Submitted:

23 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Panorama of Food Production and Consumption over the World

1.2. Current Perspectives for Measures Planned to Reduce Emissions from the World Food System in the Coming Decades

2. Some Possible Measures to move Towards a Healthier and More Sustainable Future

2.1. Implement New Strategies to Increase the Proportion of Plant Foods in the Diet of the Current Urban Population, Within the Concept of “Smart Food”

2.2. Reduce the Environmental Impact in Food Production

3. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rutter, H.; Cavill, N.; Bauman, A.; Bull, F. Systems approaches to global and national physical activity plans. Bull World Health Organ 2019, 97, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellulu, M.; Abed, Y.; Rahmat, A.; Ranneh, Y.; Ali, F. Epidemiology of obesity in developing countries: challenges and prevention. Global Epidemic Obesity 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.; Sherwani, A.Y.; Mahri, S.A.; Malik, S.S.; Mohammad, S. Why Are Obese People Predisposed to Severe Disease in Viral Respiratory Infections? Obesities 2023, 3, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutari, C.; Mantzoros, C.S. A 2022 update on the epidemiology of obesity and a call to action: as its twin COVID-19 pandemic appears to be receding, the obesity and dysmetabolism pandemic continues to rage on. Metabolism. 2022, 133, 155217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, E.J.; LeRoith, D. Obesity and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2022, 41, 463–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu Chung Chooi, Y.C.; Ding, C.; Magkos, F. The epidemiology of obesity. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2019, 92, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F.; Khalid, O.; Haq, N.; Khan, A.R.; Bilal, K.; Madan, S.A. Diet-Right: A Smart Food Recommendation System. KSII Trans. INTERNET Inf. Syst. 2017, 11, 2910–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, J.G.; Balevic, S.; Sinha, J.; Perrin, E.M.; Wang, J.; Edginton, A.N.; Gonzalez, D. Characterizing Pharmacokinetics in Children With Obesity—Physiological, Drug, Patient, and Methodological Considerations. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 818726. [CrossRef]

- Busutil, R.; Espallardo, O.; Torres, A.; Martínez-Galdeano, L.; Zozaya, N.; Hidalgo-Vega, A. The impact of obesity on health-related quality of life in Spain. Busutil Et al. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Future Smart Food: Rediscovering Hidden Treasures of Neglected and Underutilized Species for Zero Hunger in Asia; FAO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018. Matern Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e13008. [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Dawodu, A.; Mangi, A.; Cheshmehzangi, A. Exploring Current Trends, Gaps & Challenges in Sustainable Food Systems Studies: The Need of Developing Urban Food Systems Frameworks for Sustainable Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Ng, S.W. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes. Reviews. 2022, 23, 13366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Scherer, L.; Tukker, A.; Seth, A.; Spawn-Lee, S.A.; Bruckner, M.; Gibbs, H.K.; Behrens, P. Dietary change in high-income nations alone can lead to substantial double climate dividend. Nat Food 2022, 3, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

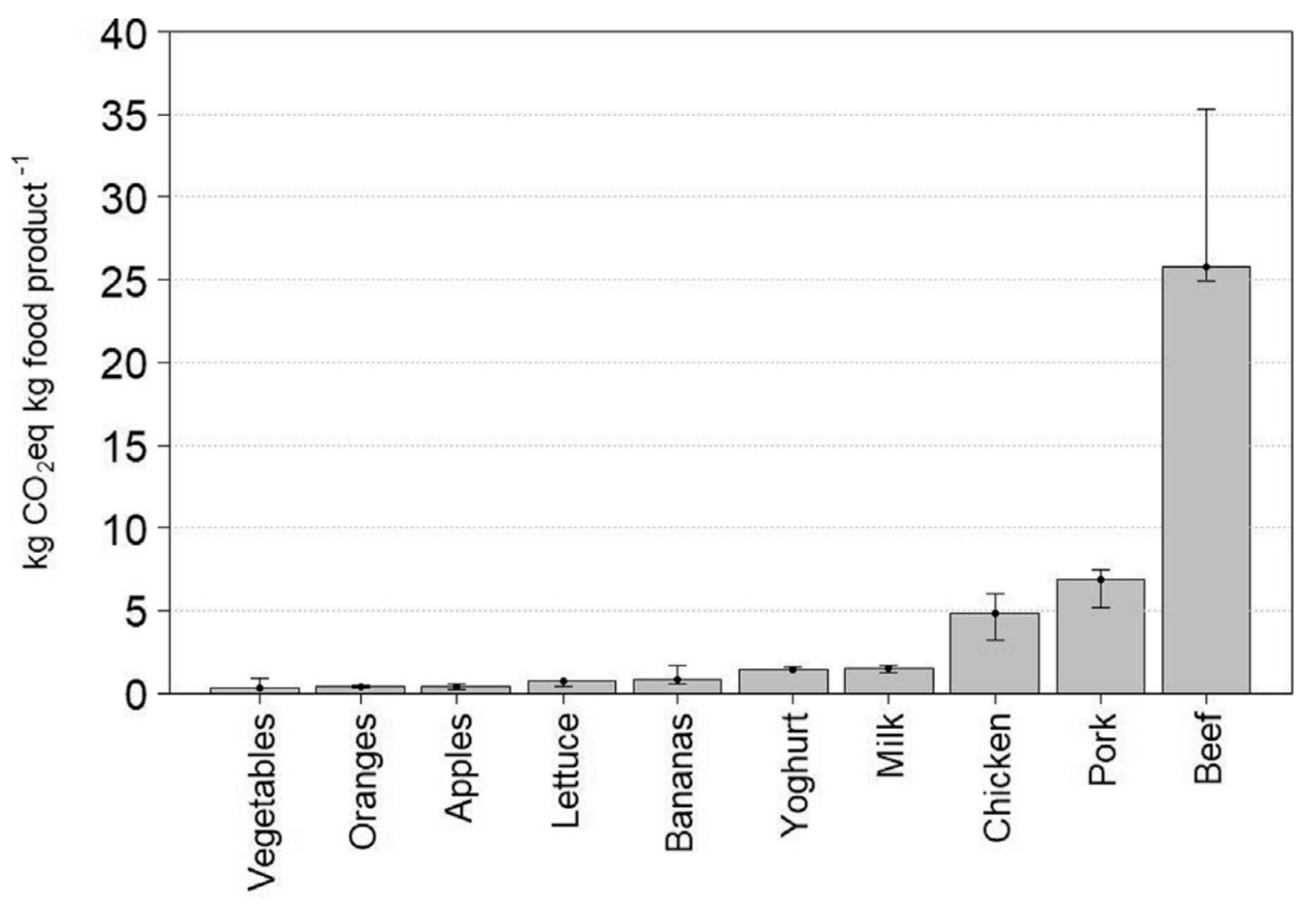

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Leip, A. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willits-Smith, A.; Aranda, R.; Heller, A.R.; Rose, D. Addressing the carbon footprint, healthfulness, and costs of self-selected diets in the USA: a population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet Planet Health 2020, 4, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; Domingo, N.G.G.; Colgan, K.; Thakrar, S.K.; Tilman, D.; Lynch, J.; Azevedo, I.L.; Hill, J.D. Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the 1.5° and 2 °C climate change targets. Science 2020, 370, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, S.; Osman, A.I.; Doran, J.; Rooney, D.W. Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 2069–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, E.; Guo, M.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Low-carbon diets can reduce global ecological and health costs. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller MC, Willits-Smith A, Meyer R, Keoleian GA, Rose, D. Greenhouse gas emissions and energy use associated with production of individual self-selected US diets. Env. Res Lett 2018, 13, 044004. [CrossRef]

- Batlle-Bayer, L.; Bala, A.; García-Herrero, I.; Lemaire, E.; Song, G.; Aldaco, R.; Fullana-Palmer, P. The Spanish Dietary Guidelines: A potential tool to reduce greenhouse gas emissions of current dietary patterns. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z. Does Internet use connect smallholder farmers to a healthy diet? Evidence from rural China. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1122677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockstrom, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, E.; Guo, M.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Low-carbon diets can reduce global ecological and health costs. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.A.; Baker, P.I.; Pulker, C.E.; Pollard, C.M. Sustainable, resilient food systems for healthy diets: the transformation agenda. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, R.D.; de Pee, S.; Kim, B.; McKenzie, S.; Nachman, K.; Bloem, M.W. Adoption of the ‘planetary health diet’ has different impacts on countries’ greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerford, K.B.; Miller, G.D.; Kapsak, W.R.; Brown, K.A. The Complementary Roles for Plant-Source and Animal-Source Foods in Sustainable Healthy Diets. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, D.P.; Shalloo, L.; van Zanten, H.H.E.; Schop, M.; De Boer, I.J.M. The net contribution of livestock to the supply of human edible protein: the case of Ireland. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 159, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.; Reguant-Closa, A. “Eat as If You Could Save the Planet and Win!” Sustainability Integration into Nutrition for Exercise and Sport. Nutrients 2017, 9, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theurl, M.C.; Lauk, C.; Kalta, G.; Mayer, A.; Kaltenegger, K.; Morais, T.G.; Teixeira, R.F.M.; Domingos, T.; Winiwarter, W.; Erba, K.H.; et al. Food systems in a zero-deforestation world: Dietary change is more important than intensification for climate targets in 2050. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 139353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Bermudez, Y.A.; Vincenzi, R.; Meo-Filho, P.; Sakamoto, L.S.; Lobo, R.; Benetel, G.; Lobo, A.; Matos, C.; Benetel, V.; Lima, C.G.; et al. Effect of Yerba Mate Extract as Feed Additive on Ruminal Fermentation and Methane Emissions in Beef Cattle. Animals 2022, 12, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnie, M.A.; Barlow, K.; Johnson, V.; Harrison, C. Red meats: Time for a paradigm shift in dietary advice. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, C.C.; Staffileno, B.A.; Rasmussen, H.E. Healthy Eating: How Do We Define It and Measure It? What’s the Evidence? J. Nurse Pract. 2017, 13, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, W. How Western Diet And Lifestyle Drive The Pandemic Of Obesity And Civilization Diseases. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 2221–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, M.E.; Al-Bakheit, A.; Hasan, H.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; Jahrami, H.; Rajab, D.; Afra Almashgouni, A.; Alshehhi, A.; Aljabry, A.; Aljarwan, M.; et al. Assessment of nutritional quality of snacks and beverages sold in university vending machines: a qualitative assessment. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2449–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, L.M.; Slavin, J. Impact of Pasta Intake on Body Weight and Body Composition: A Technical Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjibade, M.; Mariotti, F.; Leroy, P.; Souchon, I.; Saint-Eve, A.; Fagherazzi, G.; Soler, L.G.; Huneau, J.F. Impact of intra-category food substitutions on the risk of type 2 diabetes: a modelling study on the pizza category. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamore, L.; Ingrassia, M.; Columba, P.; Chironi, S.; Bacarella, S. Italian Consumers’ Preferences for Pasta and Consumption Trends: Tradition or Innovation? J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assassi, P.; Selwyn, B.J.; Lounsbury, D.; Chan, W.; Harrell, M.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Baseline dietary patterns of children enrolled in an urban family weight management study:associations with demographic characteristics. Child Adolesc. Obes. 2021, 4, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.M.; Slavin, J.L. The benefits of defining “snacks”. Physiology & Behavior 2018, 193, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerikanou, C.; Tagkouli, D.; Tsiaka, T.; Lantzouraki, D.Z.; Karavoltsos, S.; Sakellari, A.; Kleftaki, S.A.; Georgios Koutrotsios, G.; Giannou, V.; Zervakis, G.I.; et al. Pleurotus eryngii Chips—Chemical Characterization and Nutritional Value of an Innovative Healthy Snack. Foods 2023, 12, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.; Rao, G.; Slavin, J. The Nutrient Density of Snacks: A Comparison of Nutrient Profiles of Popular Snack Foods Using the Nutrient-Rich Foods Index. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2017, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyl, C.; Bresciani, A.; Marti, A. Recent Progress on Improving the Quality of Bran-Enriched Extruded Snacks. Foods 2021, 10, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Guillermic, R.M.; Nadimi, M.; Paliwal, J.; Koksel, F. Physical and microstructural quality of extruded snacks made from blends of barley and green lentil flours. Cereal Chemistry. 2022, 99, 1112–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissons, M. Development of Novel Pasta Products with Evidence Based Impacts on Health—A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Bharti, D.; Pradhan, B.K.; Sahu, D.; Dhal, S.; Kim, N.M.; Jarzebski, M.; Pal, K. Analysis of the Physical and Structure Characteristics of Reformulated Pizza Bread. Foods 2022, 11, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A.; Costantini, M.; Faccia, M.; Difonzo, G.; Caponio, F.; Summo, C. The Effectiveness of Extruded-Cooked Lentil Flour in Preparing a Gluten-Free Pizza with Improved Nutritional Features and a Good Sensory Quality. Foods 2022, 11, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikinmaa, M.; Mustonen, S.A.; Huitula, L.; Laaksonen, O.; Linderborg, K.M.; Nordlund, E.; Nesli Sozer, N. Wholegrain oat quality indicators for production of extruded snacks. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 174, 114457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chriqui, J.F.; Lina, W.; Leidera, J.; Shangc, C.; Pernad, F.M. The Harmonizing Effect of Smart Snacks on the Association between State Snack Laws and High School Students’ Fruit and Vegetable Consumption, United States—2005–2017. Prev Med. 2020, 139, 106093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, G.; Lambert, L.G.; Gupta, K.; Partacz, M. Smart snacks in universities: possibilities for university vending. Health Promot. Perspect. 2020, 10, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurzynska, A.; Ciesluk, P.; Barwinska, M.; Marczak, W.; Ordyniak, A.; Lenart, A.; Janowicz, M. Eating Habits and Sustainable Food Production in the Development of Innovative “Healthy” Snacks. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnwald, B.P.; Crum, A.J. Smart food policy for healthy food labeling: Leading with taste, not healthiness, to shift consumption and enjoyment of healthy foods. Prev. Med. 2019, 119, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Ashaolu, J.O. Perspectives on the trends, challenges and benefits of green, smart and organic (GSO) foods. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 22, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkes, C.; Smith, T.G.; Jewell, J.; Wardle, J.; Hammond, R.A.; Friel, S.; Thow, A.M.; Kain, J. Smart food policies for obesity prevention. Lancet 2015, 385, 2410–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, I.D.; van Liere, M.J.; de Brauw, A.; Dominguez-Salas, P.; Herforth, A.; Kennedy, G.; Lachat, C.; Omosa, E.B.; Talsma, E.F.; Vandevijvere, S.; et al. Reverse thinking: taking a healthy diet perspective towards food systems transformations. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 1497–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegwu, T.M.; Balogu, T.V.; Iroagba, N.L.; Okoyeuzu, C.F.; Obiora, C.U.; Balogu, D.O.; Agu, H.O. Food Security in Emerging Global Situations-Functional Foods and Food Biotechnology Approaches: A Review. J. Adv. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 10, 46–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.T.; Buttriss, J.L.; Bureau-Franz, I.; Wigger, P.K.; Drewnowski, A. Future of food: Innovating towards sustainable healthy diets. Nutr. Bull. 2021, 46, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, A.; P’enicaud, C.; Saint-Eve, A.; Soler, L.G.; Souchon, I. Does environmental impact vary widely within the same food category? A case study on industrial pizzas from the French retail market. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latunde-Dada, G.O.; Kajarabille, N.; Rose, S.; Arafsha, S.M.; Kose, T.; Aslam, M.F.; Hall, W.L.; Sharp, P.A. Content and Availability of Minerals in Plant-Based Burgers Compared with a Meat Burger. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.; Zhu, O.Y.; Dolnicar, S. Vegan burger, no thanks! Juicy American burger, yes please! The effect of restaurant meal names on affective appeal. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 113, 105042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H Herawati, H.; Kamsiati, E. Characteristics of vegetarian patties burgers made from tofu and tempeh. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 653, 012103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bánáti, D. Veggie burgers, vegan meats? The ruling of the European Parliament paved the way for meat substitutes with meat denominations. J. Food Investigation. 2020, 66, 3166–3174. [Google Scholar]

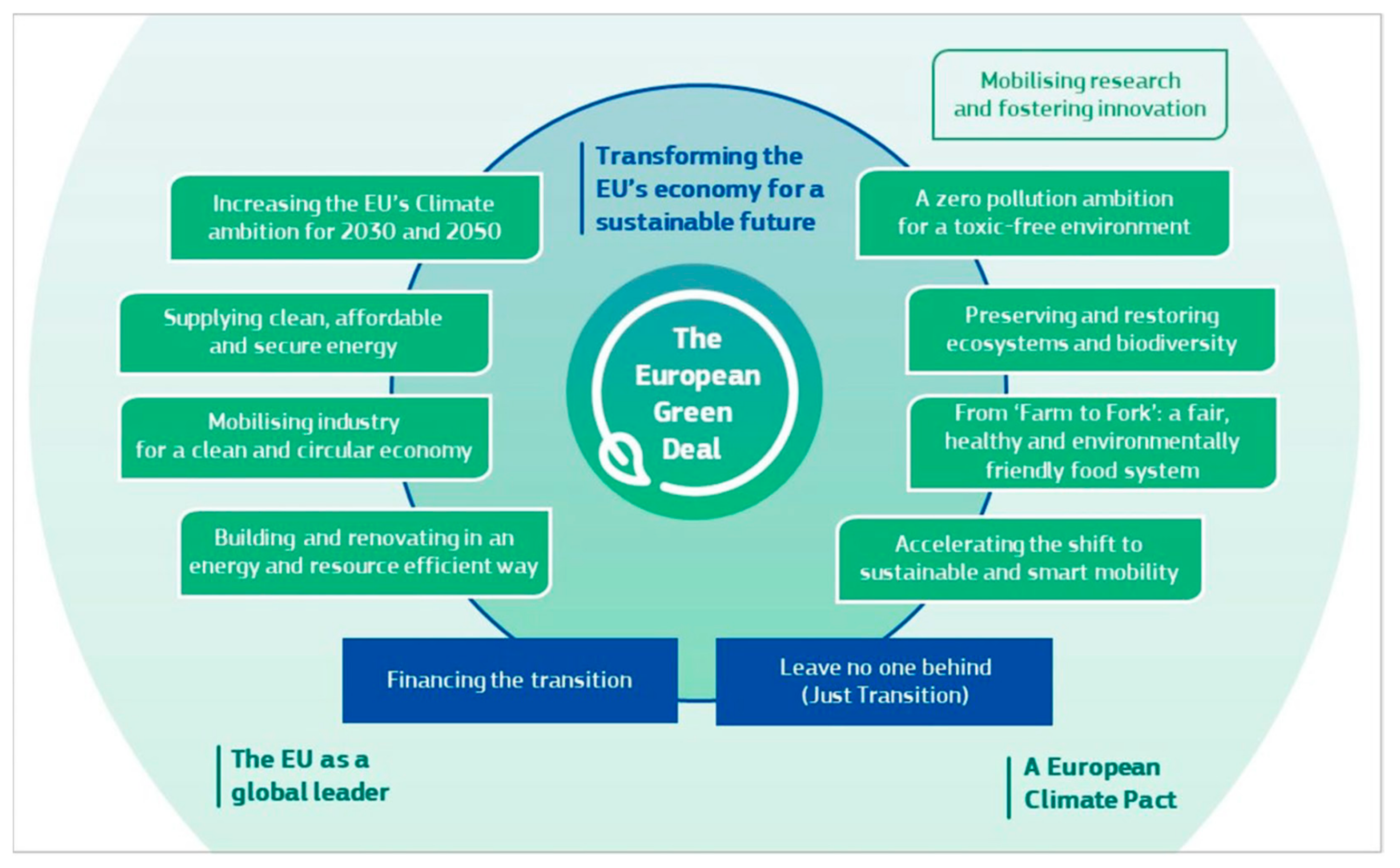

- Filipovic, S.; Lior, N.; Radovanovic, M. The green deal – just transition and sustainable development goals Nexus. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltsev, S.; Chen, Y.H.H.; Karplus, V.; Kishimoto, P.; Reilly, J.; Löschel, A.; von Graevenitz, K.; Koesler, S. Reducing CO2 from cars in the European Union. Transportation 2018, 45, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Faura, J. European Union policies and their role in combating climate change over the years. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2022, 15, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosamond, J.; Dupont, C. The European Council, the Council, and the European Green Deal. Politics Gov. 2021, 9, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delouyi, F.L.; Ranjbari, M.; Esfandabadi, Z.S. A Hybrid Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis to Explore Barriers to the Circular Economy Implementation in the Food Supply Chain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, A.; Antonelli, M.; Wambersie, L.; Bach-Faig, A.; Bartolini, F.; Caro, D.; Iha, K.; Lin, D.; Mancini, M.S.; Sonnino, R.; et al. EU-27 ecological footprint was primarily driven by food consumption and exceeded regional biocapacity from 2004 to 2014. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J. Healthy and Sustainable Diets and Food Systems: the Key to Achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2? Food Ethics 2019, 4, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.D.; Hartle, J.C.; Garrett, R.D.; Offringa, L.C.; Wasserman, A.S. Maximizing the intersection of human health and the health of the environment with regard to the amount and type of protein produced and consumed in the United States. Nutr. Reviews. 2019, 77, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Marrón, A.; Adams, K.; Sinno, L.; Cantu-Aldana, A.; Tamez, M.; Marrero, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Mattei, J. Environmental Impact of Animal-Based Food Production and the Feasibility of a Shift Toward Sustainable Plant-Based Diets in the United States. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 841106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangari, C.; Mwema, C.; Siambi, M.; Silim, S.; Ubwe, R.; Malesi, K.; Anitha, S.: Kane-Potaka, J. ‘Changing perception through participatory approach by in-volving adolescent school children in evaluating Smart Food dishes in school feeding program – Real time experience from Central Tanzania. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2020, 59, 472–485. [CrossRef]

- Anitha, S.; Htut, T.T.; Tsusaka, T.W.; Jalagam, A.; Kane-Potaka, J. Potential for smart food products in rural Myanmar: Use of millets and pigeonpea to fill the nutrition gap. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 100, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, M.; Ahanger, T.A. Intelligent decision-making in Smart Food Industry: Quality perspective. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2021, 72, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, H.; Ruperti, Y. Smart food: novel foods, food security, and the Smart Nation in Singapore. Food Cult. Soc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halgamuge, M.N.; Bojovschi, A.; Fisher, P.M.J.; Le, T.C.; Adeloju, S.; Murphy, S. Internet of Things and autonomous control for vertical cultivation walls towards smart food growing: A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challinor, A.J.; Arenas-Calles, L.N.; Whitfield, S. Measuring the Effectiveness of Climate-Smart Practices in the Context of Food Systems: Progress and Challenges. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 853630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.A.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Massawe, F. Building a resilient and sustainable food system in a changing world – A case for climate smart and nutrient dense crops. Glob. Food Security. 2021, 28, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamura, C.; Cecchi, G.; Bravo, M.; Brunelli, N.; Laudisio, A.; Di Caprio, P.; Botti, G.; Paolucci, M.; Khazrai, Y.M.; Vernieri, F. The Healthy Eating Plate Advice for Migraine Prevention: An Interventional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelmie, R.J. Impact of Dietary Meat and Animal Products on GHG Footprints: The UK and the US. Climate 2022, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, A.; Clark, H. How much do direct livestock emissions actually contribute to global warming? Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 1749–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynes, S.; Nicholas, K.A.; Zhao, J.; Donner, S.D. Measuring what works: quantifying greenhouse gas emission reductions of behavioral interventions to reduce driving, meat consumption, and household energy use. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 113002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecha, R.J.; Ganti, G.; Lamboll, R.D.; Nicholls, Z.; Hare, B.; Lewis, J.; Meinshausen, M.; Schaeffer, M.; Smith, C.J.; Gidden, M.J. Institutional decarbonization scenarios evaluated against the Paris Agreement 1.5 °C goal. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaço, F.M.A.; Teixeira, A.C.R.; Machado, P.G.; Borges, R.R.; Brito, T.L.F.; Mouette, D. Road Freight Transport Literature and the Achievements of the Sustainable Development Goals—A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, K.K.; Ting, H.H.; Lim, Y.S.; Ting, J.T.W.; Peter, M.; Ibrahim, K.; Show, P.L. Feasibility of UTS Smart Home to Support Sustainable Development Goals of United Nations (UN SDGs): Water and Energy Conservation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattiaux, M.A. Sustainability of dairy systems through the lenses of the sustainable development goals. Front. Anim. Sci. 4:1135381. [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.V. Meat supply chain in the perspective. of UN SDGS. Theory Pract. Meat Process. 2021, 6, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevalainen, E.; Niva, M.; Vainio, A. A transition towards plant-based diets on its way? Consumers’ substitutions of meat in their diets in Finland. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 104, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresán, U.; Errendal, S.; Craig, W.J. Influence of the Socio-Cultural Environment and External Factors in Following Plant-Based Diets. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Satherley, N.; Osborne, D.; Wilson, M.S.; Sibley, C.G. To meat, or not to meat: A longitudinal investigation of transitioning to and from plant-based diets. Appetite 2021, 166, 105584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Sanctorum, H. ‘Alternative proteins, evolving attitudes: Comparing consumer attitudes to plant-based and cultured meat in Belgium in two consecutive years’. Appetite 2021, 161, 105161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, S.; Furchheim, P.; Strässner, A.M. Plant-Based Meat Alternatives: Motivational Adoption Barriers and Solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrega, A.; Rizo, A.; Murciano, A.; Laguna, L.; Fiszman, S. Are mixed meat and vegetable protein products good alternatives for reducing meat consumption? A case study with burgers. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2020, 3, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukid, F.; Castellari, M. Veggie burgers in the EU market: a nutritional challenge? Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 2445–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.; Goeler-Slough, N.; Cox, A.; Nolden, A. Examination of the nutritional composition of alternative beef burgers available in the United States. Int. J. FOOD Sci. Nutr. 2022, 73, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd -Elhak, N.A. Preparation and Evaluation of Different Nutritive Vegetarian Burger for Females and Women. Egypt. J. Food. Sci. 2021, 49, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, F.; Knaapila, A.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. A multi-national comparison of meat eaters’ attitudes and expectations for burgers containing beef, pea or algae protein. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 91, 104195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, S.; Profeta, A.; Voigt, R.; Kircher, C.; Heinz, V. Meat substitution in burgers: nutritional scoring, sensorial testing, and Life Cycle Assessment. Future Foods 2021, 4, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Catala, J.; Toro-Funes, N.; Comas-Basté, O.; Hernández-Macias, S.; Sánchez-Pérez, S.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Castell-Garralda, V.; Carmen Vidal-Carou, M. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2807. [CrossRef]

- Hielkema, M.H.; Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J. Veg on the menu? Differences in menu design interventions to increase vegetarian food choice between meat-reducers and non-reducers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 102, 104675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.; Portmann, R.; Recio, I.; Dubois, S.; Egger, L. Comparison of in vitro digestibility and DIAAR between vegan and meat burgers before and after grilling. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnack, L.; Mork, S.; Valluri, S.; Weber, C.; Schmitz, K.; Stevenson, J.; Pettit, J. Nutrient Composition of a Selection of Plant-Based Ground Beef Alternative Products Available in the United States. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021, 121, 2401–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, W.D.; Pinto, F.R.; Barroso, S.; Gil, M.M. Development, Characterization, and Consumer Acceptance of an Innovative Vegan Burger with Seaweed. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaretnam, S.; Malik, N.H. Physical and Sensory Properties of Vegetarian Burger Patty. Enhanc. Knowl. Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, E.P.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Onwezen, M.C.; Taufik, D. “Do you consider animal welfare to be important?” activating cognitive dissonance via value activation can promote vegetarian choices. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 83, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingenbleek, P.T.M.; Zhao, Y. The Vegetarian Butcher: on its way to becoming the world’s biggest ‘meat’ producer? Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2019, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chung, S.J. Hedonic plasticity of vegan burger patty in implicit or explicit reference frame conditions. J Sci Food Agric 2023, 103, 2641–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousta, N.; Hellwig, C.; Wainaina, S.; Lukitawesa, L.; Agnihotri, S.; Rousta, K.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Filamentous Fungus Aspergillus oryzae for Food: From Submerged Cultivation to Fungal Burgers and Their Sensory Evaluation—A Pilot Study. Foods 2021, 10, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca, P.; Pierucci, A.P.; Boukid, F. Analysis of ingredient list and nutrient composition of plant-based burgers available in the global market. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, W.; Zheng, Y. Does the advertising of plant-based burgers attract meat consumers? The influence of new product advertising on consumer responses. Agribusiness. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.L.; Rothgerber, H.; Tomiyama, A.J. When meat-eaters expect vegan food to taste bad: Veganism as a symbolic threat. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2024, 27, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.C.; Chen, H.S. Exploring Consumers’ Purchase Intention of an Innovation of the Agri-Food Industry: A Case of Artificial Meat. Foods 2020, 9, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, H.L. The eco-friendly burger Could cultured meat improve the environmental sustainability of meat products? EMBO Rep. 2019, 20, e47395-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besson, T.; Bouxom, H.; Jaubert, T. Halo It’s Meat! the Effect of the Vegetarian Label on Calorie Perception and Food Choices. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2020, 59, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schillaci, E.; Gràcia, A.; Capellas, M.; Rigola, J. Numerical modeling and experimental validation of meat burgers and vegetarian patties cooking process with an innovative IR laser system. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e14097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slegers, P.M.; Helmes, R.J.K.; Draisma, M.; Broekema, R.; Vlottes, M.; van den Burg, S.W.K. Environmental impact and nutritional value of food products using the seaweed Saccharina latissimi. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustar, A.; Patino-Echeverri, D. A Review of Environmental Life Cycle Assessments of Diets: Plant-Based Solutions Are Truly Sustainable, even in the Form of Fast Foods. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, A.; P’enicaud, C.; Saint-Eve, A.; Soler, L.G.; Souchon, I. Does environmental impact vary widely within the same food category? A case study on industrial pizzas from the French retail market. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, A.; Cini, E. Challenges and Opportunities in Wheat Flour, Pasta, Bread, and Bakery Product Production Chains: A Systematic Review of Innovations and Improvement Strategies to Increase Sustainability, Productivity, and Product Quality. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia-Siapco, G.; Burkholder-Cooley, N.; Tabrizi, S.H.; Sabaté, J. Beyond Meat: A Comparison of the Dietary Intakes of Vegetarian and Non-vegetarian Adolescents. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, N.; Klatt, K.; Wei, D.; Williamson, E.; Ulgenalp, I.; Trinidade, O.; Kusaslan, E.; Yildirim, A.; Gowers, C.; Guard, R.; et al. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Products Marketed as Plant-Based Across the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada Using Online Nutrition Information. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2023, 7, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguerol, A.T.; Págan, M.J.; García-Segovia, P.; Varela, P. Green or clean? Perception of clean label plant-based products by omnivorous, vegan, vegetarian and flexitarian consumers. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindke, A.R.; Travis, A.; Smith, T.A.; Cotwright, C.J.; Morris, D.; Cox, G.O. Plate Waste Evaluation of Plant-Based Protein Entrees in National School Lunch Program. J Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvo, P.; Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Matacena, R. Eating at Work: The Role of the Lunch-Break and Canteens for Wellbeing at Work in Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 1043–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, A.; Oliva, N.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Lorini, C.; Cini, E. Assessment of the rheological properties and bread characteristics obtained by innovative protein sources (Cicer arietinum, Acheta domesticus, Tenebrio molitor): Novel food or potential improvers for wheat flour? LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 118, 108867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, V.; Venturi, M.; Coda, R.; Maina, N.H.; Granchi, L. Isolation and characterization of indigenous Weissella confusa for in situ bacterial exopolysaccharides (EPS) production in chickpea sourdough. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncolini, A.; Milanovi’c, V.; Aquilanti, L.; Cardinali, F.; Garofalo, C.; Sabbatini, R.; Clementi, F.; Belleggia, L.; Pasquini, M.; Mozzon, M.; et al. Lesser mealworm (Alphitobius diaperinus) powder as a novel baking ingredient for manufacturing high-protein, mineral-dense snacks. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 109031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Segovia, P.; Igual, M.; Martínez-Monzó, J. Physicochemical Properties and Consumer Acceptance of Bread Enriched with Alternative Proteins. Foods 2020, 9, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, A.; Cini, E.; Lorini, C.; Oliva, N.; Bonaccorsi, G. Insects as food: A review on risks assessments of Tenebrionidae and Gryllidae in relation to a first machines and plants development. Food Control. 2020, 108, 106877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Segovia, P.; Igual, M.; Noguerol, A.T.; Martínez-Monzó, J. Use of insects and pea powder as alternative protein and mineral sources in extruded snacks. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Huis, A. Prospects of insects as food and feed. Org. Agr. 2021, 11, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Estrada, B.A.; Reyes, A.; Rosell, C.M.; Rodrigo, D.; Ibarra-Herrera, C.C. Benefits and Challenges in the Incorporation of Insects in Food Products. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 687712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhujaili, A.; Nocella, G.; Macready, A. Insects as Food: Consumers’ Acceptance and Marketing. Foods 2023, 12, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union (2015). Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European parliament and of the council of 25 November 2015 on novel foods, amending regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European parliament and of the Council and repealing regulation (EC) No 258/97 of the European parliament and of the Council and commission regulation (EC) No 1852/2001. Official Journal of the European Union L, 327, 1–22.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).