There have recently been major changes in the pharmaceutical marketplace. Public sentiment has begun to shift against brand-name companies, with media reports detailing abuses of the patent system to stifle generic competition and rising drug prices. A grand bargain for overhauling the American health care system has been sought that preserves Medicare’s drug discount program and achieves substantial savings in the process. Controversies over price hikes of antiparasitic drugs and other medications have raised questions focused on social justice and fairness, rather than the details of pharmaceutical knowledge production and production processes.

The American market for prescription drugs has been an example of market capitalism. The industry has innovations, productivity growth, rising output, and returns to investment that exceed those of other industries. New drug approvals have been as numerous as any previous period, indicating an openness to new investments generally. Unless the inquiry uses a newly acquired evidence base, it will likely sidestep long-term, chemically based horizons and focus instead on immediate, near-term price changes, marketing shifts, and regulatory responses. The latter strategies are the ones which the American industry is well-equipped to handle. The former strategy uses external forms of evidence to search for shifts in the industry itself that might explain a change in business performance.

An internalist approach which relies only on published research of the industry will miss the mark concerning certain medications but will have room for pricing analyses. Absent certain advertisements, many in the U.S. would never be aware of its existence, issues or choices. While experts have identified niches in which pharmaceutical branding could waste significant amounts annually, none with that heft have suggested that pharmaceutical branding should be eliminated. Many still see promise in innovation. US consumers pay too much for brand-name drugs. Ultimately, pharmaceutical trademarks and trade dress may be a market failure which plagues the pharmaceutical industry and their patients with unnecessary costs, prescriptions, and side effects.

Overview of Brand Medicine

Brand medicine plays a central role in making new pharmaceuticals widely available. With patent protection, there is a monopoly on a new product. The brand, through marketing, creates top-of-mind awareness, preference confidence, and, eventually, demand. Marketing must also create awareness and results that stimulate assumed consumers—by defining wealth effects. Medicine costs only a small fraction of GDP and price elasticity is high. Demand stimulation produces welfare maximums as volume benefits total welfare better than high prices (Kanavos et.al., 2011). Marketing is a focused investment with major benefits to the brand firm. The “plan” is a 30-year cycle of innovation, patenting, and marketing of a $1 billion investment. Patients are only diagnosed and stimulated to seek treatment for advertised conditions. For allege ache, awareness in a month rises to 30% with a Marketing Mix impact factor of 100. A seeking consumer is influenced to the used brand (75% probability) by peer/advertising perception for every diary insinuated. Brand awareness creates demand at the doctor’s office Socal et al. (2021).

With knowledge of top brands, consumer control works on specification. Acceptance grows from only a few doctors to widespread acceptance by most doctors (80%) and “normal” professional preferences. Due to supply and information deficits, lower prices arise through tiers. With public influence on doctors, prices converge to the tier in the extreme left. At full influence, return on profits is a few percent, but brand medicine provides a few hundred percent return to multinationals. Off- prescription indications must include risk factors that tier the brand (e.g. diabetes/class II a risk). New brands must swim upstream from price-determined “hard” to “soft” usage. Information effects add brand tier and substitution greatly affect margins (loss of α). Factors affecting prescribed firm medicine in the Medicare Part D program were evaluated.

Historical Context

The term brand name drugs (also called branded or innovator drugs) refers to pharmaceutical products that are protected by patents legally enforced against generic competition in most industri- alized nations Kanavos and Vandoros (2011). Brand drugs represent the original prescription drugs marketed under proven trademarks. They are usually patented pharmaceutical products produced by a large pharmaceutical company that has an exclusive right to market the product for a certain period or until patented in various jurisdictions worldwide. A new product with exclusivity based on filing of new chemical entity or formulation is branded under various names by the innovating company (Oriola, 2010). The patent gives the firm an exclusive right and the immediate incentive for further investment into the clinical development and marketing of the new product and production of a profitable monopoly pricing strategy. After the patent expiry, people lose the exclusivity of brand name, and an innovator drug becomes off patent. It is at this time; various generic manufacturers seek registration of the product and introduce their own generic version of drug at lower price. During the patent life, there are various probabilities of ‘Paragraph 4 patent challenge’ (US definition), when a generic firm decides not to infringe the patent or design around the process of manufacture of drug without copying the original. At this stage, or earlier, some measure of reverse engineering is carried out leading to chemist or bio pharmacists having the keep well and launching a generic equivalent or counterfeit brand.

Brand name drugs can be classified into two primary categories: innovators and counterparts. This classification depends largely on their exclusivity in the market and their respective patent positions, which determine how long a drug can remain protected from competition. Brand name drugs can also be further divided into therapeutic and corporate counterparts, which are distinct from generic copies that may structurally or functionally vary from the original brand drug. These counterparts can include instances of therapeutic duplicity, in which a generic firm might replicate the patented product, essentially the same innovator drug but utilizing different methodologies, formulations, or delivery systems that may alter its bio activity or overall encapsulation design. For example, certain firms may produce a reformulated version of the original product for the purpose of expanding its market reach, often in the name of the same marketer, leading to potential confusion among consumers regarding the efficacy or safety of these products compared to the original. Innovators might also introduce reforms, which could include extended-release formulations, enhanced solubility, or other membranous product designs aimed at improving patient adherence or therapeutic outcomes. Additionally, acquisitions play a significant role in this market, where a corporate parent may acquire the rights to a marketed drug, thus creating a corporate counterpart that maintains the brand name but differs from the original formulation or intent. In this context, the study of brand name drugs within India becomes particularly relevant, especially given the ongoing evolution and reformation of intellectual property drug policy in the country. This evolving landscape seeks to balance safeguarding therapeutic biotechnology and promoting access to innovative medicines, underscoring the complexity of the pharmaceutical market and its impact on public health and access to care. This analysis delves into the intricate dynamics that characterize the brand name drug sector in India as it navigates these changes and challenges, providing insights into the implications for healthcare stakeholders and patients alike. Grabowski et al. (2021).

Market Structure and Competition

This section discusses the organization and structure of the pharmaceutical industry and considers what measures need to be taken to ensure effective competition in the pharmaceutical wholesale market. There is also some discussion of how these proposals might be implemented. An important aspect of competition among pharmaceutical manufacturers is the ability to make changes in the marketing mix. In its broadest sense, the marketing mix encompasses all the marketing activities that a company pursues in the pharmaceutical industry. A crucial aspect of the marketing mix is the marketing strategy itself, the decisions that management makes as to the products that are to be marketed and the objectives that are to be achieved in the regard Danzon and Chao (2000).The salient characteristics of pharmaceutical product marketing are described. There are four common marketing mix decisions: Market share, price, advertising and promotion. These marketing mix decisions are interrelated, but the marketing strategy framework can be employed to identify the decision variables as they pertain to new product introduction, product termination, product price and advertising or promotion. The constraints and difficulties faced by incumbent companies in product market entry and removal are then outlined. A literature search reveals that several scholars have investigated alternative aspects of the pharmaceutical product market structure, including competition and advertising. There have also been substantive discussions concerning the efficacy of advertising and promotion in increasing product awareness and stimulating demand David2011.

Assumptions are made that underlie the marketed products and the competition. Examination of the dominant product and the related competitors in turn, with similar discussion applied for indirect competition, is conducted. A flow diagram is presented showing the overall structure of the system and the functional designs or blocks inherent in that structure. Reference description is provided of the main components of the diagram, in particular, the decision sectors of the firm and a description of how the control variables work with the appropriateness measure to affect the firm’s objectives. The proposed model espouses positive and normative perspectives. Exogeneity of the exogenous variables of the model is indicated and estimation procedures for the endogenous variables are described along with the data sources employed. A list of variables used in empirical work is also appended.

Pharmaceutical Market Dynamics

In 1900s, brand medicine were essentially US market imports, well over 80% of the value was controlled by US firms with the rest dominated by Switzerland, Germany, England and France Daemmrich and Mohanty (2014). Ex-communist make-over of 160 pharmaceutical factories was no small task; many feared that unguarded application of Western economic institutions to the health needs of poorer countries would unduly favor already-rich pharmaceutical manufacturers. Expected flow of drugs to the needy third world was supposed to lift off the financial strangle-hold that these giant firms had, nevertheless capital flight, not drugs were the result of inviting capitalism into public health.

Poverty was often blamed for the considerable difficulty encountered in the process of importing patent-protected medicines, and this was further compounded by the presence of a few well-publicized wealthy individuals who seemed to have no trouble acquiring these essential drugs. In the mid-1990s, America faced an unprecedented drug shortage that was of a kind nobody had ever thought would arise or warranted even the slightest concern before. It appeared as if a lawsuit against the regulators had inadvertently resulted in the de facto closure of numerous pharmaceutical production facilities across the board, which was certainly alarming indeed, considering that maintaining a steady and reliable flow of medicines was something that no entrenched bureaucracy had ever believed to be their legitimate responsibility or concern up until that point.

As more and more drug prices came under heightened scrutiny and public attention, the debate quickly turned to the vital issues of competition, regulation, and the broader implications for the entire healthcare system. This urgent discourse was all driven on by mounting and relentless voter complaints about the skyrocketing prices of essential pharmaceutical benefits. The commercial use of patented drugs, including those that were originally discovered and meticulously developed through significant public sector research funding, was increasingly believed to foster an environment all too conducive to price gouging and exploitation. As a result of these concerns, various medical non-profits and government entities were transformed into crucial platforms for proactive attempts at controlling the process in ways that would effectively continue to maximize the flow of much-needed funds into the United States economy. This pivotal situation occurred all at a time in recent history when savings from soaring healthcare costs kept eluding meaningful regulation and oversight. Consequently, this situation remained frustratingly anonymous and out of reach for a significant number of citizens and consumers who desperately needed affordable healthcare options. Stacciarini (2023)

Role of Generic Drugs

While a chain of manufacturers frequently sells the same generic formulation in certain markets, in other markets, especially smaller ones, the generic market may consist of one or two active suppliers. For instance, although two different generic-state suppliers exist in Spain, one is contemplating leaving. An analysis of the generic drugs used in this study’s expenditure and price figures, the countries analyzed are the six largest European Union countries and the United States, reveals the effect of the market chain structure on prices and expenditure levels. The original drug markets, which enjoyed near-monopoly active supplier status, lessened their persistence relatively recently, as structural changes began to occur in the USA in the late 1980s and in most European countries in the late 1990s Oliver2017

With a reduced number of active suppliers in the industry, drug prices in the generic market continue to remain elevated when compared to the generally lower drug prices observed across the European Union. This situation holds true not only for markets that are less competitive, where a single supplier tends to dominate the landscape, but also in markets that feature only one or two suppliers. However, it is important to note that the difference in generic drug prices seen within the EU cannot be explained solely by considering the overall number of active suppliers present in the market. A positive relationship in pricing across various markets, which has been identified in previous research conducted in this field, continues to be evident. This ongoing trend provides additional evidence that supports the theory of partial price discrimination by generic suppliers in the market. These findings present significant policy implications for the generic drug market, and they are particularly relevant for shaping strategies and regulations within the specific context of the European Union’s generic drug market. Maini and Pammolli (2023).

Even where generics bid at around half the price of the brand version, this level has insufficient impact on aggregate expenditures unless the market is saturated with high-volume scrips. Intervention and pricing methods to reduce generically bought volumes will encourage blocked price increases. Additionally, manufacturers will increase prices if a risk premium develops. Finally, more price-setting competition is needed primarily at the pharmacy level and in the potentially excluded market of hospital extemporaneous preparation. In the USA, the entry of generics tends to complicate these matters, as there are dual entry modes: through abbreviated new drug applications and through the shorter processes, owing to the harder indirect acquisition of generic brands Danta and Ghinea (2017)

Brand Medicine Pricing Strategies

Strikingly, the pharmaceutical sector has attained outstanding revenues among most advanced markets. This demand for the pharmaceutical markets worldwide, especially for branded pharmaceuti- cals in the US market, might be driven by firm-level profits like research and development (R&D) flows and advertising of pharmaceutical firms. This, along with the exploration of how the determinants of revenues in advance markets such as the USA influence profits and prices in other firm markets, has gained greater interest. Little analytical work on the determinants of drug prices in OECD countries has dealt with the effect of branded drug advertising. Denoting correctly on differentiated drugs by themselves, the potential market stimulant on branded drug expenditures in advance markets and drug price influences in developing countries has typically been overlooked. An understanding of how firm-level factors of branded and generic pharmaceuticals affect revenues in 31 OECD markets might yield new insights into commercial operations in the pharmaceutical industry and the impact of revenue fluctuations in advance on prices and profits in developing countries Kanavos and Vandoros (2011).

The early 1990s heralded successful sales, marketing, and manufacturing strategies praised and imitated by several industries. Branded drug names have widely been perceived as an indicator of quality. Brand differentiation, moreover, incentivizes patent-holding firms to leave the monopoly market to discourage other drug firms from entering the generic market whilst pursuing price mainte- nance strategies. Descriptions of pre-1880 branding to identify individual brands through names or geographical origin and process until mass production and marketing automation in the terrestrial industrial revolution. Trademarks for identifying origin in the nineteenth century finally became a crucial preventive for firm entry in the 1900s. Yu et al. (2022)

Pricing strategies of branded medicines in the US market dictate most of the overall selling prices of branded drugs worldwide. Brand medicine pricing strategy initially sets net selling prices-of- list prices to customers-cognizant of their individual characteristics, notably scientific, marketing, or competitive. Prices might reflect directly drug lists divided by marketed display vineyards after discounts that are imposed. Brand medicine pricing strategy might decide on high list prices, especially when little or no competition traces or branded firm profiles are low. Price transmission from this level to consumers and consequently to net profitability and drug consumption take longer than the initially set price of marketed drugs. Nagle et al. (2023).

Impact on Healthcare Costs

FDA’s implementation of a shortened regulatory approval pathway for generic biologic came as an intriguing surprise to many observers of American healthcare. After all, approval of a generic competing product for a large bio pharmaceutical seemed difficult, if not impossible for many years. The industry’s arguments were compelling, led by Massachusetts’s Senator Edward M. Kennedy and the Bush administration’s director of the Office of Management and Budget.

As the U.S. becomes the largest producer of life-saving biotechnology medicines, it is equally important that patient access be facilitated without sacrificing public safety. Nevertheless, the growth of biotechnology medicines has also led to concern for high drug costs and government drug spending, as well as the need for patient access to these cost-saving biologic. Legislative measures have been proposed that would create a regulatory approval mechanism for bio generics or follow-on biologic. The Hwang proposal, for example, seeks to allow for the FDA to approve bio generics with fewer clinical trial data in certain circumstances. This proposal is not without critics, however, who ar- gue—subscription guidelines should be made stronger as safety regulations must not be compromised and as safety regulations must not be compromised. Some have pointed out that drug markets are accurate indicators of innovation. One analysis concluded that a small decrease in protection will lead to a much larger decrease in RD investment and the flow of new drugs. Using these insights, objections to the establishment of a bio generic approval route will be considered. Legislation is urged that will protect the bio generics industry from anti-generic legislation as well as excessive patent protection Danzon and Soumerai (2002).

To explore these issues, prescription drug expenditures in the U.S. are placed in the context of total health care spending and spending in other developed countries. Major external and internal analyses of cost-constraining policies are described. The current focus on drug price equity will be addressed as a probable cause of increased health costs. Public prices of patented pharmaceuticals in the U.S. are compared with other developed countries, and pricing and cost recovery systems in the U.S. are described. It is concluded that the current public policies thereby structure strong incentives for price discrimination and gaming by firms, foregone benefits or savings to achieve price equity in at least one of the market segments, leading to the public policies. Levi et al. (2023).

Direct Healthcare Spending

Healthcare spending is the largest expenditure category for both federal and local government and employee fringe benefits. Within healthcare spending, drug spending accounts for an increasing share over the late 1990’s and over a considerable share across states. The difference is due to far higher Medicare spending on drugs in states with higher drug expenditure levels. Cross-state variation in total drug expenditure, on the other hand, is largely accounted for by differences in private sector drug expenditure and is not strongly correlated with Medicare drug expenditure and drug coverage differences. The time series pattern of total drug spending change also differs notably across states, with slower growth in several Southern states. The executive interest regarding spending on drugs, specifically, brand drugs generated sizable revenue, but far more than generic drugs, placing patent- infringement exposure on drugs with significant, measurable revenue Danzon and Soumerai (2002). This major expenditure category has risen faster than overall health care spending in an unprecedented manner over the late 1990’s and raised a concern among politicians about cost containment for widespread health care coverage as prescription drug coverage is added with limits to federal spending on it. The fact that drug spending growth outpaced health care costs is well documented, and an estimate of annualized rates of growth for total and prescription drug expenditure from 1990 to 1999 is that total spending rose almost two-thirds and drug spending rose far more. Owing to this asymmetry in growth, drug spending grew as a share of total health care spending, and drug expenditure at about 10 percent of total health spending would be seventh among health care expenditure categories in dollar amount. Empirically, state analytical units in 1995 totaled more than ten thousand and enlarged to about twenty thousand in 2000. Such a difference will yield insights about the nature of the spending change. Cross-section data on the expenditure levels for 1995 were provided and estimates of spending change for the next five years were investigated. Vanness2021.

Indirect Costs and Economic Burden

Because most of the research done with PATs focuses on direct costs, much of what is known is with direct costs. However, the effects of PATs can be much more extensive than just the direct costs related to emergencies and losses of work. Indirect costs are generally losses, which innovations, policies, or acts hold back in terms of missed profit. In the case of prescription drugs, the perception is that their use or patent protection casts a shadow on on-market goods by holding up their potential profits. This shadow has been shown to incur costs associated as high as 382 trillion dollars annually. This mainly accumulates through health care costs from diseases that an innovative drug is protecting against. Just like the economic burden of a disease is the sum of all costs that that disease incurs, the economic burden of the shadow that it casts on on-market goods is the sum of all economic impacts where a patented good holds up the innovation of an on-market good.

Research into the economic burden of a shadow that originated from the use of PATs on the market for prescription drugs has been limited. This would require in-depth studies of the AD for good’s patent prices derived from the paper. Through simulations, opportunity costs are determined and reported here. These opportunity costs are limited to lost profits in sales of the on-market good. However, there are also other economic impacts associated with the economic burden like health care cost, welfare loss, or the underground economy.

With these assumptions of the economic burden, an experiment is set up to determine the economic impacts on the USA prescription drugs market. This is done by simulating a specific case. A new crop of good A is introduced to market causing other on-market good B to incur patent loss for several years. On the prescription drugs market, these goods are represented with drugs A and B being specified on a basis of the chemical compound they use to produce their effects. PAT 1 can be claimed by drug A to protect its profits and Drug B will be losing profits to this protection, meaning it is losing its right to profit from selling the drug in the market Bebo2022.

Consumer Behavior and Brand Loyalty

The economic effect of brand medicine on the American economy is a complex and multi-layered issue. Constantly changing elements of the economy, government and external factors affect it, which in turn influences consumers and suppliers. Some of these elements are more vulnerable to the effects of any event than others. Because of this, the initial anticipatory thought is that consumers and the companies that supply them will "experience" and feel effects that are most relevant and detrimental to them. However, it is only on closer examination that it becomes plain to see that both consumers and suppliers will experience a loss from minimal to great depending on what area is being discussed. The direct expectation on the American vaccine market would be that vaccines will remain brand- named products. Because consumers know that an effective vaccine is a good first step to achieving herd immunity worldwide, they will start by asking their healthcare professionals about the brand or formulation they should get vaccinated with. This is especially true in the case of mono-branding of the vaccine supply, as is the case with many of the vaccines developed for the current coronavirus 2019. Consumers also seem to trust their healthcare professionals more than pharmaceutical companies, both in the knowledge they have and questions they can address. Consumers would then form a brand with all possible measures: satisfaction with the overall healthcare professional and their expertise, trust in the effectiveness and safety of the drug they took, and the extent to which they perceived it as an inevitable option whether through governmental pressure, peer pressure or both Rozani2014.

The general expectation on pharmaceutical companies as suppliers of vaccines is to offset their losses in innovation and upper-holding in high-income developed markets with increased sales in low-income developing markets; This means a loss for the American market, as all the vaccines should be exclusively purchased by the federal government, which would end up paying much less on a per-dose basis than with deals made with the companies themselves. All intellectual property is then transferred from the American to the general market, and eventually all-American companies will regrettably consider cutting back their efforts for vaccine research and development in favors of market segments with better potential returns.

Regulatory Environment

Prescription medications in the United States are regulated as both food and drugs by the US FDA under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA). The process of bringing drugs to the marketplace is a complex one that encompasses a diverse set of fields, including research, formulation development, manufacture and delivery of the product, establishment of quality control parameters and processes, stability studies, human or animal testing, an analysis of the market factors for the drug, and finally, an analysis of the economic factors for a new drug. All prescription drugs in the US must include a label that has two major sections: the information needs of the medical professional (the prescribing information), and the information needs of the patient used by the medical professional in informing the patient.

A prescription drug is defined as a drug that is not safe for use except under the supervision of a licensed practitioner–a physician, dentist, veterinarian, or other practitioner licensed by law. A prescription drug is deemed to be unsafe for self-medication because unwarranted use can result in danger to the health of the user due to toxicity, the need for professional supervision in the diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of injury or disease, or the complexity or danger of the drug’s use which requires professional supervision Kanavos and Vandoros (2011). Most drugs may be purchased either with a prescription or over the counter; however, certain drug products may only be offered through prescriptions from licensed practitioners.

Under the Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987, the States have been given authority to establish marketplaces within their borders wherein prescription medication may be returned for credit and/or replaced with a substitute on a one-for-one basis. In no instance are drugs permitted to leave the marketplace unaudited and unregulated. The Act also mandates that all prescription medication leave the marketplace through an approved facility. The responsible and safe delivery of medication from the manufacturer to the pharmacist/dispenser/doctor involves a complex process regulated by both the US FDA and the laws and regulations of the States in which the prescription medication is sold and/or distributed. It is against the law for any prescription drug to be sold in the US unless it has been manufactured in compliance with a current good manufacturing practice. Current good manufacturing practice is an extensive set of regulations that governs the manufacture, processing, packing, and holding of finished pharmaceuticals.

Regulatory actions of the FDA concerning prescription drugs fall into two major areas: therapeutic post-marketing issues and enforcement issues arising from cGMP deficiencies or failure to comply with an NDA. FDA actions range in severity from warnings and consent decrees to seizures and injunctions, but the ultimate sanction of imprisonment is rarely used. Regulatory actions against sponsors involve state laws against false advertising and actions in tort for fraud.

FDA Regulations

Legislative reform must address the notable absence of regulation requiring pharmaceutical companies to make explicit that the off-label uses approved in other countries differ from that of the FDA-approved indications in the United States, how that can potentially lead to treatment misappli- cation, and how greater due diligence is warranted when reading drug information not sanctioned and published by the FDA. With such advertising, risks are minimized for pharmaceutical companies and misapprehension of a drug’s safety or efficacy in each indication exists. Most extreme would be “promise” advertising by pharmaceutical companies for products that treat obstinate conditions where significant risk exists for ad applications beyond FDA-approvals. Risks for companies exist, though suspect, and most severe reform would require that a pharmaceutical company show that drug safety or efficacy has been established in the indication purportedly before its marketing is permissible Wang2012. This would serve to eliminate the specter of tragedy of the commons in the industry and grant consumers recourse from egregious misapplication of labels.

Further extreme would be tiered approach for labeling (brands that conclusively show treatment efficacy supported by rigorous scientific backing, then more general “unapproved but accepted” labels, and finally “off-label” labels that achieve much less empirical credence) that reflect evidence and experience warranted and avoid quagmires of either blocking helpful or allowing harmful information transmission (more narrow tiers would moot issues of standard label difference but fail to address voracity of the evidence and experience it purports to transmit). To level the playing field, such regulation must require similar recourse to states, and legislation enabling greater damage awards for false advertising with required evidence submittal to state regulators would solicit vigilance in monitoring from plaintiffs but protect against egregious risk from lie-laden advertising. Like measures would require greater transparency in and standardization among testimonials and headers regarding drug consequences.

Patent Laws and Exclusivity

Two kinds of patent laws apply to pharmaceuticals in the United States: The General Laws and the Hatch-Waxman Act. The General Laws grant a firm patent protection upon meeting the novelty, non- obviousness, and utility requirements, while the Hatch-Waxman Act is an amendment to the General Laws that governs the generic entry into the pharmaceutical industry. Any firm that develops a new composition of matter may file a New Drug Application and obtain patent protection in accordance with the General Laws. Once a patent is granted, the firm can take appropriate measures to exclude rival firms from making, using, or selling the patented drugs. The patent protection granted to the composition of matter formulation lasts 20 years after issuance. A patent-protect able composition must meet the novelty, non-obviousness, and utility requirements. Therapeutics developed from natural products and discovered purely by chance cannot be patented under the General Laws.

The Hatch-Waxman Act permits the firms to become generic manufacturers upon filing an Abbreviated New Drug Application with the Food and Drug Administration. Once it grants approval for the ANDA, the generic firm may market the generic formulation. To obtain an ANDA approval for the generic formulation, a firm must demonstrate to the FDA that the product is bio equivalent to the NDA product, that is, Cmax and AUC metrics of the generic formulation should be within 80 to 125% of those of the branded one. Upon the NDA, the branded firm is granted 5 years of market exclusivity for new chemical entity products or 3 years for new use products regardless of patent status. For patented drugs, deletion of that patent claim also allows ANDA approval. When generic firms file an ANDA, a 30-month stay against approval is invoked and that 30 months can be extended to 23 months as requested by the court. When heavy penalties for supply of products are imposed, the generic firm cannot be hindered from contesting patent infringement. Since generic products typically command a much lower price than branded products, this subsequent generic entry incurs a large welfare increase. Delayed ANDA approvals do not go hand in hand with filing waves, due to asymmetric regulatory compliance and heterogeneous entry cost. If the patent is for a composition of matter or a method, first ANDA approval prerequisites patent expiration without any 3-year exclusivity. If the patent is for the metabolite, some granted patents can make the branded product more valuable in entering the new market. Discoveries from recent ANDA approvals encourage other generic firms to circumvent 3-year exclusivity and cause a prolonged exclusivity period in brand price erosion. Thus, absent FDA interventions, market simulation with derivatives can quantitatively estimate lengthy patent-induced time profiles. These findings provide policy insight for untangling the patent extension practices considered by the industry. PA2021.

Literature Review

Patent law provides innovations with a limited time monopoly (20 years on average) after which generic alternatives can come to market and compete for market share. This patent expiration is a key factor in determining the pricing behavior of these medicines in the United States and Europe. Some economies, such as those in the United States, have a much longer period of brand exclusivity after which branded generics do not emerge. Even a decade after patent expiry, prices may be considerably inflated. Price differences between brand name prescription medicines across economies are substantial, ranging from 337% higher in the United States to as low as 32% of the average price in Greece. The existence of price differences across markets when patent protection holds and subsequently price convergence after patent expiry is seen as proof of product differentiation, brand loyalty and manufacturer price discrimination. However, some states regulate prices prior to patent expiry and have instituted uniform pricing legislation prohibiting price discrimination across markets Jha2023. Upper prices have also been instituted. Additionally, some countries enforce deals with manufacturers promising the supply of the cheapest generic alternative. Several regulatory options available to procure medicines at lower prices are reviewed. Lastly, some nations’ price regulation and intellectual property rights protection nudge innovative companies either exaggerate or twelve months ahead of patent expiry switch production from innovator to cheaper generic substitutes. Indeed, many firms observe and react to U.S. price changes. Other aspects, however, remain unexplained. While there is unarguably a level of opacity, the data still provide some insight with respect to pricing variances at the launch of a product as well as pricing alterations after one year. For those issues that direct data is not available, further, ideally qualitative, research is needed. Michels2025

Previous Research on Brand Medicine

The price of medicine is determined by many factors, including the general economic environment, the provider of the service, insurance coverage, and the patient; as well as by other factors that are unique to the pharmaceutical market. High medication prices can place vulnerable patients at risk for acquiring their medicine. The economic impact of brand name medicine is felt strongly from the first moment a medication is used and felt by all individuals in similar economies. In the US, where brand medicine comprises almost 60% of the dispensed prescriptions, it could be one of the most researched topics today. This section will provide a starting point to understand the economic impact of brand medicine and its other effects on the life of individuals by exposing some of the previous research done during the past few decades. Research done after the authentic era that studies the price of the branded and generic medicines are plentiful. For example, thorough research of the price of over 60 branded prescription drugs and their generic counterparts across different countries was conducted and published in 1. Outside of the US, launch events were studied and the effect of those on the price of generic medicine was researched. The economic effect of brand prescription medication was also studied through the lens of Health Reform and demonstrated that this prescription behavior increased healthcare costs and improved health disparities Volpi2020. After the first day of post-patent expiration sale of generic medicine, the pricing trend of generic medicines and changes in the number of competing suppliers were examined, while also analyzing whether marketing studied in the non- pharmaceutical market can influence a consumer’s perception and willingness to pay on a prescription medicine brand with a competitive generic.

Case Studies

Metronidazole, the distinction between brand and generic medicine is seen on biochemical and formulation grounds. On the biochemical stability, different manufacturers of metronidazole produce different medicines. Metronidazole is used to treat infections caused by bacteria that live only in anaerobic or low-oxygen environments, also by parasites. The brand Naftin is the world’s first cream used to treat infections against tinea, a topical antifungal cream that is applied to the skin. It is used to treat athletes’ foot, jock itch, and ringworm. Specific mention should be provided to Tazocin & Entecavir, which have worked wonders in price reduction for cancer and liver disease.

The analysis finds that branded prescription medicines contribute to the economy by supporting jobs, economic output, innovation, and tax revenue. Chain and independent pharmacies contributed more than $561 billion to national economic output in 2015, a leading contributor among the healthcare sectors. Over 2015, $60 billion of the economic output from pharmacy-related businesses was in state and local tax revenue Kanavos and Vandoros (2011). Direct and indirect jobs supported by chain and independent pharmacies are about 4.4 million, and traditionally mean jobs and in related pharmaceutical industries are about 2 million. The direct jobs are in retail pharmacy, plus in other local chain and independent pharmacy-related businesses.

National job impacts of prescription medicines were measured through direct employment, indirect employment, and local jobs. The analysis finds that full-time national employment supported by branded prescription medicines across the supply chain are about 4 million jobs. Two types of jobs are specified:

1) R&D, manufacturing, and wholesale distribution jobs employed directly by branded pharma- ceutical manufacturers.

2) retail pharmacy-related jobs filled in pharmacies, pharmacy benefit managers, wholesalers, and pharmacy-related businesses.

The direct employment supports over one million jobs, while two million indirectly support jobs and in-line pharmacy-related services. Economic impact is also seen in state and local taxes in connection with national job impacts of brand medicines, which revenue amounts to $164 billion.

Successful Brand Launches

There were more than 600 branded medicines successfully launched in the United States during 2005–2007. New medicines launched in 2005 were significantly larger than those launched in 2007. The American economy was the original market for 80 percent of medicines successfully launched during this period. On average, branded medicines successfully launched in the United States between 1997 and 2007 had a modest market size of USD 280 million in postlaunch year 2. The top 10 branded medicines accounted for more than 70 percent of total sales in post-launch year 2. The size of the market after the launch of the new medicine was significantly and positively associated with two strategic decisions regarding pricing and marketing investments in the United States. Cumulatively, the eight pharmaceutical manufacturers accounted for most sales of new branded medicines into the entry of generics.

The number of branded medicines commercially launched during 2005–2007 in the United States was larger than in Canada, and the United Kingdom (UK), but all other countries lagged further behind. More than 30 different branded medicines were newly launched in the United States over these years, which is not only a source of pride but also a boon for hospitality and tourism. Branded medicines nil-or-lowered priced the United States at launch acquired a larger market size than that of brand medicines launched on English pricing. In line with, the actual price at launch was also found to be significantly impacted by the scale of recent generic entry and branded collective internationally. Branded medicines newly launched in the United States during 2005 were about USD 10 million larger in market size than those launched during 2007. Results suggested that there was some substantial difference in the competitive environment between branded medicines newly launched during 2005 and those newly launched during 2007, at least for branded medicines in the considered cohort. that new medicines consistently launch in markets where competition is expected to be least severe may be more applicable during recession times. The first 10 months postlaunch years for the analysis of the American cohort yielded a moderate decrease in number of competitively marketed medicines, since two marketed branded medicines were displaced by generic versions Kanavos and Vandoros (2011)

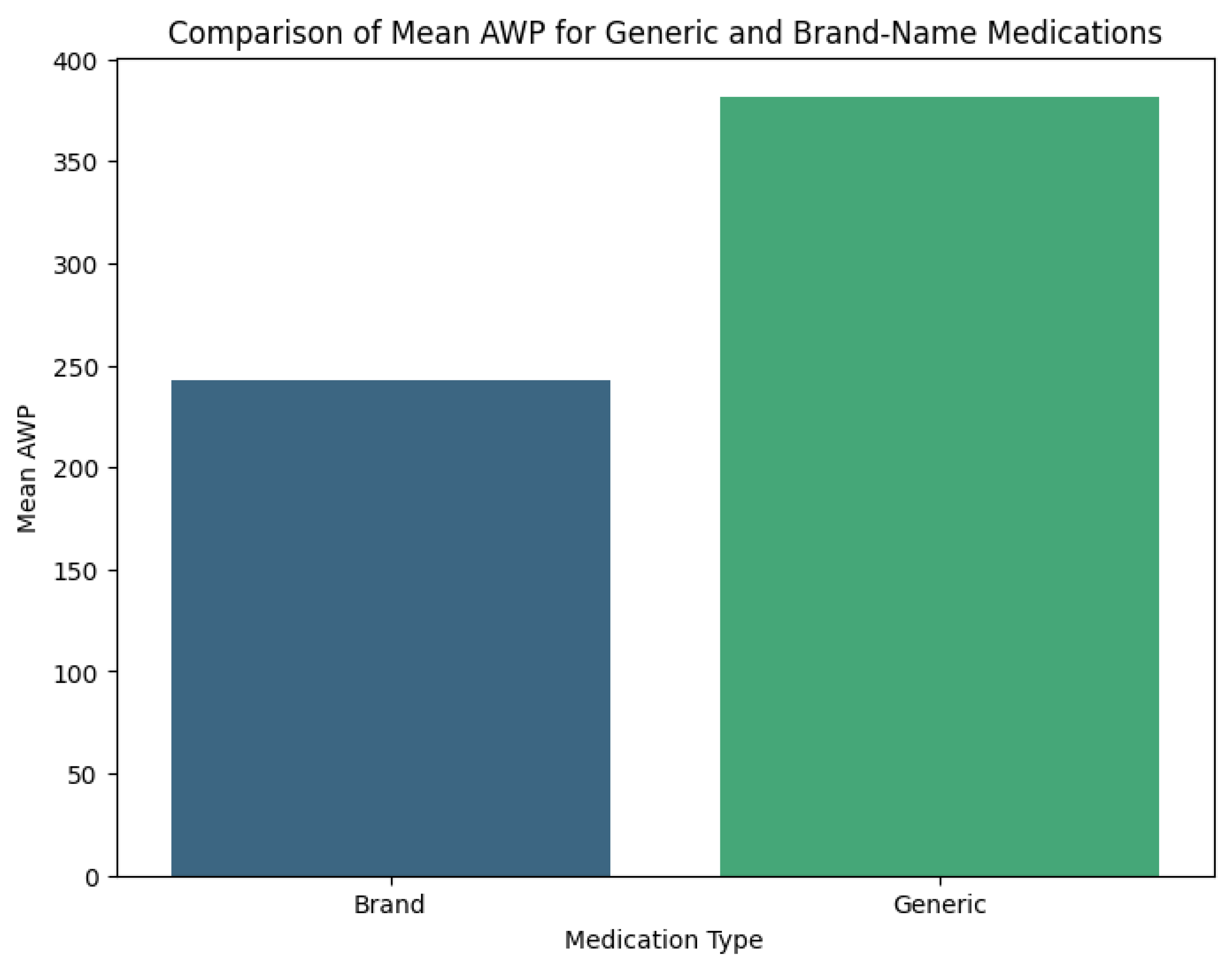

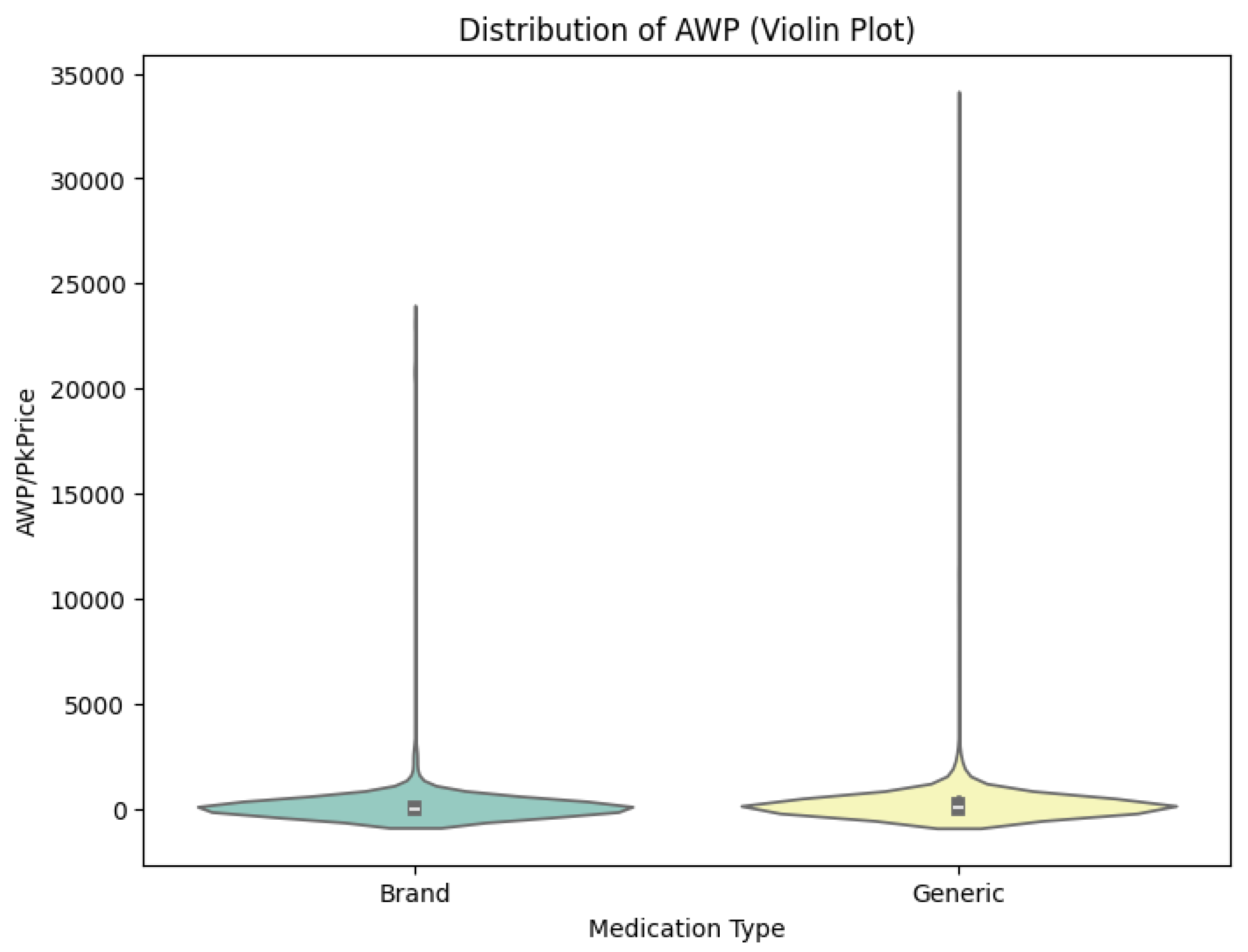

Comparison of Brand medicines vs Generic Medicines

To derive the average current cost per tablet (PCT) for brand and generic medicines, data on sales and pharmacy prices were collected from three Johannesburg pharmacies between 1st September and 12th October 2016. The PCT for each brand was determined, with prices for RM 2 generic counterparts noted. Price differences (PD) per tablet were calculated using PD = PCTBrand–PCTGeneric. Data analysis involved Stata, focusing on descriptive statistics and t-tests for equality of means based on gender and education. Among 201 respondents (69.7% female), ages ranged from 18 to over 50, with half having only high school education. The most common prescribed symptom was high blood pressure (48.3%).

Most respondents showed knowledge about generic medicines, with 69.2% acknowledging their bio equivalence. In the US, generic drug approvals save substantial healthcare costs post-patent. Brand drugs see significant price drops when generics emerge, saving the government from $73 billion in 2000 to $318 billion by 2012. Price comparisons need to account for packaging, as trends indicate generic market growth should reduce costs, but emerging strategies threaten stability. Statistical analyses showed a decline in generic pricing due to market factors. Caution is advised in aggressive price reduction approaches to prevent negative consequences. Recommendations for transparency in pricing and strategic understanding are suggested. The study examined cost differences between brand-name drugs and generics in the US utilizing public pricing data. The methodology included identifying NDCs for drugs, extracting pricing data, and performing statistical tests. Findings indicated new classes of drugs and post-patent generics enhance competition and decrease costs, despite manufacturer claims about quality. Welch’s T-Test was employed for statistical analysis of data. A quantitative survey was conducted in Romania, measuring health professionals’ and patients’ knowledge of generic drugs, with data collected from 417 individuals. The study calculated significant savings on generic medications compared to brands. Statistical findings showed significant cost differences, indicating a need for further analysis of consumer perspectives on generic drugs.

The FDA’s regulations aimed to ensure public health and safety, while consumer perceptions heavily influence generic uptake. Producers are encouraged to address misperception about generics via education and marketing strategies to improve acceptance.Studies indicated that effective market- ing and trust from healthcare providers play critical roles in promoting generics. However, the impact of advertising and pricing on consumer choices remains complex and warrants further examination. Notably, using generics instead of brand-name drugs could drastically reduce national health expendi- tures in South Africa, emphasizing the need to promote generic use across various healthcare sectors. Generics were used exclusively for the four most common medications $660. 23 million would be saved. This suggests that action is required at governmental, healthcare, and pharmacy practice levels to promote generic medicine use. The comparative efficacy of the use of generic and brand-name medications involves long periods of therapy, suggestion of alternative therapies.

Global Perspective

Although several countries, including Australia, Canada, and most European nations, have adopted various mechanisms to curb skyrocketing medicine prices and related health care costs, the United States appears to shield drug manufacturers from price restraints. Thus, due to negligible price regulation, the U.S. pharmaceutical industry employs a variety of marketing and pricing strategies that allow pharmaceutical companies to charge consumers much larger drug prices than any other country. Canadian consumers benefit from lower prices on prescription medicines than American consumers. A view of why this gap exists, and the consequences of this disparity on brand-name medicines and drug manufacturers, can inform federal discussions. The pharmaceutical industry annually charges American consumers the highest prices on medicines in the world, and these costs significantly contribute to the nation’s mounting fiscal debts Kanavos and Vandoros (2011). The industry’s expenses on each drug can exceed $1 billion from the idea’s inception to its patent’s expiration. Advertisers’ aggressive marketing techniques and inaccessibility to drug price solicitation encourage the buyers, insurers, and intermediaries to pay non-reduced prices. As the American populace continues to lose faith in the government’s capability to regulate the pharmaceutical industry, sentiments grow that perhaps the pharmaceutical industry should be democratized into a more socialistic economic structure.

Though the drug-price regulation landscape is rife with loosely defined territories, it is generally agreed that the Federal Trade Commission would likely dictate any upcoming regulations on drug pricing Brennan (2015). Thus, comparisons may be made relative to the niche that preventative health-care policies occupied prior to the Affordable Care Act juicing-up of the referencing mechanism. The sudden magnitude of said allusion inferences regards an FDA approval may likewise curb the incentive for pharmaceutical companies to manufacture brand-name medicines at all, leaving only cheap generics available for consumers firm enough to stomach the taste. As drug manufacturers have scaled down their development of brand-name medicines, the supply chain barriers into treaty countries theoretically remain in check, and any sudden price changes undermined by side agreements would inevitably fall back onto consumers.

International Market Comparisons

Business and academic journals have analyzed the pricing of brand-name prescription drugs comparing prices in the United States to the prices of other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. Most of this work is concerned with the determinants of prices and does not consider the economic impact of branded medicines on national or international economies Kanavos and Vandoros (2011) provide a model that attempts to analyze the price determinants of original brand-name prescription drugs using a sample of 1,033 products. This analysis brings to light some interesting facts about medication prices in the United States and other countries. A price in the United States cannot, however, be predicted without a good deal of error.

Pricing differences for the same medications in the United States and other countries can be very large. Brand-name drug prices in the United States are a mean of 5.729 dollars as compared to 1.022 dollars in the comparison countries or as compared to 1.723 dollars in the mean of the six largest nations in the European Union. In public price or ex-factory price view of pricing differences, average United States public price is about 3.564 dollars and average OECD public price is about 1.557 dollars. Starting prices in the United States are generally higher than starting prices in other countries. Exceptions are some products introduced in 2004 or later that have prices above the 90th percentile. A group of older products introduced in the 90th percentile have pricing above 90 percent in destination countries which is consistent with price discrimination discussions. There is evidence that initial prices have been increasing through time. For prescription drugs marketed in both the United States and other countries, the minimum United States price is generally higher than the minimum comparison country price which is a finding supporting price theory. Rome2021

Branded medicines have a significant impact on the US economy. In an analysis of the economic impact of branded medicines on the US economy conducted by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, results of initial calculations indicated that branded medicines represented nearly 200 billion dollars, or more than 12 percent, of the US economy. In turn, each dollar added to the GDP by brand medicines would contribute 1.24 dollars to the GDP. There would be an impact that would include effects of brand medicines in 6 other sectors such as basic, durable, and nondurable goods retailing: other information services, etc.

Discussion

Limitations

The gut-wrenching disciplinary gaps in the PDUFA era have been summarized here in greater detail than any investigator wants to recall. The scientifically dangerous and expensive changes that the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is asked to review candidly but cautiously here relate not only to those troubling decades of change, but also to retrogressive fallback. It did not grow the dramatically expanded FDA drug safety bureaucracies and the dramatically increased user fees under President Bush fundamentally, but partly on theories and assurances of the same kind and caliber that did, and that on one heart-stopping occasion skidded pensively, tardily, back to orbit requests to revisit historically in the user fee reauthorization hearings Wong2010.

The consequences were surreptitious public disbelief, disobedience, and disregard of tardily groomed and audibly mumbled mediately prepared declarations of achievement and resolve. The ADA gun ever sported all the budgetary plans and artifices that had evolved with the NLEA or indirectly with the detail-string, to become, quite appropriately, henceforth the sole focus of FDA attention. Almost trance-like sleep embraced the unchanging FDA outcomes on PDUFA drug safety Brennan (2015). The PDUFA era looks now to a legacy essential much of international and trade redistributor systems, factors, and controls, not only strictly a ‘figurative velvet glove, but also exercised on the surface of drug safety adversities. Fallibility-free evaluation amounting to trust, credibility, and morality complexity is statutorily difficult to muster and demonstrate at overzealous levels. A hope is expressed that this treatise on a soul-baring FDA might only inform scriptwriters, for some timely, prescient, and dramatic screen conciliation.

Future Studies

Over the next decade, one major projection is that government-patented drugs will lose exclusivity. This has usually resulted in the introduction of concurrent generic products in the markets leading to a dramatic decline in sales for the innovator. The market for these products in the developing world is more complex, as countries vary in their acceptance of imitation products. In China, three factors combine to create potential opportunities for reemerging patents filing new period of exclusivity. First, copy products have become accepted. Second, the underdeveloped brand of China has limited the penetration of brands. Third, increasing consciousness about intellectual properties has resulted in fast adoption of compliance with laws. The foregoing analysis of the pharmaceutical market leads to an interpretation of the current and future states of organization in drug production. The current rapid consolidation in brand medicines’ production and distribution is viewed as a path towards sustainable competition in newer molecular classes. Ahuja2021 Intermediaries are now collecting rents from parallel importing in Lower Price countries and re-exporting to Higher Price countries, resulting in poorer access for patients in countries without producers. Monopolistic competition arguments predict several equilibrial, often pointing to greater than optimum numbers of firms, as the downside of such an increase, leaving aside distribution firms. The equity issue of Lower Price countries is neglected. Generality may be obtained including freshwater lakes, airwaves, and philosophies, as well, although ocean fisheries have some special characteristics. If swamping occurs with equilibrium price increases in Lower Price countries the welfare loss in those countries outweighs the gain from increases in Higher Price countries if swamping does not occur. At closure, pharmaceutical price discrimination, as a subhead concern in health care, is best modeled using the general theory of price discrimination, incorporating a supplied profile and organizational issues concerning the mass of firms, distribution firms, product differentiation, and price-taking considerations. Models have become weighed down with accumulations, calls for goodness-of-fit invalidation, numerous world variables, and degrees of freedom and sense questions when variables appropriate in one economy are invalid when exporting to another. Good markets illustrate constructively the use of tightly constraining assumptions to achieve results in simple frameworks and focus attention on policy options for resolving potential conflicts of supply and access much as has occurred in the exchanges. Arora2023

Implications

The government of the United States and China is making efforts to create a pharmaceutical environment that meets the diverse needs of different stakeholders with competing interests. Both countries need to balance access for patients paying out of pocket for pharmaceuticals and incentives for firms to devote time and money to research and the development of new drugs. China is committed to improving access by creating a single reimbursement drug list with low prices, with cheap generics, generating pressure on margins for traditionally high-priced branded offerings. Research-oriented pharmaceutical firms face the challenge of meeting the government-set price for the drugs given their current margins and finding a way to build a market for their branded offerings. While the U.S. market is dominated by multinationals, China offers enormous opportunities. The fragmented generics industry offers low-priced drugs, but poor quality generates public fears of fake or diluted medicines. This inconsistency in manufacturing standards, however, also offers significant potential for the growth of branded pharmaceutical sales. The domestic drug sector faces competitive pressure to standardize manufacturing to meet the Drugs Administration’s Good Manufacturing Guidelines, upgrade facilities to meet standards, and invest more in R&D. Increased scrutiny of doctors’ sales practices has refocused sales efforts on top doctors. Song2021 Doctors and consumers are the main targets of industry marketing. Blockbuster drugs abound, with potential races for entry and share. Blockbusters include treatments for widespread syndromes like high cholesterol, diabetes, and chronic diseases like non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma, breast cancer, and Alzheimer’s. Increasing scope, competition will also include public benefits, attempting to prove lower-price generics to patients’ beneficiaries while raising quality and safety to government regulators. Benchmarking with documentation and decision making will be critical. Increasing health insurance is welcomed as growth. Recent negotiations reformed process and pricing under pressure from policymakers. A combination of expanding coverage, free-market prescription-drug pricing policies, and government support for biomedical research will make the U.S. and China the two largest markets for drug sales and industry R&D. Tawfik2022

Policymakers in both countries face similar medical environment issues. Decisions made will benefit doctors, insurers, patients, and the government. However, new approaches clash strongly with established familiar private interests. As health care costs and aging populations rise, access expands, and usage pressure mounts. Rising health care costs have a high profile in the budget planning of all countries. Contributing to the stability of the global economy, the globalization of diseases known only to developing countries until recently exerts similar pressure on the economic situation, such as the impact of diseases on recent growth trajectories and prospects. Calls for free drugs for people living with certain conditions provoke a bitter debate about the rights of new therapies effective against those conditions. Unmet medical needs are a universal problem of profit versus humanitarian needs. In an interdependent macroeconomic environment, rising incidence of previously developed countries’ expensive diseases in developing countries widens the pharmaceutical gulf. While tuberculosis is increasing in significance in Asia, cardiovascular diseases dominate the picture in the Western world, heightening health care conflict and opportunity.