Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Information

2.2. Solid-Phase Synthesis of Modified TFOs with P (205-Ps1 and 205-Ps2, 5992-Ps1, and 5992-Ps2)

2.3. Triplex Formation Analysis Using Nondenaturing Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native PAGE)

2.4. Evaluation of Anticancer Activities of TFO Using the WST-8 Assay

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation of the Thermodynamic Stability of Triplexes with HER2 Gene Sequences

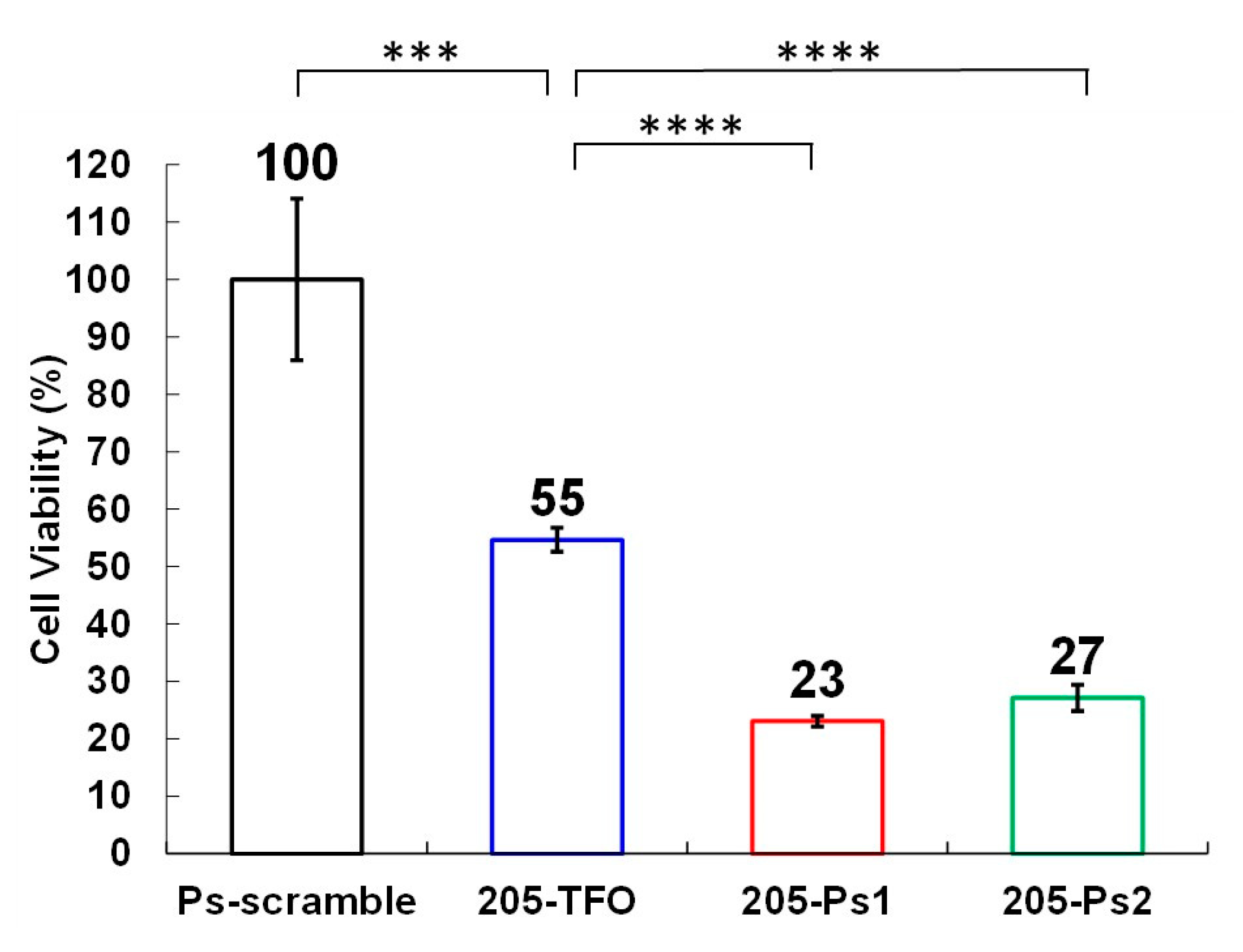

3.2. Evaluation of the Anticancer Activities of TFOs Against HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Cells

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Felsenfeld, G.; Davies, D.R.; Rich, A. FORMATION OF A THREE-STRANDED POLYNUCLEOTIDE MOLUCULE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 2023–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank-Kamenetskii, M.D.; Mirkin, S.M. TRIPLEX DNA STRUCTURES. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 64, 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossella, J.A.; Kim, Y.J.; Shin, H.; Richards, E.G.; Fresco, J.R. Relative specificities in binding of Watson - Crick base pairs by third strand residues in a DNA pyrimidine triplex motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21, 4511–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuong, N.T.; Hélène, C. Sequence-Specific Recognition and Modification of Double-Helical DNA by Oligonucleotides. Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, 666–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karympalis, V.; Kalopita, K.; Zarros, A.; Carageorgiou, H. Regulation of Gene Expression via Triple Helical Formations. Biochemistry, 2004, 69, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duca, M.; Vekhoff, P.; Oussedik, K.; Halby, L.; Arimondo, P.B. The triple helix: 50 years later, the outcome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 5123–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, C.; Deng, Y.; Peng, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y. Triplex-forming oligonucleotides as an anti-gene technique for cancer therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1007723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik Tiwari, M.; Rogers, F.A. XPD-dependent activation of apoptosis in response to triplex-induced DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 8979–8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik Tiwari, M.; Adaku, N.; Peart, N.; Rogers, F.A. Triplex structures induce DNA double strand breaks via replication fork collapse in NER deficient cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 7742–7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik Tiwari, M.; Colon-Rios, D.A.; Rao Tumu, H.C.; Liu, Y.; Quijano, E.; Krysztofiak, A.; Chan, C.; Sang, E.; Braddock, D.T.; Suh, H.-W.; Saltzman, W.M.; Rogers, F.A. Direct targeting of amplified gene loci for proapoptotic anticancer therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikame, Y.; Yamayoshi, A. Recent Advancements in Development and Therapeutic Applications of Genome-Targeting Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotides and Peptide Nucleic Acids. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hari, Y.; Obika, S.; Imanishi, T. Towards the Sequence-Selective Recognition of Double-Stranded DNA Containing Pyrimidine-Purine Interruptions by Triplex-Forming Oligonucleotides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2875–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikame, Y.; Toyama, H.; Dohno, C.; Wada, T.; Yamayoshi, A. Development and functional evaluation of a psoralen-conjugated nucleoside mimic for triplex-forming oligonucleotides. Commun. Chem. 2025, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catapano, C.V.; McGuffie, E.M.; Pacheco, D.; Carbone, G.M.R. Inhibition of gene expression and cell proliferation by triple helix-forming oligonucleotides directed to the c-myc gene. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 5126–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-. Y, Bi, G.; Miller, P.S. Triplex Formation by Oligonucleotides Containing Novel Deoxycytidine Derivatives. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996, 24, 2606–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amosova, O.A.; Fresco, J.R. A search for base analogs to enhance third-strand binding to ‘inverted’ target base pairs of triplexes in the pyrimidine/parallel motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 4632–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.L.; McLaughlin, L.W. Use of pKa Differences to Enhance the Formation of Base Triplets Involving C−G and G−C Base Pairs. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 7468–7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, H.; Taniguchi, Y.; Sasaki, S. Aminopyridinyl–Pseudodeoxycytidine Derivatives Selectively Stabilize Antiparallel Triplex DNA with Multiple CG Inversion Sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 12445–12449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Taniguchi, Y.; Okamura, H.; Sasaki, S. Modification of the aminopyridine unit of 2′-deoxyaminopyridinyl-pseudocytidine allowing triplex formation at CG interruptions in homopurine sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 8679–8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notomi, R.; Sasaki, S.; Taniguchi, Y. Recognition of 5-methyl-CG and CG base pairs in duplex DNA with high stability using antiparallel-type triplex-forming oligonucleotides with 2-guanidinoethyl-2′-deoxynebularine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 12071–12081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milo, R.; Phillips, R. CELL BIOLOGY by the numbers, Garland Science, Oxford, 2016; pp. 92–93.

|

KS value (106 M−1) at 20 mM Mg2+ |

KS value (106 M−1) at 5 mM Mg2+ |

|

|---|---|---|

| 205-TFO | 30 | 14 |

| 205-Ps1 | 40 | 30 |

| 205-Ps2 | 8 | 18 |

| 5992-TFO | 77 | 107 |

| 5992-Ps1 | 87 | 58 |

| 5992-Ps2 | 121 | 93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).