Key Observations

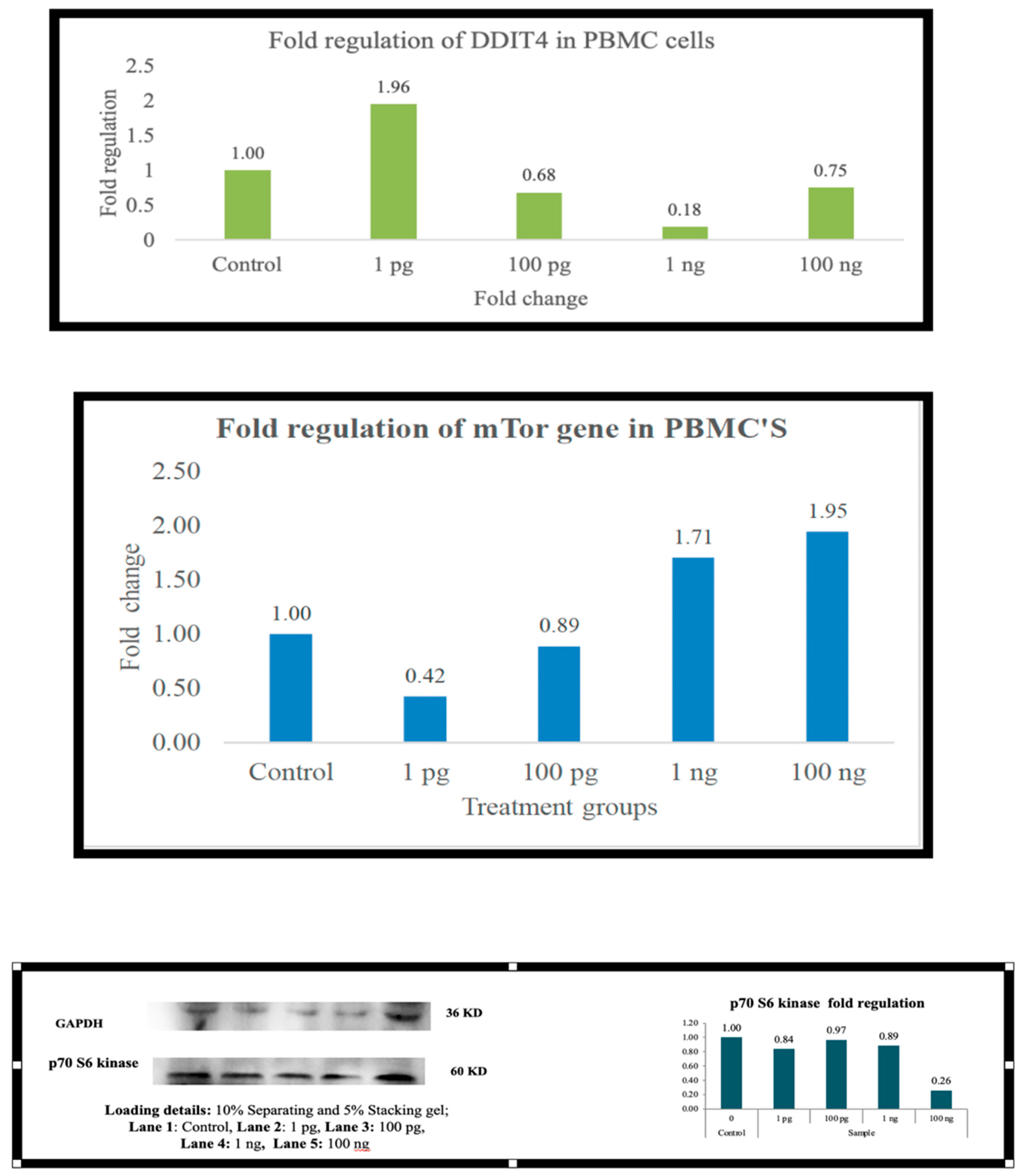

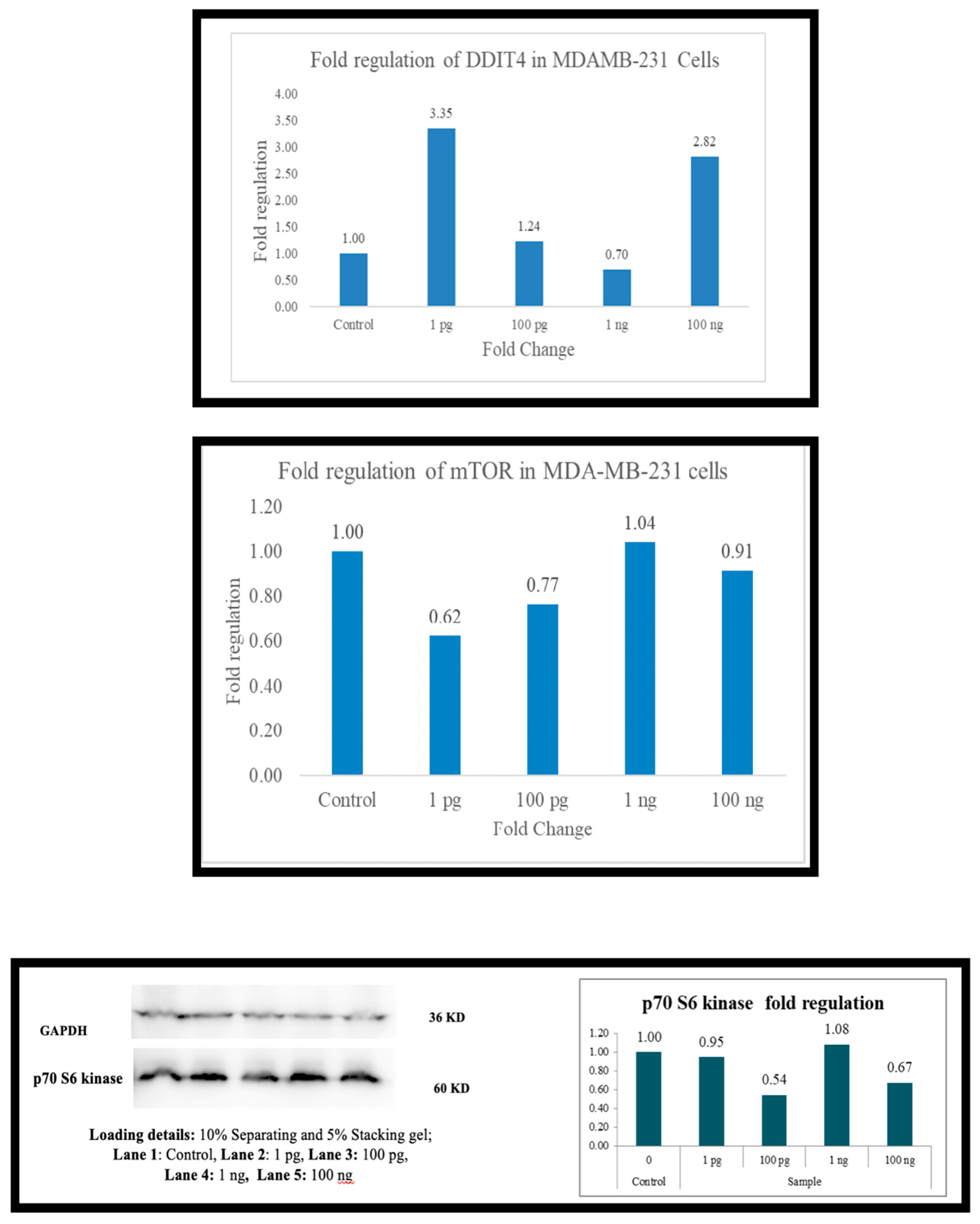

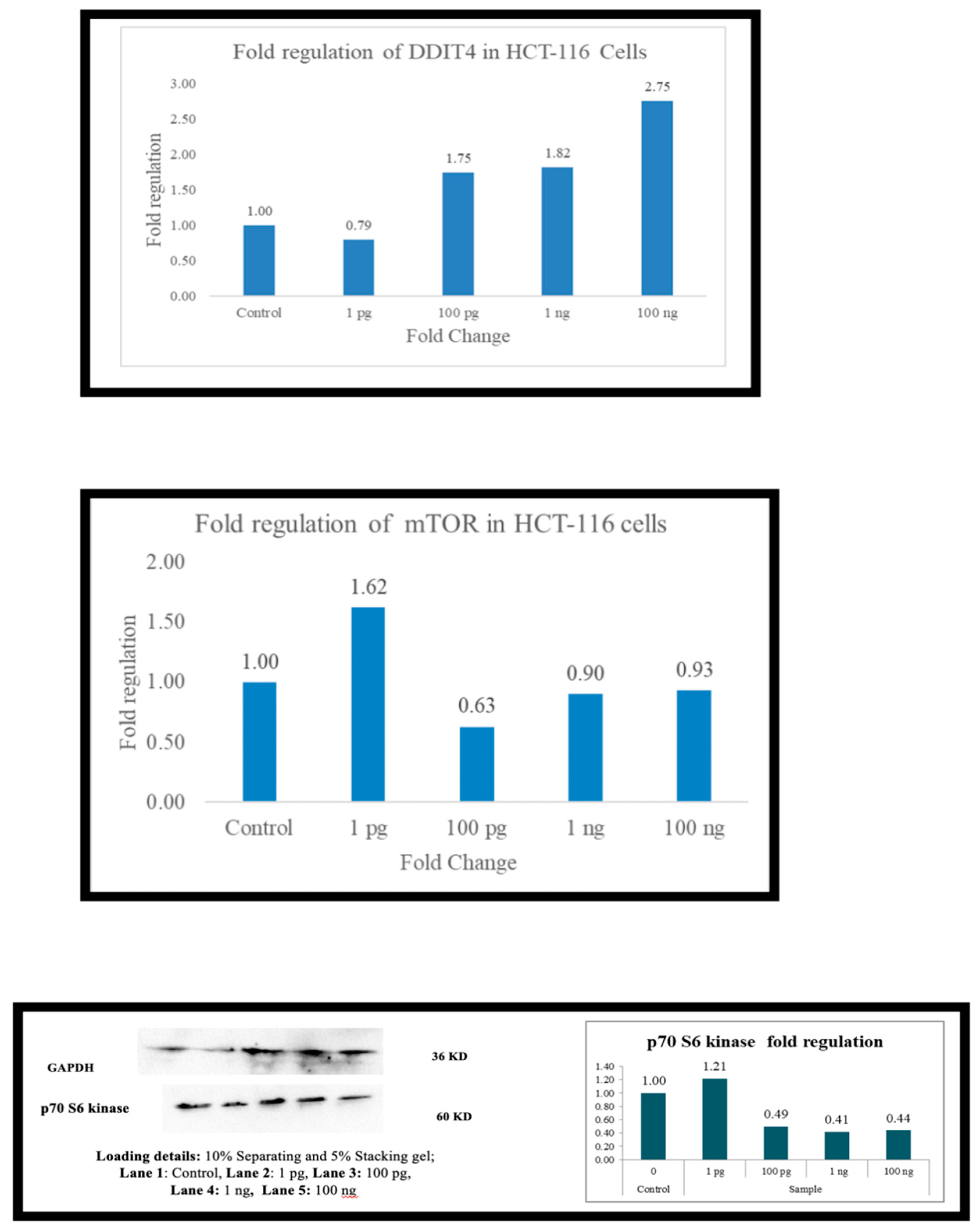

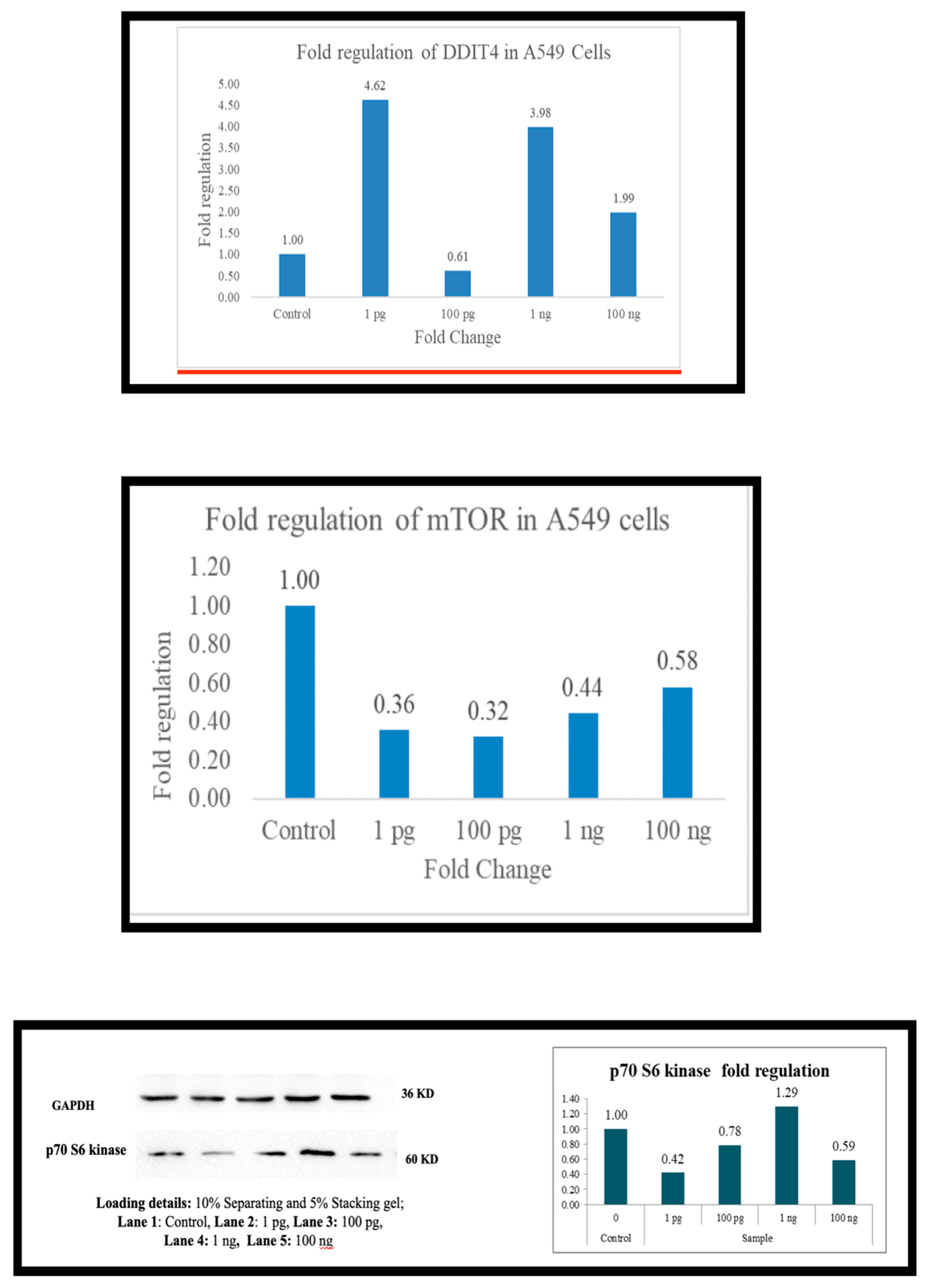

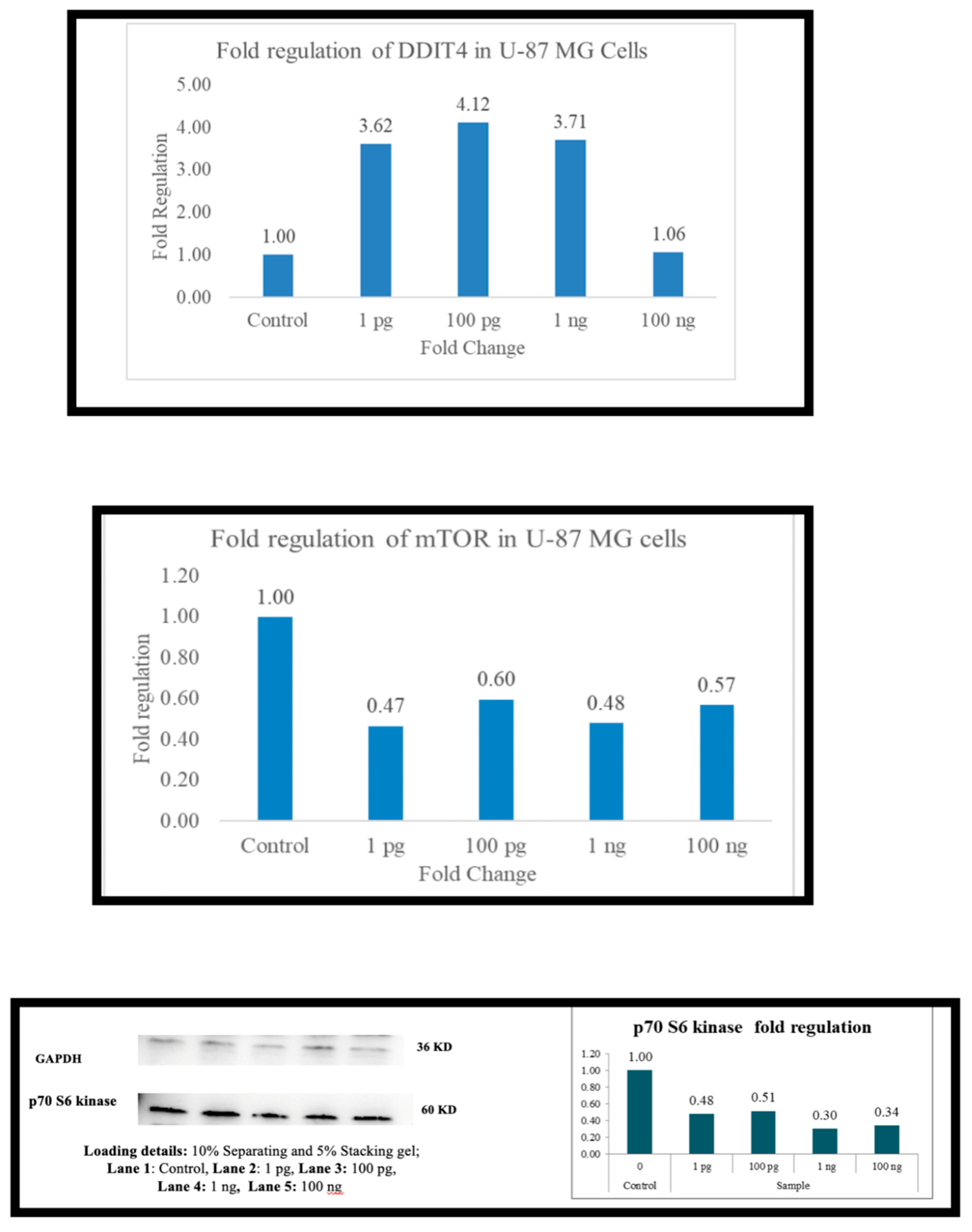

Metadichol increases DDIT4 expression, but mTOR and P70S6 kinase expression are downregulated. Conversely, decreases in DDIT4 are associated with increased mTOR and P70S6 kinase levels.

The effects are consistent in PBMCs (immune cells) and various cancer cell lines (U87, A-549, MDAMB-231-HCT116, and Hep G2.

The involvement of DDIT4, mTOR, and p70S6K in various physiological processes and pathological conditions, including cancer, diabetes, and aging, underscores their potential as therapeutic targets. Metadichol shows significant promise in targeting DDIT4, mTOR, and p70S6K for cancer treatment, given the crucial roles of these proteins in cancer cell growth, survival, and metastasis.

Compared with most mTOR, p70S6K, and DDIT4 inhibitors described in the literature, which are active in the nanomolar to micromolar range, the activity of metadichol at 1 pg/mL (10‒12 g/mL) is exceptionally potent.

Metadichol’s ability to modulate DDIT4, mTOR, and P70S6 kinase suggests that it regulates cellular growth and stress responses. In cancer, it may inhibit proliferation, while in PBMCs, it could balance immune function. These findings highlight the potential of metadichol as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of mTOR-driven diseases.

Keywords: mTOR, rapamycin, P70S6 kinase, DDIT4, PBMC, cancer cell lines , U87, A-549, MDAMB-231-HCT116, and Hep G2, metadichol, long-chain lipid aging alcohols, antiaging pathways, and anticancer pathways.

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and its key downstream effector, p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (p70S6K), play multifaceted roles in human biology and the pathogenesis of various diseases. mTOR, a highly conserved serine/threonine kinase [

1,

2], functions as a central signaling hub, integrating a diverse array of intracellular and extracellular signals to precisely control cellular growth, metabolism, and survival [

1,

3]. The profound impact of mTOR on cellular homeostasis is underscored by its dysregulation in a wide spectrum of human diseases [

4,

5]. p70S6K, a crucial downstream target of mTOR [

6,

7], plays a pivotal role in mediating many of the effects of mTOR on protein synthesis and cell growth [

3,

6]. Understanding the intricate interplay between mTOR and p70S6K is crucial for comprehending their contributions to normal physiological processes and the development of various pathologies. mTOR and p70S6K:

mTOR, a 289-kDa serine/threonine kinase belonging to the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-related kinase family [

1], is associated with two distinct multiprotein complexes: mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) [

1,

4]. While sharing the catalytic mTOR subunit, these complexes exhibit distinct regulatory mechanisms and downstream effects [

1,

8]. mTORC1, the rapamycin-sensitive complex [

1,

2], is composed of mTOR, Raptor, mLST8, PRAS40, and Deptor [

1]. Its primary function is to promote anabolic processes, including protein synthesis, ribosome biogenesis, and lipid biosynthesis [

1,

8]. Simultaneously, mTORC1 suppresses catabolic processes such as autophagy, which is a crucial cellular process for degrading damaged organelles and proteins. The precise roles of the regulatory subunits within mTORC1 remain an active area of research [

1], although Raptor is believed to be crucial for substrate recruitment and mTORC1 kinase activity [

1]. While not essential for in vivo function mLST8 may play a role in complex stability. PRAS40 and Deptor function as negative regulators of mTORC1 [

1]; upon mTORC1 activation, Deptor is phosphorylated, decreasing its inhibitory interaction with mTORC1 [

1]. mTORC2, the rapamycin-insensitive complex [

1,

8], consists of mTOR, Rictor, mSIN1, Protor-1, mLST8, and Deptor [

1]. Unlike mTORC1, mTORC2 is not directly inhibited by rapamycin [

1]. Its primary functions involve regulating cell survival, cytoskeletal organization, and the activation of Akt [

1,

3], a serine/threonine kinase that plays a crucial role in various cellular processes. The interaction between Rictor and mSIN1 is essential for mTORC2 stability [

1], and Protor-1 may also contribute to mTORC2 function [

1]. Deptor, a shared component of both complexes, acts as a negative regulator of mTORC1 and mTORC2 [

1].

p70S6K, a member of the AGC family of protein kinases [

8], is a critical downstream effector of mTORC1 [

6,

10]. mTORC1 activates p70S6K through phosphorylation at multiple sites, notably Thr389 and Thr421/Ser424. [

6,

9]. This phosphorylation enhances p70S6K kinase activity, leading to the phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 (rpS6). The phosphorylation of rpS6 promotes the translation of specific mRNAs, many encoding proteins involved in ribosome biogenesis and cell growth [

3,

6]. In addition to rpS6, p70S6K influences other aspects of mRNA translation, including initiation and elongation [

6,

10], contributing to the overall regulation of protein synthesis. The precise mechanisms by which p70S6K exerts these effects are still under investigation, but its role as a central mediator of the effects of mTORC1 on protein synthesis is well established.

The activity of mTOR is tightly regulated by a complex interplay of upstream signals, ensuring that cellular growth and metabolism are appropriately matched to environmental conditions [

1,

11]. These signals include those associated with growth factors, hormones, nutrients, and cellular stress. Growth factors, such as insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), activate the PI3K/Akt pathway [

1,

11]. Akt, a serine/threonine kinase, subsequently phosphorylates and activates mTORC1. This activation is crucial for promoting cell growth and protein synthesis in response to growth stimuli. However, this pathway is also implicated in the development of various cancers because of its role in promoting cell growth and proliferation [

1,

11]. Amino acids, particularly leucine, are critical for mTORC1 activation [

11,

12]. The mechanism involves the lysosomal localization of mTORC1 and the activation of Rag GTPases. Rag GTPases act as molecular switches, mediating the recruitment of mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface, where it can access its activators and substrates. This lysosomal localization is crucial for the amino acid-dependent activation of mTORC1.The cellular energy status, sensed by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [

1,

12], also significantly impacts mTOR activity. AMPK acts as a cellular energy sensor, becoming activated under conditions of low energy (high AMP:ATP ratio) [

1,

11]. Activated AMPK inhibits mTORC1 ensuring that energy-consuming anabolic processes are suppressed during energy stress. This regulatory mechanism prevents the wasteful consumption of cellular resources when energy is limited. The interplay between AMPK and mTORC1 is crucial for maintaining cellular energy homeostasis [

1,

12].

mTORC1 hyperactivation in cancer mTORC1 is frequently hyperactivated in a wide range of human cancers [

13,

14], contributing significantly to uncontrolled cell growth, proliferation, and survival [

4,

13]. This aberrant activation can arise from several mechanisms: mutations in upstream signaling components, mutations or amplifications in genes encoding PI3K, Akt, or TSC1/2, which lie upstream of mTOR in signaling pathways, can lead to constitutive activation of mTORC1 [

11,

13]. These mutations disrupt the normal regulatory mechanisms that control mTORC1 activity, resulting in persistent activation and uncontrolled cell growth. Increased expression of growth factors or oncogenes, elevated levels of growth factors, such as insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), or the overexpression of oncogenes can stimulate the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [

7,

13]. These factors can lead to sustained activation of mTORC1, driving tumorigenesis and promoting cancer cell survival. Altered nutrient sensing: Cancer cells often exhibit altered nutrient metabolism, leading to dysregulation of mTORC1 activity [

12]. This includes changes in amino acid uptake and metabolism, which can contribute to the persistent activation of mTORC1 and promote tumor growth. The hyperactivation of mTORC1 in cancer cells promotes several hallmarks of malignancy, including increased protein synthesis, enhanced cell growth, resistance to apoptosis, and increased angiogenesis [

4,

12]. These findings suggest that mTOR is a desirable target for cancer therapy.

mTOR inhibitors, such as rapamycin and its analogs (rapalogs) [

11,

14], have shown some clinical success in treating certain cancers, primarily by inhibiting mTORC1. However, these first-generation inhibitors often have limitations, such as feedback activation of other growth pathways. The inhibition of mTORC1 can trigger compensatory activation of other growth-promoting pathways, such as the PI3K/Akt pathway [

1,

14].

This feedback mechanism can limit the effectiveness of mTORC1 inhibitors and contribute to the development of drug resistance. Limited efficacy in some cancer types: Rapalogs have shown variable efficacy across different cancer types, with some tumors exhibiting little or no response to treatment [

15,

16]. This limited efficacy highlights the need for a deeper understanding of the genetic and molecular characteristics that predict responsiveness to mTOR inhibitors. Development of resistance: Cancer cells can develop resistance to rapalogs through various mechanisms, including mutations in mTOR or its upstream regulators or through the activation of alternative growth pathways. Overcoming this resistance is a significant challenge in developing effective mTOR-targeted therapies. To address these limitations, newer, second-generation mTOR inhibitors are being developed [

1,

15]. These inhibitors often target mTORC1 and mTORC2, aiming to prevent feedback activation of other growth pathways and improve clinical efficacy. The development of more selective and potent mTOR inhibitors, combined with a better understanding of the genetic context of tumors, is crucial for optimizing the effectiveness of mTOR-targeted therapies [

13,

15].

The mTOR pathway significantly promotes the development of drug resistance in cancer [

13,

14]. In some cases, inhibiting mTOR can sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy [

14,

16], suggesting that mTOR inhibition can enhance the effectiveness of other anticancer agents. However, in other cases, mTOR hyperactivation can promote drug resistance indicating that mTOR can be a driver of resistance to various cancer treatments. Understanding the complex interplay between mTOR and drug resistance is crucial for developing effective combination therapies to overcome resistance mechanisms and improve treatment. The development of therapies targeting mTOR and other resistance mechanisms is an area of ongoing research.

Insulin resistance and diabetes mTORC1 play central roles in regulating insulin signaling [

1,

3], a complex process that controls glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, and overall energy homeostasis [

1,

2]. Insulin stimulates mTORC1 activity, increasing protein synthesis and glucose uptake. This is a crucial aspect of the anabolic insulin response, enabling cells to utilize glucose effectively for energy production and growth. However, chronic hyperactivation of mTORC1 can disrupt insulin signaling, resulting in insulin resistance [

1,

17], a hallmark of type 2 diabetes [

1,

17]. In insulin resistance, cells become less responsive to the effects of insulin, leading to impaired glucose uptake, elevated blood glucose levels, and, ultimately, the development of type 2 diabetes. mTOR inhibitors have shown promise in preclinical models of metabolic diseases [

15,

17], as they improve insulin sensitivity and reduce obesity. These findings suggest that modulating mTOR activity could be a therapeutic strategy for addressing metabolic dysfunction. However, the clinical translation of mTOR inhibition for treating metabolic diseases is still in its early stages [

15,

17], with challenges including the potential for side effects, such as immunosuppression [

15,

18], and the need for further research to optimize treatment strategies and identify appropriate patient populations. The long-term effects of mTOR inhibition on metabolic health require careful evaluation.

mTOR signaling is crucial for various aspects of brain function, including neuronal development, synaptic plasticity, and cognitive function [

19,

20]. Its activity is tightly regulated to ensure proper neuronal function and overall brain health. However, dysregulation of mTOR signaling has been implicated in several neurological disorders [

21,

22,

23]. Depending on the disease and underlying mechanisms, this dysregulation can manifest as either hyperactivation or hypoactivation of the mTOR pathway.

Hyperactivation of mTOR has been linked to neurodegeneration in several neurological diseases [

22,

24], leading to neuronal damage and dysfunction. This hyperactivation can disrupt various cellular processes, including protein synthesis, autophagy, and synaptic function, contributing to neuronal cell death and the progression of neurodegenerative disorders.

Conversely, mTOR inhibition has shown neuroprotective effects in preclinical models [

20,

22], suggesting that modulating mTOR activity may be a therapeutic approach for neurodegenerative diseases. The complex mechanisms underlying these effects involve interactions with various pathways, including autophagy, metabolism, and inflammation [

22,

24]. Further research is needed to fully elucidate these mechanisms and develop effective mTOR-targeted therapies for neurodegenerative diseases.

mTOR and inflammatory mTOR signaling regulate inflammatory responses [

13,

25], a complex network of cellular interactions that contribute to innate and adaptive immune responses. mTOR can influence the production of inflammatory cytokines and the activation of immune cells (Dysregulation of mTOR signaling can contribute to chronic inflammation, which underlies many diseases. The specific roles of mTOR in different inflammatory diseases, such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis [

25], are areas of ongoing research. Understanding how mTOR regulates inflammation is essential for developing targeted therapies for these conditions.

mTOR signaling is involved in cardiac hypertrophy and cardiovascular disease [

9,

26]. In the heart, mTOR regulates protein synthesis and cell growth. Hyperactivation of mTOR can contribute to pathological cardiac remodeling and heart failure (whereas mTOR inhibition can have beneficial effects on cardiac function The interplay among mTOR signaling, nutrient sensing, and metabolic stress is crucial in the development of cardiovascular diseases [

26,

27]. Further research is needed to characterize the role of mTOR in cardiovascular disease fully and to develop targeted therapies for these conditions.

mTOR signaling is implicated in aging [

13,

28]. Hyperactivation of mTORC1 is associated with accelerated aging and a reduced lifespan in various model organisms [

13,

29]. This hyperactivation can contribute to age-related cellular dysfunction and the development of age-related diseases. Conversely, mTOR inhibition can extend lifespan suggesting that mTOR signaling may be a target for interventions to slow the aging process. The mechanisms by which mTOR influences aging are complex and involve interactions with various pathways, including autophagy, metabolism, and stress responses. Further research is needed to elucidate these mechanisms fully and develop effective interventions targeting mTOR signaling to improve health span and lifespan.

- DDIT4

IT4 and its Relationships with mTOR and p70S6 Kinase

The DDIT4 gene, also known as REDD1 (Regulated in Development and DNA Damage Response 1), encodes a stress-responsive protein that plays a pivotal role in cellular adaptation to environmental challenges such as hypoxia, DNA damage, and nutrient deprivation. Initially, identified as a gene induced by DNA damage and hypoxia, DDIT4 has since emerged as a key regulator of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, a central hub for coordinating cell growth, proliferation, and metabolism [

29,

30]. The DDIT4 protein exerts its effects by negatively modulating mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), a nutrient-sensitive kinase complex that integrates signals from growth factors, energy status, and amino acid availability to drive anabolic processes.

The relationship between DDIT4 and mTORC1 is mediated through the TSC1/TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis complex 1/2) tumor suppressor complex. Under stress conditions, DDIT4 is upregulated and promotes the assembly and activity of TSC1/TSC2, which inhibits the small GTPase Rheb (Ras homolog enriched in the brain), a direct activator of mTORC1 [

31]. By suppressing mTORC1 activity, DDIT4 reduces the phosphorylation of downstream effectors, notably p70S6 kinase (p70S6K), also known as ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 (RPS6KB1). p70S6K is a critical mTORC1 substrate that, when phosphorylated at Thr389, enhances protein synthesis by activating ribosomal protein S6 and other translational machinery components [

32]. Thus, DDIT4-mediated inhibition of mTORC1 leads to decreased p70S6K activity, shifting cellular resources away from growth and toward survival or quiescence under stress.

This regulatory axis—DDIT4, mTORC1, and p70S6K—has profound implications across physiological and pathological contexts, including cancer, metabolic disorders, and aging. For example, in hypoxic tumor microenvironments, DDIT4 induction can paradoxically support cancer cell survival by fine-tuning mTORC1 activity, whereas under nutrient-rich conditions, its downregulation may permit unchecked p70S6K-driven proliferation [

33]. Understanding the dynamic interplay between DDIT4, mTOR, and p70S6K offers insights into cellular homeostasis and potential therapeutic targets for diseases characterized by dysregulated growth signaling. [

34,

35,

36].

mTOR inhibitors are categorized into three main types: rapalogs, ATP-competitive inhibitors, and dual PI3K/MTOR inhibitors, each with distinct mechanisms and therapeutic applications.

Rapalogs: First-generation mTOR inhibitors, such as sirolimus (rapamycin) and its analogs (temsirolimus, everolimus), primarily target mTORC1. They inhibit downstream signaling pathways, reducing protein synthesis and cancer cell proliferation [

37,

38]. Clinical trials have demonstrated their efficacy in treating advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and other conditions, such as tuberous sclerosis [

39,

40]. However, rapalogs do not inhibit mTORC2, which may limit their effectiveness and lead to side effects such as rash and stomatitis [

41,

42].

ATP-Competitive Inhibitors: These newer inhibitors directly target the ATP-binding site of mTOR, allowing them to inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2, potentially overcoming the limitations of rapalogs [

43]. Examples include AZD-8055 and INK128, which are currently in clinical trials.[

44] These inhibitors may provide broader antitumor effects and address resistance mechanisms associated with rapalogs [

45].

Dual PI3K/mTOR Inhibitors: These agents simultaneously inhibit both PI3K and mTOR, targeting multiple signaling pathways involved in cancer cell survival They have shown promise in preclinical and clinical settings, particularly for advanced cancers resistant to single-agent therapies [

46].

Clinical applications: mTOR inhibitors are utilized in various cancers, including breast cancer, RCC, and B-cell lymphomas. Everolimus has been approved for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer and has improved progression-free survival when combined with endocrine therapy [

47,

48]. In RCC, Temsirolimus has become a standard treatment for patients with poor prognoses [

49].

In vitro, the effective concentration of rapamycin is typically 1–100 nM (approximately 0.91–91 ng/ml, given its molecular weight of ~914 g/mol). Everolimus: A rapamycin analog that inhibits mTORC1 and decreases P70S6K activity. Although effective at 1–20 nM (~1–20 ng/ml), despite their therapeutic potential, mTOR inhibitors can cause significant side effects, including metabolic disturbances and skin reactions [

50]. The management of these adverse effects is crucial for maintaining patient quality of life and treatment adherence.

Ongoing research aims to optimize the use of mTOR inhibitors, including identifying biomarkers for patient selection and exploring combination therapies to increase their efficacy and overcome resistance [

1,

50]. mTOR and p70S6K are central regulators of cellular processes, and their dysregulation plays a significant role in a broad array of human diseases. The development of effective therapeutic strategies targeting this pathway requires a deeper understanding of the complex regulatory mechanisms governing mTOR signaling. There is a need to develop more specific and compelling mTOR modulators with improved safety profiles. The development of next generation mTOR inhibitors with enhanced specificity and potency and reduced side effects is essential for improving therapeutic efficacy and patient safety. Investigating the interplay between mTOR signaling and other pathways:

Our results revealed that metadichol [

51], a nanoemulsion of long-chain lipid alcohols, the major constituent of which is C28 straight-chain alcohol (85%), modulates the mTOR and P70S6K pathways at 1 pg/ml (10⁻¹² g/ml). This is an extremely low dose of metadichol, which is a nontoxic molecule [

52,

53,

54] derived from food sources, and we explored its ability to regulate mTOR, DDIT4, and cancer cells, as evidenced by Q-RT‒PCR techniques, and p79S6 kinase activity in PBMCs, as evidenced by Western blot techniques.

All work was conceived, planned and supervised by the author and outsourced to the service provider Skanda Life Sciences (Bangalore, India).

A549m U-87 MG, HepG2, HCT116 and MDAMB-231 cells were obtained from ATCC (USA). Primary antibodies were purchased from E-lab Science (Maryland, USA). The primers used were obtained from Eurofins Bangalore, India. All other molecular biology reagents were obtained from Sigma Aldrich, Bangalore, India.

Preparation of the blood sample- Fresh human blood was collected in EDTA-containing tubes, and then fresh blood was diluted with PBS at a 1:1 ratio and mixed by inverting the tube.

In the 15 ml centrifuge tube, 5 ml of Histopaque-1077 was added such that 5 ml of prepared blood was slowly layered on the histopaque from the edge of the tube without disturbing the histopaque layer. Then, the tubes were centrifuged at 400 X g for exactly 30 min at room temperature with brake-off settings. After centrifugation, the upper layer was discarded with a Pasteur pipette without disturbing the interphase layer. The interphase layer was carefully transferred to a clean centrifuge tube. The cells will be washed with 1X PBS and again centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 mins. (2X). After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was collected in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were counted, and their viability was checked with a hemocytometer. The cell count was adjusted to 10x106 cells/2 ml. Two milliliters of cell suspension was added to each dish in P35 dishes. The cells were then treated with various concentrations of the test sample. After incubation, the cells were harvested for protein isolation via RIPA buffer.

The cells were maintained at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml, seeded into 6-well plates and incubated for 24 hrs at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 24 h of seeding, the media was carefully removed, and the cells were treated with the test samples (the concentration was selected on the basis of the MTT experiment) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator.

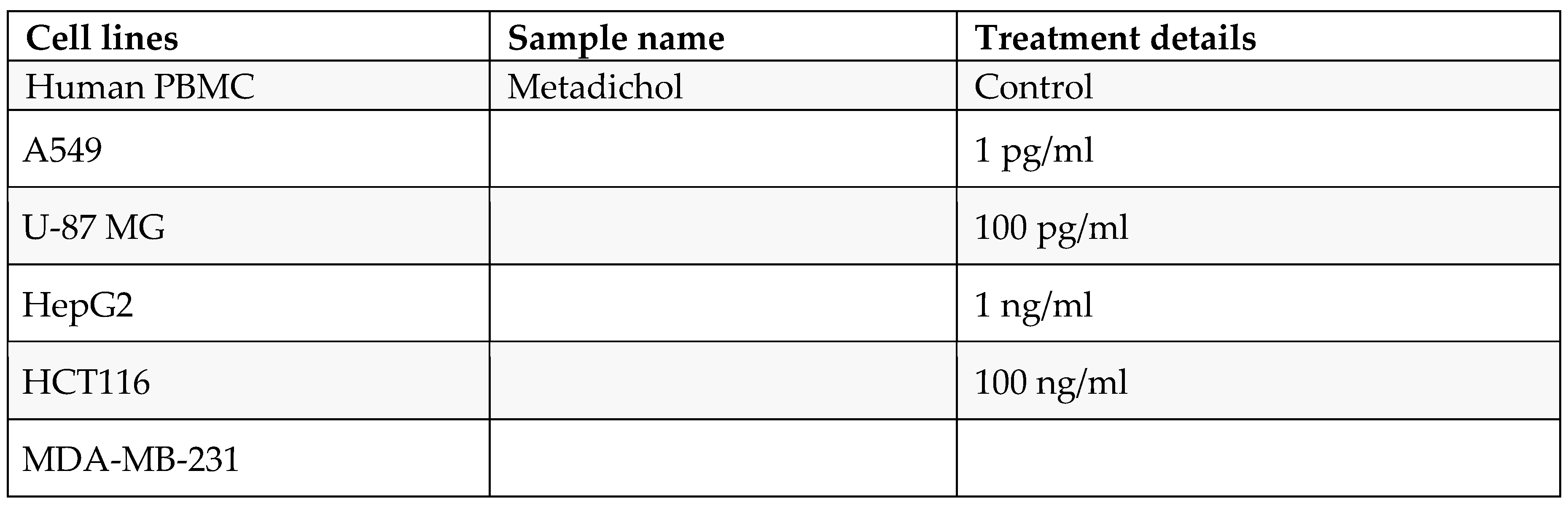

Table 1.

Experimental conditions.

Table 1.

Experimental conditions.

The treated cells were dissociated, rinsed with sterile 1X PBS and centrifuged. The supernatant was decanted, and 0.1 ml of TRIzol was added and gently mixed by inversion for 1 min. The samples were allowed to stand for 10 min at room temperature. To this mixture, 0.75 ml of chloroform was added per 0.1 ml of TRIzol used. The contents were vortexed for 15 seconds. The tube was allowed to stand at room temperature for 5 mins. The resulting mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The upper aqueous phase was collected in a new sterile microcentrifuge tube, to which 0.25 ml of isopropanol was added, and the mixture was gently mixed by inverting the contents for 30 seconds and then incubated at -20°C for 20 minutes. The contents were subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the RNA pellet was washed by adding 0.25 ml of 70% ethanol. The RNA mixture was subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully discarded, and the pellet was air dried. The RNA pellet was then resuspended in 20 μl of DEPC-treated water. The total RNA yield was quantified via a Spectra drop (Spectramax i3x, Molecular Devices, USA).

RNA integrity was confirmed through spectrophotometric analysis, and all samples yielded high-quality RNA suitable for qPCR.

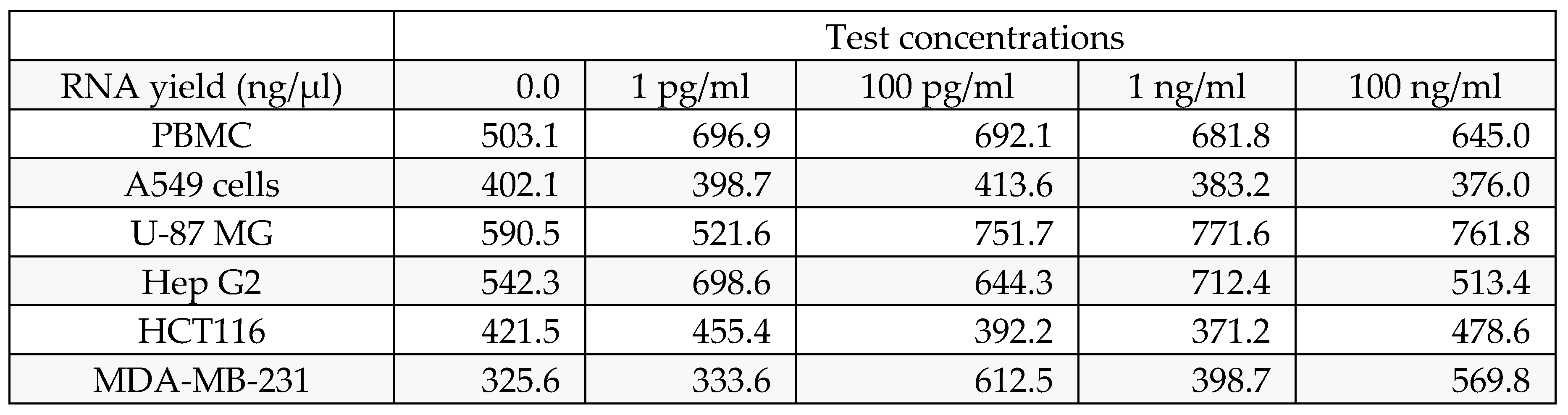

Table 2.

mTOR RNA yield.

| |

Test concentrations |

| RNA yield (ng/µl) |

0 |

1 pg/ml |

100 pg/ml |

1 ng/ml |

100 ng/ml |

| Human PBMC's |

503.12 |

696.88 |

692.123 |

681.84 |

644.96 |

| A549 cells |

402.1 |

398.7 |

413.6 |

383.2 |

376 |

| HCT116 |

421.5 |

455.4 |

392.2 |

371.2 |

478.6 |

| MDA-MB-231 |

325.6 |

333.6 |

612.5 |

398.7 |

569.8 |

| U-87 MG |

590.5 |

521.6 |

751.7 |

771.6 |

761.8 |

| Hep G2 |

542.3 |

698.6 |

644.3 |

712.4 |

513.4 |

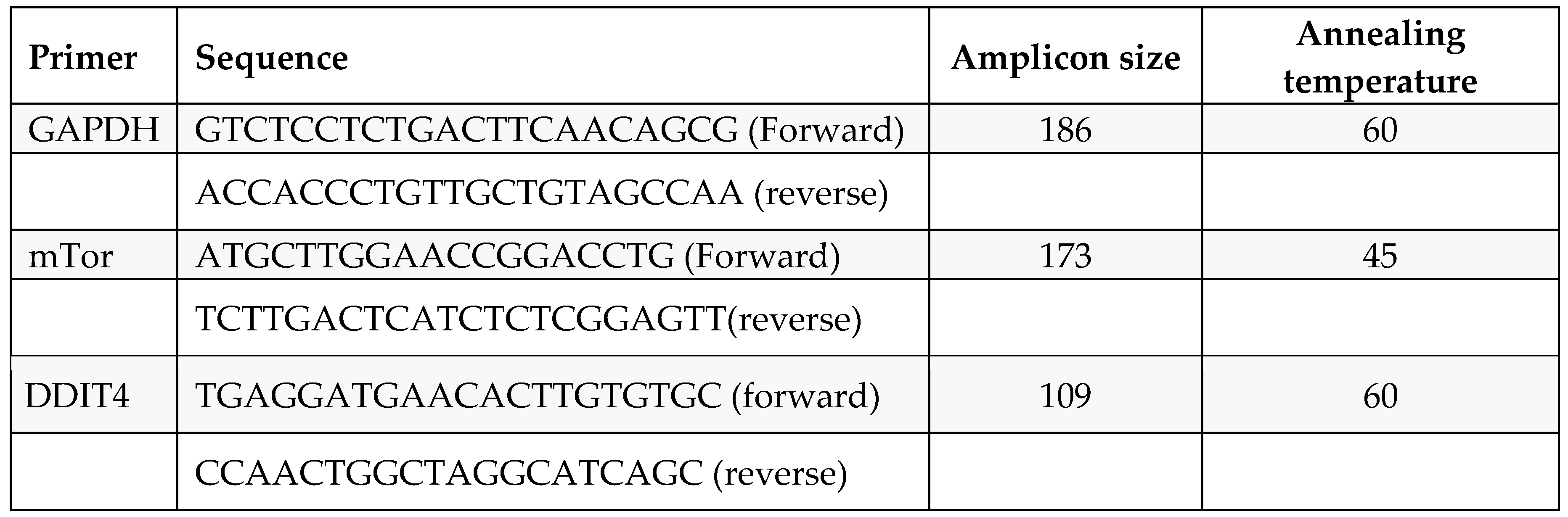

Table 3.

DDIT 4 RNA Yields.

Table 3.

DDIT 4 RNA Yields.

cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of RNA via a cDNA synthesis kit from the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TAKARA) with oligo dT primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction volume was set to 20 μl, and cDNA synthesis was performed at 50°C for 30 min, followed by RT inactivation at 85°C for 5 min using Applied Biosystems Veritii. The cDNA was further used for real-time PCR analysis.

The PCR mixture (final volume of 20 μl) contained 1.4 μl of cDNA, 10 μl of SYBR Green Master mix, and 1 μM complementary forward and reverse primers specific for the respective target genes. The reaction was carried out with enzyme activation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by a 2-step reaction with initial denaturation and an annealing-cum-extension step at 95°C for 5 seconds, annealing for 30 seconds at the appropriate respective temperature amplified for 39 cycles, followed by secondary denaturation at 95°C for 5 seconds, and 1 cycle with a melt curve capture step ranging from 65°C to 95°C for 5 seconds each. The obtained results were analyzed, and the fold change in expression or regulation was calculated.

The fold change was calculated via the following equation:

(ΔΔ CT Method)

The relative expression of the target gene in relation to the housekeeping gene (β-actin) and untreated control cells was determined via the comparative CT method.

The delta CT for each treatment was calculated via the following formula:

Delta Ct = Ct (target gene) – Ct (reference gene)

To compare the individual sample from the treatment with the untreated control, the delta CT of the sample was subtracted from the control to obtain a delta delta CT.

Delta delta Ct = delta Ct (treatment group) – delta Ct (control group)

The fold change in target gene expression for each treatment was calculated via the following formula: Fold change = 2^(-deltadelta Ct)

Total protein was isolated from 106 cells via RIPA buffer supplemented with the protease inhibitor PMSF. The cells were lysed for 30 min at 4°C with gentle inversion. The cells were subsequently centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min, after which the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. The protein concentration was determined via the Bradford method, and 25 µg of protein was mixed with 1X sample loading dye containing SDS and loaded on a gel. The proteins were separated under denaturing conditions using Tris-glycine running buffer.

Table 5.

Western blot experimental conditions.

Table 5.

Western blot experimental conditions.

| Protein Markers |

Separating Gel Percentage |

Stacking Gel Percentage |

Antibody catalog no. with dilution details |

Exposure Time |

| GAPDH |

10% |

5% |

Elab science -AB-20072 (1:1000) |

5 secs. |

| Phospho-p70 S6 kinase alpha (Ser418) |

10% |

5% |

Elab science -AB-21476 (1:1500) |

20-30 secs |

The proteins were transferred to methanol-activated PVDF membranes (Invitrogen) via a Turbo transblot system (Bio-Rad, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% BSA for 1 hr and incubated with the appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with a species-specific secondary antibody for 1 hr at RT. The blots were washed and incubated with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (Merck) for 1 min in the dark, and images were captured at appropriate exposure settings via a ChemiDoc XRS system (Bio-Rad, USA).

Across the board (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), as the expression of DDIT4 is elevated, there is a downregulation of mTOR and, in most cells, p70S6 kinase. In PBMC there is downregulation of mTOR at 1 picogram, but downregulation of p70s6 kinase occurs at 100 ng. In A-549 cells, the downregulation was observed at 100 ng. HepG2 cells did not exhibit p70S6 kinase down-regulation. At 1 picogram, no small molecule in the current literature matches Metadichol

’s reported efficacy in upregulating DDIT4 at 1 pg/mL. While compounds such as dexamethasone [

38], rapamycin [

39], metformin [

40], and CoCl₂ [

41] can upregulate DDIT4 (typically by 2- to 8-fold), they require concentrations 10⁶ to 10¹² times greater, making the potency of Metadichol unique. Its ability to deliver nanoemulsions and target multiple receptors [

55] may explain this advantage.

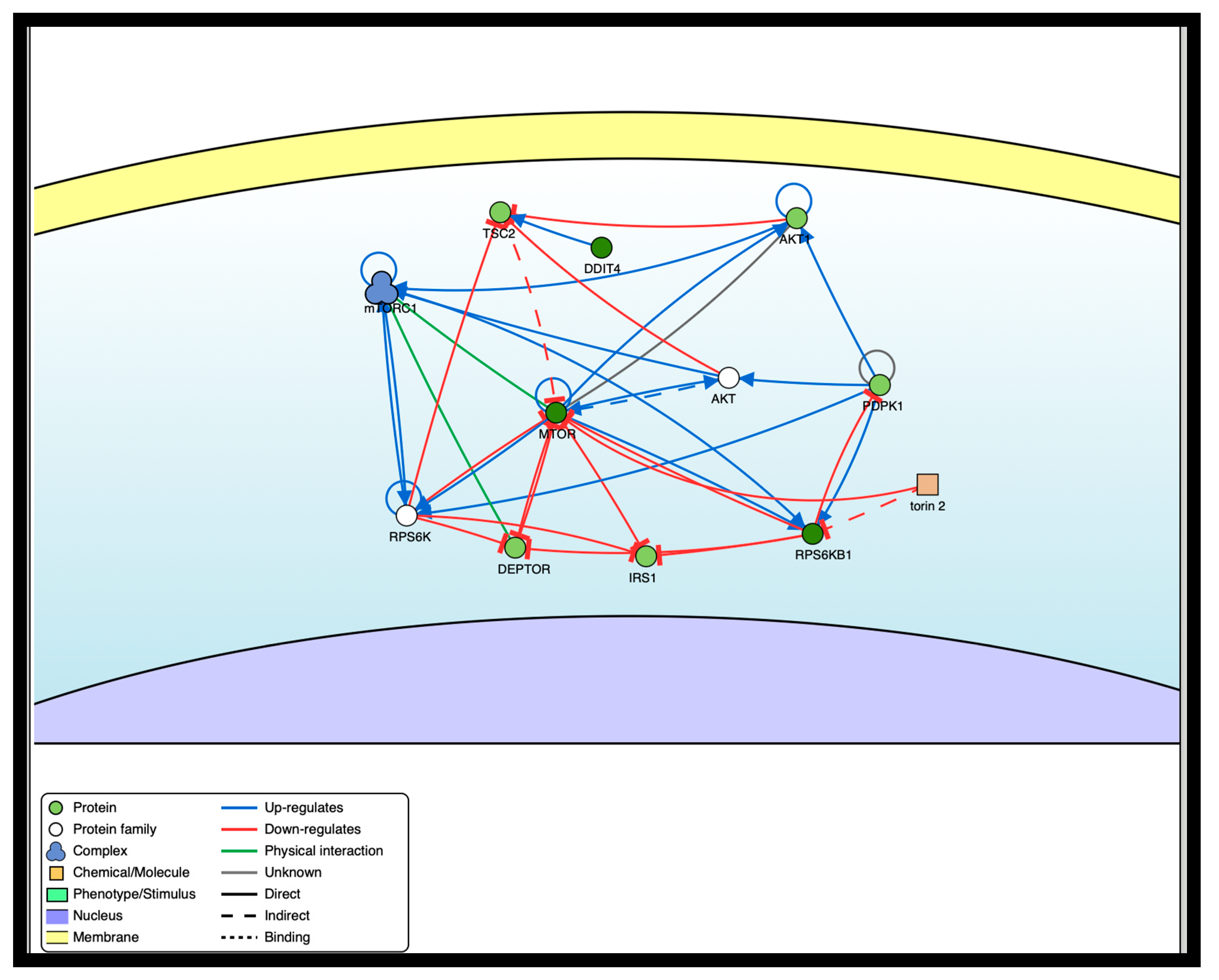

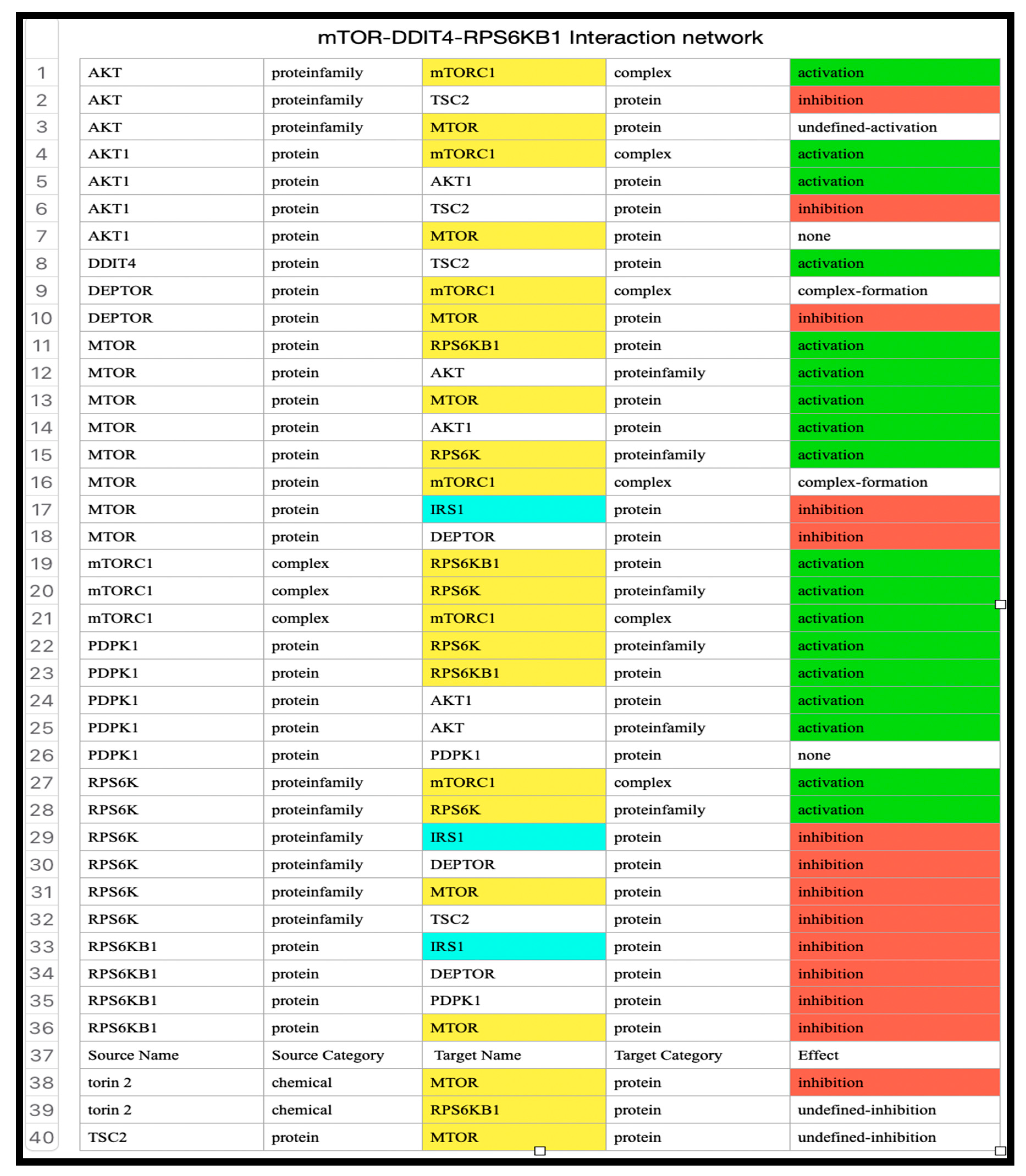

Metadichol, a nanoemulsion of long-chain alcohols, has emerged as a multifaceted modulator of cellular signaling, with documented effects on many pathways and its downstream effector, P70S6K. Our findings indicate that metadichol upregulates DDIT4 (DNA damage inducible transcript 4) at a concentration of 1 pg/ml, leading to the suppression of mTORC1 activity and subsequent inhibition of P70S6K expression. This finding aligns with the established role of DDIT4 as a stress-induced inhibitor of mTORC1, which is mediated through the TSC1/TSC2 complex and Rheb inactivation [

56,

57]. We used SIGNOR [

58], a repository of manually annotated causal relationships between proteins, to illustrate the interactions between various transcription factors that play a role in mTOR inhibition.

Table 5 shows the detailed interactions of the proteins involved in the network.

Previous studies have implicated Kruppel-like factors (KLFs), such as KLF2 and KLF4, as transcriptional regulators of DDIT4 in response to Metadichol [

55]. However, the broad bioactivity of metadichol suggests that additional mechanisms may contribute to mTOR and P70S6K suppression, potentially via nuclear receptor-mediated expression of sirtuins and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathways. [

59,

60]

Nuclear receptors (NRs), including PPARs, LXR, and VDR, are ligand-activated transcription factors that regulate metabolic and stress response genes. Given the structural similarity of metadichol to lipid-derived molecules, it may serve as a ligand or coactivator for these receptors. Notably, PPARγ and VDR have been linked to the transcriptional upregulation of SIRT1, an NAD+-dependent deacetylase with established roles in metabolic regulation [

61]. Metadichol can increase SIRT1 expression [

60], suggesting that this effect is NR dependent.[

62]

SIRT1 is a plausible mediator of mTOR suppression. It activates AMPK through the deacetylation of LKB1, an upstream kinase that phosphorylates TSC2, thereby inhibiting mTORC1 [

63]. This SIRT1-AMPK-mTOR axis represents a metabolic regulatory pathway distinct from the stress-induced KLF/DDIT4 mechanism. In the context of metadichol, NR-mediated SIRT1 upregulation could amplify AMPK activity, reducing mTORC1 signaling and P70S6K phosphorylation independently of DDIT4. Additionally, the promotion of autophagy by SIRT1, which is inhibited by active mTORC1, may further suppress P70S6K activity, as P70S6K negatively regulates autophagic flux [

64,

65].

Figure 7.

mTOR inhibition and interaction network.

Figure 7.

mTOR inhibition and interaction network.

Table 6.

Interaction network of transcription factors in the mTOR pathway.

Table 6.

Interaction network of transcription factors in the mTOR pathway.

Metadichol

’s ability to modulate TLRs [

59] offers another potential avenue for mTOR and P70S6K suppression. TLRs, which are critical to innate immunity, also influence metabolic pathways through crosstalk with mTORC1. Typically, TLR activation (e.g., via LPS) stimulates mTORC1 via PI3K/Akt signaling, promoting inflammation and cell survival [

66]. However, metadichol has a unique profile, modulating the expression of TLR1–10 and downregulating downstream adaptors such as MYD88, TRAF6, and IRAK4 in cancer cell lines [

45]. This suppression of TLR signaling components could disrupt Akt-driven mTORC1 activation, leading to reduced P70S6K activity. [

67].

Moreover, SIRT1 may intersect with TLR signaling by deacetylating NF-κB, attenuating inflammatory responses that otherwise sustain mTOR activity [

68]. Metadichol simultaneously upregulates SIRT1 via NRs [

62] and dampens TLR signaling; this dual action could synergistically inhibit mTORC1. Unlike the KLF/DDIT4 pathway, which relies on transcriptional stress responses, TLR-mediated effects involve immune‒metabolic crosstalk, offering a distinct mechanism. However, the precise impact of Metadichol

’s TLR modulation on mTOR remains speculative, as studies have not explicitly linked MYD88 downregulation to mTORC1 inhibition in this context. The inhibitory rather than stimulatory nature of Metadichol

’s TLR effects support its alignment with mTOR suppression, but targeted experiments (e.g., MYD88 knockdown) are needed to substantiate this pathway.

In addition to SIRT1 and TLRs, nuclear receptors such as PPARα might directly regulate autophagy-related genes (e.g., ULK1) that intersect with mTOR signaling, suggesting additional layers of control. [

69] The low concentration (1 pg/ml) at which Metadichol upregulates DDIT4 highlights its potency via the KLF pathway, but alternative mechanisms involving SIRT1 or TLRs may operate at different thresholds or in different cellular contexts, reflecting the pleiotropic nature of Metadichol. This complexity underscores its potential as a therapeutic agent.

Metadichol also expresses circadian genes [

70]. A considerable body of evidence has demonstrated robust interplay between the mTOR pathway and the circadian clock [

71,

72,

73,

74]. This interaction is not unidirectional; it is a dynamic interplay where each system influences the other. The mTOR pathway can influence the period length and synchronization of the circadian clock, affecting the timing and amplitude of circadian oscillations [

75]. Conversely, the circadian clock can regulate mTOR activity through the rhythmic expression of mTOR regulators or through the temporal control of nutrient availability [

76]. For example, the rhythmic expression of genes involved in nutrient sensing and metabolism can impact mTOR signaling [

77]. This bidirectional relationship underscores the importance of their coordinated function in maintaining cellular homeostasis and adaptation to environmental changes. Disruptions in this delicate balance can have profound consequences for cellular health and contribute to disease development.

The effects of metadichol on DDIT4, mTOR, and p70S6K involve coordinated regulation by SIRT1, VDR, PPAR, and circadian genes:

SIRT1 enhances NAD+ availability, suppressing mTOR and p70S6K while modulating DDIT4 [

78,

79].

VDR inhibits mTOR and p70S6K via AMPK and Akt, potentially inducing DDIT4 [

80].

PPAR-α suppresses mTOR and promotes DDIT4 via metabolic adaptation [

81,

82].

Circadian Genes: Link rhythmicity to mTOR suppression, with SIRT1 as an integrator [

83].

In PBMCs and cancer cell lines, metadichol may upregulate SIRT1 and VDR, activating PPAR and circadian pathways to inhibit mTOR/p70S6K-driven proliferation while inducing DDIT4 [

69,

84]. These findings support its anticancer and immunomodulatory potential.

The downregulation of both mTOR and p70S6 kinase by Metadichol in PBMC and cancer cell lines has several important implications Potential Anti-Cancer Effects

mTOR and p70S6K are key regulators of protein synthesis, cell growth, and proliferation. [

85] Their downregulation could inhibit cancer cell growth and division.

mTOR inhibition promotes autophagy, which can act as a tumor suppressor mechanism by eliminating damaged cellular components.[

86]

mTOR signaling is crucial for cancer stem cell maintenance and self-renewal [

87]. Its inhibition may restore

enhanced Therapeutic Sensitivity

Constitutive activation of p70S6K is associated with cisplatin resistance in some cancers [

88]. downregulation of this pathway could potentially re-sensitize resistant tumors to chemotherapy.

Inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K signaling may enhance the efficacy of other cancer treatments, including targeted therapies and immunotherapies [

89].

Metabolic Effects

Altered Cellular Metabolism

mTOR is a central regulator of cellular metabolism [

86]. Its inhibition could disrupt cancer cells' metabolic adaptations, potentially making them more vulnerable to stress.

Immune System Modulation

In PBMCs, mTOR inhibition can promote the development of memory cells and enhance overall immune response [

90].

Inhibition of mTORC1/p70S6K signaling has been shown to elevate PD-L1 levels in some cancer cells [

89]. This could have implications for combining Metadichol with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Potential Therapeutic Applications

Broad-Spectrum Anti-Cancer Activity

Given the frequent dysregulation of mTOR signaling in various cancers, Metadichol could potentially have broad anti-cancer effects [

91]

Targeted Therapy for PTEN-Deficient Cancers: Metadichol might be particularly effective against cancers with PTEN mutations or deletions, where mTOR signaling is often hyperactivated [

92]

Metadichol likely suppresses mTOR and P70S6K through multiple pathways in addition to KLF-mediated DDIT4 upregulation. Nuclear receptor-driven SIRT1 expression and TLR signaling modulation represent additional avenues for leveraging the metabolic (AMPK) and immune-metabolic (Akt) axes, respectively. Additionally, it affects circadian genes that regulate mTOR signaling. These mechanisms, which are potentially synergistic, highlight the versatility of metadichol while distinguishing it from conventional mTOR inhibitors. Future studies should prioritize the dissection of these pathways to clarify their contributions and therapeutic relevance.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The author is the founder and CEO of Nanorx Inc., NY, USA, and is a majority shareholder.

Funding Statement

The research and development budget of Nanorx, Inc., NY, USA, supported this study.

Availability of Data and Materials

Raw data are available upon request.

Abbreviations

| PBMC |

peripheral blood mononuclear cell |

| mTOR |

mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase |

| RPS6KB1 |

ribosomal protein S6 kinase B1 |

| DDIT4 |

DDNA damage inducible transcript 4 |

| Deptor |

DEP domain containing MTOR interacting protein |

| MLST8 |

MTOR associated protein, LST8 homolog |

| IGF1 |

Insulin like growth factor 1 |

| TSC1 |

TSC complex subunit 1 |

| TSC2 |

TSC complex subunit 2 |

| SIRTs |

Sirtuins |

| PPARa |

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha |

| TLRs |

Toll like receptors |

| IRAK4 |

interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase 4) |

| MYD88 |

MYD88 innate immune signal transduction adaptor |

| TRAF6 |

TNF receptor associated factor 6 |

| CLOCK |

clock circadian regulator |

| PER1 |

period circadian regulator 1 |

| CRY1 |

cryptochrome circadian regulator 1 |

| BMAL1 |

basic helix-loop-helix ARNT like 1 |

| AMPK |

AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AKT |

Protein kinase B |

| KLF |

Kupfer like factor |

| mTOC1 |

mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| mTORC2 |

mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 |

| NAD+ |

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| REDD1 |

regulated in development and DNA damage responses 1) |

| P13K |

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases, |

| AGC |

A: Protein Kinase A (PKA), also known as cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, which is activated by the secondary messenger cyclic AMP (cAMP).

G: Protein Kinase G (PKG), also known as cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase, which is activated by cyclic GMP (cGMP).

C: Protein Kinase C (PKC), a large family of kinases activated primarily by lipid signaling molecules such as diacylglycerol (DAG) and calcium ions.

|

| PROTOR1 |

Protein observed with Rictor-1 |

| PRAS40 |

Protein observed with Rictor-1 |

| GADPH |

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| VDR |

Vitamin D receptor |

References

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM., (2009) mTOR signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. Oct 15;122(Pt 20):3589-94. [CrossRef]

- Rohde J, Heitman J, Cardenas ME. The TOR kinases link nutrient sensing to cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2001 Mar 30;276(13):9583-6. [CrossRef]

- Castro AF, Rebhun JF, Clark GJ, Quilliam LA., (2003). Rheb binds tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) and promotes S6 kinase activation in a rapamycin- and farnesylation-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. Aug 29;278(35):32493-6. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Huang S., (2010) The complexes of mammalian target of rapamycin. Curr Protein Pept Sci. Sep;11(6):409-24. [CrossRef]

- Kim YC, Guan KL., (2015) mTOR: a pharmacologic target for autophagy regulation. J Clin Invest. Jan;125(1):25-32. Epub 2015 Jan 2. [CrossRef]

- Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, Blenis J., (2005) mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell. Nov 18;123(4):569-80. [CrossRef]

- Babchia N, Calipel A, Mouriaux F, Faussat AM, Mascarelli F.,(2010) The PI3K/Akt and mTOR/P70S6K signaling pathways in human uveal melanoma cells: interaction with B-Raf/ERK. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010 Jan;51(1):421-9. [CrossRef]

- Majeed, Sheikh Tahir et al., (2019) A Compelling Prospect for Therapeutic Interventions (2019). Chapter 8; S 6 Kinase : Chapter 8. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Iijima, Yoshihiro et al. (2002). c-Raf/MEK/ERK Pathway Controls Protein Kinase C-mediated p70S6K Activation in Adult Cardiac Muscle Cells*.The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277: 23065 - 23075. [CrossRef]

- Davies, Clare C. et al.(2004). Inhibition of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase- and ERK MAPK-regulated Protein Synthesis Reveals the Pro-apoptotic Properties of CD40 Ligation in Carcinoma Cells Journal of Biological Chemistry, Volume 279, Issue 2, 1010-1019. [CrossRef]

- Goberdhan DC, Wilson C, Harris AL., (2016). Amino Acid Sensing by mTORC1: Intracellular Transporters Mark the Spot. Cell Metab. Apr 12;23(4):580-9. [CrossRef]

- Lee CC, Huang CC, Hsu KS., (2011). Insulin promotes dendritic spine and synapse formation by the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Rac1 signaling pathways. Neuropharmacology. Sep;61(4):867-79. [CrossRef]

- Anwar V, Singh A, Bhatt M, Tonk RK, Azizov S, Raza AS, Sengupta S, Kumar D, Garg M., (2023). Multifaceted role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. Oct 2;8(1):375. [CrossRef]

- 14, Xu S, et al, (2016). miR-424(322) reverses chemoresistance via T-cell immune response activation by blocking the PD-L1 immune checkpoint. Nat Commun. May 5;7:11406. [CrossRef]

- Ferro A., (2016). Mechanistic target of rapamycin modulation: an emerging therapeutic approach in a wide variety of disease processes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 82(5):1156-1157. [CrossRef]

- Mabuchi S, et al (2009) . mTOR is a promising therapeutic target both in cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Clin Cancer Res. 15(17):5404-13. [CrossRef]

- Rui, Liangyou Fisher, Tracey L., Thomas, Jeffrey, and White, Morris F., (2001). Regulation of Insulin/Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Signaling by Proteasome-mediated Degradation of Insulin Receptor Substrate-2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (43), 40362-4036. [CrossRef]

- Kahan BD, Camardo JS. Rapamycin: clinical results and future opportunities. 2001. Transplantation. 72(7):1181-93. [CrossRef]

- Sumien N, Wells MS, Sidhu A, Wong JM, Forster MJ, Zheng QX, Kelleher-Andersson JA., (2012). Novel pharmacotherapy: NNI-362, an allosteric p70S6 kinase stimulator, reverses cognitive and neural regenerative deficits in models of aging and disease. Stem Cell Res Ther.13;12(1):59. [CrossRef]

- Meng Y, Yong Y, Yang G, Ding H, Fan Z, Tang Y, Luo J, Ke ZJ.,(2013). Autophagy alleviates neurodegeneration caused by mild impairment of oxidative metabolism. J Neurochem, Sep;126(6):805-18. [CrossRef]

- Davoody S, Asgari Taei A, Khodabakhsh P, Dargahi L.,(2024). mTOR signaling and Alzheimer's disease: What we know and where we are? CNS Neurosci Ther.30(4):e14463. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Z, et al,(2019). Balancing mTOR Signaling and Autophagy in the Treatment of Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci.20(3):728. [CrossRef]

- Nicolini C, Ahn Y, Michalski B, Rho JM, Fahnestock M.,(2015). Decreased mTOR signaling pathway in human idiopathic autism and in rats exposed to valproic acid. Acta Neuropathol Commun.Jan 20;3:3. [CrossRef]

- Uddin MS, Rahman MA, Kabir MT, Behl T, Mathew B, Perveen A, Barreto GE, Bin-Jumah MN, Abdel-Daim MM, Ashraf GM., ( 2020). Multifarious roles of mTOR signaling in cognitive aging and cerebrovascular dysfunction of Alzheimer's disease. IUBMB Life. Sep;72(9):1843-1855. [CrossRef]

- Karagianni F, Pavlidis A, Malakou LS, Piperi C, Papadavid E.,(2022). Predominant Role of mTOR Signaling in Skin Diseases with Therapeutic Potential. Int J Mol Sci. Feb 1;23(3):1693. [CrossRef]

- Jia G, Aroor AR, Martinez-Lemus LA, Sowers JR.,(2014). Overnutrition, mTOR signaling, and cardiovascular diseases. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. Nov 15;307(10):R1198-206. [CrossRef]

- Dolinsky VW, Chan AY, Robillard Frayne I, Light PE, Des Rosiers C, Dyck JR., (2009). Resveratrol prevents the prohypertrophic effects of oxidative stress on LKB1. Circulation. Mar 31;119(12):1643-52. [CrossRef]

- He L, Cho S, Blenis J., (2025). mTORC1, the maestro of cell metabolism and growth. Genes Dev. Jan 7;39(1-2):109-131. [CrossRef]

- Ellisen, L. W., Ramsayer, K. D., Johannessen, C. M., Yang, A., Beppu, H., Minda, K., ... & Haber, D. A. (2002). REDD1, a developmentally regulated transcriptional target of p63 and p53, links p63 to regulation of reactive oxygen species. Molecular Cell, 10(5), 995–1005. [CrossRef]

- Brugarolas, J., Lei, K., Hurley, R. L., Manning, B. D., Reiling, J. H., Hafen, E., ... & Kaelin, W. G. (2004). Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes & Development, 18(23), 2893–2904. [CrossRef]

- Sofer, A., Lei, K., Johannessen, C. M., & Ellisen, L. W. (2005). Regulation of mTOR and cell growth in response to energy stress by REDD1. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 25(14), 5834–5845. [CrossRef]

- Dufner, A., & Thomas, G. (1999). Ribosomal S6 kinase signaling and the control of translation. Experimental Cell Research, 253(1), 100–109. [CrossRef]

- Horak, P., Crawford, A. R., Vadysirisack, D. D., Nash, Z. M., DeYoung, M. P., Sgroi, D., & Ellisen, L. W. (2010). Negative feedback control of HIF-1 through REDD1-regulated ROS suppresses tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(10), 4675–4680. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Kubica, N., Ellisen, L. W., Jefferson, L. S., & Kimball, S. R. (2006). Glucocorticoid receptor signals inhibit mTOR via upregulation of REDD1. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 281(39), 28755–28761. [CrossRef]

- Ben Sahra, I, Regazzetti, C., Robert, G., Laurent, K., Le Marchand-Brustel, Y., Auberger, P., Bost, F. (2011). Metformin, independent of AMPK, inhibits mTORC1 in a REDD1-dependent manner. Cancer Research, 71(13), 4366–4375.

- Kaper, F., Dornhoefer, N., & Brugarolas, J. (2006). Hypoxia induces REDD1 expression via HIF-1α in a manner dependent on protein synthesis. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 26(14), 5621–5630.

- Zhou H, Luo Y, Huang S., (2010). Updates of mTOR inhibitors. Anticancer Agents Med Chem.Sep;10(7):571-81. [CrossRef]

- Dancey JE, (2006). Therapeutic targets: MTOR and related pathways. Cancer Biol Ther. Sep;5(9):1065-73. [CrossRef]

- Tse Y, Vasey N, Thomas R, Leech S, Owens S, Sayer J., (2025). How to use mTOR inhibitors in children. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. Feb 16:edpract-2024-327852. [CrossRef]

- Hille U, Soergel P, Makowski L, Dörk-Bousset T, Hillemanns P., (2012). Lymphedema of the breast as a symptom of internal diseases or side effect of mTor inhibitors. Lymphat Res Biol. Jun;10(2):63-73. [CrossRef]

- Shameem R, Lacouture M, Wu S., (2015). Incidence and risk of rash to mTOR inhibitors in cancer patients. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Oncol. Jan;54(1):124-32. [CrossRef]

- Chia S, Gandhi S, Joy AA, Edwards S, Gorr M, Hopkins S, Kondejewski J, Ayoub JP, Califaretti N, Rayson D, Dent SF., (2015). Novel agents and associated toxicities of inhibitors of the pi3k/Akt/mtor pathway for the treatment of breast cancer. Curr Oncol. Feb;22(1):33-48. [CrossRef]

- Schenone S, Brullo C, Musumeci F, Radi M, Botta M, (2011). ATP-competitive inhibitors of mTOR: an update. Curr Med Chem18(20):2995-3014. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Wang J, Liang Q, Tong R, Huang J, Yang X, Xu Y, Wang W, Sun M, Shi J. (2022). Recent progress on FAK inhibitors with dual targeting capabilities for cancer treatment. Biomed Pharmacother. Jul;151:113116. [CrossRef]

- Yuan R, Kay A, Berg WJ, Lebwohl D (2009). Targeting tumorigenesis: development and use of mTOR inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. Oct 27;2:45. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, et a;, (2023). Discovery of novel potent PI3K/mTOR dual-target inhibitors based on scaffold hopping: Design, synthesis, and antiproliferative activity. Arch Pharm (Weinheim). Dec;356(12):e2300403. [CrossRef]

- Hudes GR, (2009). Targeting mTOR in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. May 15;115(10 Suppl):2313-20. [CrossRef]

- Heng DY, Kollmannsberger C, Chi KN, (2019).. Targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: current treatment and future directions. Ther Adv Med Oncol. Jan;2(1):39-49. [CrossRef]

- Klawitter J, Nashan B, Christians U, (2015). Everolimus and sirolimus in transplantation-related but different. Expert Opin Drug Saf. Jul;14(7):1055-70. [CrossRef]

- De Fijter JW, (2017). Cancer and mTOR Inhibitors in Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. Jan;101(1):45-55. [CrossRef]

- P.R. Raghavan, Policosanol Nanoparticles, US patents 8,722,093 (2014) and 9,006,292 (2015).

- C. Aleman, et al (1994). A 12-month study of policosanol oral toxicity in Sprague Dawley rats, Toxicology Letters, vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 77–87. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Alemán et al., (1994). Carcinogenicity of policosanol in Sprague Dawley rats: a 24 month study, Teratogenesis, Carcinogenesis, and Mutagenesis, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 239–249. 84). [CrossRef]

- C. L. Alemán, et al. (1995). Carcinogenicity of policosanol in mice: an 18-month study, Food and Chemical Toxicology, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 573-578. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, P.R., (2025). Metadichol-Induced KLF Expression in PBMC Cells. Links SIRTs, NRs, TLRs, and circadian genes. A Systems-Wide Biology Approach. Preprints 2025020271. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Manning BD, (2008). The TSC1-TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J. Jun 1;412(2):179-90. [CrossRef]

- Laplante, M., & Sabatini, D. M. (2012). mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell, 149(2), 274–293. [CrossRef]

- Lo Surdo P, Iannuccelli M, Contino S, Castagnoli L, Licata L, Cesareni G, Perfetto L., (2022). SIGNOR 3.0, the SIGnaling network open resource 3.0: 2022 update. Nucleic Acids Res. Oct 16:gkac883. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavan, PR., (2024). Metadichol induced expression of Toll receptor family members in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Medical Research Archives, (online) 12(8).

- Raghavan PR., (2024). Metadichol®-Induced Expression of Sirtuin 1-7 In Somatic and Cancer Cells, Medical Research Archives (online), 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Chalkiadaki, A and Guarente, L. (2015). The multifaceted functions of sirtuins in metabolism. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 13(12), 698–707. [CrossRef]

- P.R. Raghavan, (2023). Metadichol®: A Nano Lipid Emulsion that Expresses All 49 Nuclear Receptors in Stem and Somatic Cells. Archives of Clinical and Biomedical Research. 7: 524-536. [CrossRef]

- Ruderman, N. B et al. (2010). AMPK and SIRT1: A long-standing partnership? American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 298(5), E751–E760. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Guan, K. L. (2015). mTOR as a central hub of nutrient signaling and cell growth. Nature Cell Biology, 21(1), 63–71. [CrossRef]

- Weichhart, T., Hengstschläger, M., & Linke, M. (2015). Regulation of innate immune cell function by mTOR. Nature Reviews Immunology, 15(10), 599–614. [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias AJ, Aksoylar HI, Horng T. (2015). Control of macrophage metabolism and activation by mTOR and Akt signaling. Semin Immunol. Aug;27(4):286-96. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. R., Wright, J., Bauter, M., Seweryniak, K., Kode, A., & Rahman, I. (2012). Sirtuin regulates cigarette smoke-induced proinflammatory mediator release via RelA/p65 NF-κB in macrophages. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology, 36(6), 685–692.

- Song Y, Wu Z, Zhao P. (2021). The protective effects of activating the Sirt1/NF-κB pathway for neurological disorders. Rev Neurosci. Nov 8;33(4):427-438. [CrossRef]

- Kiani P,et al. (2025). Autophagy and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor signaling pathway: A molecular ballet in lipid metabolism and homeostasis. Mol Cell Biochem. Feb 1. [CrossRef]

- P.R. Raghavan, (2024). Metadichol®-induced expression of circadian clock transcription factors in human fibroblasts. Medical Research Archives, (online) 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Maiese K, (2019). Impacting dementia and cognitive loss with innovative strategies: mechanistic target of rapamycin, clock genes, circular non-coding ribonucleic acids, and Rho/Rock. Neural Regen Res. May;14(5):773-774. [CrossRef]

- Maiese K, (2020) Cognitive impairment with diabetes mellitus and metabolic disease: innovative insights with the mechanistic target of rapamycin and circadian clock gene pathways. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 13(1):23-34. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto CS, et al (2016) . PI3K-PTEN dysregulation leads to mTOR-driven upregulation of the core clock gene BMAL1 in normal and malignant epithelial cells. Oncotarget. Jul 5;7(27):42393-42407. [CrossRef]

- Singla R, Mishra A, Cao R., (2022). The trilateral interactions between mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, the circadian clock, and psychiatric disorders: an emerging model. Transl Psychiatry. Aug 31;12(1):355. [CrossRef]

- Khapre RV,et al, (2014). Metabolic clock generates nutrient anticipation rhythms in mTOR signaling. Aging (Albany NY). Aug;6(8):675-89. [CrossRef]

- Crosby P,. et al (2019). Insulin/IGF-1 Drives PERIOD Synthesis to Entrain Circadian Rhythms with Feeding Time. Cell. May 2;177(4):896-909.e20. [CrossRef]

- Cao R, et al (2010) Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling modulates photic entrainment of the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. J Neurosci. May 5;30(18):6302-14. [CrossRef]

- Bellet, M. M., et al. (2011). Circadian clock and SIRT1: A reciprocal relationship. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 22(6), 211-216.

- Cao, R., et al. (2011). Circadian regulation of mTOR signaling. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 26(1), 22-30.

- Zhang, Q., et al. (2016). The vitamin D receptor inhibits mTOR signaling in cancer cells. Oncotarget, 7(12), 14186-14196.

- Oka, S., et al. (2011). The PPARα-SIRT1 complex suppresses mTOR signaling in cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation Research, 108(11), 1332-1341.

- Kim, K. H., et al. (2011). PPARγ mediates the hypoxic induction of REDD1. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 407(4), 693-698.

- Nakahata, Y., et al. (2008). The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 modulates CLOCK-mediated chromatin remodeling. Cell, 134(2), 329-340. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan PR., (2024). Metadichol®-Induced Expression of Sirtuin 1-7 In Somatic and Cancer Cells, Medical Research Archives, (online) 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Xie, W., Xie, W. et al, (2022). Beyond controlling cell size: functional analyses of S6K in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Dis 13, 646. [CrossRef]

- Panwar, V., Singh, A., Bhatt, M. et al, (2023). Multifaceted role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in human health and disease. Sig Transduct Target Ther 8, 375. [CrossRef]

- Son, B., Lee, W., Kim, H. et al, (2024). Targeted therapy of cancer stem cells: inhibition of mTOR in pre-clinical and clinical research. Cell Death Dis 15, 696. [CrossRef]

- Dhar R, Basu A., (2008). Constitutive activation of p70 S6 kinase is associated with intrinsic resistance to cisplatin. Int J Oncol.May;32(5):1133-7. [PubMed]

- Deng L, Qian G, Zhang S, Zheng H, Fan S, Lesinski GB, Owonikoko TK, Ramalingam SS, Sun SY., (2019). Inhibition of mTOR complex 1/p70 S6 kinase signaling elevates PD-L1 levels in human cancer cells through enhancing protein stabilization accompanied with enhanced β-TrCP degradation. Oncogene. Aug;38(35):6270-6282. [CrossRef]

- Tian T, Li X, Zhang J., (2019). mTOR Signaling in Cancer and mTOR Inhibitors in Solid Tumor Targeting Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Feb 11;20(3):755. [CrossRef]

- Marafie SK, Al-Mulla F, Abubaker J., (2024). mTOR: Its Critical Role in Metabolic Diseases, Cancer, and the Aging Process. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jun 2;25(11):6141. [CrossRef]

- Podsypanina K,. et al (20010. An inhibitor of mTOR reduces neoplasia and normalizes p70/S6 kinase activity in Pten+/- mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Aug 28;98(18):10320-5. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).