1. Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polyps, particularly in cases refractory to conventional medical and surgical treatment, is increasingly associated with laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (LPRD) as a significant contributing factor [

1,

2,

3]. LPRD, which is a different condition than gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), presents with a variety of upper respiratory tract disorders, including laryngitis, chronic cough, asthma, otitis media with effusion and, more recently, chronic rhinosinusitis [

3,

4].

Numerous studies have shown a higher prevalence of LPRD in patients with CRS, with some estimates suggesting that up to 60% of people with CRS have features of LPRD [

5,

6,

7]. This association is thought to be mediated by direct contact of refluxed gastric acid and pepsin with the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract, including the nasopharynx and sinuses [

8]. This exposure can disrupt epithelial integrity, alter mucociliary clearance and initiate or maintain a chronic inflammatory response [

8,

9]. In addition, the low pH and proteolytic enzymes in gastric contents can induce histological changes including epithelial hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia and increased inflammatory cell infiltration, potentially contributing to sinus dysfunction and remodeling [

9,

10].

Despite this growing body of evidence, the diagnosis of LPRD-associated CRS remains a significant clinical challenge. Symptomatic overlap with other upper respiratory diseases such as allergic rhinitis, non-allergic rhinitis or infectious rhinosinusitis often complicates the diagnostic process. In addition, current objective tests for LPRD, such as 24-hour oesophageal pH monitoring and multichannel intraluminal impedance pH (MII-pH), primarily assess acidic and non-acidic exposure of the oesophagus [

11,

12]. However, these methods do not provide direct information on reflux reaching the nasopharyngeal region or sinuses, limiting their usefulness in the assessment of suspected CRS due to extraesophageal reflux (EER).

There are currently no universally accepted clinical, radiographic or endoscopic criteria to definitively define cases of CRS as related to LPRD. Although symptom-based tools such as the Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) [

13] and Reflux Symptom Score (RSS) [

14] are commonly used to screen for EER, these tools rely entirely on subjective patient reports and do not capture the presence or severity of mucosal changes. In addition, the Reflux Detection Scale (RFS) [

15] a widely used endoscopic scoring system, has been developed to detect signs of laryngeal reflux, including erythema, oedema, ventricular obliteration and granuloma formation. However, it lacks specificity for nasopharyngeal involvement and does not take into account paranasal sinus pathology.

There are currently no universally accepted clinical, radiographic or endoscopic criteria to definitively define cases of LPRD-related CRS. Although symptom-based tools such as the Reflux Symptom Index and Reflux Symptom Score are commonly used to screen for CRS, these tools rely entirely on subjective patient reports and do not capture the presence or severity of mucosal changes. In addition, the Reflux Detection Score (RFS), a widely used endoscopic scoring system, has been developed to detect signs of laryngeal reflux, including erythema, oedema, ventricular obliteration and granuloma formation. However, it lacks specificity for nasopharyngeal involvement and does not take into account paranasal sinus pathology. In response to these limitations, the Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score (NRES) was developed as a standardised and objective method for the assessment of endoscopic findings indicative of nasopharyngeal reflux. The NRES includes visual parameters such as erythema, oedema, mucus congestion and tissue granularity in the nasopharynx and adjacent areas. By providing a reproducible and quantitative assessment, the NRES aims to improve diagnostic accuracy, facilitate early detection of reflux-related sinus disease and guide targeted therapeutic interventions.

By examining the validity and reliability of this new scoring tool, this study contributes to the growing effort to improve CRS phenotyping and better characterise the subset of patients whose sinus pathology may be due to extraesophageal reflux. Establishing accurate and accessible diagnostic criteria is critical to optimising treatment strategies, reducing symptom burden and avoiding unnecessary interventions in this complex and often underdiagnosed population.

2. Materials and Methods

The Local Ethical Commission of “Astana Medical University” NpJSC approved the study protocol (LCB NpJSC AMU #13). The database is available as 10.6084/m9.figshare.28861565

Study Design and Participants

This prospective, observational, comparative cohort study with longitudinal follow-up was conducted in adult patients with chronic nasal symptoms lasting more than 12 months who were seen by both an otolaryngologist and a gastroenterologist. Between September 2023 and February 2025, a total of 216 patients with a diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis (with or without nasal polyps—CRSwNP/CRSsNP) were evaluated and treated at the University Medical Center Corporate Fund (UMC CF) and Multidisciplinary Hospital #1 in Astana, Kazakhstan. Participants were stratified into three groups based on symptomatology and diagnostic criteria: Patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRSwNP/CRSsNP) and concomitant laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (LPRD) identified by the RSS (n = 116); Patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRSwNP/CRSsNP) without LPRD symptoms (RSS-negative) (n = 69); Healthy controls (n = 31).

Additional diagnostic assessments, including 24-hour dual-probe pH monitoring and gastrointestinal endoscopy, were performed in selected cases to confirm the presence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and to further characterise the reflux phenotype. RSS, RSI was used to support the clinical diagnosis of LPRD in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis.

The diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis was established based on the EPOS 2020 criteria [

16], which incorporate a combination of clinical symptoms, nasal endoscopy findings—particularly assessed using the Lund-Kennedy Score (L-K)—and computed tomography imaging.

All patients in the primary cohort underwent prospective examination prior to treatment, and at six- and 12-months following treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). This was accompanied by meticulous lifestyle modifications aimed at mitigating the emergence of GERD symptoms. All patients were administered 20 mg of omeprazole twice daily, for 1 or 2 months after the first and second visit.

Each patient underwent a comprehensive examination, including fibreoptic rhinoscopy with photodocumentation of the nose and nasopharynx, transnasal fiberoptic laryngoscopy, and Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score, Lund-Kennedy Score, Reflux Finding Score determination at each visit. A follow-up examination was conducted at a second clinic within one week.

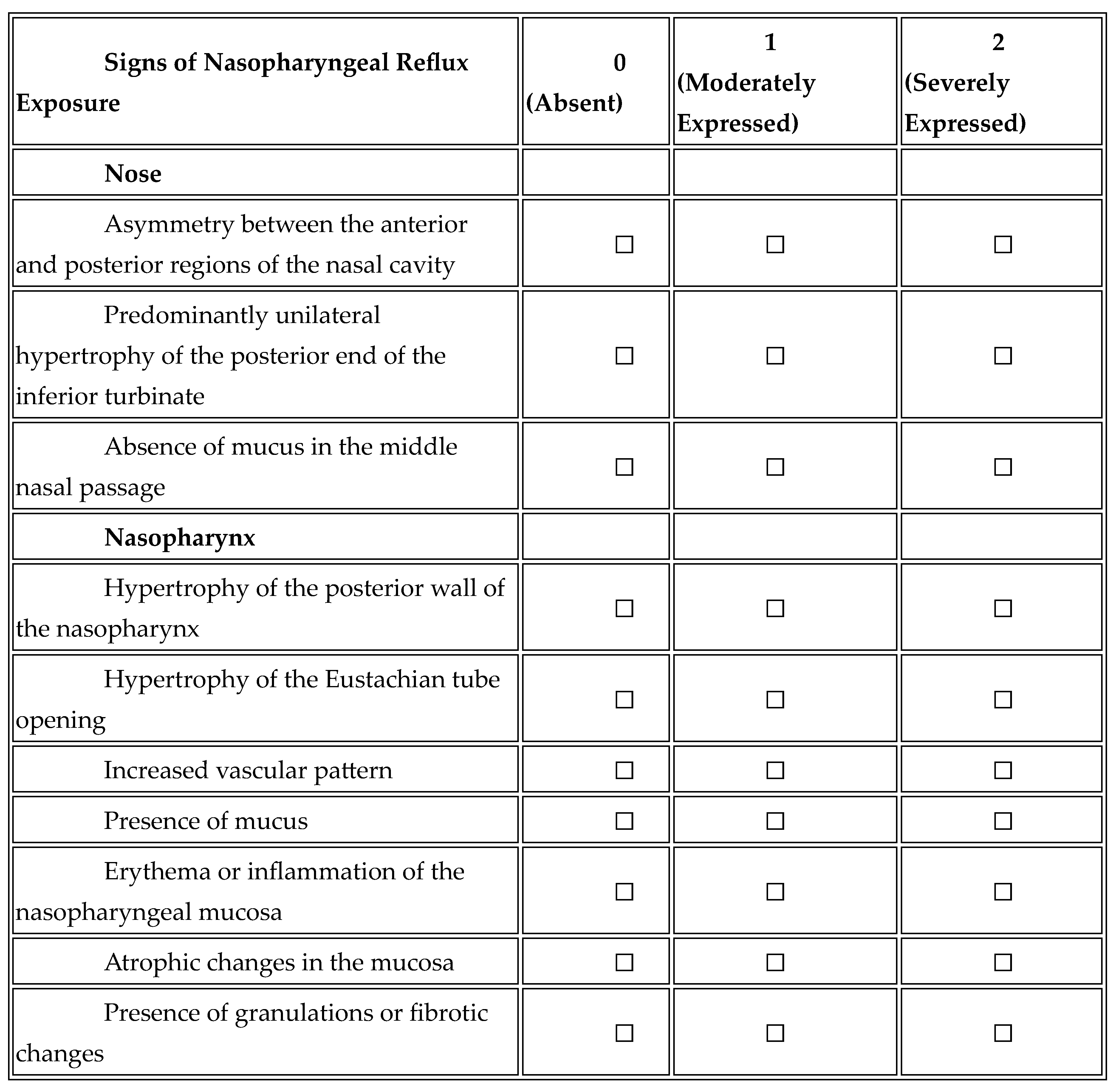

Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score (NRES)

A novel endoscopic scale assessing nasopharyngeal mucosal changes related to GERD.

Table 1.

“Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score (NRES)”.

Table 1.

“Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score (NRES)”.

The NRES was independently scored in a blinded fashion by two experienced otolaryngologists from two clinics, within 7 days of each other, to ensure methodological rigour and to support the reliability of this new assessment tool.

Statistical methods.

The statistical methods employed in this study are outlined below:

1. Analysis of differences between groups: Kruskal-Wallis criterion (Kruskal-Wallis test). This method was employed to compare the values of scales (RSS, RSI, RFS, L-K, NRES) between the three groups. This non-parametric analogue of ANOVA is employed when the data do not adhere to a normal distribution. Dunn’s test was employed for pairwise comparisons between groups subsequent to identifying an overall significant difference using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The primary function of this test is to correct for multiple comparisons in order to avoid first-order error.

2. Assessing diagnostic accuracy: ROC analysis (Receiver Operating Characteristic analysis). The diagnostic accuracy of the NRES scale was evaluated. Thirdly, the dynamics of change over time were analysed using the paired Wilcoxon test with Holm’s correction, which was employed to compare scale scores between three time points (1, 6 and 12 months). The Holm’s correction was employed to address the issue of multiple comparisons.

4. Correlation analysis: Spearman’s rank correlation was used to assess the degree of association between the following scales: NRES1, RSS1, RSI1, RFS1 and Lund-Kennedy.

5. Regression analysis: multiple linear regression, the dependence of NRES1 on age, Los Angeles (LA) classification of GERD severity and gender was assessed.

A range of analytical methods were used, including non-parametric methods such as Kruskal-Wallis test, Dunn’s test and Wilcoxon test, and parametric approaches such as ROC analysis and regression. These approaches were used to objectively assess differences between groups, the diagnostic accuracy of the NRES, the dynamics of change, and the relationships between scales.

3. Results

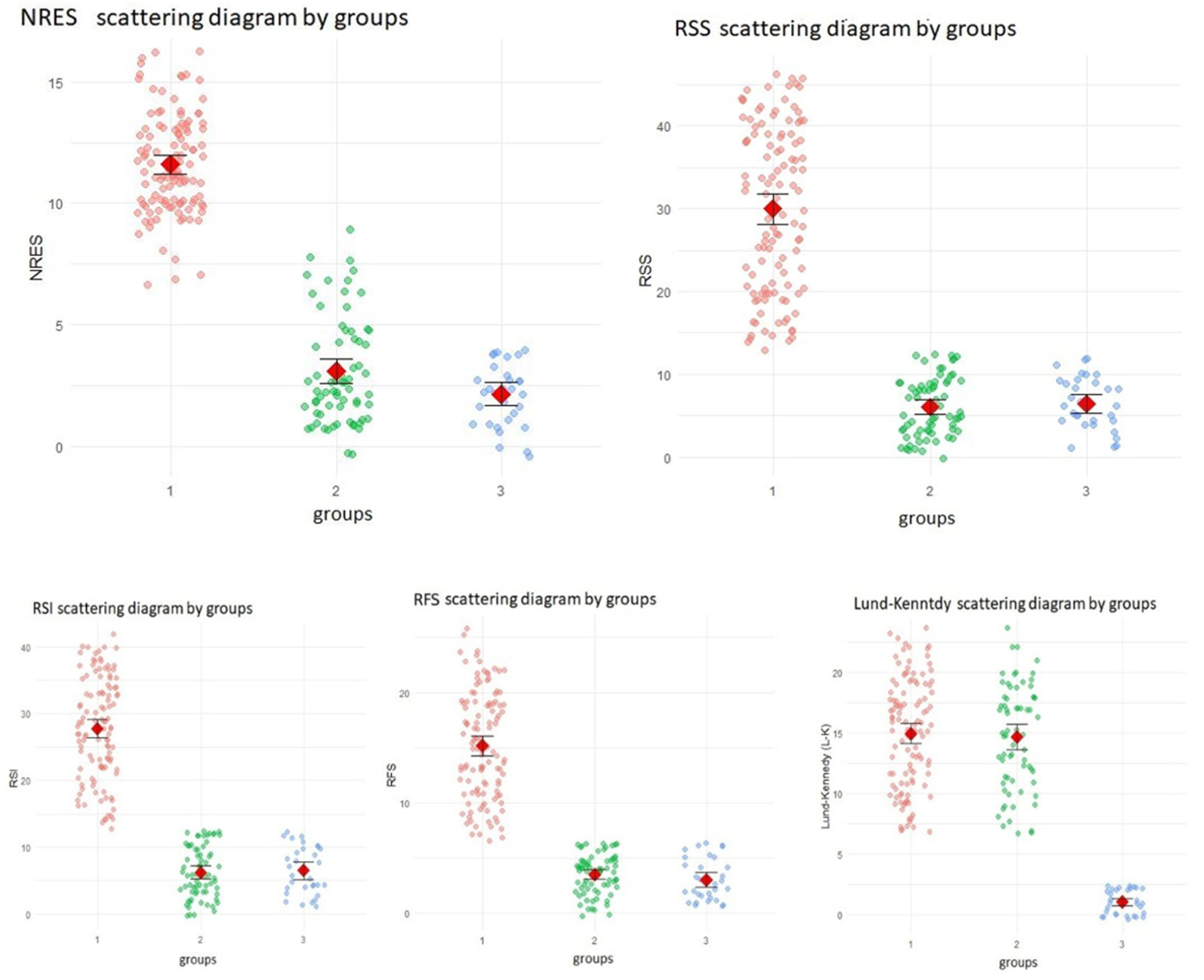

Summarizing the differences in reflux and sinonasal indicators (RSS, RSI, RFS, L-K and NRES) between the three study groups based on the Kruskal-Wallis test—a non-parametric alternative to one-way ANOVA used to compare three or more independent groups. Due to the non-normal distribution of the data, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons.

All indicators showed statistically significant differences between the three groups (p < 0.0001). Pairwise comparisons showed that for RSS, RSI, RFS and NRES there were statistically significant differences between Group 1 and both Group 2 and Group 3 (p < 0.0001for all), but no significant differences between Group 2 and Group 3 (p > 0.05). This suggests that the first group had significantly increased reflux and nasopharyngeal scores compared to the other two groups.

In contrast, Lund-Kennedy scores showed no significant difference between group 1 and group 2 (p = 0.888), whereas statistically significant differences were found between group 1 and group 3 and between group 2 and group 3 (p = p < 0.0001). This pattern suggests that sinonasal endoscopic findings were similar between the first and second groups, but significantly lower in the third group.

These results support the hypothesis that nasopharyngeal and reflux-specific scores (RSS, RSI, RFS and NRES) are more sensitive in distinguishing LPRD -associated sinonasal pathology than traditional sinonasal scores such as L-K. The results of these comparisons are further illustrated in the following figures.

Figure 1.

differences between groups.

Figure 1.

differences between groups.

The findings of the present analysis indicate a statistically significant disparity between the first group and both the second and third groups with respect to the indicators RSS, RSI, RFS and NRES. Conversely, no such significant variations were observed between the second and third control groups with regard to these metrics.

3.1. Diagnostic Accuracy of NRES (ROC Analysis)

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score (NRES) (see

Table 3 and

Figure 2). For this purpose, the study population was divided into three comparator groups: Group 1 (n = 116), consisting of patients with confirmed chronic rhinosinusitis and LPRD, was assigned code 1. Groups 2 (n = 69) and 3 (n = 31), consisting of patients without LPRD -associated CRS, were assigned codes 2 and 3, respectively.

The results showed exceptional diagnostic performance of the NRES scale, with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.998, indicating near perfect discriminatory ability. The model had a sensitivity of 98%, correctly identifying 99% of true positives, and a specificity of 96%, correctly identifying 96% of true negatives (

Table 2). These metrics underscore the high diagnostic utility of the NRES in distinguishing LPRD-associated CRS from other presentations.

The optimal cut-off value for the NRES scale was found to be 8.5, providing the best balance between sensitivity and specificity. Patients scoring above this threshold were classified as having LPRD -associated CRS.

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of NRES.

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of NRES.

| AUC |

0.998 |

| threshold for NRES1 |

8,5 |

| Sensitivity, True Positive Rate, TPR |

98% |

| Specificity, True Negative Rate, TNR |

96% |

The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was found to be 0.998, indicating a high diagnostic value of the test.

The optimal threshold of NRES was determined to be 8.5.

The sensitivity (TPR) was found to be 98%, indicating that the test correctly identifies 98% of patients with the disease.

The specificity (TNR) was found to be 96%, indicating the test’s capacity to correctly identify 96% of healthy patients.

The diagnostic accuracy of the NRES scale is confirmed by high AUC (0.998), sensitivity (98%) and specificity (96%), making it a reliable tool for detecting the disease. The optimal threshold of 8.5 allows for effective differentiation between patients with and without the disease.

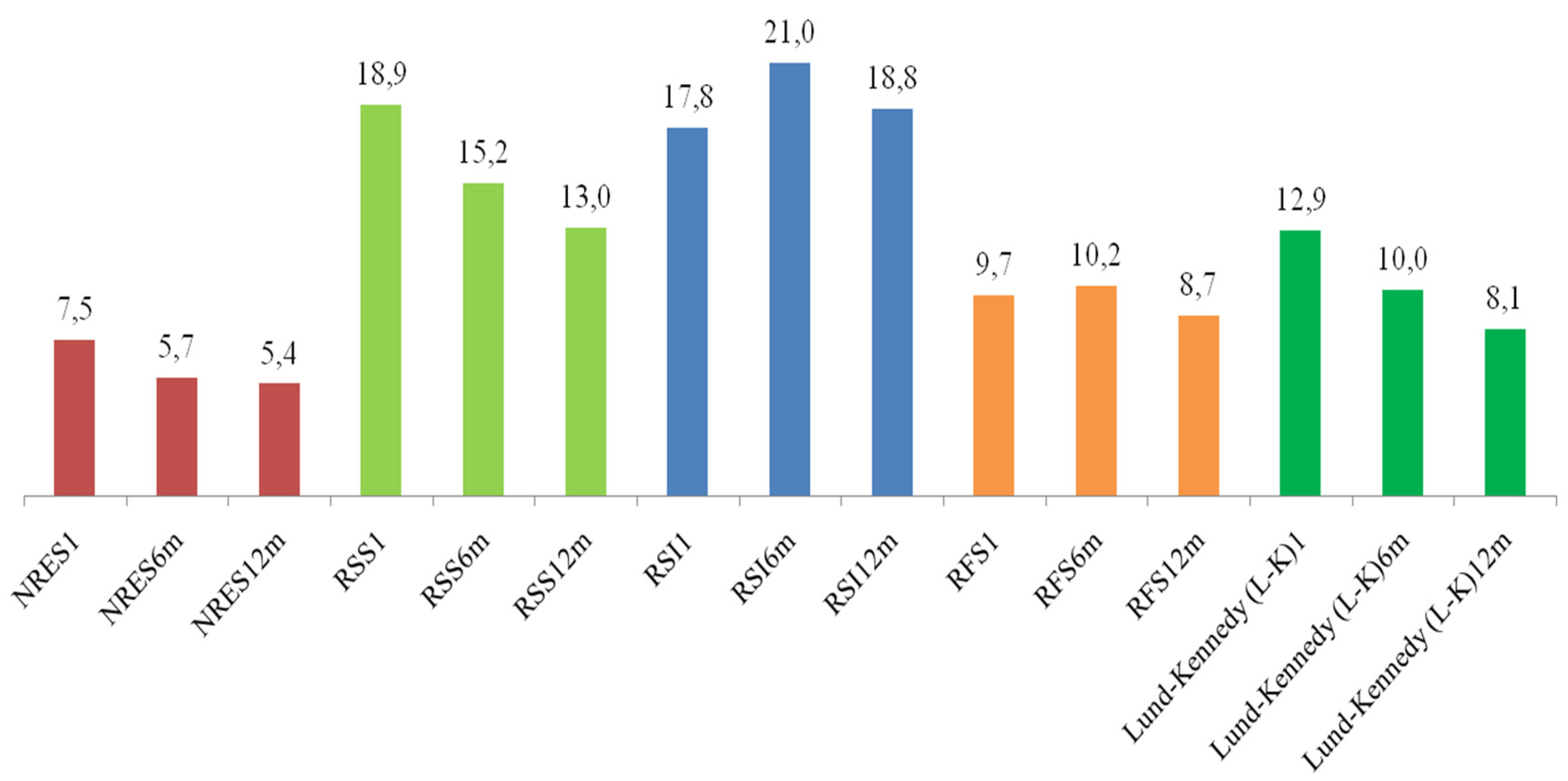

3. Dynamics of Changes in Scales After 6 and 12 Months

The indicators on the scales (with the exception of RSI and RFS) NRES, RSS and Lund-Kennedy (L-K) demonstrate a downward trend. Statistically significant differences are observed between periods on all scales (see

Table 3).

Table 3.

Paired Wilcoxon tests with Holm correction for scales.

Table 3.

Paired Wilcoxon tests with Holm correction for scales.

| Scales, comparison |

p-value |

| NRES1 |

NRES6m |

<0.001 |

| NRES1 |

NRES12m |

<0.001 |

| NRES6m |

NRES12m |

0,017 |

| RSS1 |

RSS6m |

<0.001 |

| RSS1 |

RSS12m |

<0.001 |

| RSS6m |

RSS12m |

<0.001 |

| RSI1 |

RSI6m |

<0.001 |

| RSI1 |

RSI12m |

<0.001 |

| RSI6m |

RSI12m |

<0.001 |

| RFS1 |

RFS6m |

<0.001 |

| RFS1 |

RFS12m |

<0.001 |

| RFS6m |

RFS12m |

<0.001 |

| Lund-Kennedy (L-K)11 |

Lund-Kennedy (L-K)16m |

<0.001 |

| Lund-Kennedy (L-K)11 |

Lund-Kennedy (L-K)112m |

<0.001 |

| Lund-Kennedy (L-K)16m |

Lund-Kennedy (L-K)112m |

<0.001 |

A detailed analysis of the dynamics of changes in indicators on various scales over a period of six and 12 months was conducted, which revealed a marked tendency for values to decrease on the majority of scales, with the exception of RSI and RFS. To assess the statistical significance of differences between time points, a paired Wilcoxon test with Holm’s correction was used, which allowed for control of the level of type I errors in multiple comparisons.

The primary findings of the study are as follows:

The Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score (NRES) exhibited a substantial decline in scores following a period of six months (p <0.001) and subsequently after a duration of twelve months (p <0.001). The difference between the 6-month and 12-month measurements was also found to be statistically significant (p = 0.017), suggesting that the improvement observed at 6 months of follow-up persisted over time.

It is evident that all scales demonstrate significant improvement in dynamics. A decline in values is evident as early as six months, yet further decreases (particularly in NRES, RSS, RFS and L-K) suggest a sustained positive effect persists beyond twelve months. Statistically significant differences between the 6-month and 12-month periods (particularly for NRES, RSS, and L-K) indicate that the improvement does not cease after six months, but rather persists throughout the year. Consequently, the findings of this study, which span a period of up to 12 months, underscore the necessity for prolonged observation of the dynamics in patients diagnosed with chronic rhinosinusitis and gastroesophageal reflux, emphasizing the importance of long-term assessment in this particular cohort.

4. Correlation Across Scales

To further explore the relationships between symptom-based and endoscopic assessment tools in patients with reflux-associated chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), a Spearman correlation analysis was performed between five diagnostic scales: Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score (NRES), Reflux Symptom Score (RSS), Reflux Symptom Index (RSI), Reflux Finding Score (RFS) and Lund-Kennedy (L-K). The results are summarized in

Table 4.

The analysis shows strong positive correlations between NRES and the symptom-based and laryngeal endoscopic indices: RSS (r = 0.768), RSI (r = 0.766) and RFS (r = 0.769). These values, which are in the range of 0.7-0.8, indicate a high level of agreement and suggest that the NRES captures a similar clinical spectrum of reflux-related changes as these validated scales. The agreement between these scales also supports the convergent validity of the NRES in identifying LPRD -associated CRS.

In contrast, moderate correlations were observed between the NRES and the Lund-Kennedy (L-K) score (r = .221), and between the L-K and the other symptom scales (ranging from .242 to .284). These weaker correlations suggest that the Lund-Kennedy scale may capture different aspects of sinonasal pathology, possibly reflecting structural or non-reflux-related inflammatory changes.

Overall, the high intercorrelation between NRES, RSS, RSI and RFS confirms that these scales assess overlapping clinical phenomena—in particular the impact of reflux on upper airway structures. The comparatively weaker relationship between L-K and the reflux-related scales reinforces the hypothesis that traditional sinonasal endoscopy may not be sufficient to detect extraesophageal reflux-related changes.

These findings highlight the importance of a multimodal diagnostic strategy that includes both subjective symptom scores (RSS, RSI) and objective endoscopic assessments (NRES, RFS) to improve diagnostic accuracy in patients with suspected reflux-associated CRS. The inclusion of NRES adds a valuable dimension by targeting the nasopharyngeal region, which is often overlooked in standard assessments.

5. Regression Analysis

Linear regression analysis was performed to investigate the relationship between the Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score (NRES1) and several clinical variables: age, race, and the Los Angeles (LA) classification of GERD severity. The model was based on 116 observations.

The regression equation yielded an R² value of 0.061, indicating that the model explained only 6.1% of the variance in NRES1 scores, indicating low predictive power. The adjusted R² value of 0.018 also indicates that the inclusion of these predictors does not significantly improve the explanatory power of the model. The overall model was not statistically significant with an F-statistic of 1.419 (p = 0.223).

The following

Table 5 summarizes the estimates, standard errors, t-statistics and p-values for each of the predictors included in the regression model

Table 5:

| term |

estimate |

std.error |

statistic |

p.value |

| (Intercept) |

12,94621936 |

0,766071047 |

16,89950222 |

0,000 |

| age |

-0,02046886 |

0,014314153 |

-1,429973523 |

0,156 |

| race |

-0,452673187 |

0,40994756 |

-1,104222178 |

0,272 |

| `LA Classification`B |

-0,153630492 |

0,432067518 |

-0,355570567 |

0,723 |

| `LA Classification`C |

-1,023346692 |

0,537950794 |

-1,902305385 |

0,060 |

| `LA Classification`D |

-0,860190641 |

1,46213281 |

-0,588312248 |

0,558 |

The intercept of 12.946 indicates the baseline NRES1 score for individuals classified as having LA category A GERD, with no influence from other variables (age, race or GERD classification).

The negative coefficient for age (-0.020) suggests that for every year of age, the NRES1 score decreases by 0.020, although this relationship was not statistically significant (p = 0.156). This weak association may indicate a limited effect of age on NRES1 scores in the population studied.

The variable race had a non-significant negative association with NRES1 scores (-0.453, p = 0.272), suggesting no substantial difference in NRES1 scores based on race in this sample.

The coefficient for LA Classification B (-0.154) was not statistically significant (p = 0.723), suggesting that this level of GERD severity does not significantly affect NRES1 scores compared to Category A. LA Classification C showed a borderline negative association with NRES1 scores (-1.023, p = 0.060). Although this finding did not meet the conventional significance threshold (p < 0.05), the p-value suggests a trend towards lower NRES1 scores in patients with LA category C compared to those with LA category A, which may be clinically meaningful.

The association with LA category D was also not significant (-0.860, p = 0.558), suggesting no difference in NRES1 scores for this subgroup compared to category A.

This regression analysis does not provide strong evidence of a statistically significant association between age, race or LA classification and NRES1 scores in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and GERD. However, the trend observed for LA classification C warrants further investigation in larger, more robust studies to explore potential associations. The low explanatory power of the model highlights the complexity of factors influencing NRES1 scores and suggests that additional variables may need to be considered in future research to better understand this relationship.

4. Discussion

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a well-established inflammatory disease of the upper respiratory tract, primarily characterised by persistent inflammation of the nasal and paranasal sinus mucosa lasting 12 weeks or longer despite appropriate medical therapy [

16]. Clinically, CRS is associated with a constellation of symptoms, including nasal obstruction, nasal discharge, facial pressure or pain, and reduction or loss of the sense of smell [

16]. The underlying pathophysiology is multifactorial, involving infectious, allergic, environmental and possibly reflux-related mechanisms [

17].

Over the past two decades, increasing attention has been paid to the extraesophageal manifestations of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD), particularly in the context of upper airway disease [

17,

18]. Among these, CRS has emerged as a potential sequela of extra-oesophageal reflux [

19,

20,

21]. Unlike typical GERD, where reflux is confined to the oesophagus, EER involves the retrograde flow of both acidic and non-acidic gastric contents beyond the oesophagus into the larynx, nasopharynx and potentially the sinuses [

22].

This atypical pattern of reflux is thought to contribute to upper airway pathology through several mechanisms. These include direct mucosal injury, promotion of persistent inflammation, impairment of mucociliary clearance and disruption of epithelial barrier function [

23,

24,

25]. Together, these effects may exacerbate or perpetuate the inflammatory processes underlying CRS, highlighting the importance of considering EER in the differential diagnosis and management of refractory cases [

26,

27,

28,

29].

Despite the increasing recognition of this clinical phenotype, the diagnosis of LPRD -related CRS remains challenging and underdeveloped. One of the main challenges is the non-specificity of symptoms. Patients often complain of nasal congestion, postnasal drip, throat clearing or cough—symptoms that largely overlap with allergic rhinitis, non-allergic rhinitis or primary CRS [

30]. As a result, misclassification or underdiagnosis is common, and many patients may be subjected to repeated courses of antibiotics or unnecessary surgery without relief.

Modern diagnostic approaches to extraesophageal reflux (EER) often involve a combination of symptom-based and objective assessments. Instruments such as the Reflux Symptom Index and Reflux Symptom Score provide structured and validated means of quantifying EER-related symptoms [

13,

14]. While these tools are valuable for initial assessment and monitoring, their reliance on patient-reported outcomes introduces an element of subjectivity that may affect diagnostic specificity and limit their stand-alone utility in clinical decision making. On the other hand, objective testing methods, including 24-hour oesophageal pH monitoring and multichannel intraluminal impedance pH (MII-pH) testing, are considered the gold standards for detecting acid and non-acid exposure of the oesophagus [

31,32]. However, these tests are limited in their anatomical coverage; they do not assess reflux that reaches the nasopharynx or paranasal sinuses and therefore cannot directly relate reflux events to sinonasal pathology.

The Reflux Detection Scale (RFS), a well-validated laryngoscopic tool, is often used to assess laryngeal signs indicative of reflux, such as erythema, vocal fold oedema and posterior commissure hypertrophy [

15]. However, like MII-pH testing, RFS does not assess the nasopharyngeal compartment or quantify changes specific to the nasal mucosa and sinuses.

To address this diagnostic gap, the Nasopharyngeal Endoscopic Reflux Score (NRES) has been introduced as a new standardised tool for the endoscopic assessment of reflux-related nasopharyngeal mucosal changes. The NRES incorporates specific visual parameters including erythema, oedema, granularity and mucus congestion, all of which are recognised indicators of mucosal inflammation and chronic irritation. By providing an objective basis for endoscopic classification, NRES allows clinicians to directly visualise and document the impact of EER on the nasopharyngeal mucosa.

This approach has important clinical implications. Incorporating NRES into routine assessment may improve differentiation between CRS subtypes, distinguishing LPRD -related cases from those due to other aetiologies such as allergy, infection or anatomical obstruction. Such stratification is important because LPRD -related CRS may respond better to antireflux therapy (e.g., proton pump inhibitors, dietary modification, or surgery) than to conventional sinus therapy alone.

The primary limitation of this study is the absence of hypopharyngeal-esophageal multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH (MII-pH) monitoring, which, despite its inability to detect nasopharyngeal reflux events directly, remains the most reliable method for confirming LPRD.

5. Conclusions

The Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score (NRES) is a reliable, objective tool for assessing LPRD -associated CRS. It correlates well with established reflux and sinonasal scales and has a high diagnostic accuracy. NRES scores improved significantly after PPI therapy, supporting its utility in treatment monitoring. Blinded assessment by two ENT specialists ensured the reliability of the scores. Although some associations with LA classification were found, further studies with broader variables are needed to validate the NRES as a standard diagnostic and monitoring tool.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S. and N.P.; methodology, K.S.; software, K.S.; validation, G.M., T.A.; formal analysis, K.S.; investigation, K.S., N.P., G.M., T.A..; resources, K.S.; data curation, K.S., N.P.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S.; writing—review and editing, J.L.; visualization, K.S.; supervision, N.P.; project administration, K.S.; funding acquisition, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Astana Medical University (Approval No. 13).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

10.6084/m9.figshare.28861565.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRSwNP/CRSsNP |

Chronic rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polyps |

| LPRD |

laryngopharyngeal reflux disease |

| RSI |

Reflux Symptom Index |

| RSS |

Reflux Symptom Score |

| NRES |

The Nasopharyngeal Reflux Endoscopic Score |

| L-K |

Lund-Kennedy |

| EPOS |

The European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020 |

| RFS |

Reflux Finding Score |

| ROC |

Receiver operating characteristic |

| PPIs |

proton pump inhibitors |

| GERD |

gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| MII-pH |

multichannel intraluminal impedance pH |

| EER |

extraesophageal reflux |

References

- Lechien, J.R.; Ragrag, K.; Kasongo, J.; Favier, V.; Mayo-Yanez, M.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.M.; Iannella, G.; Cammaroto, G.; Saibene, A.M.; Vaira, L.A.; Carsuzaa, F.; Sagandykova, K.; Fieux, M.; Lisan, Q.; Hans, S.; Maniaci, A. Association between Helicobacter pylori, reflux and chronic rhinosinusitis: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldajani, A.; Alhussain, F.; Mesallam, T.; AbaAlkhail, M.; Alojayri, R.; Bassam, H.; Alotaibi, O.; Alqahtani, M.; Alsaleh, S. Association Between Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Reflux Diseases in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2024, 38, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyawali, C.P.; Kahrilas, P.J.; Savarino, E.; Zerbib, F.; Mion, F.; Smout, A.J.P.M.; Vaezi, M.; Sifrim, D.; Fox, M.R.; Vela, M.F.; Tutuian, R.; Tack, J.; Bredenoord, A.J.; Pandolfino, J.; Roman, S. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon Consensus. Gut. 2018, 67, 1351–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, J.W.; Vela, M.F.; Peterson, K.A.; Carlson, D.A. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Extraesophageal Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023, 21, 1414-1421.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2023.01.040. Epub 2023 Apr 14. PMID: 37061897.Brown HJ, Kuhar HN, Plitt MA, Husain I, Batra PS, Tajudeen BA. The Impact of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux on Patient-reported Measures of Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2020, 129, 886–893. doi: 10.1177/0003489420921424. [PubMed]

- Sella, G.C.P.; Tamashiro, E.; Anselmo-Lima, W.T.; Valera, F.C.P. Relation between chronic rhinosinusitis and gastroesophageal reflux in adults: systematic review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 83, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bohnhorst, I.; Jawad, S.; Lange, B.; Kjeldsen, J.; Hansen, J.M.; Kjeldsen, A.D. Prevalence of chronic rhinosinusitis in a population of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2015, 29, e70–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniaci, A.; Vaira, L.A.; Cammaroto, G.; Favier, V.; Lechien, J.R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, laryngopharyngeal reflux, and nasopharyngeal reflux in chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 3295–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Xie, H. Gastroesophageal Reflux and Chronic Rhinosinusitis: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Laryngoscope. 2024, 134, 3086–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Cao, X.; Wang, H. Pathogenesis of pepsin-induced gastroesophageal reflux disease with advanced diagnostic tools and therapeutic implications. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025, 12:1516335. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maev, I.V.; Livzan, M.A.; Mozgovoi, S.I.; Gaus, O.V.; Bordin, D.S. Esophageal Mucosal Resistance in Reflux Esophagitis: What We Have Learned So Far and What Remains to Be Learned. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, I.; Kasmin, F. Esophageal pH Monitoring. 2023 Feb 6. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 31971729.

- Cumpston, E.C.; Blumin, J.H.; Bock, J.M. Dual pH with Multichannel Intraluminal Impedance Testing in the Evaluation of Subjective Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Symptoms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016, 155, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belafsky, P.C.; Postma, G.N.; Koufman, J.A. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). J Voice. 2002, 16, 274–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Bobin, F.; Muls, V.; Thill, M.P.; Horoi, M.; Ostermann, K.; Huet, K.; Harmegnies, B.; Dequanter, D.; Dapri, G.; Maréchal, M.T.; Finck, C.; Rodriguez Ruiz, A.; Saussez, S. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom score. Laryngoscope. 2020, 130, E98–E107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belafsky, P.C.; Postma, G.N.; Koufman, J.A. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS). Laryngoscope. 2001, 111, 1313–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokkens, W.J.; De Corso, E.; Backer, V.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Bjermer, L.; von Buchwald, C.; Chaker, A.; Diamant, Z.; Gevaert, P.; Han, J.; Hopkins, C.; Hox, V.; Klimek, L.; Lund, V.J.; Lee, S.; Luong, A.; Mullol, J.; Peters, A.; Pfaar, O.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Scadding, G.K.; Sedaghat, A.R.; Viskens, A.S.; Wagenmann, M.; Hellings, P.W. EPOS2020/EUFOREA expert opinion on defining disease states and therapeutic goals in CRSwNP. Rhinology. 2024, 62, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadlapati, R.; Chan, W.W. Modern Day Approach to Extraesophageal Reflux: Clearing the Murky Lens. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023, 21, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sidhwa, F.; Moore, A.; Alligood, E.; Fisichella, P.M. Diagnosis and Treatment of the Extraesophageal Manifestations of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Ann Surg. 2017, 265, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Xie, M.; Dong, L.; Jin, M.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Xue, F.; Jiang, L.; Yu, Q. Causal association of gastroesophageal reflux disease with chronic sinusitis and chronic disease of the tonsils and adenoids. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 2975–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagandykova, K.; Papulova, N.; Azhenov, T.; Darbekova, A.; Aigozhina, B.; Lechien, J.R. Endoscopic Features of Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024, 60, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, G.; Guo, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Causal analysis between gastroesophageal reflux disease and chronic rhinosinusitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 1819–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.W.; Vela, M.F.; Peterson, K.A.; Carlson, D.A. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Extraesophageal Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023, 21, 1414–1421.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianella, P.; Roncone, S.; Ala, U.; Bottero, E.; Cagnasso, F.; Cagnotti, G.; Bellino, C. Upper digestive tract abnormalities in dogs with chronic idiopathic lymphoplasmacytic rhinitis. J Vet Intern Med. 2020, 34, 1845–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, G.; Guo, W.; Liu, S. et al. Causal analysis between gastroesophageal reflux disease and chronic rhinosinusitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 281, 1819–1825 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Han, Z.; Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; He, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, T.; Li, H. The interplay of inflammation and remodeling in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis: current understanding and future directions. Front Immunol. 2023, 14:1238673. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.G.; Kong, I.G. The association between chronic rhinosinusitis and proton pump inhibitor use: a nested case-control study using a health screening cohort. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, B.; Lim, H.; Kim, M.; Kong, I.G.; Choi, H.G. Gastroesophageal reflux disease increases the risk of chronic rhinosinusitis: a nested case-control study using a national sample cohort. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.K.; Vaezi, M.F. Gastroesophageal reflux monitoring: pH (catheter and capsule) and impedance. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachert, C.; Han, J.K.; Desrosiers, M.; Hellings, P.W.; Amin, N.; Lee, S.E.; Mullol, J.; Greos, L.S.; Bosso, J.V.; Laidlaw, T.M.; Cervin, A.U.; Maspero, J.F.; Hopkins, C.; Olze, H.; Canonica, G.W.; Paggiaro, P.; Cho, S.H.; Fokkens, W.J.; Fujieda, S.; Zhang, M.; Lu, X.; Fan, C.; Draikiwicz, S.; Kamat, S.A.; Khan, A.; Pirozzi, G.; Patel, N.; Graham, N.M.H.; Ruddy, M.; Staudinger, H.; Weinreich, D.; Stahl, N.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Mannent, L.P. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019, 394, 1638–1650, Erratum in: Lancet. 2019 Nov 2;394(10209):1618. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32218-4. PMID: 31543428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzić, S.A.; Turkalj, M.; Župan, A.; Labor, M.; Plavec, D.; Baudoin, T. Eight weeks of omeprazole 20 mg significantly reduces both laryngopharyngeal reflux and comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis signs and symptoms: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018, 43, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.K.; Vaezi, M.F. Gastroesophageal reflux monitoring: pH (catheter and capsule) and impedance. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).