Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

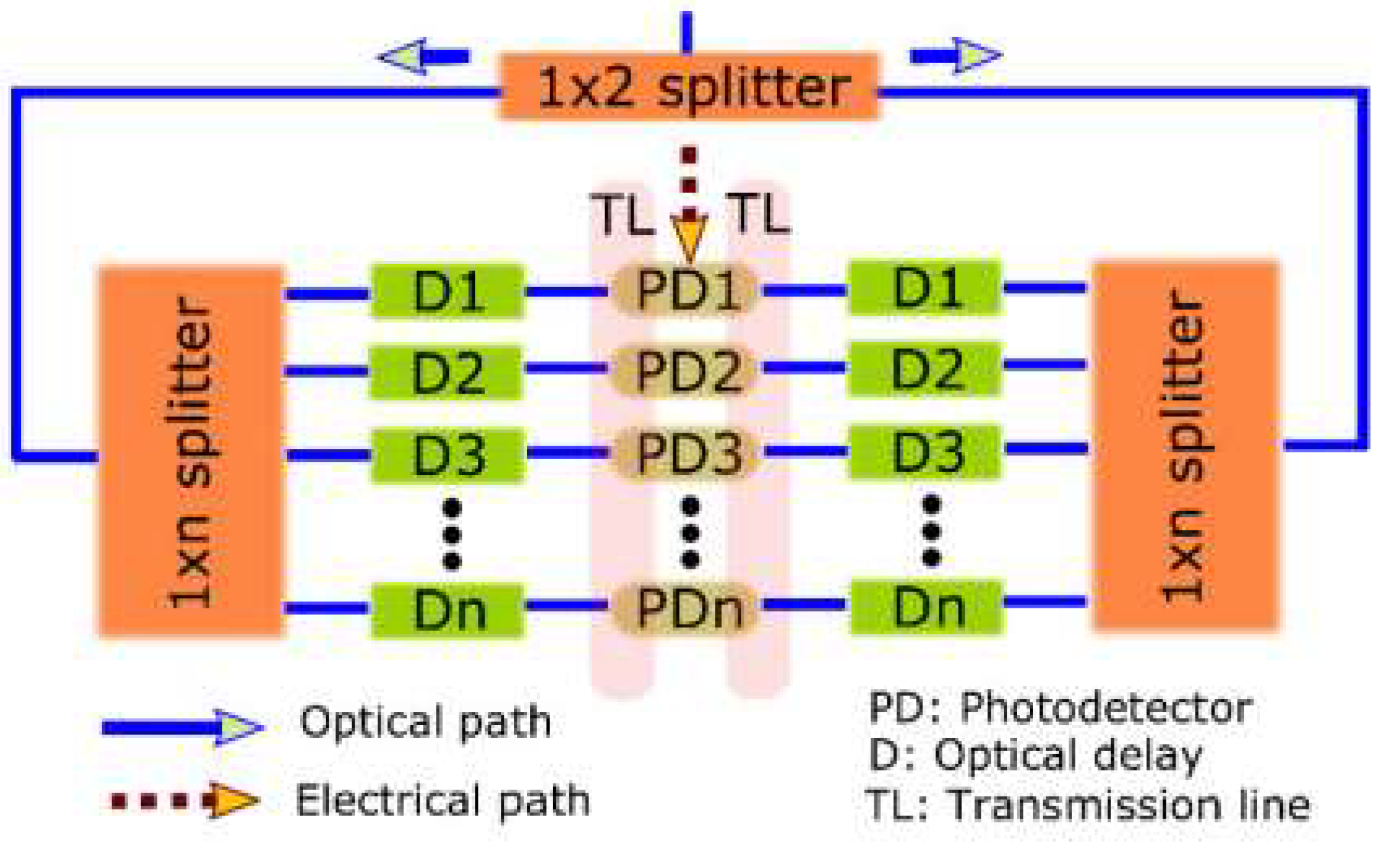

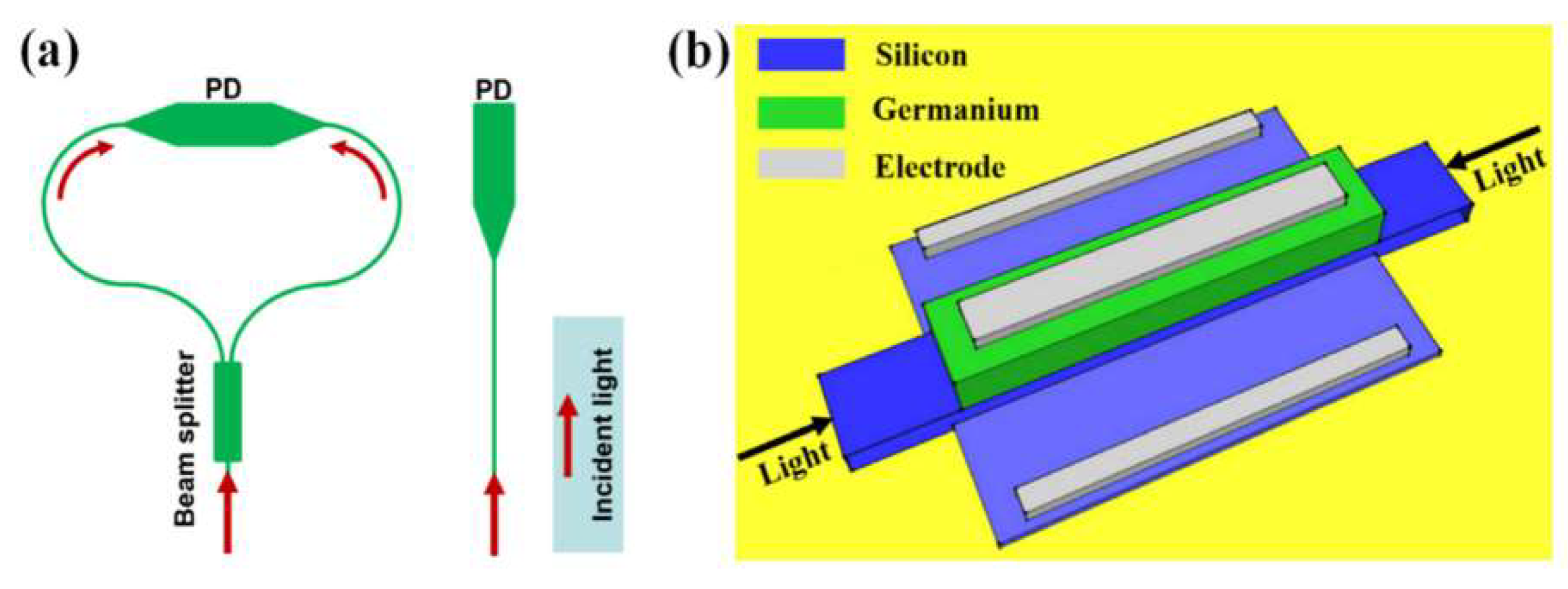

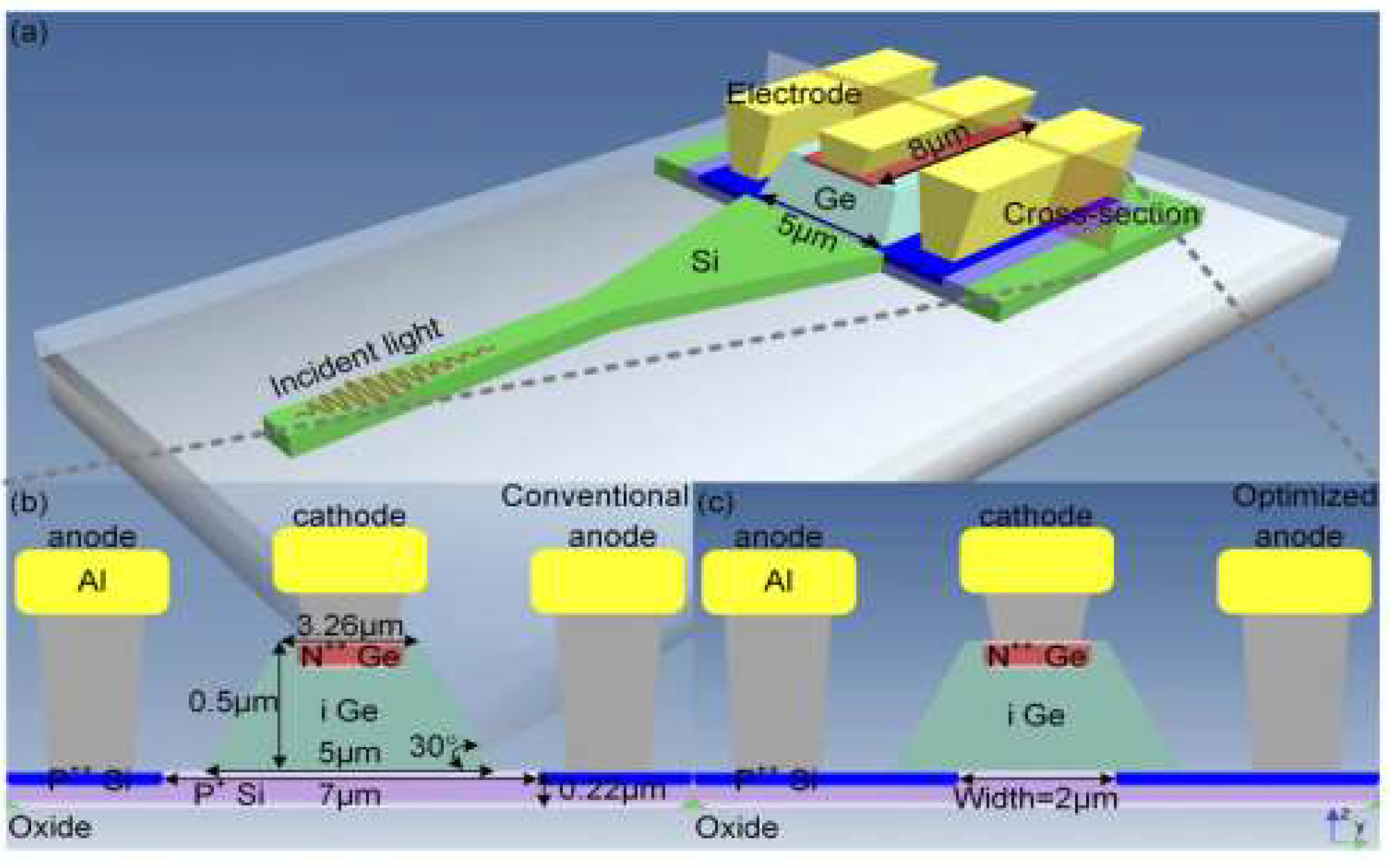

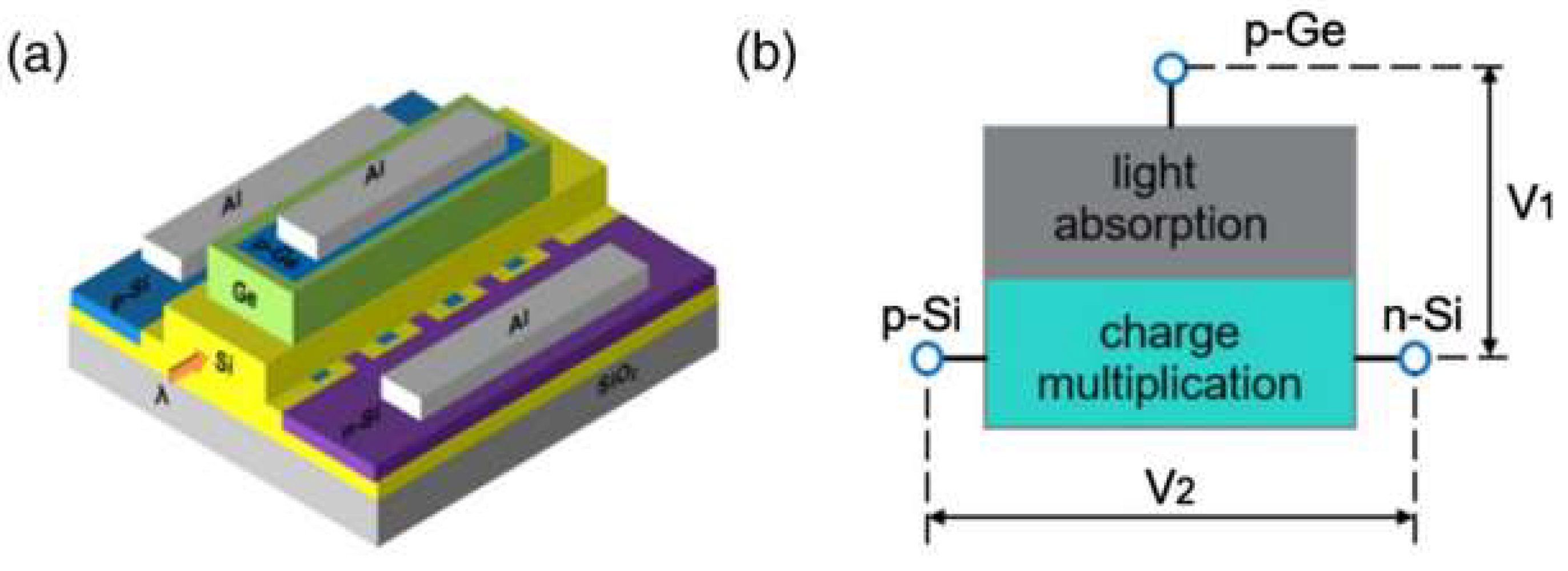

2. High-Power and High-Speed RF Photodiodes

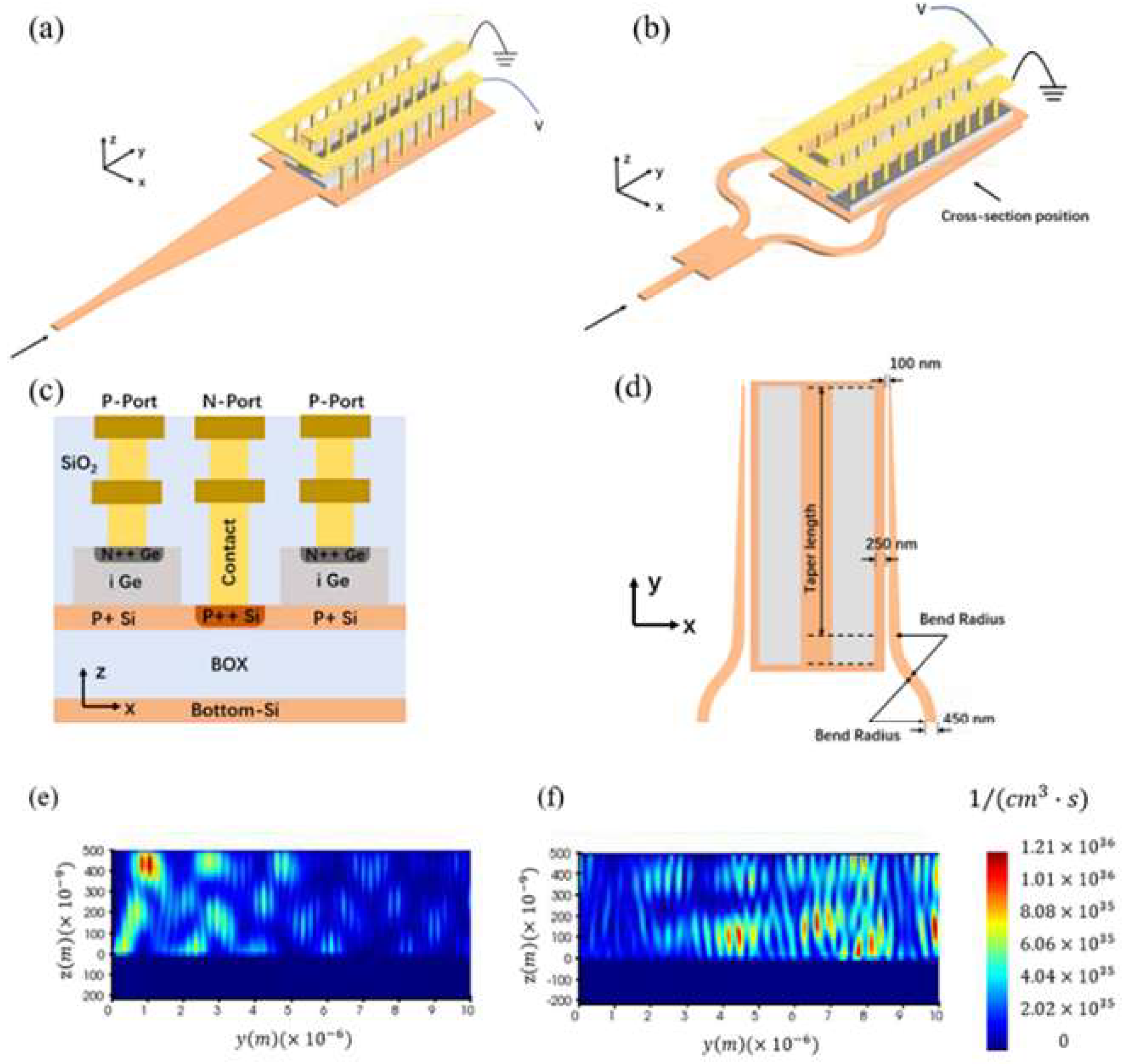

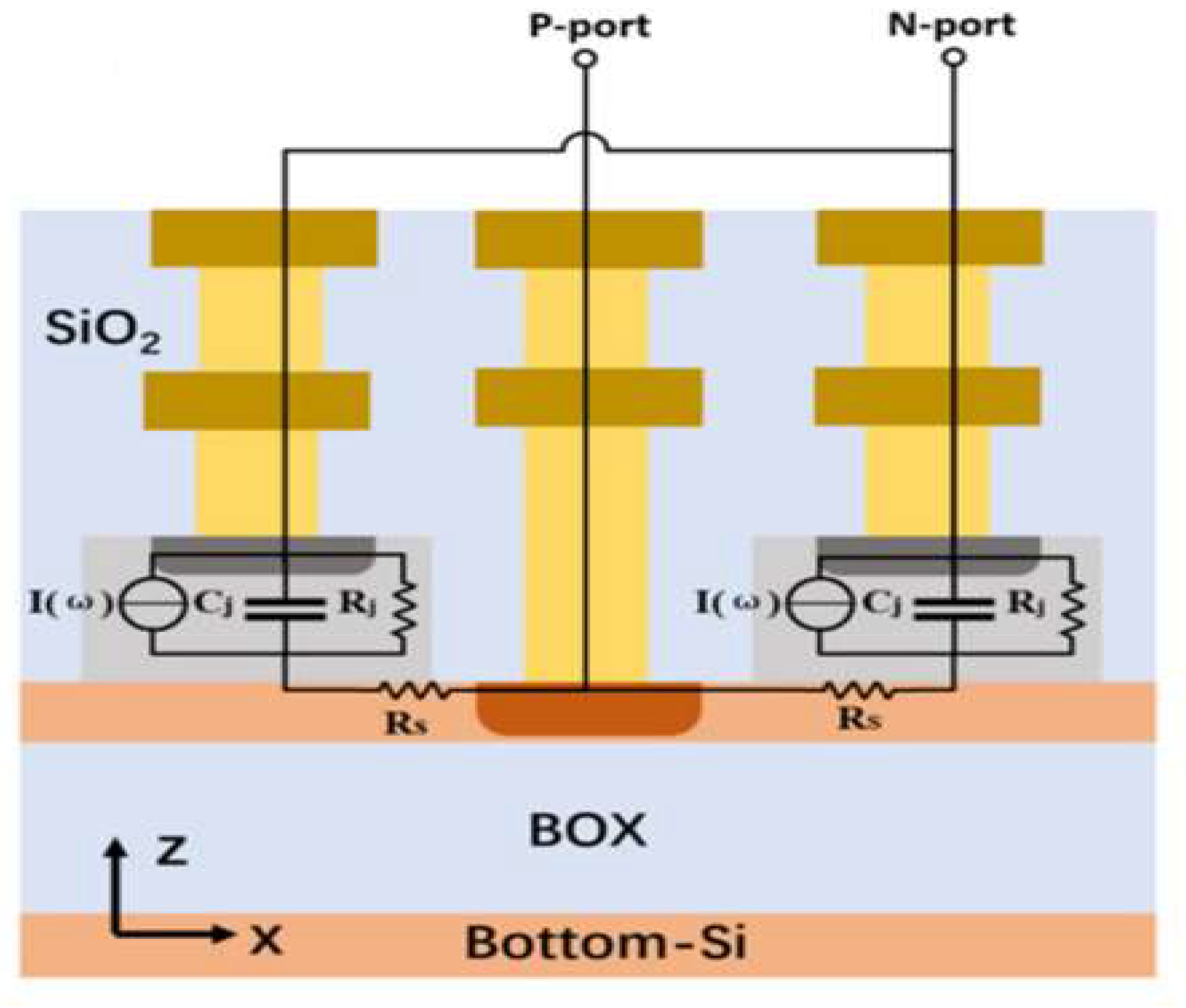

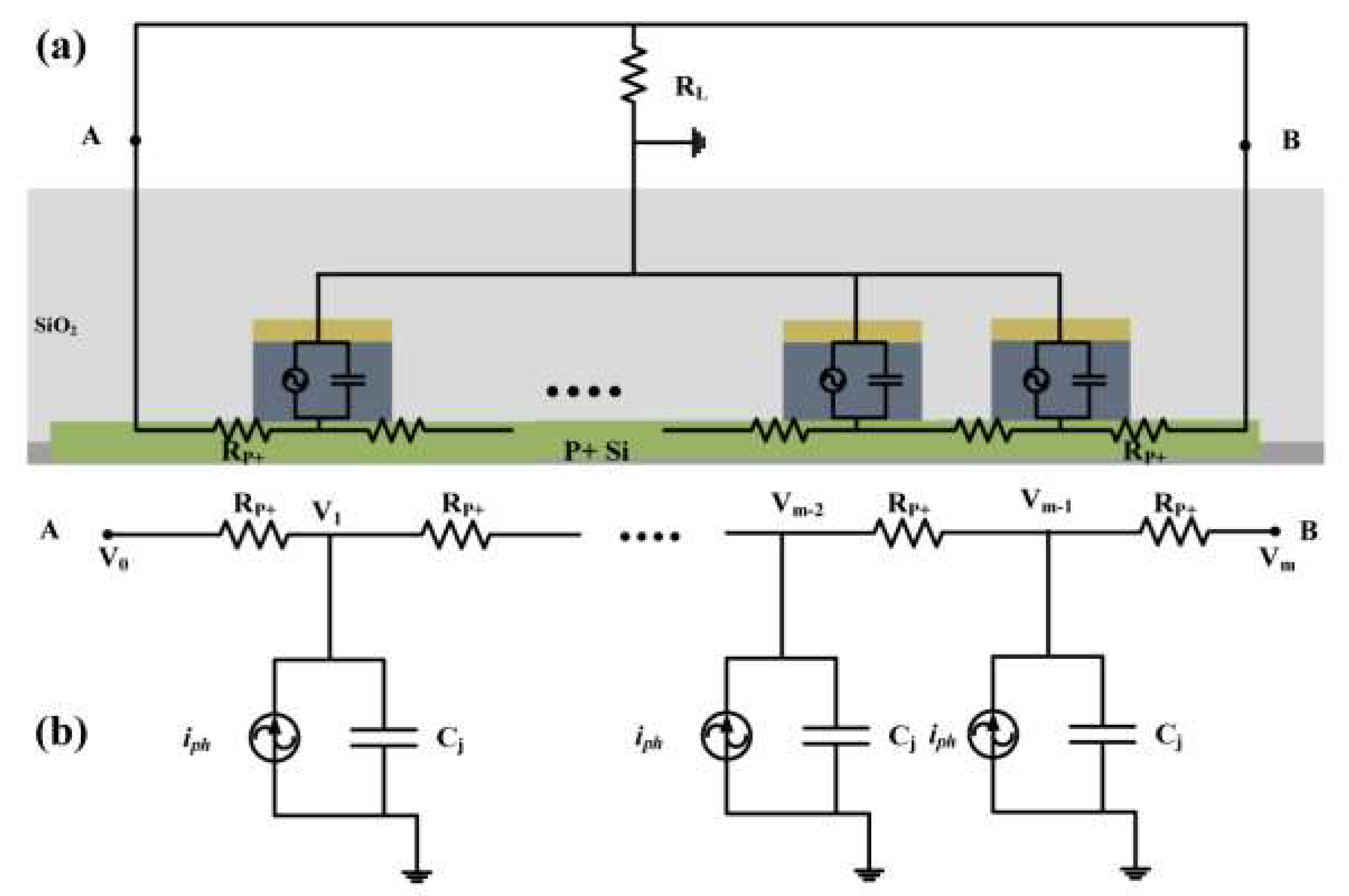

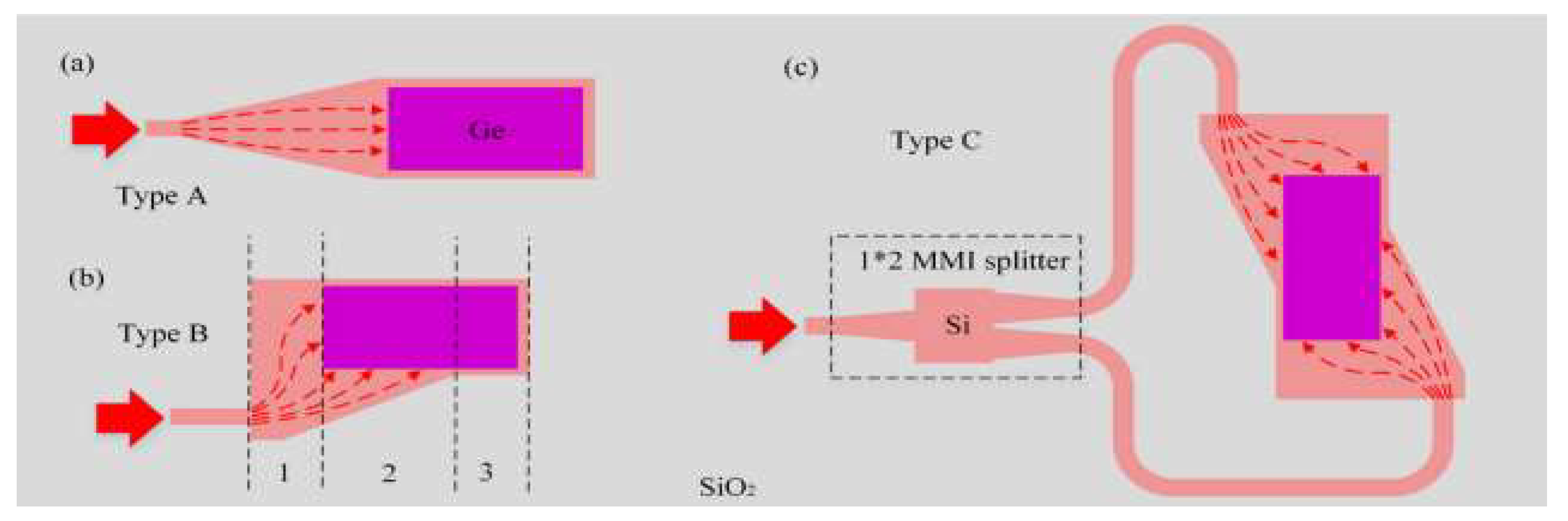

2.1. Photodiode Principle and Structures

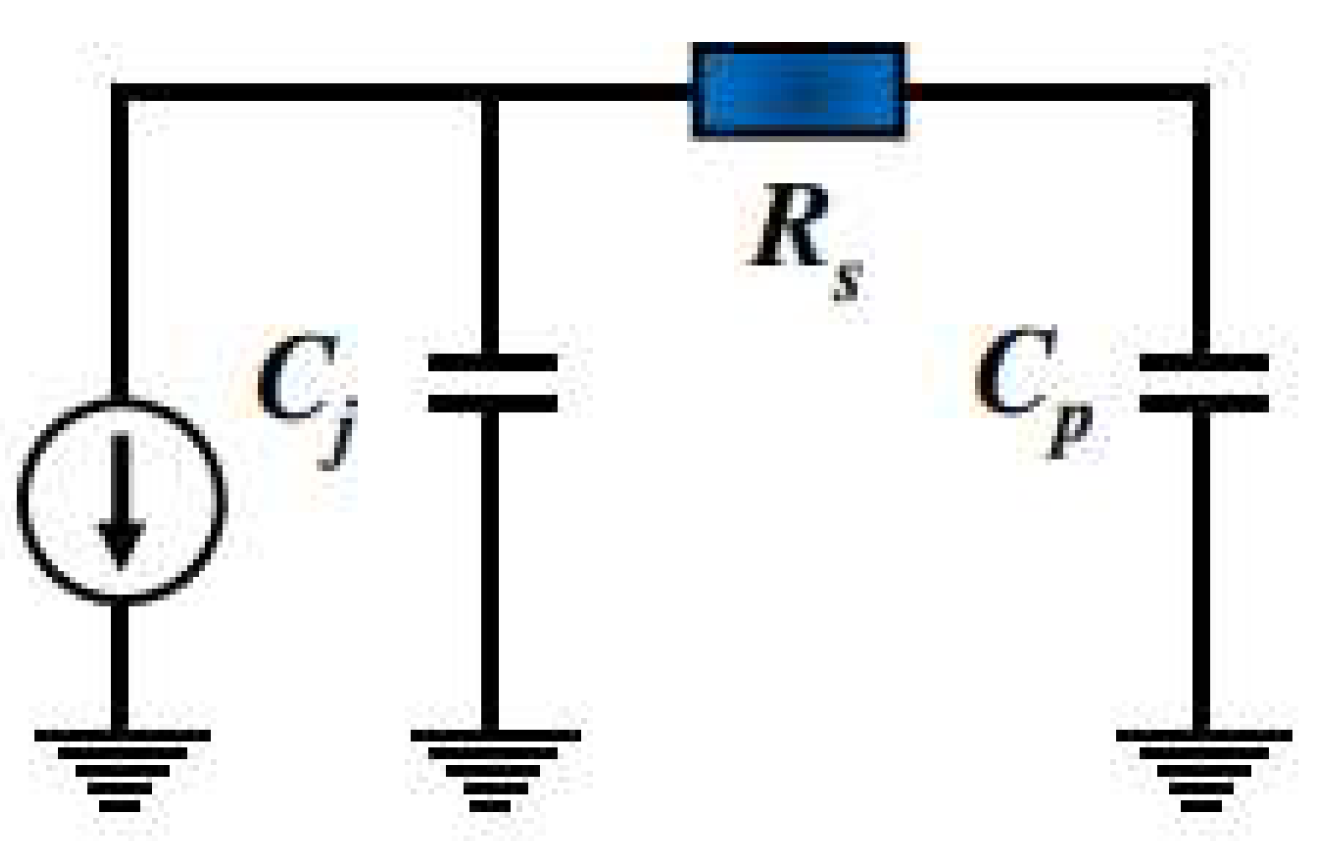

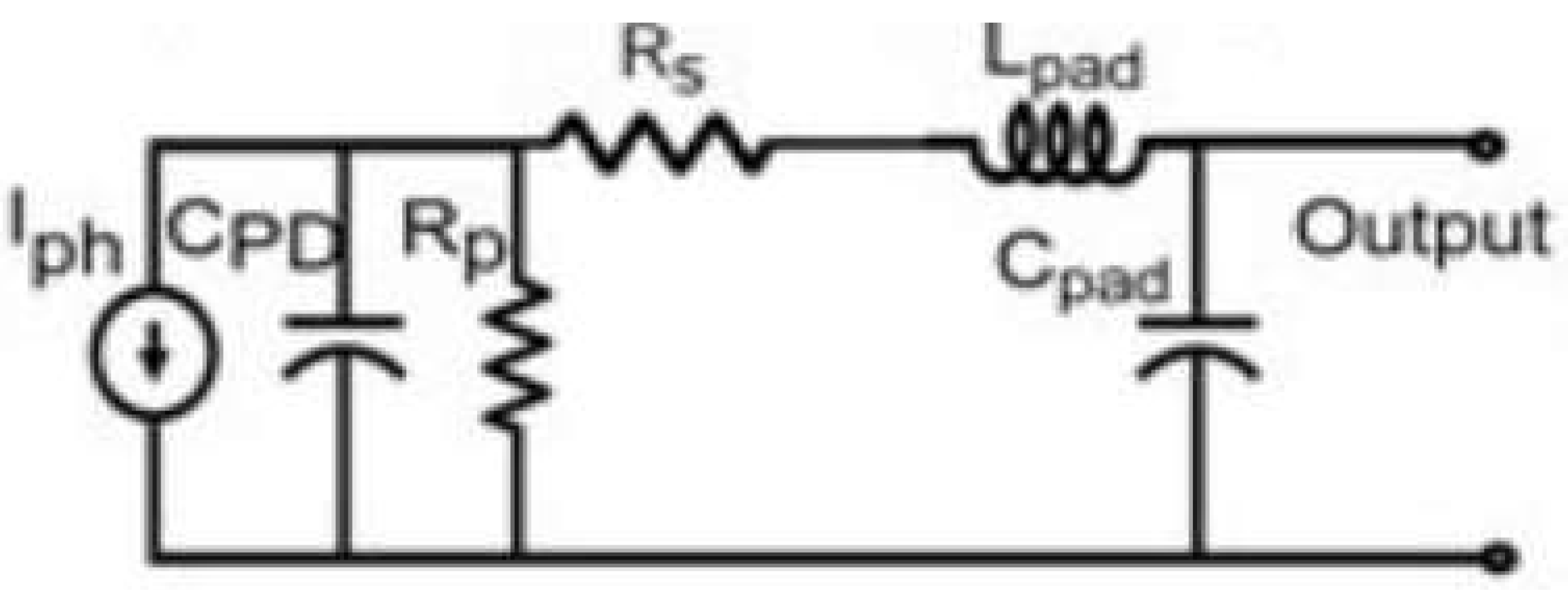

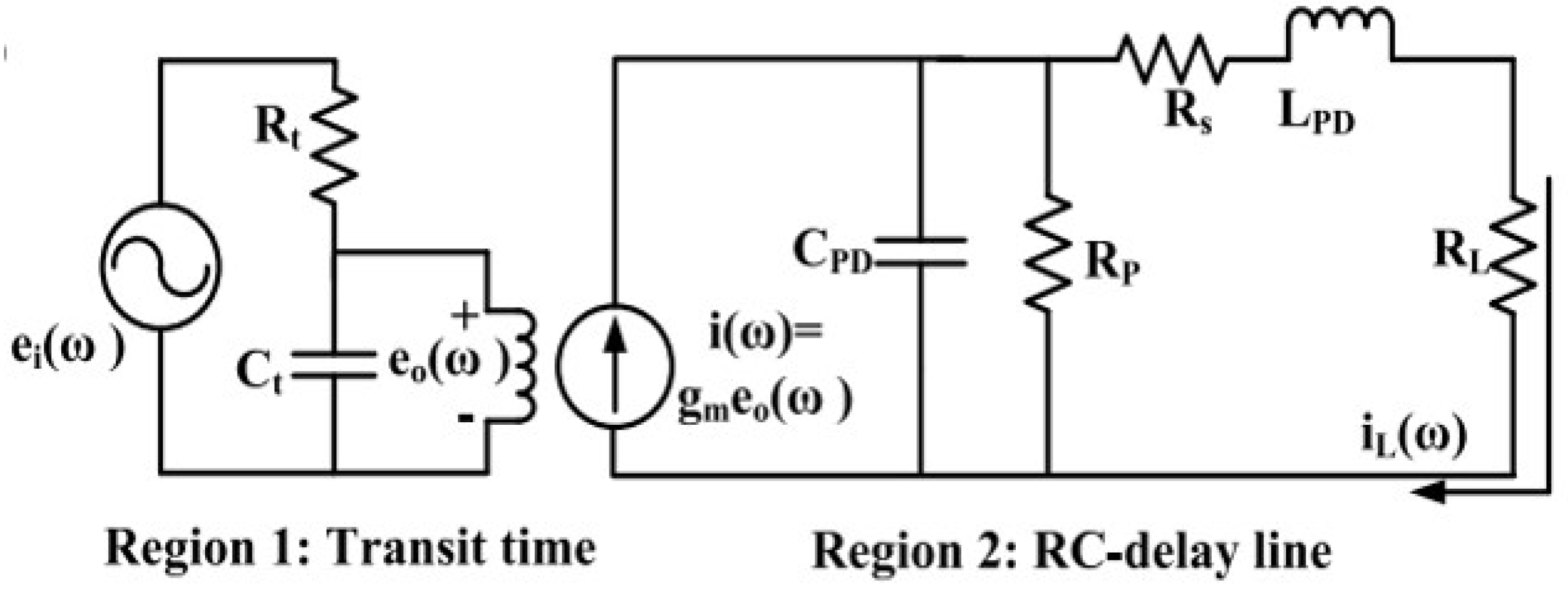

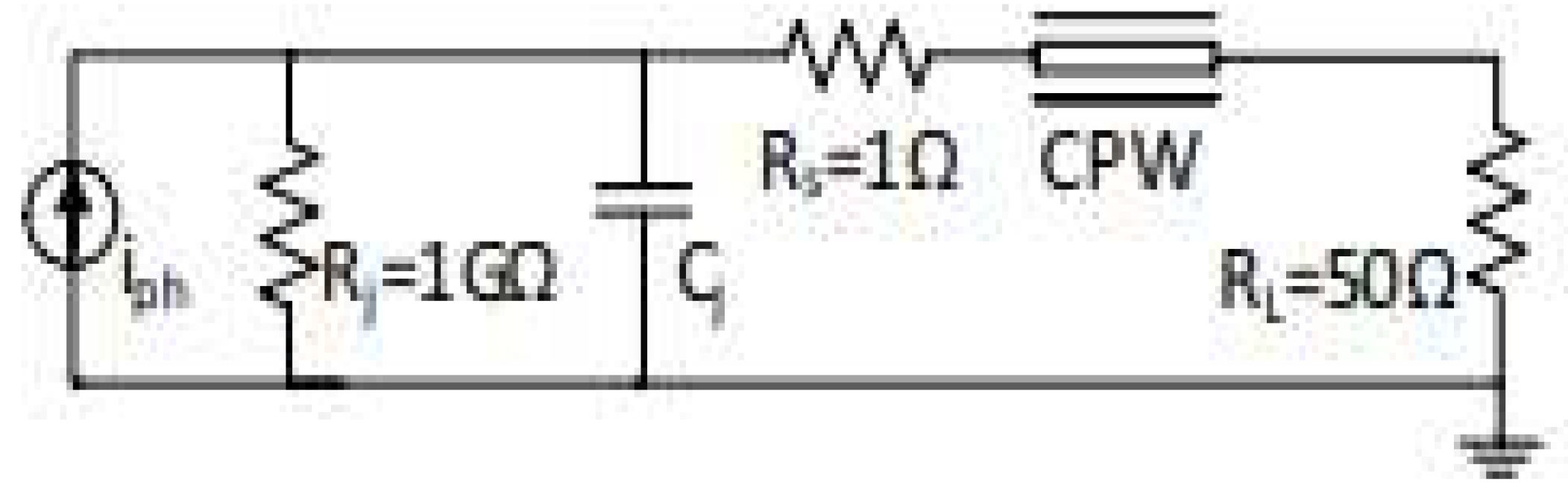

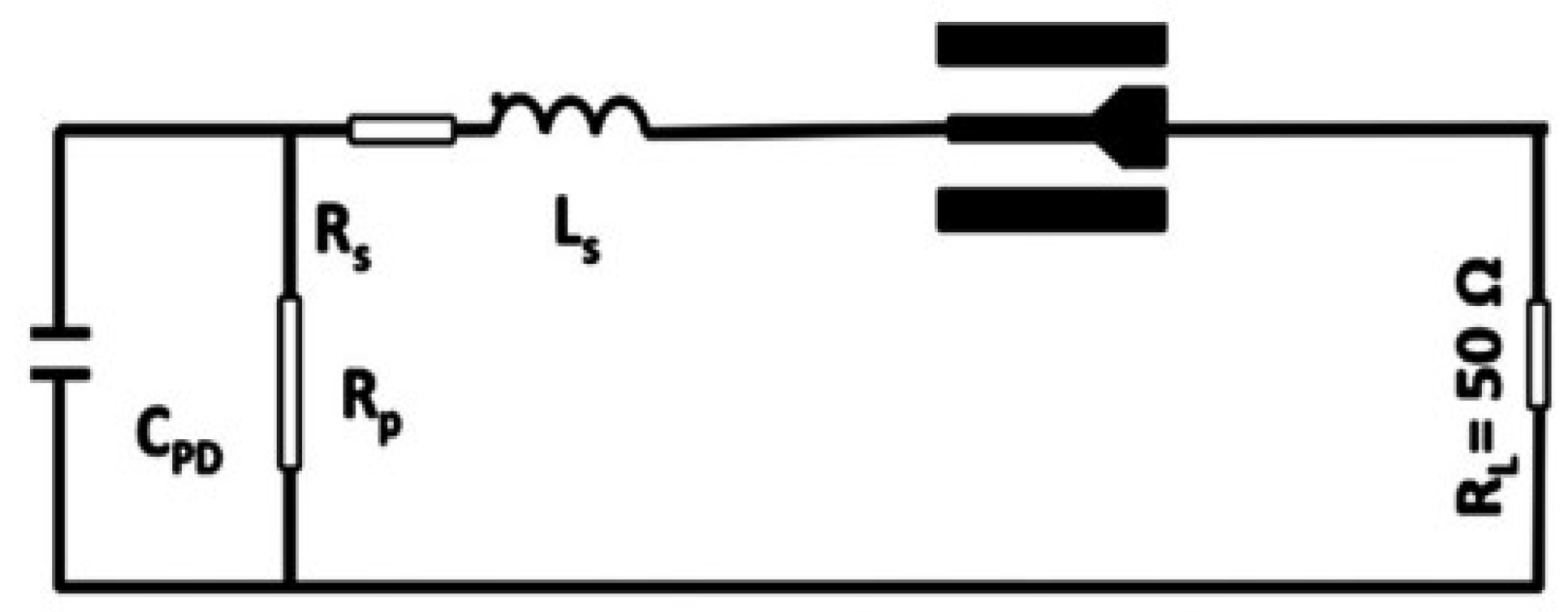

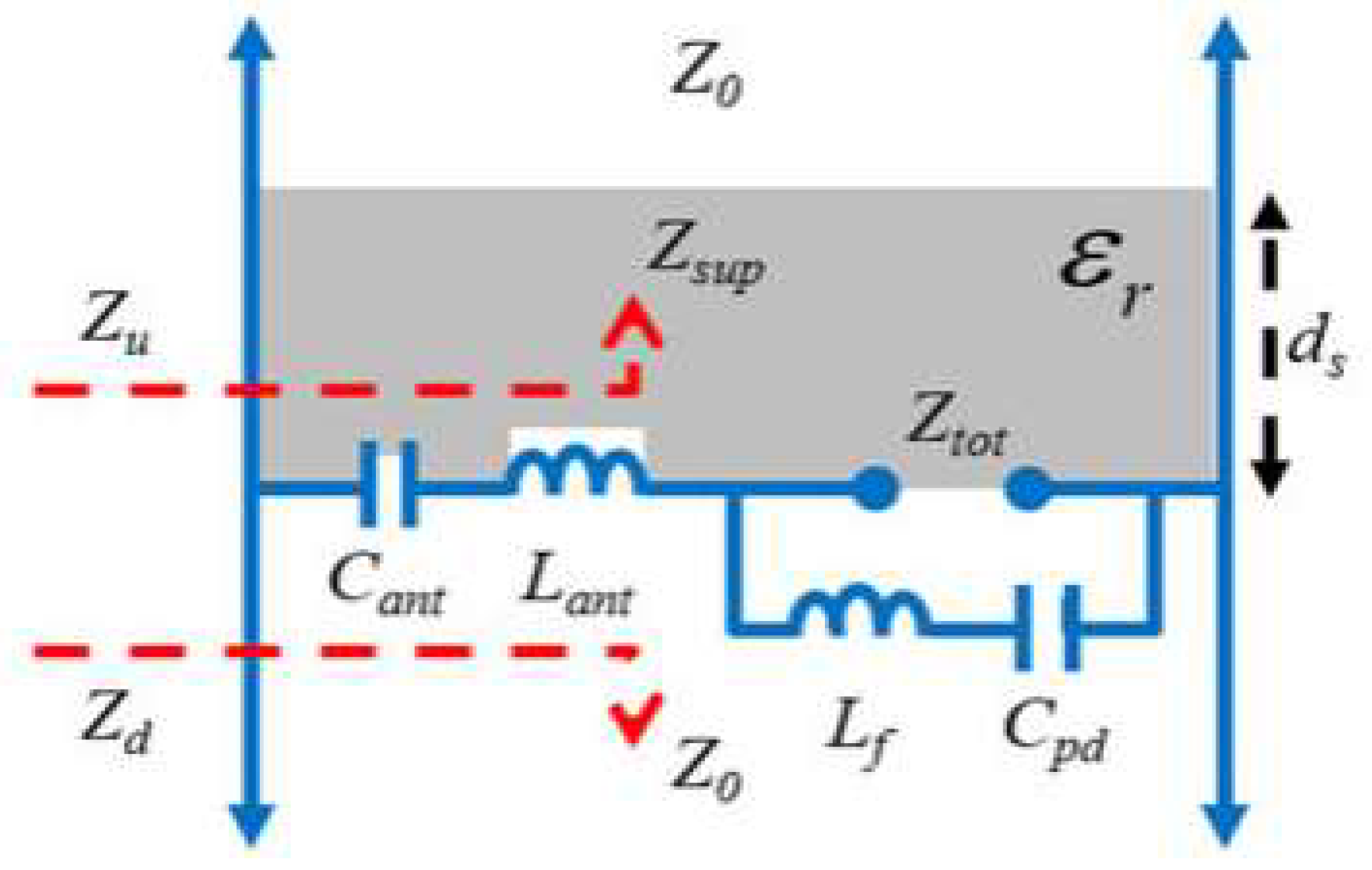

2.2. Photodiode Equivalent Circuit Models

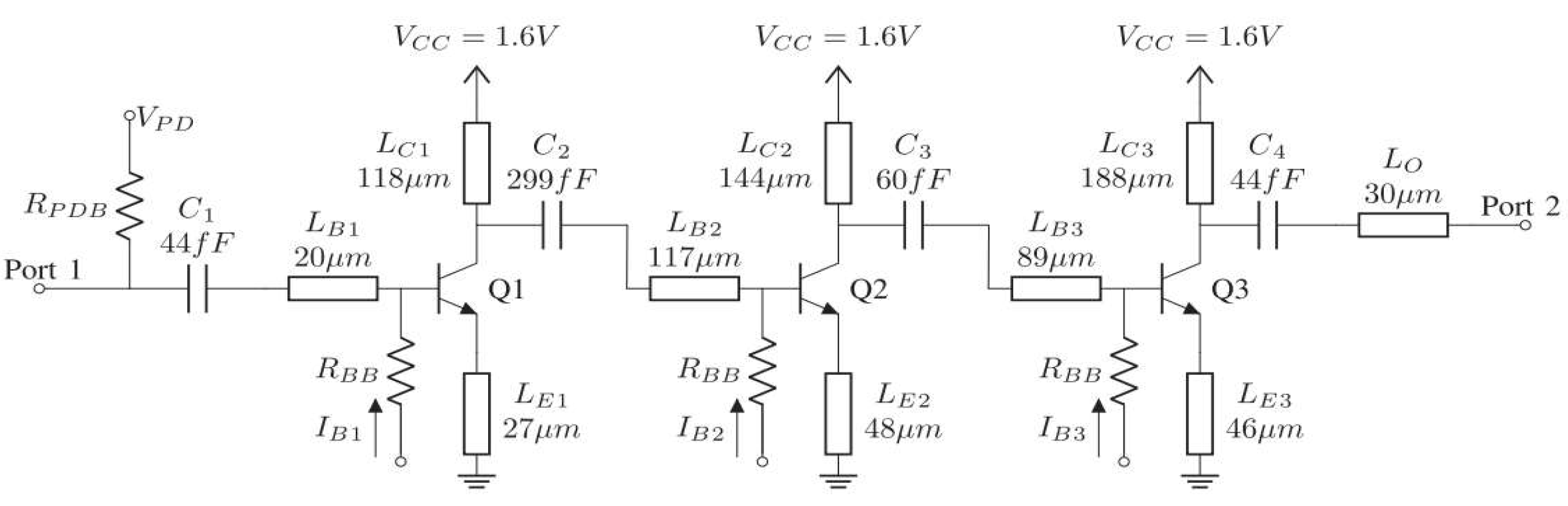

2.3. Photodiode Bandwidth Design

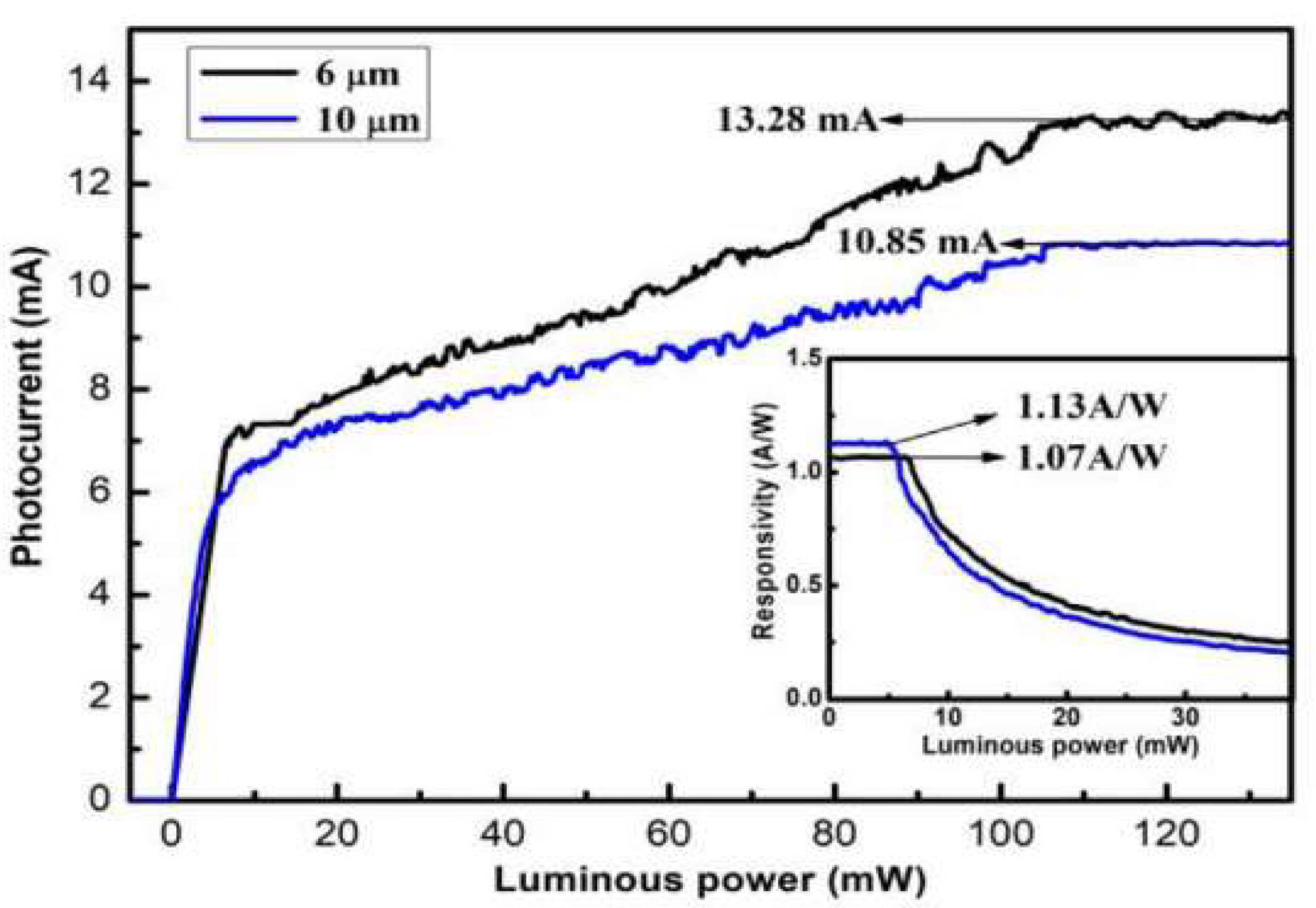

2.4. Photodiode Saturation Current and RF Power

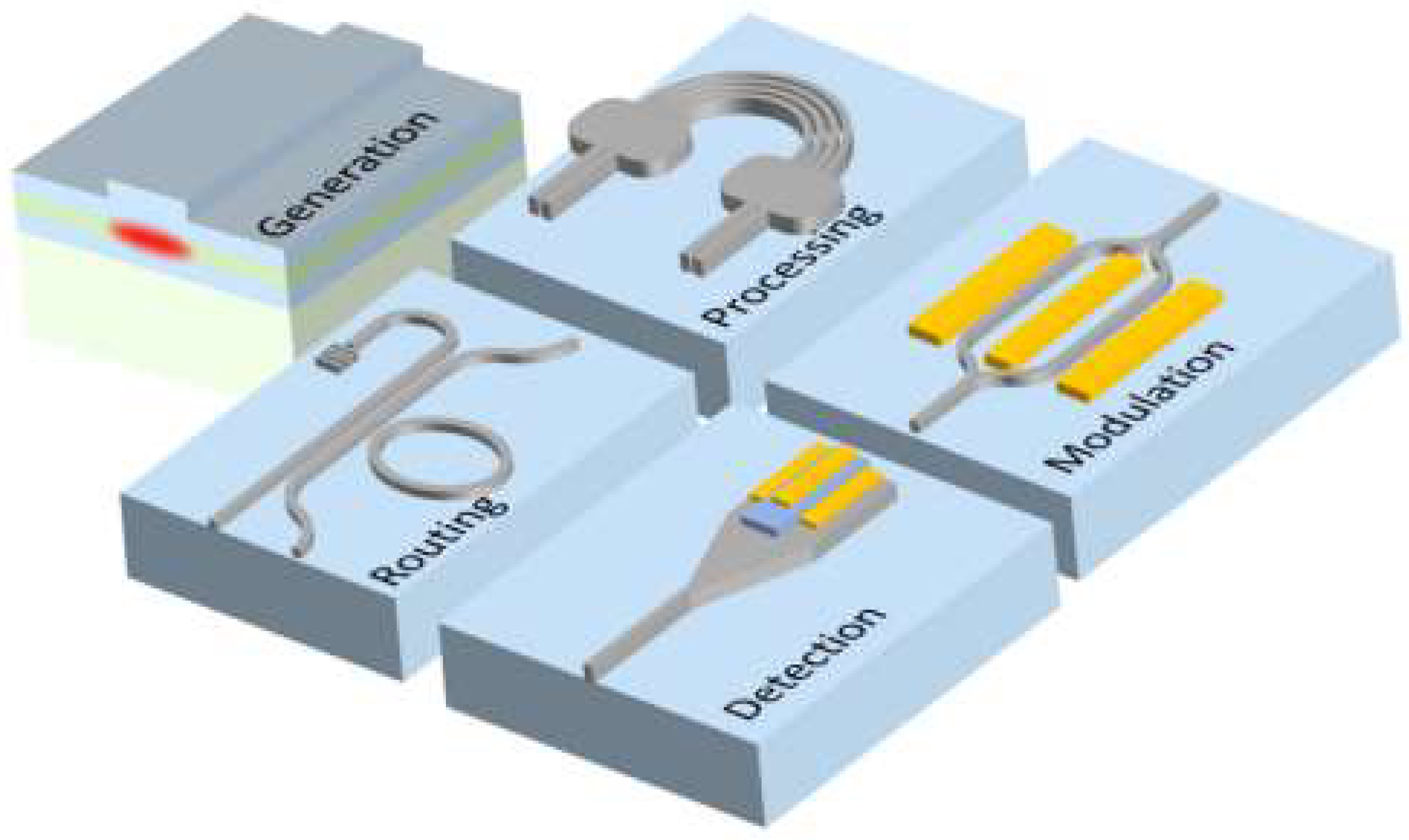

3. Photodiode Integrated Photonic Applications

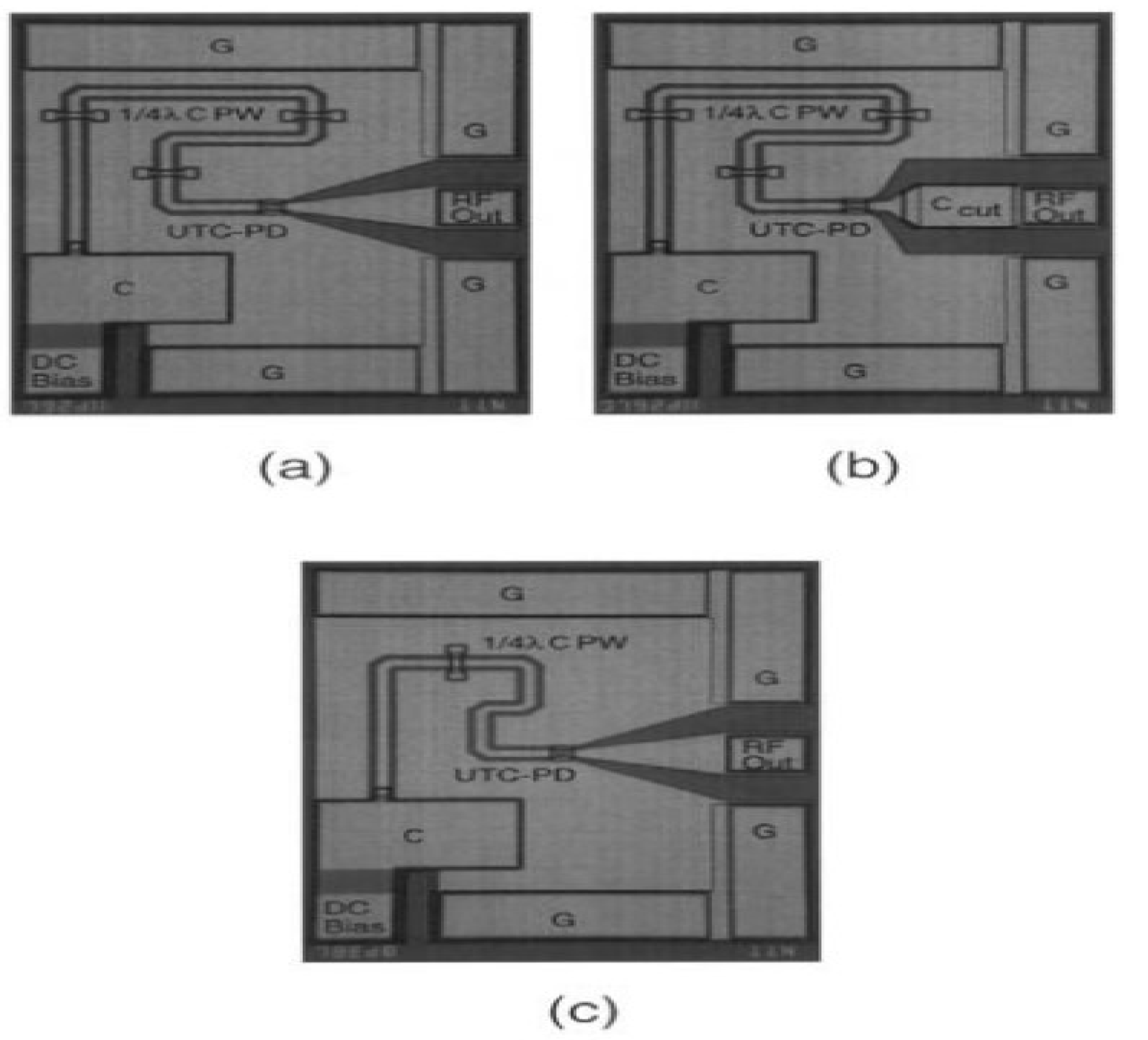

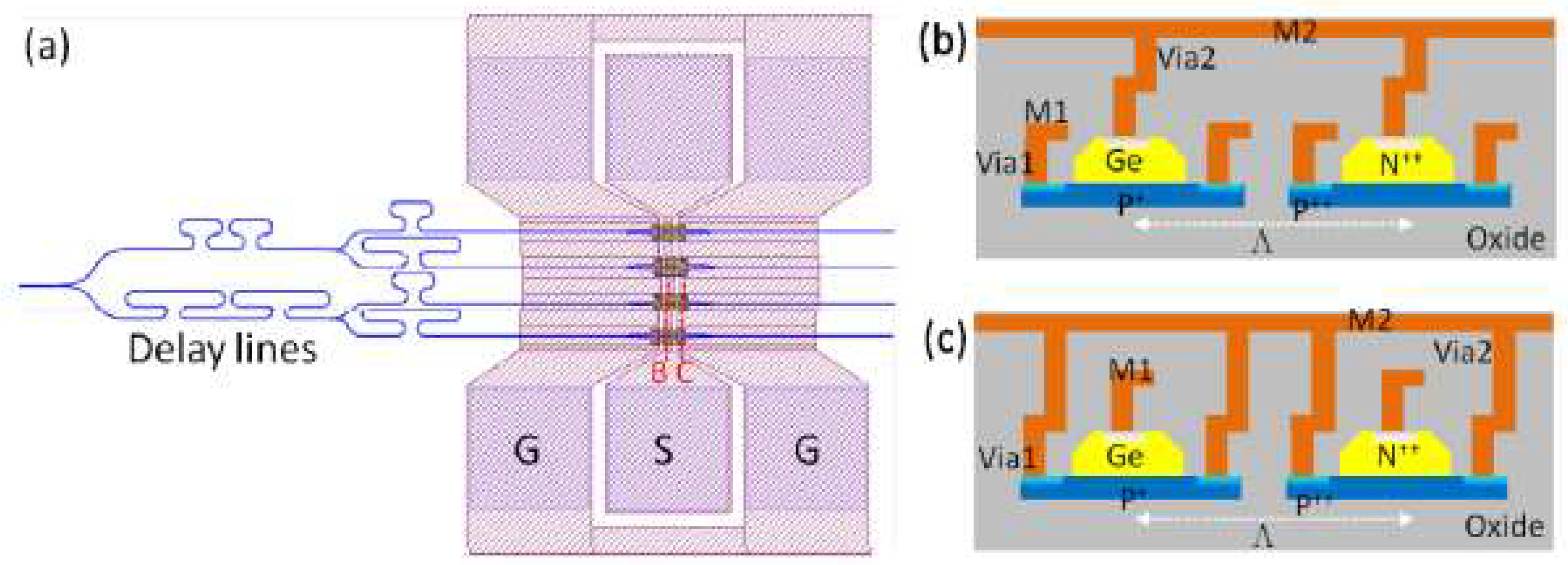

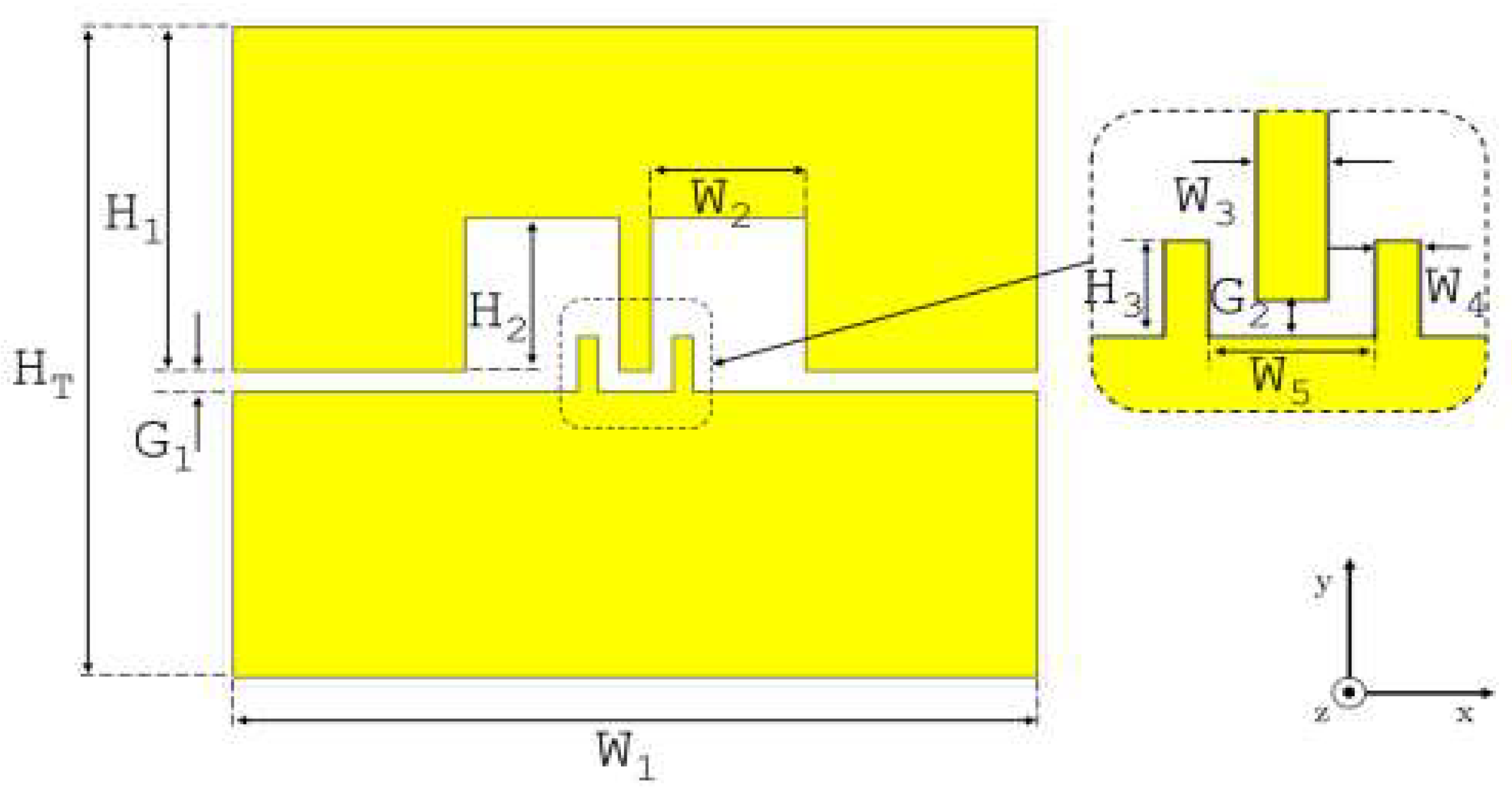

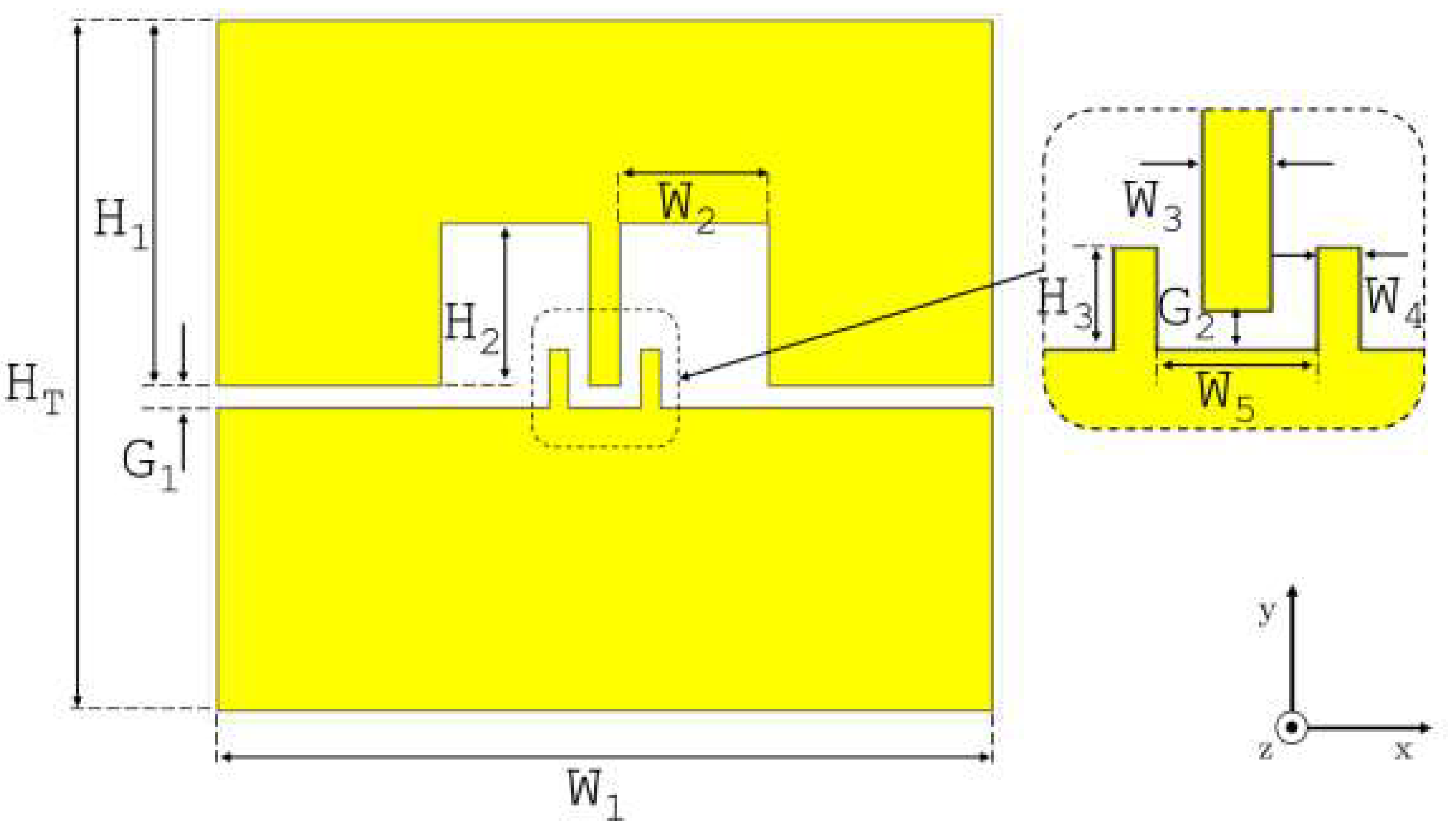

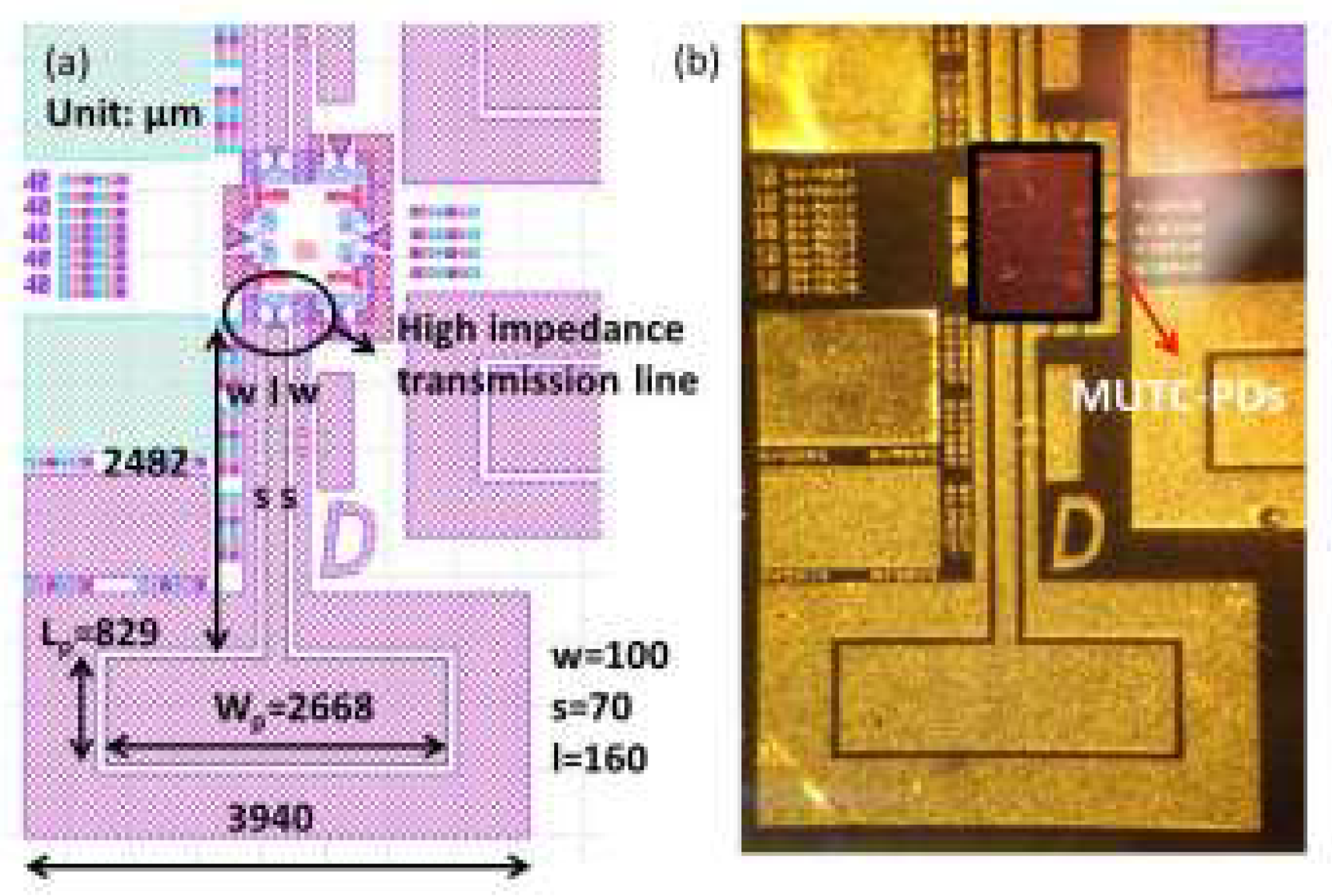

3.1. MMWave Matching Network Design

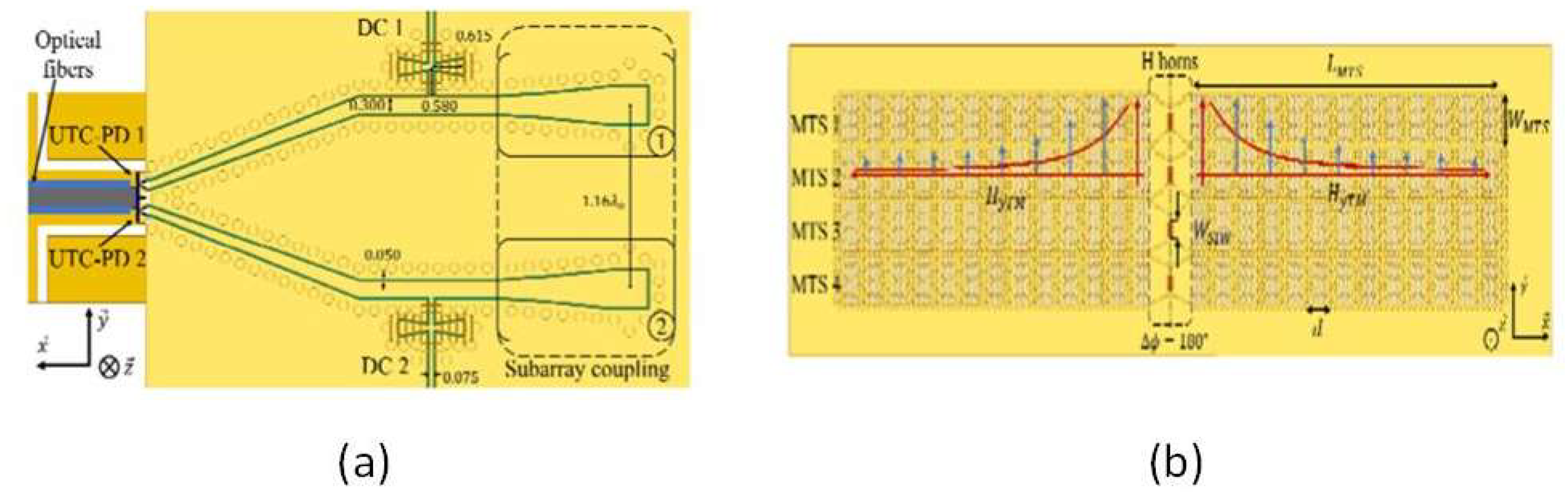

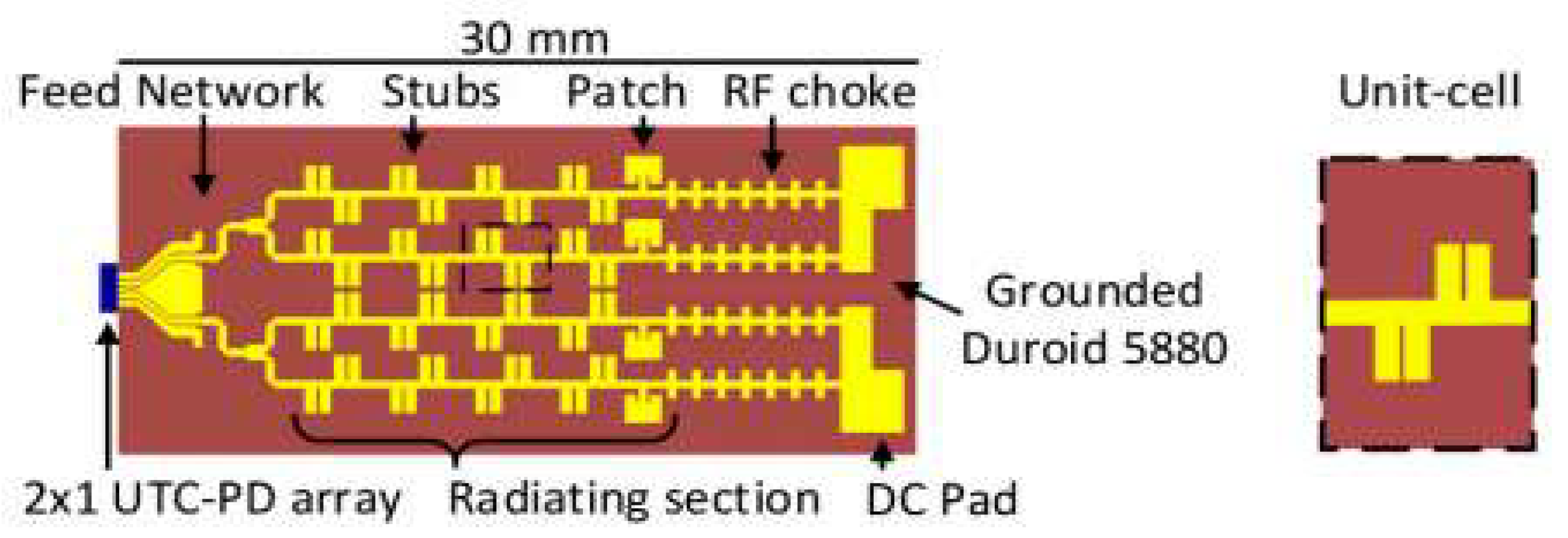

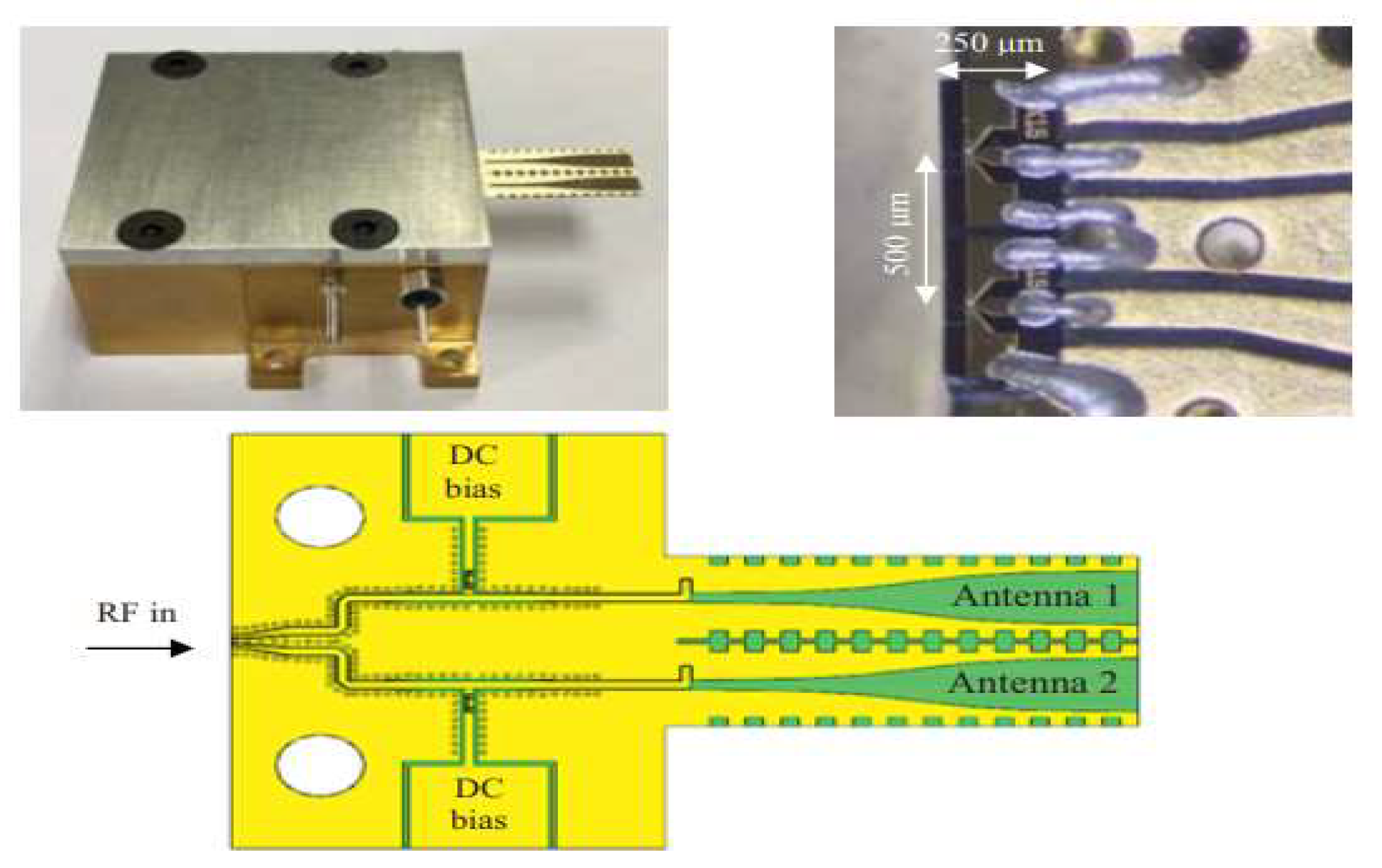

3.2. Photodiode Integrated Photonic Emitters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- “Cisco annual internet Report - Cisco Annual Internet Report (2018–2023) White Paper,” Cisco. https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/solutions/collateral/executive-perspectives/annual-internet-report/white-paper-c11-741490.html (accessed Jul. 18, 2023).

- T. Nagayama, S. Akiba, T. Tomura, and J. Hirokawa, “Photonics-Based MilliMeter-Wave Band Remote Beamforming of Array-Antenna Integrated with Photodiode Using Variable Optical Delay Line and Attenuator,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 36, no. 19, pp. 4416–4422, 2018.

- S. Y. Siew, B. Li, F. Gao, H. Y. Zheng, W. Zhang, P. Guo, S. W. Xie, A. Song, B. Dong, L. W. Luo, C. Li, X. Luo, and G.-Q. Lo, “Review of Silicon Photonics Technology and Platform Development,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 39, no. 13, pp. 4374–4389, 2021.

- Beling, X. Xie, and J. C. Campbell, “High-Power, High-Linearity Photodiodes,” Optica, vol. 3, no. 3, p. 328, 2016. [CrossRef]

- X. Hu et al., “High-Speed and High-Power Germanium Photodetector with a Lateral Silicon Nitride Waveguide,” Photonics Research, vol. 9, no. 5, p. 749, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Byrd et al., “Mode-Evolution-Based Coupler for High Saturation Power Ge-on-Si Photodetectors,” Optics Letters, vol. 42, no. 4, p. 851, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Li et al., “High-Speed and High-Power Ge-on-Si Photodetector with Bilateral Mode-Evolution-Based Coupler,” Photonics, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 142, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Chen, Y. Yu, X. Xiao, and X. Zhang, “High Speed and High Power Polarization Insensitive Germanium Photodetector with Lumped Structure,” Optics Express, vol. 24, no. 9, p. 10030, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhou, G. Chen, S. Fu, Y. Zuo, and Y. Yu, “Germanium Photodetector with Distributed Absorption Regions,” Optics Express, vol. 28, no. 14, p. 19797, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Luo et al., “Silicon-Based Traveling-Wave Photodetector Array (SI-TWPDA) with Parallel Optical Feeding,” Optics Express, vol. 22, no. 17, p. 20020, 2014. [CrossRef]

- C.-M. Chang, J. H. Sinsky, P. Dong, G. de Valicourt, and Y.-K. Chen, “High-Power Dual-Fed Traveling Wave Photodetector Circuits in Silicon Photonics,” Optics Express, vol. 23, no. 17, p. 22857, 2015. [CrossRef]

- T.-C. Tzu et al., “Foundry-Enabled High-Power Photodetectors for Microwave Photonics,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 1–11, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Sun and A. Beling, “High-Speed Photodetectors for Microwave Photonics,” Applied Sciences, vol. 9, no. 4, p. 623, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Sun et al., “Ge-on-Si Waveguide Photodiode Array for High-Power Applications,” 2018 IEEE Photonics Conference (IPC), 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Jiang et al., “High-Power Si-Ge Photodiode Assisted by Doping Regulation,” Optics Express, vol. 29, no. 5, p. 7389, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, M. Piels, N. Nunoya, T. Yin, and J. E. Bowers, “High Power Silicon-Germanium Photodiodes for Microwave Photonic Applications,” IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, vol. 58, no. 11, pp. 3336–3343, 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Michel, J. Liu, and L. C. Kimerling, “High-Performance Ge-on-Si Photodetectors,” Nature Photonics, vol. 4, no. 8, pp. 527–534, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Piels and J. E. Bowers, “40 GHz Si/Ge Uni-Traveling Carrier Waveguide Photodiode,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 32, no. 20, pp. 3502–3508, 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Xie et al., “Heterogeneously Integrated Waveguide-Coupled Photodiodes on SOI with 12 dBm Output Power at 40 GHz,” Optical Fiber Communication Conference Post Deadline Papers, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Srinivasan et al., “27 GHz Silicon-Contacted Waveguide-Coupled Ge/Si Avalanche Photodiode,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 3044–3050, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J.-B. You, H. Kwon, J. Kim, H.-H. Park, and K. Yu, “Photon-Assisted Tunneling for Sub-Bandgap Light Detection in Silicon PN-Doped Waveguides,” Optics Express, vol. 25, no. 4, p. 4284, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Srinivasan et al., “56 Gb/s NRZ O-Band Hybrid BiCMOS-Silicon Photonics Receiver Using Ge/Si Avalanche Photodiode,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 1409–1415, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Zeng et al., “Silicon–Germanium Avalanche Photodiodes with Direct Control of Electric Field in Charge Multiplication Region,” Optica, vol. 6, no. 6, p. 772, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Giboney, M. J. W. Rodwell, and J. E. Bowers, “Traveling-Wave Photodetector Design and Measurements,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 622–629, 1996. [CrossRef]

- J. Cui, T. Li, F. Yang, W. Cui, and H. Chen, “The Dual-Injection Ge-on-Si Photodetectors with High Saturation Power by Optimizing Light Field Distribution,” Optics Communications, vol. 480, p. 126467, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zuo, Y. Yu, D. Zhou, and X. Zhang, “Integrated High Power Germanium Photodetectors Assisted by Optical Field Manipulation,” 2019 24th OptoElectronics and Communications Conference (OECC) and 2019 International Conference on Photonics in Switching and Computing (PSC), 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Senior, Optical Fiber Communications.

- D. Ahn, L. C. Kimerling, and J. Michel, “Efficient Evanescent Wave Coupling Conditions for Waveguide-Integrated Thin-Film Si/Ge Photodetectors on Silicon-on-Insulator/Germanium-on-Insulator Substrates,” Journal of Applied Physics, vol. 110, no. 8, 2011. [CrossRef]

- T.-Y. Liow et al., “Silicon Optical Interconnect Device Technologies for 40 Gb/s and Beyond,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 8200312–8200312, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhou and P. Runge, “Nonlinearities of High-Speed P-I-N Photodiodes and MUTC Photodiodes,” IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, vol. 65, no. 6, pp. 2063–2072, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhou et al., “High-Power V-Band InGaAs/InP Photodiodes,” IEEE Photonics Technology Letters, vol. 25, no. 10, pp. 907–909, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Q. Li et al., “High-Power Flip-Chip Bonded Photodiode with 110 GHz Bandwidth,” 2015 IEEE Photonics Conference (IPC), 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Ali et al., “A Broadband MilliMeter-Wave Photomixing Emitter Array Employing UTC-PD and Planar Antenna,” 2019 44th International Conference on Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz Waves (IRMMW-THz), 2019. [CrossRef]

- J.-M. Wun, C.-H. Lai, N.-W. Chen, J. E. Bowers, and J.-W. Shi, “Flip-Chip Bonding Packaged THz Photodiode with Broadband High-Power Performance,” IEEE Photonics Technology Letters, vol. 26, no. 24, pp. 2462–2464, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu, X. Zhang, and A. Kishk, “Design of High Speed InGaAs/InP One-Sided Junction Photodiodes with Low Junction Capacitance,” Optics Communications, vol. 437, pp. 321–329, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Ito, H. Fushimi, Y. Muramoto, T. Furuta, and T. Ishibashi, “High-Power Photonic Microwave Generation at K- and Ku-Bands Using a Uni-Traveling-Carrier Photodiode,” 2001 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest (Cat. No.01CH37157).

- H. Ito, A. Hirata, T. Minotani, Y. Hirota, T. Ishibashi, A. Sasaki, and T. Nagatsuma, “High-Power Photonic MilliMetre Wave Generation at 100 GHz Using Matching-Circuit-Integrated Uni-Travelling-Carrier Photodiodes,” IEE Proceedings - Optoelectronics, vol. 150, no. 2, pp. 138–142, 2003.

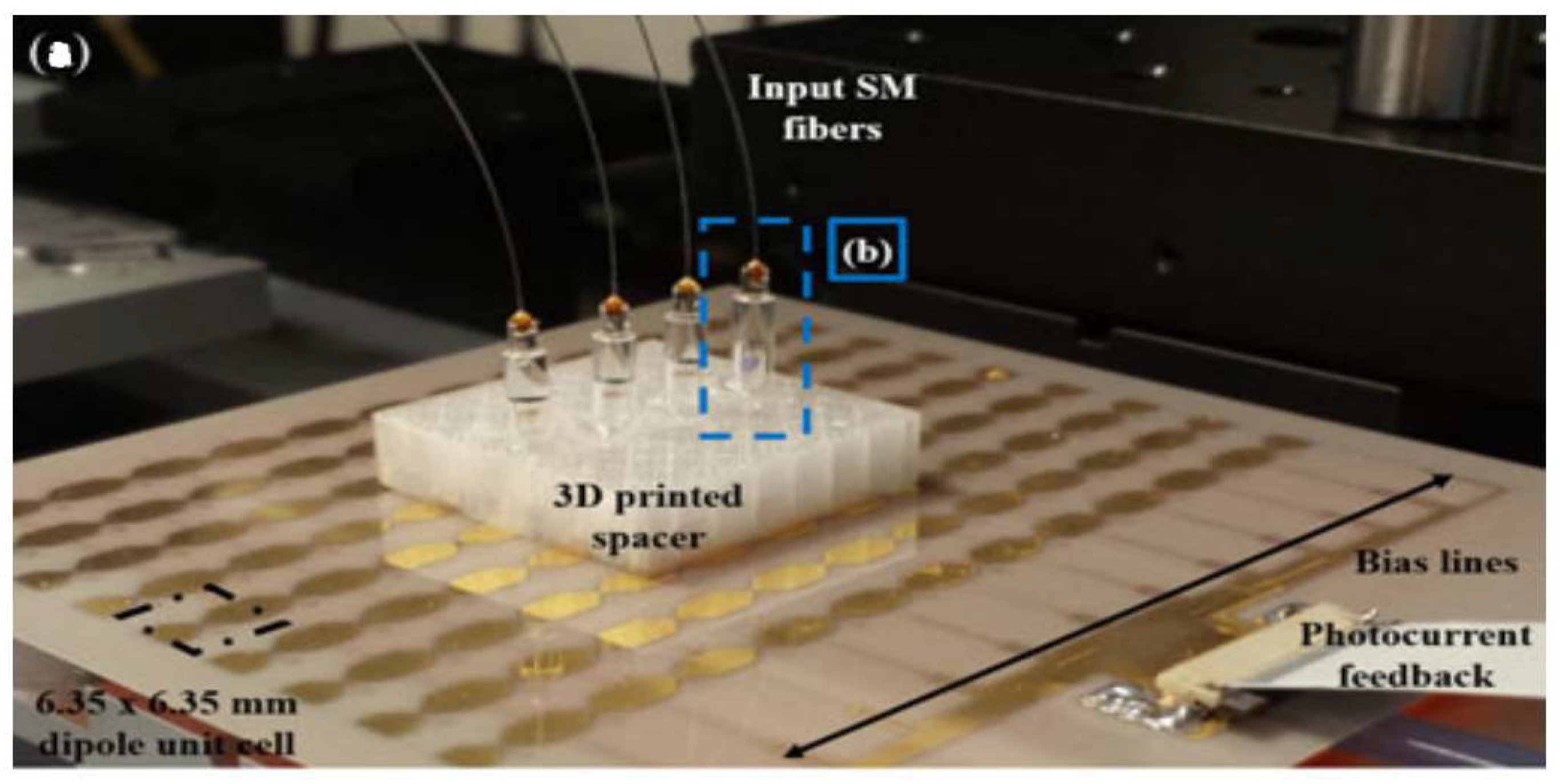

- M. R. Konkol, D. D. Ross, S. Shi, C. E. Harrity, A. A. Wright, C. A. Schuetz, and D. W. Prather, “High-Power Photodiode-Integrated-Connected Array Antenna,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 2010–2016, 2017.

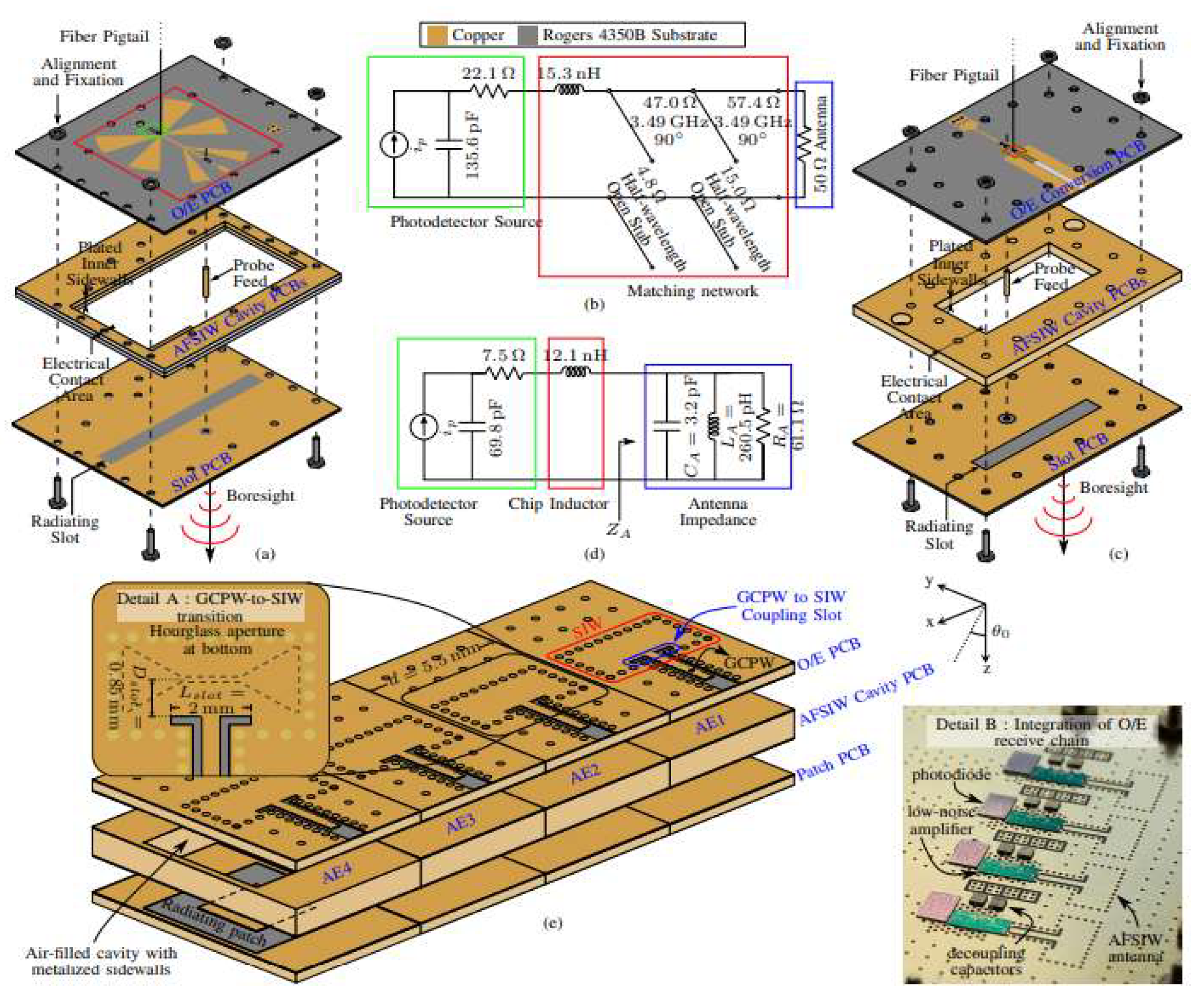

- S. Vega et al., "Compact Optically-Fed Antennas with Reconfigurable Frequency Operation in the Ka Band," 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Singh et al., “60 GHz Resonant Photoreceiver with an Integrated SiGe HBT Amplifier for Analog Radio-over-Fiber Links,” 2020 European Conference on Optical Communications (ECOC), 2020. [CrossRef]

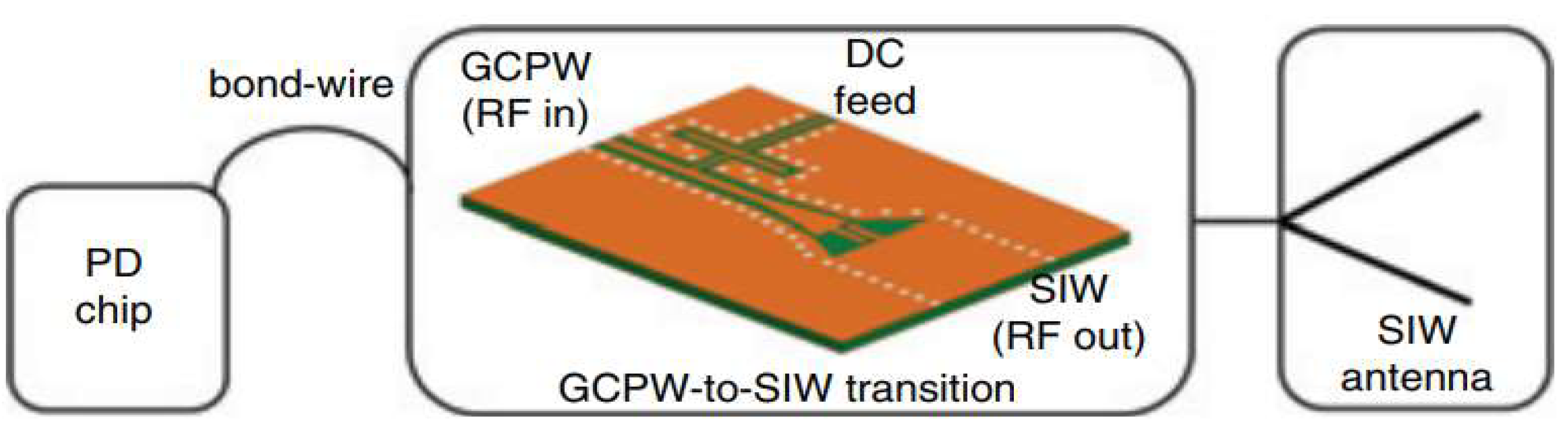

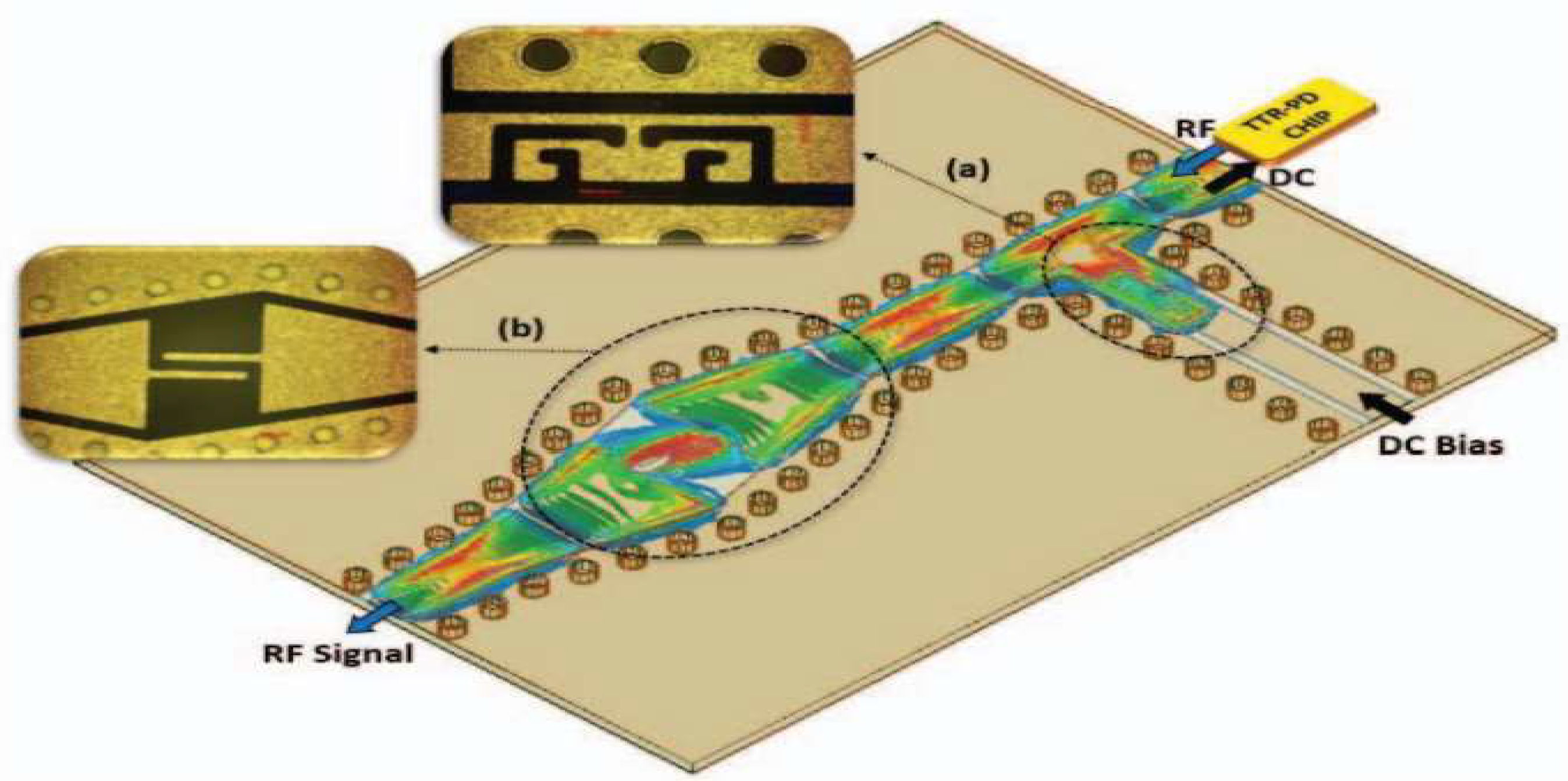

- Flammia, B. Khani, S. Arafat, and A. Stöhr, “60 GHz Grounded-Coplanar-Waveguide-to-Substrate-Integrated-Waveguide Transition for RoF Transmitters,” Electronics Letters, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 34–35, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Khani et al., “Compact E-Band (71–86 GHz) Bias-Tee Module for External Biasing of Millimeter Wave Photodiodes,” 2015 International Topical Meeting on Microwave Photonics (MWP), 2015. [CrossRef]

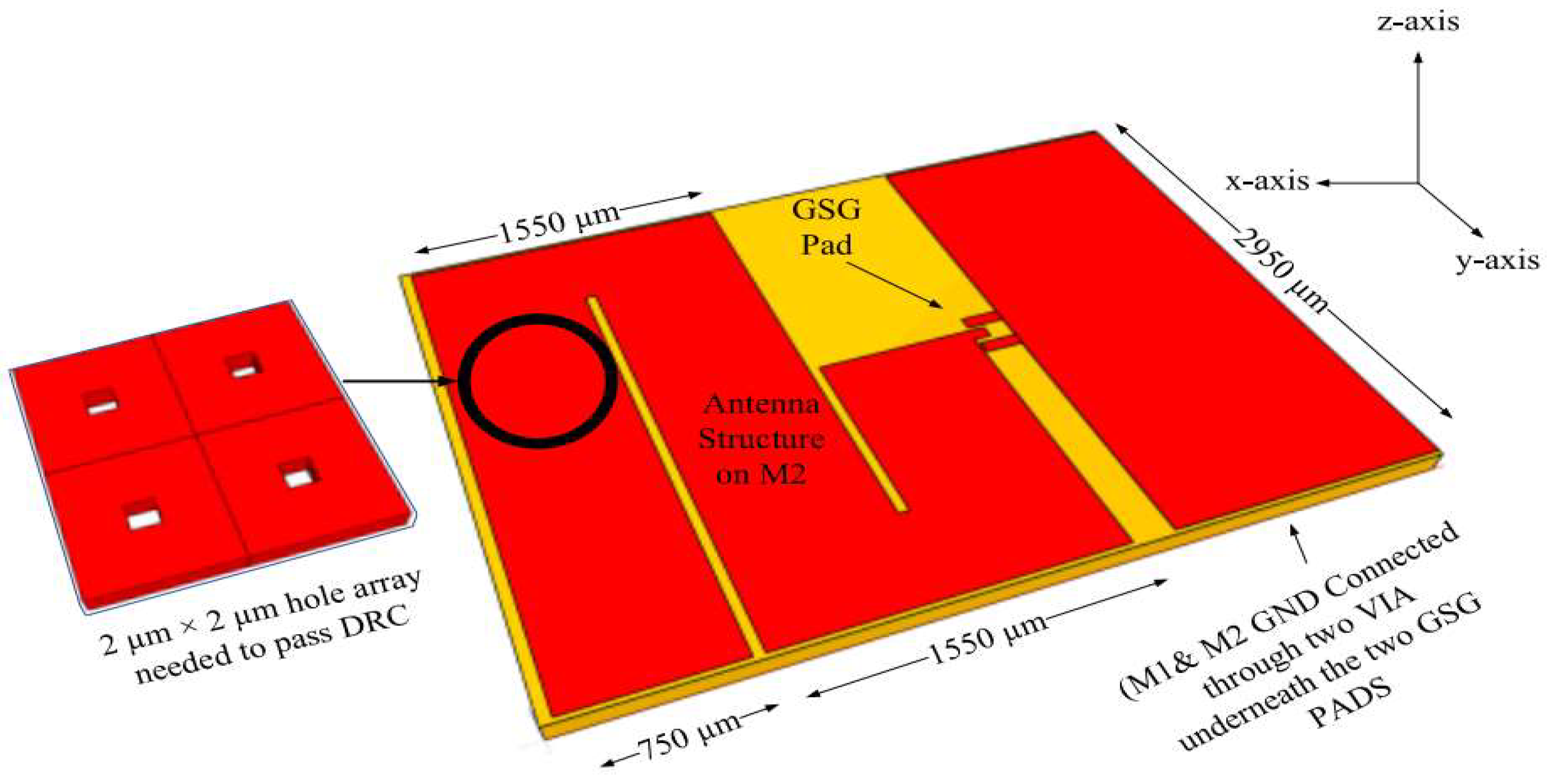

- Radi, A. S. Dhillon, and O. Liboiron-Ladouceur, “Demonstration of Inter-Chip RF Data Transmission Using on-Chip Antennas in Silicon Photonics,” IEEE Photonics Technology Letters, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 659–662, 2020.

- P. Burasa, T. Djerafi, and K. Wu, “A 28 GHz and 60 GHz Dual-Band on-Chip Antenna for 5G-Compatible IoT-Served Sensors in Standard CMOS Process,” IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, vol. 69, no. 5, pp. 2940–2945, 2021.

- Caytan et al., “Co-Design Strategies for AFSIW-Based Remote Antenna Units for RFoF,” 2023 17th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Taillieu, R. Sauleau, M. Alouini, and D. G. Ovejero, “Modulated Metasurface Array for Photonic Beam Steering at W Band,” 2023 17th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Taillieu, R. Sauleau, M. Alouini, and D. Gonzalez-Ovejero, “Cavity-Backed Broadband Microstrip Antenna Array for Photonic Beam Steering at W Band,” 2022 16th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, S. Vega, M. C. Santos, and L. Jofre-Roca, “Short Asymmetrical Inductive Dipole Antenna for Direct Matching to High-Q Chips,” IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 149–153, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Á. J. Pascual-Gracia, M. Ali, G. Carpintero Del Barrio, F. Ferrero, L. Brochier, R. Sauleau, L. E. García-Muñoz, and D. González-Ovejero, “A Photonically-Excited Leaky-Wave Antenna Array at E-Band for 1-D Beam Steering,” Applied Sciences, vol. 10, no. 10, p. 3474, 2020.

- Ali, R. C. Guzman, F. van Dijk, L. E. Garcia-Munoz, and G. Carpintero, “An Antenna-Integrated UTC-PD Based Photonic Emitter Array,” 2019 International Topical Meeting on Microwave Photonics (MWP), 2019.

- C. Renaud, M. Natrella, C. Graham, J. Seddon, F. Van Dijk, and A. J. Seeds, “Antenna Integrated THz Uni-Traveling Carrier Photodiodes,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 1–11, 2018.

- 52. K. Furuya, S. Akiba, J. Hirokawa, and M. Ando, “60 GHz-Band Compact Photonic Antenna Module with Integrated Photodiode,” IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation (ISAP), 2016.

- K. Li et al., “High-Power Photodiode Integrated with Coplanar Patch Antenna for 60-GHz Applications,” IEEE Photonics Technology Letters, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 650–653, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, A., van Dijk, F., Larrue, A., Garcia, M., Gomez, C., and Pommereau, F., "Antenna-Integrated Photodiode Array with Single Optical Input," 2020 International Topical Meeting on Microwave Photonics (MWP). [CrossRef]

| Photodiode | Res. (A/W) | HF Phc. (mA) | BW (GHz) | RF-P (dBm) | Dark Cur. (uA) | Appl. | DC Phc. (mA) |

| Ev. Coupled PD [5] | 0.52 | 12 | 36 | 8.57 | 0.1 | HP | 16 |

| Mode-Evolution PD [7] | 0.47 | 1.88 | 31.6 | -7.53 | 0.073 | HP | 9 |

| 2-Element PD [8] | 0.46 | 13 | 9 | 9.27 | 1.28 | HP | 28.8 |

| 8-Element PD [9] | 0.77 | 1 | 4.1 | -13.01 | 3.46 | HP | 37 |

| TWPD 4-Element [10] | 0.82 | 20 | HP | 65 | |||

| 4-Element TWPDA [11] | 0.76 | 13 | 35 | 9.26 | >3.5 | HP | 112 |

| TWPD [25] | 1.07 | 11.4 | 0.0099 | HP | 13.28 | ||

| 8-Element PD [12] | 0.21 | 48 | 5 | 14.3 | 15 | HP | |

| 4-Element PD [14] | 0.58 | 19 | 15 | 7 | 0.3 | HP | |

| Doping Regulated PD [15] | 1.06 | 5.3 | 20 | 1.5 | 0.0014 | HP | 36.4 |

| PIN PD [16] | 40 | 4.38 | 14.17 | 125 | HP | ||

| Si-Based UTC PD [18] | 0.5 | 2 | 30 | -11.7 | 20 | HP | |

| III-V UTC PD on Si [19] | 0.95 | 40 | 12 | 0.01 | HP | ||

| Av. PD [20] | 0.65 | 27 | low | 100 | LP D-Com. | ||

| Av. PD [21] | 14 | low | LP D-Com. | ||||

| Av. PD [23] | 18.9 | low | LP D-Com. | ||||

| Ev. ≡Evanescent, Av. ≡Avalanche, BW≡ Bandwidth, Res. ≡Responsivity, HF ≡High Frequency, Phc. ≡Photocurrent, RF-P≡ RF Power, Cur. ≡Current, Appl. ≡Applications, HP ≡High Power, LP ≡Low Power, D-Com. ≡Data Communications | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).