1. Introduction

While most animals appear bilaterally symmetric on the outside, asymmetry can be found in substructures of any size, from the organization of the human brain to neuronal connections and even on the molecular level. The underlying asymmetry of the nervous systems often creates lateralized behavior in the organism, from handedness in humans to differences in perception and processing of stimuli [

1]. These findings are widespread among both vertebrates and invertebrates [

2]. Therefore, it has been theorized that lateralization arose early in evolution and conveys an evolutionary advantage to organisms [

1].

The reason for the development of asymmetry is still unknown, but it is theorized to occur early in embryonic development. While various theories about the exact reason for a development of left-right patterning exist, they typically involve cellular mechanisms causing and/or upholding the break in symmetry [

3]. In multicellular organisms, ranging from plants to nematodes, frogs and even humans, the cytoskeletal component tubulin and associated proteins are considered as the origin of asymmetry [

4]. Additionally, a variety of other mechanisms play an important role in development of asymmetry in some organisms, such as chromatic segregation [

5] and the activity of cilia [

3].

Due to these cellular mechanisms, asymmetry is therefore not only relevant for multicellular organisms but can be found in single cells of metazoan bodies and unicellular organisms as well.

While morphological asymmetry in unicellular organisms has been studied, so far few studies about lateralized movement and behavior exist. The growing trend in basal cognition, the analysis of behavior and learning in aneural organisms, gave rise to a growing number of behavioral experiments on unicellular organisms. These show a wide variety of adaptive mechanisms in multiple species and allow theorizing about the underlying mechanisms of cell cognition [

6]. But, since cellular lateralization seems to be caused by an evolutionary conserved mechanism found in both plants and animals [

7], it is possible that the same mechanism has already been active in the single-celled ancestor of both, and therefore also their other protist relatives. To gain a deeper understanding of basal cognition and cell behavior, behavioral lateralization as a possible influence mechanism has to be considered.

The first experiment on behavioral lateralization in a single-celled organism has been done in

Physarum polycephalum [

8]. The true slime mold

Physarum polycephalum is a unicellular amoeboid organism that consists of a multinucleated cell called plasmodium. This plasmodium can actively move and reorganize itself by extending or retracting pseudopodia, allowing for speeds up to 5cm per hour [

9]. They can grow to up to 900cm², making them easily observable to the naked eye and allowing for a wide variety of behavioral observations [

10]. Despite being a single-celled amoeba,

Physarum has been shown to be capable of finding the shortest paths through mazes [

11], solving complex decision-making paradigms [

12] and even being capable of habituation to aversive stimuli [

13]. It is an important model for research in both aneural intelligence and cell physiology.

In an experiment by Dimonte et al. [

8], small parts of

Physarum were placed in T-mazes. Forced to make a choice, 76% of the plasmodia chose a right turn, with the rest choosing either a left turn or branching into both directions. While the authors state that the mechanism behind laterality in

Physarum remains unknown, they speculate that chiral intracellular structures might play a role in the lateralized movement pattern.

This finding is important, because unlike lateralized animals,

Physarum does not possess a fixed bilaterally symmetrical shape, but instead a formless, constantly shifting mass of pseudopodia. It is, however, consistent with the few findings on intracellular handedness in other unicellular organisms [

14] and learned turning preferences of sperm cells in T-mazes [

15]. Furthermore, while

Physarum itself has no fixed shape, it is capable of linear movement through the formation of tubuli, long vein-like structures for transport of endoplasm. The formation and self-organization of these structures gives the plasmodium a temporary shape that, while not symmetrical, possesses one or more temporary front- and back-ends, not unlike bilaterally symmetrical animals.

To gain insight into the mechanism behind slime mold lateralization, and as a prerequisite to further behavioral experiments, it is vital to look deeper into this phenomenon. We replicated the experiment of Dimonte et al. and investigated the influence various stimuli can have on the lateralized behavior of the slime mold.

Physarum is capable of sensing a wide variety of stimuli. Like most unicellular organisms they respond mainly to chemical stimuli but are far from limited to that. They exhibit both positive and negative phototaxis [

16], seek to maintain an optimal temperature [

17] and tend to move towards gravity [

18]. It has also been found that

Physarum, when kept in a magnetic field, tends to move within the magnetic field lines. This response, however, seems to be dependent on both the strength of the magnetic field and the size of the plasmodium [

19]. Dimonte et al. described that their experiment was conducted in a dark metal enclosure, in a room with no technical equipment, to minimize the influence of other stimuli [

8]. The mazes were kept on a flat surface, all with the vertical channels of the mazes oriented from south to north. Furthermore, the researchers even controlled the medium on which the plasmodia were kept, with one half tested on filter paper and the other half on agar gel. They found no influence of the medium, however.

The data presented in this study were gathered in a series of six experiments aiming to not only replicate the findings of Dimonte et al., but also to assess how various factors may influence the lateralized behavior. Lateralization in T-mazes was tested to investigate the influence of light, magnetic fields, vibration, gravity and genotype. This wide array of experiments provides new important insights into the behavioral complexity of Physarum.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Material

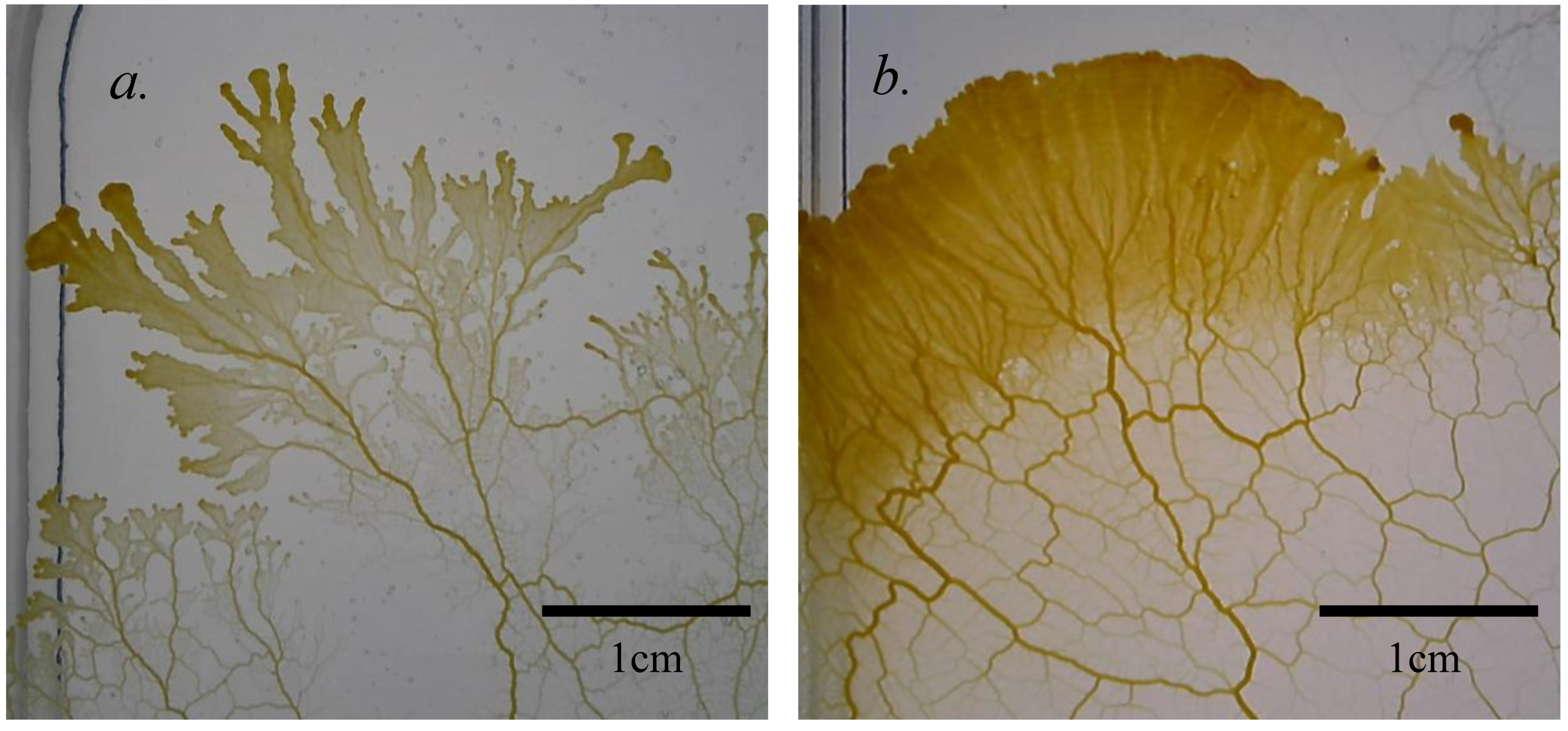

The slime molds used in our experiments were purchased as dried sclerotia. Due to the fast growth and regular division of plasmodia and their genetic uniformity, our slime molds were clones grown from a single plasmodium. To control if laterality might be different among populations, two different clone lines of

Physarum polycephalum were used in the replication: one collected in Germany, another collected in France. After sporulation both were identified as

Physarum polycephalum, despite presenting different phenotypes in their plasmodial stage. The german line was lighter in color, and tended to produce thicker, branching pseudopodia, while the french line moved in more interconnected, fan-like wave-structures (

Figure 1). These morphological differences were stable over months of varied conditions and can therefore be seen as an indicator of different genotypes in different populations of the same species.

A total of 1600 organisms were tested across the six experiments, with over 200 individuals in each experimental setting.

2.2. Experiments

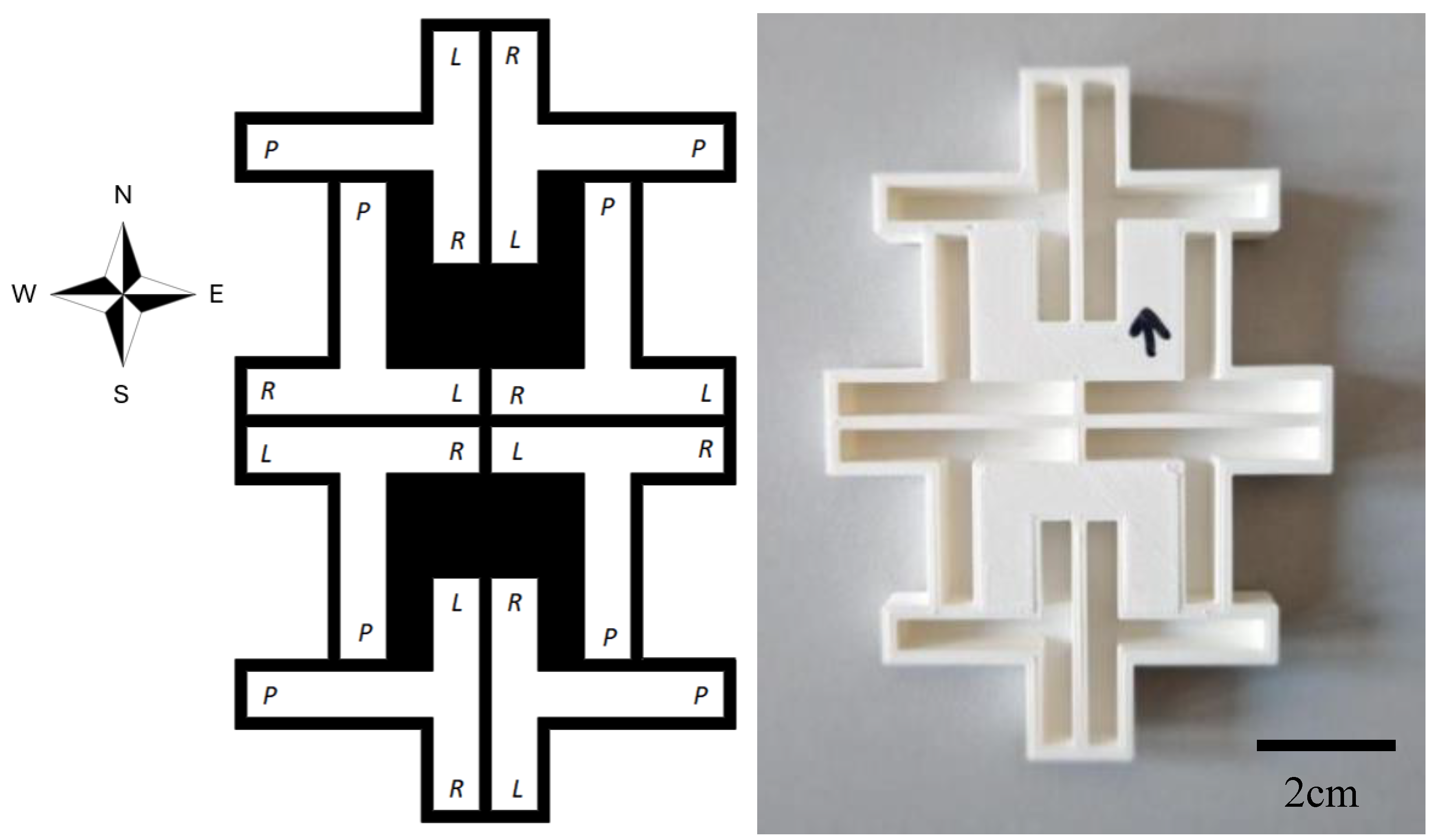

Seven series of tests were conducted in custom designed and 3D-printed T-maze units, comprised of eight individual mazes (

Figure 2). The individual mazes featured a vertical corridor of 5cm length and 0.5cm width, with two arms of 2cm length. Eight individual mazes were combined to form a complex in which two mazes each correspond to a cardinal point

This design allowed for control of external influences, as well as the influence of Earth’s magnetic field, as one side of the maze-complex was aligned to the north via a compass. The ground of the mazes was covered in 2%-water-agar without nutrients to supply water to the plasmodia. While Dimonte et al. used filter paper as well, they found no significant difference between these two media [

8], therefore in our experiment agar was used as the sole medium. These maze-complexes were placed in square Petri-dishes filled with water to keep humidity constant. For recording purposes, the mazes were placed on a LED lighting plate, illuminating the mazes from below with diffuse, white light at a low intensity of 200 Lux. From the literature it is known that this used light intensity and spectrum do not influence the slime mold [

20]. This allowed for constant filming of the slime molds via a document camera at a rate of one picture every ten minutes, allowing for constant documentation without disturbing the slime mold. This experimental setup was placed in an enclosed wooden box for the duration of each experiment to keep out external light and other external influences; the box itself was kept in a room where temperature was kept constant at 20°C. Every individual plasmodium was tested for 48 hours, allowing them to fully move through the mazes.

Pre-tests were conducted to determine the proper cell mass for the experiments. Since Physarum is capable of lateral splitting and spreading both ways in a T-maze, different cell masses were tested to determine a cell size incapable of splitting. Beginning with 20mg, the mass was successively reduced to 1mg, which was deemed to be both still viable for survival, but only rarely led to splitting. Therefore, in the main experiments all slime molds had an initial cell mass of circa 1mg.

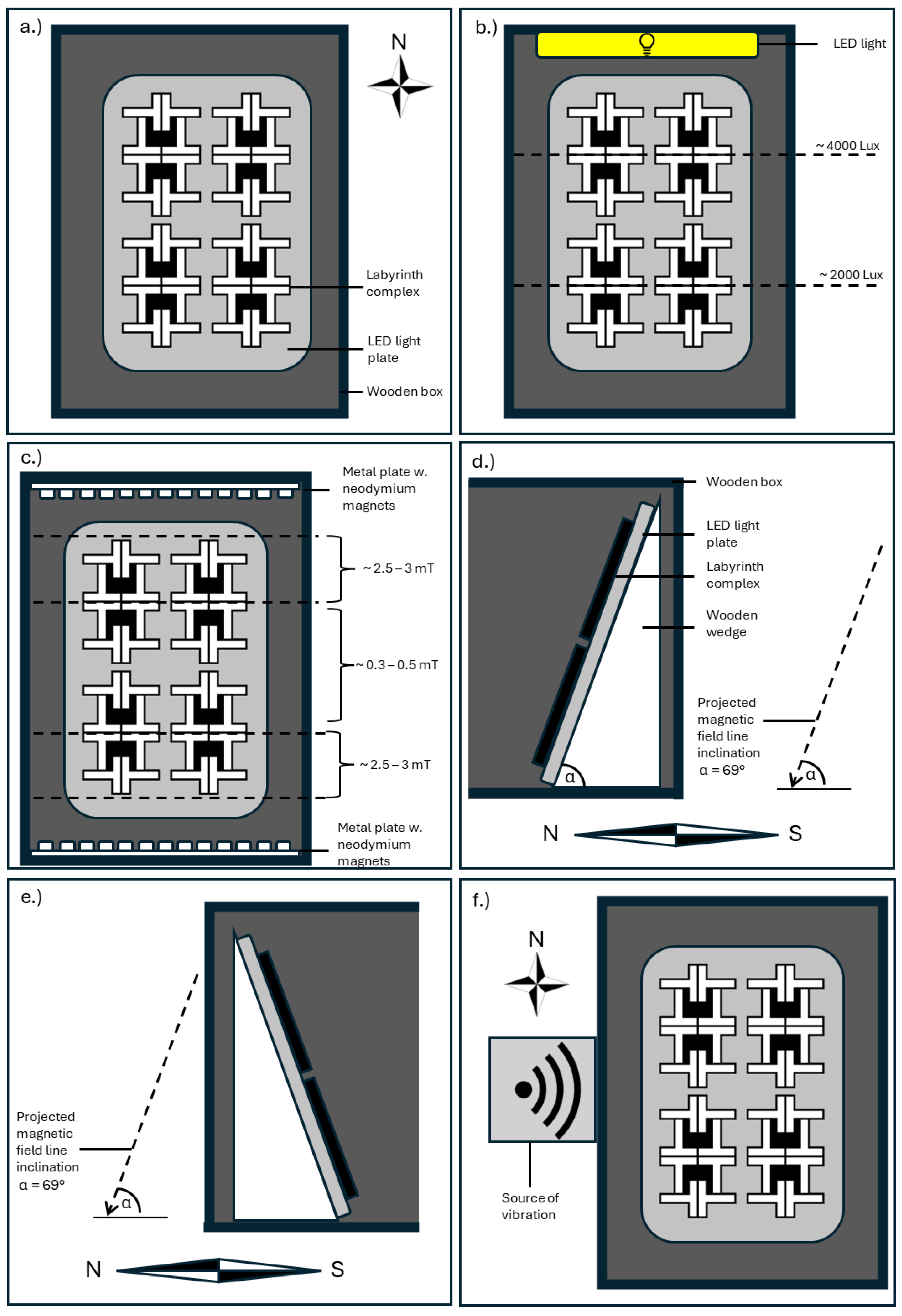

The 7 different experimental setups are illustrated in

Figure 3, and consisted of the following variants:

1 Replication of published experiments. Experiment 1 was conducted under the described conditions without any additional stimuli, in order to replicate the experiment by Dimonte et al. [

8]. For this experiment, the third and all latter experiments, clones of a plasmodium collected in Germany were used.

2 Genotype influence. To control for the influence of the genotype on behavioral lateralization, for the second experiment a clone line collected in France was used. Otherwise, the experimental conditions were kept the same as in Experiment 1.

3 Phototaxis. Experiment 3 was used to explore the influence of light on laterality. An LED light producing white light was affixed to the north side of the box at a height of 26 cm and indexed a light gradient from 4000 to 2000 Lux. For the first row of maze complexes the incident angle comprised 55° measured in the middle of the complex. Second row maze complexes were illuminated in an incident angle of 40°. Due to the different angles, the resulting shadow patterns were dissimilar, and the mazes were evaluated separately.

4 Magnetotaxis. Experiments 4 and 5 aimed at further exploring the influence of magnetic fields on

Physarum behavior. Shirakawa et al. have previously shown that

Physarum movement tends to align with magnetic field lines under certain conditions [

19]. For Experiment 4 an artificial magnetic field was created utilizing 160 neodymium magnets (N48, axial magnetization, 3 mm diameter with a layer of Ni-Cu-Ni), which were placed on the north and south side of the T-mazes. Due to the decline in magnetic strength, a gradient with a minimum of zero and a maximum of 3 mT formed, as measured with a gaussmeter. T-mazes positioned in the middle of the setting were separately evaluated as group with a low magnetic field of 0.3 - 0.5 mT, the margin mazes as group with a moderate magnetic field from 2.5 to 3 mT.

5 Inclination. Experiment 5 investigated the influence of Earth’s magnetic field. While the maze-complexes were already aligned with the cardinal directions, with one fourth of all mazes facing directly north, the angle at which the magnetic field lines of the Earth intersect the surface varies between the equator and the poles. At the location of the lab in Northern Germany, the inclination angle is 69°. To control for this, a wedge was inserted to allow for a placement of the maze complexes at a 69° inclination angle. The wedge was orientated towards north (declining) and south (ascending).

6 Gravitaxis. While the setup of Experiment 5 allowed for better alignment with Earth’s magnetic field, it also did not allow to separate movement towards north from movement downwards. Since Physarum is known to exhibit gravitaxis, a sixth experiment was conducted to control for the effects of gravity. For this purpose, the wedge used in Experiment 5 was rotated by 180°, to maintain the same angle towards the ground but separate the effect of gravity on movement from the effect of magnetic field lines.

7 Vibration. For Experiment 7, the same setup was used as in Experiments 1 and 2. Additionally, in the west next to the experimental box, a vibration motor ran permanently at 300 Hz. To keep the motor from moving erratically and to instead distribute the vibration equally, the motor was encased in agar, creating a vibration propagating on the same table as the experiment. Previous observations in our lab suggest that Physarum reacts to vibration stimuli.

2.3. Data Analysis

Video material was evaluated manually by the authors and coded according to a predefined scheme. Included were the decisions for only one arm, while lateral splitting into both arms was excluded (16.1% among all experiments). A trial was deemed finished when the plasmodium reached at least half of an arm’s length. For all experiments, p-values have been calculated with two-tailed binomial tests with a 0.5 success value.

3. Results

The results for all experiments, grouped by decision between left and right, can be found in

Table 1.

Table 2 shows the results of choice between cardinal directions. Overall, we found significant evidence for laterality in

Physarum when confronted with external stimuli but mostly not without it.

In Experiment 1, which was conducted without external stimuli, Physarum showed no overall systematic preference for left or right, except for one test showing a significant tendency (p = .04) to turn left (north) when starting towards east. While non-significant, the tendency to go north is mirrored in mazes starting west. Overall, Experiment 1 showed a significant preference for going north (p = .008). This preference is not found in Experiment 2 on the other clonal line however, which shows no significant preference for any direction.

Experiment 3, concerning phototaxis, revealed a significant movement towards the right side of the maze when starting towards south. Under weak light, Physarum showed a tendency to move away from the light to the left when starting towards the west (p = .014), but interestingly not when starting towards east (p = .678). Overall, a marginally significant preference for moving south inside the magnetic field could be observed (p = .068).

Experiment 4, concerning magnetotaxis, shows mixed results for strong and weak magnetic fields. In strong magnetic fields, an overall tendency to turn left is observed for all cardinal directions together (p = .024), although the effect is not strong enough to manifest on the level of any single cardinal direction. In weak magnetic fields, significant preferences for going left (north) when starting towards west (p = .024) and for going right (north) when starting towards east were found (p = .008), as well as a preference for choosing right (east) when starting from the north (p = .004).

In Experiment 5, using inclination, a clear preference for spreading towards north can be seen both in the overall cardinal direction choice (p < .001) as well as in the mazes starting towards west (p = .008) and east (p = .044). Moving north corresponds to moving downwards in this setup. Experiment 6, in which the setup was rotated, shows a similar preference for moving south instead, both in the overall cardinal directions (p < .001) as well as in the mazes starting towards west (p < .001) and east (p = .002), again moving downwards. The strong downward movement regardless of cardinal direction implies a reaction to gravity, rather than to Earth’s magnetic field lines. Additionally, a significant preference for turning left when starting towards south was observed (p = .046), together with an overall preference for turning left (p = .040).

In Experiment 7, testing for the effects of vibration, it was found that when given the chance, Physarum moved significantly more often west towards the vibration (p < .001). Furthermore, in all mazes Physarum showed a significant preference to turn left rather than right regardless of the relative position of the source of the vibration, showing true lateralized movement under this condition.

4. Discussion

While behavioral lateralization is a well-studied phenomenon in multicellular animals, it has rarely been studied in unicellular organisms. The first study on lateralized movement in the true slime mold

Physarum polycephalum by Dimonte et al. showed a preference for moving right in 75% of the tested plasmodia [

8]. To investigate this phenomenon further, we aimed to replicate this experiment and investigated the effects of genotype and external stimuli such as light, magnetic fields, gravity and vibration. Our results suggest that the origin of lateralized movement in

Physarum is far more complex than previously thought. While no lateralization was found without stimulus, we showed that side preferences in T-mazes and even true lateralized movement can be induced by various external stimuli.

4.1. Experiment 1 and 2: Lateralized Movement and the Influence of the Genome

Experiment 1 and Experiment 2, which were aimed at replicating the results of Dimonte et al. [

8], led to very different results. The clear lateralization to the right observed in the previous experiments were not observed in our two different clonal lines. Instead, both lines showed no preference for either direction. We found, however, a distinct preference for going north in one clonal line but not the other, showcasing that clonal lines of the same species can show not only differing morphology, but different behavior as well. While Dimonte et al. did not disclose the origin of their clonal line, it is highly probable that they used a different line from the ones used in this study.

Physarum polycephalum is found in a wide geographical range spanning multiple continents [

21] and reproduces sexually and therefore features a high genetic variety between populations. While it has not yet been studied in

Physarum, a high genetic variety even within populations has been found in the related species

Didymium difforme [

22]. Behavioral differences between populations or clonal lines in

Physarum are yet to be studied in detail, but comparison between our data and the results of Dimonte et al. suggest that differences among genotypes might influence plasmodial movement preferences. This is also supported by the fact that the findings of Experiment 1 are in line with the findings of Shirakawa et al. [

19], showing that small

Physarum fragments seemingly even react to weak magnetic fields like Earth’s, while the findings of Experiment 2 are not. Since both experiments were conducted at the same place under the same circumstances with the only difference between them being the clonal lines used, it is possible that one clonal line is more sensitive to magnetism than the other. Regarding lateralized behavior, it would mean that the cellular mechanisms producing lateral preferences in movement are far from universal in

Physarum. It is possible that lateralization in

Physarum might therefore not arise from the same preserved mechanisms found in many organisms but rather represent different genetically encoded foraging strategies. In line with this hypothesis, Dussutour et al. report different, stable foraging strategies between individual plasmodia [

23].

4.2. Experiment 3: Phototaxis

Overall, the results of Experiment 3 do not show a systematic effect of light on lateralization in

Physarum. Both higher and lower light intensities did not lead to lateralized movement, except for a slight overall tendency to move right when starting towards the south, and, under lower light intensity, a preference for moving left (away from the light) when starting towards west. When starting towards the east, no similar preference can be seen. These results don’t indicate a systematic reaction to light, and, given the smaller sample sizes, might be due to chance observations. It must be mentioned that, to create a gradient, the light had to be mounted to the side of the mazes and therefore reached the slime molds at an angle of 55° for the mazes closer to the light and 40° in those farther away. While the angle of light should play no major role in the phototaxis of

Physarum [

24], it created shadows inside the mazes and therefore may have allowed for light evasion of the plasmodia even without displaying clear photophobic movement. In comparison to Experiment 1, it must also be noted that the observed preference for moving north was not observed here. Another explanation might be that the positive magnetotaxis and negative phototaxis of

Physarum may have been in conflict and therefore caused this indecisive behavior.

4.3. Experiment 4: Magnetotaxis

The results for this experiment show a great influence of magnetic fields depending on field strength. In the weak magnetic field from north to south, given the choice,

Physarum preferred to move north. This orientation within the weak magnetic field is in accordance with the findings of Shirakawa et al. [

25].

Physarum starting towards north also significantly more often chose to turn right when forced to decide, however, no similar effect could be observed in

Physarum starting towards south. Contrastingly, the strong magnetic field gave rise to an overall lateralized movement in

Physarum, with a preference for moving right over all mazes, regardless of cardinal direction. Interestingly, this mirrors the results of Dimonte et al., despite them not having applied magnetic fields. Therefore, while our

Physarum clone line did not show initial lateralized movement towards the right, it could be induced by strong magnetic fields. On the other hand, the weak magnetic field seemed to induce lateralized movement towards the left in one maze type. Shirakawa et al. report that the direction of magnetotaxis reverses depending on the strength of the magnetic field [

19]. In our experiment, the induced lateralization seems to reverse correspondingly. Furthermore, in weak magnetic fields the magnetotaxis seems to be stronger than the lateralization, and it is possible that under both conditions magnetotaxis and induced lateralization are influence and/or overlap each other. If, as the results suggest, induced lateralization is dependent on magnetic field strength, future studies testing in even stronger magnetic fields could lead to the observation of more pronounced lateralized movement. The mechanism behind this induced lateralization is yet to be investigated. One possible explanation might lie in the actomyosin-complex that forms the internal structures of the plasmodial cytoskeleton. The Ca+-activated rhythmic disorganization and reorganization induces changes in rigidity of the cell, therefore inducing oscillation and allowing for movement through the extension of pseudopodia [

26]. A recent study shows, albeit in rat muscle cells, that weak magnetic fields alter the actin polymerization and therefore cytoskeleton dynamics [

27]. Since the actomyosin-complex dynamic is the mechanism behind plasmodial movement, it is possible to hypothesize that altering the molecular dynamics alters the resulting movement as well, resulting in atypically lateralized movement.

4.4. Experiment 5 and 6: Inclination

The experiments concerning inclination were done to investigate the effect of truly aligning the mazes with Earth’s magnetic field. In this regard, in Experiment 5 a very clear influence of the stimulus on the behavior was observed, as plasmodia chose north (down) over south (up) when given the opportunity, while otherwise not showing lateralized movement. Experiment 6, however, makes clear that this effect is probably not due to magnetotaxis, but rather to gravitaxis: After rotating the setup, Physarum preferred moving south (down) instead of north (up). Therefore, while Experiment 1 shows a preference for moving north, it seems probable that gravity has a stronger influence in Physarum taxis choices.

4.5. Experiment 7: Vibration

The results of Experiment 7 reveal two previously unknown behaviors in

Physarum. First, it shows that plasmodia, given the choice to move towards or away from the source of vibration, significantly prefer to move towards it. This behavior has not been reported before, and therefore no current theories to explain it exist in literature. A possible explanation could be linked to the fact that

Physarum polycephalum feeds on fungal spores and decaying fungal fruiting bodies [

28], and fungal fruiting bodies emit weak vibrations as they grow. Therefore, moving towards vibration might be part of

Physarum’s natural foraging strategies. For another explanation, it must be considered that the behavior of

Physarum is mainly a result of its complex internal network oscillations, created by contraction and relaxation of the cell membrane, thereby moving cytoplasm throughout the cell and guiding movement through expansion [

26]. This complex oscillatory system reacts to various stimuli relevant to the organism, such as sources of food or harmful stimuli, but may also be disrupted by external forces or even by the stiffness of the substrate the cell is moving on [

29]. While more research is needed to determine if this behavior is ecologically plausible or the effect of a disruption of

Physarum’s internal oscillatory system, the fact that those organisms starting towards west and east, with no choice to move towards or away from the source of vibration, both showed lateralized movement towards left regardless of the source of vibration, leads us to assume that vibration alters the oscillatory state and therefore behavior as a whole.

5. Conclusions

Our results show that, to discuss lateralization in

Physarum, we need to distinguish between a general lateralization of a population, stimulus-dependent directional choices and stimulus-induced general lateralized movement. In our experiments, stimulus-dependent directional choices were the most prevalent behavior of the plasmodia. Only through the T-maze complex design used, where plasmodia start towards four different cardinal directions, were we able to determine that some movement occurred relative to the position of a stimulus. Therefore, we argue that, if all plasmodia always start towards the same direction, the reaction to an unknown stimulus might produce seemingly lateralized movement in T-mazes. Furthermore, plasmodia seem to be very sensitive to some stimuli, and it is quite possible that not all stimuli influencing movement have been discovered. While magnetotaxis in

Physarum has been described for the first time in 2012 [

19], to the best of our knowledge, the active movement towards a source of vibration has, not yet been described in literature. We show that one clonal line seems to be more sensitive to magnetic fields than the other, implying individual differences in sensitivity and possibly even preferences among different genotypes. Thus, further studies of

Physarum movement, both regarding lateralization and other movements such as taxis and preferences, should include robust controls, even down to the genotype, to produce reliable results. Taking the new findings of the present study, it is possible that the observations of Dimonte et al. might have been the result of (an) unknown stimuli(us). We argue that

Physarum, as a formless organism, does not show general lateralization in a stimulus-free environment. While the cytoskeletal mechanisms for lateralization in other eukaryotic organisms might be evolutionary preserved among many taxa, they do not necessarily have to be preserved in

Physarum as well. The cytoskeletal structure of the Amoebozoa is different from that of other eukaryotes with an unexpected complexity of microtubule-structures, allowing for their unique modes of locomotion [

30]. Therefore, we assume that

Physarum and possibly other Amoebozoa did not preserve these mechanisms and therefore do not show lateralized movement, or if they do, possibly not for the reasons other eukaryotes do.

This, in turn, raises the question of induced lateralization. Both strong magnetic fields and vibration were able to induce a preference for moving left in

Physarum, seemingly regardless of the position of the stimulus. Furthermore, while Dimonte et al. [

8] describe zig-zag-movements and corresponding structures in the tubuli of their plasmodia, in our experiments these were mostly observed under strong magnetic fields and vibrations. In all our other experiments we observed only longer, straight tubuli. Both stimuli generally do not occur in the natural environment, and for that reason may exert a marked influence on the internal systems of

Physarum, especially the Ca2+-driven rhythmic disorganization and reorganization of actomyosin-complexes as the mechanism behind oscillation and movement. The zig-zag-pattern might be the result of induced instability in the reorganization, or a disturbance of the rhythm due to the magnetic field influencing the flow of calcium-ions. Lastly, induced laterality may be the result of stress and general disorientation of the plasmodium due to stimulus-intensity, making it more likely to retreat into behavioral heuristics such as behavioral lateralization and disoriented movement. Overall, the mechanism behind induced lateralization remains to be further explored.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.; methodology, J.F. and R.G.; software, J.F and R.G.; validation, J.F; formal analysis, J.F.; investigation, R.G.; resources, J.F. and R.G.; data curation, J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.; writing—review and editing, J.F. and R.G.; visualization, J.F.; supervision, J.F.; project administration, J.F.; funding acquisition, J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Jannes Freiberg is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German research foundation) under the project SFB 1461, Project-ID 434434223.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank very specially Dr. Alexandra Cordeiro-Baumgartner for sharing her knowledge, Prof. Rainer Adelung for inspiring a slime mold project and Prof. Christian Kaernbach for his continued support and patience.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rogers LJ, Vallortigara G (2015) When and Why Did Brains Break Symmetry? Symmetry 7:2181–2194. [CrossRef]

- Frasnelli E, Vallortigara G, Rogers LJ (2012) Left–right asymmetries of behaviour and nervous system in invertebrates. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 36:1273–1291. [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg LN, Levin M (2013) A unified model for left–right asymmetry? Comparison and synthesis of molecular models of embryonic laterality. Developmental Biology 379:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Lobikin M, Wang G, Xu J, et al (2012) Early, nonciliary role for microtubule proteins in left–right patterning is conserved across kingdoms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109:12586–12591. [CrossRef]

- Sauer S, Klar AJS (2012) Left-right symmetry breaking in mice by left-right dynein may occur via a biased chromatid segregation mechanism, without directly involving the Nodal gene. Frontiers in Oncology 2:. [CrossRef]

- Lyon P, Keijzer F, Arendt D, Levin M (2021) Reframing cognition: getting down to biological basics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 376:20190750. [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg LN, Lemire JM, Levin M (2013) It’s never too early to get it Right: A conserved role for the cytoskeleton in left-right asymmetry. Communicative & Integrative Biology 6:e27155. [CrossRef]

- Dimonte A, Adamatzky A, Erokhin V, Levin M (2016) On chirality of slime mould. Biosystems 140:23–27. [CrossRef]

- Aldrich H (2012) Cell Biology of Physarum and Didymium V1: Organisms, Nucleus, and Cell Cycle. Elsevier.

- Reid CR (2023) Thoughts from the forest floor: a review of cognition in the slime mould Physarum polycephalum. Animal Cognition 26:1783–1797. [CrossRef]

- Nakagaki T, Yamada H, Tóth Á (2000) Maze-solving by an amoeboid organism. Nature 407:470–470. [CrossRef]

- Dussutour A, Latty T, Beekman M, Simpson SJ (2010) Amoeboid organism solves complex nutritional challenges. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107:4607–4611. [CrossRef]

- Boisseau RP, Vogel D, Dussutour A (2016) Habituation in non-neural organisms: evidence from slime moulds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 283:20160446. [CrossRef]

- Frankel J Intracellular Handedness in Ciliates. In: Ciba Foundation Symposium 162 - Biological Asymmetry and Handedness. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp 73–93.

- Brugger P, Macas E, Ihlemann J (2002) Do sperm cells remember? Behavioural Brain Research 136:325–328. [CrossRef]

- Hato M, Ueda T, Kurihara K, Kobatake Y (1976) Phototaxis in True Slime Mold Physarum polycephalum. Cell Structure and Function 1:269–278. [CrossRef]

- Wolf R, Niemuth J, Sauer H (1997) Thermotaxis and protoplasmic oscillations in Physarum plasmodia analysed in a novel device generating stable linear temperature gradients. Protoplasma 197:121–131. [CrossRef]

- Wolke A, Niemeyer F, Achenbach F (1987) Geotactic behavior of the acellular myxomycete Physarum polycephalum. Cell Biology International Reports 11:525–528. [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa T, Konagano R, Inoue K (2012) Novel taxis of the Physarum plasmodium and a taxis-based simulation of Physarum swarm. In: The 6th International Conference on Soft Computing and Intelligent Systems, and The 13th International Symposium on Advanced Intelligence Systems. IEEE, Kobe, Japan, pp 296–300.

- Nakagaki T, Umemura S, Kakiuchi Y, Ueda T (1996) Action Spectrum for Sporulation and Photoavoidance in the Plasmodium of Physarum polycephalum, as Modified Differentially by Temperature and Starvation. Photochemistry and Photobiology 64:859–862. [CrossRef]

- Mayne R (2016) Biology of the Physarum polycephalum Plasmodium: Preliminaries for Unconventional Computing. In: Adamatzky A (ed) Advances in Physarum Machines: Sensing and Computing with Slime Mould. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 3–22.

- Winsett KE, Stephenson SL (2011) Global distribution and molecular diversity of Didymium difforme. Mycosphere 2:135–146.

- Dussutour A, Ma Q, Sumpter D (2019) Phenotypic variability predicts decision accuracy in unicellular organisms. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 286:20182825. [CrossRef]

- Häder D-P, Schreckenbach T (1984) Phototactic Orientation in Plasmodia of the Acellular Slime Mold, Physarum polycephalum. Plant and Cell Physiology 25:55–61. [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa T, Sato H, Muro M, et al (2020) Magnetotaxis of the Physarum Plasmodium and Construction of a Magnetically Controlled Physarum Logic Gate. International Journal of Unconventional Computing 15:245–258.

- Boussard A, Fessel A, Oettmeier C, et al (2021) Adaptive behaviour and learning in slime moulds: the role of oscillations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 376:20190757. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami A, Tanaka LY, Massucatto RC, et al (2024) Automated 1D Helmholtz coil design for cell biology: Weak magnetic fields alter cytoskeleton dynamics.

- Rojas C, Stephenson SL (2021) Myxomycetes - Biology, Systematics, Biogeography and Ecology, 2nd ed. Academic Press.

- Murugan NJ, Kaltman DH, Jin PH, et al (2021) Mechanosensation Mediates Long-Range Spatial Decision-Making in an Aneural Organism. Advanced Materials 33:2008161. [CrossRef]

- Tekle YI, Williams JR (2016) Cytoskeletal architecture and its evolutionary significance in amoeboid eukaryotes and their mode of locomotion. Royal Society Open Science 3:160283. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).