Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

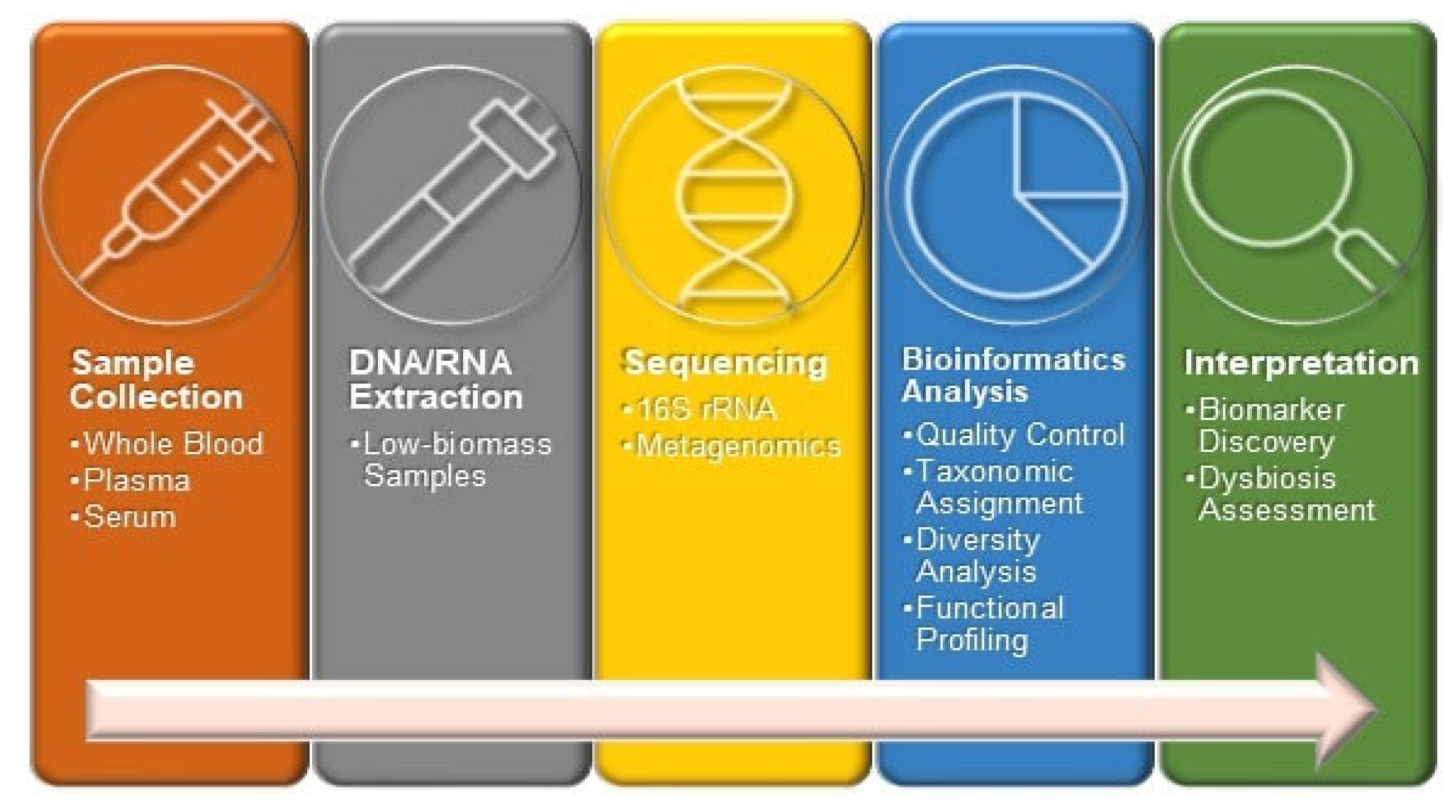

2. Results

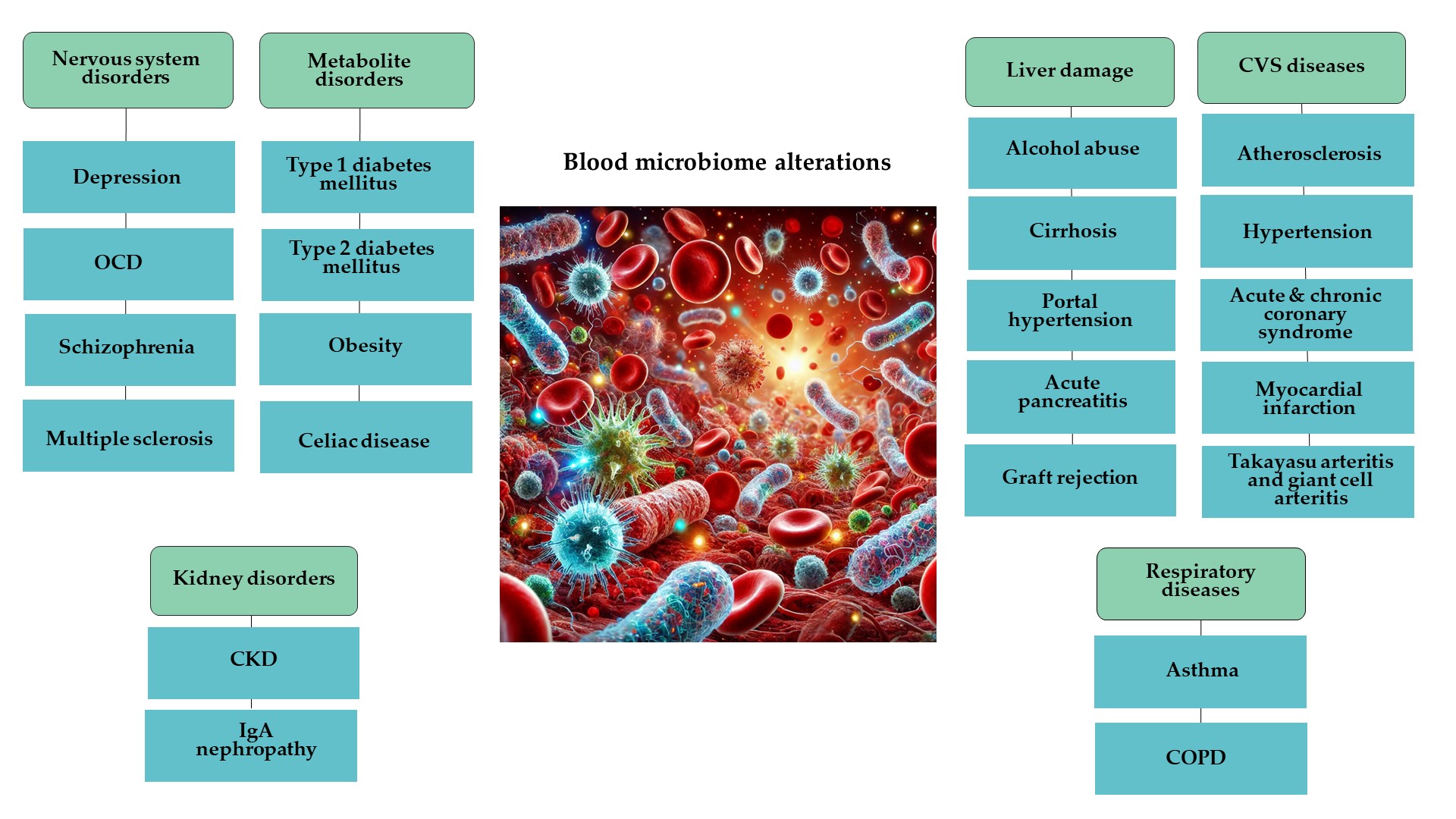

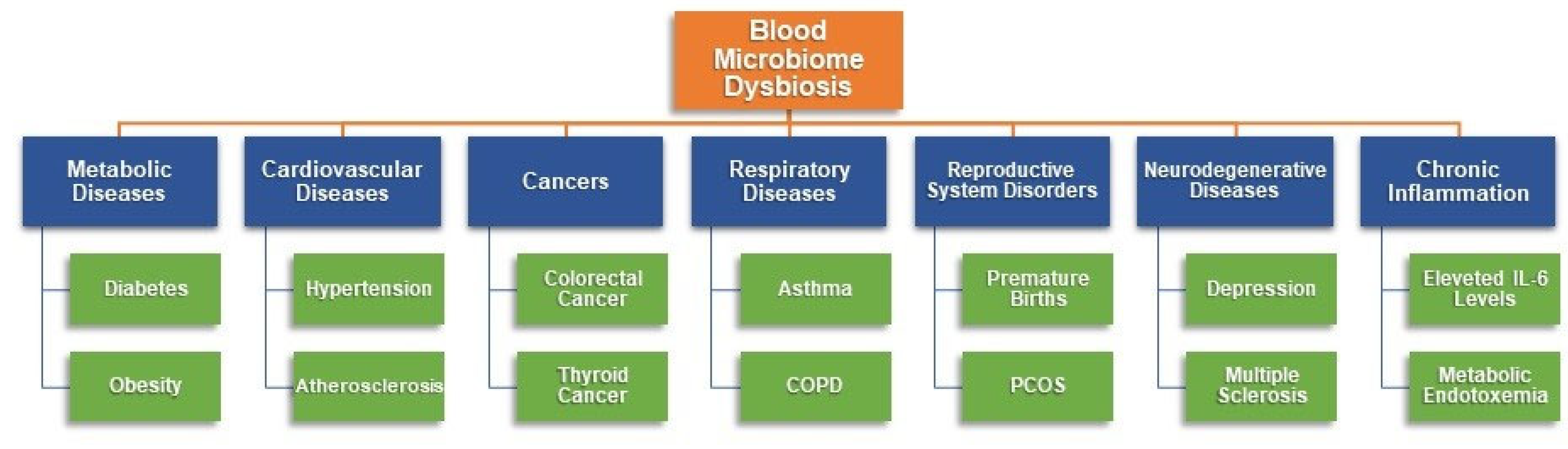

2.1. Changes in Blood Microbiome in Nervous System Disorders

2.2. Changes in Blood Microbiome in Cardiovascular Diseases

2.3. Changes in Blood Microbiome in Respiratory Diseases

2.4. Changes in Blood Microbiome in Liver Damage

2.5. Changes in Blood Microbiome in Kidney Diseases

| Condition | Increased compared to healthy controls | Decreased compared to healthy controls | Reff. |

| Alcohol abuse | Fusobacteria | Bacteroidetes | [89] |

| Cirrhosis | Enterobacteriaceae |

Akkermansia (Phylum: Verrucomicrobiota) Rikenellaceae (Phylum: Bacteroidota) Erysipelotrichales (Phylum: Bacillota) |

[31] |

| Cirrhosis with ascites |

Clostridiales Cyanobacteria |

Moraxellaceae | [29] |

| Decompensated cirrhosis |

Firmicutes Protobacteria Bacteroidetes Verrucomicrobia |

- | [30] |

| Portal hypertension (cirrhosis) |

Comamonas (Class: Betaproteobacteria) Cnuella (Phylum: Bacteroidota) Dialister (Phylum: Bacillota) Escherichia/Shigella (Class: Gammaproteobacteria) Prevotella (Phylum: Bacteroidota) |

Bradyrhizobium (Class: Alphaproteobacteria) Curvibacter (Class: Betaproteobacteria) Diaphorobacter (Class: Betaproteobacteria) Pseudarcicella Pseudomonas (Class: Gammaproteobacteria) |

[90] |

| Portal hypertension (cirrhosis) - severe symptoms |

Bacteroides Escherichia/Shigella Prevotella |

- | [90] |

| Acute pancreatitis |

Bacteroidetes Firmicutes |

Actinobacteria | [116] |

| Graft rejection after liver transplantation | Enterobacteriaceae | - | [92] |

| Patients who develop liver failure after partial hepatectomy | Diversity | [93] |

2.6. Changes in Blood Microbiome in Metabolite Disorders

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| OTUs | Operational taxonomic units |

| OCD | Obsessive–compulsive disorder |

| CVD | Cardiovascular diseases |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CD | Celiac disease |

| T1D | Type 1 diabetes |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| MUHO | Metabolically unhealthy obesity |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

References

- Berg, R.D. Bacterial translocation from the gastrointestinal tract. Adv Exp Med Biol 1999, 473, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardini, Y.; Wang, X.; Témoin, S.; Nithianantham, S.; Lee, D.; Shoham, M.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum adhesin FadA binds vascular endothelial cadherin and alters endothelial integrity. Mol Microbiol 2011, 82, 1468–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalfin, E. Resident microbial flora in human erythrocytes. J Cult Collect 1998, 2, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkari, S.; McLaughlin, I.J.; Bi, W.; Dodge, D.E.; Relman, D.A. Does blood of healthy subjects contain bacterial ribosomal DNA? J Clin Microbiol 2001, 39, 1956–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, R.W.; Vali, H.; Lau, P.C.; Palfree, R.G.; De Ciccio, A.; Sirois, M.; Ahmad, D.; Villemur, R.; Desrosiers, M.; Chan, E.C. Are there naturally occurring pleomorphic bacteria in the blood of healthy humans? J Clin Microbiol 2002, 40, 4771–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, G.S. Pleomorphic microbes in health and disease: proceedings of the first annual symposium. Montreal, Quebec, Canada; 1999.

- Jensen, G.S. Pleomorphic microbes in health and disease: proceedings of the second annual symposium. Montreal, Quebec, Canada; 2000.

- Castillo, D.J.; Rifkin, R.F.; Cowan, D.A.; Potgieter, M. The healthy human blood microbiome: fact or fiction? Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2019, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchinetti, E.; Lou, P.H.; Lemal, P.; Bestmann, L.; Hersberger, M.; Rogler, G.; Zaugg, M. Gut microbiome and circulating bacterial DNA (“blood microbiome”) in a mouse model of total parenteral nutrition: Evidence of two distinct separate microbiotic compartments. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2022, 49, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, G.; Dinakaran, V.; Rajendhran, J.; Swaminathan, K. Blood Microbiota and Circulating Microbial Metabolites in Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2020, 31, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarra, F.; Franceschini, E.; Campolo, F.; Venneri, M.A. The diagnostic potential of the human blood microbiome: are we dreaming or awake? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 10422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouello, A.; Henry, L.; Chadli, D.; Salipante, F.; Gibert, J.; Boutet-Dubois, A.; Lavigne, J.P. Evaluation of the Microbiome Identification of Forensically Relevant Biological Fluids: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Sung, J.; Kim, H.L.; Kim, H.N. Whole-genome sequencing reveals age-specific changes in the human blood microbiota. J Pers Med 2022, 12, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.; Paul, S.; Dutta, C. Geography, Ethnicity or Subsistence-Specific Variations in Human Microbiome Composition and Diversity. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.D.; Ogunrinde, E.; Wan, Z.; Li, C.; Jiang, W. Racial Disparities in Plasma Cytokine and Microbiome Profiles. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.A.; Yoo, J.Y.; Kwon, E.J.; Kim, Y.J. Blood microbial communities during pregnancy are associated with preterm birth. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, J.D.; Castaldi, P.J.; Chase, R.P.; Yun, J.H.; Lee, S.; Liu, Y.Y.; Hersh, C.P. Peripheral blood microbial signatures in current and former smokers. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 19875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panaiotov, S.; Filevski, G.; Equestre, M.; Nikolova, E.; Kalfin, R. Cultural Isolation and Characteristics of the Blood Microbiome of Healthy Individuals. Adv Microbiol 2018, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaiotov, S.; Hodzhev, Y.; Tsafarova, B.; Tolchkov, V.; Kalfin, R. Culturable and Non-Culturable Blood Microbiota of Healthy Individuals. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsafarova, B.; Hodzhev, Y.; Yordanov, G.; Tolchkov, V.; Kalfin, R.; Panaiotov, S. Morphology of blood microbiota in healthy individuals assessed by light and electron microscopy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 12, 1091341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pease, P. Discussion: microorganisms associated with malignancy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1970, 174, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narunsky-Haziza, et al. Pan-cancer analyses reveal cancer-type-specific fungal ecologies and bacteriome interactions. Cell 2022, 185, 3789–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejman, D.; Livyatan, I.; Fuks, G.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Geller, L.T.; Rotter-Maskowitz, A.; Weiser, R.; Mallel, G.; Gigi, E.; Meltser, A.; Douglas, G.M.; Kamer, I.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Dadosh, T.; Levin-Zaidman, S.; Avnet, S.; Atlan, T.; Cooper, Z.A.; Arora, R.; Cogdill, A.P.; Khan, M.A.W.; Ologun, G.; Bussi, Y.; Weinberger, A.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; Golani, O.; Perry, G.; Rokah, M.; Bahar-Shany, K.; Rozeman, E.A.; Blank, C.U.; Ronai, A.; Shaoul, R.; Amit, A.; Dorfman, T.; Kremer, R.; Cohen, Z.R.; Harnof, S.; Siegal, T.; Yehuda-Shnaidman, E.; Gal-Yam, E.N.; Shapira, H.; Baldini, N.; Langille, M.G.I.; Ben-Nun, A.; Kaufman, B.; Nissan, A.; Golan, T.; Dadiani, M.; Levanon, K.; Bar, J.; Yust-Katz, S.; Barshack, I.; Peeper, D.S.; Raz, D.J.; Segal, E.; Wargo, J.A.; Sandbank, J.; Shental, N.; Straussman, R. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type-specific intracellular bacteria. Sci. 2020, 368, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodzhev, Y. Analysis of blood microbiome dysbiosis in pulmonary sarcoidosis by decision tree model. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodzhev, Y.; Tsafarova, B.; Tolchkov, V.; Youroukova, V.; Ivanova, S.; Kostadinov, D.; Yanev, N.; Zhelyazkova, M.; Tsonev, S.; Kalfin, R.; Panaiotov, S. Visualization of the individual blood microbiome to study the etiology of sarcoidosis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2023, 22, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Fera, A.N.; Warburton, A.; Coursey, T.L.; Khurana, S.; McBride, A.A. Persistent Human Papillomavirus Infection. Viruses 2021, 13, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.H.; Kouyos, R.D.; Adams, R.J.; Grenfell, B.T.; Griffin, D.E. Prolonged persistence of measles virus RNA is characteristic of primary infection dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012, 109, 14989–14994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangul, S.; Olde Loohuis, L.; Ori, A.P.; Jospin, G.; Koslicki, D.; Yang, H.T.; Ophoff, R.A. Total RNA Sequencing reveals microbial communities in human blood and disease specific effects. bioRxiv 2016, 057570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelouvier, B.; Servant, F.; Païssé, S.; Brunet, A.C.; Benyahya, S.; Serino, M.; Valle, C.; Ortiz, M.R.; Puig, J.; Courtney, M. , et al. Changes in blood microbiota profiles associated with liver fibrosis in obese patients: A pilot analysis. Hepatology 2016, 64, 2015–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traykova, D.; Schneider, B.; Chojkier, M.; Buck, M. Blood Microbiome Quantity and the Hyperdynamic Circulation in Decompensated Cirrhotic Patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajihara, M.; Koido, S.; Kanai, T.; Ito, Z.; Matsumoto, Y.; Takakura, K.; Saruta, M.; Kato, K.; Odamaki, T.; Xiao, J.Z. , et al. Characterisation of blood microbiota in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 31, 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierwagen, R.; Alvarez-Silva, C.; Madsen, M.S.; Kolbe, C.C.; Meyer, C.; Thomas, D.; Uschner, F.E.; Magdaleno, F.; Jansen, C.; Pohlmann, A., Praktiknjo; Hischebeth, G.T.; Molitor, E.; Latz, E.; Lelouvier, B.; Trebicka, J.; Arumugam, M. Circulating microbiome in blood of different circulatory compartments. Gut 2019, 68, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, J.; Lange, C.; Payros, G.; Garret, C.; Chabo, C.; Lantieri, O.; Courtney, M.; Marre, M.; Charles, M.A.; Balkau, B. , et al. Blood microbiota dysbiosis is associated with the onset of cardiovascular events in a large general population: The D.E.S.I.R. study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinakaran, V.; Rathinavel, A.; Pushpanathan, M.; Sivakumar, R.; Gunasekaran, P.; Rajendhran, J. Elevated levels of circulating DNA in cardiovascular disease patients: Metagenomic profiling of microbiome in the circulation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, G.; Midtervoll, I.; Samuelsen, S.O.; Kristoffersen, A.K.; Enersen, M.; Håheim, L.L. The blood microbiome and its association to cardiovascular disease mortality: Case-cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2022, 22, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.B.; Allegretti, A.S.; Nigwekar, S.U.; Kalim, S.; Zhao, S.; Lelouvier, B.; Servant, F.; Serena, G.; Thadhani, R.I.; Raj, D.S. , et al. Blood Microbiome Profile in CKD: A Pilot Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019, 14, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, R.D.; Sirich, T.L. Blood Microbiome in CKD: Should We Care? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019, 14, 648–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino-Ribas, A.; Araujo, R.; Pereira, L.; Campos, J.; Barreiros, L.; Segundo, M.A.; Silva, N.; Costa, C.; Quelhas-Santos, J.; Trindade, F. , et al. Vascular Calcification and the Gut and Blood Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients on Peritoneal Dialysis: A Pilot Study. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Bin, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, K.; Li, Q. Blood Bacterial 16S rRNA Gene Alterations in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front Endocrinol 2022, 13, 814520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.S.; Tan, S.P.; Wong, D.M.K.; Koo, W.L.Y.; Wong, S.H.; Tan, N.S. The blood microbiome and health: current evidence, controversies, and challenges. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhou, H.; Jing, Y.; Dong, C. Association between blood microbiome and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A nested case-control study. J Clin Lab Anal 2019, 33, e22842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, G.D.; Kopylova, E.; Zhu, Q.; Carpenter, C.; Fraraccio, S.; Wandro, S.; Kosciolek, T.; Janssen, S.; Metcalf, J.; Song, S.J. , et al. Microbiome analyses of blood and tissues suggest cancer diagnostic approach. Nature 2020, 579, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, S.; Morse, M.A.; Wu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Li, S. , et al. Blood microbiota diversity determines response of advanced colorectal cancer to chemotherapy combined with adoptive T cell immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 1976953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goraya, M.U.; Li, R.; Mannan, A.; Gu, L.; Deng, H.; Wang, G. Human circulating bacteria and dysbiosis in non-infectious diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 932702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markova, N.D. Eubiotic vs. dysbiotic human blood microbiota: the phenomenon of cell wall deficiency and disease-trigger potential of bacterial and fungal L-forms. Discov Med 2020, 29, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrone, T.; Jirillo, E. The impact of bacterial lipopolysaccharides on the endothelial system: pathological consequences and therapeutic countermeasures. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2011, 11, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, G.S.; Benson, K.F. The blood as a diagnostic tool in chronic illness with obscure microbial involvement: A critical review. Int J Complement Alt Med 2019, 12, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Alekseyenko, A.V.; Ogunrinde, E.; Li, M.; Li, Q.Z.; Huang, L.; Jiang, W. Rigorous plasma microbiome analysis method enables disease association discovery in clinic. Front Microbiol 2021, 11, 613268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P. ImmunoAdept – bringing blood microbiome profiling to the clinical practice. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Madrid, Spain, 2018, 1577-1581. [CrossRef]

- Sato, J.; Kanazawa, A.; Ikeda, F.; Yoshihara, T.; Goto, H.; Abe, H.; Watada, H. Gut dysbiosis and detection of “live gut bacteria” in blood of Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2343–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suparan, K.; Sriwichaiin, S.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Human blood bacteriome: Eubiotic and dysbiotic states in health and diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, W.; Wen, Y.; Jiang, W.; Huang, L. The Role of Blood Microbiome and Microbial Product Translocation in Disease Pathogenesis. Adv Case Stud 2020, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, M.; Saribas, A.S.; Siadat, S.D.; Kocazeybek, B.S. Blood microbiota in health and disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1187247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, C.M.; Guerri, C.; Ureña, J.; Pascual, M. Role of microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles in gut-brain communication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominy, S.S.; Lynch, C.; Ermini, F.; Benedyk, M.; Marczyk, A.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.J.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Park, C.H.K.; Yang, J.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, S.; Ahn, Y.M. Comparison of serum microbiome composition in bipolar and major depressive disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 123, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.J.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Park, C.H.K.; Yang, J.; Kim, Y.-K.; Ahn, Y.M. The association between serum microbial DNA composition and symptoms of depression and anxiety in mood disorders. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baffert, C.; Kpebe, A.; Avilan, L.; Brugna, M. Hydrogenases and H2 metabolism in sulfate-reducing bacteria of the Desulfovibrio genus. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2019, 74, 143–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Baumont, A.; Bortoluzzi, A.; de Aguiar, B.W.; Scotton, E.; Guimarães, L.S.P.; Kapczinski, F.; Cristiano da Silva, T.B.; Manfro, G.G. Anxiety disorders in childhood are associated with youth IL-6 levels: A mediation study including metabolic stress and childhood traumatic events. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 115, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocan, D.; Cassard, A.M.; Becquemont, L.; Verstuyft, C.; Voican, C.S.; El Asmar, K.; Colle, R.; David, D.; Trabado, S.; Feve, B.; Chanson, P.; Perlemuter, G.; Corruble, E. Blood microbiota and metabolomic signature of major depression before and after antidepressant treatment: A prospective case–control study. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2021, 46, E358–E368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.C.; Sheikh Andalibi, M.; Wandro, S.; Weldon, K.C.; Sepich-Poore, G.D.; Carpenter, C.S.; Fraraccio, S.; Franklin, D.; Ludicello, J.E.; Letendre, S.; Gianella, S.; Grant, I.; Ellis, R.J.; Heaton, R.K.; Knight, R.; Swafford, A.D. Signatures of HIV and major depressive disorder in the plasma microbiome. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olde Loohuis, L.M.; Mangul, S.; Ori, A.P.; Jospin, G.; Koslicki, D.; Yang, H.T.; Wu, T.; Boks, M.P.; Lomen-Hoerth, C.; Wiedau-Pazos, M.; Cantor, R.M.; de Vos, W.M.; Kahn, R.S.; Eskin, E.; Ophoff, R.A. Transcriptome analysis in whole blood reveals increased microbial diversity in schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.I.; Seo, J.H.; Park, C.I.; Kim, S.T.; Kim, Y.K.; Jang, J.K.; Kwon, C.O.; Jeon, S.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.J. Microbiome analysis of circulating bacterial extracellular vesicles in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 77, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadekov, T.S.; Boyko, A.N.; Omarova, M.A.; Rogovskii, V.S.; Zhilenkova, O.G.; Zatevalov, A.M.; Mironov, A.Y. Evaluation of the structure of the human microbiome in multiple sclerosis by the concentrations of microbial markers in the blood. Klin. Lab. Diagn. 2022, 67, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, B. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in human hypertension: A systematic review of observational studies. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 650227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendhran, J.; Shankar, M.; Dinakaran, V.; Rathinavel, A.; Gunasekaran, P. Contrasting circulating microbiome in cardiovascular disease patients and healthy individuals. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 5118–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koren, O.; Spor, A.; Felin, J.; Fåk, F.; Stombaugh, J.; Tremaroli, V.; Behre, C.J.; Knight, R.; Fagerberg, B.; Ley, R.E.; Bäckhed, F. Human oral, gut, and plaque microbiota in patients with atherosclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4592–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifullina, D.M.; Pozdeev, O.K.; Khayrullin, R.N. Blood microbiome of patients with atherosclerosis. ATERO-SCLEROZ 2023, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, G.; Ramprasath, T.; Mithieux, G. Human microbiota: A key player in the etiology and pathophysiology of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1081722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lu, H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Dong, C. Associations between peripheral blood microbiome and the risk of hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2021, 34, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Khan, I.; Usman, M.; Jianye, Z.; Wei, Z.X.; Ping, X. .; Lizhe, A. Analysis of the blood bacterial composition of patients with acute coronary syndrome and chronic coronary syndrome. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 943808. [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Khan, I.; Kakakhel, M.A.; Xiaowei, Z.; Ting, M.; Ali, I. .; Lizhe, A. Comparison of microbial populations in the blood of patients with myocardial infarction and healthy individuals. Front. Microbiol. 13, 845038. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Ye, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wan, Z.; Ye, X.; Liu, J. Potential biomarkers of acute myocardial infarction based on the composition of the blood microbiome. Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 556, 117843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbois, A.C.; Ciocan, D.; Saadoun, D.; Perlemuter, G.; Cacoub, P. Specific microbiome profile in Takayasu’s arteritis and giant cell arteritis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, R.; Barve, K. Gut microbiome: a promising target for management of respiratory diseases. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 2679–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chunxi, L.; Haiyue, L.; Yanxia, L.; Jianbing, P.; Jin, S. The gut microbiota and respiratory diseases: new evidence. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Teo, S.M.; Méric, G.; Tang, H.H.; Zhu, Q.; Sanders, J.G.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Verspoor, K.; Vartiainen, V.A.; Jousilahti, P.; Lahti, L. The gut microbiome is a significant risk factor for future chronic lung disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 943–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçam, M.; Lynch, S.V. The gut–airway microbiome axis in health and respiratory diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budden, K.F.; Shukla, S.D.; Rehman, S.F.; Bowerman, K.L.; Keely, S.; Hugenholtz, P.; Armstrong-James, D.P.; Adcock, I.M.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Chung, K.F.; Hansbro, P.M. Functional effects of the microbiota in chronic respiratory disease. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 907–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santacroce, L.; Charitos, I.A.; Ballini, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Luperto, P.; De Nitto, E.; Topi, S. The human respiratory system and its microbiome at a glimpse. Biology 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belizário, J.; Garay-Malpartida, M.; Faintuch, J. Lung microbiome and origins of respiratory diseases. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2023, 4, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, J.; Zhou, X. Lung microbiome: new insights into the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, J.D.; Castaldi, P.J.; Chase, R.P.; Yun, J.H.; Lee, S.; Liu, Y.Y. . & COPDGene Investigators. Peripheral blood microbial signatures in COPD. bioRxiv 2020, 2020–05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Choi, J.P.; Yang, J.; Won, H.K.; Park, C.S.; Song, W.J. . & Cho, Y.S. Metagenome analysis using serum extracellular vesicles identified distinct microbiota in asthmatics. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbeta, E.; López-Aladid, R.; Bueno-Freire, L.; Llonch, B.; Palomeque, A.; Motos, A.; Mellado-Artigas, R.; Zattera, L.; Ferrando, C.; Soler, A.; Fernández-Barat, L.; Torres, A. Biological effects of pulmonary, blood, and gut microbiome alterations in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. ERJ Open Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, A.; Pozuelo, M.; Poca, M.; Gely, C.; Nieto, J. C.; Torras, X.; Guarner, C. Alteration of the serum microbiome composition in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochado-Kith, O.; Rava, M.; Berenguer, J.; González-García, J.; Rojo, D.; Díez, C.; Hontañon, V.; Virseda-Berdices, A.; Ibañez-Samaniego, L.; Llop-Herrera, E.; Olveira, A.; Pérez-Latorre, L.; Barbas, C.; Fernández-Rodríguez, A.; Resino, S.; Jiménez-Sousa, M. A. Altered blood microbiome in patients with HCV-related Child-Pugh class B cirrhosis. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Tang, C.; Zhao, X.; He, Q.; Li, J. Identification and characterization of blood and neutrophil-associated microbiomes in patients with severe acute pancreatitis using next-generation sequencing. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, P.; Liangpunsakul, S.; Christensen, J. E.; Shah, V. H.; Kamath, P. S.; Gores, G. J.; TREAT Consortium. The circulating microbiome signature and inferred functional metagenomics in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2018, 67, 1284–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedgaudas, R.; Bajaj, J. S.; Skieceviciene, J.; Varkalaite, G.; Jurkeviciute, G.; Gelman, S.; Kupcinskas, J. Circulating microbiome in patients with portal hypertension. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2029674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, D.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Velmurugan, G. Exploring the diversity of blood microbiome during liver diseases: Unveiling novel diagnostic and therapeutic avenues. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, T.; Horiba, K.; Kamei, H.; Takeuchi, S.; Suzuki, T.; Torii, Y.; Ito, Y. Temporal dynamics of the plasma microbiome in recipients at early post-liver transplantation: A retrospective study. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santol, J.; Whittle, E.; Brunnthaler, L.; Laferl, V.; Kern, A.; Ortmayr, G.; Starlinger, P. The blood microbiome and its impact on hepatic failure after liver surgery. HPB 2024, 26, S604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, A.; Raj, D. S. The gut microbiome, kidney disease, and targeted interventions. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio-Maia, B.; Simões-Silva, L.; Pestana, M.; Araujo, R.; Soares-Silva, I. J. The role of the gut microbiome on chronic kidney disease. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 96, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khodor, S.; Shatat, I. F. Gut microbiome and kidney disease: A bidirectional relationship. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2017, 32, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nallu, A.; Sharma, S.; Ramezani, A.; Muralidharan, J.; Raj, D. Gut microbiome in chronic kidney disease: Challenges and opportunities. Transl. Res. 2017, 179, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armani, R. G.; Ramezani, A.; Yasir, A.; Sharama, S.; Canziani, M. E.; Raj, D. S. Gut microbiome in chronic kidney disease. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2017, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobby, G. P.; Karaduta, O.; Dusio, G. F.; Singh, M.; Zybailov, B. L.; Arthur, J. M. Chronic kidney disease and the gut microbiome. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2019, 316, F1211–F1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Y.; Chen, D. Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, J. R.; Vaziri, N. D.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y. Y. Microbiome–metabolome reveals the contribution of gut–kidney axis on kidney disease. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Fan, Y.; Li, A.; Shen, Q.; Wu, J.; Ren, L.; Lu, H.; Ding, S.; Ren, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, W. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in chronic kidney disease. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xu, X.; Chao, L.; Chen, K.; Shao, A.; Sun, D.; Hong, Y.; Hu, R.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, N.; Xiao, Y. Alteration of the gut microbiome in chronic kidney disease patients and its association with serum free immunoglobulin light chains. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 609700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, N.; Kakuta, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Yamaguchi, R.; Uchino, E.; Murashita, K.; Nakaji, S.; Imoto, S.; Yanagita, M.; Okuno, Y. Metagenomic profiling of gut microbiome in early chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourountzis, T.; Lioulios, G.; Fylaktou, A.; Moysidou, E.; Papagianni, A.; Stangou, M. Microbiome in chronic kidney disease. Life 2022, 12, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossola, M.; Sanguinetti, M.; Scribano, D.; Zuppi, C.; Giungi, S.; Luciani, G.; Torelli, R.; Posteraro, B.; Fadda, G.; Tazza, L. Circulating bacterial-derived DNA fragments and markers of inflammation in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, N.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Jiang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, Q.; Zou, Y.; Feng, N. The pelvis urinary microbiome in patients with kidney stones and clinical associations. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges-Knafl, D.; Pichler, P.; Zimprich, A.; Hotzy, C.; Barousch, W.; Lang, R. M.; Lobmeyr, E.; Baumgartner-Parzer, S.; Wagner, L.; Winnicki, W. The urinary microbiome shows different bacterial genera in renal transplant recipients and non-transplant patients at time of acute kidney injury: A pilot study. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, R.; Merino-Ribas, A.; Pereira, L.; Campos, J.; Silva, N.; Alencastre, I. S.; Pestana, M.; Sampaio-Maia, B. The urogenital microbiome in chronic kidney disease patients on peritoneal dialysis. Nefrologia 2024, 44, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Sheng, J.; Hu, L.; Zhang, B.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Lin, H.; Lydia, B.; Sun, Y. Salivary microbiome in chronic kidney disease: What is its connection to diabetes, hypertension, and immunity? J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wu, G.; Liu, W.; Fan, Y.; Song, W.; Wu, J.; Gao, D.; Gu, X.; Jing, S.; Shen, Q.; Ren, L. Characteristics of human oral microbiome and its non-invasive diagnostic value in chronic kidney disease. Biosci. Rep. 2022, 42, BSR20210694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes-Silva, L.; Araujo, R.; Pestana, M.; Soares-Silva, I.; Sampaio-Maia, B. The microbiome in chronic kidney disease patients undergoing hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 130, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehedy, E.; Shatat, I. F.; Al Khodor, S. The human microbiome in chronic kidney disease: A double-edged sword. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 790783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Fang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Shi, G.; Guo, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R. Role of symbiotic microbiota dysbiosis in the progression of chronic kidney disease accompanied with vascular calcification. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1306125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiryluk, K.; Li, Y.; Sanna-Cherchi, S.; Rohanizadegan, M.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Geographic differences in genetic susceptibility to IgA nephropathy: GWAS replication study and geospatial risk analysis. PLOS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N. B.; Nigwekar, S. U.; Kalim, S.; Lelouvier, B.; Servant, F.; Dalal, M.; Krinsky, S.; Fasano, A.; Tolkoff-Rubin, N.; Allegretti, A. S. The gut and blood microbiome in IgA nephropathy and healthy controls. Kidney360 2021, 2, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, S.; Araujo, R.; Merino-Riba, A.; Lelouvier, B.; Servant, F.; Quelhas-Santos, J.; Pestana, M.; Sampaio-Maia, B. Blood, gut, and oral microbiome in kidney transplant recipients. Indian J. Nephrol. 2023, 33, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffitt, C.; Bidkhori, G.; Moyes, D.; Shoaie, S. Disease, drugs and dysbiosis: Understanding microbial signatures in metabolic disease and medical interventions. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietek, T.; Rath, E. Inflammation meets metabolic disease: gut feeling mediated by GLP-1. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Chu, H. The critical role of gut microbiota in obesity. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 1025706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnicar, F.; Berry, S.E.; Valdes, A.M.; Nguyen, L.H.; Drew, D.A.; Leeming, E.; Gibson, R.; Roy, C. Le; Khatib, A.; Francis, L.; et al. Microbiome Connections with Host Metabolism and Habitual Diet from 1,098 Deeply Phenotyped Individuals. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestopalov, A. V.; Kolesnikova, I.M.; Gaponov, A.M.; Grigoryeva, T. V.; Khusnutdinova, D.R.; Kamaldinova, D. R. Rumyantsev, S.A. Effect of Metabolic Type of Obesity on Blood Microbiome. Probl. Biol. Med. Pharm. Chem. 2022, 25, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakaroun, R.M.; Massier, L.; Heintz-buschart, A.; Said, N.; Fallmann, J.; Crane, A.; Schütz, T.; Dietrich, A.; Blüher, M.; Stumvoll, M.; et al. Circulating Bacterial Signature Is Linked to Metabolic Disease and Shifts with Metabolic Alleviation after Bariatric Surgery. Genome Med. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabebe, E.; Robert, F.O.; Agbalalah, T.; Orubu, E.S.F. Microbial Dysbiosis-Induced Obesity: Role of Gut Microbiota in Homoeostasis of Energy Metabolism. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 123, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantaram, D.; Hoyd, R.; Blaszczak, A.M.; Antwi, L.; Jalilvand, A.; Wright, V.P.; Liu, J.; Smith, A.J.; Bradley, D.; Lafuse, W.; et al. Obesity-Associated Microbiomes Instigate Visceral Adipose Tissue in Fl Ammation by Recruitment of Distinct Neutrophils. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Huang, W.; Lin, Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; Ng, S.C. Gut Microbiota in Patients with Obesity and Metabolic Disorders — a Systematic Review. Genes Nutr. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoelson, S.E.; Herrero, L.; Naaz, A. Obesity, Inflammation, and Insulin Resistance. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2169–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumida, K.; Han, Z.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Mims, T.S.; Bajwa, A.; Demmer, R.T.; Datta, S.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Pierre, J.F. Circulating Microbiota in Cardiometabolic Disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 892232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesnikova, I.M.; Gaponov, A.M.; Roumiantsev, S.A.; Karbyshev, M.S.; Grigoryeva, T. V.; Makarov, V. V.; Yudin, S.M.; Borisenko, O. V.; Shestopalov, A. V. Relationship between Blood Microbiome and Neurotrophin Levels in Different Metabolic Types of Obesity. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 58, 1937–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaemi, F.; Fateh, A.; Sepahy, A.A.; Zangeneh, M.; Ghanei, M.; Siadat, S.D. Blood Microbiota Composition in Iranian Pre-Diabetic and Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Hum. Antibodies 2021, 29, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, S.; Nirmalkar, K.; Hoyo-Vadillo, C.; García-Espitia, M.; Ramírez-Sánchez, D.; García-Mena, J. Gut Microbiome Production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Obesity in Children. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheithauer, T.P.M.; Rampanelli, E.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Vallance, B.A.; Verchere, C.B.; van Raalte, D.H.; Herrema, H. Gut Microbiota as a Trigger for Metabolic Inflammation in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Zhu, L.; Yang, L. Gut and Obesity/Metabolic Disease: Focus on Microbiota Metabolites. MedComm 2022, 3, e171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goraya, M. U.; Li, R.; Gu, L.; Deng, H.; Wang, G. Blood Stream Microbiota Dysbiosis Establishing New Research Standards in Cardio-Metabolic Diseases, A Meta-Analysis Study. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, J.; Serino, M.; Lange, C.; Chabo, C.; Iacovoni, J.; Mondot, S.; Lepage, P.; Klopp, C.; Mariette, J.; Bouchez, O.; et al. Involvement of Tissue Bacteria in the Onset of Diabetes in Humans: Evidence for a Concept. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 3055–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massier, L.; Chakaroun, R.; Tabei, S.; Crane, A.; Didt, K.D.; Fallmann, J.; Von Bergen, M.; Haange, S.B.; Heyne, H.; Stumvoll, M.; et al. Adipose Tissue Derived Bacteria Are Associated with Inflammation in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Gut 2020, 69, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Yang, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, C.; Chen, R. ,... & Luo, F. The Profile of Blood Microbiome in New-Onset Type 1 Diabetes Children. ISCIENCE 2024, 27, 110252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson-Knodell, C.L.; Rubio-Tapia, A. Gluten-Related Disorders From Bench to Bedside. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 693–704.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, A.; Petruzziello, C.; Brigida, M.; Morabito Loprete, M.R.; Savioli, G.; Migneco, A.; Ojetti, V. Gut Microbiota Alteration and Its Modulation with Probiotics in Celiac Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGeorge, K.C.; Frye, J.W.; Stein, K.M.; Rollins, L.K.; McCarter, D.F. Celiac Disease and Gluten Sensitivity. Prim. Care - Clin. Off. Pract. 2017, 44, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanciu, D.; Staykov, H.; Dragomanova, S.; Tancheva, L.; Pop, R.S.; Ielciu, I.; Crisan, G. Gluten Unraveled: Latest Insights on Terminology, Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, Dietary Strategies, and Intestinal Microbiota Modulations—A Decade in Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valitutti, F.; Cucchiara, S.; Fasano, A. Celiac Disease and the Microbiome. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, J.U. The Microbiome in Celiac Disease: Beyond Diet-Genetic Interactions. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2016, 83, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serena, G.; Davies, C.; Cetinbas, M.; Sadreyev, R.I.; Fasano, A. Analysis of Blood and Fecal Microbiome Profile in Patients with Celiac Disease. Hum. Microbiome J. 2019, 11, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, I.; Serena, G.; Cetinbas, M.; Kenyon, V.; Martin, V.M.; Harshman, S.G.; Zomorrodi, A.R.; Sadreyev, R.I.; Fasano, A.; Leonard, M.M. Characterization of the Blood Microbiota in Children with Celiac Disease. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2021, 2, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, G.; Rybakova, D.; Fischer, D.; et al. Microbiome definition re-visited: old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome 2020, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biology 2016, 14, e1002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Païssé, S.; Valle, C.; Servant, F.; Courtney, M.; Burcelin, R.; Amar, J.; Lelouvier, B. Comprehensive description of blood microbiome from healthy donors assessed by 16S targeted meta- genomic sequencing. Transfusion 2016, 56, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, C.; Wang, W.; Dzieciatkowska, M.; Cortese, M.; Hansen, K.C.; Becerra, A.; Thangaswamy, S.; Nizamutdinova, I.; Moon, J.-Y.; Stern, L.J.; Gashev, A.A.; Zawieja, D.; Santambrogio, L. Quantitative Profiling of the Lymph Node Clearance Capacity. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 11253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rife, R.R. Filterable bodies seen with the Rife microscope. Science 1931, 74, 10–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuerthele-Caspe, V. The presence of consistently recurring invasive mycobacterial forms in tumor cells. NY Microsc Soc Bull 1948, 2, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, C.M.; Nelson, E.L.; Lehman, E.L.; Howard, D.H.; Primes, G. The isolation of unidentified pleomorphic bacteria from the blood of patients with chronic illness. J Chronic Dis 1955, 2, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.A.; Weitzman, S.; Edberg, S.C.; Casey, J.I. Bacteremia after the use of an oral irrigation device. A controlled study in subjects with normalappearing gingiva: comparison with use of toothbrush. Ann Intern Med 1974, 80, 510–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, B.; Coovadia, Y.; Vayej, A.C. An investigation of the frequency of bacteraemia following dental extraction, tooth brushing and chewing. Cardiovasc J Afr 2012, 23, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potgieter, M.; Bester, J.; Kell, D.B.; Pretorius, E. The dormant blood microbiome in chronic, inflammatory diseases. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2015, 39, 567-591. https://academic.oup.com/femsre/article/39/4/567/2467761.

- Domingue, G.J.; Woody, H.B. Bacterial persistence and expression of disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 1997, 10, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damgaard, C.; Magnussen, K.; Enevold, C.; Nilsson, M.; Tolker-Nielsen, T.; Holmstrup, P.; Nielsen, C.H. Viable bacteria associated with red blood cells and plasma in freshly drawn blood donations. PloSone. 2015, 10, e0120826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markova, N.; Slavchev, G.; Michailova, L. Presence of mycobacterial L-forms in blood: challenge of BCG vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015, 11, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosiewski, T.; Ludwig-Galezowska, A.H.; Huminska, K.; Sroka-Oleksiak, A.; Radkowski, P.; Salamon, D.; Wojciechowicz, J.; Kus-Slowinska, M.; Bulanda, M.; Wolkow, P.P. Comprehensive detection and identification of bacterial DNA in the blood of patients with sepsis and healthy volunteers using next-generation sequencing method - the observation of DNAemia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2017, 36, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, E.; Leonard, M.O.; Harrison, R.; Gant, T.W.; Tonge, D.P. Multi-Method Characterization of the Human Circulating Microbiome. Front Microbiol 2019, 9, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | Increased compared to healthy controls | Decreased compared to healthy controls | Reff. |

| Individuals to develop CVD | Proteobacteria | - | [33] |

| CVD | Proteobacteria (F. Pseudomonaceae, Cl. Gammaproteobacteria) | Firmicutes (F. Staphylococcaceae) | [66] |

|

Actinobacteria Bacteriophages |

- | [34] | |

| Hypertension | Proteobacteria | Firmicutes; Bacteroidetes | [70] |

| Acute coronary syndrome |

Proteobacteria Bacteroidota |

- | [71] |

| Chronic coronary syndrome |

Bacteroidota Firmicutes |

Proteobacteria | [71] |

| Myocardial infarction | Actinobacteria | - | [72] |

| Vasculitis (Takayasu's arteritis) |

Clostridia Cytophagia Deltaproteobacteria |

Bacilli | [74] |

| Vasculitis (giant cell arteritis) |

Cytophagaceae Rhodococcus |

[74] | |

| CVD mortality |

Enhydrobacter Kocuria |

Paracoccus | [35] |

| Condition | Increased compared to healthy controls | Decreased compared to healthy controls | Reff. |

| Obesity |

Actinobacteria Acidobacteria Bacteroidetes Firmicutes Proteobacteria Saccharibacteria (TM7) Verrucomicrobia |

- | [121] |

| Type 1 Diabetes |

Actinobacteriota Bacteroidota Firmicutes Proteobacteria (Sphingomonas, Caulobacter, Stenotrophomonas) |

- | [136] |

| Type 2 Dyabetes |

Proteobacteria (Sediminibacterium, Ralstonia, Alishewanella, Thahibacter) Actinobacteriota (Actinotalea, Pseudoclavibacter, Atopobidum cl.) Firmicutes (Clostridium coccoides) |

Bacteroidota (Bacteroides) Proteobacteria (Aquabacterium, Xanthomonas, Bukholderiaceae, Rhodospirillales, Myxococcales, Acinetobacter) Firmicutes (Bacillaceae, Lactobacillus, Lactococcus) Actinobacteriota (Pseudonocardia) |

[41] [133] [134] [50] [135] |

| Celiac Disease |

Firmicutes (Bacillales), Proteobacteria Bacteroidota (Bacteroides) |

Firmicutes (Clostridiales) Actinobacteriota (Bifidobacterium) Proteobacteria (Campylobacterales: Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli, Helicobacteraceae) Bacteroidota (Odoribacteraceae, Bacteroides acidifaciens) |

[143] [144] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).