1. Introduction

Transmembrane proteins are essential components of a cell. They span the entire width of the cell plasma membrane, enabling essential cellular functions such as signal transduction across the membrane, or the transport of ions and molecules, sometimes acting as dynamic gatekeepers. G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the most diverse group of transmembrane receptors in eukaryotes [

1,

2]. GPCRs play a critical role in signalling pathways that regulate a wide range of cellular processes, including hormone and neurotransmitter signalling [

3,

4,

5].

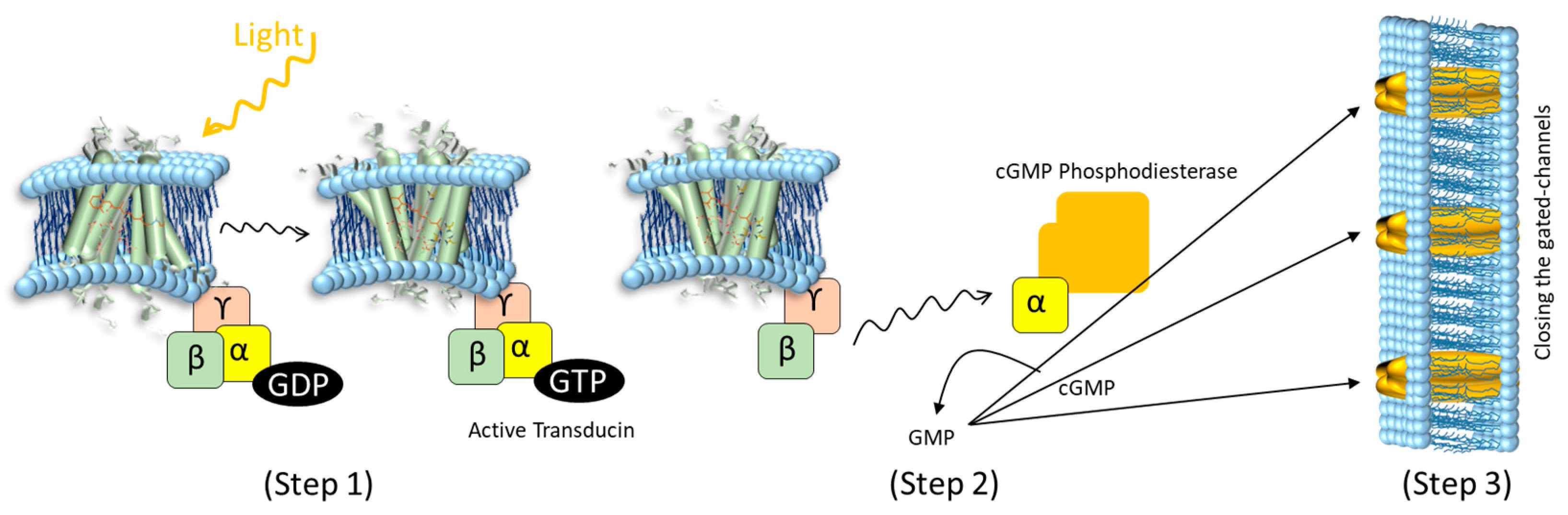

Rhodopsin [

6] is a GPCR present in the rod cells of the retina. The corresponding GPCR signalling pathway is part of visual information processing. Rhodopsin is activated by absorbing a photon, causing a structural change that initiates a signalling process on the cytoplasmic side. There, the G-protein transducin binds to activated rhodopsin, leading to an exchange of GDP for GTP in the transducin subunits (alpha, beta, and gamma). The alpha subunit then separates to activate phosphodiesterase (PDE), which breaks down cyclic GMP (cGMP) into GMP. This reduction in cGMP causes cGMP-dependent ion channels to close, increasing the cell membrane potential to eventually generate a neural signal (

Figure 1) [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

In our study, we developed a microfluidic system to produce a model cell membrane where we integrated Rhodopsin to demonstrate the GPCR signalling pathway in vitro under light exposure [

13,

14]. The experiments of this study were designed to observe how light-induced activation of GPCRs influences the level of cGMP and, consequently, the behaviour of gated ion channels in the lipid bilayer [

15,

16,

17,

18]. We observed changes in electrical activity across the model membrane that align well with the activation and deactivation of cGMP-gated ion channels. To our knowledge, an electrical current modulated by the photoactivation of rhodopsin has not been observed in vitro. We believe that our microfluidic, functional realisation of the entire GPCR cascade is an important first milestone for new, extended, and detailed in vitro studies of GPCR signalling.

2. Results and Discussion

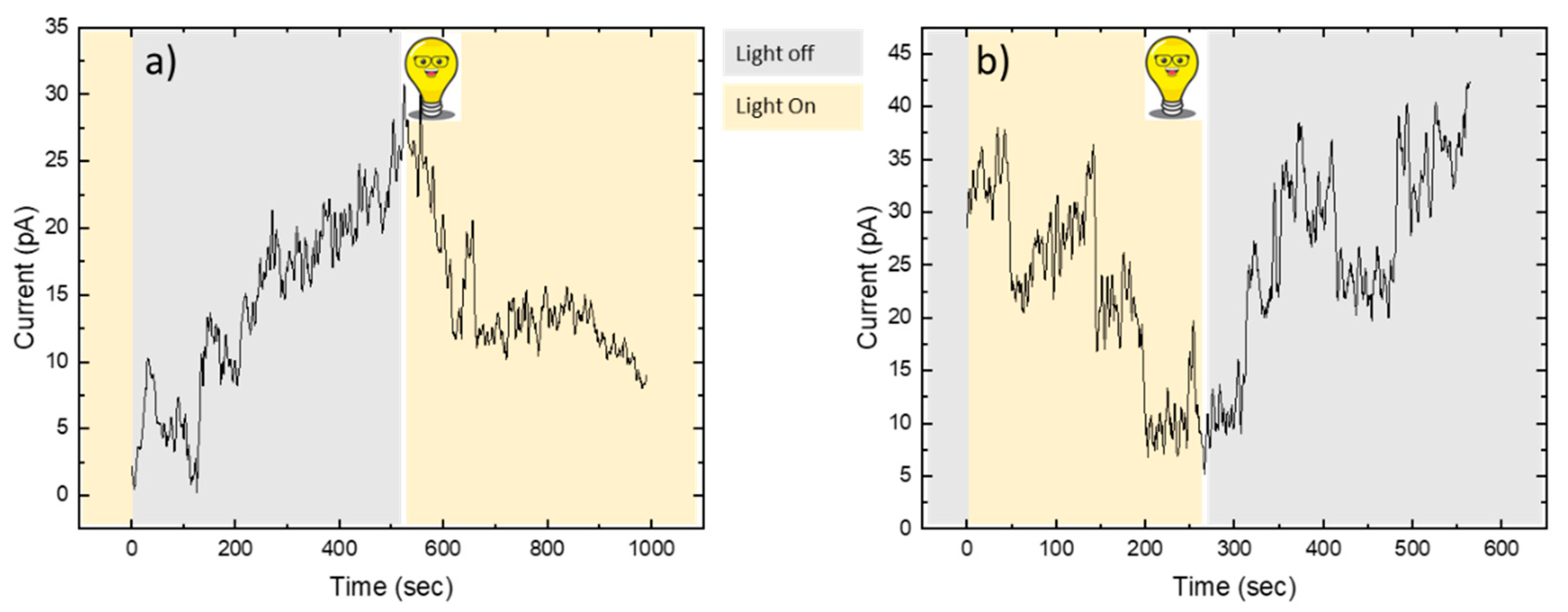

In a first type of experiment, the lipid bilayer was formed in a microfluidic device (see Materials and Methods) using a solution containing Porcine Outer Segment (POS) extract on both sides of the microfluidic channel under UV light. The intensity of the ion current across the bilayer was recorded simultaneously. As long as the light remained on, the current was fluctuating around zero pA. When the light was switched off, we observed an increase in the electrical current across the membrane over time (

Figure 2a). We interpret these changes as resulting from ions passing through cGMP-gated channels. After switching the light back on, the current decreased again. This can be easily explained by a conformational change in rhodopsin, which activates the G-protein transducin, leading to the closure of the gated channels via the canonical signalling pathway.

In a second type of experiment, the lipid bilayer with the POS extract solution was established in the dark. We observed a constant ion current that decreased as soon as the light was switched on. We attribute this to the closure of the gated channels resulting from cGMP degradation. After approximately 270 seconds, the light was turned off again, leading to an increase in current (

Figure 2b). We propose that GMP diffused from the POS extract solution towards the membrane, thereby causing the channels to reopen.

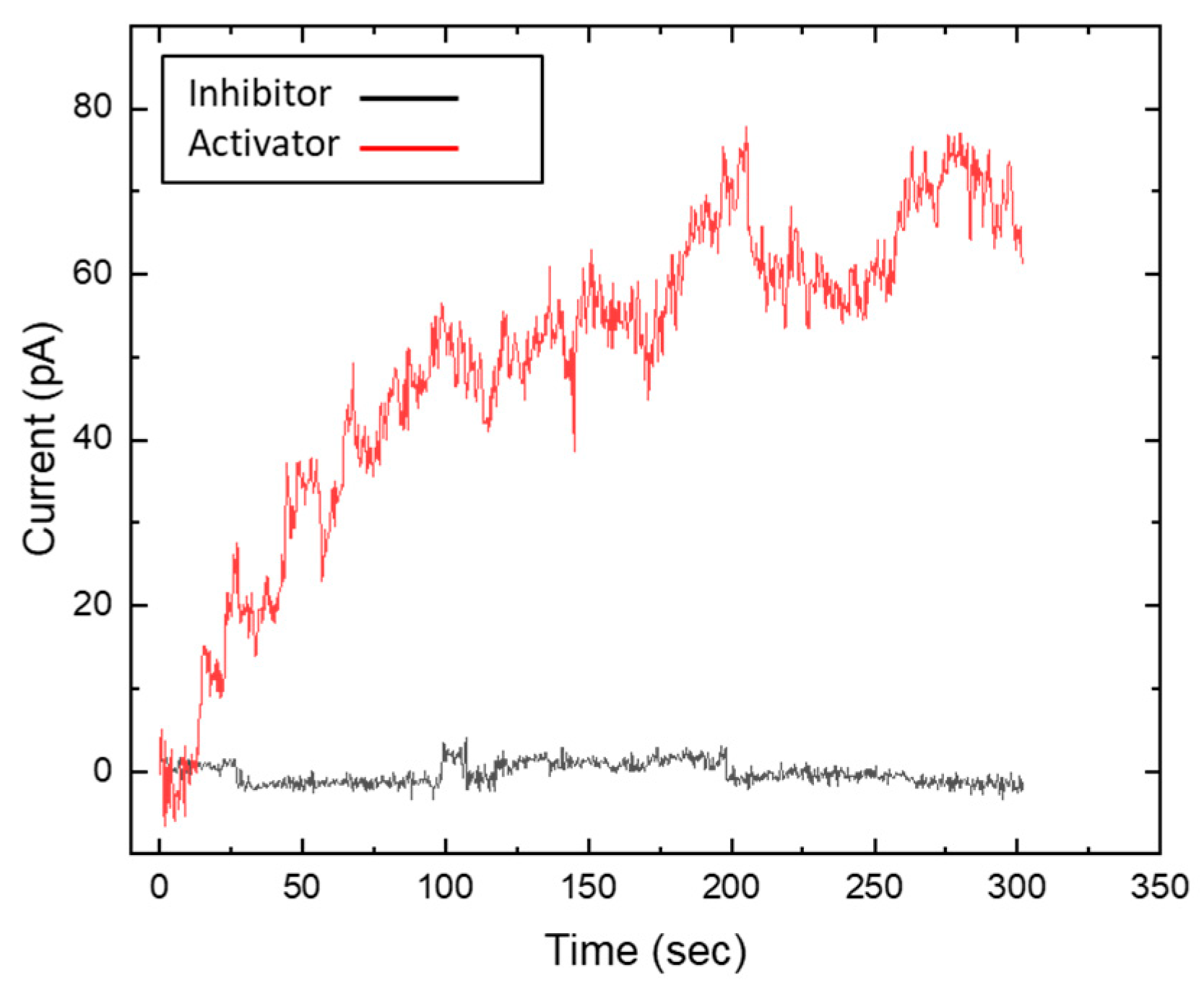

To confirm that the observation of the results in Fig. 2 is indeed due to the activation and deactivation of cGMP, we introduced cGMP analogues (inhibitors and activators) by adding them to the POS extract solution and conducted the same experiments as described above.

Figure 3 illustrates the impact of these analogues. The black line in the graph represents the inhibitory cGMP analogue, Rp-8-Br-cGMPS, which prevents cGMP-dependent channel activation, resulting in an electric current across the membrane that fluctuates around zero. Conversely, the red line in the graph represents the activating cGMP analogue, 8-pCPT-cGMP, which allows for continuous ion passage. These observations were independent of illumination, confirming that channel activity was modulated solely by the presence of these analogues. These findings highlight the crucial role of cGMP in regulating ion channel activity and validate the effectiveness of Rp-8-Br-cGMPS and 8-pCPT-cGMP in modulating GPCR-mediated signalling.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Lipid Preparation

DOPC (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) and DPhPC (1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. To prepare the lipid/oil solution, 5 mg of the lipids (DOPC/DPhPC at a 1:1.75 molar ratio) were dissolved in 1 mL of pure squalene oil (Sigma-Aldrich). The mixture was stirred at 45 °C for 3 hours.

3.2. Porcine Outer Segment (POS) Purification

Porcine outer segment (POS) extracts were prepared from freshly nucleated porcine eyes following a previously described method with minor modifications (Ref. [

19]). All steps were performed under dim red light to minimize photobleaching. Approximately 80 freshly obtained porcine eyes were immediately stored in a dark, cool environment until dissection. After removing the anterior segment and lens, the eyecup was inverted to expose the retina. The retina was gently detached, cut at the optic nerve head, and collected in homogenisation buffer which consists of 20% sucrose, 20 mM Tris-acetate pH 7.2, 2 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM glucose, 5 mM taurine on ice. The retinal tissue was manually shaken for 2 minutes to release POS from the surrounding layers, followed by filtration through double-layered gauze to remove larger tissue fragments. The filtrate was then layered onto a continuous 25-60% sucrose gradient and centrifuged at 106,000 × g for 50 minutes at 4 °C. POS were recovered as a distinct orange band in the upper third of the gradient, collected, and washed through sequential centrifugation steps in buffers of decreasing sucrose concentration. The final POS suspension was resuspended in DMEM, and the concentration was determined using a hemocytometer. Aliquots were stored at -80 °C and were never subjected to repeated freeze-thaw cycles to preserve structural integrity. For further details, including buffer compositions and optional labelling steps, refer to Ref. [

19].

3.3. Cyclic GMP Analogues

For the analysis of the effect of cGMP activation level on the photoactivation, two cGMP analogues were purchased from BioLog life science institute: Rp-8-Br-cGMPS as an inhibitor analogue and 8-pCPT-cGMP as an activator analogue.

3.4. Experimental Setup for Lipid Bilayer Formation

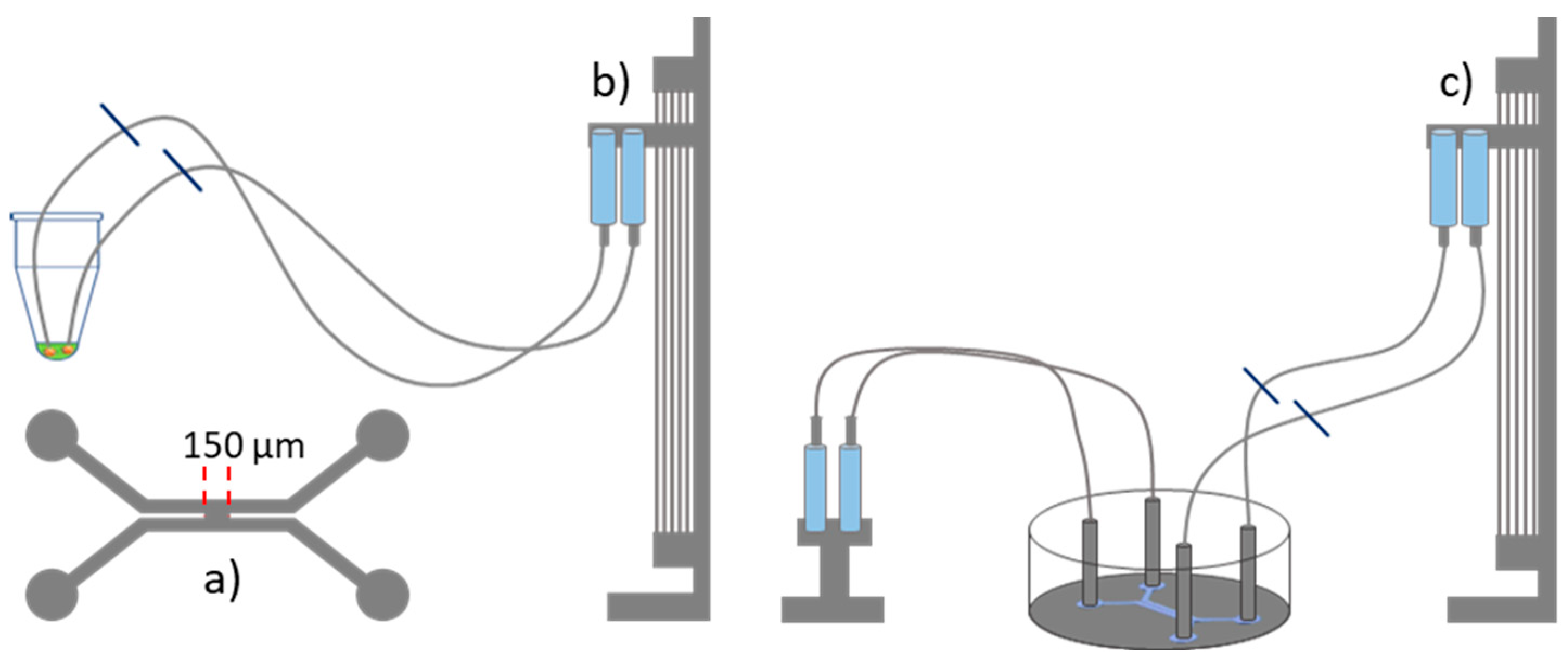

The microfluidic device was manufactured in Sylgard 184 using standard soft lithography protocols. The detailed protocol for fabricating the microfluidic device is given elsewhere [

13]. The microfluidic geometry consisted of two adjacent channels with a rectangular cross-section, 500 µm wide and 100 µm high (

Figure 4a). The fluids were controlled by hydrostatic pressure [

13,

14]. A lipid bilayer was formed at the junction between the two channels, with a width of 150 µm. To achieve this, the microfluidic device was first filled with squalene oil containing 5 mg/mL of the lipid mixture. Then, 50 µL of the extract solution was drawn into both tubes, which were subsequently connected to the microfluidic device (

Figure 4b,c). Care was taken to ensure that no air bubbles were introduced into the microfluidic device. Using pressure control, the POS extract solution was gently introduced into both microfluidic channels. The channels met at the intersection so that a bilayer formed at that location. Note that the formation and the stabilisation of a bilayer containing the extract solution is quite delicate and the success rate is only about 20 %. However, once a stable bilayer was formed, qualitatively identical results could be achieved throughout all of the experimental configurations.

3.5. Microscope Setup and Electrical Measurement

The experiments were monitored using inverted optical microscopy (Axio Observer Z1; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). For photoactivation of Rhodopsin, standard transmitted light illumination was used with the intensity set to about 80%. Ag/AgCl electrodes were inserted into the microfluidic device, and the analysis of electrical properties was performed using the patch-clamp technique EPC 10 USB (Heka Electronics, Reutlingen, Germany). Monitoring of the ion current passing through the bilayer was conducted over time using a direct current (DC) excitation set at an amplitude of 20 mV with a time resolution of 100 ms.

4. Conclusions

We applied a straightforward microfluidic approach to realise Rhodopsin GPCR-based photoactivation of transmembrane channels in an artificial bilayer, as observed through the measurement of an electrical current across a free-standing lipid membrane. By repeatedly exposing a GPCR-containing bilayer to light, the opening and closing of cGMP-gated ion channels from the photoactivated outer segment (POS) became clearly visible in the electric current recorded across the membrane. Using cGMP analogues, we demonstrated that the observed photoactivation was most likely caused by cGMP degradation, consistent with the molecular mechanisms of Rhodopsin G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) photoactivation. Since GPCR signalling is a highly complex cascade involving multiple intermediates and regulatory mechanisms, our approach provides an insightful in vitro model to study key aspects of this intricate process. By recreating essential mechanisms of GPCR cell signalling in biomimetic bilayers we made a first step towards the construction of complex, biology inspired, synthetical signalling modules.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K., M.F., R.S., and A.O.; methodology, N.K., M.F. and S.S.; software, N.K. and M.F. and S.S.; validation, N.K. and M.F., M.M. and S.S.; formal analysis, N.K. and M.F. and S.S..; investigation, N.K. and M.F., M.M. and S.S.; resources, R.S. and A.O.; data curation, N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K. and M.F., M.M. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, N.K. and M.F., M.M. and S.S., R.S. and A.O.; visualization, N.K.; supervision, R.S. and A.O.; project administration, R.S. and A.O.; funding acquisition, R.S. and A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (Projects B4, and C1 of CRC 1027) and, in part, by the Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP, RGP0037/2015).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, L. Highlighting membrane protein structure and function: A celebration of the Protein Data Bank. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelokhani-Niaraki, M. Membrane Proteins: Structure, Function and Motion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, B.C.; Aubel, D.; Fussenegger, M. An overview of the diverse roles of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) in the pathophysiology of various human diseases. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1676–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, D.M.; Rasmussen, S.G.F.; Kobilka, B.K. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature 2009, 459, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Zhou, Q.; Labroska, V.; Qin, S.; Darbalaei, S.; Wu, Y.; Yuliantie, E.; Xie, L.; Tao, H.; Cheng, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, S.; Shui, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, M.W. G protein-coupled receptors: Structure- and function-based drug discovery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, L.; Palczewski, K. The G Protein-Coupled Receptor Rhodopsin: A Historical Perspective. In Rhodopsin; Jastrzebska, B., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1271, pp. 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Palczewski, K. G Protein-Coupled Receptor Rhodopsin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006, 75, 743–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, K.P.; Lamb, T.D. Rhodopsin, light-sensor of vision. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2023, 93, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenahan, C.; Sanghavi, R.; Huang, L.; Zhang, J.H. Rhodopsin: A Potential Biomarker for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, P.S.-H. Constitutively Active Rhodopsin and Retinal Disease. In Advances in Pharmacology; Elsevier, 2014; Volume 70, pp. 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Karamali, F.; et al. Potential therapeutic strategies for photoreceptor degeneration: the path to restore vision. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahel, J.A.; et al. Partial recovery of visual function in a blind patient after optogenetic therapy. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khangholi, N.; Seemann, R.; Fleury, J.-B. Simultaneous measurement of surface and bilayer tension in a microfluidic chip. Biomicrofluidics 2020, 14, 024117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khangholi, N.; Finkler, M.; Seemann, R.; Ott, A.; Fleury, J.-B. Photoactivation of Cell-Free Expressed Archaerhodopsin-3 in a Model Cell Membrane. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, S.; et al. Synthetic Light-Activated Ion Channels for Optogenetic Activation and Inhibition. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaupp, U.B.; Seifert, R. Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated Ion Channels. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 769–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, G.; et al. Channelrhodopsin-2, a directly light-gated cation-selective membrane channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13940–13945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, R.H.; Molokanova, E. Modulation of cyclic-nucleotide-gated channels and regulation of vertebrate phototransduction. J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 204, 2921–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parinot, C.; Rieu, Q.; Chatagnon, J.; Finnemann, S.C.; Nandrot, E.F. Large-Scale Purification of Porcine or Bovine Photoreceptor Outer Segments for Phagocytosis Assays on Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. J. Vis. Exp. 2014, 94, e52100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).