Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the prominent discourses on low fertility, parenting, child care, and family life in contemporary Korean society?

- RQ2: How have socioeconomic and gender inequities shaped Korea’s parental ethnotheories on child development, parenting, and family life?

- RQ3: What early childhood and family support policy implications can be drawn from understanding these discourses?

2. Methods

3. Results: Discourses on Parenting, Child Care, and Family Life

3.1. Rising Socioeconomic Inequities and the Culture of Excessive Comparison and Hyper-Competitiveness

3.1.1. ‘High Pressure Expenses” to Equalize Unequal Chances

3.1.2. Private Education Expenditure Propelled by ‘Education Fever’

3.1.3. Scarcity of Affordable Housing

3.2. Childrearing as Luxury: Gender Inequities and Affordability of Parenting

3.3. Parenting as Return on Investment & Paradigm Shift on Happiness among the N-po Generation

4. Discussion & Implications

4.1. Affordable Housing Policies

4.2. Child Care and Early Childhood Education Policies

4.3. Family Support Policies and Family-Friendly Workplace

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

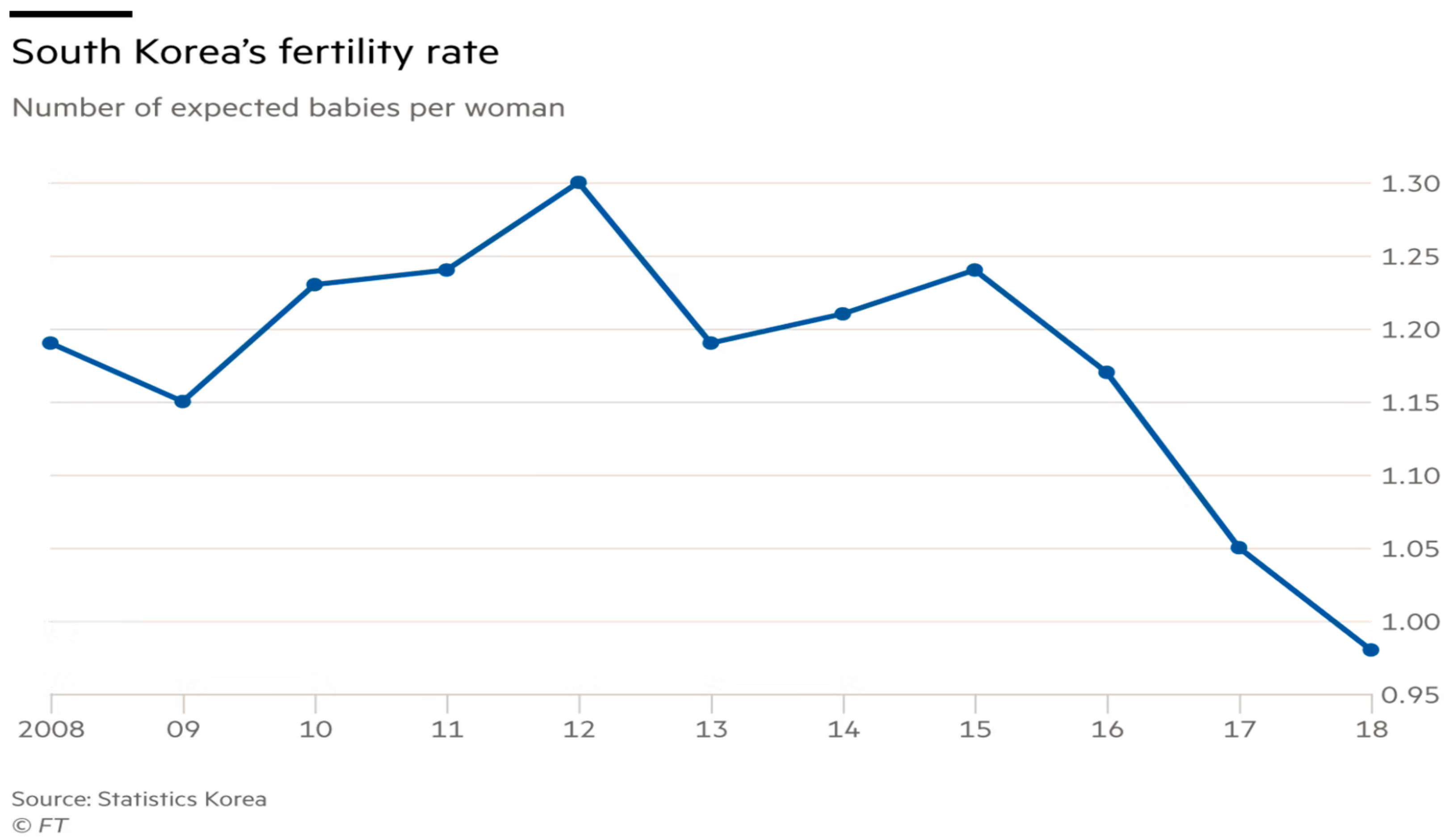

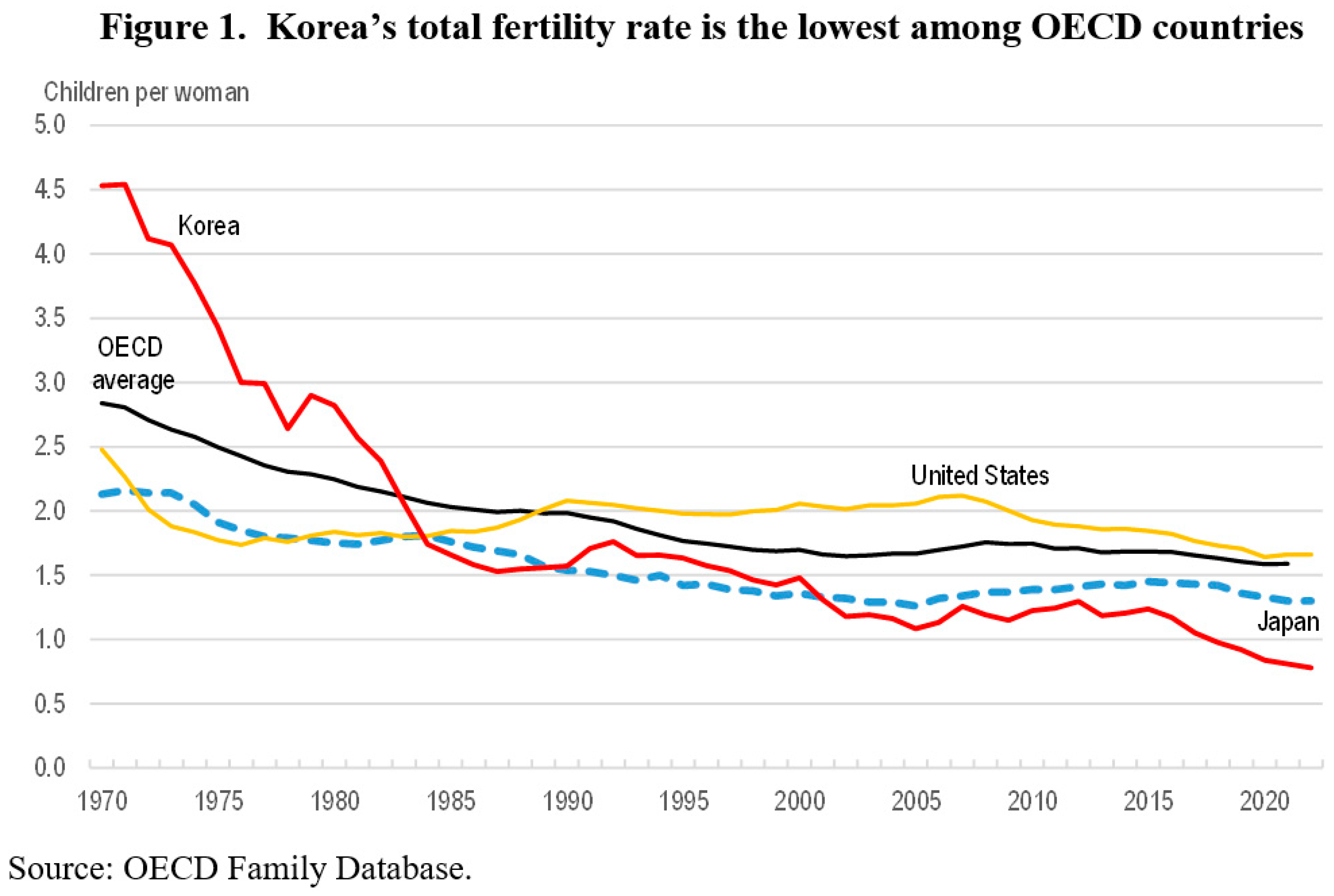

- Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS) (2025). Total fertility rate. Available online: https://kosis.kr/eng/.

- Ahn, A. (2023, March 19). South Korea has the world’s lowest fertility rate, a struggle with lessons for us all. NPR. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2023/03/19/1163341684/south-korea-fertility-rate.

- OECD (2024, June 20). Society at a Glance 2024 - Country Notes: Korea. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2024/06/society-at-a-glance-2024-country-notes_d98f4d80/korea_5c43a214.html.

- I’m, S. B.; Lee, J. (2021, August 22). As population dwindles, most cities could disappear. Korea JoongAng Daily. Available online: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2021/08/22/national/socialAffairs/aging-society-low-birthrate-population/20210822171700338.html.

- Coleman, D.A. (2002). Replacement migration, or why everyone is going to have to live in Korea: A fable for our times from the United Nations. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 357(1420), 583–598. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M. (2018a). Gender analysis on the Plan for Ageing Society and Population - For reconstruction of the discourses on low fertility. Journal of Critical Social Welfare, 59, 103-152. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, C. (2024, February 28). In South Korea, the world's lowest fertility rate plunges again in 2023. Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/south-koreas-fertility-rate-dropped-fresh-record-low-2023-2024-02-28/.

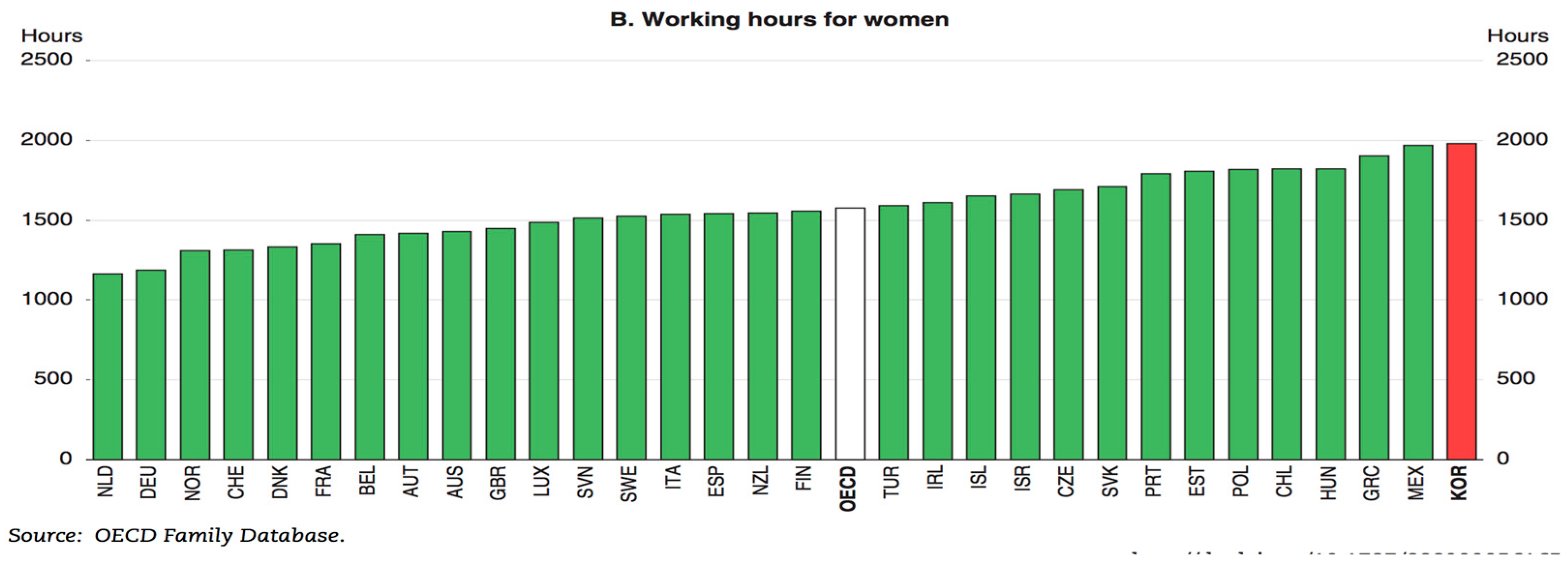

- Jones, R.S. (2023, June 22). Korean policies to reverse the decline in the fertility rate part 1: Balancing work and family. The Korea Economic Institute. Available online: https://keia.org/the-peninsula/korean-policies-to-reverse-the-decline-in-the-fertility-rate-part-1-balancing-work-and-family/.

- Reed, B. (2024, February 28). South Korea’s fertility rate sinks to record low despite $270bn in incentives. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/28/south-korea-fertility-rate-2023-fall-record-low-incentives.

- OECD KOREA Policy Centre. (2023). Family database in the Asia-Pacific Region. SF2.3: Age of mothers at childbirth and age-specific fertility. Available online: https://oecdkorea.org/resource/download/2023/SF_2_3_Age_mothers_childbirth_2023.pdf.

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. (2024, November 4). Seoul expands support for infertility treatments: 1 in 5 births in Seoul results from infertility procedures. Available online: https://english.seoul.kr/seoul-expands-infertility-procedure/.

- Korean Broadcasting System (KBS). (2023). 가정의 달 특집 2030 저출산을 말하다–청출어람단. Available online: https://www.ondemandkorea.com/player/vod/gen-z-and-millennials-views-on-low-birth-rate-1.

- Korean Broadcasting System (KBS). (2024). 가정의 달 특별기획 5 부작. 저 너머의 출산. Available online: https://tv.nate.com/program/clips/29775.

- Williams, J. (2024, June 20). A conversation with Joan Williams: Korea is so screwed, Wow! Anniversary special. Education Broadcasting System (EBS). Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HqqthZDCvfQ.

- Sussman, A.L. (2023, March 21). The real reason South Koreans aren’t having babies. The Atlantic. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/03/south-korea-fertility-rate-misogyny-feminism/673435/?utm_source=copy-link&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=share.

- Educational Broadcasting System (EBS). (2023d). 초대석 - 모든 아이는 국가가 키운다. [The nation raises all children: Interview with Youngmi Kim, Former Vice Chairman of the Presidential Committee on an Aging Society and Population Policy]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DGk0YO75-zw.

- Mackenzie, J. (2024, February 27). Why South Korean women aren’t having babies. BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-68402139.

- Education Broadcasting System. (EBS). (2023c). 초저출생, 국민의 의견을 듣는다. [Listening to the popular opinions on low birth rates]. Available online: https://www.ondemandkorea.com/player/vod/birth-rate-opinion?contentId=1589332.

- Roh, B.R.; Yang, K.E. (2019). Text mining analysis of South Korea’s birth-rate decline issue in newspaper articles: Transition patterns over 18 years. Korean Journal of Social Welfare, 71(4), 153-175. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE09273613.

- Harkness, S.; Super, C.M. (2021). Why understanding culture is essential for supporting children and families. Applied Developmental Science, 25(1), 14-25. [CrossRef]

- Seoul Family Center (2024). Seoul Family Report. ISSN 3022-4195. Seoul Metropolitan Government. Available online: https://familyseoul.or.kr/file/46237.

- Mullet, D.R. (2018). A general critical discourse analysis framework for educational research. Journal of Advanced Academics, 29(2), 116-142. [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, T.A. (1993). Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 249-283. [CrossRef]

- Wodak, R.; Meyer, M. (2009). Methods for critical discourse analysis. London, England: Sage.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. New York: Pantheon.

- Brookfield, S.D. (2005). The power of critical theory: Liberating adult learning and teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Byun, S.; Kim, K. (2010). Educational inequality in South Korea: The widening socioeconomic gap in student achievement. Research in the Sociology of Education, 17, 155-182. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. (2024). Voices of youth and listening to the Minister of Health and Welfare: Solutions for low fertility and population aging. 청출 어람단. 복지부 차관에게 듣는다: 저출산 고령화 해법. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL3fOWhRbsK9MK13-I1JA_C7YBpea0dRvv.

- Sorensen, C.W. (1994). Success and education in South Korea. Comparative Education Review, 38(1), 10-35. [CrossRef]

- Hankyoreh. (2024, October 8). 88% of Koreans think their society isn’t fit for raising children, poll finds. Available online: https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/1161590.html.

- Kim, S.; Tertilt, M.; Yum, M. (2024). Status externalities in education and low birth rates in Korea. American Economic Review, 114(6), 1576-1611. [CrossRef]

- Seth, M.J. (2002). Education fever: Society, politics, and the pursuit of schooling in South Korea. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

- OECD Better Life Index (2024). Life Satisfaction. Available online: https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/life-satisfaction/.

- Korean Broadcasting System (KBS World). (2025b, February 24). South Koreans report lower life satisfaction for the first time in 4 years. Available online: http://world.kbs.co.kr/service/news_view.htm?lang=e&Seq_Code=191191.

- Bank of Korea. (2023). Regional Population Migration and the Regional Economy Report. Available online: https://www.bok.or.kr/portal/bbs/P0002507/view.do?nttId=10081308&menuNo=200069.

- Yoo, J.S. (2022). Fertility rate analysis by income class and policy implications. Korean Journal of Social Science, 41(3), 233-258. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y. (2025, March 13). Private education spending hits record despite fall in student numbers. The Korea Herald. Available online: https://www.koreaherald.com/article/10440947.

- Korean Broadcasting System (KBS). (2025a, February 14). 추적 60 분: 7 세 고시, 누구를 위한 시험인가 [Pursuit of 60 minutes: Entrance exams for 7 year olds: For whom do the exams exist?] [Documentary]. Episode 1400. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DysyxTqFlnY.

- Hot Issue Ji (2025, February 5). Human documentary: In the name of a mother: Episode 1 [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1XpyBBHTRhk.

- Hot Issue Ji (2025, February 25). Human documentary: In the name of a mother: Episode 2 [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wXXKyGA-LXc.

- Kim, C. (Executive Producer). (2025). 라이딩 인생 [Riding life] [TV drama series]. KT Studio Genie.

- Jin, T.H. (2025, April 11). EBS News exclusive special report: Nation’s first evaluation study of ‘English kindergartens’: Severe side effects on children’s anxiety and parent-child conflict. Available online: https://v.daum.net/v/20250411142647424.

- Education Broadcasting System (EBS). (2023a). 30 분 리얼토크 - 초 저출생 0.78 3 부작. [A 30-minute real talk: Ultra-low fertility rate of 0.78] [A documentary series. Part I-III]. Available online: https://www.ondemandkorea.com/player/vod/birth-rate-078.

- Kim, C. (Executive Producer). (2025). 라이딩 인생. [Riding life] [TV drama series]. KT Studio Genie.

- Kim, S.H. (Executive Producer). (2024a)요즘 육아 금쪽같은 내새끼. [My Golden Kids]. [Reality TV Series]. Episode 188. Channel A. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt30797088/.

- Kim, S.H. (Executive Producer). (2024b)요즘 육아 금쪽같은 내새끼. [My Golden Kids]. [Reality TV Series]. Episode 215. Channel A. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt30797088/.

- Yang, H.S. (2023). 일타 스캔들. [Crash Course in Romance]. [Korean Drama TV Series]. Netflix. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt24578016/.

- Ra, H.N. (2022). 그린마더스클럽. [Green Mothers’ Club]. [Korean Drama TV Series]. Netflix. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt15060900/?ref_=fn_all_ttl_1.

- Joo. D.M. (2020). 펜트하우스. [The Penthouse: War in Life]. Seasons 1-3. [Korean Drama TV Series]. Netflix. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt13067118/?ref_=fn_all_ttl_1.

- Kim, J.Y. (2018b). SKY 캐슬. [SKY Castle]. [Korean Drama TV Series]. JTBC. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt9151274/.

- Chae, H.S. (2025, February 5). The curse of spending 27 trillion won on cram schools: With a 1% increase in private supplemental education, total fertility rate drops by 0.3%. JoongAng Daily. Available online: https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/25312022.

- Hankyoreh. (2023, November 3). Korea has the highest capital population concentration of OECD–BOK says it’s hurting birth rates. Available online: https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/1114875.html.

- Educational Broadcasting System (EBS). (2023b). 저출생 인구위기 극복의날: 0.78 이후의 세계. 7 부작. [A 7-part documentary series, Population planning in the age of ultra-low birth]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLpuzWnAKjQgC0Xtkq0V-sm6sKd_s74iFS.

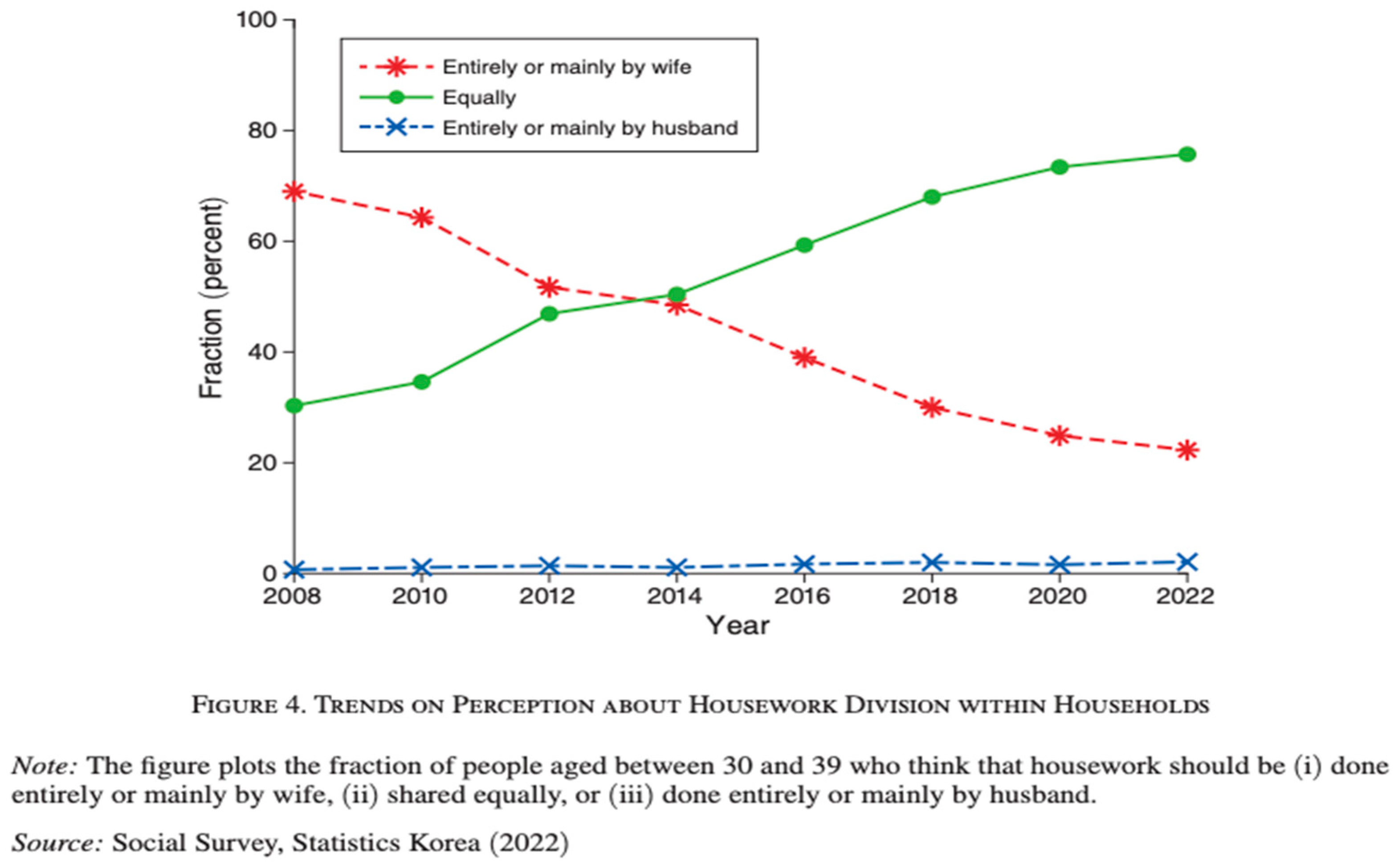

- Doepke, M.; Kindermann, F. (2019). Bargaining over babies: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. American Economic Review, 109(9), 3264-3306. [CrossRef]

- Goldin, C. (2024). Babies and the macroeconomy. NBER Working Paper 33311. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w33311.

- Myoung, S.; Park, J.; Yi, J. (2021). Social norms and fertility. Journal of the European Economic Association, 19(5), 2429-2466.

- Baek, S.U.; Lee, Y.M.; Won, J.U.; Yoon, J.H. (2024). Association between husband’s participation in household work and the onset of depressive symptoms in married women: A population-based longitudinal study in South Korea. Social Science & Medicine, 362, 117416. [CrossRef]

- The Economist. (2025, March 5). The best places to be a working woman in 2025. Available online: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2025/03/05/the-best-places-to-be-a-working-woman-in-2025.

- OECD (2023). Gender wage gap. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/gender-wage-gap.html.

- OECD Family Database. (2022). Usual working hours per week by gender. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/data/datasets/family-database/lmf_2_1_usual_working_hours_gender.pdf.

- Chang, K. (2022). The logic of compressed modernity. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Statistics Korea. (2022). Social Survey. Family, Education and Training, Health, Crime and Safety, Environment. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a20111050000&bid=11761.

- Burn, J. (2024, January, 8). A new global gender divide is emerging: Opinion data points. Financial Times. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/29fd9b5c-2f35-41bf-9d4c-994db4e12998.

- N-po generation. (2025, February 11). In Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/N-po_generation.

- OECD (2022, December). Share of births outside of marriage. OECD Family Database. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/data/datasets/family-database/sf_2_4_share_births_outside_marriage.pdf.

- Hancocks, P. (2022, December 4). South Korea spent $200 billion, but it can’t pay people enough to have a baby. CNN World. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2022/12/03/asia/south-korea-worlds-lowest-fertility-rate-intl-hnk-dst.

- Weaver, S. (2025, April 1). It now costs nearly 300K to raise a child; here’s where it’s most expensive. LiveNOW from FOX. Available online: https://www.livenowfox.com/news/cost-to-raise-child-300k-where-most-expensive.

- Tappe, A. (2022, April 9). Child care is expensive everywhere. But this country tops the list. CNN Business. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2022/04/09/economy/global-child-care-costs-us-china/index.html.

- Cho, J. (2021). A study on the problems and improvement tasks of the Framework Act on low birth in an aging society. Chungnam Law Review, 32(1), 11-42. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Masatsuku, N. (2024). A study of factors influencing happiness in Korea: Topic modeling and neural network analysis. Data & Metadata, 3, 238. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2022). Fertility rate, total (birth per woman). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).