1. Introduction

This paper reviews a number of thematic issues that relate to forest governance and its effects. These vary in their connections to forest management and forest loss, and also in how they interweave with governance and socioeconomic factors. In the years 2000-2015, globally one-fourth of the loss has been due to commodity production [

1](Curtis, et al. 2018). This whole field has been dynamic. An ambitious effort by Goldman and others to bring together data on 7 agricultural on major commodities as to 2018, but it is being updated [

2](Goldman, 2020; pers. comm.), but perhaps a review of major industries separately will be of interest. The world is losing, say, 10 million ha) of forest every year. Most in the tropical world.

This note occasionally refers to the Top 52 [

3](Irland, 2025). These are the largest 52 nations with 10 million hectares or more of forest, containing more than 90% of the world’s forest. We will first examine food crops, food stress, the oilseed world, and fuelwood gangs. This is because wood is the basic cooking fuel. Next, we will look at illicit drugs, conflict and wars, illegal mining, and colonial histories. This paper relies on examples to convey the message.

2. Materials and Methods

We begin by focusing on the bulk of the problem – the 52 countries that account for 92% of the world’s forests [

4] (FAO. 2020, App. 1). We then review recent selected studies of the principal forces affecting each region. Finally, we review data on the principal causes. This review emphasizes the importance of “soft” influences such as food shortages, instead of items that can readily be measured by satellites.

The aim here is to present an overall picture of the globe; four million ha of forest, not to inquire deeply into any one nation. It is an essay rather than an empirical investigation. The fundamental requirement of a sustained yield of any forest service is the presence of a solid institutional and legal framework. The examples cited here illustrate the problem.

3. Results

Background for this is that corruption is widespread in the world. Since 2005 it has gotten worse rather than better. The fact is that forest area worldwide is strongly concentrated in the most corrupt countries (

Table 1).

3.1. Food Stress

The Food Security Information Network (FSIN) and Global Network Against Food Crises [

5](2024) reported that in 2024, 282 million people in 59 countries/territories were in need of urgent food, livelihood, and nutrition assistance at the peak point in the year. There were 20 countries whose principal driver of insecurity was conflicts, 134.5 million followed by economic shocks accounting for 77.5 million followed by weather extremes accounting for 71.9 million.

The FAO’s Food Price Index [

6](FAO World Food Situation n.d.) followed a period of moderation with an explosion after 2011, they rose from 98.1 in 2020 to 144,.5 in 2022 due to the COVID epidemic. It then fell back to 122. This behavior masked the rise in vegetable oils. After a period of strength through 2014 fell to new lows by 2019; they then rose dramatically, reaching 3 times the 2019 annual average by spring 2024 at 138.2, the highest component of the Index. Cereals, however continued downward.

At the extreme stage, we have the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Sudan, Afghanistan, and Ethiopia there were more than 20 million each of citizens facing famine (April 2025). At present the outlook is of one million citizens to die of famine in Sudan if nothing is done. At present, the condition in Syria and Gaza are also much in our attention.

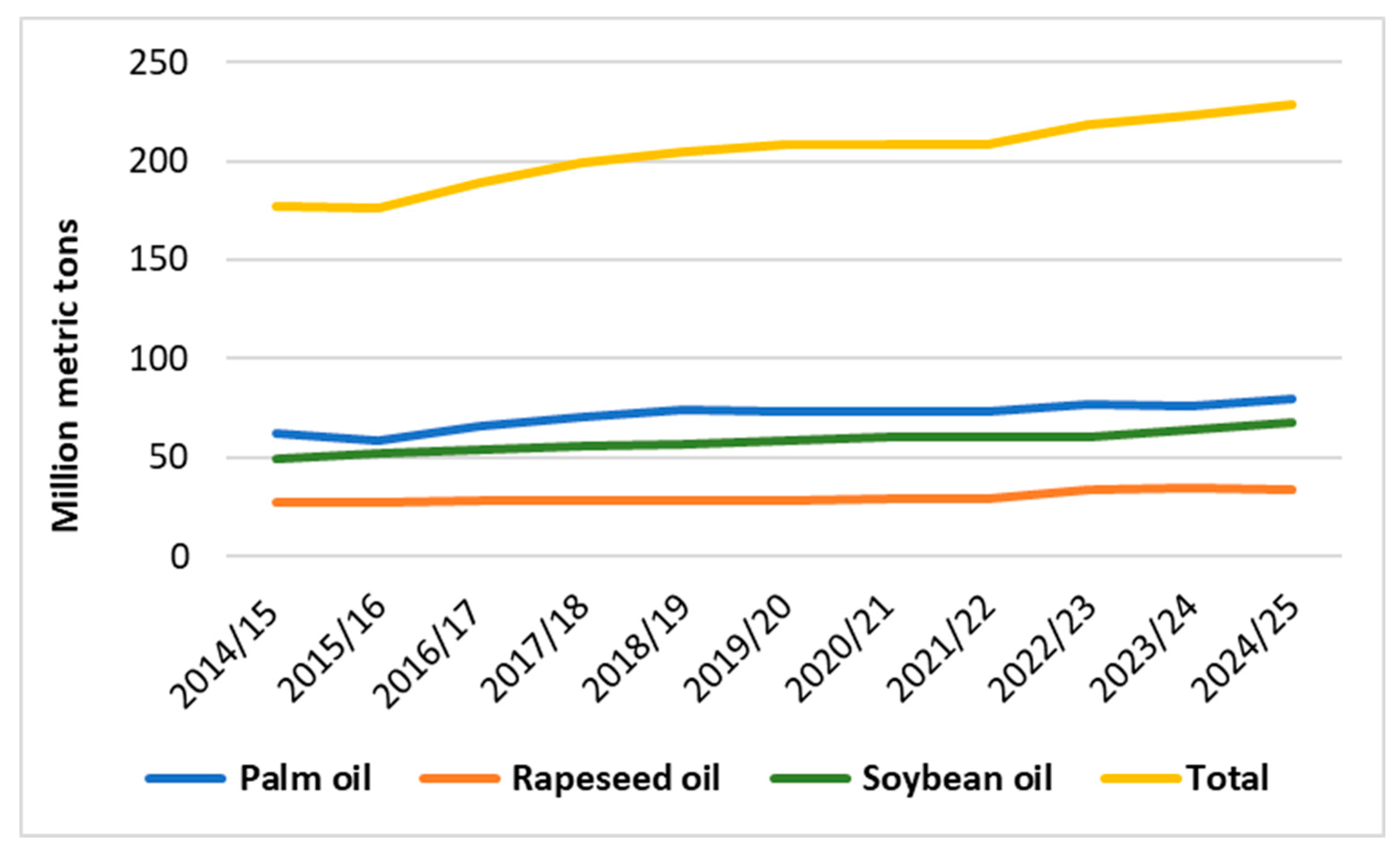

3.2. Land Use Pressures: Oilseed World

Several major tropical nations are experiencing strong land use pressures from the oilseed sector of the world’s farm economy [

7](Chomitz, 2007). The most prominent commodities are soybeans and palm oil. According to the USDA Economics, Statistics and Market Information System [

8](2022), five nations – Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Colombia, and Nigeria – account for most of the world’s palm oil production, which is rising steadily (

Figure 1). Indonesia alone accounts for 59% of the global total. Largest palm oil importers are India, China, and the EU. Soy production is also spreading to other parts of the tropical world. Brazil now leads the world in soybean production, accounting for 36% of the world’s total, outdistancing the USA since 2018. Argentina, China, India, and Paraguay are also significant producers. Still, China is by far the largest importer.

The picture is blurring with the rapid growth of oil palm in the New World, also close to markets. An example is Guatemala, projected to become the third largest producer of oil palm in the world by 2030, where large plantations have been established in key biodiversity areas [

9,

10](VanderWilde, et al. 2023, Zanon., 2025).

3.3. Fuelwood Gangs Monopolies and Wood Supply Chains

In the drylands, wood for fuel is critical for life support, as is the fodder supplied by trees and shrubs. Naturally enough, attention to logging of valuable woods in pristine tropical forests has drawn extensive attention and research [

11](Mumbere-Kiwanza, et al. 2023). In recent years, though, fieldwork in the drylands has begun turning up situations where local and regional fuelwood markets have been cartelized by local armed gangs or “mafias” which control harvesting, deliveries, and prices [

12,

13](Shabelle Media Network 2018, Mawa, et al. 2022). Their willingness to support forest and woodland conservation and carbon storage measures should not be assumed out of hand.

Likewise, supply chain control by huge bureaucracies still need control, where it exists at all. Remaining reserves of hardwoods for furniture and other uses are continuing to move to the industrial world. In the case of Brazil, elaborate schemes are still in evidence for greenwashing timber, including timber used in New York’s projects [

14](Environmental Investigation Agency, 2025). The well-known story of illegal and suspicious harvesting need not be recounted here( for example, Browne, et al 2022).

3.4. Getting High: Illicit Drugs

One indicator of governance weakness is the trade in illicit drugs. This is especially important for forest conservation and stewardship as production and transit of illicit drugs occurs in remote, often rugged forested regions. The forest canopy supplies camouflage against detection by air or satellite. While involving small amounts of land area, these activities usually involve rule by gang violence, corruption of law enforcement, instability, and insecurity in large regions [

15](Rosen 2021). In Mexico, the drug lords have noticed the profits to be made from stolen and smuggled wood and are actively diversifying into that trade [

16,

17,

18](Insight Crime 2020, Economist 2023c, UN Office on Drugs and Crime 2022).

Of the 22 nations recently identified on the US “Major List” of drug trafficking nations, these include Peru (ranked 9th globally), India (10th) Mexico (12th), and Colombia (13th). In total, all 22 account for 11% of the world’s forest area. Well-known as narcostates are Colombia, and the “Golden Triangle” regions of Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Laos. The Golden Triangle has been estimated to cover 95 million ha of land [

19](Southerland 2021) – an area roughly equal to the total forest area of Indonesia, the 8th most forested nation in the world. The US and western Europe are complicit in these activities as they are major destinations for the end products. The illicit drugs market in the US alone may be as large as

$150 billion per year [

20](RAND Corporation 2019).

3.5. Conflict and Wars

By the arbitrary 10 MM Ha cutoff for the top 52 nations, Ukraine, the next in size after Iran, is omitted. The unfolding tragedy there will wreak further destruction before it concludes, hence trying to consider it with 2020 data would not be useful. The boundaries between outright warfare engaging modern military forces, terrorism, and turf wars between criminal gangs are fuzzy. Warfare and internal violence are widespread beginning with the frontiers of the largest forest nation, Russia. Others include the DRC, Ethiopia, northeastern regions of India, outlying regions of Mali, Myanmar, Nigeria, and Sudan, plus many smaller nations not in our Top 52. A symptom of conflict and state failure is the appearance of the notorious Wagner Group. The Group operates or has operated in at least 4 of the Top 52 nations: Mali, Sudan, Venezuela, and the Central African Republic. It profits from mines, oilfields, and reportedly in CAR, timber operations for which it provided security [

21,

22](Banco, et al. 2023, Economist 2025h). Even as this article is being written, several of the nations noted above are experiencing escalating internal warfare, dislocations of population, and onset of famine.

Effective control of rural regions in Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Myanmar, and others by ruthless drug mafias may not qualify as war until national military forces confront them [

23](Economist 2023b). Consequences for any program of planned long-term forest management and protection for any purpose, whether fuelwood, biodiversity protection, or carbon sequestration are plain to see. Indications are that conflicts are lasting longer [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28](Economist 2023a, see also Economist 2023 e-h).

The Geneva Academy [

29](n.d.) lists 114 armed conflicts worldwide, in several cases multiple conflicts within one country’s borders. Just within the lowest 16 nations ranked by governance, nine contain such conflicts, most prominently DRC. Total area of forests in these 9 countries is 304 million ha. In Europe, in the post-Soviet states, a total of 7 currently exist, including the current Russia /Ukraine war, the largest European war since 1945. Not only do warring factions occupy forested regions and cause battle damage, they consume wood for fortifications and camouflage, for fuel, and in some cases engage in smuggling to meet expenses. Internal conflict is often both a cause of and a result of weak governance. Further examples include Houreld [

30](2023), Economist [

17,

23,

24,

31](2023a-d), Wrong [

33](2023), and Dresser [

34](2022). It is no coincidence that nations mentioned in this section rank high on the Index of State Fragility; several are in the most fragile ten.

Mines are an important concomitant of war. Modern mines are laid by a variety of devices. Where in the past they were emplaced by teams of engineers with shovels, today they can be spread with rockets at a range of kilometers, making mines a deadly plague. The nations most affected include, according to the Landmine and Cluster Munitions Monitor [

35](2024) include Afghanistan, Bosnia/Herzegovina, Cambodia. Iraq, Ukraine… and the Western Sahara. The speed with which Ukraine reached the highest ranks by this measure indicates how extraordinary the technology is and how rapidly it is evolving.

3.6. IllegalMining

Several nations with important forest resources are plagued by illegal mining operations, mostly small-scale. African doctors are assessing environmental and health aspects of the nine million artisanal workers there [

36](Ondayo, at al. 2023.). Worldwide, about 40 million jobs, and 130 -270 million people are supported in the communities [

37](Finn, Simon, and Newell 2024).

Countries like Brazil, the Congo and Mongolia are well known. The current boom in rare earth metals and substances needed in electronics is boosting the range and location of mining. Examples in Venezuela are coming to light, detected only by remote imaging [

38](Poliszuk, et al. 2022). Mining concessions on a large scale may be awarded by suspicious methods or may operate in defiance of government approvals or property rights [

39,

40,

41,

42] (Stearns 2022; Phillips and Milhorance 2021, Tollefson 2021, Vallejos, et al. n.d.) and mining for “blood diamonds” [

43](USGS 2022). The term “ASM” – artisanal and small-scale mining, meaning mining carried out by grueling hand labor – is now commonplace in forest protection literature. The issues are likely to be more localized, similar to the drug labs, but they create pockets of informal settlement, along with pressure on fuelwood and game populations. They may lead to later development of informal roads which further attract forest clearing, subsistence farming, and producing the crops for the drug labs. Illegal mining has become so widespread in the tropical world that it contributes to sediment detectable in rivers by satellites [

44](Dethier, et al. 2023).

3.7. Colonial Histories

Many nations rated with strong governance, stability, and low corruption are former overlords of colonies (at least 6). Whether a nation was once a colony depends on definitions. At one time, Russia suffered under the “Mongol Yoke” although this was largely limited to paying cash tribute. The USA was once a colony. Portions of China, governed by westerners under the “unequal treaties” were essentially colonies of overseas powers [

45](Acemoglu, et al. 2001). Britain’s “settler colonies,” ruled for generations as part of the Empire, managed internal affairs largely by themselves and many today rank high on governance measures. Many nations, then, defy a Yes or No rating as to colonial history – it is far more nuanced. An emerging academic discourse applies the concept of “neocolonialism” to efforts to secure Carbon storage in tropical forests (see [

46]Farhana 2022 for one example).

Of the 27 countries for which we have primary forest estimates, 17 have a clear colonial history. Of these, 9 placed in the lowest 2 quintiles according to CPI. Of the 10 that did not, 6 ruled at one time over colonies of their own. Chile was an outlier. Former colonies in the temperate zone comprise 19 of these; their average CPI is 31. The average for the 8 that were not former colonies since the 19th century (Russia, Canada, China, USA, Japan, Sweden, Finland, and Norway.) was 68. Among those not, outliers were Russia and China, with CPIs at 30 and 42. The average for South American colonies that gained independence in the early 19th century was 32.6.

4. Discussion

Population and income growth underlies forest problems to a considerable extent. It is not discussed here but it is critical – more mouths to feed accounts of smallholder clearing; for higher levels of people importing palm oil, and for the large numbers engaged in artisanal mining. It is a fact that the bottom quintile of nations has roughly doubled in population while the top quintile has increased only 21%. No blame is attached, but it has something to do with food stress, as well as the other ills cited above.

4.1. Europe and North America

Europe is in the happy position of being in the portion of the world known as Restoration. Though most of the discussion here has focused on the tropics, that doesn’t mean that the industrial world is free of problems. Yet the conflicts over the forest grow more intense as they debate what to do with this newfound wealth – do they use it to house more and more immigrants by building wood housing? To replace fossil fuels in the interest of carbon storage, or is the answer the opposite, to use forests to store more carbon themselves? What is the role of biodiversity in these forests? Europe has assisted its transition away from fossil fuels by buying wood pellets from the USA – 7 million tons per year in 2024. Around the Mediterranean Sea, forests have been burning, Is this a response to climate change?

Land use for low-density development continues to pose a challenge to forestry, though in any brief period it can be wished away. Taking a longer view, it is a problem. Both the US and Canada have this situation. It occurs in the periphery of the growing cities as well as in the wild areas.

Canada is engaged in ongoing tussles over whether public lands can be used only for wilderness, for carbon, timber, or all three. All across the continent they face fire, in woodlands and forest. Where fire is deprived of a normal fire regime and weather is favorable illustrated by the wave of forest fires that struck Los Angeles. This caused

$27 billion in direct property losses, burning over 24,000 acres of urban property [

47](Li and Yu., 2025). Burns of this magnitude will be rare but more frequent. The State of California has already raised the area rated at high fire risk.

4.2. Russia and China

Between them, Russia and China account for one-quarter of the world’ s forests. Russia’s CPI index is 30; China’s is 42. Both are rated by Economist’s assessment as having autocratic governance. They therefore deserve special attention. Their relevance is that they have low levels of government capability, which reaches little beyond their defense establishments and their immediately associated industries. Further, their data, issued by government agencies, is currently unreliable. In the case of Russia, it is seen by other international actors as an oligarchic petrostate [

48](e.g. Smirnov et al 2013). Although it has recently been seen as the largest lumber producer in the world, its output has suffered for sanctions in the wake of the Ukraine war. Despite these sanctions it has held up well taking advantage of a variety of subterfuges. It will be a long time before international observers can take the measure of Russians true forest situation. But we know one thing – its forests are a very large distance from markets. And its governance is affected by favoritism and mafia-like circumstances.

China is a nation that has performed hugely in bringing hundreds of millions out of poverty. It controls a large area of diverse forest, arranging from jungle like forest on Hainan and to near-tundra forest in its North. But with the huge population it will always aspire to self-sufficiency in forest products, despite an active exports trade in furniture and other value-added items to the West. It currently supplies a large share of the furniture in the US market. Its problems are rooted in its population – it cannot have more forest, as it would wish, and more farmland at the same time. And in its corrupt bureaucracy.

5. Conclusions

Forest loss, as we can see, is a complex phenomenon and changes shape regularly. The perfect example is Brazil where under one President, loss of forest to soybeans fell, and the under another, it rose again. Clearly, in many countries organized crime is involved in a range of these industries alongside legitimate business [

49](Devine, 2021). Certification, as a way to control forest loss and to inform customers about what they buy is indicated frequently as a failure in these case studies.

A good deal of time was spent discussing the niggardly contributions made by industrial nations at Baku. But all of the countries described here have more important problems than forests. They are also nations with low per capita energy use and modest carbon emissions. That is even before considering the amounts that will be skimmed off the top in graft. Thus, they present a very difficult picture for decision makers. Before, funds are distributed to these countries in order to combat climate change, biodiversity, or timber sustained yield, they have a lot of homework to do.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Top 52 ranked by forest area. Source: FA0, 2022.

Table A1.

Top 52 ranked by forest area. Source: FA0, 2022.

| Rank |

Country |

CPI |

Area Ha |

Subtotal |

| 1 |

Russian Federation |

30 |

815,312 |

|

| 2 |

Brazil |

38 |

496,620 |

|

| 3 |

Canada |

77 |

346,928 |

|

| 4 |

United States |

67 |

309,795 |

|

| 5 |

China |

42 |

219,978 |

|

| 6 |

Australia |

77 |

134,005 |

|

| 7 |

D R of the Congo |

18 |

126,155 |

|

| 8 |

Indonesia |

37 |

92,133 |

|

| 9 |

Peru |

38 |

72,330 |

|

| 10 |

India |

40 |

72,160 |

2,685,416 |

| 11 |

Angola |

27 |

66,607 |

|

| 12 |

Mexico |

31 |

65,692 |

|

| 13 |

Colombia |

39 |

59,142 |

|

| 14 |

Bolivia |

31 |

50,834 |

|

| 15 |

Venezuela |

15 |

46,231 |

|

| 16 |

Tanzania |

38 |

45,745 |

|

| 17 |

Zambia |

33 |

44,814 |

|

| 18 |

Mozambique |

25 |

36,744 |

|

| 19 |

Papua New Guinea |

27 |

35,856 |

|

| 20 |

Argentina |

42 |

28,573 |

480,238 |

| 21 |

Myanmar |

28 |

28,544 |

|

| 22 |

Sweden |

85 |

27,980 |

|

| 23 |

Japan |

74 |

24,935 |

|

| 24 |

Gabon |

30 |

23,531 |

|

| 25 |

Finland |

85 |

22,409 |

|

| 26 |

Central African Republic |

26 |

22,303 |

|

| 27 |

Turkey |

40 |

22,220 |

|

| 28 |

Congo |

19 |

21,946 |

|

| 29 |

Nigeria |

25 |

21,627 |

|

| 30 |

Cameroon |

25 |

20,340 |

235,835 |

| 31 |

Thailand |

36 |

19,873 |

|

| 32 |

Malaysia |

51 |

19,114 |

|

| 33 |

Spain |

62 |

18,572 |

|

| 34 |

Guyana |

41 |

18,415 |

|

| 35 |

Sudan |

16 |

18,360 |

|

| 36 |

Chile |

67 |

18,211 |

|

| 37 |

Zimbabwe |

24 |

17,445 |

|

| 38 |

France |

69 |

17,253 |

|

| 39 |

Ethiopia |

38 |

17,069 |

|

| 40 |

South Africa |

44 |

17,050 |

181,361 |

| 41 |

Lao People's D R |

29 |

16,596 |

|

| 42 |

Paraguay |

28 |

16,102 |

|

| 43 |

Botswana |

60 |

15,255 |

|

| 44 |

Suriname |

38 |

15,196 |

|

| 45 |

Viet Nam |

36 |

14,643 |

|

| 46 |

Mongolia |

35 |

14,173 |

|

| 47 |

Mali |

30 |

13,296 |

|

| 48 |

Ecuador |

39 |

12,498 |

|

| 49 |

Madagascar |

25 |

12,430 |

|

| 50 |

Norway |

84 |

12,180 |

|

| 51 |

Germany |

80 |

11,419 |

|

| 52 |

Iran |

25 |

10,752 |

164,539 |

| |

TOTAL |

|

3,747,389 |

3,747,389 |

References

- Curtis, P.G; Slay, C.M.; Harris, N.L.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M.C. Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Sci 2018 361(6407), 1108. [CrossRef]

- Goldman, E.; Weisse, M.; Harris, N.; Schneider, T. Estimating the role of seven commodities in agriculture – linked deforestation: Oil, palm. soy, cattle, wood fiber, cocoa, coffee, and rubber. World Resources Institute. Tech Note. 2020.

- Irland, L.C. Governance, Socioeconomic stresses, global forest sustainability and responsible production and consumption. Unpublished paper. Copy in author’s files.

- FAO. Global forest resources assessment 2020: Main report. Rome. 2020. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9825en (accessed 03/01/23). [CrossRef]

- FSIN and Global Network Against Food Crises. Global report on food crises 2024. Rome, 2024. Available online: https://www.fsinplatform.org/grfc2024 (accessed 13 April 2025).

- FAO World Food Situation. FAO food price index. n.d. Available online: https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en/ (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Chomitz, K. At Loggerheads? Agricultural expansion, poverty reduction, and environment in the tropical forests. World Bank: Washington, DC, 2007. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/223221468320336327/pdf/367890Loggerheads0Report.pdf (accessed 13 April 2025).

- USDA Economics, Statistics and Market Information System. Oilseeds: World markets and trade. Washington DC. 2022. Available online: https://usda.library.cornell.edu/concern/publications/tx31qh68h?locale=en&page=2#release-items (accessed 13 April 2025).

- VanderWilde. C.P.; Newell, J.P.; Gounaridis, D.; Goldstein, B.P. Deforestation, certification, and transnational palm oil supply chains: Linking Guatemala to global consumer markets. J. Environ. Manag, 2023, 344, 118505. [CrossRef]

- Mumbere Kiwanza, G.; Schure, J.; Cerutti, P.O.; Kasereka-Muvatsi, L. Agroforestry and sustainable woodfuel: Experiences from the Yangambi landscape in DRC. Sustainable Woodfuel Brief #8. CIFOR-ICRAF: Bogor, Indonesia and Nairobi, Kenya, 2023. Available online: https://www.cifor.org/knowledge/publication/8796 (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Shabelle Media Network. Somalia: Charcoal, illegal logging fund Al-Shabaab militants hiding in Boni Forest. Mogadishu, 2018. Available onlilne: https://allafrica.com/stories/201803280474.html (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Mawa, C.; Babweteera, F.; Tumusiime, D.M. Conservation outcomes of collaborative forest management in a medium altitude semideciduous forest in Mid-western Uganda. J. Sustain. For., 2022, 41(3-5), 462-480 (ref to fuelwood at pp. 474 ff). [CrossRef]

- Environmental Investigation Agency. Tricks, traders and trees: How illegal logging drives forest crime in the Brazilian Amazon and feeds E.U. and US markets. 2025. Available online: https://eia.org/report/tricks-traders-and-trees/ (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Rosen, L.W. The US “Majors list” of illicit drug-producing and drug-transit countries. Congressional Research Service, R46695, 2021.

- Insight Crime. How drug cartels moved into illegal logging in Mexico. 2020, September 18. Available online: https://insightcrime.org/investigations/drug-cartels-illegal-logging-mexico/ (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Economist. The problem of gangs: beyond drugs. 2023, May 13, 27, 28. (Mexico Jalisco gangs control timber).

- UN Office on Drugs and Crime. World drug report. 5 volumes. Vienna, 2022. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2022.html (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Southerland, D. Myanmar’s forests under pressure from illegal logging, smuggling. October 11, 2021. Available online: https://www.rfa.org/english/commentaries/forests-myanmar-10112021104031.html (accessed 13 April 2025).

- RAND Corporation. Spending on illicit drugs in US nears $150 billion annually: Amount rivals what Americans spend on alcohol. ScienceDaily, 2019, August 20. Available online: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/08/190820081846.htm (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Banco, E.; Aarup, S.A.; Carrier, A. Inside the stunning growth of Russia’s Wagner Group. POLITICO, 2023, February 18. Available online: https://www.politico.com/news/2023/02/18/russia-wagner-group-ukraine-paramilitary-00083553 (accessed 13 April 2025). (CAR timber).

- Economist. How to make cash in the Coup Belt 2025, February 22. Available online: https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2025/02/22/how-to-make-cash-in-africas-coup-belt (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Economist. Conflict in Africa - War and peacemaking. 2023, May 13, 35, 36.

- Economist. Sudan is not a one-off: why are civil wars lasting longer? 2023, April 22, 49, 51.

- Economist. Offshore finance: Treasure Islands. 2023, August 26, 24.

- Economist. Ethiopia: sliding toward another war. 2023, August 19, 39, 40.

- Economist. Gabon: Here’s looking at coup, kid. 2023, September 2, 39, 40.

- Economist. Russia in Africa: what Prigozhin leaves behind. 2023, September 2, 37, 38.

- Geneva Academy. Today’s armed conflicts. n.d. Available online: https://geneva-academy.ch/galleries/today-s-armed-conflicts (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Houreld, K., USAID cuts food aid supporting millions of Ethiopians amid charges of massive government theft. The Washington Post, 2023, June 8.

- Economist. Africa’s debts; seeing red again. 2023, May 20, 41, 42.

- Wrong, M. Kagame’s revenge: why Rwanda’s leader is sowing chaos in Congo. Foreign Aff., 2023, May/June, 153-163.

- Dresser, D. Mexico’s dying democracy: AMLO and the toll of authoritarian populism. Foreign Aff., 2022, November/December, 74-90.

- Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor. Available online: https://www.the-monitor.org/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Ondayo, M.A.; Watts, M.J.; Mitchell, C.J.; King, D.C.P.; Osano, O. Review: Artisanal gold mining in Africa – Environmental pollution and human health implications. Exposd Health 2024, 16, 1067-1095. [CrossRef]

- Finn, B.M.; Simon, A.; Newell, J. Decarbonization and social justice: The case for artisanal and small scale mining, Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 117, 103733. [CrossRef]

- Poliszuk, J.; Ramirez, M.A.; Segovia, M.A. The illegal runways that are swarming the Venezuelan Jungle. Pulitzer Center, 2022. Available online: https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/illegal-runways-are-swarming-venezuelan-jungle-spanish (accessed 13 April, 2025).

- Stearns, J.K. Rebels without a cause: The new face of African warfare. Foreign Aff., 2022a, May/June, 143-156. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/africa/2022-04-19/rebels-without-cause (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Phillips, T.; Milhorance, F. Brazil aerial photos show miner’s devastation of indigenous people’s land. Guard., 2021, May 27. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/may/27/brazil-aerial-photos-reveal-devastation-by-goldminers-on-indigenous-land (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Tollefson, J. Illegal mining in the Amazon hits record high amid Indigenous protests. Nature News, 2021, September 30. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02644-x (accessed 13 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, P.Q.; Veit, P.G.; Tipula, P.; Reytar, K. Undermining rights: Indigenous lands and mining in the Amazon. World Resources Institute: Washington, DC. n.d. Available online: https://files.wri.org/d8/s3fs-public/Report_Indigenous_Lands_and_Mining_in_the_Amazon_web_1.pdf (accessed 13 April 2025).

- USGS. USGS scientists help address conflict mining. 2022, June 27. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/news/featured-story/usgs-scientists-help-address-conflict-mining (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Dethier, E.N.; Silman, M.; Leiva, J.D.; Alquahtani, S.; Fernandez, L.E.; Pauca, P.; Camalan, S.; Tomhave, P.; Magilligan, F.J.; Renshaw, C.E.; Lutz, D.A. A global rise in alluvial mining increases sediment load in tropical rivers. Nature, 2023, 620, 787–793. [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91(5), 1369-1401. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.91.5.1369 (accessed 9/21/23). [CrossRef]

- Farhana 2022. The unbearable heaviness of climate colonialism. Political Geography 99: 10238.

- Zhiyun, Ll; Yu, W. Economic impact of the Los Angeles wildfires. UCLA Anderson School of Management, Los Angeles, 2025. Available online: https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/about/centers/ucla-anderson-forecast/economic-impact-los-angeles-wildfires (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Smirnov, D.Y. (ed.); Kabanets, A.G.; Milakovsky, B.J.; Lepeshkin, E.A.; Sychikov, D.V. WWF, Moscow. Illegal logging in the Russian Far East: Global demand and Taiga destruction, 2013. Available online: https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/illegal-logging-in-the-russian-far-east-global-demand-and-taiga-destruction#:~:text=The%20forests%20of%20the%20Russian,to%20the%20U.S.%20and%20Europe. (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Devine, J. Organized crime is a top driver of global deforestation – along with beef, soy palm oil and wood products. The Conversation, 2021, November 18. Available online: https://theconversation.com/organized-crime-is-a-top-driver-of-global-deforestation-along-with-beef-soy-palm-oil-and-wood-products-170906 (accessed 13 April 20255).

- Browne, C.; Kelly, C.L.; Pilgrim, C. Illegal logging in Africa and its security implications. Africa Center for Strategic Studies: Washington DC, 2022. Available online: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/illegal-logging-in-africa-and-its-security-implications/ (accessed 13 April 2025).

- Zanon, S. Brazilian soy farms and cattle pastures close in on a land where the grass is golden. Mongabay. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2025/02/brazilian-soy-farms-and-cattle-pastures (accessed on 13 April 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).