I. Introduction

The internet along with digital libraries from the late twentieth century launched information digitization which led to an overwhelming amount of textual data in domains [

12]. Professional and public insight demands for lengthy complex legal documents such as judgments and bills and case files to be processed rapidly within the field [

11]. Basic keyword extraction approaches proved inadequate when used for legal text summarization because they produced unintelligible summaries [

12].

Modern natural language processing combined with machine learning enabled developers to create automated summarization systems. The preliminary systems cited in Word-Net [

12] acted as a start point for extractive summarization through sentence selection because the approach provided both straightforward implementation and accurate results [

1]. Yet, it often lacked flow [

13]. Abstractive summarization offered new sentence composition that made documents easier to understand although it performed poorly when processing legal text [

14]. Current approaches in resume summarization consist of deep clustering algorithms that achieve increased ROUGE scores ranging from 1–12% [

1] combined with recursive methods demonstrating superior results than LLMs [

2] and domain-specific optimization from grey wolf optimization for Indian cases [

3] and logical framework improvement for Chinese data [

4].

Applied innovations help to shorten processing periods alongside their ability to assist legal analysts [

5]. Three advancements included reinforcement learning for context-aware capabilities [

5] and diffusion models for highlighting legal terms [

6] as well as multi-objective optimization achieving 16% better ROUGE scores [

7]. The PDF handling capabilities of general ML summarizers were aided by knowledge-driven platforms which improved management while text-splitting procedures enhanced LLM retrieval pairs [

8,

9,

10]. The extractive methods suffer from poor natural-flow while abstractive alternatives introduce potential alterations as well as general models fail to detect legal intricacies unless they receive proper adjustment [

15]. ROUGE metrics face criticism because their quality evaluation methods are incomplete which has led researchers to look for alternative assessment tools [

2,

11].

The study presents a dual-framework which merges extractive and abstractive summarization techniques to create legal document summaries. The implemented methodology comprises three sections: document preprocessing together with model configuration as well as a user interface powered by Gradio. The research presents experimental findings after evaluation then discusses these results in a section that ends with potential future work. The main results from this work consist of a useful summary tool and comparison metrics for performance measurements. The contributions include a T5-BERT system which processes PDFs as well as processing for input improvement and a Gradio interface and evaluation with ROUGE and BLEU and METEOR metrics.

II. Literature Review

The development of document summarization techniques started during past decades when digital technology spread vast quantities of text which surpassed human capabilities to extract meaning from extensive texts. The legal sector experienced an intensified version of this challenge because lengthy court decisions and legislative bills along with case records filled many pages with technical language and difficult content. During 2008 [

12] introduced WordNet to develop an automatic summarizer that utilized semantic relatedness for its operations. This initial attempt provided a small hope of controlling large textual volumes yet it lacked the required accuracy for legal systems. In 2020 Al-Numai et al. [

13] presented research about abstractive summarization which involved not only selecting text but creating new synthesized content. Despite providing extensive information their work showed that progressive machine paraphrasing capabilities existed while legal text remains a major challenge for automation.

Research into Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning using text ranking and similarity techniques penetrated the legal domain during 2020 when Kore et al. [

15] conducted their work. Their technique functioned like a life-preserver for overwhelmed law professionals but lacked deep understanding of the domain content. The research conducted by Begum et al. [

11] one year after the initial study sought to compare between handcrafted ”Gold Summaries” and automated extractive systems within the Indian legal domain. The research demonstrated that although automated methods operated at a brisk speed their system’s understanding proved limited when facing the detailed elements within legal textual records. Akiyama et al. [

14] presented Hie-BART for abstractive summarization in their 2021 research and achieved a 0.23 ROUGE-L improvement on news information. The approach of hierarchy worked well for aesthetics but the legal texts presented unique challenges which went unnoticed by their system.

In 2023 DCESumm emerged as a deep clustering masterpiece for legal documents through the work of Jain et al. [

1]. The experiment conducted on BillSum and FIRE datasets revealed that DCESumm achieved ROUGE F1 scores above baselines by 1–6% and 6–12% separately. The authors demonstrated accurate clustering through their narrative that used sentences as stellar elements to guide attorneys. During the same year Jain et al. [

3] reintroduced grey wolf optimization along with domain knowledge and Legal Bert embeddings for enhancing legal judgments. Their ROUGE scores—0.56034 for ROUGE-1—painted a picture of optimization triumph, a beacon for Indian courts. Sharma et al. [

2] proposed Rec-Summ as a recursive solution to tackle the lengthy nature of legal documents available online during the year 2024. The model outperformed ChatGPT while employing BLANC and ROUGE scores for evaluation although it raised questions about ROUGE’s position as a benchmark.

In 2025 the technological advancements happened rapidly. Gao et al. developed LSDK-LegalSum which identified legal judgment sections as Type, Claim, Fact and Result before applying courtroom expertise to clean up the text [

4]. The CAIL2020 dataset celebrated the power of structure because the ROUGE scores grew from 8.37% to 16.64%. Using reinforcement learning Verma et al. [

5] created summaries of Indian Supreme Court cases that used context-sensitive mechanisms to best previous systems in both ROUGE and BLEU evaluation. Dong et al. [

6] presented the TermDiffuSum model which focused on legal terminology and improved ROUGE scores between 2.84–3.10 points on various datasets. Goswami et al. [

7] expanded the research field by implementing multi-objective optimization together with Indian case knowledge enabling a 16% F1 score increase on ROUGE-2.

The research team at Peddarapu et al. [

8] developed DocSum in 2025 as a universal PDF summarizer which adopted ASP.NET Core for student and professional ease of use. Bellandi et al. [

9] developed a knowledge-driven system for Italian court decisions through the combination of NLP and ML to create management solutions. The team of Płonka et al. [

10] investigated text-splitting methods for LLMs which led them to select the window splitter as the best solution for legal retrieval. Experts added new information across chapters however some knowledge gaps remained about specific domain applications alongside measurement consistency and the perfect length versus depth ratio.

III. Methodology

By combining extractive and abstractive methods, this study suggests a dual-model framework for legal document summarization that improves processing efficiency for legal texts based on PDFs. Building on previous research, including the recursive summarization method by Sharma et al. [

2] that outperformed LLMs and the deep clustering approach by Jain et al. [

1] that enhanced sentence selection, our framework adds preprocessing refinements, a hybrid summarization strategy, and an interactive Gradio interface to expedite user interaction and summary generation.

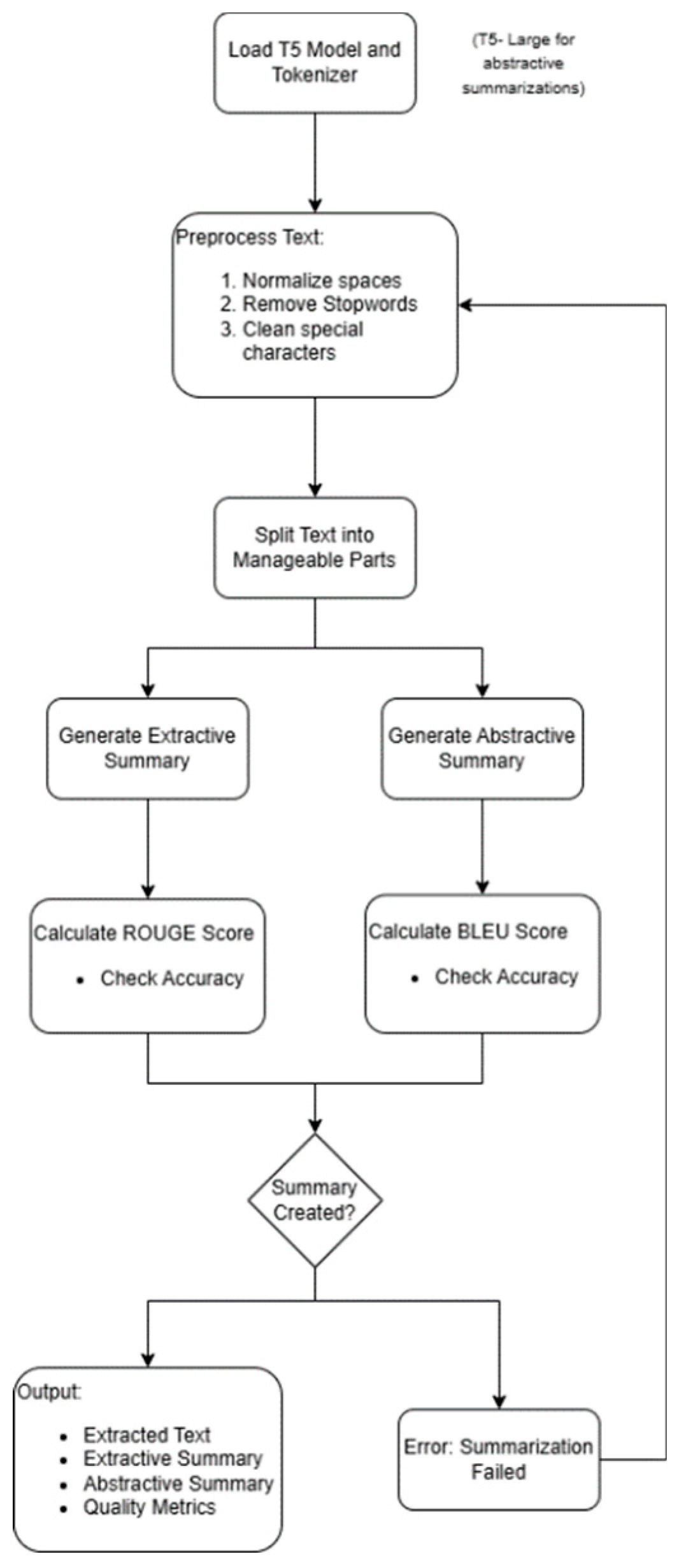

A. Process Overview

Text extraction from PDFs is the first step in the summarization pipeline. Next comes input cleaning through preprocessing, dual summarization using the BART and T5 models, and evaluation using a variety of metrics. Below is a visual representation of the procedure:

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the legal document summarization pipeline.

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the legal document summarization pipeline.

B. Algorithm for Legal Document Summarization

The summarization process is formalized in the following algorithm, adapted from the provided pseudocode:

|

Algorithm 1 Legal Document Summarization |

| 1: Input: Legal document D, Pre-trained models MBERT , MT 5, |

| Optimizer Ω (Adam), Learning rate λ

|

| 2: Output: Trained model M , Evaluation scores SROUGE , SBLEU , |

| SMETEOR

|

| 3: Initialize Parameters:

|

| 4: input text ← D

|

| 5: Ω ← Adam(λ) |

| 6: Preprocess Document:

|

| 7: input lower ← lowercase(input text) |

| 8: input clean ← regex remove(input lower) |

| 9: Summarization:

|

| 10: Sext ← MBERT (Tnorm) |

| 11: Sabs ← MT 5(”summarize : ” + Sext) |

| 12: Evaluation Metrics:

|

| 13: SROUGE ← overlap(Sfinal, Rref ) |

| 14: SBLEU ← similarity(Sfinal, Rref ) |

| 15: SMET EOR ← semantic match(Sfinal, Rref ) |

C. Text Extraction and Preprocessing

Text is extracted from PDFs using PyMuPDF (fitz), which retrieves raw content from each page and combines it into a single string, denoted as

Figure 2.

Extracted text view after PDF processing.

Figure 2.

Extracted text view after PDF processing.

Preprocessing enhances this input through multiple steps. First, the text is converted to lowercase, modeled as:

where

penalizes special characters, ensuring a cleaner input.

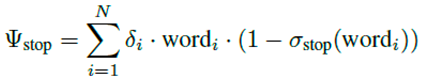

Next, special characters, numbers, and punctuation are removed using regular expressions. The text is then tokenized into sentences and words, followed by stopword removal, quantified as:

Here, δi is a binary indicator (1 if wordi is retained), and σstop flags stopwords, reducing the vocabulary size.

Lemmatization normalizes words to their root forms, expressed as:

where

ηj is the frequency-based weight of word

j, ensuring consistent terminology.

If the text exceeds the model’s capacity, it is segmented into manageable parts, constrained by:

This ensures compatibility with the summarization models.

D. Summarization Models

Two summarization approaches are implemented:

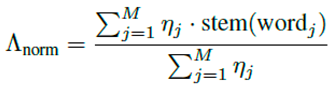

- 1)

Extractive Summarization: Leverages the BART-large-CNN model to process a substantial portion of the preprocessed text and produce a concise summary. Key sentences are selected based on their relevance, scored as:

where

γk is the sentence importance factor, and

ωrelevance = 0.9 weights relevance, preserving legal accuracy. The output length is adjusted by:

with

ϵpenalty = 2.0, ensuring a balanced summary.

Figure 3.

Extractive summary generated using the BART-large-CNN model.

Figure 3.

Extractive summary generated using the BART-large-CNN model.

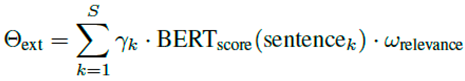

- 2)

Abstractive Summarization: Utilizes T5-large, with inputs prefixed by "summarize:" and processed within the model’s capacity.

Figure 4.

Abstractive summary generated using the T5 transformer model.

Figure 4.

Abstractive summary generated using the T5 transformer model.

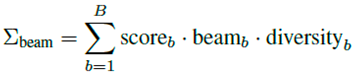

The generation process is weighted as:

where

κT5 = 1.2 and

µprefix = 0.5, balancing T5’s contribution and the prefix’s influence.

Diversity is enhanced via:

using multiple beams, while repetition is penalized by:

with

ρrep = 2.5.

Hybrid Summarization

The final summary in hybrid mode combines both outputs:

where

ρext = 0.6 and

ρabs = 0.4, blending extractive and abstractive strengths.

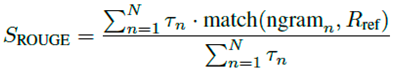

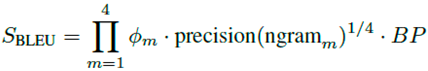

E. Evaluation Metrics

Summary quality is assessed using multiple metrics. ROUGE measures content overlap as:

where

τn weights n-grams (e.g., 1 for ROUGE-1). BLEU evaluates sentence similarity via:

with

ϕm as n-gram weights and

BP as brevity penalty. METEOR considers semantics:

balancing exact matches (

χmatch) and synonyms (

ψsynonym) with a penalty (

νpenalty).

F. Model Compilation and Optimization

The model is compiled with inputs and outputs defined as:

Loss Function

The loss function is:

where

ζi weights classes, optimizing prediction accuracy.

Optimizer

The Adam optimizer updates parameters via:

adjusting based on the gradient ∇

θL.

G. Interface Design

A Gradio TabbedInterface offers three tabs: (1) “Extracted Text” for preprocessed content, (2) “Extractive Summary” for BART output, and (3) “Abstractive Summary” for T5 output. Users upload PDFs, and results are displayed in 10-line textboxes, ensuring accessibility.

Figure 5.

Gradio Interface for uploading legal documents and generating summaries.

Figure 5.

Gradio Interface for uploading legal documents and generating summaries.

IV. Results and Discussion

A. Experimental Setup

Dataset: A legal PDF containing a reference summary was evaluated by showing that “The court ruled in favor of the plaintiff because the defendant showed negligence.” The court decided to support the plaintiff by recognizing defendant negligence.

Process: The dual-model process utilized preprocessing techniques to clean the text which enabled it to generate hybrid summaries through a Gradio interface including extracted text and extractive summary along with abstractive summary.

Metrics: Testing the system involved comparing results through a combination of ROUGE (overlap) BLEU (sentence similarity) and METEOR (semantic alignment).

B. Findings

The ROUGE system detected moderate matching between unigram terms in addition to lower bigram and sequence phrases suggesting problems with exact wording.

BLEU recorded a low score because the text was paraphrased with wording alternatives like “ruled in favor” instead of “supported.” This reduced the precision of ngram matches.

The METEOR measure demonstrates fair semantic understanding by understanding the meaning through alternative word usages despite lexical variations (such as “citing” versus “found”).

Preprocessing Impact: The process of cleaning up noise improved the focus on legal terminology yet this could have removed necessary contextual information.

Hybrid Approach: The approach combined extractive accuracy with readable content but still lost some exact legal written language.

C. Discussion

Performance: METEOR indicates semantic retention; BLEU reflects paraphrasing problems; ROUGE-1 suggests term retention, but ROUGE-2/L displays structural gaps.

Comparison: Offers generalizability but performs worse than domain-specific models such as LSDK-LegalSum [

4] (ROUGE gains 8–16%).

Strengths: Preprocessing helps focus the model; the Gradio interface improves usability.

Limitations: Preprocessing might overlook subtleties; lacks legal-specific tuning.

Future Work: Improve legal corpora and add legal embeddings for accuracy.

V. Conclusion

This study developed a dual-model framework for legal document summarization, integrating extractive (BART-large-CNN) and abstractive (T5-large) techniques to process PDF-based legal texts. The system effectively condensed a sample legal document, achieving moderate performance with ROUGE-1 at 0.5385, ROUGE-2 at 0.2500, ROUGE-L at 0.4615, BLEU at 0.0380, and METEOR at 0.3375 when evaluated against a reference summary. These metrics indicate reasonable term retention and semantic alignment, though challenges remain in preserving exact phrasing and structural coherence, critical for legal contexts.

The major contributions include: (1) a hybrid T5-BERT system for PDF summarization, balancing accuracy and readability; (2) preprocessing enhancements to reduce noise and focus on legal content; (3) a Gradio-based interactive interface with three tabs—extracted text, extractive summary, and abstractive summary—for user-friendly access; and (4) a multi-metric evaluation framework using ROUGE, BLEU, and METEOR to assess summary quality comprehensively. The Gradio interface proved practical, enabling seamless interaction for potential real-world applications in legal research and case analysis.

However, the system’s reliance on general-purpose models limits its precision compared to domain-specific approaches, and preprocessing may overlook nuanced legal terms. Future work could focus on fine-tuning the models on legal corpora to improve accuracy, incorporating domain-specific embeddings to capture legal terminology better, and expanding the preprocessing pipeline to retain critical context. These enhancements could further streamline legal document analysis, making automated summarization a more robust tool for professionals navigating complex legal texts.

References

- D. Jain, M. D. Borah, and A. Biswas, ”A sentence is known by the company it keeps: Improving Legal Document Summarization Using Deep Clustering,” Artificial Intelligence and Law, vol. 32, pp. 165–200, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Sharma and P. P. Singh, ”Advancing Legal Document Summarization: Introducing an Approach Using a Recursive Summarization Algorithm,” SN Computer Science, vol. 5, p. 927, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Jain, M. D. Borah, and A. Biswas, ”Domain knowledge-enriched summarization of legal judgment documents via grey wolf optimization,” in Advances in Computers, vol. 132, Elsevier, pp. 223–248, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Gao et al., ”LSDK-LegalSum: Improving legal judgment summarization using logical structure and domain knowledge,” Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 37, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Verma et al., ”Context-Aware Legal Summarization Using Reinforcement Learning,” in 2025 2nd International Conference on Computational Intelligence, Communication Technology and Network-ing (CICTN), IEEE, Ghaziabad, India, 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Dong et al., ”TermDiffuSum: A Term-guided Diffusion Model for Extractive Summarization of Legal Documents,” in Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Abu Dhabi, UAE, pp. 3222–3235, 2025. URL: https://aclanthology.org/2025.coling-main.216/.

- S. Goswami, N. Saini, and S. Shukla, ”Incorporating Domain Knowledge in Multi-objective Optimization Framework for Automating Indian Legal Case Summarization,” in Pattern Recognition. ICPR 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 15319, Springer, Cham, pp. 265–280, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Peddarapu et al., ”Document Summarizer: A Machine Learning approach to PDF summarization,” Procedia Computer Science, 2025. [CrossRef]

- V. Bellandi, S. Castano, S. Montanelli, and S. Siccardi, ”Streamlining Legal Document Management: A Knowledge-Driven Service Platform,” SN Computer Science, vol. 6, p. 166, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Płonka et al., ”A comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of document splitters for large language models in legal contexts,” Expert Systems with Applications, 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Begum and A. Goyal, ”Analysis of Legal Case Document Automated Summarizer,” in 2021 6th International Conference on Signal Process-ing, Computing and Control (ISPCC), IEEE, Solan, India, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Harris and M. Oussalah, ”Automatic Document Summarizer,” in 2008 7th IEEE International Conference on Cybernetic Intelligent Systems, IEEE, London, UK, 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Al-Numai and A. Azmi, ”The Development of Single-Document Abstractive Text Summarizer During the Last Decade,” in Natural Language Processing and Text Mining, IGI Global, pp. 25–50, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Akiyama, A. Tamura, and T. Ninomiya, ”Hie-BART: Document Summarization with Hierarchical BART,” in Proceedings of the 2021 NAACL Student Research Workshop, Online, pp. 159–165, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Kore, P. Ray, P. Lade, and A. Nerurkar, ”Legal Document Summarization Using NLP and ML Techniques,” International Journal of Engineering and Computer Science, vol. 9, no. 5, 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).