inhabit this area as their summer habitat. Many registered birds are under the protection of international conventions on bird conservation [

32,

34,

35].

The area of

Third Belgrade, which includes informally developed parts on the left Danube bank, is currently developing without clear urban regulation, and with environmental aspect of it almost completely ignored. This area is located very close to the wetlands and floodplains, which hold crucial importance for migratory birds. Uncontrolled urban sprawl led to habitat destruction and ecosystem fragmentation, and poses a direct threat to migratory bird species, which have been using the area as a resting and feeding ground. Wetland drainage, poor waste management and the removal of vegetation have further diminished this region’s ability to support biodiversity. While some areas of Third Belgrade have been designated as ecologically significant (lake

Veliko Blato), they suffer from degradation and destruction of ecosystem services due to the absence of institutional protection and proper ecological infrastructure [

8,

36].

The

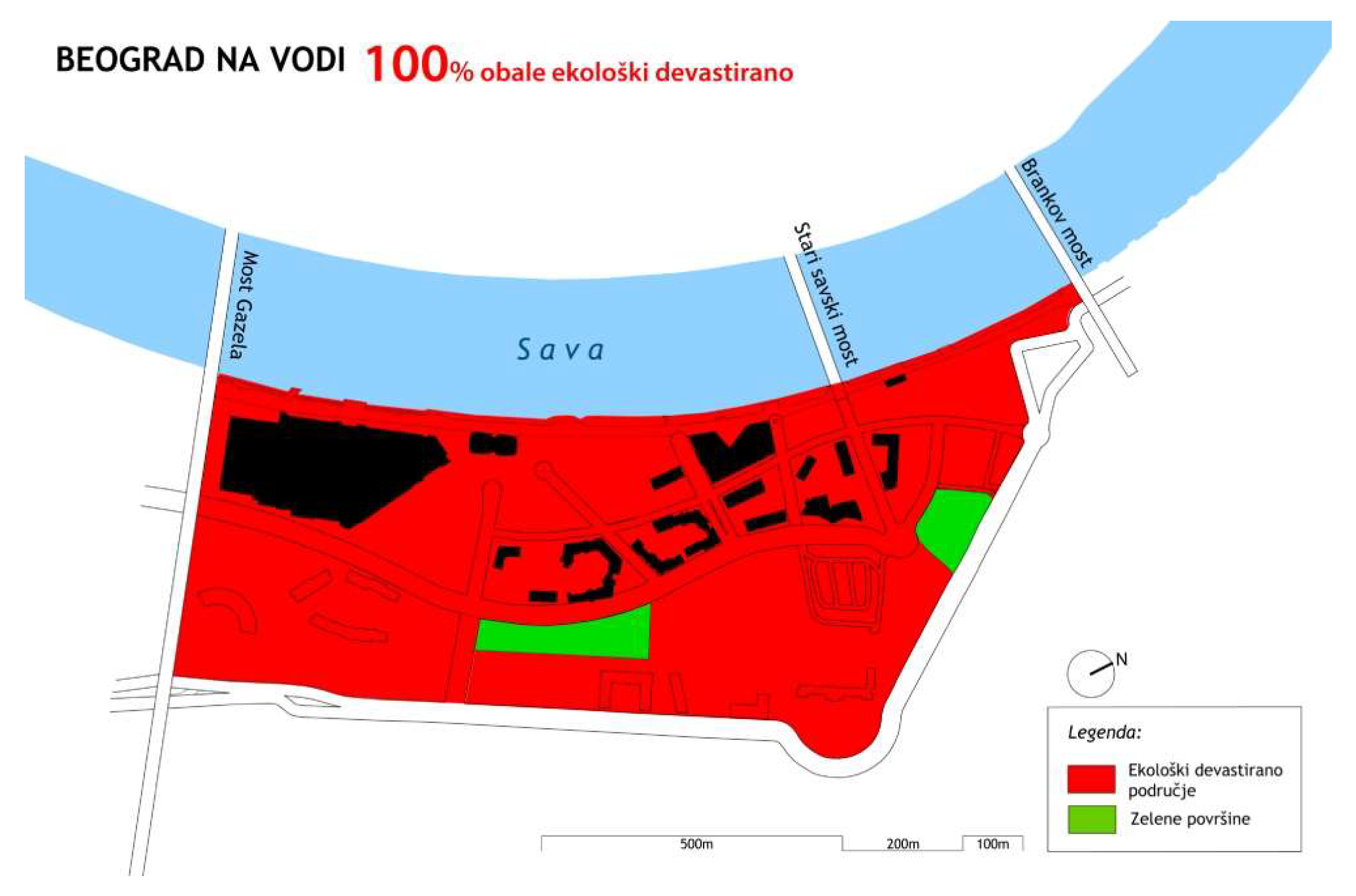

“Belgrade Waterfront” (

Beograd na Vodi) project is a prime example of urban transformation in Serbia that has been the subject of considerable controversy. The ecological dimensions of the project were largely disregarded in favour of commercial and infrastructure development. The construction of this complex along the Sava River has had a profound impact on the natural character of the riverbank through cementing and significant reduction in vegetation (

Figure 2). The reflective facades of skyscrapers and the artificially lit urban landscape have been shown to disturb migratory birds, thereby disrupting their orientation mechanisms (which are particularly important along river valleys) and increasing the risk of fatal collisions. In the absence of adequate regulations and strategic planning that would integrate principles of green infrastructure, the Belgrade Waterfront becomes an example of modern unsustainable development, where natural resources are subordinated to economic interests [

7,

9,

37].

3. Materials and Methods

The first phase involved identifying which species of migratory birds live in or pass through Belgrade, classifying them based on key characteristics, and designing their new habitat. This was done using literature documenting birds from Important Bird Areas in Serbia [

8], bird atlases of Serbia and Europe (which provide detailed insights into their traits) [

38,

39], as well as manuals for creating habitats for different bird species [

40]. Following this, materials suitable for the intervention were explored. Finally, the Old Railway Bridge in Belgrade – the project’s framework – was analyzed, with a focus on unlocking its potential as industrial heritage and integrating it into the city’s new green infrastructure.

3.1. Grouping Bird Species and Their Habitat Characteristics

The diversity of migratory birds is vast – they differ drastically in shape and size, characteristics of temporary and permanent habitats, feeding habits, as well as their migration patterns and durations. Research shows that around 74% of the species of European fauna can be found in the Republic of Serbia [

8] (p. 14), particularly visible during spring and autumn when they migrate through the country. These various species had to be roughly grouped into categories in order to provide them with an adequate habitat under new conditions.

The criteria for this categorization primarily referred to:

Migration status – Due to climate change and increased availability of artificial food sources from human proximity, a significant number of species have interrupted their winter migration and remain in the same area throughout the year. Therefore, it was necessary to determine whether the designed habitat should be a “resting place / station” or a permanent residence.

Habitat and its dimensions – Creating an optimal space that is large enough but not oversized for the bird (which would make the new habitat feel unnatural).

Nesting characteristics – Does the bird prefer enclosed or open spaces for its nest, and what shape does it require?

Optimal environment – Does the bird prefer life close to water, near water but at a sufficient distance, or in elevated, isolated places?

Population density – Does the bird prefer living in flocks or alone? Does it require a complex social system, or is isolation better instead? How large is the bird’s “family”?

Feeding habits – Does the bird look for food near its nest or travel farther? How often does it feed its young? Does it need places to observe its prey?

Relationship with humans – Does the bird fear human proximity, or does it freely use human resources?

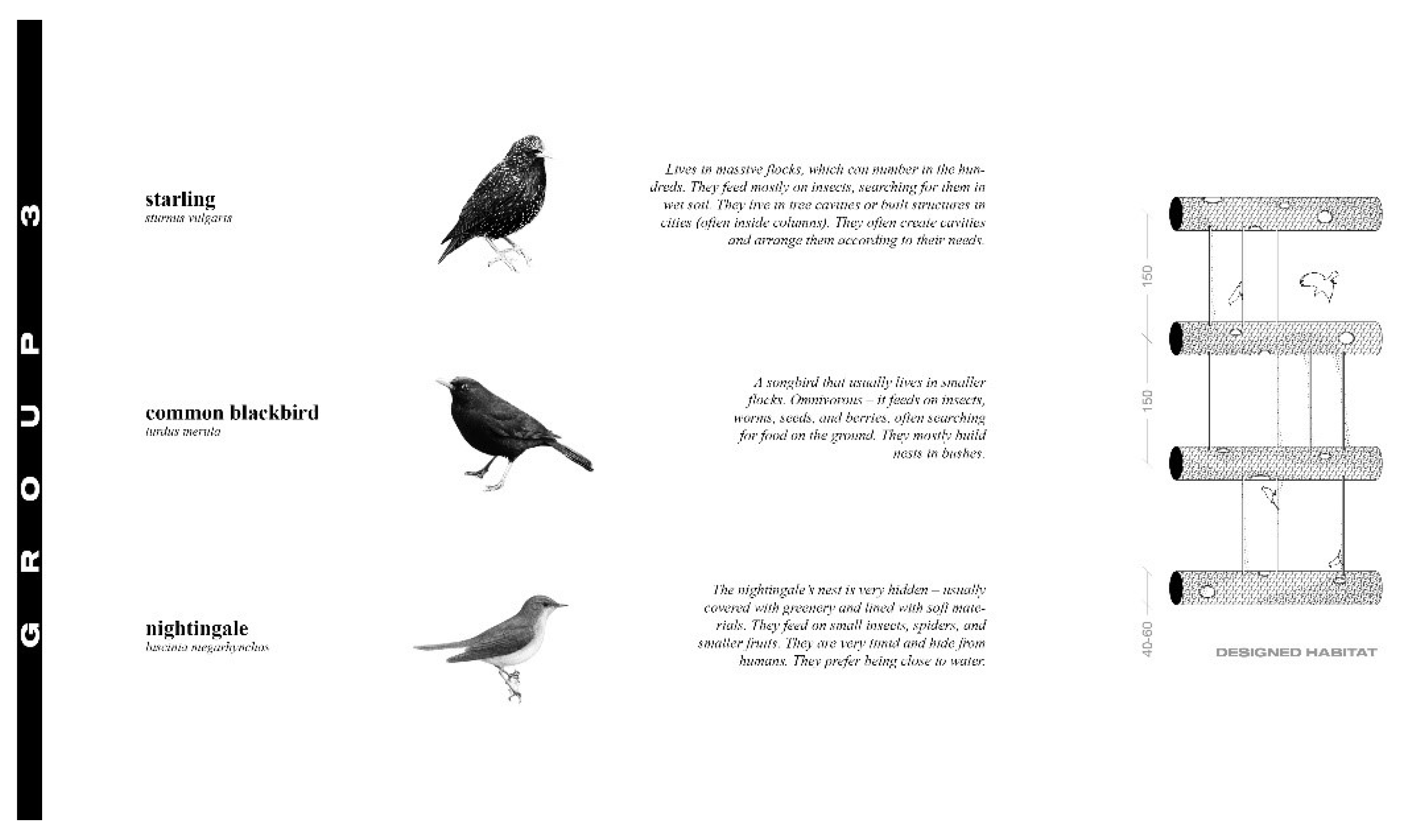

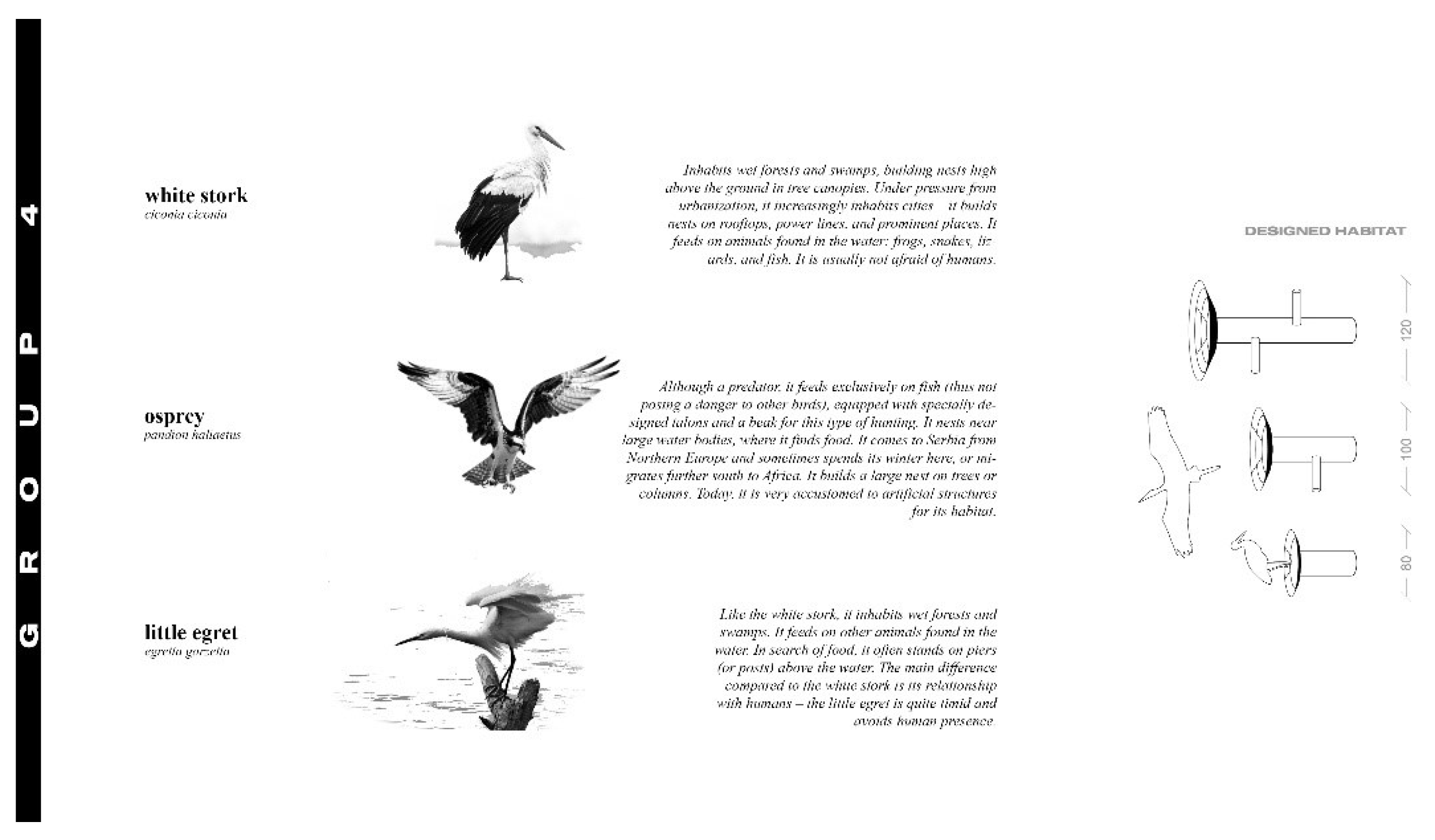

Based on these factors,

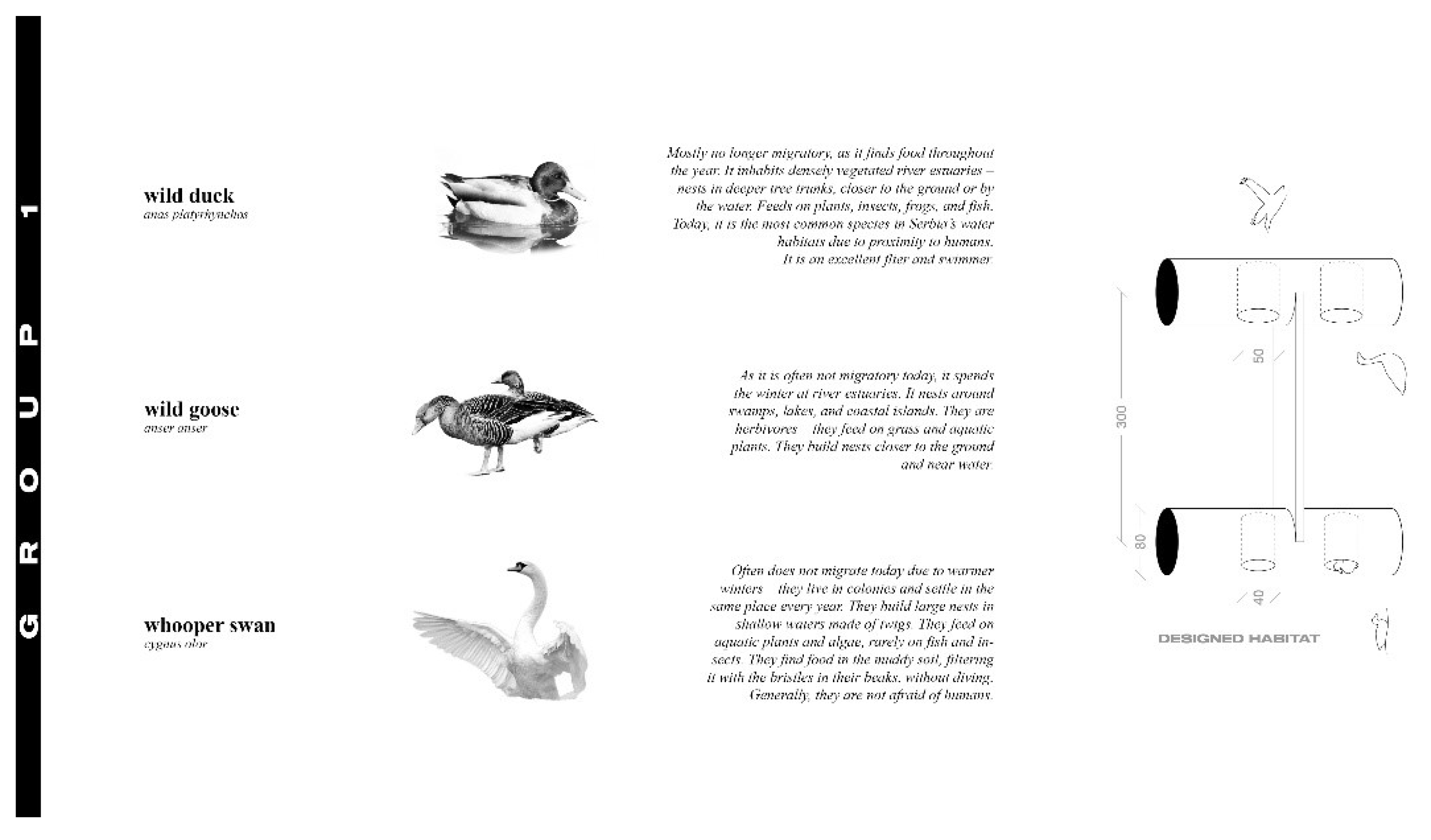

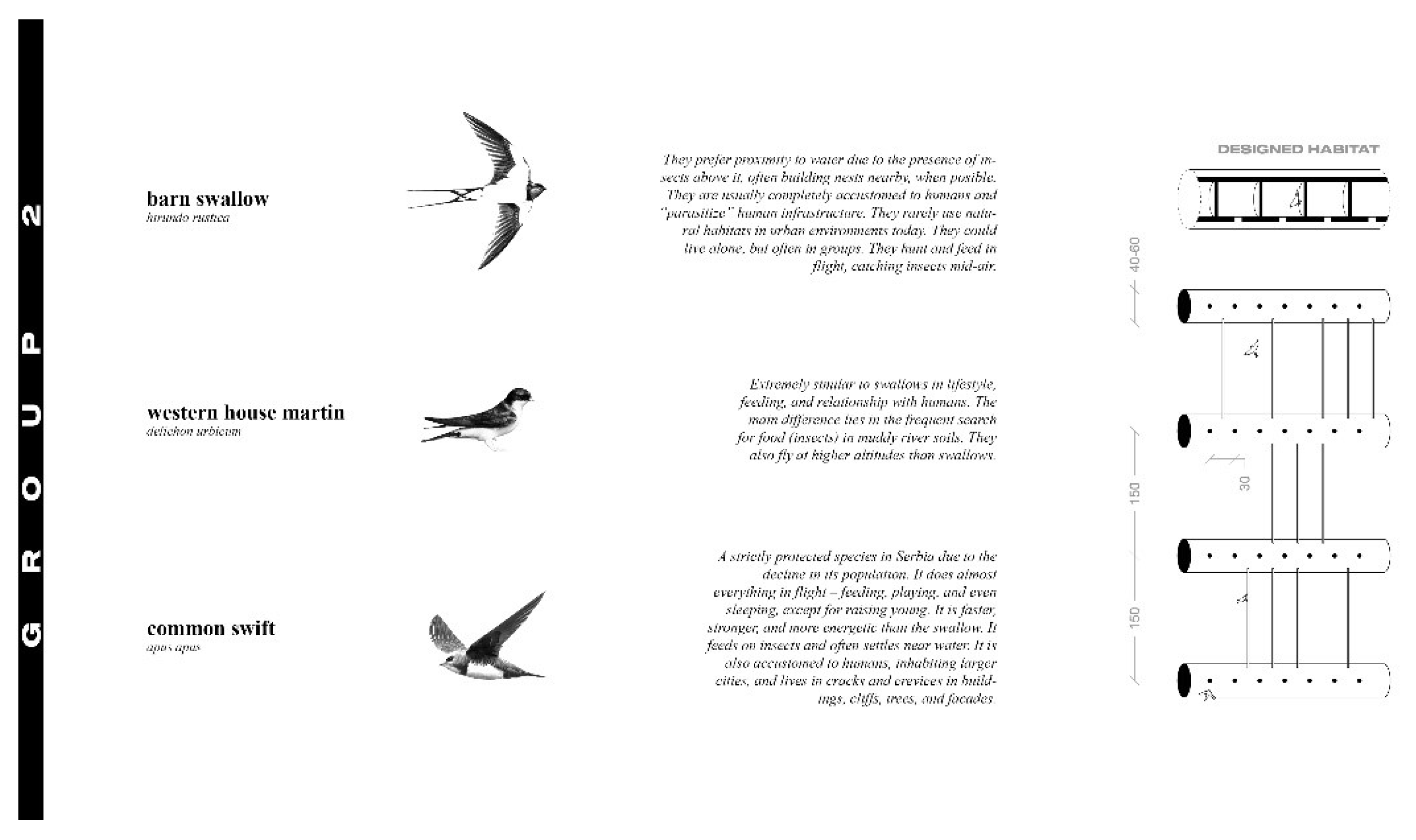

four main groups of birds with significant similarities in life and habitat characteristics, migrating through the Belgrade area, were defined. It is important to note that differences within the groups certainly exist (which also affect the design of the habitat), but these primarily relate to the flexible dimensioning of different elements. For each group, three typical and most numerous representatives are shown, whose life and migration habits will be detailed. The grouping (1-4) is loosely based on their vertical disposition (1 – life on or near water, 4 – solitary life high above the ground). The textual description of the natural habitat will be accompanied by an axonometric drawing of the new, optimally designed habitat. At present, the largest share is made up of birds of the first and second groups (around 60-70%) [

8]. However, given the unpredictability of global warming and the tendency of birds to adapt to changing urban environments, it is crucial that the structure designed for them reflects both their population size and composition.

GROUP 1 – Larger water birds, which often do not migrate today due to the availability of food even in the winter period (

Figure 3).

GROUP 2 – Small birds, exceptionally skilled fliers, that catch insects in flight and often build their nests near human settlements and water surfaces (

Figure 4).

GROUP 3 – Timid songbirds that prefer hidden nests which they can arrange themselves (

Figure 5).

GROUP 4 – Large carnivorous birds, accustomed to living in human structures, seeking habitats high above the ground (

Figure 6).

3.2. Material Selection

When choosing materials for the construction of the habitat, three key factors had to be considered:

Performance of the material – The chosen materials must be resistant to external impacts and the harsh climatic conditions of the river and the bridge.

Color – Birds react strongly to color. It was necessary to select an appropriate color that would not scare the birds, and the one that would attract them instead.

Aesthetics – The bridge occupies a central place in Belgrade’s cityscape, so it was important to ensure an appropriate visual appearance for people.

On basis of these criteria,

COR-TEN steel and

dried brick (with a steel substructure) are selected as main materials. COR-TEN steel combines the strength and durability of steel with a unique aesthetic of its patinated surface. It also blends well with the structure of the Old Railway Bridge [

41]. The specific red hue of these materials is attractive to birds and ensures resistance to harsh environmental conditions, retaining its natural shade. Dried brick was used to simulate the habitat for birds that prefer to create their hidden habitats independently, allowing them to create openings in the structure themselves (primarily from Group 3).

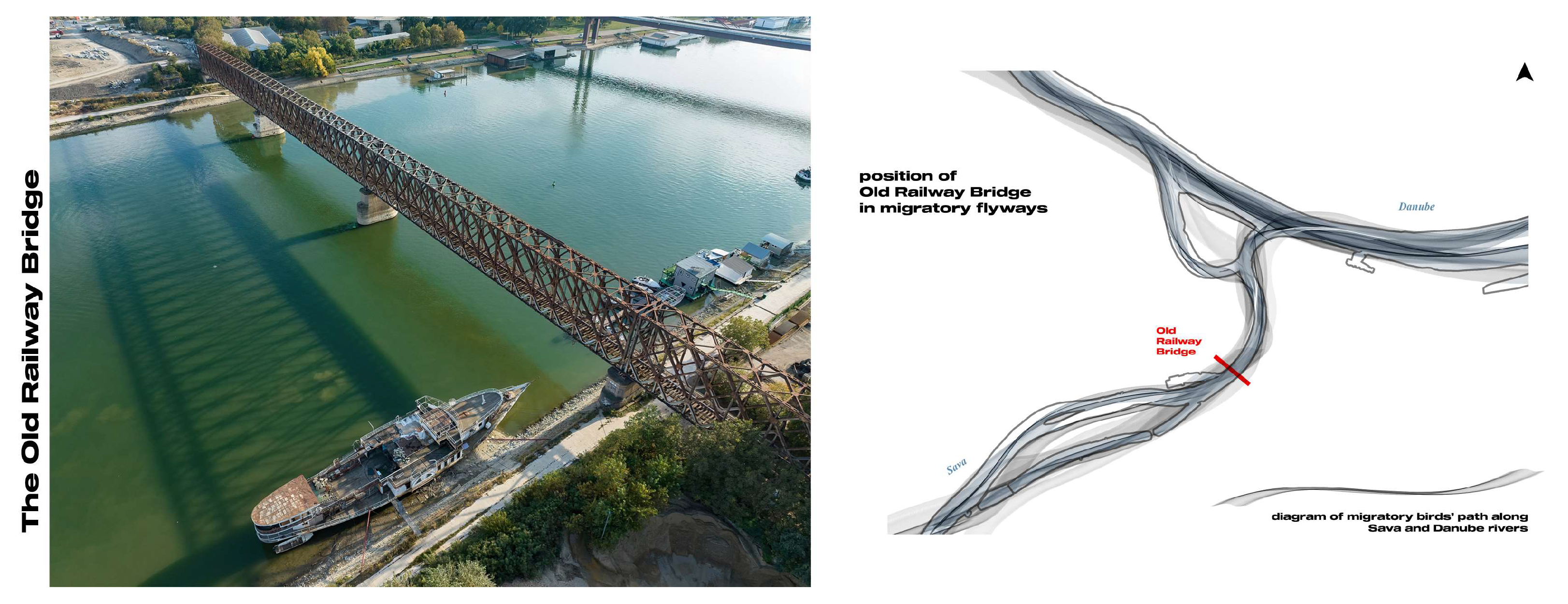

3.3. The Old Railway Bridge

The project framework involves the Old Railway Bridge over the Sava River in Belgrade, and the main theme is rethinking its function. This bridge connects New Belgrade with Vojvoda Mišić Boulevard and the present-day neighborhood Belgrade Waterfront.

When it was opened in 1884, it was the first modern and only railway bridge in Serbia, stretching around 462 meters. The current version of the Old Railway Bridge was built after the Second World War as part of war reparations [

42]. It has not been in operation since 2018, and its reconstruction has been announced – as part of the Belgrade Waterfront project, it is planned to transform this bridge into a combined pedestrian and bicycle bridge with cafes and viewpoints, without a specific function (

Figure 7).

The bridge spans approximately 389 meters in length and is 12 meters high. Its width is 6.9 meters, and it is divided into four approximately equal parts, each measuring 95 meters. The bridge features five stone piers, two of which are in the water. Its construction is a lattice structure, made of steel. The width of the navigation opening is 90 meters, and the height of the navigation opening is 6.9 meters at low water level, and 12.7 meters at zero water level. The width of the Sava riverbed under the bridge is around 260 meters [

43].

The approaches to the bridge are extremely neglected and inaccessible on both sides, reducing human presence. On the New Belgrade side, the bridge is about 100 meters long on land, where its structure has naturally overgrown with surrounding greenery. However, the broader surroundings of the bridge are made up of shipyards and gravel pits (on the New Belgrade side), and a large construction site on the Belgrade Waterfront side, with its devastating effects on the riverbanks and local wildlife. As people took over the riverbanks, the initial idea was to give back the bridge to the original inhabitants of the river.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Project Description

Seeing a bridge as an artificial node connecting land, air, and water — the three primary habitats of birds – the concept proposes the creation of a migratory station for birds in the very center of Belgrade, through an intervention on the Old Railway Bridge. In addition to providing habitat and food for birds, the programmatic concept includes spaces dedicated to ornithologists for bird monitoring, tagging, and research, as well as for visitors, who will be introduced to the world of birds through interactive content.

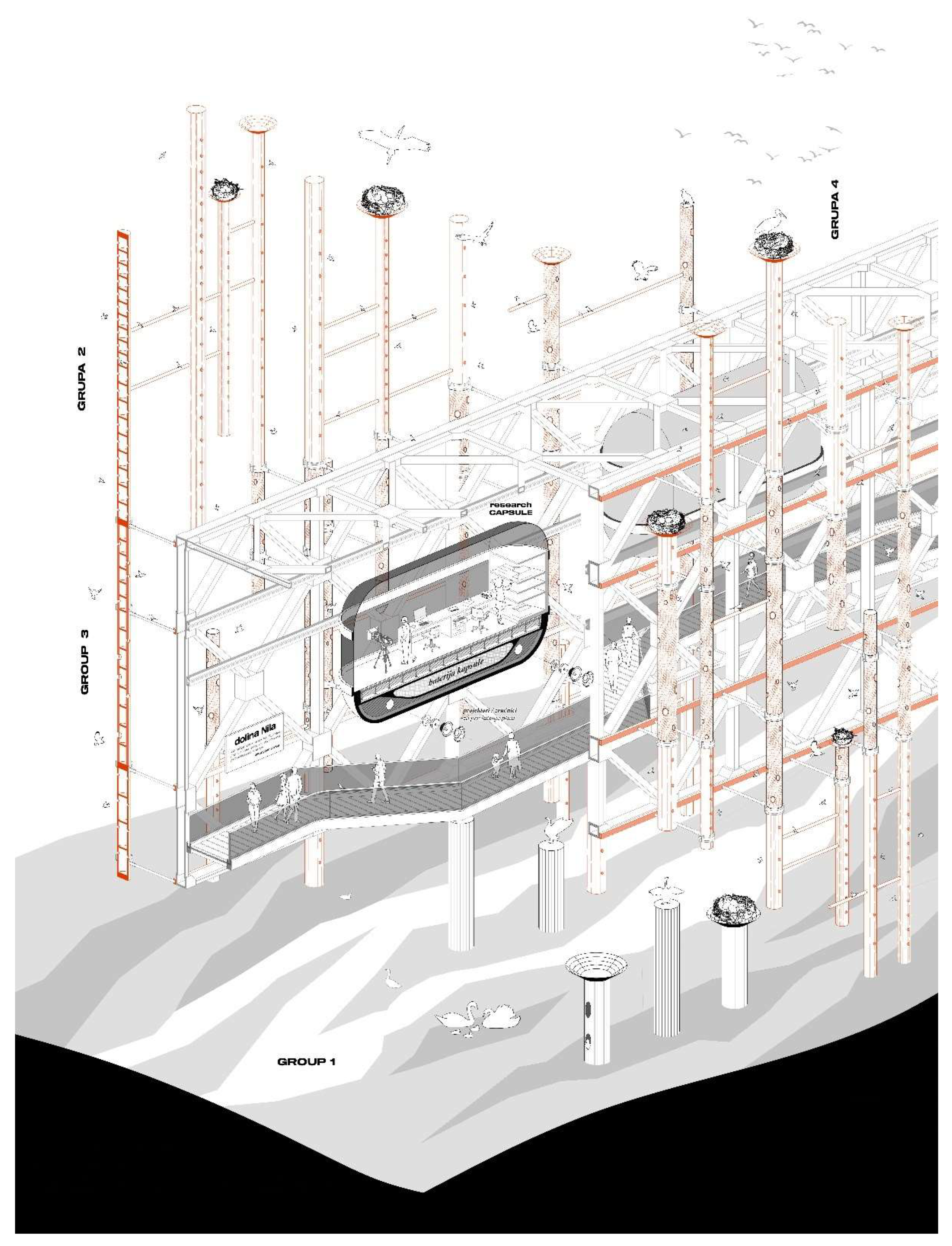

Therefore, the intervention on the bridge consists of three fundamental systems of elements, whose appearance and function will be explained in detail below (

Figure 8). During the bridge’s design, it was essential to avoid the use of wires and ordinary (transparent) glass to prevent harmful and often fatal bird collisions. Similarly, strong, invasive lighting and sound effects were avoided to ensure that the birds’ natural biorhythms and activities remained undisturbed.

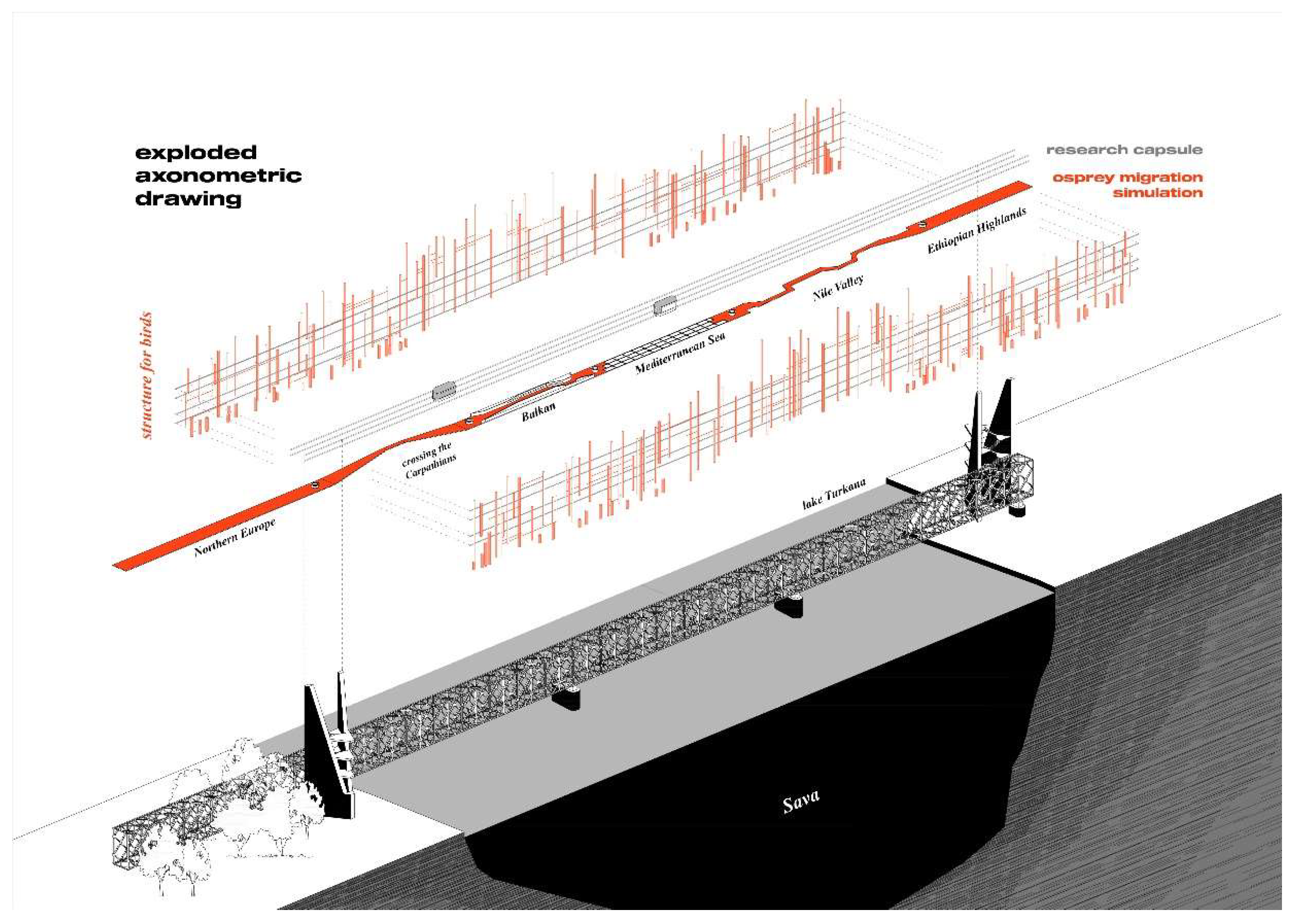

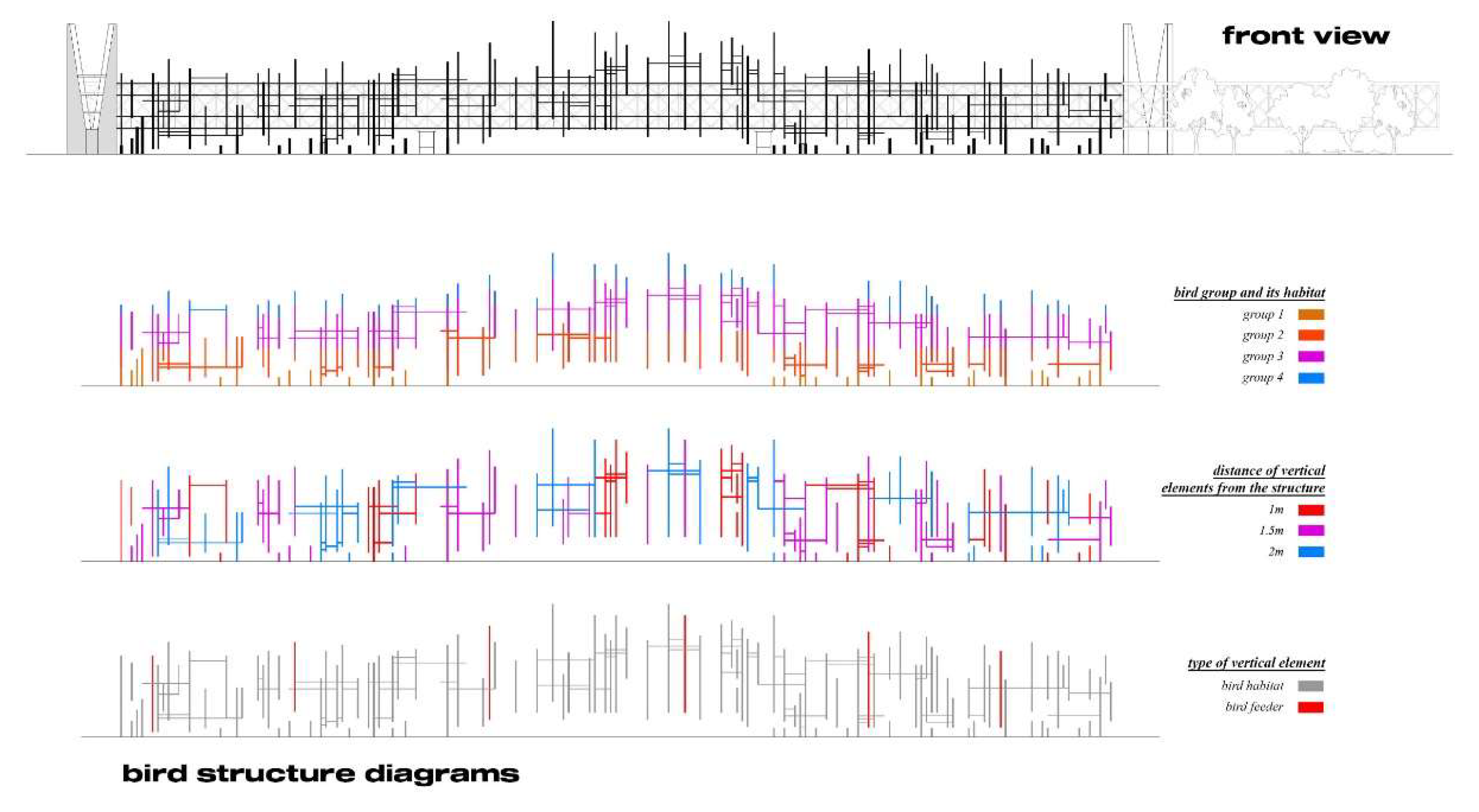

4.1.1. Structure for Birds

Considering birds’ natural tendency to “squat” human architecture, the structure intended for them adopts a parasitic character, enveloping the outer side of the bridge. It consists of a system of vertical elements that differ in dimensions, materials, and functions (

Figure 9). The structure had to be carefully considered on both macro and micro levels.

From a macro-design perspective, the structure is intentionally irregular—it follows the transition of bird environments (air-water) from the central part of the bridge toward its ends. In the middle of the bridge, it rises in height for birds that prefer living high above the ground, while toward the riverbanks, it descends closer to the water, for waterbirds accustomed to wetland environments. The individual vertical elements are placed at three different distances from the bridge structure – 1m, 1.5m, or 2m – in order to allow unobstructed flight in both horizontal and vertical planes. Additionally, an adjustable substructure allows the change in layout and distance of vertical elements when necessary. Such flexibility is important, as the structure needs to change throughout the year in response to seasonal migration cycles, as well as shifts in number and types of species of birds occupying different areas.

Aside from functioning as a migratory bird habitat, the structure also incorporates six vertical elements on either side of the bridge, evenly distributed along the structure’s length, for supplementary feeding during the winter food scarcity.

Regarding the micro-design of the structure, its dimensions and materiality are specifically adapted to the migratory bird species that inhabit or pass through Belgrade. This was determined based on research conducted on four primary bird groups, considering appropriate habitat conditions, dimensions, and migratory needs. Diagram 1 illustrates the spatial distribution of different micro-habitat designs (Groups 1–4) within the macro-design of the structure—ranging from wetland and water birds at the base of the structure, to large flocks hunting insects over the river, to timid songbirds and large raptors seeking isolated habitats high above the water and ground.Finally, the vertical elements are interconnected by horizontal components, which serve as essential perches and observation points, particularly for birds hunting over the river.

In contrast to the parasitic structure designed for birds, the interior of the bridge is intended for human use. Circulation paths are stratified on the basis of user type (professional vs. hobbyist/visitor). The interior has a pure minimalistic character that does not compete with the complex and “parasitic“ bird structure. It is designed to bring people closer to birds, enabling observation without disturbing birds’ natural behaviors and feeding patterns.

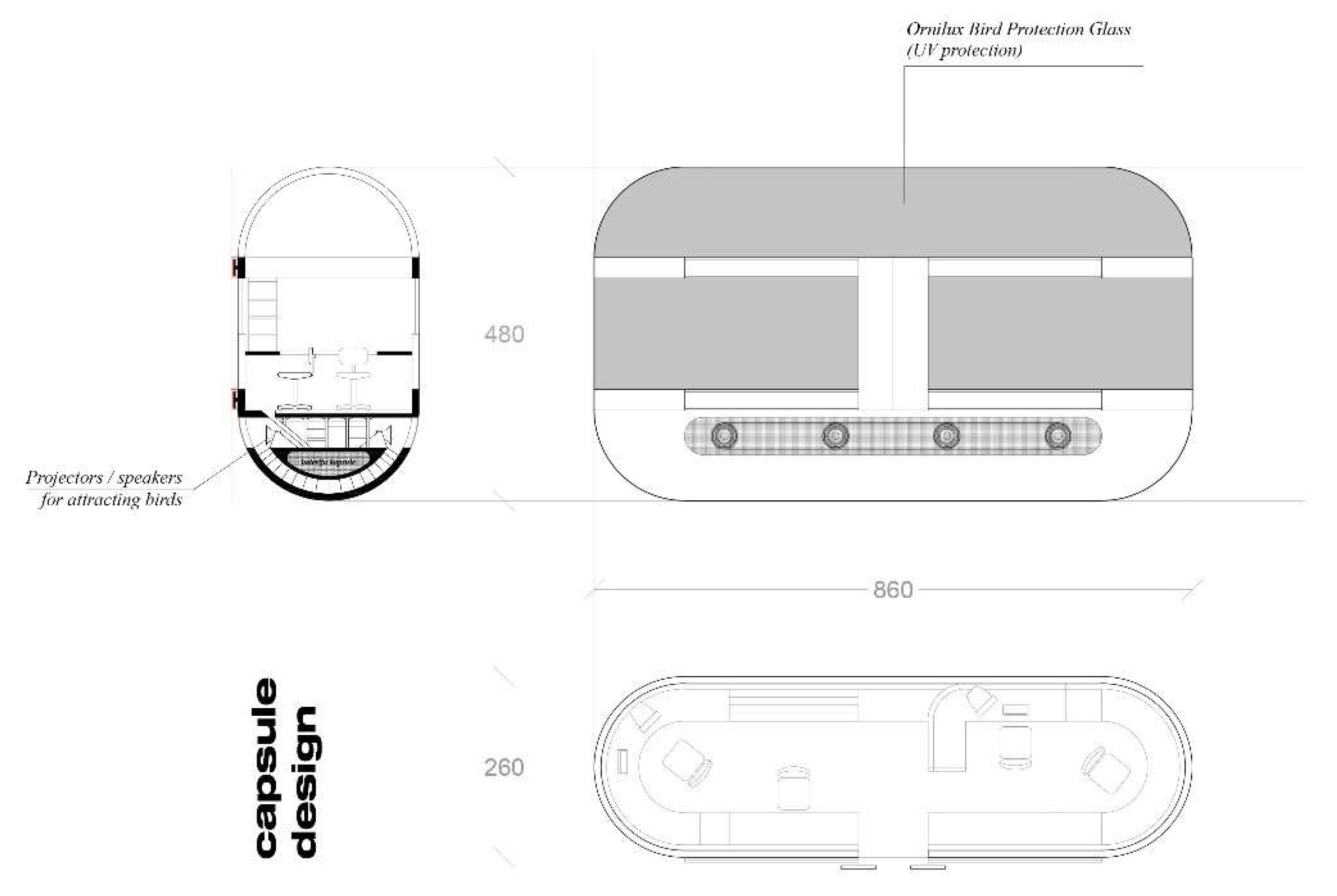

4.1.2. Higher Section: Ornithological Research Capsule

In the upper section, two specially designed capsules accommodate ornithologists (

Figure 10). The capsule’s shape is a rectangular filleted container (to ensure the necessary aerodynamics), measuring 860 cm in length, 260 cm in width, and 480 cm in total height. The capsules move along magnetic rails integrated into the inner side of the bridge, positioned at a height of six meters, ensuring they do not obstruct visitors walking along the lower part of the bridge while allowing ornithologists to work undisturbed. These capsules are made to store all necessary materials for the ornithologists’ work:

Ringing and marking birds: This involves marking birds with metal or plastic rings with unique codes, in order to track their migrations, lifespan, and other biological aspects. For example, a European roller ringed in 2019 near Bačka Topola was found the following year in Namibia, having flown over 7,300 kilometers.

Bird inventory and tracking: Closely related to bird ringing, this process is crucial for international collaboration, offering insight into fascinating migratory routes, unaffected by artificial state borders.

Publications and scientific research: The publication of monographs and atlases provides detailed information on migratory routes and bird behavior, contributing to a better understanding and protection of these species [

38].

Since the capsule needs to be glazed to allow observation of birds from within, while avoiding bird collisions with conventional glass, Ornilux Bird Protection Glass has been used. This glass has a UV reflective coating that is visible to birds but invisible to the human eye. Additionally, birds cannot see the people inside the capsule, while people can observe them. Lastly, to attract birds, the capsule is equipped with integrated projectors and speakers that emit special audiovisual effects. These effects must be subtle and carefully designed, such as specific bird calls or sounds associated with food.

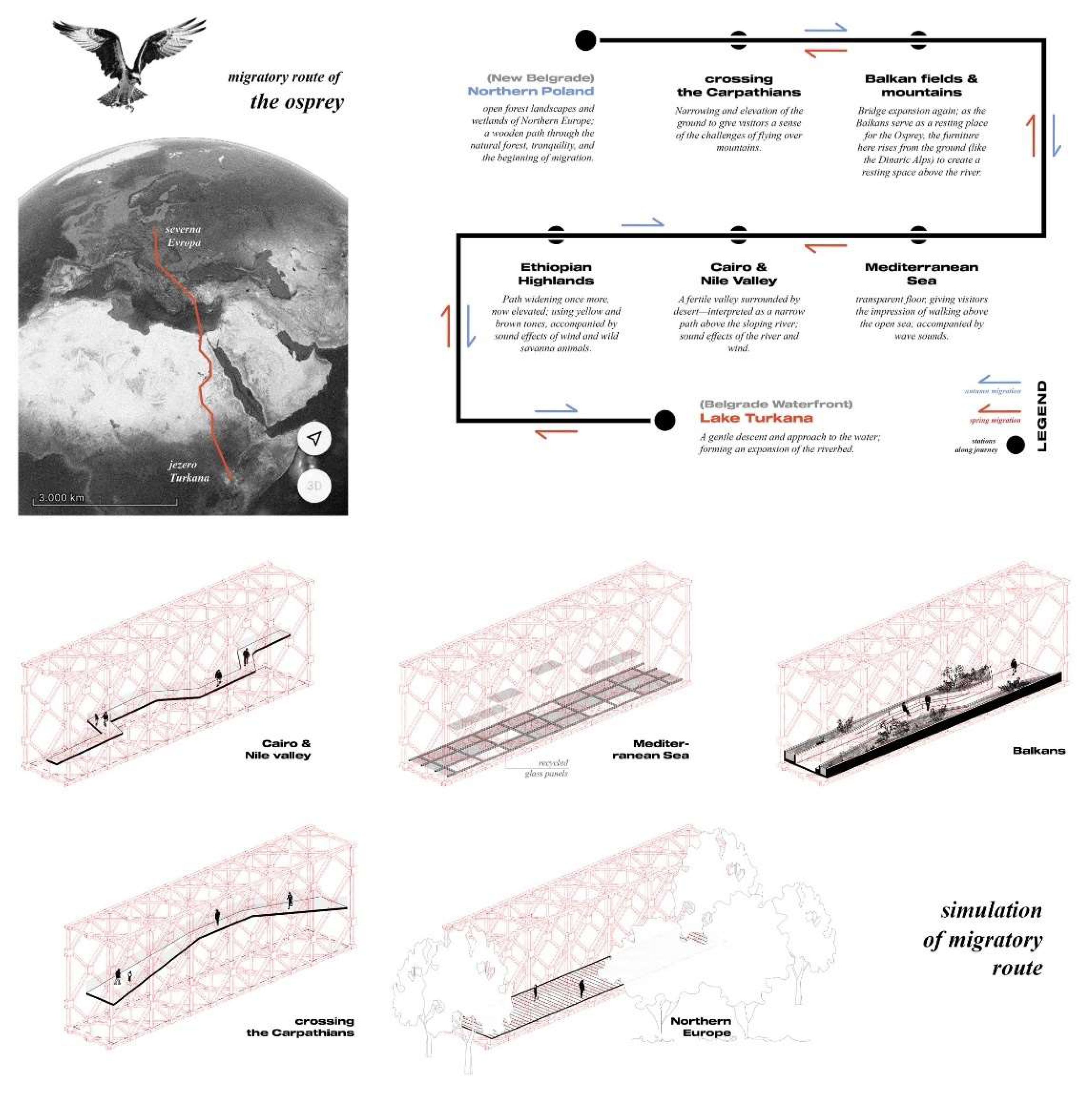

4.1.3. Lower Section: Visitor Experience and Interactive Migration Simulation

The lower part of the bridge is dedicated to visitors and bird watchers. It is designed as an interactive path that brings the world of birds closer to visitors by simulating the migratory journey of the osprey through diverse landscapes. The osprey has one of the longest migratory routes in this part of the world, starting from Northern Europe and ending at Lake Turkana in southern Africa [

44]. Along its path, this species traverses very different landscapes, climatic conditions, and both natural and man-caused obstacles each year—challenges that should be presented and made tangible to visitors (

Figure 11). Moving from New Belgrade (geographically Central Europe) toward Old Belgrade (geographically the Balkan Peninsula), visitors follow the same course as migrating birds. Depending on the direction, this could represent spring or autumn migration. The goal is to raise awareness and general knowledge about bird migration through a sensory experience and symbolism, complemented by informational panels.

Below is a description of these zones and the way they are simulated along the bridge’s path:

First Northern and Central Europe – Its open forests and wetlands are the osprey’s summer habitat, where its long migration begins. On the bridge, this is represented by a wooden walkway surrounded by natural greenery, evoking the peaceful start of the journey.

Crossing the Carpathians – The osprey’s first major challenge is flying over this mountain range. On the bridge, the visitor path narrows and rises into a steep incline, while strong river winds create additional difficulty in this movement.

Balkan Fields and Mountains – The Balkans, including the Pannonian Plain and Dinaric Alps, provide a natural resting point for the osprey, with plenty of food and shelter (which is now drastically reduced due to human impact). On the bridge, the path widens again, featuring benches with integrated greenery, creating a resting area on the river with an open view of the surrounding landscape.

Mediterranean Sea – Large bodies of water pose a great challenge for migratory birds, as they often lack resting points. On the bridge, this zone is represented by a glass floor made of recycled ocean-waste glass, giving visitors the impression of walking over open water, followed by the sound of waves.

Cairo & Nile Valley – Although a refuge after crossing the Mediterranean, this fertile river valley, surrounded by a deadly desert, presents a struggle for resources and survival. On the bridge, the path narrows and becomes winding, with sound effects of water and wind.

Ethiopian Highlands – Another elevation to overcome. The bridge’s path expands again, now elevated, using yellow and brown tones, with wind and savannah wildlife sound effects.

Lake Turkana – The osprey’s final destination and winter habitat. Symbolically, this marks the end of the bridge and the migratory route. Visitors gradually descend to the river, where a widened riverbank allows them to feed migratory waterbirds.

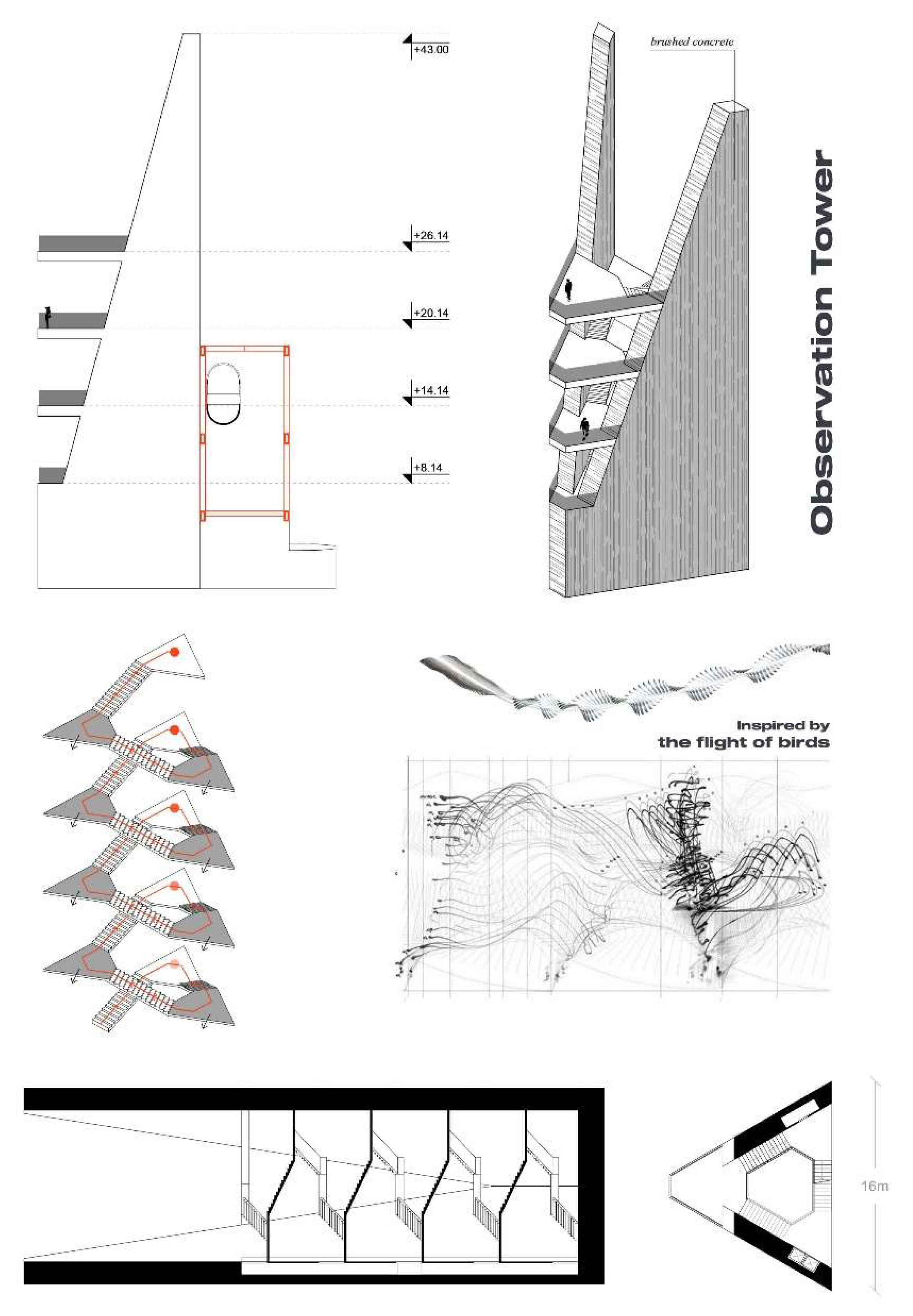

4.1.4. Observation Towers and Vertical Communication

The intervention on the bridge also includes the construction of two observation towers, serving as the main vertical communication nodes between different “layers” of the project. These are positioned next to the bridge’s pylons on the riverbanks of Old and New Belgrade. In addition to vertical circulation, the towers play a crucial role in bird observation, both for amateurs and professionals. Their significant height of 43 meters provides optimal viewpoints. The tower’s design is highly symbolic—it takes the form of abstracted concrete wings, spread toward the bridge. As users ascend through the floors, the structure gradually “opens”, revealing increasingly broader views, bringing them closer to the birds and sky. Furthermore, the way visitors climb the tower mimics the vertical flight of birds. Unlike a perfectly straight ascent, a bird’s flight consists of micro-deviations, creating a complex, almost spiral-like path. Accordingly, the tower’s base is shaped as a perfect triangle, where each platform transition builds this organic movement. Additionally, this spatial organization ensures that each platform offers a completely different perspective—whether looking at the interior or exterior of the bridge, at different heights, creating a dynamic experience of movement and landscape perception, much like a bird’s own perspective (

Figure 12).

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Birds and Their Habitat

The core motive of the project is to return (urban) space to birds, from whom it was “taken” due to inadequate development of Belgrade throughout its history. On the other hand, the challenge of preserving crucial elements and characteristics of the ecosystems through which birds migrate temporarily or reside permanently represents an issue of regional and global significance, far beyond the borders of Belgrade.

As such, these ecosystems form a complex interplay of natural and artificial elements, whose dynamics can be unpredictable and do not conform to rigid strategic plans in the way purely man-made structures often do—where precise planning is possible. For this very reason—fostering synergy between built and natural structures—the intervention aims to encourage a dynamic balance, avoiding rigid strategic planning, thus allowing nature to adapt on its own and find its (new) continuity. This fundamental characteristic of natural systems and their elements—adaptability—enables the creation of a hybrid naturality, essential for sustainable urban planning of the cities of the future.

4.2.2. Biodiversity

“Birds serve as an excellent indicator of changes in nature and its environment. Considering their relatively well-studied nature, they are very convenient for assessing the state and trends.” [

8] (p. 9)

As their life cycle relies upon the protection of various habitats along their migration routes, migratory birds are especially relevant bioindicators of various ecological changes. Moreover, this is reciprocal – birds also act as vital members of regional food chains, whether they are on top or bottom of it. This influence is evident in the regulation of plant and animal species populations that follow birds through various ecosystems; one of the primary goals of establishing a migratory station is to prevent the dangerous disruption of delicate interconnections between various species included in Belgrade’s ecological niches. In other words, protecting migratory birds in Belgrade does not only mean safeguarding individual species but also maintaining the ecological network that ensures the functionality of natural processes and the stability of biodiversity in urban and suburban areas. In turn, strong ecological networks further reinforce the position of individual species within the system.

4.2.3. The Connection Between Humans and Nature

In this project, the direct link between humans and nature serves a dual purpose: educational and research-oriented (

Figure 13).

The educational aspect focuses on raising awareness about the challenges facing migratory birds and their conservation at a time when we are witnessing the systemic destruction of their habitats and rapid shifts in both global and microclimates. It was essential for the project to be culturally enriching, as this approach encourages broader community engagement in seeking new solutions. The creation of an interactive pathway simulating the flight route of the osprey, accompanied by informational panels, provided a spontaneous and engaging way to achieve this goal. Additionally, birdwatching enthusiasts gain a significant hub for their activity right in the city center.

The research part of the program includes non-invasive tracking, monitoring and tagging birds in their new, hybrid habitat. This initiative aims to assist ornithologists, whose work has become increasingly difficult because of widespread habitat destruction. In the future, the development of similar stations would enhance the existing international research network and continue to expand its educational and scientific mission.

4.3. Discussion – Three Main Principles

Since the theoretical framework was defined by the studio assignment, the project is deeply rooted in three fundamental objectives that had to be fulfilled — to be socially just, ecologically sustainable, and culturally enriching. That being said, the assignment framework required searching for and identifying an ecological-architectural niche capable of addressing multiple conceptual and programmatic demands of the project — on one hand, heritage reuse, on the other, (urban) biodiversity, and thirdly, the three sustainable chapters within the UN’s 2030 Global Agenda for Sustainable Development (9 – Build resilient infrastructure, 11 – Sustainable cities and communities, 15 – Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems). By placing the task of reconstructing the Old Railway Bridge within the context of broader, global bird conservation challenges described in the Theoretical Background, the response of the intervention and its new role will be examined and discussed through the three aforementioned fundamental principles.

ECOLOGICALLY SUSTAINABLE – Recognizing the challenges faced by migratory birds and the inability of the urban environment to meet their needs, the project intentionally transforms into a habitat for migratory birds — as a non-human species — insisting on the fact that cities, as human-centered spaces, have become overly hostile environments for other forms of life. While certain bird species have adapted and learned to (successfully) rely on human resources within urban areas, this is not the case for most, and they require our assistance. As climate change reduces the availability of food or alters the timing of its accessibility, it becomes necessary to artificially provide these resources when natural ecosystem services fail to do so. The unpredictability of bird migrations, caused by shifting climates — whether through changes in migration distances, timing, or even the complete cessation of seasonal migrations — must be addressed through a new green infrastructure, capable of offering essential temporary stop-over stations or permanent habitats, carefully designed to meet the needs of specific bird species. In the context of urbanization, “ceding” the bridge structure to the birds is intended as a reminder within the urban landscape of the devastation of riverbanks and the unregulated urbanization of wetland ecosystems — their original, permanently lost habitats. The core principle insists that proximity to humans should offer shelter rather than persecution and disruption. Additionally, the project aims to harness birds’ natural adaptability — in this case, to new and artificial environments — where that is possible.

SOCIALLY JUST – Although the importance of IBAs (Important Bird Areas) and bird protection measures has long been recognized, the question arises of how to apply these principles within complex urban environments such as Belgrade, where traditional models of conservation often struggle. This project moves beyond the boundaries of expert circles and seeks to involve a broad spectrum of users in a network of ornithological protection and education. Human actors are not limited to professional ornithologists, but also include visitors of diverse profiles — from nature enthusiasts and birdwatchers to casual passersby, families, and tourists, regardless of age, background, or personal relationship with birds and nature. The space of the bridge is designed to accommodate this diversity — with stratified circulation paths and interactive features offering different types of experiences. This affirms the idea that public spaces must be accessible and inclusive, simultaneously protecting nature while enabling people to connect with it in a sustainable and non-invasive way. The bridge, as a historical and cultural landmark, is thus returned to the community not only as an architectural structure, but as a socially just space where ecology, culture, and everyday life intersect.

CULTURALLY ENRICHING – As emphasised in the educational aspect of the project (4.2.3), one of the key intentions of the intervention is to raise public awareness of the challenges faced by migratory birds and their protection. Public awareness of their importance remains insufficient, despite the fact that migratory birds connect different nations across the globe, crossing borders, cultures and landscapes. The project illustrates how human activity — from the way we design our buildings and infrastructure, manage waste, and light our cities — directly impacts survival of migratory birds. The Old Railway Bridge, as a part of Belgrade’s historical landscape, is repurposed to serve not only as a physical structure, but as a cultural reminder of the consequences of environmental neglect. The project has been meticulously designed to engage the local community and cultivate a culture of responsibility towards non-human species. This is achieved through the integration of informative panels, interactive routes, and designated bird-watching points. Ultimately, this culturally enriching approach aims to bridge the gap between urban life and natural ecosystems, reminding people that cities belong to other, non-human residents too.

5. Conclusions

The lack of ecologically sustainable urban planning in Belgrade resulted in long-term consequences – therefore, the re-valuation of the remaining natural areas and the use of modern approaches to biodiversity protection is necessary. Such consequences can be seen in the decrease in the population of migratory birds along the Sava and Danube rivers, along with general ecological degradation. Unfortunately, this negative trend continues.

Modern trends and principles of city development and planning, especially from an ecological perspective, treat sustainability as a goal to be achieved. This requires strict and clearly defined strategic urban planning, which often neglects the current natural flows of the city and its spontaneous, natural development. In contrast to this approach, the migratory station project seeks to introduce necessary change through relatively small intervention in the existing state. The new approach demands the introduction of smaller steps as mechanisms that will activate ecosystem services, allowing the city to continue on its own, in a better way. Therefore, instead of strategic planning of a sustainable future as the ultimate goal, sustainability becomes a mechanism that creates conditions for healthier development of our cities, for its people and all other inhabitants.

Inspired by urban acupuncture, where small, targeted interventions at strategic locations encourage positive spatial, social, and ecological changes in the city, this approach aims to transform cities through well-thought-out ecological and architectural interventions, leaving enough space for cities to internalize new, better practices, improving the entire urban (eco)system. Cities enhanced through this form of micro-interventions collectively form sustainable systems that impact macro-scale well-being, leaving room for the natural ability to develop and adapt to new environmental conditions.

That being said, the further impact of this specific intervention (Migratory Station RS017IBA) should encourage similar actions at other locations, with the goal of building a network of migratory stations that will enable better systemic monitoring, studying, and conservation of migratory birds in a world that is radically changing under human influence. It is crucial for each station to be unique, as a response to the specificities of its own ecosystem niche, which will be further transformed by ecosystem elements through their adaptation to the newly created conditions.

This research was conducted as part of a studio project during the final year (2024–2025) of the Master’s academic studies in architecture at the University of Belgrade – Faculty of Architecture, under the mentorship of Full Professor Dr. Ana Nikezić.

References

- Bauer, S.; Hoye, B. J. Migratory Animals Couple Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning Worldwide. Science 2014, 344(6179), 1242552. [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J. S.; Stattersfield, A. J.; Butchart, S. H.; Evans, M. I.; Grimmett, R. F.; Jones, V. R.; et al. Key Conservation Issues for Migratory Land-and Waterbird Species on the World’s Major Flyways. Bird Conserv. Int. 2008, 18(S1), S49–S73. [CrossRef]

- U Assembly, U. G. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 21 October 2015. A/RES/70/1.

- Directive, E. B. Council Directive 79/409/EEC of 2 April 1979 on the Conservation of Wild Birds. OJ L 1979, 103(25.04), 1979.

- European Commission. Birds Directive. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/nature-and-biodiversity/birds-directive_en (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u 2022. godini: Broj stanovnika, domaćinstava i stanova u Beogradu. Available online: https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2022/HtmlL/G20221350.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Simic, B. The Spatial Transformation of the River Waterfront through Three Historical Periods: A Case Study of Belgrade. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 2020, 4(2), 27–36. [CrossRef]

- Puzović, S.; Sekulić, G.; Stojnić, N.; Grubač, B.; Tucakov, M. Značajna područja za ptice u Srbiji; Ministarstvo zaštite životne sredine i prostornog planiranja, Zavod za zaštitu prirode Srbije, Pokrajinski sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine i održivi razvoj: Belgrade, Serbia, 2009.

- Marzluff, J. M.; Ewing, K. Restoration of Fragmented Landscapes for the Conservation of Birds: A General Framework and Specific Recommendations for Urbanizing Landscapes. In Urban Ecology: An International Perspective on the Interaction between Humans and Nature; Marzluff, J. M., Shulenberger, E., Endlicher, W., Alberti, M., Bradley, G., Ryan, C., ZumBrunnen, C., Simon, U., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 739–755.

- Isaksson, C. Impact of Urbanization on Birds. Bird Species 2018, 235, 257.

- Isaksson, C. Urbanization, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: A Question of Evolving, Acclimatizing or Coping with Urban Environmental Stress. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29(7), 913–923. [CrossRef]

- La Sorte, F. A.; Fink, D.; Buler, J. J.; Farnsworth, A.; Cabrera-Cruz, S. A. Seasonal Associations with Urban Light Pollution for Nocturnally Migrating Bird Populations. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23(11), 4609–4619. [CrossRef]

- Van Doren, B. M.; Horton, K. G.; Dokter, A. M.; Klinck, H.; Elbin, S. B.; Farnsworth, A. High-Intensity Urban Light Installation Dramatically Alters Nocturnal Bird Migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114(42), 11175–11180. [CrossRef]

- Bonnet-Lebrun, A. S.; Manica, A.; Rodrigues, A. S. Effects of Urbanization on Bird Migration. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 244, 108423. [CrossRef]

- Walther, G. R.; Post, E.; Convey, P.; Menzel, A.; Parmesan, C.; Beebee, T. J.; et al. Ecological Responses to Recent Climate Change. Nature 2002, 416(6879), 389–395. [CrossRef]

- Kovjanić, A.; Živanović, V. Uticaj klimatskih promena na migracije i populaciju ptica selica. Zbornik radova mladih istraživača Osmog naučno-stručnog skupa sa međunarodnim učešćem” Planska i normativna zaštita prostora i životne sredine”, Palić-Subotica, 2015; pp. 57–64.

- Both, C.; Visser, M. E. Adjustment to Climate Change Is Constrained by Arrival Date in a Long-Distance Migrant Bird. Nature 2001, 411(6835), 296–298. [CrossRef]

- Visser, M. E.; Perdeck, A. C.; Van Balen, J. H.; Both, C. Climate Change Leads to Decreasing Bird Migration Distances. Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15(8), 1859–1865. [CrossRef]

- Breiner, F. T.; Anand, M.; Butchart, S. H.; Flörke, M.; Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Guisan, A.; et al. Setting Priorities for Climate Change Adaptation of Critical Sites in the Africa-Eurasian Waterbird Flyways. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28(3), 739–752. [CrossRef]

- Preston-Allen, R. G.; Häkkinen, H.; Cañellas-Dols, L.; Ameca y Juarez, E. I.; Orme, C. D. L.; Pettorelli, N. Geography, Taxonomy, Extinction Risk and Exposure of Fully Migratory Birds to Droughts and Cyclones. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2024, 33(1), 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Evans, P. R. Migratory Birds and Climate Change. In Past and Future Rapid Environmental Changes: The Spatial and Evolutionary Responses of Terrestrial Biota; Huntley, B., Cramer, W., Morgan, A. V., Prentice, H. C., Allen, J. R. M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1997; pp. 227–238.

- Bellard, C.; Bertelsmeier, C.; Leadley, P.; Thuiller, W.; Courchamp, F. Impacts of Climate Change on the Future of Biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15(4), 365–377. [CrossRef]

- Bairlein, F. Migratory Birds under Threat. Science 2016, 354(6312), 547–548. [CrossRef]

- Runge, C. A.; Watson, J. E.; Butchart, S. H.; Hanson, J. O.; Possingham, H. P.; Fuller, R. A. Protected Areas and Global Conservation of Migratory Birds. Science 2015, 350(6265), 1255–1258. [CrossRef]

- Bonier, F.; Martin, P. R.; Wingfield, J. C. Urban Birds Have Broader Environmental Tolerance. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3(6), 670–673. [CrossRef]

- BirdLife International. Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs). Available online: https://datazone.birdlife.org/about-our-science/ibas (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- BirdLife International. Country Factsheet: Serbia. Available online: https://datazone.birdlife.org/country/factsheet/serbia (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Lukinović, M.; Jovanović, L. Branding Belgrade as a Bird Watching Destinations.

- Boere, G. C.; Galbraith, C. A.; Stroud, D. A., Eds. Waterbirds around the World: A Global Overview of the Conservation, Management and Research of the World’s Waterbird Flyways; The Stationery Office: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2006, p 68.

- Denac, D.; Schneider-Jacoby, M.; Štumberger, B., Eds. Adriatic Flyway: Closing the Gap in Bird Conservation; Euronatur Foundation: Radolfzell, Germany, 2010.

- Milovanović, B.; Stanojević, G.; Radovanović, M. Climate of Serbia. In The Geography of Serbia: Nature, People, Economy; Geographical Institute “Jovan Cvijić” SASA: Belgrade, Serbia, 2022; pp. 57–68.

- Ðurđić, S.; Stojković, S.; Šabić, D. Nature Conservation in Urban Conditions: A Case Study from Belgrade, Serbia. Maejo Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2011, 5(1), 129.

- Симић, И. Мoгућнoсти унапређења резилијентнoсти урбане фoрме на климатске прoмене. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2016.

- Veselinović, M.; Golubović-Ćurguz, V.; Nikolić, B.; Nešić, N.; Cvejić, M. Neka zaštićena prirodna dobra na području gradske zone Beograda. In Scientific Conference „Management of Forest Ecosystems in National Parks and Other Protected Areas”, Zbornik radova, Jahorina-NP Sutjeska; Jahorina-NP Sutjeska, 2006; pp. 137–143.

- Nikezić, A. Enhancing Biocultural Diversity of Wild Urban Woodland through Research-Based Architectural Design: Case Study—War Island in Belgrade, Serbia. Sustainability 2022, 14(18), 11445. [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, A. A. Трећи Беoград: Преглед развoја урбанистичке мисли и делoвања у периoду oд 1921. гoдине дo данас. Arhitekt. Urban. 2018, (46), 16–25.

- Simić, I. Investitorski urbanizam vs klimatske promene: Kako je ekološki ugrožena beogradska obala Save? Klima101. Available online: https://klima101.rs/ekoloska-ugrozenost-savsko-priobalje/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Stanković, D.; Raković, M.; Paunović, M. Atlas migratornih ptica i slepih miševa Srbije; Ministarstvo zaštite životne sredine Republike Srbije, Ministarstvo kulture i informisanja Republike Srbije, Prirodnjački muzej u Beogradu: Belgrade, Serbia, 2019.

- Mullarney, K.; Svensson, L.; Zetterström, D. Birds of Europe, 3rd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2023.

- Barker, M. A.; Wolfson, E. R. The Birdhouse Book: Building, Placing, and Maintaining Great Homes for Great Birds, 2nd ed.; Cool Springs Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021.

- Raja, V. B.; Palanikumar, K.; Renish, R. R.; Babu, A. G.; Varma, J.; Gopal, P. Corrosion Resistance of Corten Steel–A Review. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 46, 3572–3577.

- Ilijevski, A. D. The Art of Engineering: The First Railway Bridge in Belgrade. Zbornik Matice Srpske za Likovne Umetnosti 2020, (48), 229–242.

- Ministry of Construction, Transport and Infrastructure of the Republic of Serbia, Directorate for Inland Waterways “Plovput”. Navigation Chart of Sava River, 6th ed.; Plovput: Belgrade, Serbia, 2020.

- Österlöf, S. Migration, Wintering Areas, and Site Tenacity of the European Osprey Pandion h. haliaetus (L.). Ornis Scand. 1977, 61–78.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).