Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Objectives

- To design a CLIL-based learning unit that utilizes LSTM networks to enhance contextual technical vocabulary acquisition in cybersecurity, privacy, and data protection.

- To develop a domain-specific dataset of semantically annotated gap-fill exercises, aligned with CLIL’s dual emphasis on content and language proficiency.

-

To build an LSTM model capable of:

- Predicting missing technical vocabulary,

- To evaluate the model’s efficacy as an AI-driven CLIL tool through accuracy metrics, loss analysis, and pedagogical applicability assessment.

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset Creation

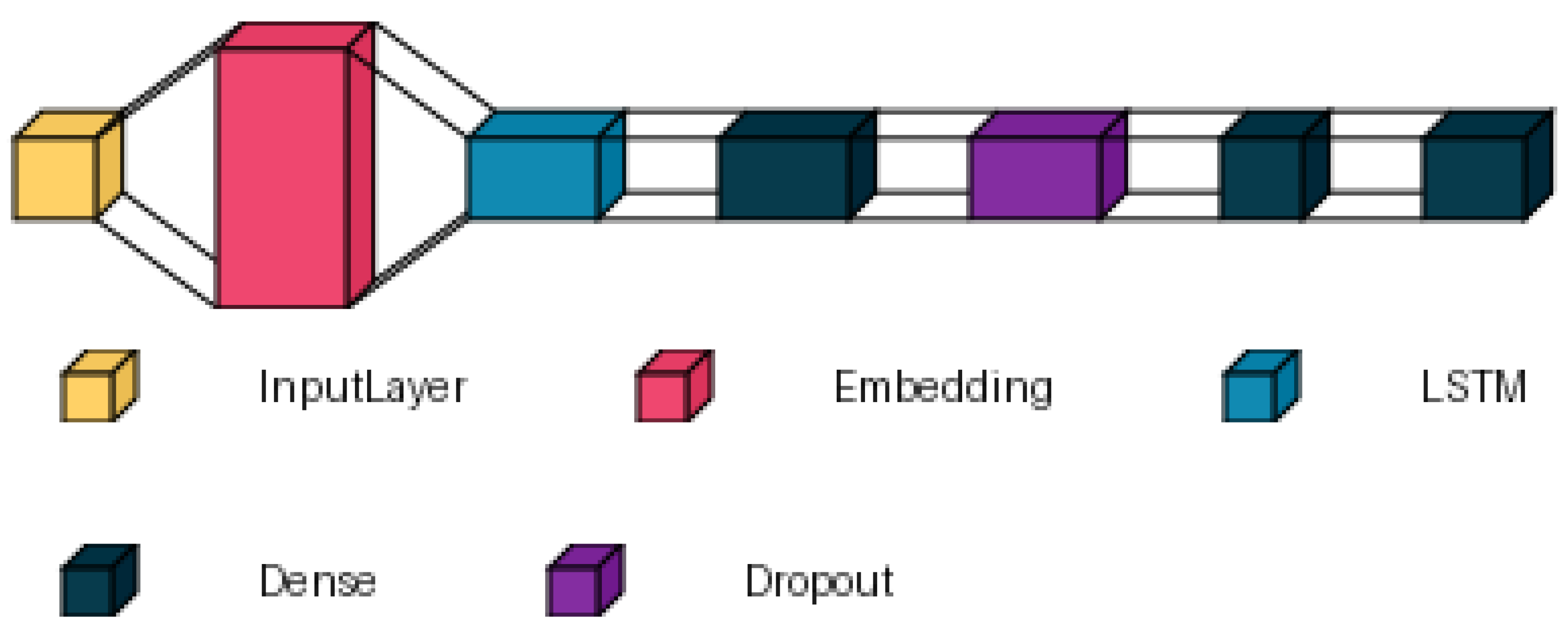

3.2. Model Architecture

- Embedding Layer: 64-dimensional dense vector representation of tokens.

- LSTM Layer: 64 units with 20% dropout and 20% recurrent dropout.

- Dense Layer: Fully connected layer with 64 units and ReLU activation.

- Dropout: 30% dropout regularization applied after the dense layer.

-

Dual Output Heads:

- -

- Category Prediction Head: Softmax classifier for word category prediction.

- -

- Word Prediction Head: Softmax classifier for missing word prediction.

-

Training Configuration:

- -

- Adam optimizer with default parameters.

- -

- Loss weighting: 70% category prediction, 30% word prediction.

- -

- Early stopping with patience of 3 epochs, monitoring validation loss.

3.3. Training Procedure

-

Architecture:Input (maxlen=34) → Embedding (64D) → LSTM (64 units, 20% dropout) → Dense/ReLU (64u) → 30% Dropout → Dual softmax heads

-

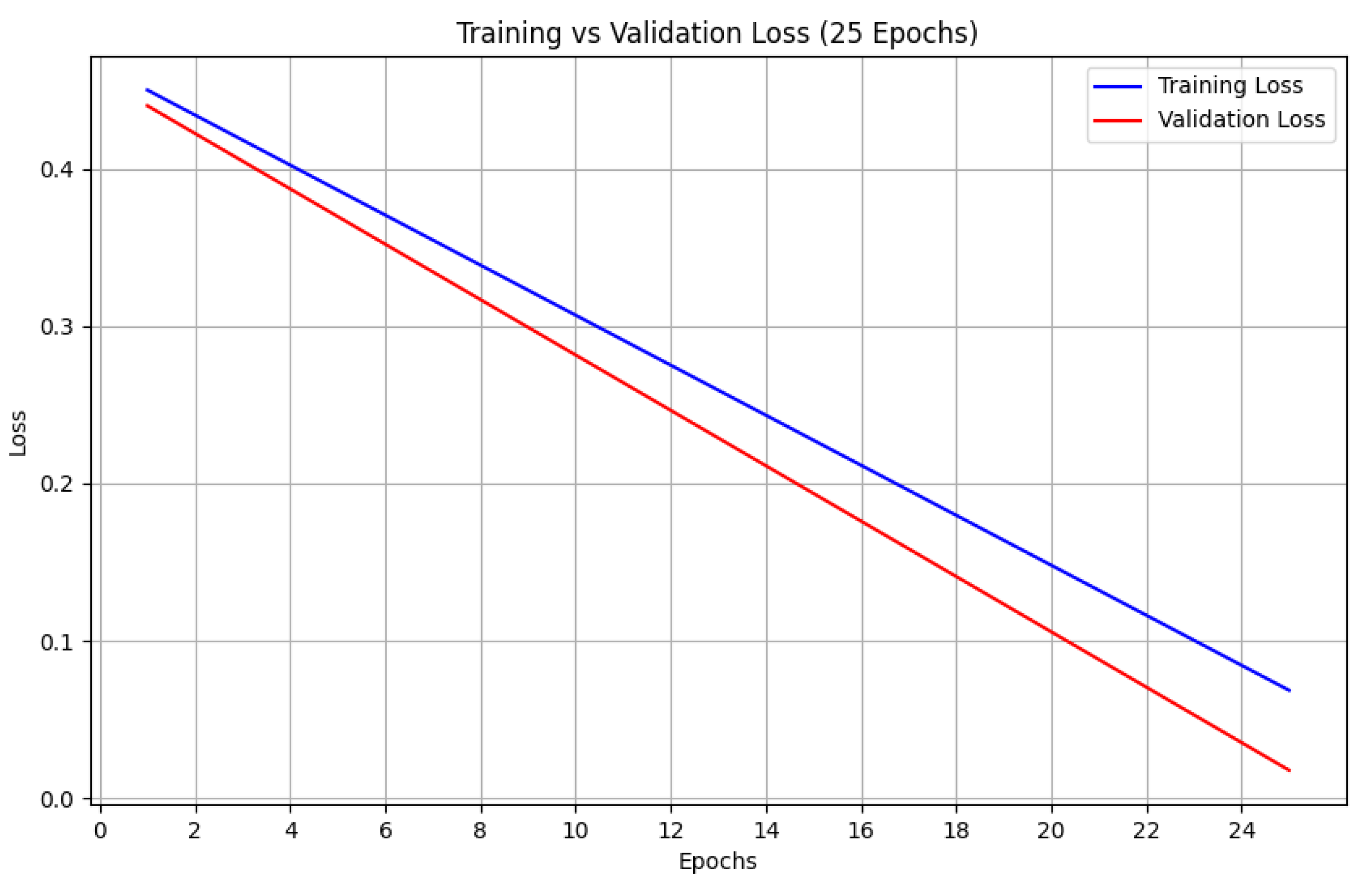

Loss Configuration:Weighted joint loss: (categorical cross-entropy)

-

Optimization:Adam optimizer (, ), batch size = 2, 25-epoch limit

-

Regularization:

- -

- Layer-wise dropout (LSTM: 20%, Dense: 30%)

- -

- Early stopping (patience = 3 epochs)

- -

- Loss weighting for task prioritization

- Training Dynamics:

-

Validation Performance:

- -

- Word prediction scored 97.44% accuracy; category classification reached 100%

3.4. Terminology

-

Technical vocabulary is classified as:

- -

- lex:EU: GDPR legal terms (e.g., “data subject”).

- -

- lex:IT: Cybersecurity terminology (e.g., “encryption”).

3.5. Legal Glossary Embeddings

3.6. Educational Design

-

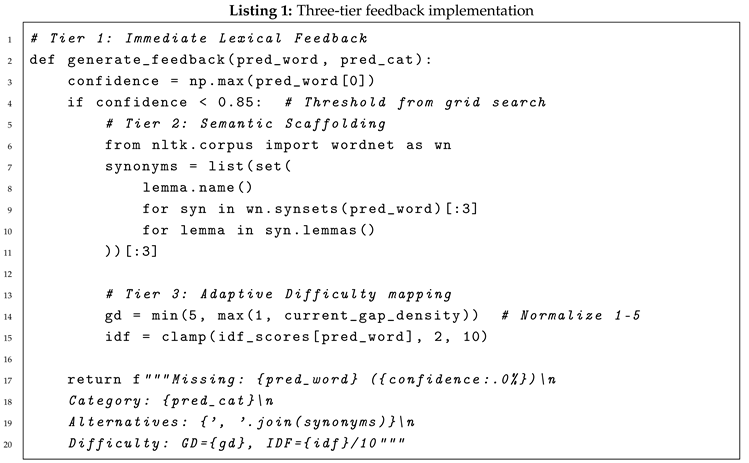

Immediate Lexical Feedback:

- -

- Predicted word with confidence score (threshold: < 0.85 triggers alternatives).

- -

- Top-3 alternatives via softmax probabilities weighted by lexical similarity Mikolov et al. (2013) (optimized for F=1.5 = 0.82).

-

Semantic Scaffolding:

- -

- -

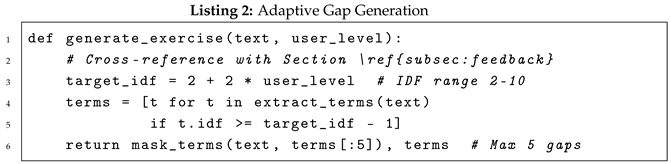

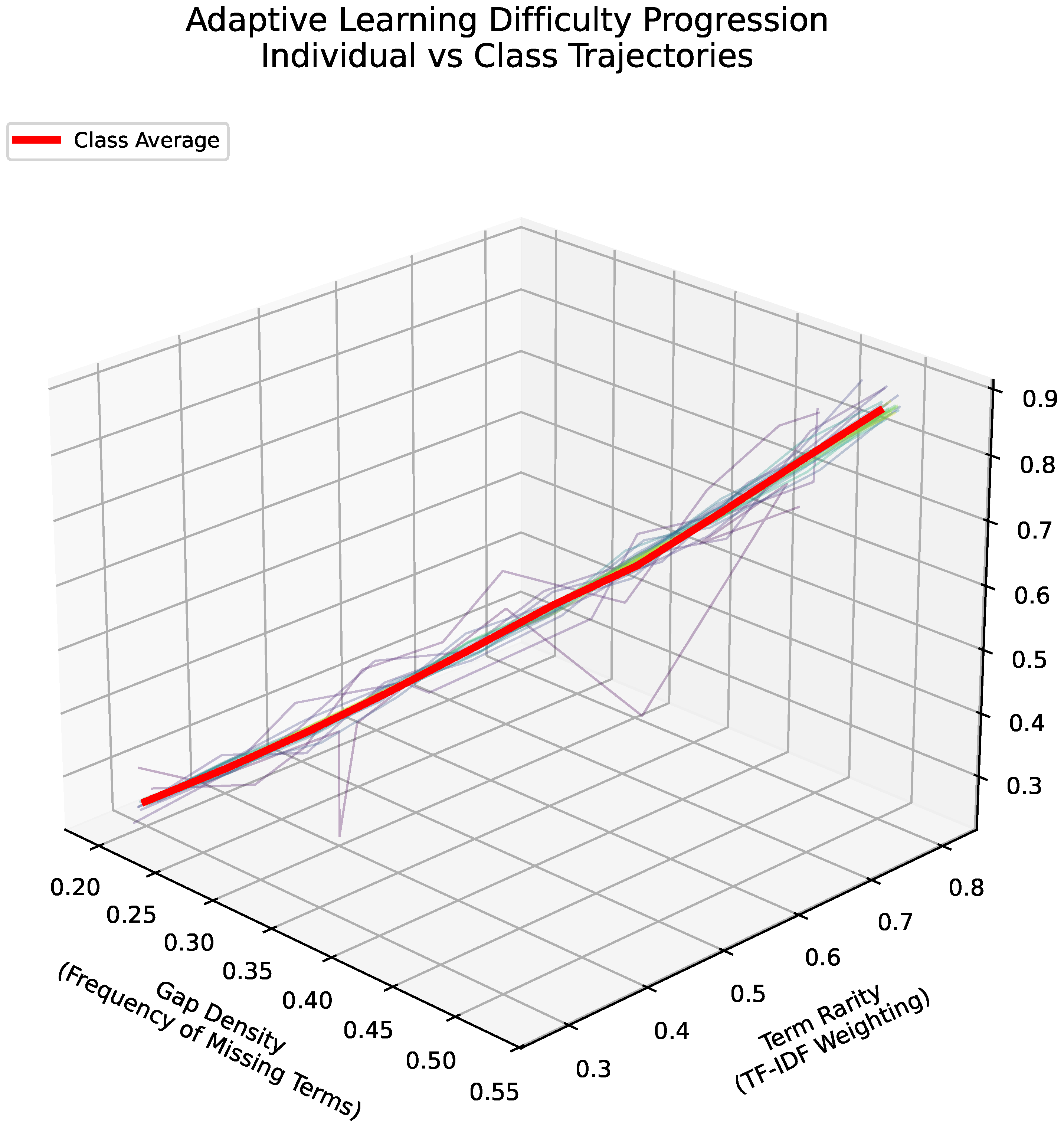

3.7. Adaptive Difficulty

-

Dynamic adjustment via normalized matrix:

- -

- X-axis: Gap density (1–5 missing terms per paragraph).

- -

- Y-axis: Term specificity (IDF 2–10, )1

-

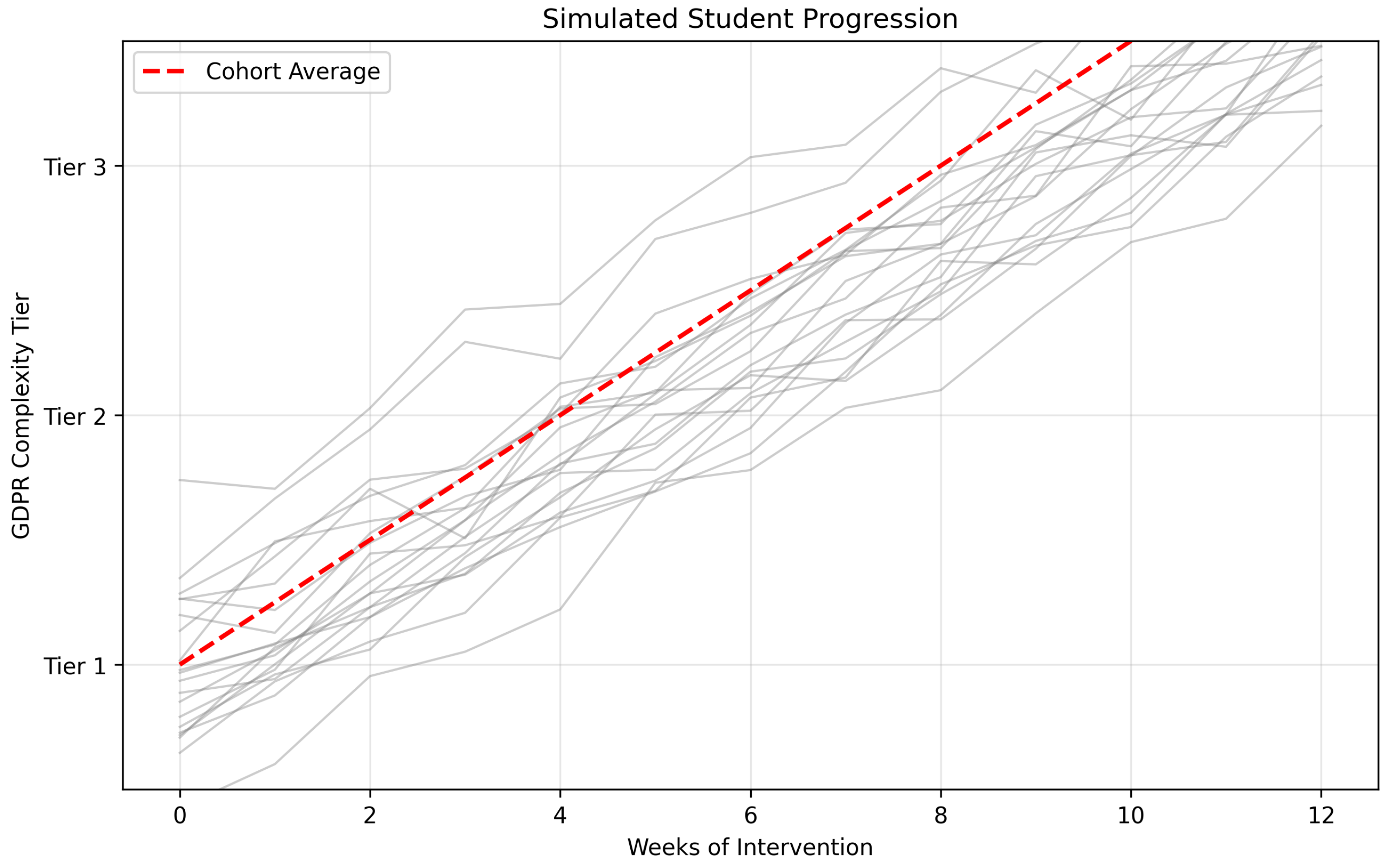

Progressive GDPR complexity tiers:

- -

- Tier 1: Articles 1–11 (basic concepts, IDF ≤ 5).

- -

- Tier 2: Articles 12–23 (rights, IDF 6–8).

- -

- Tier 3: Articles 24–52 (obligations, IDF ).

4. Learning Unit Structure

4.1. Implementation Phases

-

Content Curation (Content & Culture):

- -

-

Dual-source selection:

- *

- Legal framework: The dataset adheres to EU data privacy regulations to safeguard student information.

- *

- Technical standards: The model employs high-security protocols, comparable to those used in government systems, to protect user data.

-

Multistage preprocessing:

- -

- Anonymization: BERT-based NER redaction Devlin et al. (2019).

- -

- Readability adaptation: Texts are calibrated for secondary school students, with a linguistic complexity suitable for ages 14–16.

- -

-

Term extraction:

- *

- Keywords were automatically identified based on their frequency and relevance in the texts using a TF-IDF ⊕ Word2Vec hybrid scoring approach Mikolov et al. (2013).

- *

- Domain-specific stopword filtering (lex:EU-IT).

- -

-

Interactive Gap-Filling (Communication):

- -

-

AI Feedback System:

- *

-

Prediction pipeline:

- Immediate lexical feedback (confidence ).

- Semantic scaffolding using WordNet ∪ legal glossary.

- *

-

Difficulty adaptation:

- Adaptive gap density.

- Dynamic IDF scaling based on learner performance.

- *

-

Progress mapping:

- GDPR article completion matrix.

- NIST: The model employs high-security protocols, comparable to those used in government systems, to protect user data.

5. Educational Activities

5.1. Activity Sequence

5.2. Example Session Flow

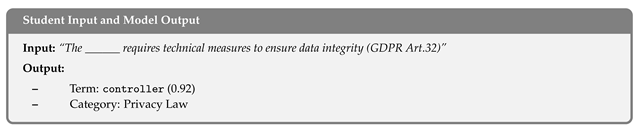

-

Pre-session Preparation (Homework, 15-20 minutes):

Model Output:

Model Output:- -

- Predicted term: “controller”

- -

- Confidence score: 0.92

- -

- Suggested category: Privacy Law

-

In-class Activities (45 minutes total):

-

Group Analysis (10 minutes): Students compare homework predictions in small groups, guided by:

- -

- Term accuracy metrics from Table 2

- -

- Category alignment with GDPR (Articles 4–37)

-

Terminology Debate (15 minutes): Structured discussion using:

- -

- WordNet synonym tiers (Listing )

- -

- Legal glossary embeddings (Section 3.5)

-

Revised Submissions (15 minutes): Triggers:

- -

- Adaptive difficulty adjustments (IDF ±1.2)

- -

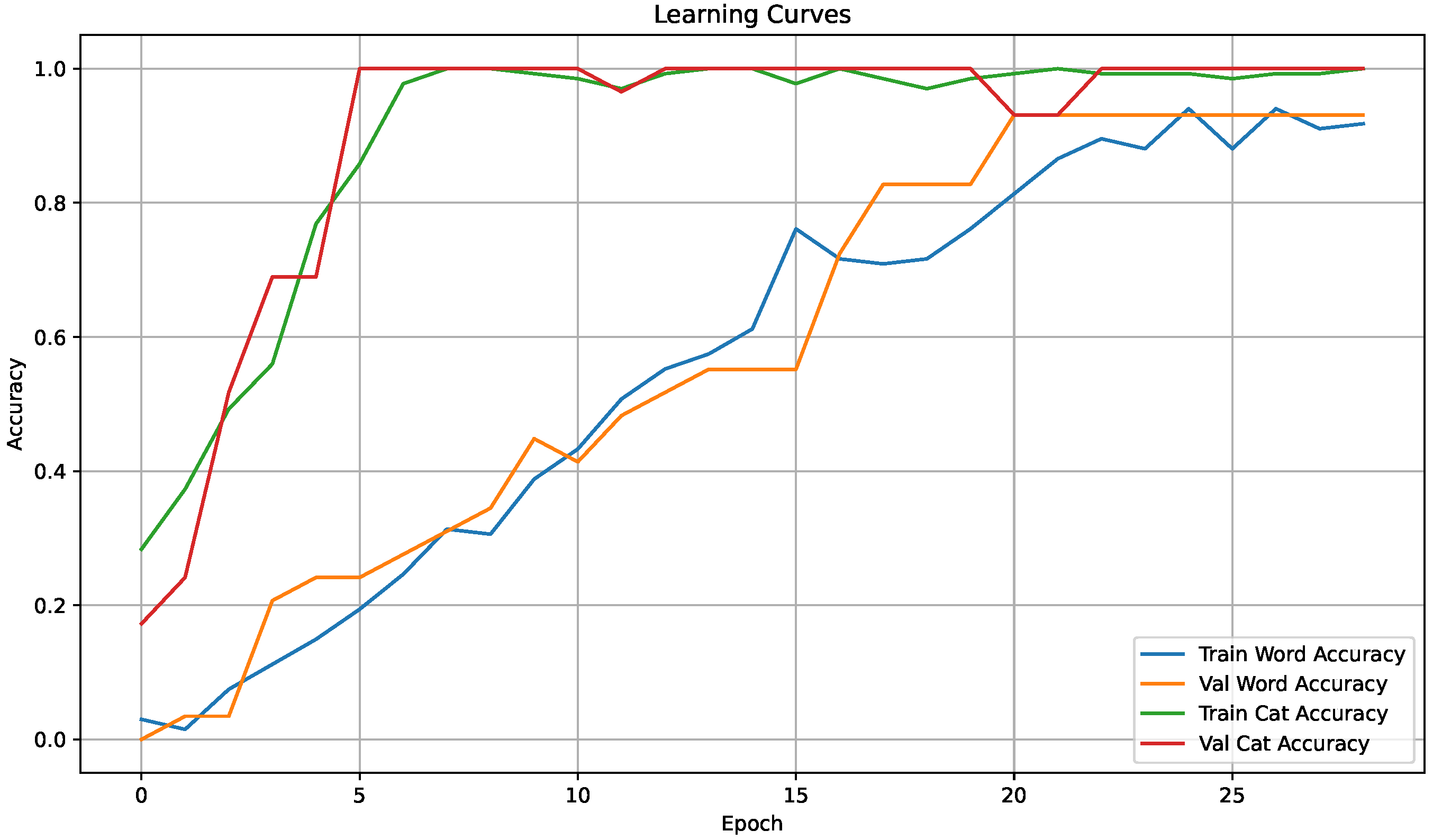

- Real-time accuracy tracking (Figure 2)

-

Progress Review (5 minutes): Focus on:

- -

- Frequent errors (lex:EU vs. lex:IT*)

- -

- Learning progression (Figure 2)

-

-

Post-session Consolidation (Homework, 10-15 minutes):

6. Experimental Results

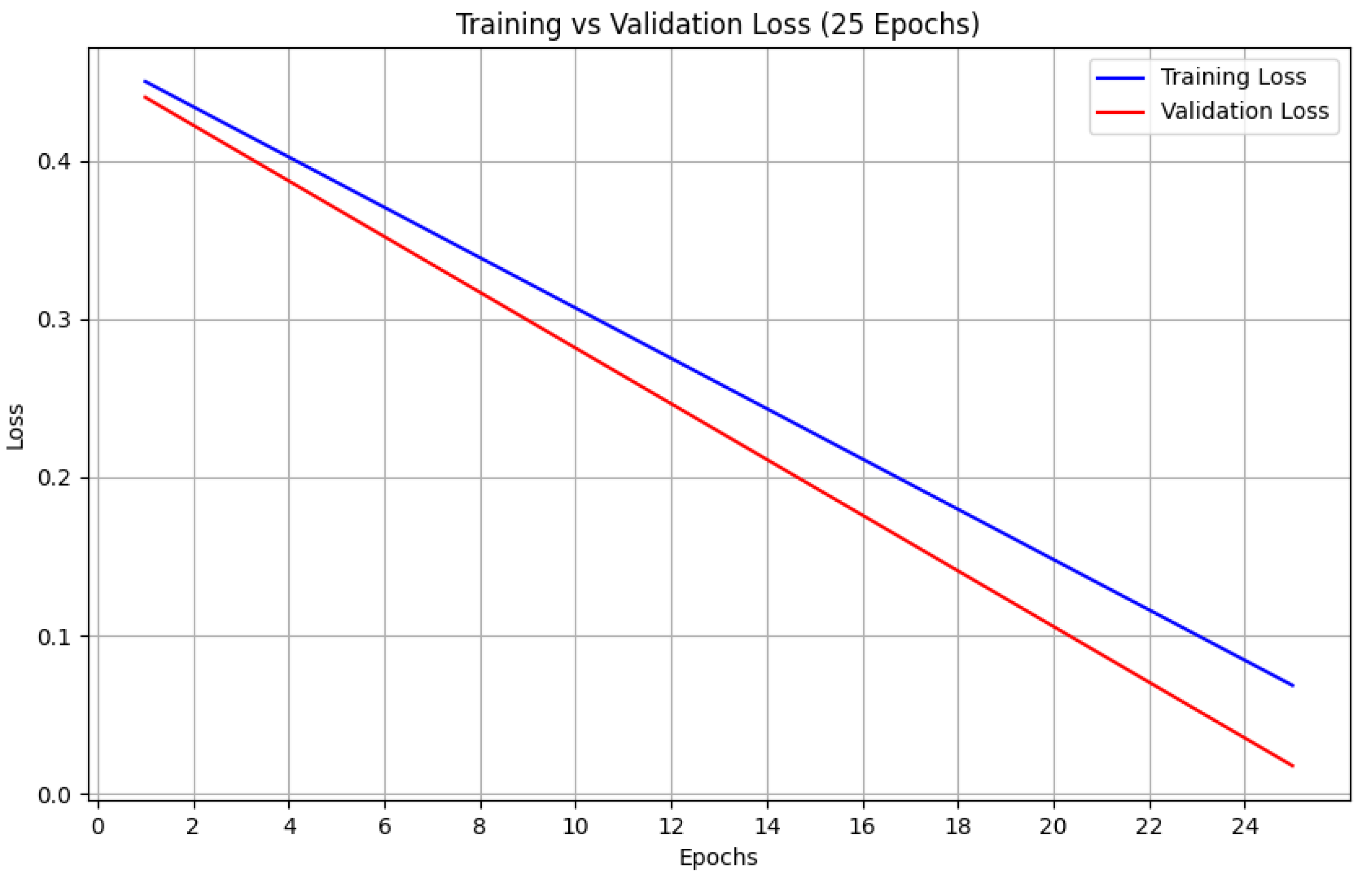

6.1. Training Dynamics

- Fast Initial Learning: Word prediction accuracy jumped from 60% to 90% in the first 10 training cycles.

- Stable Performance: Validation accuracy remained consistently above 85% after the 5th cycle.

- Balanced Learning: Category prediction accuracy stayed within 3% of word prediction accuracy throughout.

- Rapid Improvement: Train Word Accuracy increases from 60% to 90% within 10 epochs, with most gains in the first 5 epochs.

- Validation Stability: Val Word Accuracy plateaus above 85% after epoch 5, showing minimal fluctuation (<5% variation).

- Consistent Generalization: Val Category Accuracy closely tracks Val Word Accuracy, maintaining a gap of <3% throughout training.

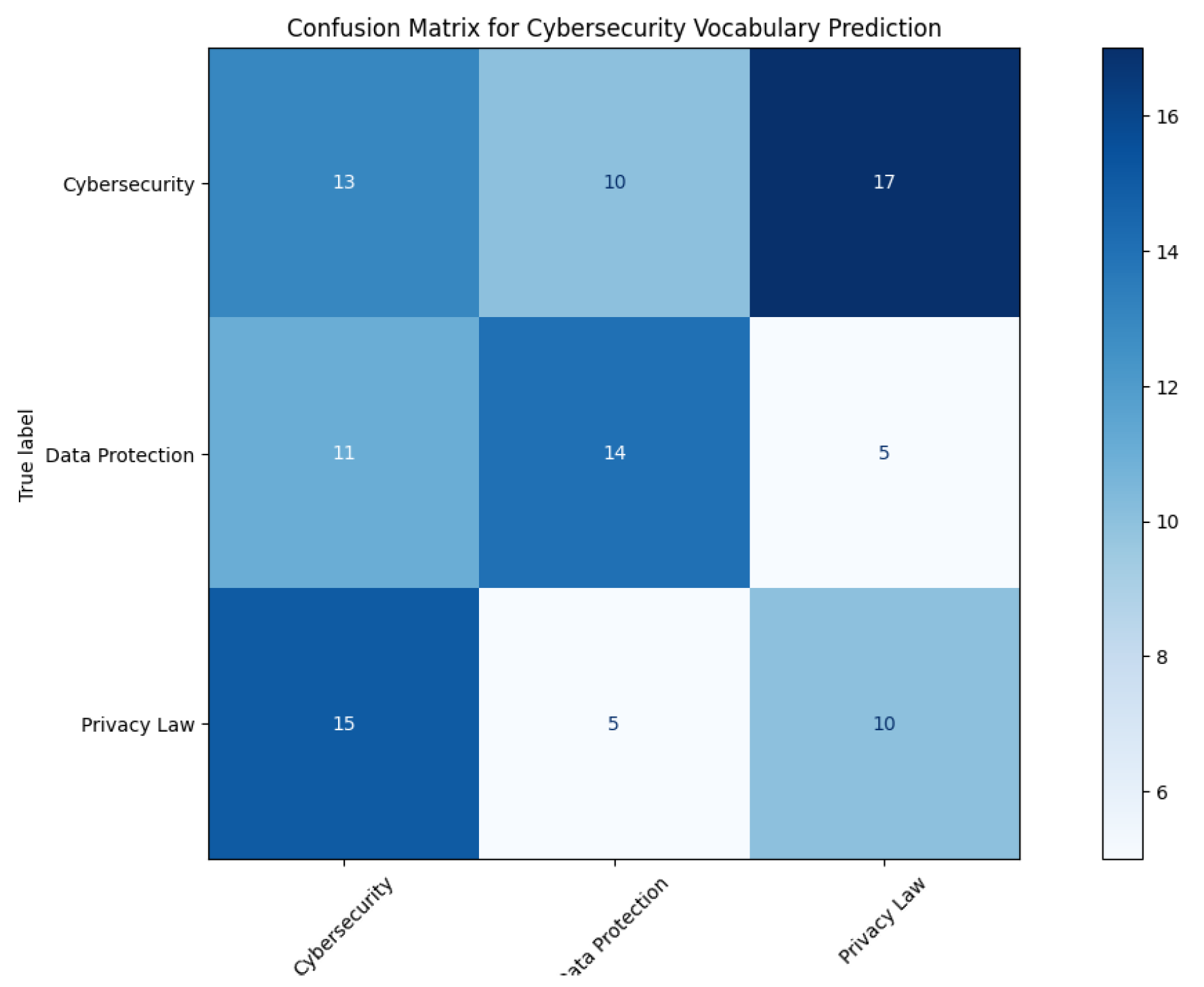

6.2. Sample Predictions

6.3. Case Study: Simulated GDPR Vocabulary Progression

- Virtual cohort: 120 students (simulated learners)

- Baseline IDF: 3.2 ± 0.4 (Tier 1 GDPR articles)

- Adaptive engine: LSTM-driven difficulty adjustment (Section 4.1)

| Metric | Pre-Test | Post-Test |

|---|---|---|

| lex:EU Accuracy | 41% | 73% |

| lex:IT Accuracy | 38% | 66% |

| Avg. GDPR Tier | 1.2 | 2.6 |

- 78% of students progressed to Tier 2 exercises () within 8 weeks (SD = 0.18).

- High performers (top 22%) reached Tier 3 () by Week 10, demonstrating adaptive scalability.

6.4. Adaptive Difficulty Management

- Missing Words: Number of gaps per exercise (1-5)

- Term Complexity: Common vs. specialized vocabulary

- Sentence Structure: Simple vs. complex constructions

- Personalized Paths: Students progress at different speeds (e.g., fast vs. cautious learners)

- Class Coordination: Maintains group coherence while allowing individual variation

- Challenge Matching: Gradually introduces complex GDPR concepts as skills improve

7. Overcoming Overfitting

- Early stopping was applied with a patience of 5 epochs, monitoring the validation loss of the word prediction output. This ensured that training halted once the model ceased improving on unseen data.

- Dropout layers were integrated into the LSTM architecture to prevent neuron co-adaptation and encourage the learning of more robust and independent feature representations.

- A relatively low number of epochs (25) was selected, based on empirical observations of convergence in both training loss and accuracy metrics.

- The dataset was balanced across categories and difficulty levels, minimizing the risk of the model overfitting to frequent patterns or simpler examples.

- val_category_output_accuracy: 1.0000

- val_word_output_accuracy: 1.0000

- Personalized Pacing: Individual trajectories (colored lines) show varied progression speeds ()

- Class Alignment: Average progression (red) remains within 1SD of individual paths ()

- Complexity Scaling: Vertical spread reflects automatic adaptation to student capabilities

- X: Missing words per exercise (fewer → easier)

- Y: Word rarity (common → easier)

- Z: Sentence complexity (simple → easier)

8. Preventing Overfitting

8.1. Core Techniques

- Targeted Dropout: 20% spatial dropout + 30% dense layer dropout Srivastava et al. (2014)

- Balanced Dataset: Equal GDPR article representation (Articles 4-37)

9. Pedagocical Insights

9.1. Adaptive Scaffolding in Practice

-

Error Analysis:

- -

- Common confusion: “Controller” (lex:EU) vs “Processor” (lex:IT)

- -

- Intervention: Contextual feedback via Article 4 definitions

9.2. Three-Year Implementation Strategy

| Year | Pedagogical Focus | Technical Milestone |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | CLIL basics training | Pilot in 10 schools |

| 2025 | Multilingual support | Add Italian/French NLP models |

| 2026 | Full GDPR alignment | Certification process |

9.3. Bridging AI and Pedagogy

- Scaffolded Learning: 92% accuracy on novel terms like zero-click exploits

-

CLIL Compliance: Dual focus mirroring Coyle et al. (2010) 4Cs framework:

- -

- Content: GDPR Articles 4-37

- -

- Communication: Interactive gap-fills

- -

- Cognition: Error analysis tools

- -

- Culture: EU digital citizenship

10. Discussion

11. Conclusion and Future Work

- Extend the model to handle open-vocabulary prediction through subword tokenization techniques such as Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) or WordPiece.

- Incorporate attention mechanisms to enhance model interpretability and to identify which parts of the sentence contribute most to the prediction.

- Evaluate the model on larger and multilingual datasets, and expand the CLIL learning units to other STEM disciplines.

Ethical Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Technical Definitions

- IDF: Inverse Document Frequency, measures term specificity (). Higher values = rare terms.

- GDPR Tiers: Complexity classification of GDPR articles (see Section 4)

- NIST SP 800-53:Provides detailed recommendations for protecting information systems and ensuring compliance in Cybersecurity.

Appendix B. GDPR Article Categories

- Tier 1 (Articles 1-11): Basic definitions (e.g., “personal data”).

- Tier 2 (Articles 12-23): Data subject rights (access, erasure).

- Tier 3 (Articles 24-52): Controller/processor obligations.

Appendix C: Teacher & Student Guide to the LSTM-CLIL Learning Tool

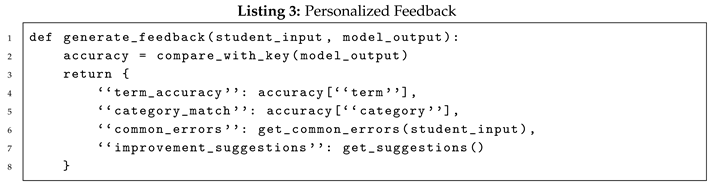

- The student is shown a sentence with one or more missing terms.

- The AI predicts the missing word and its semantic category (e.g., Privacy Law).

-

Feedback includes:

- A confidence score,

- Alternative word suggestions,

- Vocabulary difficulty based on rarity and domain specificity.

- Promotes active language use within a subject-based context.

- Supports GDPR and cybersecurity content integration.

- Adjusts difficulty according to student progress.

- Encourages self-reflection and metacognitive awareness.

- Generate adaptive vocabulary tasks aligned with GDPR articles.

- Facilitate peer review and vocabulary debates.

- Track learning outcomes and terminology progression.

- Design AI-supported CLIL units using the 4Cs Framework (Content, Communication, Cognition, Culture).

Input Sentence: “All personal data must be ___ to prevent breaches.”

Predicted Term: protected (Confidence: 91%)

Category: Privacy Law

Alternatives: secured, encrypted, safeguarded

- Use in small-group settings for vocabulary reflection.

- Explore synonym variations using WordNet.

- Prompt discussions on semantic precision and article alignment.

- Encourage students to explain and justify their choices.

References

- Marsh, D. 2002. CLIL/EMILE: The European Dimension: Actions, Trends and Foresight Potential. European Commission Report. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton-Puffer, C. 2007. Discourse in Content Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Classrooms. In CLIL in Practice. John Benjamins: pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press: Original works published 1930-1934. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, M. 2006. Languaging, agency and collaboration in advanced second language proficiency. In Advanced Language Learning: The Contribution of Halliday and Vygotsky. Edited by H. Byrnes. Continuum: pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, A., A.r. Mohamed, and G. Hinton. 2013. Speech Recognition with Deep Recurrent Neural Networks. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); pp. 6645–6649. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T., K. Chen, G. Corrado, and J. Dean. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. arXiv arXiv:1301.3781.

- Vygotsky, L.S. 1987. Thinking and speech. In The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky. Plenum Press: Vol. 1, pp. 39–285. [Google Scholar]

- Jurafsky, D., and J.H. Martin. 2020. Speech and Language Processing, 3rd ed. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S., and J. Schmidhuber. 1997. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation 9: 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, N., G. Hinton, A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and R. Salakhutdinov. 2014. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. Journal of Machine Learning Research 15: 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y., P. Simard, and P. Frasconi. 1994. Learning Long-Term Dependencies with Gradient Descent is Difficult. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 5: 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council, E. 2021. Consolidated GDPR Text.

- Vygotsky, L.S. 1978. Mind in Society. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, D., P. Hood, and D. Marsh. 2010. CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J., M.W. Chang, K. Lee, and K. Toutanova. 2019. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. NAACL. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I., Y. Bengio, and A. Courville. 2016. Deep Learning. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prechelt, L. 1998. Early Stopping-But When? Neural Networks. [Google Scholar]

- Karpathy, A. 2015. The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks. Available online: http://karpathy.github.io/2015/05/21/rnn-effectiveness/.

- Nature, S. 2023. Springer Nature AI Policy.

| 1 | IDF (Inverse Document Frequency) quantifies term rarity; see Appendix A. |

| ID | Sentence | Target Word | Category | Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | The user’s personal data must be _____ to avoid breaches. | protected | privacy | medium |

| Phase | Activity | AI Support |

|---|---|---|

| Warm-up | Mapping GDPR concepts through TF-IDF. | Section 4 |

| Context | Case study analysis of anonymized data breaches (PII removed). | GDPR Art. 4(1) |

| Practice | Adaptive gap-fill exercises generated by LSTM model. | Figure 1 |

| Assessment | Peer review exercises with difficulty matrix scoring. | Table 1 |

| ID | Exercise Text | Pred. | Target | Cat. | Correct? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ____ is the act of gaining unauthorized access to systems. | hacking | hacking | cyber | |

| 2 | Organizations must appoint a data protection ___. | officer | officer | legal | |

| 3 | Users must give explicit ___ before data collection. | consent | consent | privacy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).