Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

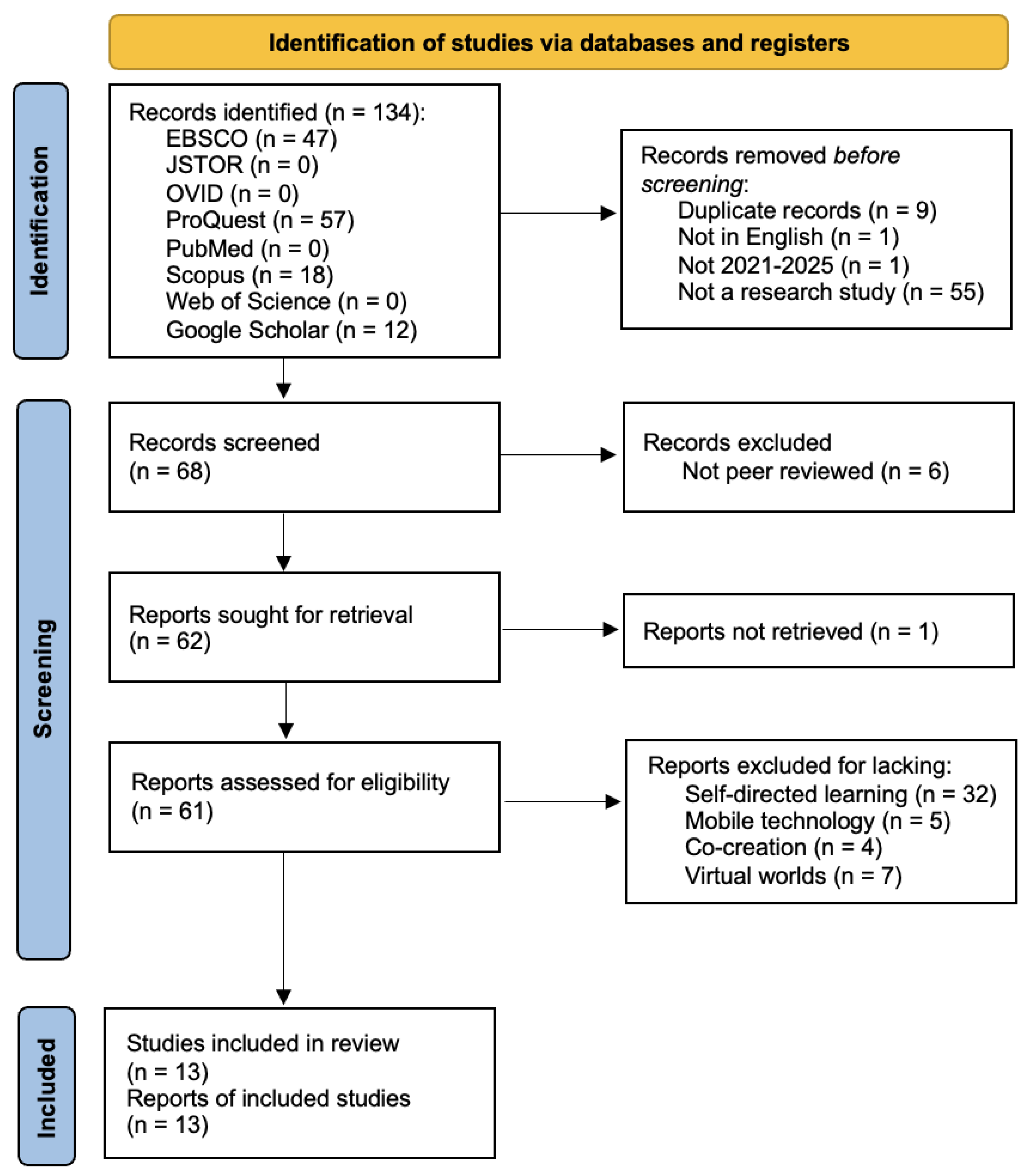

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Reports of Included Studies

| # | Title | Authors | Journal | Year |

| [53] | An empirical study on immersive technology in synchronous hybrid learning in design education | Kee, T.; Zhang, H.; King, R.B | International Journal of Technology and Design Education | 2024 |

| [54] | MOOC learners' perspectives of the effects of self-regulated learning strategy intervention on their self-regulation and speaking performance | Dinh, C.-T.; Phuong, H.-Y. | Cogent Education | 2024 |

| [55] | Fostering students' systems thinking competence for sustainability by using multiple real-world learning approaches | Demssie, Y.N.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Wesselink, R.; Mulder, M. | Environmental Education Research | 2023 |

| [56] | Designing a transmedia educational process in non-formal education: Considerations from families, children, adolescents, and practitioners | Erta-Majó, A.; Vaquero, E. | Contemporary Educational Technology | 2023 |

| [57] | Enhancing authentic learning in a rural university: exploring student perceptions of Moodle as a technology-enabled platform | Maphosa, V. | Cogent Education | 2024 |

| [58] | Students' mindset to adopt AI chatbots for effectiveness of online learning in higher education | Rahman, M.K.; Ismail, N.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Hossen, M.S. | Future Business Journal | 2025 |

| [59] | Towards a Creative Virtual Environment for Design Thinking | Gebbing, P.; Lattemann, C.; Büdenbender, E.N. | Pacific Asia journal of the Association for Information Systems | 2023 |

| [60] | An Empirical Study of A Smart Education Model Enabled by the Edu-Metaverse to Enhance Better Learning Outcomes for Students | Shu, X.; Gu, X. | Systems | 2023 |

| [61] | Developing an Evidence- and Theory-Informed Mother-Daughter mHealth Intervention Prototype Targeting Physical Activity in Preteen Girls of Low Socioeconomic Position: Multiphase Co-Design Study | Brennan, C.; ODonoghue, G.; Keogh, A.; Rhodes, R.E.; Matthews, J. | JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting | 2025 |

| [62] | Modeling the Critical Factors Affecting the Success of Online Architectural Education to Enhance Educational Sustainability | Metinal, Y.B.; Gumusburun Ayalp, G. | Sustainability | 2024 |

| [63] | Gamified Digital Game-Based Learning as a Pedagogical Strategy: Student Academic Performance and Motivation | Camacho-Sánchez, R.; Rillo-Albert, A.; Lavega-Burgués, P. | Applied Sciences | 2022 |

| [64] | Does gamification affect the engagement of exercise and well-being? | Chang, S.-C.; Chiu, Y.-P.; Chen, C.-C. | International Journal of Electronic Commerce Studies | 2023 |

| [65] | Developing a more engaging safety training in agriculture: Gender differences in digital game preferences | Vigoroso, L.; Caffaro, F.; Micheletti Cremasco, M.; Cavallo, E. | Safety Science | 2023 |

3.2. Study Details

3.3. Methodological Details

3.4. Positive Effect on Students of Mobile Technology Use

4. Discussion

4.1. Three Ways Classroom Use of Cellphones is Considered Detrimental

4.1.1. Health-Related Concerns

4.1.2. Antisocial Issues

4.1.3. Educationally Controversial

4.2. Relevance of the Results to a Reconsideration of Cellphone Banning

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaldygozova, S. Using Mobile Technologies in Distance Learning: A Scoping Review. ELIJ 2024, 2, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, R.; Lalwani, P.; Choudhary, G.; You, I.; Pau, G. Study and Investigation on 5G Technology: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2021, 22, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.M. Difficulties in Defining Mobile Learning: Analysis, Design Characteristics, and Implications. Education Tech Research Dev 2019, 67, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.; Holloway, D.; Stevenson, K.; Leaver, T.; Haddon, L. The Routledge Companion to Digital Media and Children; Routledge companions; Routledge: New York (N.Y.) Abingdon, 2021; ISBN 978-1-138-54434-5. [Google Scholar]

- Goggin, G. Introduction: What Do You Mean “Cell Phone Culture”?! In Cell phone culture: mobile technology in everyday life; Routledge: London, 2007; ISBN 978-0-415-36744-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kodukula, V. 2020 ACM Sigmobile Outstanding Contribution Award: Martin Cooper. GetMobile: Mobile Comp. and Comm. 2021, 24, 27–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Han, B. Evolution to Fifth-Generation (5G) Mobile Cellular Communications. In Cellular Communication Networks and Standards; Textbooks in Telecommunication Engineering; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-57819-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hamad, A.; Jia, B. How Virtual Reality Technology Has Changed Our Lives: An Overview of the Current and Potential Applications and Limitations. IJERPH 2022, 19, 11278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.; Brantley, S.; Feng, J. A Mini Review of Presence and Immersion in Virtual Reality. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 2021, 65, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Duarte, F.; Duranton, G.; Santi, P.; Barthelemy, M.; Batty, M.; Bettencourt, L.; Goodchild, M.; Hack, G.; Liu, Y.; et al. Defining a City — Delineating Urban Areas Using Cell-Phone Data. Nat Cities 2024, 1, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh, Q.V.; Hoai, N.V.; Manh, L.D.; Le, A.N.; Jeon, G. Wireless Communication Technologies for IoT in 5G: Vision, Applications, and Challenges. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.W. Electromagnetic Fields, 5G and Health: What about the Precautionary Principle? J Epidemiol Community Health 2021, 75, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCredden, J.E.; Weller, S.; Leach, V. The Assumption of Safety Is Being Used to Justify the Rollout of 5G Technologies. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1058454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.; Prince, I.A.; Islam, M.S.; Ahamed, Md.T.; Sarker, M.N.R.; Adhikary, A. Revolutionizing Connectivity Through 5G Technology. IJAERS 2025, 12, 01–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.B.; Sears, M.E.; Morgan, L.L.; Davis, D.L.; Hardell, L.; Oremus, M.; Soskolne, C.L. Risks to Health and Well-Being From Radio-Frequency Radiation Emitted by Cell Phones and Other Wireless Devices. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selwyn, N.; Aagaard, J. Banning Mobile Phones from Classrooms—An Opportunity to Advance Understandings of Technology Addiction, Distraction and Cyberbullying. Brit J Educational Tech 2021, 52, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Désiron, J.C.; Petko, D. Academic Dishonesty When Doing Homework: How Digital Technologies Are Put to Bad Use in Secondary Schools. Educ Inf Technol 2023, 28, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtice, E.L.; Shaughnessy, K. Four Problems in Sexting Research and Their Solutions. Sexes 2021, 2, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale, W.T.; Hutcheson, R.; Russo, C.J. Cell Phones, Student Rights, and School Safety: Finding the Right Balance. cjeap 2021, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gath, M.E.; Monk, L.; Scott, A.; Gillon, G.T. Smartphones at School: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Educators’ and Students’ Perspectives on Mobile Phone Use at School. Education Sciences 2024, 14, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakurt, T.; Yilmaz, B. Teachers’ Views on the Use of Mobile Phones in Schools. Journal of Computer and Education Research 2021, 9, 575–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, I.; Bernstein, A. Dynamics of Internal Attention and Internally-Directed Cognition: The Attention-to-Thoughts (A2T) Model. Psychological Inquiry 2022, 33, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Hong, J.-C.; Dong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Fu, Q. Self-Directed Learning Predicts Online Learning Engagement in Higher Education Mediated by Perceived Value of Knowing Learning Goals. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 2023, 32, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartkamp-Bakker, C.; Bradford, M.R. Guest Editorial: Reimagined Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing: Understanding the Value of a Self-Directed Educational Context. OTH 2024, 32, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, V.; Maheswary, U.; Swami, K.; Kumar, M.D.; Madhusudhanan, R.; Chandrakhanthan, J. Fostering Self-Directed Learning Among Millennial and Gen Z Learners Through E-Learning Platforms and ICT. In Anticipating Future Business Trends: Navigating Artificial Intelligence Innovations; El Khoury, R., Ed.; Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-63568-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin, M.D. Developing Self-Directed Learning Skills for Lifelong Learning: In Advances in Higher Education and Professional Development; Hughes, P., Yarbrough, J., Eds.; IGI Global, 2022; pp. 209–234 ISBN 978-1-79987-661-8.

- Morris, T.H. Four Dimensions of Self-Directed Learning: A Fundamental Meta-Competence in a Changing World. Adult Education Quarterly 2024, 74, 236–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalla, M.; Jerowsky, M.; Howes, B.; Borda, A. Expanding Formal School Curricula to Foster Action Competence in Sustainable Development: A Proposed Free-Choice Project-Based Learning Curriculum. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjukunju, A.; Ahmad, A.; Yusof, P. Self-Directed Learning Skills of Undergraduate Nursing Students. Enfermería Clínica 2022, 32, S15–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woezik, T.E.T.; Koksma, J.J.-J.; Reuzel, R.P.B.; Jaarsma, D.C.; Van Der Wilt, G.J. There Is More than ‘I’ in Self-Directed Learning: An Exploration of Self-Directed Learning in Teams of Undergraduate Students. Medical Teacher 2021, 43, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeds for Change Consensus Decision Making: A Short Guide Second Edition. Seeds for Change 2020.

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, B.; Li, X. Integrating Virtual Reality and Consensus Models for Streamlined Built Environment Design Collaboration. J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 2024, 150, 04024010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.; Zhu, S.; Li, Y.; Van Ameijde, J. Digitally Gamified Co-Creation: Enhancing Community Engagement in Urban Design through a Participant-Centric Framework. Des. Sci. 2024, 10, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, L.P. Distraction and Dependence: The Loss of Reflective Self-Direction. In Human Agency, Artificial Intelligence, and the Attention Economy; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; ISBN 978-3-031-82085-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gebbing, P.; Lattemann, C.; Büdenbender, E.N. Towards a Creative Virtual Environment for Design Thinking. Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2023, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA PRISMA for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). PRISMA 2020 2024.

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best Practice Guidance and Reporting Items for the Development of Scoping Review Protocols. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A.; Duncan, A.A. Systematic and Scoping Reviews: A Comparison and Overview. Seminars in Vascular Surgery 2022, 35, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, F.; Wiese, I.; Lima, C.; Polato, I.; Nepomuceno, V.; Ferreira, W.; Ribeiro, M.; Pena, C.; Cartaxo, B.; Pinto, G.; et al. Grey Literature in Software Engineering: A Critical Review. Information and Software Technology 2021, 138, 106609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA PRISMA 2020 Statement. PRISMA 2024.

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Research Synthesis Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusenbauer, M. Google Scholar to Overshadow Them All? Comparing the Sizes of 12 Academic Search Engines and Bibliographic Databases. Scientometrics 2019, 118, 177–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.; Healey, R.L. Searching the Literature on Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL): An Academic Literacies Perspective: Part 1. TLI 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, R.; Foxx, S.P.; Bolin, S.T.; Prioleau, B.; Dameron, M.L.; Vazquez, M.; Perry, J. Examining Self-Efficacy and Preparedness to Succeed in Post-Secondary Education: A Survey of Recent High School Graduates. Journal of School Counseling 2021, 19, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, P.; Zheng, J. Exploring the Interplay Among Student Identity Development, University Resources, and Social Inclusion in Higher Education: Analyzing Students as Partners Project in a Hong Kong University. Social Sciences 2025, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, D.A.; Manning, D.K. Open Educational Resources: The Promise, Practice, and Problems in Tertiary and Post-Secondary Education. In Open Educational Resources in Higher Education; Olivier, J., Rambow, A., Eds.; Future Education. In Open Educational Resources in Higher Education; Olivier, J., Rambow, A., Eds.; Future Education and Learning Spaces; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; Olivier, J., Rambow, A., Eds.; ISBN 978-981-19858-9-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann, S. Teaching Counts! Open Educational Resources as an Object of Measurement for Scientometric Analysis. Quantitative Science Studies 2025, 6, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.; Bond, J. The Effects and Implications of Using Open Educational Resources in Secondary Schools. IRRODL 2022, 23, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H. Implementing Open Educational Resources in Digital Education. Education Tech Research Dev 2021, 69, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, T.; Zhang, H.; King, R.B. An Empirical Study on Immersive Technology in Synchronous Hybrid Learning in Design Education. Int J Technol Des Educ 2024, 34, 1243–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, C.-T.; Phuong, H.-Y. MOOC Learners’ Perspectives of the Effects of Self-Regulated Learning Strategy Intervention on Their Self-Regulation and Speaking Performance. Cogent Education 2024, 11, 2378497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demssie, Y.N.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Wesselink, R.; Mulder, M. Fostering Students’ Systems Thinking Competence for Sustainability by Using Multiple Real-World Learning Approaches. Environmental Education Research 2023, 29, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erta-Majó, A.; Vaquero, E. Designing a Transmedia Educational Process in Non-Formal Education: Considerations from Families, Children, Adolescents, and Practitioners. CONT ED TECHNOLOGY 2023, 15, ep442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphosa, V. Enhancing Authentic Learning in a Rural University: Exploring Student Perceptions of Moodle as a Technology-Enabled Platform. Cogent Education 2024, 11, 2410096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Ismail, N.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Hossen, M.S. Students’ Mindset to Adopt AI Chatbots for Effectiveness of Online Learning in Higher Education. Futur Bus J 2025, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebbing, P.; Lattemann, C.; Büdenbender, E.N. Towards a Creative Virtual Environment for Design Thinking. Pacific Asia journal of the Association for Information Systems 2023, 15, 1–2815401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Gu, X. An Empirical Study of A Smart Education Model Enabled by the Edu-Metaverse to Enhance Better Learning Outcomes for Students. Systems 2023, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.; ODonoghue, G.; Keogh, A.; Rhodes, R.E.; Matthews, J. Developing an Evidence- and Theory-Informed Mother-Daughter mHealth Intervention Prototype Targeting Physical Activity in Preteen Girls of Low Socioeconomic Position: Multiphase Co-Design Study. JMIR Pediatr Parent 2025, 8, e62795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metinal, Y.B.; Gumusburun Ayalp, G. Modeling the Critical Factors Affecting the Success of Online Architectural Education to Enhance Educational Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Sánchez, R.; Rillo-Albert, A.; Lavega-Burgués, P. Gamified Digital Game-Based Learning as a Pedagogical Strategy: Student Academic Performance and Motivation. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 11214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-C.; Chiu, Y.-P.; Chen, C.-C. Does Gamification Affect the Engagement of Exercise and Well-Being? IJECS 2023, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoroso, L.; Caffaro, F.; Micheletti Cremasco, M.; Cavallo, E. Developing a More Engaging Safety Training in Agriculture: Gender Differences in Digital Game Preferences. Safety Science 2023, 158, 105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soprano, M.; Roitero, K.; La Barbera, D.; Ceolin, D.; Spina, D.; Demartini, G.; Mizzaro, S. Cognitive Biases in Fact-Checking and Their Countermeasures: A Review. Information Processing & Management 2024, 61, 103672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenbark, J.R.; Yoon, H. (Elle); Gamache, D.L.; Withers, M.C. Omitted Variable Bias: Examining Management Research With the Impact Threshold of a Confounding Variable (ITCV). Journal of Management 2022, 48, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.F.; Maxwell, S.E. There’s More than One Way to Conduct a Replication Study: Beyond Statistical Significance. Psychological Methods 2016, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar, E.; Radunz, M.; Galanis, C.R.; Quinney, B.; Wade, T.D.; King, D.L. Student Perspectives on Banning Mobile Phones in South Australian Secondary Schools: A Large-Scale Qualitative Analysis. Computers in Human Behavior 2025, 167, 108603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, M. How Many Participants Do We Have to Include in Properly Powered Experiments? A Tutorial of Power Analysis with Reference Tables. Journal of Cognition 2019, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: The State of the Field. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 2023, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aondover, P.O.; Aondover, E.M. ; Abubakar Mohammed Babale Two Nations, Same Technology, Different Outcomes: Analysis of Technology Application in Africa and America. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yan, S. Transnational Technology Transfer Network in China: Spatial Dynamics and Its Determinants. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 2383–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, R.; Janodia, M.D. A Comparative Study on Activities of Technology Commercialisation in the ASEAN Member States – Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Singapore. In Digital transformation for business and society: contemporary issues and applications in Asia; Mohammad Nabil Almunawar, Ordóñez de Pablos, P., Muhammad, Anshari, Eds.; Routledge advances in organizational learning and knowledge management; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, Oxon New York, NY, 2024; ISBN 978-1-00-344129-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chiaraviglio, L.; Elzanaty, A.; Alouini, M.-S. Health Risks Associated With 5G Exposure: A View From the Communications Engineering Perspective. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2021, 2, 2131–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniyal, M.; Javaid, S.F.; Hassan, A.; Khan, M.A.B. The Relationship between Cellphone Usage on the Physical and Mental Wellbeing of University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. IJERPH 2022, 19, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwimana, A.; Ma, C.; Ma, X. Concurrent Rising of Dry Eye and Eye Strain Symptoms Among University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic Era: A Cross-Sectional Study. RMHP 2022, Volume 15, 2311–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Lin, J. Risk Factors for Neck Pain in College Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, H.; Alhammad, L.; Aldossari, B.; Alonazi, A. Prevalence and Interrelationships of Screen Time, Visual Disorders, and Neck Pain Among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study at Majmaah University. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, F.; Muganga, A.; Carr, D.; Sang, G. Students’ Perceptions of Project-Based Learning in K-12 Education: A Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence. International Journal of Instruction, 2024, 17, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, A.R.; Srisarajivakul, E.N.; Hasselle, A.J.; Pfund, R.A.; Knox, J. What Was a Gap Is Now a Chasm: Remote Schooling, the Digital Divide, and Educational Inequities Resulting from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Current Opinion in Psychology 2023, 52, 101632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Roll, S.C. Impacts of Working From Home During COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Well-Being of Office Workstation Users. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine 2021, 63, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toghroli, R.; Reisy, L.; Mansourian, M.; Azar, F.E.F.; Ziapour, A.; Mehedi, N.; NeJhaddadgar, N. Backpack Improper Use Causes Musculoskeletal Injuries in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Journal of Education and Health Promotion 2021, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warda, D.G.; Nwakibu, U.; Nourbakhsh, A. Neck and Upper Extremity Musculoskeletal Symptoms Secondary to Maladaptive Postures Caused by Cell Phones and Backpacks in School-Aged Children and Adolescents. Healthcare 2023, 11, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, E.; Blaurock, S.; Zander, L.; Anders, Y. Children’s Social-Emotional Development During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Protective Effects of the Quality of Children’s Home and Preschool Learning Environments. Early Education and Development 2024, 35, 1432–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girela-Serrano, B.M.; Spiers, A.D.V.; Ruotong, L.; Gangadia, S.; Toledano, M.B.; Di Simplicio, M. Impact of Mobile Phones and Wireless Devices Use on Children and Adolescents’ Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2024, 33, 1621–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuorre, M.; Orben, A.; Przybylski, A.K. There Is No Evidence That Associations Between Adolescents’ Digital Technology Engagement and Mental Health Problems Have Increased. Clinical Psychological Science 2021, 9, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wordu, H.; Nwoke, P.L.; Ikezam, F.N. Digital Media as Predictor of Antisocial Behaviour among Adolescents’ Students in Senior Secondary Schools in Imo State, Nigeria. International Journal of Advanced Education and Research 2021, 6, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Eskandari, H.; Vahdani Asadi, M.R.; Khodabandelou, R. The Effects of Mobile Phone Use on Students’ Emotional-Behavioural Functioning, and Academic and Social Competencies. Educational Psychology in Practice 2023, 39, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, F.B.; Gruzd, A.; Jacobson, J.; Hodson, J. To Troll or Not to Troll: Young Adults’ Anti-Social Behaviour on Social Media. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Malaeb, D.; Sarray El Dine, A.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. The Relationship between Smartphone Addiction and Aggression among Lebanese Adolescents: The Indirect Effect of Cognitive Function. BMC Pediatr 2022, 22, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robards, B.; Goring, J.; Hendry, N.A. Guiding Young People’s Social Media Use in School Policies: Opportunities, Risks, Moral Panics, and Imagined Futures. Journal of Youth Studies 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeza, E.; Ngidi, N.D.; Bhana, D.; Janak, R. Girls’ Experiences of Cellphone Porn Use in South Africa and Their Accounts of Sexual Risk in the Classroom. Culture, Health & Sexuality 2024, 26, 1413–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyeredzi, T.; Mpofu, V. Smartphones as Digital Instructional Interface Devices: The Teacher’s Perspective. Research in Learning Technology 2022, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krienert, J.L.; Walsh, J.A.; Cannon, K.D. Changes in the Tradecraft of Cheating: Technological Advances in Academic Dishonesty. College Teaching 2022, 70, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.B.; Arenas-Rivera, C.P.; Cardozo-Rusinque, A.A.; Morales-Cuadro, A.R.; Acuña-Rodríguez, M.; Turizo-Palencia, Y.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Psychological and Gender Differences in a Simulated Cheating Coercion Situation at School. Social Sciences 2021, 10, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwunemerem, O.P. Lessons from Self-Directed Learning Activities and Helping University Students Think Critically. Journal of Education and Learning 2023, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, S.; Hasanvand, S.; Gholami, M.; Mokhayeri, Y.; Amini, M. The Effect of the Online Flipped Classroom on Self-Directed Learning Readiness and Metacognitive Awareness in Nursing Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Nurs 2022, 21, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynan, L.; Cate, T.; Rhee, K. The Impact of Learning Structure on Students’ Readiness for Self-Directed Learning. Journal of Education for Business 2008, 84, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. Free Agent Learning: Leveraging Students’ Self-Directed Learning to Transform K-12 Education; First edition.; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, 2023; ISBN 978-1-119-78983-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard, L.; Bradford, A.; Linn, M.C. Supporting Teachers to Customize Curriculum for Self-Directed Learning. J Sci Educ Technol 2022, 31, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-C.; Chang, C.-Y. Evaluating Self-Directed Learning Competencies in Digital Learning Environments: A Meta-Analysis. Educ Inf Technol 2025, 30, 6847–6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, L.; Jurkowski, O.; Sims, S.K. ChatGPT in K-12 Education. TechTrends 2024, 68, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, H.; Wells, R.F.; Shanks, E.M.; Boey, T.; Parsons, B.N. Student Perspectives on the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence Technologies in Higher Education. Int J Educ Integr 2024, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammoh, L.A. ChatGPT in Academia: Exploring University Students’ Risks, Misuses, and Challenges in Jordan. Journal of Further and Higher Education 2024, 48, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Scoping Review of Self-Directed Online Learning, Public School Students’ Mental Health, and COVID-19 in Noting Positive Psychosocial Outcomes with Self-Initiated Learning. COVID 2023, 3, 1187–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzavela, V.; Alepis, E. M-Learning in the COVID-19 Era: Physical vs Digital Class. Educ Inf Technol 2021, 26, 7183–7203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranger-Johannessen, E.; Fjørtoft, S.O. Implementing Virtual Reality in K-12 Classrooms: Lessons Learned from Early Adopters. In Smart Education and e-Learning 2021; Uskov, V.L., Howlett, R.J., Jain, L.C., Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021; ISBN 9789811628337. [Google Scholar]

- Dr. A.Shaji George Technology Tension in Schools: Addressing the Complex Impacts of Digital Advances on Teaching, Learning, and Wellbeing. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Owen, D. Cell Phone Use in American Civics and History Classrooms. Computers in the Schools 2024, 41, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Fostering Academic Integrity in the Digital Age: Empowering Student Voices to Navigate Technology as a Tool for Classroom Policies. Brock Education Journal 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.L.; Radunz, M.; Galanis, C.R.; Quinney, B.; Wade, T. “Phones off While School’s on”: Evaluating Problematic Phone Use and the Social, Wellbeing, and Academic Effects of Banning Phones in Schools. JBA 2024, 13, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret-Catala, C.; Suárez-Guerrero, C.; Mateu-Luján, B. Teacher’s View of the Educational Relationship between Teenagers and Smartphones in Spain. Interactive Learning Environments 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Straus, S.; Moher, D.; Langlois, E.V.; O’Brien, K.K.; Horsley, T.; Aldcroft, A.; Zarin, W.; Garitty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; et al. Reporting Scoping Reviews—PRISMA ScR Extension. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2020, 123, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury-Jones, C.; Aveyard, H.; Herber, O.R.; Isham, L.; Taylor, J.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Reviews: The PAGER Framework for Improving the Quality of Reporting. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2022, 25, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Pollock, D.; Khalil, H.; Alexander, L.; Mclnerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Peters, M.; Tricco, A.C. What Are Scoping Reviews? Providing a Formal Definition of Scoping Reviews as a Type of Evidence Synthesis. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2022, 20, 950–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, J.L. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis: A Guide for Beginners. Indian Pediatr 2022, 59, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, T.M.S.; Lienert, P.; Denne, E.; Singh, J.P. A General Model of Cognitive Bias in Human Judgment and Systematic Review Specific to Forensic Mental Health. Law and Human Behavior 2022, 46, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández Pinto, M. Methodological and Cognitive Biases in Science: Issues for Current Research and Ways to Counteract Them. Perspectives on Science 2023, 31, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Parameters | # |

|---|---|---|

| EBSCO | Keywords: “self-directed learning” AND “ mobile technology” “co-creation” “virtual worlds”, Child Development & Adolescent Studies, self-directed learning, mobile technology, co-creation, virtual worlds. Search modes: Find all my search terms, Apply related words, Also search within the full text of the articles, Apply equivalent subjects, Linked Full Text, Publication Date: Start January 2021 End March 2025, Peer Reviewed, Document Type: article, Academic Journal, English | 47 |

| JSTOR | Keywords: “self-directed learning” AND “ mobile technology” “co-creation” “virtual worlds”, Content I can access, Articles, English, 2021-2025, Communication Studies, Education, Health Policy, Health Sciences, Psychology, Public Health | 0 |

| OVID | Keywords Embase Classic+Embase 1947 to 2025 March 28 APA PsycInfo 1806 to March 2025 Week 4 Ovid Healthstar 1966 to February 2025 Journals@Ovid Full Text March 28, 2025 Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL 1946 to March 28, 2025, self-directed learning, mobile technology, co-creation, virtual worlds, 2021-current, English Language, Full Text, Humans, Data Paper | 0 |

| ProQuest | Keywords: “self-directed learning” AND “mobile technology” AND “ co-creation” AND “virtual worlds”, After 1 January 2021, Article, English, Scholarly Journal | 57 |

| PubMed | Keywords: self-directed learning AND mobile technology AND co-creation AND virtual worlds | 0 |

| Scopus | Keywords: self-directed learning AND mobile technology AND co-creation AND virtual worlds, 2021-present. Limited to Social Sciences, Medicine, Arts and Humanities, Psychology, E-learning, Human, Education, Higher Education, Virtual Reality, Gamification, Humans, Students, Self Efficacy, Online Learning, On-line Communities, Educational Technology, Co-creation, COVID-19, Article, Digital-learning | 18 |

| Web of Science | Keywords: self-directed learning AND mobile technology AND co-creation AND virtual worlds, 2021-present | 0 |

| Google Scholar | Keywords: "self-directed learning" "mobile technology" "co creation" "virtual worlds", “2021-2025”, “no citations” | 12 |

| # | StudyAim | Participants | Study Date | Location |

| [53] | Expand studio-based design education to technology-enhanced collaborative learning to support experiential learning | 3rd and 4th year undergraduate students (n = 75) | 2018-2019 | Hong Kong |

| [54] | Investigate the impact of a self-regulated learning strategy intervention on students’ SRL skills and explore their perspectives of the intervention after being taught the SRL strategies during their learning in massive open online courses (MOOCs) | English majors (n = 61) | 9-26 March 2023 | Vietnam |

| [55] | Exploring the contributions of field trips and collaborative learning in combination with mobile learning and paper-and-pencil note-taking | Bachelor’s geography and environmental studies students (n = 36) | May-June 2019 | Ethiopia |

| [56] | Describe the necessary items to be considered when developing a transmedia educational process in a non-formal educational designed space oriented to families, children, and/or adolescents | Children (n = 23), adolescents (n = 12), parents (n = 11) | 2020 | Spain |

| [57] | Exploring students’ perceptions of the authentic learning opportunities provided by Moodle at a rural university, to link their lived experiences with their educational journeys through technology-enabled environments that foster active participation, collaboration, and co-creation of knowledge | 1st year undergraduate students in their second semester (n = 192) | Post onset of COVID-19 pandemic | Zimbabwe |

| [58] | Understanding students’ perspectives and factors affecting the adoption of AI chatbots to maximize student use in online and virtual educational environments | University students (n = 429) | February- April 2024 | Malaysia |

| [59] | Investigating which Design Principles (DPs) to prioritize in designing a user-centered creative virtual environment, and which Design Features (DFs) effectively implement the DPs in creative virtual collaboration from a user perspective | International students from Asia, Africa, America, and Europe (n = 38) | January 2021 5-day workshop, August 2021, and August 2022, one-day workshops | Germany |

| [60] | Exploring the impact of immersive technology on the actual experiential learning traditionally gained through physical site visits in design education | 3rd and 4th year undergraduate students (n = 75) | Between 2018 and 2019 | Hong Kong |

| [61] | Using co-design methods to develop an evidence- and theory-informed mother-daughter mobile health intervention prototype targeting physical activity in preteen girls | Preteen girls (n=10), mothers of preteen girls (n=9), and primary school teachers (n=6) | 2024 | United Kingdom |

| [62] | Determining the critical factors hindering successful online architectural education during the pandemic | Architecture students (n = 232) | 30 April 2022–28 July 2022 | Turkey |

| [63] | Analyzing the effects on academic performance and motivation after an experience combining Digital game-based learning and Gamification in university students | University students (n = 126) | 2022 | Spain |

| [64] | Examining the relationship between gamification features, engagement, and well-being | Those willing to play an energame for 30 minutes three times a week (n = 56) | October 2021 | Taiwan |

| [65] | Investigate game preferences, regarding game characteristics, genre, and graphic style for creating practical guidelines for the design of a gamified safety training tool in agriculture | Agriculture university students (n = 137) | 2019 | Italy |

| # | Outcomes Regarding Aim | Study Type | Significance |

| [53] | Students gave a significantly higher rating to virtual world learning over traditional learning, having a positive correlation with active experimentation, co-design, and providing a flexible reflective process, but not peer-review | Qualitative and Quantitative regarding survey questionnaire | Statistical for several learning variables but not for peer review |

| [54] | Increase in students’ goalsetting, environmental structuring abilities, and time management. The interviews underscored the importance of employing self-directed learning techniques for learning in Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) | Convergent parallel mixed methods using survey data quantitatively | Statistical for goal setting, environment structuring, and time management |

| [55] | Field trips and collaborative learning in combination with mobile learning and paper-and-pencil note-taking suggest that the learning approaches and the real-world environment contribute to fostering the systems thinking competence of participants by exposing them to complex real-world systems and enabling the exchanging of diverse ideas among collaborating participants | Pre-test–post-test exploratory experimental study with a focus on the interdependence of variables | Statistical significance was not tested, and the results demonstrate participant appreciation of system complexity |

| [56] | Important to consider multiple perspectives, including those of facilitators, children and adolescents, and parents, when designing transmedia educational processes, and to use a variety of media platforms, formats, and channels to engage diverse and heterogeneous groups of participants in non-formal educational settings | Qualitative analysis of multiformat focus groups | Statistical significance was untested with the content analysis finding a need for professional training in processes and technology |

| [57] | The majority of the students agreed that Moodle assignments closely resembled real-world problems. The implementation of project-based learning within Moodle supported independence and autonomy in students, allowing them to determine their learning patterns and complete assignments, offering a variety of assessments that facilitated the consolidation of ideas and the development of artifacts applicable to real-world communities | Descriptive and explanatory research design using questionnaire design | Statistical regarding no off-campus internet access to Moodle, and students possessing good to excellent computer skills |

| [58] | Perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEU), and tech competency (TC) have a significant impact on AI capability. Subjective norm (SN) has no significant impact on AI chatbot capability. The capability of AI chatbots significantly influences the adoption of AI chatbots for learning effectiveness. The findings indicated that AI chatbot capability mediates the effect of PU, PEU, and TC on the adoption of AI chatbots; however, there is no mediating effect in the relationship between SN and AI chatbot capability to maximize their use in online and virtual educational environments. Facilitating conditions moderate the effect of PU and TC on AI chatbot capability | Quantitative based on survey results | Highly statistically significant influence of perceived AI chatbot capability on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use— statistically significant relationship with adopting AI chatbots for online learning |

| [59] | (1) Provide rich, appropriate resources to inspire creative thinking; (2) Technical problems and connectivity issues must be anticipated and mitigated; (3) The environment must foster social presence and interaction, and (4) effective communication and visualization; (5) Methods and technologies must be adapted to the creative process and individual needs; (6) The group work benefits from structured but flexible tasks and time management support; (7) Provide space for individual work that allows autonomy and solitary contemplation | Qualitative thematic analysis | Statistical significance was not tested, but 133 codes were assigned |

| [60] | Results supported and affirmed the study that a smart education model enabled by the Edu-Metaverse can significantly enhance the learning outcomes for the students in comparison to traditional teaching patterns where students engaged in the experimental group yielded higher scores in oral English vocabulary and grammar, reading comprehension, and writing than those in the control group | Pre- and post-tests, interviews, and a quantitative assessment of a questionnaire | Differences between the experimental group and the control group were considered statistically significant |

| [61] | A comprehensive description and analysis of using co-design methods to develop a mother-daughter mobile health intervention prototype that is ready for feasibility and acceptability testing, framework, and techniques ontology provided a systematic and transparent theoretical foundation for developing the prototype by enabling the identification of potential pathways for behavior change | Three phases: (1) behavioral analysis, (2) the selection of intervention components, and (3) refinement of the intervention prototype. | Statistical significance was not tested. Identified: 11 theoretical domains, 6 intervention functions, and 27 behavior change techniques |

| [62] | A structural equation model revealed support, engagement, and communication obstacles in online architectural education, digital learning environment barriers in online architectural education, and technological integration and accessibility problems in online architectural education are evident in Turkey | Quantitative based on questionnaire results | Each hypothesis exceeds the critical one-tailed t-value of 2.58 at a significance level of 0.01. |

| [63] | The gamified Digital Game-Based Learning (DGBL) method is an exciting teaching tool that corresponds to students’ active learning and provides valuable immediate feedback on students’ attempts, offering improvements in academic performance and a high level of motivation | A mixed methods design, with quantitative and qualitative data assessing spatially and temporally delimited events | Gamified DGBL led to significant differences in student academic performance when cooperative; however, there was no significant difference when competition was involved |

| [64] | Results indicated that immersion, achievement, and social interaction-related features were positively associated with Exergame users' emotional, cognitive, and social engagement, and these engagements are likely to increase well-being further | Structured questionnaire and descriptive statistical methods | The t-values of all items were significant, and the average variance extracted was greater than 0.5 for all constructs |

| [65] | Some clear differences (in tasks, quests, rules, goals, colors, and variety), and similarities (in graphics, drama, better rewards, and game genre) emerged in differentiating male and female preferences for digital games as an occupational safety training method in the agriculture sector | Quantitative analysis of online questionnaire | Significant association found between gender and the type of games played with males preferring crafting games with no significant gender differences in intention to play these games |

| # | Self-directed learning | Consensus decision-making | Student mental health |

| [53] | Design students move away from instructor-led activities to self-directed learning as they can explore resources and processes autonomously to achieve learning goals, which are no longer defined by teachers but set by themselves in immersive experiential learning | The co-create project spanning the semesters helped develop skills in communication and group collaboration to enhance experiential learning, | Positive confirmation of concrete experience, epitomizing the authentic learning process and attainment of practical experience from experiential learning activities |

| [54] | There is an intricate connection between self-directed learning and oral communication skills since speaking proficiently requires a strong command of vocabulary through presentation skills that are effective | When self-regulated learning skills are embedded within this process, one can enhance their speaking proficiency | Learner engagement, including cognitive, behavioral, and emotional engagement, and value co-creation, referred to as ‘the actions of multiple actors, often unaware of each other, that contribute to each other’s wellbeing’ |

| [55] | Study contributes to social constructivist learning discourses in education for sustainable development by indicating specific combinations of learning approaches and environments that facilitate the meaningful engagement and motivation of learners through self-regulated learning | Learner-centered approaches that allow learners to engage in knowledge co-creation, collaboration, and authentic learning environments | The combination of relevant knowledge and positive attitude the participants demonstrated in their reports seems promising to encourage them to take sustainability-friendly decisions and actions as individual citizens or professionals |

| [56] | Non-formal education is more flexible, adaptative, self-directed, and learner-centered than formal education, with a greater focus on learner needs and interests | Transmedia storytelling goes beyond the collaborative work and places itself in the communitarian work in building learning communities | The transmedia approach can have a positive impact on improving people skills and competencies through socio-educative processes that are basic to maintaining a good environment of participation and collaboration that builds the social ties of the group |

| [57] | The significance of autonomous learning in the success of Learning Management Systems is that learners must rely on their self-directed control over learning activities, with limited support from tutors and peers | Moodle allows learners to be co-designers, provide feedback to each other, and apply acquired knowledge and theories in solving real-life challenges | Learning Management Systems support authentic learning by promoting collaboration, self-paced learning, interactivity, and reflectivity, which contribute to high levels of student satisfaction |

| [58] | AI Chatbots can effectively enhance independent learning abilities among students by promoting self-directed learning activities | Unlike collaborative tools which necessitate group participation (e.g., discussion forums), AI chatbots tend to be used individually for self-directed learning, minimizing the importance of social impact as a factor | Perceived usefulness of AI chatbots facilitates user engagement and satisfaction related to communication support needs, especially within online learning systems. Students trust chatbots that they perceive as performing at high levels |

| [59] | To instill a creative mindset, the environment should provide a sense of freedom and possibilities for self-expression. Further, the setting should provide possibilities to work autonomously and be self-directed, according to one’s needs and preferences | Co-creation and innovation processes are now more flexible and location-independent, but virtual collaboration still poses challenges, such as technical difficulties and limited social presence | There was a positive activation of Mood, atmosphere, and group attitude. To maintain a positive mood, the group must develop a tolerance for ambiguity and coping strategies to deal with frustrations |

| [60] | The teaching scenario design was with instructional needs in mind, and learners identified the problems and explored the ways to solve them using self-directed inquiry and cooperative learning | Social interaction and collaboration with their teacher and peers through technology-based communication tools positively influenced their learning outcomes as each learning group functioned as a community with common goals and with a sense of identity and belonging in the process of cooperation | Social interactions, collaborations with other students and tutors, and a good learning climate may influence student learning outcomes positively and enhance e-learning satisfaction |

| [61] | The self-directed messages enable mothers and daughters to reflect on why they want to engage and sustain the behaviors. | Offers a comprehensive description and analysis of using co-design methods to develop a mother-daughter mobile health intervention prototype that is ready for feasibility and acceptability testing | This process was used to co-design a mHealth intervention prototype aimed at promoting physical activity in preteen girls, with a focus on maternal support behaviors, and is now ready for feasibility and acceptability testing |

| [62] | Proficiency in digital skills enables students to engage in self-directed learning effectively, identifying learning needs, utilizing online resources, applying information, and evaluating results, thereby enhancing work efficiency and productivity | This feedback loop as “reflective practice” represents dynamic involvement and co-creation between student and instructor as active learning | Psychosocial concerns in online architectural education are important issues contributing to the psychosocial health of students; therefore, despite the transition to online platforms, architectural education should remain highly interactive, incorporating active learning exercises and utilizing diverse online tools in the future |

| [63] | According to self-determination theory, intrinsic motivation increases engagement and performance more effectively than extrinsic motivation. When learners enjoy the internal logic or the dynamics of the game, learning is enjoyable, increasing intrinsic motivation | In comparing two types of gamification strategies for Motivation for Cooperative Playful Learning Strategies, there was no difference in the results of competitive versus individual | Integrating Digital game-based learning and Gamification in physical education can be used to achieve positive academic and motivational results in university learning as well as pursuing aspects such as physical performance or health improvement |

| [64] | Immersion-related features primarily aim to immerse the player in their self-directed inquiring activity, including gameplay mechanics such as avatars, virtual identity, storytelling, narrative structures, customization/personalization features, and roleplay mechanics | Online communities can foster norms of reciprocity and trust, thus creating opportunities for social engagement by encouraging users to feel connected to the topic | Social interaction-related features, such as 'likes', comments, collaborations, and teams, are believed to have naturally positive impacts on social engagement, Exergames have become a popular way to maintain physical and psychological health |

| [65] | The success of digital games can be related to how the games match player preferences, relevant to understanding and accommodate what the targeted players would like to see in a game, and what graphic style should be applied to make the game more engaging | In the present study where both genders highlighted the need to create a game that fosters cooperation, it appears encouraging that participants conceived the safety training as a process in which the final result (i.e., the safety performance) is reached only through collaborative efforts | The visual design plays a pivotal role in this training method not only for its graphical attractiveness but for its aptitude to engage the targeted users, develop a positive user experience and foster engagement and emotional involvement, improving behavioral safety performance and reducing negative safety and health outcomes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).