Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

27 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

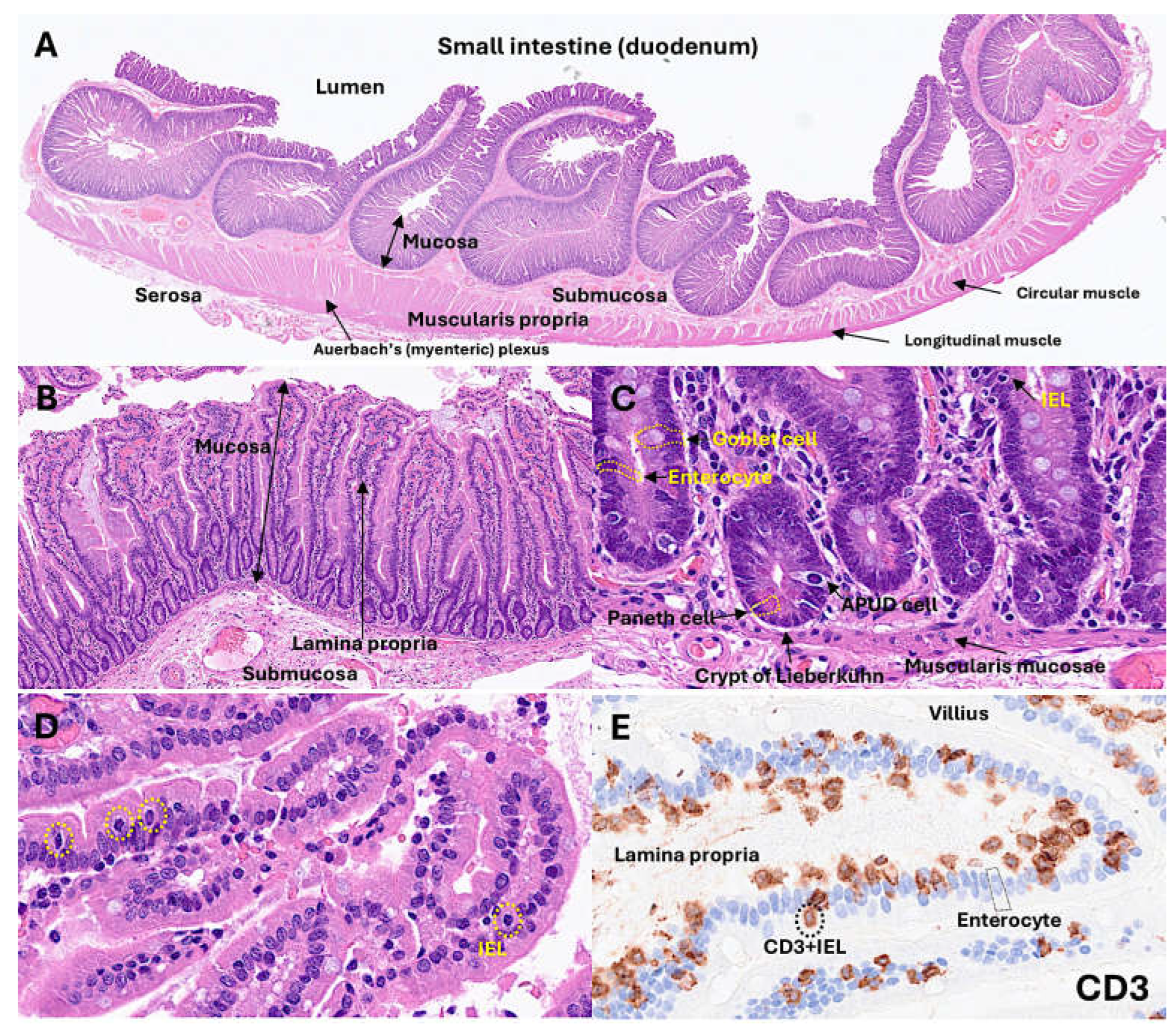

1.1. Histology of the Small Intestine

1.2. Instraepithelial Lymphocytes

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

- IELs are stratified into natural IELs (nIELs) and peripherally induced IELs (pIELs) [55,56,57,58]. The nIELs are generated in the thymus and migrate to the intestine. In contrast, pIELs are derived from CD4-positive or CD8-positive T cells at inductive sites, such as gut-associated lymph nodes, in response to dietary and microbial antigens [31,37,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

- (7)

- IELs can be further subclassified according to their TCR subtype: (I) TCRγδ+ nIELs (tissue surveillance and repair), (II) TCRαβ+CD8αα+ nIELs (regulation), (III) TCRαβ+CD8αβ+ pIELs (effector memory, cytotoxicity), (IV) TCRαβ+CD4+ pIELs (regulation, cytotoxicity) [31,37]. Subtypes I and II may recognize self-antigens using their TCR, are present at birth, and are microbiota independent. On the other hand, subtypes III and IV may recognize microbial, viral, and dietary antigens using the TCRs, are absent at birth, increase with age, and are microbiota- and diet-dependent [31,37]. Of note, CD4+FOXP3+regulatory T lymphocytes (Tregs) can undergo CD4+CD8αα+ IEL differentiation in the intestinal epithelium [62,63].

- (8)

- CD8αα+ is an indication of intestinal IELs. Conventional CD8+ T cells express the CD8αβ heterodimer that is a TCR coreceptor, and enhance the TCR-MHC-I interactions during antigen presentation. Most IELs express CD8αα homodimer that decreases TCR sensitivity and prevents IEL hyperactivation via the mechanism of CD8αα homodimer interaction with thymus leukemia (TL) antigen [64], which is expressed by intestinal epithelial cells. Therefore, TL expression plays a critical role in maintaining IEL effector functions. TL deficiency is associated with colitis in a genetic model of inflammatory bowel disease [65].

- (9)

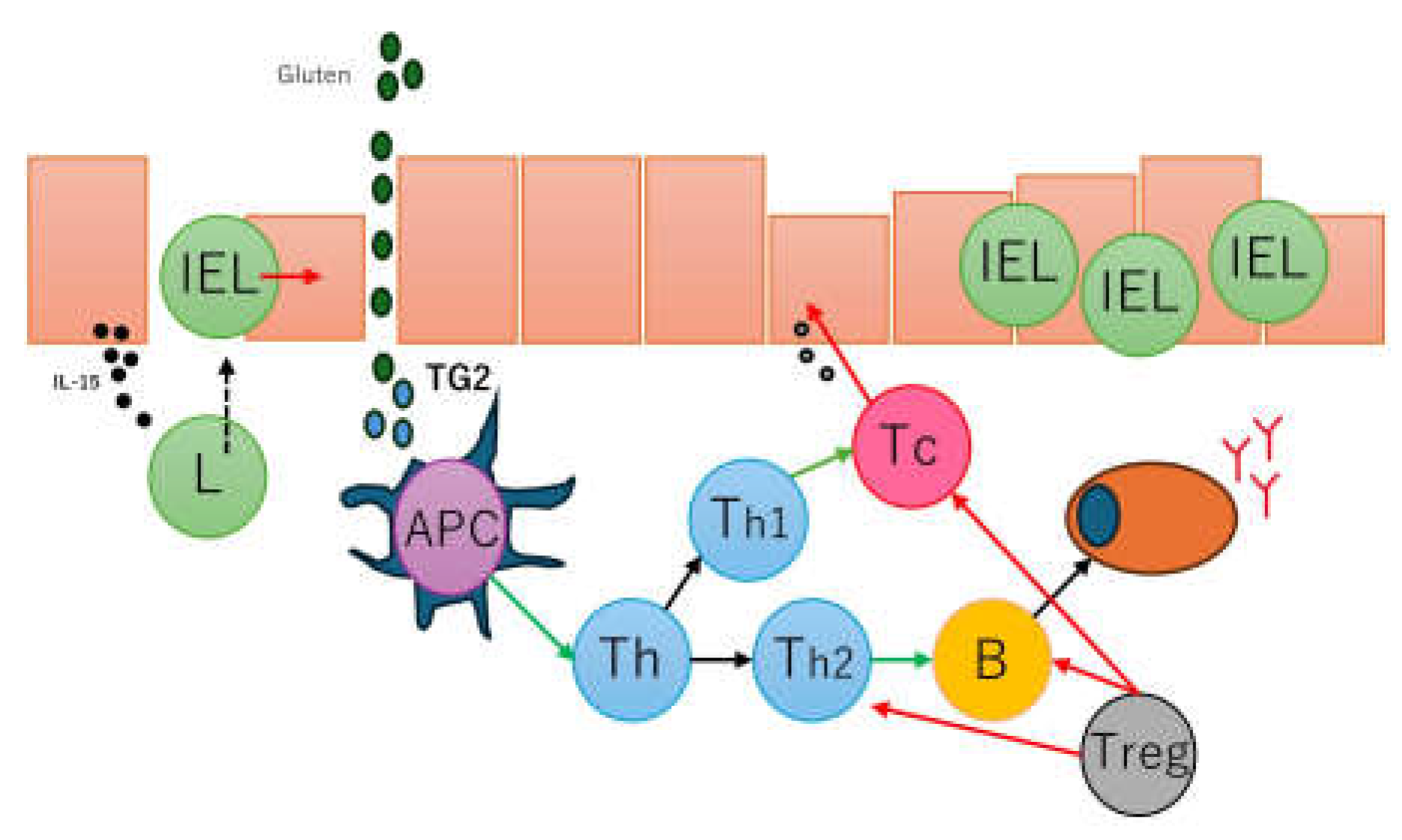

- IELs contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic intestinal inflammatory disease. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. Dysregulated intestinal immune response to microbiota is a cause of IBD [66,67]. In IBD, IELs could play a regulatory role [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. A preserved villous architecture and increased IELs characterize microscopic colitis [73,74,75,76]. Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease triggered by dietary gliadin and is characterized by villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and chronic inflammation of the lamina propria [77,78,79,80]. In celiac disease, there are increased CD8αβ+ pIELs and TCRγδ+ nIELs [31]. IELs can undergo neoplastic transformation into Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, a rare complication in patients with celiac disease who are unresponsive to gluten-free diet and treatment [81,82,83,84] (Figure 1).

1.3. Celiac Disease

1.4. LAIR1

1.5. Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Sample

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

2.3. Image Classification

3. Results

3.1. Immunophenotype of Intraepithelial Lymphocytes (IELs) in Intestinal Mucosa Control

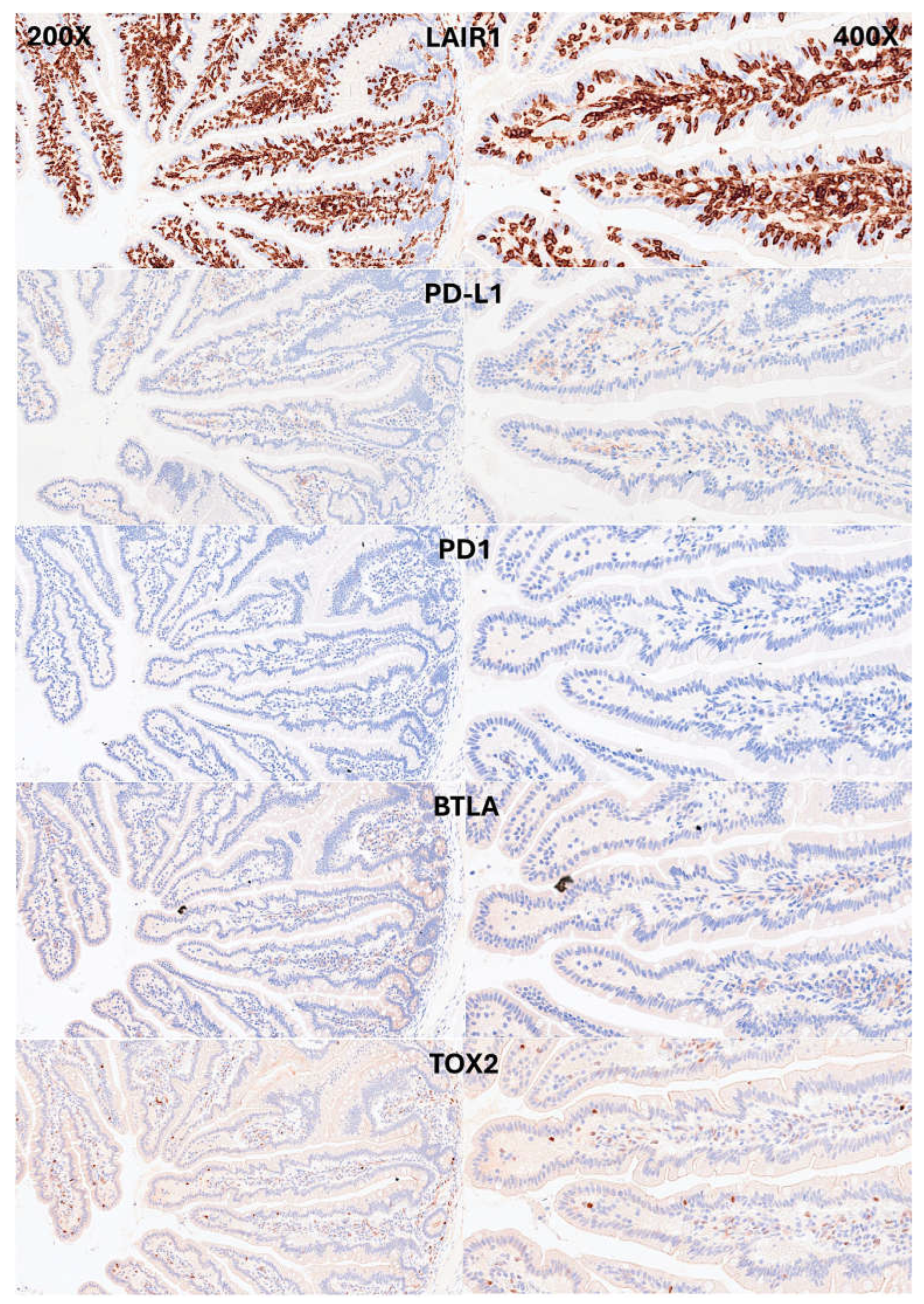

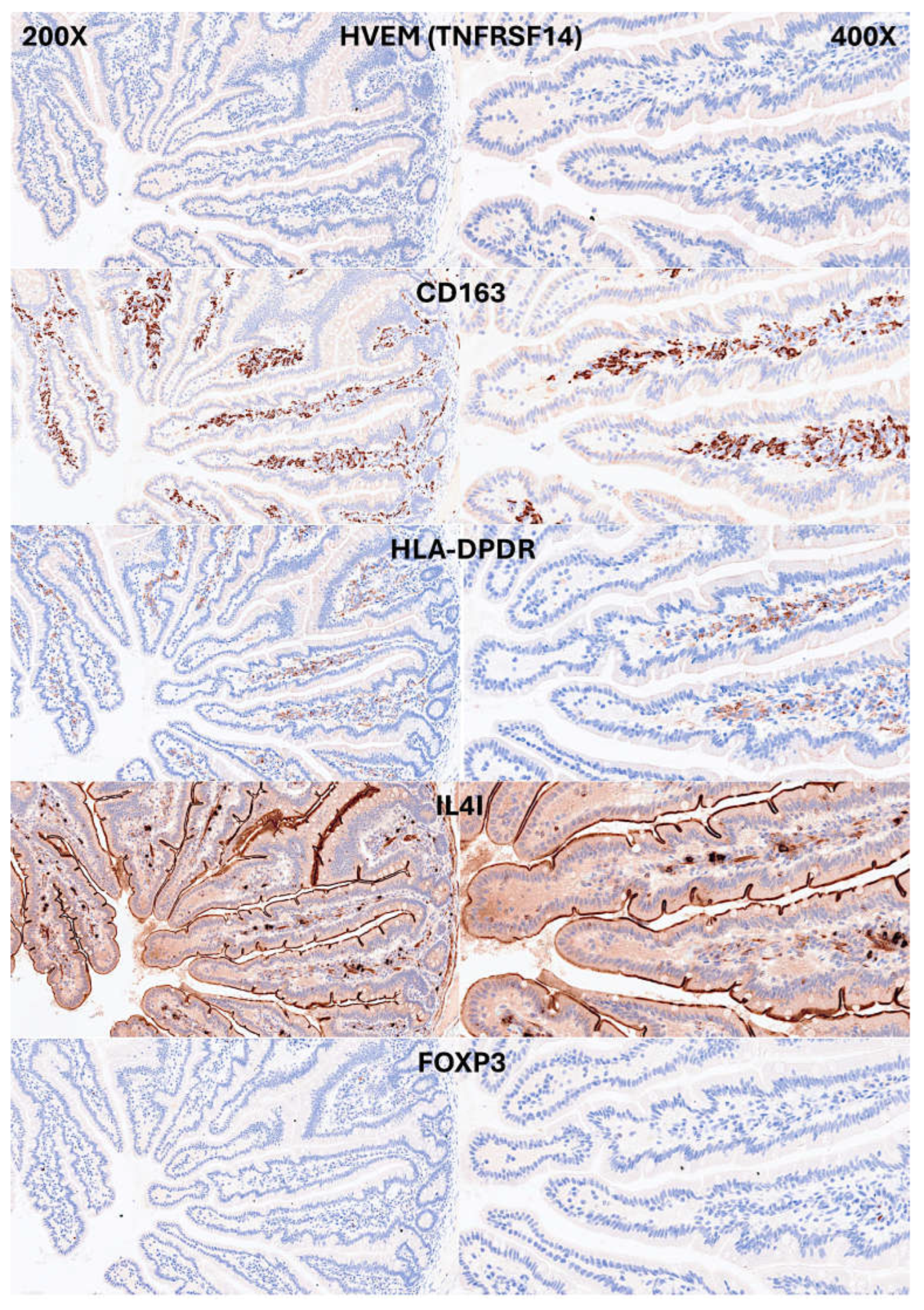

3.2. Multicolor Analysis of LAIR1 and Other Immune Markers

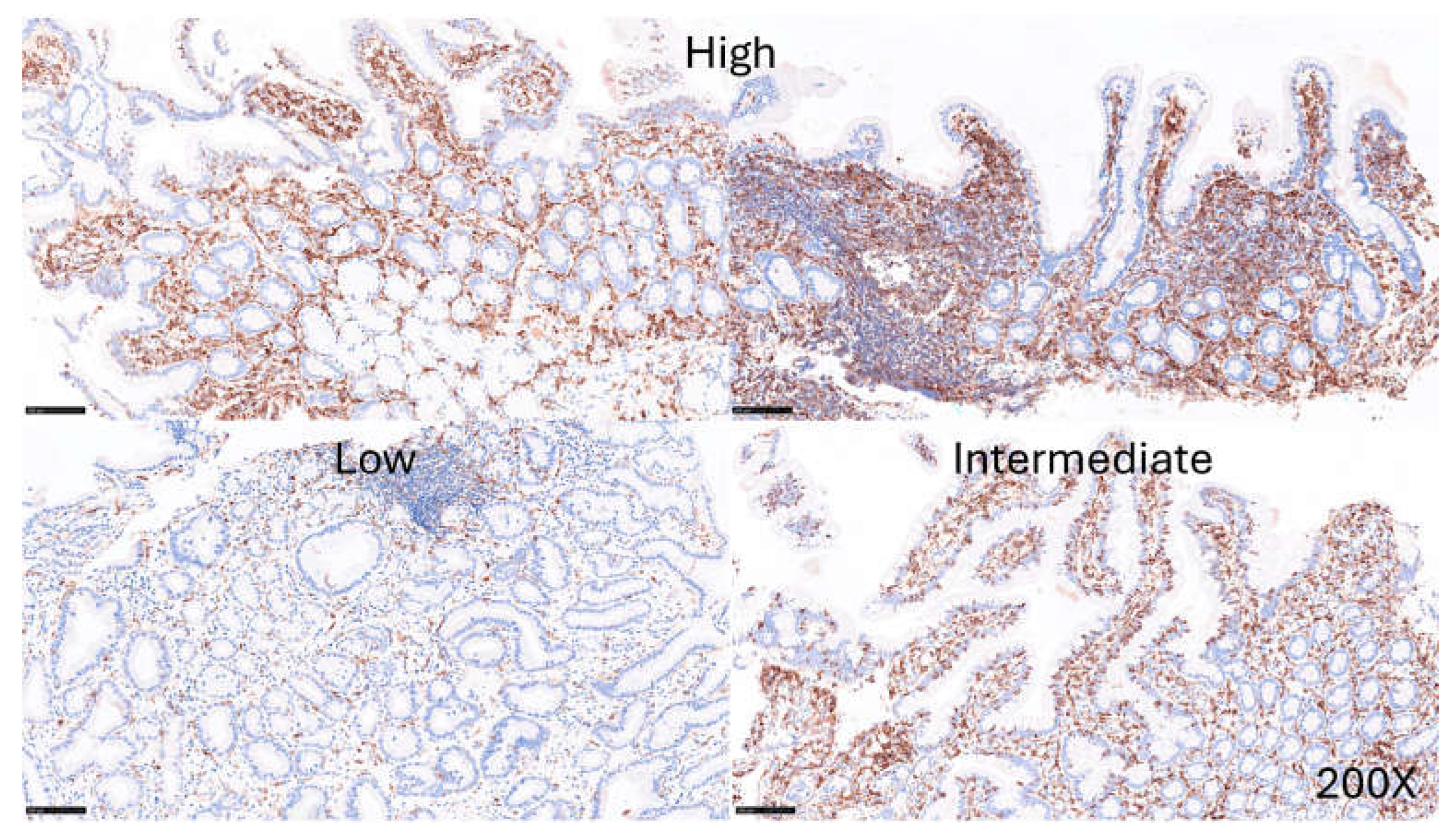

3.3. Analysis of LAIR1 Expression in Celiac Disease

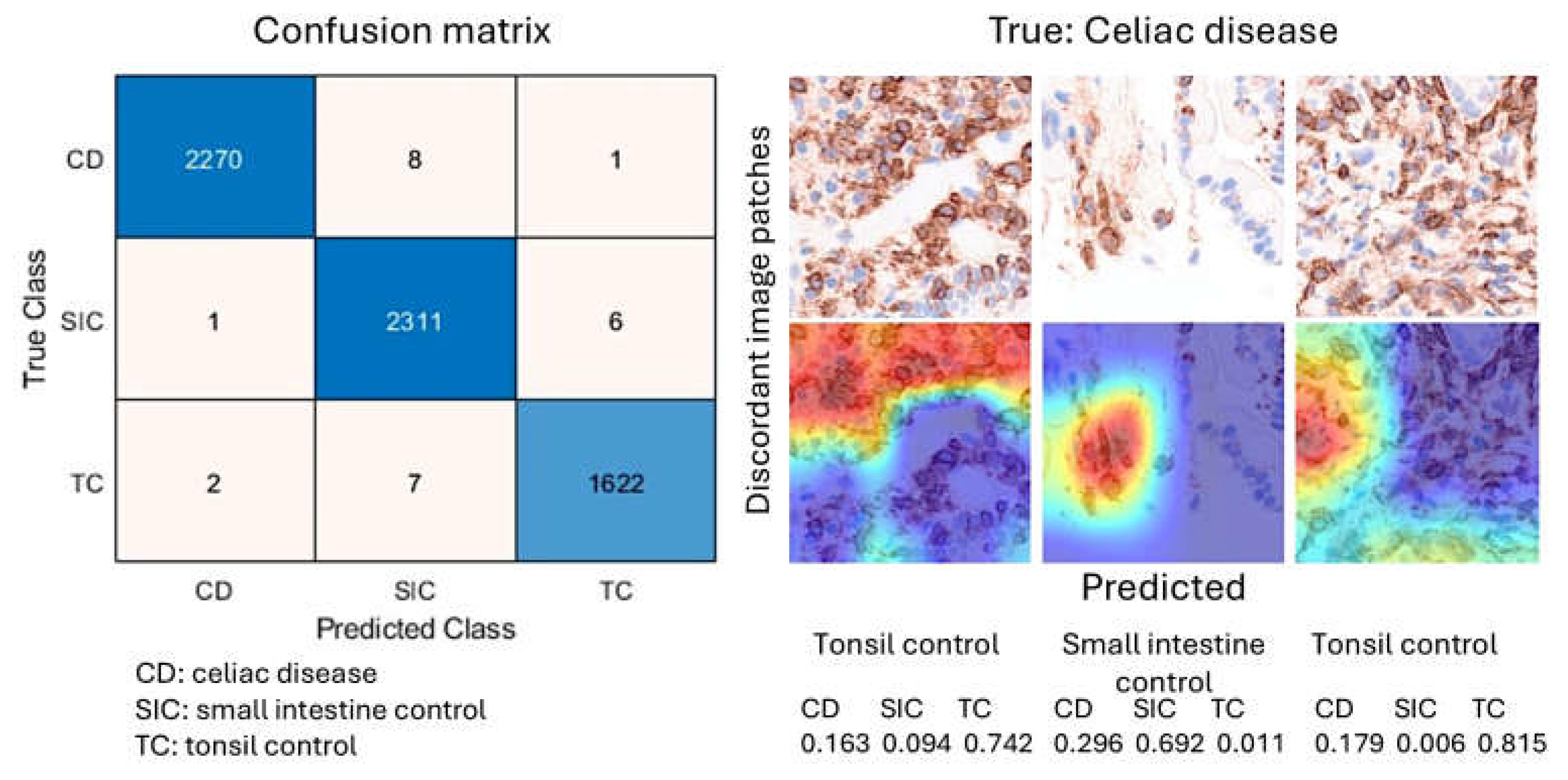

3.4. Image Classification of Celiac Disease, Small Intestine Control, and Reactive Tonsil Control Based on LAIR1 Immunohistochemical Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IELs | Intraepithelial lymphocytes |

| EATL | Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma |

| LAIR1 | Leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin like receptor 1 |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1.

| Age | Sex | Biopsy Location | Diagnosis | Marsh-Oberhuber Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70 | Male | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3a |

| 62 | Male | Pylorus/duodenum | Celiac Disease/Chronic gastritis | 2 |

| 62 | Male | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 2 |

| 78 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3b |

| 59 | Male | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3a |

| 44 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 2 |

| 17 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3b |

| 56 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3a |

| 54 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 2 |

| 58 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3b |

| 61 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3c |

| 45 | Male | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3a |

| 70 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 2 |

| 40 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3a |

| 61 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3c |

| 44 | Female | Duodenum | Celiac Disease | 3a |

References

- Kong, S.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, W. Regulation of Intestinal Epithelial Cells Properties and Functions by Amino Acids. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018, 2819154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Shen, J. The roles and functions of Paneth cells in Crohn’s disease: A critical review. Cell Prolif 2021, 54, e12958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, J.K.; Johansson, M.E.V. The role of goblet cells and mucus in intestinal homeostasis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 19, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanga, R.; Singh, V.; In, J.G. Intestinal Enteroendocrine Cells: Present and Future Druggable Targets. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanova, M.; Kohout, P. Serotonin-Its Synthesis and Roles in the Healthy and the Critically Ill. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pithadia, A.B.; Jain, S.M. 5-Hydroxytryptamine Receptor Subtypes and their Modulators with Therapeutic Potentials. J Clin Med Res 2009, 1, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajib, M.S.; Khan, W.I. The role of serotonin and its receptors in activation of immune responses and inflammation. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015, 213, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Application of Glucagon-like Peptide-1. Cell Metab 2018, 27, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinci, L.; Faussone-Pellegrini, M.S.; Rotondo, A.; Mule, F.; Vannucchi, M.G. GLP-2 receptor expression in excitatory and inhibitory enteric neurons and its role in mouse duodenum contractility. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011, 23, e383–e392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Chang, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Chan, L. GLP-2 receptor in POMC neurons suppresses feeding behavior and gastric motility. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2012, 303, E853–E864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, H.A.; Fyfe, M.C.; Reynet, C. GPR119, a novel G protein-coupled receptor target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Br J Pharmacol 2008, 153 Suppl 1, S76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Lopez de Maturana, R.; Brenneman, R.; Walent, T.; Mattson, M.P.; Maudsley, S. Class II G protein-coupled receptors and their ligands in neuronal function and protection. Neuromolecular Med 2005, 7, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, J.R.; Laudeman, C. CCK1R agonists: a promising target for the pharmacological treatment of obesity. Curr Top Med Chem 2003, 3, 837–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Katsuma, S.; Adachi, T.; Koshimizu, T.A.; Hirasawa, A.; Tsujimoto, G. Free fatty acids induce cholecystokinin secretion through GPR120. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2008, 377, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulou, M.; Stalla, G.K. Somatostatin receptors: from signaling to clinical practice. Front Neuroendocrinol 2013, 34, 228–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harda, K.; Szabo, Z.; Juhasz, E.; Dezso, B.; Kiss, C.; Schally, A.V.; Halmos, G. Expression of Somatostatin Receptor Subtypes (SSTR-1-SSTR-5) in Pediatric Hematological and Oncological Disorders. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmassmann, A.; Reubi, J.C. Cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptors enhance wound healing in the rat gastric mucosa. J Clin Invest 2000, 106, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L.I. Developmental biology of gastrin and somatostatin cells in the antropyloric mucosa of the stomach. Microsc Res Tech 2000, 48, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Jose, P.A.; Duan, S.; Xu, F.J.; Yang, Z. Intestinal Gastrin/CCKBR (Cholecystokinin B Receptor) Ameliorates Salt-Sensitive Hypertension by Inhibiting Intestinal Na(+)/H(+) Exchanger 3 Activity Through a PKC (Protein Kinase C)-Mediated NHERF1 and NHERF2 Pathway. Hypertension 2022, 79, 1668–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yan, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, K.; Cai, W. Neurotensin contributes to pediatric intestinal failure-associated liver disease via regulating intestinal bile acids uptake. EBioMedicine 2018, 35, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, J.; Yan, B.; Weiss, H.L.; Weiss, L.T.; Gao, T.; Evers, B.M. Neurotensin differentially regulates bile acid metabolism and intestinal FXR-bile acid transporter axis in response to nutrient abundance. FASEB J 2021, 35, e21371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, E.; Matsuura, B.; Dong, M.; Miller, L.J.; Matsui, H.; Onji, M. Molecular characterization and distribution of motilin family receptors in the human gastrointestinal tract. J Gastroenterol 2006, 41, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedzybrodzka, E.L.; Foreman, R.E.; Lu, V.B.; George, A.L.; Smith, C.A.; Larraufie, P.; Kay, R.G.; Goldspink, D.A.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Stimulation of motilin secretion by bile, free fatty acids, and acidification in human duodenal organoids. Mol Metab 2021, 54, 101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modvig, I.M.; Andersen, D.B.; Grunddal, K.V.; Kuhre, R.E.; Martinussen, C.; Christiansen, C.B.; Orskov, C.; Larraufie, P.; Kay, R.G.; Reimann, F.; et al. Secretin release after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass reveals a population of glucose-sensitive S cells in distal small intestine. Int J Obes (Lond) 2020, 44, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuhara, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Kusakizako, T.; Iida, W.; Kato, M.; Shihoya, W.; Nureki, O. Structure of the human secretin receptor coupled to an engineered heterotrimeric G protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2020, 533, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulis, M.; Flavell, R.A. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts of the intestinal lamina propria in physiology and disease. Differentiation 2016, 92, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, K.; Kamikawa, Y. Muscularis mucosae - the forgotten sibling. J Smooth Muscle Res 2007, 43, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Peng, H.; Sun, L.; Tong, J.; Cui, C.; Bai, Z.; Yan, J.; Qin, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. The application of small intestinal submucosa in tissue regeneration. Mater Today Bio 2024, 26, 101032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Yu, W.; Wallace, L.; Sigalet, D. Intestinal muscularis propria increases in thickness with corrected gestational age and is focally attenuated in patients with isolated intestinal perforations. J Pediatr Surg 2014, 49, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beagley, K.W.; Husband, A.J. Intraepithelial lymphocytes: origins, distribution, and function. Crit Rev Immunol 1998, 18, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayassi, T.; Jabri, B. Human intraepithelial lymphocytes. Mucosal Immunol 2018, 11, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Matsuzaki, G.; Kenai, H.; Nakamura, T.; Nomoto, K. Thymus influences the development of extrathymically derived intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol 1993, 23, 1968–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, G.; Lin, T.; Nomoto, K. Differentiation and function of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Int Rev Immunol 1994, 11, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Matsuzaki, G.; Kenai, H.; Kishihara, K.; Nabeshima, S.; Fung-Leung, W.P.; Mak, T.W.; Nomoto, K. Characteristics of fetal thymus-derived T cell receptor gamma delta intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol 1994, 24, 1792–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejdosiewicz, L.K. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes and lymphoepithelial interactions in the human gastrointestinal mucosa. Immunol Lett 1992, 32, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamerman, J.A.; Page, S.T.; Pullen, A.M. Distinct methylation states of the CD8 beta gene in peripheral T cells and intraepithelial lymphocytes. J Immunol 1997, 159, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart, A.; Mucida, D.; Bilate, A.M. Intraepithelial Lymphocytes of the Intestine. Annu Rev Immunol 2024, 42, 289–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, R.; Nemoto, Y.; Yonemoto, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Takei, Y.; Oshima, S.; Nagaishi, T.; Tsuchiya, K.; Nozaki, K.; Mizutani, T.; et al. Intraepithelial Lymphocytes Suppress Intestinal Tumor Growth by Cell-to-Cell Contact via CD103/E-Cadherin Signal. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 11, 1483–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, C.; Finke, J.; Hasselblatt, P.; Kreisel, W.; Schmitt-Graeff, A. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenge of unclassifiable enteropathies with increased intraepithelial CD103(+) CD8(+) T lymphocytes: a single center case series. Scand J Gastroenterol 2021, 56, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, S.B.; Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Lessin, S.R. The role of alpha E beta 7 integrin (CD103) and E-cadherin in epidermotropism in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol 1996, 23, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Bergsbaken, T.; Edelblum, K.L. The multifunctional nature of CD103 (alphaEbeta7 integrin) signaling in tissue-resident lymphocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2022, 323, C1161–C1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yomogida, K.; Trsan, T.; Sudan, R.; Rodrigues, P.F.; Ulezko Antonova, A.; Ingle, H.; Luccia, B.D.; Collins, P.L.; Cella, M.; Gilfillan, S.; et al. The transcription factor Aiolos restrains the activation of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Nat Immunol 2024, 25, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabri, B.; de Serre, N.P.; Cellier, C.; Evans, K.; Gache, C.; Carvalho, C.; Mougenot, J.F.; Allez, M.; Jian, R.; Desreumaux, P.; et al. Selective expansion of intraepithelial lymphocytes expressing the HLA-E-specific natural killer receptor CD94 in celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2000, 118, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melandri, D.; Zlatareva, I.; Chaleil, R.A.G.; Dart, R.J.; Chancellor, A.; Nussbaumer, O.; Polyakova, O.; Roberts, N.A.; Wesch, D.; Kabelitz, D.; et al. The gammadeltaTCR combines innate immunity with adaptive immunity by utilizing spatially distinct regions for agonist selection and antigen responsiveness. Nat Immunol 2018, 19, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, M.; Lewis, J.M.; Filler, R.B.; Hayday, A.C.; Tigelaar, R.E. Environmentally responsive and reversible regulation of epidermal barrier function by gammadelta T cells. J Invest Dermatol 2006, 126, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakandakari-Higa, S.; Canesso, M.C.C.; Walker, S.; Chudnovskiy, A.; Jacobsen, J.T.; Bilanovic, J.; Parigi, S.M.; Fiedorczuk, K.; Fuchs, E.; Bilate, A.M.; et al. Universal recording of cell-cell contacts in vivo for interaction-based transcriptomics. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariss, F.; Delbeke, M.; Guyot, K.; Zarnitzky, P.; Ezzedine, M.; Certad, G.; Meresse, B. Cytotoxic innate intraepithelial lymphocytes control early stages of Cryptosporidium infection. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1229406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, H. CD4CD8alphaalpha IELs: They Have Something to Say. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakou, M.H.; Ghilas, S.; Tran, K.; Liao, Y.; Afshar-Sterle, S.; Kumari, A.; Schmid, K.; Dijkstra, C.; Inguanti, C.; Ostrouska, S.; et al. TCF-1 limits intraepithelial lymphocyte antitumor immunity in colorectal carcinoma. Sci Immunol 2023, 8, eadf2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornberg, A.; Botella, T.; Moon, C.S.; Rao, S.; Gelbs, J.; Cheng, L.; Miller, J.; Bacarella, A.M.; Garcia-Vilas, J.A.; Vargas, J.; et al. Gluten induces rapid reprogramming of natural memory alphabeta and gammadelta intraepithelial T cells to induce cytotoxicity in celiac disease. Sci Immunol 2023, 8, eadf4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G.J.; Nagler-Anderson, C.; Anderson, P.; Bhan, A.K. Cytotoxic potential of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs). Presence of TIA-1, the cytolytic granule-associated protein, in human IELs in normal and diseased intestine. Am J Pathol 1993, 143, 350–354. [Google Scholar]

- Abadie, V.; Discepolo, V.; Jabri, B. Intraepithelial lymphocytes in celiac disease immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol 2012, 34, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, H.; Takahashi, I.; Kiyono, H. Mucosal immune network in the gut for the control of infectious diseases. Rev Med Virol 2001, 11, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, L.; Castro, M.; Pardo, J.; Arias, M. Mouse Model of Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer (CAC): Isolation and Characterization of Mucosal-Associated Lymphoid Cells. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1884, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhou, J.; Xu, H.; Han, J.; Zhang, D. Development and function of natural TCR(+) CD8alphaalpha(+) intraepithelial lymphocytes. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1059042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klose, C.S.N.; Hummel, J.F.; Faller, L.; d’Hargues, Y.; Ebert, K.; Tanriver, Y. A committed postselection precursor to natural TCRalphabeta(+) intraepithelial lymphocytes. Mucosal Immunol 2018, 11, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, Y.; Sujino, T.; Miyamoto, K.; Nomura, E.; Yoshimatsu, Y.; Tanemoto, S.; Umeda, S.; Ono, K.; Mikami, Y.; Nakamoto, N.; et al. Intracellular metabolic adaptation of intraepithelial CD4(+)CD8alphaalpha(+) T lymphocytes. iScience 2022, 25, 104021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, N.M.; Morissette, A.; Mulvihill, E.E. Immunomodulation and inflammation: Role of GLP-1R and GIPR expressing cells within the gut. Peptides 2024, 176, 171200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canesso, M.C.C.; Lemos, L.; Neves, T.C.; Marim, F.M.; Castro, T.B.R.; Veloso, E.S.; Queiroz, C.P.; Ahn, J.; Santiago, H.C.; Martins, F.S.; et al. The cytosolic sensor STING is required for intestinal homeostasis and control of inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 2018, 11, 820–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xu, C.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Cui, C.; Wei, H.; Peng, J.; Zheng, R. Functional fiber enhances the effect of every-other-day fasting on insulin sensitivity by regulating the gut microecosystem. J Nutr Biochem 2022, 110, 109122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadowaki, A.; Miyake, S.; Saga, R.; Chiba, A.; Mochizuki, H.; Yamamura, T. Gut environment-induced intraepithelial autoreactive CD4(+) T cells suppress central nervous system autoimmunity via LAG-3. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujino, T.; London, M.; Hoytema van Konijnenburg, D.P.; Rendon, T.; Buch, T.; Silva, H.M.; Lafaille, J.J.; Reis, B.S.; Mucida, D. Tissue adaptation of regulatory and intraepithelial CD4(+) T cells controls gut inflammation. Science 2016, 352, 1581–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, M.; Bilate, A.M.; Castro, T.B.R.; Sujino, T.; Mucida, D. Stepwise chromatin and transcriptional acquisition of an intraepithelial lymphocyte program. Nat Immunol 2021, 22, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Villagomez, D.; Van Kaer, L. TL and CD8alphaalpha: Enigmatic partners in mucosal immunity. Immunol Lett 2010, 134, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Villagomez, D.; Mendez-Fernandez, Y.V.; Parekh, V.V.; Lalani, S.; Vincent, T.L.; Cheroutre, H.; Van Kaer, L. Thymus leukemia antigen controls intraepithelial lymphocyte function and inflammatory bowel disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 17931–17936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, R.J.; Podolsky, D.K. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2007, 448, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G.P.; Papadakis, K.A. Mechanisms of Disease: Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Mayo Clin Proc 2019, 94, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.T.; Ma, C.; Panda, S.K.; Trsan, T.; Hodel, M.; Frein, J.; Foster, A.; Sun, S.; Wu, H.T.; Kern, J.; et al. Western diet reduces small intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes via FXR-Interferon pathway. Mucosal Immunol 2024, 17, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougaard, P.; Skov, S.; Pedersen, A.E.; Krych, L.; Nielsen, D.S.; Bahl, M.I.; Christensen, E.G.; Licht, T.R.; Poulsen, S.S.; Metzdorff, S.B.; et al. TL1A regulates TCRgammadelta+ intraepithelial lymphocytes and gut microbial composition. Eur J Immunol 2015, 45, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuquteish, D.; Putra, J. Upper gastrointestinal tract involvement of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: A pathological review. World J Gastroenterol 2019, 25, 1928–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.D.; Edelblum, K.L. Sentinels at the frontline: the role of intraepithelial lymphocytes in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Pharmacol Rep 2017, 3, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E.R.; Shmidt, E.; Oxentenko, A.S.; Enders, F.T.; Smyrk, T.C. Normal villous architecture with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes: a duodenal manifestation of Crohn disease. Am J Clin Pathol 2015, 143, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hemert, S.; Skonieczna-Zydecka, K.; Loniewski, I.; Szredzki, P.; Marlicz, W. Microscopic colitis-microbiome, barrier function and associated diseases. Ann Transl Med 2018, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miehlke, S.; Verhaegh, B.; Tontini, G.E.; Madisch, A.; Langner, C.; Munch, A. Microscopic colitis: pathophysiology and clinical management. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 4, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Wu, T.T.; Zhang, L. Microscopic colitis: lymphocytic colitis, collagenous colitis, and beyond. Hum Pathol 2023, 132, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K.E.; D’Amato, M.; Ng, S.C.; Pardi, D.S.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Khalili, H. Microscopic colitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, J. Artificial Intelligence Analysis of Celiac Disease Using an Autoimmune Discovery Transcriptomic Panel Highlighted Pathogenic Genes including BTLA. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, J. Celiac Disease Deep Learning Image Classification Using Convolutional Neural Networks. J Imaging 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catassi, C.; Verdu, E.F.; Bai, J.C.; Lionetti, E. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2413–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanacci, V.; Vanoli, A.; Leoncini, G.; Arpa, G.; Salviato, T.; Bonetti, L.R.; Baronchelli, C.; Saragoni, L.; Parente, P. Celiac disease: histology-differential diagnosis-complications. A practical approach. Pathologica 2020, 112, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Somali, Z.; Hamadani, M.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.; Sureda, A.; El Fakih, R.; Aljurf, M. Enteropathy-Associated T cell Lymphoma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2021, 16, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, E.; Craig, J.W.; Kalac, M. Current and upcoming treatment approaches to uncommon subtypes of PTCL (EATL, MEITL, SPTCL, and HSTCL). Blood 2024, 144, 1898–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.A.A.; Goa, P.; Vandenberghe, E.; Flavin, R. Update on the Pathogenesis of Enteropathy-Associated T-Cell Lymphoma. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Brais, R.; Lavergne-Slove, A.; Jeng, Q.; Payne, K.; Ye, H.; Liu, Z.; Carreras, J.; Huang, Y.; Bacon, C.M.; et al. Continual monitoring of intraepithelial lymphocyte immunophenotype and clonality is more important than snapshot analysis in the surveillance of refractory coeliac disease. Gut 2010, 59, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebwohl, B.; Rubio-Tapia, A. Epidemiology, Presentation, and Diagnosis of Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, J.X.; Saavalainen, P.; Kurppa, K.; Laurikka, P.; Huhtala, H.; Nykter, M.; LEKoskinen, L.; Yohannes, D.A.; Kilpeläinen, E.; Shcherban, A.; Palotie, A. Independent and cumulative coeliac disease-susceptibility loci are associated with distinct disease phenotypes. J Hum Genet 2021, 66, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Lee, H.S.; Aronsson, C.A.; Hagopian, W.A.; Koletzko, S.; Rewers, M.J.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Bingley, P.J.; Bonifacio, E.; Simell, V.; et al. Risk of pediatric celiac disease according to HLA haplotype and country. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, C.; Ahn, R.; Ding, Y.C.; Steele, L.; Stoven, S.; Green, P.H.; Fasano, A.; Murray, J.A.; Neuhausen, S.L. Genome-wide association study of celiac disease in North America confirms FRMD4B as new celiac locus. PLoS One 2014, 9, e101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragde, H.; Jansson, U.; Jarlsfelt, I.; Soderman, J. Gene expression profiling of duodenal biopsies discriminates celiac disease mucosa from normal mucosa. Pediatr Res 2011, 69, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Yao, J.; Lebwohl, B.; Green, P.H.R.; Yuan, S.; Leffler, D.A. Coeliac disease: complications and comorbidities. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Molberg, O.; Parrot, I.; Hausch, F.; Filiz, F.; Gray, G.M.; Sollid, L.M.; Khosla, C. Structural basis for gluten intolerance in celiac sprue. Science 2002, 297, 2275–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakly, W.; Thomas, V.; Quash, G.; El Alaoui, S. A role for tissue transglutaminase in alpha-gliadin peptide cytotoxicity. Clin Exp Immunol 2006, 146, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, G.; Hernell, O.; Melgar, S.; Israelsson, A.; Hammarstrom, S.; Hammarstrom, M.L. Paradoxical coexpression of proinflammatory and down-regulatory cytokines in intestinal T cells in childhood celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggesbo, L.M.; Risnes, L.F.; Neumann, R.S.; Lundin, K.E.A.; Christophersen, A.; Sollid, L.M. Single-cell TCR sequencing of gut intraepithelial gammadelta T cells reveals a vast and diverse repertoire in celiac disease. Mucosal Immunol 2020, 13, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mascarel, A.; Belleannee, G.; Stanislas, S.; Merlio, C.; Parrens, M.; Laharie, D.; Dubus, P.; Merlio, J.P. Mucosal intraepithelial T-lymphocytes in refractory celiac disease: a neoplastic population with a variable CD8 phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol 2008, 32, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderquist, C.R.; Lewis, S.K.; Gru, A.A.; Vlad, G.; Williams, E.S.; Hsiao, S.; Mansukhani, M.M.; Park, D.C.; Bacchi, C.E.; Alobeid, B.; et al. Immunophenotypic Spectrum and Genomic Landscape of Refractory Celiac Disease Type II. Am J Surg Pathol 2021, 45, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caja, S.; Maki, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Lindfors, K. Antibodies in celiac disease: implications beyond diagnostics. Cell Mol Immunol 2011, 8, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Mayassi, T.; Jabri, B. Innate immunity: actuating the gears of celiac disease pathogenesis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2015, 29, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laethem, F.; Donaty, L.; Tchernonog, E.; Lacheretz-Szablewski, V.; Russello, J.; Buthiau, D.; Almeras, M.; Moreaux, J.; Bret, C. LAIR1, an ITIM-Containing Receptor Involved in Immune Disorders and in Hematological Neoplasms. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyaard, L.; Adema, G.J.; Chang, C.; Woollatt, E.; Sutherland, G.R.; Lanier, L.L.; Phillips, J.H. LAIR-1, a novel inhibitory receptor expressed on human mononuclear leukocytes. Immunity 1997, 7, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, J.; Lopez-Guillermo, A.; Kikuti, Y.Y.; Itoh, J.; Masashi, M.; Ikoma, H.; Tomita, S.; Hiraiwa, S.; Hamoudi, R.; Rosenwald, A.; et al. High TNFRSF14 and low BTLA are associated with poor prognosis in Follicular Lymphoma and in Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma transformation. J Clin Exp Hematop 2019, 59, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, J.; Roncador, G.; Hamoudi, R. Ulcerative Colitis, LAIR1 and TOX2 Expression, and Colorectal Cancer Deep Learning Image Classification Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, J.; Roncador, G.; Hamoudi, R. Dataset and AI Workflow for Deep Learning Image Classification of Ulcerative Colitis and Colorectal Cancer. Preprints 2024, 2024121201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingone, F.; Bai, J.C.; Cellier, C.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Celiac Disease-Related Conditions: Who to Test? Gastroenterology 2024, 167, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, Y. Celiac disease in children: A review of the literature. World J Clin Pediatr 2021, 10, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanzamir, N.; Zakeri, Z.; Rostami-Nejad, M.; Sadeghi, A.; Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Shahbakhsh, Y.; Asadzadeh-Aghdaei, H.; Elli, L.; Zali, M.R.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M. Prevalence of celiac disease in patients with atypical presentations. Arab J Gastroenterol 2021, 22, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamut, G.; Soderquist, C.R.; Bhagat, G.; Cerf-Bensussan, N. Advances in Nonresponsive and Refractory Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 2024, 167, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.H.R.; Paski, S.; Ko, C.W.; Rubio-Tapia, A. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Refractory Celiac Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarmozzino, F.; Pizzi, M.; Pelizzaro, F.; Angerilli, V.; Dei Tos, A.P.; Piazza, F.; Savarino, E.V.; Zingone, F.; Fassan, M. Refractory celiac disease and its mimickers: a review on pathogenesis, clinical-pathological features and therapeutic challenges. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1273305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolny, P.; Sigurjonsdottir, H.A.; Remotti, H.; Nilsson, L.A.; Ascher, H.; Tlaskalova-Hogenova, H.; Tuckova, L. Role of immunosuppressive therapy in refractory sprue-like disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999, 94, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, A.; Bolanos, J.; Berkelhammer, C. Azathioprine in refractory sprue. Am J Gastroenterol 1999, 94, 1967–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, G.J.; van Asseldonk, D.P.; van Wanrooij, R.L.; van Bodegraven, A.A.; Mulder, C.J. Tioguanine in the treatment of refractory coeliac disease--a single centre experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012, 36, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurino, E.; Niveloni, S.; Chernavsky, A.; Pedreira, S.; Mazure, R.; Vazquez, H.; Reyes, H.; Fiorini, A.; Smecuol, E.; Cabanne, A.; et al. Azathioprine in refractory sprue: results from a prospective, open-label study. Am J Gastroenterol 2002, 97, 2595–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, S.; Ruiz de Morales, J.M.; Ramos, F.; Suarez-Vilela, D. Alemtuzumab for refractory celiac disease in a patient at risk for enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2006, 354, 2514–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, Y.R.; Shih, A.; Leet, D.; Mooradian, M.J.; Coromilas, A.; Chen, J.; Kem, M.; Zheng, H.; Borowsky, J.; Misdraji, J.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated celiac disease. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omiya, R.; Tsushima, F.; Narazaki, H.; Sakoda, Y.; Kuramasu, A.; Kim, Y.; Xu, H.; Tamura, H.; Zhu, G.; Chen, L.; et al. Leucocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1 is an inhibitory regulator of contact hypersensitivity. Immunology 2009, 128, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, B.M.; Canevali, P.; Magnani, O.; Rossi, E.; Puppo, F.; Zocchi, M.R.; Poggi, A. Defective expression and function of the leukocyte associated Ig-like receptor 1 in B lymphocytes from systemic lupus erythematosus patients. PLoS One 2012, 7, e31903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, L.K.; Winstead, M.; Kee, J.D.; Park, J.J.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Yi, A.K.; Stuart, J.M.; Rosloniec, E.F.; Brand, D.D.; et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 20-Hydroxyvitamin D3 Upregulate LAIR-1 and Attenuate Collagen Induced Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiliopoulou, A.; Iakovliev, A.; Plant, D.; Sutcliffe, M.; Sharma, S.; Cubuk, C.; Lewis, M.; Pitzalis, C.; Barton, A.; McKeigue, P.M. Genome-Wide Aggregated Trans Effects Analysis Identifies Genes Encoding Immune Checkpoints as Core Genes for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, X.; Zhang, M.; Wu, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Liu, S.; Xia, T.; Wang, Y.; et al. Efficient delivery of the lncRNA LEF1-AS1 through the antibody LAIR-1 (CD305)-modified Zn-Adenine targets articular inflammation to enhance the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2023, 25, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agashe, V.V.; Jankowska-Gan, E.; Keller, M.; Sullivan, J.A.; Haynes, L.D.; Kernien, J.F.; Torrealba, J.R.; Roenneburg, D.; Dart, M.; Colonna, M.; et al. Leukocyte-Associated Ig-like Receptor 1 Inhibits T(h)1 Responses but Is Required for Natural and Induced Monocyte-Dependent T(h)17 Responses. J Immunol 2018, 201, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.; Alsaleem, M.A.; Toss, M.S.; Kariri, Y.A.; Althobiti, M.; Alsaeed, S.; Aljohani, A.I.; Narasimha, P.L.; Mongan, N.P.; Green, A.R.; et al. The ITIM-Containing Receptor: Leukocyte-Associated Immunoglobulin-Like Receptor-1 (LAIR-1) Modulates Immune Response and Confers Poor Prognosis in Invasive Breast Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Najem, H.; Dussold, C.; Pacheco, S.; Miska, J.; McCortney, K.; Steffens, A.; Walshon, J.; Winkowski, D.; Cloney, M.; et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-secreted collagen is associated with immune inhibitor receptor LAIR1 in gliomas. J Clin Invest 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, B.L.; Huang, J.; Gibson, L.; Fradette, J.J.; Chen, H.H.; Koyano, K.; Cortez, C.; Li, B.; Ho, C.; Ashique, A.M.; et al. Antitumor Activity of a Novel LAIR1 Antagonist in Combination with Anti-PD1 to Treat Collagen-Rich Solid Tumors. Mol Cancer Ther 2024, 23, 1144–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Ke, X.; Qiu, J.; Ye, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Luo, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; et al. LAIR1-mediated resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to T cells through a GSK-3beta/beta-catenin/MYC/PD-L1 pathway. Cell Signal 2024, 115, 111039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras, J. Artificial Intelligence Analysis of Ulcerative Colitis Using an Autoimmune Discovery Transcriptomic Panel. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denholm, J.; Schreiber, B.A.; Evans, S.C.; Crook, O.M.; Sharma, A.; Watson, J.L.; Bancroft, H.; Langman, G.; Gilbey, J.D.; Schonlieb, C.B.; et al. Multiple-instance-learning-based detection of coeliac disease in histological whole-slide images. J Pathol Inform 2022, 13, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molder, A.; Balaban, D.V.; Molder, C.C.; Jinga, M.; Robin, A. Computer-Based Diagnosis of Celiac Disease by Quantitative Processing of Duodenal Endoscopy Images. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheppach, M.W.; Rauber, D.; Stallhofer, J.; Muzalyova, A.; Otten, V.; Manzeneder, C.; Schwamberger, T.; Wanzl, J.; Schlottmann, J.; Tadic, V.; et al. Detection of duodenal villous atrophy on endoscopic images using a deep learning algorithm. Gastrointest Endosc 2023, 97, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, B.A.; Denholm, J.; Gilbey, J.D.; Schonlieb, C.B.; Soilleux, E.J. Stain normalization gives greater generalizability than stain jittering in neural network training for the classification of coeliac disease in duodenal biopsy whole slide images. J Pathol Inform 2023, 14, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoleru, C.A.; Dulf, E.H.; Ciobanu, L. Automated detection of celiac disease using Machine Learning Algorithms. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPalma, J.; Suriawinata, A.A.; Tafe, L.J.; Torresani, L.; Hassanpour, S. Resolution-based distillation for efficient histology image classification. Artif Intell Med 2021, 119, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruver, A.M.; Lu, H.; Zhao, X.; Fulford, A.D.; Soper, M.D.; Ballard, D.; Hanson, J.C.; Schade, A.E.; Hsi, E.D.; Gottlieb, K.; et al. Pathologist-trained machine learning classifiers developed to quantitate celiac disease features differentiate endoscopic biopsies according to modified marsh score and dietary intervention response. Diagn Pathol 2023, 18, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, E.; Rajaram, A.; Cote, K.; Farag, M.; Maleki, F.; Gao, Z.H.; Maedler-Kron, C.; Marcus, V.; Fiset, P.O. A Deep Learning-Based Approach to Estimate Paneth Cell Granule Area in Celiac Disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2024, 148, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antibody | Target/pathway | Source | Details |

| CD3 | T-lymphocytes | Leica | Mouse monoclonal, clone LN10, IgG1, C-terminal region |

| CD4 | Helper T-lymphocytes (+antigen presenting cells) | Leica | Mouse monoclonal, clone 4B12, IgG1, external domain |

| CD8 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes | Leica | Mouse monoclonal, clone 4B11, IgG2b, alpha chain cytoplasmic portion |

| CD103 | Alpha E integrin & human mucosal lymphocyte antigen 1 (ITGAE), intraepithelial T lymphocytes, FOXP3+Tregs, CD4+ and CD8+Tcells, dendritic cells, and mast cells in mucosal tissues. Interacts with E-cadherin (epithelial cells) | Leica | Rabbit monoclonal, clone EP206, IgG, residues of human CD103/ITGAE protein |

| Granzyme B | Lytic granules of cytotoxic-T lymphocytes (CTL) and in natural killer (NK) cells | Leica | Mouse monoclonal, clone 11F1, IgG2a, N-terminus of the mature granzyme B molecule |

| TCRβ | T-cell receptor | CST | Rabbit IgG, residues near the amino terminus of human TRBC1/TCRβ constant region 1 protein |

| TCRδ | T-cell receptor | CST | Rabbit IgG, total TRDC/TCRδ protein |

| CD56 (NCAM) | Neurons, astrocytes, Schwann cells, NK cells and a subset of activated T-lymphocytes | Leica | Mouse monoclonal, clone CD564, IgG2b, extracellular domain |

| CD16 | NK cells, granulocytes, activated macrophages and subset T cells (TCRαβ and TCRγδ) | Leica | Mouse monoclonal, clone 2H7, IgG2a, external domain (both transmembrane and GPI-linked forms) |

| LAIR1 (CD305) | Co-inhibitory receptor | CNIO | Rat monoclonal, clone JAVI82A, IgG2a, k |

| PD-L1 | Immune suppression and inhibition of T-cell activity | Leica | Rabbit IgG, clone 73-10, C-terminal domain |

| PD1 (CD279) | Co-inhibitory receptor | CNIO | Mouse monoclonal, clone NAT105, IgG1 |

| BTLA (CD272) | Co-inhibitory receptor | CNIO | Mouse monoclonal, clone FLO67B, IgG1 |

| TOX2 | Transcription factor, maturation of NK cells and differentiation of T follicular helper (TFH) cells | CNIO | Rat monoclonal, clone TOM924D, IgG2a |

| HVEM (TNFRSF14) | Ligand of BTLA | Abcam | Rabbit polyclonal, IgG, exact immunogen is proprietary information |

| CD163 | M2-like macrophages | Leica | Mouse monoclonal, clone 10D6, IgG1, N-terminal region |

| HLA-DP-DQ | Antigen presentation by APC | CNIO | Mouse monoclonal, clone JS76, IgG2a |

| IL4I1 | APC, T-cell inhibition | CNIO | Rat monoclonal, clone BALI265E,543H,573B, IgG2a |

| FOXP3 | Regulatory T-lymphocytes (Tregs) | CNIO | Mouse monoclonal, clone 236A, IgG1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).