Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Cross-Sectional Regression Tests

3.2. Asset Pricing Models

3.2.1. Prominent Asset Pricing Models

- CAPM based on the market factor computed using the University of Chicago’s Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) value-weighted index minus the Treasury bill rate (M);

- Fama and French (1992, 1993) three-factor model (FF3) that augments the market factor with a size factor (small minus large firms’ stock returns, or SMB) and a value factor (high book-to-market equity minus low book-to-market equity firms’ stock returns, or HML);

- Carhart (1997) four-factor model (C4) that augments the three-factor model with a momentum factor (firms with high past return stock returns minus low past stock returns, or MOM);

- Fama and French (2015) five-factor model (FF5) that augments the three-factor model with a profit factor (robust operating profitability minus weak operating profitability returns, RMW) and capital investment factor (conservative investment minus aggressive investment returns, or CMA);

- Fama and French (2018) six-factor model (FF6) that augments the five-factor model with a momentum factor;

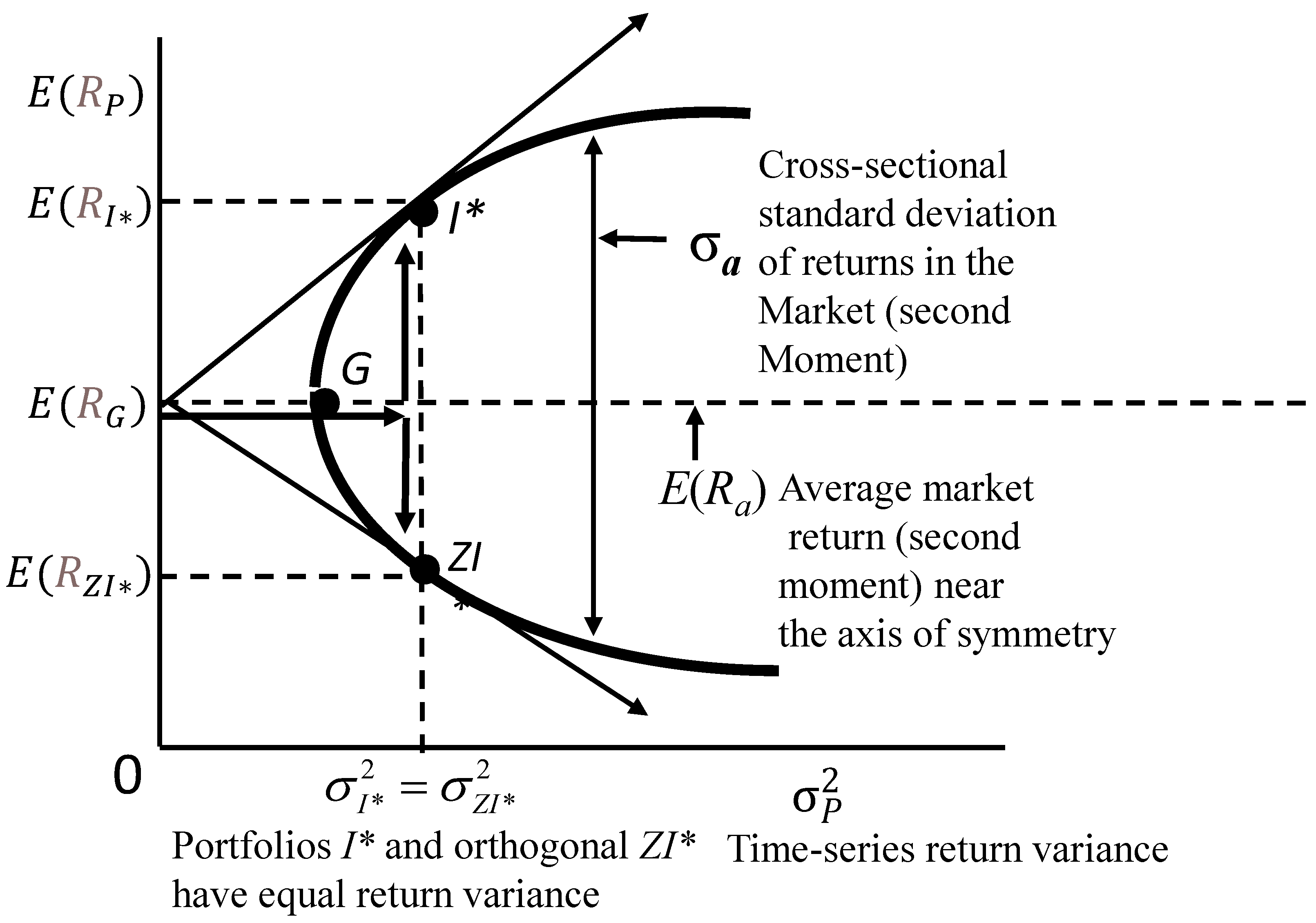

3.2.2. Overview of ZCAPM

4. Empirical Evidence

4.1. Cross-Sectional Regression Results

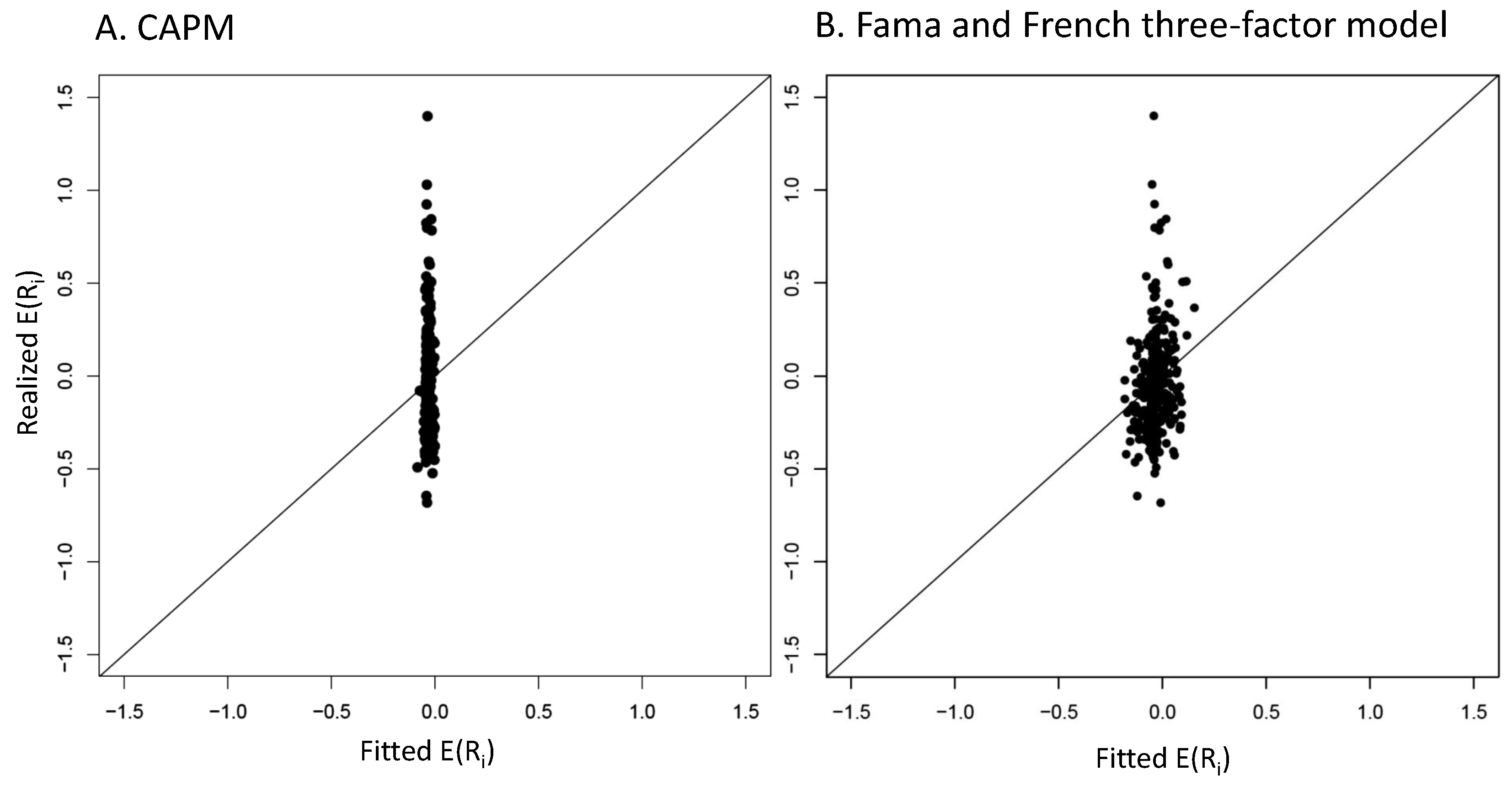

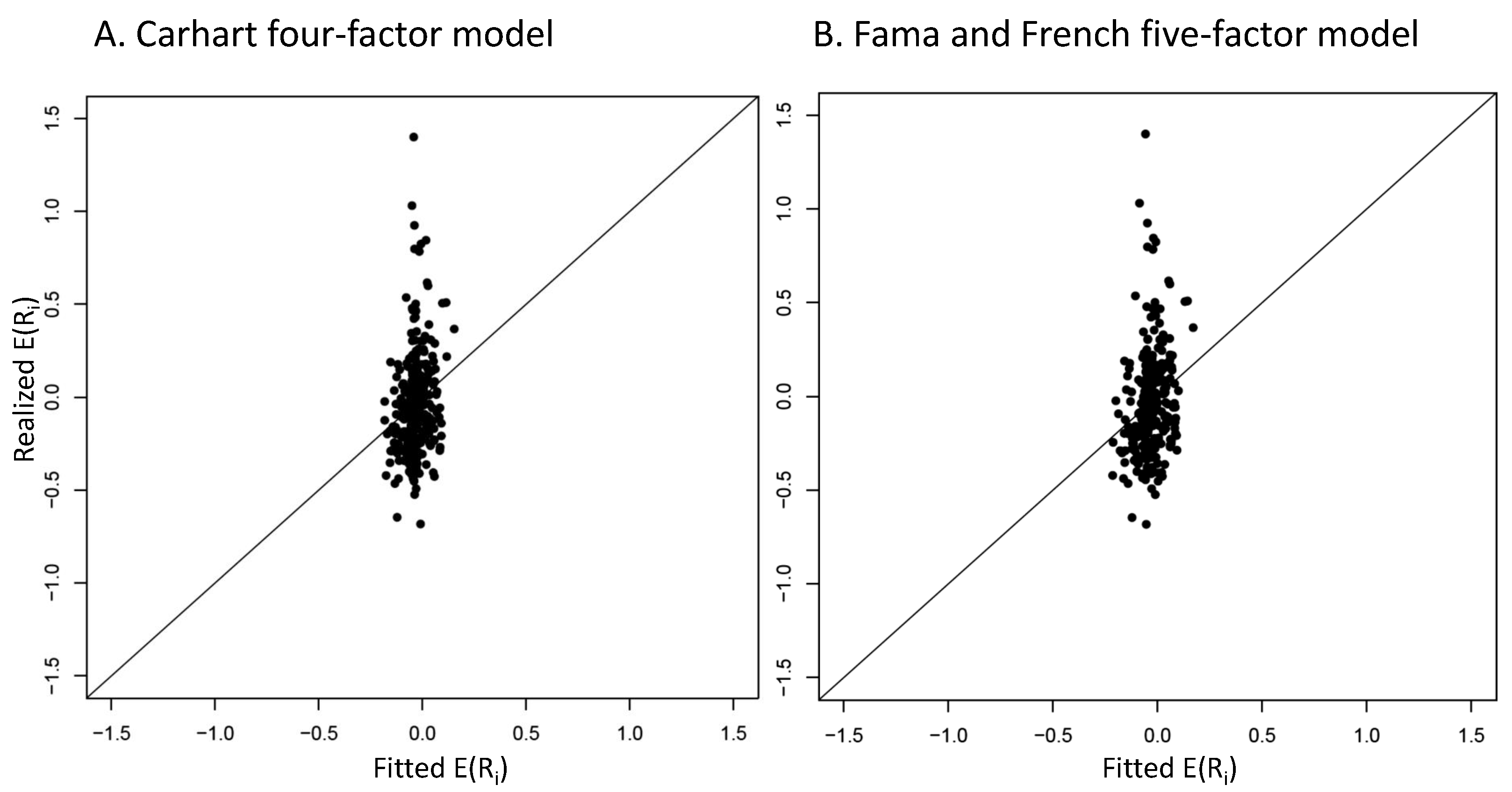

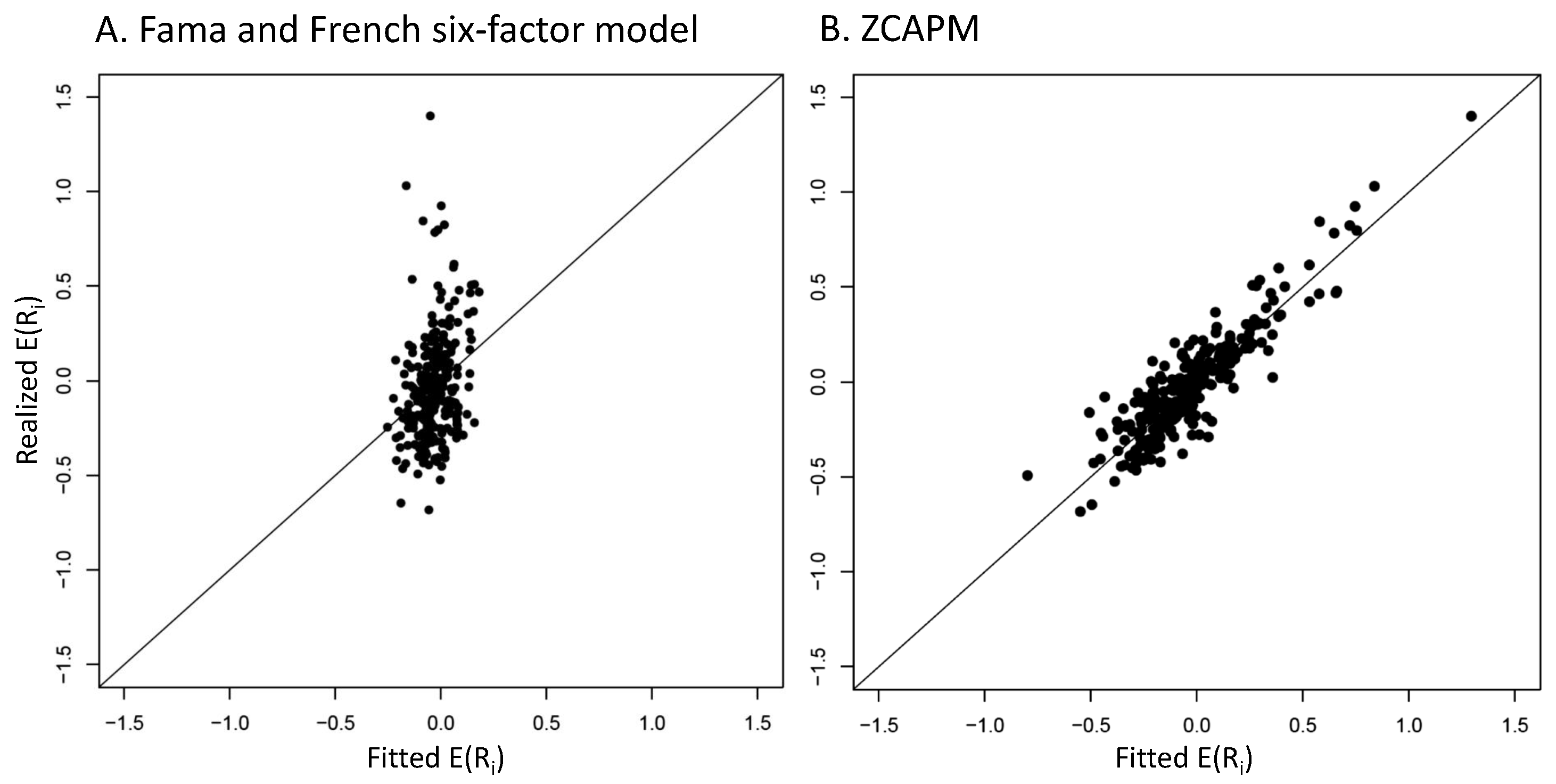

4.2. Graphical Mispricing Error Results

4.3. What Explains ZCAPM Outperformance?

"When Fama and French say that the line relating expected return and beta is flat,they are just saying that the expected excess return on the second factor is large.If we believe it’s as large as they say, we won’t fool around with their third and fourthfactors, for which they give no theory.18 We’ll go for the gold in the second factor!"

5. Conclusion

Appendix A. 133 Anomaly Portfolios from Chen and Zimmerman (2022)

| N | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | AbnormalAccruals ret | Abnormal accruals |

| 2 | Accruals ret | Accruals |

| 3 | AdExp ret | Advertisement expense |

| 4 | AM ret | Total assets to market |

| 5 | AnnouncementReturn ret | Earnings announcement return |

| 6 | AssetGrowth ret | Asset growth |

| 7 | Beta ret | CAPM beta |

| 8 | BetaFP ret | Frazzini-Pedersen beta |

| 9 | BetaTailRisk ret | Tail risk beta |

| 10 | BidAskSpread ret | Bid-ask spread |

| 11 | BM ret | Book to market using most recent ME |

| 12 | BMdec ret | Book to market using December ME |

| 13 | BookLeverage ret | Book leverage (annual) |

| 14 | BPEBM ret | Leverage component of BM |

| 15 | BrandInvest ret | Brand capital investment |

| 16 | Cash ret | Cash to assets |

| 17 | CashProd ret | Cash productivity |

| 18 | CBOperProf ret | Cash-based operating profitability |

| 19 | CF ret | Cash flow to market |

| 20 | Cfp ret | Operating cash flows to price |

| 21 | ChAssetTurnover ret | Change in asset turnover |

| 22 | ChEQ ret | Growth in book equity |

| 23 | ChInv ret | Inventory growth |

| 24 | ChInvIA ret | Change in capital investment (industry adjusted) |

| 25 | ChNNCOA ret | Change in net noncurrent operating assets |

| 26 | ChNWC ret | Change in net working capital |

| 27 | ChTax ret | Change in taxes |

| 28 | CompEquIss ret | Composite equity issuance |

| 29 | CompositeDebtIssuance ret | Composite debt issuance |

| 30 | Coskewness ret | Coskewness |

| 31 | DelCOA ret | Change in current operating assets |

| 32 | DelCOL ret | Change in current operating liabilities |

| 33 | DelEqu ret | Change in equity to assets |

| 34 | DelFINL ret | Change in financial liabilities |

| 35 | DelLTI ret | Change in long-term investment |

| 36 | DelNetFin ret | Change in net financial assets |

| 37 | DNoa ret | Change in net operating assets |

| 38 | DolVol ret | Past trading volume |

| 39 | EarningsConsistency ret | Earnings consistency |

| 40 | EarningsSurprise ret | Earnings surprise |

| 41 | EarnSupBig ret | Earnings surprise of big firms |

| 42 | EBM ret | Enterprise component of BM |

| 43 | EntMult ret | Enterprise multiple |

| 44 | EP ret | Earnings-to-Price ratio |

| 45 | EquityDuration ret | Equity duration |

| 46 | FirmAge ret | Firm age based on CRSP |

| 47 | Frontier ret | Efficient frontier index |

| 48 | GP ret | Gross profits/total assets |

| 49 | GrAdExp ret | Growth in advertising expenses |

| 50 | Grcapx ret | Change in capex (two years) |

| 51 | Grcapx3y ret | Change in capex (three years) |

| 52 | GrLTNOA ret | Growth in long term operating assets |

| 53 | GrSaleToGrInv ret | Sales growth over inventory growth |

| 54 | GrSaleToGrOverhead ret | Sales growth over overhead growth |

| 55 | Herf ret | Industry concentration (sales) |

| 56 | HerfAsset ret | Industry concentration (assets) |

| 57 | HerfBE ret | Industry concentration (equity) |

| 58 | High52 ret | 52 week high |

| 59 | Hire ret | Employment growth |

| 60 | IdioRisk ret | Idiosyncratic risk |

| 61 | IdioVol3F ret | Idiosyncratic risk (3 factor) |

| 62 | IdioVolAHT ret | Idiosyncratic risk (AHT) |

| 63 | Illiquidity ret | Amihud’s illiquidity |

| 64 | IndMom ret | Industry momentum |

| 65 | IndRetBig ret | Industry return of big firms |

| 66 | IntanBM ret | Intangible return using BM |

| 67 | IntanCFP ret | Intangible return using CFtoP |

| 68 | IntanEP ret | Intangible return using EP |

| 69 | IntanSP ret | Intangible return using Sale2P |

| 70 | IntMom ret | Intermediate momentum |

| 71 | Investment ret | Investment to revenue |

| 72 | InvestPPEInv ret | Change in PPE and inventory/assets |

| 73 | InvGrowth ret | Inventory growth |

| 74 | Leverage ret | Market leverage |

| 75 | LRreversal ret | Long-run reversal |

| 76 | MaxRet ret | Maximum return over month |

| 77 | MeanRankRevGrowth ret | Revenue growth rank |

| 78 | Mom6m ret | Momentum (6 month) |

| 79 | Mom12m ret | Momentum (12 month) |

| 80 | Mom12mOffSeason ret | Momentum without the seasonal part |

| 81 | MomOffSeason ret | Off season long-term reversal |

| 82 | MomOffSeason06YrPlus ret | Off season reversal years 6 to 10 |

| 83 | MomOffSeason11YrPlus ret | Off season reversal years 11 to 15 |

| 84 | MomOffSeason16YrPlus ret | Off season reversal years 16 to 20 |

| 85 | MomSeason ret | Return seasonality years 2 to 5 |

| 86 | MomSeason06YrPlus ret | Return seasonality years 6 to 10 |

| 87 | MomSeason11YrPlus ret | Return seasonality years 11 to 15 |

| 88 | MomSeason16YrPlus ret | Return seasonality years 16 to 20 |

| 89 | MomSeasonShort ret | Return seasonality last year |

| 90 | MRreversal ret | Medium-run reversal |

| 91 | NetDebtFinance ret | Net debt financing |

| 92 | NetDebtPrice ret | Net debt to price |

| 93 | NetEquityFinance ret | Net equity financing |

| 94 | NetPayoutYield ret | Net payout yield |

| 95 | NOA ret | Net operating asset |

| 96 | NumEarnIncrease ret | Earnings streak length |

| 97 | OperProf ret | Operating profits/book equity |

| 98 | OperProfRD ret | Operating profitability R&D adjusted |

| 99 | OPLeverage ret | Operating leverage |

| 100 | OrderBacklog ret | Order backlog |

| 101 | OrderBacklogChg ret | Change in order backlog |

| 102 | OrgCap ret | Organizational capital |

| 103 | PayoutYield ret | Payout yield |

| 104 | PctAcc ret | Percent operating accruals |

| 105 | Price ret | Price |

| 106 | PS ret | Piotroski F-score |

| 107 | RD ret | R&D over market cap |

| 108 | RDAbility ret | R&D ability |

| 109 | Realestate ret | Real estate holdings |

| 110 | ResidualMomentum ret | Momentum based on FF3 model residuals |

| 111 | ReturnSkew ret | Return skewness |

| 112 | ReturnSkew3F ret | Idiosyncratic skewness (3 factor model) |

| 113 | RevenueSurprise ret | Revenue surprise |

| 114 | Roaq ret | Return on assets (qtrly) |

| 115 | RoE ret | Net income/book equity |

| 116 | ShareIss1Y ret | Share issuance (1 year) |

| 117 | ShareIss5Y ret | Share issuance (5 year) |

| 118 | Size ret | Size |

| 119 | SP ret | Sales-to-price |

| 120 | Std turn ret | Share turnover volatility |

| 121 | STreversal ret | Short term reversal |

| 122 | Tang ret | Tangibility |

| 123 | Tax ret | Taxable income to income |

| 124 | TotalAccruals ret | Total accruals |

| 125 | TrendFactor ret | Trend in the general stock market |

| 126 | VarCF ret | Cash-flow to price variance |

| 127 | VolMkt ret | Volume to market equity |

| 128 | VolSD ret | Volume variance |

| 129 | VolumeTrend ret | Volume trend |

| 130 | XFIN ret | Net external financing |

| 131 | Zerotrade ret | Days with zero trades |

| 132 | ZerotradeAlt1 ret | Days with zero trades |

| 133 | ZerotradeAlt12 ret | Days with zero trades |

Appendix B. 153 Anomaly Portfolios from Jensen, Kelly, and Pedersen (2023)

| N | Anomaly abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | capex abn | Abnormal corporate investment |

| 2 | z score | Altman Z-score |

| 3 | ami 126d | Amihud measure |

| 4 | at gr1 | Asset growth |

| 5 | tangibility | Asset tangibility |

| 6 | sale bev | Assets turnover |

| 7 | at me | Assets-to-market |

| 8 | at be | Book leverage |

| 9 | bev mev | Book-to-market enterprise value |

| 10 | be me | Book-to-market equity |

| 11 | capx gr1 | CAPEX growth (1 year) |

| 12 | capx gr2 | CAPEX growth (2 years) |

| 13 | capx gr3 | CAPEX growth (3 years) |

| 14 | at turnover | Capital turnover |

| 15 | ocfq saleq std | Cash flow volatility |

| 16 | cop at | Cash-based operating profits-to-book assets |

| 17 | cop atl1 | Cash-based operating profits-to-lagged book assets |

| 18 | cash at | Cash-to-assets |

| 19 | dgp dsale | Change gross margin minus change sales |

| 20 | be gr1a | Change in common equity |

| 21 | coa gr1a | Change in current operating assets |

| 22 | col gr1a | Change in current operating liabilities |

| 23 | cowc gr1a | Change in current operating working capital |

| 24 | fnl gr1a | Change in financial liabilities |

| 25 | lti gr1a | Change in long-term investments |

| 26 | lnoa gr1a | Change in long-term net operating assets |

| 27 | nfna gr1a | Change in net financial assets |

| 28 | nncoa gr1a | Change in net noncurrent operating assets |

| 29 | noa gr1a | Change in net operating assets |

| 30 | ncoa gr1a | Change in noncurrent operating assets |

| 31 | ncol gr1a | Change in noncurrent operating liabilities |

| 32 | ocf at chg1 | Change in operating cash flow to assets |

| 33 | niq at chg1 | Change in quarterly return on assets |

| 34 | niq be chg1 | Change in quarterly return on equity |

| 35 | sti gr1a | Change in short-term investments |

| 36 | ppeinv gr1a | Change PPE and Inventory |

| 37 | dsale dinv | Change sales minus change Inventory |

| 38 | dsale drec | Change sales minus change receivables |

| 39 | dsale dsga | Change sales minus change SG&A |

| 40 | dolvol var 126d | Coefficient of variation for dollar trading volume |

| 41 | turnover var 126d | Coefficient of variation for share turnover |

| 42 | coskew 21d | Coskewness |

| 43 | prc highprc 252d | Current price to high price over last year |

| 44 | debt me | Debt-to-market |

| 45 | beta dimson 21d | Dimson beta |

| 46 | div12m me | Dividend yield |

| 47 | dolvol 126d | Dollar trading volume |

| 48 | betadown 252d | Downside beta |

| 49 | ni ar1 | Earnings persistence |

| 50 | earnings variability | Earnings variability |

| 51 | ni ivol | Earnings volatility |

| 52 | ni me | Earnings-to-price |

| 53 | ebitda mev | Ebitda-to-market enterprise value |

| 54 | eq dur | Equity duration |

| 55 | eqnpo 12m | Equity net payout |

| 56 | age | Firm age |

| 57 | betabab 1260d | Frazzini-Pedersen market beta |

| 58 | fcf me | Free cash flow-to-price |

| 59 | gp at | Gross profits-to-assets |

| 60 | gp atl1 | Gross profits-to-lagged assets |

| 61 | debt gr3 | Growth in book debt (3 years) |

| 62 | rmax5 21d | Highest 5 days of return |

| 63 | rmax5 rvol 21d | Highest 5 days of return scaled by volatility |

| 64 | emp gr1 | Hiring rate |

| 65 | iskew capm 21d | Idiosyncratic skewness from the CAPM |

| 66 | iskew ff3 21d | Idiosyncratic skewness from the Fama-French 3-factor model |

| 67 | iskew hxz4 21d | Idiosyncratic skewness from the q-factor model |

| 68 | ivol capm 21d | Idiosyncratic volatility from the CAPM (21 days) |

| 69 | ivol capm 252d | Idiosyncratic volatility from the CAPM (252 days) |

| 70 | ivol ff3 21d | Idiosyncratic volatility from the Fama-French 3-factor model |

| 71 | ivol hxz4 21d | Idiosyncratic volatility from the q-factor model |

| 72 | ival me | Intrinsic value-to-market |

| 73 | inv gr1a | Inventory change |

| 74 | inv gr1 | Inventory growth |

| 75 | kz index | Kaplan-Zingales index |

| 76 | sale emp gr1 | Labor force efficiency |

| 77 | aliq at | Liquidity of book assets |

| 78 | aliq mat | Liquidity of market assets |

| 79 | ret 60 12 | Long-term reversal |

| 80 | beta 60m | Market beta |

| 81 | corr 1260d | Market correlation |

| 82 | market equity | Market equity |

| 83 | rmax1 21d | Maximum daily return |

| 84 | mispricing mgmt | Mispricing factor: Management |

| 85 | mispricing perf | Mispricing factor: Performance |

| 86 | dbnetis at | Net debt issuance |

| 87 | netdebt me | Net debt-to-price |

| 88 | eqnetis at | Net equity issuance |

| 89 | noa at | Net operating assets |

| 90 | eqnpo me | Net payout yield |

| 91 | chcsho 12m | Net stock issues |

| 92 | netis at | Net total issuance |

| 93 | ni inc8q | Number of consecutive quarters with earnings increases |

| 94 | zero trades 21d | Number of zero trades with turnover as tiebreaker (1 month) |

| 95 | zero trades 252d | Number of zero trades with turnover as tiebreaker (12 months) |

| 96 | zero trades 126d | Number of zero trades with turnover as tiebreaker (6 months) |

| 97 | o score | Ohlson O-score |

| 98 | oaccruals at | Operating accruals |

| 99 | ocf at | Operating cash flow to assets |

| 100 | ocf me | Operating cash flow-to-market |

| 101 | opex at | Operating leverage |

| 102 | op at | Operating profits-to-book assets |

| 103 | ope be | Operating profits-to-book equity |

| 104 | op atl1 | Operating profits-to-lagged book assets |

| 105 | ope bel1 | Operating profits-to-lagged book equity |

| 106 | eqpo me | Payout yield |

| 107 | oaccruals ni | Percent operating accruals |

| 108 | taccruals ni | Percent total accruals |

| 109 | f score | Pitroski F-score |

| 110 | ret 12 1 | Price momentum t-12 to t-1 |

| 111 | ret 12 7 | Price momentum t-12 to t-7 |

| 112 | ret 3 1 | Price momentum t-3 to t-1 |

| 113 | ret 6 1 | Price momentum t-6 to t-1 |

| 114 | ret 9 1 | Price momentum t-9 to t-1 |

| 115 | prc | Price per share |

| 116 | ebit sale | Profit margin |

| 117 | qmj | Quality minus Junk: Composite |

| 118 | qmj growth | Quality minus Junk: Growth |

| 119 | qmj prof | Quality minus Junk: Profitability |

| 120 | qmj safety | Quality minus Junk: Safety |

| 121 | niq at | Change in quarterly return on assets |

| 122 | niq be | Quarterly return on equity |

| 123 | rd5 at | R&D capital-to-book assets |

| 124 | rd me | R&D-to-market |

| 125 | rd sale | R&D-to-sales |

| 126 | resff3 12 1 | Residual momentum t-12 to t-1 |

| 127 | resff3 6 1 | Residual momentum t-6 to t-1 |

| 128 | ni be | Return on equity |

| 129 | ebit bev | Return on net operating assets |

| 130 | rvol 21d | Return volatility |

| 131 | saleq gr1 | Sales growth (1 quarter) |

| 132 | sale gr1 | Sales growth (1 year) |

| 133 | sale gr3 | Sales growth (3 years) |

| 134 | sale me | Sales-to-market |

| 135 | turnover 126d | Share turnover |

| 136 | ret 1 0 | Short-term reversal |

| 137 | niq su | Standardized earnings surprise |

| 138 | saleq su | Standardized Revenue surprise |

| 139 | tax gr1a | Tax expense surprise |

| 140 | pi nix | Taxable income-to-book income |

| 141 | bidaskhl 21d | The high-low bid-ask spread |

| 142 | taccruals at | Total accruals |

| 143 | rskew 21d | Total skewness |

| 144 | seas 1 1an | Year 1-lagged return, annual |

| 145 | seas 1 1na | Year 1-lagged return, nonannual |

| 146 | seas 2 5an | Years 2-5 lagged returns, annual |

| 147 | seas 2 5na | Years 2-5 lagged returns, nonannual |

| 148 | seas 6 10an | Years 6-10 lagged returns, annual |

| 149 | seas 6 10na | Years 6-10 lagged returns, nonannual |

| 150 | seas 11 15an | Years 11-15 lagged returns, annual |

| 151 | seas 11 15na | Years 11-15 lagged returns, nonannual |

| 152 | seas 16 20an | Years 16-20 lagged returns, annual |

| 153 | seas 16 20na | Years 16-20 lagged returns, nonannual |

References

- Ang, A., R. J. Hodrick, Y. Xing, and X. Zhang, 2006, The cross-section of volatility and expected returns, Journal of Finance 61, 259–299. [CrossRef]

- Angelidis, T., A. Sakkas, and N. Tessaromatis, 2015, Stock market dispersion, the business cycle and expected factor returns, Journal of Banking and Finance 59, 256–279. [CrossRef]

- Asquith, D., J. Jones, and R. Kieschnick, 1998, Evidence on price stabilization and underpricing in early IPO returns, Journal of Finance 53, 1759–1773. [CrossRef]

- Back, K., N. Kapadia, and B. Ostdiek, 2013, Slopes as factors: Characteristic pure plays, Working paper, Rice University.

- Back, K., N. Kapadia, and B. Ostdiek, 2015, Testing factor models on characteristic and covariance pure plays, Working paper, Rice University.

- Bansal, R., and A. Yaron, 2004, Risks for the long run: A potential resolution of asset pricing puzzles, Journal of Finance 59, 1481–1509. [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N., Shleifer, A., Vishny, R., 1998, A model of investor sentiment, Journal of Financial Economics 49, 307–343.

- Bartram, S. M., and M. Grinblatt, 2018, Agnostic fundamental analysis works, Journal of Financial Economics 128, 125–147. [CrossRef]

- Bekaert, G., E. Engstrom, and A. Ermolov, 2023, The variance risk premium in equilibrium models, Review of Finance, 1977–2014. [CrossRef]

- Bekaert, G., and C. Harvey, 1997, Emerging equity market volatility, Journal of Financial Economics 43, 29–77. [CrossRef]

- Black, F., 1972, Capital market equilibrium with restricted borrowing, Journal of Business 45, 444–454. [CrossRef]

- Black, F., 1995, Estimating expected return, Financial Analysts Journal 49, 36–38.

- Bo, C. B., and S. Batzoglou, 2008, What is the expectation maximization algorithm?, Nature Biotechnology 26, 897–899.

- Bowles, B., A. V. Reed, M. C. Ringgenberg, and J. R. Thornock, 2023, Anomaly time, Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

- Carhart, M. M., 1997, On persistence in mutual fund performance, Journal of Finance 52, 57–82.

- Chen, N.-F., 1983, Empirical tests of the theory of arbitrage pricing, Journal of Finance 38, 1393–1414.

- Chen, Y., M. Cliff, and H. Zhao, 2017, Hedge funds: The good, the bad, and the lucky, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 52, 1081–1109.

- Chen, A. Y., and M. Velikov, 2023, Zeroing in on the expected returns of anomalies, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 58, 968–1004.

- Chen, A. Y., and T. Zimmermann, 2020, Publication bias and the cross-section of stock returns, Review of Asset Pricing Studies 10, 249–289. [CrossRef]

- Chen, A. Y., and T. Zimmerman, 2022, Open source cross-sectional asset pricing Critical Finance Review 11, 207–264.

- Chordia, T., A. Goyal, and A. Saretto, 2020, Anomalies and false rejections, Review of Financial Studies 33, 2134–2179. [CrossRef]

- Chordia, T., A. Subrahmanyam, and Q. Tong, 2014, Have capital market anomalies attenuated in the recent era of high liquidity and trading activity?, Journal of Accounting and Economics 58, 41-–58. [CrossRef]

- Christie, W., and R. Huang, 1994, The changing functional relation between stock returns and dividend yields, Journal of Empirical Finance 1, 161–191. [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, J. H., 1996, A cross-sectional test of an investment-based asset pricing model, Journal of Political Economy 104, 572–621. [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, J. H., 2011, Presidential address: Discount rates, Journal of Finance 56, 1047–1108. [CrossRef]

- Connolly, R., and C. Stivers, 2003, Momentum and reversals in equity index returns during periods of abnormal turnover and return dispersion, Journal of Finance 58, 1521–1556. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M., H. Gulen, and M. Ion, 2024, The use of asset growth in empirical asset pricing models, Journal of Financial Economics 151, 103746. [CrossRef]

- Copeland, T. E., and J. F. Weston, 1980, Financial Theory and Corporate Policy (Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, MA).

- Daniel, K., D. Hirshleifer, and A. Subrahmanyam, 1997, A theory of overconfidence, self-attribution, and security market under- and over-reactions. Unpublished working paper. University of Michigan.

- DeBondt, W. F. M., and R. H. Thaler, 1987, Further evidence on investor overreaction and stock market seasonality, Journal of Finance 42, 557–581.

- Demirer, R. and S. P. Jategaonkar, 2013, The conditional relation between dispersion and return, Review of Financial Economics 22, 125–134. [CrossRef]

- Dempster, A.P., N. M. Laird, and D. B. Rubin 1977, Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 39, 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Detzel, A., J. Duarte, A. Kamara, and S. Siegel, 2024, The cross-section of volatility and expected returns, Critical Finance Review, forthcoming. [CrossRef]

- Engelberg, J., R. D. McLean,and J. Pontiff, 2018. Anomalies and news, Journal of Finance 73, 1972–2001.

- Fama, E. F., 1970, Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work, Journal of Finance 25, 383–417. [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., 2013, Two Pillars of Asset Pricing, Nobel Prize Lecture. [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., and K. R. French, 1992, The cross-section of expected stock returns, Journal of Finance 47, 427–465. [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., and K. R. French, 1993, Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds, Journal of Financial Economics 33, 3–56. [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., and K. R. French, 1996a, Multifactor explanations of asset pricing anomalies, Journal of Finance 51, 55–84.

- Fama, E. F., and K. R. French, 1996b, The CAPM is wanted, dead or alive, Journal of Finance 51, 1947–1958.

- Fama, E. F., and K. R. French, 1998, Market efficiency, long-term returns, and behavioral finance, Journal of Financial Economics 49, 283–306.

- Fama, E. F., and K. R. French, 2008, Dissecting anomalies, Journal of Finance 63, 1653–1678.

- Fama, E. F., and K. R. French, 2015, A five-factor asset pricing model, Journal of Financial Economics 116, 1–22.

- Fama, E. F., and K. R. French, 2018, Choosing factors, Journal of Financial Economics 128, 234–252.

- Fama, E. F., and J. D. MacBeth, 1973, Risk, return, and equilibrium: Empirical tests, Journal of Political Economy 81, 607–636.

- Ferson, W. E., 2019, Empirical Asset Pricing: Models and Methods (The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA).

- Ferson, W. E., S. K. Nallareddy, and B. Xie, 2013, The "out-of-sample" performance of long-run risk models, Journal of Financial Economics 107, 537–556.

- Garcia, R., D. Mantilla-Garcia, and L. Martellini, 2014, A model-free measure of aggregate idiosyncractic volatility and the prediction of market returns, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 49, 1133–1165. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, M. R., S. A. Ross, and J. Shanken, 1989, A test of the efficiency of a given portfolio, Econometrica 57, 1121–1152. [CrossRef]

- Giglio, S., and D. Xiu, 2021, Asset pricing with omitted factors, Journal of Political Economy 129, 1947–1990. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J., L. Kogan, and L. Zhang, 2003, Equilibrium cross section of returns, Journal of Political Economy 111, 693–732. [CrossRef]

- Green, J., J. R. Hand, and X. F. Zhang, 2013, The supraview of return predictive signals, Review of Accounting Studies 18, 692–730. [CrossRef]

- Green, J., J. R. Hand, and F. Zhang, 2017, The characteristics that provide independent information about average US monthly stock returns, Review of Financial Studies 30, 4389–4436. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C. R., and Y. Liu, 2016, Rethinking performance evaluation, Working paper no. 22134, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. 2 2134, Cambridge, MA.

- Harvey, C. R., Y. Liu, and H. Zhu, 2016, ... and the cross-section of expected returns, Review of Financial Studies 29, 5–68.

- Hou, K., C. Xue, and L. Zhang, 2015, Digesting anomalies: An investment approach, Review of Financial Studies 28, 650–705. [CrossRef]

- Hou, K., C. Xue, and L. Zhang, 2020, Replicating anomalies, Review of Financial Studies 33, 2019–2133.

- Jacobs, H., and S. Müller, 2020, Anomalies cross the globe: Once public, no longer existent?, Journal of Financial Economics 135, 213-230.

- Jagannathan, R., and Z. Wang, 1996, The conditional CAPM and the cross-section of asset returns, Journal of Finance 51, 3–53. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T. I., B. Kelly, and L. H. Pedersen, 2023, Is there a replication crisis in finance?, Journal of Finance 78, 2465–2518. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., 2010, Return dispersion and expected returns, Financial Markets and Portfolio Management 24, 107–135.

- Jones, P. N., and G. J. McLachlan, 1990, Algorithm AS 254: Maximum likelihood estimation from grouped and truncated data with finite normal mixture models, Applied Statistics 39, 273–282. [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky, 1979. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk, Econometrica 47, 263–291. [CrossRef]

- Kolari, J. W., J. Z. Huang, H. A. Butt, and H. Liao, 2022, International tests of the ZCAPM asset pricing model, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions &Money 79, 101607. [CrossRef]

- Kolari, J. W., J. Z. Huang, W. Liu, and H. Liao, 2022, Further tests of the ZCAPM asset pricing model, Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15, 1-23. Reprinted in Kolari, J. W., and S. Pynnonen, 2022, eds., Frontiers of Asset Pricing (MDPI, Basel, Switzerland). [CrossRef]

- Kolari, J. W., J. Z. Huang, W. Liu, and H. Liao, 2023, The alpha force: Testing missing asset pricing factors, Presented at the annual meetings of the Western Economic Association International, San Diego, CA.

- Kolari, J. W., J. Z. Huang, W. Liu, and H. Liao, 2023, A cross-sectional asset pricing test of model validity, Presented as the annual meetings of the Southwestern Finance Association, Las Vegas, NV. Available on SSRN at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4203990.

- Kolari, J. W., J. Z. Huang, W. Liu, and H. Liao, 2025, A quantum leap in asset pricing: Explaining anomalyous returns, Presented at the annual meetings of the Southwestern Finance Association, Las Vegas, NV. Available on SSRN at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4203990. Awarded the Best Paper in Investments.

- Kolari, J. W., W. Liu, and J. Z. Huang, 2021, A New Model of Capital Asset Prices: Theory and Evidence (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, Switzerland).

- Kolari, J. W., W. Liu, and S. Pynnonen, 2024, Professional Investment Portfolio Management: Boosting Performance with Machine-Made Portfolios and Stock Market Evidence (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, Switzerland).

- Kolari, J. W., and S. Pynnonen, 2023, Investment Valuation and Asset Pricing: Models and Methods (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, Switzerland).

- Lakonishok, J., A. Shleifer, and R. W. Vishny, 1994, Contrarian investment, extrapolation, and risk, Journal of Finance 49, 1541–1578.

- Lettau, M., and S. Ludvigson, 2001, Consumption, aggregate wealth, and expected stock returns, Journal of Finance 56, 815–849.

- Lettau, M., and M. Pelger, 2020, Factors that fit the time series and cross-section of stock returns, Review of Financial Studies 33, 2274–2325. [CrossRef]

- Linnainmaa, J., and M. Roberts, 2018, The history of the cross-section of stock returns, Review of Financial Studies 31, 2606–2649. [CrossRef]

- Lintner, J., 1965, The valuation of risk assets and the selection of risky investments in stock portfolios and capital budgets, Review of Economics and Statistics 47, 13–37. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., 2013, A New Asset Pricing Model Based on the Zero-Beta CAPM: Theory and Evidence, Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University.

- Liu, W., J. W. Kolari, and J. Z. Huang, 2012, A new asset pricing model based on the zero-beta CAPM, Best paper award in investments at the 2012 annual meetings of the Financial Management Association, Atlanta, GA (October).

- Liu, W., J. W. Kolari, and J. Z. Huang, 2019, Creating superior investment portfolios, Working paper, Texas A&M University.

- Liu, W., J. W. Kolari, and J. Z. Huang, 2020, Return dispersion and the cross-section of stock returns, Presented at the annual meetings of the Southern Finance Association, Palm Springs, CA. [CrossRef]

- Loungani, P., M. Rush, and W. Tave, 1990, Stock market dispersion and unemployment, Journal of Monetary Economics 25, 367–388.

- Lu, X., R. F. Stambaugh, Y. Yuan, Y., 2018, Anomalies abroad: Beyond data mining, Working paper, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China.

- Markowitz, H. M., 1952, Portfolio selection, Journal of Finance 7, 77–91.

- Markowitz, H. M., 1959, Portfolio Selection: Efficient Diversification of Investments (John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY).

- McLachlan, G. J., and T. Krishnan, 2008, The EM Algorithm and Extensions, Second edition (John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY).

- McLachlan, G., and D. Peel, 2000, Finite Mixture Models (Wiley Interscience, New York, NY).

- McLean, R. D., and J. Pontiff, 2016, Does academic publication destroy predictability?, Journal of Finance 71, 5–32.

- Mossin, J., 1966, Equilibrium in a capital asset market, Econometrica 34, 768–783. [CrossRef]

- Novy-Marx, R., and M. Velikov, 2016, A taxonomy of anomalies and their trading costs, Review of Financial Studies 29, 104–147,.

- Pastor, L., and P. Veronesi, 2009, Technological revolutions and stock prices, American Economic Review 99, 1451–1483. [CrossRef]

- Schwert, G. W., 2003, Anomalies and market efficiency, in G. M. Constantinides, M. Harris, and R. Stulz, eds., Handbook of the Economics of Finance (North-Holland, Amsterdam, NL), 939–974.

- Sharpe, W. F., 1964, Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk, Journal of Finance 19, 425–442. [CrossRef]

- Shiller, R. J., 1981, Do stock prices move too much to be justified by subsequent changes in dividends, American Economic Review 71, 421–436.

- Stambaugh, R. F., and Y. Yuan, 2017, Mispricing factors, Review of Financial Studies 30, 1270–1315.

- Stivers, C., 2003, Firm-level return dispersion and the future volatility of aggregate stock market returns, Journal of Financial Markets 6, 389–411. [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. H., 1999, The end of behavioral finance, Financial Analysts Journal 55, 12–17. [CrossRef]

- Treynor, J. L., 1961, Market value, time, and risk, Unpublished manuscript.

- Treynor, J. L., 1962, Toward a theory of market value of risky assets, Unpublished manuscript.

- Zhang, L., 2005, The value premium, Journal of Finance 60, 67–103.

| 1 | See, for example, Fama (1998), Green, Hand, and Zhang (2013, 2017), Chordia, Subrahmanyam, and Tong (2014), Novy-Marx and Velikov (2016), Linnainmaa and Roberts (2018), Jacobs and Müller (2020), Chen and Zimmerman (2022), and others. |

| 2 | See Bartram and Grinblatt (2018), Engelberg, McLean, and Pontiff (2018), Lu, Stambaugh, and Yuan (2018), Wahal (2019), Jacobs and Müller (2020), and others. |

| 3 | Fama and French (2015, 2018) included somewhat similar profit and investment factors to augment their three-factor model. |

| 4 | A total of 161 out of 319 anomalies were classified as clear predictors by the authors. |

| 5 | See Kahneman and Tversky (1979), Shiller (1981), DeBondt and Thaler (1985, 1995), Daniel, Hirshleifer, Subrahmanyam (1997), Barberis, Shleifer, and Vishny (1998), Thaler (1999) and others. |

| 6 | This dataset was assembled from a number of previous anomaly studies. For further details, see Chen and Velikov (2021). |

| 7 | In unreported results, we tested the Hou, Xue, and Zhang as well as Stambaugh and Yuan four-factor models. Our results were unchanged for the most part with poor performance from these models (similar to those of the Carhart four-factor model) but strong explanatory power for the ZCAPM. Results are available from the authors upon request. |

| 8 | For discussion of estimated market prices of risk, see Ferson, Sarkissian, and Simon (1999), Cochrane (2005), Back, Kapadia, Ostdiek (2013, 2015), Ferson (2019), and other. |

| 9 | For further discussion of the ZCAPM, see conference presentations and publications by the authors, including Liu, Kolari and Huang (2012), Liu (2013), Liu, Kolari, and Huang (2019), Liu, Kolari, and Huang (2020), Kolari, Huang, Butt, and Liao (2022), Kolari, Huang, Liu, and Liao (2022, 2023, 2025), Kolari and Pynnonen (2023), and Kolari, Liu, and Pynnonen (2024). |

| 10 | Previous studies have incorporated time-series market volatility (e.g., VIX index) in asset pricing models, including Ang, Hodrick, Xing, and Zhang (2006), Bekaert, Engstrom, and Ermolov (2023), Detzel, Duarte, Kamara, and Siegel (2024), and citations therein. |

| 11 | For example, see work by Loungani, Rush, and Tave (1990), Christie and Huang (1994), Bekaert and Harvey (1997, 2000), Connolly and Stivers (2003), Gomes, Kogan, and Zhang (2003), Stivers (2003), Bansal and Yaron (2004), Zhang (2005), Pastor and Veronesi (2009), Bansal, Kiku, Shaliastovich, and Yaron (2014), Angelidis, Sakkas, and Tessaromatis (2015), among others. Garcia, Mantilla-Garcia, and Martellini (2014) have conjectured that cross-sectional return dispersion in the stock market is related to aggregate idiosyncratic risk. Also, Cooper, Gulen, and Ion (2024) have shown that macroeconomic shocks associated with market return dispersion are related to the asset growth factor in the Hou, Xue, and Zhang and Fama and French five-factor models. |

| 12 | They more precisely specified instead of simply in these equations, where is a complex function of other terms. |

| 13 |

See Kolari et al. (2021, p. 71) for the mathematical derivation. Like Black (1972, pp. 452-454), the ZCAPM is extended to the existence of a riskless asset. Investors can purchase the riskless asset but cannot short (borrow) this asset. Investors are allowed to take short positions in risky assets (e.g., the zero-beta portfolio). We can derive Black’s zero-beta CAPM with a riskless asset as follows:

After rearranging terms, the zero-beta CAPM becomes:

|

| 14 | Precedent exists in the asset pricing literature for the introduction of hidden or latent variables. For example, principal component analysis (PCA) and factor analysis use statistical methods to identify hidden factors in asset pricing models. See, Roll and Ross (1980), Chen (1983), Lettau and Pelger (2020), and many others. |

| 15 | See Dempster, Laird, and Rubin (1977), Jones and McLachlan (1990), McLachlan and Peel (2000), McLachlan and Krishnan (2008), and others. Some finance studies have applied EM regression, including Asquith, Jones, and Kieschnick (1998), McLachlan and Krishnan (2008), Harvey and Liu (2016), Chen, Cliff, and Zhao (2017), among others. See Bo and Batzoglou (2008) for a primer on the EM algorithm with application to computational biology. Also, Wikipedia provides discussion of the EM algorithm and literature citations. |

| 16 | More specifically, the E-step provides a conditional expectation of the log-likehood function using current estimates of parameter values, and the M-step iteratively maximizes the log-likelihood in the E-step. The EM algorithm converges to a stationary point of the likelihood equation. |

| 17 | Taking into account this time-varying factor return behavior, Ang, Madhaven, and Sobczyk (2017) have proposed a method to allow for dynamic factor loadings with some success in U.S. mutual fund portfolios. It is possible that multifactor models based on long/short factors could benefit from time-variable factors and their loadings. However, this research is beyong the scope of the present study. |

| 18 | Black was referring here to the small-firm factor and price-to-book factor, respectively. |

| Statistic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.86 |

| Standard deviation | 1.07 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.66 |

| Maximum | 11.35 | 6.17 | 6.74 | 7.12 | 4.52 | 2.53 | 10.77 |

| Minimum | -17.47 | -11.19 | -5.00 | -14.37 | -3.01 | -5.87 | 0.68 |

| P25 | -0.46 | -0.30 | -0.24 | -0.25 | -0.17 | -0.18 | 1.47 |

| P50 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.73 |

| P75 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 2.04 |

| Model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPM | 0.44 | -0.00 | 0.01 | ||||||

| (17.77***) | (-0.01) | ||||||||

| FF3 | 0.42 | 0.07 | -0.09 | 0.27 | 0.11 | ||||

| (19.37***) | (0.39) | (-0.37) | (1.82*) | ||||||

| C4 | 0.40 | -0.04 | -0.13 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.17 | |||

| (18.52***) | (-0.23) | (-0.61) | (1.84*) | (1.29) | |||||

| FF5 | 0.40 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.15 | ||

| (20.33***) | (0.70) | (0.17) | (0.77) | (1.25) | (2.76***) | ||||

| FF6 | 0.38 | -0.04 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.19 | |

| (19.00***) | (-0.26) | (0.16) | (1.19) | (1.64) | (1.54) | (2.31**) | |||

| ZCAPM | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.72 | 0.84 | |||||

| (9.96) | (1.43) | (6.69***) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).