Submitted:

12 April 2025

Posted:

17 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Study Participants

| Age | 29 +- 2.1 years |

| Height | 1.78+-3.5cm |

| Weight | 75.4 +- 2.9kg |

| BMI | 22.3 +- 1.98 |

| % Fat | 14.5 +- 1.1 |

| Professional years | 7.9 years |

2.2. Procedures

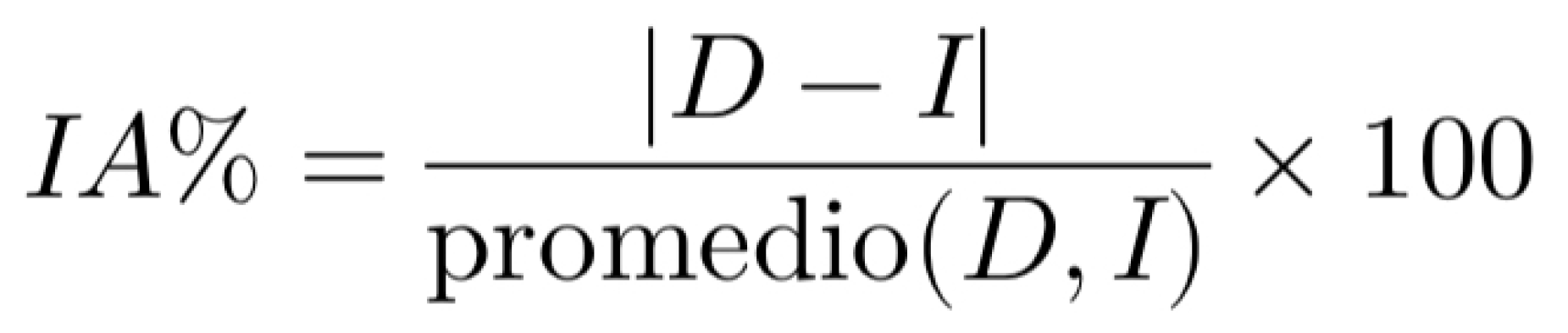

2.3. Statistic Analysis

3. Results

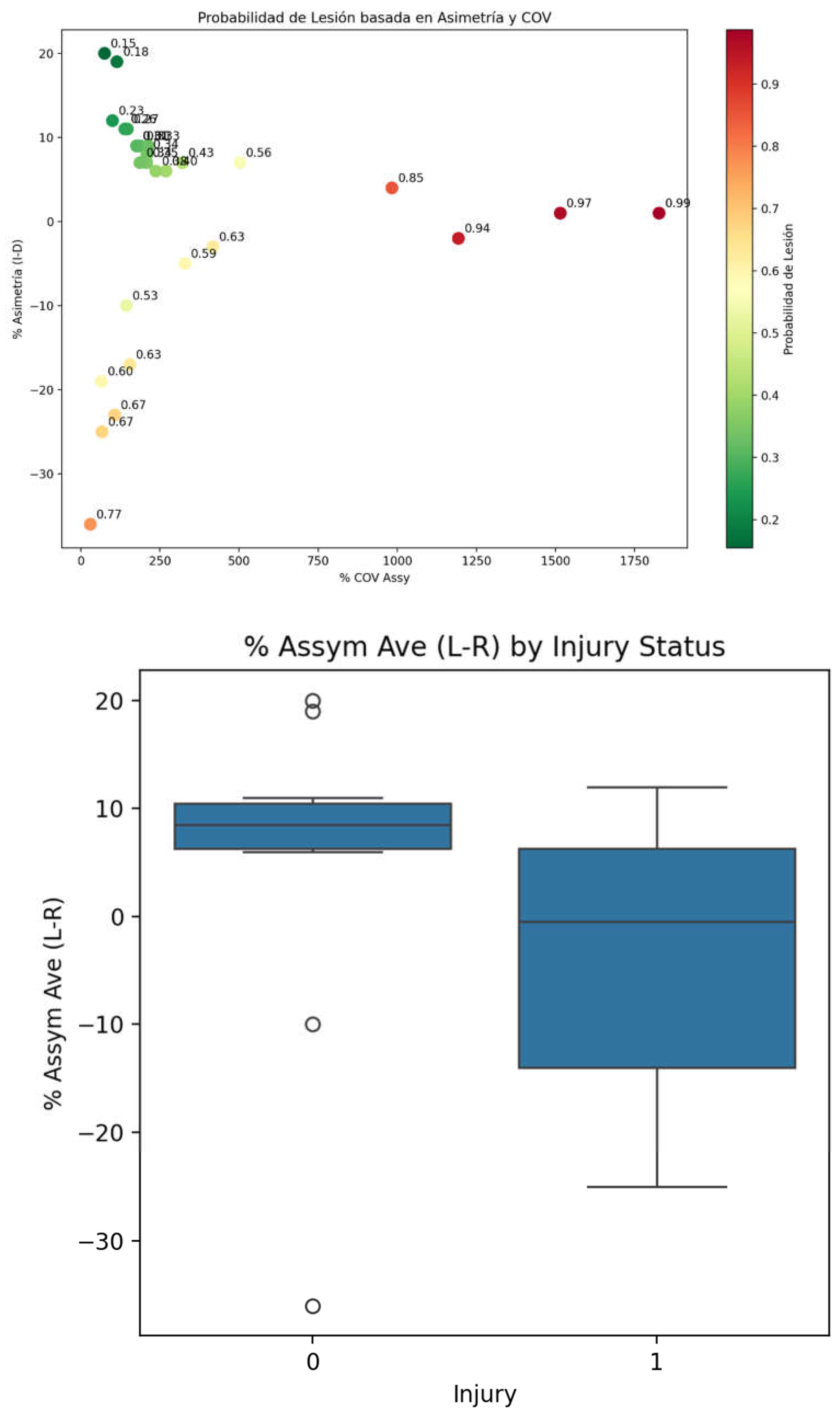

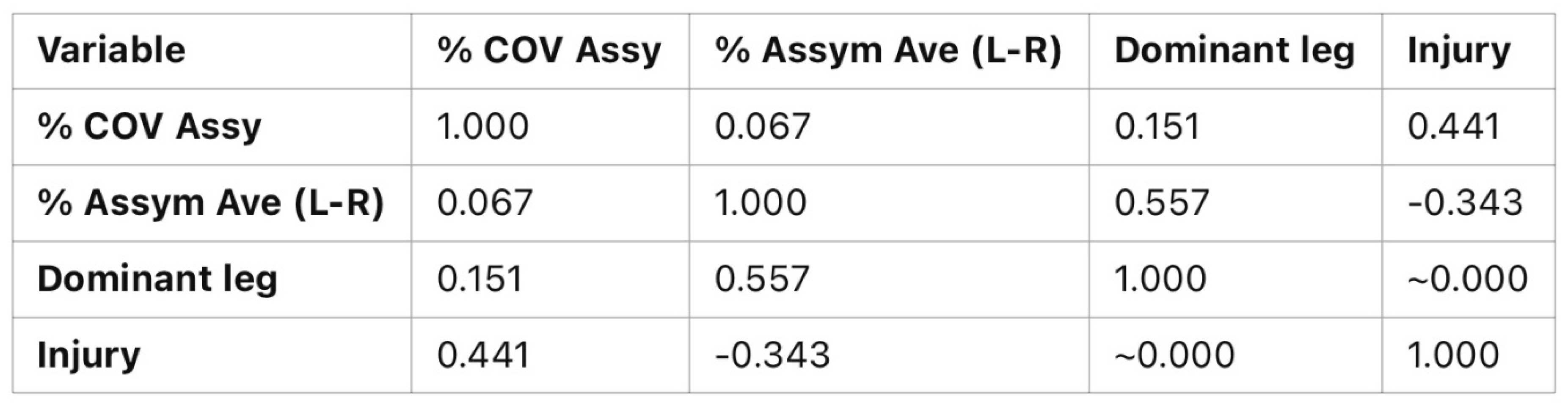

3.1. % Peak Landing Force Asymmetry

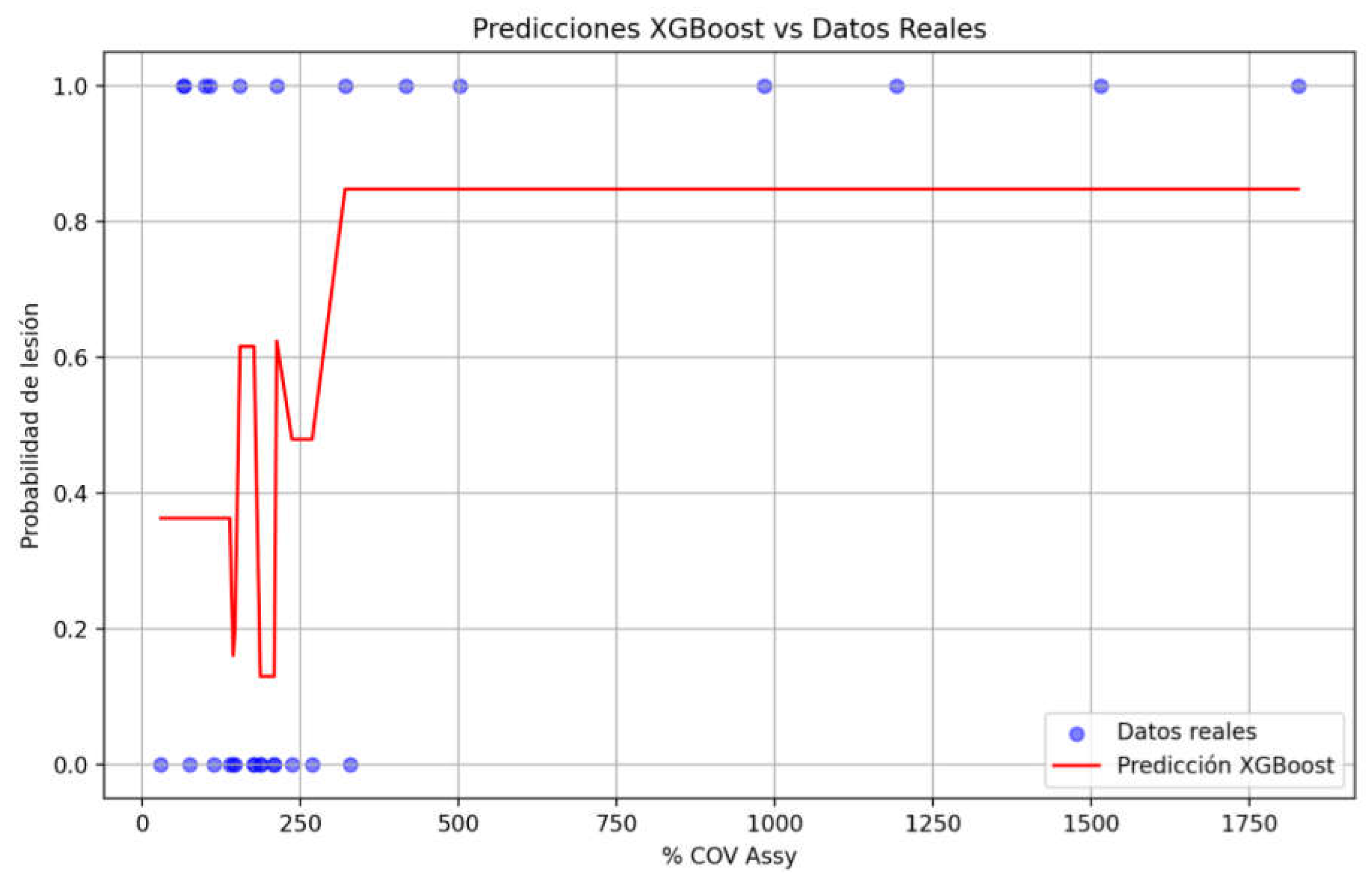

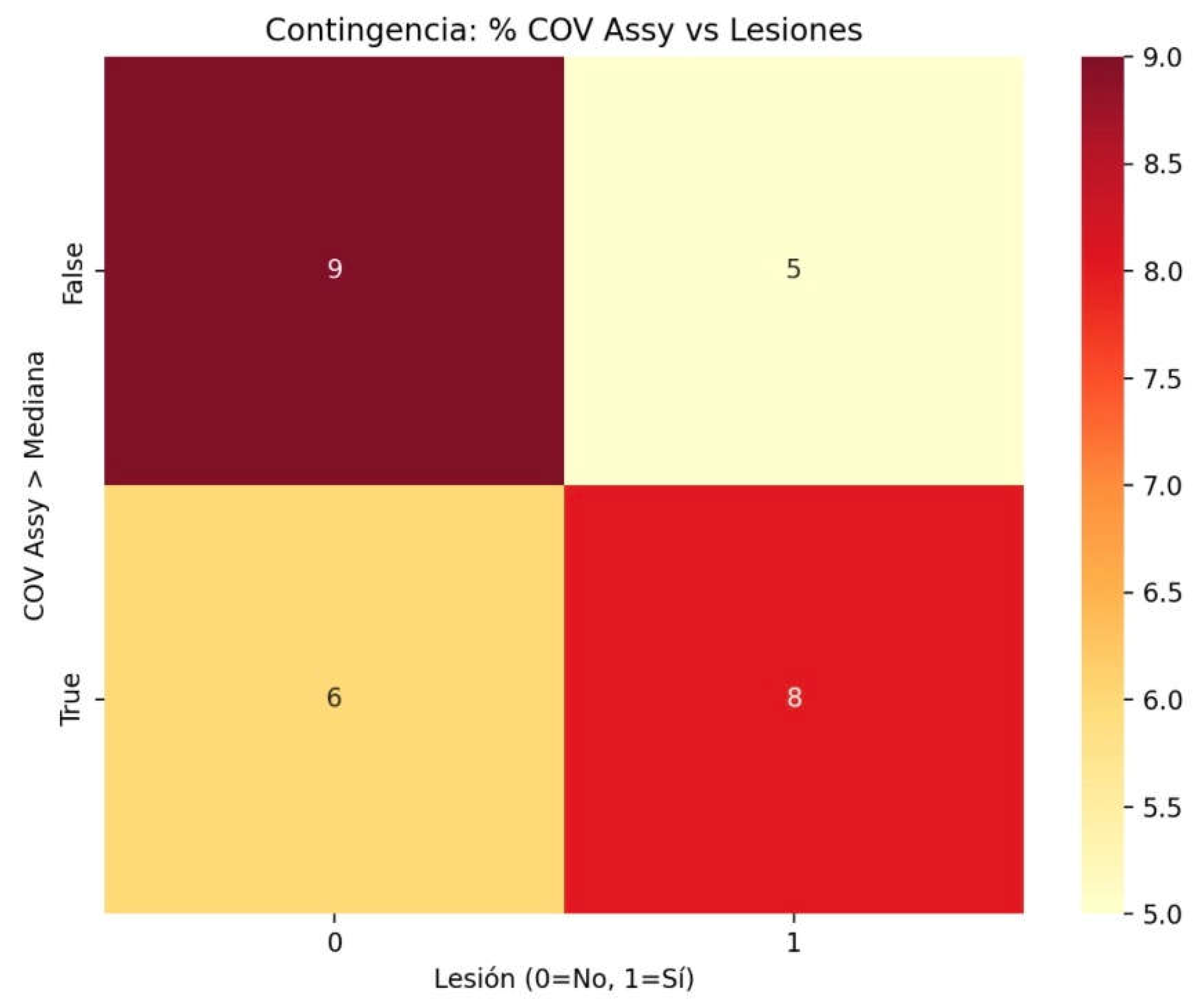

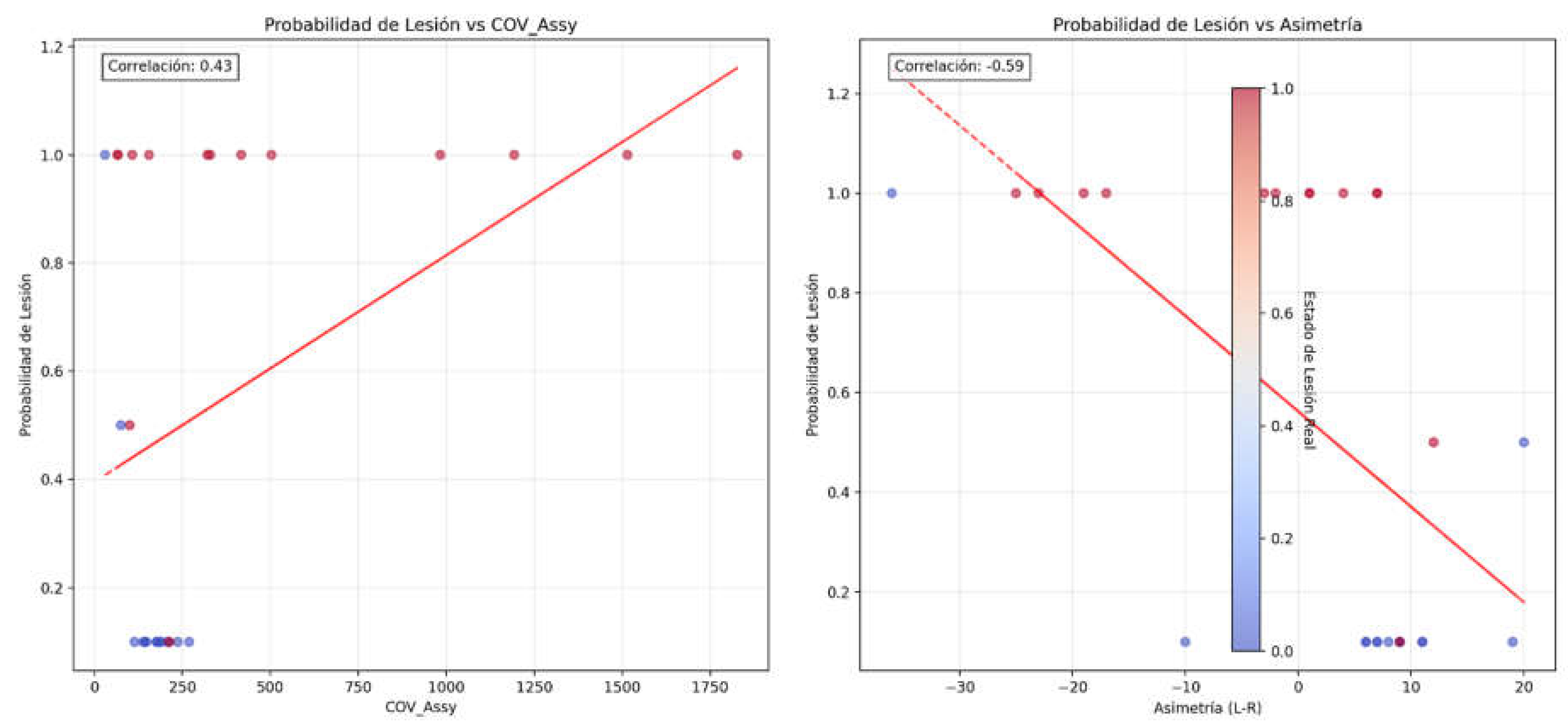

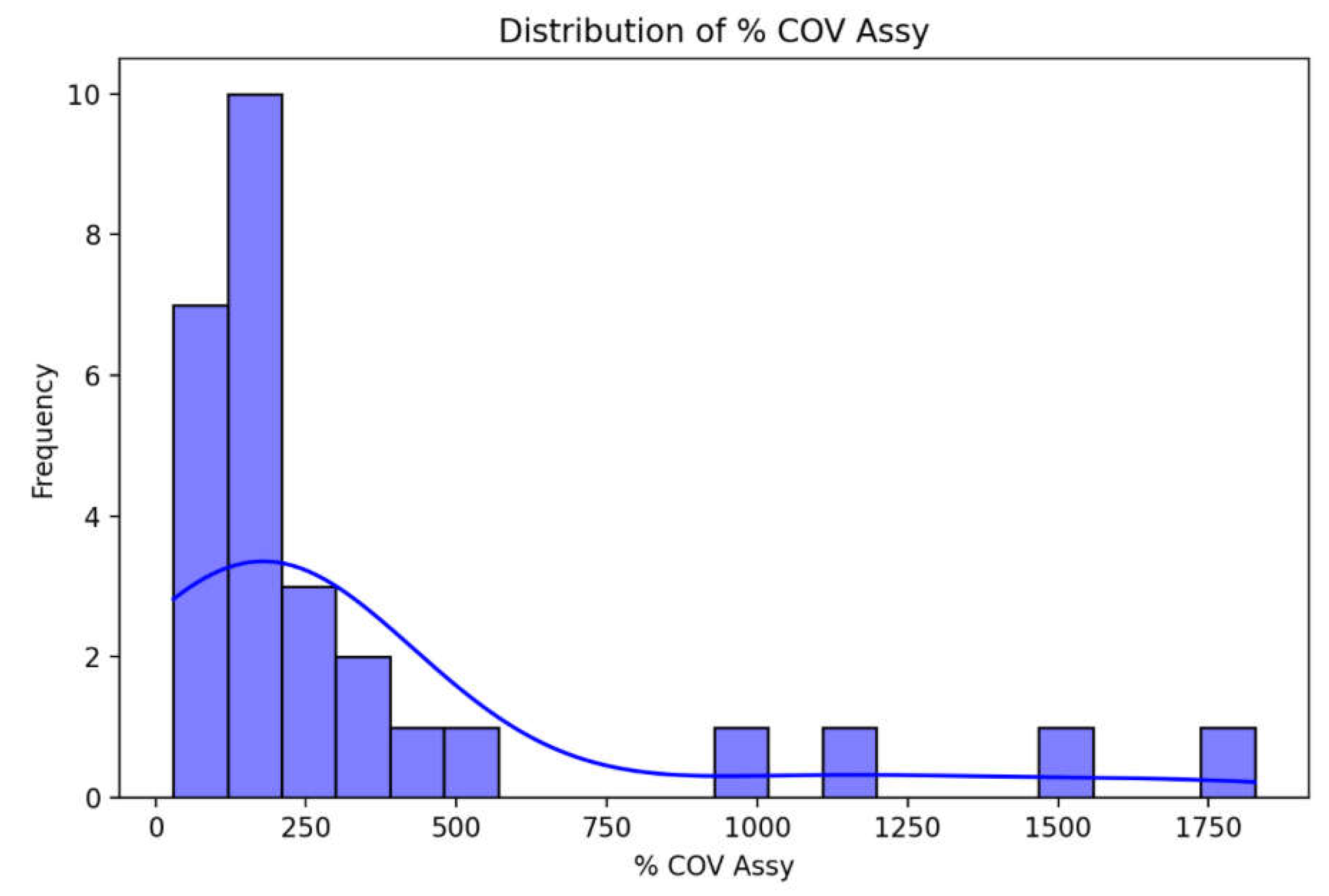

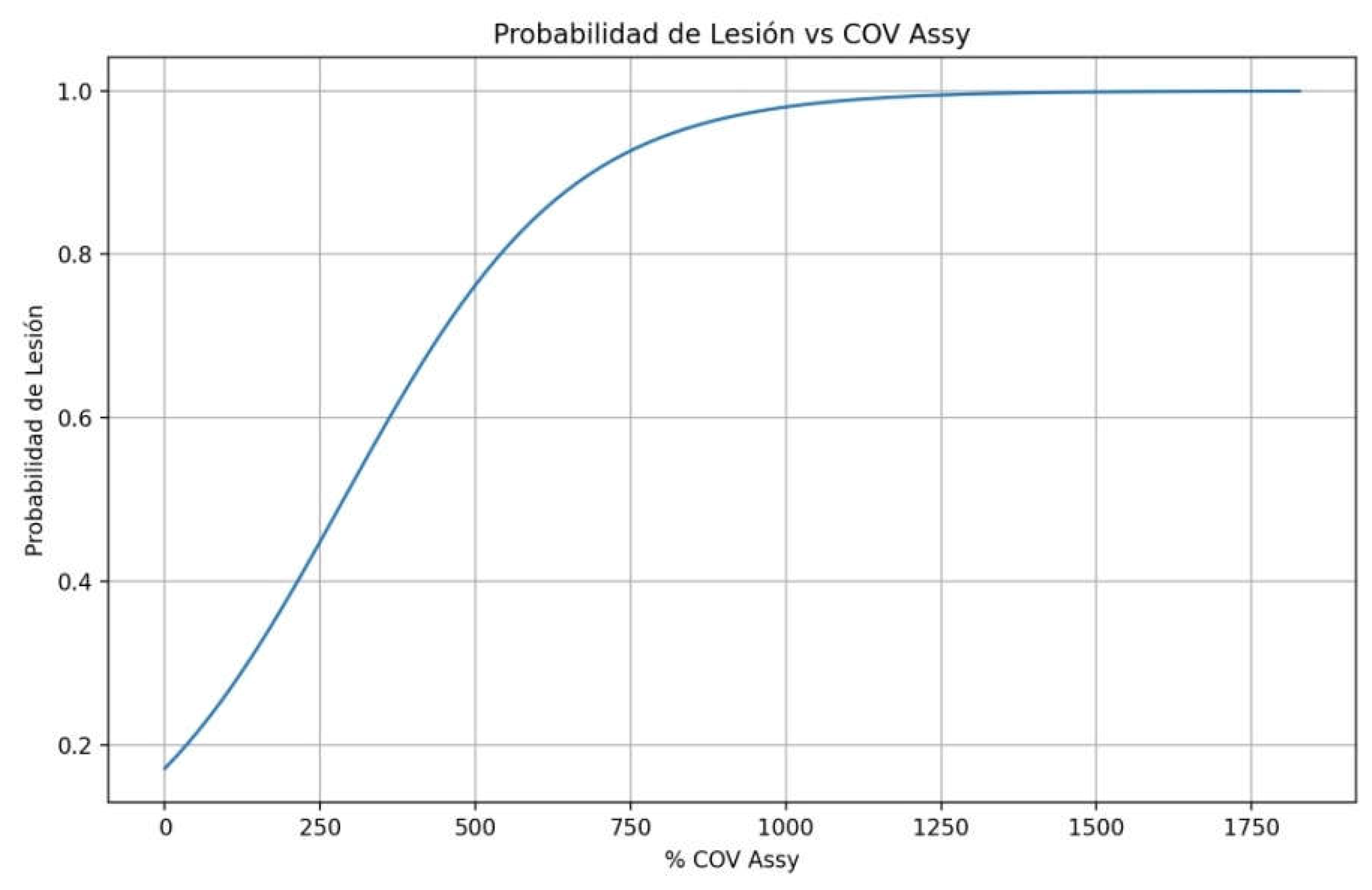

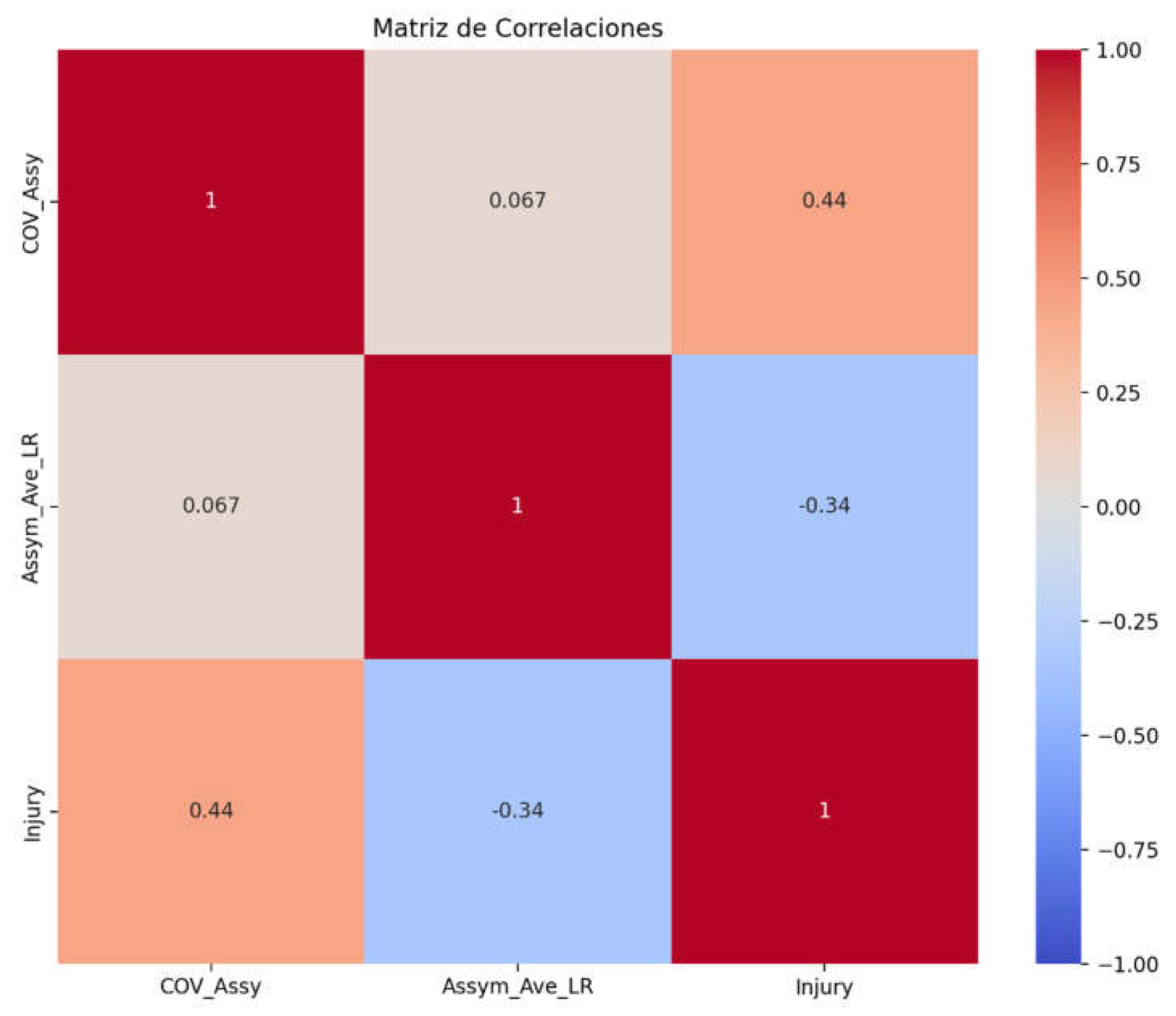

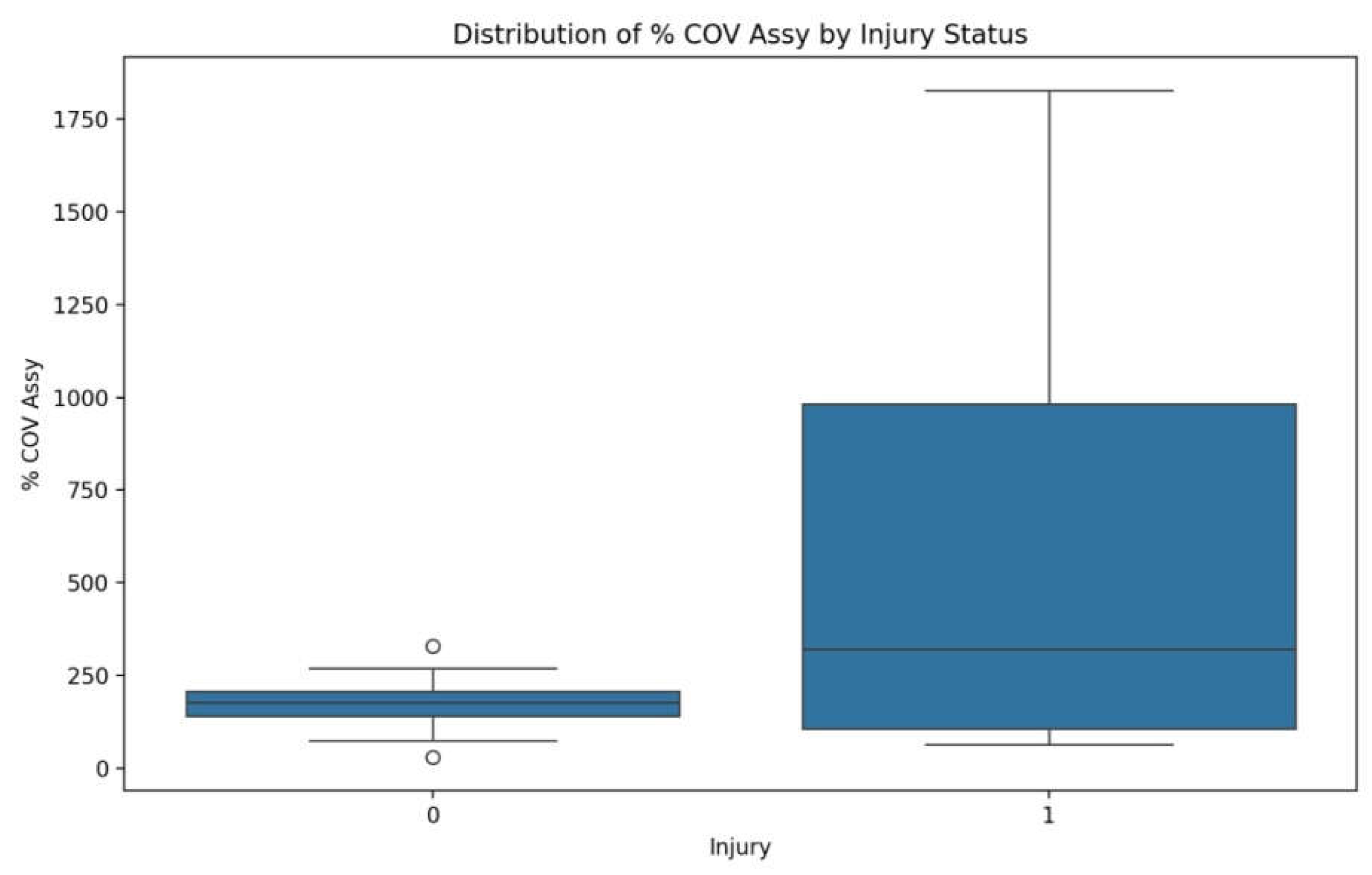

3.2. % Coefficient of Variation (COV) of Peak Landing Force Asymmetry

3.3. Dominant Side vs No Dominant Side

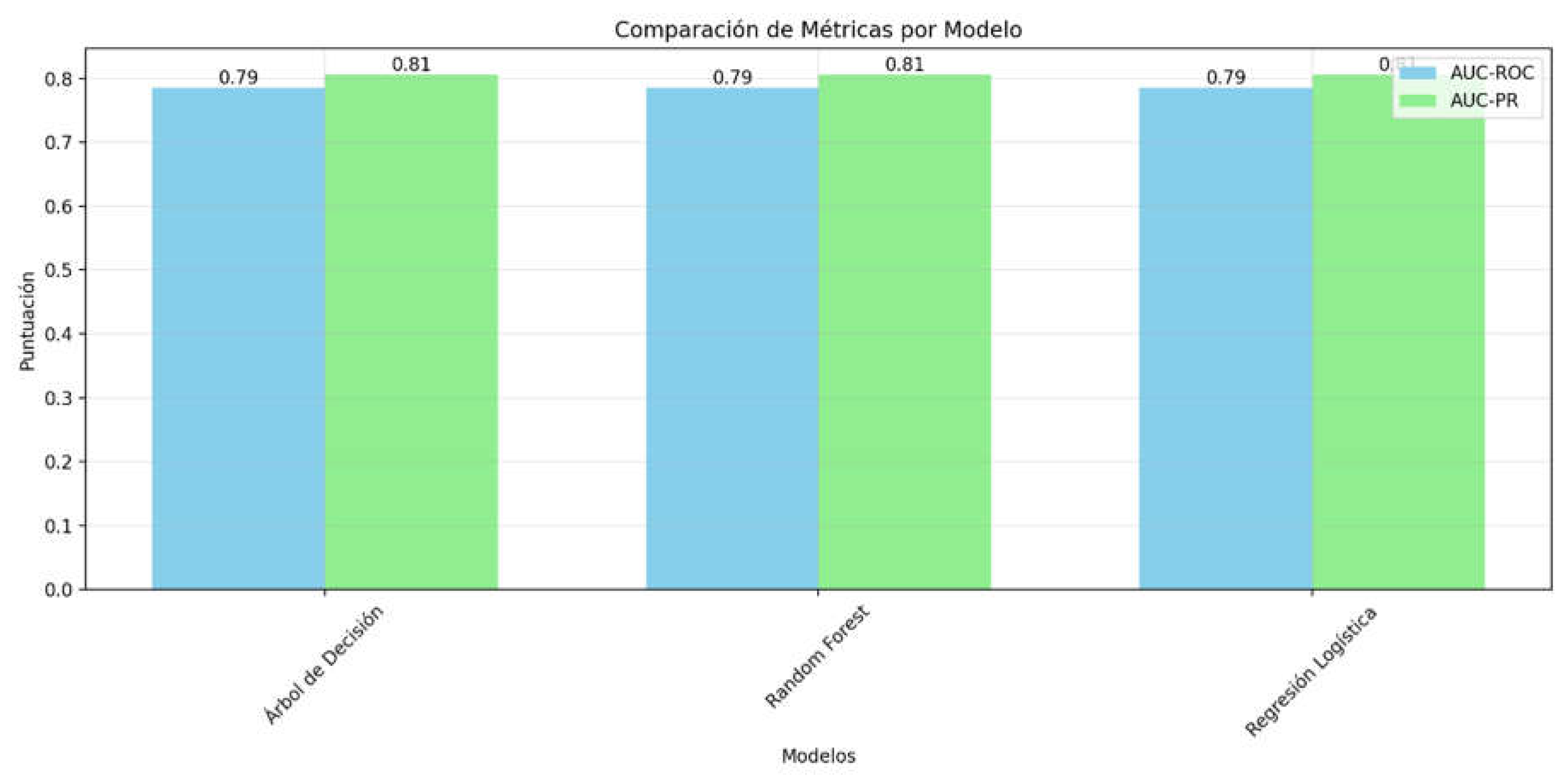

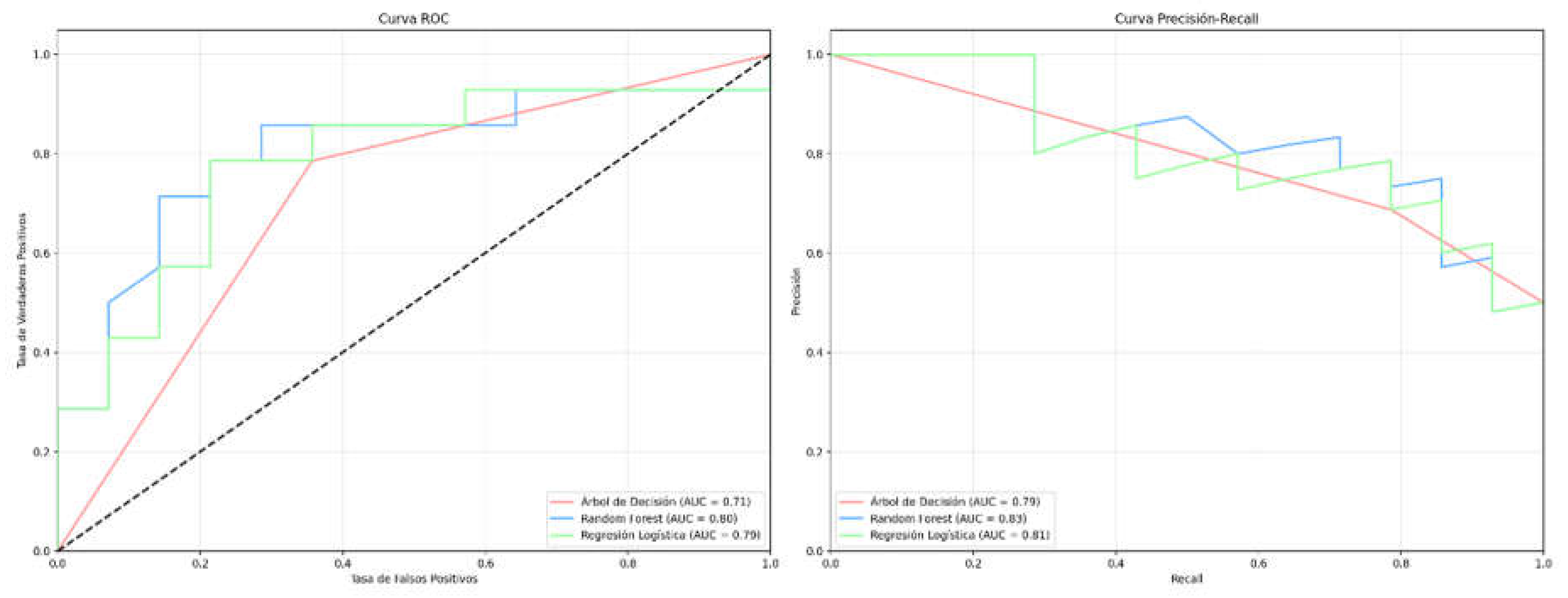

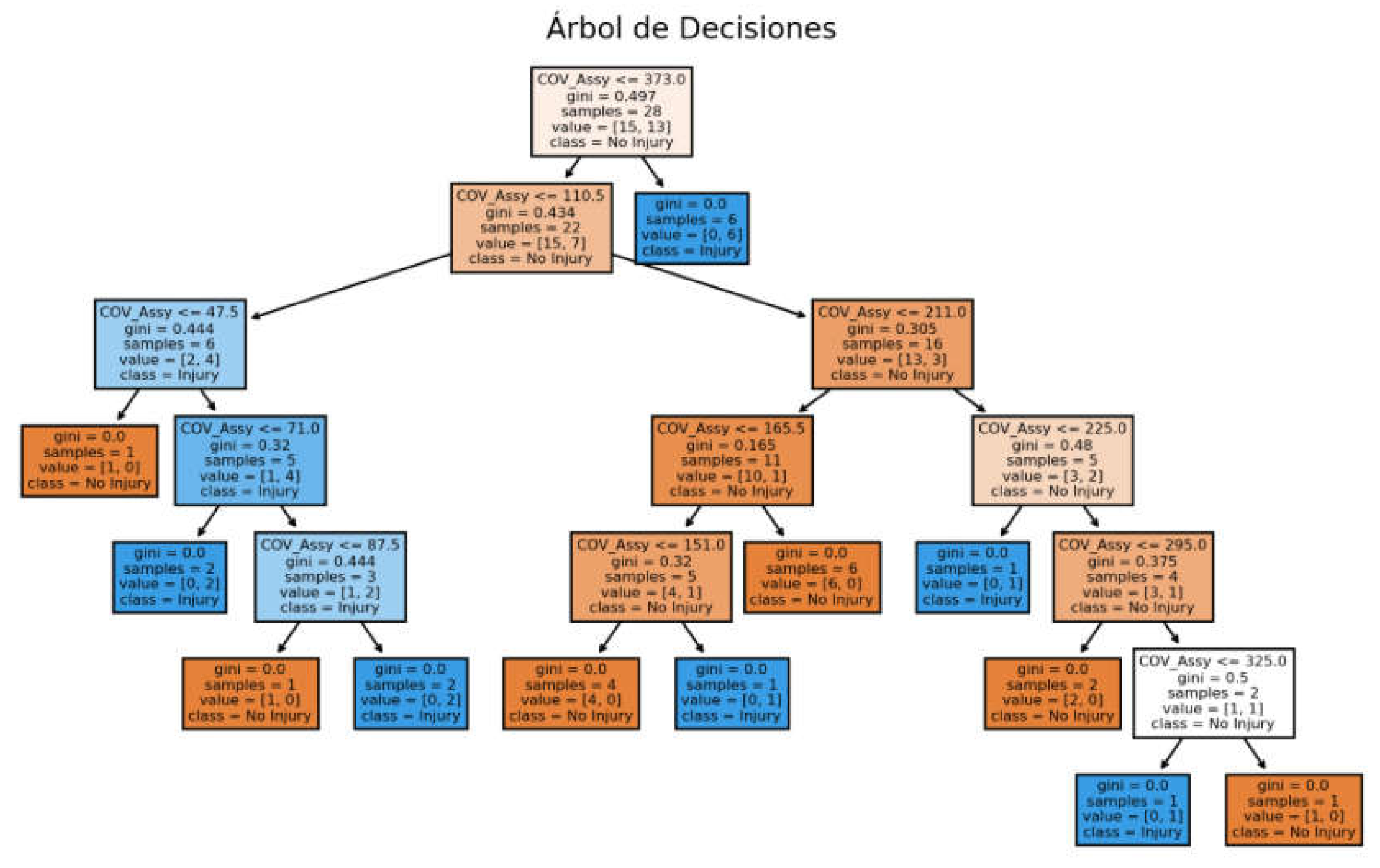

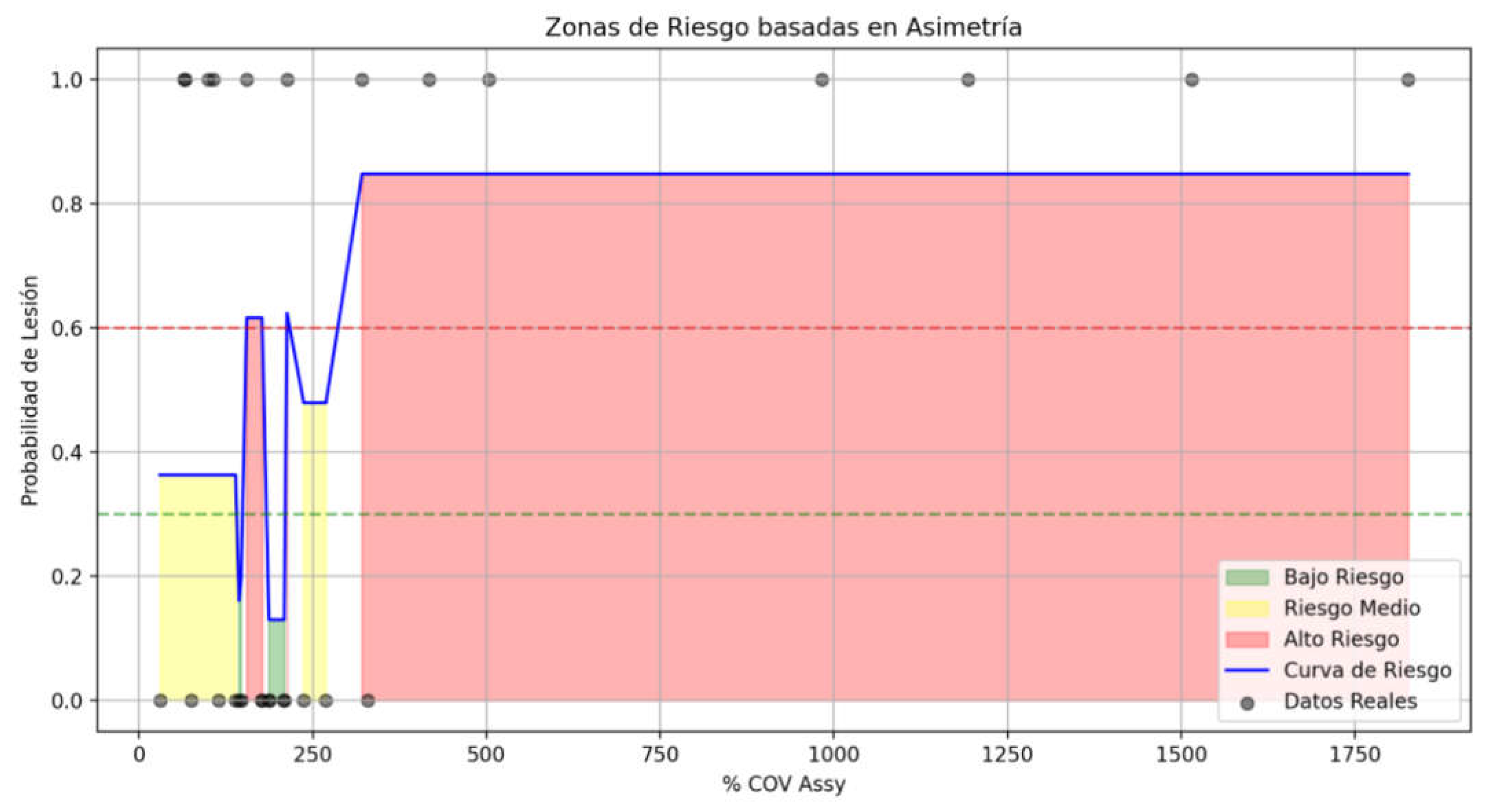

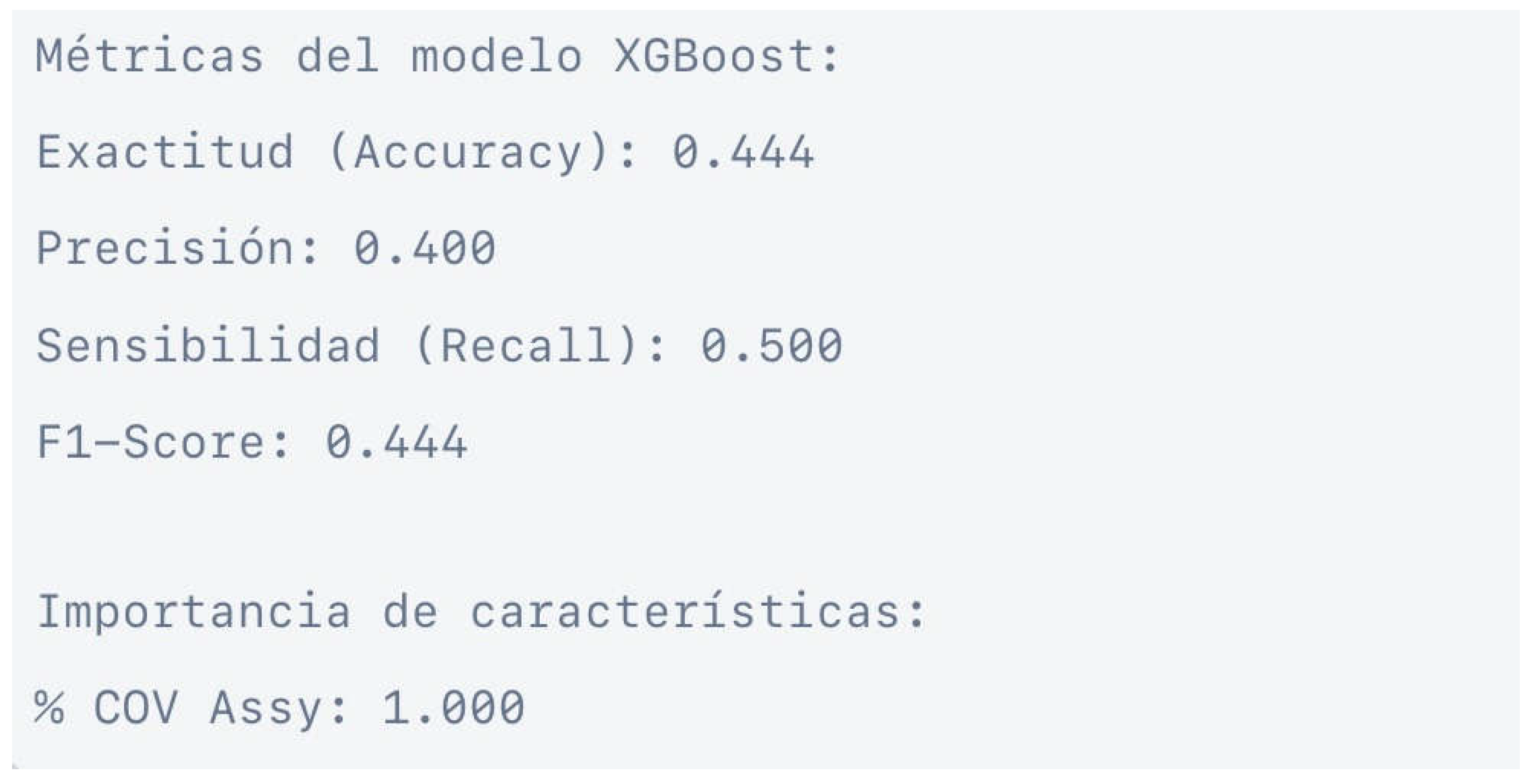

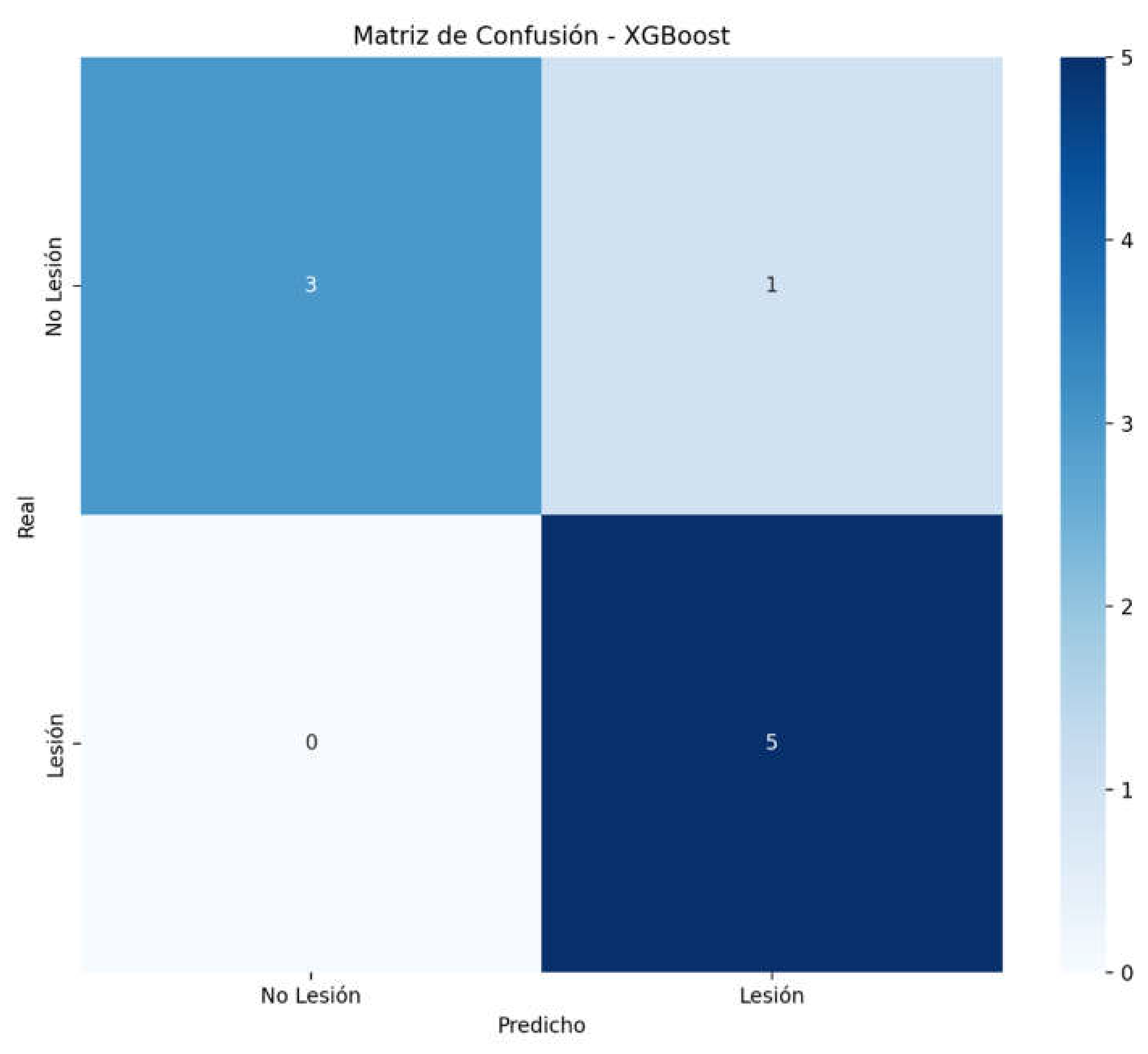

3.4. Predictions Based on Different Models of Machine Learning

4. Practical Implications

References

- Ekstrand, J.; Bengtsson, H.; Waldén, M.; Davison, M.; Khan, K.M.; Hägglund, M. Hamstring injury rates have increased during recent seasons and now constitute 24% of all injuries in men’s professional football: the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study from 2001/02 to 2021. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023, 57, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstrand, J.; Hägglund, M.; Walden, M. Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football: The UEFA injury study. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2011, 45, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Marcora, S.M.; Coutts, A.J. Internal and external training load: 15 years on. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2019, 14, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, C.; Read, P.; Lake, J.; Chavda, S.; Turner, A.; Loturco, I. Interlimb asymmetries: The need for an alternative approach to data analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2018, 32, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Badau, A.; Cengiz, Ş.Ş.; Karesi, H.; Er, B. The Effect of Hamstring Eccentric Strength and Asymmetry on Acceleration and Vertical Jump Perfor-mance in Professional Female Soccer Players. Retos: Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación 2024, 57, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helme, M.; Tee, J.; Emmonds, S.; Low, C. Does lower-limb asymmetry increase injury risk in sport? A systematic review. Physical therapy in sport 2021, 49, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe, A.; Gual, G.; Romero-Rodríguez, D.; Unnitha, V. Lower limb neuromuscular asymmetry in volleyball and basketball players. Journal of Human Kinetics 2016, 50, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, G.; Darrall-Jones, J.; Black, C.; Shaw, W.; Till, K.; Jones, B. Between-day reliability and sensitivity of common fatigue measures in rugby players. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2017, 12, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, R.; Sporer, B.; Stellingwerff, T.; Sleivert, G. Comparison of the capacity of different jump and sprint field tests to detect neuromuscular fatigue. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2015, 29, 2522–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, T.J.; Lima, Y.L.; Dutaillis, B.; Bourne, M.N. Concurrent validity and test–retest reliability of VALD ForceDecks strength, balance, and movement assessment tests. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meras Serrano, H.; Mottet, D.; Caillaud, K. Validity and Reliability of Kinvent Plates for Assessing Single Leg Static and Dynamic Balance in the Field. Sensors 2023, 23, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagchi, A.; Raizada, S.; Thapa, R.K.; Stefanica, V.; Ceylan, H.İ. Reliability and Accuracy of Portable Devices for Measuring Countermovement Jump Height in Physically Active Adults: A Comparison of Force Platforms, Contact Mats, and Video-Based Software. Life 2024, 14, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, J.J.; Ripley, N.J.; Comfort, P. Force plate-derived countermovement jump normative data and benchmarks for professional rugby league players. Sensors 2022, 22, 8669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, D.; Shirley, M.; Fuller, M.; Reyes, C. Validity and reliability of countermovement vertical jump measuring devices. International Journal of Exercise Science: Conference Proceedings 2019, 8, 38. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, M.W.; Young, W.B.; Talpey, S.W.; Behm, D.G. Does the warm-up effect subsequent post activation performance enhancement. J. Sport Exerc. Sci 2021, 5, 302–309. [Google Scholar]

- Espada, M.C.; Jardim, M.; Assunção, R.; Estaca, A.; Ferreira, C.C.; Pessôa Filho, D.M.; Santos, F.J. Lower Limb Unilateral and Bilateral Strength Asymmetry in High-Level Male Senior and Professional Football Players. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1579. [Google Scholar]

- Badby, A.J.; Mundy, P.D.; Comfort, P.; Lake, J.P.; McMahon, J.J. The validity of Hawkin Dynamics wireless dual force plates for measuring countermovement jump and drop jump variables. Sensors 2023, 23, 4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrigan, J.J.; Stone, J.D.; Galster, S.M.; Hagen, J.A. Analyzing force-time curves: Comparison of commercially available automated software and custom MATLAB analyses. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 2387–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, J.D.; Shield, A.J.; Williams, M.D.; Opar, D.A. Predicting hamstring strain injury in elite athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2018, 50, 828–836. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, J.L.; Ayala, F.; Croix, M.B.D.S.; Lloyd, R.S.; Myer, G.D.; Read, P.J. Using machine learning to improve our understanding of injury risk and prediction in elite male youth football players. Journal of science and medicine in sport 2020, 23, 1044–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, N.H.; Nimphius, S.; Spiteri, T.; Newton, R.U. Leg strength and lean mass symmetry influences kicking performance in Australian football. Journal of sports science & medicine 2014, 13, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Hewit, J.K.; Cronin, J.B.; Hume, P.A. Asymmetry in multi-directional jumping tasks. Physical Therapy in Sport 2012, 13, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, C.; Turner, A.; Read, P. Effects of inter-limb asymmetries on physical and sports performance: A systematic review. Journal of sports sciences 2018, 36, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, A.O.; Apps, C.L.; Morris, J.G.; Barnett, C.T.; Lewis, M.G. The calculation, thresholds and reporting of inter-limb strength asymmetry: A systematic review. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 2021, 20, 594. [Google Scholar]

- Menzel, H.J.; Chagas, M.H.; Szmuchrowski, L.A.; Araujo, S.R.; de Andrade, A.G.; de Jesus-Moraleida, F.R. Analysis of lower limb asymmetries by isokinetic and vertical jump tests in soccer players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2013, 27, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar]

- Bromley, T.; Turner, A.; Read, P.; Lake, J.; Maloney, S.; Chavda, S.; Bishop, C. Effects of a competitive soccer match on jump performance and interlimb asymmetries in elite academy soccer players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2021, 35, 1707–1714. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.; Jones, P.A.; Dos’ Santos, T. Countermovement jump force–time curve analysis between strength-matched male and female soccer players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanci, J.; Camara, J. Bilateral and unilateral vertical ground reaction forces and leg asymmetries in soccer players. Biology of sport 2016, 33, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.; Read, P.; Chavda, S.; Jarvis, P.; Brazier, J.; Bromley, T.; Turner, A. Magnitude or direction? Seasonal variation of interlimb asymmetry in elite academy soccer players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2022, 36, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).