Trial Registration and Study Design

This trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04875338) on 29/04/2021. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (Approval No: 10180). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment. The study was designed as a prospective, single-blinded, randomized controlled trial with patients allocated in a 1:1:1 ratio into glucocorticoid, PRP, and saline injection groups. The study period was from April 2021 to April 2022.

Introduction

Lateral epicondylitis, commonly referred to as “tennis elbow,” is a prevalent condition that affects the insertion site of the forearm extensor muscles at the lateral epicondyle.(24) It occurs in approximately 1-3% of the population, with a higher prevalence in individuals aged 40 to 55 years.(28) Lateral epicondylitis predominantly affects the dominant side, particularly in individuals engaged in occupations requiring strong grip and repetitive wrist movements.15 Additional risk factors include frequent keyboard use, overhead activities, and exposure to hand-transmitted vibrations from tools such as hammers and drills.(34) The condition is associated with several adverse effects, including functional impairment in daily and professional activities, increased psychological stress, and prolonged workplace absenteeism.(1) With the aging population, the need for effective and minimally invasive treatment modalities has become increasingly important.(7) Various treatment options for lateral epicondylitis have been described in the literature, including rest, anti-inflammatory medications, cryotherapy, bracing, botulinum toxin injections, acupuncture, corticosteroid injections, and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections.(30, 31) However, there remains significant controversy regarding the most effective treatment approach. Despite advancements in treatment techniques, standardized protocols are lacking, leading to variability in clinical practice.(22)

The self-limiting nature of lateral epicondylitis, with 80% of patients recovering within one year, may explain the wide variety of treatment options available.(6) The efficacy of PRP, corticosteroid, and placebo (saline) injections has been widely debated among researchers. PRP is commonly utilized in various fields, including wound healing, bone nonunion treatment, plastic surgery, and dermatology.(27)

The use of PRP in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis is based on its theoretical ability to stimulate repair mechanisms and promote healing, similar to its effects in other tendinopathies.(10) Its anti-inflammatory properties have been demonstrated in cellular studies.(23) The literature reports that a single PRP injection can significantly improve quality of life even six months post-treatment and may be superior to corticosteroid injections. (3, 14)

Recent reviews and randomized controlled studies have indicated that placebo saline injections, PRP, and corticosteroid injections yield similar outcomes in the medium and long term. (29, 21, 17).

In addition to treatment, the diagnosis and follow-up of lateral epicondylitis are equally important. Ultrasonography (USG) is particularly advantageous due to its affordability, accessibility, and ease of use (25) Quantitative ultrasonographic measurements have shown high inter-reader reliability. A common extensor tendon cross-sectional area ≥32 mm² and a thickness of ≥4.2 mm have been found to correlate with lateral epicondylitis.(19) Furthermore, increased neovascularization in patients with lateral epicondylitis has been reported to be more effectively visualized using superb microvascular imaging (SMI) compared to Doppler USG.(4)

The aim of this study was to determine whether clinical and radiological changes are correlated in the mid-term following corticosteroid, PRP, and saline injections in patients with lateral epicondylitis. Based on our hypothesis, changes in clinical scores are not correlated with radiological findings. To investigate this, we sought to address the following questions:

Method

Study Design and Participants

On April 2, 2021, the study (approval number 10180) was approved by the Ethics Committee and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov under the identification code NCT04875338. Between April 2021 and April 2022, individuals presenting with pain around the lateral epicondyle during wrist and finger extension against resistance, along with tenderness upon palpation, were diagnosed with lateral epicondylitis and considered for inclusion in the study. (

26) Patients with symptoms lasting at least three months, aged over 18 years, and who had not received prior treatment were included in the study. (

Table 1) A power analysis was conducted during the planning phase, and using Lehr’s formula, it was determined that a minimum of nine patients per group would be required to achieve 80% power at a 5% significance level. (

20)

Human Ethics and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine. All participants were fully informed about the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before enrollment. Participation was voluntary, and patients had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence. Personal data were anonymized to ensure confidentiality.

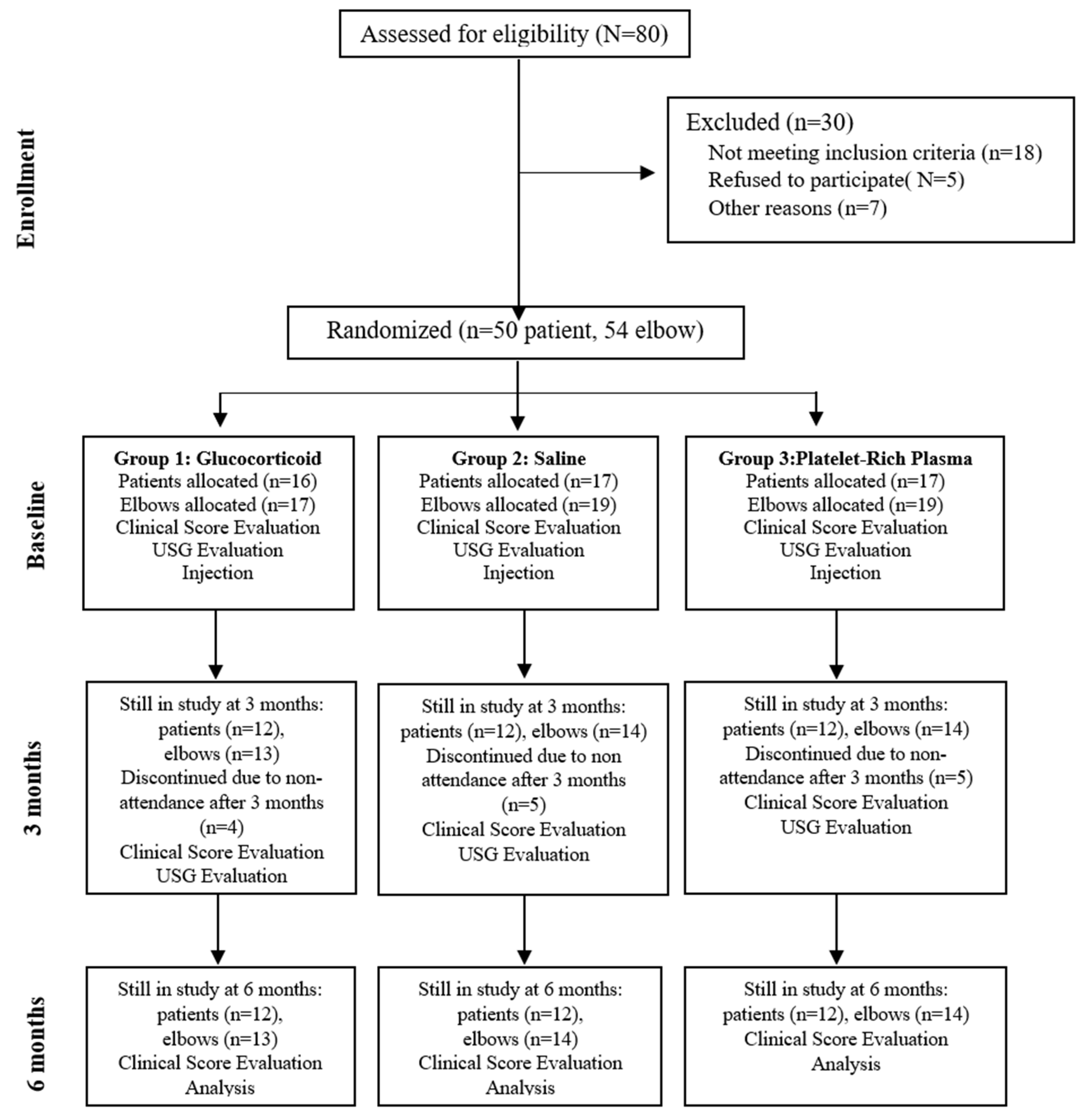

The study was designed as a prospective trial. Patients with elbow deformities, neurologic disorders, systemic inflammatory diseases, cervical radiculopathy, or a history of surgery on the same upper extremity were excluded. A total of 55 elbows from 50 patients meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Prior to treatment initiation, patients were randomized into three groups in a 1:1:1 ratio. (

Figure 1).

USG Procedure

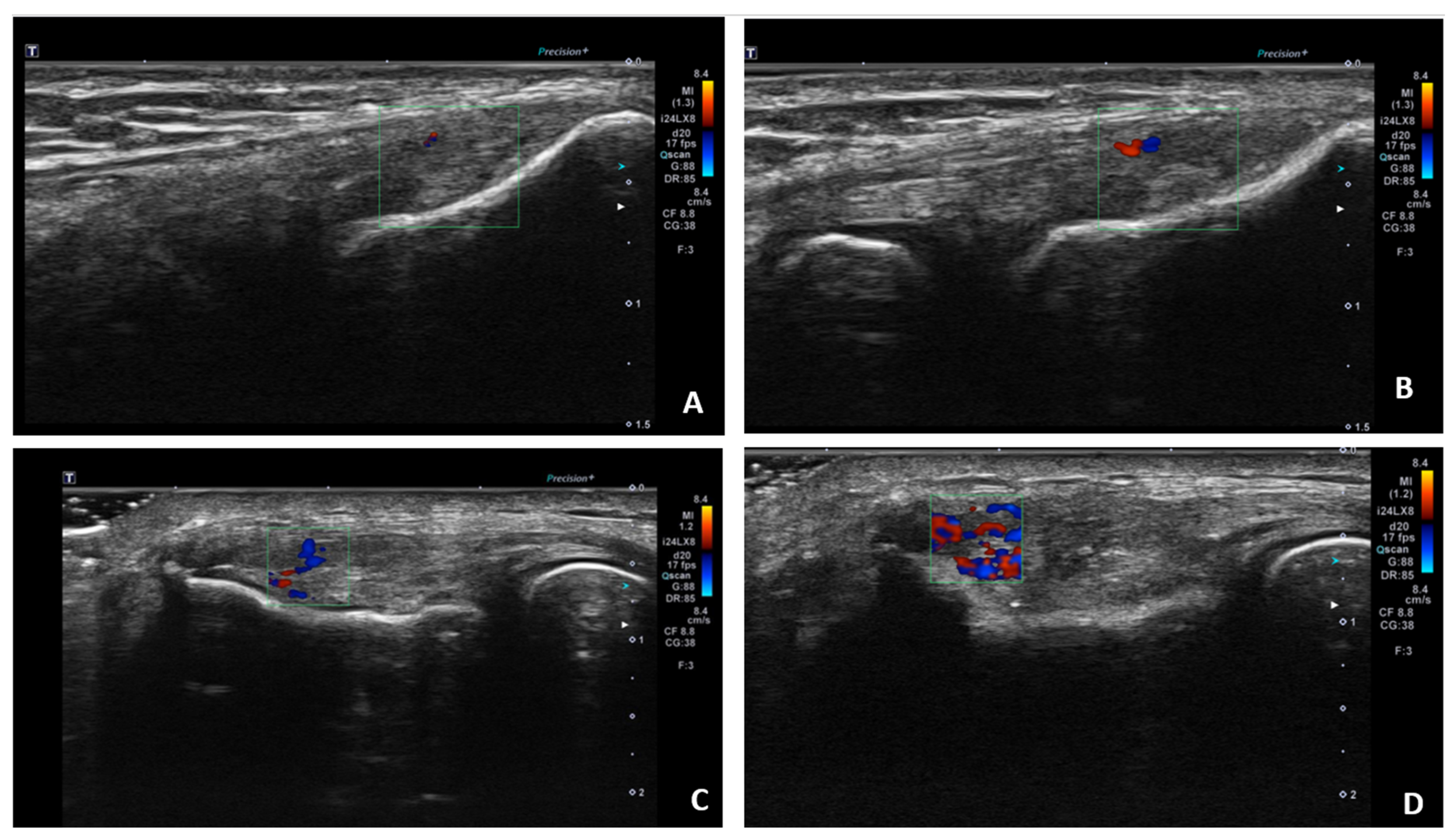

Ultrasound (USG) evaluations were conducted jointly by two specialists following the clinical diagnosis. The physicians performing the USG were blinded to the patients’ clinical outcomes and treatment details. The USG procedure was repeated three months post-treatment. Color Doppler imaging (frame rate 10-15 Hz) and superb microvascular imaging (SMI; frame rate >50 Hz) were performed using the Toshiba Aplio 500 USG system with a high-frequency linear array transducer. Vascular activity on color Doppler imaging was graded on a scale of 0 to 4: Grade 0 = no activity, Grade 1 = single vessel, Grade 2 = Doppler activity <25%, Grade 3 = Doppler activity 25-50%, and Grade 4 = Doppler activity >50%. (

25) (

Figure 2)

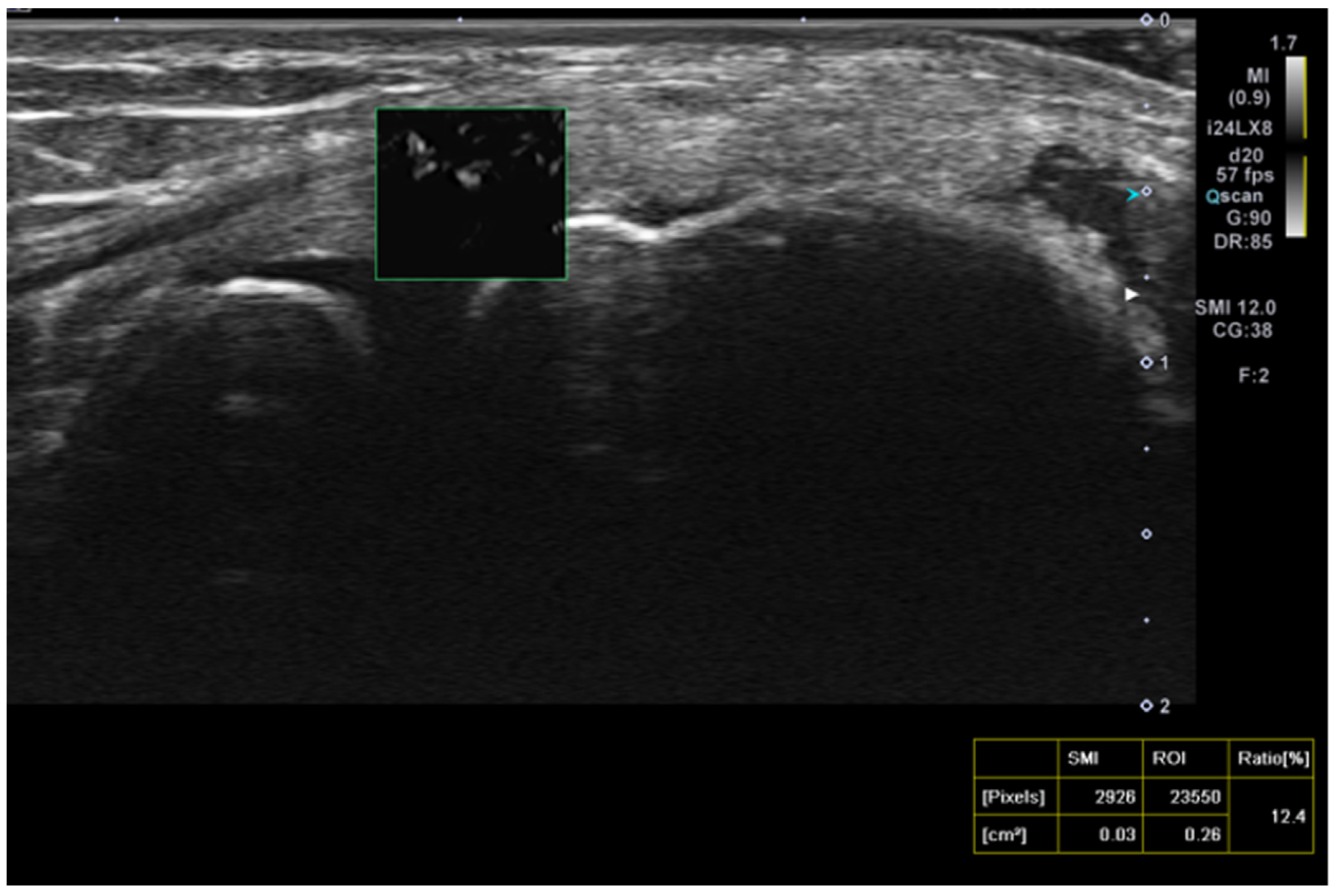

Superb microvascular imaging (SMI) was assessed alongside Doppler ultrasonography (USG) as described in the literature, allowing for a more quantitative evaluation of vascularity.(

4) (

Figure 3).

After selecting eligible patients, randomization was performed using randomization lists generated on the website random.org. Patients diagnosed bilaterally received the same treatment on both sides.

Following treatment allocation, the first group received glucocorticoid injections, the second group received saline injections, and the third group received PRP injections using the peppering technique at the point of maximal tenderness over the lateral epicondyle at the common extensor origin. Vascularity (color Doppler activity) and the superb microvascular imaging (SMI) index were assessed using ultrasonography (USG) before the injections and three months post-injection.

The study was designed as single-blinded. While the physician administering the treatment and the patient were aware of the treatment received, the physicians performing the ultrasonographic evaluations and clinical assessments were blinded to the treatment allocation.

Injections were administered as a single procedure. The lateral epicondyle area was disinfected with sterile iodine prior to all injections, and local anesthesia was not used. The injection volume was standardized to 2 mL for each group. For the PRP group, the CellPhi PRP CP20 (PALMED Health Product Company) kit was utilized. To prepare the PRP, 16.2 mL of the patient’s blood was drawn into a kit tube containing 1.8 mL of sodium citrate and centrifuged at 1890G for 10 minutes to isolate the PRP. A total of 2 mL of the resultant PRP was injected. For the corticosteroid group, a 2 mL solution was prepared by combining 1 mL of betamethasone with 1 mL of bupivacaine hydrochloride. The post-injection protocol was consistent across all patients.

Patients were instructed to minimize the use of the affected arm following the injection and were advised to resume normal activities after 3–4 days, provided their pain was tolerable. Acetaminophen was recommended for pain management if analgesic medication was needed. Additionally, patients were advised to follow a standard stretching exercise protocol for tennis elbow. (11)

Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Personalized Tennis Elbow Evaluation (PRTEE) and Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire (DASH) (9,16) scores were obtained before injection, after 3 months and after 6 months following injection.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22 software. The conformity of variables to a normal distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To evaluate the homogeneity of the study groups prior to treatment, group characteristics were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results

There were no significant differences among the three groups prior to treatment in terms of age (p=0.7), baseline VAS score (p=0.4), baseline DASH score (p=0.5), baseline PRTEE score (p=0.7), vascularity score (p=0.09), or SMI index (p=0.6). Additionally, the chi-square test showed no significant gender differences between the groups at the start of treatment (p=0.5). Based on these results, the groups were determined to be homogeneous before treatment.

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between the SMI index and baseline VAS, DASH, and PRTEE scores. No significant correlations were found between the SMI index and baseline VAS (p=0.4), baseline DASH (p=0.6), or baseline PRTEE scores (p=0.4).

Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between the vascularity score and baseline VAS, DASH, and PRTEE scores. No significant correlations were observed between the vascularity score and baseline VAS (p=0.2), baseline DASH (p=0.5), or baseline PRTEE scores (p=0.2).

The results were evaluated based on the scores at 3 and 6 months. VAS, DASH, and PRTEE scores at both 3 and 6 months were compared among the three study groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed statistically significant differences across all scores between the three groups (p < 0.001 for all scores). Post-hoc analysis was conducted to identify the source of the differences among the groups.

No significant difference was found between the glucocorticoid and PRP groups in the VAS score evaluation at 3 months (p=0.7). However, a significant difference was observed between the glucocorticoid group (4.1 ± 1.6) and the saline group (6.3 ± 2.1) (p=0.02), as well as between the saline group (6.3 ± 2.1) and the PRP group (2.3 ± 2.3) (p<0.001).

In the DASH score evaluation at 3 months, significant differences were observed among all groups. The glucocorticoid group (34.6 ± 13.1) showed a significant difference compared to the PRP group (19.2 ± 11.3) (p=0.002) and the saline group (49.1 ± 8.1) (p=0.003). Additionally, the saline group demonstrated significantly higher scores compared to the PRP group (p<0.001). The PRP group had significantly lower DASH scores at 3 months compared to the other groups, indicating better functional outcomes.

For the PRTEE scores at 3 months, significant differences were observed among all groups. The glucocorticoid group (34.2 ± 9.5) demonstrated significant differences compared to the PRP group (19 ± 11.5) (p=0.001) and the saline group (47.4 ± 8.5) (p=0.003). Additionally, the saline group showed significantly higher scores compared to the PRP group (p<0.001). The PRP group had significantly lower PRTEE scores at 3 months compared to the other groups, indicating better clinical outcomes.

At 6 months, analysis of the VAS scores revealed no significant difference between the glucocorticoid and saline groups (p=0.2). However, significant differences were observed between the glucocorticoid group (4.4 ± 1.9) and the PRP group (1.5 ± 2.2) (p=0.001), as well as between the saline group (5.6 ± 1.7) and the PRP group (p<0.001).

The DASH scores at 6 months showed significant differences among all groups. Comparisons revealed significant differences between the glucocorticoid group (32.6 ± 13.7) and the PRP group (13.7 ± 10.5) (p<0.001), the glucocorticoid group and the saline group (45 ± 9.7) (p=0.001), and the saline group and the PRP group (p<0.001).

Similarly, for PRTEE scores at 6 months, significant differences were observed among all groups. Comparisons showed significant differences between the glucocorticoid group (33.2 ± 12.4) and the PRP group (14.8 ± 11.2) (p<0.001), the glucocorticoid group and the saline group (44.1 ± 6.7) (p=0.003), and the saline group and the PRP group (p<0.001). The PRP group consistently demonstrated significantly lower PRTEE scores at 6 months compared to the other groups, indicating superior clinical outcomes. (

Table 2)

No statistically significant differences were found between the groups in the final vascularity scores (p=0.3) or the final SMI scores (p=0.2). (

Table 3)

Discussion

The PRTEE is a highly specific tool for evaluating lateral epicondylitis. Previous studies have reported that it is practical and valuable for assessing epicondylitis in the Turkish population. (2)

In a randomized controlled study comparing injection therapies for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis, Krogh et al. reported improvements in PRTEE scores across all groups. The PRP group improved from 51 ± 4.3 to 16 ± 4.3, the corticosteroid group improved from 51.8 ± 4.3 to 13.8 ± 4.3, and the saline injection group improved from 47.1 ± 5 to 7.6 ± 4.3. (18) In our study, PRTEE scores improved from 48 ± 8.2 to 19 ± 11.3 in the PRP group, from 46.1 ± 12.4 to 34.6 ± 13.1 in the glucocorticoid group, and from 48.9 ± 8.5 to 47.4 ± 8.5 in the saline group. Due to clinical dissatisfaction with saline injections, 4 patients (4 elbows) withdrew from the study and received alternative treatments (2 PRP and 2 corticosteroid injections). These patients were not included in the final analysis or the ultrasonographic (USG) examination.

Linman et al. conducted a randomized controlled study treating patients with lateral epicondylitis using PRP, saline, and autologous blood injections. At the 3-month follow-up, DASH scores were observed to decrease from 35.6 ± 15.5 to 24 ± 19 in the PRP group and from 37.8 ± 14.8 to 27 ± 18 in the saline group. (21) However, the study by Linman et al. did not include a glucocorticoid group. In our study, DASH scores decreased from 48.3 ± 9.3 to 34.6 in the glucocorticoid group, from 50.84 ± 6.9 to 49.1 ± 8 in the saline group, and from 48 ± 5.6 to 19.2 ± 11 in the PRP group at the 3-month follow-up. Similarly, in a randomized controlled study comparing PRP and corticosteroids, Gautam et al. reported a decrease in DASH scores from 69.7 ± 6.1 to 33.6 ± 5.1 in the PRP group and from 67.5 ± 6.9 to 34.3 ± 3.3 in the corticosteroid group. (13)

In both studies mentioned above, improvements in clinical scores were observed at the 3-month follow-up; however, the baseline severity of symptoms differed. In our study, the initial DASH scores were more moderate, and the 3-month results were consistent with findings reported in the literature.

In our study, the PRP group demonstrated a decrease in VAS scores, used to evaluate pain, from 6.5 to 2.3 at 3 months. Similarly, Morella et al. reported an improvement in VAS scores from 7.6 to 1.5, Thanasas et al. from 6.1 to 1.9, and Linnanmaki et al. from 5.7 to 4.3. (24, 21, 32) Linnanmaki et al. utilized leukocyte-poor PRP, whereas our study employed leukocyte-rich PRP, which we believe may have influenced the clinical outcomes. In the corticosteroid group, the mean VAS score decreased from 6.1 to 4.1 at 3 months but increased to 4.4 at 6 months. In contrast, the PRP group demonstrated a VAS score of 1.5 at 6 months. This may reflect the short-term effectiveness of glucocorticoids, while PRP provides a more sustained therapeutic effect over a longer period.(5)

In our study, the follow-up of epicondylitis treatment was conducted using Doppler ultrasonography (USG) and superb microvascular imaging (SMI). We did not employ other methods, such as tendon thickness measurement or USG elastography, which have been described in the literature. Previous studies have reported that tendon thickness may vary between individuals and may not show significant changes in the early and mid-term follow-up periods. (8, 33)

The mean Doppler USG grades at baseline were 2.9 ± 1.1 in the PRP group, 1.9 ± 1.5 in the saline group, and 2.2 ± 1.4 in the glucocorticoid group, which decreased to 2.1 ± 1.4, 1.7 ± 1.4, and 1.4 ± 1, respectively, after treatment. These changes showed no correlation with clinical score improvements. Consequently, we utilized the SMI method, which is more sensitive and specific than Doppler USG grading for lateral epicondylitis, providing a more accurate demonstration of vascularity at the myotendinous junction.(4)

In our study, the SMI technique was utilized for the first time in the follow-up after injection, differing from previous literature. The percentage change in SMI measurements was not significant among the glucocorticoid (9.8 ± 7.8 from 9.8 ± 9.3), saline (10.24 ± 8.4 from 9.3 ± 7.5), and PRP (7.06 ± 6.6 from 12.4 ± 6.9) groups.

Unlike our study, Chaundry et al. utilized contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (USG) to evaluate the effects of PRP in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis. They performed USG evaluations at 1 and 6 months post-PRP injection in six patients with an average age of 50 years and reported improvements in tendon morphology and increased vascularity between the 1st and 6th months. Similarly, Fredberg et al. demonstrated the vascularity-reducing effects of corticosteroids on the Achilles and patellar tendons.12 Krogh et al. further observed a decrease in vascularity on Doppler imaging after saline and glucocorticoid injections, while an increase in vascularity was noted following PRP injections.18

Limitations

Our study was originally designed to last for one year; however, it was terminated at the 6-month mark due to the persistence of complaints in the saline treatment group and to prevent crossover between groups. Additionally, we suspect that patients’ awareness of their treatment type may have influenced their clinical scores. Furthermore, the absence of ultrasonographic (USG) guidance during injections may have impacted the results.

Conclusions

Upon analyzing our results, PRP treatment demonstrated superior outcomes, while the results of saline injections, which have been used as both a primary treatment in some studies and a placebo in others, appear less favorable in the early and mid-term. Additionally, the use of ultrasonography (USG) for follow-up in the early and mid-term may have limited clinical significance. However, USG, commonly utilized for diagnostic purposes, could be more beneficial for follow-up evaluations in later periods. Double-blind, randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes are needed to provide more robust clinical and radiological data for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis.

Author Contributions

Taha Kizilkurt, M.D., and Ahmet Serhat Aydin, M.D., conceptualized and designed the study. Taha Furkan Yagci, M.D., and Ali Ersen, M.D., contributed to patient recruitment and data collection. Celal Caner Ercan, M.D., and Artür Salmaslioglu, M.D., performed ultrasonographic evaluations and radiological analyses. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation, data interpretation, and approval of the final version for submission.

Funding

The authors declare that no external funding was received for this study. The research was conducted using institutional resources and was not influenced by any financial support from external organizations.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine (Approval No: 10180). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their enrollment in the study. Participants were fully informed about the study objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits, and they retained the right to withdraw at any time without consequence.

Consent for Publication

All participants provided written informed consent for the publication of their anonymized data in scientific journals. The authors confirm that no identifying information of individual participants is included in the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff and researchers at Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine for their valuable assistance during patient recruitment, data collection, and technical support. We also extend our gratitude to the participants for their time and commitment to this research.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests related to this study.

References

- Alizadehkhaiyat, O.; Fisher, A.C.P.; Kemp, G.J.M.; Frostick, S.P.M. Pain, Functional Disability, and Psychologic Status in Tennis Elbow. Clin. J. Pain 2007, 23, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altan, L.; Ercan, I.; Konur, S. Reliability and validity of Turkish version of the patient rated tennis elbow evaluation. Rheumatol. Int. 2009, 30, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arirachakaran, A.; Sukthuayat, A.; Sisayanarane, T.; Laoratanavoraphong, S.; Kanchanatawan, W.; Kongtharvonskul, J. Platelet-rich plasma versus autologous blood versus steroid injection in lateral epicondylitis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2015, 17, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S.; Karahan, A.Y.; Oncu, F.; Bakdik, S.; Durmaz, M.S.; Tolu, I. Diagnostic Performance of Superb Microvascular Imaging and Other Sonographic Modalities in the Assessment of Lateral Epicondylosis. J. Ultrasound Med. 2017, 37, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Nafa, W.; Munro, W. The effect of corticosteroid versus platelet-rich plasma injection therapies for the management of lateral epicondylitis: A systematic review. SICOT-J 2018, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisset, L.; Beller, E.; Jull, G.; Brooks, P.; Darnell, R.; Vicenzino, B. Mobilisation with movement and exercise, corticosteroid injection, or wait and see for tennis elbow: randomised trial. BMJ 2006, 333, 939–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, A.L.; Scott, M.T.; Dalwadi, P.P.; Mautner, K.; Mason, R.A.; Gottschalk, M.B. Platelet-rich plasma versus Tenex in the treatment of medial and lateral epicondylitis. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2019, 28, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, S.; de La Lama, M.; Adler, R.S.; Gulotta, L.V.; Skonieczki, B.; Chang, A.; Moley, P.; Cordasco, F.; Hannafin, J.; Fealy, S. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: sonographic assessment of tendon morphology and vascularity (pilot study). Skelet. Radiol. 2012, 42, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DÜGER T, Yakut E, ÖKSÜZ Ç, et al. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) Questionnaire. Turkish Journal of Physiotherapy Rehabilitation-Fizyoterapi Rehabilitasyon. 2006;17(3).

- Foster TE, Puskas BL, Mandelbaum BR, Gerhardt MB, Rodeo SA. Platelet-rich plasma: from basic science to clinical applications. The American journal of sports medicine. 2009;37(11):2259-2272.

- Record #265 is using an undefined reference type. If you are sure you are using the correct reference type, the template for that type will need to be set up in this output style.

- Fredberg U, Bolvig L, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, et al. Ultrasonography as a tool for diagnosis, guidance of local steroid injection and, together with pressure algometry, monitoring of the treatment of athletes with chronic jumper’s knee and Achilles tendinitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology. 2004;33(2):94-101.

- Gautam, V.; Verma, S.; Batra, S.; Bhatnagar, N.; Arora, S. Platelet-Rich Plasma versus Corticosteroid Injection for Recalcitrant Lateral Epicondylitis: Clinical and Ultrasonographic Evaluation. J. Orthop. Surg. 2015, 23, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanzmann MC, Audigé L. Platelet-rich plasma for chronic lateral epicondylitis: is one injection sufficient? Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2015;135:1637-1645.

- Gosens T, Peerbooms JC, van Laar W, den Oudsten BL. Ongoing positive effect of platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection in lateral epicondylitis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial with 2-year follow-up. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011;39(6):1200-1208.

- Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG). Am J Ind Med. 1996;29(6):602-608.

- Karjalainen, T.V.; Silagy, M.; O'Bryan, E.; Johnston, R.V.; Cyril, S.; Buchbinder, R. Autologous blood and platelet-rich plasma injection therapy for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, T.P.; Fredberg, U.; Stengaard-Pedersen, K.; Christensen, R.; Jensen, P.; Ellingsen, T. Treatment of Lateral Epicondylitis With Platelet-Rich Plasma, Glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Sports Med. 2013, 41, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.H.; Cha, J.G.; Jin, W.; Kim, B.S.; Park, J.S.; Lee, H.K.; Hong, H.S. Utility of Sonographic Measurement of the Common Tensor Tendon in Patients With Lateral Epicondylitis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 196, 1363–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehr, R. Sixteen S-squared over D-squared: A relation for crude sample size estimates. Statistics in medicine. 1992;11(8):1099-1102.

- Linnanmäki, L.; Kanto, K.; Karjalainen, T.; Leppänen, O.V.; Lehtinen, J. Platelet-rich Plasma or Autologous Blood Do Not Reduce Pain or Improve Function in Patients with Lateral Epicondylitis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2020, 478, 1892–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.-L.; Wang, H.-Q. Management of Lateral Epicondylitis: A Narrative Literature Review. Pain Res. Manag. 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocca, A.D.; McCarthy, M.B.R.; Intravia, J.; Beitzel, K.; Apostolakos, J.; Cote, M.P.; Bradley, J.; Arciero, R.A. An In Vitro Evaluation of the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Platelet-Rich Plasma, Ketorolac, and Methylprednisolone. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2013, 29, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merolla, G.; Dellabiancia, F.; Ricci, A.; Mussoni, M.P.; Nucci, S.; Zanoli, G.; Paladini, P.; Porcellini, G. Arthroscopic Debridement Versus Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection: A Prospective, Randomized, Comparative Study of Chronic Lateral Epicondylitis With a Nearly 2-Year Follow-Up. 2017; 33, 1320–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.T.; Shapiro, M.A.; Schultz, E.; Kalish, P.E. Comparison of sonography and MRI for diagnosing epicondylitis. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2002, 30, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peerbooms JC, Sluimer J, Bruijn DJ, Gosens T. Positive effect of an autologous platelet concentrate in lateral epicondylitis in a double-blind randomized controlled trial: platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection with a 1-year follow-up. The American journal of sports medicine. 2010;38(2):255-262.

- Sampson, S.; Gerhardt, M.; Mandelbaum, B. Platelet rich plasma injection grafts for musculoskeletal injuries: a review. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2008, 1, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, R.; Viikari-Juntura, E.; Varonen, H.; Heliövaara, M. Prevalence and Determinants of Lateral and Medial Epicondylitis: A Population Study. Am. J. Epidemiology 2006, 164, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simental-Mendía, M.; Vilchez-Cavazos, F.; Álvarez-Villalobos, N.; Blázquez-Saldaña, J.; Peña-Martínez, V.; Villarreal-Villarreal, G.; Acosta-Olivo, C. Clinical efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 39, 2255–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, S.E.G.; Miller, K.; Elfar, J.C.; Hammert, W.C. Non-Surgical Treatment of Lateral Epicondylitis: A Aystematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. HAND 2014, 9, 419–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidt, N.; Assendelft, W.; Arola, H.; Malmivaara, A.; Green, S.; Buchbinder, R.; van der Windt, D.; Bouter, L. Effectiveness of physiotherapy for lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review. Ann. Med. 2003, 35, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanasas C, Papadimitriou G, Charalambidis C, Paraskevopoulos I, Papanikolaou A. Platelet-rich plasma versus autologous whole blood for the treatment of chronic lateral elbow epicondylitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011;39(10):2130-2134.

- Toprak, U.; Baskan, B.; Ustuner, E.; Oten, E.; Altin, L.; Karademir, M.A.; Bodur, H. Common extensor tendon thickness measurements at the radiocapitellar region in diagnosis of lateral elbow tendinopathy. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2012, 18, 566–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker-Bone, K.; Palmer, K.T.; Reading, I.; Coggon, D.; Cooper, C. Occupation and epicondylitis: a population-based study. Rheumatology 2011, 51, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).