Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biology of HHV8

3. HHV8-Associated B-Cell Lymphoid Proliferations and Lymphomas

3.1. Primary Effusion Lymphoma (PEL) and Extra-Cavitary Primary Effusion Lymphoma (EC-PEL)

3.2. KSHV/HHV8-Positive Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

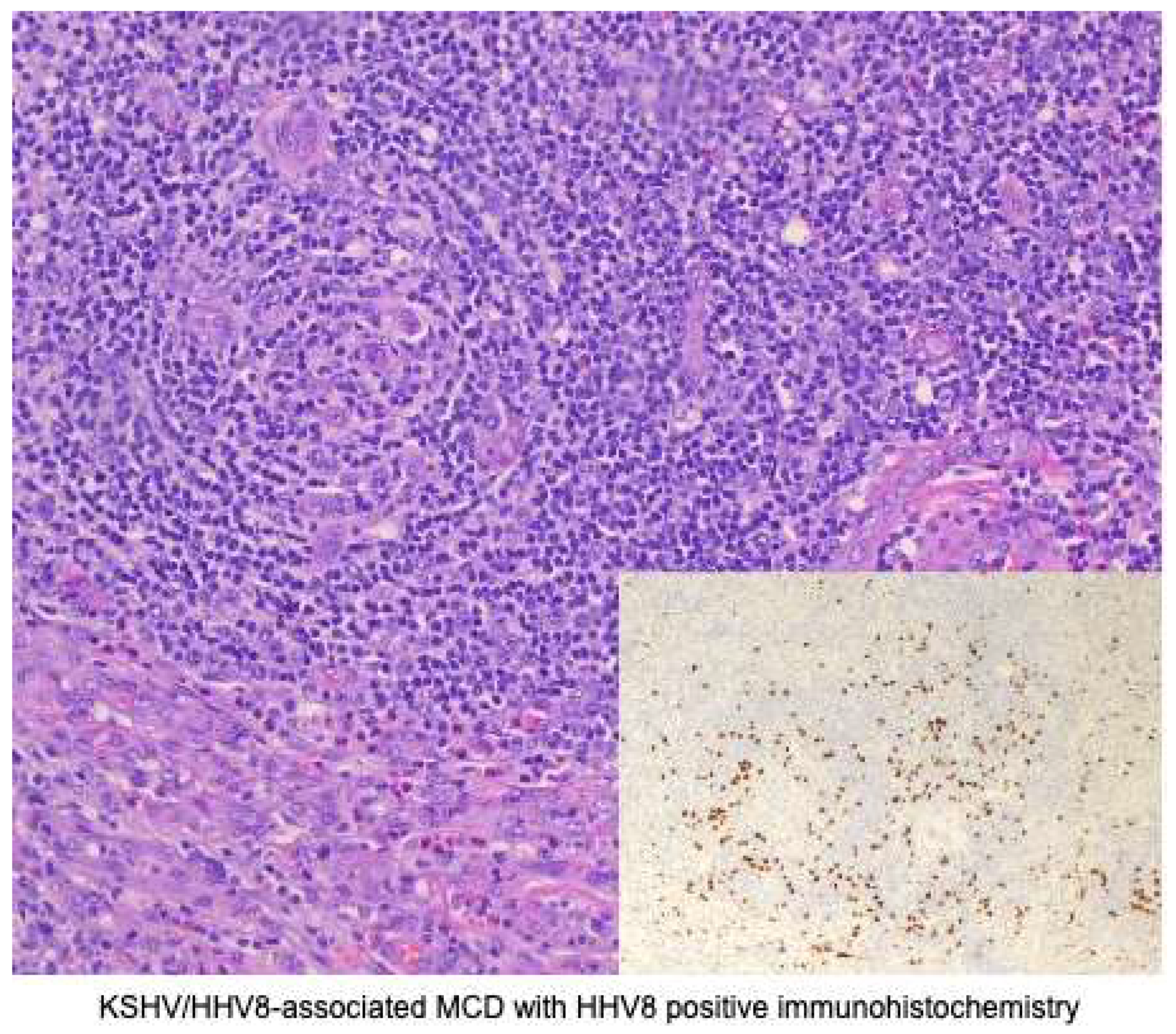

3.3. KSHV/HHV8-Associated Multicentric Castleman Disease (MCD)

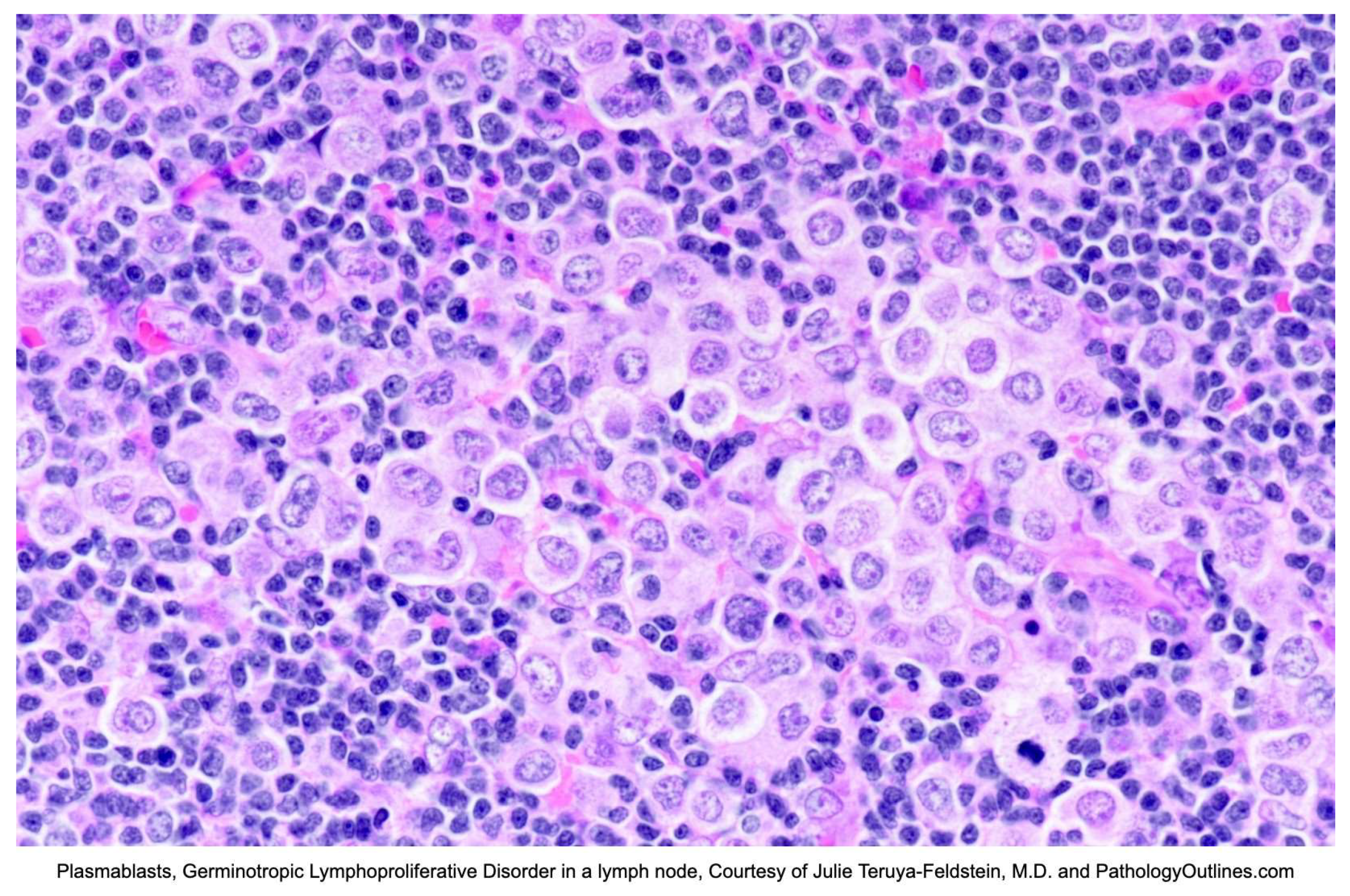

3.4. Germinotropic Lymphoproliferative Disorder (GLPD)

4. Conclusions

References

- Cesarman, E.; Chadburn, A.; Rubinstein, P.G. KSHV/HHV8-mediated hematologic diseases. Blood 2022, 139, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paoli, P. Human herpesvirus 8: an update. Microbes Infect. 2004, 6, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.J.; Bohenzky, R.A.; Chien, M.-C.; Chen, J.; Yan, M.; Maddalena, D.; Parry, J.P.; Peruzzi, D.; Edelman, I.S.; Chang, Y.; et al. Nucleotide sequence of the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 14862–14867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Cesarman, E.; Pessin, M.S.; Lee, F.; Culpepper, J.; Knowles, D.M.; Moore, P.S. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 1994, 266, 1865–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourmishev, L.A.; Dourmishev, A.L.; Palmeri, D.; Schwartz, R.A.; Lukac, D.M. Molecular Genetics of Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus (Human Herpesvirus 8) Epidemiology and Pathogenesis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 175–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappocciolo, G.; Hensler, H.R.; Jais, M.; Reinhart, T.A.; Pegu, A.; Jenkins, F.J.; Rinaldo, C.R. Human Herpesvirus 8 Infects and Replicates in Primary Cultures of Activated B Lymphocytes through DC-SIGN. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 4793–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreal, E.P.; Miller, J.L.; Gordon, S. Ligand recognition by antigen-presenting cell C-type lectin receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2005, 17, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, T.; E Ballestas, M.; Barbera, A.J.; Kelley-Clarke, B.; Kaye, K.M. KSHV LANA1 binds DNA as an oligomer and residues N-terminal to the oligomerization domain are essential for DNA binding, replication, and episome persistence. Virology 2004, 319, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Jeffrey Medeiros, Roberto N. Miranda, Primary Effusion Lymphoma and Solid Variant of Primary Effusion Lymphoma, In Diagnostic Pathology: Lymph Nodes and Extranodal Lymphomas (Second Edition), Elsevier, 2018, Pages 510-517, ISBN 9780323477796. [CrossRef]

- Naresh, K. (2024). KSHV/HHV8-associated B-cell lymphoid proliferations and lymphomas: Introduction. World Health Organization. https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/ chaptercontent/63/173.

- Chadburn, A. , Said, J., Du, M., & Vega, F. (2024). KSHV/HHV8-positive germinotropic lymphoproliferative disorder. World Health Organization. https://tumourclassification.iarc.who. Int/chaptercontent/63/177.

- Du, M.-Q.; Diss, T.C.; Liu, H.; Ye, H.; Hamoudi, R.A.; Cabeçadas, J.; Dong, H.Y.; Harris, N.L.; Chan, J.K.C.; Rees, J.W.; et al. KSHV- and EBV-associated germinotropic lymphoproliferative disorder. Blood 2002, 100, 3415–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanelli, M.; Zizzo, M.; Bisagni, A.; Froio, E.; De Marco, L.; Valli, R.; Filosa, A.; Luminari, S.; Martino, G.; Massaro, F.; et al. Germinotropic lymphoproliferative disorder: a systematic review. Ann. Hematol. 2020, 99, 2243–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Hayakawa, F.; Kiyoi, H. Biology and management of primary effusion lymphoma. Blood 2018, 132, 1879–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said J, Cesarman E. Primary effusion lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2017.

- Gathers, D.A.; Galloway, E.; Kelemen, K.; Rosenthal, A.; Gibson, S.E.; Munoz, J. Primary Effusion Lymphoma: A Clinicopathologic Perspective. Cancers 2022, 14, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, M.L.; Sarid, R. Human herpesvirus 8 and lymphoproliferative disorders. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 10, e2018061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albugami, S.; Al-Husayni, F.; AlMalki, A.; Dumyati, M.; Zakri, Y.; AlRahimi, J. Etiology of Pericardial Effusion and Outcomes Post Pericardiocentesis in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia: A Single- center Experience. Cureus 2020, 12, e6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagristà-Sauleda, J.; Mercè, A.S.; Soler-Soler, J. Diagnosis and management of pericardial effusion. World J. Cardiol. 2011, 3, 135–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna R, Antoine MH, Alahmadi MH, et al. Pleural Effusion. [Updated 2024 Aug 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448189/.

- Chiejina M, Kudaravalli P, Samant H. Ascites. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470482/.

- Zanelli, M.; Sanguedolce, F.; Zizzo, M.; Palicelli, A.; Bassi, M.C.; Santandrea, G.; Martino, G.; Soriano, A.; Caprera, C.; Corsi, M.; et al. Primary effusion lymphoma occurring in the setting of transplanted patients: a systematic review of a rare, life-threatening post-transplantation occurrence. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurain, K.; Polizzotto, M.N.; Aleman, K.; Bhutani, M.; Wyvill, K.M.; Gonçalves, P.H.; Ramaswami, R.; Marshall, V.A.; Miley, W.; Steinberg, S.M.; et al. Viral, immunologic, and clinical features of primary effusion lymphoma. Blood 2019, 133, 1753–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arga, K.Y.; Kori, M. Chapter 10 - Current status of viral biomarkers for oncogenic viruses, Editor(s): Moulay Mustapha Ennaji, Oncogenic Viruses, Academic Press, 2023, Pages 221-252, ISBN 9780128241561. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Pan, Z.; Chen, W.; Shi, Y.; Wang, W.; Yuan, J.; Wang, E.; Zhang, S.; Kurt, H.; Mai, B.; et al. Primary Effusion Lymphoma: A Clinicopathological Study of 70 Cases. Cancers 2021, 13, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega F, Chadburn A. KSHV/HHV8-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. In: de Jong D, Naresh K, et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2022.

- Gonzalez-Farre, B.; Martinez, D.; Lopez-Guerra, M.; Xipell, M.; Monclus, E.; Rovira, J.; Garcia, F.; Lopez-Guillermo, A.; Colomo, L.; Campo, E.; et al. HHV8-related lymphoid proliferations: a broad spectrum of lesions from reactive lymphoid hyperplasia to overt lymphoma. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukswai, N.; Lyapichev, K.; Khoury, J.D.; Medeiros, L.J. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma variants: an update. Pathology 2020, 52, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksenhendler, E.; Boulanger, E.; Galicier, L.; Du, M.-Q.; Dupin, N.; Diss, T.C.; Hamoudi, R.; Daniel, M.-T.; Agbalika, F.; Boshoff, C.; et al. High incidence of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus–related non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients with HIV infection and multicentric Castleman disease. Blood 2002, 99, 2331–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, D.C. Human herpesvirus 8 – A novel human pathogen. Virol. J. 2005, 2, 78–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monini, P.; Colombini, S.; Stürzl, M.; Goletti, D.; Cafaro, A.; Sgadari, C.; Buttò, S.; Franco, M.; Leone, P.; Fais, S.; et al. Reactivation and persistence of human herpesvirus-8 infection in B cells and monocytes by Th-1 cytokines increased in Kaposi's sarcoma. . 1999, 93, 4044–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vega, F.; Miranda, R.N.; Medeiros, L.J. KSHV/HHV8-positive large B-cell lymphomas and associated diseases: a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative processes with significant clinicopathological overlap. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadburn, A.; Said, J.; Gratzinger, D.; Chan, J.K.C.; de Jong, D.; Jaffe, E.S.; Natkunam, Y.; Goodlad, J.R. HHV8/KSHV-Positive Lymphoproliferative Disorders and the Spectrum of Plasmablastic and Plasma Cell Neoplasms. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 147, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.-C.; Fu, P.-A.; Wang, S.-H.; Chang, K.-C.; Hsu, Y.-T. Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma characterized by malignant ascites: A case report. Pathol. - Res. Pr. 2024, 255, 155185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, A.; Schwartz, M.; Van, J.; Owczarzak, L.; Miller, I.; Jain, S. A Challenging Diagnosis of HHV-8-Associated Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Not Otherwise Specified, in a Young Man with Newly-Diagnosed HIV. Am. J. Case Rep. 2024, 25, e945162–e945162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenu, E.M.; Beaty, M.W.; O’neill, T.E.; O’neill, S.S. Cardiac Involvement by Human Herpesvirus 8-Positive Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: An Unusual Presentation in a Patient with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Case Rep. Pathol. 2022, 2022, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angius, F.; Ingianni, A.; Pompei, R. Human Herpesvirus 8 and Host-Cell Interaction: Long-Lasting Physiological Modifications, Inflammation and Related Chronic Diseases. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Cesarman, E.; Spina, M.; Gloghini, A.; Schulz, T.F. HIV-associated lymphomas and gamma-herpesviruses. Blood 2009, 113, 1213–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupin, N.; Diss, T.L.; Kellam, P.; Tulliez, M.; Du, M.-Q.; Sicard, D.; Weiss, R.A.; Isaacson, P.G.; Boshoff, C. HHV-8 is associated with a plasmablastic variant of Castleman disease that is linked to HHV-8–positive plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood 2000, 95, 1406–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Du, Z. Demographic characteristics and prognosis of HHV8-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: Insights from a population-based study with a 10-year follow-up. Medicine 2023, 102, e36464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, V.; Farooq, A. Epidemiological insights and survival patterns of HHV8-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (HDN) associated with multicentric Castleman disease (CD): A comprehensive analysis using SEER database. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e19080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rhee, F.; Fajgenbaum, D. Insights into the etiology of Castleman disease. Blood 2024, 143, 1789–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadburn A, Cesarman E. KSHV/HHV8-associated multicentric Castleman disease. In: Ferry J, Naresh K, et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2022.

- Bower, M.; Carbone, A. KSHV/HHV8-Associated Lymphoproliferative Disorders: Lessons Learnt from People Living with HIV. Hemato 2021, 2, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetica, B.; Pop, B.; Lisencu, C.; Rancea, A.C.; Coman, A.; Cucuianu, A.; Petrov, L. Castleman disease. A report of six cases. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2014, 87, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-W.; Pittaluga, S.; Jaffe, E.S. Multicentric Castleman disease: Where are we now? Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2016, 33, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The spectrum of Castleman’s disease: Mimics, radiologic pathologic correlation and role of imaging in patient management. Madan, Rachna et al. European Journal of Radiology, Volume 81, Issue 1, 123 - 131.

- Abdul-Rahman, I.S.; Al-Amri, A.M.; Ghallab, K.Q. Castleman's Disease: A Study of a Rare Lymphoproliferative Disorder in a University Hospital. Clin. Med. Blood Disord. 2009, 2, CMBD.S2161–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, J. D., & Balakrishna, J., M. D. (2023, October 4). Lymph nodes-inflammatory / reactive disorders: Castleman Disease (E. Courville M. D. & R. N. Miranda M. D., Eds.). Lymph Nodes & Spleen, Nonlymphoma. Retrieved February 1, 2025, from https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lymphnodescastleman.html.

- Carbone, A.; Borok, M.; Damania, B.; Gloghini, A.; Polizzotto, M.N.; Jayanthan, R.K.; Fajgenbaum, D.C.; Bower, M. Castleman disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.M.; Miller, R.F.; Noursadeghi, M.; McNamara, C.; Du, M.; Dogan, A. Pathology of bone marrow in human herpes virus-8 (HHV8)-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 127, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.M. , Miller, R.F., Noursadeghi, M., McNamara, C., Du, M.-Q. and Dogan, A. (2004), Pathology of bone marrow in human herpes virus-8 (HHV8)-associated multicentric Castleman disease. British Journal of Haematology, 127: 585-591. [CrossRef]

- Pria, A.D.; Pinato, D.; Roe, J.; Naresh, K.; Nelson, M.; Bower, M. Relapse of HHV8-positive multicentric Castleman disease following rituximab-based therapy in HIV-positive patients. Blood 2017, 129, 2143–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, M.; Newsom-Davis, T.; Naresh, K.; Merchant, S.; Lee, B.; Gazzard, B.; Stebbing, J.; Nelson, M. Clinical Features and Outcome in HIV-Associated Multicentric Castleman's Disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2481–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaswami, R.; Uldrick, T.S. Remission after rituximab for HHV8+ MCD: what next? Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 5661–5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, R.; Jariwal, R.; Venter, F.; Mishra, S.; Bhandohal, J.; Cobos, E.; Heidari, A. HHV-8-Associated Multicentric Castleman Disease, a Diagnostic Challenge in a Patient With Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Fever. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, M. How I treat HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Blood 2010, 116, 4415–4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacha, D.; Chelly, B.; Kilani, H.; Charfi, L.; Douggaz, A.; Chatti, S.; Chelbi, E. HHV8/EBV Coinfection Lymphoproliferative Disorder: Rare Entity with a Favorable Outcome. Case Rep. Hematol. 2017, 2017, 1578429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, C.; Jain, T.; Kelemen, K. HHV-8-Associated Lymphoproliferative Disorders and Pathogenesis in an HIV-Positive Patient. Case Rep. Hematol. 2019, 2019, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Lim, M.S.; Jaffe, E.S. Pathology of Castleman Disease. Hematol. Clin. North Am. 2018, 32, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEER Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Neoplasm Database. SEER. https://seer.cancer.gov/seertools/hemelymph/5a7d9f261ef55751804cbb20/.

- Castleman Disease Collaborative Network. Treatment - CDCN. CDCN. Published January 22, 2025. https://cdcn.org/treatment/.

- Du, M.-Q.; Diss, T.C.; Liu, H.; Ye, H.; Hamoudi, R.A.; Cabeçadas, J.; Dong, H.Y.; Harris, N.L.; Chan, J.K.C.; Rees, J.W.; et al. KSHV- and EBV-associated germinotropic lymphoproliferative disorder. Blood 2002, 100, 3415–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarman, E.; Chadburn, A.; Rubinstein, P.G. KSHV/HHV8-mediated hematologic diseases. Blood 2022, 139, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, T.; Lee, J.C.; Perner, Y.; Raffeld, M.; Xi, L.; Pittaluga, S.; Jaffe, E.S. KSHV-associated and EBV-associated Germinotropic Lymphoproliferative Disorder. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017, 41, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoneima, A.; Cooke, J.; Shaw, E.; Agrawal, A. Human herpes virus 8-positive germinotropic lymphoproliferative disorder: first case diagnosed in the UK, literature review and discussion of treatment options. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e231640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dpt MALP. Diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma diagnosis. Rare Disease Advisor. Published October 4, 2022. https://www.rarediseaseadvisor.com/disease-info-pages/diffuse-large-b-cell-lymphoma-diagnosis/.

- HHV8 positive DLBCL, NOS. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lymphomaHHV8DLBCL.html.

- Gonçalves, P.H.; Uldrick, T.S.; Yarchoan, R. HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma and related diseases. AIDS 2017, 31, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Xiao, P. Primary Effusion Lymphoma. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2013, 137, 1152–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Leventaki, V.; Bhaijee, F.; Jackson, C.C.; Medeiros, L.J.; Vega, F. Extracavitary/solid variant of primary effusion lymphoma. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2012, 16, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Gloghini, A. PEL and HHV8-unrelated effusion lymphomas. Cancer 2008, 114, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-B.; Rahemtullah, A.; Hochberg, E. Primary Effusion Lymphoma. Oncol. 2007, 12, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, S.; Goto, H.; Yotsumoto, M. Current status of treatment for primary effusion lymphoma. Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2014, 3, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillet, S.; Gérard, L.; Meignin, V.; Agbalika, F.; Cuccini, W.; Denis, B.; Katlama, C.; Galicier, L.; Oksenhendler, E. Classic and extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma in 51 HIV-infected patients from a single institution. Am. J. Hematol. 2016, 91, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primary effusion lymphoma. (n.d.). https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lymphomaeffusion.html.

- Panaampon, J.; Okada, S. Promising immunotherapeutic approaches for primary effusion lymphoma. Explor. Target. Anti-tumor Ther. 2024, 5, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashino, K.; Meguri, Y.; Yukawa, R.; Komura, A.; Nakamura, M.; Yoshida, C.; Yamamoto, K.; Oda, W.; Imajo, K. Primary Effusion Lymphoma-like Lymphoma Mimicking Tuberculous Pleural Effusion: Three Case Reports and a Literature Review. Intern. Med. 2023, 62, 2531–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Goes, V.A.; Cortez, A.C.; Morbeck, D.L.; Costa, F.D.; da Silveira, T.B. The role of autologous bone marrow transplantation in primary effusion lymphoma: a case report and literature review. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2024, 46, S316–S321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narkhede, M.; Arora, S.; Ujjani, C. Primary effusion lymphoma: current perspectives. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 3747–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).