1. Introduction

In the era of big knowledge and large models, the scale and complexity of data are increasing exponentially, which brings unprecedented opportunities and challenges for machine learning algorithms. Remote sensing images (RSIs) are acquired from airborne or satellite sensors and analyze surface objects using electromagnetic wave reflection functions, commonly used in computer vision tasks such as image classification, object detection, and change detection. As an important data source for obtaining geospatial information, RSIs play a central role in various areas such as environmental monitoring [

1], urban planning [

2], agricultural supervision [

3], and disaster management [

4]. RSIs provide important information that enables accurate analysis and decision making in these areas. However, the quality of RSIs is inevitably affected by atmospheric turbulence, lighting conditions, noise, motion blur, and intrinsic properties of the sensors during the acquisition process. These imaging conditions and hardware performance limitations result in suboptimal resolution and image quality [

5,

6]. While upgrading physical imaging equipment not only incurs additional costs, but also extends the deployment cycle of remote sensing systems. Conversely, improving the resolution of RSIs can significantly improve the efficiency of data use and provide more accurate and reliable information for scientific research and practical applications. Therefore, this paper aimed at developing super-resolution (SR) methods to improve RSI quality.

Transformer models [

7,

8,

9] are gaining attention due to their remarkable ability to capture long-range dependencies, which is particularly advantageous when processing complex image features. In contrast, CNNs [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] perform shape-adaptive convolutions along tubular features, allowing them to effectively adapt to objects of different shapes. Both approaches offer unique strengths and offer diverse solutions for super-resolution tasks.

In the flourishing of large-scale knowledge and models, the richness of data provides sufficient information for model training, but also puts forward higher requirements for model complexity and efficiency. Although the introduction of advanced technologies such as residual connections and attention mechanisms have significantly improved the performance of CNN-based SR models, challenges related to large model sizes, high computational requirements, and memory usage remain critical research areas. These issues limit the practical use of SR models, especially in resource-constrained environments such as real-time remote sensing applications. To mitigate these limitations, ongoing research focuses on developing more efficient architectures, such as lightweight networks [

15] and pruning techniques [

16].

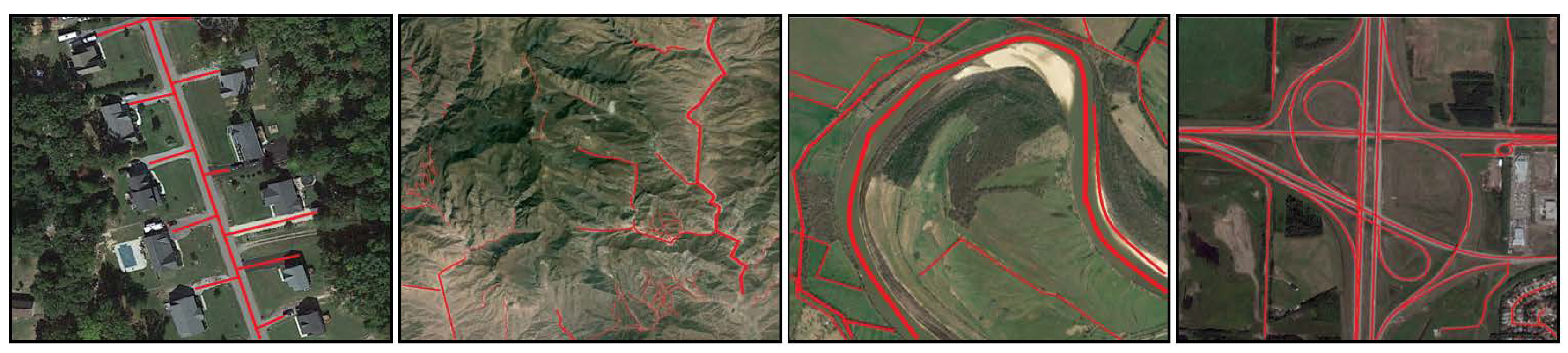

While these efficiency advances have primarily targeted SR models with natural images, RSIs capture highly diverse and irregular structures such as roads, rivers, and other complex ground features, which pose a number of other challenges. These subtleties introduce additional complexity when applying traditional SR methods optimized for more regular and consistent textures. Therefore, traditional SR methods have difficulty in accurately reconstructing RSIs, particularly in preserving the finer details inherent in these image types.

Furthermore, existing SR models designed for natural images often overlook the inherent features of RSIs. This is because RSIs often contain features that vary significantly in size, shape, and texture, requiring the development of special algorithms tailored to these unique features. Traditional convolution methods [

17,

18] fundamentally struggle to effectively capture stripy and irregular features in RSIs, as shown in

Figure 1. Although Transformer-based methods can model long-range dependencies, dividing images into fixed-size patches leads to increased computational complexity, memory consumption, and boundary artifacts that degrade the overall quality of the reconstruction.

To overcome these challenges, we propose a hybrid CNN-Transformer network that includes the strip-like feature superpixel interaction (SFSI) module. This hybrid design combines the Transformer’s ability to capture long-range dependencies with CNNs that perform shape-adaptive convolutions along strip-like features. SFSI combines dynamic snake convolutions [

19], which are very effective in capturing strip-like structures, with superpixel clustering [

20] to reduce computational complexity while preserving critical structural information.

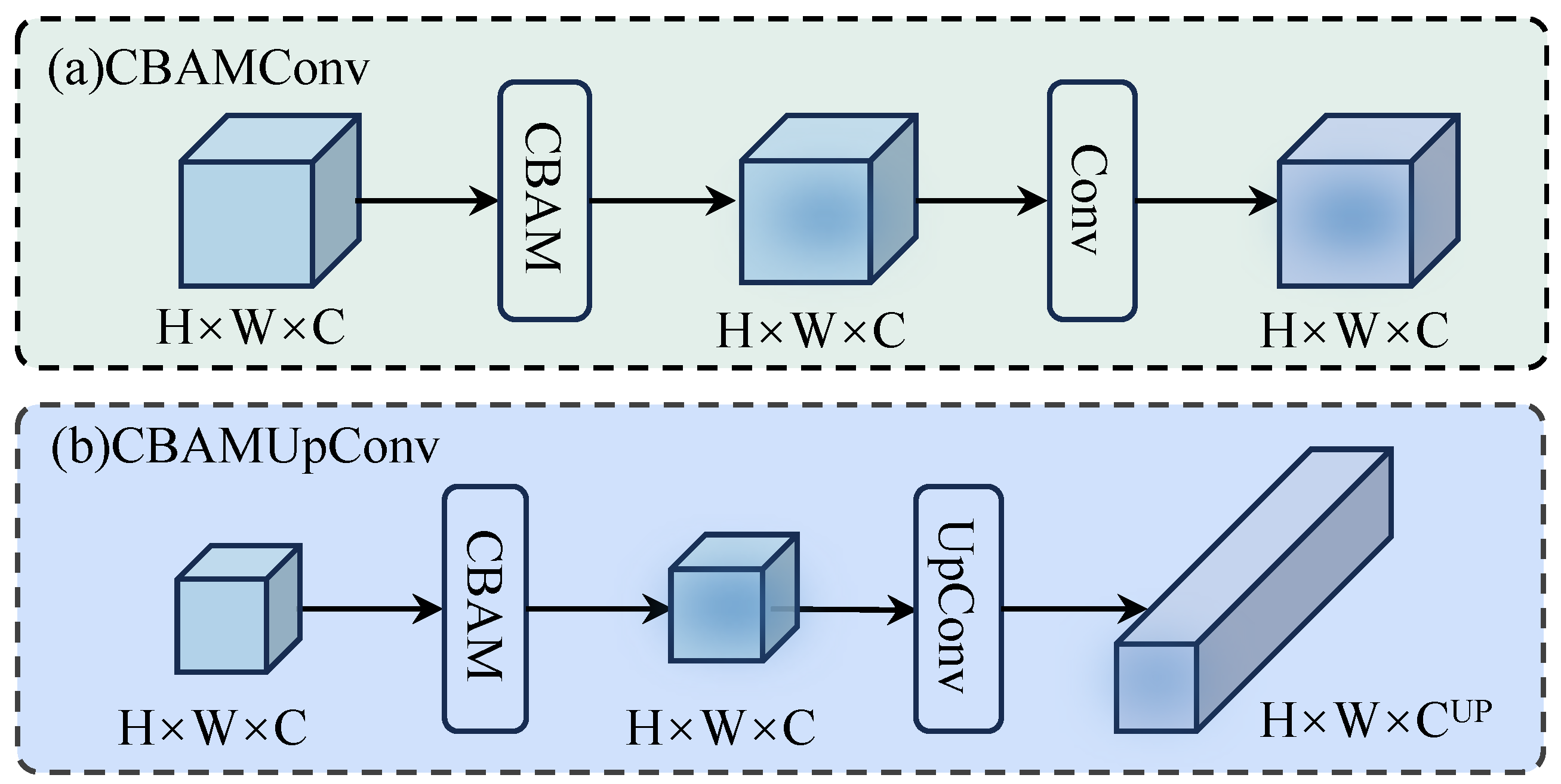

Additionally, existing SR models [

8,

10,

11,

12,

21] typically rely on standard convolutions and PixelShuffle for the final reconstruction phase, which may not fully utilize the available spatial and channel information. To address this limitation, we introduce the convolutional block attention module with upsampling convolution (CBAMUpConv), which leverages the convolutional block attention module (CBAM) [

22] to improve spatial and channel attention during feature extraction. By applying this attention mechanism to local, global, and strip-like features, our method significantly improves the model’s ability to capture and exploit essential structural details, resulting in superior reconstruction performance, especially in preserving strip-like and complex features that are critical for RSIs.

Our contributions are summarized as follows:

We propose a lightweight hybrid CNN-Transformer network that effectively extracts strip-like features in RSIs using dynamic snake convolution.

We innovatively integrate the CBAMUpConv module into the image reconstruction framework, which integrates upsampling convolution with the CBAM attention mechanism to improve both spatial and channel feature learning capabilities.

We validate the effectiveness of the proposed methods through extensive ablation experiments on the AID remote sensing dataset and show significant improvements over existing methods.

2. Related Work

2.1. Conventional Methods for SR

In the context of remote sensing, single-image super-resolution (SISR) refers to the process of reconstructing a high-resolution (HR) image from a single low-resolution (LR) observation, with the aim of revealing finer spatial details that may be lost during image acquisition. Traditional methods for SR include interpolation-based techniques such as bilinear, bicubic, and nearest neighbor interpolation [

23,

24], as well as reconstruction-based approaches that use mathematical models or image priors. Interpolation-based methods are simple and computationally efficient, but often result in image blurring and loss of detail. Reconstruction-based approaches can provide better results in preserving edge and texture information, but their performance depends heavily on the accuracy of the previously used information and is computationally intensive [

25,

26]. While these classical approaches laid the foundation for SISR, they face significant limitations in balancing efficiency and image quality, especially when it comes to complex textures and high-frequency details in remote sensing images.

2.2. CNN-Based Models for SR

The application of deep learning to image SR began with Dong et al. [

10] who introduced the SRCNN model for end-to-end mapping of LR to HR images. Although SRCNN improved speed and quality, its pre-upsampling module increased computational complexity and slowed convergence. Kim et al. This was fixed with VDSR [

12], which fixed the gradient disappearing issue and improved the details. He et al. [

27] leveraged residual networks to enable deeper architectures without sacrificing performance. Building on these advances, Lim et al. proposed EDSR [

11], which refined SRResNet [

28] by removing batch normalization layers, reducing memory usage during training by 40% while improving image quality. Attention mechanisms further improved SR models, as Zhang et al. [

14] using Residual Channel Attention Network (RCAN) to improve feature learning. Remote sensing image super-resolution (RSISR) quality is crucial for tasks such as object detection [

29], instance segmentation [

30], classification [

31], etc. Liebel et al. [

32] adapted SRCNN to outperform traditional interpolation methods, while Lei et al. [

33] developed LGCNet to take into account the different scaling properties of RSIs and integrate cross-layer functions for improved reconstruction. Xu et al. [

34] has further developed this with the Deep Memory Convolutional Network (DMCN), using a symmetric hourglass structure and multiple residual connections to increase performance. Ma et al. [

35] introduced WTCRR, which combines wavelet transform with local and global residual connections to reduce artifacts and improve edge detail in RSIs.

2.3. Transformer-Based Models for SR

Transformers have inspired several adaptations for SR tasks. Chen et al. [

9] introduced IPT, a pre-trained Transformer that excels in several low-level vision tasks, including SR. Liang et al. [

8] followed with SwinIR, which uses the Swin Transformer [

36] for SR, noise reduction and artifact reduction. Fang et al. [

37] proposed HNCT, a hybrid CNN-Transformer that provides high reconstruction quality and efficiency. Li et al. [

21] introduced DLGSANet, leveraging dynamic local and global self-attention for state-of-the-art accuracy with fewer parameters. In RSISR, Lei et al. [

38] introduced TransENet and integrated high and low dimensional features, while He et al. [

39] proposed DsTer, a dense spectral Transformer for 3D data processing. Tu et al. [

40] developed SWCGAN, a generative adversarial network combining CNNs with the Swin Transformer, and Tang et al. [

41] introduced HSTNet, capturing detailed contours using recursive information.

2.4. Lightweight Models for SR

To balance performance and computational efficiency, various lightweight SR models have been developed. Liu et al. [

42] introduced RFDN, which uses a residual feature distillation mechanism to optimize feature extraction. Ahn et al. [

43] proposed CARN, which uses a cascaded residual network structure for efficient SR. Lu et al. [

44] introduced ESRT, which improves function representation and manages long-range dependencies with reduced computational costs. Zhang et al. [

45] introduced ELAN, which combines shifted convolutions and multi-scale self-attention to efficiently extract local and global features, accelerated by attention mechanisms. Zhang et al. [

46] introduced SPIN, a lightweight image SR model that improves feature extraction through superpixel token interaction while effectively reducing computational complexity. In the context of RSISR, lightweight models are essential for use in resource-constrained environments such as embedded devices. Wang et al. [

47] proposed AMFFN, an attention-based multilayer feature fusion network that uses dynamic feature distillation modules and partial morphological residual blocks to efficiently extract key features, outperforming previous methods [

10,

48]. Wang et al. [

49] also introduced CTN, which minimizes parameters by integrating multi-level context functions using context transition layers and contextual aggregation modules. Although these models achieve impressive efficiency, they do not specifically address the challenge of reconstructing strip-like features in RSIs. In contrast, our proposed model leverages the flexible deformation capabilities of convolutions and the long-range learning capability of Transformers coupled with superpixels to effectively reconstruct narrow, strip-like features, thereby striking a balance between parameter efficiency and performance.

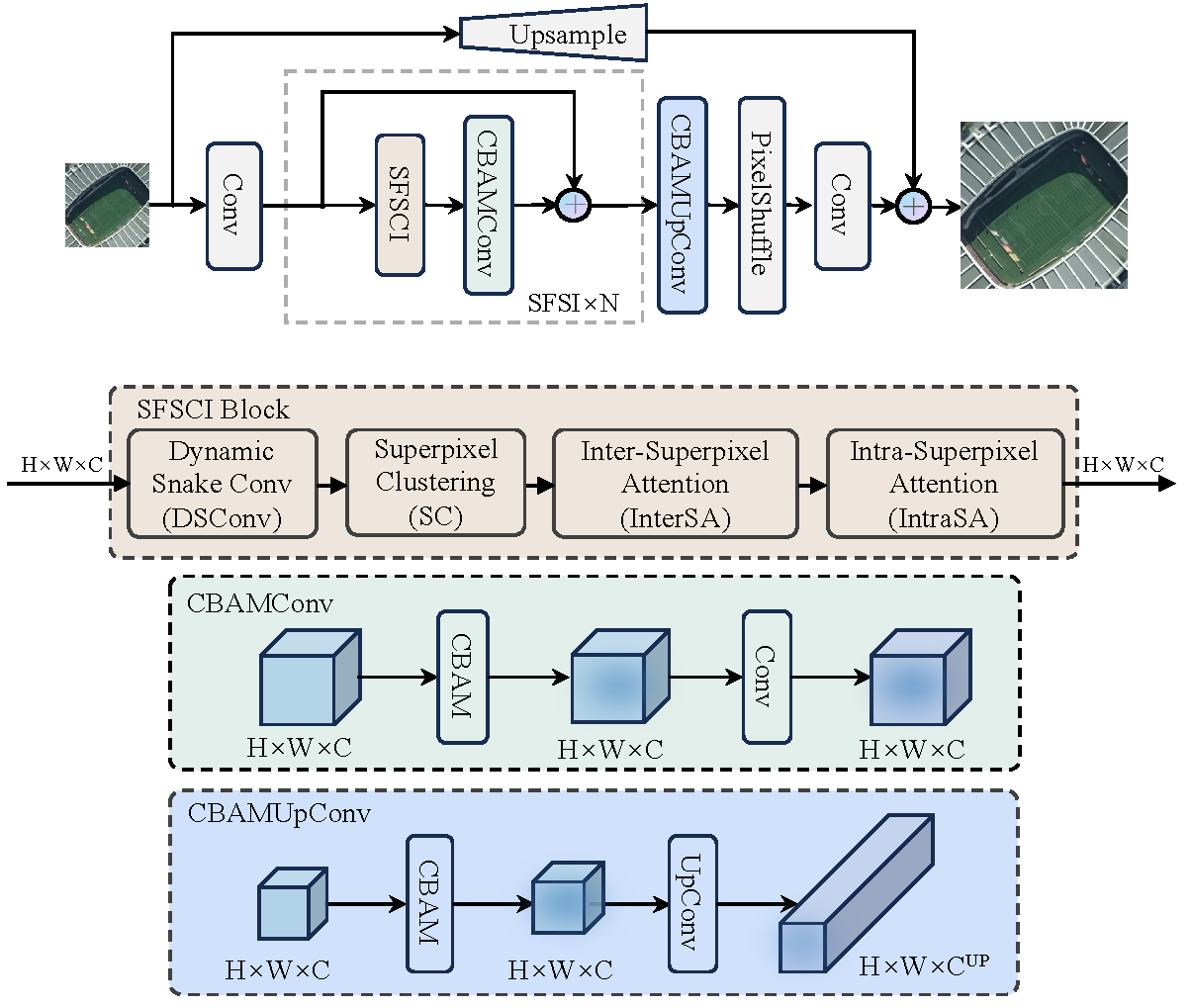

3. Methodology

The architecture of the proposed strip-like feature superpixel interaction network (SFSIN) consists of three key phases: morphological feature extraction, deep feature extraction using strip-like feature superpixel interaction (SFSI) blocks, and image reconstruction through the CBAMUpConv module, as shown in

Figure 2. Each of these components has been carefully designed to address specific challenges in RSISR, particularly in capturing strip-like features that are prevalent in RSIs.

In the following subsections, we will go into detail about the design and functionality of each module and how they contribute to the overall performance of the network.

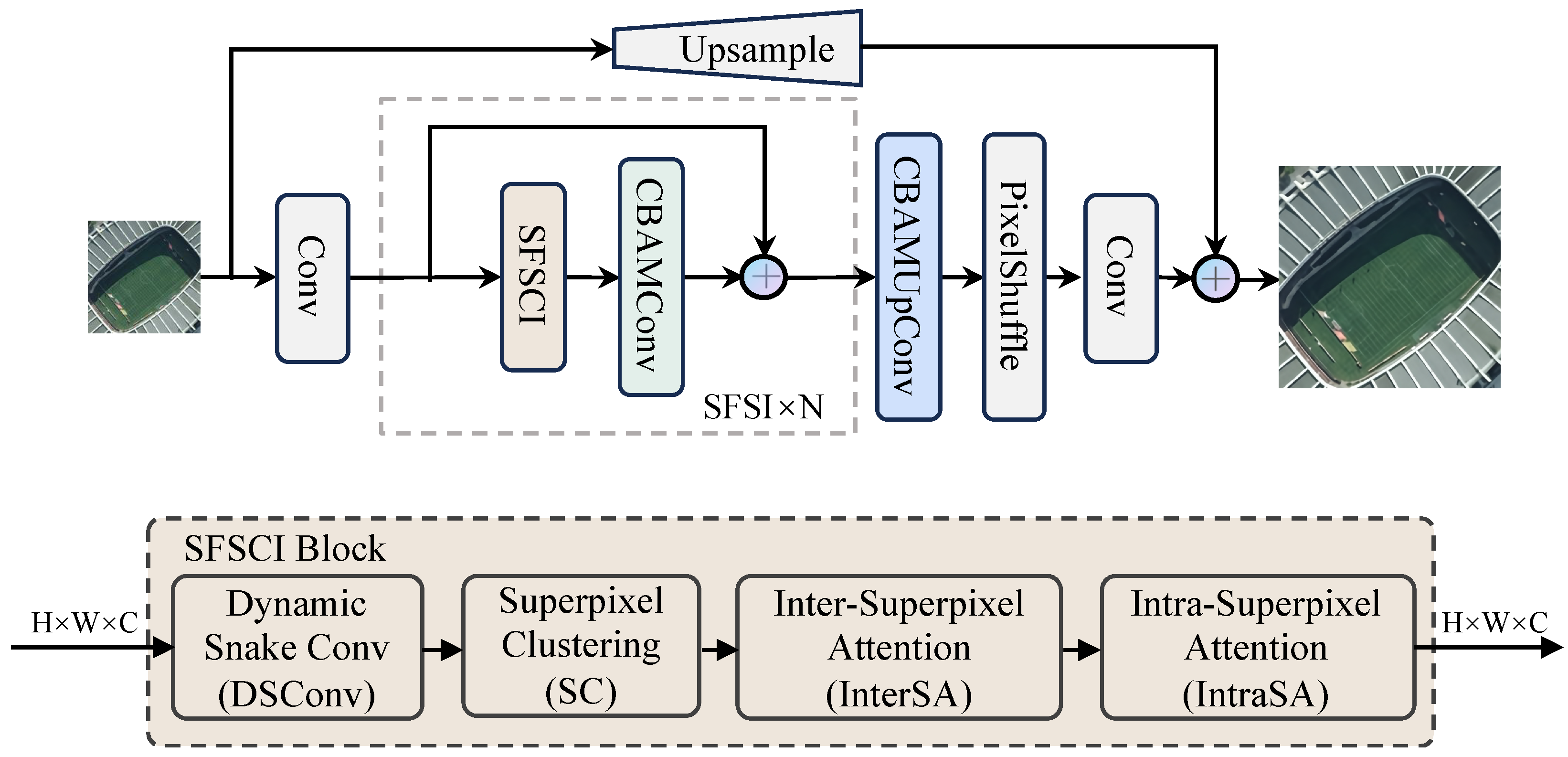

3.1. Architecture

As shown in

Figure 2, SFSIN consists of three main phases: morphological feature extraction, deep feature extraction, and image reconstruction.

Given an LR RSI , the first phase applies a standard convolutional layer to extract morphological features, resulting in , where H and W represent the height and width of the image, and C denotes the number of feature channels. Morphological feature extraction is crucial for capturing basic structural information, which serves as the basis for subsequent deep feature learning.

Next, in the deep feature extraction phase, N blocks of SFSI are stacked to gradually capture deeper representations, which can be expressed as , from the morphological features . Each SFSI block consists of the strip-like feature superpixel cross and intra interaction block (SFSCI), which includes dynamic snake convolution (DSConv), superpixel clustering (SC), inter-superpixel attention (InterSA), and intra-superpixel attention (IntraSA). These components are designed to effectively capture strip-like features and aggregate features from both local and global perspectives.

In addition, residual connections are used in each SFSI block to ensure stable training and better gradient propagation, allowing the model to learn deeper features without suffering from vanishing gradients.

This process can be expressed as follows:

where

denotes the features of the

SFSI block,

denotes the output functions of the

SFSCI,

and

represent the SFSCI and CBAMConv operations, respectively.

The deep features extracted from the final SFSI block are then passed to the image reconstruction module, which utilizes the CBAMUpConv module. The CBAMUpConv module integrates spatial and channel attention mechanisms to further refine feature maps before upsampling them through the PixelShuffle operation. This module ensures that important spatial patterns and channel-related information are highlighted, allowing the model to produce high-resolution images with minimal loss of detail. The final convolution layer aggregates the upsampled features into a high-resolution RSI .

This process is summarized by the following equation:

where

represents the CBAMUpConv module that applies attention mechanisms,

denotes the PixelShuffle operation, and

is the final convolutional layer that produces the high-resolution image.

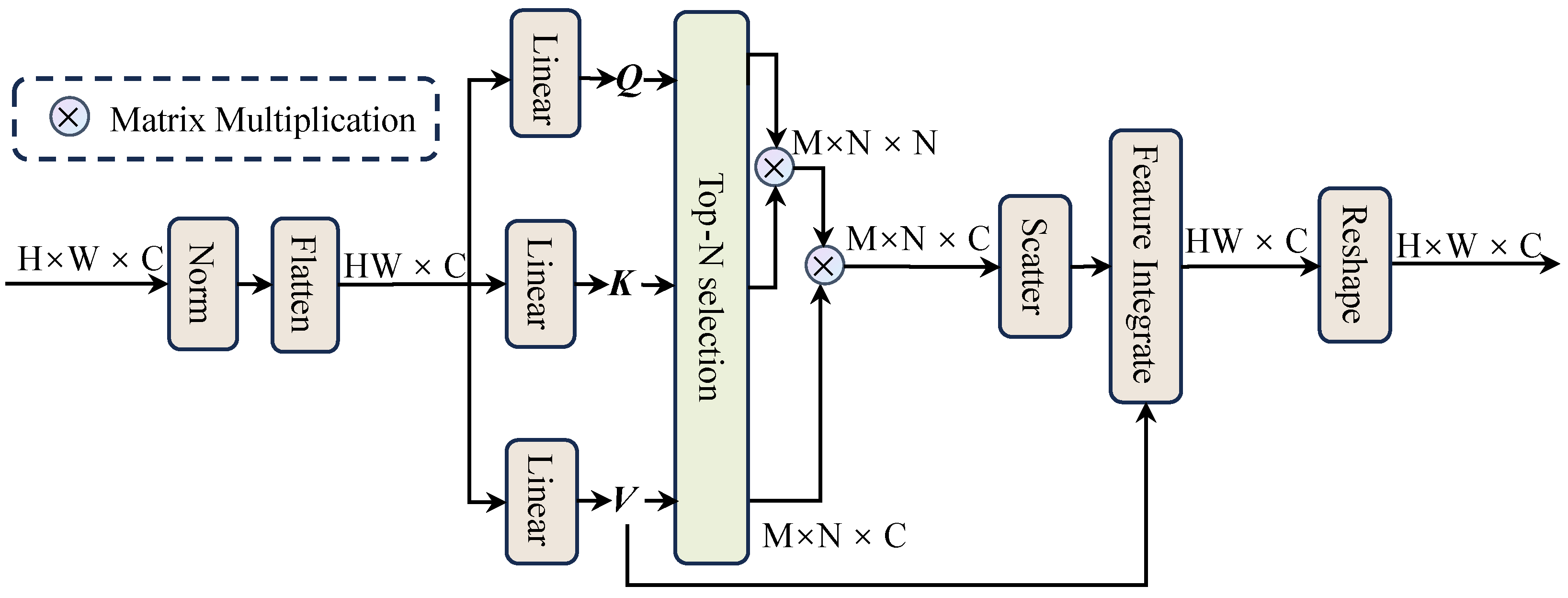

3.2. Strip-like Feature Superpixel Cross and Intra Interaction Module

The core component of SFSIN is the strip-like feature superpixel cross and intra interaction (SFSCI), which is responsible for extracting and refining strip-like features in RSIs. As shown in

Figure 2, the SFSCI module consists of four key components: dynamic snake convolution (DSConv), superpixel clustering (SC), inter-superpixel attention (InterSA) and intra-superpixel attention (IntraSA).

Each of these components plays a unique role in addressing the challenges presented by the unique geometries and feature patterns in RSIs. The DSConv module is specifically designed for effective strip-like feature extraction from RSIs. The SC module groups similar pixels into superpixels, which helps reduce computational complexity while maintaining the integrity of important boundaries within the image. The InterSA module captures long-range dependencies by using superpixels as mediators, while the IntraSA module focuses on refining details within each superpixel. These two attention mechanisms are integrated to improve feature representation at both global and local levels and enable more accurate reconstruction of the model.

In summary, this module extracts strip-like features from RSIs, generates superpixels, and then aggregates features from both global and local perspectives of the superpixels. Below we present these components to you in detail.

3.2.1. Dynamic Snake Convolution

RSIs often contain strip-like structures that are difficult to detect for standard convolution operations due to their fixed receptive fields. Dynamic snake convolution (DSConv) is introduced to adjust the receptive fields for convolution along these curvilinear structures, thereby providing a more flexible and effective method for detecting such features.

Specifically, given a standard 9 × 9 2D convolution kernel K with the center coordinate at , by introducing offsets , the convolution kernel extends along the and , allowing it to follow the curvature of strip-like features. For the , the position of each grid in K is given by , where represents the horizontal distance from the center grid. The choice of each grid position in the convolution kernel K is an accumulation process. Starting from the center position , the position of a grid further from the center depends on the position of the previous grid , where the offset is accumulates to ensure continuity along the strip-like features. The flexibility provided by DSConv ensures that important structural details are captured, which is critical to improving the accuracy of RSISR. This method not only increases the model’s ability to capture these complex shapes but also alleviates the limitations of deformable convolutions, which, while more flexible than standard convolutions, still have problems with highly curvilinear features.

The process can be expressed as follows:

Likewise, the process for the

is given by:

3.2.2. Superpixel Clustering

To efficiently handle the complexity of RSIs, superpixel clustering (SC) is used to group similar pixels into superpixels. This method significantly reduces computational complexity while preserving the integrity of important boundaries within the image.

The SC method used in SFSIN is based on the soft superpixel segmentation (SSN) approach [

20], which avoids the fixed patch sizes usually used in standard approaches. This aggregation helps maintain structural coherence, particularly for strip-like features, while reducing boundary artifacts. Furthermore, by leveraging superpixels, InterSA and IntraSA (introduced in the following sections) reduce the computational complexity typically associated with traditional self-attention mechanisms while effectively capturing global and local relationships within the image.

Specifically, the feature map is first divided into a regular grid and superpixels are initialized into , where M denotes the number of superpixels. Given a pixel (note that is the number of pixels), it belongs to one of the M superpixels. The relationship between pixels and superpixels is then iteratively refined through soft associations.

For the

iteration, the process of updating superpixel centers is given as follows:

where

denotes the soft association between pixel

p and superpixel

i during the

iteration.

represents the distance between the pixel and the superpixel center.

denotes the

pixel of the original image, and

denotes the center of the

superpixel during the

iteration.

It is important to note that by reducing the number of elements the model must process and focusing on meaningful groups of pixels, SC enables more efficient feature extraction and reduces noise in the final reconstructed image. This is particularly useful in remote sensing, where image complexity is high, and boundary preservation is critical.

We then update the superpixel centers using the following formula:

where the notation

denotes the center of the

superpixel during the

iteration. While

represents the normalization constant along the columns. After

T iterations, we get the final relationship matrix

.

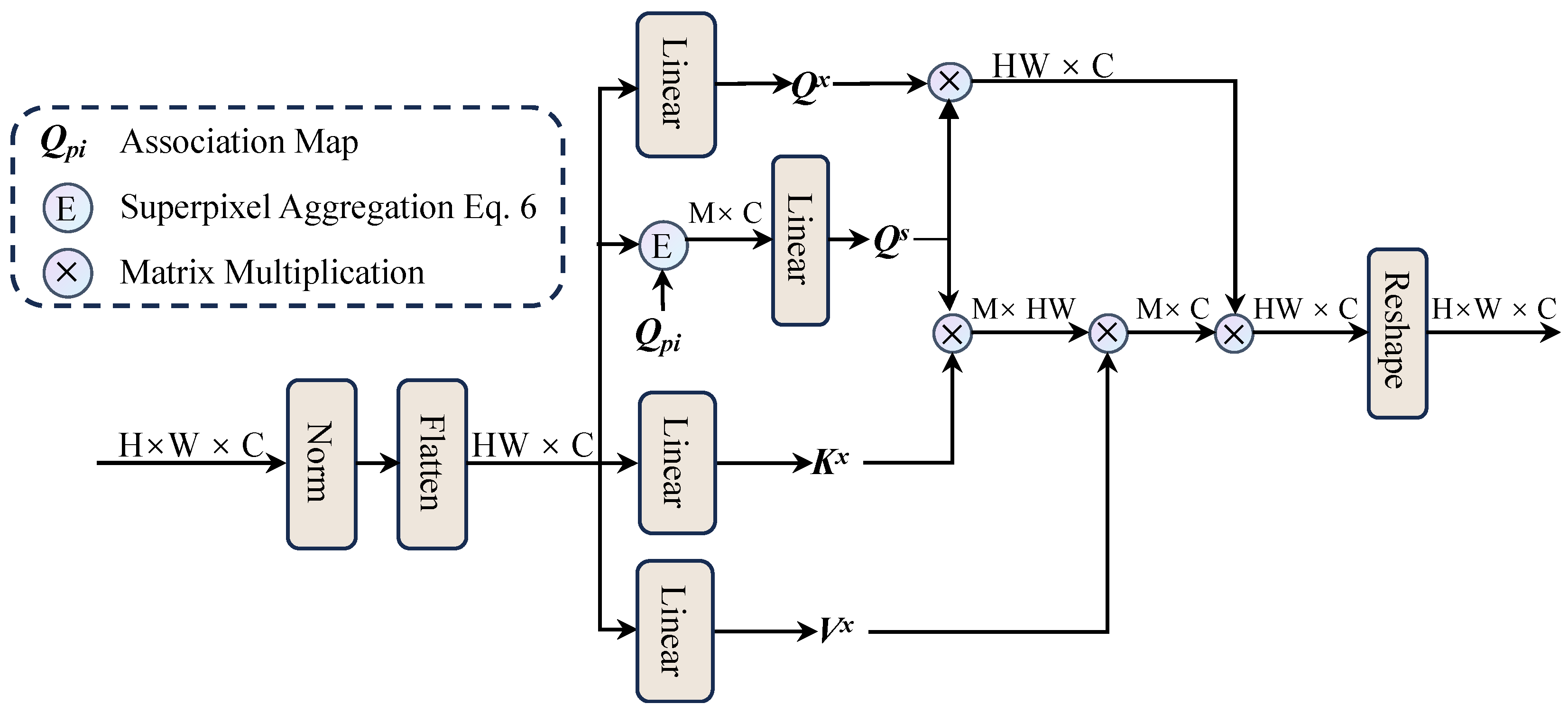

3.2.3. Inter-Superpixel Attention

RSIs often require capturing relationships between distant regions because linear and strip-like features can span large areas. Inter-superpixel attention (InterSA) addresses this problem by treating superpixels as proxies for individual pixels, allowing the model to more effectively capture feature interaction over long distances.

InterSA uses a self-attention mechanism to calculate relationships between superpixels, which is crucial for capturing long-term dependencies in RSIs. These dependencies provide valuable context for accurately reconstructing strip-like features.

This cross-attention mechanism allows the model to understand the connections between different parts of the image, especially for objects that are spatially distant but semantically connected. InterSA thereby improves the accuracy of feature reconstruction for these spatially extended structures.

As shown in

Figure 3, given flattened pixels

and superpixels

, where

M is the number of superpixels.

First, we use linear mappings to calculate the query:

, key:

, and value:

as follows:

where

represents superpixels and

represents ordinary pixels,

,

,

are the weight matrices for query, key and value.

We then calculate the updated superpixel features as follows:

where

is a scaling factor introduced to prevent the gradient from disappearing. We then pass the aggregated pixels to the individual pixels, specifically using

to get the pixel queries,

as the key, and

as the value. Finally, the updated superpixel features are mapped back to pixel-level features. Through this process, our model learns the global characteristics of RSIs.

3.2.4. Intra-Superpixel Attention

Intra-superpixel attention (IntraSA) focuses on refining local details within each superpixel. While InterSA captures long-range dependencies, IntraSA ensures that the model also accurately captures fine-grained information within each superpixel.

An intuitive approach to improving resolution in SR tasks is to exploit the complementarity of similar pixels within superpixels. However, this presents challenges such as a different number of pixels within each superpixel, which can increase computational complexity and memory consumption.

To mitigate this, as shown in

Figure 4, IntraSA uses a top-N selection mechanism that selects the most relevant pixels within each superpixel for self-attention. This reduces the computational effort while ensuring that important local features are not missed.

It then calculates the relationships between these selected pixels within the superpixel using the self-attention mechanism defined by equations (

7) and (

8). The calculated pixels are then distributed again to their respective positions in the image. While top-N selection alleviates the problems mentioned above, it also means that some similar pixels within a superpixel may not be considered. Therefore, we use the value key to capture all features before the pixel attention operation and integrate them back into the original image with distributed pixels.

3.3. Convolutional Block Attention Module with Upsampling Convolution

In the image reconstruction phase, standard upsampling convolutions and PixelShuffle methods often miss important spatial and channel information, resulting in suboptimal image quality. To address this limitation, we propose a novel CBAMUpConv module, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to integrate both spatial and channel attention mechanisms into the upsampling process, as presented in

Figure 5. This innovative design improves feature refinement during the reconstruction phase by explicitly focusing on the most informative spatial regions and feature channels.

Our CBAMUpConv module applies attention mechanisms directly to the deep features , which were extracted from the SFSI blocks. By leveraging spatial attention, the model is able to prioritize the most important areas within the image, while channel attention ensures that the most relevant feature channels are highlighted, enabling more accurate and detailed reconstructions.

In a further step, the CBAMUpConv module expands the number of feature channels to , where , and upscale corresponds to the model parameter, which can take values of 2, 3 or 4.

This design represents a novel contribution to the field as, to our knowledge, it is the first time that channel and spatial attention mechanisms have been explicitly combined in an upsampling convolution module specifically tailored to image reconstruction tasks.

In summary, the CBAMUpConv module introduces a novel approach to upsampling by integrating attention mechanisms into the upsampling convolution process. This combination of spatial attention and channel attention ensures that important features are preserved while reducing computational effort. The module improves the model’s ability to produce high-quality, high-resolution reconstructions, especially in resource-limited environments.

4. Experiments

In this section, we present a comprehensive evaluation of our proposed SFSIN model, focusing on the contribution of each module through ablation studies. Furthermore, we evaluate the performance of the model at different scales in the RSISR tasks to demonstrate its robustness and adaptability to different levels of degradation.

4.1. Experimental Settings

4.1.1. Dataset and Evaluation

We use the AID dataset [

50], a benchmark in RSI, which consists of 10,000 images from 30 different scene categories such as urban areas, forests and water bodies. Each image is originally 600 × 600 pixels in size, providing a high-resolution foundation for SR tasks. The dataset is split into 80% training, 10% validation, and 10% testing subsets to ensure balanced performance evaluation.

To simulate real-world scenarios where image resolution varies significantly, we downsample the original high-resolution images by bicubic interpolation with scaling factors ×2, ×3, and ×4. These different levels of degradation allow us to test the adaptability of our method to different reconstruction challenges. For quantitative evaluation, we use PSNR and SSIM [

51], which are widely accepted for measuring the perceptual and structural quality of the reconstructed images. These metrics are calculated on the Y channel of the YCbCr color space because this contains most of the luminance information that is critical to visual fidelity.

4.1.2. Implementation Details

We design two variants of SFSIN with different complexity, called SFSIN-S and SFSIN. The SFSIN model includes 8 SFSCI residual groups, each containing a DSConv module, and considers CBAM attention before the pixel shuffle operation. For SFSIN-S, DSConv modules are used only in the first four residual groups, which reduces the number of parameters while maintaining performance. All other settings remain consistent with SFSIN.

4.1.3. Training Settings

We train both models with 64 × 64 patches, a size chosen to ensure a balance between computational efficiency and the ability to capture important patterns in RSIs. Each model is trained with a batch size of 40. The initial learning rate is set to , and a gradual learning rate decay is applied in epochs [250, 400, 450, 475, 500]. We believe that it effectively stabilizes training and prevents overadaptation. After 600 epochs the training is complete.

To further improve the generalization and robustness of the model, we apply data augmentation techniques including random rotations of 90, 180and 270as well as horizontal reflections. These extensions simulate various angles and transformations that RSIs may encounter in real-world scenarios. The models are implemented in PyTorch and trained on a system equipped with two Intel Xeon Gold 6133 CPUs, an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU and 1007.5 GB memory running Ubuntu 20.04 LTS.

4.2. Comparison with Other Lightweight Methods

Finally, we compare our proposed models SFSIN-S and SFSIN with ten state-of-the-art lightweight models, including CNN-based methods such as AWSRN-M [

52], RFDN [

42], LatticeNet [

53] and MAFFSRN-L [

54] as well as Transformer-based approaches such as ESRT [

44], SPIN [

46] and ELAN-light [

45]. In addition, we evaluate remote sensing-specific algorithms such as LGCNet [

33], CTNet [

49] and AMFFN [

47].

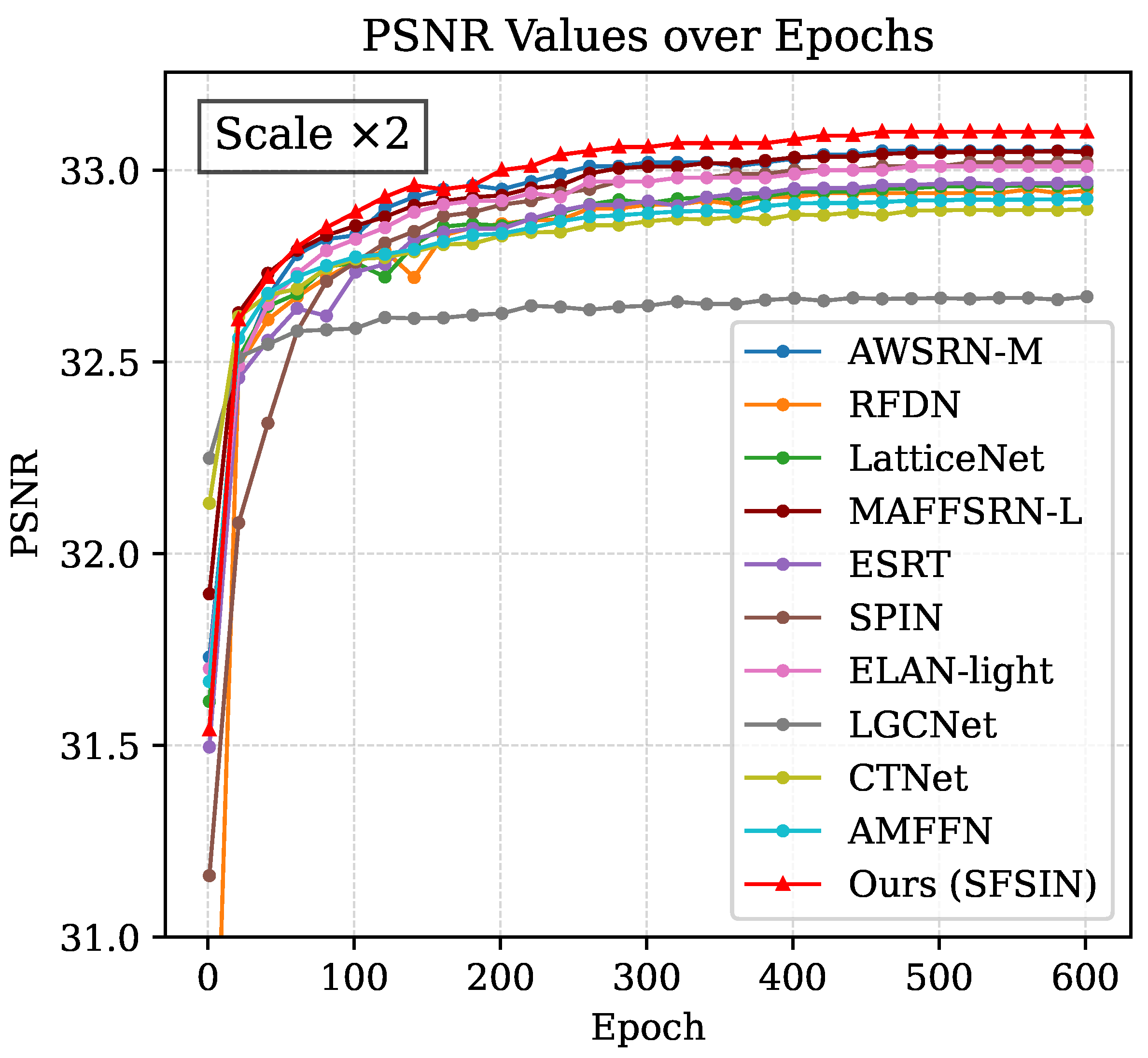

To visually compare the performance of these models, we present the PSNR training curves in

Figure 6. This figure illustrates how quickly and effectively each ×2 scale model converges to the AID dataset and the final reconstruction quality achieved after 600 epochs.

This analysis highlights the strength of our proposed attention mechanisms and DSConv modules in enabling more accurate and efficient RSISR. SFSIN’s ability to consistently achieve the best PSNR across almost all epochs highlights its robustness in dealing with complex textures and strip-like features in RSIs. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that while other models exhibit significant fluctuations and instability in their PSNR curves, our model maintains remarkably stable performance, further demonstrating its reliability and consistency.

4.2.1. Quantitative Evaluation

As shown in

Table 1, our proposed SFSIN model consistently outperforms other methods at all scales, demonstrating its superiority in handling RSISR. On the

scale, SFSIN achieves a PSNR of 33.10 dB and an SSIM of 0.8715, significantly outperforming the best-performing baseline methods. In particular, SFSIN shows a PSNR gain of 0.43 dB over LGCNet and a 0.2 dB improvement over CTNet, highlighting its ability to accurately reconstruct detailed structures in RSIs.

This improvement is due to SFSIN’s ability to retain strip-like features in RSIs, a task that LatticeNet and CTNet struggle with. By using DSConv, our model can adaptively focus on these structures, while CBAM improves the feature extraction process by selectively prioritizing informative regions. The synergy between these components leads to more accurate reconstructions, especially for complex textures.

The smaller variant SFSIN-S also delivers competitive results, especially in resource-constrained scenarios where model complexity is a key factor. SFSIN-S achieves second-best performance in most cases, providing a balance between computational efficiency and reconstruction quality. For example, SFSIN-S achieves a PSNR of 30.23 dB on the scale, outperforming several state-of-the-art models and exhibiting only a small performance penalty compared to the full SFSIN model.

It is worth noting that on the scale, SFSIN-S slightly outperforms SFSIN in terms of PSNR, which is likely due to its better generalization and efficiency in handling larger upsampling factors.

The quantitative comparison highlights the effectiveness of our proposed method, especially in extracting strip-like features such as linear elements, which are crucial for remote sensing tasks. These results confirm the strength of our DSConv and attention mechanisms in addressing the unique challenges of RSISR.

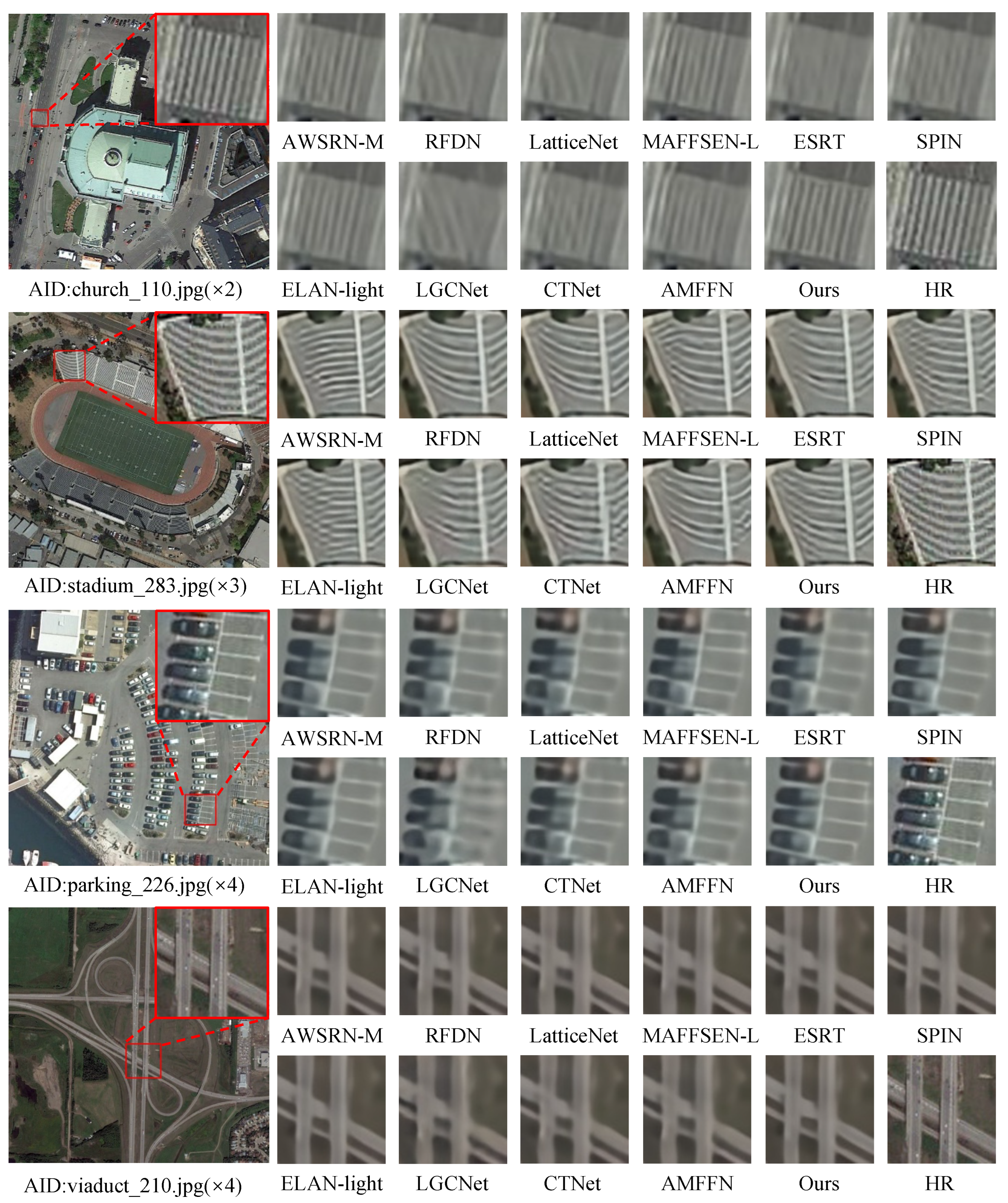

4.2.2. Visual Quality Analysis

In addition to quantitative improvements, our SFSIN model excels in the quality of visual reconstruction, especially in demanding remote sensing scenarios. In

Figure 7, SFSIN demonstrates its ability to preserve thin structures that are often blurred or distorted by methods such as RFDN and LatticeNet. For clarity, the red box highlights correspond to the HR images.

For example, when reconstructing the RSI "church_110" at the ×2 scale, several lightweight methods struggle to accurately recover strip-like features, resulting in visible blurring and loss of structural integrity. In contrast, our SFSIN model effectively preserves these critical features and produces a result that is much closer to the high-resolution ground truth. Similarly, in images such as "stadium_283", "parking_226", and "viaduct_210", SFSIN accurately preserves the complex linear features of parking lots, stadium markers, and viaducts, while other methods cannot maintain this level of detail, resulting in smoothed or corrupted regions.

In summary, SFSIN’s ability to adaptively capture and highlight strip-like structures directly addresses the unique requirements of RSISR and further validates its effectiveness across different image types and scales.

4.3. Ablation Studies

To thoroughly evaluate the contribution of the DSConv and CBAM modules in our proposed SFSIN model, we performed ablation experiments on the AID dataset over the scaling factors ×2, ×3, and ×4. All models were trained under identical settings to ensure a fair comparison. The results presented in

Table 2 illustrate the incremental improvements each module brings and reveal important insights into the effectiveness of these components in addressing the challenges of RSISR.

4.3.1. Impact of DSConv

The DSConv module is introduced as a fundamental component in SFSIN and is used to capture the strip-like features prevalent in RSIs. By leveraging its efficiency in integrating both local and global spatial information, DSConv plays a crucial role in improving feature extraction

As can be seen in

Table 2, the inclusion of DSConv consistently improves PSNR and SSIM across all scales. For example, the model with DSConv at ×2 scale shows significant improvement in both PSNR (from 33.02 to 33.06) and SSIM (from 0.8693 to 0.8704). These results confirm that DSConv is particularly effective in preserving and reconstructing strip-like structures and other linear features that are crucial in RSIs. The improved performance across all scales highlights DSConv’s robustness in dealing with various levels of degradation, making it an essential part of the SFSIN architecture.

To achieve a balance between model performance and complexity, we further investigated the optimal number of DSConv modules in the SFSI residual groups. We gradually increased the number of DSConv modules from 1 to 8 and evaluated their impact on performance. As shown in

Table 2, both PSNR and SSIM improve as the number of DSConv modules increases and reach their peak when 6 modules are used. At this point, the model achieves the highest PSNR and near optimal SSIM, suggesting that 6 DSConv modules provide the best compromise between capturing fine-grained details and controlling model complexity. In particular, when only 4 DSConv modules are used, the model still achieves a competitive PSNR while minimizing the number of parameters, making it a viable option for resource-constrained environments. This configuration forms the basis of our SFSIN-S variant, which maintains strong performance with fewer parameters and demonstrates the flexibility of our approach in adapting to different computing requirements.

4.3.2. Impact of CBAMConv and CBAMUpConv

Next, we evaluate the effectiveness of the attention mechanisms CBAMConv and CBAMUpConv, which we innovatively integrate into the reconstruction phase of our model. CBAMConv is integrated with the SFSI module to improve feature extraction by capturing both local and global features, while CBAMUpConv is integrated with the reconstruction module to facilitate PixelShuffle during the upsampling process as described in

Section 3.3 .

The results in

Table 2 clearly show the significant impact of the CBAM module. For example, using the DSConv module alone on the ×2 scale results in a PSNR of 33.06 and an SSIM of 0.8704. However, when combined with the CBAMConv module, the PSNR increases to 33.08 and the SSIM improves to 0.8708. This performance increase highlights that with the introduction of the DSConv and CBAMConv modules in the feature extraction process, SFSIN selectively improves key spatial and channel features and strengthens the strip-like features that the DSConv module extracts.

More importantly, the results show even more significant improvements when integrating the DSConv, CBAMConv and CBAMUpConv modules, demonstrating the synergy between attention in feature extraction and reconstruction, as the PSNR increases to 33.10 and SSIM improves to 0.8715. This shows that attention applied to both deep feature extraction and reconstruction ensures better feature preservation and more accurate SR results.

5. Conclusion and Future Work

In this paper, we introduced the strip-like feature superpixel interaction network (SFSIN), a lightweight hybrid network that leverages the SFSCI modules with dynamic snake convolutions to effectively capture strip-like features. Superpixel clustering further improves the representation of local and global structures. The integration of the CBAMConv and CBAMUpConv modules improves the model’s ability to learn rich features, resulting in superior performance at various scaling factors, especially in preserving details and reducing blur.

For future work, we plan to extend SFSIN for multispectral and hyperspectral images, thereby expanding its applicability in the real world. Finally, optimizing the model for real-time use in resource-constrained environments, such as on-board satellite systems, will be a key focus.

Funding

This research work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 72371067, Hebei National Science Foundation under Grant No. F2021501020, the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities under Grant No. N2323020, and the Funded by Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department under Grant No. QN2024167.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Turner, W.; Spector, S.; Gardiner, N.; Fladeland, M.; Sterling, E.; Steininger, M. Remote sensing for biodiversity science and conservation. Trends in ecology & evolution 2003, 18, 306–314. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, M.; Liu, X.; Clarke, K.C. Spatial metrics and image texture for mapping urban land use. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing 2003, 69, 991–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Thenkabail, P.S.; Lyon, J.G.; Huete, A. Advances in hyperspectral remote sensing of vegetation and agricultural crops. In Fundamentals, Sensor Systems, Spectral Libraries, and Data Mining for Vegetation; CRC press, 2018; pp. 3–37.

- Joyce, K.E.; Belliss, S.E.; Samsonov, S.V.; McNeill, S.J.; Glassey, P.J. A review of the status of satellite remote sensing and image processing techniques for mapping natural hazards and disasters. Progress in physical geography 2009, 33, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zhang, L.; Huang, B.; Li, P. A MAP approach for joint motion estimation, segmentation, and super resolution. IEEE Transactions on Image processing 2007, 16, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhler, T.; Huang, X.; Schebesch, F.; Aichert, A.; Maier, A.; Hornegger, J. Robust multiframe super-resolution employing iteratively re-weighted minimization. IEEE Transactions on Computational Imaging 2016, 2, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. Swinir: Image restoration using swin transformer. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 1833–1844.

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, T.; Xu, C.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ma, S.; Xu, C.; Xu, C.; Gao, W. Pre-trained image processing transformer. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 12299–12310.

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Image super-resolution using deep convolutional networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2015, 38, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; Nah, S.; Mu Lee, K. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2017, pp. 136–144.

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, K.M. Accurate image super-resolution using very deep convolutional networks. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 1646–1654.

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Kong, Y.; Zhong, B.; Fu, Y. Residual dense network for image super-resolution. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 2472–2481.

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, K.; Wang, L.; Zhong, B.; Fu, Y. Image super-resolution using very deep residual channel attention networks. Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 286–301.

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; Tang, X. Accelerating the super-resolution convolutional neural network. Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11-14, 2016, Proceedings, Part II 14. Springer, 2016, pp. 391–407.

- Liu, Z.; Sun, M.; Zhou, T.; Huang, G.; Darrell, T. Rethinking the value of network pruning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.05270 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F. Multi-scale context aggregation by dilated convolutions. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.07122 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.; Qi, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y. Deformable convolutional networks. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 764–773.

- Qi, Y.; He, Y.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, G. Dynamic snake convolution based on topological geometric constraints for tubular structure segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 6070–6079.

- Jampani, V.; Sun, D.; Liu, M.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Kautz, J. Superpixel sampling networks. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 352–368.

- Li, X.; Dong, J.; Tang, J.; Pan, J. Dlgsanet: lightweight dynamic local and global self-attention networks for image super-resolution. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 12792–12801.

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 3–19.

- Zhang, L.; Wu, X. An edge-guided image interpolation algorithm via directional filtering and data fusion. IEEE transactions on Image Processing 2006, 15, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.W.; Siu, W.C. Robust soft-decision interpolation using weighted least squares. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2011, 21, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Yuan, H.; Yuan, Y.; Yan, P.; Li, L.; Li, X. Local learning-based image super-resolution. 2011 IEEE 13th International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing. IEEE, 2011, pp. 1–5.

- Kim, K.I.; Kwon, Y. Single-image super-resolution using sparse regression and natural image prior. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2010, 32, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Ledig, C.; Theis, L.; Huszár, F.; Caballero, J.; Cunningham, A.; Acosta, A.; Aitken, A.; Tejani, A.; Totz, J.; Wang, Z. ; others. Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 4681–4690.

- Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Guo, H.; Zhang, R.; Xia, G.S. Tiny object detection in aerial images. 2020 25th international conference on pattern recognition (ICPR). IEEE, 2021, pp. 3791–3798.

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, C.; Fang, S.; Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Atkinson, P.M. UNetFormer: A UNet-like transformer for efficient semantic segmentation of remote sensing urban scene imagery. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 190, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Rsmamba: Remote sensing image classification with state space model. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebel, L.; Körner, M. Single-image super resolution for multispectral remote sensing data using convolutional neural networks. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2016, 41, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Shi, Z.; Zou, Z. Super-resolution for remote sensing images via local–global combined network. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2017, 14, 1243–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Guangluan, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Lin, D.; Yirong, W. High quality remote sensing image super-resolution using deep memory connected network. IGARSS 2018-2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. IEEE, 2018, pp. 8889–8892.

- Ma, W.; Pan, Z.; Guo, J.; Lei, B. Achieving super-resolution remote sensing images via the wavelet transform combined with the recursive res-net. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 3512–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 10012–10022.

- Fang, J.; Lin, H.; Chen, X.; Zeng, K. A hybrid network of cnn and transformer for lightweight image super-resolution. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 1103–1112.

- Lei, S.; Shi, Z.; Mo, W. Transformer-based multistage enhancement for remote sensing image super-resolution. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yuan, Q.; Li, J.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zou, Y. DsTer: A dense spectral transformer for remote sensing spectral super-resolution. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2022, 109, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Mei, G.; Ma, Z.; Piccialli, F. SWCGAN: Generative adversarial network combining swin transformer and CNN for remote sensing image super-resolution. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2022, 15, 5662–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Gao, M.; Li, Q.; Pan, J.; Zou, G.; Jeon, G. Hybrid-scale hierarchical transformer for remote sensing image super-resolution. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tang, J.; Wu, G. Residual feature distillation network for lightweight image super-resolution. Computer vision–ECCV 2020 workshops: Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, proceedings, part III 16. Springer, 2020, pp. 41–55.

- Ahn, N.; Kang, B.; Sohn, K.A. Fast, accurate, and lightweight super-resolution with cascading residual network. Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 252–268.

- Lu, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Huang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, T. Transformer for single image super-resolution. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 457–466.

- Zhang, X.; Zeng, H.; Guo, S.; Zhang, L. Efficient long-range attention network for image super-resolution. European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2022, pp. 649–667.

- Zhang, A.; Ren, W.; Liu, Y.; Cao, X. Lightweight image super-resolution with superpixel token interaction. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 12728–12737.

- Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Ming, Y.; Lv, H. Remote sensing imagery super resolution based on adaptive multi-scale feature fusion network. Sensors 2020, 20, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, T.; Lu, Y.; Di, H. Contextual transformation network for lightweight remote-sensing image super-resolution. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.S.; Hu, J.; Hu, F.; Shi, B.; Bai, X.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lu, X. AID: A benchmark data set for performance evaluation of aerial scene classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 55, 3965–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE transactions on image processing 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Shi, J. Lightweight image super-resolution with adaptive weighted learning network. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.02358 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Li, C.; Fu, Y. Latticenet: Towards lightweight image super-resolution with lattice block. Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, –28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XXII 16. Springer, 2020, pp. 272–289.

- Muqeet, A.; Hwang, J.; Yang, S.; Kang, J.; Kim, Y.; Bae, S.H. Multi-attention based ultra lightweight image super-resolution. Computer Vision–ECCV 2020 Workshops: Glasgow, UK, –28, 2020, Proceedings, Part III 16. Springer, 2020, pp. 103–118.

Short Biography of Authors

|

Yanxia Lyu received the Ph.D. degree in the School of Computer Science and Engineering, Northeastern University, Shenyang, China, in 2020. She is currently an associate professor with the School of Computer and Communication Engineering, Northeastern University at Qinhuangdao. Her research interests include pattern recognition, information retrieval, and artificial intelligence applications. |

|

Yuhang Liu is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Science degree in Computer Science and Technology in Northeastern University at Qinhuangdao, Qinhuangdao, China. His academic interests focus on computer vision and remote sensing super-resolution. |

|

Qianqian Zhao is currently pursuing the BS degree in Computer Science and Technology in Northeastern University at Qinhuangdao, Qinhuangdao, China. Her research interests include data science and computer vision. |

|

Ziwen Hao is currently pursuing the M.S. degree from the School of Computer Science and Engineering, Northeastern University at Qinhuangdao, Qinhuangdao, China. His current research interests include super resolution of remote sensing images and machine learning. |

|

Xin Song received her Ph.D. degree from Northeastern University in 2008. Now she is a professor in School of Computer and Communication Engineering, Northeastern University at Qinhuangdao. Her research interests include wireless communication and image processing. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).