Introduction

More than forty years after the birth of the first baby conceived by in vitro fertilization (IVF) [

1], many challenges to improve IVF efficacy and safety still remain [

2]. In fact, the overall IVF success does not rise much above 30%, although the condition for embryo culture have improved [

3]. The success (childbirth) after IVF basically depends on two types of factors, those related to uterine receptivity and those given by embryo developmental potential [

4]. Embryo developmental potential has been addressed by a number of studies aimed at improving IVF efficiency. However, most of the initial studies used techniques incompatible with their use in the clinical IVF settings because of issues related to invasivity and subjectivity. Due to these limitations, and the need for fast, objective and noninvasive techniques to be incorporated into the decision-making scheme used in IVF centers, especially with regard to single-embryo transfer, new techniques based on computer-assisted processing of sequential static embryo images and molecular analysis of spent media from embryo culture were developed [

5]. This paper reviews the history, state of the art, strengths and limitations of noninvasive embryo-quality biomarkers currently available for use in IVF laboratories.

2. Noninvasive Biomarkers: History, Current State, Strengths and Limitations

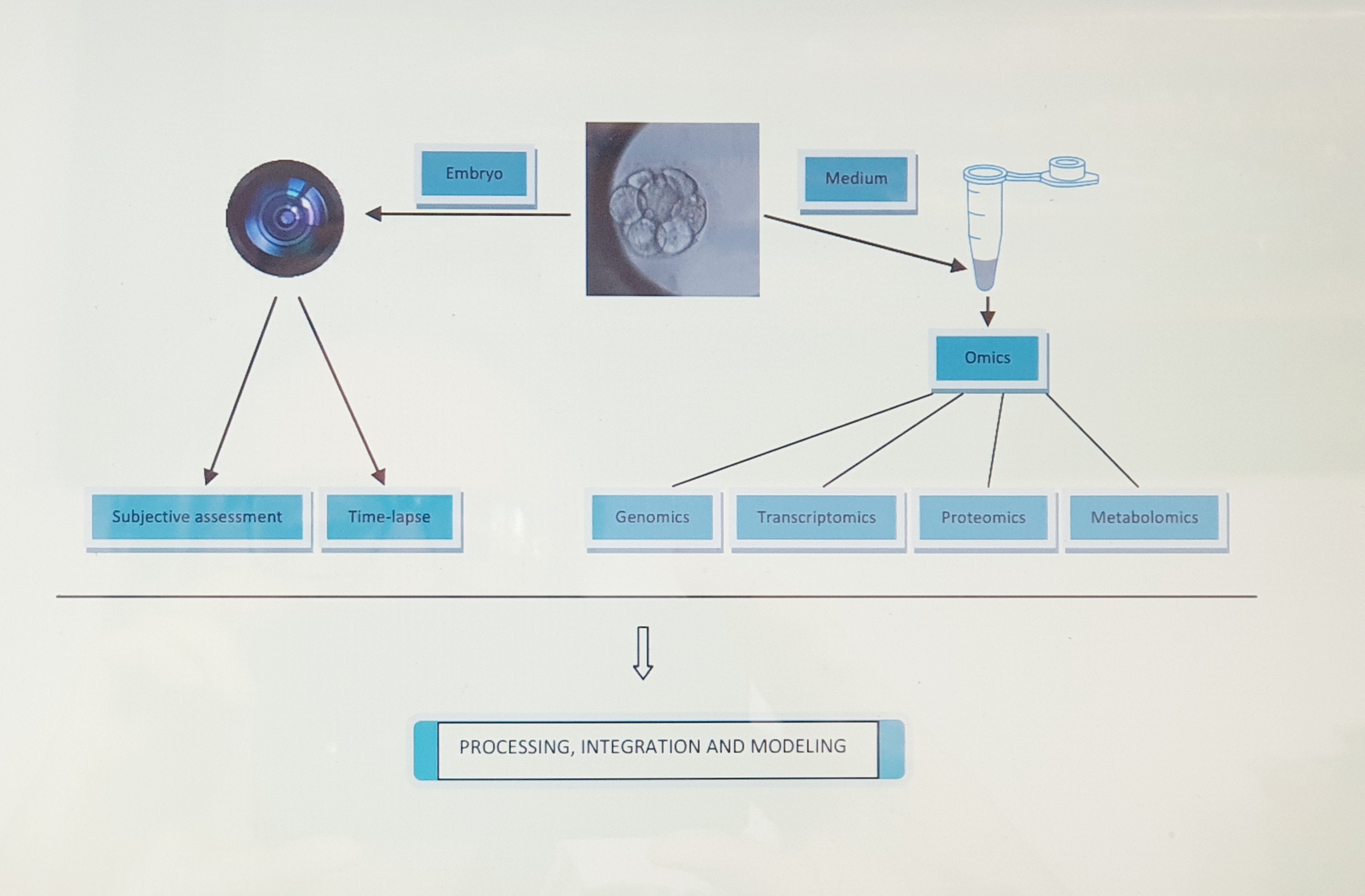

Repeated observations of zygote and embryo morphology at different time points after fertilization are the source of the most available noninvasive biomarkers serving for the prediction of embryo developmental potential. To improve the predictive power of embryo morphology, the use of recordings displaying changes continuously over time (kinetics) was adapted later. Experience showing that, in many cases, such morphology-based approaches cannot detect functional deficiencies, such as chromosomal abnormalities and issues related to gene expression or metabolic activity, was at the origin of research into the suitability of spent media from embryo culture as a source of information. This eventually led to the development of a variety of noninvasive “omics” methods, based on the evaluation of embryo ploidy status (genomics), gene transcription (transcriptomics) and translation (proteomics and secretomics), and the metabolism of different substrates (metabolomics), that are currently available for embryo grading. The history, current status, and strengths and limitations of each category of noninvasive biomarkers are detailed below.

2.1. Morphology and Kinetics

History

From the very beginning of human in vitro fertilization (IVF), there have been attempts at using static images of the zygote and the embryo at successive stages of preimplantation development as the basis for quality assessment of individual embryos with regard to their presumed developmental potential [

6,

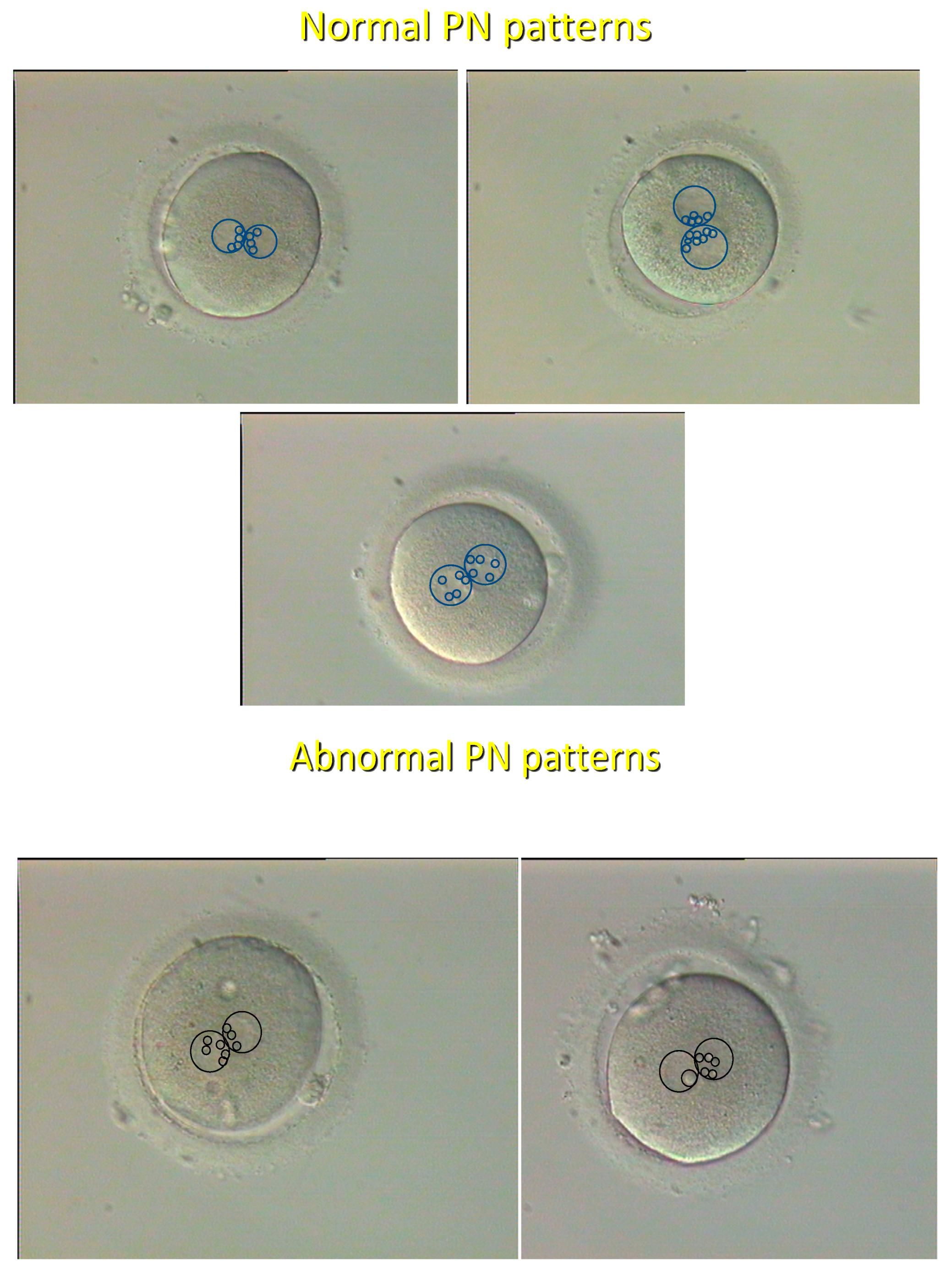

7]. Zygotes were graded based on the distribution of nucleolar precursor bodies (NPBs) in both pronuclei (PN) at the time of pronuclear apposition [

8], and it was shown that the “pronuclear pattern” (

Figure 1) has a high predictive value as to further embryo development and chromosomal status [

9]. As to cleaving embryos, they were assessed by the number and symmetry of blastomeres, the grade of fragmentation, the eventual presence of multinucleated blastomeres and the compaction status [

10], while blastocysts were scored according to the degree of blastocoel expansion and the definition of the first two cell lineages, the inner cell mass and the trophectoderm [

11]. However, in spite of some encouraging reports, morphological grading of cleaving embryos and blastocysts was shown to exhibit a poor correlation with the success of IVF [

12], probably related to subjectivity due to intra- and interobserver variability [

13].

In order to eliminate the subjectivity bias, systems based on automated assessment of embryo morphology over time, with the use of time-lapse technology and morphokinetic algorithms employed for time-lapse data interpretation, were introduced into IVF technology during the first decade of this century [

14].

Current Status

Several markers of embryonic kinetics were reviewed recently, and some of them were applied in decisional algorithms for embryo transfer [

15]. Out of 35 morphometric, morphologic and morphokinetic variables, only the location of PN at the time of pronuclear juxtaposition and the absence of multinucleated blastomeres (MNB) at the 2-cell stage were linked to live birth rate. In concrete terms, central pronuclear juxtaposition was associated with a two-fold increase in the odds of livebirth (OR = 2.20; 95% CI, [1.26-3.89];

P = 0.006), while the presence of MNB was linked to half the odds of livebirth (OR = 0.51; 95% CI, [0.27–0.95];

P = 0.035), and these two parameters were independent of embryo kinetics [

15]. Morphological criteria were also applied to frozen-thawed blastocysts, and it was shown that blastocyst re-expansion rate immediately (9-11 minutes) after warming, assessed with the use of image-analysis software, is a strong dynamic indicator of embryo quality [

16].

Recently it was attempted to enhance the predictive power of criteria based on static morphologic evaluation of embryo images by using artificial intelligence (machine learning) to create virtual 3D images from time-lapse recordings (time-lapse 3D holotomography), and impressive performance metrics with regard to blastocyst development were reported [

17]. However, a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) failed to detect any significant difference in a multicenter, randomized, double-blind noninferiority parallel-group trial, conducted across 14 IVF clinics in Europe and Australia and assessing the value of deep learning in selecting the optimal embryo for transfer, was not able to demonstrate noninferiority of deep learning for clinical pregnancy rate when compared to standard morphology evaluation [

18], and this conclusion was confirmed by another independent RCT [

19]. Consequently, despite being promising, the time-lapse technology still needs to be improved, possibly by incorporating pronuclear morphology scoring previously shown to have a high predictive potential for futher embryo development, embryo ploidy and IVF outcome [

8,

9].

Even so, time-lapse is evidently more rapid and embryo-friendly than the observer-operated grading, since it avoids prolonged period of stay of embryos outside the incubator. Hopefully, the incorporation of the PN pattern (Figure 1) to time-lapse softwares will increase the impact of this technology in the near future.

Table 1.

Overview of the most important information concerning biomarkers based on embryo morphology and kinetics. Abbreviations: MNB = multinucleated blastomeres; 3D = three-dimensional.

Table 1.

Overview of the most important information concerning biomarkers based on embryo morphology and kinetics. Abbreviations: MNB = multinucleated blastomeres; 3D = three-dimensional.

| Marker |

Reference outcome |

Predictive capacity |

Techniques |

References |

| Pronuclear |

Ongoing development |

Very high |

Single microscopic |

8 |

| Morphology |

Chromosomal ploidy |

Very high |

observation |

9 |

| Cleavage speed and regularity |

Pregnancy |

Low |

Repeated microscopic observation |

11-13 |

| Proportion of MNB |

Developmental arrest and pregnancy failure |

High |

Repeated microscopic observation |

10 |

| Noninvasive continuous recording |

Developmental arrest and pregnancy failure |

Debated

High with 3D setting

(holotomography) |

Time lapse photography |

14-19 |

| Chromosomal ploidy |

High |

20-22 |

Beyond embryo viability assessment in general, another recent study [

20] reports the development of an efficient artificial intelligence model that can predict embryo ploidy status from time-lapse recordings, showing an accuracy of 0.74, an aneuploid precision of 0.83, and an aneuploid predictive value (recall) of 0.84 [

21]. Moreover, relevant information can be obtained by time-lapse analysis of embryos as early as the beginning of the first cleavage division [

22].

Strengths and Limitations

Unlike some other noninvasive biomarkers of embryo quality (see below), those based on morphology and kinetics can be applied to embryos from the very early stages, including the one-cell zygote. Good correlations with further embryo development and clinical IVF outcomes were reported in early observational studies. Evaluation using time-lapse technology eliminates the bias of subjectivity and is faster and more embryo-friendly, but its superiority over the classical observer-operated grading systems has not been confirmed by the only two RCTs published so far. Morphological grading does not require costly equipment when realized in an observer-operated manner. For generation and processing of time-lapse images, the purchase of more expensive equipment is needed.

2.2. Chromosomal Ploidy Status (Genomics)

History

Aneuploidy is a well-known condition underlying implantation failure, miscarriage and abortion. It mainly arises from meiotic errors in oocytes, closely related to maternal age [

23], although it can also be caused by mitotic errors during the early cleavage divisions [

24]. In the former situation, individual embryonic cells exhibit a uniform aneuploidy pattern [

25], while chromosomally mosaic embryos, containing both euploid and aneuploid cells, result from the latter [

26]. To cope with the aneuploidy issue, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies (PGT-A) has been adopted in IVF practice from the early 1990s [

27].

PGT-A was first used by analyzing cells of abnormally developing embryos by fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) with specific probes for a limited number of chromosomes. Five chromosomes most involved in human aneuploidy (X, Y, 18, 13 and 21) were assessed in the original study [

27]. In order to maintain the viability of the tested embryo, trophectoderm biopsy, a micromanipulation technique whereby a small group of cells are extracted from blastocyst trophectoderm [

28], was subsequently used for PGT-A in the clinical IVF setting. To extend PGT-A to more or all chromosomes, FISH was progressively substituted with still more effective techniques, such as

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) and next generation sequencing (NGS), and trophectoderm biopsy techniques were also refined [

29]

. However, recent findings challenged both the reliability and the harmlessness of PGT-A using trophectoderm biopsy, even with the use of the most advanced molecular techniques, putting the PGT-A in its traditional form into question. Most criticisms concerned the representativity of randomly sampled trophectoderm cells as to the chromosomal status in cells of the inner cell mass, potential harm trophectoderm biopsy may cause to the embryo and the issue of mosaic embryos.

Table 2.

Overview of the most important information concerning biomarkers based on embryo chromosomal ploidy. Abbreviations: PGT-A, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy; NICS, noninvasive chromosome screening; niPGT-A, noninvasive PGT-A; RCTs, randomized controlled trials, FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridization; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CGH, comparative genome hybridization; NGS, next generation sequencing; WGA, whole genome amplification.

Table 2.

Overview of the most important information concerning biomarkers based on embryo chromosomal ploidy. Abbreviations: PGT-A, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy; NICS, noninvasive chromosome screening; niPGT-A, noninvasive PGT-A; RCTs, randomized controlled trials, FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridization; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CGH, comparative genome hybridization; NGS, next generation sequencing; WGA, whole genome amplification.

| Marker |

Reference outcome |

Predictive capacity |

Techniques |

References |

| PGT-A |

Whole embryo ploidy and pregnancy |

Intermediate and questionable |

FISH, PCR, CGH, NGS |

27-33 |

| NICS (niPGT-A) |

Whole embryo ploidy and pregnancy |

Very high but needing confirmation by RCTs |

NGS after WGA |

34-38 |

Trophectoderm cells contribute to the placenta, while cells of the future embryonic and fetal body stem from the inner cell mass.

This creates a probability that the biopsied cells will not hold genetic material that represents the embryo’s genetic material [

30]

. Harmful effects of trophectoderm biopsy on embryo developmental potential were reported [

31]

, and this micromanipulation might also increase the incidence of mosaic blastocysts [

32]

. Finally, with the use of trophectoderm cells, the PGT-A result is poorly predictive of the absolute level of mosaicism of a single embryo as demonstrated with the use of computational modelling [

33]

.

To overcome the above problems, alternative methods for embryo ploidy assessment were searched for, resulting in the development of noninvasive chromosome screening (NICS) [

34]. NICS makes use of NGS after

multiple annealing and looping-based amplification cycles (MALBAC) for whole-genome amplification (WGA) [

34]

and is highly recommended for embryo ploidy assessment.

Current Status

NICS, also referred to as noninvasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (niPGT-A) was reported to exhibit 100% sensitivity, 87.5% specificity, 88.9% positive predictive value (PPV), 100% negative predictive value (NPV), 12.5% false-positive rate (FPR), and 0% false-negative rate (FNR), comparing favorably to classical PGT-A in terms of ploidy diagnostic accuracy [

35]. Lately, niPGT-A was successfully used in a single-embryo transfer setting to select euploid embryos in patients carrying balanced chromosomal rearrangements by using genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping and haplotyping approach [

36], and algorithms for minimizing the impact of media contamination with maternal DNA were developed and validated [

37]

. In spite of these encouraging findings, the classical PGT-A using surplus IVF embryos donated for research still remains a gold standard for validation of new noninvasive biomarkers. In parallel to PGT-A and niPGT-A, there is growing interest in using morphokinetic embryo analysis (see section 2.1. of this article), alone or in combination with other embryonic and patient parameters, to replace both of them. Notably, the development of a noninvasive artificial intelligence approach for the prediction of human blastocyst ploidy, based on embryo morphology, morphokinetics and associated clinical information, was reported recently [

38].

Strengths and Limitations

Both traditional PGT-A and niPGT-A can provide information on embryo developmental potential and thus help select the best embryo for elective transfer. However, traditional PGT-A is burdened with errors due to interpretability of findings obtained with a few trophectoderm cells for the whole embryo, while more RCTs are still needed to establish niPGT-A as the preferential method. Results can be obtained faster with niPGT-A than with PGT-A, but both approaches require expensive equipment and skilled staff. Indirect evaluation methods based on synthesis of morphological and morphokinetic data, sometimes also including clinical data of the patients, may be the best solution in the future.

2.3. Gene Activity

Initial stages (at least the first two cell cycles) of human embryo development rely almost completely on molecules (maternal mRNA and proteins) stored in the oocyte, and oocyte-derived message continues to be used for some time even after the beginning of embryonic gene activity [

39]. Major embryonic gene activation occurs between the 4-cell and the 8-cell stage of development, later that in most laboratory animal species [

40], even though low levels of gene expression can be detected as early as the one-cell stage [

41,

42,

43]. Anyway, products of the minute gene activity before the human embryo achieves the four-cell stage can hardly be expected to be detectable in spent embryo-culture media. The major activation of RNA synthesis (transcription) and protein synthesis on newly synthesized embryonic RNA templates (translation) are milestones in embryo development, and underlie the possibility of using transcriptomics, proteomics and secretomics in the search for specific biomarkers to distinguish between embryos that have accomplished these developmental event and those that have not.

2.3.1. Transcription (Transcriptomics)

History

After a a near-silent period, a major transcriptional activation was detected in human embryos at the 4-cell stage [

44]. The fact that this event only occurs in morphologically normal blastomeres and is severely disturbed in abnormal (such as multinucleated) ones [

45], and some of the RNA species synthesized by healthy blastomeres are secreted into, and stable in, embryo culture media, attempts were made to use specific embryo-secreted RNAs or combinations thereof as embryo quality markers [

46,

47,

48]. There is a great variety of RNA types, differing from each other by size, main site of intracellular localization, and function. Special attention has been paid to non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) which represent as much as 98% of the transcriptome, and some types of them, mainly microRNAs (miRNAs) and

piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), were shown to be related to embryo viability and developmental potential [

46,

47,

48].

MiRNAs are composed of 18-24 nucleotides and act as gene expression modulators through translational inhibition or degradation of messenger RNAs (mRNA) [

49]. They were suggested to regulate adhesion of the blastocyst to the endometrium at the outset of implantation [

50]. For 10 years,

microRNAs, secreted from human blastocysts into culture media, have been considered potential biomarkers for noninvasive embryo selection [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]

and for predicting the risk of biochemical pregnancy loss after embryo transfer [

55]

. The other group of snRNAs, piRNAs, are involved in gene epression regulation and genome protection from instability and were also suggested as embryo biomarkers [

46]

.

Current Status

A recent study [

46], using massive-parallel sequencing on the Illumina sequencing platform and the BioMAI Pipeline Predictor Model, specifically identified two miRNAs (miR-16-5p and miR-92a-3p) and five piRNAs (piR-28263, piR-18682, piR-23020, piR-414, piR-27485) that prognostically and predictively distinguished a high-quality embryo suitable for IVF transmission from a low-quality embryo with 95% sensitivity, 100% specificity and 86% accuracy.

In another study analyzing spent culture medium of day 3 and day 5 embryos and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) [

56], three miRNAs, including hsa-miR-199a-5p, hsa-miR-483-5p, and hsa-miR-432-5p, were shown to be correlated with pregnancy and proposed as biomarkers for embryo quality during IVF cycles.

Strengths and Limitations

Embryo evaluation employing a panel of ncRNA markers with the use of qRT-PCR techniques is rapid and highly sensitive and thus advantageous for fast embryo assessment in clinical IVF practice. On the other hand, it requires appropriately skilled staff and relatively expensive equipment.

Table 3.

Overview of the most important information concerning biomarkers based on embryo gene activity. Abbreviations: miRNAs, microRNAs; piRNAs, piwi-interacting RNAs; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Table 3.

Overview of the most important information concerning biomarkers based on embryo gene activity. Abbreviations: miRNAs, microRNAs; piRNAs, piwi-interacting RNAs; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

| Marker |

Reference outcome |

Predictive capacity |

Techniques |

References |

Transcriptome

miRNAs

piRNAs

|

Embryo viability and pregnancy |

Very high |

Massive-parallel sequencing,

qRT-PCR |

46-56 |

| Proteome |

Embryo viability, ploidy and pregnancy |

Very high |

Historical: ELISA, Western blotting |

57 |

| Current: Mass spectrometry |

59-66 |

2.3.2. Translation (Proteomics and Secretomics)

History

A major activation of gene translation was detected in human embryos at the 8-cell stage [

57]. At the same stage, the first morphological signs of embryonic gene expression were found with the use of quantitative ultrastructural analysis [

58]. The proteome represents all proteins translated from specific gene expression products of a cell at a specific time, while the secretome refers to the proteins produced and secreted by the developing embryo. [

5].

Current Status

Both proteins secreted into the media (increasing trend) and those already present and taken up by the embryo (decreasing trend) can be valuable biomarkers of embryo development [

59]. Relatively simple techniques, such as ELISA and Western blotting, can be used to assess proteomics of spent embryo culture media. However, the use of high-throughput methodologies, such as mass spectrometry, eventually enhanced by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time od Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-ToF MS) [

60], can be envisaged so as to make the analysis faster and more sensitive. By using MALDI-ToF MS to compare euploid and aneuploid embryos (tested by PGT-A) it was possible to chacterize 12 unique spectral regions for euploid embryos and 17 for aneuploid ones [

61], and the technique has shown a high positive predictive value for ongoing pregnancy (82.9%,

p = 0.0018) after single embryo transfer [

62].

Individual specific markers of interest include human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) isoforms [

63], interleukin (IL) 6, stem cell factor (SCF) and interferon (IFN) α2 [

64], along with soluble human leukocyte antigen G (sHLA-G) [

65] and soluble cluster of differentiation 146 (sCD146) [

66], the latter being correlated with IVF success negatively. Moreover, other 18 exclusively expressed proteins were identified in the positive implantation group and 11 in the negative embryo implantation group [

66].

Strengths and Limitations

Current noninvasive techniques available for embryonic proteome and secretome assessment require as low as 1 μL of the sample volume, do not require the acquisition of special skills by the clinical laboratory staff and represent ultra-fast tools for embryo seletion immediately prior to uterine transfer. On the other hand, a general agreement on which technique/marker is preferrable still remains to be reached, results can be influenced by the composition of embryo culture media and thus difficult to extrapolate from one laboratory setting to another, and the purchase of relatively expensive equipment is required.

2.4. Substrate Uptake and Secretion (Metabolomics)

History

It has been known for many years that mammalian embryos display a rapid qualitative change in their metabolic activity at a certain point of preimplantation development. This was first described for energy metabolism. In fact, both mouse [

67] and human [

68] embryos switch from pyruvate to glucose as predominant energy source between compaction and blastulation, a period just after the major embryonic gene activation in humans (see section 2.3. of this article). This switch is underlain by carbohydrate metabolism passing from the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to glycolysis [

69]. In addition, patterns of the consumption and secretion of amino acids was also found to change in this period [

70]. Based on these observations, depletion/appearance of components like carbohydrates in spent media from cleavage-stage embryo culture was suggested as a source of noninvasive markers of embryo developmental potential [

71.] In earlier studies, data were generated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), microfluorescence, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). At present, embryo metabolomics assessment preferentially employs spectroscopy techniques that use energy changes to study the local environment of atoms, such as Raman, near-infrared (NIR), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopies [

72].

Table 4.

Overview of the most important information concerning biomarkers based on embryo metabolome. Abbreviations: NIR, near-infrared; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; TLC, thin-layer chromatography; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Table 4.

Overview of the most important information concerning biomarkers based on embryo metabolome. Abbreviations: NIR, near-infrared; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; TLC, thin-layer chromatography; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

| Marker |

Reference outcome |

Predictive capacity |

Techniques |

References |

| Carbohydrate profile |

Embryo viability and pregnancy |

Doubtful for NIR and NMR spectroscopies |

Historical: TLC, ELISA

Current: Raman, NIR

or NMR spectroscopies |

70-77 |

| Amino acid profile |

Embryo viability and pregnancy |

High for Raman spectroscopy |

Current Status

When used in combination with morphology, Raman spectroscopy of day 3 embryo culture media gave promising results as to predicting embryo implantation potential [

73]. More recently a model based on Raman spectroscopy approach was reported to have a specificity and sensitivity of 80.25% and 87.50%, respectively, by receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis [

74]. On the other hand, a double blind RCT evaluating embryo selection by metabolomic profiling of day 3 embryo culture media by NIR plus morphology failed to detect a superior prediction power of this method as compared to morphology alone [

75]. A similar conclusion was reported for NMR [

76]. However, a recent study showed that Raman spectroscopy can achieve an accuracy rate of 71.5%, by combining several machine learning methods, and detected significant differences in tyrosine, tryptophan, and serine between spent media after culture of day 3 embryos that gave a pregnancy after transfer and those that did not [

77].

Strengths and Limitations

Currently available techniques are fast and do not require special skills of clinical laboratory personnel. However, due to differences in assay methods, sample size, sample collection, and statistical analysis methods, no single metabolomic assay has yet been accepted for clinical use worldwide.

2.5. Combined Use of Different Biomarkers

As already marginally mentioned in section 2 of this article, interesting data were obtained by combining data obtained by different biomarkers and integrating them into embryo development predicting algorithms [

78], and a model of the bioinformatics pipeline of artificial intelligence and machine learning, combining non invasive biomarker data with sperm parameters, ovarian reserve, ovarian stimulation, uterine evaluation, patient genetics and patient demographics, was suggested [

46]. A human embryo model integrating embryo single-cell RNA sequencing dataset covering development from the zygote to the gastrula was developed recently [

79]. However, another recent report reveals that inflated expectations of new technologies, namely artificial intelligence-assisted embryo selection in IVF, are not justified by facts [

80]. Therefore, while acknowledging the possibilities offered by such novel approaches, this is not the time to adopt too an enthusiastic expectancy.

3. Conclusions

Based on previous findings regarding morphology and kinetics, chromosomal status, gene activity and metabolism of human preimplantation embryos, a number of distinct features, or combination thereof, were defined as potential noninvasive biomarkers of embryo developmental potential. As to morphology and kinetics, different extensions of the time-lapse imaging technology were assessed. As to the rest, a number of “omics” methods were designed. They include genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics, reflecting embryo chromosomal ploidy status, transcription, translation and metabolic activity, respectively. While no single method/marker has yet been accepted universally, this article reviews the current status, strengths and limitations of each one of them so as to guide IVF centers in their choice of the most suitable method(s) with regard to their specific needs.

Author Contributions

J.T. is the only author of this article.

Funding

No funding was received for this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Steptoe, P.C.; Edwards, R.G. Birth after reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet. 1978, 2(8085):366. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J. Assisted reproduction: new challenges and future prospects. In 40 Years After In Vitro Fertilisation; Tesarik, J., Ed.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2019; pp. 269-286.

- Bashiri, A.; Halper, K.I.; Orvieto, R. Recurrent implantation failure-update overview on etiology, diagnosis, treatment and future directions. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018, 16(1):121. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J. Complementarity between early embryogenesis and uterine receptivity: Toward integrative approach to female infertility management. Editorial to the Special Issue "Molecular Mechanisms of Human Oogenesis and Early Embryogenesis". Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(2):1557. [CrossRef]

- Rødgaard, T.; Heegaard, P.M,.; Callesen, H. Non-invasive assessment of in-vitro embryo quality to improve transfer success. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015, 31(5):585-592. [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J.M.; Breen, T.M.; Harrison, K.L.; Shaw, J.M.; Wilson, L.M.; Hennessey, J.F. A formula for scoring human embryo growth rates in in vitro fertilization: its value in predicting pregnancy and in comparison with visual estimates of embryo quality. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1986, 3(5):284-295. [CrossRef]

- Racowsky, C.; Vernon, M.; Mayer, J.; Ball, G.D.; Behr, B.; Pomeroy, K.O.; Wininger, D.; Gibbons, W.; Conaghan, J.; Stern. J.E. Standardization of grading embryo morphology. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010, 27(8):437-439. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Greco, E. The probability of abnormal preimplantation development can be predicted by a single static observation on pronuclear stage morphology. Hum Reprod. 1999, 14(5):1318-1323. [CrossRef]

- Balaban, B.; Yakin, K.; Urman, B.; Isiklar, A.; Tesarik, J. Pronuclear morphology predicts embryo development and chromosome constitution. Reprod Biomed Online. 2004, 8(6):695-700. [CrossRef]

- Prados, F.J.; Debrock, S.; Lemmen, J.G.; Agerholm, I. The cleavage stage embryo. Hum Reprod. 2012, 27 Suppl 1:i50-i71. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.K..; Lane, M.; Stevens, J.; Schlenker, T.; Schoolcraft, W.B. Blastocyst score affects implantation and pregnancy outcome: towards a single blastocyst transfer. Fertil Steril. 2000, 73(6):1155-1158. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, G.; Majumdar, A.; Verma, I.C.; Upadhyaya, K.C. Relationship Between Morphology, Euploidy and Implantation Potential of Cleavage and Blastocyst Stage Embryos. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2017, 10(1):49-57.

- Paternot, G.; Wetzels, A.M.; Thonon, F.; Vansteenbrugge, A.; Willemen, D.; Devroe, J.; Debrock, S.; D'Hooghe, T.M.; Spiessens, C. Intra- and interobserver analysis in the morphological assessment of early stage embryos during an IVF procedure: a multicentre study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011, 9:127. [CrossRef]

- Lemmen, J.G.; Agerholm, I.; Ziebe, S. Kinetic markers of human embryo quality using time-lapse recordings of IVF/ICSI-fertilized oocytes. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008, 17(3):385-391. [CrossRef]

- Barberet, J.; Bruno, C.; Valot, E.; Antunes-Nunes, C.; Jonval, L.; Chammas, J.; Choux, C.; Ginod, P.; Sagot, P.; Soudry-Faure, A.; Fauque, P. Can novel early non-invasive biomarkers of embryo quality be identified with time-lapse imaging to predict live birth? Hum Reprod. 2019, 34(8):1439-1449. [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, M.; Ito, A.; Katagiri, Y.; Oigawa, S.; Nagao, K.; Nakata, M. Blastocyst re-expansion rate immediately after warming is a strong dynamic indicator of embryo quality. Reprod Biomed Online. 2025,doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2025.104989.

- Lee, C.; Kim, G.; Shin, C.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, K.H.; Do, J.; Park, J.; Do, J.; Kim, J.H.; Park Y.K. Noninvasive time-lapse 3D subcellular analysis of embryo development for machine learning-enabled prediction of blastocyst formation. Preprint published at bioRxiv 2024.05.07.592317. [CrossRef]

- Illingworth, P.J.; Venetis, C.; Gardner, D.K.; Nelson, S.M.; Berntsen, J.; Larman, M.G.; Agresta, F.; Ahitan, S.; Ahlström, A.; Cattrall, F.; Cooke, S.; Demmers, K.; Gabrielsen, A.; Hindkjær, J.; Kelley, R.L.; Knight, C.; Lee, L.; Lahoud, R.; Mangat, M.; Park, H.; Price, A.; Trew, G.; Troest, B.; Vincent, A.; Wennerström, S.; Zujovic, L.; Hardarson, T. Deep learning versus manual morphology-based embryo selection in IVF: a randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial. Nat Med. 2024, 30(11):3114-3120. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, G.C.; Mozes, H.; Ronn, R.; Elder-Geva, T.; Schonberger, O.; Ben-Ami, I.; Srebnik, N. Time-Lapse Incubation for Embryo Culture-Morphokinetics and Environmental Stability May Not Be Enough: Results from a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1701. [CrossRef]

- Danardono, G.B.; Handayani, N.; Louis, C.M.; Polim, A.A.; Sirait, B.; Periastiningrum, G.; Afadlal, S.; Boediono, A.; Sini, I. Embryo ploidy status classification through computer-assisted morphology assessment. AJOG Glob Rep. 2023, 3(3):100209. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S., Brendel, M., Barnes, J.; Zhan, Q.; Malmsten, J.E.; Zisimopoulos, P.; Sigaras, A.; Ofori-Atta, K.; Meseguer, M.; Miller, K.A.; Hoffman, D.; Rosenwaks, Z.; Elemento, O.; Zaninovic, N.; Hajirasouliha, I. Automatic ploidy prediction and quality assessment of human blastocysts using time-lapse imaging. Nat Commun 15, 7756 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Novillo, C.; Uroz, L.; Márquez, C. Novel time-lapse parameters correlate with embryo ploidy and suggest an improvement in non-invasive embryo selection. J Clin Med. 2023, 12(8):2983. [CrossRef]

- Hassold, T.; Hunt, P. (2001) To ERR (meiotically) is human: The genesis of human aneuploidy. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2001, 2:280-291. [CrossRef]

- Leem, J.; Gowett, M.; Bolarinwa, S.; Mogessie, B. On the origin of mitosis-derived human embryo aneuploidy. Nat Commun. 2024, 15:10391. [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, S.I.; Hassold, T.J.; Hunt, P.A. Human aneuploidy: mechanisms and new insights into an age-old problem. Nat Rev Genet. 2012, 13(7):493-504. [CrossRef]

- McCoy, R.C. Mosaicism in preimplantation human embryos: When chromosomal abnormalities are the norm. Trends Genet. 2017, 33(7):448-463. [CrossRef]

- Munné, S.; Lee, A.; Rosenwaks, Z.; Grifo, J.; Cohen, J. Diagnosis of major chromosome aneuploidies in human preimplantation embryos. Hum Reprod. 1993, 8(12):2185-2191. [CrossRef]

- Dokras, A.; Sargent, I.L.; Ross, C.; Gardner, R.L.; Barlow, D.H. Trophectoderm biopsy in human blastocysts. Hum Reprod. 1990, 5(7):821-825. [CrossRef]

- Burks, C.; Van Heertum, K.; Weinerman, R. The technological advances in embryo selection and genetic testing: A look back at the evolution of aneuploidy screening and the prospects of non-invasive PGT. Reprod. Med. 2021, 2:26-34. [CrossRef]

- Bellver, J.; Bosch, E.; Espinós, J.J.; Fabregues, F.; Fontes, J.; García-Velasco, J.; Llácer, J.; Requena, A.; Checa, M.A; Spanish Infertility SWOT Group (SISG). Second-generation preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy in assisted reproduction: a SWOT analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019, 39(6):905-915. [CrossRef]

- Cimadomo, D.; Capalbo, A.; Ubaldi, F.M.; Scarica, C.; Palagiano, A.; Canipari, R.; Rienzi, L. The impact of biopsy on human embryo developmental potential during preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Biomed Res Int. 2016, 2016:7193075. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S., Liu, W., Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhu, J.; Hao, X.; Li, J.; Liu, D.; Han, W.; Huang, G. Trophectoderm biopsy protocols may impact the rate of mosaic blastocysts in cycles with pre-implantation genetic testing for aneuploidy. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021, 38:1153–1162. [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B.M.; Viotti, M.; International Registry of Mosaic Embryo Transfers (IRMET); Griffin, G.K.; Ellis, P.J.I. Explaining the counter-intuitive effectiveness of trophectoderm biopsy for PGT-A using computational modelling. eLife. 2024, 13:RP94506. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Fang, R.; Chen, L.; Chen, D.; Xiao, J.P.; Yang, W.; Wang, H.; Song, X.; Ma, T.; Bo, S; Shi, C.; Ren, J.; Huang, L.; Cai, L.Y.; Yao, B.; Xie, X.S.; Lu, S. Noninvasive chromosome screening of human embryos by genome sequencing of embryo culture medium for in vitro fertilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016, 113(42):11907-11912. [CrossRef]

- Shitara, A.; Takahashi, K.; Goto, M.; Takahashi, H.; Iwasawa, T.; Onodera, Y.; Makino, K.; Miura, H.; Shirasawa, H.; Sato, W.; Kumazawa, Y.; Terada, Y. Cell-free DNA in spent culture medium effectively reflects the chromosomal status of embryos following culturing beyond implantation compared to trophectoderm biopsy. PLoS One. 2021, 16(2):e0246438. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Tan, J.; Liang, B.; Gao, M.; Wu, J.; Ling, X.; Liu, J.; Teng, X.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Huang, W.; Tong, X.; Lei, C.; Li, H.; Wang, J., Li, S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Liang, S.; Ou, J.; Zhao, Q.; Jin, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Lu, D.; Yan, J., Sun, X.; Choy, K.W.; Xu, C.; Chen, Z.J. Preimplantation genetic testing for structural rearrangements by genome-wide SNP genotyping and haplotype analysis: a prospective multicenter clinical study. EBioMedicine. 2025, 111:105514. [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Yao, Y.; Zou, Y.; lv, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, D.; Lu, S.; Yang, W.; Cai, L. Minimizing the impact of maternal contamination in embryo ploidy assessment using spent culture medium in couples with chromosomal rearrangements couples: algorithms development and validation. Reprod Biomed Online. 2025, 104994. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; Brendel, M.; Gao, V.R.; Rajendran, S.; Kim, J.; Li, Q.; Malmsten, J.E.; Sierra, J.T.; Zisimopoulos, P.; Sigaras, A.; Khosravi, P.; Meseguer, M.; Zhan, Q.; Rosenwaks, Z.; Elemento, O.; Zaninovic, N.; Hajirasouliha, I. A non-invasive artificial intelligence approach for the prediction of human blastocyst ploidy: a retrospective model development and validation study. Lancet Digit Health. 2023, 5(1):e28-e40. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J. Involvement of oocyte-coded message in cell differentiation control of early human embryos. Development. 1989, 105(2):317-322. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J. Control of Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition in Human Embryos and Other Animal Species (Especially Mouse): Similarities and Differences. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23: 8562. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Kopecny, V. Nucleic acid synthesis and development of human male pronucleus. J Reprod Fertil. 1989, 86(2):549-558. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Kopecny, V. Assembly of the nucleolar precursor bodies in human male pronuclei is correlated with an early RNA synthetic activity. Exp Cell Res. 1990, 191(1):153-156. [CrossRef]

- Asami, M.; Lam, B.Y.H.; Ma, M.K.; Rainbow, K.; Braun, S.; VerMilyea, M.D.; Yeo, G.S.H.; Perry, A.C.F. Human embryonic genome activation initiates at the one-cell stage. Cell Stem Cell. 2022, 29(2):209-216.e4. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Kopecny, V.; Plachot, M.; Mandelbaum, J. Activation of nucleolar and extranucleolar RNA synthesis and changes in the ribosomal content of human embryos developing in vitro. J Reprod Fertil. 1986, 78(2):463-470. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Kopecny, V.; Plachot, M.; Mandelbaum, J. Ultrastructural and autoradiographic observations on multinucleated blastomeres of human cleaving embryos obtained by in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1987, 2(2): 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Toporcerová, S.; Špaková, I.; Šoltys, K.; Klepcová, Z.; Kľoc, M.; Bohošová, J.; Trachtová, K.; Peterová, L.; Mičková, H.; Urdzík, P.; Mareková, M., Slabý, O., Rabajdová, M. Small Non-Coding RNAs as New Biomarkers to Evaluate the Quality of the Embryo in the IVF Process. Biomolecules. 2022, 12:1687. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Chen, A.C.H.; Ng, E.H.Y.; Yeung, W.S.B.; Lee, Y.L. Non-coding RNAs as biomarkers for embryo quality and pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24:5751. [CrossRef]

- Kolanska, K.; Zerbib, E.; Dabi, Y.; Chabbert-Buffet, N.; Mathieu-d’Argent, E.; Favier, A.; Ferrier, C.; Touboul C.; Hamamah, S.; Daraï, E. Narrative review on biofluid ncRNAs expressions in conditions associated with couple infertility. Reprod Biomed Online, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Correia de Sousa, M.; Gjorgjieva, M.; Dolicka, D.; Sobolewski, C.; Foti, M. Deciphering miRNAs' action through miRNA editing. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20(24):6249. [CrossRef]

- Cuman, C.; Van Sinderen, M.; Gantier, M.P.; Rainczuk, K.; Sorby, K.; Rombauts, L.; Osianlis, T.; Dimitriadis, E. Human blastocyst secreted microRNA regulate endometrial epithelial cell adhesion. EBioMedicine, 2015. 2(10):1528-35. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbluth, E.M.; Shelton, D.N.; Wells, L.M.; Sparks, A.E.; Van Voorhis, B.J. Human embryos secrete microRNAs into culture media--a potential biomarker for implantation. Fertil Steril. 2014, 101(5):1493-1500. [CrossRef]

- Capalbo, A.; Ubaldi, F.M.; Cimadomo, D.; Noli, L.; Khalaf, Y.; Farcomeni, A.; Ilic, D.; Rienzi, L. MicroRNAs in spent blastocyst culture medium are derived from trophectoderm cells and can be explored for human embryo reproductive competence assessment. Fertil Steril. 2016, 105(1):225-235.e1-3. [CrossRef]

- Azzahra, T.B.; Febri, R.R.; Iffanolida, P.A.; Mutia, K.; Wiweko, B. The correlation of chronological age and micro ribonucleic acid-135b expression in spent culture media of in vitro fertilisation patient. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2022, 15(1):78-81. [CrossRef]

- Mutia, K.; Wiweko, B.; Abinawanto, A.; Dwiranti, A.; Bowolaksono, A. microRNAs as a biomarker to predict embryo quality assessment in in vitro fertilization. Int J Fertil Steril. 2023, 17(2):85-91. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zeng, H.; Fu, Y.; Ma, W.; Guo, X.; Luo, G.; Hua, R.; Wang, X.; Shi, X.; Wu, B.; Luo, C.; Quan, S. Specific plasma microRNA profiles could be potential non-invasive biomarkers for biochemical pregnancy loss following embryo transfer. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024, 24(1):351. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, W. Characterization of microRNAs in spent culture medium associated with human embryo quality and development. Ann Transl Med. 2021, 9(22):1648. [CrossRef]

- Braude, P.; Bolton, V.; Moore, S. Human gene expression first occurs between the four- and eight-cell stages of preimplantation development. Nature. 1988, 332(6163):459-461. [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Kopecny, V.; Plachot, M.; Mandelbaum, J. Early morphological signs of embryonic genome expression in human preimplantation development as revealed by quantitative electron microscopy. Dev Biol. 1988, 128(1):15-20. [CrossRef]

- Ferrick, L.; Lee, Y.S.L.; Gardner, D.K. Reducing time to pregnancy and facilitating the birth of healthy children through functional analysis of embryo physiology. Biol Reprod. 2019, 101(6):1124-1139. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, T.; Mann, M.; Aebersold, R.; Yates, J.R. 3rd, Bairoch, A.; Bergeron, J.J. Mass spectrometry in high-throughput proteomics: ready for the big time. Nat Methods. 2010, 7(9):681-5. [CrossRef]

- Pais, R.J.; Sharara, F.; Zmuidinaite, R.; Butler, S.; Keshavarz, S.; Iles, R. Bioinformatic identification of euploid and aneuploid embryo secretome signatures in IVF culture media based on MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020, 37(9):2189-2198. [CrossRef]

- Iles, R.K.; Sharara, F.I.; Zmuidinaite, R.; Abdo, G.; Keshavarz, S.; Butler, S.A. Secretome profile selection of optimal IVF embryos by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019, 36(6):1153-1160. [CrossRef]

- Butler, S.A.; Luttoo, J.; Freire, M.O.; Abban, T.K.; Borrelli, P.T.; Iles, R.K. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in the secretome of cultured embryos: hyperglycosylated hCG and hCG-free beta subunit are potential markers for infertility management and treatment. Reprod Sci. 2013, 20(9):1038-1045. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, F.; Meseguer, M.; Aparicio-Ruiz, B.; Piqueras, P.; Quiñonero, A.; Simón, C. New strategy for diagnosing embryo implantation potential by combining proteomics and time-lapse technologies. Fertil Steril. 2015, 104(4):908-914. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, R.R.; Zamora, R.B.; Sánchez, R.V.; Pérez J.G.; Bethencourt, J.C.A. Embryo sHLA-G secretion is related to pregnancy rate. Zygote. 2019, 27(2):78-81. [CrossRef]

- Bouvier, S.; Paulmyer-Lacroix, O.; Molinari, N.; Bertaud, A.; Paci, M.; Leroyer, A.; Robert, S.; Dignat George, F.; Blot-Chabaud, M.; Bardin, N. Soluble CD146, an innovative and non-invasive biomarker of embryo selection for in vitro fertilization. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12(3): e0173724. [CrossRef]

- Cortezzi, S.S.; Garcia, J.S.; Ferreira, C.R.; Braga, D.P.; Figueira, R.C.; Iaconelli, A. Jr; Souza, G.H.; Borges, E. Jr; Eberlin, MN. Secretome of the preimplantation human embryo by bottom-up label-free proteomics. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011, 401(4):1331-1339. [CrossRef]

- Leese, H.J.; Barton, A.M. Pyruvate and glucose uptake by mouse ova and preimplantation embryos. J Reprod Fertil. 1984, 72(1):9-13. [CrossRef]

- Leese, H.J.; Conaghan, J.; Martin, K.L.; Hardy, K. Early human embryo metabolism. Bioessays. 1993, 15(4):259-264. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.I. Metabolic switches during development and regeneration. Development. 2023, 150(20):dev202008. [CrossRef]

- Houghton, F.D.; Hawkhead, J.A.; Humpherson, P.G.; Hogg, J.E.; Balen, A.H.; Rutherford, A.J.; Leese, H.J. Non-invasive amino acid turnover predicts human embryo developmental capacity. Hum Reprod. 2002, 17(4):999-1005. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.K.; Lane, M.; Stevens, J.; Schoolcraft, W.B. Noninvasive assessment of human embryo nutrient consumption as a measure of developmental potential. Fertil Steril. 2001, 76(6):1175-1180. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Z.P.; Sakkas, D.; Behr, B. Symposium: innovative techniques in human embryo viability assessment. Non-invasive assessment of embryo viability by metabolomic profiling of culture media ('metabolomics'). Reprod Biomed Online. 2008, 17(4):502-507. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yin, T.; Peng, J.; Zou, Y.; Yang, J.; Shen, A.; Hu, J. Noninvasive metabolomic profiling of human embryo culture media using a simple spectroscopy adjunct to morphology for embryo assessment in in vitro fertilization (IVF). Int J Mol Sci. 2013, 14(4):6556-70. [CrossRef]

- Baştu, E.; Parlatan, U.; Başar, G.; Yumru, H.; Bavili, N.; Sağ, F.; Bulgurcuoğlu, S.; Buyru, F. Spectroscopic analysis of embryo culture media for predicting reproductive potential in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2017, 14(3):145-150. [CrossRef]

- Vergouw, C.G.; Kieslinger, D.C.; Kostelijk, E.H.; Botros, L.L.; Schats, R.; Hompes, P.G.; Sakkas, D.; Lambalk, C.B. Day 3 embryo selection by metabolomic profiling of culture medium with near-infrared spectroscopy as an adjunct to morphology: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2012, 27(8):2304-2311. [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, P.; Shen, S.; Hua, J.; Qian, S.; Prabhu, U.; Garcia, E.; Cedars, M.; Sukumaran, D.; Szyperski, T.; Andrews, C. (1)H NMR based profiling of spent culture media cannot predict success of implantation for day 3 human embryos. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012, 29(12):1435-1442. [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Huang, S.; Diao, F.; Gao, C.; Zhang, J.; Kong, L.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, C.; Qin, L.; Chen, Y.; Xu, M.; Gao, L.; Liang, B.; Hu, Y. Rapid and non-invasive diagnostic techniques for embryonic developmental potential: a metabolomic analysis based on Raman spectroscopy to identify the pregnancy outcomes of IVF-ET. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023, 11:1164757. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.I.; Ferreira, A.S.; Cecílio, M.H.M.; Chéles, D.S.; de Souza, R.C.M.; Nogueira, M.F.G.; Rocha, J.C. Artificial intelligence in the IVF laboratory: overview through the application of different types of algorithms for the classification of reproductive data. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020, 37(10):2359-2376. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Plaza Reyes, A.; Schell, J.P.; Weltner, J.; Ortega, N.M.; Zheng, Y.; Björklund, Å.K.; Baqué-Vidal, L; Sokka, J.; Trokovic, R.; Cox, B.; Rossant, J.; Fu, J.; Petropoulos, S.; Lanner, F. A comprehensive human embryo reference tool using single-cell RNA-sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2025, 22(1):193-206. [CrossRef]

- Kieslinger, D.C..; Lambalk, C.B.; Vergouw, C.G. The inconvenient reality of AI-assisted embryo selection in IVF. Nat Med. 2024. 30:3059–3060. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).