Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Dynamic Cervical Structural Testing

2.3. Neck Vitals Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Objective Test Results

3.2. Comparisons and Linear Relationships

3.3. Analysis of Cervical Sagittal Upright Images

3.4. Frequency of Ligamentous Cervical Instability

3.5. High Prevalence of IJV Compression and Elevated ONSD

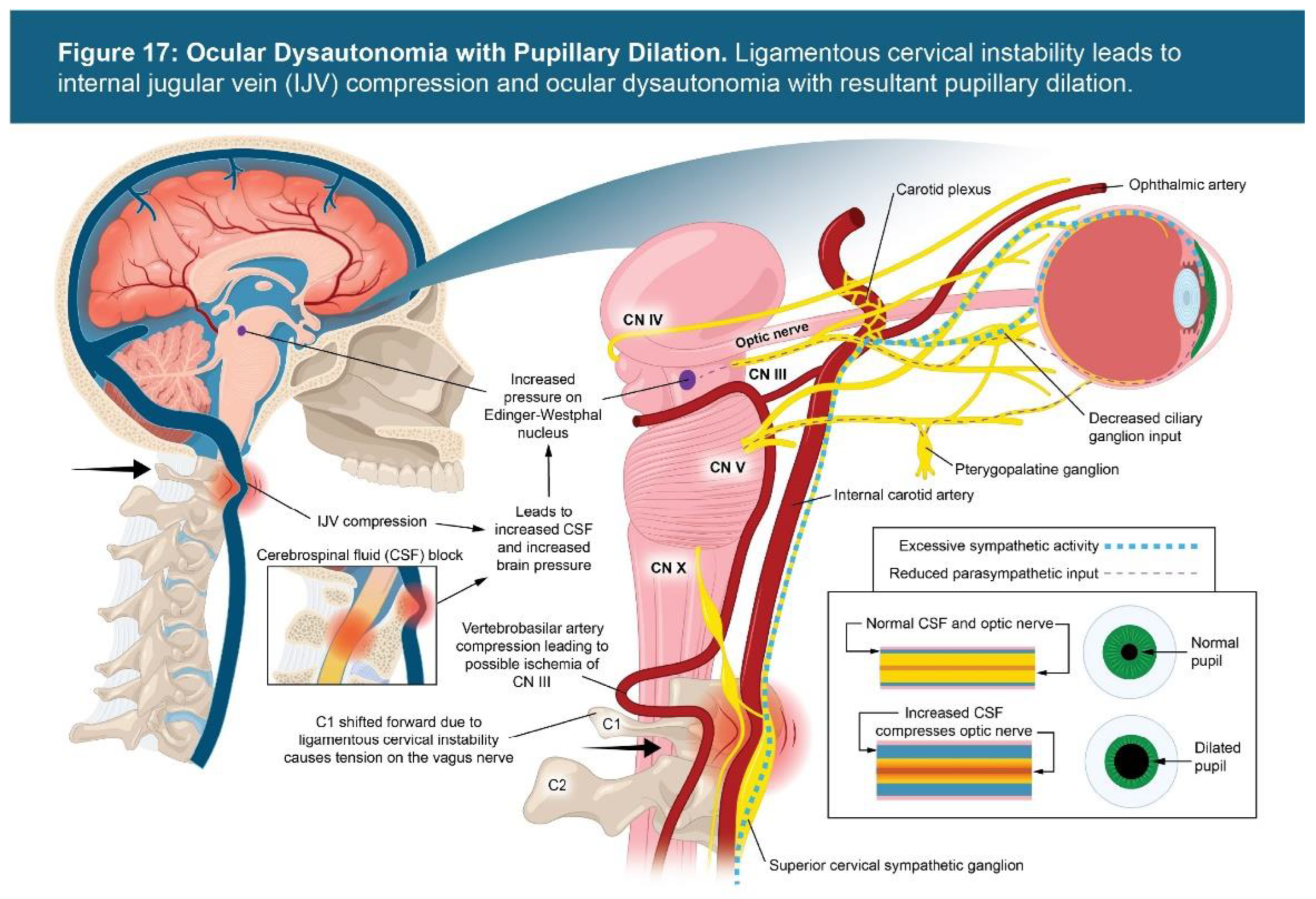

3.6. Vagus Nerve Degeneration and Ocular Dysautonomia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANS | Autonomic nervous system |

| C6AI | C6-atlas interval |

| CBCT | Cone beam computerized tomography |

| CSA | Cross-sectional area |

| CSF | Cerebral spinal fluid |

| CT | Computerized tomography |

| DOC | Depth of curve |

| IJV | Internal Jugular Vein |

| IOP | Intraocular Pressure |

| LCI | Ligamentous cervical instability |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| ONSD | Optic nerve sheath diameter |

References

- Pavel IA, Bogdanici CM, Donica VC, et al. Computer Vision Syndrome: An Ophthalmic Pathology of the Modern Era. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(2):412. Published 2023 Feb 20. [CrossRef]

- Uddin O, Light J, Henderson A. Headaches and Blurry Vision. J Neuroophthalmol. 2024 Dec 1;44(4):e526. [CrossRef]

- Hu CX, Zangalli C, Hsieh M, Gupta L, Williams AL, Richman J, Spaeth GL. What do patients with glaucoma see? Visual symptoms reported by patients with glaucoma. Am J Med Sci. 2014 Nov;348(5):403-9. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Muheremu A, Tian W. Atypical symptoms in patients with cervical spondylosis: Comparison of the treatment effect of different surgical approaches. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 May;97(20):e10731. [CrossRef]

- Leung KKY, Chu EC, Chin WL, Mok STK, Chin EWS. Cervicogenic visual dysfunction: an understanding of its pathomechanism. Med Pharm Rep. 2023 Jan;96(1):16-19. [CrossRef]

- Erdinest N, Berkow D. [COMPUTER VISION SYNDROME]. Harefuah. 2021 Jun;160(6):386-392. Hebrew.

- Adane F, Alamneh YM, Desta M. Computer vision syndrome and predictors among computer users in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Health. 2022 Mar 24;50(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Bogdănici CM, Săndulache DE, Nechita CA. Eyesight quality and Computer Vision Syndrome. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2017 Apr-Jun;61(2):112-116. [CrossRef]

- Teo C, Giffard P, Johnston V, Treleaven J. Computer vision symptoms in people with and without neck pain. Appl Ergon. 2019 Oct;80:50-56. [CrossRef]

- Sen A, Richardson S. A study of computer-related upper limb discomfort and computer vision syndrome. J Hum Ergol (Tokyo). 2007 Dec;36(2):45-50.

- Tsantili AR, Chrysikos D, Troupis T. Text Neck Syndrome: Disentangling a New Epidemic. Acta Med Acad. 2022 Aug;51(2):123-127. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Keller PR, Busija L, et al. Blue-light filtering spectacle lenses for visual performance, sleep, and macular health in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Aug 18;8(8):CD013244. [CrossRef]

- Abudawood GA, Ashi HM, Almarzouki NK. Computer Vision Syndrome among Undergraduate Medical Students in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Ophthalmol. 2020, Article 2789376. [CrossRef]

- Blehm C, Vishnu S, Khattak A, Mitra S, Yee RW. Computer vision syndrome: a review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005 May-Jun;50(3):253-62. [CrossRef]

- Anderst W. (2014). In vivo cervical spine kinematics arthrokinematics and disc loading in asymptomatic control subjects and anterior fusion patients. [Dissertation]. [Pittsburgh (PA)]: University of Pittsburgh. http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/22226/1/anderst_edt2014.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2023.

- Bonney RA, Corlett EN. Head posture and loading of the cervical spine. Appl Ergon. 2002 Sep;33(5):415-7. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Kang H, Shin G. Head flexion angle while using a smartphone. Ergonomics. 2015;58(2):220-6. [CrossRef]

- Hauser RA, Matias D, Rawlings B. The ligamentous cervical instability etiology of human disease from the forward head-facedown lifestyle: emphasis on obstruction of fluid flow into and out of the brain. Front Neurol. 2024 Nov 27;15:1430390. [CrossRef]

- Guan X, Fan G, Wu X, et al. Photographic measurement of head and cervical posture when viewing mobile phone: a pilot study. Eur Spine J. 2015 Dec;24(12):2892-8. [CrossRef]

- Gupta V, Khandelwal N, Mathuria SN, Singh P, Pathak A, Suri S. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of craniovertebral junction abnormalities. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:354–9. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez AP, Anderson A, Farhan SD, et al. The Utility of Flexion-Extension Radiographs in Degenerative Cervical Spondylolisthesis. Clin Spine Surg. 2022 Aug 1;35(7):319-322. [CrossRef]

- Gisolf J, van Lieshout JJ, van Heusden K, Pott F, Stok WJ, Karemaker JM. Human cerebral venous outflow pathway depends on posture and central venous pressure. J Physiol. 2004 Oct 1;560(Pt 1):317-27. [CrossRef]

- Tartière D, Seguin P, Juhel C, Laviolle B, Mallédant Y. Estimation of the diameter and cross-sectional area of the internal jugular veins in adult patients. Crit Care. 2009;13(6):R197. [CrossRef]

- Yoon HK, Lee HK, Jeon YT, Hwang JW, Lim SM, Park HP. Clinical significance of the cross-sectional area of the internal jugular vein. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013 Aug;27(4):685-9. [CrossRef]

- Buch K, Groller R, Nadgir RN, Fujita A, Qureshi MM, Sakai O. Variability in the Cross-Sectional Area and Narrowing of the Internal Jugular Vein in Patients Without Multiple Sclerosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016 May;206(5):1082-6. [CrossRef]

- Gharieb Ibrahim HM. Effect of Pharmacological Mydriasis on the Intraocular Pressure in Eyes with Filtering Blebs Compared to Normal Eyes: A Pilot Study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022 Feb 1;16:231-237. [CrossRef]

- Siam GA, de Barros DS, Gheith ME, et al. The amount of intraocular pressure rise during pharmacological pupillary dilatation is an indicator of the likelihood of future progression of glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007 Sep;91(9):1170-2. [CrossRef]

- Hauser RA. Hauser’s Laws on the Ligamentous Structural Causes of Chronic Disabling Symptoms of Human Diseases. On J Neur & Br Disord. 2024;7(1):642-689. [CrossRef]

- Teo AQA, Thomas AC, Hey HWD. Sagittal alignment of the cervical spine: do we know enough for successful surgery? J Spine Surg. 2020 Mar;6(1):124-135. [CrossRef]

- Patel PD, Arutyunyan G, Plusch K, Vaccaro A Jr, Vaccaro AR. A review of cervical spine alignment in the normal and degenerative spine. J Spine Surg. 2020 Mar;6(1):106-123. [CrossRef]

- Borden AGB, Rechtman AM, Gershon-Cohen J. The normal cervical lordosis. Radiology; 1960; 74:806-809. [CrossRef]

- Hou SB, Sun XZ, Liu FY, et al. Relationship of Change in Cervical Curvature after Laminectomy with Lateral Mass Screw Fixation to Spinal Cord Shift and Clinical Efficacy. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2022 Mar;83(2):129-134. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud NF, Hassan KA, Abdelmajeed SF, Moustafa IM, Silva AG. The Relationship Between Forward Head Posture and Neck Pain: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2019 Dec;12(4):562-577. [CrossRef]

- Oakley PA, Moustafa IM, Haas JW, Betz JW, Harrison DE. Two Methods of Forward Head Posture Assessment: Radiography vs. Posture and Their Clinical Comparison. J Clin Med. 2024 Apr 8;13(7):2149. [CrossRef]

- Poursadegh M, Azghani MR, Chakeri Z, Okhravi SM, Salahzadeh Z. Postures of the head, upper, and lower neck in forward head posture: Static and quasi-static analyses. Middle East J Rehabil Health Stud. 2024;10(4), e136377. [CrossRef]

- Shaghayegh fard B, Ahmadi A, Maroufi N, Sarrafzadeh J. Evaluation of forward head posture in sitting and standing positions. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(11):3577–3582. [CrossRef]

- Deniz Y, Pehlivan E, Cicek E. Biomechanical variances in the development of forward head posture. Phys Ther Korea. 2024;31(2), 104–113. [CrossRef]

- Chu ECP, Lo FS, Bhaumik A. Plausible impact of forward head posture on upper cervical spine stability. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020 May 31;9(5):2517-2520. [CrossRef]

- Freeman MD, Katz EA, Rosa SL, Gatterman BG, Strömmer EMF, Leith WM. Diagnostic Accuracy of Videofluoroscopy for Symptomatic Cervical Spine Injury Following Whiplash Trauma. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Mar 5;17(5):1693. [CrossRef]

- Daffner R.H. Imaging of Vertebral Trauma. 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2011. p. 163. [Google Scholar] Accessed April 1, 2025.

- Bogduk N. Functional anatomy of the spine. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;136:675-88. [CrossRef]

- Radcliff K, Kepler C, Reitman C, Harrop J, Vaccaro A. CT and MRI-based diagnosis of craniocervical dislocations: the role of the occipitoatlantal ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Jun;470(6):1602-13. [CrossRef]

- Dickman CA, Mamourian A, Sonntag VKH, Drayer BP. Magnetic resonance imaging of the transverse atlantal ligament for the evaluation of atlantoaxial instability. J Neurosurg. 1991;75(2), 221–227. [CrossRef]

- Liao S, Jung MK, Hörnig L, Grützner PA, Kreinest M. Injuries of the upper cervical spine-how can instability be identified? Int Orthop. 2020;44:1239–53. [CrossRef]

- Freeman MD, Rosa S, Harshfield D, et al. A case-control study of cerebellar tonsillar ectopia (Chiari) and head/neck trauma (whiplash). Brain Inj. (2010) 24:988–94. [CrossRef]

- Azar NR, Kallakuri S, Chen C, Lu Y, Cavanaugh JM. Strain and load thresholds for cervical muscle recruitment in response to quasi-static tensile stretch of the caprine C5-C6 facet joint capsule. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2009 Dec;19(6):e387-94. [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan AG, Khayatzadeh S, Havey RM, et al. Cervical sagittal balance: a biomechanical perspective can help clinical practice. Eur Spine J. 2018 Feb;27(Suppl 1):25-38. [CrossRef]

- Steilen D, Hauser R, Woldin B, Sawyer S. Chronic neck pain: making the connection between capsular ligament laxity and cervical instability. Open Orthop J. 2014;8:326–345. [CrossRef]

- Solomonow M. Sensory-motor control of ligaments and associated neuromuscular disorders. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2006 Dec;16(6):549-67. [CrossRef]

- Jeon JC, Choi WI, Lee JH, Lee SH. Anatomical Morphology Analysis of Internal Jugular Veins and Factors Affecting Internal Jugular Vein Size. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020 Mar 18;56(3):135. [CrossRef]

- Manfré L, Lagalla R, Mangiameli A, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: orbital MRI. Neuroradiology. 1995 Aug;37(6):459-61. [CrossRef]

- Simon MJ, Iliff JJ. Regulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow in neurodegenerative, neurovascular and neuroinflammatory disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 Mar;1862(3):442-51. [CrossRef]

- Ghate D, Kedar S, Havens S, et al. The Effects of Acute Intracranial Pressure Changes on the Episcleral Venous Pressure, Retinal Vein Diameter and Intraocular Pressure in a Pig Model. Curr Eye Res. 2021;46(4), 524–531. [CrossRef]

- Lee SS, Robinson MR, Weinreb RN. Episcleral Venous Pressure and the Ocular Hypotensive Effects of Topical and Intracameral Prostaglandin Analogs. J Glaucoma. 2019 Sep;28(9):846-857. [CrossRef]

- Ngnitewe Massa R, Minutello K, Mesfin FB. Neuroanatomy, Cavernous Sinus. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459244/.

- Kiel JW. The Ocular Circulation. San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010. Chapter 2, Anatomy. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53329/#.

- Siaudvytyte L, Januleviciene I, Daveckaite A, et al. Literature review and meta-analysis of translaminar pressure difference in open-angle glaucoma. Eye (Lond). 2015 Oct;29(10):1242-50. [CrossRef]

- Morgan WH, Yu DY, Cooper RL, Alder VA, Cringle SJ, Constable IJ. The influence of cerebrospinal fluid pressure on the lamina cribrosa tissue pressure gradient. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995 May;36(6):1163-72.

- Mohammed NY, Di Domenico G, Gambaccini M. Cerebral venous drainage through internal jugular vein. Veins Lymphatics. 2019;8(1). [CrossRef]

- Yu ZY, Xing YQ, Li C, et al. Ultrasonic optic disc height combined with the optic nerve sheath diameter as a promising non-invasive marker of elevated intracranial pressure. Front Physiol. 2023 Mar 10;14:957758. [CrossRef]

- Raffiz M, Abdullah JM. Optic nerve sheath diameter measurement: a means of detecting raised ICP in adult traumatic and non-traumatic neurosurgical patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Jan;35(1):150-153. [CrossRef]

- Maissan IM, Dirven PJ, Haitsma IK, Hoeks SE, Gommers D, Stolker RJ. Ultrasonographic measured optic nerve sheath diameter as an accurate and quick monitor for changes in intracranial pressure. J Neurosurg. 2015 Sep;123(3):743-7. [CrossRef]

- Malky IE, Aita WE, Elkordy A, et al. Optic nerve sonographic parameters in idiopathic intracranial hypertension, case-control study. Sci Rep. 2025 Jan 13;15(1):1788. [CrossRef]

- Kishk NA, Ebraheim AM, Ashour AS, Badr NM, Eshra MA. Optic nerve sonographic examination to predict raised intracranial pressure in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: The cut-off points. Neuroradiol J.2018;31(5):490-495. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Chen Y, Xu L, et al. Venous system in acute brain injury: Mechanisms of pathophysiological change and function. Exp Neurol. 2015 Oct;272:4-10. [CrossRef]

- Doepp F, Schreiber SJ, von Münster T, Rademacher J, Klingebiel R, Valdueza JM. How does the blood leave the brain? A systematic ultrasound analysis of cerebral venous drainage patterns. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:565–70. [CrossRef]

- Margolin E. The swollen optic nerve: an approach to diagnosis and management. Pract Neurol. 2019 Aug;19(4):302-309. [CrossRef]

- Abdelnaby R, Elsayed M, Mohamed KA, et al. Sonographic Reference Values of Vagus Nerve: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2022 Jan 1;39(1):59-71. [CrossRef]

- Kiel M, Grabitz SD, Hopf S, et al. Distribution of Pupil Size and Associated Factors: Results from the Population-Based Gutenberg Health Study. J Ophthalmol. 2022 Sep 9;2022:9520512. [CrossRef]

- Couret D, Boumaza D, Grisotto C, et al. Reliability of standard pupillometry practice in neurocritical care: an observational, double-blinded study. Crit Care. 2016 Mar 13;20:99. [CrossRef]

- Hall CA, Chilcott RP. Eyeing up the Future of the Pupillary Light Reflex in Neurodiagnostics. Diagnostics (Basel). 2018 Mar 13;8(1):19. [CrossRef]

- Hamrakova A, Ondrejka I, Sekaninova N, et al. Central autonomic regulation assessed by pupillary light reflex is impaired in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Physiol Res. 2020 Dec 31;69(Suppl 3):S513-S521. [CrossRef]

- Karahan M, Demirtaş AA, Hazar L, et al. Autonomic dysfunction detection by an automatic pupillometer as a non-invasive test in patients recovered from COVID-19. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021 Sep;259(9):2821-2826. [CrossRef]

- Tsitsi P, Nilsson M, Waldthaler J, et al. Pupil light reflex dynamics in Parkinson's disease. Front Integr Neurosci. 2023 Aug 31;17:1249554. [CrossRef]

- Larsen RS, Waters J. Neuromodulatory Correlates of Pupil Dilation. Front Neural Circuits. 2018 Mar 9;12:21. [CrossRef]

- De Couck M, Mravec B, Gidron Y. You may need the vagus nerve to understand pathophysiology and to treat diseases. Clin Sci (Lond). 2012 Apr;122(7):323-8. [CrossRef]

- Mathôt S. Pupillometry: Psychology, Physiology, and Function. J Cogn. 2018 Feb 21;1(1):16. [CrossRef]

- David D, Giannini C, Chiarelli F, Mohn A. Text Neck Syndrome in Children and Adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Feb 7;18(4):1565. [CrossRef]

- Anbesu EW, Lema AK. Prevalence of computer vision syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2023 Jan 31;13(1):1801. [CrossRef]

- Watanuki A. [The effect of the sympathetic nervous system on cervical spondylosis (author's transl)]. Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Z. 1981 Apr;55(4):371-85. Japanese.

- Mitsuoka K, Kikutani T, Sato I. Morphological relationship between the superior cervical ganglion and cervical nerves in Japanese cadaver donors. Brain Behav. 2016 Dec 29;7(2):e00619. [CrossRef]

- D L A, Raju TR. Autonomic Nervous System and Control of Visual Function. Ann Neurosci. 2023 Jul;30(3):151-153. [CrossRef]

- Chawla JC, Falconer MA. Glossopharyngeal and vagal neuralgia. Br Med J. 1967 Aug 26;3(5564):529-31. [CrossRef]

- Cardinali DP, Vacas MI, Gejman PV. The sympathetic superior cervical ganglia as peripheral neuroendocrine centers. J Neural Transm.1981;52(1-2):1-21. [CrossRef]

- Mul Fedele ML, Galiana MD, Golombek DA, Muñoz EM, Plano SA. Alterations in Metabolism and Diurnal Rhythms following Bilateral Surgical Removal of the Superior Cervical Ganglia in Rats. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018 Jan 9;8:370. [CrossRef]

- Anterieu P, Vassal F, Sindou M. Vagoglossopharyngeal neuraligia revealed through predominant digestive vagal manifestations. Case report and literature review. Neurochirugie. 2016 Jun;62(3):174-7. [CrossRef]

- Kim JM, Park KH, Han SY, et al. Changes in intraocular pressure after pharmacologic pupil dilation. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012 Sep 27;12:53. [CrossRef]

- Lewczuk K, Jabłońska J, Konopińska J, Mariak Z, Rękas M. Schlemm's canal: the outflow 'vessel'. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022 Jun;100(4):e881-e890. [CrossRef]

- Tominaga Y, Maak TG, Ivancic PC, Panjabi MM, Cunningham BW. Head-turned rear impact causing dynamic cervical intervertebral foramen narrowing: implications for ganglion and nerve root injury. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006 May;4(5):380-7. [CrossRef]

- Chen HS, van Roon L, Ge Y, et al. The relevance of the superior cervical ganglion for cardiac autonomic innervation in health and disease: a systematic review. Clin Auton Res. 2024 Feb;34(1):45-77. [CrossRef]

- Dieguez HH, Romeo HE, González Fleitas MF, et al. Superior cervical gangliectomy induces non-exudative age-related macular degeneration in mice. Dis Model Mech. 2018 Feb 7;11(2):dmm031641. [CrossRef]

- Betsch M, Kalbhen K, Michalik R, et al. The influence of smartphone use on spinal posture - A laboratory study. Gait Posture. 2021 Mar;85:298-303. [CrossRef]

- Anderson M, Jiang J. (2018, May 31). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/ Accessed April 2. 2025.

- DemandSage. (2024). Screen time statistics: 2024 data and trends. DemandSage. https://www.demandsage.com/screen-time-statistics/ Accessed March 5, 2025.

- Tsang SMH, Cheing GLY, Lam AKC, et al. Excessive use of electronic devices among children and adolescents is associated with musculoskeletal symptoms, visual symptoms, psychosocial health, and quality of life: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2023 Jun 29;11:1178769. [CrossRef]

- Vij N, Tolson H, Kiernan H, Agusala V, Viswanath O, Urits I. Pathoanatomy, biomechanics, and treatment of upper cervical ligamentous instability: A literature review. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2022 Aug 5;14(3):37099. [CrossRef]

- Olson KA, Joder D. Diagnosis and treatment of cervical spine clinical instability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2001 Apr;31(4):194-206. [CrossRef]

- D'Angelo A, Vitiello L, Lixi F, et al. Optic Nerve Neuroprotection in Glaucoma: A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2024 Apr 11;13(8):2214. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm H, Schabet M. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Optic Neuritis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015 Sep 11;112(37):616-25; quiz 626. [CrossRef]

- Bennett JL. Optic Neuritis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019 Oct;25(5):1236-1264. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Sun Y, Chan CC, Fan C, Ji X, Meng R. Internal jugular vein stenosis associated with elongated styloid process: five case reports and literature review. BMC Neurol. 2019 Jun 4;19(1):112. [CrossRef]

- Toshniwal SS, Kinkar J, Chadha Y, et al. Navigating the Enigma: A Comprehensive Review of Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Cureus. 2024 Mar 16;16(3):e56256. [CrossRef]

- Fargen KM, Midtlien JP, Margraf CR, Hui FK. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension pathogenesis: The jugular hypothesis. Interv Neuroradiol. 2024 Aug 8:15910199241270660. [CrossRef]

- Tuță S. Cerebral Venous Outflow Implications in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension-From Physiopathology to Treatment. Life (Basel). 2022 Jun 8;12(6):854. [CrossRef]

- Hassen GW, Al-Juboori M, Koppel B, Akfirat G, Kalantari H. Real time optic nerve sheath diameter measurement during lumbar puncture. Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Apr;36(4):736.e1-736.e3. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Zhang XX, Yang HQ, et al. [Correlation between ultrasonographic optic nerve sheath diameter and intracranial pressure]. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2018 Sep 11;54(9):683-687. Chinese. [CrossRef]

- Robba C, Santori G, Czosnyka M, et al. Optic nerve sheath diameter measured sonographically as non-invasive estimator of intracranial pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2018 Aug;44(8):1284-1294. [CrossRef]

- Wang LJ, Chen LM, Chen Y, et al. Ultrasonography Assessments of Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter as a Noninvasive and Dynamic Method of Detecting Changes in Intracranial Pressure. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018 Mar 1;136(3):250-256. [CrossRef]

- Hylkema C. Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter Ultrasound and the Diagnosis of Increased Intracranial Pressure. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2016 Mar;28(1):95-9. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu E, Gupta N, Ahari A, Zhou X, Hanna J, Yücel YH. Evidence for Cerebrospinal Fluid Entry Into the Optic Nerve via a Glymphatic Pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017 Sep 1;58(11):4784-4791. [CrossRef]

- Ertl M, Knüppel C, Veitweber M, et al. Normal Age- and Sex-Related Values of the Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter and Its Dependency on Position and Positive End-Expiratory Pressure. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020 Dec;46(12):3279-3285. [CrossRef]

- Lochner P, Brio F, Zedde ML, et al. Feasibility and usefulness of ultrasonography in idiopathic intracranial hypertension or secondary intracranial hypertension. BMC Neurol. 2016 Jun 2;16:85. [CrossRef]

- Ussahgij W, Toonpirom W, Munkong W, Ienghong K. Optic nerve sheath diameter cutoff point for detection of increased intracranial pressure in the emergency room. Maced J Med Sci. 2020. Feb 25; 8(B): 62-65. [CrossRef]

- Lee SJ, Choi MH, Lee SE, et al. Optic nerve sheath diameter change in prediction of malignant cerebral edema in ischemic stroke: an observational study. BMC Neurol. 2020 Sep 22;20(1):354. [CrossRef]

- Dubourg J, Javouhey E, Geeraerts T, Messerer M, Kassai B. Ultrasonography of optic nerve sheath diameter for detection of raised intracranial pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2011 Jul;37(7):1059-68. [CrossRef]

- Berberat J, Pircher A, Gruber P, Lovblad KO, Remonda L, Killer HE. Case Report: Cerebrospinal Fluid Dynamics in the Optic Nerve Subarachnoid Space and the Brain Applying Diffusion Weighted MRI in Patients With Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension-A Pilot Study. Front Neurol. 2022 Apr 15;13:862808. [CrossRef]

- Sarrami AH, Bass DI, Rutman AM, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension imaging approaches and the implications in patient management. Br J Radiol. 2022 Aug 1;95(1136):20220136. [CrossRef]

- Bozdoğan Z, Şenel E, Özmuk Ö, Karataş H, Kurşun O. Comparison of Optic Nerve Sheath Diameters Measured by Optic Ultrasonography Before and After Lumbar Puncture in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Patients. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2023 May 5;60(2):117-123. [CrossRef]

- Zaic S, Krajnc N, Macher S, et al. Therapeutic effect of a single lumbar puncture in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Headache Pain. 2024 Sep 5;25(1):145. [CrossRef]

- Dinkin M, Oliveira C. Men Are from Mars, Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Is from Venous: The Role of Venous Sinus Stenosis and Stenting in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Semin Neurol. 2019 Dec;39(6):692-703. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, McGuinness MB, Anderson AJ, Downie LE. Interventions for the Management of Computer Vision Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2022 Oct;129(10):1192-1215. [CrossRef]

- Zamysłowska-Szmytke E, Adamczewski T, Ziąber J, Majak J, Kujawa J, Śliwińska-Kowalska M. Cervico-ocular reflex upregulation in dizzy patients with asymmetric neck pathology. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2019 Oct 16;32(5):723-733. [CrossRef]

- Huckemann S, Mueller K, Averdunk P, et al. Vagal cross-sectional area correlates with parasympathetic dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Brain Commun. 2023 Jan 18;5(1):fcad006. [CrossRef]

- Goldberger JJ, Arora R, Buckley U, Shivkumar K. Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction: JACC Focus Seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Mar 19;73(10):1189-1206. [CrossRef]

- Zanin A, Amah G, Chakroun S, et al. Parasympathetic autonomic dysfunction is more often evidenced than sympathetic autonomic dysfunction in fluctuating and polymorphic symptoms of "long-COVID" patients. Sci Rep. 2023 May 22;13(1):8251. [CrossRef]

- Murakami A. Autonomic nervous system dysfunction in ocular diseases. Juntendon Med J. 2016;62:377-380. [CrossRef]

- Kaido M, Arita R, Mitsukura Y, Ishida R, Tsubota K. Variability of autonomic nerve activity in dry eye with decreased tear stability. PLoS One. 2022 Nov 16;17(11):e0276945. [CrossRef]

- Park HL, Jung SH, Park SH, Park CK. Detecting autonomic dysfunction in patients with glaucoma using dynamic pupillometry. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Mar;98(11):e14658. [CrossRef]

- Jain D, Arbogast K, McDonald C. Objective eye tracking metrics of vision and autonomic dysfunction distinguish adolescents with acute concussion and those with persistent post-concussion symptoms from uninjured controls. Neurology. 2022;98. [CrossRef]

- Manion GN, Stokkermans TJ. The Effect of Pupil Size on Visual Resolution. [Updated 2024 Feb 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK603732/?utm_source=chatgpt.com Accessed April 3, 2025.

- [1] Bittner DM, Wieseler I, Wilhelm H, Riepe MW, Müller NG. Repetitive pupil light reflex: potential marker in Alzheimer's disease? J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(4):1469-77. [CrossRef]

- [1] Gallar J, Liu JH. Stimulation of the cervical sympathetic nerves increases intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993 Mar;34(3):596-605.

- Mitsuoka K, Kikutani T, Sato I. Morphological relationship between the superior cervical ganglion and cervical nerves in Japanese cadaver donors. Brain Behav. 2016 Dec 29;7(2):e00619. [CrossRef]

- Khalid K, Padda J, Pokhriyal S, et al. Pseudomyopia and Its Association With Anxiety. Cureus. 2021 Aug 24;13(8):e17411. [CrossRef]

- Kasumovic M, Gorcevic E, Gorcevic S, Osmanovic J. Cervical syndrome - the effectiveness of physical therapy interventions. Med Arch. 2013 Dec;67(6):414-7. [CrossRef]

- Moustafa IM, Diab AA, Hegazy F, Harrison DE. Demonstration of central conduction time and neuroplastic changes after cervical lordosis rehabilitation in asymptomatic subjects: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2021 Jul 28;11(1):15379. [CrossRef]

| Testing Parameters | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| C6AI | 41.67 mm | 14.12 |

| Depth of curve | 2.68 mm | 3.86 |

| Flexion instability total* | 4.36 mm | 3.18 |

| Extension instability total* | 4.27 mm | 3.35 |

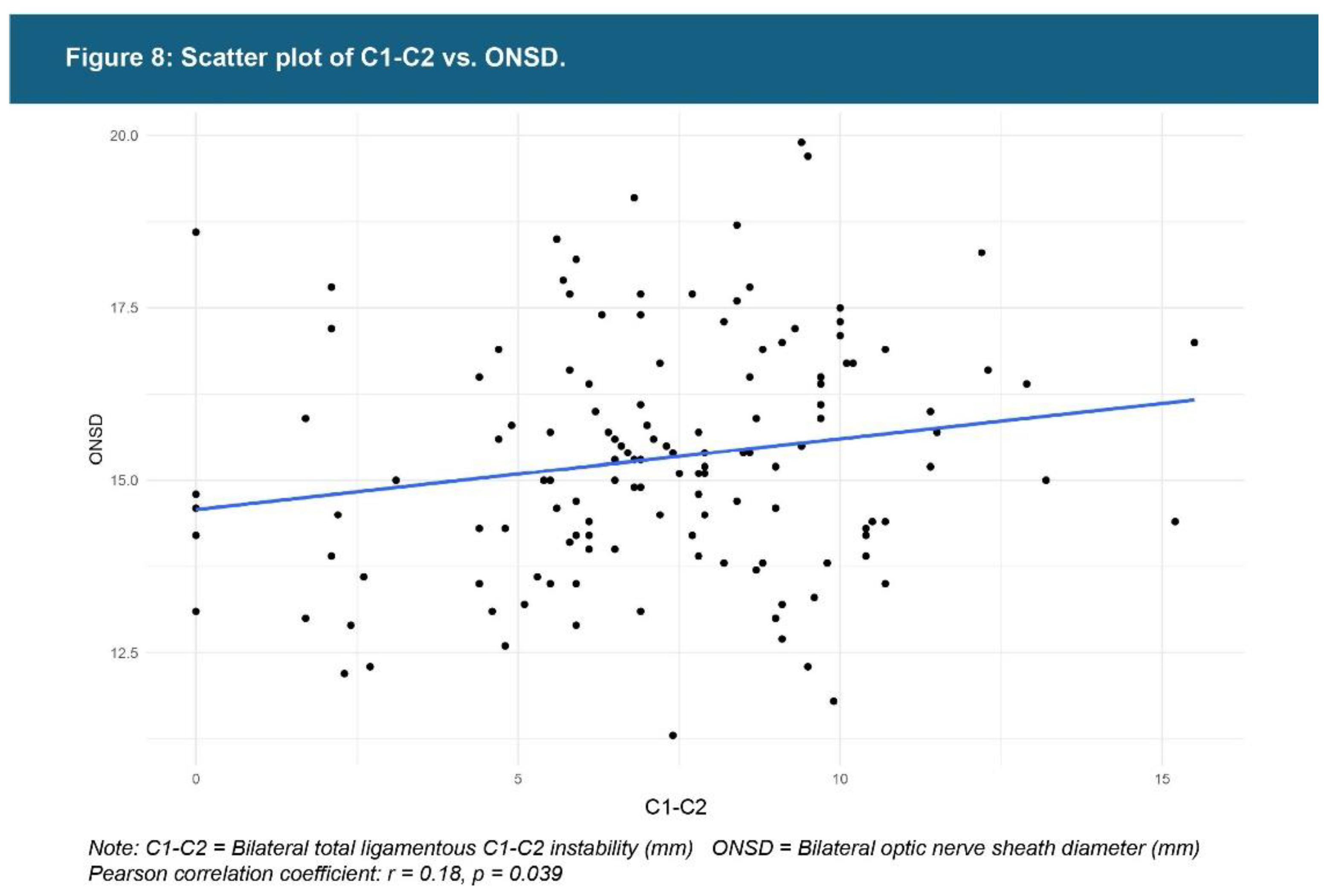

| C1-C2 facet joint instability** | 7.19 mm | 2.98 |

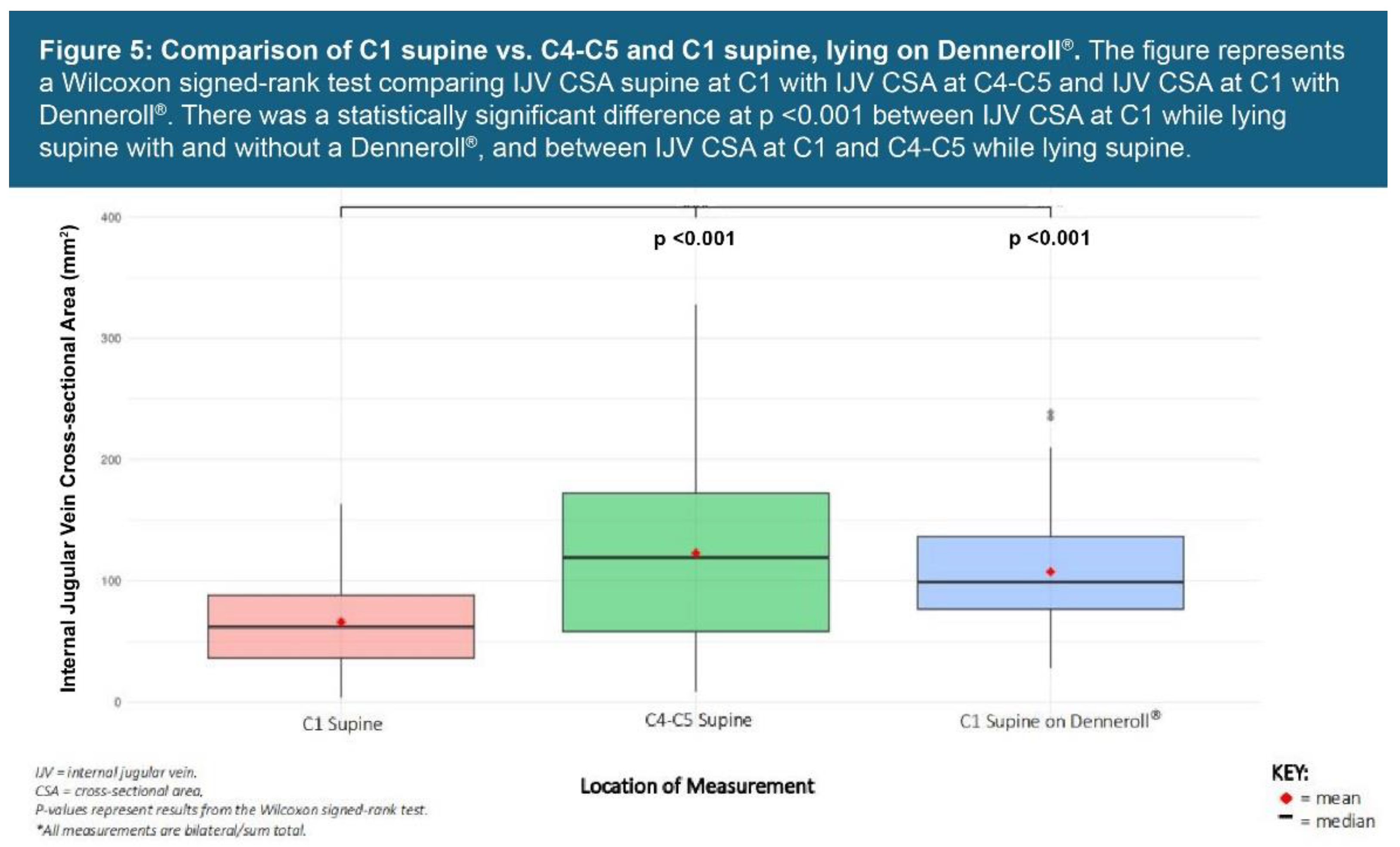

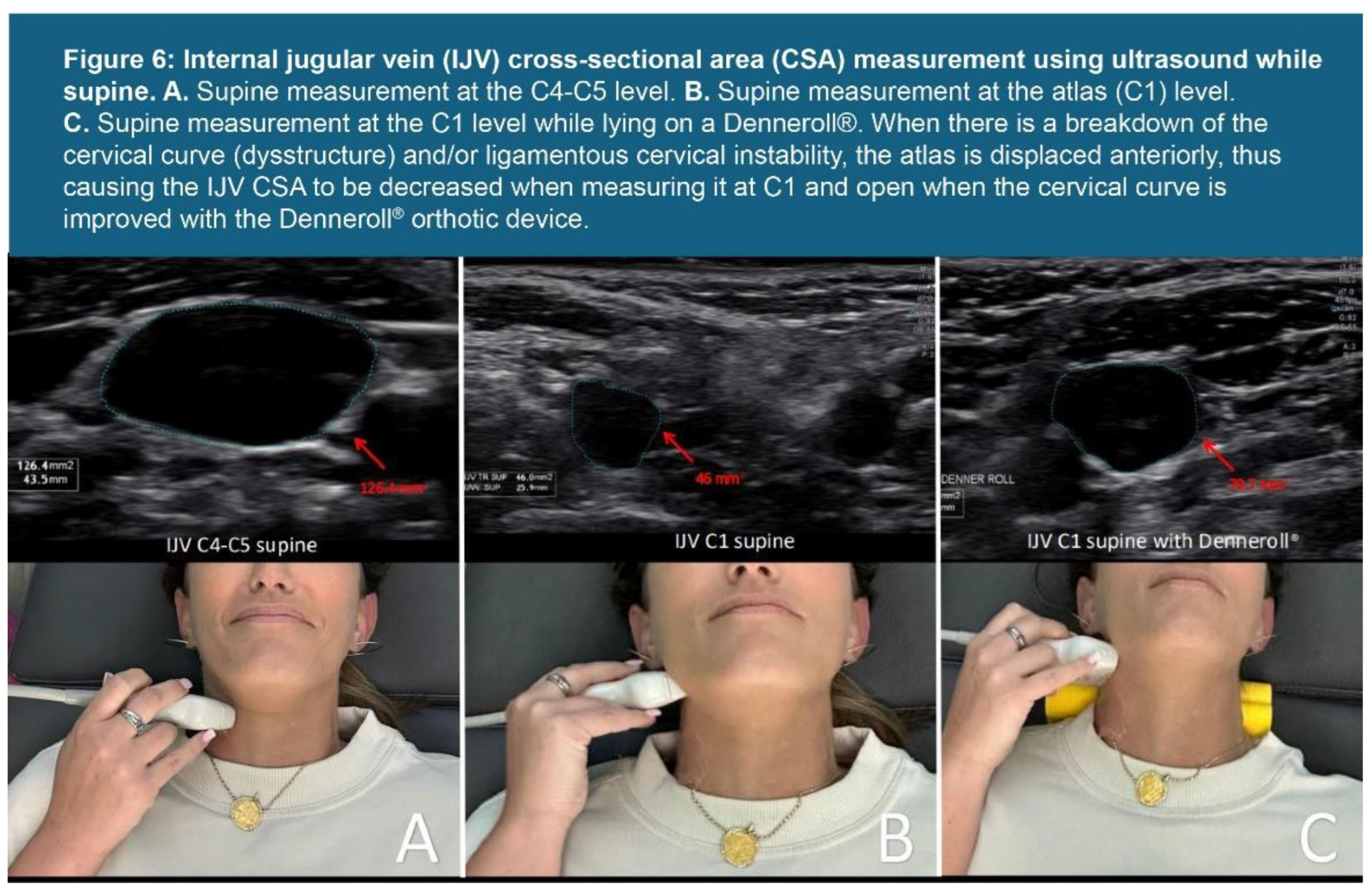

| IJV C4-C5 supine** | 131.79 mm2 | 83.66 |

| IJV CSA C1 supine** | 68.94 mm2 | 37.95 |

| IJV CSA C1 supine with Denneroll® (n = 131)** |

111.20 mm2 | 48.30 |

| Vagus nerve CSA** | 2.69 mm2 | 0.82 |

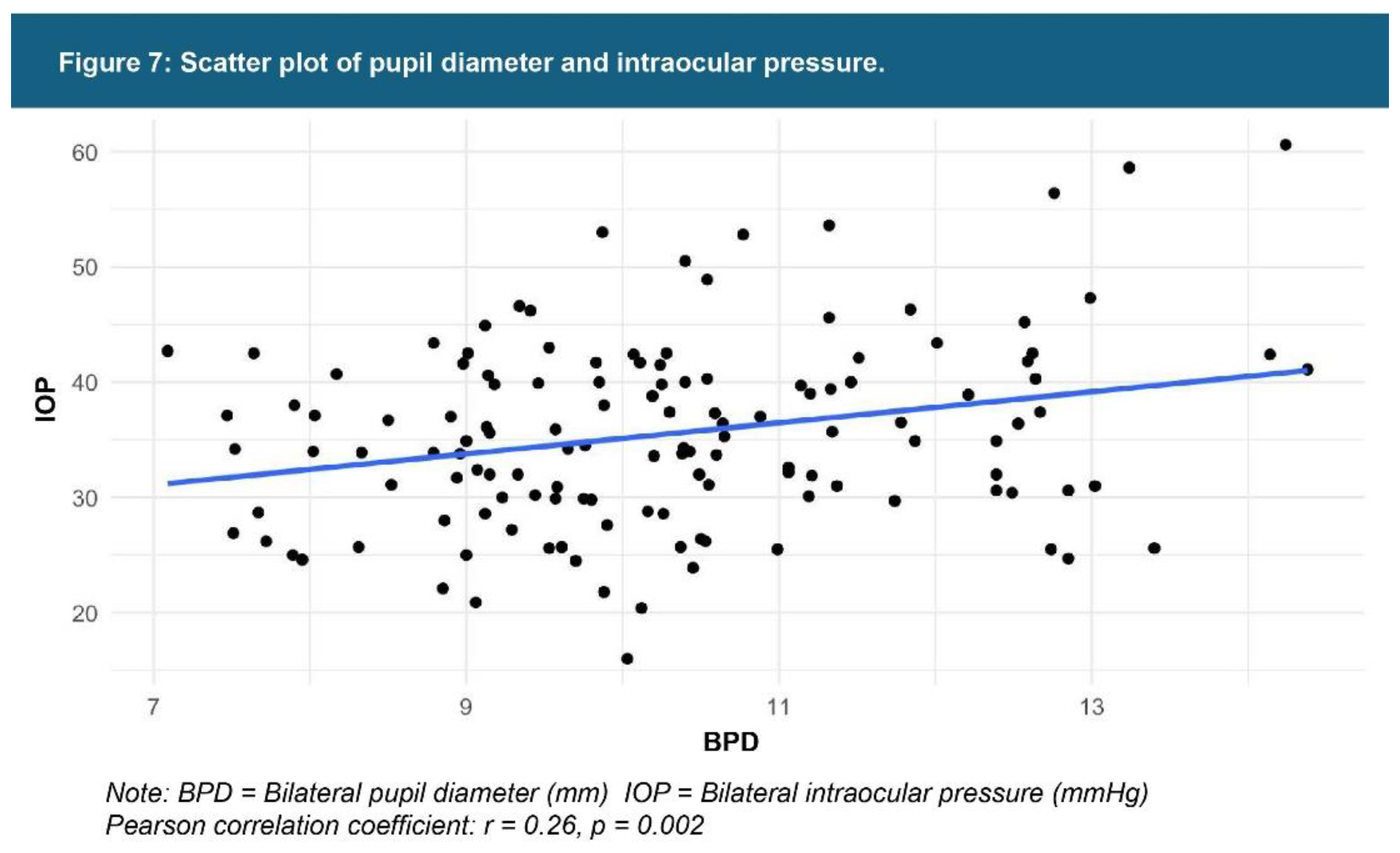

| Pupil diameter** | 10.34 mm | 1.55 |

| Intraocular pressure** | 35.71 mmHg | 8.33 |

| ONSD** | 15.35 mm | 1.71 |

| Percent change (light reflex)** | 74.70% | 10.41 |

| Testing Parameters | % Abnormal Findings (Number of Patients) | Established Normal Values |

|---|---|---|

| C6AI | 100% (145) | <10 mm |

| Depth of curve (n = 144) | 89% (128) | 7-17 mm |

| C1-C2 facet joint instability* | 88% (127) | <4 mm |

| Flexion/extension instability C2-C6** | 88% (127) | <4 mm |

| Vagus nerve CSA* | 95% (138) | >4.2 mm |

| IJV CSA C1 supine* | 99% (143) | >180 mm |

| IJV C4/C5 supine* | 76% (110) | >180 mm |

| IJV CSA C1 supine with Denneroll® (n = 131)* |

90% (118) | >180 mm |

| Pupil diameter* | 92% (134) | <8 mm |

| ONSD* | 98% (142) | <12.2 mm |

| Percent change (light reflex)* | 95% (138) | <60% |

| Intraocular pressure* | 19% (28) | <42 mmHg |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).