1. Introduction

DSLs are seasonal sub-lakes that emerge on sandbars within the main lake basin during dry seasons. During high-water periods, these DSLs are integrated into the larger Poyang Lake system, whereas in low-water seasons, they become isolated water bodies, forming a distinctive "lake-within-a-lake" landscape [

1]. DSLs are formed primarily through natural sediment deposition and anthropogenic modification. Sediment transported by upstream rivers accumulates in Poyang Lake, creating shallow depressions. Human activities, such as constructing low embankments and installing sluices, further define the DSLs boundaries [

2]. DSLs provide favorable environmental conditions for wetland ecosystem development, supporting plankton, floating and submerged vegetation, benthic fauna, fish, and waterbirds. They play a crucial role in maintaining global ecosystem integrity and biodiversity [

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, the recent significant changes in the hydrological regime of the middle and lower Yangtze River, coupled with increasingly frequent extreme flood and drought events, have substantially altered DSLs habitats. First, these dual drivers have modified key hydrological processes in DSLs, including water levels, flood/drawdown timing, and inundation durations [

7]. Second, aquatic vegetation has become increasingly disturbed. Prolonged and widespread inundation hampers photosynthesis and causes root hypoxia, hindering normal growth. Conversely, during droughts, emergent and hygrophilous species invade habitats of submerged and floating-leaved vegetation, shrinking their spatial niches [

8,

9]. Third, such changes in hydrology and vegetation indirectly threaten overwintering waterbirds occupying higher trophic levels. The loss of essential habitats and food shortages lead to population fluctuations and declines in species richness, undermining ecosystem function [

10,

11,

12].

Previous studies have shown that large-scale human activities, including land reclamation, sand mining, and upstream dam operations, have significantly altered the hydrological processes of Poyang Lake [

13]. For instance, the regulation of the Three Gorges Dam has altered the natural hydrological regime of Poyang Lake, disrupting its original ecological regimes [

14]. Long-term time series analyses indicate that the amplitude and frequency of water level fluctuations significantly influence the spatial distribution of wetlands. In particular, excessively low water levels during the dry season lead to substantial wetland contraction and diminished hydrological connectivity, thereby impacting the habitats and reproductive conditions of aquatic species [

15,

16,

17].

Changes in DSLs water levels are closely linked to aquatic plant growth cycles. Low water levels encourage expansion of emergent vegetation such as reeds, constraining submerged vegetation and reducing species diversity [

18,

19,

20]. Remote sensing and ecological modeling show that declining water levels shrink the range of submerged and floating-leaved vegetation, leading to lower plant abundance and diversity [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Aquatic vegetation is vital to lake ecosystem function—it absorbs nutrients, mitigates eutrophication, and provides bird habitat—so appropriate water-level regulation enhances vegetative diversity and ecosystem services, whereas both excessively high and low levels have adverse effects [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

As water level fluctuations and wetland degradation continue, waterbird habitats become increasingly fragmented. Declining dry-season levels dry out formerly suitable wetlands, reducing habitat quality, and increased hydrological variability further exacerbates fragmentation, threatening spatial continuity of waterbird habitats [

30,

31]. Fragmentation impedes bird migration and heightens habitat instability, particularly for species reliant on large wetlands, such as the Siberian crane [

32]. The interdependence of wetland vegetation, bird habitats, and aquatic organisms underscores the importance of maintaining habitat integrity and ecosystem functionality [

33,

34].

Therefore, investigating the impacts of extreme hydrological events under altered hydrological regimes on the evolution of DSLs habitat elements is crucial for elucidating habitat responses to new hydrological conditions and for enhancing resilience to floods and droughts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Datasets

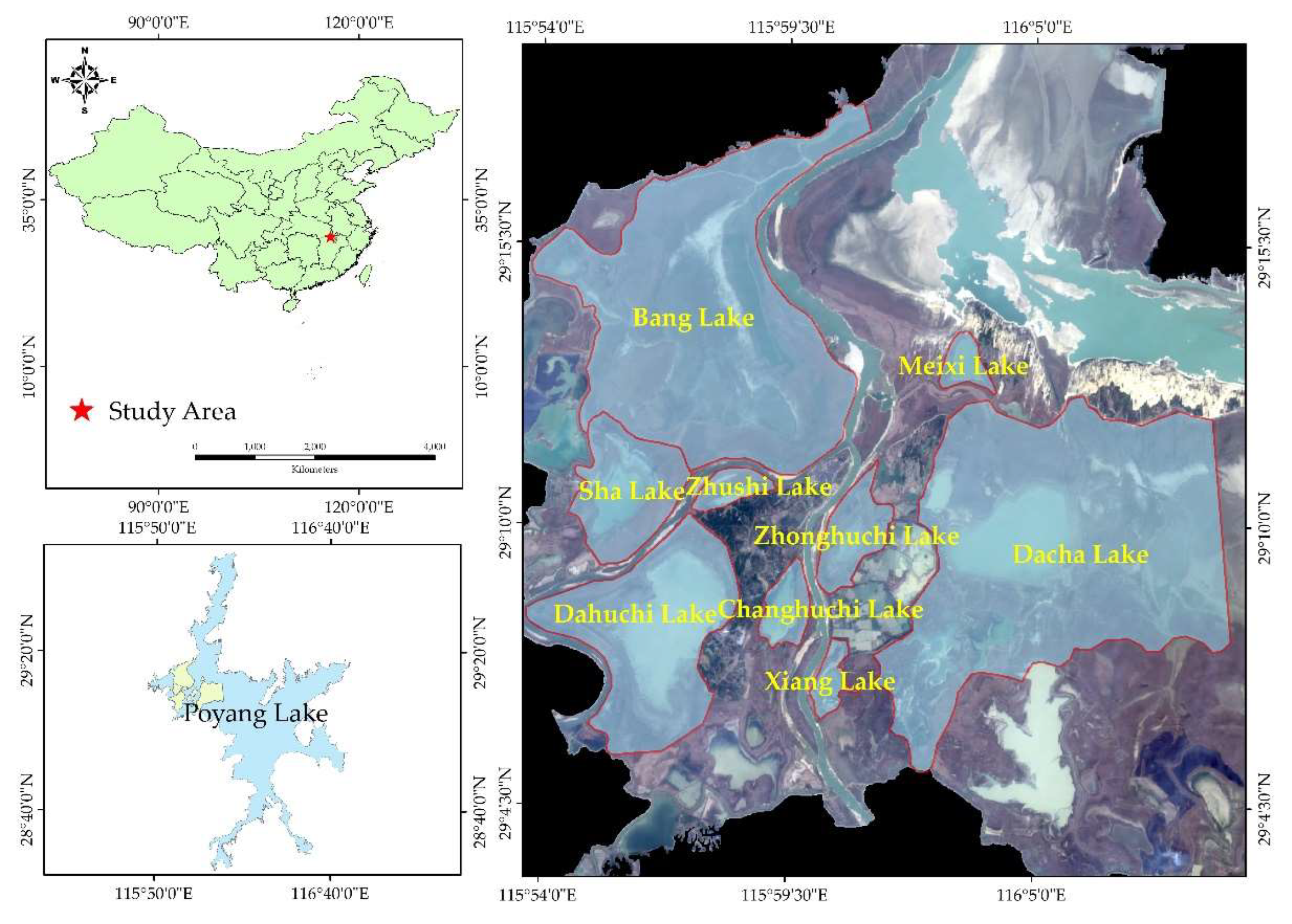

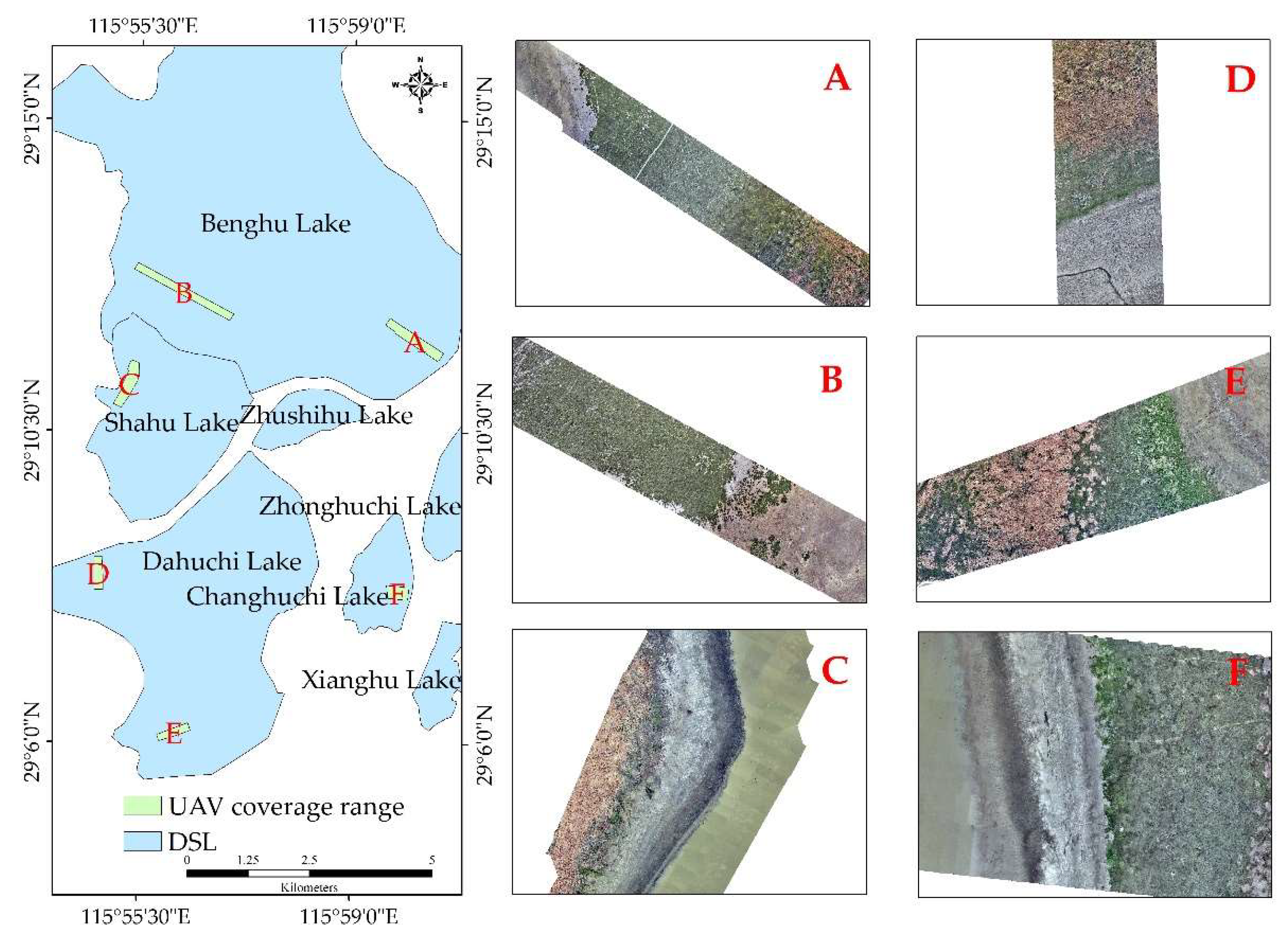

The DSLs investigated in this study are located in the northwestern part of Poyang Lake and form part of the Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve. These DSLs constitute a critical ecological subsystem within the lake–wetland complex. The study area comprises nine DSLs: Shahu Lake, Dachahu Lake, Banghu Lake, Zhushihu Lake, Meixihu Lake, Xianghu Lake, Dahuchi Lake, Changhuchi Lake, and Zhonghuchi Lake (

Figure 1). The region experiences a subtropical humid monsoon climate. From 1986 to 2020, the mean annual temperature in the Poyang Lake wetland was 17.9 °C, with a maximum of 18.1 °C in 2007 and a minimum of 17.8 °C in 2012. Mean annual precipitation was 1550.1 mm, ranging from 967 mm in 2006 to 3250.5 mm in 1998. Following the implementation of fishing bans, the traditional “DSLs enclosed in autumn” fishing practice has been prohibited. Field investigations revealed that some DSLs are currently unmanaged, resulting in damage to dikes and water-control gates and altering their hydrological connectivity with the main lake.

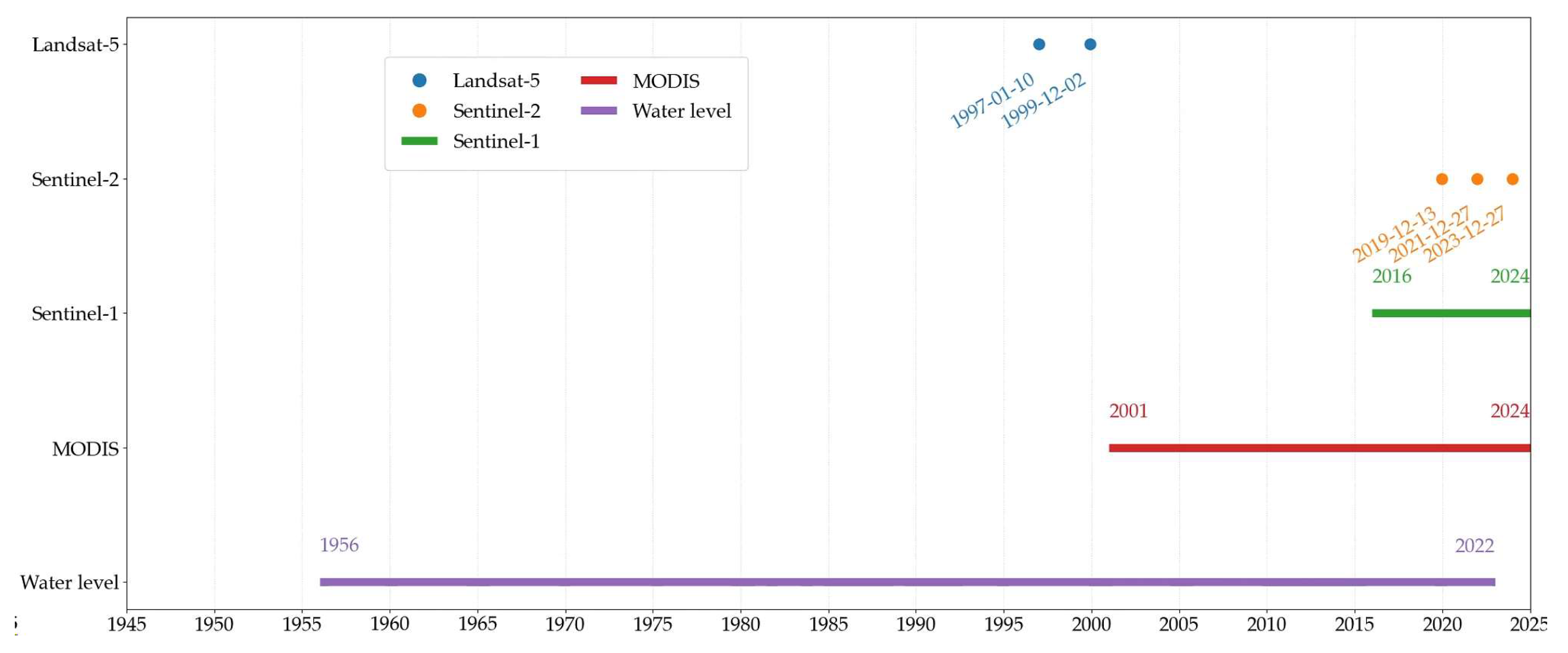

The datasets used in this study include hydrological data, remote sensing imagery, and monitoring records from the nature reserve.

Hydrological data were obtained from the Xingzi hydrological station, a representative station for Poyang Lake. Daily water level observations from 1956 to 2022 were used to analyze long-term trends in hydrological regimes within the DSL region.

Remote sensing imagery included optical satellite images (Landsat-5, Sentinel-2, and MODIS) and microwave radar data (Sentinel-1). Image collection and analysis were conducted using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. Landsat-5 data were obtained from the LANDSAT/LT05/C02/T1 surface reflectance dataset, which has been atmospherically corrected. Sentinel-2 images were sourced from the COPERNICUS/S2_SR_HARMONIZED dataset, processed using the sen2cor correction algorithm. MODIS data (MOD13Q1 V6.1) provided NDVI values from 2001 to 2024 (totaling 522 scenes). Sentinel-1 SAR images were derived from the COPERNICUS/S1_GRD dataset, calibrated and geometrically corrected (422 scenes, 2016–2024).

Due to the dual influence of upstream inflow and the Yangtze River, Poyang Lake exhibits a dynamic hydrological regime characterized by "broad surfaces in wet seasons, narrow lines in dry seasons"[

36]. Optical characteristics of wetland vegetation also vary substantially throughout the year. Given that sandbars and wetlands are mostly exposed during the autumn and winter, and that vegetation growth stabilizes during this period, remote sensing images were selected from December to the following January for the years surrounding the extreme flood (1998, 2020) and drought (2022) events [

37].

Monitoring records were collected from the Jiangxi Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve’s annual ecological resource reports for selected years.

Figure 2.

Temporal distribution of acquired Sentinel-1/2 Landsat-5 MODIS and water level for DSLs of Poyang Lake.

Figure 2.

Temporal distribution of acquired Sentinel-1/2 Landsat-5 MODIS and water level for DSLs of Poyang Lake.

2.2. Habitat-Element Extraction

Habitat features of the DSLs were extracted using the Random Forest (RF) classification algorithm, a robust non-parametric ensemble classifier [

38]. Compared to single decision trees, RF offers higher classification stability and accuracy, and is less sensitive to input data volume or multicollinearity. Spectral bands and vegetation indices from Landsat-5 and Sentinel-2 images were used to construct a feature dataset, including Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI), Bare Soil Index (BSI), Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI), Green Atmospherically Resistant Index (GARI), Visible Atmospherically Resistant Index (VARI), Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (MSAVI), and Plant Senescence Reflectance Index (PSRI). Topographic variables were also incorporated to improve classification accuracy. The classification features used are listed in

Table 1.

2.3. Fractional Vegetation Cover Calculation

Fractional Vegetation Cover (FVC), proposed by Gutman et al. [

39], is calculated using a linear pixel decomposition model based on NDVI values, especially effective in regions with high vegetation density such as wetlands. FVC reflects spatial distribution and density of vegetation and is an important indicator of vegetation growth status. The FVC is calculated as:

FVC represents fractional vegetation cover, NDVIsoil corresponds to the NDVI value of bare soil or non-vegetated areas, and NDVIveg corresponds to the NDVI value of areas with full vegetation coverage. The 95% of the cumulative NDVI distribution is designated as NDVIveg, with NDVI values exceeding this threshold assigned an FVC of 1. Conversely, the 5% is defined as NDVIsoil, with NDVI values below this threshold assigned an FVC of 0.

2.4. Water Surface Area Extraction

Water surface area was extracted using the Sentinel-1 Dual-Polarized Water Index (SDWI), developed by Jia Shichao et al. [

40]:

VV(Vertical-Vertical) and VH (Vertical-Horizontal) are two polarization channels in radar imagery:

VV: Radar signals transmitted and received in the vertical polarization.

VH: Radar signals transmitted in the vertical polarization and received in the horizontal polarization.

The fundamental principle of the Sentinel-1 Dual-Polarized Water Index (SDWI) lies in the differential backscattering characteristics of water bodies in synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery. Water surfaces typically exhibit low backscatter due to strong signal absorption, whereas soil and vegetation exhibit higher backscatter because of stronger signal scattering. By calculating SDWI, the difference between VV and VH channel responses is used to distinguish water bodies from non-water surfaces. In SDWI images, water areas generally appear as low values, while non-water areas display higher values.

A limitation of this algorithm is its inability to effectively differentiate water from terrain-induced shadow, though this issue is not present in the study area due to the absence of mountainous terrain, making the method well-suited for this application. Based on empirical experience, pixels with SDWI values greater than 0.4 were identified as water, and the water surface area of 522 scenes in the dish-shaped lake region from 2016 to 2024 was extracted accordingly.

2.5. Water Area Change Rate Calculation

Based on the water surface areas extracted from Sentinel-1 imagery, the Water Area Change Rate Index (WACRI) was employed to assess the rate of change in the water surface area of the dish-shaped lake system. The WACRI is calculated using the following formula:

Where Ai and Ai+1 are water surface areas at consecutive time points, and ODi and ODi+1 are the corresponding observation dates.

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Accuracy Assessment

The random 30% of the sample points were used as the validation dataset. Classification accuracy was evaluated using statistical metrics including the confusion matrix, overall accuracy (OA), and the Kappa coefficient.

OA measures the overall correctness of the classification process and is calculated as the ratio of correctly classified pixels to the total number of validation pixels. It is particularly suitable for accuracy assessment when the proportions of land cover classes vary significantly. The formula is as follows, where q represents the number of classes, n

ii denotes the diagonal elements of the confusion matrix, and n is the total number of classified pixels:

The Kappa coefficient accounts for agreement occurring by chance between the classified image and the reference dataset. A Kappa value greater than 0.8 indicates near-perfect agreement.

3. Results

3.1. Temporal Variation Characteristics of Water Level

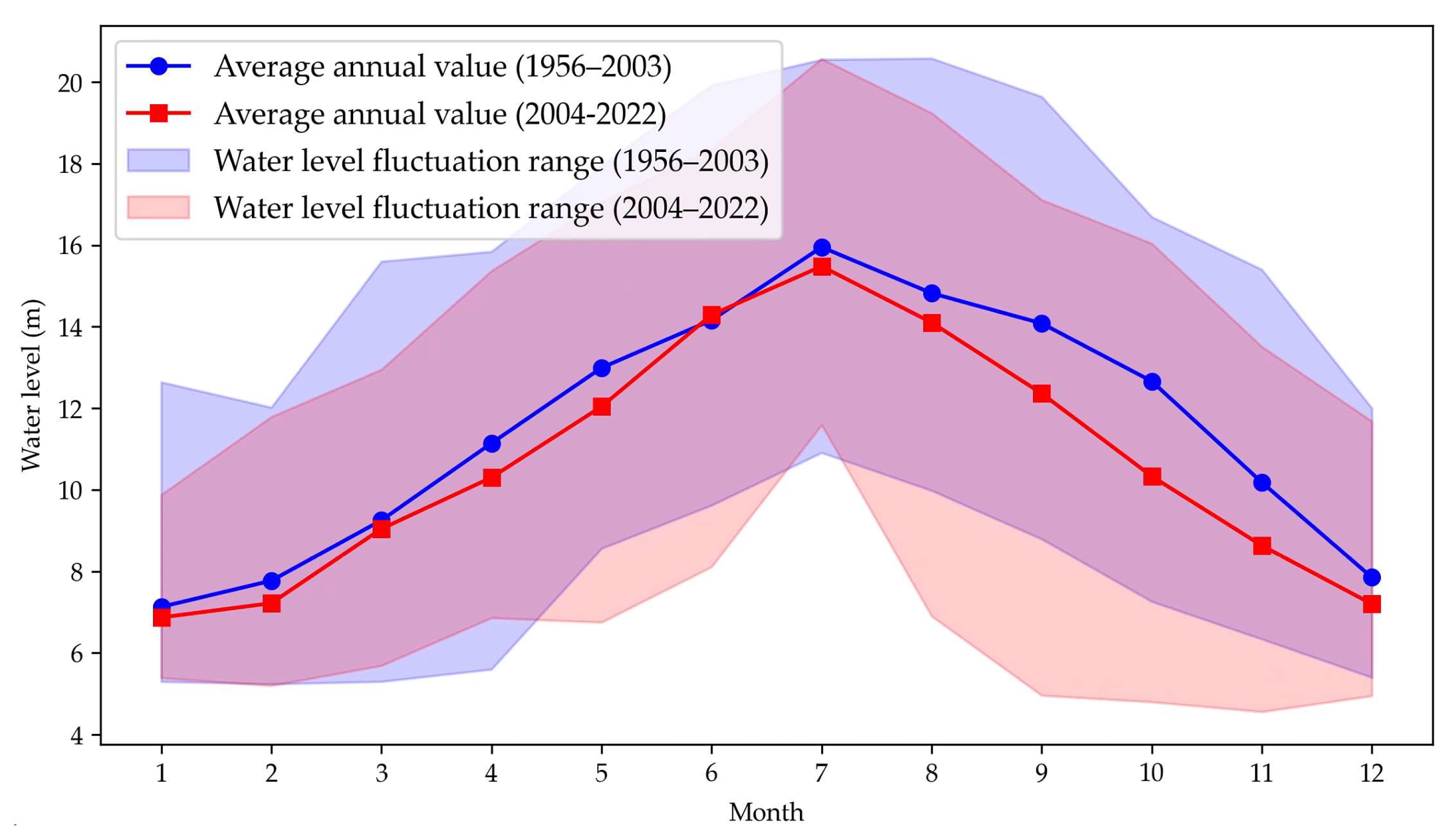

Based on long-term daily water-level observations at Xingzi Station (1956–2022), the long-term mean water level in the study area was 11.28 m, with an observed range of 4.56 m to 20.58 m. Trend analysis reveals a significant downward trajectory over the study period. In particular, 1998 experienced an extreme high-water-level event (annual mean 13.72 m), whereas 2011 registered the lowest annual mean (9.07 m).

Since 2003, the regional hydrological regime has changed markedly. A comparison of monthly mean water levels before and after 2003 shows an overall decline of 0.84 m from 2004 to 2022 (

Figure 3). Changes in maximum monthly water levels exhibit strong temporal heterogeneity: aside from July (nearly unchanged), the annual mean decrease was 1.27 m, with the largest drops in January (–2.76 m), March (–2.65 m), and September (–2.53 m). Minimum water-level changes display a pronounced seasonal pattern, with average declines of 2.41 m in May–June and August–November,most notably in August (–3.08 m), September (–3.83 m), and October (–2.46 m). In contrast, slight increases in monthly minima occurred in March–April and July, with April showing the greatest rise (+1.26 m).

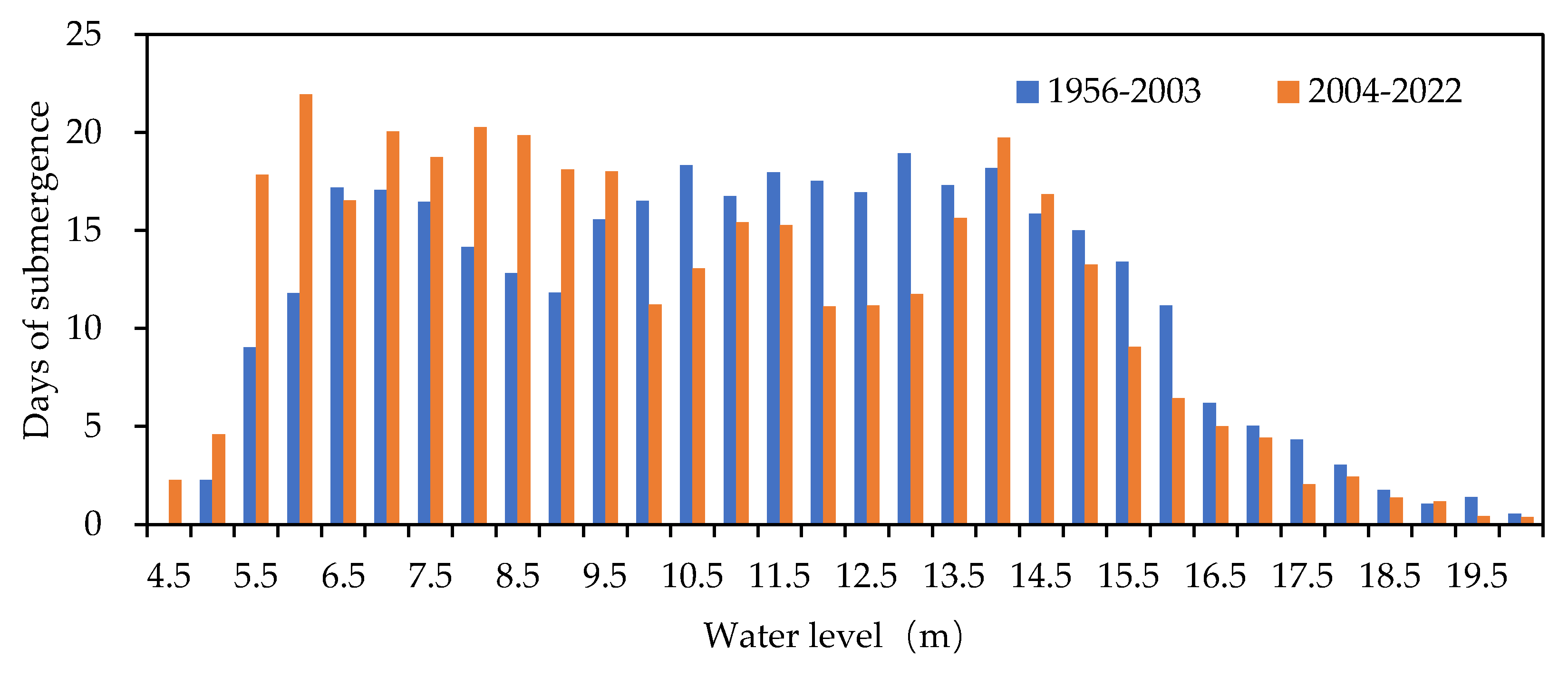

Water level duration was analyzed using 0.5 m elevation intervals (

Figure 4). During 1956–2003, the greatest duration occurred in the 13.0–13.5 m band (18.9 days), with extended durations concentrated between 10.0 m and 14.0 m. From 2004–2022, the pattern shifted markedly: the longest duration fell in the 6.0–6.5 m band (21.9 days), and prolonged durations concentrated in the lower 6.0–10.0 m range, reflecting a substantive alteration of the basin’s hydrological rhythm.

3.2. Evolution Trend of the Habitat of DSLs

3.2.1. Characteristics of Habitat Succession in DSLs Before and After Extreme Flood and Drought Events

Using multi-source satellite imagery at 10/30 m resolution, a Random Forest classifier (OA > 85 %, Kappa > 0.82) was applied to map substrate changes in ecologically sensitive zones during the same seasons one year before and after the 1998 flood, 2020 flood, and 2022 drought (

Figure 5). Habitat transition matrices (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) were then used to quantify conversion pathways among habitat types, thereby revealing vegetation succession patterns driven by extreme hydrological events.

In 1998, the Yangtze Basin experienced a severe flood, which profoundly altered DSLs habitats: mudflat area surged from 62.56 km² in 1997 to 82.75 km² in 1999; submerged vegetation formerly concentrated in nearshore shallow zones of Banghu Lake, Dachahu Lake and Changhuchi Lake reduced and nearly disappeared. Areas of Carex spp. and Phragmites australis changed only modestly, increasing from 42.10 km² and 22.58 km² to 49.06 km² and 25.11 km², respectively; by contrast, Polygonum-Phalaris arundinacea stands declined sharply from 38.93 km² to 25.77 km².

The 2020 flood produced a similar succession pattern: mudflats expanded from 67.88 km² to 79.87 km², and submerged vegetation fell from 6.04 km² to near zero—most of it converting to mudflat, with some areas invaded by Polygonum-Phalaris arundinacea. Carex spp. losses (≈35.09 km²) and Phragmites australis losses (≈10.30 km²) were also predominantly converted into Polygonum-Phalaris arundinacea.

Following the 2022 drought, habitats evolved further: 25.38 km² of former mudflat transitioned to emergent/hygrophilous vegetation, submerged vegetation reappeared, and 44.05 km² and 14.49 km² of Polygonum-Phalaris arundinacea converted into Carex spp. and Phragmites australis, respectively.

3.2.2. Evolution of FVC from 2001 to 2024

FVC effectively reflects the density and spatial distribution of vegetation, particularly herbaceous species [

41,

42,

43]. Since Poyang Lake wetlands are dominated by herbaceous plants, FVC provides an accurate measure of vegetation dynamics in this region [

44,

45,

46].

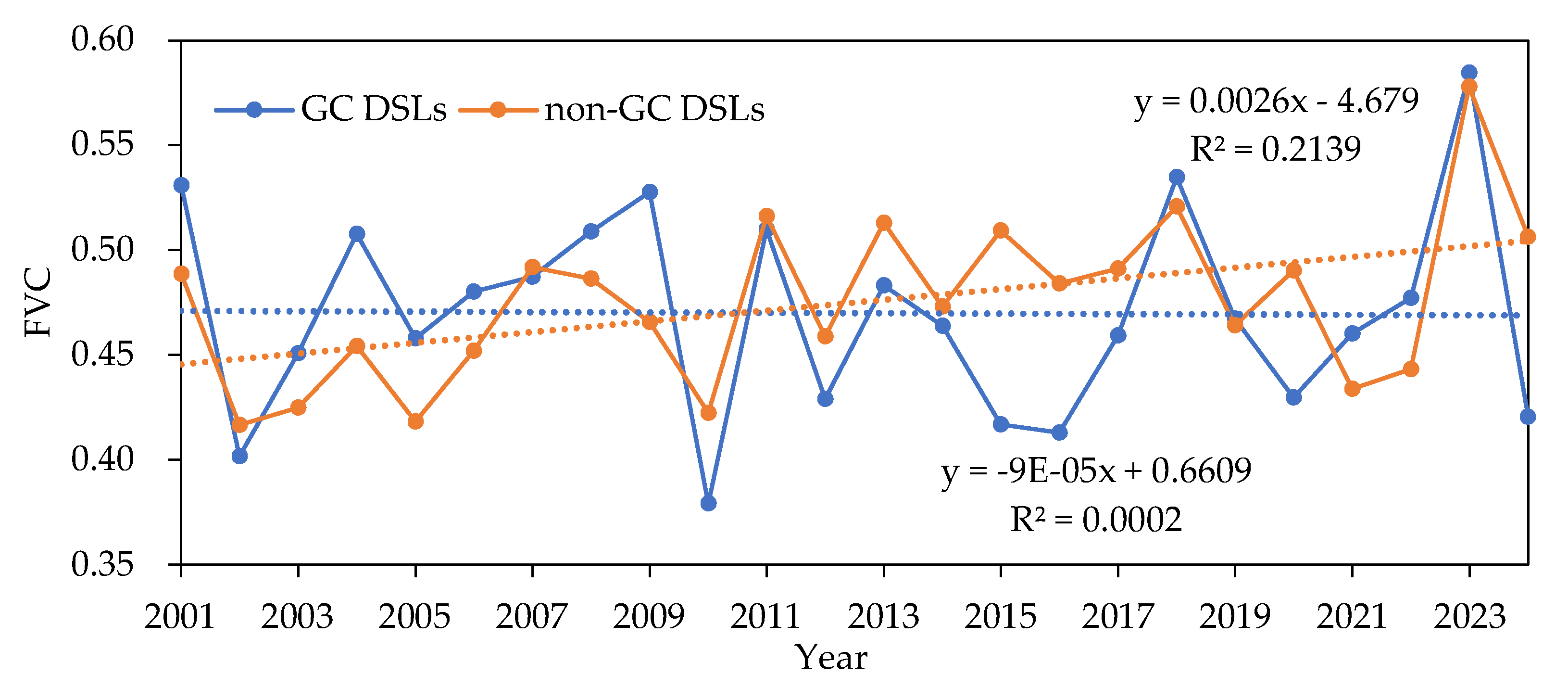

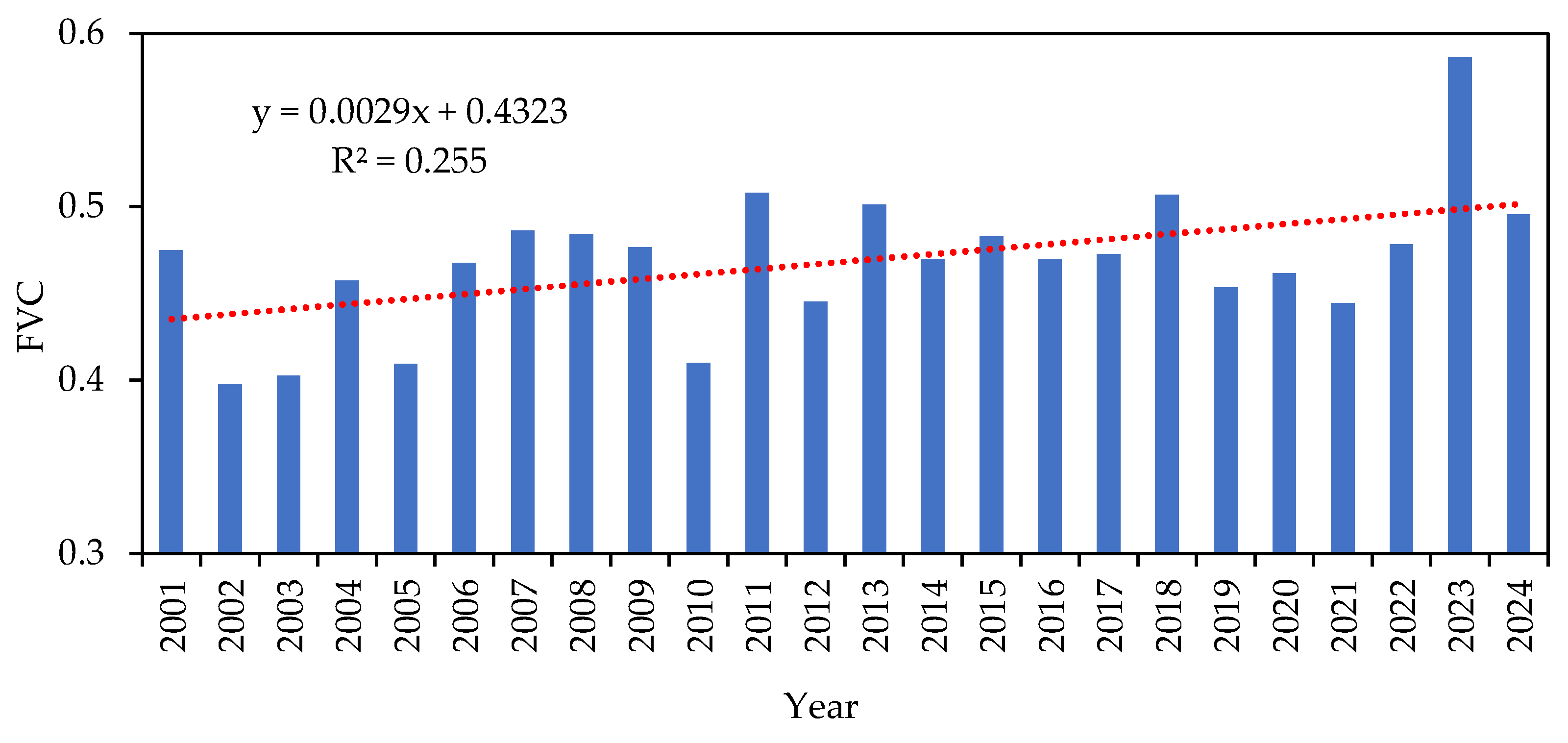

Figure 8.

Annual average FVC trends for GC DSLs and non-GC DSLs from 2001 to 2024.

Figure 8.

Annual average FVC trends for GC DSLs and non-GC DSLs from 2001 to 2024.

From 2001 to 2024, GC DSLs showed no clear long-term trend in FVC, whereas non-GC DSLs exhibited an increasing trend. Interannual analysis revealed that both lake types reached their highest FVC values in 2023 (0.584 for GC DSLs and 0.578 for non-GC DSLs) and their lowest in 2010 (0.379) and 2002 (0.417), respectively. FVC typically peaks in late spring to early summer (April–June) and declines to its minimum in late autumn through winter (October–February), consistent with natural phenology. The mean monthly FVC was 0.470 for GC DSLs and 0.475 for non-GC DSLs, with coefficients of variation of 0.18 and 0.20, respectively, indicating that GC DSLs experienced more stable vegetation cover, while non-GC DSLs subject to greater hydrological fluctuations and extreme events showed larger variability.

Spatial patterns of annual mean FVC (

Figure 9) indicate that emergent and hygrophilous vegetation in non-GC DSLs expanded downslope toward the lake center, whereas GC DSLs maintained a relatively stable spatial distribution.

3.3. Trends in the Changes of Water Characteristics

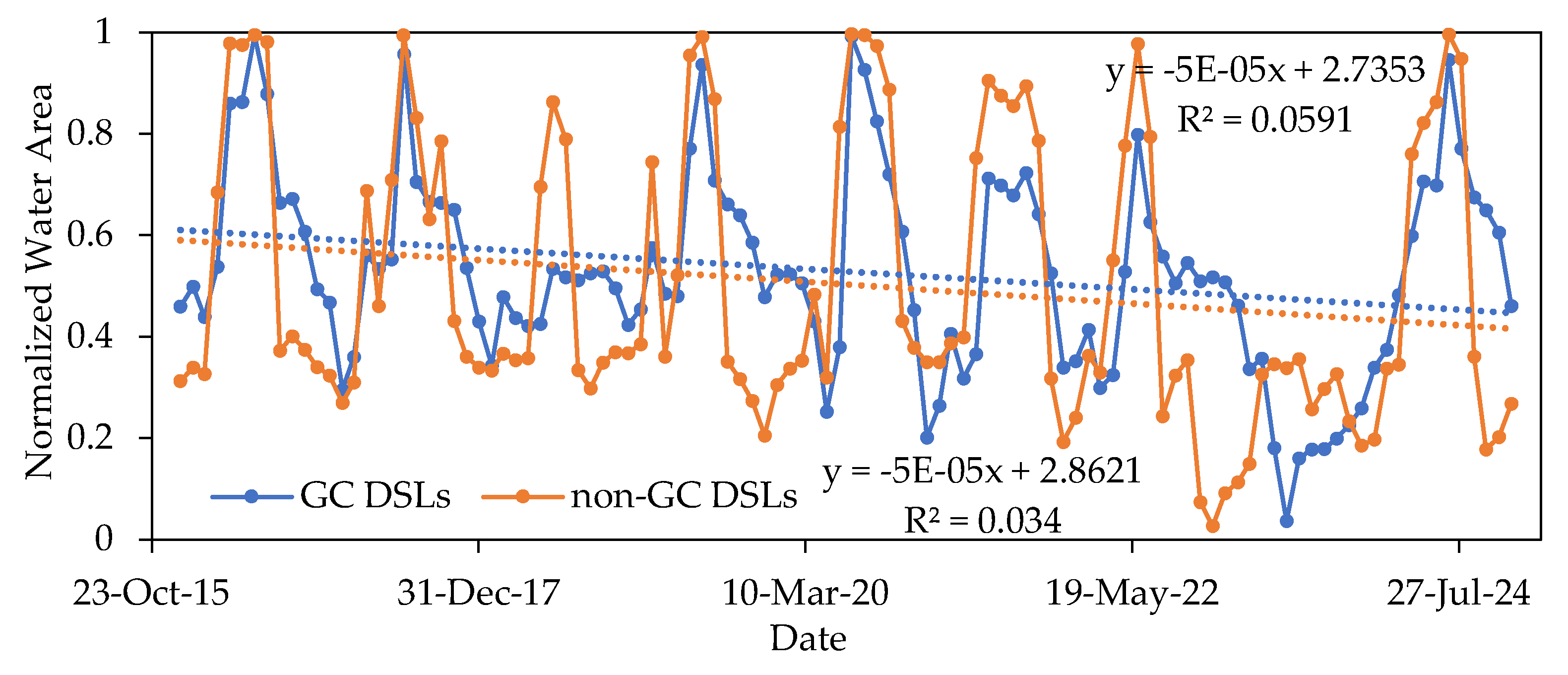

3.3.1. Trends in the Changes of Water Area

From 2016 to 2024, the total water area of the DSLs cluster exhibited a declining trend, with peak annual areas of 153.53 km² in 2016 and 153.05 km² in 2020, and a minimum of 64.06 km² in 2023. The range of water area variation for GC DSLs was 28.38 ± 9.94 km², compared to 104.15 ± 52.00 km² for non-GC DSLs.

Figure 10.

Comparison of normalized water area between GC DSLs and non-GC DSLs from 2016 to 2024.

Figure 10.

Comparison of normalized water area between GC DSLs and non-GC DSLs from 2016 to 2024.

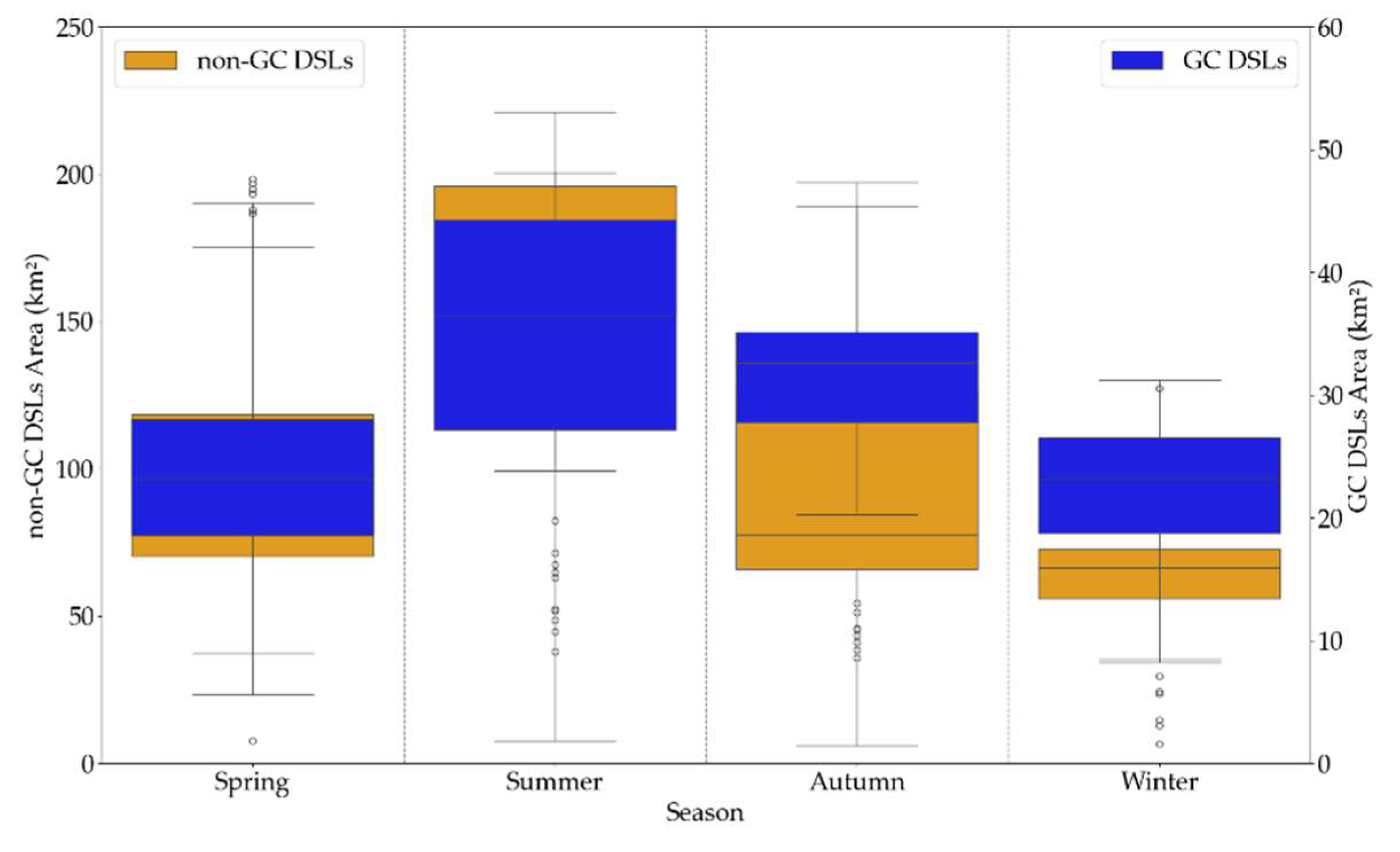

All DSLs displayed pronounced seasonality (

Figure 11). GC DSLs had a slightly larger water area in autumn (September–November, 29.59 km²) than in spring (March–May, 23.77 km²), with maximum area in summer (June–August, 34.98 km²) and minimum in winter (December–February, 22.03 km²). Non-GC DSLs followed a similar pattern, with highest and lowest areas in summer (159.52 km²) and winter (58.92 km²), respectively, but autumn area (58.92 km²) was lower than spring (99.70 km²).

This difference likely arises because hydraulic structures in GC DSLs slow inflow before the flood season; once Poyang Lake water levels exceed the subsidiary embankments, rapid expansion occurs. During recession, these structures also slow outflow, maintaining higher water levels in autumn. In contrast, non-GC DSLs, being naturally connected, respond quickly to both rising and falling lake levels.

During the flood season (April–October), GC DSLs and non-GC DSLs showed closely synchronized area trends (correlation coefficient = 0.9632), whereas in the non-flood season (November–March) the correlation dropped to 0.6942. This further indicates that gate-control projects primarily influence the changes in water area of the DSLs during the non-flood season, while their regulatory effect on the water area during the flood season is relatively minor.

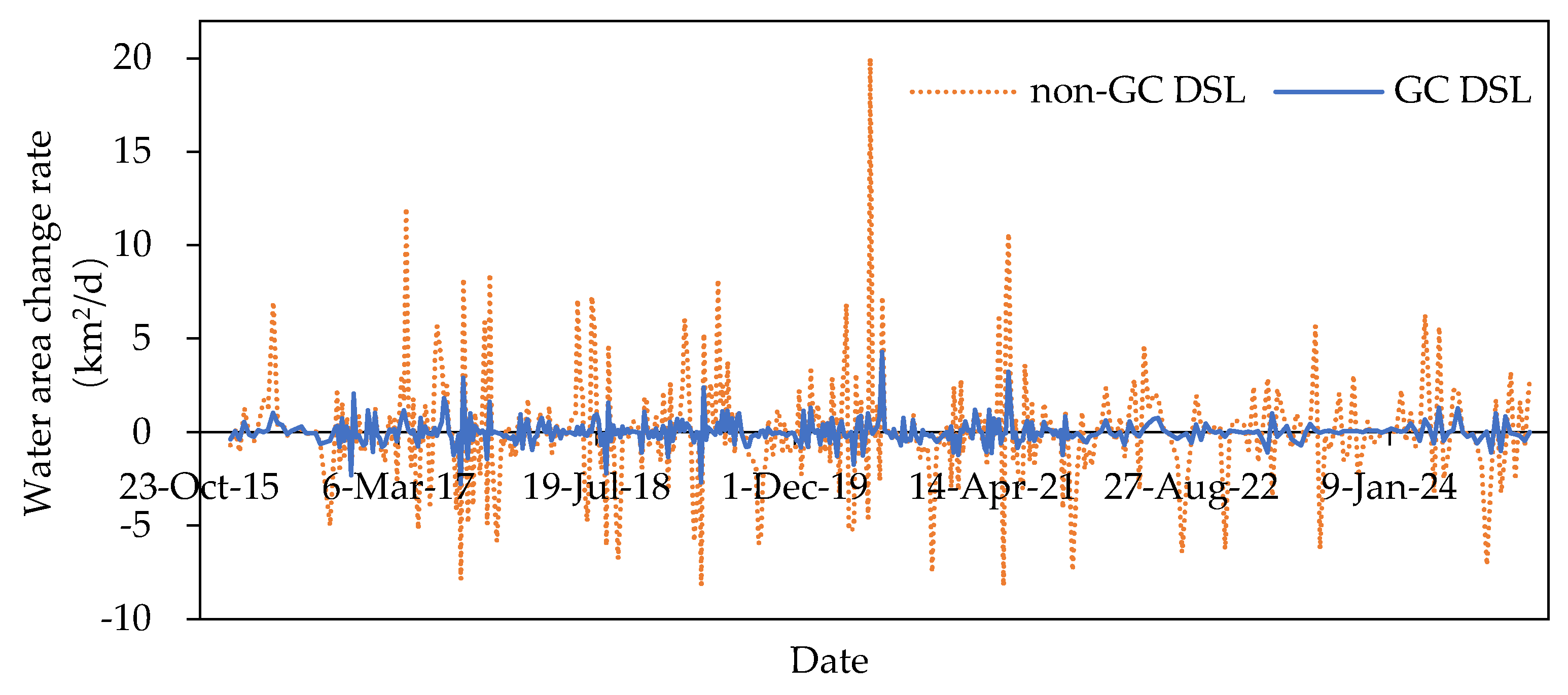

3.3.2. Evolution Trend of the Rate of Change in the Inundation Area of Water Bodies

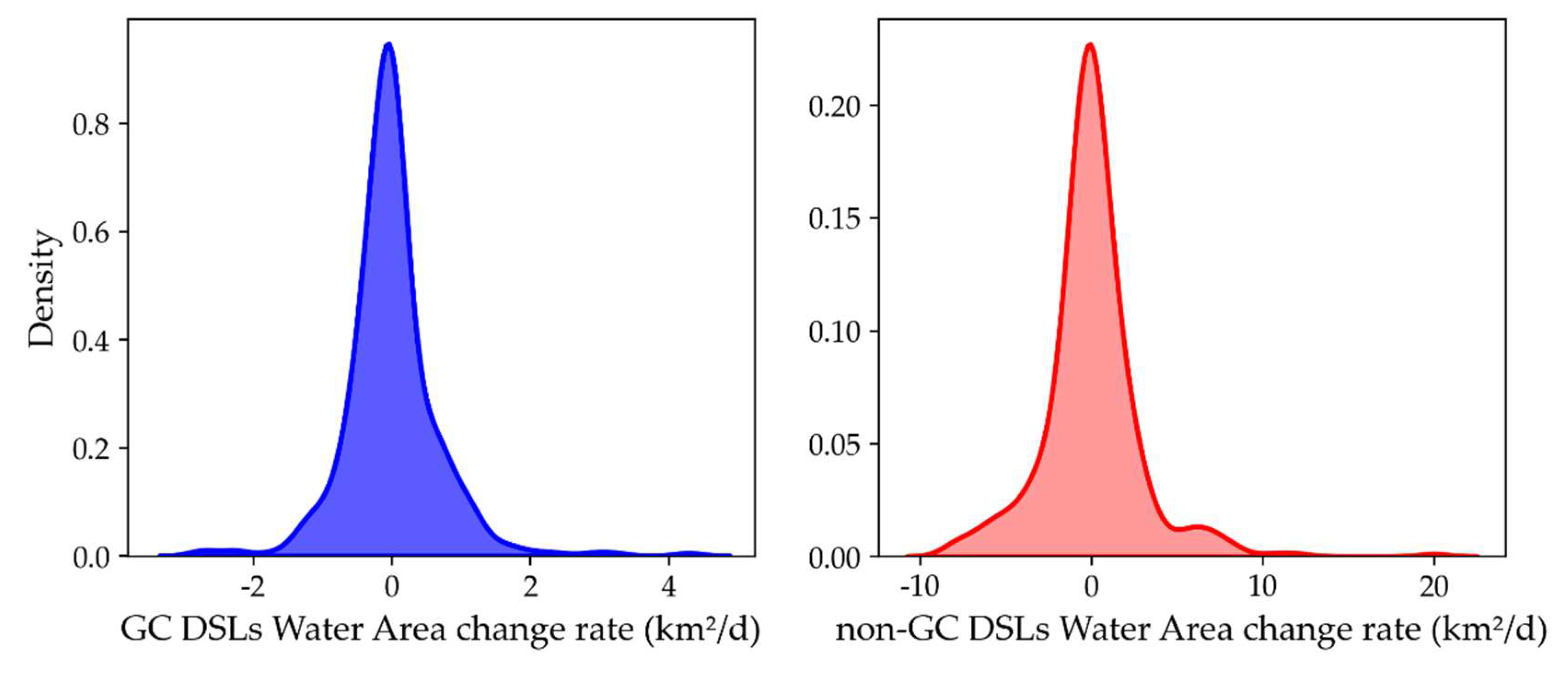

From 2016 to 2024, non-GC DSLs exhibited a mean area increase rate of 1.87 km²/d and a mean area decrease rate of 1.70 km²/d. Their maximum increase and decrease rates were 20.01 km²/d (on 8 June 2020, during the extreme flood) and 8.23 km²/d, with coefficients of variation of 1.32 for increases and 1.09 for decreases. In contrast, GC DSLs showed a mean area increase rate of 0.48 km²/d and a mean area decrease rate of 0.38 km²/d; their maximum increase and decrease rates were 4.29 km²/d and 2.76 km²/d, respectively, with coefficients of variation of 1.22 for increases and 1.14 for decreases. Thus, both the long-term mean rates and the extreme rates of area change in GC DSLs were substantially lower than those in non-GC DSLs.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the rate of change in submerged area between GC DSLs and non-GC DSLs from 2016 to 2024.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the rate of change in submerged area between GC DSLs and non-GC DSLs from 2016 to 2024.

Kernel-density estimation of the submerged area change rate distributions revealed a skewness of 1.13 for non-GC DSLs, indicating a positively skewed distribution with some large positive change-rate outliers driven by extreme flood years (e.g., 1998 and 2020). GC DSLs had a lower skewness of 0.90, indicating fewer extreme change-rate values and a more symmetric distribution. This reduction in skewness reflects the stabilizing effect of hydraulic structures on lake-area dynamics.

Figure 13.

Density distribution of the rate of change in submerged area of GC DSLs and non-GC DSLs from 2016 to 2024.

Figure 13.

Density distribution of the rate of change in submerged area of GC DSLs and non-GC DSLs from 2016 to 2024.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impacts of Hydrological Regime Change on DSLs Habitats

Analysis of daily water level records at Xingzi Station from 1956 to 2022 reveals a long-term decline in the mean water levels of the DSL region, with a mean monthly decline of 0.84 m since 2003. This persistent decrease not only reflects climatic influences on basin hydrology but also highlights the effects of regional water-resource development on downstream flow regimes, thereby altering the DSL’s hydroperiod [

47,

48]. Peak water level reductions exceeded 2.5 m in January, March, and September, demonstrating pronounced temporal heterogeneity that may affect aquatic species distributions, wetland vegetation patterns, and habitat connectivity.

The shift in the duration of inundation from the 10.0–14.0 m band to the 6.0–10.0 m band suggests a transformation of the wetland’s inundation–exposure cycle, with potential consequences for community structure, interspecific competition, and wetland functioning [

49,

50,

51]. December 2024 UAV surveys captured clear zonation extending from shore to lake center (

Figure 14): submerged vegetation (e.g., Vallisneria spp., Waterthymes) at low elevations; floating-leaved vegetation (e.g., Trapa bispinosa Roxb., Nymphoides); hygrophilous vegetation (e.g., Polygonum, Phalaris arundinacea, Carex spp.); and emergent stands (e.g., Phragmites australis) at high elevations. As the duration of low water stages lengthens, emergent and hygrophilous vegetation encroach on lower-elevation zones, displacing former floating-leaf and submerged communities—a pattern confirmed by the 2022 drought, which saw extensive conversion of Polygonum-Phalaris arundinacea flats into higher-elevation Carex spp. and Phragmites australis. The pronounced September water level decline may further influence habitat availability for incoming wintering waterbirds.

Alongside changes in the hydrological regime, the annual mean FVC of the DSLs exhibited interannual fluctuations around an overall increase from 2001 to 2024—rising in GC DSLs and remaining relatively stable in non-GC DSLs. This pattern is primarily driven by declining water levels and prolonged low-water stages, which transform former mud-flats into suitable habitats for emergent and hygrophilous vegetation, thereby increasing both mean FVC and biomass (

Figure 15).

Analysis of habitat succession before and after extreme events (the 1998 and 2020 floods and the 2022 drought) demonstrates that such events exert pronounced disturbances on the wetland ecosystem. During floods, mudflat area expanded markedly and submerged vegetation experienced collapse, virtually disappearing in 1999 and 2021, while other plant communities (e.g., Carex spp., Polygonum, Phalaris arundinacea, Phragmites australis) exhibited varying degrees of expansion or replacement. These responses indicate that extreme floods, through hydraulic scouring, prolonged inundation and sediment redistribution, disrupt pre-existing vegetation stability and drive dynamic succession within sensitive wetland zones [

52,

53].

In contrast, drought events produced opposite effects: some submerged vegetation partially recovered under low-water conditions, likely due to increased water transparency, thereby enhancing photosynthesis and activating the submerged seed bank [

54,

55,

56]. Although this recovery demonstrates ecosystem resilience, it also suggests that frequent extreme droughts may induce long-term shifts in plant community structure, with potential consequences for wetland functions and biodiversity. The patterns observed in Poyang Lake DSLs mirror global trends of wetland degradation under altered hydrological regimes driven by climate change and human activities [

57,

58,

59], underscoring the critical role of hydrology in wetland habitat evolution.

4.2. Impact of Artificial Regulation on the Habitat of DSLs

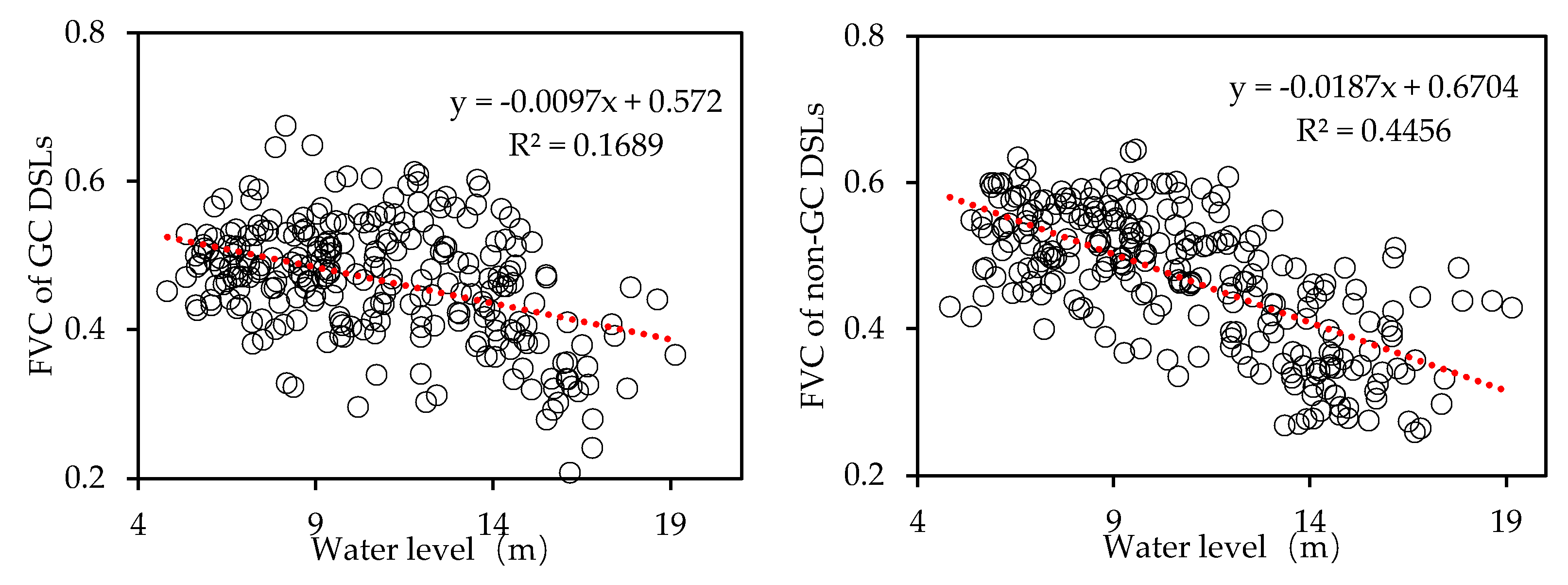

By integrating water level records from Xingzi Station, DSL FVC measurements, and hydraulic-control classifications, we found that GC DSLs exhibit a lower annual mean FVC in high water level years, whereas in low water level years their FVC is significantly higher than that of non-GC DSLs (

Table 2). Non-GC DSLs experience rapid post-flood water area recession (−1.296 km²/d), exposing mudflats that are quickly colonized by emergent wetland vegetation. In contrast, hydraulic structures in GC DSLs, namely embankments and sluice gates, prolong high-water conditions, resulting in a much slower water-area decline (−0.312 km²/d). Consequently, mudflat exposure is limited, and overall vegetation cover and biomass remain lower than in non-GC DSLs. During low water level years, marked by an earlier onset and prolonged dry season at Poyang Lake and relatively lower wet-season water levels, non-GC DSLs undergo intensified drought stress. GC DSLs buffer these hydrological fluctuations, maintaining a mean water area of 23.70 ± 5.28 km² during the 2022 non-flood season, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of extreme drought on vegetation. Consequently, in low water level years GC DSLs exhibit an 8.9% higher annual mean FVC than non-GC DSLs.

Correlation analysis between Xingzi Station water levels and DSL FVC (

Figure 16) shows that non-GC DSLs have a strong negative correlation (Pearson’s r = −0.7072, R² = 0.4456), whereas GC DSLs show a weaker negative correlation (r = −0.4383, R² = 0.1689). This contrast further indicates that hydraulic regulation attenuates the influence of water level fluctuations on DSL habitat evolution.

Table 3 summarizes water area statistics (2016–2024) for four representative DSLs: three GC DSLs (Dahuchi Lake, Shahu Lake, Changhuchi Lake) and one non-GC DSLs (Banghu Lake). Banghu Lake exhibits a coefficient of variation (CV) of 0.72—nearly twice those of the GC DSLs—indicating large intra-annual area fluctuations, whereas GC DSLs show relatively minor variability.

We selected four representative habitats in DSLs and assessed their area coverage before and after the 2020 extreme flood and the 2022 extreme drought. In Banghu Lake, emergent and hygrophilous wetland vegetation covered 69.57% of the lake area in 2019, declined to 63.88% after the 2020 flood, and then increased to 72.50% in 2023 following the 2022 drought. In contrast, GC DSLs, including Dahuchi Lake, Shahu Lake, and Changhuchi Lake, showed different trends. After the 2020 flood, emergent and hygrophilous cover in these lakes increased by 8.93%, 5.16%, and 30.14%, respectively. Following the 2022 drought, Dahuchi Lake and Shahu Lake continued to gain vegetation cover, whereas Changhuchi Lake’s cover declined to 34.32%, remaining nonetheless above its pre-event level. Variations in vegetation response among GC DSLs may result from differences in hydraulic regulation strategies, local topography, and vegetation characteristics across lakes [

60].

4.3. Impact of Habitat Evolution of DSLs on Overwintering Migratory Birds

Poyang Lake serves as a critical wintering ground along the East Asian–Australasian Flyway, attracting numerous migratory birds each year. The survival of these birds depends on the stability of the wetland ecosystem and the availability of food resources, both of which are shaped by changes in the hydrological regime, vegetation succession, and hydraulic regulation in the DSLs complex of Poyang Lake [

61].

Hydrological requirements of wintering birds vary among functional groups. Waders (e.g. the indicator species Siberian Crane) prefer foraging in shallow water depths of 15–20 cm, whereas waterfowl (e.g. ducks and geese) forage and rest in deeper waters [

33,

62]. Since 2003, Poyang Lake’s water levels have declined overall, especially during the autumn–winter period (September to November), when maximum levels in September fell by as much as 2.53 m. Such declines may reduce shallow-water foraging habitat for wintering waders. In contrast, longer durations at low water levels (e.g. more days in the 6.0–10.0 m range) expand mudflat and shoal habitats, temporarily increasing habitat for waders. However, excessively low levels can reduce water connectivity and constrain waterfowl movements. Extreme events amplify these effects. The 1998 and 2020 floods caused rapid water level rises that inundated mudflats and shoals, reducing wader foraging grounds, while the 2022 drought drove levels to historic lows and sharply contracted water bodies, likely forcing waterfowl into limited refugia and intensifying intra- and interspecific competition.

Wetland vegetation succession directly influences food availability. Submerged macrophytes, such as Vallisneria spp. tubers, constitute a key food source for waders including the Siberian Crane, whereas emergent vegetation, notably Carex spp., provides nutrition for waterfowl (ducks and geese). Floods frequently induce catastrophic loss of submerged vegetation (e.g. Poyang Lake in 1999 and 2021), leading to food shortages that may force cranes to forage in alternative habitats such as adjacent rice paddies or lotus ponds [

63]. Although submerged macrophytes showed partial recovery after the 2022 drought (e.g. in 2023), the magnitude and pace of recovery may remain insufficient to satisfy the nutritional demands of migratory birds. Declining water levels promote downslope expansion of emergent vegetation. Carex spp. in particular expand on newly exposed mudflats, potentially enhancing food resources for waterfowl.

Hydraulic regulation through GC DSLs buffers the impacts of extreme hydrological events. In drought years (e.g. 2022), hydraulic regulation maintained larger water areas and a mean FVC of 0.477 compared to 0.443 in non-GC DSLs, thereby providing more stable habitat and food supplies. However, sustaining elevated water levels after flood events can delay mudflat exposure, thereby hindering wader foraging activity. Moreover, prolonged deviation from natural hydrological regimes may disrupt habitat utilization and adaptive behaviors of migratory birds, warranting further investigation of these cumulative effects.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the long-term hydrological observations, multi-source remote sensing data, and field survey records were integrated to analyze habitat succession in the ecologically sensitive DSLs of Poyang Lake. We systematically revealed the mechanisms by which altered hydrological regimes combined with extreme flood and drought events affect wetland ecosystems; and clarified the role of hydraulic regulation in mitigating them. The principal conclusions are as follows:

From 1956 to 2022, daily water-level records at Xingzi Station exhibited a pronounced downward trend. Between 2003 and 2022, the monthly mean water level declined by 0.84 m relative to 1956–2002, and peak levels in January, March, and September each fell by over 2.5 m. The hydroperiod shifted from the 10.0–14.0 m elevation band to the 6.0–10.0 m band, indicating a substantial alteration of the basin’s hydrological rhythm. Extreme hydrological events, including the 1998 and 2020 floods and the 2022 drought, triggered dramatic vegetation succession on exposed shoals through enhanced scouring, prolonged inundation, sediment redistribution, and increased water transparency. Floods caused collapse of submerged vegetation in 1999 and 2021, and expanded mudflat area by 32.27 % in 1998 and by 17.66 % in 2020. In contrast, drought conditions, characterized by lower water levels and increased water clarity, promoted photosynthesis and seed-bank activation, enabling partial recovery of submerged vegetation. Declining water levels also facilitated downslope expansion of emergent and hygrophilous vegetation.

Hydraulic regulation through GC DSLs mitigated the impacts of these extreme events. Compared with non-GC DSLs, GC DSLs exhibited a lower coefficient of variation in water area and higher FVC during low-water years. By prolonging the recession phase, with a mean area-decrease rate of –0.312 km²/d, hydraulic control maintained higher autumn water areas. This regulation suppressed downward expansion of emergent and hygrophilous vegetation, resulting in GC DSLs having FVC values 0.030–0.093 lower than non-GC DSLs during high-water years. Correlation analyses between Xingzi water levels and FVC across regulation types confirm that hydraulic control significantly influences habitat dynamics. Divergent vegetation responses among GC DSLs were observed, with Dahuchi Lake and Shahu Lake showing continued growth and Changhuchi Lake showing a decline after the 2022 drought. These differences likely reflect variation in hydraulic regulation strategies, local topography, and vegetation traits.

Declining wetland water levels have restructured plant communities along elevation gradients, as emergent and hygrophilous species moved downslope to occupy formerly submerged habitats, converting 25.38 km² of mudflat into emergent vegetation in 2023. This habitat heterogeneity differentially affects wintering waterbirds. Reduced shallow-water (< 30 cm) areas threaten waders such as the Siberian Crane that depend on submerged macrophytes for foraging, whereas expansion of emergent Carex spp. beds enhances feeding opportunities for waterfowl (ducks and geese). Extreme events that disrupt natural hydrological regimes, such as the 1998 and 2020 floods and the 2022 drought, cause catastrophic loss of submerged vegetation and pronounced succession of emergent and hygrophilous species, forcing waders to relocate or forage in artificial wetlands such as rice paddies and lotus ponds. Although hydraulic regulation through GC DSL maintained water area at 23.70 ± 5.28 km² during the 2022 non-flood season—thereby buffering habitat and food-resource instability—such intervention may alter long-term bird–habitat adaptation by deviating from natural hydroperiods.

Based on these findings, dynamic wetland water level regulation thresholds should be established to balance submerged-vegetation recovery with emergent-vegetation expansion, thereby enhancing overall biomass and meeting the foraging needs of overwintering migratory birds. Spatially differentiated gate-operation strategies ought to be optimized by developing tiered management schemes tailored to each DSL’s distinct ecological functions, so as to maintain habitat heterogeneity and resource availability for different bird guilds. An extreme-events early-warning and response mechanism should be constructed, integrating hydrological forecasting with seed-bank conservation and targeted vegetation restoration to bolster system resilience under superimposed extreme events. Finally, future research needs to develop coupled water level–vegetation–migratory-bird models for wetland ecosystems to quantify the long-term cumulative effects of anthropogenic water level regulation on biodiversity, thereby providing the theoretical foundation for adaptive wetland management under evolving river–lake connectivity regimes and extreme hydrological events.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2023YFC3209001).

References

- Guo, M.; Yu, D. K.; Li, Z.; et al. The Impact of Extreme Droughts on Aquatic Macrophyte Communities in the Sub-lakes of Poyang Lake. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2024, 40, 790–798. (In Chinese).

- Niu, H.L.; Wang, M.X.; Shi, Y.B.; et al. Numbers, Spatial Distribution and Characteristics of Saucer-Shaped Lakes in Lake Poyang Wetland and Influencing Factors. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2025, 37, 000–000. (In Chinese).

- Wei, Z.; Xu, Z.; Dong, B.; et al. Habitat Suitability Evaluation and Ecological Corridor Construction of Wintering Cranes in Poyang Lake. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 189, 106894. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.J.; Hu, X.R.; Nie, X.; et al. Seasonal and Inter-Annual Community Structure Characteristics of Zooplankton Driven by Water Environment Factors in a Sub-lake of Lake Poyang, China. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7590. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, H.; Li, X.C.; et al. Geographic Pattern of Phytoplankton Community and Their Drivers in Lakes of Middle and Lower Reaches of Yangtze River Floodplain, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 83993–84005. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qian, K.M.; Chen, Y.W.; et al. A Comparison of Factors Influencing the Summer Phytoplankton Biomass in China’s Three Largest Freshwater Lakes: Poyang, Dongting, and Taihu. Hydrobiologia 2017, 792, 283–302.

- Liu, Y.B.; Wu, G.P. Hydroclimatological Influences on Recently Increased Droughts in China’s Largest Freshwater Lake. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 93–107. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Vegetation Dynamics under Water-Level Fluctuations: Implications for Wetland Restoration. J. Hydrol. 2020, 581, 124418. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, S.Y.; et al. Research Progress of Numerical Simulation of Wetland Plant Ecology and Research Example of Poyang Lake Wetland. J. China Inst. Water Resour. Hydropower Res. 2022, 22, 539–557. (In Chinese).

- Shao, M.Q.; Jiang, J.H.; Hong, G.X.; et al. Abundance, Distribution and Diversity Variations of Wintering Water Birds in Poyang Lake, Jiangxi Province, China. Pakistan J. Zool. 2014, 46, 451–462.

- Wang, Y.F.; Chen, Q.; Li, L.; et al. The Cascading Effects of Submerged Macrophyte Collapse on Geese at Poyang Lake, China. Freshwater Biol. 2023, 68, 926–939.

- Li, Y.K.; Zhong, Y.F.; Shao, R.Q.; et al. Modified Hydrological Regime from the Three Gorges Dam Increases the Risk of Food Shortages for Wintering Waterbirds in Poyang Lake. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 24, e01286. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, G.; Wan, R.; et al. Impacts of Hydrological Alteration on Ecosystem Services Changes of a Large River-Connected Lake (Poyang Lake), China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 310, 114750. [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.; Li, B.; Yao, J.; et al. Monitoring the Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of the Wetland Vegetation in Poyang Lake by Landsat and MODIS Observations. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 725, 138096. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wan, R.; Yang, G.; et al. Impact of Seasonal Water-Level Fluctuations on Autumn Vegetation in Poyang Lake Wetland, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 13, 398–409. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Jiang, J. Spatial–Temporal Dynamics of Wetland Vegetation Related to Water Level Fluctuations in Poyang Lake, China. Water 2016, 8, 397.

- Ren, Q.; Yuan, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Water Level Has Higher Influence on Soil Organic Carbon and Microbial Community in Poyang Lake Wetland than Vegetation Type. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 131. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Yuan, J.; Hou, Z.; et al. Seasonal Water Level Changes Affect Plant Diversity and Littoral Widths at Different Elevation Zones in the Erhai Lake. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1503627. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Liu, X.; Tian, L.; et al. Vegetation and Carbon Sink Response to Water Level Changes in a Seasonal Lake Wetland. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1445906. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Mao, D.; Zhang, D.; et al. Mapping Phragmites australis Aboveground Biomass in the Momoge Wetland Ramsar Site Based on Sentinel-1/2 Images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 694.

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, W.; et al. Impact of Hydrological Changes on Wetland Landscape Dynamics and Implications for Ecohydrological Restoration in Honghe National Nature Reserve, Northeast China. Water 2023, 15, 3350. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Li, X.; Tan, Z.; Song, Y.; et al. Dynamic Characteristics of Vegetation Communities in the Floodplain Wetland of Lake Poyang Based on Spatio-Temporal Fusion of Remote Sensing Data. J. Lake Sci. 2023, 35, 1234–1245. (In Chinese).

- Wang, X.; Guo, Y. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Water Area Variability in Poyang Lake (2012–2021) Using Remote Sensing. J. Comput. Methods Sci. Eng. 2024, 14727978241299700.

- Xia, Y.; Fang, C.; Lin, H.; et al. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Wetland Eco-Hydrological Connectivity in the Poyang Lake Area Based on Long Time-Series Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4812. [CrossRef]

- Larson, D.M.; Cordts, S.D.; Hansel-Welch, N. Shallow Lake Management Enhanced Habitat and Attracted Waterbirds during Fall Migration. Hydrobiologia. 2020, 847, 3365–3379. [CrossRef]

- Aharon-Rotman, Y.; McEvoy, J.; Zhaoju, Z.; et al. Water Level Affects Availability of Optimal Feeding Habitats for Threatened Migratory Waterbirds. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 10440–10450. [CrossRef]

- Holm, T.E.; Clausen, P. Effects of Water Level Management on Autumn Staging Waterbird and Macrophyte Diversity in Three Danish Coastal Lagoons. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 4399–4423. [CrossRef]

- Rajpar, M.N.; Zakaria, M. Effects of Water Level Fluctuation on Waterbirds Distribution and Aquatic Vegetation Composition at Natural Wetland Reserve, Peninsular Malaysia. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2011, 2011, 324038. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Lv, M.; Jiang, H.; et al. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Aquatic Vegetation in Taihu Lake over the Past 30 Years. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66365. [CrossRef]

- Aharon-Rotman, Y.; McEvoy, J.; Zhaoju, Z.; et al. Water Level Affects Availability of Optimal Feeding Habitats for Threatened Migratory Waterbirds. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 10440–10450. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, X.; Hu, C. The Impact of Ecological Water Level on Wintering Migratory Birds in Poyang Lake–Focusing on Phytophagous Geese. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112946. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, B.; Qi, S.; et al. The Influence of Short-Term Water Level Fluctuations on the Habitat Response and Ecological Fragility of Siberian Cranes in Poyang Lake, China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4431. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Pan, Y.; Yu, X.; et al. Effects of Habitat Change on the Wintering Waterbird Community in China’s Largest Freshwater Lake. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4582. [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zhai, J.; Huang, Z.; et al. The Impact of Poyang Lake Water Level Changes on the Landscape Pattern of Wintering Wading Bird Habitats. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 58, e03453. [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Wu, G.; Zhao, X.S.; et al. Responses of Wetland Vegetation to Droughts and Its Impact Factors in Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve. J. Lake Sci. 2014, 26, 253–259.

- Sun, F.D.; Ma, R. Hydrologic Changes of Poyang Lake Based on Radar Altimeter and Optical Sensor. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 75, 544–557.

- Li, B.; Zhang, A.Z.; Sun, G.Y.; et al. Extraction of Typical Vegetation Communities in Poyang Lake Wetland Based on Time Series Sentinel-2 Images. Remote Sens. Technol. Appl. 2024, 39, 1271–1283. (In Chinese).

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32.

- Gutman, G.; Ignatov, A. The Derivation of the Green Vegetation Fraction from NOAA/AVHRR Data for Use in Numerical Weather Prediction Models. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1998, 19, 1533–1543. [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Xue, D.; Li, C.; et al. Study on New Method for Water Area Information Extraction Based on Sentinel-1 Data. Yangtze River 2019, 50, 213–217. (In Chinese).

- Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Manlike, A.; et al. Comparative Study of Remote Sensing Estimation Methods for Grassland Fractional Vegetation Coverage–A Grassland Case Study Performed in Ili Prefecture, Xinjiang, China. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 2243–2258. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, H.; Fu, Y.; et al. Fractional Vegetation Cover Estimation of Different Vegetation Types in the Qaidam Basin. Sustainability 2019, 11, 864. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; et al. Global Dynamics of Grassland FVC and LST and Spatial Distribution of Their Correlation (2001–2022). Plants 2025, 14, 439. [CrossRef]

- Cunnick, H.; Ramage, J.M.; Magness, D.; et al. Mapping Fractional Vegetation Coverage across Wetland Classes of Sub-Arctic Peatlands Using Combined Partial Least Squares Regression and Multiple Endmember Spectral Unmixing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1440. [CrossRef]

- Ganju, N.K.; Couvillion, B.R.; Defne, Z.; et al. Development and Application of Landsat-Based Wetland Vegetation Cover and Unvegetated-Vegetated Marsh Ratio (UVVR) for the Conterminous United States. Estuaries Coasts 2022, 45, 1861–1878. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.P.; Zhao, C.Z.; Li, X.Y.; et al. Temporal and Spatial Characteristics of Vegetation Coverage and Their Influencing Factors in the Sugan Lake Wetland on the Northern Margin of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1097817. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Factors Influencing Water Level Changes in China’s Largest Freshwater Lake, Poyang Lake, in the Past 50 Years. Water Int. 2014, 39, 983–999.

- Xue, C.; Zhang, Q.; Jia, Y.; et al. Intensifying Drought of Poyang Lake and Potential Recovery Approaches in the Dammed Middle Yangtze River Catchment. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 50, 101548. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; et al. Diazotrophic Community in the Sediments of Poyang Lake in Response to Water Level Fluctuations. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1324313. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Interactive Effects of Flooding Duration and Sediment Texture on the Growth and Adaptation of Three Plant Species in the Poyang Lake Wetland. Biology 2023, 12, 944.

- Lai, X.; Zeng, H.; Zhao, X.; et al. Impact of Extreme Drought on Vegetation Greenness in Poyang Lake Wetland. Forests 2024, 15, 1756. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Ren, J.; Wu, C.; et al. Extreme Precipitation Events Trigger Abrupt Vegetation Succession in Emerging Coastal Wetlands. Catena 2024, 241, 108066. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Interactive Effects of Flooding Duration and Sediment Texture on the Growth and Adaptation of Three Plant Species in the Poyang Lake Wetland. Biology 2023, 12, 944.

- He, S.; Xu, J.; Yi, Y.; et al. Variations in Aquatic Vegetation Diversity Responses to Water Level Sequences during Drought in Lakes under Uncertain Conditions. Water 2023, 15, 2395. [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Ma, Z.; Du, G. Effects of Water Level on Three Wetlands Soil Seed Banks on the Tibetan Plateau. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101458. [CrossRef]

- Byrd, K.B.; Lorenz, A.A.; Anderson, J.A.; et al. Quantifying Drought’s Influence on Moist Soil Seed Vegetation in California’s Central Valley through Remote Sensing. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02153. [CrossRef]

- Long, K.E.; Schneider, L.; Connor, S.E.; et al. Human Impacts and Anthropocene Environmental Change at Lake Kutubu, a Ramsar Wetland in Papua New Guinea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022216118. [CrossRef]

- Loiselle, A.; Proulx, R.; Larocque, M.; et al. Resilience of Lake-Edge Wetlands to Water Level Changes in a Southern Boreal Lake. Wetlands Ecol. Manag. 2021, 29, 867–88. [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Singha, P. Linking River Flow Modification with Wetland Hydrological Instability, Habitat Condition, and Ecological Responses. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 11634–11660. [CrossRef]

- Meeker, J.E.; Wilcox, D.A.; Harris, A.G. Changes in Wetland Vegetation in Regulated Lakes in Northern Minnesota, USA Ten Years after a New Regulation Plan Was Implemented. Wetlands 2018, 38, 437–449. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Pan, Y.; Yu, X.; et al. Effects of Habitat Change on the Wintering Waterbird Community in China’s Largest Freshwater Lake. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4582. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.D.; Li, F.S. Study on the Relationship Between the Behavioral Choices of Wintering Waterbirds and Water Level as Well as Food Availability. In Annual Monitoring Report of Natural Resources of Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve in 2010; Zhu, Q.; Liu G.H.; Wu, J.D.; Fudan University Press: Shanghai, China, 2011; pp. 100–109.Jiangxi Poyang Lake National Reserve. Natural Resources Monitoring Report 2010.

- Ding, H.F.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.F.; et al. Interspecific Relationships between Tundra Swans Cygnus columbianus and Siberian Cranes Leucogeranus leucogeranus in the Lotus Ponds Reclamation Area around Poyang Lake. Chin. J. Zool. 2024, 59, 161–171. (In Chinese).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).