1. Introduction

Lung transplantation is the definitive treatment for patients with end-stage lung disease who have utilized all other medical and surgical options [

1]. Lung transplantation is usually performed without extracorporeal support, but sometimes conventional cardiopulmonary bypass or extracor- poreal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is required during the surgery [

2,

3].

ECMO is a technique that can support or temporarily replace the function of the lungs and/ or the heart in patients with respiratory or cardiac failure. ECMO can also be used as a bridge to lung transplantation, meaning that it can help patients who are waiting for a suitable donor organ to survive and improve their condition [

4,

5]. This is especially important for patients who are critically ill and have a high risk of dying on the waiting list.

There are many types of ECMO strategies and techniques as well as combinations between them, depending on the clinical situation and the goals of therapy in lung transplantation process [

6]

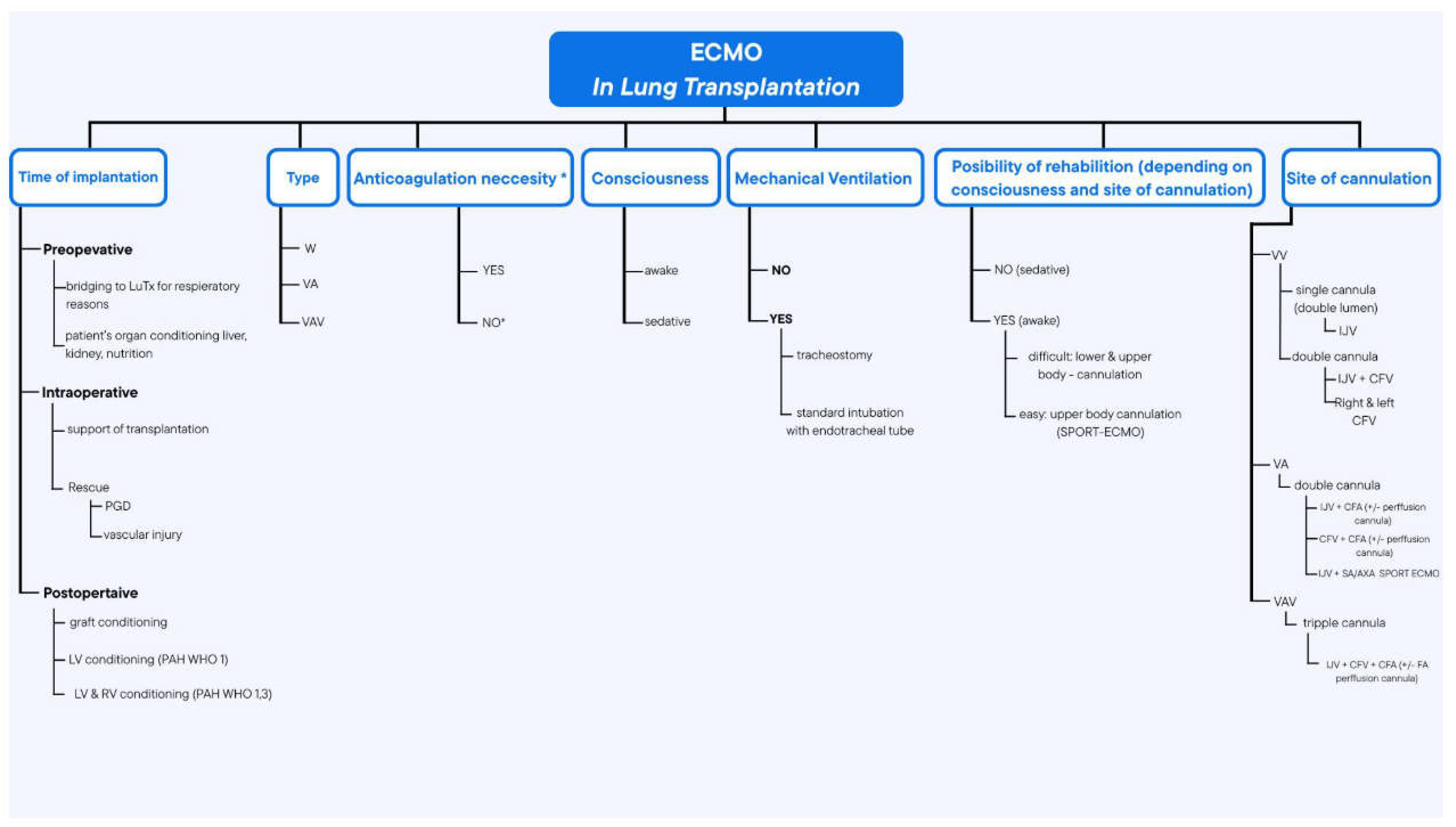

(Scheme 1). These include different modes of ECMO (venovenous - (VV), veno-arter- ial (VA), veno-arterio-venous (VAV)), different cannulation sites (central, peripheral, single-site, dual-site), and different levels of support (partial/full), and depending of the conciousse state - awake or sedative, and stationary or transport ECMO.

It is essential to have a thorough knowledge of these ECMO options, as well as their indica- tions and contraindications, in order to achieve the best possible outcomes for lung transplant candidates and recipients.

ECMO has also become a lifesaving tool in the era of COVID-19, as it can provide a bridge to recovery or bridge to transplantation for patients with severe acute respiratory distress syn- drome caused by the novel coronavirus Sars-CoV-2 (CARDS in opposite to ARDS) [

7].

However, ECMO still requires further development and improvement in terms of trans- portability, miniaturization, biocompatibility, anticoagulation, and complication management [

8].

Nowadays, ECMO therapy is becoming a very individualized therapy due to the choice of the optimal moment of its implementation, very diverse indications for its use and, as the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, its ever-expanding applications. Therefore, when using this technique, it is worth taking all these factors into account, and this article is an attempt to bring closer the applications of this device and this technique and to share the results achieved in the authors’ center against the background of the results of other European and world centers.

2. Materials and Method

The authors of this article present their 6-year experience, coming from the largest national center and one of the largest in central-east Europe for lung transplantation. We share our out- comes as well as our insights and challenges in applying different ECMO strategies and tech- niques. A summary of all these strategies, techniques and modes of conducting patients on ECMO in the period before lung transplantation, during transplantation and after transplantation presents

Scheme 1.

Data are presented as mean +/- SD for normally distributed quantitative variables and medi- an with IQR for non-normally distributed ones. Qualitative data are presented as percent of cases with 95% confidence interval. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank test to compare curves. Linear regression analysis was used to calculate trends and vari- ability in the number of procedures (transplantations) over time.P values <0,05 were considered significant.

Analyses were performed using R programming language in RStudio environment.

3. Results

3.1. Key Outcomes

In the last 6 years (2018-2023), we performed 219 lung transplantations (double lung trans- plantations (DLTx) accounted for 97,3%; n=213) and ECMO was used in 56 cases of them (25.6%) in almost all types of pulmonary diseases, both in adults and children (n=9; 4,1%), in- cluding rare diseases and also in the most demanding entity such as lung re-transplantations in the late period (years) after primary LTx for various indications mainly due to chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD)

(Table 1).

The typical populational and anthropological characteristics of the patients are presented in

Table 2 and Table 3 The confidence intervals allow for estimating the occurrence of the studied feature in the population based on our sample.

The ECMO system was incorporated in almost every possible types of strategies and tech- niques, as well as combinations between them, depending on the clinical situation and the goals of therapy (

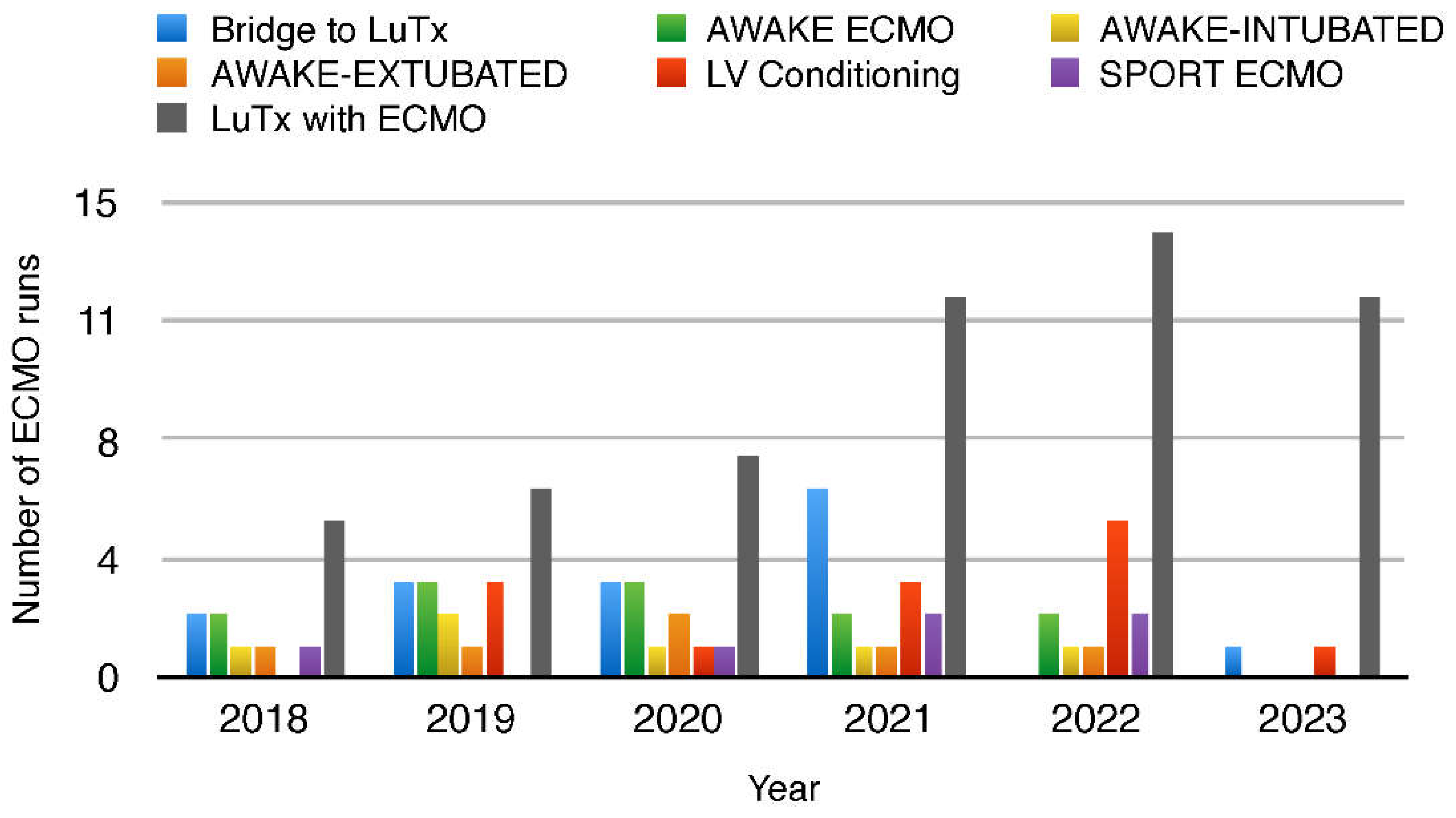

Figure 1).

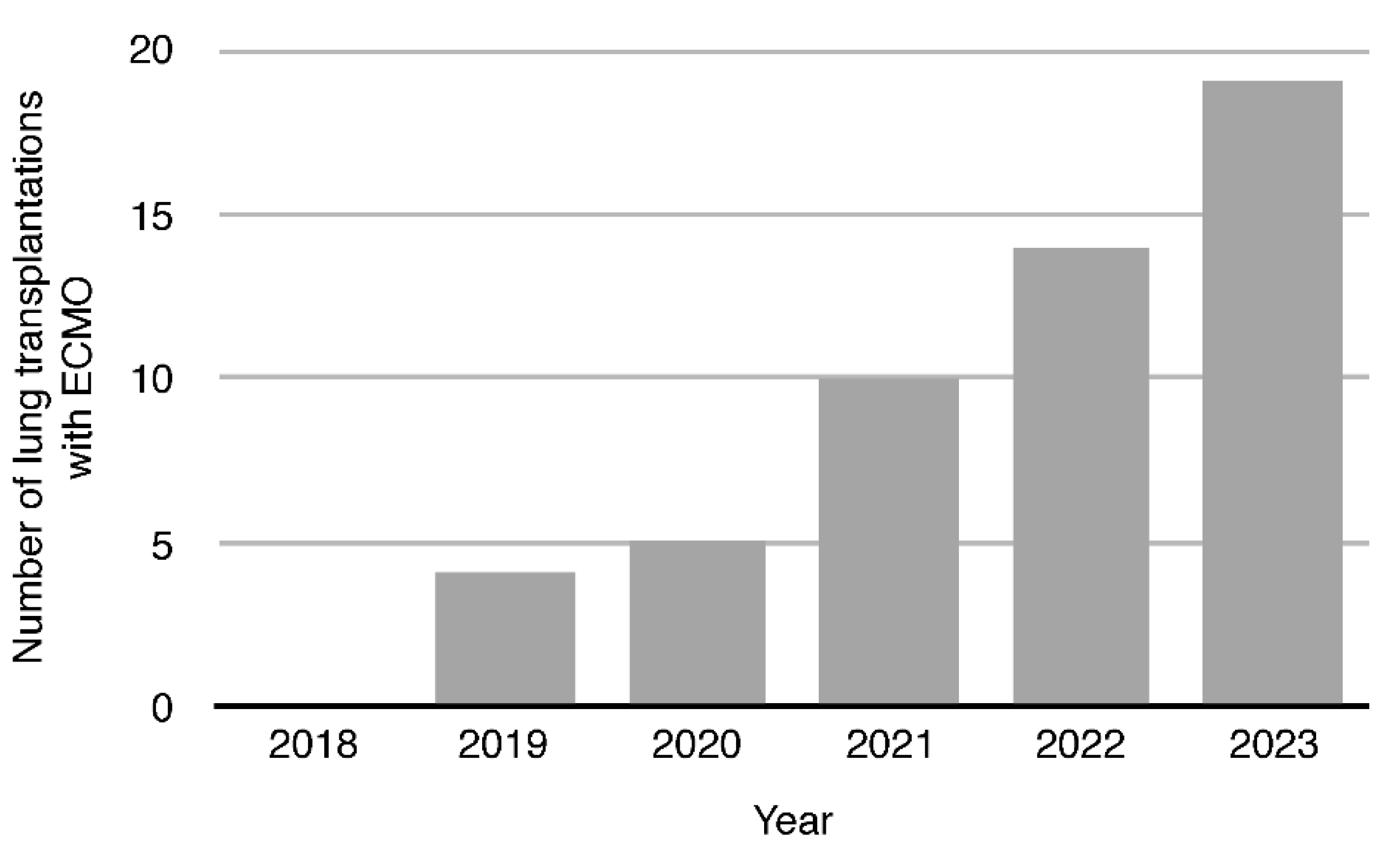

In each year, the number of LTx performed with ECMO support increased and the trend of that increase was statistically significant (p=0,03) in our material, reflecting the increasingly dif- ficult population of patients undergoing transplantation in subsequent years

(Figure 2). This increase was noticeable since 2020, when a new disease entity - COVID-19 appeared, and the experience gained then allowed to still use ECMO especially in patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH).

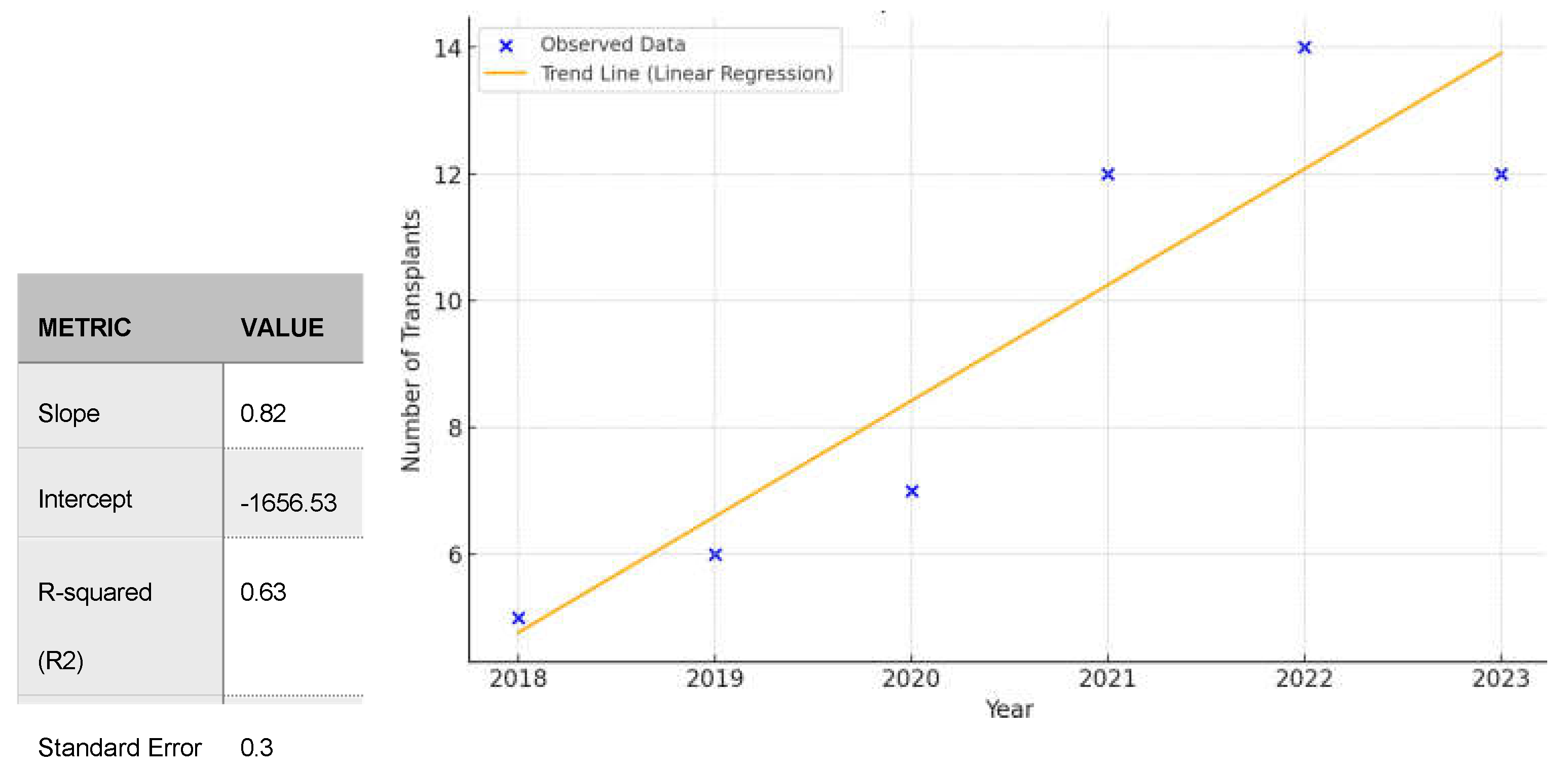

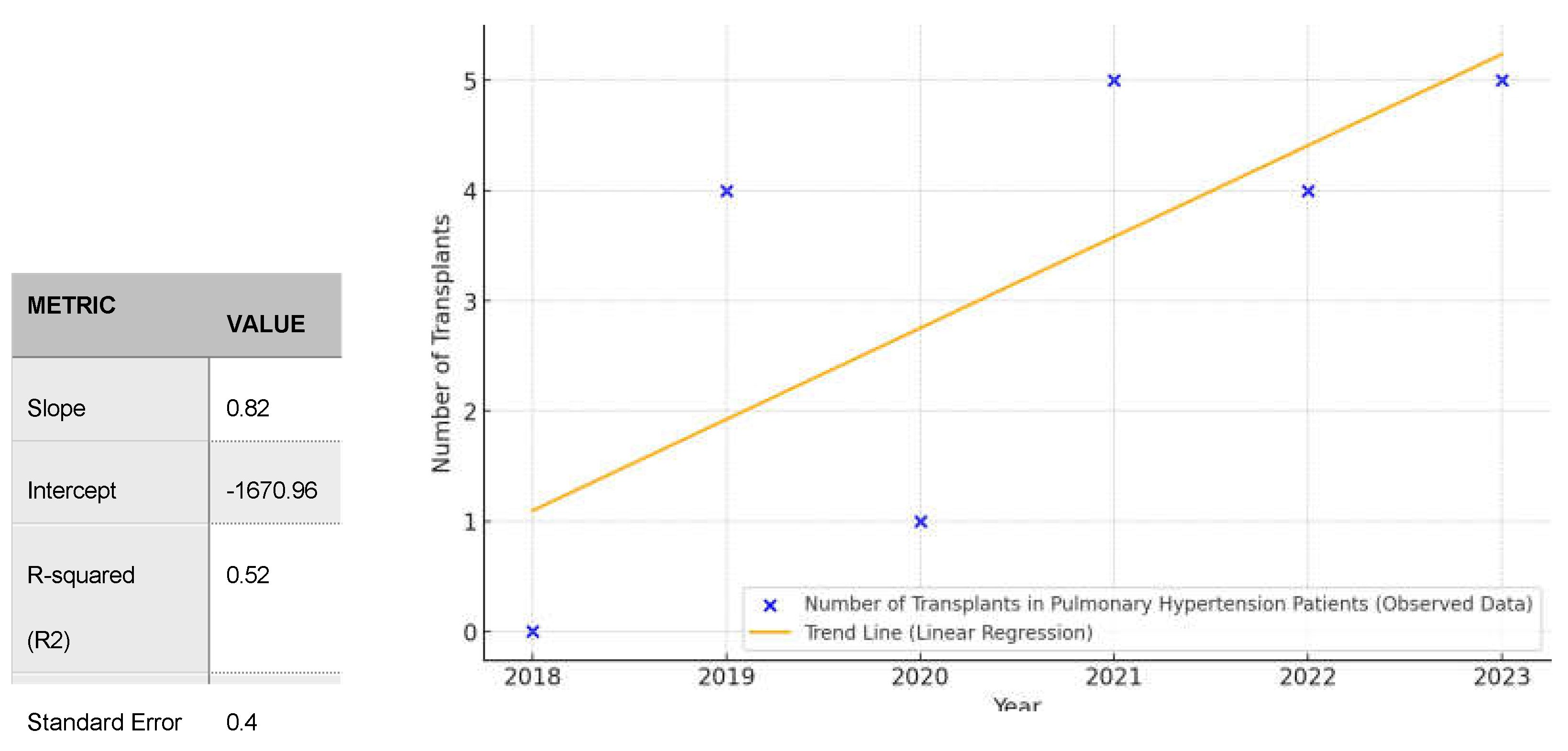

PH is the result of such devastating diseases as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) or pul- monary arterial hypertension (PAH) including idiopathic form of PAH (iPAH). Increasing trend in number of lung transplantation in patients with iPAH did not reached statistical significance (p= 0,1) however it indicates increasing tendency (Slope 0,828; R2-0,52)

(Figure 3). Total in- crease in LTx in iPAH is depicted in

Figure 4.

Another example of the increase in the frequency of ECMO applications in lung transplanta- tions is the fact that in 2023 alone, out of 36 LTx, the ECMO system was used 12 times, which is 33.3% of the total number of transplants that year.

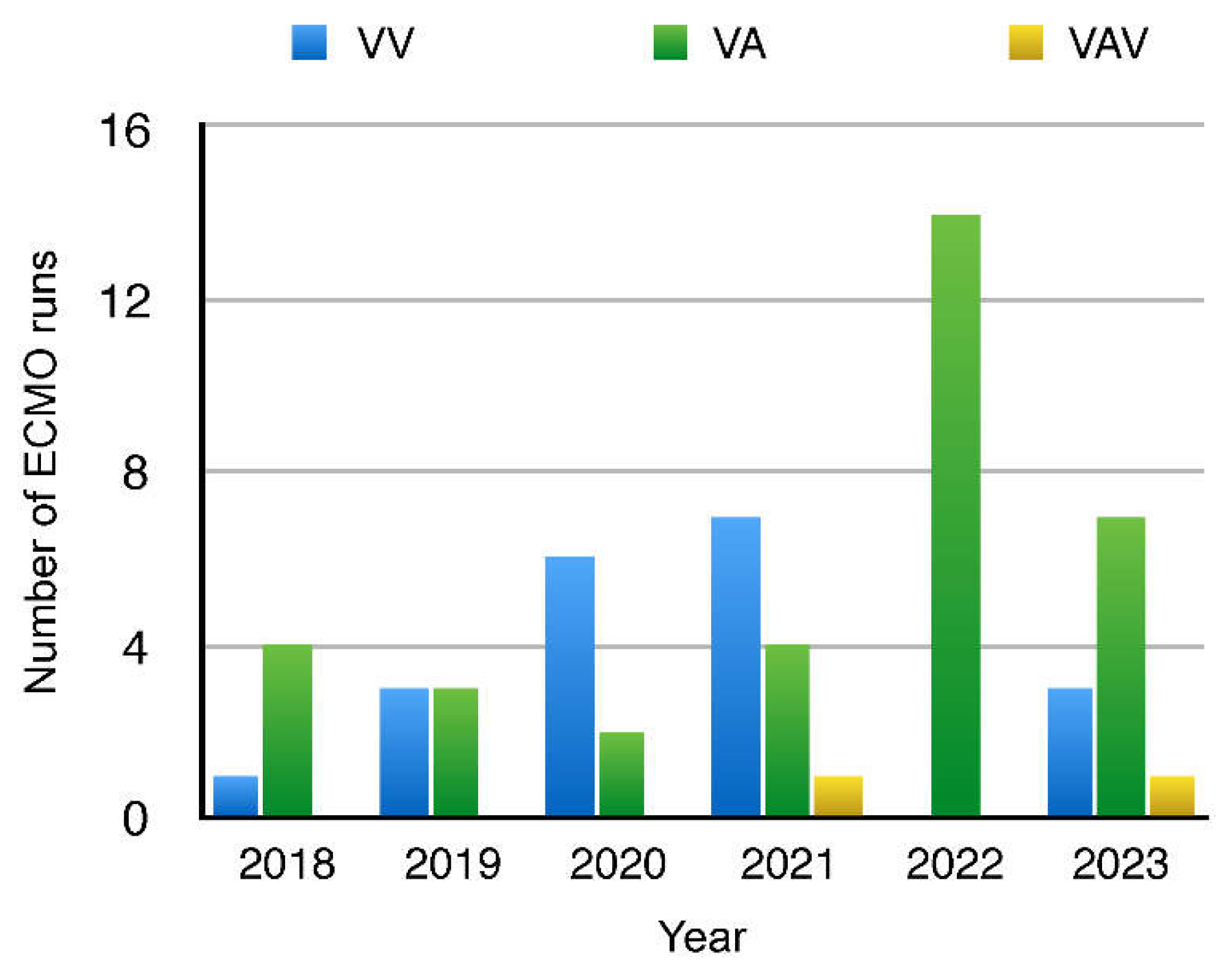

The leading mode of ECMO was VA-ECMO (n = 34, i.e., 60.7%), followed by VV-ECMO (n = 20, i.e., 35.7%) and in a much smaller amount VAV (n = 2, i.e., 3.6%) (

Figure 5), and the number of bridges to transplantation (BTT) was 14, which is 25,0% of all ECMO runs performed in our center (

Figure 1). Both the dominant VA-ECMO mode and the number of bridges to trans- plantation evidence an increasing number of patients with concomitant deterioration of heart function or significant pulmonary hypertension and with a severe clinical condition at baseline, respectively. The median total time that patients spent on ECMO support in our population was

66.2 hours (q1-q2: 7.05-266) (

Table 3) and It can be assumed that the time a given patient was supported by the ECMO system is a surrogate for the severity of the patient’s clinical condition at the time of ECMO implantation.

The mortality rate in patients undergoing lung transplantation with ECMO therapy (regard- less of whether before or after 30 days of transplantation) and the 30-day mortality rate after transplantation in this group of patients were 17.9% (95%CI: 7.86–27.94%) and 12.5% (95%CI: 3.84–21.16%), respectively (

Table 4).

(Table 4). The most frequent complications in lung trans- plant patients treated with ECMO were cannulation site complications (5,4%), neurological (8,9%) and hemorrhagic (21.4%).

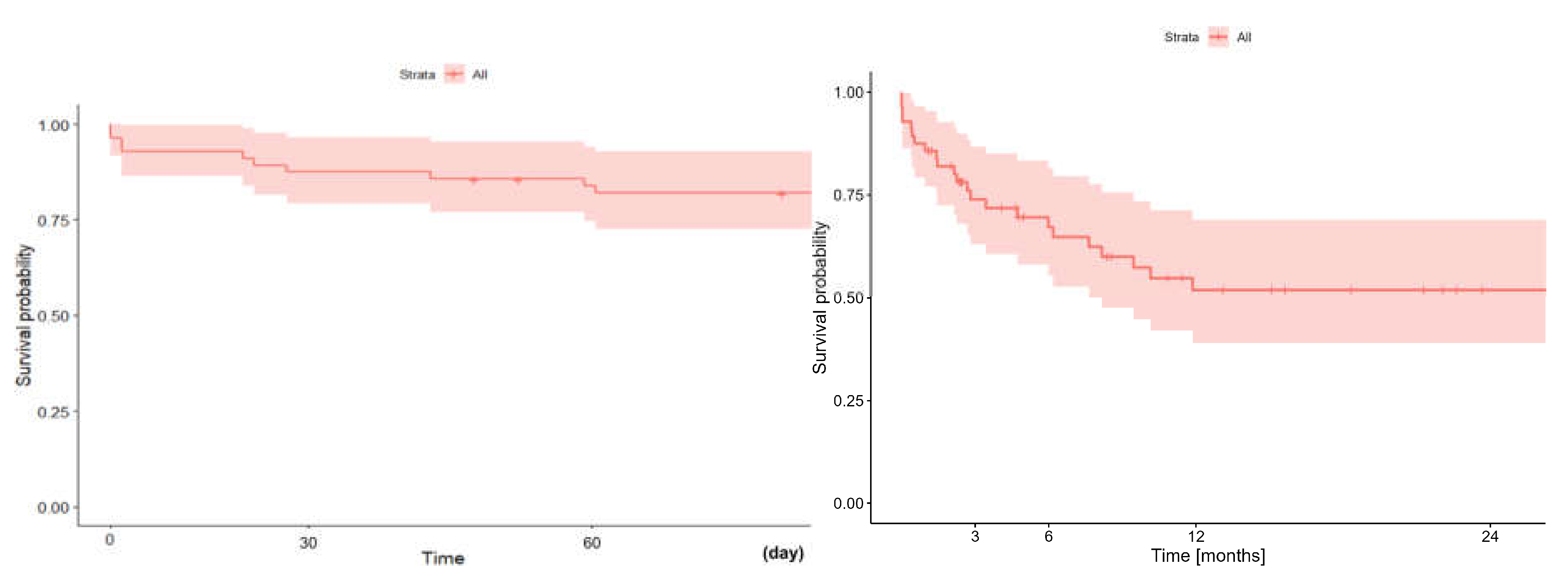

In terms of early (60-day) and long term (two-year) survival of patients, who underwent lung transplantation with ECMO support (regardless of the type: VV vs. VA, cannulation method, consciousness state) was 82,0% (95%CI: 72,5-92,8%) and 51.9% (95%CI: 39.0-69.0%), respec- tively

(Figure 6). The median hospital stay after ECMO decannulation was 29 days (q1-q2: 21,5-41,5)

(Table 3).

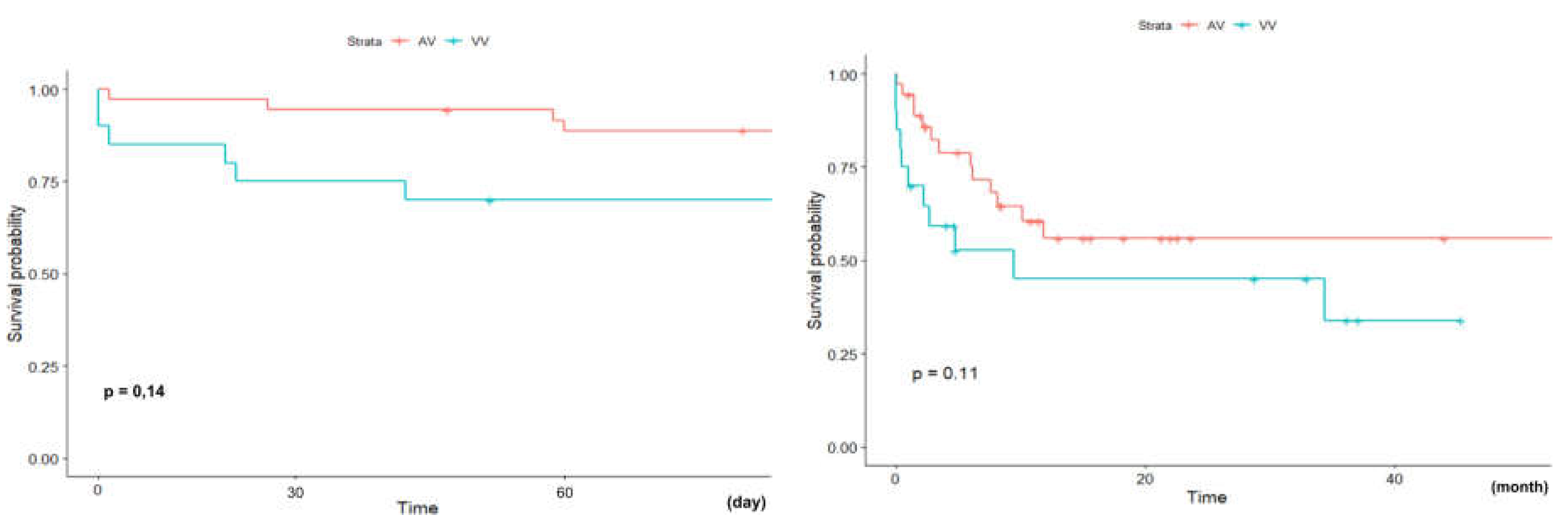

3.2. VV-ECMO vs. VA-ECMO - Outcomes

We performed a comparative analysis of patients survival depending on which form of ECMO therapy was used VV (n=20/56; 35,7%) vs. VA (n=36/56; 64,3%). Intuitively, it seems that patients requiring VA-ECMO are in a worse clinical situation than those who require only VV-ECMO, because in addition to respiratory problems, they also have issues of RV or biventric- ular failure, with sometimes secondary organ failure (kidney, liver).

Patients requiring VA-ECMO support usually have higher risk of complications and death which is associated with limb ischemia distal to the area where cannulation is performed, occur- rence of Harlequin syndrome, and just because these patients necessitating VA-ECMO are more likely to have preoperative circulatory failure which obligate infusion of catecholamines with its widely known side effects [

9,

10,

11].However, in our analysis we did not show significant dif- ference in early (60-day) and long-term (two-year) survival depending on the mode (VA vs. VV) in which patients were supported: 88,7% (95%CI: 78,9-99,8%) vs 70,0% (95%CI: 52,5-93,3%) (p=0,14) and 55,9% (95%CI: 40,0-78,0%) vs 45,1% (95%CI: 26,6-76,7%) (p=0,11) respectively (

Figure 7).

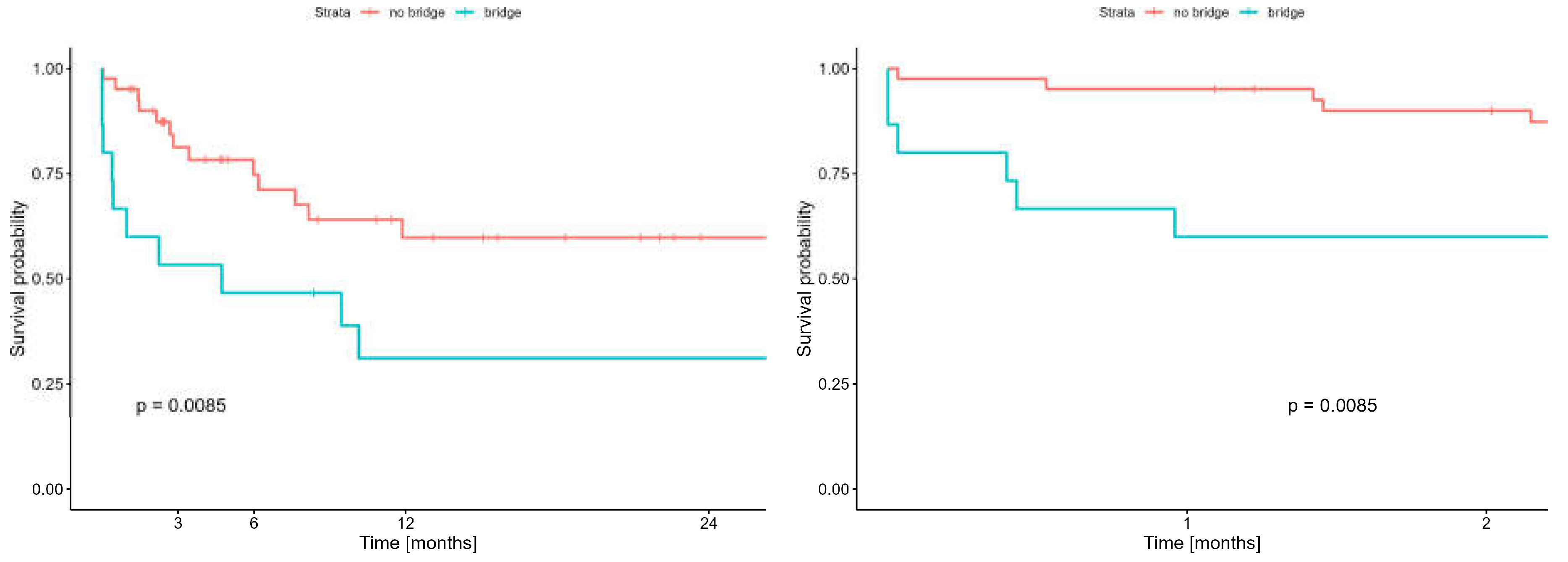

3.3. Bridge to Transplantation (BTT) - Outcomes

In accordance with the latest trends in ECMO therapy, we also used it as a bridge to trans- plantation (BTT; n = 15; 26.8% of all patients on ECMO), including 12 patients (80%) who were on awake-ECMO mode, half of whom were extubated and half intubated, respectively

(Scheme 1; Figure 1) [12,13]. Some of these cases of awake-ECMO that were intubated could be called an

intermediate form of awake-ECMO mode i.e., intubation performed through tracheostomy in patient treated on ECMO in awake state (

Scheme 1, Figure 1). Median time of bridging patients with ECMO to LTx was in presented material 19 days (q1-q2: 15,5-28)

(Table 2).

Taking into account the early survival (60-day) results of bridged patients to LTx with ECMO and non bridged with ECMO who were however applied ECMO system at other stages of lung transplantation, no statistically significant difference in survival was demonstrated, and was 66.7% (95%CI: 46.6-95.3%) and 90.0% (95%CI: 81.1-99.8%), respectively (p=0.067). In contrast two-year survival of patients undergoing bridging therapy to LTx with ECMO were signifi- cantly worse than in patients who did not undergo bridging therapy but who received ECMO at other stages of lung transplantation and was: 31.1% (95%CI: 14.2–68.1%) vs 59.8% (95%CI: 44.6–80.2%) (p = 0.0085) respectively.

(Figure 8).

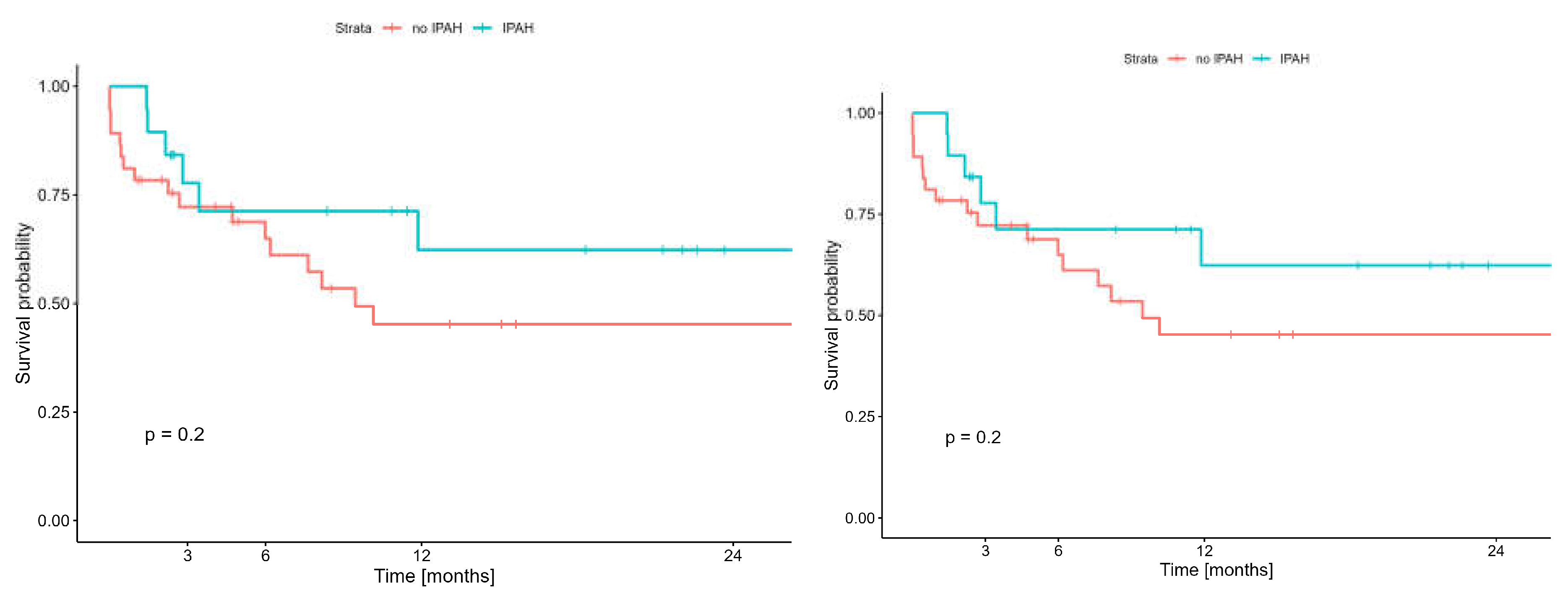

3.4. Pulmonary Hypertension Patients and ECMO - Outcomes

An important group of patients in our material are those with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (iPAH), because the results of transplantation in this group may affect the survival results of the entire population of patients undergoing lung transplantation with ECMO usage. The group of patients with iPAH are the most burdened patients undergoing lung transplantation with ECMO usage, because in addition to respiratory failure, they are dealing with varying de- grees of right ventricular failure, and immediately after surgery, additionaly left ventricular failure occurrence is not uncommon [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. In the years 2018-2023, we per- formed transplantations of 19 patients with iPAH in whom we utilized VA-ECMO (n=19/36; 52,8% of VA-ECMO patients) which constitutes 33,9% of all patients undergoing ECMO therapy (n=19/56) and 8.7% of all transplanted (n = 19/219).

Early (60-day) and long-term (two-year) survival analysis of patients with iPAH undergoing lung transplantation with ECMO did not show statistically significant difference compared to survival of patients with other diseases undergoing lung transplantation on ECMO and was: 89.5% (95%CI: 76.7-100%) vs 78,4% (95%CI: 66,2-92,8%) (p = 0,20) and 62,3% (95%CI: 41.8-93.0%) vs. 45,3% (95%CI: 30,1-68,0%) (p=0,20) respectively

(Figure 9).

3.4.1. Left Ventricule Conditioning

Achieving such results were possible thanks to applying VA-ECMO at the appropriate time and maintaining it in the postoperative period according to the concept of postoperative LV con- ditioning with VA-ECMO. We introduced this concept (LV conditioning) in our country in 2019 and since then we have used it postoperatively in 13 patients

(Figure 1), i.e., 68% of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) (n=13/19) and 23,2% of all ECMO population patients (n=13/56). In 2022 we also successfully introduced pre-transplant LV conditioning, simultaneous- ly conditioning injured kidneys and liver (n=1; 5% of PAH patients) [

20].

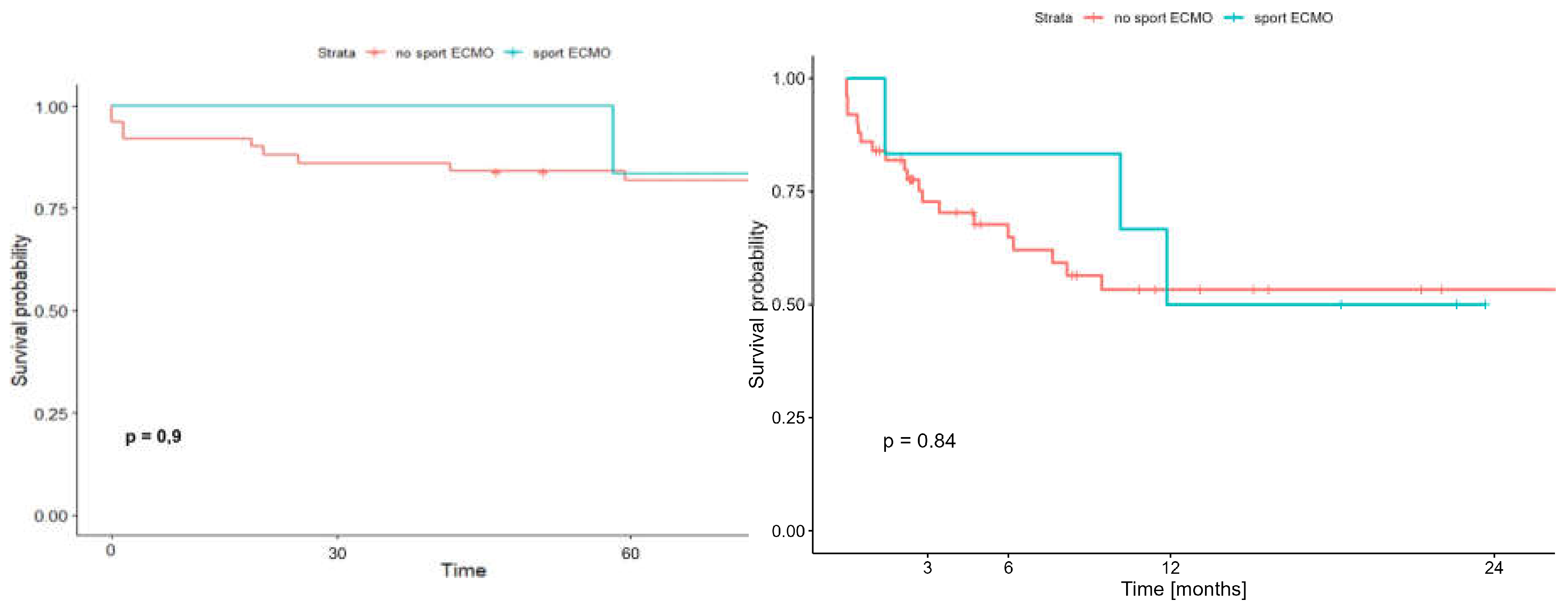

3.4.2. Sport ECMO (VA-SPORT ECMO and VV-SPORT ECMO)

We performed LV conditioning both in the classic VA-ECMO mode with peripheral cannu- lation and in 6 patients (n=6/19; 10.7% of patients with pulmonary hypertension) in the most ad- vanced form, i.e., in the SPORT-VA-ECMO variant, which constituted 16.7% (n=6/36) of all pa- tients undergoing lung transplantation using VA-ECMO.

(Figure 1 and Figure 5).

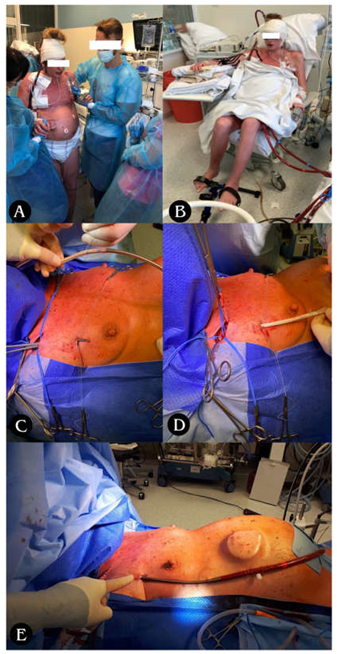

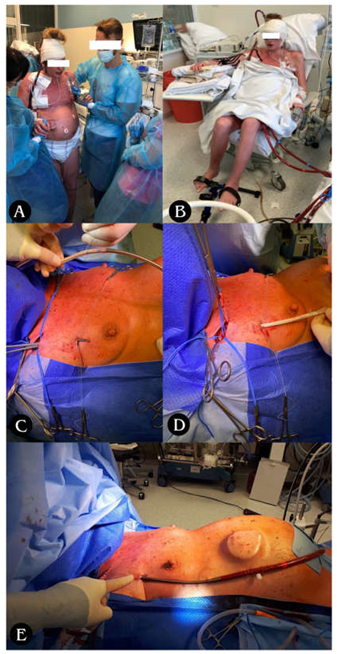

The SPORT-VA-ECMO variant for postoperative LV conditioning assumes that the patient’s groin is free from ECMO cannulas thanks to which the patient retains the ability to move around, fully rehabilitate and feed orally for the duration of ECMO [Photo 1: A and B]. The cannulas are then inserted in the SPORT-VA-ECMO variant through internal jugular venous access (cannula drawing blood - so-called “venous cannula” - V) and through arterial access through the right subclavian artery or right axillary artery (cannula returning blood - so-called „arterial cannula” - A)

Photo 1. A: Ability to move B: Ability to rehabilitate for the duration of ECMO. C-E: Stages of arterial cannula implantation through right subclavian/axillary artery; C: Tunneling of the vascular graft with arterial cannula towards the subclavicular/axillary artery; D: Suturing of the vascular graft to the subclavian/axillary artery with a continuous suture (non-absorbable monofilament 5/0); E: Closing the wound above the vascular anastomosis, attaching the cannula to the skin, starting the ECMO system.

In the SPORT-VV-ECMO variant (used for other than PH patients support), the cannula is usually a single one, inserted through the right internal jugular vein to right atrium, and acts as both a blood drawing and simultaneously returner thanks to the special design of the cannula called double lumen cannula (Photo 2).

The results of early (60-day) survival and long term (2-year) survival of patients supported and transplanted with SPORT ECMO did not differ significantly from the survival of patients who received other forms of ECMO support and were 83.3% (95%CI: 58.3-100.0%;) vs. 81,9% (95%CI: 71,9-93,3%) (p=0,9) and 50.0% (95%CI: 22.5-100.0%) vs. 53,3% (95%CI:39,8-71,4%) (p=0.84) respectively

(Figure 10).

3.5. Covid-19 - Related End-Stage Lung Disease; ECMO Support and Transplant - Outcomes

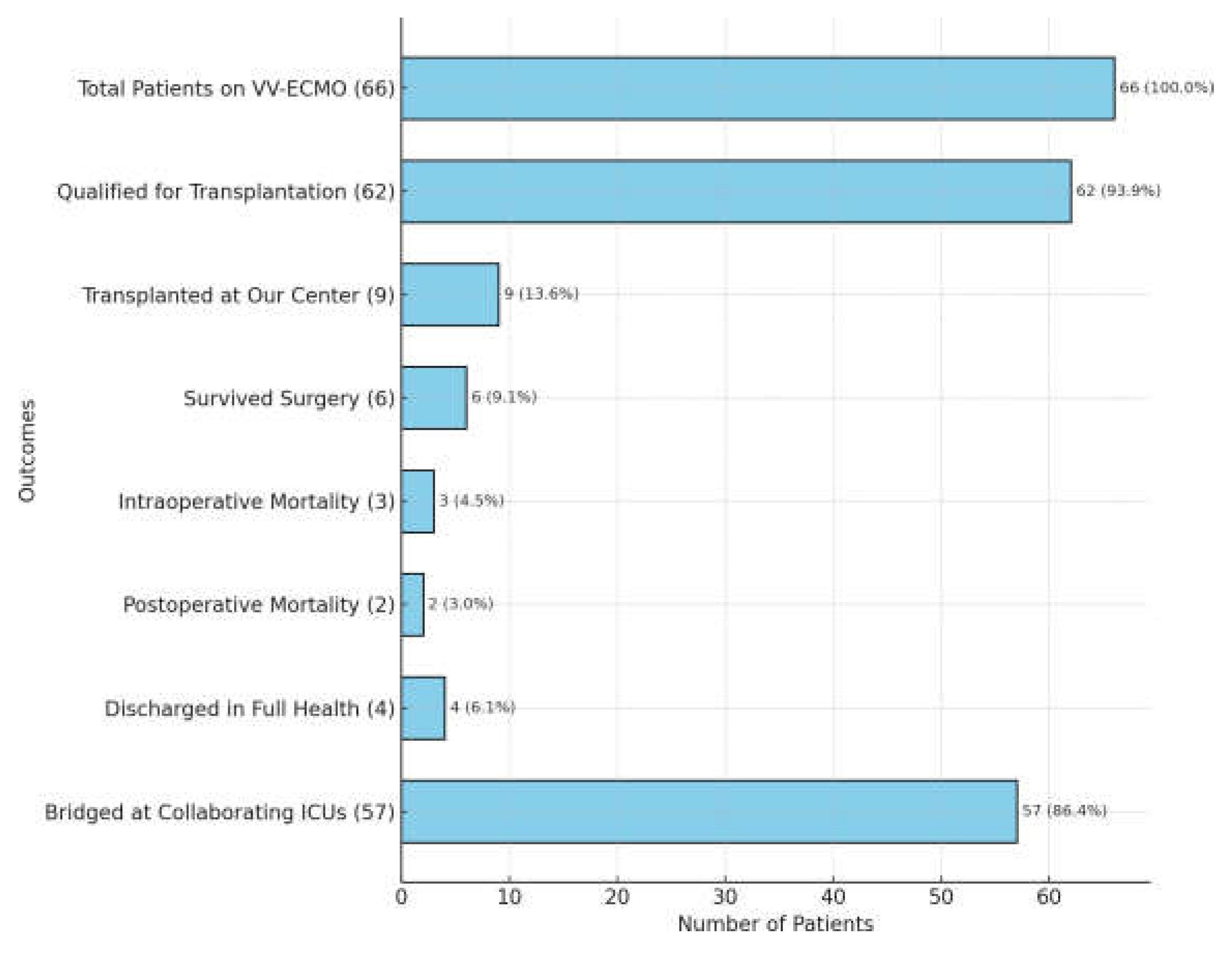

A new group of patients that emerged recently and attracted attention is presented in the analysis of 119 potential lung transplant candidates referred to our department during an 11-month period (from July 2020 through June 2021) following COVID-19 infection that resulted in severe respira- tory failure.

Among this group, all required respiratory support, including oxygen therapy, mechanical ventila- tion, ECMO, or a combination of ventilator and ECMO. Notably, 55.5% (n=66) of these patients were placed on VV-ECMO and goal of the therapy was: bridge to recovery, and in resistant cases not responding to treatment bridge to lung transplantation. Out of the 119 patients, 93 (78.2%) were eligible to proceed with the lung transplant qualification process, and 62 patients (52.1%) completed the process having no contraindications. Among these 62 qualified patients, 47 (75.8%) died before a suitable organ donor could be identified, while 6 patients (9.7%) recovered sufficien- tly to be weaned off ECMO and mechanical ventilation and discharged home. Nine out of 66 pa- tients (13.6%) were bridged to lung transplantation using ECMO in our Centre, and all underwent the procedure while the other 57 patients on VV-ECMO were managed and bridged at collabora- ting intensive care units but did not proceed to transplantation at our institution

(Figure 11).

When focusing on the subgroup of patients bridged on VV-ECMO at our center who ultimately underwent lung transplantation (N=9), the survival rate post-surgery was 44.4% (N=4/9), and the postoperative mortality rate was 22.2% (N=2/9). When contextualized within the larger group of 66 patients on VV-ECMO, the survival to hospital discharge (6.1%) and postoperative mortality rate (3.0%) underscore the critical complexity of managing these cases. Outcomes reflecting sig- nificant challenges faced by this population are presented in

Figure 11.

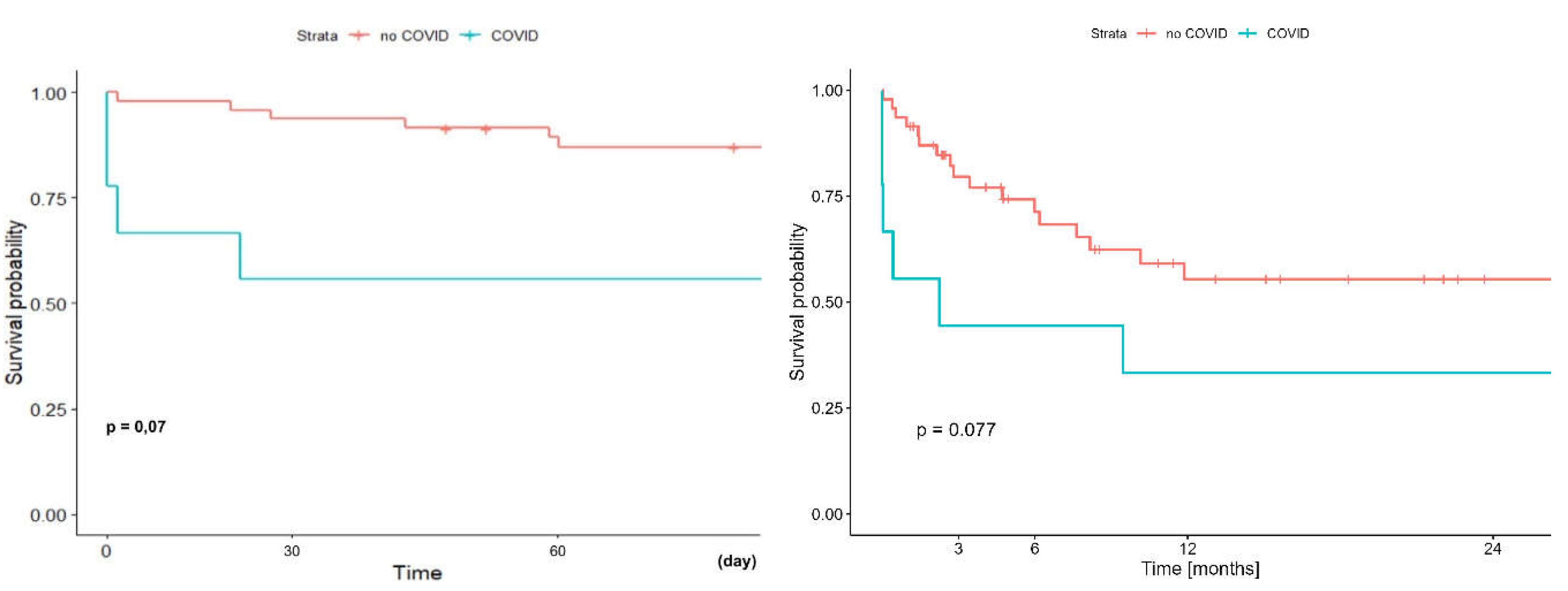

Early (60-day) and long term (two-year) survival analysis showed a trend towards worse survival in the group of COVID-19 patients supported with ECMO and undergoing LTx vs pa- tients undergoing LTx with ECMO but without Covid-19 and it was 55.6% (95%CI: 31-99.7%) vs 87,0% (95%CI: 77,9-97,3%) (p=0,07) and 33.3% (95%CI: 13.2-84.0%) vs. 55,4% (95%CI:41,2-74,6%) (p=0,077) respectively

(Figure 12).

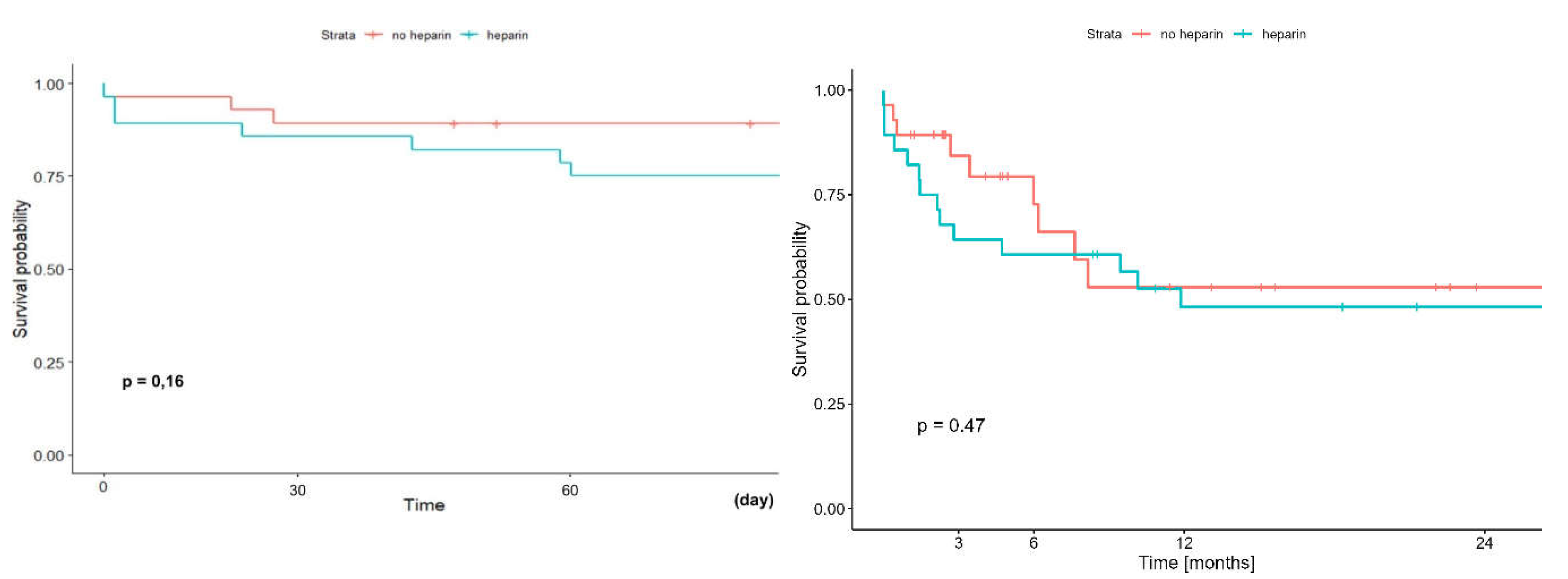

3.6. Heparin Usage and ECMO - Outcomes

In some cases of lung transplantation, when there was a risk of significant bleeding, e.g., coagulation disorders and hematological disorders, patients after pleurodesis, after previous in- ventions in pleural cavity, specific therapy in patients with iPAH (additionally increasing the risk of hemorrhagic complications) - we refrained from using heparin during ECMO therapy.

We therefore conducted an analysis of complications and survival depending on whether patients received unfractionated heparin during ECMO therapy or not. In this regard, the most worrisome complications are

thromboembolic events and their most severe form,

neurological complications. In our study, we did not observe a statistically significant increase in the number of such events

(Table 5).

The early (60-day) and long term (2-year) survival of patients undergoing LTx with ECMO depending on whether they received additional doses of heparin or not, did not differ significantly and was in the group

without vs.

with additional heparin 89,3% (95%CI: 78,5-100,0%) vs 75,0% (95%CI: 60,6-92,9%) (p=0,16) and 52,9% (95%CI: 33.7-83.0%) vs. 48,2% (95%CI: 32,4-71,7%) (p=0,47) respectively

(Figure 13).

4. Discussion

4.1. Introduction and Purpose of the Study

This study examines the use of ECMO in different strategies and techniques in patients with se- vere respiratory failure undergoing lung transplantation. Statistics show that there are more and more centers that already routinely use ECMO in almost every even elective lung transplantation [

21,

22,

23]. Based on 6 years of experience this work contributes unique and practical insight into the evolving role of ECMO in lung transplantation, particularly in resource-constrained or developing ECMO programs. As one of the largest single-center reports from Central and Eastern Europe, this study demonstrates how various ECMO techniques—including SPORT-ECMO, awake-ECMO, and post-transplant LV conditioning—can be successfully implemented outside of high-volume Western European or North American centers. Importantly, this report illustrates real-world applicability across a broad patient spectrum, including complex cases such as re- transplantations, pediatric recipients, and COVID-19-associated lung failure. While randomized data are lacking, our observational findings provide clinically relevant guidance, especially in ECMO program expansion and in centers striving to adopt more advanced ECMO protocols. The practical knowledge shared here may serve as a benchmark for other transplant centers exploring how to integrate newer ECMO strategies into their clinical workflow, while still achieving out- comes that are comparable to international benchmarks.

4.2. ECMO Results and Comparative Analysis

The survival results presented in this study are consistent with previously published results from other leading centers [

24]. The 1-year survival rate of 85.7% and the 2-year survival rate of 51.9% in patients supported by ECMO are consistent with data from leading transplant programs worldwide. For example, the centers in Pittsburgh and Hanover reported similar 1-year survival rates, ranging from 74% to 83%, depending on the study period and patient cohort studied [

21,

25]. These endpoints support the role of ECMO in the treatment of critically ill patients undergo- ing lung transplantation while also demonstrating the learning curve required to achieve optimal outcomes [

26].

The variability in long-term survival between centers is likely related to differences in patient selection (age at transplant, disease for which the patient was transplanted, comorbidities, use or not of immunosuppression), ECMO protocols, and postoperative management (type and level of immunosuppression in the long term). For example, early survival rates in the initial Pittsburgh studies were lower, likely due to earlier stages of ECMO program development. Over time, steady improvements have shown that ECMO can be successfully incorporated into the lung transplant process, provided that the approach is tailored to the strengths of the centers and pa- tient characteristics.

4.3. VA vs. VV ECMO

VA-ECMO is often used in patients who present with more severe diseases like cardiac dysfunc- tion or pulmonary hypertension, while VV-ECMO is reserved for pure respiratory failure. In our center, the dominant form of ECMO therapy was VA (n=36/56; 64.3%) vs. VV (n=20/56; 35.7%). VA-ECMO is often considered more demanding to manage, with more complications (such as vascular complications due to the need for arterial cannulation or thromboembolic complications), and therefore it is believed that the results in terms of early and long-term sur- vival should also be worse compared with VV-ECMO. However, meticulous perioperative care and advanced protocols have mitigated the differences in outcomes, while increasing the flexibili- ty of ECMO to meet different clinical needs without compromising long-term survival. This comparison proved that there was no statistically significant difference in survival outcomes be- tween VA and VV ECMO modes. One-year survival was 88.7% for VA-ECMO and 70.0% for VV-ECMO, with two-year survival rates of 55.9% and 45.1%, respectively. These results are consistent with previously reported findings by other research groups that suggest that ECMO modality—regardless of whether it primarily supports cardiac or respiratory function—does not inherently affect long-term survival when managed appropriately.

4.4. Awake ECMO and Rehabilitation

Awake ECMO is an innovative method that has been developed over the last few years and is gaining popularity, as many reports have shown that it not only reduces the number of complica- tions related to prolonged sedation and intubation, but also improves survival at 6 months of fol- low-up (80% in the awake ECMO group versus 50% in the Mechanical Ventilation group (P = 0.02) [

27]. In this study, awake ECMO was successfully used in completely extubated patients as well as in tracheostomy patients continuously or intermittently supported by mechanical ventila- tion, allowing early mobilization and preoperative conditioning. Reports from other institutions suggest similar benefits, emphasizing the potential of awake ECMO to improve survival by, among other things, preserving diaphragmatic function and reducing postoperative complications [

28].

4.5. SPORT-ECMO

In addition, we have also used advanced ECMO configurations such as SPORT-ECMO, allowing patients to remain conscious and fully mobile while on ECMO support. This technique has been extensively and thoroughly described (including surgical description) by the Columbia University group, although not in lung transplantation surgery [

29,

30,

31]. It utilizes subclavicular/axil- lary cannulation, leaving the femoral vessels free, allowing patients to stand upright, move around, and enhance rehabilitation efforts, while minimizing risks such as limb ischemia, which may be increased in non-sport ECMO techniques, where appropriate limb protection is required by implantation of a so-called nutrient cannula [

32]. Although complications such as upper limb edema or infections have been reported in other studies, they were successfully treated in our cohort, confirming the feasibility of this advanced strategy [

33].

4.6. Bridge to Lung Transplantation (BTT)

Patients undergoing bridge to lung transplantation using ECMO are at increased risk for a variety of complications (vascular complications related to cannulation, hemorrhagic, thromboembolic, infectious), with this study showing a 1-year survival of 31.1% compared with 59.8% in patients receiving intraoperative or postoperative ECMO alone. The number of bridges to transplantation (BTT) was 15, which is 26.8% of all ECMO runs performed in our center and compared to other leading centers, this is a quite large number. In the material from the center in Hannover, out of 917 patients undergoing LTx - 68 (i.e., 7%) required the use of ECMO as a bridge to transplanta- tion. Their study found in-hospital mortality to be significantly higher in patients who required pre-transplant ECMO bridging therapy compared with those who did not require such therapy (15% vs. 5%, P = 0.003) [

21]. The survival of patients bridged to ECMO to transplantation and undergoing transplantation at the center represented by Hozenaker was 66% (1 year), 58% (3 years), and 48% (5 years), whereas among patients bridged to re-transplantation surgery it was significantly shorter and the median survival in this group was 15 months (95% CI, 0-31) [

18].

This disparity highlights the challenges faced by patients requiring long-term ECMO support prior to transplantation (as a bridge to transplant), who often experience exacerbations of underly- ing disease, secondary organ failure, or severe pulmonary hypertension. Despite these challenges, BTT remains a key strategy in saving patients who have no other therapeutic options, offering a chance of survival in scenarios that would otherwise be fatal [

34]. The literature comparing ECMO bridge with mechanical ventilation indicates that ECMO provides better survival before and after transplantation, probably due to less lung damage to the patient awaiting LTx, better gas exchange, and preservation of diaphragmatic function, which will be critically needed for proper rehabilitation immediately after LTx [

34].

4.7. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) and ECMO

Patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (iPAH) undergoing lung transplantation are among the most difficult to treat perioperatively due to severe right ventricular dysfunction and, as reported by many scientific teams, potential postoperative LV failure [

16,

35,

36,

37]. This LV failure is associated with the fact that for the duration of the disease (sometimes even several years) the left ventricle undergoes fibrosis, interestingly due to the low workload/load - (‘preload’) - due to impaired blood flow through the pulmonary vascular bed in the course of pul- monary hypertension [

36,

37,

38]. After lung transplantation with an already low-resistance vascular bed, causes a dramatic increase in left ventricular preload, which has been “accustomed” to low preload for many years. Early survival in this study was 89.5%, and two-year survival was 62.3%, comparable to patients without PAH.

These results were achieved thanks to advanced protocols, including postoperative LV condition- ing, which gradually adapts the left ventricle to the increased preload after transplantation [

19].

Other studies have also highlighted similar challenges in the treatment of patients with iPAH and reported similar outcomes [

18]. The use of VA-ECMO for several days as left ventricular condi- tioning in these cohorts was effective in mitigating described above risks, further supporting its role in the treatment of this high-risk group of patients.

4.8. COVID-19 and Lung Transplantation with ECMO

The COVID-19 pandemic has become an event that has posed new challenges to medicine. It quickly became clear that lung transplantation is the only and final way to save patients with se- vere respiratory failure whose lungs have been completely destroyed, while ECMO has often been the only real bridge to recovery or to transplantation for patients with severe ARDS refracto- ry to conventional treatment [

39,

40,

41].

In our study, early survival in patients affected by COVID-19 after lung transplantation with ECMO was 55.6%, compared to 87.0% in patients undergoing lung transplantation with ECMO but not affected by COVID-19. This discrepancy, in our opinion, reflects the cumulative impact of prolonged critical illness, including multiple organ dysfunction commonly observed in patients with COVID-19. Other centers have reported similar results. For example, early data from centers performing lung transplants in COVID-19 patients showed that survival was poorer in patients with additional comorbidities, such as renal or hepatic dysfunction, compared with patients with isolated respiratory failure.

Better outcomes after lung transplantation were achieved in centers that had a policy of transplan- ting patients with “single organ failure”—in this case, only lung failure [

42,

43,

44]. This un- derscores the importance of careful patient selection and advanced perioperative management strategies. These and other challenges underscore the need for further refinement of transplant procedures and ECMO protocols for this unique patient population.

4.9. Anticoagulation Protocols

Anticoagulation during ECMO therapy requires a careful approach and a balance between throm- boembolic and hemorrhagic risk. Recent advances in ECMO design, including heparin-coated cannulas and low-resistance oxygenators, have facilitated the use of heparin-free protocols in high-risk populations such as patients with prior pleurodesis or bleeding tendencies.

In this study, there was no statistically significant difference in survival, thromboembolic or hem- orrhagic complications between patients treated with or without therapeutic doses of heparin. All patients undergoing ECMO therapy had their coagulation status assessed pre- or post-transplant using aptt and intraoperatively using ACT, and the recommended anticoagulation levels were in the range of 50-60s and 180-220s, respectively.

Our results are consistent with reports from other centers that suggest that individualized antico- agulation protocols can reduce complications mentioned above without compromising outcomes [

45,

46,

47].This approach is particularly important in patients receiving long-term ECMO sup- port (sometimes for many weeks), who are at increased risk for bleeding and thrombotic events.

4.10. Limitations and Future Directions

Our study provides valuable insights into the research area, although its retrospective nature and the heterogeneity of the patient population analyzed make some limitations. For example, small subgroup sizes in advanced ECMO techniques such as SPORT-ECMO limit the statistical power of the analyses and from a statistical point of view one should be careful with these results and especially with their application in daily practice. Authors will certainly undertake further analy- ses after increasing the number of patients treated with ECMO and lung transplantation. The prospective and randomized studies that are already underway will certainly significantly enrich the knowledge on the use of ECMO in lung transplantation.

Future studies should focus on multicenter collaborations to validate these findings and establish standardized ECMO protocols. Also future studies, should include the population of pediatric patients in terms of slightly different circulatory and respiratory physiology.

Moreover, new areas of exploration should include the development of hybrid ECMO configura- tions, miniaturized systems, and extension indications for ECMO in high-risk transplant popula- tions. Continued innovation in perioperative care and multidisciplinary approaches will be essen- tial to further improve lung transplantation outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms the established role of ECMO in modern lung transplantation, demon- strating its versatility in addressing a variety of clinical scenarios, including PAH and COVID-19. This study indicates that despite the challenges associated with high-risk populations ECMO en- ables successful transplantation and survival outcomes comparable to data from leading centers. With continued innovation in ECMO technology and protocols, its potential in lung transplanta- tion will continue to expand, providing hope to the sickest patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.S.; methodology: T.S.; software: T.S.; validation: T.S., M.U, P.P.; formal analysis: T.S., M.U; investigation: T.S., M.U, A.P-L, M.N; resources: T.S.; data curation: T.S.; writing—original draft preparation: T.S.; writing—review and editing: T.S., K.K. P.S, A.M; visualization, T.S.; supervision: T.S., M.U., P.P.; project administration: T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived due to the fact this study was based on retrospectively collected data obtained after the completion of all patient interventions and follow-up. Statistical analyses were performed on a fully anonymized dataset. The local Ethics Committee reviewed the study protocol and confirmed that formal ethical approval was not required BNW/NWN/0052/ KB/209/23.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized dataset supporting the findings of this study is openly avail- able upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. In accordance with institutional and ethical guide- lines, the dataset has been de-identified to ensure patient confidentiality. We fully support the principles of Open Data and transparency in scientific research. Therefore, researchers interested in replicating or expand- ing upon our analyses are welcome to request access to the data, which will be shared in compliance with ethical regulations and applicable data use agreements. For access to the dataset, please contact Dr. Tomasz Stącel at tstacel@tlen.pl

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Julia Kegler and Daniel Cieśla for their work on the graphic editing of the figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARDS |

- acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| BTT |

- Bridge to Transplantation |

| CARDS |

- coronavirus acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| CFV |

- common femoral vein |

| CFA |

- common femoral artery |

| CLAD |

- chronic lung allograft dysfunction |

| COPD |

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CTEPH |

- chronic tromboembolic pulmonary hypertension |

| ECMO |

- extra corporeal membrane oxygenation |

| FA |

- femoral artery |

| IJV |

- internal jugular vein |

| iPAH |

- idiopathic pulmonary hypertension |

| IPF |

- idiopathic fibrosis |

| IQR |

- inter quartile range |

| LTx |

- lung transplantation |

| LuTx |

- lung transplantation |

| LV |

- left ventricule |

| PAH |

- pulmonary artery hypertension |

| PGD |

- primary graft dysfunction |

| PH |

- pulmonary hypertension |

| RV |

- right ventricule |

| SD |

- standard deviation |

| VA |

- veno-arterial |

| VAV |

- veno-arterio-venous |

| VV |

- veno-venous |

References

- Arjuna, M.T. Olson, i R. Walia, „Current trends in candidate selection, contraindications, and indications for lung transplantation”, Journal of Thoracic Disease, t. 13, nr 11, s. 6514, lis. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. C. van der Mark, R. A. S. Hoek, i M. E. Hellemons, „Developments in lung transplantation over the past decade”, European Respirato- ry Review, t. 29, nr 157, s. 1–16, wrz. 2020. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Pervaiz Butt i in., „Enhancing lung transplantation with ECMO: a comprehensive review of mechanisms, outcomes, and future consid- erations”, J Extra Corpor Technol, t. 56, nr 4, s. 191–202, grudz. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D. Brodie, i S. M. Arcasoy, „Extracorporeal Life Support in Lung Transplantation”, Clinics in chest medicine, t. 38, nr 4, s. 655–666, grudz. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. P. Garcia, C. L. J. P. Garcia, C. L. Ashworth, i C. A. Hage, „ECMO in lung transplant: pre, intra and post-operative utilization—a narrative review”, Cur- rent Challenges in Thoracic Surgery, t. 5, nr 0, kwi. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlushkov, M. Berman, i K. Valchanov, „Cannulation techniques for extracorporeal life support”, Ann Transl Med, t. 5, nr 4, s. 70, luty 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Suwalski i in., „Transition from Simple V-V to V-A and Hybrid ECMO Configurations in COVID-19 ARDS”, Membranes, t. 11, nr 6, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Betit, „Technical Advances in the Field of ECMO”, Respiratory care, t. 63, nr 9, s. 1162–1173, wrz. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Hart i M. G. Davies, „Vascular Complications in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation-A Narrative Review”, J Clin Med, t. 13, nr 17, s. 5170, sie. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fisser i in., „Arterial and venous vascular complications in patients requiring peripheral venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxy- genation”, Front Med (Lausanne), t. 9, s. 960716, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pasrija, K. Bedeir, J. Jeudy, i Z. N. Kon, „Harlequin Syndrome during Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation”, Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging, t. 1, nr 2, s. e190031, cze. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. St\c acel i in., „Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation as a Bridge to Lung Transplantation: First Polish Experience”, Transplantation proceedings, t. 52, nr 7, s. 2110–2112, wrz. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Stącel i in., „Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation as a Bridge to Lung Transplantation: First Polish Experience”, Transplant Proc, t. 52, nr 7, s. 2110–2112, wrz. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Otto i in., „Survival and left ventricular dysfunction post lung transplantation for pulmonary arterial hypertension”, J Crit Care, t. 72, s. 154120, grudz. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Verbelen, S. Van Cromphaut, F. Rega, i B. Meyns, „Acute left ventricular failure after bilateral lung transplantation for idiopathic pul- monary arterial hypertension”, J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, t. 145, nr 1, s. e7-9, sty. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Gupta, F. Torres, S. Bollineni, M. Mohanka, i V. Kaza, „Left Ventricular Dysfunction After Lung Transplantation for Pulmonary Arteri- al Hypertension”, Transplant Proc, t. 47, nr 9, s. 2732–2736, lis. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Stącel i in., „Interventional and Surgical Treatments for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension”, J Clin Med, t. 10, nr 15, s. 3326, lip. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Hoetzenecker i in., „Intraoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and the possibility of postoperative prolongation improve survival in bilateral lung transplantation”, J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, t. 155, nr 5, s. 2193-2206.e3, maj 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tudorache i in., „Lung transplantation for severe pulmonary hypertension--awake extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for postoperative left ventricular remodelling”, Transplantation, t. 99, nr 2, s. 451–458, luty 2015. [CrossRef]

- Stącel i in., „Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation as a Postoperative Left Ventricle Conditioning Tool After Lung Transplantation in Patients With Primary Pulmonary Artery Hypertension: First Polish Experience”, Transplant Proc, t. 52, nr 7, s. 2113–2117, wrz. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Ius i in., „Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to lung transplantation may not impact overall mortality risk after trans- plantation: results from a 7-year single-centre experience”, Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, t. 54, nr 2, s. 334–340, sie. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. M. McFadden i C. L. Greene, „The evolution of intraoperative support in lung transplantation: Cardiopulmonary bypass to extracorpo- real membrane oxygenation”, The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, t. 149, nr 4, s. 1158–1160, kwi. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Nazarnia i K. Subramaniam, „Pro: Veno-arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) Should Be Used Routinely for Bilat- eral Lung Transplantation”, Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia, t. 31, nr 4, s. 1505–1508, sie. 2017. [CrossRef]

- [Cypel M, „Extracorporeal lung support for lung transplantation.”, Keshavjee S., s. 467–74, 2013, doi: Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2013;18(5):467-74].

- Bermudez i in., „Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to lung transplant: midterm outcomes”, Ann Thorac Surg, t. 92, nr 4, s. 1226–1231; discussion 1231-1232, paź. 2011. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D. Tobias, i D. Tumin, „Center Volume and Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support at Lung Transplantation in the Lung Allocation Score Era”, Am J Respir Crit Care Med, t. 194, nr 3, s. 317–326, sie. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Fuehner i in., „Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in awake patients as bridge to lung transplantation”, Am J Respir Crit Care Med, t. 185, nr 7, s. 763–768, kwi. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Kearns i O. O. Hernandez, „«Awake» Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation as a Bridge to Lung Transplant”, AACN Adv Crit Care, t. 27, nr 3, s. 293–300, lip. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Javidfar i in., „Subclavian artery cannulation for venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation”, ASAIO J, t. 58, nr 5, s. 494–498, 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Abrams, D. Brodie, E. B. Rosenzweig, K. M. Burkart, C. L. Agerstrand, i M. D. Bacchetta, „Upper-body extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a strategy in decompensated pulmonary arterial hypertension”, Pulm Circ, t. 3, nr 2, s. 432–435, kwi. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Biscotti i M. Bacchetta, „The «sport model»: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation using the subclavian artery”, Ann Thorac Surg, t. 98, nr 4, s. 1487–1489, paź. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Roussel i in., „Arterial vascular complications in peripheral extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: a review of techniques and outcomes”, Future Cardiol, t. 9, nr 4, s. 489–495, lip. 2013. [CrossRef]

- U. Kervan i in., „A Novel Technique of Subclavian Artery Cannulation for Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation”, Exp Clin Transplant, t. 15, nr 6, s. 658–663, grudz. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Faccioli i I. Inci, „Extracorporeal life support as a bridge to lung transplantation: a narrative review”, J Thorac Dis, t. 15, nr 9, s. 5221– 5231, wrz. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Hoeper, „Extracorporeal Life Support in Pulmonary Hypertension: Practical Aspects”, Semin Respir Crit Care Med, t. 44, nr 6, s. 771–776, grudz. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Verbelen, S. Van Cromphaut, F. Rega, i B. Meyns, „Acute left ventricular failure after bilateral lung transplantation for idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension”, J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, t. 145, nr 1, s. e7-9, sty. 2013. [CrossRef]

- E. Manders i in., „Contractile Dysfunction of Left Ventricular Cardiomyocytes in Patients With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension”, Jour- nal of the American College of Cardiology, t. 64, nr 1, s. 28–37, lip. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. L. Hardegree i in., „Impaired left ventricular mechanics in pulmonary arterial hypertension: identification of a cohort at high risk”, Circ Heart Fail, t. 6, nr 4, s. 748–755, lip. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Hunt i in., „(182) Ecmo as a Bridge to Lung Transplantation for Covid-19 Respiratory Failure: Outcomes and Risk Factors for Early Mortality”, The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, t. 42, nr 4, s. S90, kwi. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Schaheen, R. M. Bremner, R. Walia, i M. A. Smith, „Lung transplantation for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): The who, what, where, when, and why”, J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, t. 163, nr 3, s. 865–868, mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Cypel i S. Keshavjee, „When to consider lung transplantation for COVID-19”, Lancet Respir Med, t. 8, nr 10, s. 944–946, paź. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bharat i in., „Lung transplantation for patients with severe COVID-19”, Sci Transl Med, t. 12, nr 574, s. eabe4282, grudz. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lang i in., „Lung transplantation for COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome in a PCR-positive patient”, Lancet Respir Med, t. 8, nr 10, s. 1057–1060, paź. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bharat i in., „Early outcomes after lung transplantation for severe COVID-19: a series of the first consecutive cases from four coun- tries”, Lancet Respir Med, t. 9, nr 5, s. 487–497, maj. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Scaravilli i in., „Heparin-Free Lung Transplantation on Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Bridge”, ASAIO Journal, t. 67, nr 11, s. E191–E197, lis. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Fina i in., „Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation without therapeutic anticoagulation in adults: A systematic review of the current literature”, Int J Artif Organs, t. 43, nr 9, s. 570–578, wrz. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Ruitenbeek i in., „Development of a hypercoagulable status in patients undergoing off-pump lung transplantation despite prolonged conventional coagulation tests”, Am J Respir Crit Care Med, t. 191, nr 2, s. 230–233, sty. 2015. [CrossRef]

Scheme 1.

Illustration of various types of ECMO applications, configurations and nomenclature depending on cannulation topography, patient’s level of consciousness and other clinical factors. VV veno-venous; VA - veno-arterial; VAV - veno-arterio-venous; PGD - primary graft dysfunction; LV - left ventricule; RV - right ventricule; PAH - pulmonary artery hypertension; IJV - inter- nal jugular vein; CFV - common femoral vein; CFA - common femoral vein; FA - femoral artery; LuTx - lung transplantation.

Scheme 1.

Illustration of various types of ECMO applications, configurations and nomenclature depending on cannulation topography, patient’s level of consciousness and other clinical factors. VV veno-venous; VA - veno-arterial; VAV - veno-arterio-venous; PGD - primary graft dysfunction; LV - left ventricule; RV - right ventricule; PAH - pulmonary artery hypertension; IJV - inter- nal jugular vein; CFV - common femoral vein; CFA - common femoral vein; FA - femoral artery; LuTx - lung transplantation.

Figure 1.

The total number of ECMO performed in the years 2018-2023, divided into the number of bridges of patients to LTx (bridge to LTx) and left ventricular conditioning (LV Conditioning), and the number of ECMO-awake, divided into intubated and extubated and sport ECMO.

Figure 1.

The total number of ECMO performed in the years 2018-2023, divided into the number of bridges of patients to LTx (bridge to LTx) and left ventricular conditioning (LV Conditioning), and the number of ECMO-awake, divided into intubated and extubated and sport ECMO.

Figure 2.

Trend in Lung Transplantations with ECMO in years 2018-2023.

Figure 2.

Trend in Lung Transplantations with ECMO in years 2018-2023.

Figure 3.

Trend in Lung Transplantations in Patients with iPAH in 2018-2023 (all with ECMO).

Figure 3.

Trend in Lung Transplantations in Patients with iPAH in 2018-2023 (all with ECMO).

Figure 4.

Increase in LTx with ECMO system in patients with iPAH in years 2018-2023.

Figure 4.

Increase in LTx with ECMO system in patients with iPAH in years 2018-2023.

Figure 5.

ECMO modes in individual years: VV - Veno-venous, VA - Veno-arterial, VAV - Veno-Arterial-Venous with their respective trends.

Figure 5.

ECMO modes in individual years: VV - Veno-venous, VA - Veno-arterial, VAV - Veno-Arterial-Venous with their respective trends.

Figure 6.

A: Early (60-day) and B: long-term (two-year) survival of patients undergoing lung transplantation with ECMO.

Figure 6.

A: Early (60-day) and B: long-term (two-year) survival of patients undergoing lung transplantation with ECMO.

Figure 7.

Kaplan-Meir survival analysis. A: Early (60-day) survival and B: long term (two- year) survival depending on the ECMO mode: VA-ECMO vs. VV-ECMO.

Figure 7.

Kaplan-Meir survival analysis. A: Early (60-day) survival and B: long term (two- year) survival depending on the ECMO mode: VA-ECMO vs. VV-ECMO.

Figure 8.

Comparison of early (60-day) (A) and long term (two-year) (B) survival of pa- tients bridged to LTx on ECMO vs. those who were not-bridged on ECMO but with usage of ECMO on other stages of LTx.

Figure 8.

Comparison of early (60-day) (A) and long term (two-year) (B) survival of pa- tients bridged to LTx on ECMO vs. those who were not-bridged on ECMO but with usage of ECMO on other stages of LTx.

Figure 9.

A: early (60-day) survival, B: long term (24-months) survival in patients with/without PAH in which LTx was performed with ECMO.

Figure 9.

A: early (60-day) survival, B: long term (24-months) survival in patients with/without PAH in which LTx was performed with ECMO.

Figure 10.

A: Early (60-day) and long term (2-year) survival in patients supported with and without SPORT-ECMO Technique.

Figure 10.

A: Early (60-day) and long term (2-year) survival in patients supported with and without SPORT-ECMO Technique.

Figure 11.

Analysis of Covid-19 patients bridged on VV-ECMO and transplanted at our Centre. Note: Only the 9 patients transplanted at our Centre were included in the analysis - the remaining patients (n=57) were bridged with VV-ECMO at collaborating ICUs but did not un- dergo LTx at our Centre.

Figure 11.

Analysis of Covid-19 patients bridged on VV-ECMO and transplanted at our Centre. Note: Only the 9 patients transplanted at our Centre were included in the analysis - the remaining patients (n=57) were bridged with VV-ECMO at collaborating ICUs but did not un- dergo LTx at our Centre.

Figure 12.

A: Early survival (60-day) and B: late survival (two-year) of patients with or without COVID-19 undergoing LTx with ECMO.

Figure 12.

A: Early survival (60-day) and B: late survival (two-year) of patients with or without COVID-19 undergoing LTx with ECMO.

Figure 13.

Early (A) and long-term (B) survival of patients undergoing lung transplantation with ECMO depending on heparin administration or not.

Figure 13.

Early (A) and long-term (B) survival of patients undergoing lung transplantation with ECMO depending on heparin administration or not.

Table 1.

Types and frequency of diseases due to which patients underwent lung transplanta- tion using the ECMO system; COPD - chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTEPH - chronic tromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; IPAH - idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension.

Table 1.

Types and frequency of diseases due to which patients underwent lung transplanta- tion using the ECMO system; COPD - chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTEPH - chronic tromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; IPAH - idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension.

| statistical varia- |

|

n |

% |

95% CI |

| Disease (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

IPAH |

19 |

33,90% |

21,50% |

46,30% |

| |

COVID-19 |

9 |

16,10% |

6,47% |

25,73% |

| |

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis |

8 |

14,30% |

5,13% |

23,47% |

| |

CYSTIC FIBROSIS |

4 |

7,10% |

0,37% |

13,83% |

| |

RETRANSPLANTATION |

4 |

7,10% |

0,37% |

13,83% |

| |

RESCUE |

4 |

7,10% |

0,37% |

13,83% |

| |

CTEPH |

1 |

1,80% |

0,00% |

5,28% |

| |

COPD |

1 |

1,80% |

0,00% |

5,28% |

| |

EMPHYSEMA |

1 |

1,80% |

0,00% |

5,28% |

| |

SILICOLOSIS |

1 |

1,80% |

0,00% |

5,28% |

| |

LANGERHANS CELL HISTIOCTY- |

1 |

1,80% |

0,00% |

5,28% |

| |

SARKOIDOSIS |

1 |

1,80% |

0,00% |

5,28% |

| |

MUNIER-KHUN SYNDROME |

1 |

1,80% |

0,00% |

5,28% |

| |

RENDU-OSLER-WEBER SYN- |

1 |

1,80% |

0,00% |

5,28% |

Table 2.

Qualititative data: Populational and anthropological characteristics of the patients.

Table 2.

Qualititative data: Populational and anthropological characteristics of the patients.

| Variabe |

n |

|

95% CI |

| Female |

27 |

48,20% |

35,11% |

61,29% |

| Men |

29 |

51,80% |

38,71% |

64,89% |

| Hypertension |

6 |

10,90% |

2,74% |

19,06% |

| Osteoporosis |

2 |

3,60% |

0,00% |

8,48% |

| Renal insuficiency |

4 |

7,10% |

0,37% |

13,83% |

| Mechanical Ventilation before ECMO |

7 |

16,30% |

6,63% |

25,97% |

| Diabetes |

3 |

5,40% |

0,00% |

11,32% |

| Neurological complications before ECMO |

3 |

5,40% |

0,00% |

11,32% |

Table 3.

Quantitative data. Population and anthropological characteristics of patients.

Table 3.

Quantitative data. Population and anthropological characteristics of patients.

| Variable |

n |

min |

max |

median |

q1 |

q3 |

mean |

SD |

| Body mass (kg) |

50 |

20,5 |

102 |

62,2 |

54 |

73,5 |

63,4 |

17,1 |

| Hight (cm) |

50 |

130 |

197 |

168 |

162 |

176 |

169 |

10,7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

49 |

12 |

33,2 |

21,8 |

19,5 |

24,9 |

21,9 |

4,67 |

| Ecmo total time (hours) |

56 |

2 |

2166 |

66,2 |

7,05 |

266 |

232 |

398 |

Hospitalization

time after decannulation (day) |

55 |

0 |

140 |

29 |

21,5 |

41,5 |

34 |

26,6 |

| Bridge to transplant time (day) |

15 |

2 |

90 |

19 |

15,5 |

28 |

24,7 |

20,8 |

| LV conditioning time (day) |

13 |

0 |

45 |

4 |

3 |

7 |

10,3 |

15,1 |

Table 4.

Mortality rate and frequency of complications in patients undergoing lung trans- plantation using the ECMO system.

Table 4.

Mortality rate and frequency of complications in patients undergoing lung trans- plantation using the ECMO system.

| Variabe |

n |

% |

95% CI |

| Death during ECMO run |

10 |

17,90% |

7,86% |

27,94% |

| 30-day mortality |

7 |

12,50% |

3,84% |

21,16% |

| Cannulation site complications |

3 |

5,40% |

0,00% |

11,32% |

| Neurological complications |

5 |

8,90% |

1,44% |

16,36% |

| Hemorrhagic complications |

12 |

21,40% |

10,66% |

32,14% |

Table 5.

Type and frequency of complications depending on the use or not of additional doses of heparin.

Table 5.

Type and frequency of complications depending on the use or not of additional doses of heparin.

| |

Additional Heparin after ECMO initiation |

| |

No Yes

|

| |

n |

% |

n |

% |

p |

| sex (male) |

15 |

53,6 |

14 |

50,0 |

0,999 |

| neurological complications |

2 |

7,1 |

3 |

10,7 |

0,999 |

| cardiological complications |

5 |

17,9 |

4 |

14,3 |

0,999 |

| hemorrhagic complications |

4 |

14,3 |

8 |

28,6 |

0,329 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).