Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

23 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Ethical Approval

2.3. TSH Groups

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

| N=363 | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.9 ± 9.3 |

| Gender, female | 145 (39.9) |

| Insulin therapy, yes | 255 (70.2) |

| HT, yes | 342 (94.2) |

| Sigara ≥ 20 Paket/yıl | 187 (51.5) |

| Mortality Beta (B) | Mortality p-value (Sig.) | Mortality + Microvascular Complications Beta (B) | Mortality + Microvascular Complications p-value (Sig.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSH percentile group (overall effect) | - | 0,015 | - | 0,026 |

| TSH group 2 | -1,053 | 0,004 | -1,027 | 0,007 |

| TSH group 3 | -0,319 | 0,323 | 0,251 | 0,453 |

| Gender, female | 0,358 | 0,294 | 0,454 | 0,198 |

| Age, years | 0,054 | 0,001 | 0,046 | 0,005 |

| Smoking ≥20 pack-years, yes | -0,421 | 0,218 | -0,362 | 0,306 |

| Insulin therapy, yes | -0,201 | 0,517 | 0,232 | 0,477 |

| Constant | -4,467 | 0,000 | -4,414 | 0,000 |

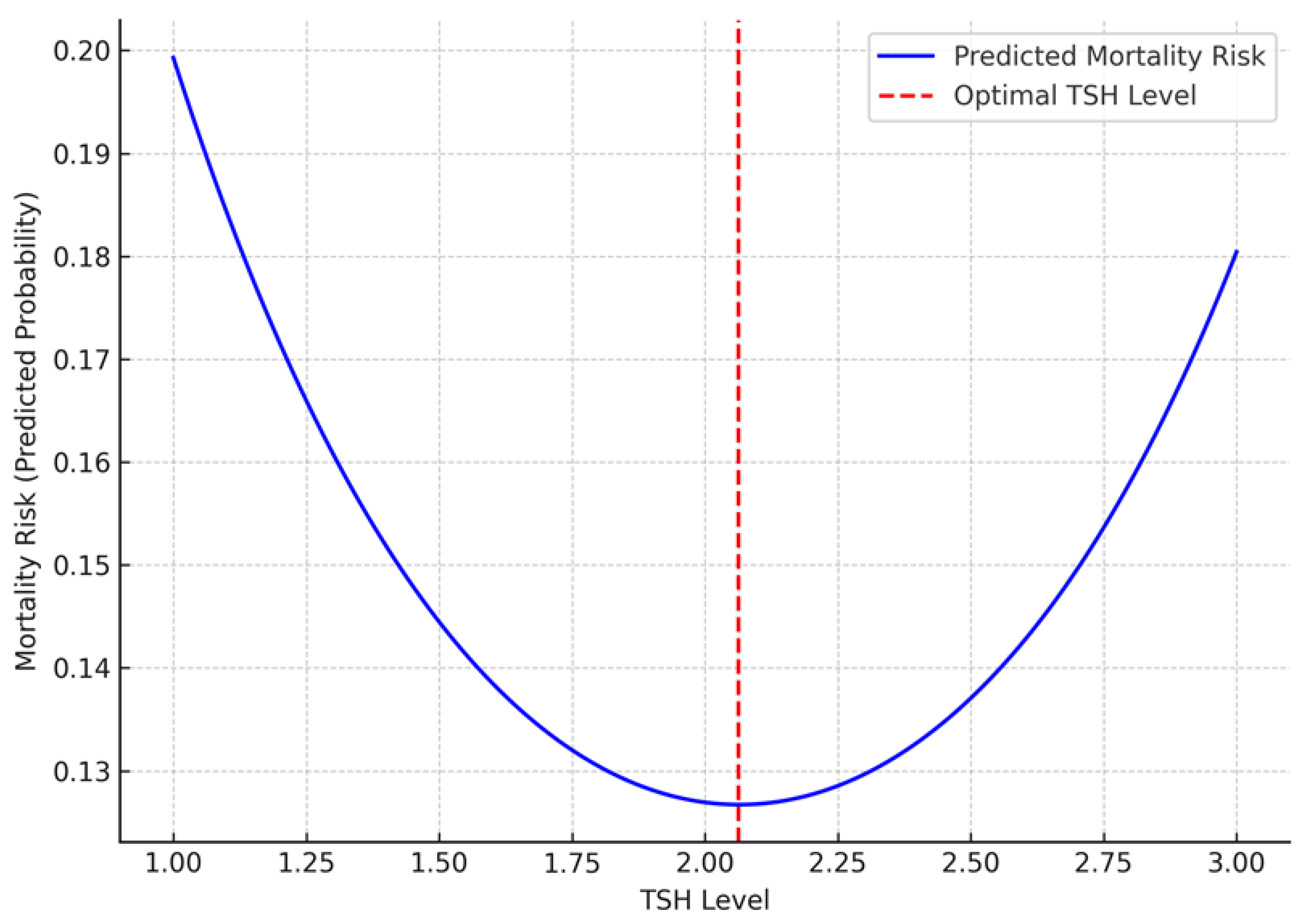

| Variable | Beta (B) | p-Value (Sig.) | |

| TSH² | 0.512 | 0.002 | |

| TSH | -2.094 | 0.002 | |

| Age, years | 0.054 | 0.001 | |

| Insulin therapy, yes | 0.189 | 0.541 | |

| Gender, female | 0.269 | 0.428 | |

| Smoking ≥20 pack-years, yes | -0.321 | 0.345 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Uppal, V.; Vij, C.; Bedi, G.K.; Vij, A.; Banerjee, B.D. Thyroid Disorders in Patients of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry 2013, 28, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khin, P.P.; Lee, J.H.; Jun, H.-S. Pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. European Journal of Inflammation 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, F.; Dai, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X. Association between thyroid dysfunction and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. BMC Medicine 2021, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadgu, R.; Worede, A.; Ambachew, S. Prevalence of thyroid dysfunction and associated factors among adult type 2 diabetes mellitus patients, 2000–2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews 2024, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, X.G.; Stevens, S.K.; Jekle, A.; Lin, T.-I.; Gupta, K.; Misner, D.; Chanda, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Williams, C.; Stoycheva, A. Regulation of gene transcription by thyroid hormone receptor β agonists in clinical development for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). PLoS One 2020, 15, e0240338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, H.; Mullapudi, S.T.; Zhang, Y.; Hesselson, D.; Stainier, D.Y.R. Thyroid Hormone Coordinates Pancreatic Islet Maturation During the Zebrafish Larval-to-Juvenile Transition to Maintain Glucose Homeostasis. Diabetes 2017, 66, 2623–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, G.; Kumari, N.; Bano, F.; Tyagi, R.K. Thyroid hormone receptor beta: Relevance in human health and diseases. Endocrine and Metabolic Science 2023, 13, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Cao, Y.; Feng, C.; Zheng, Y.; Dhana, K.; Zhu, S.; Shang, C.; Yuan, C.; Zong, G. Association of a Healthy Lifestyle With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality Among Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Study in UK Biobank. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Valencia, P.E.; Díaz-García, J.D.; Leyva-Leyva, M.; Sánchez-Aguillón, F.; González-Arenas, N.R.; Mendoza-García, J.G.; Tenorio-Aguirre, E.K.; de León-Bautista, M.P.; Ibarra-Arce, A.; Maravilla, P. Frequency of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α, Interleukin-6, and Interleukin-10 Gene Polymorphisms in Mexican Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Kidney Disease. Pathophysiology 2025, 32, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, N.; Üstunkaya, T.; Feener, E.P. Thrombosis and Hemorrhage in Diabetic Retinopathy: A Perspective from an Inflammatory Standpoint. Semin Thromb Hemost 2015, 41, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Forrest, D. Biphasic expression of thyroid hormone receptor TRβ1 in mammalian retina and anterior ocular tissues. Frontiers in endocrinology 2023, 14, 1174600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubu, T.T.Ç. Tiroid Hastalıkları Tanı ve Tedavi Kılavuzu-2023. 7. Baskı, Türkiye Endokrinoloji ve Metabolizma Dernegi (TEMD) Yayınları, Bayt Matbaacılık, Ankara 2023.

- Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Garcia-Arumi, J.; Bandello, F.; Berg, K.; Chakravarthy, U.; Gerendas, B.S.; Jonas, J.; Larsen, M.; Tadayoni, R.; Loewenstein, A. Guidelines for the management of diabetic macular edema by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Ophthalmologica 2017, 237, 185–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care, D. Care in diabetesd2019. Diabetes care 2019, 42, S13–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O. 2023 focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European heart journal 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isong, I.K.; Udiong, C.E.; Akpan, U.O. Thyroid hormones and glycaemic indices in euthyroid, hyperthyroid, hypothyroid, all type 2 diabetics and non-diabetic subjects. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2022, 46, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Aggarwal, S.; Khandelwal, D. Thyroid dysfunction and type 2 diabetes mellitus: screening strategies and implications for management. Diabetes Therapy 2019, 10, 2035–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiga-Carvalho, T.M.; Sidhaye, A.R.; Wondisford, F.E. Thyroid hormone receptors and resistance to thyroid hormone disorders. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2014, 10, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, P.d.F.d.S.; Dos Santos, P.B.; Pazos-Moura, C.C. The role of thyroid hormone in metabolism and metabolic syndrome. Therapeutic advances in endocrinology and metabolism 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, E.; Ponce, C.; Brodschi, D.; Nepote, A.; Barreto, A.; Schnitman, M.; Fossati, P.; Salgado, P.; Cejas, C.; Faingold, C. Association between worse metabolic control and increased thyroid volume and nodular disease in elderly adults with metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome and related disorders 2015, 13, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Shin, Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, S. Inherited disorders of thyroid hormone metabolism defect caused by the dysregulation of selenoprotein expression. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 12, 803024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penna, G.C.; Salas-Lucia, F.; Ribeiro, M.O.; Bianco, A.C. Gene polymorphisms and thyroid hormone signaling: implication for the treatment of hypothyroidism. Endocrine 2024, 84, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groeneweg, S.; van Geest, F.S.; Peeters, R.P.; Heuer, H.; Visser, W.E. Thyroid hormone transporters. Endocrine reviews 2020, 41, 146–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luongo, C.; Dentice, M.; Salvatore, D. Deiodinases and their intricate role in thyroid hormone homeostasis. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2019, 15, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, R.; Shetty, S.; Pappachan, J.M. Efficacy and safety of Resmetirom, a selective thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist, in the treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 19790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, B.R.; Sola-García, A.; Cáliz-Molina, M.Á.; Lorenzo, P.I.; Cobo-Vuilleumier, N.; Capilla-González, V.; Martin-Montalvo, A. Thyroid hormones in diabetes, cancer, and aging. Aging cell 2020, 19, e13260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, A.; Murolo, M.; Cicatiello, A.G.; Sagliocchi, S.; Di Cicco, E.; Raia, M.; Stornaiuolo, M.; Dentice, M.; Miro, C. Thyroid Hormone Receptor Isoforms Alpha and Beta Play Convergent Roles in Muscle Physiology and Metabolic Regulation. Metabolites 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minakhina, S.; Bansal, S.; Zhang, A.; Brotherton, M.; Janodia, R.; De Oliveira, V.; Tadepalli, S.; Wondisford, F.E. A direct comparison of thyroid hormone receptor protein levels in mice provides unexpected insights into thyroid hormone action. Thyroid 2020, 30, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, G.; Casini, G.; Posarelli, C.; Amato, R.; Lulli, M.; Balzan, S.; Forini, F. Thyroid Hormone Signaling in Retinal Development and Function: Implications for Diabetic Retinopathy and Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ding, W.; Wang, H.; Shi, Y. Association between sensitivity to thyroid hormone indices and diabetic retinopathy in euthyroid patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity 2023, 535-545. [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Li, Z.; Tian, F.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhai, J.; Shi, M.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, C. Association between normal thyroid hormones and diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. BioMed Research International 2020, 2020, 8161797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akın, S.; Bölük, C. Prevalence of comorbidities in patients with type–2 diabetes mellitus. Primary care diabetes 2020, 14, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, Z.S.; Albassam, A.A.; Alhejji, N.S.; Alotaibi, B.S.; Al-Oqayli, L.A.; Ahmed, N.J. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of uncontrolled hypertension among patients with diabetes: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. Primary care diabetes 2020, 14, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śliwińska-Mossoń, M.; Milnerowicz, H. The impact of smoking on the development of diabetes and its complications. Diabetes and Vascular Disease Research 2017, 14, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, C.Y.; Gan, W.L.; Lai, S.J.; Tam, R.S.-M.; Tan, J.F.; Dietl, S.; Chuah, L.H.; Voelcker, N.; Bakhtiar, A. Critical updates on oral insulin drug delivery systems for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caturano, A.; Rocco, M.; Tagliaferri, G.; Piacevole, A.; Nilo, D.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Iadicicco, I.; Donnarumma, M.; Galiero, R.; Acierno, C. Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Complications in Type 2 Diabetes: From Pathophysiology to Lifestyle Modifications. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecilia, O.M.; José Alberto, C.G.; José, N.P.; Ernesto Germán, C.M.; Ana Karen, L.C.; Luis Miguel, R.P.; Ricardo Raúl, R.R.; Adolfo Daniel, R.C. Oxidative Stress as the Main Target in Diabetic Retinopathy Pathophysiology. J Diabetes Res 2019, 2019, 8562408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, X.; Zhong, H.; Fang, J.; Li, X.; Shi, R.; Yu, Q. Research progress on the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. BMC ophthalmology 2023, 23, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Zhang, M.; Yi, X. Systemic inflammatory mediator levels in non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy patients with diabetic macular edema. Current Eye Research 2024, 49, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, M.H.; Elbayoumi, K.S.; Eladl, M.A.; Mohamed, A.A.; Hegazy, A.; El-Sherbeeny, N.A.; Attia, M.A.; Hisham, F.A.; Saleh, M.A.; Elaskary, A. Memantine mitigates ROS/TXNIP/NLRP3 signaling and protects against mouse diabetic retinopathy: Histopathologic, ultrastructural and bioinformatic studies. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 163, 114772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.; Schweizer, U. Thyroid Hormone Transport and Transporters. Vitam Horm 2018, 106, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Lu, M.; Xie, R.R.; Song, L.N.; Yang, W.L.; Xin, Z.; Yang, G.R.; Yang, J.K. A high TSH level is associated with diabetic macular edema: a cross-sectional study of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Connect 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, Z.; Asadzadeh, R. Subclinical Hypothyroidism Is a Risk Factor for Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2021, 35, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirabadizadeh, A., Mehran, L., Amouzegar, A., Asgari, S., Khalili, D., & Azizi, F. Association between changes in thyroid hormones and incident type 2 diabetes using joint models of longitudinal and time-to-event data: more than a decade follow up in the Tehran thyroid study. Frontiers in endocrinology 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Lao, G.; Chen, C.; Luo, L.; Gu, J.; Ran, J. TSH levels within the normal range and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality among individuals with diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022, 21, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wan, H.; Lu, Y. Thyroid Parameters and Kidney Disorder in Type 2 Diabetes: Results from the METAL Study. J Diabetes Res 2020, 2020, 4798947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, A.; Di Segni, C.; Raimondo, S.; Olivieri, G.; Silvestrini, A.; Meucci, E.; Currò, D. Thyroid Hormones, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2016, 2016, 6757154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Hua, R.; Guo, H.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, T. Effect of thyroid stimulating hormone on the prognosis of coronary heart disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2025, 16, 1433106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Tang, W.; Liu, W.; Wu, X.; Pan, C. Association of Thyroid Hormone Levels with Microvascular Complications in Euthyroid Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2022, 15, 2467–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

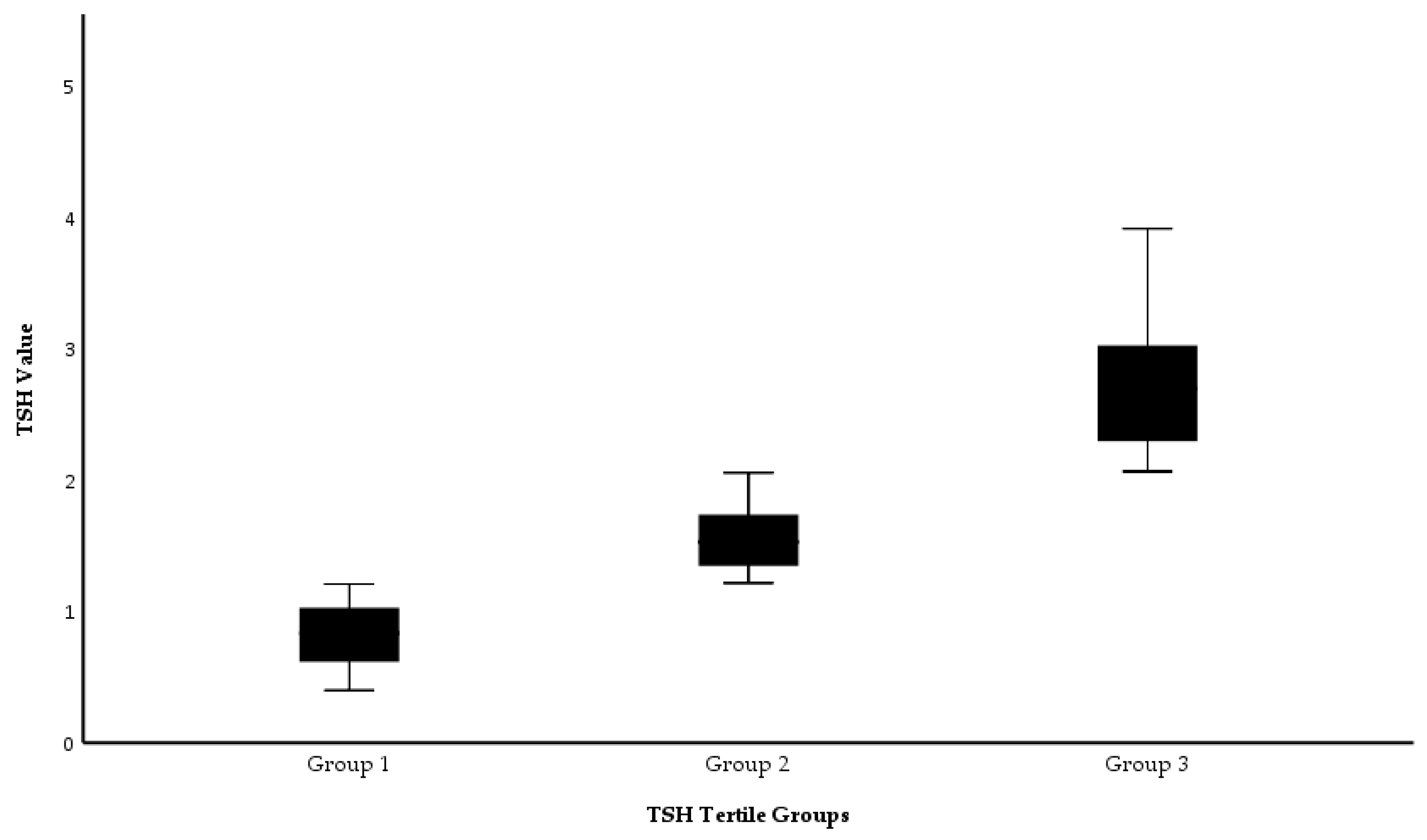

| Group 1 (n=120) TSH: 0.35 - 1.24 mIU/L |

Group 2 (n=122) TSH: 1.24 - 1.94 mIU/L |

Group 3 (n=121) TSH: 1.94 - 4.5 mIU/L |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.1 ± 9.5 | 64.2 ± 8.6 | 61.7 ± 9.7 | 0.119a |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL | 169 (68 - 478) | 158.5 (48 - 386) | 175 (50 - 453) | 0.570b |

| Urea, mg/dL | 45 (12 - 159) | 48 (12 - 253) | 41 (16 - 278) | 0.234b |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1 (0.4 - 7.8) | 1 (0.5 - 6.8) | 1 (0.5 - 55) | 0.926b |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m² | 67.6 (4.9 - 126.6) | 69.5 (5.1 - 169.2) | 67.9 (3.1 - 151.6) | 0.704b |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.4 (0.1 - 67.5) | 0.5 (0.1 - 72.8) | 0.5 (0.2 - 13.4) | 0.265b |

| ALT, IU/L | 17 (4 - 124) | 15 (4 - 252) | 17 (3 - 91) | 0.120b |

| AST, IU/L | 18 (8 - 274) | 18 (9 - 124) | 19 (7 - 108) | 0.442b |

| Albumin, g/L | 40 (4.3 - 49) | 41 (2.8 - 48) | 40 (4 - 48) | 0.880b |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 5.7 (1.5 - 10.8) | 5.5 (0.6 - 35) | 5.4 (2.4 - 12.8) | 0.784b |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.4 (0.1 - 2.4) | 0.4 (0.1 - 9) | 0.5 (0.1 - 4) | 0.938b |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 177 (69 - 353) | 184.5 (86 - 361) | 173 (82 - 356) | 0.150b |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 125 (35 - 645) | 132 (38 - 619) | 138 (39 - 902) | 0.537b |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 110 (22 - 229) | 119.5 (39 - 247) | 110 (30 - 291) | 0.065b |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 42 (19 - 86) | 42 (24 - 94) | 39 (16 - 85) | 0.237b |

| Free T4, ng/dL | 1.1 (0.5 - 3.9) | 1.1 (0.6 – 2.16) | 1.0 (0.5 – 2.64) | 0.023b |

| T3, ng/mL | 2.9 (0.5 - 4) | 2.9 (1 - 4.1) | 2.9 (0.9 - 5.7) | 0.911b |

| WBC, 10³/µL | 8.1 (3.5 - 19.8) | 7.5 (3.9 - 16.6) | 8.3 (4 - 20.1) | 0.119b |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.3 (6.7 - 16.8) | 12.4 (1 - 16.4) | 12.3 (7.5 - 16.7) | 0.973b |

| HbA₁c, % | 8.3 (5.4 - 14.2) | 8.2 (5.3 - 15.1) | 8.6 (5.5 - 15.2) | 0.260b |

| Platelets, 10³/µL | 236.5 (68 - 586) | 232.5 (85 - 459) | 231 (22 - 491) | 0.546b |

| Lymphocytes, 10³/µL | 1.8 (0.5 - 5.1) | 1.8 (0.5 - 4.2) | 2.1 (0.6 - 5.9) | 0.094b |

| Neutrophils, 10³/µL | 4.9 (1.1 - 16.7) | 4.6 (2 - 12.7) | 5 (0 - 16.5) | 0.373b |

| Monocytes, 10³/µL | 0.6 (0.2 - 1.6) | 0.6 (0.3 - 1) | 0.6 (0 - 1.5) | 0.120b |

| Gender Female, yes n (%) | 41 (34.2) | 52 (42.6) | 52 (43.0) | 0.287c |

| Insulin therapy, n (%), yes | 84 (70.0) | 86 (70.5) | 85 (70.2) | 0.997c |

| Insulin therapy, n (%), yes | 112 (93.3) | 118 (96.7) | 112 (92.6) | 0.336c |

| Smoking ≥20 pack-years, n (%), yes | 63 (52.5) | 63 (51.6) | 61 (50.4) | 0.948c |

| Group 1 (n=120) TSH: 0.35 - 1.24 mIU/L |

Group 2 (n=122) TSH: 1.24 - 1.94 mIU/L |

Group 3 (n=121) TSH: 1.94 - 4.5 mIU/L |

pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death at year 1, yes | 30 (25.0) | 14 (11.5) | 23 (19.0) | 0.025 |

| Death at year 3, yes | 7 (7.9) | 6 (5.6) | 11 (11.3) | 0.317 |

| Microvascular complication, year 1, yes | 92 (76.7) | 88 (72.1) | 88 (72.7) | 0.684 |

| Microvascular complication, year 3, yes | 69 (57.5) | 83 (68) | 77 (63.6) | 0.234 |

| Macrovascular complication, year 1, yes | 55 (45.8) | 63 (51.6) | 56 (46.3) | 0.602 |

| Macrovascular complication, year 3, yes | 37 (30.8) | 43 (35.2) | 41 (33.9) | 0.758 |

| Micro + Macro complications, year 1, yes | 50 (41.7) | 52 (42.6) | 46 (38.0) | 0.743 |

| Micro + Macro complications, year 3, yes | 33 (27.5) | 36 (29.5) | 38 (31.4) | 0.802 |

| Death + Microvascular complication, year 1, yes | 26 (21.7) | 12 (9.8) | 21 (17.4) | 0.041 |

| Death + Microvascular complication, year 3, yes | 7 (5.8) | 6 (4.9) | 9 (7.4) | 0.707 |

| Death + Macrovascular complication, year 1, yes | 21 (17.5) | 10 (8.2) | 15 (12.4) | 0.093 |

| Death + Macrovascular complication, year 3, yes | 5 (4.2) | 5 (4.1) | 10 (8.3) | 0.266 |

| Death + Micro + Macro complications, year 1, yes | 19 (15.8) | 8 (6.6) | 13 (10.7) | 0.070 |

| Death + Micro + Macro complications, year 3, yes | 5 (4.2) | 5 (4.1) | 9 (7.4) | 0.411 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).