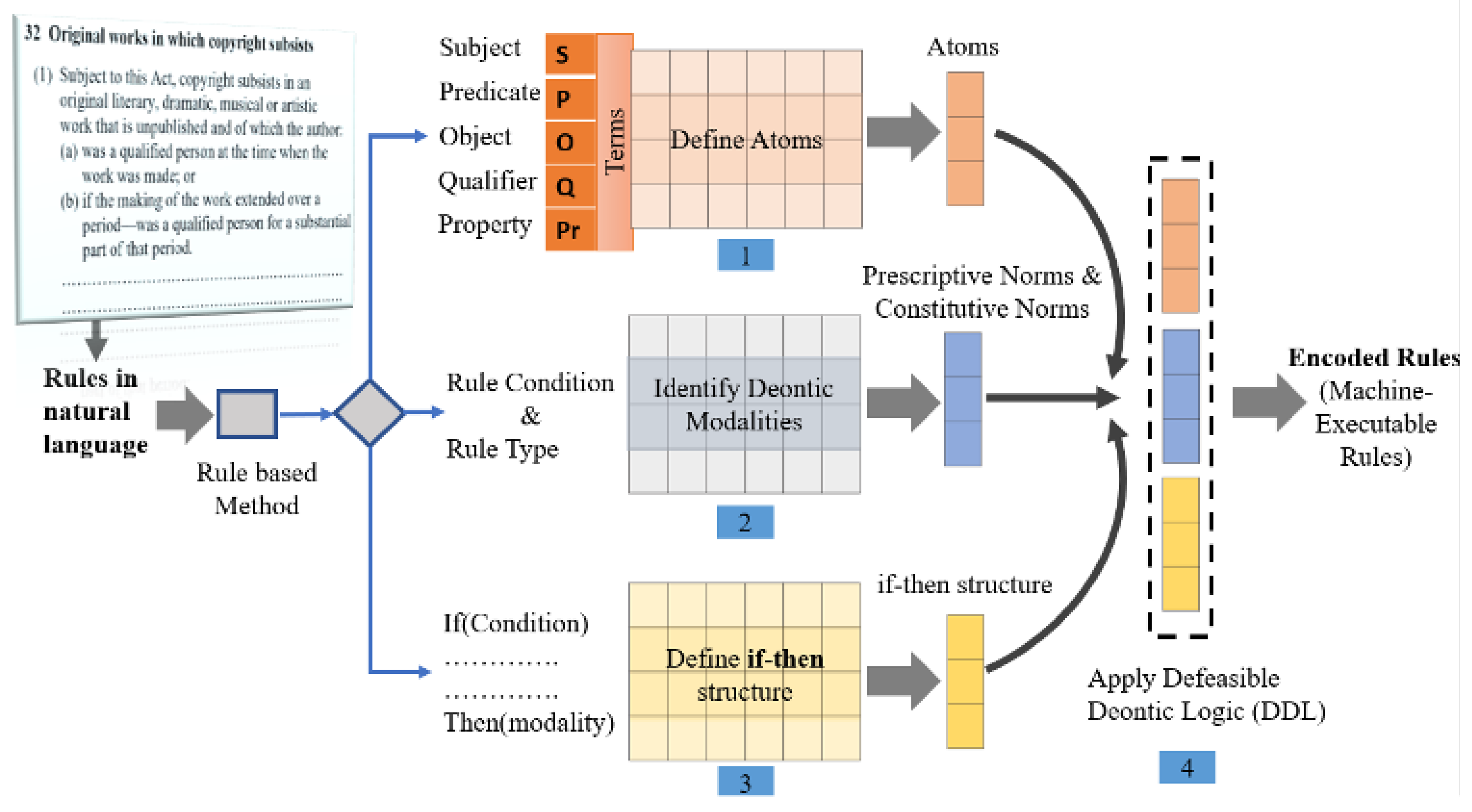

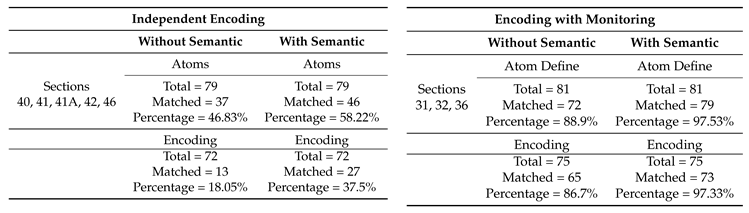

We introduce a Defeasible Deontic Logic (DDL) based encoding methodology to convert copyright rules into the machine-executable format.

These steps are done manually. The methodology’s input is a set of copyright rules in natural language. In the first step, atoms are defined by the rules. In the second step, norms are determined. Then, the if-then structure is identified from the rules in the third and final step. Finally, DDL is applied to the atoms, deontic modalities, and the if-then structure to make the machine-executable (M/E) rules format. The steps are explained below.

2.1. Define Atoms

This section briefly outlines how atoms are defined by rules. An atom is a predicate symbol including constants or variables that contain no logical connectives [

6]. Here, the atoms are extracted based on the occurrences of terms/expressions in the sentences or the textual provision of the rules. A

term is a

variable or an (individual)

constant in the textual provision [

7]. This work deals with expressions (predicates, variables, and constants) that refer to subject (s), predicate (p), property (pr), object (o), and qualifier (q) in a rule sentence.

In natural language, a subject (or entity) refers to the term about which something is said in the sentence. The something which is said about something is the predicate of the sentence. The predicate of a subject-predicate sentence indicates a relation or a property. The object is what the subject does something to. In other words, the object is the result of the action. Qualifiers are terms that usually enhance or limit another word’s meaning. Qualifiers can refer to either the subject, the predicate, or any of the objects in a sentence.

Before generating terms, some article pre-processing is done on the text. For example, verbs (auxiliary, principal, modal, etc.) are not considered terms. In logic, subjects and objects are variable or constant in the rule sentence correspondence to the entity [

7]. A predicate is a constant in the rule sentence that always refers to the properties or actions of entities. Properties indicate the relationship between a subject and a predicate. Object refers to the properties of the entities. Qualifiers refer to the variables that enhance or limit entities.

An atom is a combination of these terms/expressions that form a (primitive) Boolean expression. For example, “Copyright subsists in a work”. According to the linguistic perspective, the term “copyright” is the subject of the sentence. The term “work” is the object of the sentence as the subject is doing something to it. The term “subsists (in)” is the predicate of the sentence as it expresses the relation between the subject (copyright) and the object (work). In logical terms, the sentence can be rendered as a binary predicate with the form

hence, for the specific sentence we have

Consider now the sentence “copyright is the exclusive right to reproduce the work in material form”. In this more complex expression, the subject is still “copyright”, and “(is the) exclusive right” is a property of the subject. The predicate is “reproduce”, the object is “work”. The term “material form” is the qualifier of the sentence, as this enhances the subject meaning through the object. In the logical approach, “copyright” is that variable that refers to the entity (subject) of the sentence. “reproduce” is the predicate constant that refers to the action of the entity. “work” is an (individual) constant of the sentence which is referring to the properties of the entity. “material” is the variable (qualifier) which is referring to the enhancement of the entity. To convert the sentence to its logical form, some further analysis is needed. Specifically, we have to fill some gaps. Who has the exclusive right, and who is going to perform the act covered by copyright? Hence, we can rephrase the sentence as “the copyright owner has the exclusive right to reproduce the work in material form”. Thus, we have

- (1)

“copyright subsists in the work”;

- (2)

“a person owns the copyright on the work”;

- (3)

“the person is permitted to reproduce the work in material form” or “it is permitted that the person reproduces the work in material form”;

- (4)

“no body else is permitted to reproduce the work in material form”.

When we examine the sentences in 3 we notice that there is a modal (permitted), and the Boolean sentence “the person reproduces the work in material form” is in the scope of the deontic operator. When we analyse the sentence, logically, it can be represented as a predicate in one of the following two forms:

thus, we can model it as either

or

In general, a rule uses natural language to define the cases (events and facts) they are meant to regulate (terms, conditions, and legal provisions). Depending on the events, the description of these cases varies. There is no general structure in how these rules are written. Due to this heterogeneity of the rule information, the atom structure varies. Based on extensive analysis and encoding of various regulations, we noticed that the following five patterns suffice to represent the vast majority of provisions.

S-P-O: Subject-Predicate-Object;

S-P-Q-O: Subject-Predicate-Qualifier-Object;

S-Pr: Subject-Property,

S-P-O-O: Subject-Predicate-Object-Object;

S-Q-P-O: Subject-Qualifier-Predicate-Object.

Based on these combinations, some examples of atoms from the Australian Copyright Act and the patterns used to obtain them are shown below.

For the representation of the atoms, there are some possible conventions. One is to use the convention typically used in logic

Where the arguments are the subject, objects, and qualifiers. This would be the best option for a first-order based formalisation. The second convention is to create atoms by combining the terms in the order in which they appear (this is the favourite option for a propositional based formalisation). We adopted the second option, but we inverted the order for the S-Pr pattern.

Example 1 (S-P-O). Part III, Division 1, 32: “copyright subsists in the work”

| Subject |

Predicate |

Object |

| copyright |

subsist in |

work |

Defined Atom: Copyrigth_Subsist_Work

As we discussed above, this is a simple instance of the Subject-Predicate-Object pattern

Example 2 (S-P-Q-O). Part III, Division 1, 32, 2(d): “the author was a qualified person”.

| Subject |

Predicate |

Qualifier |

Object |

| author |

was |

qualified |

person |

Defined Atom: Author_Was_Qualified_Person

In this case, we recognise that the term “qualified” is the qualifier of the object (“person”).

Example 3 (S-Pr). Part I (Interpretation), 10, “work means literary [...] work”

| Subject |

Property |

| work |

literary |

Defined Atom: Literary_Work.

A property can be seen as a special qualification of a subject, and is often signalled by an auxiliary verb (“be” or “have”), and it corresponds to a unary predicate. In this case, we have the verb “mean”; this can also be understood as “a literary work is a work”.

Notice that the sentence in Example 2 can be analysed as:

| Subject |

Property |

| Author |

Qualified Person |

Defined Atom: Qualified_Person_Author.

Example 4 (S-P-O-O). “a person has authorised the reproduction of a work”

| Subject |

Predicate |

Object |

Object |

| person |

authorise |

reproduction |

work |

Defined Atom: Person_Authorise_Reproduction_Work

With this interpretation, we analysed the sentence with two objects: the first “reproduction” and the second “work”. An alternative reading would be

| Subject |

Predicate |

Qualifier |

Object |

| person |

authorise |

reproduction |

work |

Defined Atom: Person_Authorise_Reproduction_Work

With the alternative parsing the term “reproduction” is taken as the qualifier for the term “work”. However, the two alternative readings produce the same atom.

Example 5 (S-Q-P-O). “the first publication of the work took place in Australia”.

For this sentence, we have two options. The first option is to examine the sentence as it appears. Here, the subject is “first publication”, where “first” is the qualifier of “publication”.

| Subject |

Qualifier |

Predicate |

Object |

| publication |

first |

took place |

Australia |

Defined Atom: First_Publication_TookPlace_Australia

For the second option, we consider the passive form, where the subject is “work”. While semantically the two expressions share the same meaning, the focus in this case is to stress that the publication is a property of a work.

| Subject |

Qualifier |

Predicate |

Object |

| work |

first |

published |

Australia |

Defined Atom: WorK_First_Published_Australia

Based on previous experiments and encodings, we believe that these patterns suffice to cover the majority of cases under any regulation. In some cases, complex sentences can be split using multiple patterns, as we did in the case of the complex sentence “copyright is the exclusive right to reproduce the work in material form”. The proposed methodology aims to improve encoding efforts’ uniformity, consistency and repeatability. [

3] reports very high (syntactic) variability of encoding when a team of coders does them; moreover, they report that adopting a common naming convention and sharing an encoding methodology greatly increases the agreement among the encodings by the different coders. Also, fitting textual provisions in the patterns allows us to identify expressions that could have different syntactic structures but the same semantic meaning; the same atoms will formalise such expressions.

2.2. Identify Deontic Modalities

Deontic modalities are expressions in the rule that (legally) qualify terms and actions. Deontic modalities help us determine the types of norms we are going to encode. Each norm is represented by one or more constitutive or prescriptive rules (see [

8]). Constitutive rules define terms specific to legal documents. Prescriptive rules prescribe the “mode” of the behaviour using deontic modalities: obligation, permission, and prohibition. Here, we follow the definition given by LegalRuleML for obligation, prohibition, and permission (see [

9]). An obligation is an action or course that the subject must perform or achieve, whereas a prohibition is an action or course that the subject must not perform or avoid. Permission is the state of an action that is not subject to a prohibition, or the opposite is not obligatory.

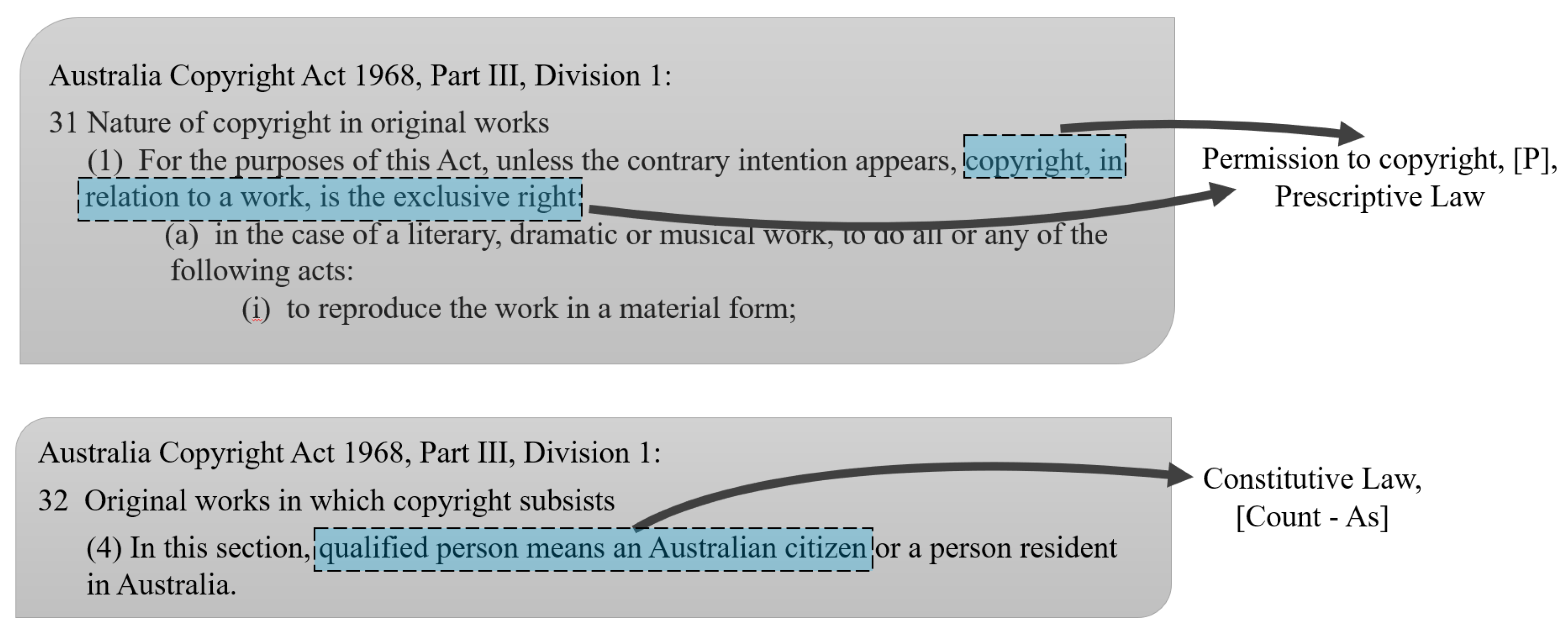

This research identifies norms based on both constitutive and prescriptive forms of rules. For example (

Figure 2), in the Australia Copyright Act 1968, part III, Division 1, 31 (1) states that “copyright, in relation to a work, is the exclusive right to reproduce the work in a material form [...]”. This law gives the permission (right) to the owner of the copyright to reproduce the work (and in general to perform any of the acts described in subsection (a)). Notice that what we call “prescriptive rules” include prescriptive rules in the strict sense (rules establishing an obligation or a prohibition) as well as permissive rules (rules whose effect is a permission). In this case, the modality of the prescriptive rule is “permission”

1; also, in the specific case, the provision specifies that the right is exclusive.

Another example, Australia Copyright Act 1968, part III, Division 1, 32 (4) states that “In this section, qualified person means an Australian Citizen …”. Here, this phrase is meant to define the qualified person, which is a constitutive norm (Count-As) within this statement.

2.3. Define the If-Then Structure

Rules specify the actions of the subject (or the conditions the subject must ensure to hold). They consist of deontic modalities and conditions that control the subject’s behaviour. A rule comprises two parts: if (antecedent or premise) and then (consequent or conclusion). Therefore, a rule can be represented as:

If (antecedent)

Then (consequent)

If the premise becomes true, then the consequent part of the rule triggers. A rule may have multiple antecedents joined by logical operators: OR and AND. From a legal perspective, rules use conditions on some actions to achieve/mandate specific behaviours. Therefore, the if-then structure is identified from rules using atoms and deontic modalities (norms) for encoding. For example, let us consider again the Australia Copyright Act 1968, part III, Division 1, 31. This section recites:

- 31

-

Nature of copyright in original works

- (1)

-

For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a work, is the exclusive right:

- (a)

-

in the case of a literary, dramatic or musical work, to do all or any of the following acts:

- (i)

to reproduce the work in a material form;

The provision contains an explicit permission for the owner of the copyright to do all or any of the acts specified in the rest of the section. At the same time, it forbids the doing to persons who are not the copyright owner. In addition, there is an exception in case the “contrary intention appears”.

r_{31.1.a.i}

IF

AND

Copyright_Subsist_Work

Person_Own_Copyright

OR

Literary_Work

Dramatic_Work

Musical_Work

THEN [P]

Person_Reproduce_Work_MaterialForm

--

r_{31.1.a.i.F}

IF

AND

Copyright_Subsist_Work

NEG Person_Own_Copyright

OR

Literary_Work

Dramatic_Work

Musical_Work

THEN [O]

NEG Person_Reproduce_Work_MaterialForm

--

r_{31.1}

IF

OppositeIntention_Appear_Copyright

THEN (count-as)

NEG Copyright_Subsist_Work

2.4. Rule Encoding

After defining and identifying atoms, deontic modalities, and if-then structures for rules, the expressions are converted into a Defeasible Deontic Logic (DDL) [

10]. DDL is an extension of Defeasible Logic (DL) [

11] with Deontic Operators and compensatory obligation operators introduced [

12]. DDL is a formalism that provides a conceptual approach to encoding the norms and simultaneously exhibits a computationally feasible environment to reason about them. DDL has been successfully used in legal reasoning to handle norms and exceptions, and it does not undergo problems affecting other logics used for reasoning about compliance and norms [

10,

13,

14,

15]. Efficient implementations of the logic have been proposed [

16,

17,

18] that have been used for large scale coding project in various legal domains, including: Australian Spent Conviction [

19], Traffic Rules [

20], Building Code [

21], Consumer Data Right [

5] and more. Below is a brief overview of Defeasible Logic and Deontic modalities.

Defeasible Logic (DL) is a non-monotonic, sceptical logic that prevents the derivation of contradictory conclusions. For example, suppose there is a piece of information that supports the conclusion

A, but there is also a second piece of information that supports not

A, thus preventing the conclusion of

A. DL recognises the opposite conclusions and does not derive them. However, if

A’s support has priority over

, then it might be possible to conclude

A. DDL extends DL with deontic operators (obligation,

and permission

), classifies rules in constitutive rules and prescriptive rules, and introduces the compensation operator of [

12].

Defeasible Deontic Logic comprises five separate knowledge foundations: strict rules, facts, defeasible rules, defeaters (see below), and superiority relations [

10,

11]. Knowledge is organised in theories, where a theory

D is a triple

where

F is a set of facts,

R is a set of rules, and > is a superiority relation in

R.

Expressions in Defeasible Logic are built from a finite set of literals, where a literal can be either an atomic statement or its negation, or a deontic literal. A deontic literal is a literal inside the scope of a deontic operator. Given a literal A, denotes its complement. That is, if , then , and if , then .

Facts (F) are unequivocal and conclusive statements. A fact represents a state of affairs (literal) or an act that has been performed that is believed to be true.

A

rule (an element of

R) specifies the relationship between premises and a conclusion and can be characterised as its strength. Strict rules, defeasible rules, and defeaters can be distinguished based on the relationship strength of the rules [

14]. The following expressions describe these rules:

(Strict Rules),

(Defeasible Rules) and

(Defeaters)

where is the antecedent or premises (clauses), and B is the rule’s consequent or conclusion (effect). Moreover, X denotes the mode of the rule; if , the rule is a constitutive and if or , then the rule is a prescriptive rule. Prescriptive rules include prescriptive rules in the strict sense, where the conclusion of the rule is an obligation, and permissive rules, where the conclusion is a permission.

Strict rules are rules in the classical sense: if the premises are unarguable (for example, a fact), then so is the conclusion. For example, “a literary work is a work”, formally:

This is a strict constitutive rule.

Defeasible rules are rules that can be defeated by contrary evidence. For example, “copyright subsists in a work unless the opposite intention appears” can formally be written as:

Defeaters are rules that cannot be used to derive any conclusions on their own. Their purpose is to preclude some conclusions, i.e., to undermine some defeasible rules by supplying opposite evidence.

Suppose we have two rules for opposite conclusions. In this scenario, we cannot establish any conclusion unless we prioritise the rule. The superiority relation (>) is the DDL mechanism to define the priorities among the rules. For example, based on the following defeasible rules:

No conclusive decision can be made about whether the reproduction infringed the copyright. However, if we establish a superiority relation with , then we can state that the fair use of literary work for the purpose of research is permitted (and hence it is not an infringement on the copyright).

The reasoning mechanism of Defeasible Deontic Logic has a three-step argumentation structure:

- (1)

propose an argument (rule) for the conclusion to prove;

- (2)

identify all possible counter-arguments (rules for the opposite);

- (3)

-

rebut the counter-arguments:

- (a)

undermine the counter-argument (show that some of the premises of the counter-argument do not hold);

- (b)

defeat the counter-argument (show that the counter-argument is weaker than an argument supporting the conclusion).

A complete definition of the defeasible deontic logic reasoning mechanism can be found in [

10,

13,

14,

15].