Submitted:

19 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Endometriosis

2.1. Genetic and Epigenetic Changes in Endometriosis

2.2. Extracellular Vesicles

2.3. Microbiota and Endometriosis

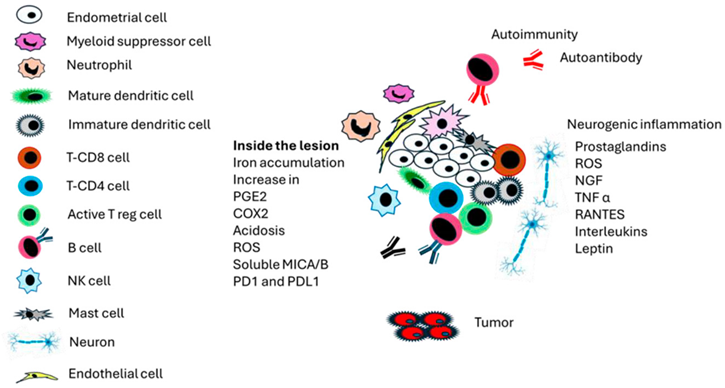

3. Immune Response in Endometriosis

3.1. Pattern-Recognition Receptors (PRR), Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMP), Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMP), and Endometriosis

3.2. Innate Immune Response in Endometriosis

4. Cytokines and Endometriosis

5. Mechanisms of Pain in Endometriosis

6. Endometriosis and Autoimmunity

7. Immunological Therapies in Endometriosis

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/endometriosis. Accessed April 7, 2025.

- Tsamantioti, E.S.; Mahdy H. Endometriosis. [Updated 2023 Jan 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567777/.

- Smolarz, B.; Szyłło, K.; Romanowicz, H. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis, treatment and genetics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:10554. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Chapron, C.; Giudice, L.C.; Laufer, M.R.; Leyland, N.; Missmer, S.A.; Singh, S.S.; Taylor, H.S. Clinical Diagnosis of Endometriosis: A Call to Action. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(4):354.e1-354.e12. [CrossRef]

- Park, W.; Lim, W.; Kim, M.; Jang, H.; Park, S.J.; Song, G.; Park, S. Female reproductive disease, endometriosis: From inflammation to infertility. Mol Cells. 2025;48(1):100164. [CrossRef]

- Simoens, S.; Dunselman, G.; Dirksen, C.; Hummelshoj, L.; Bokor, A.; Brandes, I.; et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1292-9. [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, R.; Mardon, H.; Barlow, D.; Kennedy, S. Delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a survey of women from the USA and the UK. Human reproduction, 1996 11(4), 878–880. [CrossRef]

- Swift, B.; Taneri, B.; Becker, C. M.; Basarir, H.; Naci, H.; Missmer, S. A.; Zondervan, K. T.; Rahmioglu, N. Prevalence, diagnostic delay and economic burden of endometriosis and its impact on quality of life: results from an Eastern Mediterranean population. Eur J Public Health, 2024 34(2), 244–252. [CrossRef]

- Tariverdian, N.; Siedentopf, F.; Rücke, M.; Blois, S.M.; Klapp, B.F.; Kentenich, H.; Arck, P.C. Intraperitoneal immune cell status in infertile women with and without endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;80(1-2):80-90. [CrossRef]

- Amidifar, S.; Jafari, D.; Mansourabadi, A.H.; Sadaghian, S.; Esmaeilzadeh, A. Immunopathology of Endometriosis, Molecular Approaches. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2025 Mar;93(3):e70056. PMID: 40132064. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, S.; Tang, W.; Zhang, B. LncRNA HOTAIR regulates cell invasion and migration in endometriosis through miR-519b-3p/PRRG4 pathway. Front Oncol. 2022;12:953055. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, L.P.; Salmeri, N.; Temkin, S.M.; Shanmugam, V.K.; Stratton, P. Endometriosis and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2025 Mar 26;24(4):103752. [CrossRef]

- Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(5):261-75. [CrossRef]

- Gordts S.; Koninckx P.; Brosens I. Pathogenesis of deep endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):872-885.e1. [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lin, R.; Mo, T.; Li, S.; Cao, Y.; Yin, T.; Diao, L.; Li, Y. Endometriosis: A new perspective on epigenetics and oxidative stress. J Reprod Immunol, 2025; 169, 104462. [CrossRef]

- Laganà, A.S.; Garzon, S.; Götte, M.; Viganò, P.; Franchi, M.; Ghezzi, F.; Martin, D.C. The Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: Molecular and Cell Biology Insights. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5615. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nicholes K, Shih IM. The Origin and Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2020 Jan 24;15:71-95. [CrossRef]

- Bo, C.; Wang, Y. Angiogenesis signaling in endometriosis: Molecules, diagnosis and treatment (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2024;29(3):43. [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Zarchi, M.; Dehshiri-Zadeh, N.; Sekhavat, L.; Nosouhi, F. Correlation of CA-125 serum level and clinico-pathological characteristic of patients with endometriosis. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14(11):713-718.

- Neves, D.; Neto, A.C.; Salazar, M.; Fernandes, A.S.; Martinho, M.; Charrua, A.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Gouveia, A.M,; Almeida, H. A narrative review about the intricate crosstalk among endometrium, adipose tissue, and neurons in endometriosis. The multifaceted role of leptin. Obes Rev. 2025 Apr;26(4):e13879. [CrossRef]

- Abulughod, N.; Valakas, S.; El-Assaad, F. Dietary and Nutritional Interventions for the Management of Endometriosis. Nutrients, 2024; 16(23), 3988. [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, R.M.; Kim, T.H.; Shin, J.H.; Jeong, J.W. Progesterone and Estrogen Signaling in the Endometrium: What Goes Wrong in Endometriosis? Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Aug 5;20(15):3822. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, J.R.; Jee, B.C. Management of endometriosis-related infertility: Considerations and treatment options. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2020;47(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, E.; Vázquez-Martínez, E.R.; Reyes-Mayoral, C.; Cruz-Orozco, O.P.; Camacho-Arroyo, I.; Cerbón, M. Regulation of Inflammation Pathways and Inflammasome by Sex Steroid Hormones in Endometriosis. Front Endocrinol 2020;10:935. [CrossRef]

- Rolla, E. Endometriosis: advances and controversies in classification, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-529. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, T. P.; Andres, M. P.; Carmona, F.; Baracat, E. C.; Abrão, M. S. Deep Endometriosis: the Involvement of Multiple Pelvic Compartments Is Associated with More Severe Pain Symptoms and Infertility. Reprod Sci, 2023; 30(5), 1668–1675. [CrossRef]

- Camboni, A.; Marbaix, E. Ectopic Endometrium: The Pathologist's Perspective. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22(20), 10974. [CrossRef]

- Istrate-Ofiţeru, A.M.; Berbecaru, E.I.; Zorilă, G.L.; Roşu, G.C.; Dîră, L.M.; Comănescu, C.M.; et al Specific Local Predictors That Reflect the Tropism of Endometriosis-A Multiple Immunohistochemistry Technique. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(10):5614. [CrossRef]

- Moraru, L.; Mitranovici, M.I.; Chiorean, D.M.; Moraru, R.; Caravia, L.; Tirón, A.T.; Cotoi, O.S. Adenomyosis and Its Possible Malignancy: A Review of the Literature. Diagnostics. 2023 May 28;13(11):1883. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, G.; Jiang, H.; Dai, H.; Li, D.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, K.; Shen, H.; Xu, H.; Li, S. ITGB3 promotes cisplatin resistance in osteosarcoma tumors. Cancer Med. 2023 Apr;12(7):8452-8463. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Kong, Z.; Wang, B.; Cheng, W.; Wu, A.; Meng, X. ITGB3/CD61: a hub modulator and target in the tumor microenvironment. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(12):7195-7208.

- Zhang, L.; Shao, W.; Li, M.; Liu, S. ITCH-Mediated Ubiquitylation of ITGB3 Promotes Cell Proliferation and Invasion of Ectopic Endometrial Stromal Cells in Ovarian Endometriosis. Biomedicines, 2023; 11(9), 2506. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, G. Endometriosis-associated Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma: A Special Entity? J Cancer. 2021;12(22):6773-6786. [CrossRef]

- Giannini, A.; Massimello, F.; Caretto, M.; Cosimi, G.; Mannella, P.; Luisi, S.; Gadducci, A.; Simoncini, T. Factors in malignant transformation of ovarian endometriosis: A narrative review. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2024; 40(1), 2409911. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Kotani, Y.; Nakai, H.; Matsumura, N. Endometriosis-Associated Ovarian Cancer: The Origin and Targeted Therapy. Cancers. 2020;12(6):1676. [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, V.A.; Scarpelli, E.; dell'Omo, S.; Rolla, M.; Pezzani, A.; Morganelli, G.; Gaiano, M.; Ghi, T.; Berretta, R. Atypical Endometriosis: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Pathological Patterns and Diagnostic Challenges. Biomedicines. 2024;12(6):1209. [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Lin, M.; Hu, K.L.; Li, R. Cross-Tissue Regulatory Network Analyses Reveal Novel Susceptibility Genes and Potential Mechanisms for Endometriosis. Biology (Basel). 2024;13(11):871. [CrossRef]

- Nyholt, D.R.; Low, S.K.; Anderson, C.A.; Painter, J.N.; Uno, S.; Morris, A.P.; et el. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies new endometriosis risk loci. Nat Genet. 2012;44(12):1355-9. [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.C.; Kim, C, E.; Garcia-Alonso, L.; Vento-Tormo, R. The human endometrium: atlases, models, and prospects. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2025 Mar 26;92:102341. [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Xu, X.; Gong, C.; Lin, B.; Li, F. Integrated analysis of genome-wide gene expression and DNA methylation profiles reveals candidate genes in ovary endometriosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023; 14, 1093683. [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.C.; Chen, C.H.; Chen, M.J.; Chang, C.W.; Chen, P.H.; Yu, M.H.; et al. Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) and human leukocyte antigen-C (HLA-C) allorecognition patterns in women with endometriosis. Sci Rep. 2020 Mar 17;10(1):4897. [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.L.C.; Coelho, V.; Visentainer, J.E.L.; Alves, H.V.; Köhler, K.F.; Rached, M.R.; Abrão, M.S.; Kalil, J. Inhibitory KIR2DL2 Gene: Risk for Deep Endometriosis in Euro-descendants. Reprod Sci. 2021;28(1):291-304. [CrossRef]

- Kitawaki, J.; Xu, B.; Ishihara, H.; Fukui, M.; Hasegawa, G.; Nakamura, N; et al. Association of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor genotypes with susceptibility to endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58(6):481-6. [CrossRef]

- Kula, H.; Balbal, B.; Timur, T.; Yalcın, P.; Yavuz, O.; Kızıldag, S.; Ulukus, E. C.; Posaci, C. NOD1, NOD2, PYDC1, and PYDC2 gene polymorphisms in ovarian endometriosis. Front. Med., 2025; 11, 1495002. [CrossRef]

- Badie, A.; Saliminejad, K.; Salahshourifar, I.; Khorram Khorshid, H. R. Interleukin 1 alpha (IL1A) polymorphisms and risk of endometriosis in Iranian population: a case-control study. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2020; 36(2), 135–138. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Q.; Hu, M.; Chen, J. M.; Sun, W.; Zhu, M. B. Effects of gene polymorphism and serum levels of IL-2 and IL-6 on endometriosis. Europ Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2020; 24(9), 4635–4641. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Liang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wei, L. Association between polymorphisms of cytokine genes and endometriosis: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Reprod Immunol. 2023 Aug;158:103969. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Kang, S. A functional promoter polymorphism in interleukin 12B gene is associated with an increased risk of ovarian endometriosis. Gene, 2018; 666, 27–31. [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Hesampour, F.; Poordast, T.; Valibeigi, M.; Enayatmehri, M.; Ahmadi, S.; Nasri, F.; Gharesi-Fard, B. Association between gene polymorphisms of IL-12, IL-12 receptor and IL-27 and organ involvement in Iranian endometriosis patients. Inter J Immun, 2023; 50(1), 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Watrowski, R.; Schuster, E.; Van Gorp, T.; Hofstetter, G.; Fischer, M.B.; Mahner, S.; Polterauer, S.; Zeillinger, R.; Obermayr, E. Association of the Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms rs11556218, rs4778889, rs4072111, and rs1131445 of the Interleukin-16 Gene with Ovarian Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Sep 24;25(19):10272. [CrossRef]

- Babah, O. A.; Ojewunmi, O. O.; Onwuamah, C. K.; Udenze, I. C.; Osuntoki, A. A.; Afolabi, B. B. Serum concentrations of IL-16 and its genetic polymorphism rs4778889 affect the susceptibility and severity of endometriosis in Nigerian women. BMC women's health, 2023; 23(1), 253. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z;, Ding, X.; Wang, Y;, Zhang, M. The rs2275913 polymorphism of the interleukin-17A gene is associated with the risk of ovarian endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol 2023; 43(1), 2199852. [CrossRef]

- Balunathan, N.; Rani, G. U.; Perumal, V.; Kumarasamy, P. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of Interleukin - 4, Interleukin-18, FCRL3 and sPLA2IIa genes and their association in pathogenesis of endometriosis. Molecular Biology Rep, 2023; 50(5), 4239–4252. [CrossRef]

- Mier-Cabrera, J.; Cruz-Orozco, O.; de la Jara-Díaz, J.; Galicia-Castillo, O.; Buenrostro-Jáuregui, M.; Parra-Carriedo, A.; Hernández-Guerrero, C. Polymorphisms of TNF-alpha (- 308), IL-1beta (+ 3954) and IL1-Ra (VNTR) are associated to severe stage of endometriosis in Mexican women: a case control study. BMC women's health, 2022; 22(1), 356. [CrossRef]

- Chekini, Z.; Poursadoughian Yaran, A.; Ansari-Pour, N.; Shahhoseini, M.; Ramazanali, F.; Aflatoonian, R.; Afsharian, P. A novel gene-wide haplotype at the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) locus is associated with endometrioma. Europ J Obst, Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2020; 247, 6–9. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J. V.; Machado, D. E.; da Silva, M. C.; de Mello, M. P.; Berardo, P. T.; Medeiros, R.; Perini, J. A. Influence of interleukin-8 polymorphism on endometriosis-related pelvic pain. Human immunology, 2023 84(10), 561–566. [CrossRef]

- Anglesio, M.S.; Bashashati, A.; Wang, Y.K.; Senz, J.; Ha, G.; Yang, W.; Aniba, M.R.; et al. . Multifocal endometriotic lesions associated with cancer are clonal and carry a high mutation burden. J Pathol. 2015;236(2):201-9. [CrossRef]

- Wilbur, M.A.; Shih, I.M.; Segars, J.H.; Fader, A.N. Cancer Implications for Patients with Endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35(1):110-116. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cuellar-Partida, G.; Painter, J.N.; Nyholt, D.R.; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study; International Endogene Consortium (IEC). Shared genetics underlying epidemiological association between endometriosis and ovarian cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(20):5955-64. [CrossRef]

- Parra-Herran, C.; Lerner-Ellis, J.; Xu, B.; Khalouei, S.; Bassiouny, D.; Cesari, M.; Ismiil, N.; Nofech-Mozes, S. Molecular-based classification algorithm for endometrial carcinoma categorizes ovarian endometrioid carcinoma into prognostically significant groups. Mod Pathol. 2017 Dec;30(12):1748-1759. [CrossRef]

- LE, K.N.; Benor, A.; Decherney, A. An update on epigenetic mechanisms in endometriosis. Minerva Obstet Gynecol. 2024 Dec 3. [CrossRef]

- Bulun, S.E.; Yilmaz, B.D.; Sison, C.; Miyazaki, K.; Bernardi, L.; Liu, S.; Kohlmeier, A.; Yin, P.; Milad, M.; Wei, J. Endometriosis. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(4):1048-1079. [CrossRef]

- Raja, M.H.R.; Farooqui, N.; Zuberi, N.; Ashraf, M.; Azhar, A.; Baig, R.; Badar, B.; Rehman, R. Endometriosis, infertility and MicroRNA's: A review. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50(9):102157. [CrossRef]

- Hon, J.X.; Wahab, N.A.; Karim, A.K.A.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Mokhtar, M.H. MicroRNAs in Endometriosis: Insights into Inflammation and Progesterone Resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(19):15001. [CrossRef]

- Azari, Z.D.; Aljubran, F.; Nothnick, W.B. Inflammatory MicroRNAs and the Pathophysiology of Endometriosis and Atherosclerosis: Common Pathways and Future Directions Towards Elucidating the Relationship. Reprod Sci. 2022;29(8):2089-2104. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Tang, S.; Jiang, P.; Geng, T.; Cope, D.I.; Dunn, T.N.; Guner, J.; Radilla, L.A.; Guan, X.; Monsivais, D. Impaired bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathways disrupt decidualization in endometriosis. Commun Biol. 2024 Feb 24;7(1):227. [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, M.; Karimi, M.; Rajaei, S. The landscape of non-coding RNAs in the immunopathogenesis of Endometriosis. Frontiers Immunol, 2023; 14, 1223828. [CrossRef]

- González-Ramos, R.; Van Langendonckt, A.; Defrère, S.; Lousse ,J.C.; Colette, S.; Devoto, L.; Donnez, J. Involvement of the nuclear factor-κB pathway in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):1985-94. [CrossRef]

- Zdrojkowski, Ł.; Jasiński, T.; Ferreira-Dias, G.; Pawliński, B.; Domino, M. The Role of NF-κB in Endometrial Diseases in Humans and Animals: A Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Feb 2;24(3):2901. [CrossRef]

- Vissers, G.; Giacomozzi, M.; Verdurmen, W.; Peek, R.; Nap, A. The role of fibrosis in endometriosis: a systematic review. Human Reproduction Update, 2024; 30(6), 706–750. [CrossRef]

- Almquist, L.D.; Likes, C.E.; Stone, B.; Brown, K.R.; Savaris, R.; Forstein, D.A.; Miller, P.B.; Lessey, B.A. Endometrial BCL6 testing for the prediction of in vitro fertilisation outcomes: a cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2017; 108(6):1063-1069. [CrossRef]

- Saadat Varnosfaderani, A.; Kalantari, S.; Ramezanali, F.; Shahhoseini, M.; Amirchaghmaghi, E. Increased Gene Expression of LITAF, TNF-α and BCL6 in Endometrial Tissues of Women with Endometriosis: A Case-Control Study. Cell J. 2024;26(4):243-249. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, S.; Xie, Y.; Tong, Y.; Qi, W.; Wang, Z. Endometrial expression of ERRβ and ERRγ: prognostic significance and clinical correlations in severe endometriosis. Front Endocrinol . 2024;15:1489097. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.W.; Licence, D.; Cook, E.; Luo, F.; Arends, M.J.; Smith, S.K.; Print, C.G, Charnock-Jones DS. Activation of mutated K-ras in donor endometrial epithelium and stroma promotes lesion growth in an intact immunocompetent murine model of endometriosis. J Pathol. 2011;224(2):261-9. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, D.; Shih, IeM. Pathogenesis and the role of ARID1A mutation in endometriosis-related ovarian neoplasms. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20(1):45-52. [CrossRef]

- Steinbuch, S,C,; Lüß, A.M.; Eltrop, S.; Götte, M.; Kiesel, L. Endometriosis-Associated Ovarian Cancer: From Molecular Pathologies to Clinical Relevance. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(8):4306. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Pan, C.; Zhang, C. Unraveling the complexity of follicular fluid: insights into its composition, function, and clinical implications. J Ovarian Res. 2024 Nov 26;17(1):237. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Hicks, C.; El-Omar, E.; Combes, V.; El-Assaad, F. The Critical Role of Host and Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in Endometriosis. Biomedicines. 2024 Nov 12;12(11):2585. [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Liu, X.; Duan, J.; Guo, S. W. Platelets are an unindicted culprit in the development of endometriosis: clinical and experimental evidence. Human reproduction. 2015; 30(4), 812–832. [CrossRef]

- Bortot, B.; Di Florio, R.; Merighi, S.; Peacock, B.; Lees, R.; Valle, F.; et al. Platelets as key cells in endometriosis patients: Insights from small extracellular vesicles in peritoneal fluid and endometriotic lesions analysis. FASEB J. 2024 Dec 13;38(24):e70267. [CrossRef]

- Dantzler, M.D.; Miller, T.A.; Dougherty, M.W.; Quevedo, A. The Microbiome Landscape of Adenomyosis: A Systematic Review. Reprod Sci. 2025 Feb;32(2):251-260. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Xu, Z.; Hu, S.; Shen, Y. Exploring Microbial Signatures in Endometrial Tissues with Endometriosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025 Feb 20;148:114072. [CrossRef]

- Qin, R.; Tian, G.; Liu, J.; Cao, L. The gut microbiota and endometriosis: From pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1069557. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, W.; Kang, M.; Ma, J.; Zhao, L. Gut microbial beta-glucuronidase: a vital regulator in female estrogen metabolism. Gut Microbes. 2023;15(1):2236749. [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.M.; Al-Nakkash, L.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. Estrogen-gut microbiome axis: Physiological and clinical implications. Maturitas. 2017;103:45-53. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Song, X.; Wei, W.; Zhong, H.; Dai, J.; Lan, Z.; et al. The microbiota continuum along the female reproductive tract and its relation to uterine-related diseases. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):875. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, X.; Tang, H.; Zeng, L.; Wu, R. Microbiota composition and distribution along the female reproductive tract of women with endometriosis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020;19(1):15. [CrossRef]

- Ata, B.; Yildiz, S.; Turkgeldi, E.; Brocal, V.P.; Dinleyici, E.C.; Moya, A.; Urman, B. The Endobiota Study: Comparison of Vaginal, Cervical and Gut Microbiota Between Women with Stage 3/4 Endometriosis and Healthy Controls. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2204. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, B.; Liu, Z.; Feng, W.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Gut Microbiota Exceeds Cervical Microbiota for Early Diagnosis of Endometriosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:788836. [CrossRef]

- Svensson, A.; Brunkwall, L.; Roth, B.; Orho-Melander, M.; Ohlsson, B. Associations Between Endometriosis and Gut Microbiota. Reprod Sci. 2021;28(8):2367-2377. [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Ni, Z.; Cheng, W.; Zhou, L.; Zhai, D.; Sun, S.; Yu, C. Gut microbiota imbalance and its correlations with hormone and inflammatory factors in patients with stage 3/4 endometriosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;304(5):1363-1373. [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Tian, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, L.; Hou, M. Association Between Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Risk of Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Womens Health, 2024; 33(1), 73–79. [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, J.V.; De Sanctis, C.V.; Hajdúch, M.; De Sanctis, J.B. Microbiota and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss (RPL); More than a Simple Connection. Microorganisms. 2024 Aug 10;12(8):1641. [CrossRef]

- Sobstyl, A.; Chałupnik, A.; Mertowska, P.; Grywalska, E. How Do Microorganisms Influence the Development of Endometriosis? Participation of Genital, Intestinal and Oral Microbiota in Metabolic Regulation and Immunopathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13):10920. [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, M.; Hicks, C.; El-Assaad, F.; El-Omar, E.; Condous, G. Endometriosis and the microbiome: a systematic review. BJOG. 2020;127(2):239-249. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, N.; Norton, T.; Diadala, G.; Bell, E.; Valenti, M.; Farland, L.V.; Mahnert, N.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. Vaginal and rectal microbiome contribute to genital inflammation in chronic pelvic pain. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):283. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, C. Role of the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of endometriosis: a review. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1363455. [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, S.W.; Bonham, K.S.; Zanoni, I.; Kagan, J.C. Innate immune pattern recognition: a cell biological perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:257-90. [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Chen, J.H.; Zhang, J.H.; Fang, Y.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.Q.; Zhan, L. Pattern-recognition receptors in endometriosis: A narrative review. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1161606. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, D.; Han, X.; Ren, Y.; Fan, Y., Zhang, C.; et al. Alarmins and their pivotal role in the pathogenesis of spontaneous abortion: insights for therapeutic intervention. Eur J Med Res. 2024;29(1):640. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Tang, H.; Cai, X.; Lin, J.; Kang, R.; Tang, D.; Liu, J. DAMPs in immunosenescence and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2024;106-107:123-142. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Higashiura, Y.; Shigetomi, H.; Kajihara, H. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: the role of initial infection and subsequent sterile inflammation (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2014;9(1):9-15. [CrossRef]

- Sobstyl, M.; Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej, P.; Grywalska, E.; Korona-Głowniak, I.; Sobstyl, A.; Bednarek, W.; Roliński, J. Toll-Like Receptor 2 Expression as a New Hallmark of Advanced Endometriosis. Cells. 2020;9(8):1813. [CrossRef]

- Noh, E.J.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Han, J.W.; Kim, B.C.; Kim, C.J.; Lee, S.K. Ureaplasma Urealyticum Infection Contributes to the Development of Pelvic Endometriosis Through Toll-Like Receptor 2. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2373. [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo, B. C.; Mansur, F.; Podgaec, S. systematic review of toll-like receptors in endometriosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2021 304(2), 309–316. [CrossRef]

- Almasi, M.Z.; Hosseini, E.; Jafari, R.; Aflatoonian, K.; Aghajanpour, S.; Ramazanali, F.; et al. Evaluation of Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) signaling pathway genes and its genetic polymorphisms in ectopic and eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50(9):102153. [CrossRef]

- Allhorn, S.; Böing, C.; Koch, A.A.; Kimmig, R.; Gashaw, I. TLR3 and TLR4 expression in healthy and diseased human endometrium. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2008;6:40. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Inflammasome activation and regulation: toward a better understanding of complex mechanisms. Cell Discov. 2020;6:36. [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Geng, P.; Wang, S.; Shao, C. Role of Pyroptosis in Endometrial Cancer and Its Therapeutic Regulation. J Inflamm Res. 2024;17:7037-7056. [CrossRef]

- Irandoost, E.; Najibi, S.; Talebbeigi, S.; Nassiri, S. Focus on the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathology of endometriosis: a review on molecular mechanisms and possible medical applications. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2023; 396(4), 621–631. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; Khalaj, K.; Young, S.L.; Lessey, B.A.; Koti, M.; Tayade, C. Immune-inflammation gene signatures in endometriosis patients. Fertil Steril. 2016 Nov;106(6):1420-1431.e7. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, B.M.; Pinto, B.; Costa, L.; Felgueira, E.; Rebelo, I. Increased expression of NLRP3 inflammasome components in granulosa cells and follicular fluid interleukin(IL)-1beta and IL-18 levels in fresh IVF/ICSI cycles in women with endometriosis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2023;40(1):191-199. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M.; Osuka, S.; Muraoka, A.; Hayashi, S.; Bayasula, Kasahara Y.; et al. Effectiveness of NLRP3 Inhibitor as a Non-Hormonal Treatment for ovarian endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2022;20(1):58. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Tian, W.; Lin, A.; Li, M. Blockage of the NLRP3 inflammasome by MCC950 inhibits migration and invasion in adenomyosis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2024;49(4):104319. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, Z.; Peng, X.; Cai, D.; Peng, R., Lin, Y.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated Pyroptosis induce Notch signal activation in endometriosis angiogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2023;574:111952. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zhao, F.; Huang, Q.; Lin, X.; Zhang, S.; Dai, Y. NLRP3 activated macrophages promote endometrial stromal cells migration in endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2022;152:103649. [CrossRef]

- Bergqvist, A.; Bruse, C.; Carlberg, M.; Carlström, K. Interleukin 1beta, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in endometriotic tissue and in endometrium. Fertil Steril. 2001;75(3):489-95. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Xiong, W.; Peng, Y.; Li, X.; Long, Xet al. A novel mechanism regulating pyroptosis-induced fibrosis in endometriosis via lnc-MALAT1/miR-141-3p/NLRP3 pathway. Biol Reprod. 2023;109(2):156-171. [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Fu, X.; Meng, X.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, J. PI3K/AKT signaling pathway associates with pyroptosis and inflammation in patients with endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2024;162:104213. [CrossRef]

- Hang, Y.; Tan, L.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Q.; Jin, Y. E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM24 deficiency promotes NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β-mediated pyroptosis in endometriosis. Cell Biol Int. 2021;45(7):1561-1570. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Jung, S.Y.; Wu, S.P.; Hawkins, S.M.; Park, M.J.; Kyo, S.; et al. Estrogen Receptor β Modulates Apoptosis Complexes and the Inflammasome to Drive the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Cell. 2015;163(4):960-74. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jo, M.; Lee, E.; Kim, S.E.; Lee, D.Y.; Choi, D. Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome by progesterone is attenuated by abnormal autophagy induction in endometriotic cyst stromal cells: implications for endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2022;28(4):gaac007. [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhu, H.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Fang, Y.; Wei, B.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhan, L. NLRC5 exerts anti-endometriosis effects through inhibiting ERβ-mediated inflammatory response. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):351. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Yao, S.; Sun, S.; Su, Q.; Li, J.; Wei, B. NLRC5 and autophagy combined as possible predictors in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(5):949-956. [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Fu, L.; Fan, Y.; Sun, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhan, L.; Shui, L. NLRC5 Inhibits Inflammation of Secretory Phase Ectopic Endometrial Stromal Cells by Up-Regulating Autophagy in Ovarian Endometriosis. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1281. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.G.; Won, Y.S.; Kim, S.H.; Park, DC. Differences in C-type lectin receptors and their adaptor molecules in the peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis and gynecologic cancers. Int J Med Sci. 2018;15(4):411-416. [CrossRef]

- Izumi, G.; Koga, K.; Takamura, M.; Makabe, T.; Nagai, M.; Urata, Y.; Harada, M.; Hirata, T.; Hirota, Y.; Fujii, T.; Osuga, Y. Mannose receptor is highly expressed by peritoneal dendritic cells in endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(1):167-173.e2. [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Mei, J.; Tang, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Li, M.; Zhu, X. 1-Methyl-tryptophan attenuates regulatory T cells differentiation due to the inhibition of estrogen-IDO1-MRC2 axis in endometriosis. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(12):e2489. [CrossRef]

- Sopasi, F.; Spyropoulou, I.; Kourti, M.; Vasileiadis, S.; Tripsianis, G.; Galazios, G.; Koutlaki, N. Oxidative stress and female infertility: the role of follicular fluid soluble receptor of advanced glycation end-products (sRAGE) in women with endometriosis. Hum Fertil. 2023 Dec;26(6):1400-1407. [CrossRef]

- Ajona, D.; Cragg, M.S.; Pio, R. The complement system in clinical oncology: Applications, limitations and challenges. Semin Immunol. 2024; 77:101921. [CrossRef]

- Mastellos, D.C.; Hajishengallis, G.; Lambris, J.D. A guide to complement biology, pathology and therapeutic opportunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024;24(2):118-141. [CrossRef]

- Zeller, J.M.; Henig, I.; Radwanska, E.; Dmowski, W.P. Enhancement of human monocyte and peritoneal macrophage chemiluminescence activities in women with endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol Microbiol. 1987;13(3):78-82. [CrossRef]

- Lousse, J.C.; Defrère, S.; Van Langendonckt, A.; Gras, J.; González-Ramos, R.; Colette, S.; Donnez, J. Iron storage is significantly increased in peritoneal macrophages of endometriosis patients and correlates with iron overload in peritoneal fluid. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(5):1668-75. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Wei, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, X. Peritoneal immune microenvironment of endometriosis: Role and therapeutic perspectives. Front Immunol. 2023; 14:1134663. [CrossRef]

- Lousse, J.C.; Van Langendonckt, A.; González-Ramos, R.; Defrère S, Renkin, E.; Donnez, J. Increased activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kappaB) in isolated peritoneal macrophages of patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(1):217-20. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.H.; Sun, H.S.; Lin, C.C.; Hsiao, K.Y.; Chuang, P.C.; Pan, H.A.; Tsai, S.J. Distinct mechanisms regulate cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 in peritoneal macrophages of women with and without endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8(12):1103-10. [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z. Z.; Yang, H. L.; Ha, S. Y.; Chang, K. K.; Mei, J.; Zhou, W. J.; et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 in Endometriosis. Int J Biol Sci, 2019; 15(13), 2783–2797. [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.W.S.; Lee, C.L.; Ng, E.H.Y.; Yeung, W.S.B. Co-culture with macrophages enhances the clonogenic and invasion activity of endometriotic stromal cells. Cell Prolif. 2017;50(3):e12330. [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Kaponis, A.; Iwabe, T.; Taniguchi, F.; Makrydimas, G;, Sofikitis, N.; Paschopoulos, M.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Terakawa, N. Apoptosis in human endometrium and endometriosis. Human Reprod update, 2004; 10(1), 29–38. [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.; Wang, X.; Chen, L. Regulated Cell Death in Endometriosis. Biomolecules, 2024; 14(2), 142. [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, A.; Rovere-Querini, P. Endometriosis, a disease of the macrophage. Front Immunol. 2013;4:9. [CrossRef]

- Vallvé-Juanico, J.; Santamaria, X.; Vo, K.C.; Houshdaran, S.; Giudice, L.C. Macrophages display proinflammatory phenotypes in the eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis with relevance to an infectious etiology of the disease. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(6):1118-1128. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, Q. J.; Ashjaei, K.; Perricos, A.; Kuessel, L.; Husslein, H.; Wenzl, R.; Yotova, I. Endometriosis Patients Show an Increased M2 Response in the Peritoneal CD14+low/CD68+low Macrophage Subpopulation Coupled with an Increase in the T-helper 2 and T-regulatory Cells. Reprod Sci, 2020: 27(10), 1920–1931. [CrossRef]

- Henlon, Y.; Panir, K.; McIntyre, I.; Hogg, C.; Dhami, P.; Cuff, A. O.; et al. Single-cell analysis identifies distinct macrophage phenotypes associated with prodisease and proresolving functions in the endometriotic niche. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA, 2024 121(38), e2405474121. [CrossRef]

- Laganà, A.S.; Salmeri, F.M.; Ban Frangež, H.; Ghezzi, F.; Vrtačnik-Bokal, E.; Granese, R. Evaluation of M1 and M2 macrophages in ovarian endometriomas from women affected by endometriosis at different stages of the disease. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020;36(5):441-444. [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Guo, S.W. The M2a macrophage subset may be critically involved in the fibrogenesis of endometriosis in mice. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;37(3):254-268. [CrossRef]

- Viganò, P.; Ottolina, J.; Bartiromo, L.; Bonavina, G.; Schimberni, M.; Villanacci, R.; Candiani, M. Cellular Components Contributing to Fibrosis in Endometriosis: A Literature Review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(2):287-295. [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, J.V.; De Sanctis, J.B. A Brief Analysis of Tissue-Resident NK Cells in Pregnancy and Endometrial Diseases: The Importance of Pharmacologic Modulation. Immuno 2021, 1(3), 174-193. doi.org/10.3390/immuno1030011.

- Giuliani, E.; Parkin, K.L.; Lessey, B.A.; Young, S.L.; Fazleabas, A.T. Characterisation of uterine NK cells in women with infertility or recurrent pregnancy loss and associated endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72(3):262-9. [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, J.V.; De Sanctis, C.V.; Hajdúch, M.; De Sanctis, J.B. Exploring the Immunological Aspects and Treatments of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss and Recurrent Implantation Failure. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 Feb 3;26(3):1295. [CrossRef]

- Makoui, M.H.; Fekri, S.; Makoui, R.H.; Ansari, N.; Esmaeilzadeh, A. The Role of Mast Cells in the Development and Advancement of Endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2025 Mar;93(3):e70019. [CrossRef]

- Suszczyk, D.; Skiba, W.; Jakubowicz-Gil, J.; Kotarski, J.; Wertel, I. The Role of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) in the Development and/or Progression of Endometriosis-State of the Art. Cells. 2021;10(3):677. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; He, Y.; Man, G.C.W.; Ding, Y.; Wang, C.C.; Chung, J.P.W. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: A new emerging player in endometriosis. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2023;375:191-220. [CrossRef]

- Satake, E.; Koga, K.; Takamura, M.; Izumi, G.; Elsherbini, M.; Taguchi, A; et al. The roles of polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2021;148:103371. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qin, S.; Lei, A.; Li, X.; Gao, Q.; Dong, J.; Xiao, Q.; Zhou, J. Expansion of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in endometriosis patients: A pilot study. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;47:150-158. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shao, J.; Jiang, F.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Yu, N.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; He, Y. CD33+ CD14+ CD11b+ HLA-DR- monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells recruited and activated by CCR9/CCL25 are crucial for the pathogenic progression of endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2019;81(1):e13067. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, Y.; Guo, P.; Hong, B.; Cao, Y.; Wei, Z.; Xue, R.; Wang, C.; Jiang, H. Alteration of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells, Chronic Inflammatory Cytokines, and Exosomal miRNA Contribute to the Peritoneal Immune Disorder of Patients With Endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2019;26(8):1130-1138. [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Bi, K.; Lu. Z.; Wang, K.; Xu, Y.; Wu, H.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, H. CCR5/CCR5 ligand-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells are related to the progression of endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;39(4):704-711. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, J.; Man, G.C.W.; Leung, K.T.; Liang, B.; Xiao, B.; et al. MDSCs drive the process of endometriosis by enhancing angiogenesis and are a new potential therapeutic target. Eur J Immunol. 2018;48(6):1059-1073. [CrossRef]

- Bosteels, V.; Janssens, S. Striking a balance: new perspectives on homeostatic dendritic cell maturation. Nature Rev Immunol, 2025; 25(2), 125–140. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lin, A.; Qi, L.; Lv, X.; Yan, S.; Xue, J.; Mu, N. Immunotherapy: A promising novel endometriosis therapy. Front Immunol, 2023; 14, 1128301. [CrossRef]

- Rahal, D.; Andrade, F.; Nisihara, R. Insights into the role of complement system in the pathophysiology of endometriosis. Immunol Lett. 2021;231:43-48. [CrossRef]

- Agostinis, C.; Balduit, A.; Mangogna, A.; Zito, G.; Romano, F.; Ricci, G.; Kishore, U.; Bulla, R. Immunological Basis of the Endometriosis: The Complement System as a Potential Therapeutic Target. Front Immunol. 2021 Jan 11;11:599117. [CrossRef]

- Agostinis, C.; Toffoli, M.; Zito, G.; Balduit, A.; Pegoraro, S.; Spazzapan, M.; et al. Proangiogenic properties of complement protein C1q can contribute to endometriosis. Front Immunol. 2024 Jun 25;15:1405597. [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, S.; Huang, X.; Elishaev, E.; Budiu, R.A.; Zhang, L.; Kim, Set al. Complement pathway is frequently altered in endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(23):6163-74. [CrossRef]

- Abramiuk, M.; Grywalska, E.; Małkowska, P.; Sierawska, O.; Hrynkiewicz, R.; Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej, P. The Role of the Immune System in the Development of Endometriosis. Cells. 2022;11(13):2028. [CrossRef]

- Milewski, Ł.; Dziunycz, P.; Barcz, E.; Radomski, D.; Roszkowski, P.I.; Korczak-Kowalska, G.; Kamiński, P.; Malejczyk, J. Increased levels of human neutrophil peptides 1, 2, and 3 in peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis: association with neutrophils, T cells and IL-8. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;91(1-2):64-70. [CrossRef]

- Takamura, M.; Koga, K.; Izumi, G.; Urata, Y.; Nagai, M.; Hasegawa, A.; et al. Neutrophil depletion reduces endometriotic lesion formation in mice. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;76(3):193-8. [CrossRef]

- Lukács, L.; Kovács, A.R.; Pál, L.; Szűcs, S.; Kövér, Á.; Lampé, R. Phagocyte function of peripheral neutrophil granulocytes and monocytes in endometriosis before and after surgery. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50(4):101796. [CrossRef]

- Hogg, C.; Horne, A.W.; Greaves, E. Endometriosis-associated macrophages: Origin, phenotype, and function. Front Endocrinol. 2020 11:7. [CrossRef]

- Hogg, C.; Panir, K.; Dhami, P.; Rosser, M.; Mack, M.; Soong, D.; et al. Macrophages inhibit and enhance endometriosis depending on their origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Feb 9;118(6):e2013776118. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.K.; Hu, W.T.; Tang, L.L.; Sheng, Y.R.; Wei, C.Y.; Li, M.Q.; Zhu, X.Y. Elevated heme impairs macrophage phagocytosis in endometriosis. Reproduction. 2019;158(3):257-266. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Gao, H.; Shao, W.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Liu, S. The Extracellular Vesicle-Macrophage Regulatory Axis: A Novel Pathogenesis for Endometriosis. Biomolecules. 2023;13(9):1376. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, P.C.; Lin, Y.J.; Wu, M.H.; Wing, L.Y.; Shoji, Y.; Tsai, S.J. Inhibition of CD36-dependent phagocytosis by prostaglandin E2 contributes to the development of endometriosis. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(2):850-60. [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.C.; Hou, S.H.; Lei, S.T.; Peng, H.Y.; Li, M.Q.; Zhao, D. Estrogen-regulated CD200 inhibits macrophage phagocytosis in endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2020; 138:103090. [CrossRef]

- Symons, L.K.; Miller, J.E.; Kay, V.R.; Marks, R.M.; Liblik, K.; Koti, M.; Tayade, C. The Immunopathophysiology of Endometriosis. Trends Mol Med. 2018;24(9):748-762. [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, T.; Ikeda, M.; Watanabe, T.; Negishi, Y.; Ichikawa, G.; Kaseki, H.; Akira, S.; Morita, R.; Suzuki, S. Downregulation of pattern recognition receptors on macrophages involved in aggravation of endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2024;91(1):e13812. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, Z. (). Transformation of macrophages into myofibroblasts in fibrosis-related diseases: emerging biological concepts and potential mechanism. Frontiers Immunol 2024, 15, 1474688. [CrossRef]

- Tuckerman, E.; Mariee, N.; Prakash, A.; Li, T.C.; Laird, S. Uterine natural killer cells in peri-implantation endometrium from women with repeated implantation failure after IVF. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;87(1-2):60-6. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Y.; Ishikawa, N.; Hirata, J.; Imaizumi, E.; Sasa, H.; Nagata, I. Changes of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets before and after operation of patients with endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1993;72(3):157-61. [CrossRef]

- Azeze, G.G.; Wu, L.; Alemu, B.K.; Wang, C.C.; Zhang, T. Changes in the number and activity of natural killer cells and its clinical association with endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. F&S Review 2024;5(2): 100072. doi: org/10.1016/j.xfnr.2024.100072.

- Jeung, I.; Cheon, K.; Kim, M.R. Decreased Cytotoxicity of Peripheral and Peritoneal Natural Killer Cell in Endometriosis. Biomed Res Int. 2016; 2016:2916070. [CrossRef]

- González-Foruria, I.; Santulli, P.; Chouzenoux, S.; Carmona, F.; Batteux, F.; Chapron, C. Soluble ligands for the NKG2D receptor are released during endometriosis and correlate with disease severity. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119961. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.J.; Jeung, I.C.; Park, A.; Park, Y.J.; Jung, H.; Kim, T.D.; Lee, H.G.; Choi, I.; Yoon, S.R. An increased level of IL-6 suppresses NK cell activity in peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis via regulation of SHP-2 expression. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(10):2176-89. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.W.; Du, Y.; Liu, X. Platelet-derived TGF-β1 mediates the down-modulation of NKG2D expression and may be responsible for impaired natural killer (NK) cytotoxicity in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(7):1462-74. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.J.; Sun, H.T.; Zhang, Z.F.; Shi, R.X.; Liu, L.B.; Shang, W.Q.; Wei, C.Y.; Chang, K.K.; Shao, J.; Wang, M.Y.; Li, M.Q. IL15 promotes growth and invasion of endometrial stromal cells and inhibits killing activity of NK cells in endometriosis. Reproduction. 2016;152(2):151-60. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; Zhou, W.J.; Chang, K.K.; Mei, J.; Huang, L.Q.; Wang, M.Y.; Meng, Y.; Ha, S.Y.; Li, D.J.; Li, M.Q. The crosstalk between endometrial stromal cells and macrophages impairs cytotoxicity of NK cells in endometriosis by secreting IL-10 and TGF-β. Reproduction. 2017;154(6):815-825. [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.L.; Rosa, N.N.; Ângelo-Dias, M.; Martins, C.; Borrego, L.M.; Lima, J. Natural Killer Cell Receptors and Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24(1):331. [CrossRef]

- Saeki, S.; Fukui, A.; Mai, C.; Takeyama, R.; Yamaya, A.; Shibahara, H. Co-expression of activating and inhibitory receptors on peritoneal fluid NK cells in women with endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2023; 155:103765. [CrossRef]

- Sugamata, M.; Ihara, T.; Uchiide, I. Increase of activated mast cells in human endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005;53(3):120-5. [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, D.; Kaulfuss, S.; Fuhrmann, U.; Maurer, M.; Zollner, T.M. Mast cells in endometriosis: guilty or innocent bystanders? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(3):237-41. [CrossRef]

- McCallion, A.; Nasirzadeh, Y.; Lingegowda, H.; Miller, J.E.; Khalaj, K.; Ahn, S.; et al . Estrogen mediates inflammatory role of mast cells in endometriosis pathophysiology. Front Immunol. 2022 Aug 9;13:961599. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Chen, Y.; Ding, S.; Zou, G.; Zhu, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, X. GPR30-mediated non-classic estrogen pathway in mast cells participates in endometriosis pain via the production of FGF2. Front Immunol. 2023 Feb 8;14:1106771. [CrossRef]

- Schulke, L.; Berbic, M.; Manconi, F.; Tokushige, N.; Markham, R.; Fraser, I.S. Dendritic cell populations in the eutopic and ectopic endometrium of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(7):1695-703. [CrossRef]

- Qiaomei, Z.; Ping, W.; Yanjing, Z.; Jinhua, W.; Shaozhan, C.; Lihong, C. Features of peritoneal dendritic cells in the development of endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2023;21(1):4. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Jiang, L.; Xu, Y. HSD11B1 overexpression in dendritic cells and stromal cells relates to endometriosis by inhibiting dendritic cell proliferation and maturation. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2024; 40(1), 2411607. [CrossRef]

- Maridas, D.E.; Hey-Cunningham, A.J.; Ng, C.H.M.; Markham, R.; Fraser, I.S.; Berbic, M. Peripheral and endometrial dendritic cell populations during the normal cycle and in the presence of endometriosis. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord. 2014;6(2):67-119. [CrossRef]

- Suen, J.L.; Chang, Y.; Shiu, Y.S.; Hsu, C.Y.; Sharma, P.; Chiu, C.C.; Chen, Y.J.; Hour, T.C.; Tsai, E.M. IL-10 from plasmacytoid dendritic cells promotes angiogenesis in the early stage of endometriosis. J Pathol. 2019;249(4):485-497. [CrossRef]

- Knez, J.; Kovačič, B.; Goropevšek, A. The role of regulatory T-cells in the development of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2024:39(7): 1367–1380. [CrossRef]

- Riccio, L. G. C.; Baracat, E. C.; Chapron, C.; Batteux, F.; Abrão, M. S. The role of the B lymphocytes in endometriosis: A systematic review. J Reprod Immunol, 2017; 123, 29–34. [CrossRef]

- Menzhinskaya, I. V.; Pavlovich, S. V.; Melkumyan, A. G.; Chuprynin, V. D.; Yarotskaya, E. L.; Sukhikh, G. T. Potential Significance of Serum Autoantibodies to Endometrial Antigens, α-Enolase and Hormones in Non-Invasive Diagnosis and Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24(21), 15578. [CrossRef]

- Kisovar, A.; Becker, C.M.; Granne, I.; Southcombe, J.H. The role of CD8+ T cells in endometriosis: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1225639. [CrossRef]

- Chopyak, V.V.; Koval, H.D.; Havrylyuk, A.M.; Lishchuk-Yakymovych, K.A.; Potomkina, H.A.; Kurpisz, M.K. Immunopathogenesis of endometriosis - a novel look at an old problem. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2022;47(1):109-116. [CrossRef]

- Hanada, T.; Tsuji, S.; Nakayama, M.; Wakinoue, S.; Kasahara, K.; Kimura, F.; Mori, T.; Ogasawara, K.; Murakami, T. Suppressive regulatory T cells and latent transforming growth factor-β-expressing macrophages are altered in the peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Riccio, L.G.C.; Andres, M.P.; Dehó, I.Z.; Fontanari, G.O.; Abrão, M.S. Foxp3+CD39+CD73+ regulatory T-cells are decreased in the peripheral blood of women with deep infiltrating endometriosis. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2024 ;79:100390. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Q.; Wang, Y.; Chang, K.K.; Meng, Y.H.; Liu, L.B.; Mei, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.Q.; Jin, L.P.; Li, D.J. CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by endometrial stromal cell-derived TECK promotes the growth and invasion of endometriotic lesions. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(10):e1436. [CrossRef]

- Sisnett, D. J.; Zutautas, K. B.; Miller, J. E.; Lingegowda, H.; Ahn, S. H.; McCallion, A.; Bougie, O.; Lessey, B. A.; Tayade, C. The Dysregulated IL-23/TH17 Axis in Endometriosis Pathophysiology. J Immunol. 2024; 212(9), 1428–1441. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xu, Q.; Yu, S.; Zhang, T. Perturbations of the endometrial immune microenvironment in endometriosis and adenomyosis: their impact on reproduction and pregnancy. Semin Immunopathol. 2025 Feb 18;47(1):16. [CrossRef]

- Olkowska-Truchanowicz, J.; Białoszewska, A.; Zwierzchowska, A., Sztokfisz-Ignasiak, A.; Janiuk, I.; Dąbrowski, F.; Korczak-Kowalska, G.; Barcz, E.; Bocian, K.; Malejczyk, J. Peritoneal Fluid from Patients with Ovarian Endometriosis Displays Immunosuppressive Potential and Stimulates Th2 Response. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(15):8134. [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.L.; Rosa, N.N,; Martins, C.; Ângelo-Dias, M.; Borrego, L.M.; Lima, J. The Role of NK and T Cells in Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(18):10141. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, T.; Hoffmann, V.; Olliges, E;, Bobinger, A.; Popovici, R.; Nößner, E.; Meissner, K. Reduced frequency of perforin-positive CD8+ T cells in menstrual effluent of endometriosis patients. J Reprod Immunol, 2021; 148, 103424. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, R.; Moini, A.; Hosseini, R.; Fatehnejad, M.; Yekaninejad, M. S.; Javidan, M.; et al. A higher number of exhausted local PD1+, but not TIM3+, NK cells in advanced endometriosis. Heliyon, 2023; 10(1), e23294. [CrossRef]

- Abramiuk, M.; Bębnowska, D.; Hrynkiewicz, R.; Polak, P.N.G.; Kotarski, J.; Roliński. J.; Grywalska, E. CLTA-4 Expression is Associated with the Maintenance of Chronic Inflammation in Endometriosis and Infertility. Cells. 2021;10(3):487. [CrossRef]

- Podgaec, S.; Abrao, M.S.; Días, J.A. Jr; Rizzo, L.V.; de Oliveira, R.M.; Baracat, E.C. Endometriosis: an inflammatory disease with a Th2 immune response component. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(5):1373-9. [CrossRef]

- Santoso ,B.; Sa'adi, A.; Dwiningsih, S.R.; Tunjungseto, A.; Widyanugraha, M.Y.A.; Mufid, A.F.; Rahmawati, N.Y.; Ahsan, F. Soluble immune checkpoints CTLA-4, HLA-G, PD-1, and PD-L1 are associated with endometriosis-related infertility. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2020;84(4):e13296. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, D.B.; Liang, Y.M. Evaluation of estrogen in endometriosis patients: Regulation of GATA-3 in endometrial cells and effects on Th2 cytokines. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42(6):669-77. [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.R.; Li, P.X.; Zhu, X.H.; Mao, X.F.; Peng, J.L.; Chen, X.P.; et al. Peripheral immune characteristics and subset disorder in reproductive females with endometriosis. Front Immunol. 2024; 15:1431175. [CrossRef]

- Delbandi, A. A.; Mahmoudi, M.; Shervin, A.; Farhangnia, P.; Mohammadi, T;, Zarnani, A. H. Increased circulating T helper 17 (TH17) cells and endometrial tissue IL-17-producing cells in patients with endometriosis compared with non-endometriotic subjects. Reproductive Biol, 2025; 25(2), 101019. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Slawek, A.; Lorek, D.; Kedzierska, A.E.; Kubik, P.; Pajak, J.; Chrobak, A.; Chelmonska-Soyta, A. Peripheral blood subpopulations of Bregs producing IL-35 in women with endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2023;89(3):e13675. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhu, D.; Han, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, B.; Zhou, P.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Zou, H. HMGB1: a double-edged sword and therapeutic target in the female reproductive system. Frontiers Immunol, 2523, 14, 1238785. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, J. (). High mobility group box 1 promotes endometriosis under hypoxia by regulating inflammation and autophagy in vitro and in vivo. Internat immunopharmacol, 2024; 127, 111397. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Guo, R.; Na, X.; Jiang, S.; Liang, J.; Guo, C.; Fang, Y.; Na, Z.; Li, D. Hypoxia and the endometrium: An indispensable role for HIF-1α as therapeutic strategies. Redox biology, 2024; 73, 103205. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, R.; Hu, R.; Yao, J.; Yang, Y. PEG2-Induced Pyroptosis Regulates the Expression of HMGB1 and Promotes hEM15A Migration in Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci, 2022; 23(19), 11707. [CrossRef]

- Jana, B.; Andronowska, A.; Całka, J.; Mówińska, A. Biosynthetic pathway for leukotrienes is stimulated by lipopolysaccharide and cytokines in pig endometrial stromal cells. Sci Rep, 2025; 15(1), 2806. [CrossRef]

- Ihara, T.; Uchiide, I.; Sugamata, M. Light and electron microscopic evaluation of antileukotriene therapy for experimental rat endometriosis. Fertility Sterility, 2004; 81 Suppl 1, 819–823. [CrossRef]

- Kiykac Altinbas, S.; Tapisiz, O. L.; Cavkaytar, S.; Simsek, G.; Oguztuzun, S., Goktolga, U. (). Is montelukast effective in regression of endometrial implants in an experimentally induced endometriosis model in rats?. Europ J Obstet Gnecol Reprod Biol, 2015; 184, 7–12. [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Zhou, W.; Chen, S.; Shi, Y.; Su, L.; Zhu, M.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Q. Lipoxin A4 suppresses the development of endometriosis in an ALX receptor-dependent manner via the p38 MAPK pathway. British J Pharmacol, 2014; 171(21), 4927–4940. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z. X.; He, X. R.; Ding, X. Y.; Chen, J. H.; Lei, Y. H.; Bai, J. B.; Lin, D. C.; Hong, Y. H.; Lan, J. F;, Chen, Q. H. (). Lipoxin A4 depresses inflammation and promotes autophagy via AhR/mTOR/AKT pathway to suppress endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol 2023;, 89(3), e13659. [CrossRef]

- Dmitrieva, N.; Suess, G.; Shirley, R. Resolvins RvD1 and 17(R)-RvD1 alleviate signs of inflammation in a rat model of endometriosis. Fertility Sterility, 2014; 102(4), 1191–1196. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Lamont, G. J.; Lamont, R. J.; Uriarte, S. M.; Wang, H.; Scott, D. A. Resolvin D1, resolvin D2 and maresin 1 activate the GSK3β anti-inflammatory axis in TLR4-engaged human monocytes. Innate immunity, 2016; 622(3), 186–195. [CrossRef]

- de Fáveri, C.; Fermino, P.M.P.; Piovezan, A.P.; Volpato, LK. The Inflammatory Role of Pro-Resolving Mediators in Endometriosis: An Integrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Apr 22;22(9):4370. [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Castillo, M.; Ortega, Á.; Cudris-Torres, L.; Duran, P.; Rojas, M.; Manzano, A.; et al. Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators: The Future of Chronic Pain Therapy? Int J Mol Sci, 2021; 22(19), 10370. [CrossRef]

- Collie, B.; Troisi, J.; Lombardi, M.; Symes, S.; Richards, S. The Current Applications of Metabolomics in Understanding Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Metabolites. 2025 Jan 14;15(1):50. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.B. Hypoxia, cytokines and stromal recruitment: parallels between pathophysiology of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, endometriosis and peritoneal metastasis. Pleura Peritoneum. 2018 Mar 21;3(1):20180103. [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Li, D. Ferroptosis and oxidative stress in endometriosis: A systematic review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024 Mar 15;103(11):e37421. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; He, Q.; Huang, D.; Tan, X. Ferroptosis and tumor immunity: In perspective of the major cell components in the tumor microenvironment. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023 Dec 15;961:176124. [CrossRef]

- Kondera-Anasz, Z.; Sikora, J.; Mielczarek-Palacz, A.; Jońca, M. Concentrations of interleukin (IL)-1alpha, IL-1 soluble receptor type II (IL-1 sRII) and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1 Ra) in the peritoneal fluid and serum of infertile women with endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005 Dec 1;123(2):198-203. [CrossRef]

- Sikora, J.; Ferrero, S.; Mielczarek-Palacz, A.; Kondera-Anasz, Z. The Delicate Balance between the Good and the Bad IL-1 Proinflammatory Effects in Endometriosis. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25(18):2105-2121. [CrossRef]

- Malvezzi, H.; Hernandes, C.; Piccinato, C.A.; Podgaec, S. Interleukin in endometriosis-associated infertility-pelvic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Reproduction. 2019 Jul;158(1):1-12. [CrossRef]

- Werdel, R.; Mabie, A.; Evans, T.L.; Coté, R.D.; Schlundt, A.; Doehrman, P.; Dilsaver, D.; Coté, J.J. Serum Levels of Interleukins in Endometriosis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024;31(5):387-396.e11. [CrossRef]

- Koumantakis, E.; Matalliotakis, I.; Neonaki, M.; Froudarakis, G.; Georgoulias, V. Soluble serum interleukin-2 receptor, interleukin-6 and interleukin-1a in patients with endometriosis and in controls. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1994;255(3):107-12. [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.N.; Guo, S.W.; Ogawa, K.; Fujishita, A.; Mori, T. The role of innate and adaptive immunity in endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2024;163:104242. [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Zeng, K.; Peng, Q.; Wu, X.; Lei, X. Clinical significance of serum Th1/Th2 cytokines in patients with endometriosis. Women Health. 2023;63(2):73-82. [CrossRef]

- Voltolini Velho, R.; Halben, N.; Chekerov, R.; Keye, J.; Plendl, J.; Sehouli, J.; Mechsner, S. Functional changes of immune cells: signal of immune tolerance of the ectopic lesions in endometriosis? Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;43(2):319-328. [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.D.; Hu, C.Y.; Zhu, M.C.; Ou, H.L.; Qian, Y.L. Immunological microenvironment alterations in follicles of women with proven severe endometriosis undergoing in vitro fertilization. Mol Biol Rep. 2019 Oct;46(5):4675-4684. [CrossRef]

- Oală, I.E.; Mitranovici, M.I.; Chiorean, D.M.; Irimia, T.; Crișan, A.I.; Melinte, I.M.; , et al. Endometriosis and the Role of Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in Pathophysiology: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024 Jan 31;14(3):312. [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, M.; Hojati, V.; Attaranzadeh, A.; Saifi, B. Evaluation of IL-3, IL-5, and IL-6 concentration in the follicular fluid of women with endometriosis: A cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2022 Apr 21;20(3):213-220. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Yang, B.C.; Wu, M.H.; Huang, K.E. Enhanced interleukin-4 expression in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1997 Jun;67(6):1059-64. [CrossRef]

- OuYang, Z.; Hirota, Y.; Osuga, Y.; Hamasaki, K.; Hasegawa, A.; Tajima, T.; et al. Interleukin-4 stimulates proliferation of endometriotic stromal cells. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(2):463-9. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Jin, D.; Zhang ,Y. Serum miR-17, IL-4, and IL-6 levels for diagnosis of endometriosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Jun;97(24):e10853. [CrossRef]

- Sadat Sandoghsaz, R.; Montazeri, F.; Shafienia, H.; Mehdi Kalantar, S.; Javaheri, A.; Samadi, M. Expression of miR-21 &IL-4 in endometriosis. Hum Immunol. 2024;85(1):110746. [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Yoshioka, H.; Yoshida, S.; Iwabe, T.; Onohara, Y.; Tanikawa, M.; Terakawa, N. Increased interleukin-6 levels in peritoneal fluid of infertile patients with active endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Mar;176(3):593-7. [CrossRef]

- Pellicer, A.; Albert, C.; Mercader, A.; Bonilla-Musoles, F.; Remohí, J.; Simón, C. The follicular and endocrine environment in women with endometriosis: local and systemic cytokine production. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(3):425-31. [CrossRef]

- Bellelis, P.; Frediani Barbeiro, D.; Gueuvoghlanian-Silva, B.Y.; Kalil, J.; Abrão, M.S.; Podgaec, S. Interleukin-15 and Interleukin-7 are the Major Cytokines to Maintain Endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2019;84(5):435-444. [CrossRef]

- Akoum, A.; Lawson, C.; McColl, S.; Villeneuve, M. Ectopic endometrial cells express high concentrations of interleukin (IL)-8 in vivo regardless of the menstrual cycle phase and respond to oestradiol by up-regulating IL-1-induced IL-8 expression in vitro. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001 Sep;7(9):859-66. [CrossRef]

- Sikora, J.; Smycz-Kubańska, M.; Mielczarek-Palacz, A.; Kondera-Anasz, Z. Abnormal peritoneal regulation of chemokine activation-The role of IL-8 in pathogenesis of endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017;77(4): e12622. [CrossRef]

- Punnonen, J.; Teisala, K.; Ranta, H.; Bennett, B.; Punnonen, R. Increased levels of interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 in the peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 May;174(5):1522-6. [CrossRef]

- Suen, J.L.; Chang, Y.; Chiu, P.R.; Hsieh, T.H.; His, E.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, Y.F.; Tsai, E.M. Serum level of IL-10 is increased in patients with endometriosis, and IL-10 promotes the growth of lesions in a murine model. Am J Pathol. 2014;184(2):464-71. [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, D.; Viganó, P.; Di Blasio, A.M.; Sinigaglia, F.; Vignali, M.; Panina-Bordignon, P. Interleukin-12 and its free p40 subunit regulate immune recognition of endometrial cells: potential role in endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(3):911-6. [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, N.Y.; Ahsan, F.; Santoso, B.; Mufid, A.F.; Sa'adi, A.; Dwiningsih, S.R.; Tunjungseto, A.; Widyanugraha, M.Y.A. IL-8 and IL-12p70 are associated with pelvic pain among infertile women with endometriosis. Pain Med. 2023 Nov 2;24(11):1262-1269. PMID: 37326977. [CrossRef]

- Chegini, N.; Roberts, M.; Ripps, B. Differential expression of interleukins (IL)-13 and IL-15 in ectopic and eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis and normal fertile women. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2003 Feb;49(2):75-83. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Ma, Z.Y.; Song, N. Inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, TNF-α and peritoneal fluid flora were associated with infertility in patients with endometriosis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018 May;22(9):2513-2518. [CrossRef]

- Arici, A.; Matalliotakis, I.; Goumenou, A.; Koumantakis, G.; Vassiliadis, S.; Selam, B.; Mahutte, N.G. Increased levels of interleukin-15 in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis: inverse correlation with stage and depth of invasion. Hum Reprod. 2003 Feb;18(2):429-32. [CrossRef]

- Koga, K.; Osuga, Y.; Yoshino, O.; Hirota, Y.; Yano, T.; Tsutsumi, O.; Taketani, Y. Elevated interleukin-16 levels in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis may be a mechanism for inflammatory reactions associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2005 Apr;83(4):878-82. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Xi, S.; Xu, X.; Du, X.; Zheng, X.; Hu, W.; Sun, R.; Tian, Z.; Fu, B.; Wei, H. Pyroptotic T cell-derived active IL-16 has a driving function in ovarian endometriosis development. Cell Rep Med. 2024 Mar 19;5(3):101476. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Lin, J.; Qian, Y.; Deng, L. Peritoneal fluid concentrations of interleukin-17 correlate with the severity of endometriosis and infertility of this disorder. BJOG. 2005;112(8):1153-5. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; Edwards, A.K.; Singhm S.S.; Young, S.L.; Lessey, B.A.; Tayade, C. IL-17A Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis by Triggering Proinflammatory Cytokines and Angiogenic Growth Factors. J Immunol. 2015;195(6):2591-600. [CrossRef]

- Shi JL, Zheng ZM, Chen M, Shen HH, Li MQ, Shao J. IL-17: an important pathogenic factor in endometriosis. Int J Med Sci. 2022;19(4):769-778. [CrossRef]

- Arici, A.; Matalliotakis, I.; Goumenou, A.; Koumantakis, G.; Vassiliadis, S.; Mahutte, N.G. Altered expression of interleukin-18 in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(4):889-94. [CrossRef]

- Santulli, P.; Borghese, B.; Chouzenoux, S.; Streuli, I.; Borderie, D.; de Ziegler, D.; Weill, B.; Chapron, C.; Batteux, F. Interleukin-19 and interleukin-22 serum levels are decreased in patients with ovarian endometrioma. Fertil Steril. 2013 Jan;99(1):219-226.e2. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.B.; Chang, K.K.; Li, H.; Li, M.Q.; Shao, J. IL-22 in the endometriotic milieu promotes the proliferation of endometrial stromal cells via stimulating the secretion of CCL2 and IL-8. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013 Sep 15;6(10):2011-20.

- Zhang, Q.F.; Chen, G.Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.J.; Song, Y.F. Relationship between resistin and IL-23 levels in follicular fluid in infertile patients with endometriosis undergoing IVF-ET. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017 Dec;26(9):1431-1435. [CrossRef]

- Bungum, H.F.; Nygaard, U.; Vestergaard, C.; Martensen, P.M.; Knudsen, U.B. Increased IL-25 levels in the peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2016 Apr;114:6-9. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.M.; Lai, Z.Z.; Ha, S.Y.; Yang, H.L.; Liu, L.B.; Wang, Y.; et al. IL-2 and IL-27 synergistically promote growth and invasion of endometriotic stromal cells by maintaining the balance of IFN-γ and IL-10 in endometriosis. Reproduction. 2020 Mar;159(3):251-260. [CrossRef]

- O, D.; Waelkens, E.; Vanhie, A.; Peterse, D.; Fassbender, A.; D'Hooghe, T. The Use of Antibody Arrays in the Discovery of New Plasma Biomarkers for Endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2020 Feb;27(2):751-762. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Oh, Y.S.; Heo, S.H.; Kim, K.H.; Chae, H.D.; Kim, C.H, Kang BM. Role of interleukin-32 in the pathogenesis of endometriosis: in vitro, human and transgenic mouse data. Hum Reprod. 2018 May 1;33(5):807-816. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Kim, S.; Oh, Y.S.; Cho, S.; Hoon Kim, S. Elevated serum interleukin-32 levels in patients with endometriosis: A cross-sectional study. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2019 Aug;82(2):e13149. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.E.; Monsanto, S.P.; Ahn, S.H.; Khalaj, K.; Fazleabas, A.T.; Young, S.L.; Lessey, B.A.; Koti, M.; Tayade, C. Interleukin-33 modulates inflammation in endometriosis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17903. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.E.; Lingegowda, H.; Symons, L.K.; Bougie, O.; Young, S.L.; Lessey, B.A.; Koti, M.; Tayade, C. IL-33 activates group 2 innate lymphoid cell expansion and modulates endometriosis. JCI Insight. 2021 6(23):e149699. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Liu, X.; Guo, S.W. Interleukin-33 Derived from Endometriotic Lesions Promotes Fibrogenesis through Inducing the Production of Profibrotic Cytokines by Regulatory T Cells. Biomedicines. 2022 Nov 11;10(11):2893. [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Ma, J.; Peng, Y.; Sun, M.; Xu, K.; Wu, R.; Lin, J. Autocrine Production of Interleukin-34 Promotes the Development of Endometriosis through CSF1R/JAK3/STAT6 signaling. Sci Rep. 2019 Nov 14;9(1):16781. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Peng, Z.; Ban, D.; Zhang, Y. Upregulation of Interleukin 35 in Patients With Endometriosis Stimulates Cell Proliferation. Reprod Sci. 2018 Mar;25(3):443-451. [CrossRef]

- Smycz-Kubanska, M.; Wendlocha, D.; Witek, A.; Mielczarek-Palacz, A. The role of selected cytokines from the interleukin-1 family in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Ginekol Pol. 2025;96(2):126-135. [CrossRef]

- Krygere, L.; Jukna, P.; Jariene, K.; Drejeriene, E. Diagnostic Potential of Cytokine Biomarkers in Endometriosis: Challenges and Insights. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2867. [CrossRef]

- Eisermann, J.; Gast, M.J.; Pineda, J.; Odem, R.R.; Collins, J.L. Tumor necrosis factor in peritoneal fluid of women undergoing laparoscopic surgery. Fertil Steril. 1988 Oct;50(4):573-9. [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Infante, F.M.; Flores-Medina, S.; López-Hurtado, M.; Zamora-Ruíz, A.; Sosa González, I.E.; Narcio Reyes, M.L.; Villagrana-Zessati, R. Tumor necrosis factor in peritoneal fluid from asymptomatic infertile women. Arch Med Res. 1999 Mar-Apr;30(2):138-43. [CrossRef]

- Grund, E.M.; Kagan, D.; Tran, C.A.; Zeitvogel, A.; Starzinski-Powitz, A.; Nataraja, S.; Palmer, S.S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulates inflammatory and mesenchymal responses via mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase, p38, and nuclear factor kappaB in human endometriotic epithelial cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73(5):1394-404. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.A.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, M.R.; Hwang, K.J.; Chang, D.Y.; Jeon, M.K. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression in eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis by stromal cell culture through nuclear factor-kappaB activation. J Reprod Med. 2009;54(10):625-30.

- Oosterlynck, D.J.; Meuleman, C.; Waer, M.; Koninckx, P.R. Transforming growth factor-beta activity is increased in peritoneal fluid from women with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(2):287-92.

- Abdoli, M.; Hoseini, S.M.; Sandoghsaz, R.S.; Javaheri, A.; Montazeri, F.; Moshtaghioun, S.M. Endometriotic lesions and their recurrence: A Study on the mediators of immunoregulatory (TGF-β/miR-20a) and stemness (NANOG/miR-145). J Reprod Immunol. 2024;166:104336. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Wang, M. J.; Wang, Y. X.; Shen, B. CXC chemokines influence immune surveillance in immunological disorders: Polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular basis of disease, 2023; 1869(5), 166704. [CrossRef]

- Shimoya, K.; Zhang, Q.; Temma-Asano, K.; Hayashi, S.; Kimura, T.; Murata, Y. Fractalkine in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obst, 2005; 91(1), 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Arici, A.; Oral, E.; Attar, E.; Tazuke, S.I.; Olive, D.L. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 concentration in peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis and its modulation of expression in mesothelial cells. Fertil Steril. 1997;67(6):1065-72. [CrossRef]

- Nirgianakis, K.; McKinnon, B.; Ma, L.; Imboden, S.; Bersinger, N.; Mueller, M.D. Peritoneal fluid biomarkers in patients with endometriosis: a cross-sectional study. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2020 May 8;42(2):113-122. [CrossRef]

- Heidari, S.; Kolahdouz-Mohammadi, R.; Khodaverdi, S.; Tajik, N.; Delbandi, A.A. Expression levels of MCP-1, HGF, and IGF-1 in endometriotic patients compared with non-endometriotic controls. BMC Womens Health. 2021 Dec 20;21(1):422. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Mu, L. Association between macrophage migration inhibitory factor in the endometrium and estrogen in endometriosis. Exp Ther Med. 2015 Aug;10(2):787-791. [CrossRef]

- Fukaya, T.; Sugawara, J.; Yoshida, H.; Yajima, A. The role of macrophage colony stimulating factor in the peritoneal fluid in infertile patients with endometriosis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1994 Mar;172(3):221-6. [CrossRef]

- Budrys, N.M.; Nair, H.B.; Liu, Y.G.; Kirma, N.B.; Binkley, P.A.; Kumar, S.; Schenken, R.S.; Tekmal, R.R. Increased expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor and its receptor in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012 May;97(5):1129-35.e1. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Tan, X.; Feng, G.; Zhuo, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Banda, S.; Wang, L.; Zheng, W.; Chen, L.; Yu, D.; Guo, C. Research advances in drug therapy of endometriosis. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1199010. [CrossRef]

- Sharpe-Timms, K.L.; Bruno, P.L.; Penney, L.L.; Bickel, J.T. Immunohistochemical localization of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in matched endometriosis and endometrial tissues. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994 Sep;171(3):740-5. [CrossRef]

- Propst, A.M.; Quade, B.J.; Nowak, R.A.; Stewart, E.A. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in adenomyosis and autologous endometrium. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2002 Mar-Apr;9(2):93-7. [CrossRef]

- Toullec, L.; Batteux, F.; Santulli, P.; Chouzenoux, S.; Jeljeli, M.; Belmondo, T.; Hue, S.; Chapron, C. High Levels of Anti-GM-CSF Antibodies in Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2020 Jan;27(1):211-217. [CrossRef]

- Han, M.T.; Cheng, W.; Zhu, R.; Wu, H.H.; Ding, J.; Zhao, N.N.; Li, H.; Wang, FX. The cytokine profiles in follicular fluid and reproductive outcomes in women with endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2023 Jun;89(6):e13633. [CrossRef]

- Nisolle, M.; Casanas-Roux, F.; Anaf, V.; Mine, J.M.; Donnez, J. Morphometric study of the stromal vascularisation in peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1993;59(3):681-4.

- McLaren, J.; Prentice, A.; Charnock-Jones, D.S.; Millican, S.A.; Müller, K.H.; Sharkey, A.M.; Smith, S.K. Vascular endothelial growth factor is produced by peritoneal fluid macrophages in endometriosis and is regulated by ovarian steroids. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(2):482-9. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.R.; Kim ,S.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Hong, S.H.; Chae, H.D.; Kim, C.H.; Kang, B.M.; Choi, Y.M. Expression of epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor-2, and platelet-derived growth factor-A in the eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007 Jun;33(3):242-7. [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, B.; Szaflik, T.; Romanowicz, H.; Bryś, M.; Forma, E.; Szyłło, K. Analysis of VEGF, IGF1/2 and the Long Noncoding RNA (lncRNA) H19 Expression in Polish Women with Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 12;25(10):5271. [CrossRef]

- Pantelis, A.; Machairiotis, N.; Lapatsanis, D.P. The Formidable yet Unresolved Interplay between Endometriosis and Obesity. Scientific World Journal. 2021 Apr 20;2021:6653677. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Q.; Ren, Y.F.; Li, B.B.; Wei, C.; Yu, B. The mysterious association between adiponectin and endometriosis. Front Pharmacol. 2024 May 15;15:1396616. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Yi, K.W. What is the link between endometriosis and adiposity? Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2022 May;65(3):227-233. [CrossRef]

- Matarese, G.; Alviggi, C.; Sanna, V.; Howard, J.K.; Lord, G.M.; Carravetta, C.; Fontana, S.; Lechler, R.I.; Bloom, S.R.; De Placido, G. Increased leptin levels in serum and peritoneal fluid of patients with pelvic endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000 Jul;85(7):2483-7. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Bae, N.; Kim, T.; Hsu, A.L.; Hunter, M.I.; Shin, J.H.; Jeong, J.W. Leptin Stimulates Endometriosis Development in Mouse Models. Biomedicines. 2022 Sep 1;10(9):2160. [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzopoulos, D.R.; Lempesis, I.G.; Samartzis, N.; Kolovos, G.; Dedes, I.; Daniilidis, A.; Nirgianakis, K.; Leeners, B.; Goulis, D.G.; Samartzis, E.P. Leptin concentrations in endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Reprod Immunol. 2021 Aug;146:103338. [CrossRef]

- Wójtowicz, M.; Zdun, D.; Owczarek, A.J.; Skrzypulec-Plinta, V.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M. Evaluation of adipokines concentrations in plasma, peritoneal, and endometrioma fluids in women operated on for ovarian endometriosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Nov 21;14:1218980. [CrossRef]

- Zyguła, A.; Sankiewicz, A.; Sakowicz, A.; Dobrzyńska, E.; Dakowicz, A.; Mańka, G.; et al. Is the leptin/BMI ratio a reliable biomarker for endometriosis? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024 Mar 19;15:1359182. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.H.; Chen, K.F.; Lin, S.C.; Lgu, C.W.; Tsai, S.J. Aberrant expression of leptin in human endometriotic stromal cells is induced by elevated levels of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha. Am J Pathol. 2007 Feb;170(2):590-8. [CrossRef]

- Takemura, Y.; Osuga, Y.; Harada, M.; Hirata, T.; Koga, K.; Morimoto, C.; Hirota, Y.; Yoshino, O.; Yano, T.; Taketani, Y. Serum adiponectin concentrations are decreased in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005 Dec;20(12):3510-3. [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.W.; Shin, J.H.; Park, H.T.; Kim, T.; Kim, S.H.; Hur, J.Y. Resistin concentration is increased in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010 Nov;64(5):318-23. [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.K.; Ha, Y.R.; Yi, K.W.; Park, H.T.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, T.; Hur, J.Y. Increased expression of resistin in ectopic endometrial tissue of women with endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017 Nov;78(5). [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Kim, S.H.; Oh, Y.S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.R.; Chae, H.D. Increased Expression of Retinol-Binding Protein 4 in Ovarian Endometrioma and Its Possible Role in the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 May 29;22(11):5827. [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.J.; Sun, J.N.; Gan, L.; Sun, J. Identification of molecular subtypes and immune infiltration in endometriosis: a novel bioinformatics analysis and In vitro validation. Front Immunol. 2023 Aug 18;14:1130738. [CrossRef]

- Krasnyi, A.M.; Sadekova, A.A.; Smolnova, T.Y.; Chursin, V.V.; Buralkina, N.A.; Chuprynin, V.D.; Yarotskaya, E.; Pavlovich, S.V.; Sukhikh, G.T. The Levels of Ghrelin, Glucagon, Visfatin and Glp-1 Are Decreased in the Peritoneal Fluid of Women with Endometriosis along with the Increased Expression of the CD10 Protease by the Macrophages. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 8;23(18):10361. [CrossRef]

- Morotti, M.; Vincent, K.; Becker, C.M. Mechanisms of pain in endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:8-13. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Zhang, W.; Leng, J.; Lang, J. Research on central sensitisation of endometriosis-associated pain: a systematic review of the literature. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1447-1456. [CrossRef]

- Monnin, N.; Fattet, A.J.; Koscinski, I. Endometriosis: Update of Pathophysiology, (Epi) Genetic and Environmental Involvement. Biomedicines. 2023;11(3):978. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.J.; Lv, W. A laparoscopic surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis and the review of literature. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2016;43(4):616-618.

- Vercellini, P.; Fedele, L.; Aimi, G.; Pietropaolo, G.; Consonni, D.; Crosignani, P.G. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):266-71. [CrossRef]

- As-Sanie, S.; Kim, J.; Schmidt-Wilcke, T.; Sundgren, P. C.; Clauw, D. J.; Napadow, V.; Harris, R. E. Functional Connectivity is Associated With Altered Brain Chemistry in Women With Endometriosis-Associated Chronic Pelvic Pain. The journal of pain, 2016; 17(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Eippert, F.; Tracey, I.; Chen, A.; De, E.; Argoff, C. Pain and the PAG: learning from painful mistakes. Nat Neurosci 2014;17(11):1438-1439. [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.V.; Tokushige, N.; Berbic, M.; Markham, R.; Fraser, I.S. Macrophages and nerve fibres in peritoneal endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(4):835-41. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Liang, Y.; Lin, H.; Dai, Y.; Yao, S. Autonomic nervous system and inflammation interaction in endometriosis-associated pain. J Neuroinflam, 2020 17(1), 80. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xie, H.; Yao, S.; Liang, Y. Macrophage and nerve interaction in endometriosis. J Neuroinflam, 2017; 14(1), 53. [CrossRef]

- Greaves, E.; Temp, J.; Esnal-Zufiurre, A.; Mechsner, S.; Horne, A.W.; Saunders, P.T. Estradiol is a critical mediator of macrophage-nerve cross talk in peritoneal endometriosis. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(8):2286-97. [CrossRef]

- Falcone, T.; Flyckt, R. Clinical Management of Endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar;131(3):557-571. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, P.; Bajaj, P.; Madsen, H.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Endometriosis is associated with central sensitization: a psychophysical controlled study. J Pain. 2003;4(7):372-80. [CrossRef]

- Maddern, J.; Grundy, L.; Castro, J.; Brierley, S.M. Pain in Endometriosis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:590823. [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.; Maddern, J.; Erickson, A.; Harrington, A.M.; Brierley, S.M. Peripheral and central neuroplasticity in a mouse model of endometriosis. J Neurochem. 2024;168(11):3777-3800. [CrossRef]

- Machairiotis, N.; Vasilakaki, S.; Thomakos, N. Inflammatory Mediators and Pain in Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines. 2021 Jan 8;9(1):54. [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Guo, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, X. Macrophage-derived netrin-1 contributes to endometriosis-associated pain. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Forster, R.; Sarginson, A.; Velichkova, A.; Hogg, C.; Dorning, A.; Horne, A.W.; Saunders, P.T.K.; Greaves, E. Macrophage-derived insulin-like growth factor-1 is a key neurotrophic and nerve-sensitizing factor in pain associated with endometriosis. FASEB J. 2019;33(10):11210-11222. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinirad, H.; Rahman, M. S.; Jeong, J. W. Targeting TET3 in macrophages provides a concept strategy for the treatment of endometriosis. J Clin Invest, 2024; 134(21), e185421. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, N.; Wang, J.; Huang, M.; Zhu, L.; Wan, G.; Zhang, Z. Exploring macrophage and nerve interaction in endometriosis-associated pain: the inductive role of IL-33. Inflamm Res. 2025 Feb 19;74(1):42. [CrossRef]

- Midavaine, É.; Moraes, B. C.; Benitez, J.; Rodriguez, S. R.; Braz, J. M.; Kochhar, N. P.; et al. Meningeal regulatory T cells inhibit nociception in female mice. Science 2025, 388(6742), 96–104. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, N.M.; Jørgensen, K.T.; Pedersen, B.V.; Rostgaard, K.; Frisch, M. The co-occurrence of endometriosis with multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(6):1555-9. [CrossRef]