3.1. GrAImes Evaluation of Human Written Microfictions by Literature Scholars

GrAImes was used by literary experts who hold a PhD in Literature, teach at both undergraduate and graduate levels, and are all Spanish speakers, although for one of them, it is not their mother tongue. We selected six microfictions written in Spanish and provided them to the experts along with the fifteen questions from our evaluation protocol. The six microfictions included two written by a well-known author with published books (MF 1 and 2), two by an author who has been published in magazines and anthologies (MF 3 and 6), and two by an emerging writer (MF 4 and 5).

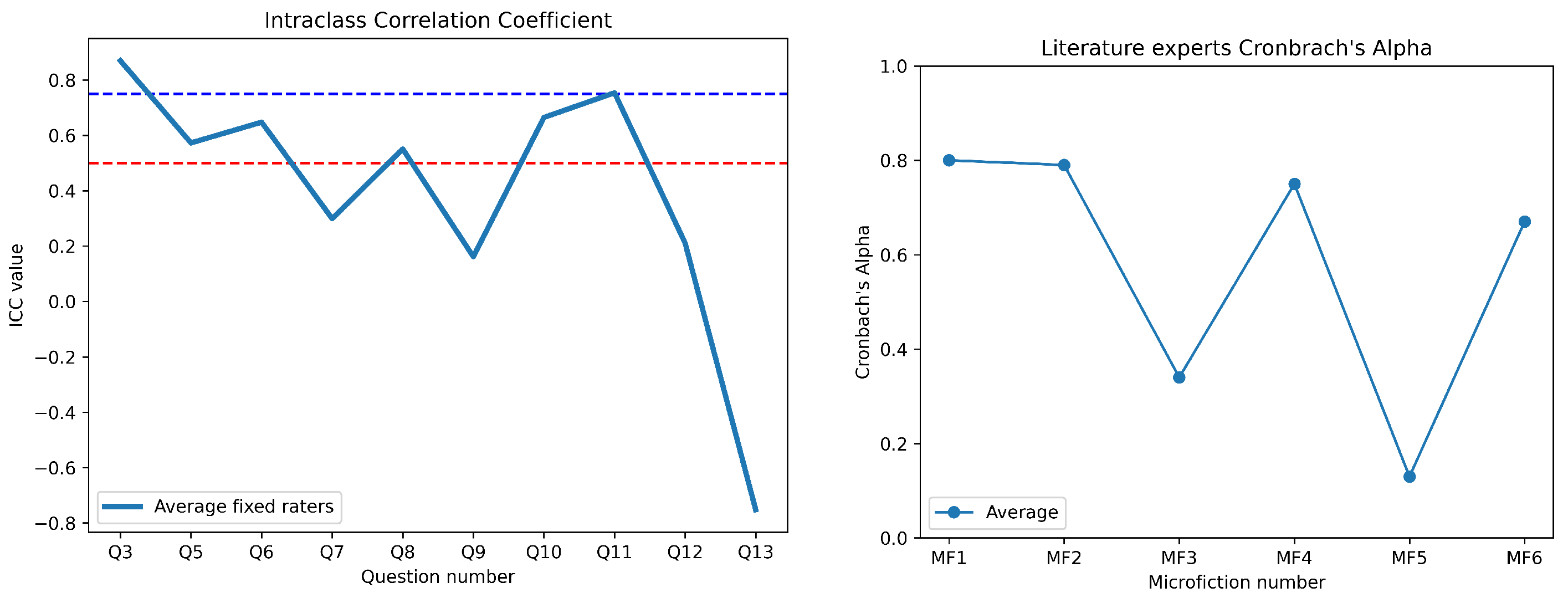

From the responses obtained and displayed in

Table 3 and

Table 4, we conclude that literary experts rated the microfictions (1 and 2) written by a published author higher. However, the responses show a high standard deviation, indicating that while the evaluations were generally positive, there was significant variation among the experts. Additionally, the lowest-ranked microfictions (3 and 6), which have a lower response average, also exhibit a lower standard deviation, suggesting greater agreement among the judges. These texts were written by authors published in literary magazines or by small-scale editorial presses with limited book printings.

The results suggest a direct correlation between author expertise and the internal consistency of the texts. The microfictions authored by an expert (MF 1 and MF 2) exhibited the highest Alpha values, 0.8 and 0.79, respectively, indicating good to acceptable internal consistency (see

Table 5 and

Figure 3). This suggests that expert authors produce more coherent and internally consistent texts, aligning with previous findings that associate higher expertise with structured and logically connected writing.

Microfictions written by authors with medium experience (MF 4 and MF 6) displayed Alpha values of 0.75 and 0.67, respectively, which fall within the acceptable to questionable range. While these microfictions maintained moderate internal consistency, they exhibited higher standard deviations (SD = 1 and SD = 1.1) compared to the expert-written microfictions. This could imply a more varied use of language structures or inconsistencies in the plot, likely due to the intermediate skill level of the authors.

Conversely, texts written by authors with low expertise (MF 3 and MF 5) demonstrated the lowest internal consistency, with Alpha values of 0.34 and 0.13, respectively. These values are classified as unacceptable, suggesting significant inconsistencies within the text. The standard deviation (SD = 0.9 for both) was lower than that of the expert and medium-experience authors, which may indicate a lack of variability in linguistic structures or a rigid, less developed writing style. The low consistency of these texts highlights the challenges faced by less experienced authors in maintaining logical coherence and plot story structure.

Additionally, the average values (AV) of the microfictions provide further insight. Expert-authored texts had the highest AV (3 and 3.1), followed by medium-experience authors (2.5 and 2.4), while low-experience authors scored the lowest (2 and 2.9). This pattern reinforces the idea that writing expertise influences not only internal consistency but also the overall quality perception of the text.

These findings align with existing research [

69] on the relationship between writing expertise and text coherence. Higher expertise leads to better-structured, logically consistent texts, whereas lower expertise results in fragmented, inconsistent writing. The judges rated microfictions written by a more experienced author higher and those written by a starting author lower. This is consistent with the purpose of our evaluation protocol, which aims to provide a tool for quantifying and qualifying a text based on its literary purpose as a microfiction.

Among the evaluated questions (see

Table 2 Likert answer column), Question 3 exhibited the highest ICC (0.87), indicating excellent reliability and strong agreement among respondents. Its relatively high average score (AV = 3.5) and moderate standard deviation (SD = 1) suggest that participants consistently rated this question favorably. Similarly, Question 11 (ICC = 0.75) demonstrated good reliability, although its AV (2.4) was lower, suggesting that respondents agreed on a more moderate evaluation of the item, see

Table 5.

Moderate reliability was observed in Questions 10 and 6, with ICC values of 0.67 and 0.65, respectively. Their AV scores (3.6 and 3.4) suggest that they were generally well-rated, but the higher standard deviation of Question 10 (SD = 1.7) indicates a greater spread of responses, potentially due to varying interpretations or differences in respondent perspectives. Questions 5 and 8, with ICC values of 0.57 and 0.55, respectively, fall into the questionable reliability range. Notably, Question 8 had the lowest AV (1.8), indicating that respondents found it more difficult or unclear, which may have contributed to the reduced agreement among responses.

In contrast, Questions 7, 12, and 9 exhibited low ICC values (0.29, 0.21, and 0.16, respectively), suggesting weak reliability and higher response variability. The AV values for these items ranged from 2.2 to 2.3, further indicating inconsistent interpretations among participants. The standard deviations for these questions (SD = 1.1–1.4) suggest a broad range of opinions, reinforcing the need for potential revisions to improve clarity and consistency.

A particularly notable finding is the negative ICC value for Question 13 (-0.72). Negative ICC values typically indicate systematic inconsistencies, which may stem from ambiguous wording, multiple interpretations, or flaws in question design. With an AV of 2.0 and an SD of 1.2, it is evident that responses to this item lacked coherence.

Regarding the responses to the 5 open answer questions (see numbers 1, 2, 4, 14 and 15 in

Table 2) we used Sentence-BERT [

70], and semantic cosine similarity [

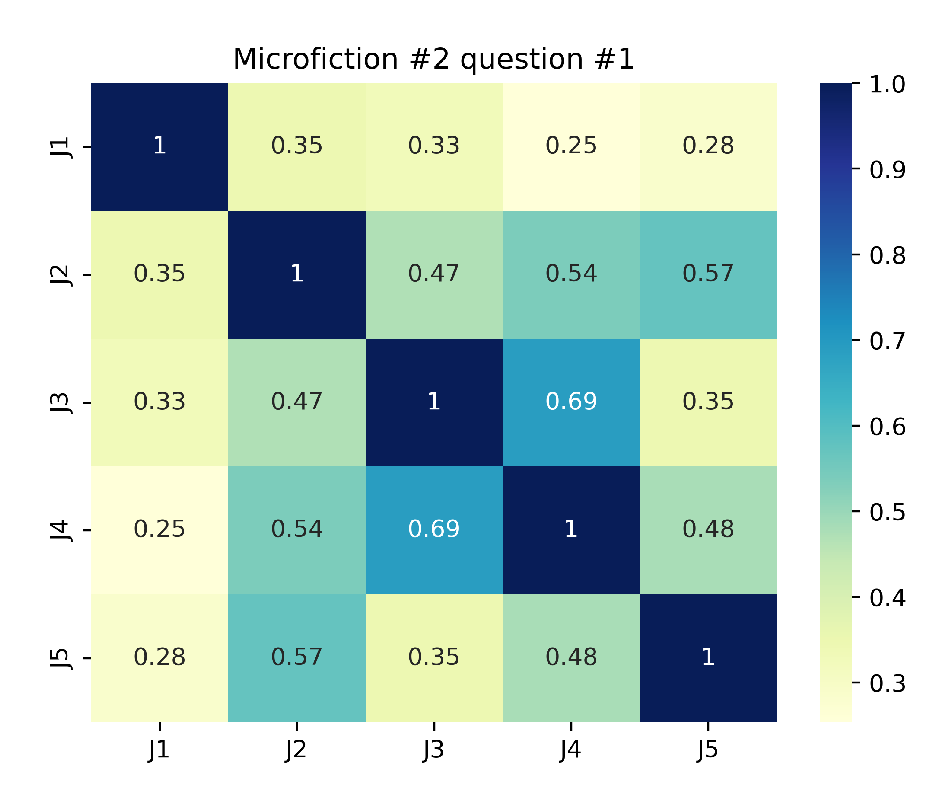

71], these reveal key insights into judge agreement and interpretation variability across the six microfictions. For Question 1 (plot comprehension), agreement was often weak (e.g., J1-J4 semantic cosine similarity = 0.21 in Microfiction 1), suggesting narrative ambiguity or divergent reader focus. Question 2 (theme identification) showed inconsistent alignment (e.g., J2-J3 similarity = 0.67 in Microfiction 2 vs. J1-J3 = 0.10 in Microfiction 1, see

Figure 4), indicating subjective thematic interpretation. Question 4 (interpretation specificity) had polarized responses, with perfect agreement in some cases (e.g., J1-J2 = 1.00 in Microfiction 3) but stark divergence in others (J2-J3 = 0.00 in Microfiction 4), reflecting conceptual or terminological disparities. Questions 14 (gifting suitability) and 15 (publisher alignment) demonstrated higher consensus (e.g., perfect agreement among four judges in Microfiction 4, Q4), likely due to more objective criteria. However, J5 consistently emerged as an outlier (e.g., similarity ≤ 0.11 in Microfiction 1, Question 15), underscoring individual bias. The protocol’s value lies in quantifying these disparities: clearer questions (14-55) reduced variability, while open-ended ones (1-2) highlighted the need for structured guidelines to mitigate judge-dependent subjectivity, particularly in ambiguous or complex microfictions.

On the two extra questions given to the literary experts (see

Section 2.1), the majority of experts (3 out of 5) found the microfiction evaluation protocol sufficiently clear for use, while a minority (2 out of 5) expressed concerns regarding ambiguous or unclear criteria. A strong consensus (4 out of 5 experts) agreed that the protocol can effectively evaluate the literary value of microfiction. However, one dissenting opinion highlights the need for adjustments in specific criteria to ensure a more precise assessment.

3.2. GrAImes Evaluation of Monterroso and ChatGPT-3.5 Generated Microfictions, Evaluated by Intensive Literature Readers

GrAImes was applied to assess a collection of six microfictions crafted by advanced AI tools. These tools include the renowned short story creator inspired by the style of renowned Guatemalan author Augusto Monterroso, and ChatGPT-3.5. The literary enthusiasts who participated in this study evaluated the microfictions based on parameters such as coherence, thematic depth, stylistic originality, and emotional resonance.

A total of six microfictions were generated, with three created by the Monterroso tool (MF = 1, 2, 3) and three by a chatbot (MF = 4, 5, 6). The microfictions were evaluated on a Likert scale of 1 to 5, with ratings provided by a panel 16 reader enthusiasts. The average (AV) and standard deviation (SD) of ratings were calculated for each microfiction. The results of the analysis are presented in

Table 6.

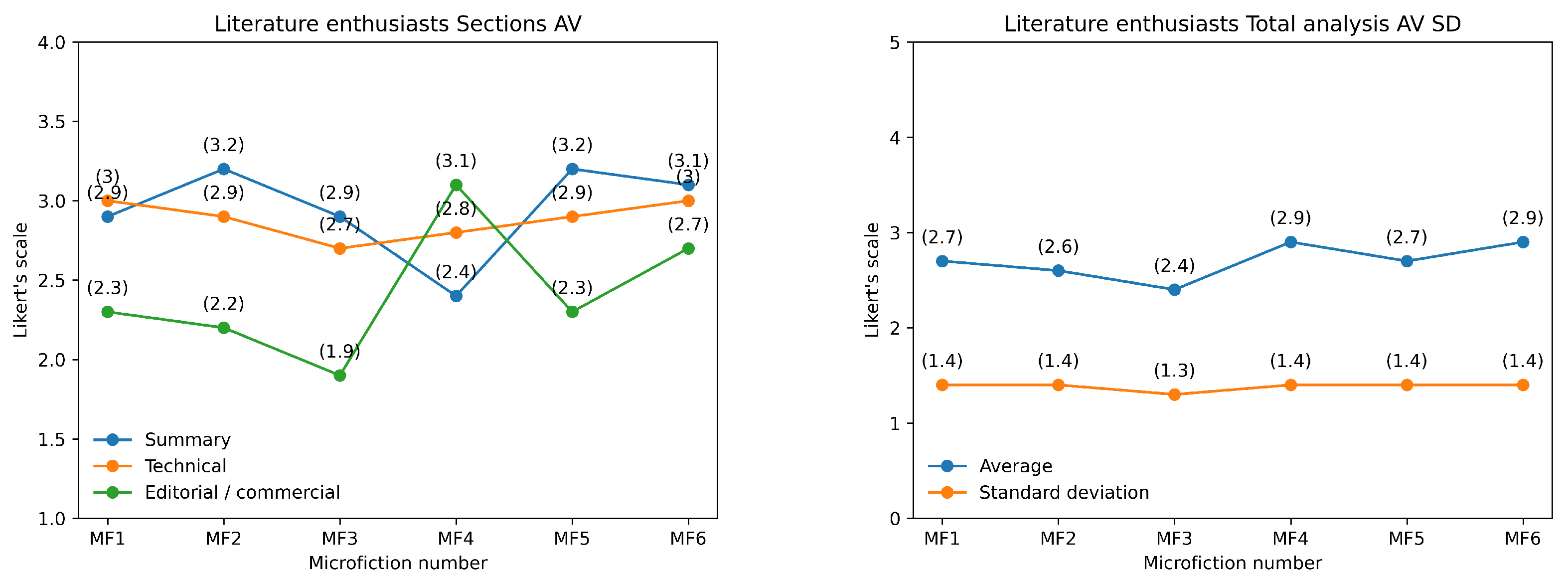

The results indicate that the ChatGPT-3.5 microfictions (MF = 4, 5, 6) have slightly higher average ratings (2.7-2.9) compared to the Monterroso-generated microfictions (MF = 1, 2, 3), which have average ratings ranging from 2.4 to 2.7 (see

Table 7 and

Figure 5). The standard deviation values are consistent across most microfictions, indicating a relatively narrow range of ratings.

The most consistent response pertains to the credibility of the stories (AV = 3.1, SD = 1.0), indicating a strong agreement among participants that the narratives were believable. This suggests that, regardless of other literary attributes, the microfictions maintain a sense of realism that resonates with readers. The question regarding whether the text requires the reader’s participation or cooperation to complete its form and meaning received the highest average rating (AV = 3.6, SD = 1.3). This suggests that the microfictions engage readers actively, requiring interpretation and involvement to fully grasp their meaning. The relatively low SD indicates moderate consensus on this aspect.

Questions concerning literary innovation—whether the texts propose a new vision of language (AV = 2.7, SD = 1.3), reality (AV = 2.6, SD = 1.4), or genre (AV = 2.4, SD = 1.4)—show moderate variation in responses. This suggests that while some readers perceive novelty in these areas, others do not find the texts particularly innovative. Similarly, the question of whether the texts remind readers of other books (AV = 3.2, SD = 1.4) presents a comparable level of divergence in opinions. The lowest-rated questions relate to the desire to read more texts of this nature (AV = 2.3), the willingness to recommend them (AV = 2.2), and the inclination to gift them to others (AV = 2.1), all with SD = 1.4. These results suggest that while the microfictions may have some engaging qualities, they do not strongly motivate further exploration or endorsement.

Interestingly, the question about whether the texts propose interpretations beyond the literal one received the highest standard deviation (SD = 1.6, AV = 2.9). This indicates significant variation in responses, suggesting that some readers found deeper layers of meaning, while others perceived the texts as more straightforward.

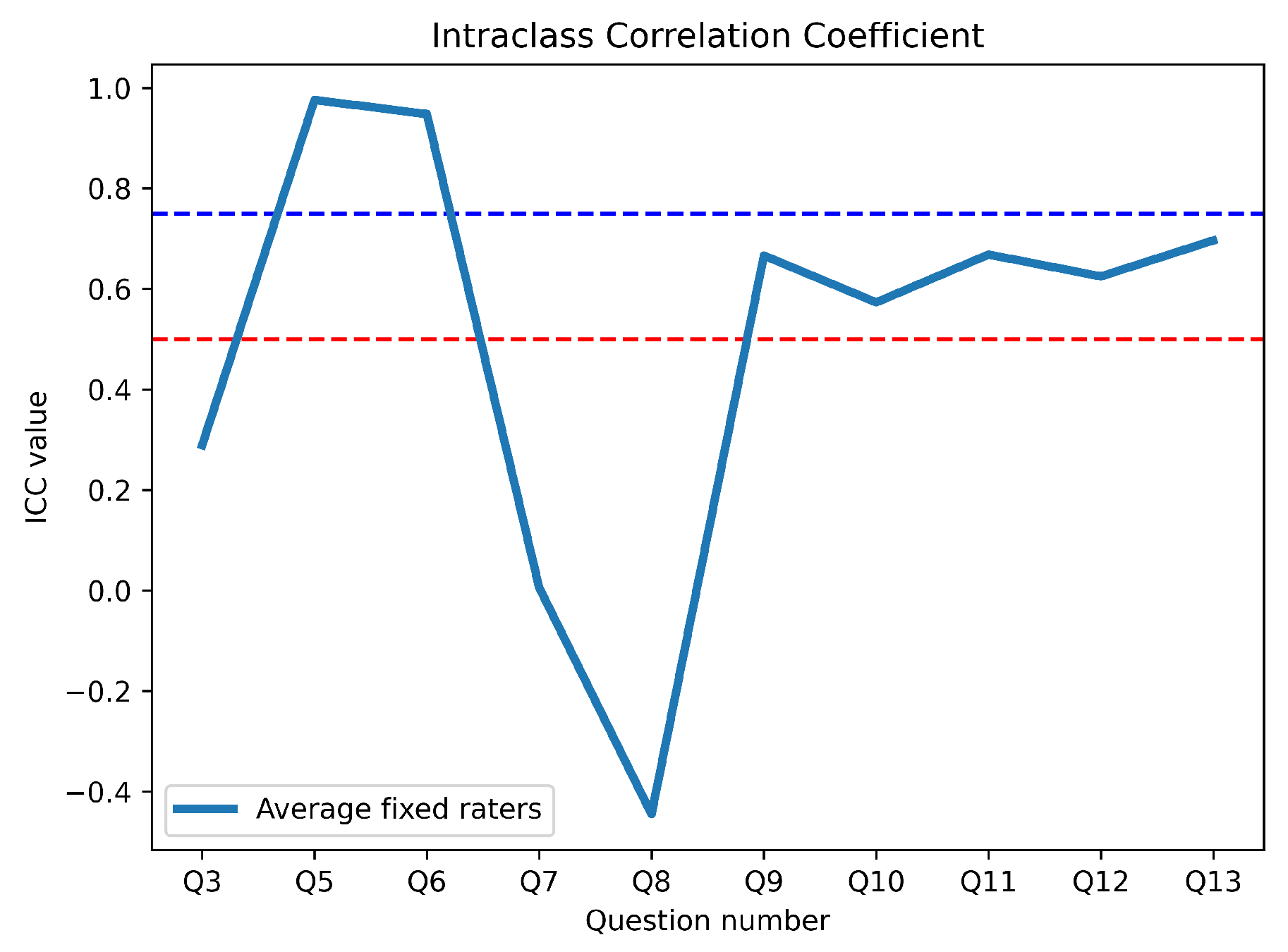

The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) analysis of GrAImes answers (see

Table 8) revealed varying degrees of reliability among the 16 literary enthusiasts raters when assessing texts generated by Monterroso and ChatGPT-3.5. Three questions demonstrated poor reliability (ICC <0.50), reflecting high variability in responses, with Question 8 exhibiting a negative ICC (-0.44), suggesting severe inconsistency, potentially due to misinterpretation or extreme subjectivity. In contrast, Questions 5 and 6 showed excellent reliability (ICC >0.90), indicating strong inter-rater agreement, while Questions 9, 11, 12, and 13 displayed moderate reliability (ICC 0.60–0.70), implying acceptable but inconsistent consensus. These findings highlight the need to refine ambiguous or subjective questions to improve evaluative consistency in microfiction assessment.

The evaluation of microfictions (MFs) based on their ability to propose interpretations beyond the literal meaning (Question 3) revealed notable differences between Monterroso (MF 1–3) and ChatGPT-3.5 (MF 4–6) texts. MF 2, generated by Monterroso, achieved the highest average score (AV = 3.2) in this category, indicating a stronger ability to suggest multiple interpretations. In contrast, MF 4, generated by the ChatGPT-3.5, scored the lowest (AV = 2.4), suggesting limited interpretive depth. The standard deviation (SD) values were relatively consistent across all MFs, ranging from 1.5 to 1.7, indicating moderate variability in responses from literary enthusiasts. This suggests that while some MFs were perceived as more interpretively rich, the variability in participant responses was similar across all texts.

The technical quality of the MFs was assessed through questions related to credibility (Question 5), reader participation (Question 6), and innovation in reality, genre, and language (Questions 7–9). MF 6, generated by the ChatGPT-3.5, scored highest in credibility (AV = 4.3), while MF 1, generated by Monterroso, scored the lowest (AV = 1.9). This indicates a clear distinction in perceived realism between the two sources, as evaluated by literary enthusiasts. In terms of reader participation, MF 1 scored highest (AV = 4.6), suggesting it effectively engaged readers in completing its form and meaning. However, MF 4 scored the lowest in this category (AV = 2.4), highlighting a potential weakness in ChatGPT-3.5’s generated texts. Innovation in language (Question 9) was highest in MF 1 (AV = 3.4), while MF 5 scored the lowest (AV = 2.4). Overall, the technical quality of MFs generated by Monterroso (MF 1–3) was slightly higher (AV = 2.7–3.0) compared to those generated by the ChatGPT-3.5 (AV = 2.8–3.0), with MF 3 scoring the lowest (AV = 2.7). The consistent SD values (ranging from 0.9 to 1.7) reflect similar levels of variability in responses from literary enthusiasts.

Figure 6.

ICC line chart, literature enthusiasts responsees to AI generated microfictions.

Figure 6.

ICC line chart, literature enthusiasts responsees to AI generated microfictions.

The editorial and commercial appeal of the MFs was evaluated based on their resemblance to other texts (Question 10), reader interest in similar texts (Question 11), and willingness to recommend or gift the texts (Questions 12–13). MF 4, generated by the ChatGPT-3.5, scored highest in resemblance to other texts (AV = 3.9), while MF 2 scored the lowest (AV = 2.8). This suggests that ChatGPT-3.5 generated texts may be more reminiscent of existing literature, as perceived by literary enthusiast. In terms of reader interest, MF 4 also scored highest (AV = 3.0), while MF 3 scored the lowest (AV = 1.7). Similarly, MF 4 was the most recommended (AV = 2.8) and most likely to be gifted (AV = 2.8), indicating stronger commercial appeal compared to Monterroso’s generated texts. Overall, the ChatGPT-3.5’s generated MFs (MF 4–6) outperformed Monterroso’s generated MFs (MF 1–3) in editorial and commercial appeal, with MF 4 achieving the highest average score (AV = 3.1) and MF 3 the lowest (AV = 1.9). The SD values (ranging from 0.9 to 1.7) indicate moderate variability in responses from literary enthusiasts.

The total analysis of the MFs (see Table 10) reveals that ChatGPT-3.5 texts (MF 4–6) generally outperformed Monterroso’s generated texts (MF 1–3) in terms of editorial and commercial appeal, while Monterroso’s texts showed slightly better technical quality. MF 4, generated by the ChatGPT-3.5, achieved the highest overall score (AV = 2.9), while MF 3, generated by Program A, scored the lowest (AV = 2.4). The standard deviation values were consistent across all categories (SD ≈ 1.3–1.4), indicating similar levels of variability in responses from literary enthusiast. These findings suggest that while ChatGPT-3.5 texts may have stronger commercial potential, Monterroso’s texts exhibit slightly higher technical sophistication. The evaluation by literary enthusiasts provides valuable insights into how general audiences perceive and engage with these microfictions.

3.2.1. Literary Experts Responses to GrAImes with Microfictions Generated by Monterroso and ChatGPT-3.5

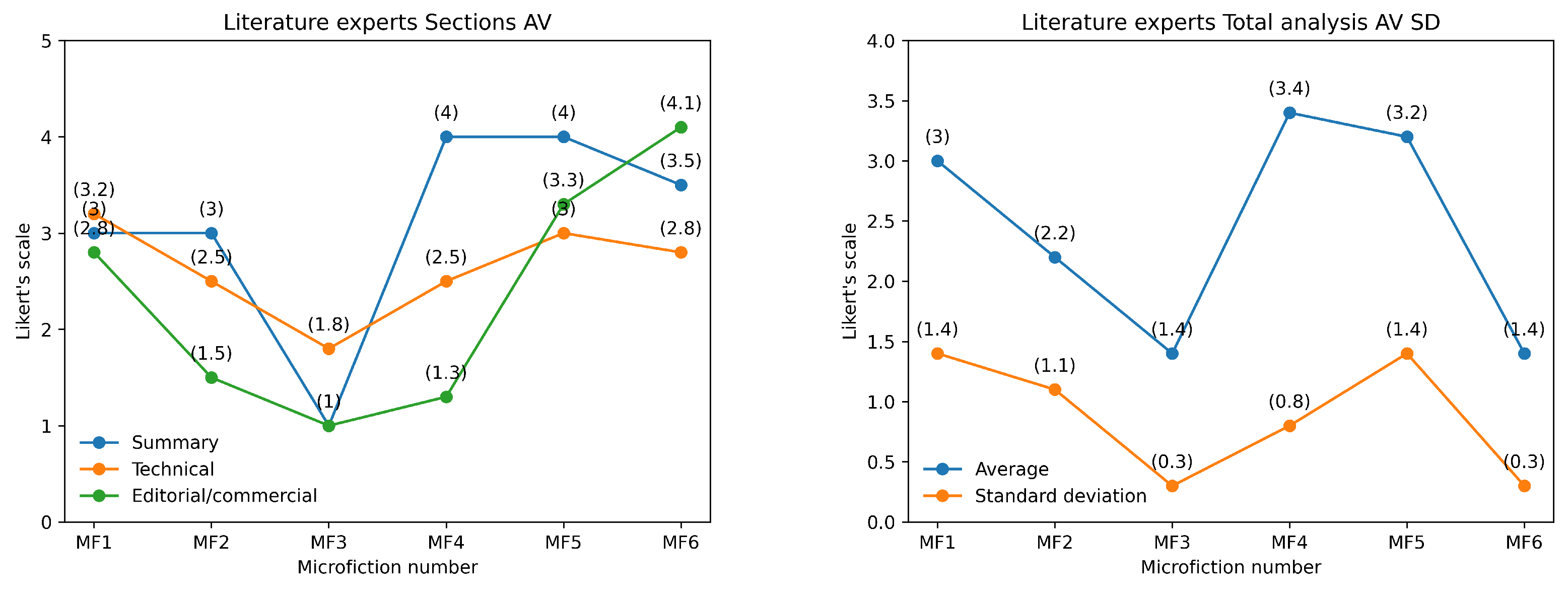

The evaluation of six microfictions (MF) by literary experts, using a Likert scale (1–5), revealed notable differences between microfictions generated by Monterroso (MF 1–3) and those generated by ChatGPT-3.5 (MF 4–6), see

Table 9. In terms of Story Overview, MF 4 and MF 5 scored highest (AV = 4) for proposing multiple interpretations (see

Table 10 and Figure 7), while MF 3 scored the lowest (AV = 1, SD = 0), indicating a lack of depth. The Technical aspects showed that MF 1 and MF 4–6 were rated highly for credibility (AV = 5, SD = 0), whereas MF 3 scored poorly (AV = 2, SD = 1.4). MF 1 and MF 5 excelled in requiring reader participation (AV = 5, SD = 0), while MF 4 and MF 6 scored lower (AV = 3.5, SD = 0.7). However, all microfictions struggled to propose new visions of reality, language, or genre, with most scores ranging between 1 and 2.

In the Editorial/Commercial category, MF 4–6 outperformed MF 1–3. MF 4 and MF 6 were most reminiscent of other texts (AV = 5 and 4.5, respectively) and were more likely to be recommended or given as presents (AV = 4, SD = 1.4). In contrast, MF 1–3 scored poorly in these areas, with MF 3 consistently receiving the lowest ratings (AV = 1, SD = 0). Overall, the ChatGPT-3.5 microfictions (MF 4–6) achieved higher total scores (AV = 3.4, SD = 0.8) compared to those generated by Monterroso (MF 1–3, AV = 2.2, SD = 1.1).

Figure 7.

Line charts of literary experts GrAImes sections summarized AV and SD.

Figure 7.

Line charts of literary experts GrAImes sections summarized AV and SD.

One of the most notable results in this evaluation concerns the interpretative engagement of readers. The highest-rated question,

“Does the text require your participation or cooperation to complete its form and meaning?”, received an average score (

AV) of 4.3 with a standard deviation (

SD) of 0.5. This suggests that the evaluated texts demand significant reader interaction, a crucial trait of literary complexity (see

Table 11). Conversely, aspects related to innovation in language and genre were rated lower. The question

“Does it propose a new vision of the language itself?” obtained an AV of 1.2, the lowest among all items, with an SD of 1.2, indicating high variability in responses. Similarly, the question

“Does it propose a new vision of the genre it uses?” received an AV of 1.6 and an SD of 0.6, further emphasizing the experts’ perception that the generated texts do not significantly redefine literary conventions. Regarding textual credibility, the question

“Is the story credible?” was rated highly, with an AV of 4.2 and an SD of 0.7. This suggests that the narratives effectively maintain believability, an essential criterion for reader immersion. Additionally, evaluators were asked whether the texts reminded them of other literary works, yielding an AV of 3.4 and an SD of 0.8, indicating a moderate level of intertextuality. GrAImes also examined subjective aspects of reader appreciation. The questions

“Would you recommend it?” and

“Would you like to read more texts like this?” received AV scores of 2.7 and 2.8, respectively, with higher SD values (1.4 and 1.6), reflecting diverse opinions among experts. Similarly, the willingness to offer the text as a gift scored an AV of 2.3 with an SD of 0.9, suggesting a moderate level of appreciation but not strong endorsement.