Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Impact of Water-Deficit Stress on Plants

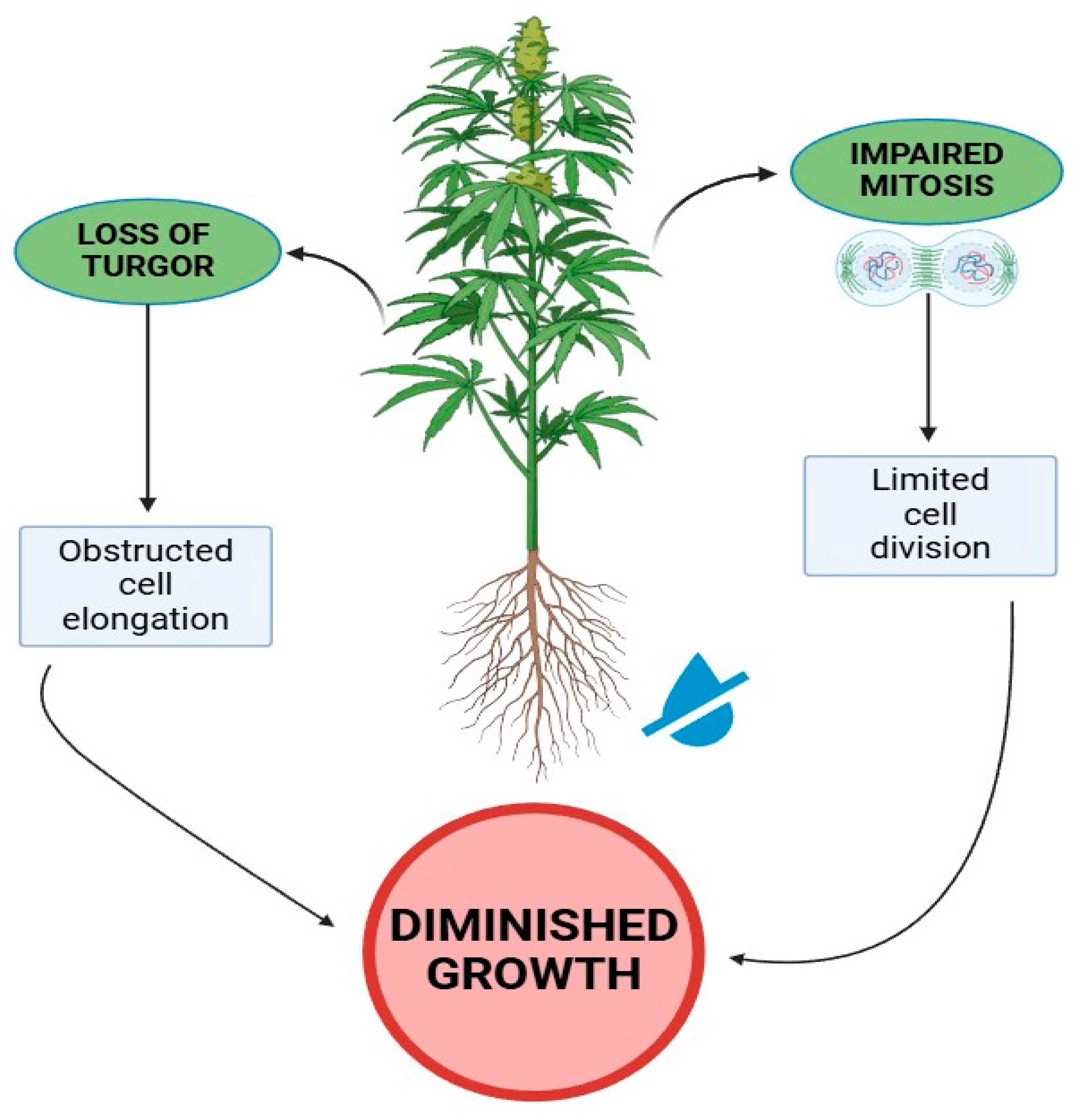

3.1. Overall Plant Growth

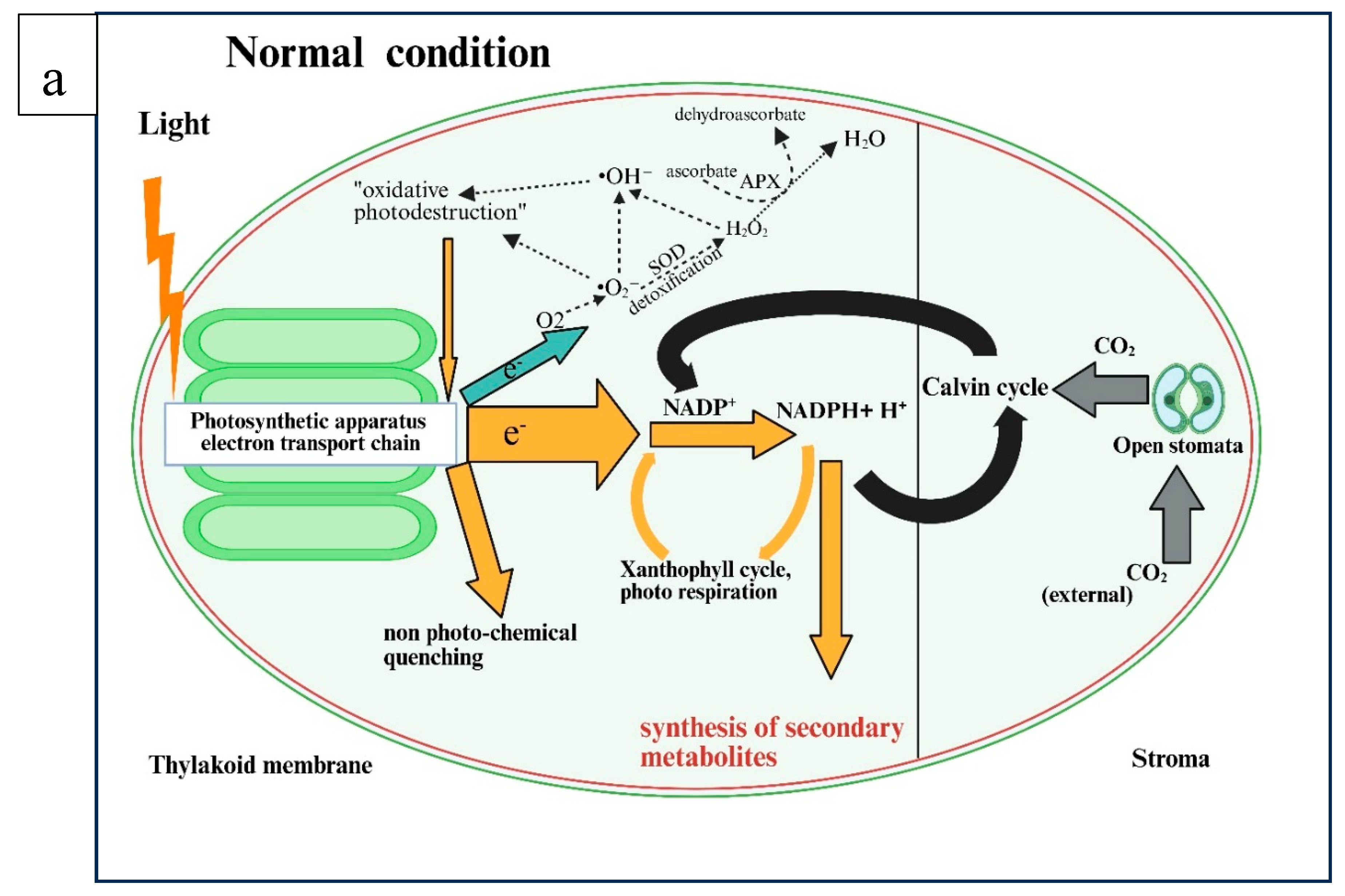

3.2. Photosynthesis and Physiology

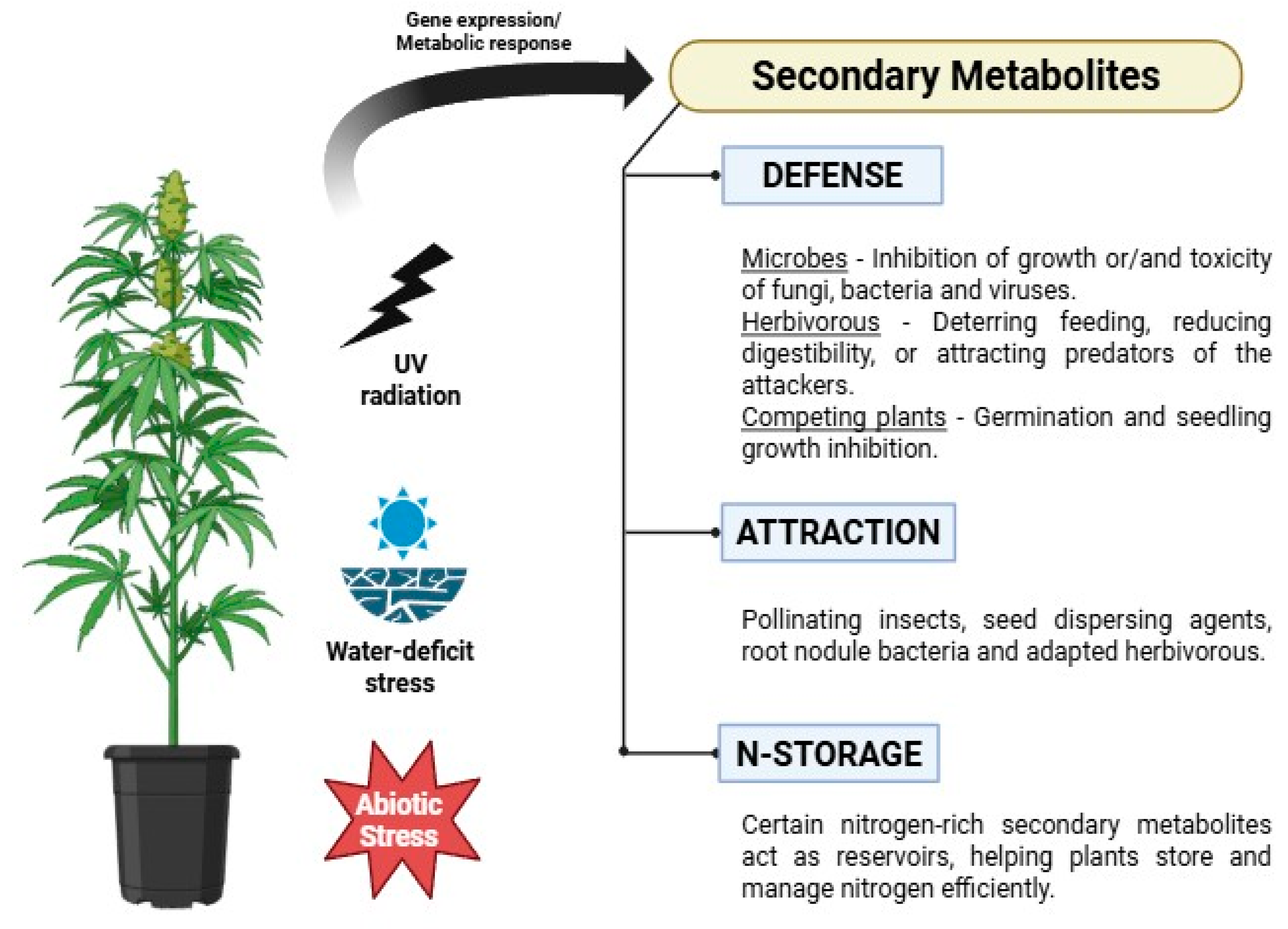

3.3. Plant Secondary Metabolites

4. Impact of Water-deficit STRESS on Cannabis

4.1. Growth and Yield of Cannabis

4.2. Production of Secondary Metabolites of Cannabis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McPartland, J. M.; Hegman, W.; Long, T. Cannabis in Asia: its center of origin and early cultivation, based on a synthesis of subfossil pollen and archaeobotanical studies. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 2019, 28(6), 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-L. An archaeological and historical account of cannabis in China. Economic botany 1974, 28(4), 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E. Evolution and Classification of Cannabis sativa (Marijuana, Hemp) in Relation to Human Utilization. The Botanical Review 2015, 81(3), 189–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.; Merlin, M. Cannabis: evolution and ethnobotany; Univ of California Press, 2016.

- Small, E.; Cronquist, A. A practical and natural taxonomy for Cannabis. Taxon 1976, 405–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, S.; Melzer, R.; McCabe, P. F. Cannabis sativa . Curr Biol 2020, 30(1), R8–R9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudak, J. Marijuana: A short history; Brookings Institution Press, 2020.

- Skorbiansky, S. R.; Thornsbury, S.; Camp, K. M. Legal Risk Exposure Heightens Uncertainty in Developing US Hemp Markets. Choices 2021, 36(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E. Plants, life, and man. Andrew Melrose, London 1954, 120-133.

- Bonini, S. A.; Premoli, M.; Tambaro, S.; Kumar, A.; Maccarinelli, G.; Memo, M.; Mastinu, A. Cannabis sativa: A comprehensive ethnopharmacological review of a medicinal plant with a long history. J Ethnopharmacol 2018, 227, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, C. M.; Hausman, J. F.; Guerriero, G. Cannabis sativa: The Plant of the Thousand and One Molecules. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacher, P.; Kogan, N. M.; Mechoulam, R. Beyond THC and Endocannabinoids. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2020, 60, 637–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, E. Reefer madness: Sex, drugs, and cheap labor in the American black market; HMH, 2004.

- Ramakrishna, A.; Ravishankar, G. A. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal Behav 2011, 6(11), 1720–1731, From NLM Medline. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, Z.; Conroy, M.; Vanden Heuvel, B. D.; Pauli, C. S.; Park, S. H. Cannabis Contaminants Limit Pharmacological Use of Cannabidiol. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 571832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, J.; Bernstein, N. Chemical and Physical Elicitation for Enhanced Cannabinoid Production in Cannabis. In Cannabis sativa L. - Botany and Biotechnology, 2017; pp 439-456.

- Eichhorn Bilodeau, S.; Wu, B. S.; Rufyikiri, A. S.; MacPherson, S.; Lefsrud, M. An Update on Plant Photobiology and Implications for Cannabis Production. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, N.; Gorelick, J.; Koch, S. Interplay between chemistry and morphology in medical cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.). Industrial Crops and Products 2019, 129, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, R.; Weeden, H.; Bogush, D.; Deguchi, M.; Soliman, M.; Potlakayala, S.; Katam, R.; Goldman, S.; Rudrabhatla, S. Enhanced tolerance of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) plants on abandoned mine land soil leads to overexpression of cannabinoids. PLoS One 2019, 14(8), e0221570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgel, L.; Hartung, J.; Schibano, D.; Graeff-Honninger, S. Impact of Different Phytohormones on Morphology, Yield and Cannabinoid Content of Cannabis sativa L. Plants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, K.; Pratibha; Priya Soni, R.; Kumar, P.; Chauhan, D.; Augustine, A. A. Drought; Influence of Drought in Agriculture and Management Strategies for Drought-a Review. Asian Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology & Environmental Sciences 2023, 25(04), 638–642. [CrossRef]

- He, M.; He, C. Q.; Ding, N. Z. Abiotic Stresses: General Defenses of Land Plants and Chances for Engineering Multistress Tolerance. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, N.; Rivero, R. M.; Shulaev, V.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Abiotic and biotic stress combinations. New Phytol 2014, 203(1), 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.; Bhardwaj, S.; Landi, M.; Sharma, A.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Sharma, A. The Impact of Drought in Plant Metabolism: How to Exploit Tolerance Mechanisms to Increase Crop Production. Applied Sciences 2020, 10(16). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, F.; Olivos-Hernandez, K.; Stange, C.; Handford, M. Abiotic Stress in Crop Species: Improving Tolerance by Applying Plant Metabolites. Plants (Basel) 2021, 10(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.; Petropoulos, S. A.; Rouphael, Y. Response and Defence Mechanisms of Vegetable Crops against Drought, Heat and Salinity Stress. Agriculture 2021, 11(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; He, C. G.; Wang, Y. J.; Bi, Y. F.; Jiang, H. Effect of drought and heat stresses on photosynthesis, pigments, and xanthophyll cycle in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Photosynthetica 2020, 58(5), 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, F.; Ancin, M.; Fakhet, D.; Gonzalez-Torralba, J.; Gamez, A. L.; Seminario, A.; Soba, D.; Ben Mariem, S.; Garriga, M.; Aranjuelo, I. Photosynthetic Metabolism under Stressful Growth Conditions as a Bases for Crop Breeding and Yield Improvement. Plants (Basel) 2020, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami Bistgani, Z.; Barker, A. V.; Hashemi, M. Physiology of medicinal and aromatic plants under drought stress. The Crop Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. C. DIAS, W. B. Limitations of photosynthesis in Phaseolus vulgaris under drought stress: gas exchange, chlorophyll fluorescence and Calvin cycle enzymes. PHOTOSYNTHETICA 2010, 48(1), 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, M.; Zhou, K.; Sun, T.; Hu, L.; Li, C.; Ma, F. Uptake and metabolism of ammonium and nitrate in response to drought stress in Malus prunifolia. Plant Physiol Biochem 2018, 127, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippou, P.; Antoniou, C.; Fotopoulos, V. Effect of drought and rewatering on the cellular status and antioxidant response of Medicago truncatula plants. Plant Signal Behav 2011, 6(2), 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keipp, K.; Hütsch, B. W.; Ehlers, K.; Schubert, S. Drought stress in sunflower causes inhibition of seed filling due to reduced cell-extension growth. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2020, 206(5), 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coussement, J. R.; Villers, S. L. Y.; Nelissen, H.; Inze, D.; Steppe, K. Turgor-time controls grass leaf elongation rate and duration under drought stress. Plant Cell Environ 2021, 44(5), 1361–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarani Mahnaz, H. S. M. , Mahdi M.R. The effect of drought stress on chlorophyll content, root growth, glucosinolate and proline in crop plants. International Journal of Farming and Allied Sciences 2014, 3(9), 994–997. [Google Scholar]

- Lebaschy, M. H.; Sharifi ashoor abadi, E. Growth indices of some medicinal plants under different water stresses. Iranian Journal of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Research 2004, 20(3), 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzazi, N.; Khodambashi, M.; Mohammadi, S. The effect of drought stress on morphological characteristics and yield components of medicinal plant fenugreek. Isfahan University of Technology-Journal of Crop Production and Processing 2013, 3(8), 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Omae, H.; Egawa, Y.; Kashiwaba, K.; Shono, M. Adaptation to heat and drought stresses in snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) during the reproductive stage of development. Japan Agricultural Research Quarterly: JARQ 2006, 40(3), 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Moghaddam, H.; Naghdi Badi, H.; Naghavi, M. R.; Salami, S. A.; Solaiman, Z. Agronomic, phytochemical and drought tolerance evaluation of Iranian cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.) ecotypes under different soil moisture levels: a step towards identifying pharmaceutical and industrial populations. Crop & Pasture Science 2023, 74(12), 1238–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-h.; Xu, X.-f.; Sun, Y.-m.; Zhang, J.-l.; Li, C.-z. Influence of drought hardening on the resistance physiology of potato seedlings under drought stress. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2018, 17(2), 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Ma, Y.; Li, S.; Dong, S.; Zu, W. Transcriptome profilling analysis characterized the gene expression patterns responded to combined drought and heat stresses in soybean. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2018, 77, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverne, L.; Krieger-Liszkay, A. Moderate drought stress stabilizes the primary quinone acceptor Q(A) and the secondary quinone acceptor Q(B) in photosystem II. Physiol Plant 2021, 171(2), 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospisil, P. Production of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009, 1787(10), 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, R.; Luyckx, M.; Xu, X.; Legay, S.; Sergeant, K.; Hausman, J.-F.; Lutts, S.; Cai, G.; Guerriero, G. Reactive oxygen species and heavy metal stress in plants: Impact on the cell wall and secondary metabolism. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2019, 161, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabin, G.; Lightburn, K.; Hashemi, S. M.; Moghada, M. S. K.; Jalilian, A. Evaluation of nitrate leaching, fatty acids, physiological traits and yield of rapeseed (Brassica napus) in response to tillage, irrigation and fertilizer management. Plant and Soil 2022, 473((1-2)), 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmar, D.; Kleinwachter, M. Stress enhances the synthesis of secondary plant products: the impact of stress-related over-reduction on the accumulation of natural products. Plant Cell Physiol 2013, 54(6), 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinwächter, M.; Selmar, D. New insights explain that drought stress enhances the quality of spice and medicinal plants: potential applications. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2014, 35(1), 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hideg, É.; Spetea, C.; Vass, I. Superoxide radicals are not the main promoters of acceptor-side-induced photoinhibitory damage in spinach thylakoids. Photosynthesis Research 1995, 46, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormann, H.; Neubauer, C.; Asada, K.; Schreiber, U. Intact chloroplasts display pH 5 optimum of O 2-reduction in the absence of methyl viologen: Indirect evidence for a regulatory role of superoxide protonation. Photosynthesis research 1993, 37, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacif de Abreu, I.; Mazzafera, P. Effect of water and temperature stress on the content of active constituents of Hypericum brasiliense Choisy. Plant Physiol Biochem 2005, 43(3), 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshedloo, M. R.; Craker, L. E.; Salami, A.; Nazeri, V.; Sang, H.; Maggi, F. Effect of prolonged water stress on essential oil content, compositions and gene expression patterns of mono- and sesquiterpene synthesis in two oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) subspecies. Plant Physiol Biochem 2017, 111, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, H. Z.; Ibrahim, M. H.; Mohamad Fakri, N. F. Impact of soil field water capacity on secondary metabolites, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), maliondialdehyde (MDA) and photosynthetic responses of Malaysian kacip fatimah (Labisia pumila Benth). Molecules 2012, 17(6), 7305–7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Caparrós, P.; Romero, M.; Llanderal, A.; Cermeño, P.; Lao, M.; Segura, M. Effects of Drought Stress on Biomass, Essential Oil Content, Nutritional Parameters, and Costs of Production in Six Lamiaceae Species. Water 2019, 11(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibi, S.; Sayed Tabatabaei, B. E.; Saeidi, G.; Talebi, M.; Matkowski, A. The effect of drought stress on polyphenolic compounds and expression of flavonoid biosynthesis related genes in Achillea pachycephala Rech.f. Phytochemistry 2019, 162, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, P.; Karimmojeni, H.; Razmjoo, J. Changes in essential oil yield and fatty acid contents in black cumin (Nigella sativa L.) genotypes in response to drought stress. Industrial Crops and Products 2020, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Kong, W.; Wong, G.; Fu, L.; Peng, R.; Li, Z.; Yao, Q. AtMYB12 regulates flavonoids accumulation and abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Genet Genomics 2016, 291(4), 1545–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Chan, Z. Improvement of plant abiotic stress tolerance through modulation of the polyamine pathway. J Integr Plant Biol 2014, 56(2), 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha Leme Filho, J. F.; Chim, B. K.; Bermand, C.; Diatta, A. A.; Thomason, W. E. Effect of organic biostimulants on cannabis productivity and soil microbial activity under outdoor conditions. J Cannabis Res 2024, 6(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves Manuela M., M. J. P. P. J. Understanding plant responses to drought — from genes to the whole plant. Functional Plant Biology 2003, 30, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaducci, S.; Zatta, A.; Pelatti, F.; Venturi, G. Influence of agronomic factors on yield and quality of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) fibre and implication for an innovative production system. Field Crops Research 2008, 107(2), 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesina, I.; Bhowmik, A.; Sharma, H.; Shahbazi, A. A Review on the Current State of Knowledge of Growing Conditions, Agronomic Soil Health Practices and Utilities of Hemp in the United States. Agriculture 2020, 10(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Vijaya, I. M. K. Production and Quality of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) in Response to Water Regimes. Doctoral dissertation, University Of Tasmania 2021.

- Petropoulos, S. A.; Daferera, D.; Polissiou, M. G.; Passam, H. C. The effect of water deficit stress on the growth, yield and composition of essential oils of parsley. Scientia Horticulturae 2008, 115(4), 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, S. L.; Riggi, E.; Testa, G.; Scordia, D.; Copani, V. Evaluation of European developed fibre hemp genotypes (Cannabis sativa L.) in semi-arid Mediterranean environment. Industrial Crops and Products 2013, 50, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arad, N. Effect of drought stress on relative expression of some key genes involved in cannabisis in medicinal cannabis. Master’s thesis, University of Tehran, Karaj, Iran.[In Persian], 2016.

- Campbell, B. J.; Berrada, A. F.; Hudalla, C.; Amaducci, S.; McKay, J. K. Genotype × Environment Interactions of Industrial Hemp Cultivars Highlight Diverse Responses to Environmental Factors. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 2019, 2(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herppich, W. B.; Gusovius, H.-J.; Flemming, I.; Drastig, K. Effects of Drought and Heat on Photosynthetic Performance, Water Use and Yield of Two Selected Fiber Hemp Cultivars at a Poor-Soil Site in Brandenburg (Germany). Agronomy 2020, 10(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, M.; Ajdanian, L. Screening of different Iranian ecotypes of cannabis under water deficit stress. Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Tejero, I.; Duran Zuazo, V.; Pérez-Álvarez, R.; Hernández, A.; Casano, S.; Morón, M.; Muriel-Fernández, J. Impact of plant density and irrigation on yield of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) in a Mediterranean semi-arid environment. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology 2014, 16(4), 887–895. [Google Scholar]

- Bahador, M.; Tadayon, M. R. Investigating of zeolite role in modifying the effect of drought stress in hemp: Antioxidant enzymes and oil content. Industrial crops and products 2020, 144, 112042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.-F. H.; El-Nady, M. F. Physio-anatomical responses of drought stressed tomato plants to magnetic field. Acta Astronautica 2011, 69(7-8), 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A. R.; Loveys, B. R.; Cowley, J. M.; Hall, T.; Cavagnaro, T. R.; Burton, R. A. Physiological and morphological responses of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) to water deficit. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 187, 115331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, D.; Dixon, M.; Zheng, Y. Increasing Inflorescence Dry Weight and Cannabinoid Content in Medical Cannabis Using Controlled Drought Stress. HortScience 2019, 54(5), 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanney, C. A. S.; Backer, R.; Geitmann, A.; Smith, D. L. Cannabis Glandular Trichomes: A Cellular Metabolite Factory. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 721986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.; Lata, H.; ElSohly, M. A.; Walker, L. A.; Potter, D. Cannabis cultivation: Methodological issues for obtaining medical-grade product. Epilepsy Behav 2017, 70 (Pt B), 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Fernando, D.; Daniel, G.; Madsen, B.; Meyer, A. S.; Ale, M. T.; Thygesen, A. Effect of harvest time and field retting duration on the chemical composition, morphology and mechanical properties of hemp fibers. Industrial Crops and Products 2015, 69, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meijer, E. P.; Bagatta, M.; Carboni, A.; Crucitti, P.; Moliterni, V. C.; Ranalli, P.; Mandolino, G. The inheritance of chemical phenotype in Cannabis sativa L. Genetics 2003, 163(1), 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Sharma, "Altidunal variation in leaf epidermal patterns of Cannabis sativa,". Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 1975, 102(4), 199–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris M, B. F. , Cosson L. The Constituents of Cannabis sativa Pollen. Economic Botany 1975, 29(3), 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Hakim, Y. E. Kheir, and M. Mohamed, "Effect of the climate on the content of a CBD-rich variant of cannabis,". Fitoterapia 1987, 57 (4), 239-241.

- Murari, G.; Lombardi, S.; Puccini, A.; Sanctis, R. d. Influence of environmental conditions on tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-TCH) in different cultivars of Cannabis sativa L. Fitoterapia 1984, 5, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Nakawuka, P.; Peters, T. R.; Gallardo, K. R.; Toro-Gonzalez, D.; Okwany, R. O.; Walsh, D. B. Effect of Deficit Irrigation on Yield, Quality, and Costs of the Production of Native Spearmint. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering 2014, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.; Shekoofa, A.; Walker, E.; Kelly, H. Physiological screening for drought-tolerance traits among hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) cultivars in controlled environments and in field. Journal of Crop Improvement 2021, 35(6), 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baher, Z. F.; Mirza, M.; Ghorbanli, M.; Bagher Rezaii, M. The influence of water stress on plant height, herbal and essential oil yield and composition in Satureja hortensis L. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 2002, 17(4), 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. H.; Pauli, C. S.; Gostin, E. L.; Staples, S. K.; Seifried, D.; Kinney, C.; Vanden Heuvel, B. D. Effects of short-term environmental stresses on the onset of cannabinoid production in young immature flowers of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). J Cannabis Res 2022, 4(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, J. A.; Smart, L. B.; Smart, C. D.; Stack, G. M.; Carlson, C. H.; Philippe, G.; Rose, J. K. C. Limited effect of environmental stress on cannabinoid profiles in high-cannabidiol hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13(10), 1666–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G. W. Effects of drought stress on floral hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) agricultural systems. Auburn University, 2023.

- V. Butsic and J. C. Brenner, "Cannabis ( Cannabis sativa or C. indica) agriculture and the environment: a systematic, spatially-explicit survey and potential impacts," Environmental Research Letters 2016, vol. 11, no. 4. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Da Cunha Leme Filho et al., "Biochemical and physiological responses of Cannabis sativa to an integrated plant nutrition system," Agronomy Journal, 2020, vol. 112, no. 6, pp. 5237-5248. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).