Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

19 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. ACT and Valuing

1.2. Valuing and Rule-Governed Behavior

1.3. Valuing in Research

1.4. Implications for Novel Research Methods

1.5. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Conditions

2.3.1. Intervention Condition

2.3.2. Informational Control Condition

2.4. Daily Interventions

2.5. Measures

3. Results

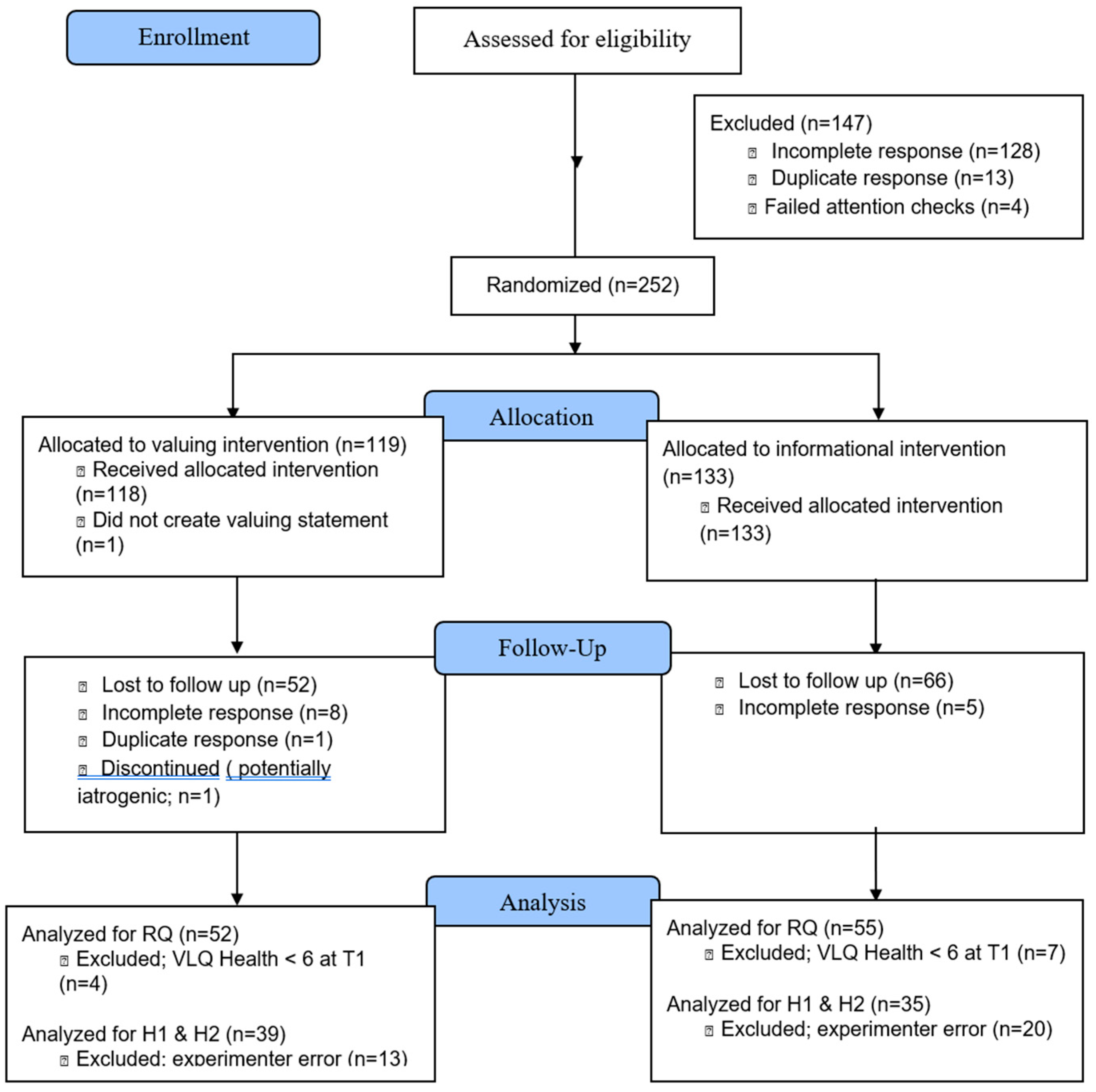

3.1. Study Flow and Baseline Descriptives

3.2. Change in Valued Health Behavior

3.3. Mediation by Values Awareness and Engagement

3.4. Overall Health Behavior Improvement

3.5. Program Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Intervention Conditions

4.2. Provider Feedback

4.3. Competing Reinforcer

4.3.1. Additional Sampling Methods

4.4. Methodological Lessons Learned

4.4.1. Intervention & Study Delivery

4.4.2. Intervention Dosing

4.4.3. Mechanisms of Change

4.4.4. Idiographic Approaches

4.4.5. Analytic Approaches

4.5. Program Evaluation

4.6. Knowledge Synthesis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amagai, S.; Pila, S.; Kaat, A.J.; Nowinski, C.J.; Gershon, R.C. Challenges in Participant Engagement and Retention Using Mobile Health Apps: Literature Review. J. Med Internet Res. 2022, 24, e35120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arevian, A.C.; O’hora, J.; Jones, F.; Mango, J.; Jones, L.; Willians, P.; Booker-Vaughns, J.; Jones, A.; Pulido, E.; Banner-Jackson, D.; et al. Participatory Technology Development to Enhance Community Resilience. Ethn. Dis. 2018, 28, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of American Colleges; Universities. (2021). The health of our students: What do we know? https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/health-our-students-what-do-we-know.

- Barlow, D.H.; Hayes, S.C. Alternating treatments design: One strategy for comparing the effects of two treatments in a single subject. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1979, 12, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes-Holmes, D.; Barnes-Holmes, Y.; Power, P.; Hayde, E.; Milne, R.; Stewart, I. Do you really know what you believe? Developing the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) as a direct measure of implicit beliefs. The Irish Psychologist 2006, 32, 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, K.; O’connor, M.; McHugh, L. A Systematic Review of Values-Based Psychometric Tools Within Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Psychol. Rec. 2019, 69, 457–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Jarrett, M.A.; Luebbe, A.M.; Garner, A.A.; Burns, G.L.; Kofler, M.J. Sleep in a large, multi-university sample of college students: sleep problem prevalence, sex differences, and mental health correlates. Sleep Heal. 2018, 4, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghoff, C.R.; Ritzert, T.R.; Forsyth, J.P. Value-guided action: Within-day and lagged relations of experiential avoidance, mindful awareness, and cognitive fusion in a non-clinical sample. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2018, 10, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W. Acceptance and commitment therapy for stress. In A Practical Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; Hayes, S.C., Strosahl, K.D., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: New York, 2004; pp. 275–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker, J.B.; Mull, K.E.; Kientz, J.A.; Vilardaga, R.; Mercer, L.D.; Akioka, K.J.; Heffner, J.L. Randomized, controlled pilot trial of a smartphone app for smoking cessation using acceptance and commitment therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 143, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buford, T.W.; Roberts, M.D.; Church, T.S. Toward Exercise as Personalized Medicine. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang, M.A.; Sa’at, N.; Sidik, T.M.I.T.A.B. Determination of Minimum Sample Size Requirement for Multiple Linear Regression and Analysis of Covariance Based on Experimental and Non-experimental Studies. Epidemiology, Biostat. Public Heal. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CallFire Inc. (2024). CallFire. https://callfire.com.

- Carpenter, J.S.; Andrykowski, M.A. Psychometric evaluation of the pittsburgh sleep quality index. J. Psychosom. Res. 1998, 45, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Open Science. (2025). OSF. https://osf.io/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). 2016 NHIS Questionnaire - Sample Adult. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Survey_Questionnaires/NHIS/2016/english/qadult.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019, November). Disability and Risk Factors. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/disability-and-risk-factors.htm.

- Chase, J.A.; Houmanfar, R.; Hayes, S.C.; Ward, T.A.; Vilardaga, J.P.; Follette, V. Values are not just goals: Online ACT-based values training adds to goal setting in improving undergraduate college student performance. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2013, 2, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, H.-W.; Yang, C.-C. Accuracy of Optical Heart Rate Sensing Technology in Wearable Fitness Trackers for Young and Older Adults: Validation and Comparison Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e14707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, B.A.; Casey, L.M. Technological adjuncts to increase adherence to therapy: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. The statistical power of abnormal-social psychological research: A review. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1962, 65, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, D.D. Psychometric evaluation of the Valued Living Questionnaire: Comparing distressed and normative samples. Doctoral dissertation, 2011. Available online: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3089.

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.L.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criddle, J.M.; Howard, H.; Bordieri, M. A Trial of a Daily Values Exercise on Participant Constructed Values and Valuing Behaviors. resented at the 2021 Association for Contextual Behavioral Science Virtual World Conference, online, 2021, July 24-27; 2021; p. 19. Available online: https://contextualscience.org/2021_virtual_world_conference.

- Csabonyi, M.; Phillips, L.J. Meaning in Life and Substance Use. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2017, 60, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyril, S.; Smith, B.J.; Possamai-Inesedy, A.; Renzaho, A.M.N. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: a systematic review. Glob. Heal. Action 2015, 8, 29842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, J. Valuing in ACT. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 2, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zambotti, M.; Claudatos, S.; Inkelis, S.; Colrain, I.M.; Baker, F.C. Evaluation of a consumer fitness-tracking device to assess sleep in adults. Chrono- Int. 2015, 32, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epton, T.; Harris, P.R.; Kane, R.; van Koningsbruggen, G.M.; Sheeran, P. The impact of self-affirmation on health-behavior change: A meta-analysis. Heal. Psychol. 2015, 34, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach, G. The law of attrition. J. Med. Internet Res. 2005, 7, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.-Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, F. Association between health literacy and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Public Heal. 2021, 79, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firestone, J.; Cardaciotto, L.; Levin, M.E.; Goldbacher, E.; Vernig, P.; Gambrel, L.E. A web-based self-guided program to promote valued-living in college students: A pilot study. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2019, 12, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein-Fox, L.; Pavlacic, J.M.; Buchanan, E.M.; Schulenberg, S.E.; Park, C.L. Valued Living in Daily Experience: Relations with Mindfulness, Meaning, Psychological Flexibility, and Stressors. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2019, 44, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryling, M. Relational Responding as a Psychological Event. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy 2012, 12, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, K. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Western adoption of Buddhist tenets? Transcult. Psychiatry 2014, 52, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, K.M.; Hellberg, S.N. Commentary: Person-specific, multivariate, and dynamic analytic approaches to actualize ACBS task force recommendations for contextual behavioral science. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2022, 25, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziano, T.; Abrahams-Gessel, S.; Surka, S.; Sy, S.; Pandya, A.; Denman, C.A.; Mendoza, C.; Puoane, T.; Levitt, N.S. Cardiovascular Disease Screening By Community Health Workers Can Be Cost-Effective In Low-Resource Countries. Heal. Aff. 2015, 34, 1538–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanvatkar, S.; Kankanhalli, A.; Rajan, V. User Models for Personalized Physical Activity Interventions: Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e11098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, N.G.; Sylvers, P.D.; Shearer, E.M.; Kane, M.-C.; Clasen, P.C.; Epler, A.J.; Plumb-Vilardaga, J.C.; Bonow, J.T.; Jakupcak, M. The efficacy of Focused Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in VA primary care. Psychol. Serv. 2016, 13, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmel, G.; Daeppen, J.-B. Recall Bias for Seven-Day Recall Measurement of Alcohol Consumption Among Emergency Department Patients: Implications for Case-Crossover Designs*. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2007, 68, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, K.M.; Squeglia, L.M. Research Review: What have we learned about adolescent substance use? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 59, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregg, J.A.; Namekata, M.S.; Louie, W.A.; Chancellor-Freeland, C. Impact of values clarification on cortisol reactivity to an acute stressor. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2014, 3, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, S.; Doucerain, M.; Morin, L.; Finkelstein-Fox, L. The relationship between value-based actions, psychological distress and well-being: A multilevel diary study. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 20, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.D.; Brand, J.C.; Cote, M.P.; Faucett, S.C.; Dhawan, A. Research Pearls: The Significance of Statistics and Perils of Pooling. Part 1: Clinical Versus Statistical Significance. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2017, 33, 1102–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. ACT made simple: An easy-to-Read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy; New Harbinger Publications, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R. Values Worksheet. The Happiness Trap 8-Week Online Program. https://thehappinesstrap.com/upimages/Values_Questionnaire.pdf. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselman, F.; Bosman, A.M.T. Studying Complex Adaptive Systems With Internal States: A Recurrence Network Approach to the Analysis of Multivariate Time-Series Data Representing Self-Reports of Human Experience. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behav. Ther. 2004, 35, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.C.; Merwin, R.M.; McHugh, L.; Sandoz, E.K.; A-Tjak, J.G.; Ruiz, F.J.; Barnes-Holmes, D.; Bricker, J.B.; Ciarrochi, J.; Dixon, M.R.; et al. Report of the ACBS Task Force on the strategies and tactics of contextual behavioral science research. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 20, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Pistorello, J.; Levin, M.E. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a Unified Model of Behavior Change. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 40, 976–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K. D. A practical guide to acceptance and commitment therapy; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz, M.V.; Mackin, D.M.; Trudeau, B.M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Wang, Y.; Banta, H.A.; Jewett, A.D.; Salzhauer, A.J.; Griffin, T.Z.; Jacobson, N.C. Randomized Trial of a Generative AI Chatbot for Mental Health Treatment. NEJM AI 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, K.E.; Smyth, J.M. Ecological momentary interventions: Incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. Br. J. Heal. Psychol. 2010, 15, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Curtiss, J.E.; Hayes, S.C. Beyond linear mediation: Toward a dynamic network approach to study treatment processes. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 76, 101824–101824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, G.; Koerner, K. Single case designs in clinical practice: A contemporary CBS perspective on why and how to. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2014, 3, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AHooker, S.; Masters, K.S. Purpose in life is associated with physical activity measured by accelerometer. J. Heal. Psychol. 2014, 21, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.A.; Masters, K.S.; Ranby, K.W. Integrating meaning in life and self-determination theory to predict physical activity adoption in previously inactive exercise initiates enrolled in a randomized trial. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.-W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; ABerlin, J.; et al. CONSORT 2025 explanation and elaboration: updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 2025, 389, e081124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, A.; Quesada, J.; Silva, J.; Judycki, S.; Mills, P.R. The impact of digital health interventions on health-related outcomes in the workplace: A systematic review. Digit. Heal. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyle, R.H. (Ed.) Handbook of structural equation modeling; The Guilford Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.L.; Williams, W.L.; Hayes, S.C.; Humphreys, T.; Gauthier, B.; Westwood, R. Whatever gets your heart pumping: the impact of implicitly selected reinforcer-focused statements on exercise intensity. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2016, 5, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, A.J.; Mason, T.B.; Benotsch, E.G. Psychological eating factors, affect, and ecological momentary assessed diet quality. Eat. Weight. Disord. - Stud. Anorexia, Bulim. Obes. 2019, 25, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, D.G.; Winer, E.S.; Salem, T. The current status of temporal network analysis for clinical science: Considerations as the paradigm shifts? J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 1591–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahwati, L.; Viswanathan, M.; Golin, C.E.; Kane, H.; Lewis, M.; Jacobs, S. Identifying configurations of behavior change techniques in effective medication adherence interventions: a qualitative comparative analysis. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, R.L.; Johnson, P.E.; Town, R.J.; Butler, M. A structured review of the effect of economic incentives on consumers' preventive behavior. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 27, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzler, K.E.; Robinson, P.J.; McGeary, D.D.; Mintz, J.; Kilpela, L.S.; Finley, E.P.; McGeary, C.; Lopez, E.J.; Velligan, D.; Munante, M.; et al. Addressing chronic pain with Focused Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in integrated primary care: findings from a mixed methods pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Hershner, S.D.; Strecher, V.J. Purpose in life and incidence of sleep disturbances. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissi, A.; Hughes, S.; Mertens, G.; Barnes-Holmes, D.; De Houwer, J.; Crombez, G. A Systematic Review of Pliance, Tracking, and Augmenting. Behav. Modif. 2017, 41, 683–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, J.; Potts, S.; Schoendorff, B.; Levin, M.E. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Multiple Versions of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Matrix App for Well-Being. Behav. Modif. 2017, 43, 246–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtines, W.M.; Alvarez, M.; Azmitia, M. Science and morality: The role of values in science and the scientific study of moral phenomena. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.M. Why Do College Graduates Behave More Healthfully Than Those Who Are Less Educated? J. Heal. Soc. Behav. 2017, 58, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazev, A.B.; Vidrine, D.J.; Arduino, R.C.; Gritz, E.R. Increasing access to smoking cessation treatment in a low-income, HIV-positive population: The feasibility of using cellular telephones. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004, 6, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, A.M.; Oswalt, S.B. The Value of College Health Promotion: A Critical Population and Setting for Improving the Public’s Health. Am. J. Heal. Educ. 2017, 48, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letourneau, B.; Sobell, L.C.; Sobell, M.B.; Agrawal, S.; Gioia, C.J. Two Brief Measures of Alcohol Use Produce Different Results: AUDIT-C and Quick Drinking Screen. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 41, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Fisher, C.B.; Weinberg, R.A. Toward a Science for and of the People: Promoting Civil Society through the Application of Developmental Science. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ELevin, M.; Petersen, J.M.; Durward, C.; Bingeman, B.; Davis, E.; Nelson, C.; Cromwell, S. A randomized controlled trial of online acceptance and commitment therapy to improve diet and physical activity among adults who are overweight/obese. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 11, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jin, X.; Ng, M.S.N.; Mann, K.F.; Wang, N.; Wong, C.L. Effects of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on fatigue interference and health-related quality of life among patients with advanced lung cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Asia-Pacific J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 9, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, J.; Dunsiger, S.; Thomas, J.G.; Ross, K.M.; Wing, R.R. Novel behavioral interventions to improve long-term weight loss: A randomized trial of acceptance and commitment therapy or self-regulation for weight loss maintenance. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 44, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LimeSurvey GmbH. (n.d.). LimeSurvey: An open source survey tool; LimeSurvey GmbH; Available online: https://www.limesurvey.org.

- Louisiana Contextual Science Research Group. Beyond Checking: A Behavior-Analytic Conceptualization of Privilege as a Manipulable Aspect of Context. Behav. Soc. Issues 2022, 31, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowie, W.M.; Verspoor, M.H. Individual Differences and the Ergodicity Problem. Lang. Learn. 2018, 69, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustria, M.L.; Noar, S.M.; Cortese, J.; Van Stee, S.K.; Glueckauf, R.L.; Lee, J. A meta-analysis of web-delivered tailored health behavior change interventions. Journal of Health Communication 2013, 18, 1039–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyerowitz-Katz, G.; Ravi, S.; Arnolda, L.; Feng, X.; Maberly, G.; Astell-Burt, T. Rates of Attrition and Dropout in App-Based Interventions for Chronic Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, S.E.; Lee, J.K.; Orsillo, S.M.; Roemer, L. The role of values-consistent behavior in generalized anxiety disorder. Depression Anxiety 2011, 28, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.M.; Brennan, L. Measuring and reporting attrition from obesity treatment programs: A call to action! Obes. Res. Clin. Pr. 2015, 9, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, P.C. On the implications of the classical ergodic theorems: Analysis of developmental processes has to focus on intra-individual variation. Dev. Psychobiol. 2007, 50, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, K.; Beauchamp, M.; Prothero, A.; Joyce, L.; Saunders, L.; Spencer-Bowdage, S.; Dancy, B.; Pedlar, C. The effectiveness of motivational interviewing for health behaviour change in primary care settings: a systematic review. Heal. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 9, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.; Richards, R.; Jones, R.A.; Whittle, F.; Woolston, J.; Stubbings, M.; Sharp, S.J.; Griffin, S.J.; Bostock, J.; Hughes, C.A.; et al. Supporting Weight Management during COVID-19 (SWiM-C): twelve-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial of a web-based, ACT-based, guided self-help intervention. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 47, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Whittemore, R.; Vlahov, D.; Dunton, G. 824-P: Ecological Momentary Assessment of Diabetes Self-Management: A Systematic Review of Methods and Procedures. Diabetes 2019, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor, N.; Frenkel, A.; Winsberg, M. Improving Well-being With a Mobile Artificial Intelligence–Powered Acceptance Commitment Therapy Tool: Pragmatic Retrospective Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e36018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago. New survey finds large number of people skipping necessary medical care because of cost.; NORC.org. https://www.norc.org/NewsEventsPublications/PressReleases/Pages/survey-finds-large-number-of-people-skipping-necessary-medical-care-because-cost.aspx; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M.G.; Przeworski, A.; Consoli, A.J.; Taylor, C.B. A randomized controlled trial of ecological momentary intervention plus brief group therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy 2014, 51, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, S.L.; McCann, L.R. Development and validation of the Diet Quality Tool for use in cardiovascular disease prevention settings. Aust. J. Prim. Heal. 2012, 18, 138–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Hofmann, S.G. A process-based approach to cognitive behavioral therapy: A theory-based case illustration. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1002849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oscarsson, M.; Carlbring, P.; Andersson, G.; Rozental, A. A large-scale experiment on New Year’s resolutions: Approach-oriented goals are more successful than avoidance-oriented goals. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0234097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plumb, J.C.; Stewart, I.; Dahl, J.; Lundgren, T. In search of meaning: Values in modern clinical behavior analysis. Behav. Anal. 2009, 32, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, S.; Krafft, J.; Levin, M.E. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Guided Self-Help for Overweight and Obese Adults High in Weight Self-Stigma. Behav. Modif. 2020, 46, 178–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, E.; Dorstyn, D.; Taylor, A.; Rose, A. Attrition in Psychological mHealth Interventions for Young People: A Meta-Analysis. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2023, 9, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, G.; Gon, C. A systematic review of values interventions in acceptance and commitment therapy. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy 2020, 20, 355–372. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan, P.; Pramesh, C.; Buyse, M. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Clinical versus statistical significance. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2015, 6, 169–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.J.; Kelly, J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reljic, D.; Lampe, D.; Wolf, F.; Zopf, Y.; Herrmann, H.J.; Fischer, J. Prevalence and predictors of dropout from high-intensity interval training in sedentary individuals: A meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 1288–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.M.; Melzer, T. Beliefs as barriers to healthy eating and physical activity. Aust. J. Psychol. 2016, 68, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E. Assessment of Physical Activity by Self-Report: Status, Limitations, and Future Directions. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2000, 71 (Suppl. 2), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, B.T.; Ciarrochi, J.; Hofmann, S.G.; Chin, F.; Gates, K.M.; Hayes, S.C. Toward empirical process-based case conceptualization: An idionomic network examination of the process-based assessment tool. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2022, 25, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Klein, W.M.; Rothman, A.J. Health Behavior Change: Moving from Observation to Intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2017, 68, 573–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, G. Power Analysis and Sample Size Planning in ANCOVA Designs. Psychometrika 2020, 85, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, B.J.; Nasreddine, A.Y.; Kocher, M.S. Overcoming the Funding Challenge: The Cost of Randomized Controlled Trials in the Next Decade. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2012, 94, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, M.; Llewellyn, A.; Owen, C.G.; Woolacott, N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2015, 17, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, E.; Bossarte, R.M. Incentives for Survey Participation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.M.; Duque, L.; Huffman, J.C.; Healy, B.C.; Celano, C.M. Text Message Interventions for Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 58, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.E.; Juarascio, A. From Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) to Ecological Momentary Intervention (EMI): Past and Future Directions for Ambulatory Assessment and Interventions in Eating Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smout, M.; Davies, M.; Burns, N.; Christie, A. Development of the Valuing Questionnaire (VQ). J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2014, 3, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackpool, C.M. valuation of a consumer fitness-tracking device to assess sleep in adults. master's thesis, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Staines, G.L. The Causal Generalization Paradox: The Case of Treatment Outcome Research. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2008, 12, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, A.; O’connor, M.; Feerick, E.; Kerr, J.; McHugh, L. Testing the relationship between health values consistent living and health-related behavior. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 17, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steene-Johannessen, J.; Anderssen, S.A.; VANDERPloeg, H.P.; Hendriksen, I.J.M.; Donnelly, A.E.; Brage, S.; Ekelund, U. Are Self-report Measures Able to Define Individuals as Physically Active or Inactive? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormacq, C.; Wosinski, J.; Boillat, E.; Broucke, S.V.D. Effects of health literacy interventions on health-related outcomes in socioeconomically disadvantaged adults living in the community: a systematic review. JBI Évid. Synth. 2020, 18, 1389–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobell, L.C.; Brown, J.; Leo, G.I.; Sobell, M.B. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2003, 71, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraça, E.V.; Markland, D.; Silva, M.N.; Ryan, R.M. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ti, L.; Ti, L. Leaving the Hospital Against Medical Advice Among People Who Use Illicit Drugs: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Heal. 2015, 105, 2587–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, M.; Tomczak, E. The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends in Sports Sciences 2014, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Törneke, N.; Luciano, C.; Salas, S.V. (2008). Rule-Governed Behavior and Psychological Problems. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy 2008, 8, 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- University of Minnesota. College student health survey; https://www.bhs.umn.edu/surveys; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van de Mortel, T.F. (2008). Faking it: social desirability response bias in self-report research. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 2008, 25, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- van der Zee, K.I.; Bakker, A.B.; Bakker, P. Improving health and well-being in university students: The effectiveness of a web-based health training. Health Education Research 2019, 34, 228–242. [Google Scholar]

- Vertsberger, D.; Naor, N.; Winsberg, M. Adolescents’ Well-being While Using a Mobile Artificial Intelligence–Powered Acceptance Commitment Therapy Tool: Evidence From a Longitudinal Study. JMIR AI 2022, 1, e38171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorheis, P.; Zhao, A.; Kuluski, K.; Pham, Q.; Scott, T.; Sztur, P.; Khanna, N.; Ibrahim, M.; Petch, J. Integrating behavioral science and design thinking to develop mobile health interventions: Systematic scoping review. Preprint 2022. [CrossRef]

- Vowles, K. E.; McCracken, L. M. Acceptance and values-based action in chronic pain: A study of treatment process and outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2008, 76, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallin, D.; Ekman, A.; Krevers, B. Assessing self-reported health values and behavioral patterns. Health Psychology Review 2018, 12, 210–223. [Google Scholar]

- Walser, R.D.; Evans, W.R.; Farnsworth, J.K.; Drescher, K.D. Initial steps in developing acceptance and commitment therapy for moral injury among combat veterans: Two pilot studies. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2024, 32, 100733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.L.; Sheeran, P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? Psychological Bulletin 2006, 132, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wersebe, H.; Lieb, R.; Meyer, A.H.; Hofer, P.; Gloster, A.T. The link between stress, well-being, and psychological flexibility during an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy self-help intervention. Int. J. Clin. Heal. Psychol. 2018, 18, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K. G.; DuFrene, T. Things might go terribly, horribly wrong: A guide to life liberated from anxiety; New Harbinger, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K. G.; Murrell, A.R. Values work in acceptance and commitment therapy: Setting a course for behavioral treatment. Directions in Clinical Psychology 2004, 16, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K. G.; Sandoz, E. K. Values work in acceptance and commitment therapy: Setting a course for behavioral treatment. In The Wiley handbook of contextual behavioral science; Zettle, R., Hayes, S.C., Barnes-Holmes, D., Biglan, A., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell, 2010; pp. 213–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.G.; Sandoz, E.K.; Kitchens, J.; Roberts, M. The Valued Living Questionnaire: Defining and Measuring Valued Action within a Behavioral Framework. Psychol. Rec. 2010, 60, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.J.C.; Dietze, P.M.; Crockett, B.; Lim, M.S.C. Participatory development of MIDY (Mobile Intervention for Drinking in Young people). BMC Public Heal. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammons, R.D.; Gaines, T.A. The transformation of consequential functions in accordance with the relational frames of same and opposite. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior 2004, 82, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettle, R.D.; Hayes, S.C. Rule-governed behavior: A potential theoretical framework for cognitive–behavioral therapy. The Behavior Analyst 1982, 5, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Full Sample (n = 107) |

Valuing (n = 52) |

Informational (n = 55) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age M (SD) | 20.30 (12.26) | 19.96 (5.42) | 19.78 (4.2) |

| Gender Identity n (%) | |||

| Cisgender Woman | 71 (66.4) | 36 (65.6) | 35 (67.3) |

| Cisgender Man | 31 (29.0) | 15 (27.3) | 16 (30.8) |

| Trans Woman | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Trans Man | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nonbinary | 2 (1.9) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sexual Identity n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Heterosexual | 84 (78.5) | 38 (69.1) | 46 (88.5) |

| Bisexual | 11 (10.3) | 7 (12.7) | 4 (7.7) |

| Lesbian | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.9) |

| Gay | 4 (3.7) | 3 (5.5) | 1 (1.9) |

| Pansexual | 3 (2.8) | 3 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| No Answer | 3 (2.8) | 3 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Race/Ethnic Identity n (%) | |||

| White/European American | 91 (85.0) | 48 (87.3) | 43 (82.7) |

| Black/African American | 9 (8.4) | 4 (7.3) | 5 (9.6) |

| Latin/a/o/x | 9 (8.4) | 3 (5.4) | 6 (10.8) |

| Asian/Asian American | 4 (3.7) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (5.8) |

| Indigenous Tribes/First Peoples/Native American | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| More than one race/mixed race | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Not Listed | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Values Progress (VQ-P) | - | 0.17 | 0.06 | -0.02 | 0.09 | -0.30** |

| 2. Physical Activity (IPAQ) | - | -0.08 | 0.20 | -0.04 | -0.11 | |

| 3. Nicotine Consumption | - | -0.13 | 0.26** | 0.11 | ||

| 4. Diet Quality (DQT) | - | -0.05 | 0.06 | |||

| 5. Alcohol Use (QDS) | - | 0.06 | ||||

| 6. Sleep Quality (PSQI) | - | |||||

| M | 20.10 | 657.30 | 0.40 | 40.00 | 3.40 | 6.70 |

| SD | 4.90 | 1232.20 | 0.70 | 18.10 | 7.30 | 3.10 |

| Health Domain | F | p | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity (IPAQ) | |||

| Baseline | 260.15 | < .002* | .714 |

| Condition | 3.68 | .058 | .034 |

| Nicotine Consumption | |||

| Baseline | 6.66 | .011* | .060 |

| Condition | 0.01 | .936 | .000 |

| Diet Quality (DQT) | |||

| Baseline | 4.79 | .031* | .044 |

| Condition | 0.92 | .340 | .009 |

| Alcohol Use (QDS) | |||

| Baseline | 98.25 | < .002* | .486 |

| Condition | 0.11 | .746 | .001 |

| Sleep Quality (PSQI) | |||

| Baseline | 67.39 | < .002* | .393 |

| Condition | 0.49 | .484 | .005 |

| Health Domain | Valuing (n = 52) |

Informational (n = 55) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | d | |

| Physical Activity (IPAQ) | |||||

| Baseline | 672.40 | 967.70 | 643.10 | 1447.70 | 0.02 |

| Post-test | 626.00 | 843.80 | 420.60 | 432.00 | 0.31 |

| Nicotine Consumption | |||||

| Baseline | 0.40 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.70 | 0.00 |

| Post-test | 0.40 | 0.70 | 0.40 | 0.80 | 0.00 |

| Diet Quality (DQT) | |||||

| Baseline | 38.60 | 17.80 | 41.30 | 18.40 | -0.15 |

| Post-test | 40.00 | 19.10 | 40.60 | 18.30 | -0.03 |

| Alcohol Use (QDS) | |||||

| Baseline | 3.40 | 6.30 | 3.40 | 8.10 | 0.00 |

| Post-test | 3.20 | 6.20 | 2.80 | 5.20 | 0.07 |

| Sleep Quality (PSQI) | |||||

| Baseline | 6.20 | 3.20 | 7.30 | 3.40 | -0.33 |

| Post-test | 4.50 | 2.30 | 5.30 | 2.30 | -0.35 |

| Content | Total | Valuing | Informational |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good reminder | 19 | 15 | 4 |

| Motivating | 16 | 6 | 10 |

| Uncategorized | 13 | 5 | 8 |

| Good information | 10 | - | 10 |

| Good, general | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Not applicable to me | 8 | - | 8 |

| Helped with my goals | 8 | 8 | - |

| Felt personalized | 10 | 9 | 1 |

| Bad, general | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Thought provoking | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Timing of texts | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Ambivalent | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| Helped valued behavior | 5 | 5 | - |

| Actionable | 2 | - | 2 |

| Unhealthy reminder | 2 | - | 2 |

| Future suggestions | 2 | - | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).