Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

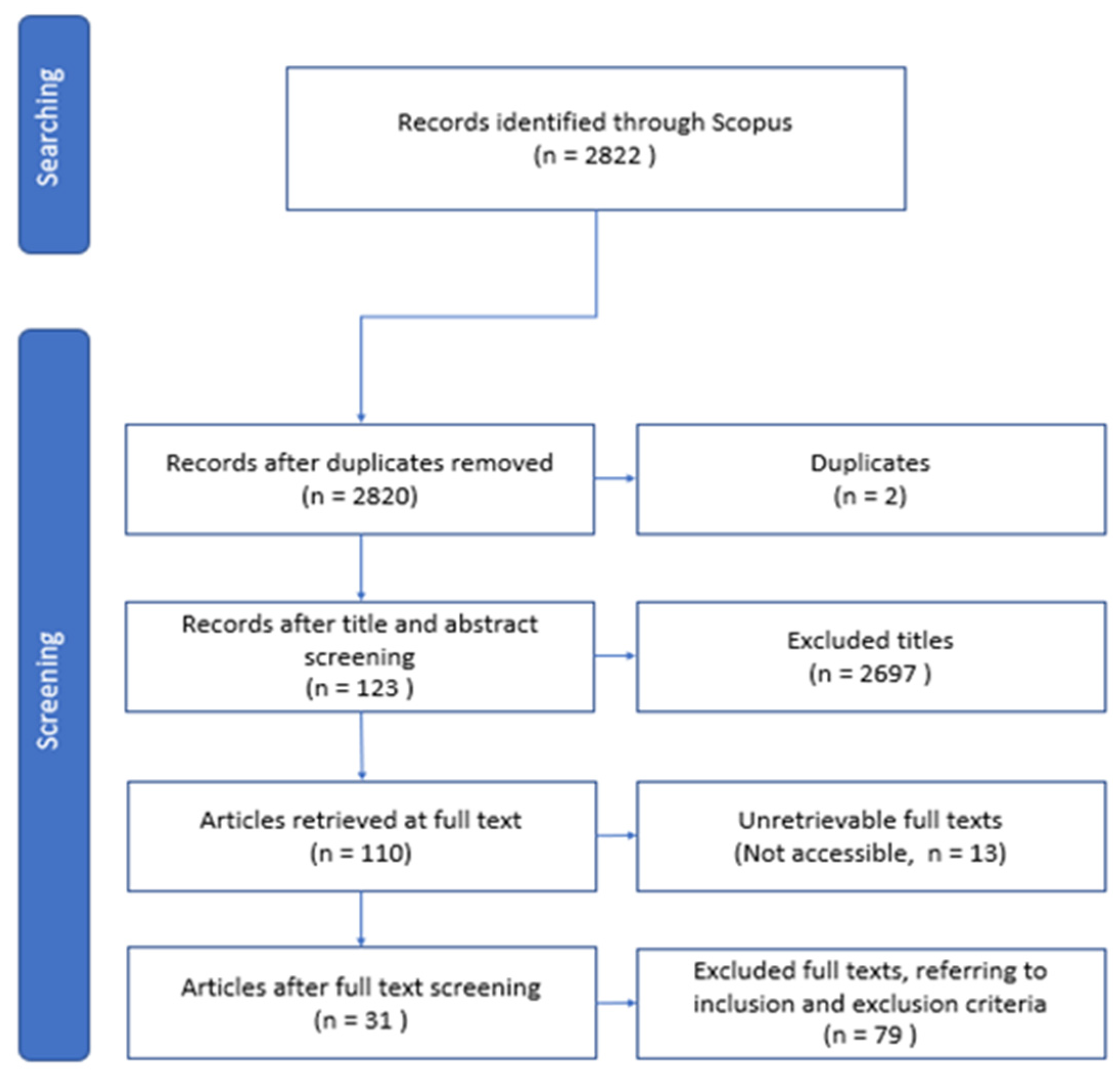

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scoping Review Method

2.2. Evaluation Framework and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Publication Trends

3.2. Community Role and Function

3.3. Social Inclusion and Exclusion

3.4. Power Relations

3.5. Participatory Approach

3.6. Research Innovation and Reflexivity

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. The Ambiguity of ‘Community’

4.2. Indigenous Voices in Research

4.3. A Future of Community Shaping: A Sense of Sharing

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.Y.; Takahashi, K.; Fujimori, S.; Jansakoo, T.; Burton, C.; Huang, H.; Kou-Giesbrecht, S.; Reyer, C.P.O.; Mengel, M.; Burke, E.; et al. Attributing human mortality from fire PM2.5 to climate change. Nature Climate Change 2024, 14, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, W.; Scott, P.; Howard, C.; Scott, C.; Rose, C.; Cunsolo, A.; Orbinski, J. Lived experience of a record wildfire season in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2018, 109, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaverde Canosa, I.; Ford, J.; Paavola, J.; Burnasheva, D. Community Risk and Resilience to Wildfires: Rethinking the Complex Human–Climate–Fire Relationship in High-Latitude Regions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, M.; Cantin, A.S.; de Groot, W.J.; Wotton, M.; Newbery, A.; Gowman, L.M. Global wildland fire season severity in the 21st century. Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 294, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian. ‘Real threat to city’: Yellowknife in Canada evacuates as wildfire nears. 2023.

- Hollander, Z. AK’s Swan Lake Fire Tops 2019 Wildfires at $46M. Alaska Dispatch New 2019.

- Miller, B.A.; Yung, L.; Wyborn, C.; Essen, M.; Gray, B.; Williams, D.R. Re-Envisioning Wildland Fire Governance: Addressing the Transboundary, Uncertain, and Contested Aspects of Wildfire. Fire 2022, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 - 2030; The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Switzerland, 10 Feburary 2015; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, H.; Alam, M.; Berger, R.; Cannon, T.; Huq, S.; Milligan, A. Community-based adaptation to climate change: an overview. In Participatory Learning and Action, 60 ed.; Holly Ashley, N.K., and Angela Milligan, Ed.; 2009; p. 24.

- Rahman, M.F.; Falzon, D.; Robinson, S.-a.; Kuhl, L.; Westoby, R.; Omukuti, J.; Schipper, E.L.F.; McNamara, K.E.; Resurrección, B.P.; Mfitumukiza, D.; et al. Locally led adaptation: Promise, pitfalls, and possibilities. Ambio 2023, 52, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David-Chavez, D.M.; Gavin, M.C. A global assessment of Indigenous community engagement in climate research. Environmental research letters 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titz, A.; Cannon, T.; Krüger, F. Uncovering ‘Community’: Challenging an Elusive Concept in Development and Disaster Related Work. Societies 2018, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, I. Traversing the swampy terrain of postmodern communities: Towards theoretical revisionings of community development. European journal of social work 2001, 4, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Mearns, R.; Scoones, I. Environmental Entitlements: Dynamics and Institutions in Community-Based Natural Resource Management. World Development 1999, 27, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Parker, M.; Martineau, F.; Leach, M. Engaging ‘communities’: anthropological insights from the West African Ebola epidemic. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2017, 372, 20160305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, M.; Steele, W.; Rickards, L.; Fünfgeld, H. Keywords in planning: what do we mean by ‘community resilience’? International planning studies 2016, 21, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Nielsen-Pincus, M.; Abrams, J.; Moseley, C. Advancing characterization of social diversity in the wildland-urban interface: An indicator approach for wildfire management. Landscape and Urban Planning 2017, 160, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räsänen, A.; Lein, H.; Bird, D.; Setten, G. Conceptualizing community in disaster risk management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2020, 45, 101485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panelli, R.; Welch, R. Why Community? Reading Difference and Singularity with Community. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 2005, 37, 1589–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defilippis, J.; Fisher, R.; Shragge, E. Neither Romance Nor Regulation: Re-evaluating Community. International journal of urban and regional research 2006, 30, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.B.; McDonald, G. Community-based Environmental Planning: Operational Dilemmas, Planning Principles and Possible Remedies. Journal of environmental planning and management 2005, 48, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Stephenson, E.; Cunsolo Willox, A.; Edge, V.; Farahbakhsh, K.; Furgal, C.; Harper, S.; Chatwood, S.; Mauro, I.; Pearce, T.; et al. Community-based adaptation research in the Canadian Arctic. 2016.

- Aiken, G.T.; Middlemiss, L.; Sallu, S.; Hauxwell-Baldwin, R. Researching climate change and community in neoliberal contexts: an emerging critical approach. WIREs Climate Change 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. The role for ‘community’ in carbon governance. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Climate change 2011, 2, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, M. On Ambivalence and Hope in the Restless Search for Community: How to Work with the Idea of Community in the Global Age. Sociology 2015, 49, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0. 2024.

- Taylor Aiken, G.; Middlemiss, L.; Sallu, S.; Hauxwell-Baldwin, R. Researching climate change and community in neoliberal contexts: an emerging critical approach. WIREs Climate Change 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharibasam, J.B.; Datta, R. Enhancing community resilience to climate change disasters: Learning experience within and from sub-Saharan black immigrant communities in western Canada. Sustainable Development 2024, 32, 1401–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. Power: a radical view, Second Edition ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tschakert, P.; Parsons, M.; Atkins, E.; Garcia, A.; Godden, N.; Gonda, N.; Henrique, K.P.; Sallu, S.; Steen, K.; Ziervogel, G. Methodological lessons for negotiating power, political capabilities, and resilience in research on climate change responses. World Development 2023, 167, 106247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.S. Urban Regeneration’s Poisoned Chalice: Is There an Impasse in (Community) Participation-based Policy? Urban Studies 2003, 40, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Ford, J.D.; Quinn, C.; Team, I.R.; Harper, S.L. From participatory engagement to co-production: modelling climate-sensitive processes in the Arctic. Arctic Science 2021, 7, 699–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborah, S. Carr, K.H. An Evaluation of Three Democratic, Community-Based Approaches to Citizen Participation: Surveys, Conversations With Community Groups, and Community Dinners. Society & Natural Resources 2001, 14, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisner, J. A CIVIC REPUBLICAN PERSPECTIVE ON THE NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY ACT’S PROCESS FOR CITIZEN PARTICIPATION. Environmental Law 1996, 26, 53–94. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.S.; Escobedo, F.J.; Sloggy, M.R.; Sánchez, J.J. A burning issue: Reviewing the socio-demographic and environmental justice aspects of the wildfire literature. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0271019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, H.W.; McGee, T.K.; Christianson, A.C. Indigenous Elders’ Experiences, Vulnerabilities and Coping during Hazard Evacuation: The Case of the 2011 Sandy Lake First Nation Wildfire Evacuation. Society & Natural Resources 2020, 33, 1273–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianson, A.C.; McGee, T.K.; Whitefish Lake First, N. Wildfire evacuation experiences of band members of Whitefish Lake First Nation 459, Alberta, Canada. Natural Hazards 2019, 98, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirina, A.A. Evenki fire and forest ontology in the context of the wildfires in Siberia. Polar Science 2021, 29, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélisle, A.C.; Gauthier, S.; Asselin, H. Integrating Indigenous and scientific perspectives on environmental changes: Insights from boreal landscapes. People and Nature 2022, 4, 1513–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokurova, L.; Solovyeva, V.; Filippova, V. When Ice Turns to Water: Forest Fires and Indigenous Settlements in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Sustainability 2022, 14, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbis, Z.; Cox, A.; Orttung, R.W. Taming the wildfire infosphere in Interior Alaska: Tailoring risk and crisis communications to specific audiences. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2023, 91, 103682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Christianson, A.; Spinks, M. Return to Flame: Reasons for Burning in Lytton First Nation, British Columbia. Journal of Forestry 2018, 116, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, H.W.; McGee, T.; Christianson, A.C. The role of social support and place attachment during hazard evacuation: the case of Sandy Lake First Nation, Canada. Environmental Hazards 2019, 18, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, H.W.; First Nation, S.L.; McGee, T.K.; Christianson, A.C. A qualitative study exploring barriers and facilitators of effective service delivery for Indigenous wildfire hazard evacuees during their stay in host communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2019, 41, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergibi, M.; Hesseln, H. Awareness and adoption of FireSmart Canada: Barriers and incentives. Forest Policy and Economics 2020, 119, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, T.K. Preparedness and Experiences of Evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River Wildfire. Fire 2019, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklina, V.; Sizov, O.; Bogdanov, V.; Krasnoshtanova, N.; Morozova, A.; Petrov, A.N. Combining community observations and remote sensing to examine the effects of roads on wildfires in the East Siberian boreal forest. Arctic Science 2023, 9, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.A.; Sanseverino, M.; Higgs, E. Weather Awareness: On the Lookout for Wildfire in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Mountain Research and Development 2017, 37, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.M.; Reed, M.G.; Fletcher, A.J. Wildfire in the news media: An intersectional critical frame analysis. Geoforum 2020, 114, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labossière, L.M.M.; McGee, T.K. Innovative wildfire mitigation by municipal governments: Two case studies in Western Canada. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2017, 22, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhnoo, S.; Persson, S. The flip side of the coin: Perils of public–private disaster cooperation. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 2022, 30, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.I.; Ziel, R.H.; Calef, M.P.; Varvak, A. Spatial distribution of wildfire threat in the far north: exposure assessment in boreal communities. Natural Hazards 2024, 120, 4901–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutein, K.F.; McGowan, J.; Goodchild, A. Evacuating isolated islands with marine resources: A Bowen Island case study. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2022, 72, 102865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brémault-Phillips, S.; Pike, A.; Olson, J.; Severson, E.; Olson, D. Expressive writing for wildfire-affected pregnant women: Themes of challenge and resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2020, 50, 101730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subroto, S.; Datta, R. Perspectives of racialized immigrant communities on adaptability to climate disasters following the UN Roadmap for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030. Sustainable development (Bradford, West Yorkshire, England) 2024, 32, 1386–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, T.M.; Reed, M.G.; Fletcher, A.J. Learning from wildfire: co-creating knowledge using an intersectional feminist standpoint methodology. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.M.; Reed, M.G.; Fletcher, A.J. Applying intersectionality to climate hazards: a theoretically informed study of wildfire in northern Saskatchewan. Climate Policy 2021, 21, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.; Muhammad, M.; Sanchez-Youngman, S.; Rodriguez Espinosa, P.; Avila, M.; Baker, E.A.; Barnett, S.; Belone, L.; Golub, M.; Lucero, J.; et al. Power Dynamics in Community-Based Participatory Research: A Multiple–Case Study Analysis of Partnering Contexts, Histories, and Practices. Health Education & Behavior 2019, 46, 19S–32S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.; Kenny, A.; Dickson-Swift, V. Ethical Challenges in Community-Based Participatory Research: A Scoping Review. Qualitative Health Research 2018, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, S.E. Critiquing Community Engagement. Management Communication Quarterly 2010, 24, 359–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setten, G.; Lein, H. “We draw on what we know anyway”: The meaning and role of local knowledge in natural hazard management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2019, 38, 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copes-Gerbitz, K.; Dickson-Hoyle, S.; Ravensbergen, S.L.; Hagerman, S.M.; Daniels, L.D.; Coutu, J. Community Engagement With Proactive Wildfire Management in British Columbia, Canada: Perceptions, Preferences, and Barriers to Action. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulig, J.; Botey, A.P. Facing a wildfire: What did we learn about individual and community resilience? Natural Hazards 2016, 82, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, E.; Krueger, R.; Wright, J.; Woods, K.; Cottar, S. Disaster Awareness and Preparedness Among Older Adults in Canada Regarding Floods, Wildfires, and Earthquakes. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 2024, 15, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlam, C.; Almendariz, D.; Goode, R.W.; Martinez, D.J.; Middleton, B.R. Keepers of the Flame: Supporting the Revitalization of Indigenous Cultural Burning. Society & Natural Resources 2022, 35, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, P.; Tyler, M.; Hart, A.; Mees, B.; Phillips, R.; Stratford, J.; Toh, K. Creating “Community”? Preparing for Bushfire in Rural Victoria. Rural Sociology 2013, 78, 186–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.; Çinar, C.; Carmo, M.; Malagoli, M.A.S. Social and historical dimensions of wildfire research and the consideration given to practical knowledge: a systematic review. Natural Hazards 2022, 114, 1103–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andress, L.; Hall, T.; Davis, S.; Levine, J.; Cripps, K.; Guinn, D. Addressing power dynamics in community-engaged research partnerships. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes 2020, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Moseley, C.; Carroll, M.S.; Williams, D.R.; Davis, E.J.; Fischer, A.P. Categorizing the Social Context of the Wildland Urban Interface: Adaptive Capacity for Wildfire and Community “Archetypes”. Forest Science 2014, 61, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J. Indigenous Health and Climate Change. American Journal of Public Health 2012, 102, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haalboom, B.; Natcher, D. The power and peril of “vulnerability”: Lending a cautious eye to community labels. Reclaiming Indigenous Planning 2013, 357–375. [Google Scholar]

- Christianson, A.C.; Sutherland, C.R.; Moola, F.; Gonzalez Bautista, N.; Young, D.; MacDonald, H. Centering Indigenous Voices: The Role of Fire in the Boreal Forest of North America. Current Forestry Reports 2022, 8, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copes-Gerbitz, K.; Pascal, D.; Comeau, V.M.; Daniels, L.D. Cooperative community wildfire response: Pathways to First Nations’ leadership and partnership in British Columbia, Canada. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2024, 114, 104933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Publication years | Published between 2015-2024 | Published before 2015 |

| Language | Published in English | Published in non-English |

| Document type | Journal articles in Scopus | Other including but not limited to books, book chapters, conference proceedings, and editorials in Scopus |

| Field | Wildfire research in disaster risk re-duction and climate change adaptation in the fields of social science, geography and environment science | Other including but not limited to books, book chapters, conference proceedings, and editorials in Scopus |

| Study Area | High-latitude areas (above 50°N) | Other areas (below 50°N) |

| Focus | A focus on community level of wildfire risk reduction | Other scales such as individual scale, national scale, landscape scale of wildfires, etc; Or focus on conceptual or theoretical under-standing of community-based wildfire risk reduction |

| Dimension | Content (attributes) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Research background | General information, on the study including: (a)Study location (b)Published journal (c)Research themes |

|

| Community role and function | Dimension emphasizes how ‘community’ has been under-stood in the research, including: (a)The Interpretation level of ‘community’ (b)The community conception types (c)The correlation between community conception and research themes |

Lane and McDonald [22]; Aiken et al. [28]; Walker [25]; Mulligan et al. [17]; Titz et al. [13]; Räsänen et al. [19] |

| Social inclusion and exclusion | Dimension emphasizes which attributes of ‘community’ have been studied, including: (a)the main attribute(s) of ‘community’ research studied (b)other attribute(s) of ‘community’ research considered |

Lane and McDonald [22]; Titz et al. [13]; Mulligan et al. [17]; Acharibasam and Datta [29] |

| Power relations | Dimension refers to who represented and participated in the research as ‘community’, including: (a)the perspective of perceiving the ‘community’ (b)the represented group(s) of ‘community’ in the research (c)the other stakeholders involved in the community-based research in perceiving ‘community |

Lukes [30]; Rahman et al. [11]; Lane and McDonald [22]; Titz et al. [13]; Tschakert et al. [31] |

| Participatory approach | Dimension refers to community participation in the re-search at various stages, such as research design, implementation, and outputs, including: (a)the research practices of community participation (b)the level(s) of community participation |

Jones [32]; Davis et al. [33]; David-Chavez and Gavin [12]; Reed [34]; Reid et al. [10] |

| Research reflexivity | The critical reflection on community-based research itself, including: (a)the critical reviews on the research design, implementation, and outputs (b)the research connection and suggestions for future research tendency. |

Carr and Halvorsen [35]; Poisner [36]; Aiken et al. [28] |

| (1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Partial | Informed | Consistent | |

| Lack of interpretation to reflect on the criterion in the research practice | Limited interpretation to reflect on the criterion in the research process | Clear and consistent interpretation to reflect on the criterion in all lines of research practice | |

| (2) | |||

| Partial | Informed | Consistent | Adaptive |

| Perform a task requested by the researcher | Being consulted in the decision-making process over the research process | Work collaboratively with the community over the research process | Have primary authority over the research process (e.g., represent the community) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).