Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

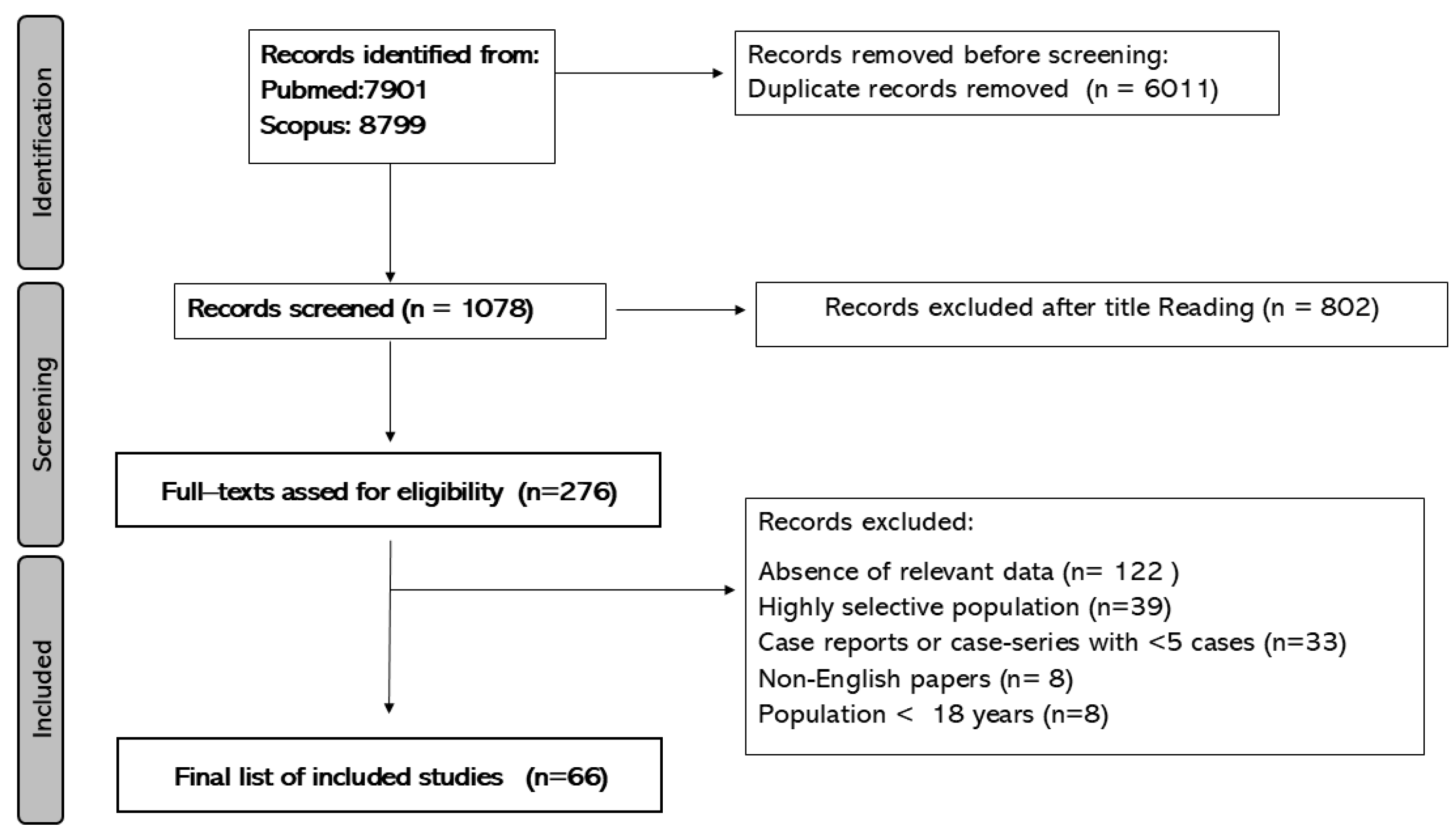

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Table 1. List of inflammation and immune related potential biomarkers associated with complex regional pain syndrome | ||||||

| Author, year | n | Cytocines | Cells | Autoantibodies | Neuropeptides | Others |

| Hartmannsberger et al, 2024 [32] | 25 | ↑Local mast cells and Langerhans cells (acute phase)± Local mast cells and Langerhans cells (chronic phase) | ||||

| Parkitny et al.,2022 [56] | 69 | ± immediate post fracture levels of IL** | ± immediate post fracture levels of T Cells | |||

| Bharwani et al, 2020 [19] | 23 | ↑sIL-2R | ||||

| Russo et al, 2020 [60] | 44 | ↓ IL-37, ↓GM-CSF | ||||

| Baerlecken et al, 2019 [17] | 36 | IgG to P29ING4 | ||||

| Russo et al, 2019 [61] | 14 | ↓ number of central memory CD8+, CD4+ T lymphocytes | ↑p38 signalling in CD1+ mDCs (dendritic cell type activation ?) | |||

| Bharwani et al, 2017 [9] | 80 | ↑sIL-2R | ||||

| Yetişgin et al,2016 [75] | 21 | ± blood cellular counts | ±: VS , CRP | |||

| Dirckx et al 2015 [27] | 66 | ↑ IL-6, TNF-a | ||||

| Dirckx et al, 2015 [28] | 296 | Antineuronal IgG | ||||

| Antinuclear IgG | ||||||

| Birklein et al,2014 [21] | 55 | ↑ local IL-6 | ↑Local mast cells | ↑ local tryptase | ||

| ↑ local TNF-α | ||||||

| Ritz et al, 2011 [59] | 25 | ± proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-a) | ↑ CD14+ CD16+ monocytes | |||

| ±IL-10 | ± T helper cells (CD4+ CD8- ), T cytotoxic cells (CD4- CD8+ ), NK cells (CD56+ ), B cells (CD19+ ), monocytes/macrophages (CD14+ ) | |||||

| Orlova et al, 2011 [55] | 41 | ↑interleukin1 receptor antagonist | ||||

| ↑ monocyte chemotactic protein-1 | ||||||

| ±IL-6, TNFα | ||||||

| ±Interferon-gamma, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10 | ||||||

| Kohr et al, 2011 [47] | 20 | IgG to b2 adrenergic and/or the muscarinic-2 receptors | ||||

| Kaufmann et al,2009 [45] | 10 | ↑ anandamide | ||||

| Kohr et al, 2009 [48] | 30 | IgG to SH-SY5Y (inducible autonomic nervous system autoantigen) | ||||

| Schinkel et al, 2009 [62] | 25 | ± IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-11, IL-12 | ±White Blood Cell Count | ↑ Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide | ↑Soluble TNF Receptor I and II | |

| ± TNF, IL6 | ↑ Substance P | ±CRP | ||||

| Wesseldijk et al,2009 [71] | 66 | ±IgE, tryptase | ||||

| Wesseldijk et al,2008 [74] | 12 | ↑ local TNF-α | ||||

| ↑ local IL-6 | ||||||

| Chronic phase | ± IL6, TNF-α | |||||

| Kaufmann et al, 2007 [44] | 15 | ± Lymphocites | ||||

| ↓cytotoxic CD8+ lymphocytes; IL-2-producing T cell | ||||||

| Uçeyler et al, 2007 [70] | 40 | ↓ IL-10, Transforming growth factor beta 1 | ± Whole blood counts | ± CPR | ||

| ↑IL-2 | ||||||

| ± TNF-α, IL-6 | ||||||

| ± IL-4 | ||||||

| Alexander et al, 2007 [14] | 22 | ↑ CSF IL-6 | ||||

| ↓ CSF IL-2, IL-10 | ||||||

| ↑ CSF Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 | ||||||

| Heijmans-Antonissen et al 2006 [33] | 22 | ↑ local IL-6 | ||||

| ↑ local TNF-α | ||||||

| ± local IFNγ, IL-2, IL-2R, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10 | ||||||

| ↓eotaxin | ||||||

| Schinkel et al, 2006 [63] | 25 | ↑ IL-8 | ± leukocytes | ↑ Subastance P | ↓soluble forms of selectins | |

| ±IL-6 | ± Neuropeptide Y | ±CRP | ||||

| ± CGRP | ↑soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I/II | |||||

| Tan et al, 2005 [67] | 6 | ↑ Local leukocytes | ||||

| Alexander et al, 2005 [15] | 24 | ↑ CSF IL-6 / IL-1 | ||||

| ± CSF TNF-α | ||||||

| Munnikes et al, 2005 [54] | 25 | ↑ local IL-6 | ||||

| ↑ local TNF-α | ||||||

| Chronic phase | ± local IL-6 | |||||

| Chronic phase | ± local TNF-α | |||||

| Blaes et al, 2004 [22] | 12 | ↑IgG Myenteric plexus | ||||

| Huygen et al, 2004 [39] | 20 | ↑ local IL-6 | ↑tryptase | |||

| ↑ local TNF-α | ||||||

| Huygen et al, 2002 [38] | 9 | ↑ local IL-6 | ||||

| ↑ local TNF-α | ||||||

| ± local IL-1b , IL-1b | ||||||

| Birklein et al, 2001 [20] | 19 | ↑ Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide | ||||

| Ribbers et al, 1998 [58] | 13 | ± Cell distribution (B and T lymphocyte populations) | ||||

| Blair et al, 1998 [23] | 61 | ↑ Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide | ||||

| ± Neurokinin | ||||||

| ↑Bradykinin | ||||||

| CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid; IL: Interleukins; **: IL-1β, IL-10, IFN-α, IL-6, IL-12, RANTES, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, MIP-1α, GM-CSF, MIP-1β; MCP-1, IL-5, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1Ra, IL-2 , IL-7, IP-10 , IL-2r, MIG , IL-4 = interleukin-4, IL-8; GM-CSF: Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; tCr =total creatine levels; * N-acetylaspartate, tCr and potassium; TMS : transmagnetic strimulation; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; AA: Aminoacids; ± No difference /correlation ; VS: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein levels, | ||||||

| Table 2: Genetic, epigenetic, brain imaging and functional neurophysiological biomarkers associated of complex regional pain syndrome | ||||||

| Author, year | n | Genetic and epigenetics | Brain imaging | Functional neurophysiological | Other biomarkers | |

| Strutural | Metabolic | |||||

| Hok et al, 2024 [34] | 51 | ↓ antinociceptive modulation via the brainstem antinociceptive system | ||||

| Shaikh et al, 2024 [64] | Single-nucleotide polymorphism of genes ANO10, P2RX7, PRKAG1 and SLC12A9 | |||||

| Hotta et al.,2023 [37] | 17 | Sustained somatotopic alteration of the somatosensory cortex | ||||

| Delon-Martin et al.,2023 [25] | 11 | ↑ localized activation in the primary somatosensory cortex ( transcranial magnetic stimulation) | ||||

| Zhu et al.,2023 [7] | 9 | Five top five hub genes: MMP9, PTGS2, CXCL8, OSM, TLN1 | ||||

| Hong et al,,2023 [35] | 21 | ↑ functional connectivity in the somatosensory (S1) subnetworks | ||||

| ↓functional connectivity in the prefronto-parieto-cingulo-thalamic subnetworks | ||||||

| Lee et al., 2022 [51] | 15 | ↑ Basal ganglia infra-slow oscillations | ||||

| ↑ Basal ganglia resting connectivity | ||||||

| Domim et al, 2021 [29] | 24 | ↓ insula and bilateral grey matter medial thalamus. | ||||

| König et al, 2021 [49] | 25 | ↓ activity of angiotensin-converting enzyme | ||||

| Azqueta-Gavaldon et al, 2020 [16] | 20 | ↓gray matter density in the putamen/ functional connectivity increases amongst the putamen and pre-/postcentral gyri and cerebellum | ||||

| Russo et al, 2020 [60] | 44 | ↓ tryptophan | ||||

| Di Pietro et al., 2020 [26] | 15 | ↑ thalamo-S1 functional connectivity | ||||

| Bruehl et al 2019 [24] | 9 | Altered methylation of specific genes (COL11A1 and HLA-DRB6) | ||||

| Jung et al, 2019 [42] | 12 | Disruption of interactions between specific central and metabolic metabolites* in the thalamus | ||||

| Kohle et al,2019 [46] | 15 | ↓ activation of subthalamic nucleus, nucleus accumbens, and putamen | ||||

| Jung, et al, 2018 [43] | 12 | Anormal interactions of lipid13a and L f lipid 09 in the thalamus with peripheral tCr | ||||

| Hotta et al, 2017 [36] | 13 | Abnormal neural activity in sensorimotor and pain related areas | ||||

| Shokouhi et al, 2017 [66] | 28 | ↓grey matter in somatosensory cortex, and limbic system | ↓ perfusion in somatosensory cortex, and limbic system (early phase) | |||

| ↑ perfusion in somatosensory cortex, and limbic system (late phase) | ||||||

| Janicki et al, 2016 [40] | 230 | ±Common Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

||||

| Zhou et al, 2015 [76] | 35 | ↑ volume of choroid plexus | ||||

| Lee et al,2015 [52] | 25 | ↓ cortical thinning in the prefrontal cortex | ||||

| Pleger et al, 2014 [57] | 15 | ↑ in gray matter density in dorsomedial prefrontal | ||||

| ↑ in gray matter density located in the primary motor cortex (contralateral to the affected limb) | ||||||

| Krämer et al, 2014 [50] | 33 | ↑ Osteoprotegerin |

||||

| Barad et al, 2013 [18] | 15 | ↓ grey matter volume in pain related areas (dorsal insula, orbitofrontal cortex, cingulate cortex. | ||||

| Jin et al 2013 [41] | 24 | Increased expression of MMP9 | ||||

| Alexander et al, 2013 [13] | 160 | ↑ AA: L-Aspartate, L-glutamate, L-ornithine | ||||

| ↓ L-tryptophan and L-arginine | ||||||

| Lenz et al, 2011 [53] | 21 | ↓ Somatosensory cortex inhibition | ||||

| Orlova et al, 2011 [55] | 41 | ↑Specific microRNA: hsa-miR-532-3p | ↑ Vascular endothelial growth factor | |||

| Walton et al, 2010 [69] | 64 | Altered magneto-encephalographic imaging (thalamo-cortical Dysrhythmia) | ||||

| Wesseldijk et al, 2008 [73] | 64 | ↑ NMDA excitatory amino acids: glutamate, glutamine, glycine, taurine and arginine | ||||

| Wesseldijk et al, 2008 [72] | 35 | ↑ serotonin |

||||

| Geha et al, 2008 [31] | 26 | ↓ insula, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens; fractional anisotropy in cingulum-callosal bundle | ||||

| Turton et al,2007 [68] | 8 | ↓ motor response to TMS | ||||

| Alexander et al, 2007 [14] | 22 | ↑ CSF Calcium and glutamate | ||||

| ↑ CSF Glial fibrillary acidic protein | ||||||

| ↑ CSF Nitric oxide metabolites | ||||||

| Uçeyler et al, 2007 [70] | 40 | ↓ mRNA IL-4, IL-8, IL-10 | ||||

| ± transforming growth factor-b1mRNA | ||||||

| ↑ TNF and IL-2 mRNA level | ||||||

| Janicki et al, 2016 [40] | 230 | ±Common Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms | ||||

| Shiraishi et al, 2006 [65] | 18 | ↑ activity in somatosensory cortex | ||||

| ↓ contralateral activity in specific motor areas | ||||||

| Huygen et al, 2004 [39] | 20 | ± prostaglandin E2 | ||||

| Eisenberg et al, 2004 [30] | 38 | ±Endothelin-1 | ||||

| CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid; IL: Interleukins; GM-CSF: Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; tCr =total creatine levels; * N-acetylaspartate, tCr and potassium; TMS : transmagnetic strimulation;; AA: Aminoacids; ± No difference /correlation | ||||||

| Table 3. Evaluation of the Quality of Cross-sectional Studies Based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | |||||||

| Newcastle-Ottawa Scale Items | |||||||

| Study | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | C | O | Total |

| Hartmannsberger et al, 2024 [32] | * | - | * | ** | * | ** | 7 |

| Delon-Martin et al, 2024 [25] | * | - | * | ** | * | ** | 7 |

| Bharwani et al, 2020 [19] | * | - | * | ** | * | ** | 7 |

| Baerlecken et al, 2019 [17] | * | - | * | ** | * | *** | 9 |

| Dirckx et al, 2015 [28] | * | - | * | ** | * | ** | 7 |

| Kohr et al, 2011 [47] | * | - | * | ** | * | * | 6 |

| Alexander et al, 2007 [14] | * | - | * | ** | - | * | 5 |

| Heijmans-Antonissen et al, 2006 [33] | * | - | * | ** | * | * | 6 |

| Alexander et al,2005 [15] | * | - | * | ** | * | ** | 7 |

| Blaes et al, 2004 [22] | * | - | * | * | * | * | 5 |

| Blair et al, 1998 [23] | * | - | * | * | * | * | 5 |

| Abbreviations: S= Selection; S1, representativeness; S2, selection of the unexposed; S3,exposure determination; S4,outcome not present at the beginning of the study C: Comparability; B; O: OutcomesGreen 7(good); orange:5.6(satisfactory); red: 4(unsatisfactory). | |||||||

| Table 4. Evaluation of the Quality of Case Controls Based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale | |||||||

| Newcastle-Ottawa Scale Items | |||||||

| Study | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | C | E | Total |

| Shaikh et al,2024 [64] | * | * | * | * | ** | *** | 9 |

| Hok et al, 2024 [34] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Hotta et al, 2023 [37] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Hong et al, 2023 [35] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Zhu et al, 2023 [7] | * | * | * | * | ** | *** | 9 |

| Lee et al, 2022 [51] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Parkitny et al, 2022 [56] | * | * | - | * | ** | *** | 8 |

| Orlova et al 2011 [55] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| König et al, 2021 [49] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Domim et al, 2021 [29] | |||||||

| Azqueta-Gavaldon et al, 2020 [16] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Russo et al, 2020 [60] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Di Pietro et al,2020 [26] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Russo et al, 2019 [61] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | 6 |

| Kohler et al, 2019 [46] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Jung et al, 2019 [42] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Jung et al, 2018 [43] | * | * | - | * | * | ** | 6 |

| Bruehl et al, 2019 [24] | * | * | - | * | ** | *** | 8 |

| Wesseldijk et al,2009 [71] | * | * | * | * | ** | *** | 9 |

| Wesseldijk et al,2008 [74] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Shokouhi et al 2017 [66] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Bharwani et al, 2017 [9] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Hotta et al, 2017 [36] | * | * | - | * | ** | * | 6 |

| Yetişgin et al, 2016 [75] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Zhou et al, 2015 [76] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Lee et al, 2015 [52] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Dirckx et al, 2015 [27] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Barad et al, 2014 [18] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Krämer et al, 2014 [50] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Birklein et al,2014 [21] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Pleger et al,2014 [57] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Jin et al, 2013 [41] | * | * | * | * | ** | *** | 9 |

| Alexander et al, 2013 [13] | * | - | - | * | ** | ** | 6 |

| Lenz et 2011 [53] | * | * | * | * | ** | *** | 9 |

| Ritz et al, 2011 [59] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Walton et al, 2010 [69] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Kaufmann et al, 2009 [45] | * | - | - | * | * | ** | 5 |

| Kohr et al, 2009 [48] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Schinkel et al, 2009 [62] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Geha et al, 2008 [31] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Wesseldijk et al, 2008 [73] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Wesseldijk et al, 2008 b)[72] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Kaufmann et al.,2007 [44] | * | - | - | * | * | *** | 6 |

| Uçeyler et al, 2007 [70] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Turton et al, 2007 [68] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Janicki et al, 2016 [40] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Schinkel et al,2006 [63] | * | * | * | * | ** | *** | 9 |

| Shiraishi et al,2006 [65] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Munnikes et al, 2005 [54] | * | - | - | * | ** | ** | 6 |

| Tan et al, 2005 [67] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Eisenberg et al,2004 [30] | * | * | - | * | ** | *** | 8 |

| Huygen et al, 2004 [39] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Huygen et al, 2002 [38] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Birklein et al, 2001 [20] | * | * | - | * | ** | ** | 7 |

| Ribbers et al, 1998 [58] | * | * | * | * | ** | ** | 8 |

| Abbreviations: S1 case definition; S2 case representativenes; S3 control seletion, S4 control definition; C: Comparability; E, Exposure.Green ≥7(good); Orange:5.6 (satisfactory); red: ≤4 (unsatisfactory). | |||||||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Velzen, G.A.J.; Perez, R.S.G.M.; Van Gestel, M.A.; Huygen, F.J.P.M.; Van Kleef, M.; Van Eijs, F.; Dahan, A.; Van Hilten, J.J.; Marinus, J. Health-Related Quality of Life in 975 Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1. Pain 2014, 155, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, R.N.; McCabe, C.S.; Goebel, A.; Massey, M.; Suvar, T.; Grieve, S.; Bruehl, S. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Practical Diagnostic and Treatment Guidelines, 5th Edition. Pain Med. 2022, 23, S1–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, A.; Barker, C.; Birklein, F.; Brunner, F.; Casale, R.; Eccleston, C.; Eisenberg, E.; McCabe, C.S.; Moseley, G.L.; Perez, R.; et al. Standards for the Diagnosis and Management of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Results of a European Pain Federation Task Force. Eur. J. Pain 2019, 23, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limerick, G.; Christo, D.K.; Tram, J.; Moheimani, R.; Manor, J.; Chakravarthy, K.; Karri, J.; Christo, P.J. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Evidence-Based Advances in Concepts and Treatments. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2023, 27, 269–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruehl, S. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. BMJ 2015, 351, h2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangnus, T.J.P.; Bharwani, K.D.; Dirckx, M.; Huygen, F.J.P.M. From a Symptom-Based to a Mechanism-Based Pharmacotherapeutic Treatment in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Drugs 2022, 82, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Wen, B.; Xu, L.; Huang, Y. Identification of Potential Inflammation-Related Genes and Key Pathways Associated with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Li, Z.-Y.; Yu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ni, M.-H.; Xie, H.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y.-X.; Li, J.-L.; Cui, G.-B.; et al. Gray Matter Abnormalities in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Voxel-Based Morphometry Studies. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharwani, K.D.; Dirckx, M.; Stronks, D.L.; Dik, W.A.; Schreurs, M.W.J.; Huygen, F.J.P.M. Elevated Plasma Levels of sIL-2R in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Pathogenic Role for T-Lymphocytes? Mediators Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 2764261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkitny, L.; McAuley, J.H.; Di Pietro, F.; Stanton, T.R.; O’Connell, N.E.; Marinus, J.; Van Hilten, J.J.; Moseley, G.L. Inflammation in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurology 2013, 80, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birklein, F.; Schmelz, M. Neuropeptides, Neurogenic Inflammation and Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS). Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 437, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Well, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The NewcastleOttawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analysis. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/oxford (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Alexander, G.M.; Reichenberger, E.; Peterlin, B.L.; Perreault, M.J.; Grothusen, J.R.; Schwartzman, R.J. Plasma Amino Acids Changes in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain Res. Treat. 2013, 2013, 742407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, G.M.; Perreault, M.J.; Reichenberger, E.R.; Schwartzman, R.J. Changes in Immune and Glial Markers in the CSF of Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2007, 21, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.M.; van Rijn, M.A.; van Hilten, J.J.; Perreault, M.J.; Schwartzman, R.J. Changes in Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in CRPS. Pain 2005, 116, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azqueta-Gavaldon, M.; Youssef, A.M.; Storz, C.; Lemme, J.; Schulte-Göcking, H.; Becerra, L.; Azad, S.C.; Reiners, A.; Ertl-Wagner, B.; Borsook, D.; et al. Implications of the Putamen in Pain and Motor Deficits in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain 2020, 161, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baerlecken, N.T.; Gaulke, R.; Pursche, N.; Witte, T.; Karst, M.; Bernateck, M. Autoantibodies against P29ING4 Are Associated with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Immunol. Res. 2019, 67, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barad, M.J.; Ueno, T.; Younger, J.; Chatterjee, N.; Mackey, S. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Is Associated with Structural Abnormalities in Pain-Related Regions of the Human Brain. J. Pain 2014, 15, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharwani, K.D.; Dirckx, M.; Stronks, D.L.; Dik, W.A.; Huygen, F.J.P.M.; Dozio, E. Serum Soluble Interleukin-2 Receptor Does Not Differentiate Complex Regional Pain Syndrome from Other Pain Conditions in a Tertiary Referral Setting. Mediators Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birklein, F.; Schmelz, M.; Schifter, S.; Weber, M. The Important Role of Neuropeptides in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Neurology 2001, 57, 2179–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birklein, F.; Drummond, P.D.; Li, W.; Schlereth, T.; Albrecht, N.; Finch, P.M.; Dawson, L.F.; Clark, J.D.; Kingery, W.S. Activation of Cutaneous Immune Responses in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Pain 2014, 15, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaes, F.; Schmitz, K.; Tschernatsch, M.; Kaps, M.; Krasenbrink, I.; Hempelmann, G.; Bräu, M.E. Autoimmune Etiology of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (M. Sudeck). Neurology 2004, 63, 1734–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, S.J.; Chinthagada, M.; Hoppenstehdt, D.; Kijowski, R.; Fareed, J. Role of Neuropeptides in Pathogenesis of Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy. Acta Orthop. Belg. 1998, 64, 448–451. [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl, S.; Gamazon, E.R.; Van De Ven, T.; Buchheit, T.; Walsh, C.G.; Mishra, P.; Ramanujan, K.; Shaw, A. DNA Methylation Profiles Are Associated with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome after Traumatic Injury. Pain 2019, 160, 2328–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delon-Martin, C.; Lefaucheur, J.-P.; Hodaj, E.; Sorel, M.; Dumolard, A.; Payen, J.-F.; Hodaj, H. Neural Correlates of Pain-Autonomic Coupling in Patients With Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Treated by Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Motor Cortex. Neuromodulation J. Int. Neuromodulation Soc. 2024, 27, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, F.; Lee, B.; Henderson, L.A. Altered Resting Activity Patterns and Connectivity in Individuals with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 3781–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirckx, M.; Stronks, D.L.; van Bodegraven-Hof, E. a. M.; Wesseldijk, F.; Groeneweg, J.G.; Huygen, F.J.P.M. Inflammation in Cold Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2015, 59, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirckx, M.; Schreurs, M.W.J.; de Mos, M.; Stronks, D.L.; Huygen, F.J.P.M. The Prevalence of Autoantibodies in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I. Mediators Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 718201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domin, M.; Strauss, S.; McAuley, J.H.; Lotze, M. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Thalamic GMV Atrophy and Associations of Lower GMV With Clinical and Sensorimotor Performance Data. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 722334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, E.; Erlich, T.; Zinder, O.; Lichinsky, S.; Diamond, E.; Pud, D.; Davar, G. Plasma Endothelin-1 Levels in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Eur. J. Pain Lond. Engl. 2004, 8, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geha, P.Y.; Baliki, M.N.; Harden, R.N.; Bauer, W.R.; Parrish, T.B.; Apkarian, A.V. The Brain in Chronic CRPS Pain: Abnormal Gray-White Matter Interactions in Emotional and Autonomic Regions. Neuron 2008, 60, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmannsberger, B.; Scriba, S.; Guidolin, C.; Becker, J.; Mehling, K.; Doppler, K.; Sommer, C.; Rittner, H.L. Transient Immune Activation without Loss of Intraepidermal Innervation and Associated Schwann Cells in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijmans-Antonissen, C.; Wesseldijk, F.; Munnikes, R.J.; Huygen, F.J.; van der Meijden, P.; Hop, W.C.J.; Hooijkaas, H.; Zijlstra, F.J. Multiplex Bead Array Assay for Detection of 25 Soluble Cytokines in Blister Fluid of Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1. Mediators Inflamm. 2006, 2006, 28398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hok, P.; Strauss, S.; McAuley, J.; Domin, M.; Wang, A.P.; Rae, C.; Moseley, G.L.; Lotze, M. Functional Connectivity in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Bicentric Study. NeuroImage 2024, 301, 120886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Suh, C.; Namgung, E.; Ha, E.; Lee, S.; Kim, R.Y.; Song, Y.; Oh, S.; Lyoo, I.K.; Jeong, H.; et al. Aberrant Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Network-Based Statistics Analysis. Exp. Neurobiol. 2023, 32, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotta, J.; Saari, J.; Koskinen, M.; Hlushchuk, Y.; Forss, N.; Hari, R. Abnormal Brain Responses to Action Observation in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Pain 2017, 18, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotta, J.; Saari, J.; Harno, H.; Kalso, E.; Forss, N.; Hari, R. Somatotopic Disruption of the Functional Connectivity of the Primary Sensorimotor Cortex in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023, 44, 6258–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huygen, F.J.P.M.; De Bruijn, A.G.J.; De Bruin, M.T.; Groeneweg, J.G.; Klein, J.; Zijlstra, F.J. Evidence for Local Inflammation in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1. Mediators Inflamm. 2002, 11, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huygen, F.J.P.M.; Ramdhani, N.; van Toorenenbergen, A.; Klein, J.; Zijlstra, F.J. Mast Cells Are Involved in Inflammatory Reactions during Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1. Immunol. Lett. 2004, 91, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicki, P.K.; Alexander, G.M.; Eckert, J.; Postula, M.; Schwartzman, R.J. Analysis of Common Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Genome Wide Association Study Approach and Pooled DNA Strategy. Pain Med. Malden Mass 2016, 17, 2344–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.-H.; Zhang, E.; Ko, Y.; Sim, W.S.; Moon, D.E.; Yoon, K.J.; Hong, J.H.; Lee, W.H. Genome-Wide Expression Profiling of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.-H.; Kim, H.; Lee, D.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, W.J.; Moon, J.Y.; Kim, Y.C.; Choi, S.-H.; Kang, D.-H. Disruption of Homeostasis Based on the Right and Left Hemisphere in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Neuroimmunomodulation 2019, 26, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.-H.; Kim, H.; Jeon, S.Y.; Kwon, J.M.; Lee, D.; Choi, S.-H.; Kang, D.-H. Aberrant Interactions of Peripheral Measures and Neurometabolites with Lipids in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Using Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy: A Pilot Study. Mol. Pain 2018, 14, 1744806917751323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, I.; Eisner, C.; Richter, P.; Huge, V.; Beyer, A.; Chouker, A.; Schelling, G.; Thiel, M. Lymphocyte Subsets and the Role of Th1/Th2 Balance in Stressed Chronic Pain Patients. Neuroimmunomodulation 2007, 14, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, I.; Hauer, D.; Huge, V.; Vogeser, M.; Campolongo, P.; Chouker, A.; Thiel, M.; Schelling, G. Enhanced Anandamide Plasma Levels in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Following Traumatic Injury: A Preliminary Report. Eur. Surg. Res. Eur. Chir. Forsch. Rech. Chir. Eur. 2009, 43, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, M.; Strauss, S.; Horn, U.; Langner, I.; Usichenko, T.; Neumann, N.; Lotze, M. Differences in Neuronal Representation of Mental Rotation in Patients With Complex Regional Pain Syndrome and Healthy Controls. J. Pain 2019, 20, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohr, D.; Singh, P.; Tschernatsch, M.; Kaps, M.; Pouokam, E.; Diener, M.; Kummer, W.; Birklein, F.; Vincent, A.; Goebel, A.; et al. Autoimmunity against the Β2 Adrenergic Receptor and Muscarinic-2 Receptor in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain 2011, 152, 2690–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohr, D.; Tschernatsch, M.; Schmitz, K.; Singh, P.; Kaps, M.; Schäfer, K.-H.; Diener, M.; Mathies, J.; Matz, O.; Kummer, W.; et al. Autoantibodies in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Bind to a Differentiation-Dependent Neuronal Surface Autoantigen. Pain 2009, 143, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, S.; Steinebrey, N.; Herrnberger, M.; Escolano-Lozano, F.; Schlereth, T.; Rebhorn, C.; Birklein, F. Reduced Serum Protease Activity in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: The Impact of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme and Carboxypeptidases. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 205, 114307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, H.H.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Szalay, G.; Breimhorst, M.; Eberle, T.; Zieschang, K.; Rauner, M.; Schlereth, T.; Schreckenberger, M.; Birklein, F. Osteoprotegerin: A New Biomarker for Impaired Bone Metabolism in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome? Pain 2014, 155, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Di Pietro, F.; Henderson, L.A.; Austin, P.J. Altered Basal Ganglia Infraslow Oscillation and Resting Functional Connectivity in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Neurosci. Res. 2022, 100, 1487–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-H.; Lee, K.-J.; Cho, K.I.K.; Noh, E.C.; Jang, J.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Kang, D.-H. Brain Alterations and Neurocognitive Dysfunction in Patients With Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Pain 2015, 16, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, M.; Höffken, O.; Stude, P.; Lissek, S.; Schwenkreis, P.; Reinersmann, A.; Frettlöh, J.; Richter, H.; Tegenthoff, M.; Maier, C. Bilateral Somatosensory Cortex Disinhibition in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I. Neurology 2011, 77, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munnikes, R.J.M.; Muis, C.; Boersma, M.; Heijmans-Antonissen, C.; Zijlstra, F.J.; Huygen, F.J.P.M. Intermediate Stage Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1 Is Unrelated to Proinflammatory Cytokines. Mediators Inflamm. 2005, 2005, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, I.A.; Alexander, G.M.; Qureshi, R.A.; Sacan, A.; Graziano, A.; Barrett, J.E.; Schwartzman, R.J.; Ajit, S.K. MicroRNA Modulation in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2011, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkitny, L.; McAuley, J.H.; Herbert, R.D.; Di Pietro, F.; Cashin, A.G.; Ferraro, M.C.; Moseley, G.L. Post-Fracture Serum Cytokine Levels Are Not Associated with a Later Diagnosis of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Case-Control Study Nested in a Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleger, B.; Draganski, B.; Schwenkreis, P.; Lenz, M.; Nicolas, V.; Maier, C.; Tegenthoff, M. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I Affects Brain Structure in Prefrontal and Motor Cortex. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbers, G.M.; Oosterhuis, W.P.; van Limbeek, J.; de Metz, M. Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy: Is the Immune System Involved? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1998, 79, 1549–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, B.W.; Alexander, G.M.; Nogusa, S.; Perreault, M.J.; Peterlin, B.L.; Grothusen, J.R.; Schwartzman, R.J. Elevated Blood Levels of Inflammatory Monocytes (CD14+ CD16+ ) in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2011, 164, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.A.; Georgius, P.; Pires, A.S.; Heng, B.; Allwright, M.; Guennewig, B.; Santarelli, D.M.; Bailey, D.; Fiore, N.T.; Tan, V.X.; et al. Novel Immune Biomarkers in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Neuroimmunol. 2020, 347, 577330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.A.; Fiore, N.T.; Van Vreden, C.; Bailey, D.; Santarelli, D.M.; McGuire, H.M.; Fazekas De St Groth, B.; Austin, P.J. Expansion and Activation of Distinct Central Memory T Lymphocyte Subsets in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinkel, C.; Scherens, A.; Köller, M.; Roellecke, G.; Muhr, G.; Maier, C. Systemic Inflammatory Mediators in Post-Traumatic Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS I) - Longitudinal Investigations and Differences to Control Groups. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2009, 14, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinkel, C.; Gaertner, A.; Zaspel, J.; Zedler, S.; Faist, E.; Schuermann, M. Inflammatory Mediators Are Altered in the Acute Phase of Posttraumatic Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Clin. J. Pain 2006, 22, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, S.S.; Goebel, A.; Lee, M.C.; Nahorski, M.S.; Shenker, N.; Pamela, Y.; Drissi, I.; Brown, C.; Ison, G.; Shaikh, M.F.; et al. Evidence of a Genetic Background Predisposing to Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1. J. Med. Genet. 2024, 61, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraishi, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Nihashi, T.; Kato, K.; Iwano, S.; Nishino, M.; Ishigaki, T.; Ikeda, M.; Kato, T.; Ito, K.; et al. Cerebral Glucose Metabolism Change in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A PET Study. Radiat. Med. 2006, 24, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokouhi, M.; Clarke, C.; Morley-Forster, P.; Moulin, D.E.; Davis, K.D.; St Lawrence, K. Structural and Functional Brain Changes at Early and Late Stages of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Pain 2018, 19, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.C.T.H.; Oyen, W.J.G.; Goris, R.J.A. Leukocytes in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I. Inflammation 2005, 29, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turton, A.J.; McCabe, C.S.; Harris, N.; Filipovic, S.R. Sensorimotor Integration in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Study. Pain 2007, 127, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, K.D.; Dubois, M.; Llinás, R.R. Abnormal Thalamocortical Activity in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) Type I. Pain 2010, 150, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üçeyler, N.; Eberle, T.; Rolke, R.; Birklein, F.; Sommer, C. Differential Expression Patterns of Cytokines in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain 2007, 132, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseldijk, F.; van Toorenenbergen, A.W.; van Wijk, R.G.; Huygen, F.J.; Zijlstra, F.J. IgE-Mediated Hypersensitivity: Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1 (CRPS1) vs the Dutch Population. A Retrospective Study. Pain Med. Malden Mass 2009, 10, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseldijk, F.; Fekkes, D.; Huygen, F.J.; Bogaerts-Taal, E.; Zijlstra, F.J. Increased Plasma Serotonin in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1. Anesth. Analg. 2008, 106, 1862–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseldijk, F.; Fekkes, D.; Huygen, F.J.P.M.; van de Heide-Mulder, M.; Zijlstra, F.J. Increased Plasma Glutamate, Glycine, and Arginine Levels in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2008, 52, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesseldijk, F.; Huygen, F.J.P.M.; Heijmans-Antonissen, C.; Niehof, S.P.; Zijlstra, F.J. Six Years Follow-up of the Levels of TNF-Alpha and IL-6 in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1. Mediators Inflamm. 2008, 2008, 469439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetişgin, A.; Tutoğlu, A.; Cinakli, A.; Kul, M.; Boyaci, A. Platelet and Erythrocyte Indexes in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I. Arch. Rheumatol. 2016, 31, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Hotta, J.; Lehtinen, M.K.; Forss, N.; Hari, R. Enlargement of Choroid Plexus in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruehl, S.; Harden, R.N.; Galer, B.S.; Saltz, S.; Backonja, M.; Stanton-Hicks, M. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Are There Distinct Subtypes and Sequential Stages of the Syndrome? Pain 2002, 95, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage, S.; Goodnow, C.C. Organ-Specific Autoimmune Disease. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 194, F31–F36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangnus, T.J.P.; Bharwani, K.D.; Dik, W.A.; Baart, S.J.; Dirckx, M.; Huygen, F.J.P.M. Is There an Association between Serum Soluble Interleukin-2 Receptor Levels and Syndrome Severity in Persistent Complex Regional Pain Syndrome? Pain Med. 2023, 24, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, J.; Shukla, R.; Pandey, P.C. Effect of Prednisolone on Clinical and Cytokine mRNA Profiling in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Mol. Neurosci. MN 2024, 74, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huygen, F.J.P.M.; Niehof, S.; Zijlstra, F.J.; van Hagen, P.M.; van Daele, P.L.A. Successful Treatment of CRPS 1 with Anti-TNF. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2004, 27, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirckx, M.; Groeneweg, G.; Wesseldijk, F.; Stronks, D.L.; Huygen, F.J.P.M. Report of a Preliminary Discontinued Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Anti-TNF-α Chimeric Monoclonal Antibody Infliximab in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain Pract. Off. J. World Inst. Pain 2013, 13, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orstavik, K. Pathological C-Fibres in Patients with a Chronic Painful Condition. Brain 2003, 126, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahmoush, A.J.; Schwartzman, R.J.; Hopp, J.L.; Grothusen, J.R. Quantitative Sensory Studies in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1/RSD: Clin. J. Pain 2000, 16, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).