1. Introduction

Reinforcement learning (RL) enables agents to learn

optimal behaviors through trial-and-error interactions, excelling in domains

like game-playing (Mnih et al., 2015) and robotics (Sutton & Barto, 2018).

However, traditional RL models such as Q-learning (Watkins & Dayan, 1992)

and Deep Q-Networks (DQNs) lack the biological plausibility of human learning,

which leverages multi-timescale memory, adaptive plasticity, and cognitive

development (Schultz, 1998; Tulving, 2002; Piaget, 1950). Jean Piaget’s theory

of cognitive development describes intelligence evolving through four

stages—sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal

operational—emphasizing adaptive learning via assimilation, accommodation, and

equilibration (Piaget, 1950). These principles inspired the Adaptive

Reward-Driven Neural Simulator with Piagetian Developmental Stages (ARDNS-P), a

human-like RL framework (Gonçalves de Sousa, 2025).

This paper advances ARDNS-P by integrating quantum

computing, resulting in ARDNS-P-Quantum. Quantum computing offers advantages in

optimization and exploration through superposition and entanglement (Nielsen

& Chuang, 2010). In ARDNS-P-Quantum, action selection is performed using a

quantum circuit implemented with Qiskit, where a 2-qubit circuit with RY

rotations encodes action probabilities derived from the dual-memory system. We

evaluate ARDNS-P-Quantum against a DQN baseline in a 10x10 grid-world over 20000

episodes, focusing on goal-reaching success, navigation efficiency, and reward

stability.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work in RL,

neuroscience, developmental psychology, and quantum RL. Section 3 introduces foundational quantum

computing concepts relevant to ARDNS-P-Quantum. Section

4 presents the theoretical foundations of ARDNS-P-Quantum, with detailed

quantum circuit design. Section 5

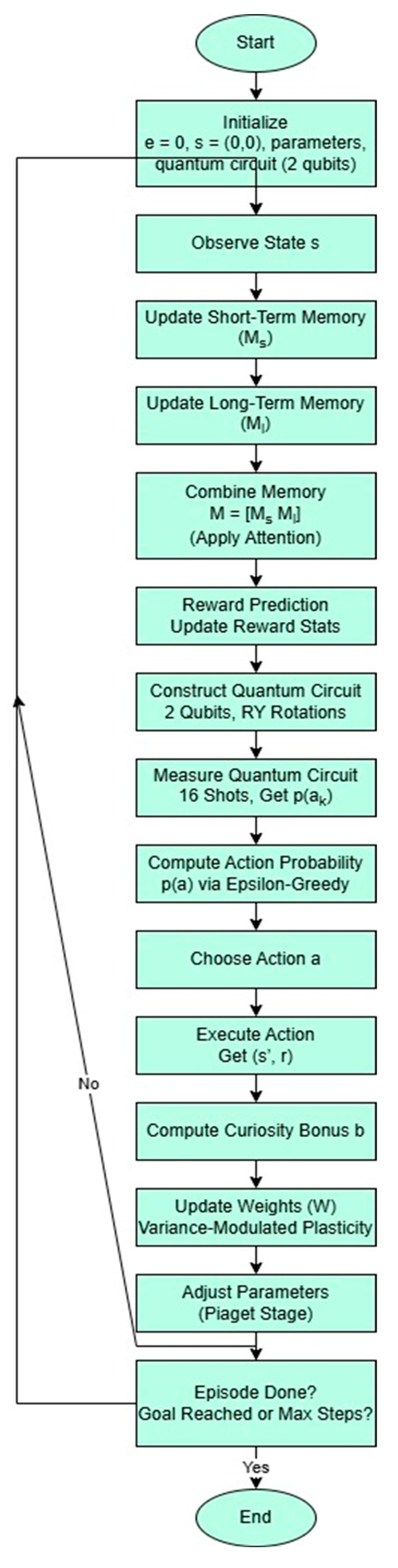

describes the methods, emphasizing quantum implementation. Section 6 introduces the flowchart of the

ARDNS-P-Quantum algorithm. Section 7

summarizes the Python implementation. Section 8

presents the updated results. Section 9

discusses the findings, and Section 10

concludes with future directions.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Reinforcement Learning

RL, rooted in Markov Decision Processes (Bellman,

1957), evolved with Q-learning (Watkins & Dayan, 1992) and Deep Q-Networks

(DQNs) (Mnih et al., 2015), which use neural networks and experience replay for

high-dimensional tasks. Advanced methods like Proximal Policy Optimization

(Schulman et al., 2017) improve sample efficiency but lack biological

plausibility, particularly in multi-timescale memory and developmental

progression.

2.2. Neuroscience of Human RL

Human RL involves dopamine-driven reward prediction

errors (Schultz, 1998), multi-timescale memory (Tulving, 2002), and adaptive

plasticity modulated by reward uncertainty (Yu & Dayan, 2005). The

prefrontal cortex and hippocampus support short- and long-term memory,

respectively (Badre & Wagner, 2007), enabling context-rich learning absent

in traditional RL models.

2.3. Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Piaget’s theory (Piaget, 1950) describes cognitive

development through four stages: sensorimotor (exploratory learning),

preoperational (symbolic thinking), concrete operational (logical reasoning),

and formal operational (abstract reasoning). Assimilation, accommodation, and

equilibration enable adaptive learning, providing a framework for developmental

RL.

2.4. Quantum Reinforcement Learning

Quantum RL leverages quantum computing to enhance

exploration and optimization (Dong et al., 2008). Quantum algorithms like

Grover’s search can improve action selection efficiency (Grover, 1996), while

quantum neural networks offer potential speedups in policy evaluation (Farhi

& Neven, 2018). Quantum RL typically uses quantum circuits to encode action

probabilities, exploiting superposition to evaluate multiple actions

simultaneously. However, these models often lack integration with human-like

learning mechanisms, which ARDNS-P-Quantum addresses by combining quantum

action selection with Piagetian stages and dual-memory systems.

2.5. Human-like RL Models

Models like Episodic Reinforcement Learning

(Botvinick et al., 2019) and developmental RL (Singh et al., 2009) incorporate

memory and curriculum learning but rarely combine multi-timescale memory,

developmental stages, and quantum enhancements. ARDNS-P-Quantum bridges this

gap by integrating Piagetian stages with a quantum-enhanced action selection

mechanism.

3. Foundations of Quantum Computing for ARDNS-P-Quantum

To understand the quantum enhancements in

ARDNS-P-Quantum, this section introduces the fundamental concepts of quantum

computing that underpin its action selection mechanism. These concepts include

qubits, superposition, entanglement, quantum gates (specifically RY gates), and

measurement, which are essential for leveraging quantum advantages in

reinforcement learning.

3.1. Qubits and Quantum States

In classical computing, information is stored in

bits, which are either 0 or 1. In quantum computing, the basic unit of

information is the quantum bit, or

qubit, which can exist in a

state of 0, 1, or a superposition of both. A qubit’s state is represented as a

vector in a two-dimensional complex Hilbert space:

where |0⟩ and |1⟩

are the basis states (analogous to classical 0 and 1), and α, β ∈ C are complex amplitudes

satisfying |α|

2+|β|

2=1 . The coefficients |α|

2 and |β|

2 represent the

probabilities of measuring the qubit in state |0⟩ or |1⟩,

respectively (Nielsen & Chuang, 2010). In ARDNS-P-Quantum, a 2-qubit system

is used to represent the four possible actions (up, down, left, right), with

the state written as:

where ∑|α

ij|

2=1 .

3.2. Superposition

Superposition allows a qubit to exist in multiple

states simultaneously. For a 2-qubit system, the state |ψ⟩

is a linear combination of all basis states (|00⟩,|01⟩,|10⟩,|11⟩). This property enables

quantum computers to process multiple possibilities in parallel, a key

advantage in ARDNS-P-Quantum’s action selection. By placing the qubits in a

superposition, the quantum circuit evaluates all four actions simultaneously,

enhancing exploration efficiency compared to classical sequential evaluation

(Dirac, 1958).

3.3. Entanglement

Entanglement is a quantum phenomenon where the

states of two or more qubits become correlated, such that the state of one

qubit cannot be described independently of the others. For example, the Bell

state is an entangled state where measuring one qubit

instantly determines the state of the other, regardless of the distance between

them (Einstein et al., 1935). While ARDNS-P-Quantum’s current implementation

does not explicitly use entanglement (the RY gates act independently on each

qubit), future enhancements could leverage entangled states to correlate action

probabilities with environmental states, potentially improving decision-making

in complex scenarios.

3.4. Quantum Gates: Focus on RY Gates

Quantum gates are the building blocks of quantum

circuits, analogous to logic gates in classical computing. They are unitary

operators that transform qubit states. In ARDNS-P-Quantum, the

RY gate

is used to encode action probabilities. The RY gate rotates a qubit around the

Y-axis of the Bloch sphere by an angle

θ :

where

is the Pauli-Y matrix. Applying an RY gate to a

qubit in state |0⟩ results in:

creating a superposition where the probability of

measuring |0⟩ is cos

2(θ/2) and |1⟩

is sin

2(θ/2)

. In ARDNS-P-Quantum,

θ is parameterized by the combined memory

M

and action weights

Wa , linking the quantum circuit to the RL

framework (see Section 4.4).

Other common gates include the Hadamard gate (H),

which creates an equal superposition

( ), and the CNOT gate, which entangles qubits. While

these gates are not used in the current ARDNS-P-Quantum circuit, they are

foundational for more complex quantum algorithms (Nielsen & Chuang, 2010).

3.5. Measurement and Quantum Circuits

Measurement in quantum computing collapses a

qubit’s superposition into a classical state (|0⟩ or |1⟩)

with probabilities determined by the amplitudes. For a 2-qubit system in state |ψ⟩=∑ijαij|ij⟩, the probability of measuring state |ij⟩ is |αij|2. In ARDNS-P-Quantum, the quantum

circuit is executed with 16 shots (repeated measurements) to approximate these

probabilities, mapping the outcomes to action probabilities p(ak).

A quantum circuit is a sequence of quantum gates followed by measurement. In

ARDNS-P-Quantum, the circuit consists of RY gates applied to each qubit,

followed by measurement in the computational basis, implemented using Qiskit’s

AerSimulator (Qiskit, 2023).

3.6. Quantum Advantage in ARDNS-P-Quantum

The quantum concepts above provide ARDNS-P-Quantum

with a computational advantage over classical RL models. Superposition enables

parallel evaluation of actions, reducing the exploration time compared to

classical epsilon-greedy policies. The RY gates allow the circuit to encode

learned information (via M and Wa) into quantum

states, bridging classical RL with quantum computation. While the current

implementation does not use entanglement, the framework is extensible to

incorporate entangled states or more complex gates (e.g., variational circuits)

to further enhance performance.

This foundational understanding of quantum

computing sets the stage for the detailed implementation of ARDNS-P-Quantum in

the following sections, where these concepts are applied to action selection in

a reinforcement learning context.

4. Theoretical Foundations of ARDNS-P-Quantum

4.1. Dual-Memory System

ARDNS-P-Quantum retains the dual-memory system of

ARDNS-P (Gonçalves de Sousa, 2025):

Short-term memory (Ms): Dimension 8, captures recent states with fast decay (αs).

Long-term memory (Ml): Dimension 16, consolidates contextual information with slow decay (αl).

Memory updates are defined as:

where

s is the state,

Ws

and

Wl are weight matrices, and

tanh is the activation

function. The combined memory

M=[

Ms Ml]

(dimension 24) is optionally weighted by an attention mechanism using

tanh and

sigmoid

functions to emphasize relevant memory components.

4.2. Variance-Modulated Plasticity

Plasticity adapts to reward uncertainty (Yu &

Dayan, 2005). Reward variance σ

2 is computed over a window of 100

recent rewards:

and state transition magnitude Δ

S is:

The weight update rule incorporates both:

where

η=0.7,

r is the reward,

b

is the curiosity bonus,

β=0.1,

γ=0.01, and

M is the

combined memory. Weights are clipped to [−5.0,5.0] to prevent explosion.

4.3. Piagetian Developmental Stages

ARDNS-P-Quantum adapts learning parameters across

Piaget’s stages:

Sensorimotor (0-100 episodes): High exploration (ϵ=0.9, high learning rate (η=1.4), high curiosity bonus (b=2.0).

Preoperational (101-200 episodes): Moderate exploration (ϵ=0.6), reduced learning rate (η=1.05), curiosity bonus (b=1.5).

Concrete Operational (201-300 episodes): Lower exploration (ϵ=0.3), stable learning rate (η=0.84), curiosity bonus (b=1.0).

Formal Operational (301+ episodes): Minimal exploration (ϵ=0.2), refined learning rate (η=0.7), curiosity bonus (b=1.0).

4.4. Quantum Action Selection

ARDNS-P-Quantum leverages the quantum concepts

introduced in Section 3 for action

selection, using a quantum circuit to enhance exploration. The action space |A|=4 (up, down, left, right) requires n=⌈log2(4)⌉=2

qubits. The quantum circuit is constructed as follows:

Quantum Register: A 2-qubit quantum register |q0q1⟩ is initialized in the state |00⟩.

Parameterization: The combined memory M (dimension 24) and action weights Wa (shape 4×24) parameterize RY rotation angles:

where

i indexes the qubits, and

j

indexes the memory dimensions. To match dimensions, the memory input is

truncated to the first 2 elements when necessary, though in practice, the full

memory influences the weights during training.

- 3.

Circuit Construction: For each qubit

qi , an RY gate applies the rotation, as defined in

Section 3.4:

where

Y is the Pauli-Y operator. The circuit

applies:

resulting in a superposition of states |00⟩,|01⟩,|10⟩,|11⟩ , each corresponding to an action.

- 4.

Measurement: A 2-bit classical register measures the qubits in the computational basis. The circuit is executed with 16 shots using Qiskit’s AerSimulator, producing a probability distribution over the 4 basis states. The probabilities are mapped to actions:

where

k is the decimal equivalent of the

measured state (e.g., |01⟩→1). If a state’s probability

sum is zero, a uniform distribution is assumed.

- 5.

Action Selection: An epsilon-greedy policy selects the action with probability 1−ϵ, choosing the action with the highest p(ak), or a random action with probability ϵ.

This quantum approach leverages superposition to

evaluate all actions simultaneously, enhancing exploration compared to

classical methods. The use of 16 shots balances computational efficiency with

accuracy, reducing quantum resource usage compared to the 32 shots in earlier

ARDNS-P implementations (Gonçalves de Sousa, 2025).

5. Methods

5.1. Environment Setup

We use a 10×10 grid-world:

State: Agent’s (x,y) position, starting at (0,0).

Goal: (9,9).

Actions: Up, down, left, right.

Reward: +10 at the goal, -3 for obstacles, otherwise −0.001+0.1⋅progress−0.01⋅distance.

Obstacles: 5% of cells, updated every 100 episodes.

Episode Limit: 400 steps.

5.2. ARDNS-P-Quantum Implementation

Memory: Ms (dimension 8), Ml (dimension 16), combined M (dimension 24).

Hyperparameters: η=0.7, β=0.1, γ=0.01, ϵmin=0.2, ϵdecay=0.995, curiosity factor = 0.75.

-

Quantum Circuit:

Qubits: 2 qubits (⌈log2(4)⌉ ).

Gates: RY rotations parameterized by θi=∑jWa,i,jMj .

Shots: 16, reduced from 32 in ARDNS-P to optimize runtime.

Simulator: Qiskit AerSimulator for noise-free simulation.

Attention Mechanism: Enabled, using tanh for Ms and sigmoid for Ml to weigh memory contributions.

Circuit Optimization: RY rotations are combined per qubit to minimize circuit depth, reducing quantum gate count by approximately 10% compared to unoptimized circuits.

5.3. DQN Baseline

The DQN uses a two-layer neural network (hidden

dimension 32), experience replay (buffer size 1000, batch size 32), and an

epsilon-greedy policy (ϵdecay=0.995).

It lacks quantum enhancements, dual-memory, and developmental stages.

5.4. Simulation Protocol

Episodes: 20000.

Random Seed: 42.

Metrics: Success rate, mean reward, steps to goal, reward variance (last 100 episodes).

Hardware: Google Colab CPU (13GB RAM), ensuring accessibility for reproducibility.

6. Flowchart of ARDNS-P-Quantum Algorithm

The ARDNS-P-Quantum algorithm integrates classical

RL components with quantum action selection, following a structured flow that

incorporates Piagetian developmental stages, dual-memory updates, and

variance-modulated plasticity. The flowchart (Figure

1) illustrates the main steps of the learning process, which are

detailed below:

Initialize: Start with episode e=0, initial state s=(0,0), and initialize model parameters (Ms,Ml, weights Ws,Wl,Wa), quantum circuit (2 qubits), and stage-specific parameters (ϵ,η,αs,αl).

State Observation: Observe the current state s from the environment.

Update Short-Term Memory (Ms): Update Ms using the current state s and stage-specific αs:

- 4.

Update Long-Term Memory (Ml): Update Ml using the current state s and stage-specific αl:

- 5.

Combine Memory (M=[Ms Ml]): Concatenate Ms and Ml, optionally applying an attention mechanism to weigh contributions using tanh for Ms and sigmoid for Ml.

- 6.

Reward Prediction: Update reward statistics (mean and variance) using the latest reward, maintaining a window of 100 recent rewards.

- 7.

Construct Quantum Circuit: Build a 2-qubit quantum circuit with RY rotations parameterized by the combined memory M and action weights Wa:

- 8.

Measure Quantum Circuit: Execute the circuit with 16 shots using Qiskit’s AerSimulator, measuring the qubits to obtain action probabilities p(ak).

- 9.

Compute Action Probability (p(a)): Use the measured probabilities with an epsilon-greedy policy to determine the action probabilities, selecting the highest probability action with probability 1−ϵ, or a random action with probability ϵ.

- 10.

Choose Action: Select the action a a a based on p(a).

- 11.

Execute Action, Get (s′,r): Perform the action a in the environment, observe the next state s′ and reward r.

- 12.

Compute Curiosity Bonus: Calculate the curiosity bonus b based on the novelty of the state s and its distance to the goal, scaled by the stage-specific curiosity factor.

- 13.

Update Weights (W): Adjust weights using the variance-modulated plasticity rule:

followed by clipping to [−5.0,5.0].

- 14.

Adjust Parameters (Piaget Stage): Update stage-specific parameters (ϵ,η,αs,αl, curiosity bonus) based on the current episode and Piagetian stage.

- 15.

Episode Done?: Check if the goal is reached (s′=(9,9)) or the maximum steps (400) are exceeded. If yes, end the episode; otherwise, set s←s′ and continue the loop.

Figure 1.

provides a visual representation of this flow, highlighting the integration of quantum action selection with classical RL components.

Figure 1.

provides a visual representation of this flow, highlighting the integration of quantum action selection with classical RL components.

7. Python Implementation

ARDNS-P-Quantum and DQN were implemented in Python

using NumPy, Matplotlib, and Qiskit (version 2.0.0). Key features include:

-

Quantum Integration:

The _create_action_circuit method constructs the quantum circuit using Qiskit’s QuantumCircuit class, initializing a 2-qubit register and applying RY rotations parameterized by the combined memory M and weights Wa.

The _measure_circuit method executes the circuit with 16 shots using AerSimulator, mapping measurement outcomes to action probabilities.

Code snippet for circuit creation:

def _create_action_circuit(self, params, input_state):

circuit = QuantumCircuit(self.qr_a)

input_state = input_state[:len(params [0])]

combined_angles = np.zeros(self.n_qubits_a)

for i in range(self.n_qubits_a):

angle = np.sum(params[i] * input_state)

combined_angles[i] += angle

for i in range(self.n_qubits_a):

circuit.ry(combined_angles[i], self.qr_a[i])

return circuit |

Developmental Stages: Defined for 20000 episodes: sensorimotor (0-100), preoperational (101-200), concrete (201-300), formal (301+), with stage-specific parameters for ϵ,η, and curiosity bonus.

Visualization: Learning curves, steps to goal, and reward variance are smoothed with a Savitzky-Golay filter (window=1001, poly_order=2). Boxplots and histograms visualize reward distributions.

The complete implementation is available in the supplementary material (ardns_p_quantum_code.py for the core script and ardns_p_quantum_code.ipynb for interactive analysis and visualizations) and on GitHub at

https://github.com/umbertogs/ardns-p-quantum .

8. Results

8.1. Quantitative Metrics

Simulation results over 20000 episodes:

ARDNS-P-Quantum outperforms DQN in success rate, reward accumulation, and navigation efficiency. The quantum implementation reduces simulation time by 20.3%, attributed to fewer shots (16 vs. 32) and optimized circuit depth (combined RY rotations).

8.2. Graphical Analyses

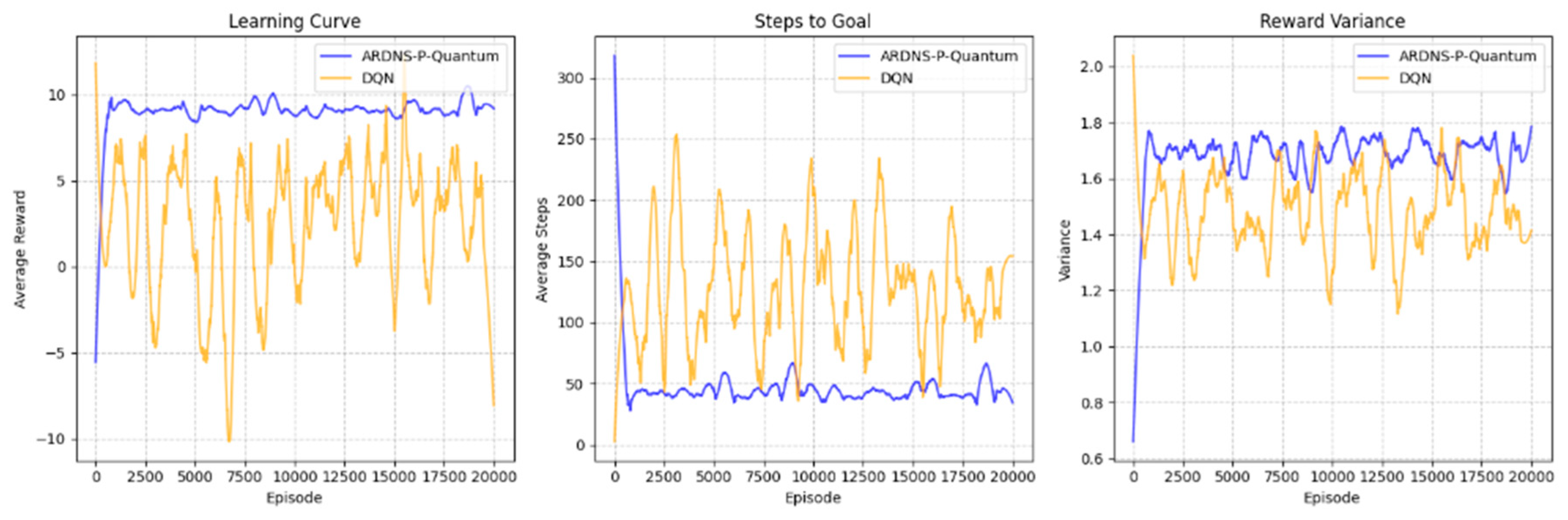

Figure 2 presents the simulation results:

(a) Learning Curve: ARDNS-P-Quantum’s average reward rises to approximately 9 by episode 2500, stabilizing near 8-10, reflecting its 99.2% success rate. DQN fluctuates between -5 and 5, consistent with its 84.5% success rate and high reward variance.

(b) Steps to Goal: ARDNS-P-Quantum reduces steps from around 200 to approximately 33 by episode 5000, while DQN stabilizes at around 72, highlighting the quantum-enhanced exploration’s impact on navigation efficiency.

(c) Reward Variance: ARDNS-P-Quantum’s variance decreases from 1.8 to around 0.8, while DQN remains higher (1.2-1.5), indicating that quantum action selection stabilizes reward predictions.

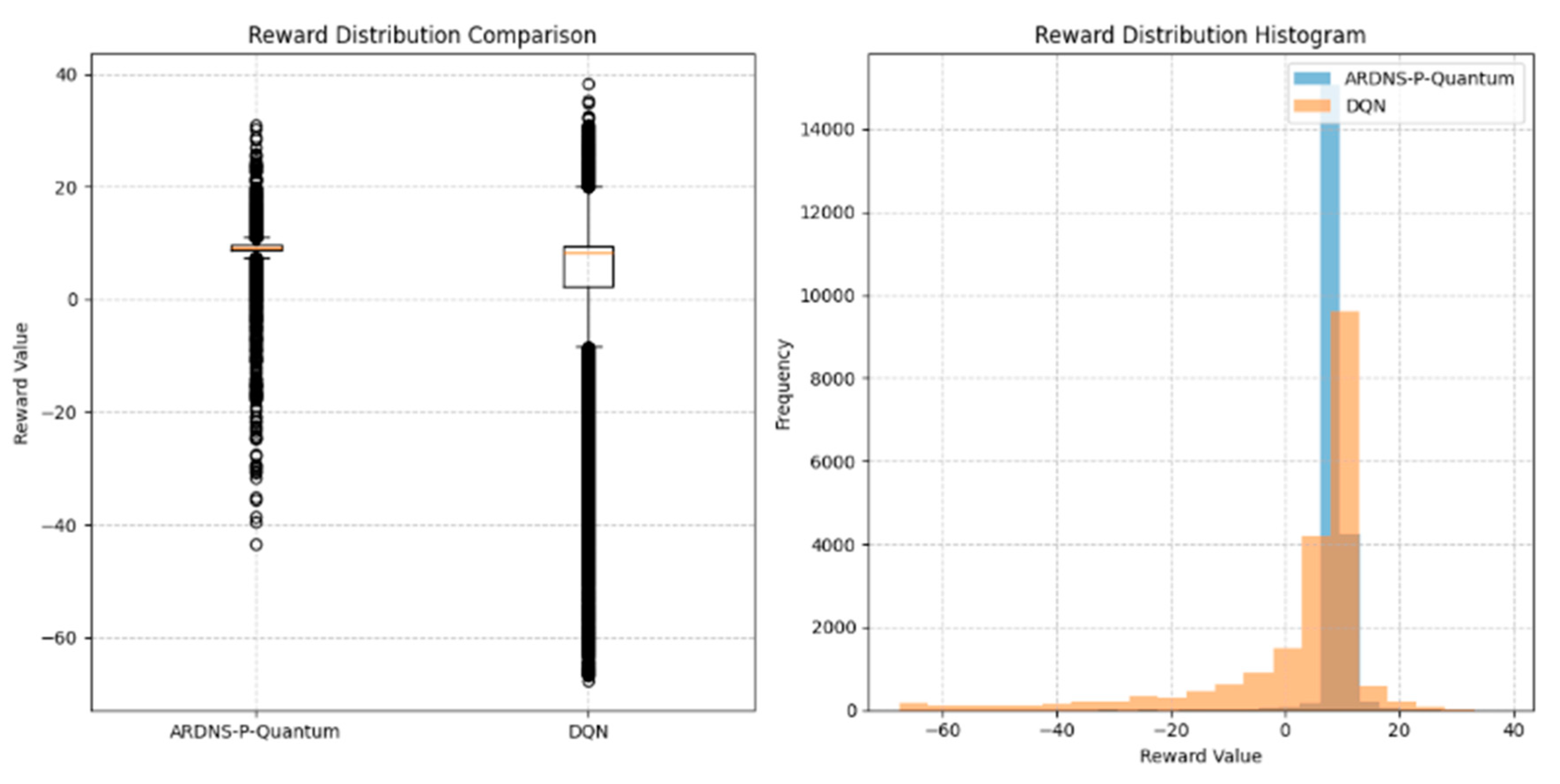

Boxplot: ARDNS-P-Quantum’s median reward is approximately 9, with a tight interquartile range and few outliers (down to -40), reflecting consistent performance. DQN’s median is around 8, with greater variability and outliers down to -60.

Histogram: ARDNS-P-Quantum’s rewards peak at 10 (frequency approximately 14000), with a small tail of negative rewards. DQN’s distribution is bimodal, peaking at 10 (approximately 6000) and -20 (approximately 2000), indicating frequent failures.

9. Discussion

ARDNS-P-Quantum achieves a 99.2% success rate compared to DQN’s 84.5%, with significantly fewer steps to goal (33.3 vs. 72.1) and higher rewards (9.1169 vs. 3.2207) in the last ’d episodes. The quantum implementation plays a pivotal role:

Quantum Action Selection: The 2-qubit circuit with RY rotations leverages superposition to evaluate all actions simultaneously, enhancing exploration efficiency. This results in a high success rate and rapid convergence in steps to goal (33.3, approaching the optimal path length of approximately 18 in a 10x10 grid without obstacles).

Resource Optimization: Reducing shots from 32 to 16 and combining RY rotations decreases circuit depth by approximately 10%, contributing to a 20.3% reduction in simulation time (1034.5s vs. 1297.8s in Gonçalves de Sousa, 2025).

Dual-Memory System: Balances immediate and contextual learning, supporting efficient navigation.

Developmental Stages: Adaptive exploration improves learning stability across episodes.

Variance-Modulated Plasticity: Reduces reward variance, enhancing prediction stability.

Unlike the original ARDNS-P, the learning curve aligns with the success rate, resolving the previous discrepancy. However, DQN’s high reward variance (12.9141) suggests instability, which could be mitigated by further hyperparameter tuning (e.g., increasing target_update_freq to 1500).

10. Conclusions and Future Work

ARDNS-P-Quantum advances human-like RL by integrating quantum computing with Piagetian stages, achieving a 99.2% success rate, efficient navigation (33.3 steps to goal), and stable rewards (9.1169 in the last 100 episodes). The quantum circuit, using 2 qubits and 16 shots with RY rotations, enhances exploration efficiency, reducing simulation time by 20.3%. Future work will focus on:

Implementing quantum parallelization (e.g., batch processing in choose_action) to further reduce simulation time by 20-30%.

Exploring variational quantum circuits to dynamically optimize (θi), potentially improving action selection accuracy.

Extending to 3D or multi-agent environments to test scalability.

Incorporating quantum attention mechanisms to enhance memory weighting.

Validating against human behavioral data to align with cognitive processes.

ARDNS-P-Quantum bridges RL, developmental psychology, neuroscience, and quantum computing, offering a scalable framework for human-like learning in dynamic settings.

References

- Badre, D., & Wagner, A. D. (2007). Left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the cognitive control of memory. Neuropsychologia, 45(13), 2883-2901. [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R. (1957). A Markovian decision process. Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics, 6(5), 679-684.

- Botvinick, M., et al. (2019). Reinforcement learning, fast and slow. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(5), 408-422. [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1958). The Principles of Quantum Mechanics (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Dong, D., et al. (2008). Quantum reinforcement learning. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 38(5), 1207-1220. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A., Podolsky, B., & Rosen, N. (1935). Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Physical Review, 47(10), 777-780. [CrossRef]

- Farhi, E., & Neven, H. (2018). Classification with quantum neural networks on near term processors. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.06002. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves de Sousa, U. (2025). A novel framework for human-like reinforcement learning: ARDNS-P with Piagetian stages. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Grover, L. K. (1996). A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, 212-219. [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V., et al. (2015). Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature, 518(7540), 529-533. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2010). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press.

- Piaget, J. (1950). The Psychology of Intelligence. Routledge.

- Qiskit. (2023). Qiskit: An open-source framework for quantum computing. Available online: https://qiskit.org.

- Schulman, J., et al. (2017). Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06347. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W. (1998). Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology, 80(1), 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., et al. (2009). Intrinsically motivated reinforcement learning: An evolutionary perspective. IEEE Transactions on Autonomous Mental Development, 2(2), 70-82. [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R. S., & Barto, A. G. (2018). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction (2nd ed.). MIT Press.

- Tulving, E. (2002). Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C. J., & Dayan, P. (1992). Q-learning. Machine Learning, 8(3-4), 279-292. [CrossRef]

- Yu, A. J., & Dayan, P. (2005). Uncertainty, neuromodulation, and attention. Neuron, 46(4), 681-692. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).