Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

27 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

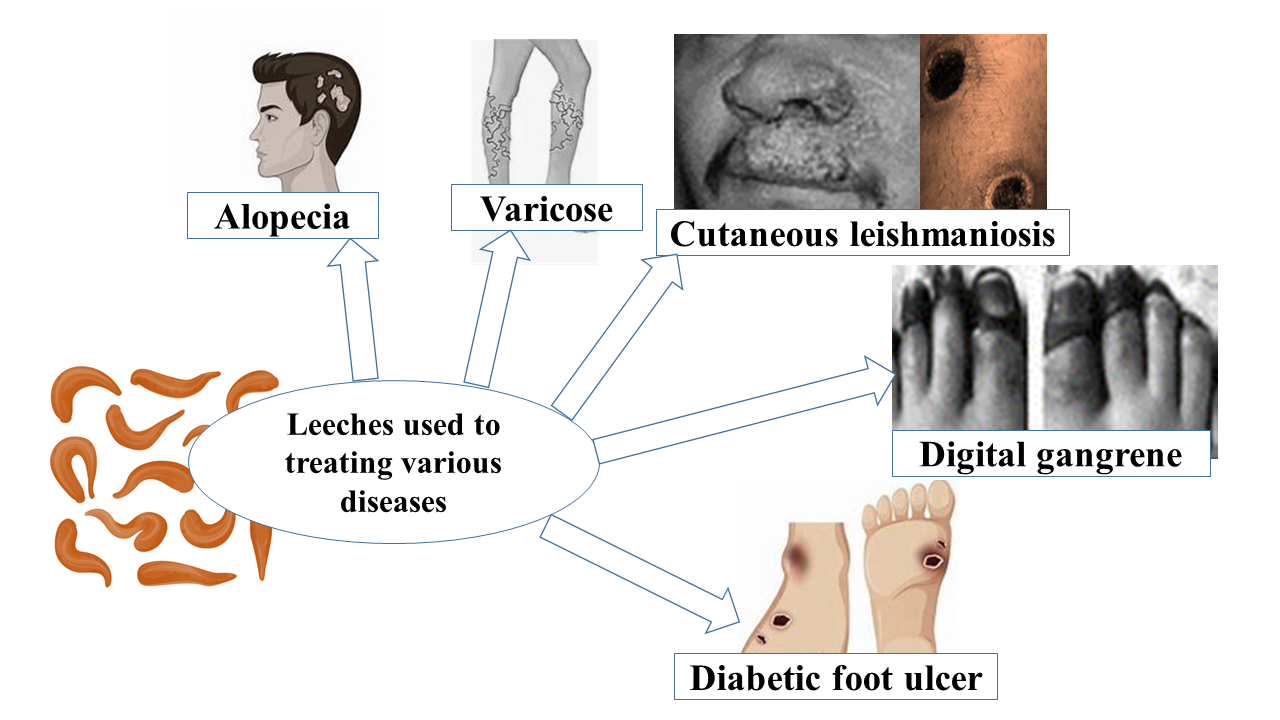

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

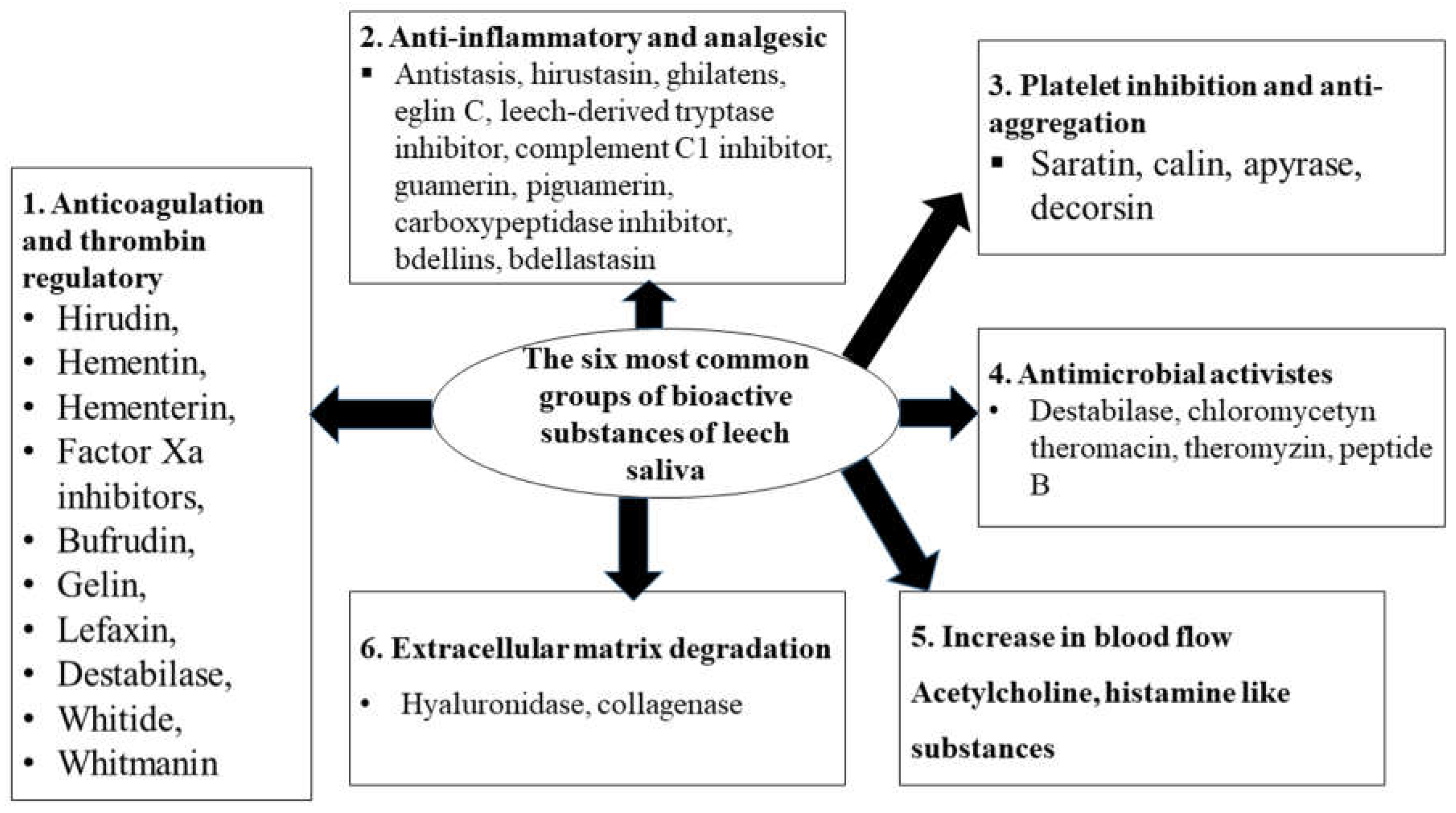

2.1. General Description of Bioactive Substances of Leech Saliva and Their Putative Therapeutic Use

2.1.1. Hirudin

2.1.1.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.2. Antistasin

2.1.2.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.3. Saratin

2.1.3.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.4. Tryptase inhibitor

2.1.4.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.5. Hyaluronidase

2.1.5.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.6. Collagenase

2.1.6.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.7. Calin

2.1.7.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.8. Destabilase

2.1.8.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.9. Apyrase

2.1.9.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.10. Eglin

2.1.10.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.11. Bdellins

2.1.11.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.12. Decorsin

2.1.12.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.13. Hirustasin

2.1.13. Putative Medical Use

2.1.14. Piguamerin

2.1.14. Putative Medical Use

2.1.15. Histamine-like Substances

2.1.15.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.16. Carboxypeptidase A Inhibitors

2.1.16.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.17. Guamerin

2.1.17.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.18. Ghilantens

2.1.18.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.19. Hementerin

2.1.19.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.20. Complement C1 Inhibitor

2.1.20.1. Putative Medical Use

2.1.21. Poeciguamerin

1.1.1.1. Putative Medical Use

| Name of bioactive substances of leech | Species of leech | Mode of action | Significances/effects |

| Hirudin | Hirudo medicinalis | Act on thrombin | Anticoagulant effect |

| Antistasin | Haementeria officinalis | Inhibits Factor Xa, antimetastatic | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects |

| Saratin | Hirudo medicinalis | Inhibits the binding of von Willebrand factor to collagen | Inhibition of platelet function |

| Leech-derived tryptase inhibitor | Hirudo medicinalis | Inhibit proteolytic host mast cells | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects |

| Hyaluronidase | Hirudo medicinalis | Hydrolase activity, acting on glycosylic bonds | Extracellular matrix degradation |

| Collagenase | Hirudo medicinalis | Reduces collagen | Extracellular matrix degradation |

| Calin | Hirudo medicinalis | Prevents the binding of von Willebrand factor to collagen | Inhibition of platelet function |

| Destabilase | Hirudo medicinalis | Cleavage of isopeptide bonds in stabilized fibrin, thrombolysis | Anticoagulant effect Antimicrobial effect |

| Apyrase | Hirudo medicinalis | Action on adenosine 5’ diphosphate, arachidonic acid, platelet-activating factor, and epinephrine | Inhibition of platelet function |

| Eglin | Hirudo medicinalis | Inhibit alpha-chymotrypsin, chymase, subtilisin, elastase, and cathepsin-G | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects |

| Bdellins | Limnatis nilotica | Inhibits trypsin, plasmin, acrosin | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects |

| Decorsin | Macrobdella decora | Acts as an antagonist of platelet glycoprotein II b-III a | Inhibition of platelet function |

| Hirustasin | Hirudo medicinalis | Act on kallikrein, trypsin, chymotrypsin | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects |

| Piguamerin | Hirudo Nippon. | Inhibits plasma, tissue kallikrein, and trypsin | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects |

| Histamine-like substance | Hirudo medicinalis | Act as a vasodilator | Increases the inflow of blood |

| Carboxypeptidase A inhibitor | Hirudo medicinalis | Act in kinin degradation, resulting in agonism of B receptors | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects |

| Acetylcholine | Hirudo medicinalis | Act as a vasodilator | Increases the inflow of blood |

| Guamerin | HirudoNippon | Inhibit elastase | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects |

| Ghilantens | Haementeria ghilianii | Inhibits Factor Xa, antimetastatic | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects |

| Hementerin | Haementeria depressed | Plasminogen activator | Anticoagulant effect |

| Theromin | Theromyzon tessulatum | Acts on thrombin | Anticoagulant effect |

| Complement C1 inhibitor | Hirudo medicinalis | Blocks the activation of the classical pathway of the complement system | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects |

| Poeciguamerin | Poecilobdella manillensis | Acts as a serine protease inhibitor | Anticoagulant effect |

| Haemadin | Haemadipsa sylvestris | Acts on thrombin | Anticoagulant effect |

| Hementin | Haementeria ghilianii | Degrades fibrinogen and fibrin Inhibits tumor spread and metastasis | Anticoagulant effect |

2.2. Current Status and Future Prospective

3. Conclusion and Recommendations

- The researchers and physicians should prepare guidelines for leech therapy protocols, dosage, and safety measures.

- The clinician and researchers should conduct rigorous clinical trials to validate the efficacy of therapeutic applications of leech saliva.

- Recently, the therapeutic applications of leech have been practiced only in advanced countries, so it should be distributed and applied in other countries, particularly in developing ones.

- The researcher should do further investigation on the mechanisms of action, pharmaceutical activities, and therapeutic applications of all other bioactive substances in leech saliva.

Author contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Consent for publication

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Abdisa, T. (2018). Therapeutic importance of leech and impact of leech in domestic animals. MOJ Drug Design Development and Therapy, 2(6), 235–242. [CrossRef]

- Abdualkader, A. M., Ghawi, A. M., Alaama, M., Awang, M., and Merzouk, A. (2013). Leech Therapeutic Applications. Indian J Pharma.Sci., 127–137.

- Abdullah, S., Dar, L. M., Rashid, A., and Tewari, A. (2012). Hirudotherapy / leech therapy : applications and indications in surgery. Archives of Clin. Experi. Surgery, 1, 172–180. [CrossRef]

- Abkowska, E. Z., Olga, C. ´nska-L., Magdalena, B., and Anna, P. (2022). Case reports and experts opinions about current use of leech therapy in dermatology and cosmetology. Cosmetics Case, 9(137), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Aeschlimann, D., & Paulsson, M. (1994). Thromb. Haemostasis. 71, 402–415.

- Alaama, M., AlNajjar, M., and Abdualkader, A. (2011). Isolation and analytical characterization of local Malaysian leech saliva. IIUM Engineering J., 12(4), 32–40.

- Alaama, M., Kucuk, O., Bilir, B., and Merzouk, A. (2024). Pharmacological research - modern Chinese medicine development of leech extract as a therapeutic agent : A chronological review. Pharma. Res. Modern Chinese Med., 10, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A., Hassona, M., Meckling, G., Chan, L., Chin, M., and Abdualkader, A. (2015). Assessment of the antitumor activity of leech (huridinaria manillensis) saliva extract in prostate cancer. Cancer Res., 75(15). [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C., Krafft, B., and Frech, M. (2001). Production and characterization of saratin, an inhibitor of von Willebrand factor-dependent platelet adhesion to collagen. Semin. Thromb .Hemost., 27, 337–348.

- Baskova, I., Kostrjukova, E., Vlasova, M., Kharitonova, O., Levitskiy, S., Zavalova, L., Moshkovskii, S., and Lazarev, V. (2008). Proteins and peptides of the salivary gland secretion of medicinal leeches Hirudo verbana, H. medicinalis, and H. orientalis,. Biochem. Mosc., 73(3), 315–320.

- Baskova, I. P., Ferner, Z., Balkina, A. S., Kozin, S. A., Kharitonova, O. V., Zavalova, L. L., and Zgoda, V. G. (2008). Steroids, histamine, and serotonin in the medicinal leech salivary gland secretion. Biochemistry (Moscow) Supplement Series B: Biomed. Chem., 2(3), 215–225. [CrossRef]

- Baskova, I. P., Nikonov, G. I., and Khalil, S. (1988). Thrombolytic agents of the preparation from the medicinal leeches. Folia Haematol, 115, 166–170.

- Baskova, I. P., Zavalova, L. L., Basanova, A. V, and Sass, A. V. (2001). Separation of monomerizing and lysozyme activities of destabilase from medicinal leech salivary gland secretion. Biochem.(Moscow), 66(12), 1368–1373.

- Baskova, I., and Zavalova, L. (2001). Proteinase inhibitors from the medicinal leech Hirudo medicinalis. Biochem. (Mosc), 66, 703–714.

- Baskova, I., Zavalova, Z., Basanova, A., Moshkovskii, S., and Zgoda, V. (2004). Protein profiling of the medicinal leech salivary gland secretion by proteomic analytical methods. Biochem. Mosc., 69(7), 770–775.

- Blankenship, D., Brankamp, R., Manley, G., and Cardin, A. (1990). Amino acid sequence of ghilanten: anticoagulant-antimetastic principle of the south American leech, Haementeria ghilianii. B. Iochemical and Biophysical Res. Communucation, 166, 1384–1389.

- Braun, N. J., Bodmer, J. L., Virca, G. D., Μvirca, G., Maschler, R., C., and Schnebli, H. P. (1987). Kinetic studies on the interaction of eglin c with human leukocyte elastase and cathepsin G. 368, 299–308.

- Buote, N. (2014). The use of medical leeches for venous congestion. Vet. Comparative Orthopedics and Traumatology., 27(3), 173‒178.

- Campos, I., Silva, M., Azzolini, S., Souza, A., Sampaio, C., and Fritz, H. (2004). Evaluation of phage display system and leech-derived tryptase inhibitor as a tool for understanding the serine proteinase specificities. Arch Bioche. Biophys., 425, 87–94.

- Cardin, A., and Sunkara, S. (1994). Ghilanten antimetastatic principle from the south American leech Haementeria ghilianii. European Patent No. EP 0404055. Munich, European Patent Office, issued March 2, 1994. Germany.

- Chuang, C., Lingling, M., Xiangshen, L. I., Li, P., Azmir, N., Hashim, A., and Jumuddin, F. A. (2023). The actions of leech saliva components and their mechanisms in antitumor activity. Journal of Propulsion Techno., 44, 3092–3101.

- Chudzinski-Tavassi, A. M., Bermejo, E., Rosenstein, R. E., Faria, F., Keller Sarmiento, M. I., Alberto, F., Sapaio, M. U., and Lazzari, M. A. (2003). Nitridergic platelet pathway activation by hementerin, a metalloprotease from the leech Haementeria depressa. Biologi. Chem., 384(9). 1333–1339. [CrossRef]

- Chudzinski-Tavassi, A., Kelen, E., de Paula, R. A., Loyau, S., Sampaio, C., and Bon, E. (1998). Angles-Cano, Fibrino (geno) lytic properties of purified hementerin, a metalloproteinase from the leech Haementeria depressa,. Thromb.Haemost., 80(07), 155–160.

- Das, B. K. (2015). An Overview on Hirudotherapy / leech therapy. Indian J. Pharma. Sci., 1(1), 32–45.

- Di Marco, S., and Priestle, J. P. (1997). Structure of the complex of leech-derived tryptase inhibitor (LDTI) with trypsin and modeling of the LDTI-tryptase system. Structure, 5(11), 1465–1474. [CrossRef]

- Dodt, J., Müller, H. P., Seemüller, U., and Chang, J. Y. (1984). The complete amino acid sequence of hirudin, a thrombin specific inhibitor: Application of color carboxymethylation. Febs Lett. 165, 180–184. [CrossRef]

- Dudhrejiya, A. V, Pithadiya, S. B., Patel, A. B., and Amitkumar, J. (2023). Medicinal leech therapy and related case study : Overview in current medical field. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem., 12(1), 21–31.

- Eldor, A., Orevi, M., and Rigbi, M. (1996). The role of the leech in medical therapeutics. Blood Reviews, 10(201–209), 201–209.

- Esser, D., Lange, W., Schröder, J., and Wiswedel, I. (2009). Antitumor activity of leech therapy in an animal model of prostate cancer. J. Complem. Integ. Med., 6(1).

- Fritz, H., Gebhardt, M., Meister, R., and Fink, E. (1970). Trypsin-plasmin inhibitors from leeches isolation, amino acid composition, inhibitory characteristics. Proceedings of the International Research Conference on Proteinase Inhibitors, Munich, November 4–6, 271–280. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, H., Oppitz, K., and Gebhardt, M. (1969). On the presence of a trypsin-plasmin inhibitor in hirudin. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol. Chem., 350, 91-92.

- Gileva, O., and Mumcuoglu, K. (2013). Hirudotherapy in: Grassberger, M Sherman, RA Gileva, OS Kim, CMH (eds)., Mumcuoglu KYBiotherapy - Histo- ry, Principles and Practice: A Practical Guide to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Disease using Living Organisms. London, Springer.

- Glyova, O. (2005). Modern hirudotherapy — a review. (Biotherapeutics, Education and Research Foundation). he (BeTER) LeTER. 2, 1–3.

- Green, D., and Karpatkin, S. (2010). Role of thrombin as a tumor growth factor. Cell Cycle, 9(4), 656–661. [CrossRef]

- Gronwald, W., Maurer, T., Kremer, W., Frech, M., Bomke, J., Domogalla, B., Hubber, F., Schumann, F., Fink, F., Rysiok, T., and Robert, H. K. (2008). Structure of the Leech Protein Saratin and Characterization of Its Binding to Collagen. J. Molecular Bio., 381, 913–927. [CrossRef]

- Gross, U., and Roth, M. (2007). The Biochemistry of Leech Saliva. In: Medicinal Leech Therapy. Michaelsen, A., M. Roth and G. Dobos, Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany.

- Hackenberger, P. N., and Janis, J. (2019). A comprehensive review of medicinal leeches in plastic and reconstructive surgery. PRS Global Open, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Harsfalvi, B. J., Stassen, J. M., Hoylaerts, M. F., Houtte, E. Van, Sawyer, R. T., Vermylen, J., and Deckmyn, H. (1995). Calin from hirudo medicinalis, an inhibitor of von willebrand factor binding to collagen under static and flow conditions. Blood, 85, 705–711.

- Hildebrandt, J., and Lemke, S. (2011). Small bite , large impact – saliva and salivary molecules in the medicinal leech , Hirudo medicinalis. Naturwissenschaften, 98, 995–1008. [CrossRef]

- Houschyar, K., Momeni, A., Maan, Z., Pyles, M., Jew, O., and Strathe, M. (2015). Medical leech therapy in plastic reconstructive surgery. Wien. Med .Wochen- Schr., 165, 419-425.

- Hovingh, P., and Linker, A. (1999). Hyaluronidase activity in leeches (Hirudinea). Comparative Biochem. Physiology Part B, 124, 319–326.

- Jung, H. Il, Kim, S. Il, Ha, K. S., Joe, C. O., and Kang, K. W. (1995). Isolation and characterization of guamerin, a new human leukocyte elastase inhibitor from Hirudo nipponia. J. Biologi. Chem., 270 (23), 13879–13884). [CrossRef]

- Junren, C., Xiaofang, X., Huiqiong, Z., Gangmin, L., and Yanpeng, Y. (2021). Pharmacological activities and mechanisms of hirudin and its derivatives - a review. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Kaliyaperumal, K., Elamin, A., Dohare, S., And Katiyar, K. (2023). A study on leech ’ s therapeutic applications a study on leech ’ s therapeutic. Eur. Chem. Bull, 12, 2643–2647.

- Kashuba, E., Bailey, J., Allsup, D., and Cawkwell, L. (2013). The kinin–kallikrein system: physiological roles, pathophysiology and its relationship to cancer biomarkers. Biomarker, 5804, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Kelen, E., and Rosenfeld, G. (1975). Fibrinogenolytic substance (Hementerin) of Brazilian blood sucking lechhes. Haemostasis, 4, 51–64.

- Kim, D., and Kang, K. (1998). Amino acid sequence of piguamerin, an antistasin-type protease inhibitor from the blood sucking leech Hirudo nipponia. Eur J Biochem, 254, 692–697.

- Kim, I. J., and Lee, M. K. (1997). Guamerin, a novel protease inhibitor from the medicinal leech, Hirudo nipponia. Biochemical and Biophysical Res. Communications, 235(2), 302-306.

- Krezel, A., Wagner, G., Seymour-Ulmer, J., and Lazarus, R. (1994). Structure of the RGD protein decorsin: conserved motif anddistinct function in leech proteins that affect blood clotting. Sci., 264, 1944–1948.

- Kwak, H., Park, J., Irene, B., Jim, M., Park, S. C., and Cho, S. (2019). Spatiotemporal expression of anticoagulation factor antistasin in freshwater leeches. Int. J Molecular Sci., 20, 1–12.

- Lemke, S., and Vilcinskas, A. (2020). European medicinal leeches — new roles in modern medicine. Biomed., 8(99), 1–12.

- Linker, A., Hoffma, P., and Meyer, K. (1957). The hyaluronidase of the leech: an endoglucuronidase. Nature, 180:810–811.

- Liu, Z., Tong, X., Su, Y., Wang, D., Du, X., and Zhao, F. (2019). In-depth profiles of bioactive large molecules in saliva secretions of leeches determined by combining salivary gland proteome and transcriptome data. J. Proteomics, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Malik, B., Djuanda, U., Jayanegara, A., and Rahminiwati, M. (2022). Leech saliva and its potential use in animal health and production : a review. Int. J. Dairy Sci., 17(2), 41–53. [CrossRef]

- Markwardt, F. (1991). Past, present and future of hirudin. Haemostasis. 21(1)21, 11–26. [CrossRef]

- Markwardt, F. (1994). The development of hirudin as an antithrombotic drug. Thromb. Res., 74, 1. [CrossRef]

- Markwardt, F. (2002). of Haemostasis historical perspective of the development of thrombin inhibitors. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb., 32, 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Menzel, E. J., and Farr, C. (1998). Hyaluronidase and its substrate hyaluronan : biochemistry , biological activities and therapeutic uses. Cancer Letters, 131, 3–11.

- Michalsen, A., Roth, M., Dobos, G., and Aurich, M. (2007). Medicinal leech therapy. Stattgurt: Apple Wemding; 2007.

- Moser, M., Auerswald, E., Mentele, R., Eckerskorn, C., Frit, H., and Fink, E. (1998). Bdellastasin, a serine protease inhibitor of the antistasin family from the medical leech (Hirudo medicinalis). Eur. J .Biochem., 253, 212–20.

- Munoro, R., Powell, C. J., and Sawyer, R. T. (1991). Calin: a platelet adhesion inhibitor from the saliva of the medical leech. Blood Coagulation and Fibrinolysis, 2, 179–184.

- Munshi, Y., Ara, I., Rafique, H., and Ahmed, Z. (2008). Leeching in the History-A Review. Pakistan J. Biological Sci., 11(13), 1650–1653. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, G. (2002). Pharmacology of Recombinant Hirudin. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 28 (5), 415–423.

- Nutt, E., Jain, D., Lenny, A., Schaffe, L., Siegl, P., and Dunwiddie, C. (1991). Purification and characterization of recombinant antistasin: a leech-derived inhibitor of coagulation factor Xa. Arch.Biochem. Biophys, 285, 37–44.

- Pantojauceda, D., Arolas, J. L., Aviles, F. X., Santoro, J., Ventura, S., and Sommerhoff, C. P. (2009). Deciphering the structural basis that guides the oxidative folding of leech-derived tryptase inhibitor. 284(51), 35612–35620. [CrossRef]

- Pohlig, G., Fendrich, G., Knecht, R., Eder, B., Piechottka, G., Sommerhoff, & Heim, J. (1996). Purification, characterization and biological evaluation of recombinant leech-derived tryptase inhibitor (rLDTI) expressed at high level in the yeast. Eur. J. Biochem., 626, 619–626.

- Rahul, S., Swarnasmita, P., and Janhavi, D. (2014). Hirudotherapy-a holistic natural healer. IJOCR. 2(6), 59-69.

- Reverter, D., Vendrell, J., Canals, F., Horstmann, J., Avile, F. X., Fritz, H., and Sommerhoff, C. P. (1998). A Carboxypeptidase Inhibitor from the Medical Leech Hirudo medicinalis. J. Biologi. chem., 273(49), 32927–32933.

- Rigbi, M., Levy, H., Iraqi, F., and Teitelbaum, M. (1987). The saliva of the medicinal leech hirudo medicinalis. Biochemical characterization of the high molecular weight fraction. Comp. Biochem. Physiol, 87B(3), 567–573.

- Rink, H., Liersch, M., Sieber, P., and Meyer, F. (1984). A large fragment approach to DNA synlthesis: total synthesis of a gene for the protease inhibitor eglin c from the leech Hirudo medicinalis and its expression in E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res., 12(16), 6369–6387.

- Salzet, M. (2002). Leech thrombin inhibitors. Current pharmaceutical design. 8(7), 493‒503.

- Seemuller, U., Dodt, J., Fink, E., and Fritz, H. (1986). Proteinase inhibitors of the leech Hirudo medicinalis (hirudins, bdellins, eglins). In: Barettand AJ, Salvesen G, eds. Proteinase Inhibitors. New York, NY: Elsevier Science Ltd.

- Seymour, L., Francisco, S., Henzelg, J., Stultsq, T., and Lazarus, A. (1990). Decorsin: A potentglycoprotein IIb-IIIa antagonist and platelet aggregation inhibitor from the leech macrobdella decora. J. Biologi. Chem., 265(17), 10143–10147. [CrossRef]

- Shakouri, A., Parvan, R., Adliouy, N., and Abdolalizadeh, J. (2019). Purification of hyaluronidase as an anticancer agent inhibiting. Biomed. Chromatography, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Shakouri, A., and Wollina, U. (2021). Time to change theory ; medical leech from a molecular medicine perspective leech salivary proteins playing a potential role in medicine. Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, 11, 261–266. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V. M., & Jagdhane, V. C. (2020). Role of leech therapy to encounter heel pain in associated conditions of retrocalcaneal bursitis, plantar fascitis with tenosynovitis: a case study. retrieved from https://wjpr.s3.ap-south- 1.amazonaws.com/article.

- Siebeck, M., Spannag, M., Hoffmann, H., and Fink, E. (1992). Effects of protease inhibitors in experimental septic shock. Agents actions suppl. 38, 421–427.

- Sig, A., Guney, M., and UskudarGuclu, A. (2017). Medicinal leech therapy-an overall perspective. J. Integr. Med. Res., 6(4), 337–343.

- Sig, A. k., Guney, M., Uskudar, A. G., and Ozmen, E. (2017). Medicinal leech therapy an overall perspective. Integr.Med. Res., 6(4), 337–343. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. P. (2010). Complementary therapies in clinical practice medicinal leech therapy ( hirudotherapy ) : a brief overview. Complementary therapies in clinical practice, 16(4), 213–215. [CrossRef]

- Sollner, C., Mentele, R., Eckerskorn, C., Fritz, H., and Sommerhoffl, C. P. (1994). Isolation and characterization of hirustasin , an antistasin-type serine-proteinase inhibitor from the medical leech Hirudo medicinalis. Eur. J. Biochem. 219, 943, 937–943.

- Stange, R., Moser, C., Hopfenmueller, W., Mansmann, U., Buehring, M., and Uehleke, B. (2012). Randomised controlled trial with medical leeches for osteoarthritis of the knee. Complement Ther. Med., 20, 1–7.

- Sudhadevi, M. (2021). Leech therapy - a holistic treatment international journal of advance research in nursing leech therapy : a holistic treatment. Int. J. Advance Res. in Nursing, 3, 130–132. [CrossRef]

- Tasiemski, A., and Salzet, M. (2012). Use of extract of leeches as antibacterial agent. U.S. Patent No. 20,120,251,625. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and trademark office, issued October 4, 2012. WO 2011/045427 A1, 2011.

- Tuszynski, G., Gasic, T., and Gasic, G. (1987). Isolation and characterization of antistasin. An inhibitor of metastasis and coagulation. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 9718–9723.

- Varsha, S., Niraj, S., and Pradeep, K. (2020). Leeth therapy (Jalaukavacharana)-A novel gift from Ayurveda for treatment of medico-surgical diseases. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev., 11(6), 845-852.

- Vilahur, G., Duran, X., Juan-Babot, O., Casani, L., and Badimon, L. (2004). Antithrombotic effects of saratin on human atherosclerotic plaques. Thromb. Haemostasis. 92, 191–200.

- Wang, C., Chen, M., Lu, X., Yang, S., Yang, M., Fang, Y., Lai, R., and Duan, Z. (2023). Isolation and characterization of Poeciguamerin , a peptide with dual analgesic and anti-Thrombotic activity from the Poecilobdella manillensis Leech. Int. J. Molecular Sci., 24, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ware, F. L., and Luck, M. R. (2017). Evolution of salivary secretions in haematophagous animals. 10.

- Yapici, K., Durmus, M., Training, G., Arsenishvilli, A., and Group, M. H. (2017). Hirudo medicinalis - historical and biological background and their role in microsurgery: Review article. Hand and Microsurgery, 6, 34–38. [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S., Jameel, S., and Zaman, F. (2011). A systematic overview of the medicinal importance of sanguivorous leeches. Altern. Med. Rev., 16(1), 59–65.

- Zaidi, S. M. A., Juhi, S. J., Sultana, A., and Khan, S. (2011). A Systematic overview of the medicinal importance of Sanguivorous Leeches. Alternative Medicine Review: A J. Clinical Therapeutic, 16, 60–64.

- Zavalova, L. L., Yudina, T. G., Artamonova, I. I., and Baskova, I. P. (2006). Antibacterial Non-Glycosidase Activity of Invertebrate Destabilase-Lysozyme and of Its Helical Amphipathic Peptides. 117997, 158–160. doi.org/10.1159/000092904.

- Zavalova, L., Lukyanov, S., Baskova, I., Snezhkov, E., Berezhnoy, S., Bogdanova, E., Barsova, E., and Sverdlov, E. (1996). Mol. Gen. Genet. 253, 20–25.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).