Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

17 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

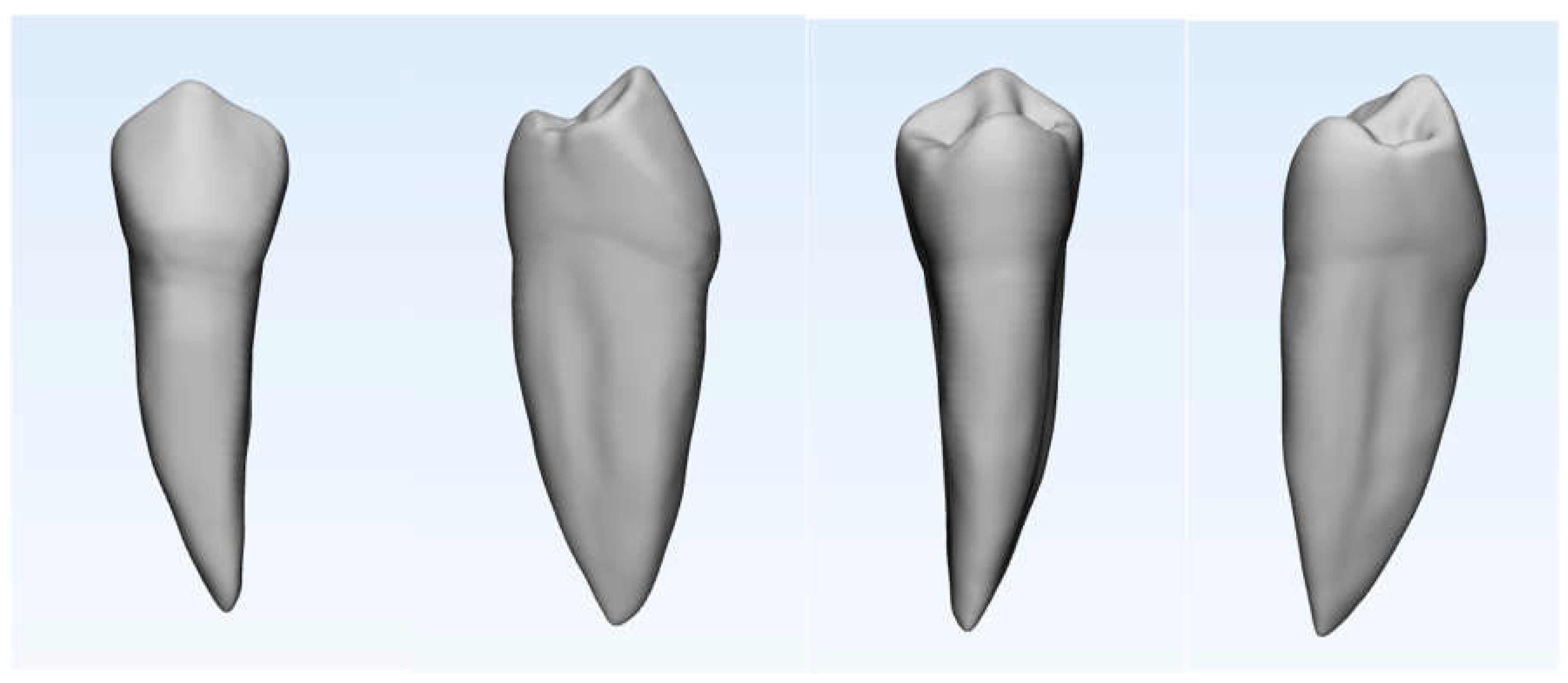

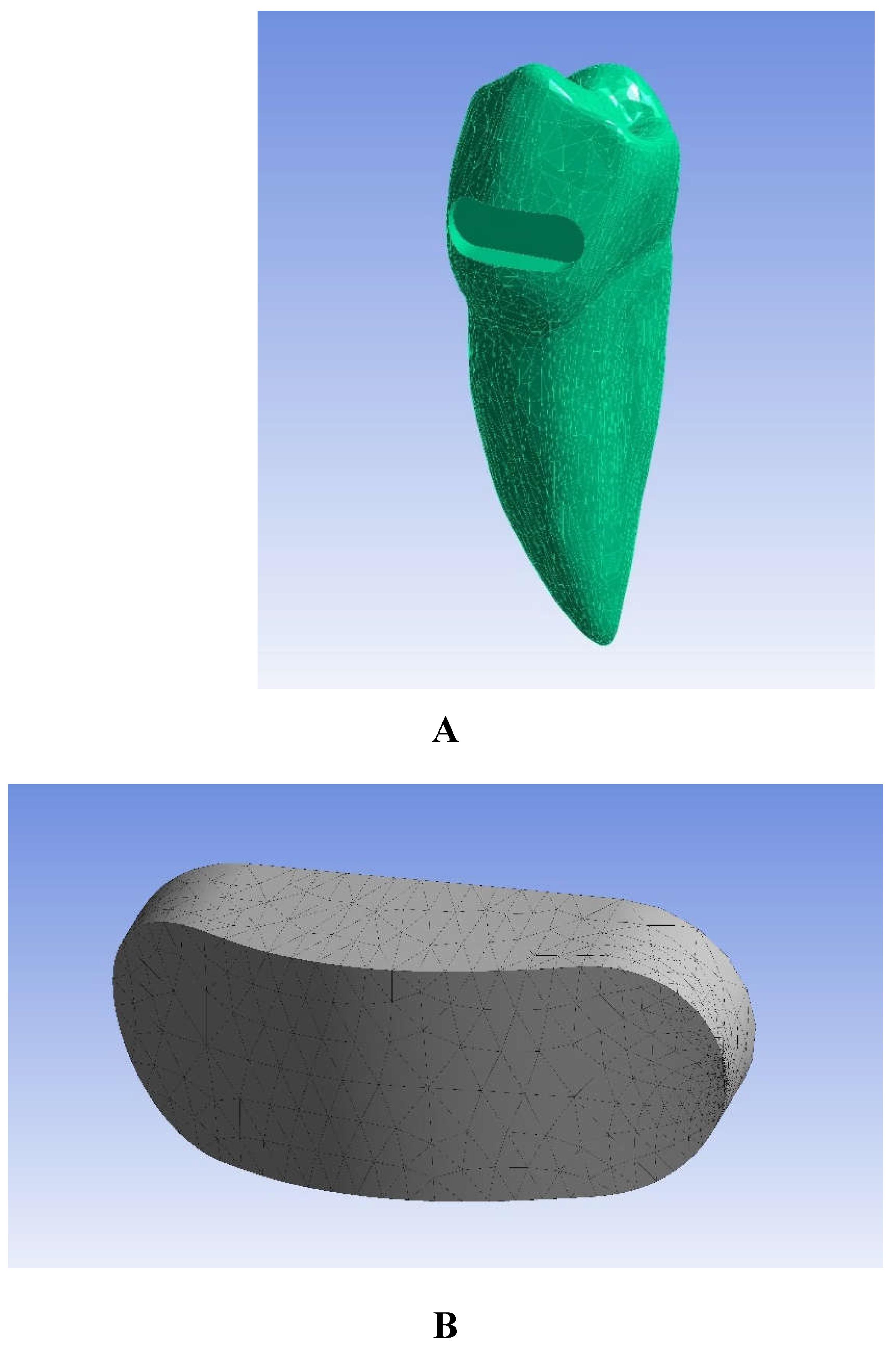

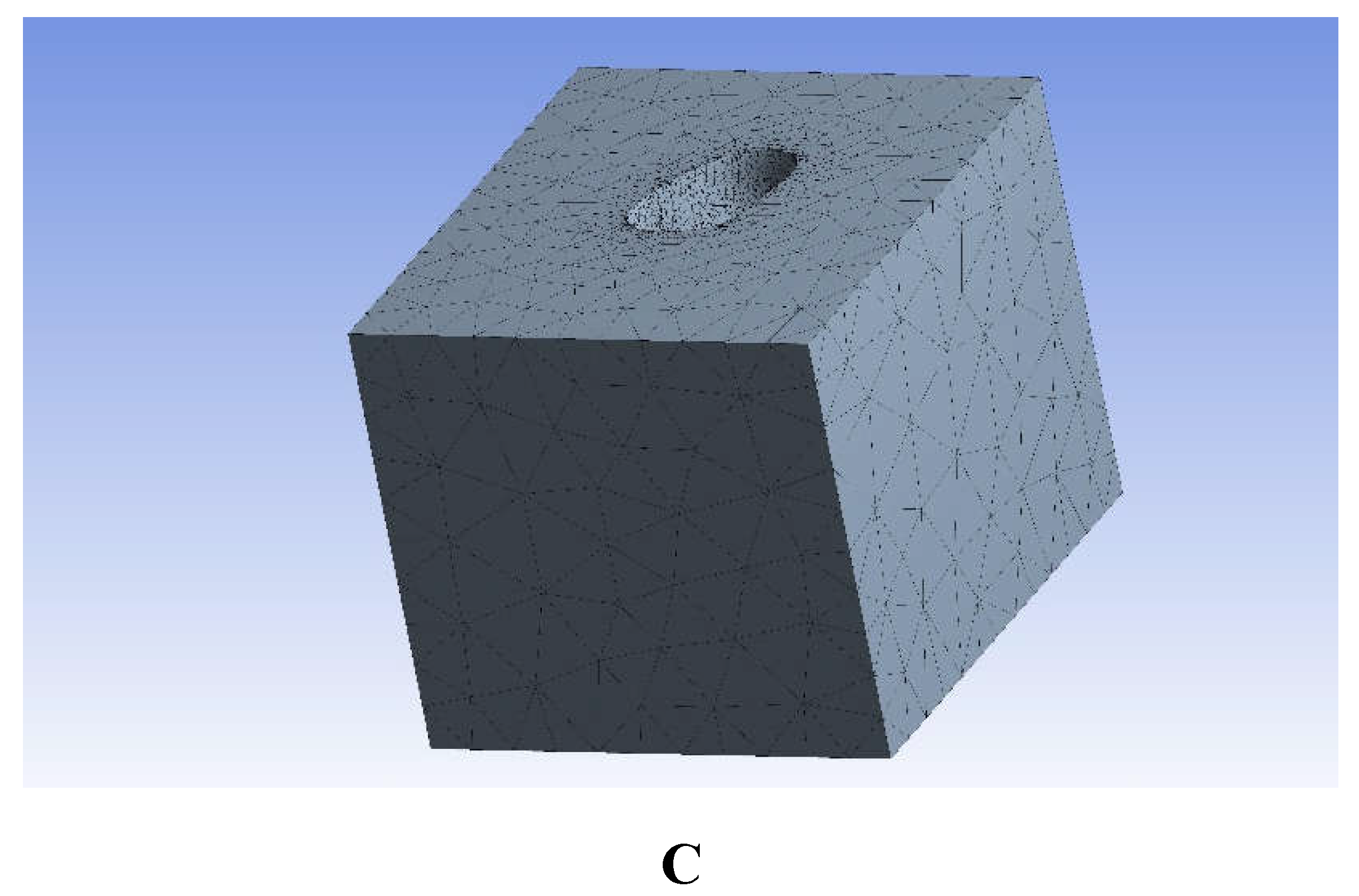

2.2. 3D Model and Mesh

2.3. Materials Properties and Finite Element Analysis

3. Results

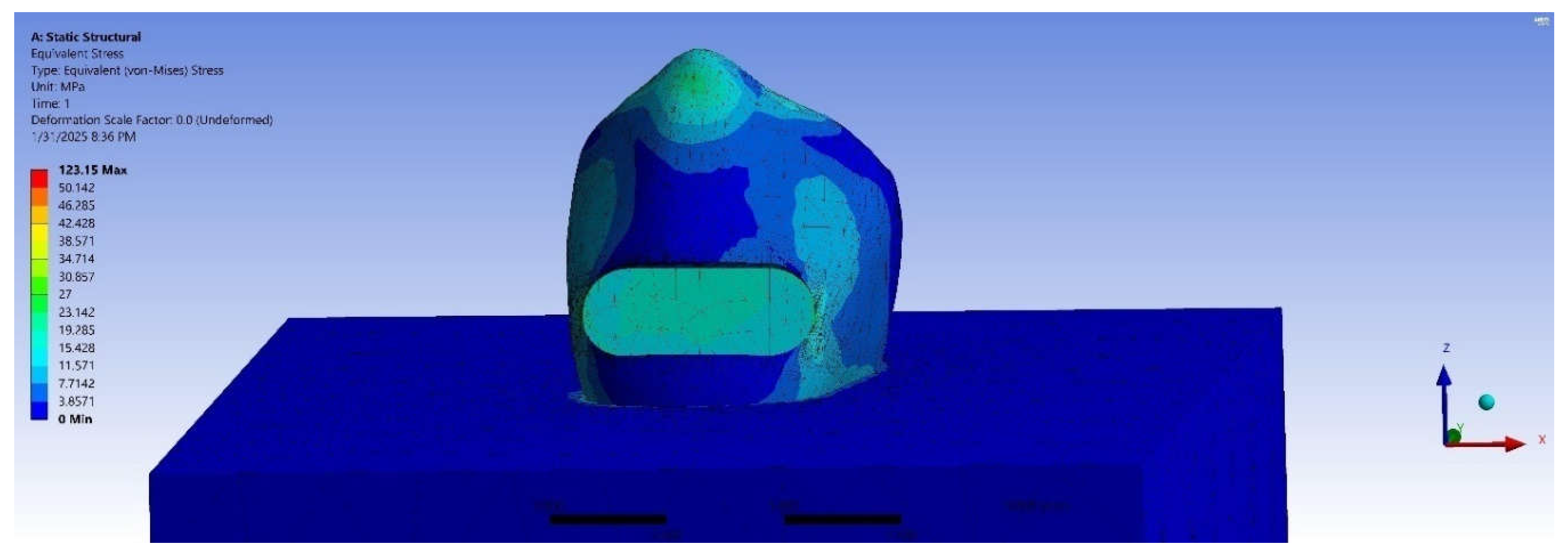

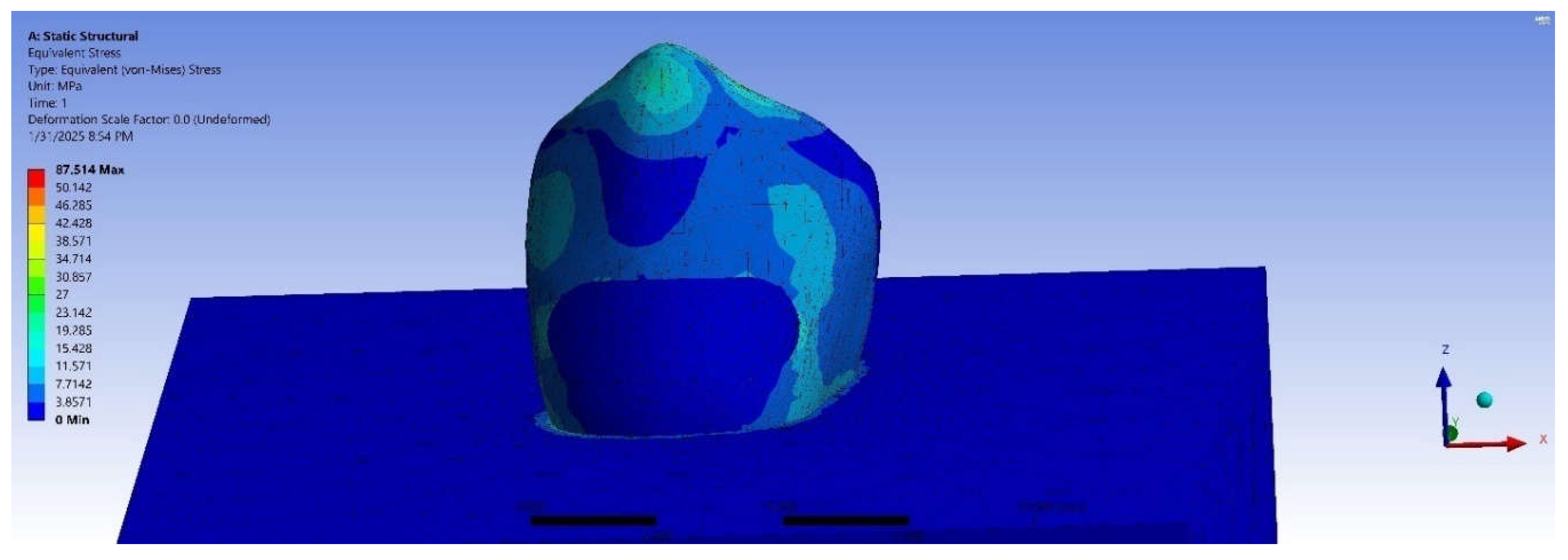

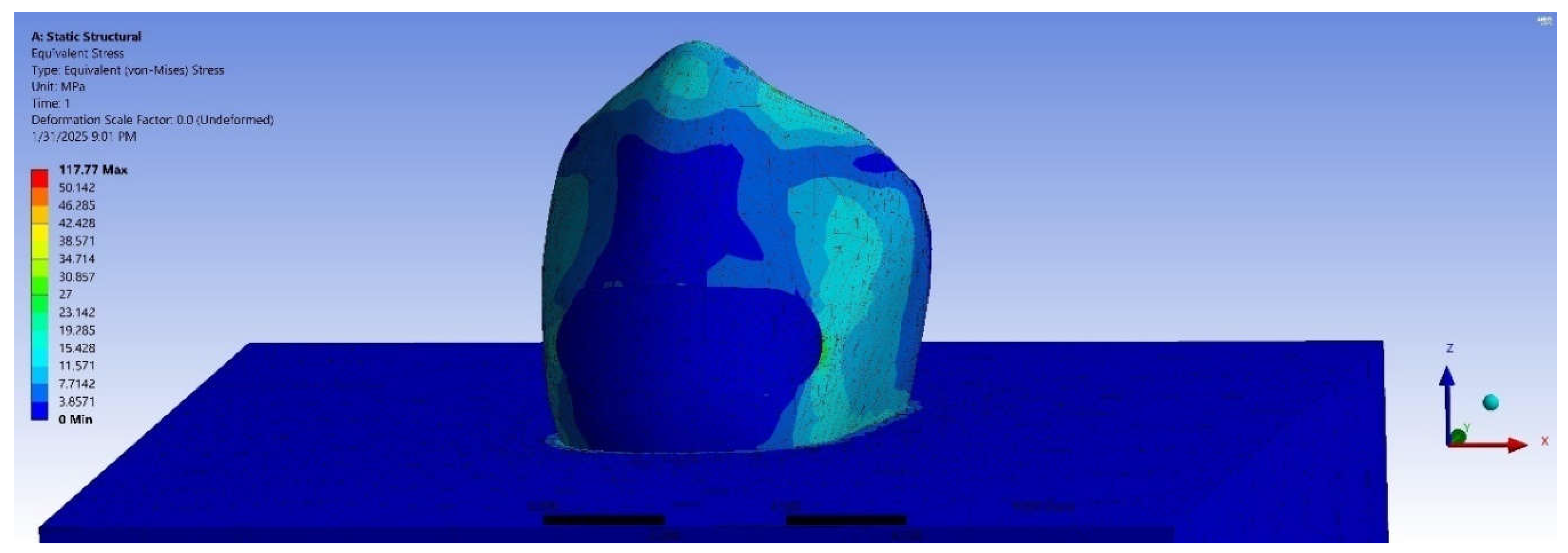

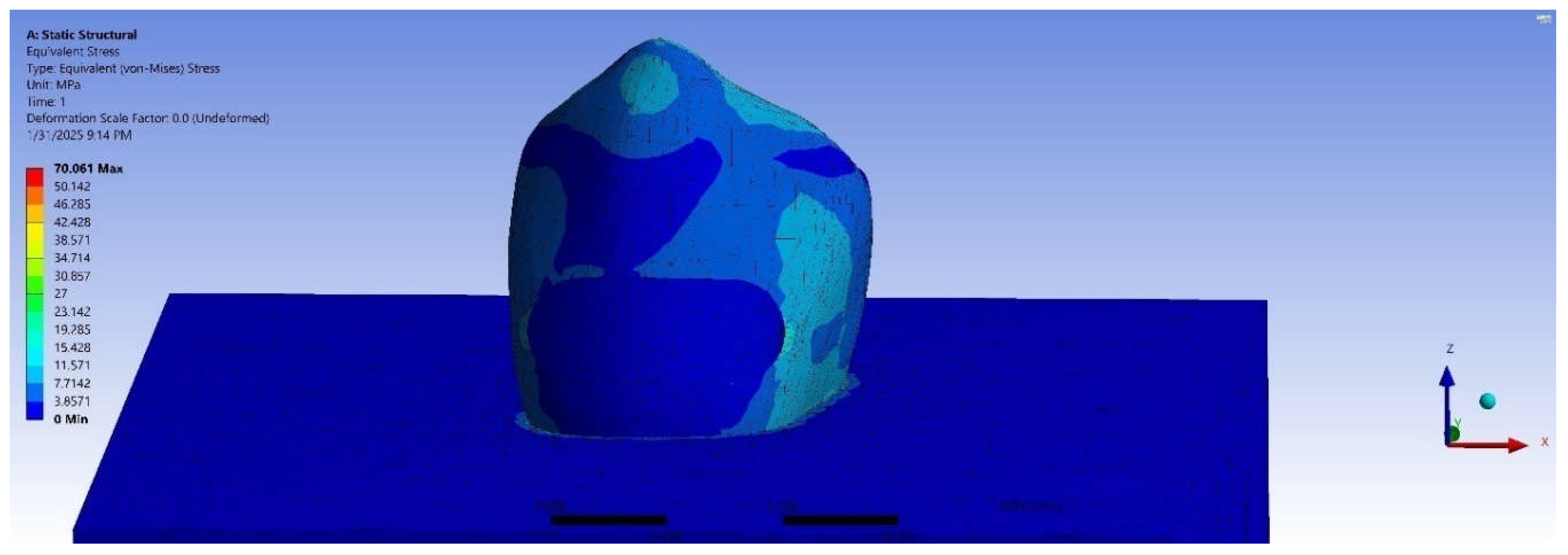

3.1. Stress Distribution in Mandibular Premolars

| Applied Load (N) | A1 (MPa) | A2 (MPa) | A3 (MPa) | A4 (MPa) |

| 100 | 49.23 | 35.00 | 47.10 | 28.02 |

| 150 | 73.88 | 52.50 | 70.66 | 42.03 |

| 200 | 98.51 | 70.01 | 94.21 | 56.04 |

| 250 | 123.15 | 87.51 | 117.77 | 70.06 |

3.2. Stress Distribution by Restoration Type and Load Levels

3.3. Compare Stress Values at Different Load Levels (Paired t-Tests)

| Pair | Mean Difference | t-value | df | p-value |

| 100N vs. 150N | 24.94 | 5.42 | 3 | 0.012 |

| 100N vs. 200N | 3.76 | 5.38 | 3 | 0.013 |

| 100N vs. 250N | 37.16 | 5.42 | 3 | 0.012 |

| 150N vs. 200N | -21.18 | -5.42 | 3 | 0.012 |

| 150N vs. 250N | 12.22 | 5.42 | 3 | 0.012 |

| 200N vs. 250N | 33.40 | 5.42 | 3 | 0.012 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gönder HY, Mohammadi R, Harmankaya A, Yüksel İB, Fidancıoğlu YD, Karabekiroğlu SJP. Teeth Restored with Bulk–Fill Composites and Conventional Resin Composites; Investigation of Stress Distribution and Fracture Lifespan on Enamel, Dentin, and Restorative Materials via Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. 2023;15(7):1637. [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh J, Fahd JC, McConnell RJJDU. Post-operative sensitivity and posterior composite resin restorations: a review. 2018;45(3):207-13. [CrossRef]

- Mjör IA, Toffentti FJQi. Secondary caries: a literature review with case reports. 2000;31(3).

- Brambilla E, Ionescu ACJOB, Bioactivity MDMAT. Oral biofilms and secondary caries formation. 2021:19-35. [CrossRef]

- Jafari F, Jafari S, Etesamnia PJIej. Genotoxicity, bioactivity and clinical properties of calcium silicate based sealers: a literature review. 2017;12(4):407. [CrossRef]

- Sarfati A, Tirlet GJIJED. Deep margin elevation versus crown lengthening: biologic width revisited. 2018;13(3):334-56.

- Parirokh M, Torabinejad M, Dummer PJIej. Mineral trioxide aggregate and other bioactive endodontic cements: an updated overview–part I: vital pulp therapy. 2018;51(2):177-205. [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Baz P, Argibay-Lorenzo O, Muñoz F, Martin-Biedma B, Darriba IL, Miguéns-Vila R, et al. Periodontal response to a tricalcium silicate material or resin composite placed in close contact to the supracrestal tissue attachment: A histomorphometric comparative study. 2021;25:5743-53. [CrossRef]

- Suhag D. Dental Biomaterials. Handbook of Biomaterials for Medical Applications, Volume 2: Applications: Springer; 2024. p. 235-79.

- Syed AUY, Rokaya D, Shahrbaf S, Martin NJAS. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of stress distribution in a tooth restored with full coverage machined polymer crown. 2021;11(3):1220. [CrossRef]

- Babaei B, Shouha P, Birman V, Farrar P, Prentice L, Prusty GJJotMBoBM. The effect of dental restoration geometry and material properties on biomechanical behaviour of a treated molar tooth: A 3D finite element analysis. 2022;125:104892. [CrossRef]

- Yaman S, Şahin M, Aydin CJJoor. Finite element analysis of strength characteristics of various resin based restorative materials in Class V cavities. 2003;30(6):630-41. [CrossRef]

- Boschian Pest L, Guidotti S, Pietrabissa R, Gagliani MJJoor. Stress distribution in a post-restored tooth using the three-dimensional finite element method. 2006;33(9):690-7. [CrossRef]

- Huang L, Nemoto R, Okada D, Shin C, Saleh O, Oishi Y, et al. Investigation of stress distribution within an endodontically treated tooth restored with different restorations. 2022;17(3):1115-24. [CrossRef]

- Yamanel K, Çaglar A, Gülsahi K, Özden UAJDmj. Effects of different ceramic and composite materials on stress distribution in inlay and onlay cavities: 3-D finite element analysis. 2009;28(6):661-70. [CrossRef]

- Guler M, Guler C, Cakici F, Cakici E, Sen SJNJoCP. Finite element analysis of thermal stress distribution in different restorative materials used in class V cavities. 2016;19(1):30-4. [CrossRef]

- Chung SM, Yap AUJ, Koh WK, Tsai KT, Lim CTJB. Measurement of Poisson's ratio of dental composite restorative materials. 2004;25(13):2455-60. [CrossRef]

- Mesquita RV, Axmann D, Geis-Gerstorfer JJDM. Dynamic visco-elastic properties of dental composite resins. 2006;22(3):258-67. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y-T, Chen C-H, Wang P-F, Chen C-T, Lin C-LJAS. Design of a metal 3D printing patient-specific repairing thin implant for zygomaticomaxillary complex bone fracture based on buttress theory using finite element analysis. 2020;10(14):4738. [CrossRef]

- Dawood SN, Al-Zahawi AR, Sabri LAJAS. Mechanical and thermal stress behavior of a conservative proposed veneer preparation design for restoring misaligned anterior teeth: A 3D finite element analysis. 2020;10(17):5814. [CrossRef]

- Lin P-J, Su K-CJAS. Biomechanical design application on the effect of different occlusion conditions on dental implants with different positions—A finite element analysis. 2020;10(17):5826. [CrossRef]

- Saridena USNG, Sanka GSSJ, Alla RK, AV R, Mc SS, Mantena SRJIJoDM. An overview of advances in glass ionomer cements. 2022;4(4):89-94.

- Park EY, Kang SJYUjom. Current aspects and prospects of glass ionomer cements for clinical dentistry. 2020;37(3):169-78. [CrossRef]

- Lardani L, Derchi G, Marchio V, Carli EJC. One-year clinical performance of Activa™ bioactive-restorative composite in primary molars. 2022;9(3):433. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sabio L, Peñate L, Arregui M, Veloso Duran A, Blanco JR, Guinot FJP. Comparison of shear bond strength and microleakage between activa™ bioactive restorative™ and bulk-fill composites—An in vitro study. 2023;15(13):2840. [CrossRef]

- Adsul PS, Dhawan P, Tuli A, Khanduri N, Singh AJIJoCPD. Evaluation and comparison of physical properties of cention n with other restorative materials in artificial saliva: an in vitro study. 2022;15(3):350. [CrossRef]

- Singbal K, Shan MKW, Dutta S, Kacharaju KRJB, Journal P. Cention N compared to other contemporary tooth-colored restorative materials in terms of fluoride ion releasing efficacy: Validation of a novel caries-prevention-initiative by the Ministry of Health, Malaysia. 2022;15(2):669-76. [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswamy S, Meena N, Shetty A, Kumari A, Naveen DJJoCD. Finite element analysis of stress concentration in Class V restorations of four groups of restorative materials in mandibular premolar. 2008;11(3):121-6. [CrossRef]

- Pai S, Naik N, Patil V, Kaur J, Awasti S, Nayak NJJoISoP, et al. Evaluation and comparison of stress distribution in restored cervical lesions of mandibular premolars: three-dimensional finite element analysis. 2019;9(6):605-11. [CrossRef]

- Bansal P, Seth T, Kumar M, Bhatt M, Arora P, Gupta I, et al. Comparative Evaluation of Stress Distribution and Deformation in Class II Cavities Restored With Two Different Biomimetic Restorative Materials: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. 2024;16(9). [CrossRef]

- Pai S, Bhat V, Patil V, Naik N, Awasthi S, Nayak NJJoISoP, et al. Numerical three-dimensional finite element modeling of cavity shape and optimal material selection by analysis of stress distribution on class V cavities of mandibular premolars. 2020;10(3):279-85. [CrossRef]

- Gomes RR, Zeola LF, Barbosa TAQ, Fernandes Neto AJ, de Araujo Almeida G, Soares PVJPiO. Prevalence of non-carious cervical lesions and orthodontic treatment: a retrospective study. 2022;23(1):17. [CrossRef]

- Villamayor KGG, Codas-Duarte D, Ramirez I, Souza-Gabriel AE, Sousa-Neto MD, Candemil APJAoOB. Morphological characteristics of non-carious cervical lesions. A systematic review. 2024:106050. [CrossRef]

- Browning W, Brackett WW, Gilpatrick RJOD. Two-year clinical comparison of a micro filled and a hybrid resin-based composite in non-carious class V lesions. 2000;25:46-50.

- Srirekha A, Bashetty KJJoCD, Endodontics. A comparative analysis of restorative materials used in abfraction lesions in tooth with and without occlusal restoration: Three-dimensional finite element analysis. 2013;16(2):157-61. [CrossRef]

- Lee WC, Eakle WSJTJopd. Stress-induced cervical lesions: review of advances in the past 10 years. 1996;75(5):487-94. [CrossRef]

- Kantardžić I, Vasiljević D, Blažić L, Lužanin OJCmj. Influence of cavity design preparation on stress values in maxillary premolar: a finite element analysis. 2012;53(6):568-76. [CrossRef]

- Benazzi S, Grosse IR, Gruppioni G, Weber GW, Kullmer OJCoi. Comparison of occlusal loading conditions in a lower second premolar using three-dimensional finite element analysis. 2014;18:369-75. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z-f, Fu B-pJTJoPD. Minimum residual root dentin thickness of mandibular premolars restored with a post: a finite element analysis study. 2024;131(5):878-85. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal S, Sharma S, Sharma CSJC. Finite element analysis and clinical applications of transverse post for the rehabilitation of endodontically treated teeth. 2024;16(7). [CrossRef]

- Soares PV, Machado AC, Zeola LF, Souza P, Galvão A, Montes TC, et al. Loading and composite restoration assessment of various non-carious cervical lesions morphologies–3D finite element analysis. 2015;60(3):309-16. [CrossRef]

| Materials | Modulus of elasticity (MPa) |

Poisson’s ratio(μ) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enamel | 84100 | 0.33 | [29] |

| Dentin | 13700 | 0.31 | [29] |

| Glass–ionomer cement | 10800 | [29] | |

| Activa™ BioActive-Restorative | 2350 | 0.25 | [30] |

| Cention40 | 13000 | 0.3 | [29] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).