1. Introduction

Idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) is a condition characterized by gait disturbances, cognitive impairment, and urinary incontinence in the absence of precipitating events such as subarachnoid hemorrhage or meningitis [

1]. It is thought to result from impaired absorption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain. The current understanding of CSF absorption pathways has evolved significantly over recent years [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. The glymphatic system and intra-arterial intramedullary drainage pathways have thus emerged as the major contributors to CSF clearance [

5]. These insights provide a more nuanced view of the pathophysiology of hydrocephalus. Some patients with untreated iNPH show a gradual reduction in ventricular forward flow that parallels the worsening of their clinical symptoms and can eventually lead to irreversible progressive ischemic damage in the brain [

10].

Herein, we report two cases of iNPH in which the clinical symptoms were complicated by progressive cerebral ischemic damage and became apparent only following systemic infections. In one case, the patient presented with transient neurological symptoms that mimicked cerebrovascular disease during a course of sepsis, and the second appeared to resemble cerebral infarction. Both cases suggest that infection-related disturbances to CSF dynamics may have triggered the overt manifestations of underlying iNPH.

2. Case Presentation

Case 1

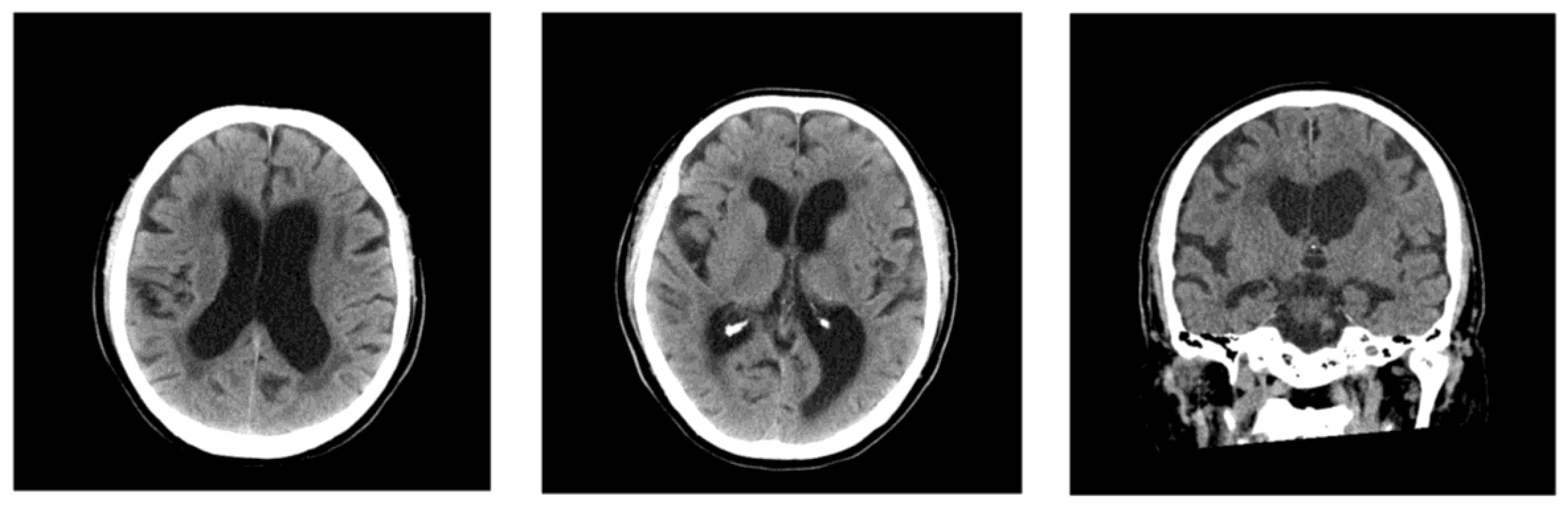

An 82-year-old man presented to our center with a one-week history of transient generalized weakness followed by fever beginning four days prior to admission. He was initially evaluated at another hospital, where he exhibited lower limb weakness. Head computed tomography (CT) revealed bilateral periventricular hypodensities. His symptoms subsequently improved, and he was transferred to our institution for further evaluation.

His medical history included hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. He was taking medications for these conditions and had no history of smoking or alcohol consumption. On admission, his height, weight, and body mass index were 180 cm, 77 kg, and 23, respectively. His vital signs at the time were: blood pressure, 115/58 mmHg; heart rate, 80 bpm; respiratory rate, 22 breaths per min; SpO₂, 92% on room air; and body temperature, 37.3 °C. Neurological examination revealed a Glasgow Coma Scale score of E4V4M5 and disorientation. The patient’s cranial nerves were intact, with no visual field defects, extraocular movement limitations, or neck stiffness. Right-sided arm weakness was noted (positive Barré’s sign), tendon reflexes were normal, and no sensory deficits or paresthesia were noted. Laboratory tests revealed a significant elevation in C-reactive protein levels, as well as increased blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and D-dimer levels (

Table 1).

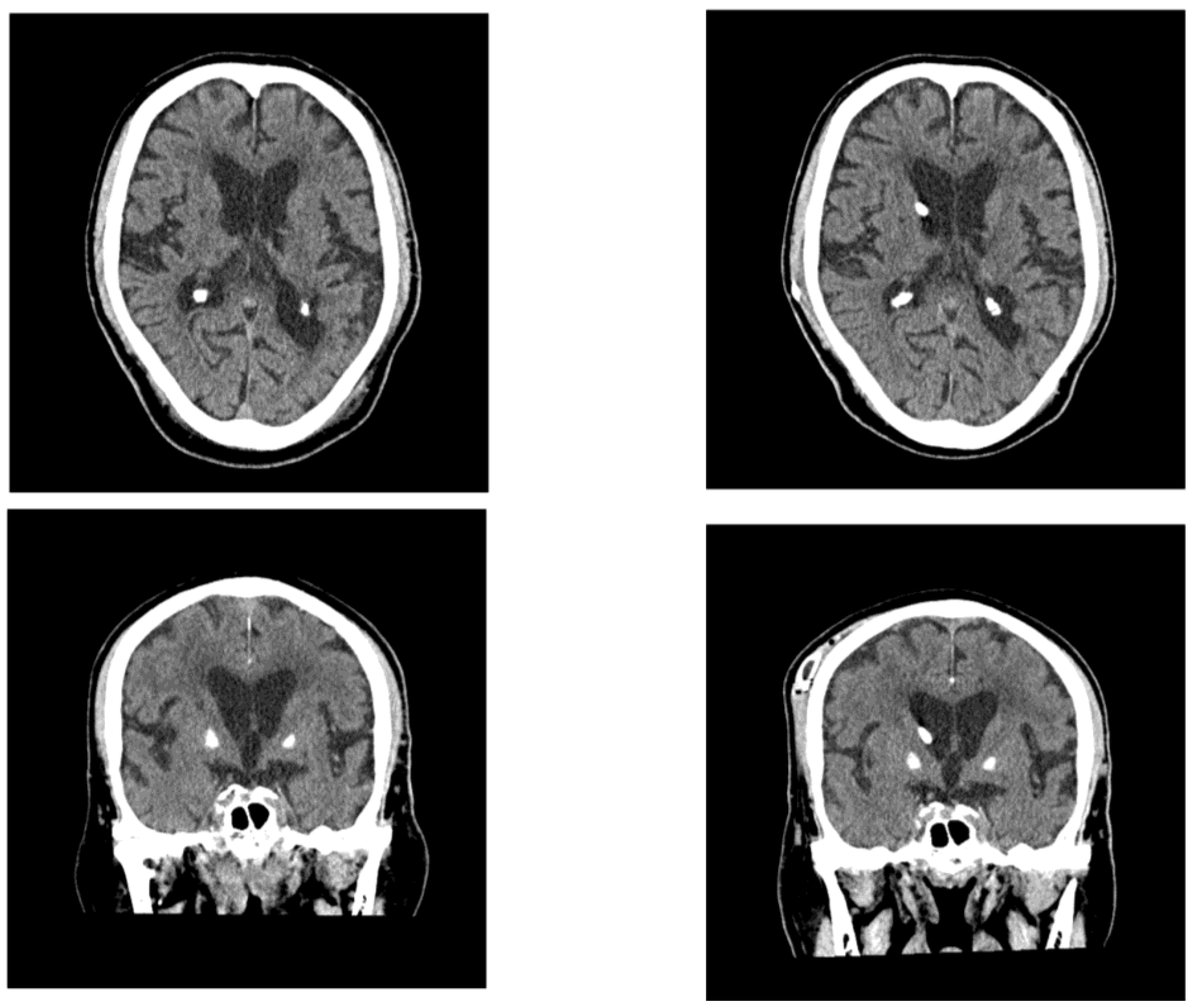

Initial head CT demonstrated bilateral periventricular hypodensities, and the patient’s Evans index [

11] was 0.34 (

Figure 1). Mild enlargement of the Sylvian fissures was noted and the subarachnoid spaces over the high convexity appeared slightly narrowed, suggesting the absence of disproportionally enlarged subarachnoid space hydrocephalus (DESH) features. On hospital days 1 and 2, the four sets of blood cultures performed tested positive for Gram-negative rods, and treatment with intravenous meropenem was initiated for sepsis. Because of the patient’s elevated D-dimer levels and clinical presentation, transient ischemic attack or cerebral venous thrombosis were considered; however, echocardiography and lower-extremity venous ultrasound revealed no evidence of thrombosis.

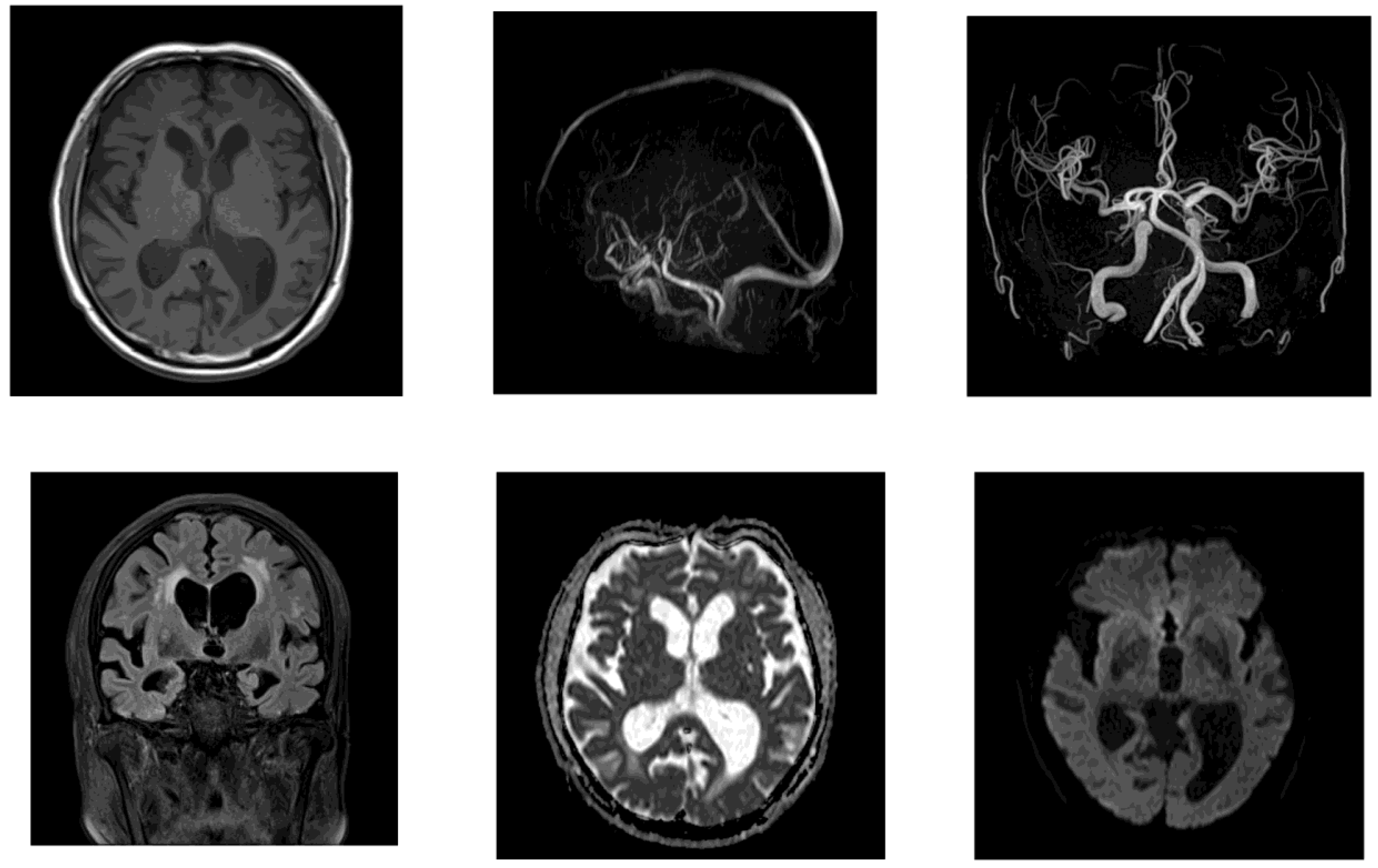

On day 2, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed no signs of acute cerebral infarction; however, chronic lacunar infarcts were present, alongside periventricular white matter changes. No arterial or venous thrombosis, or stenosis, was observed (

Figure 2).

On day 3, the causative organism was identified to be

Klebsiella pneumoniae. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT and urinalysis revealed liver abscess, urinary tract infection, and bacteremia. Based on antimicrobial susceptibility testing, treatment was de-escalated to ceftriaxone. Whole-spine MRI revealed cervical spinal canal stenosis between the C3–C6 levels. On day 9, a tap test was performed, and lumbar puncture revealed an opening pressure of 6 cmH₂O. The CSF appeared clear with slight xanthochromism. A total drainage volume of 13 mL was achieved. Laboratory analysis revealed a glucose level of 115 mg/dL, protein concentration of 38 mg/dL, and white cell count of 2 cells/μL—findings which were inconsistent with meningitis. The absence of CSF pulsation and the low drainage volume raised the possibility of impaired CSF outflow because of cervical spinal canal stenosis and consequent communication disturbance. The patient’s gait disturbance improved significantly after the tap test was performed. Although his overall Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score remained low, improvement was noted in the orientation component. Based on these findings, probable iNPH was diagnosed and a 12 mm brain abscess was incidentally found in the right basal ganglia (

Figure 3-a).

By day 24, follow-up contrast-enhanced MRI confirmed encapsulation of the abscess (

Figure 3-b). As the infection showed signs of improvement, a six-week course of ceftriaxone was planned before surgical intervention. On day 49, considering the possibility of impaired CSF circulation caused by cervical spinal canal stenosis and the presence of a right basal ganglia abscess, a left-sided ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt was placed. Postoperatively, the patient showed significant improvements in both his gait disturbance and cognitive function (

Table 2). He soon regained ambulatory independence and was discharged.

Case 2

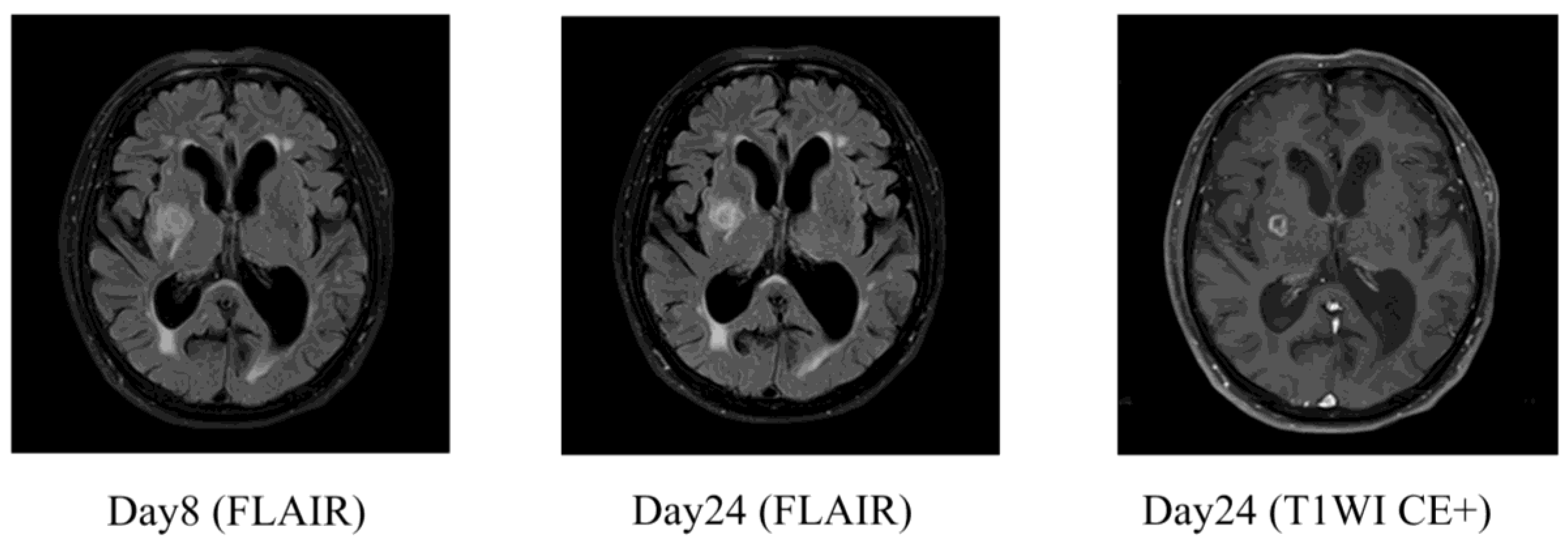

An 80-year-old man with a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, whose case was being managed at a nearby clinic, presented to our center with generalized muscle weakness. He had a several-year history of progressive gait disturbance, cognitive decline, and urinary incontinence. Two weeks prior to his admission, his frequency of falls increased significantly. Two days before admission, his urinary incontinence worsened, leading to a bedridden state.

His body temperature on arrival was 37.5 °C. Laboratory tests revealed an increased inflammatory response and mild dehydration (

Table 3). Blood cultures were obtained, and bacteremia with

Stapylococcus haemolyticus was confirmed. Intravenous antibiotic therapy was promptly initiated. Brain MRI revealed enlarged lateral ventricles and features consistent with DESH. The patient’s Evans index was 0.38, and his corpus callosum angle was measured at < 90°, supporting the diagnosis of iNPH Acute cerebral infarction was identified in the corona radiata, indicating the coexistence of hydrocephalus and ischemic stroke (

Figure 4).

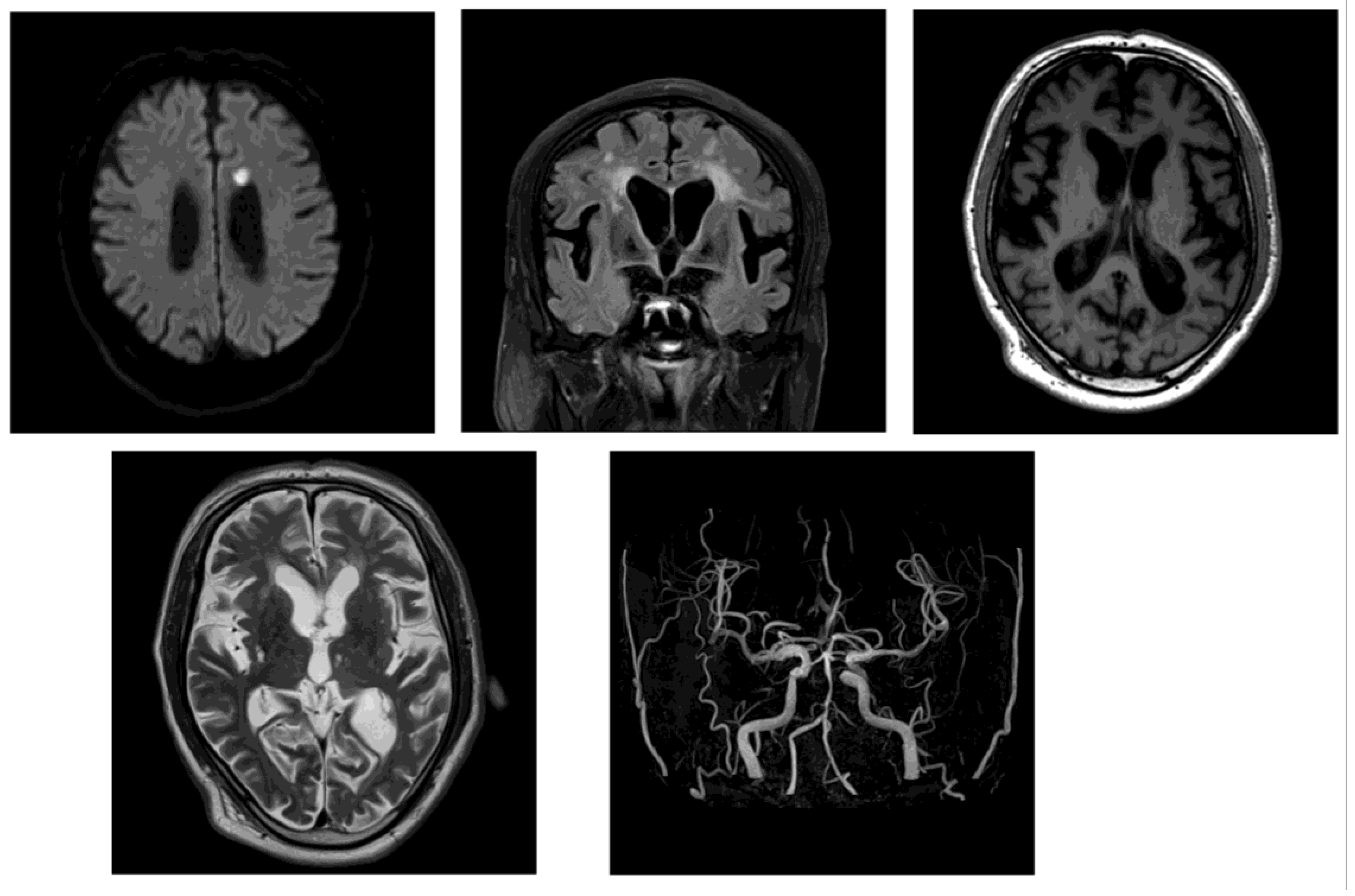

Initial management included the continuation of antibiotic therapy along with intravenous ozagrel sodium for antiplatelet effects, followed by the initiation of oral clopidogrel. A tap test was performed on day 21 of the patient’s hospitalization. His gait velocity improved from 1.255 to 1.339 steps/s thereafter, and his MMSE score increased from 11 to 16, suggesting responsiveness to CSF drainage. Lumber MRI showed spinal canal stenosis. On day 41, a right-sided VP shunt was inserted. Postoperatively, the patient demonstrated a significant improvement in independent ambulation (

Table 4). Mild improvements in cognitive function and urinary symptoms were also observed. A follow-up CT performed on day 50 revealed a reduction in ventricular size (

Figure 5).

By day 64, the patient's overall symptoms and functional status had improved, and he was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital. At the time of writing this report, he is able to walk independently and has returned home with full independence in his daily activities.

3. Discussion

These two cases suggest a potential relationship between sepsis and the clinical manifestations or exacerbation of iNPH. In particular, systemic infection may induce changes in CSF dynamics, thereby contributing to the worsening of iNPH-related symptoms. One of the central mechanisms potentially involved is sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE), a diffuse brain dysfunction triggered by systemic inflammation in the absence of direct central nervous system infection [

2,

3]. SAE is increasingly recognized as a multifactorial condition involving neuroinflammation, microcirculatory failure, mitochondrial dysfunction, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption [

12]. Several biological processes associated with SAE may play roles in altering CSF physiology [

4]. First, systemic inflammation can activate vascular endothelial cells and disrupt the BBB, allowing neurotoxic substances to enter the brain parenchyma. Second, cerebral autoregulation may be impaired, resulting in unstable cerebral perfusion. Third, mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to cellular energy failure and neuronal apoptosis. Finally, alterations in neurotransmitter synthesis and metabolism can occur as a result of increased protein catabolism and systemic inflammatory stress. In such cases, pre-existing chronic cerebral ischemia and latent CSF circulation disturbances may have been highlighted or exacerbated by the systemic effects of sepsis, resulting in an overt clinical presentation of iNPH. This interpretation is consistent with recent insights into the complex and dynamic nature of CSF absorption and circulation.

From a clinical standpoint, such cases highlight a critical point: when patients present with a combination of gait disturbance and ventricular enlargement in the setting of active infection, there is a risk that the diagnosis of iNPH may be overlooked. The possibility that infection-induced alterations in CSF dynamics contribute to the manifestation or worsening of hydrocephalus should be considered, particularly in older patients with comorbidities or chronic ischemic changes.

Moreover, timely shunt surgery following appropriate antimicrobial and stroke treatments may lead to substantial clinical improvement in patients with hydrocephalus who develop acute ischemic stroke in the context of systemic infection. These findings reinforce the importance of recognizing hydrocephalus as a potential contributor to cerebral ischemia, and emphasize the need for personalized and multidisciplinary treatment strategies. Overall, these cases support the hypothesis that iNPH may emerge or worsen as a result of systemic inflammatory insults such as sepsis and that shunt surgery (when appropriately timed) can facilitate significant functional recovery.

4. Conclusions

These two cases represent rare clinical presentations in which the symptoms of iNPH became overt following systemic infections such as sepsis. We report these findings to highlight the possibility that similar mechanisms may be present in other patients with comparable courses, and provide insights for future clinical practice. In particular, patients with hydrocephalus who develop acute ischemic stroke caused by progressive cerebral ischemic damage may experience substantial symptomatic improvement following shunt surgery, once the underlying infection and stroke have been appropriately treated. It is imperative to recognize the potential association between hydrocephalus and cerebral ischemia. Tailoring treatment strategies to account for this relationship may lead to better clinical outcomes in complex cases involving both systemic inflammatory conditions and disruptions to CSF circulation.

Supplementary Materials

None

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W. and K.B.; methodology, Y.S.; software, S.W.; validation, Y.S.; formal analysis, S.W.; investigation, S.W., K.B., Y.K.; resources, K.B., Y.K.; data curation, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; visualization, S.W.; supervision, E.I.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, None. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mito Kyodo General Hospital, Tsukuba University Hospital Mito Area Medical Education Center (protocol code:NO 25-05 and date of approval: 21, Apr. 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. However, due to privacy and ethical restrictions, raw patient data are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BBB |

Blood-Brain Barrier |

| CSF |

Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| DESH |

Disproportionally Enlarged Subarachnoid Space Hydrocephalus |

| iNPH |

Idiopathic Normal-Pressure Hydrocephalus |

| MMSE |

Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| SAE |

Sepsis-Associated Encephalopathy |

| VP |

Ventriculoperitoneal |

References

- Nakajima, M.; Yamada, S.; Miyajima, M.; et al. Guidelines for Management of Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (Third Edition): Endorsed by the Japanese Society of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo) 2021, 61, 63–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobone, E.; Bailly-Salin, J.; Polito, A.; et al. Sepsis-associated encephalopathy and its differential diagnosis. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37 (Suppl 10), S331–S336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gofton, T.E.; Young, G.B. Sepsis-associated encephalopathy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 8, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfister, D.; Siegemund, M.; Dell-Kuster, S.; et al. Cerebral perfusion in sepsis-associated delirium. Crit. Care 2008, 12, R63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedergaard, M. Garbage truck of the brain. Science 2013, 340, 1529–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louveau, A.; Smirnov, I.; Keyes, T.J.; et al. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 2015, 523, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelhardt, B.; Vajkoczy, P.; Weller, R.O. The movers and shapers in immune privilege of the CNS. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møllgård, K.; Beinlich, F.R.M.; Kusk, P.; et al. A mesothelium divides the subarachnoid space into functional compartments. Science 2023, 379, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, M.; Uchino, T.; Yamada, S. Description of the latest neurofluid absorption mechanisms with reference to the linkage absorption mechanisms between extravascular fluid pathways and meningeal lymphatic vessels. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 2022, 59, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollato, A.; Tenenbaum, R.; Bahl, G.; et al. Changes in aqueductal CSF stroke volume and progression of symptoms in patients with unshunted idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2008, 29, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, W.A. An encephalographic ratio for estimating ventricular enlargement and cerebral atrophy. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 1942, 47, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazeraud, A.; Pascal, Q.; Verdonk, F.; Heming, N. Sepsis-associated encephalopathy: A comprehensive review. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).