3.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

This study used NBA game log data from the 2024-25 season, collected as of January 5, 2024. Multiple datasets were collected though an API including game-level information, individual player performance metrics, player metadata, and seasonal statistics. The study focused on the current season data to make sure the study provides timely insights because NBA games are fast-changing and highly time-sensitive.

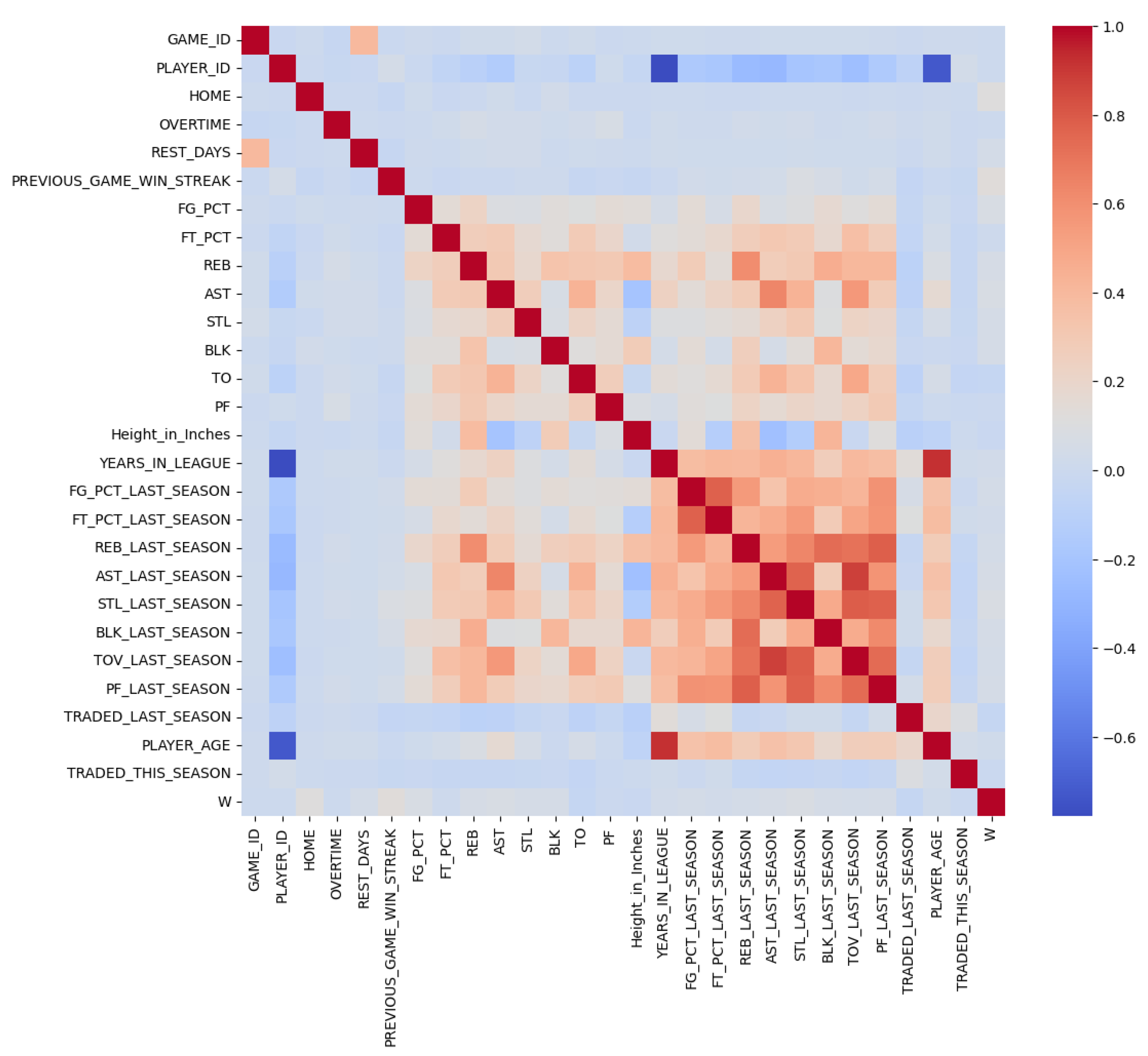

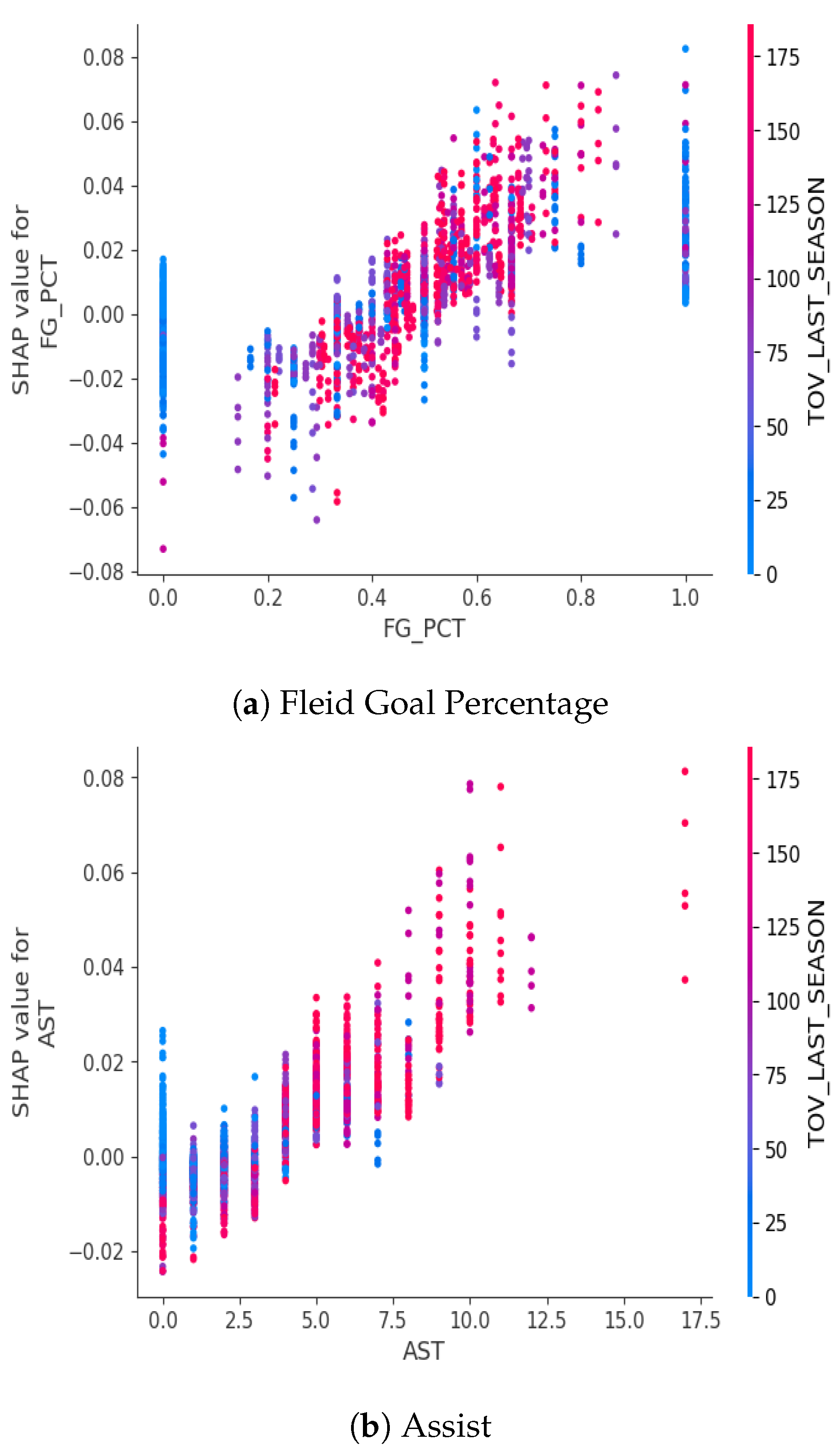

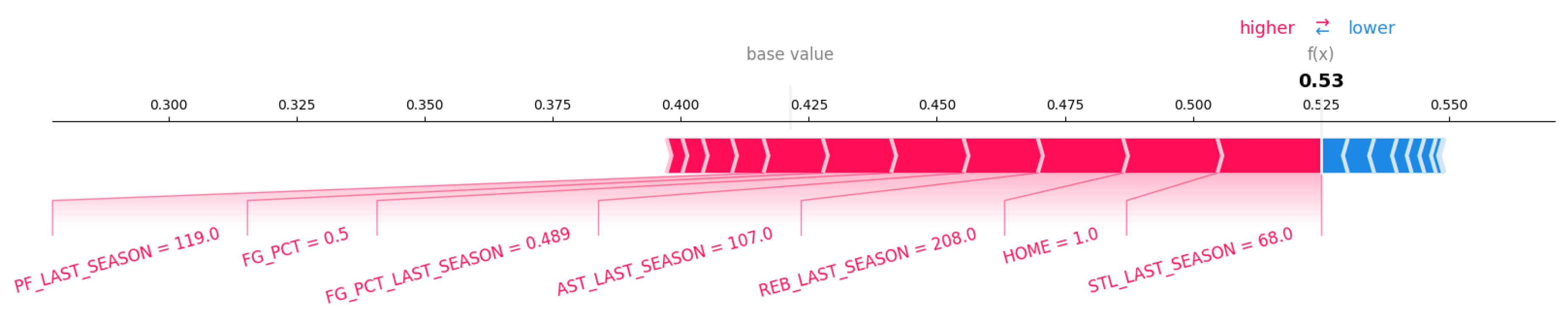

Data were collected from nba.stats.com using an API. The game information included the result of the game (win vs. lose), which was used as a response variable in this study. The player performance metrics were collected for each game and included field goal percentage, free throw percentage, rebound, assist, steal, block, turnovers, and personal fouls. Initial correlation analysis was conducted to manually remove the highly correlated variables. This manual feature selection helped improve the model interpretability. For example, the total points and total minutes a player played during a game were excluded. This is because key players typically play longer and score higher than bench players, which also reflects on other metrics like total points, field goal percentage, and free throw percentage. The player metadata included players’ heights and years in the league. Weights were excluded because they were highly correlated with height. Seasonal player data had two parts, including the previous season and the current season. The data from the previous season included the overall percentage of field goals, the percentage of free throws, rebound, assist, steal, block, turnovers, personal fouls, and if the player was traded in the previous season. The current season data included player’s age, player’s team, and if the player was traded in the current season.

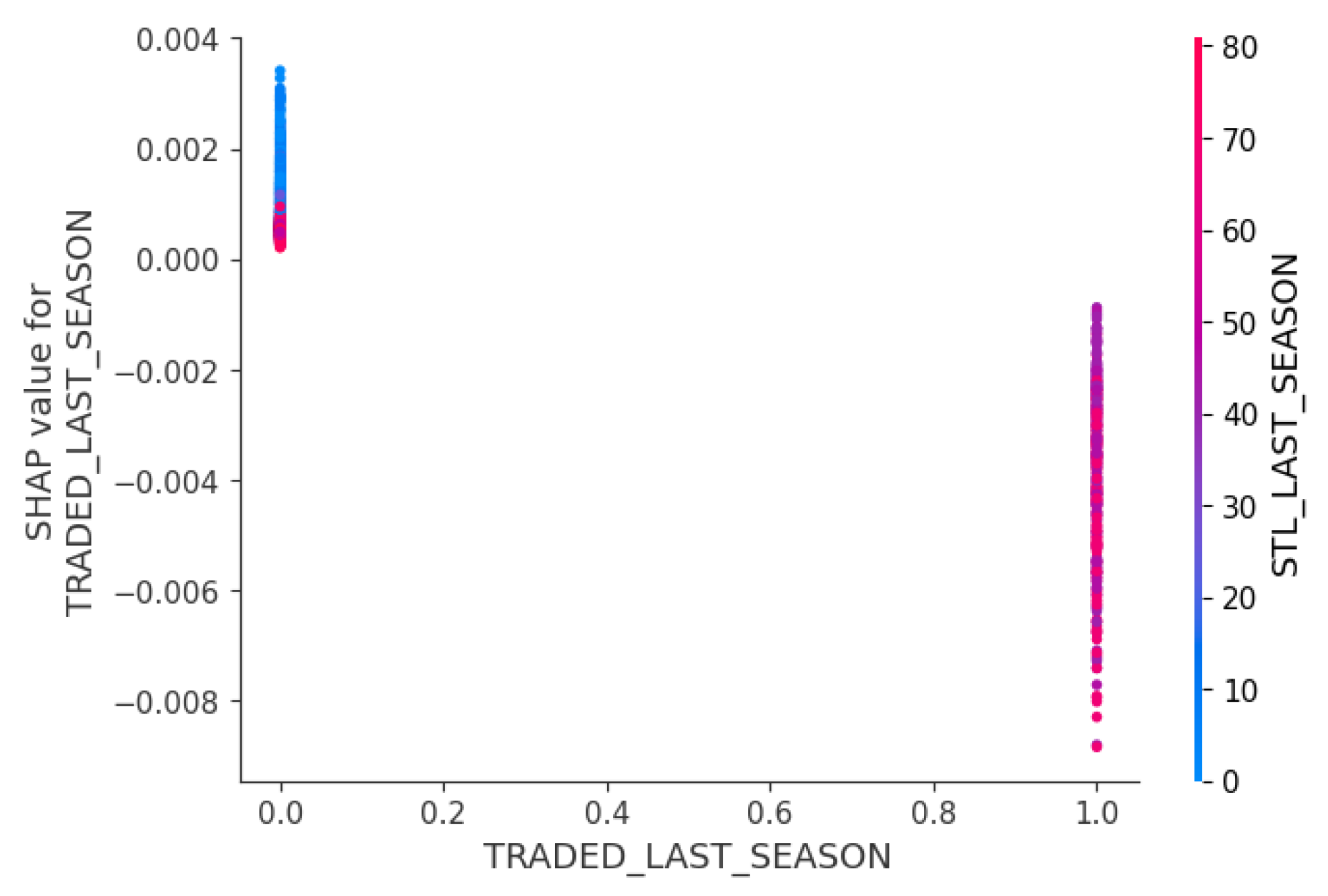

Pre-processing included handling missing data, removing outliers, and encoding categorical features to reduce the noise in the data. Missing values for previous season stats including steals (STL_LAST_SEASON) and turnovers (TOV_LAST_SEASON) were set to 0. This could be related to new players or injured players who did not play in the previous season. This process helped avoid errors in the model training process. Whether or not the player was traded last season (TRADED_LAST_SEASON) was also set to 0 when the player was not traded in the previous season. The total minute each player played each game was calculated. The original variable included minutes and seconds, for example, 35:14. Thus, the original variable was converted to the seconds and converted to the total minutes by dividing by 60. Players who played less than 1 minute in a game were excluded because the player scores were unlikely to be relevant to the overall game performance. Categorical variables such as team names, game identifiers, and player identifiers were encoded to be used in the machine learning models.

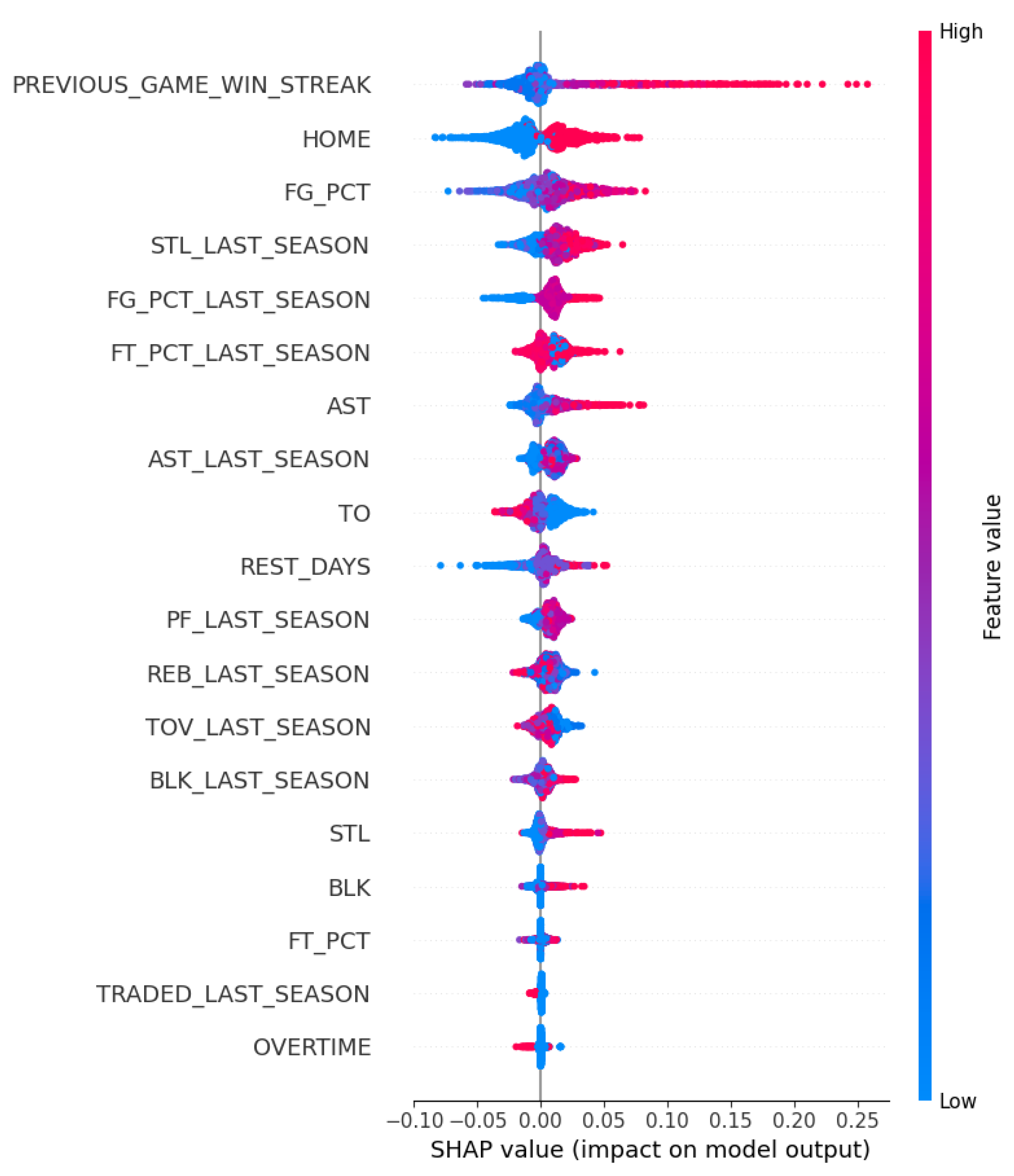

Feature engineering was conducted through creating new features, including height in inches, overtime indicator, rest days, home game indicator, and preceding game win streak, to provide additional context to the model and improve the predictive power.

Appendix A shows the variables used in the final model. The correlation analysis was conducted to see the relationships between final variables before the model building stage.

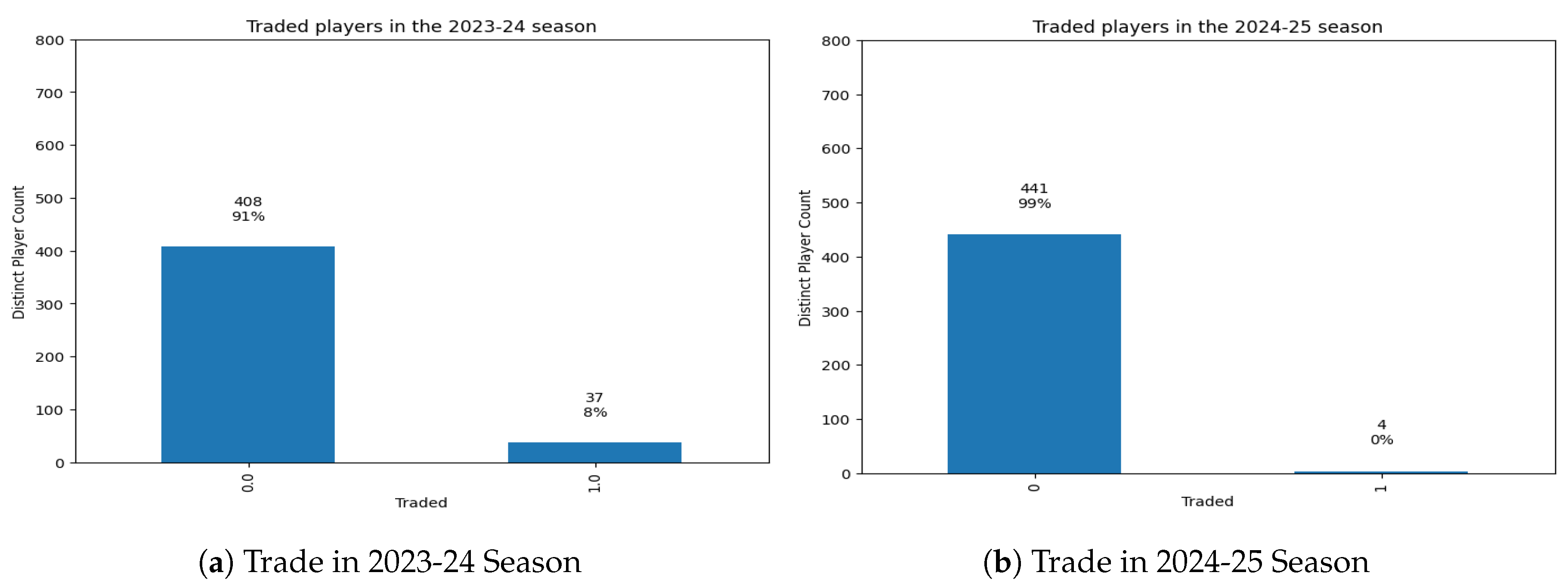

The traded indicators for 2024-25 and 2023-24 seasons were created to see if a player was traded. This was expected to show the trade impact on the team in the model. The career stats were pulled for each player. Players with the team name ’TOT’ (Total) indicated as the players had been traded mid-season by showing total stats across the two teams (previous team and traded team).

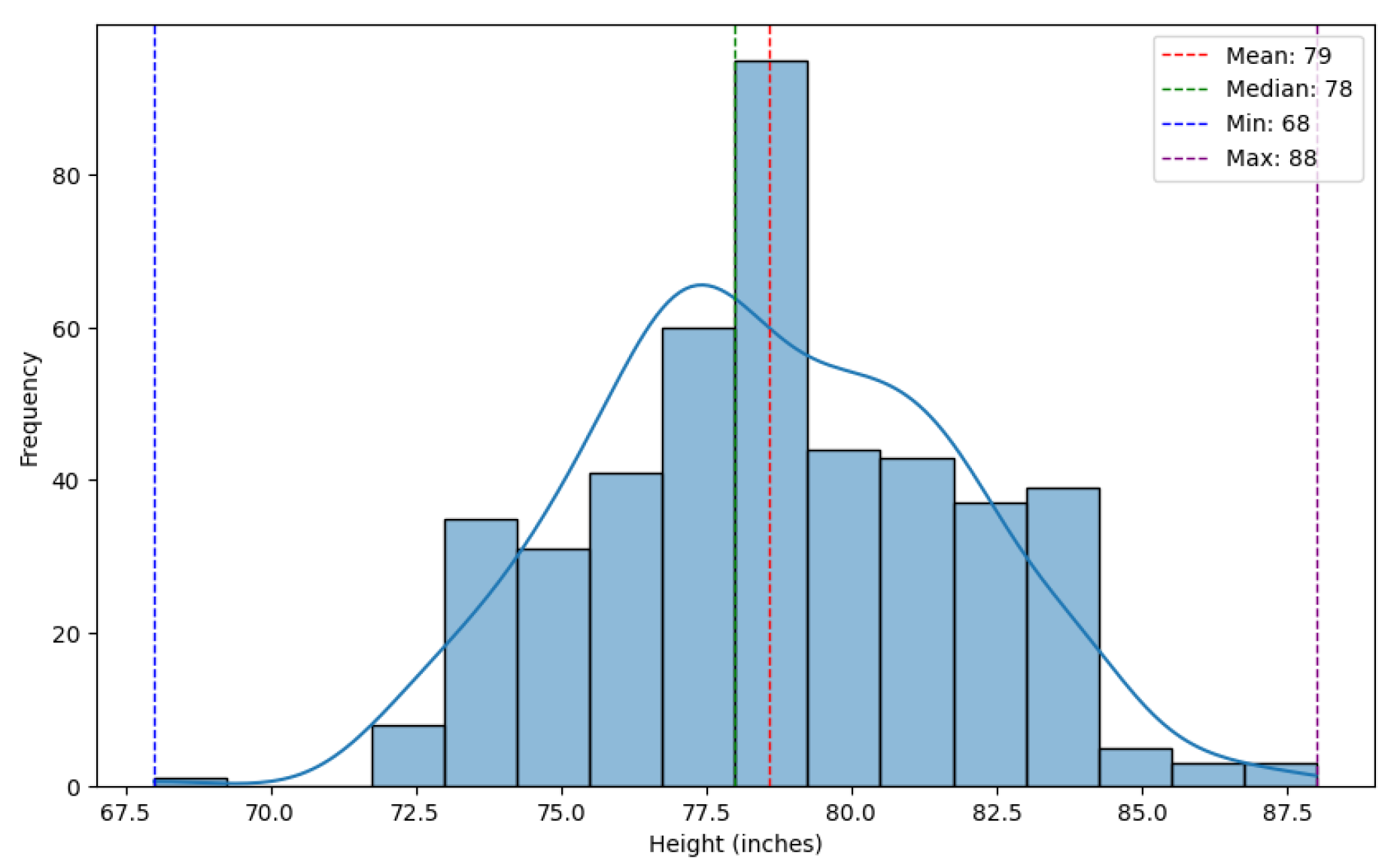

The heights were recorded as feet and inches. Thus, the variable was converted to inches to be used in the machine learning models.

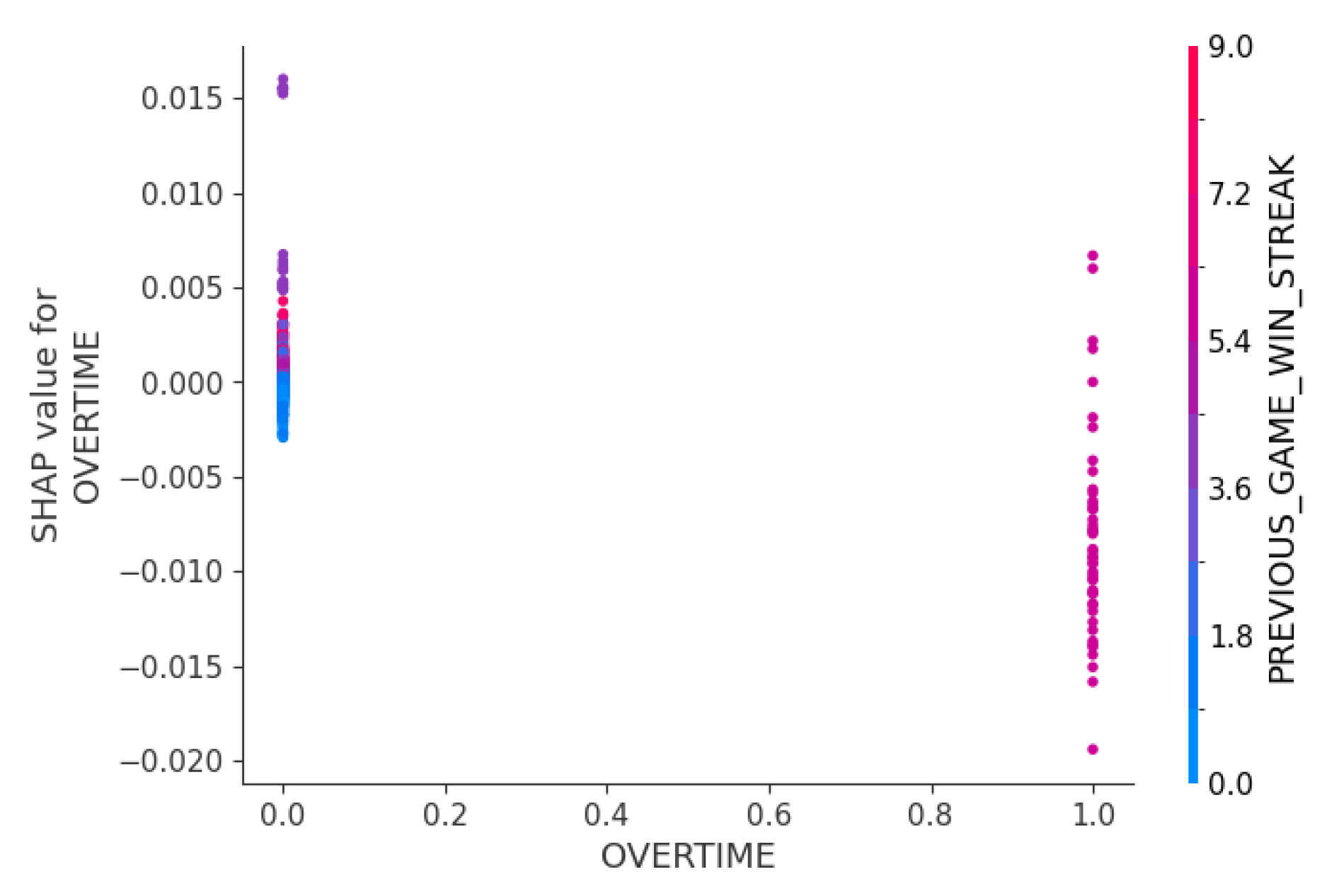

The overtime indicator was to understand if an overtime game makes outcomes harder to predict due to the narrow scoring margins. Any game time with more than 240 minutes (minutes per player on the court) in the data was encoded as 1. 240 minutes represents minutes per player on the court. There are 5 players on the court per team and 12-minutes quarters.

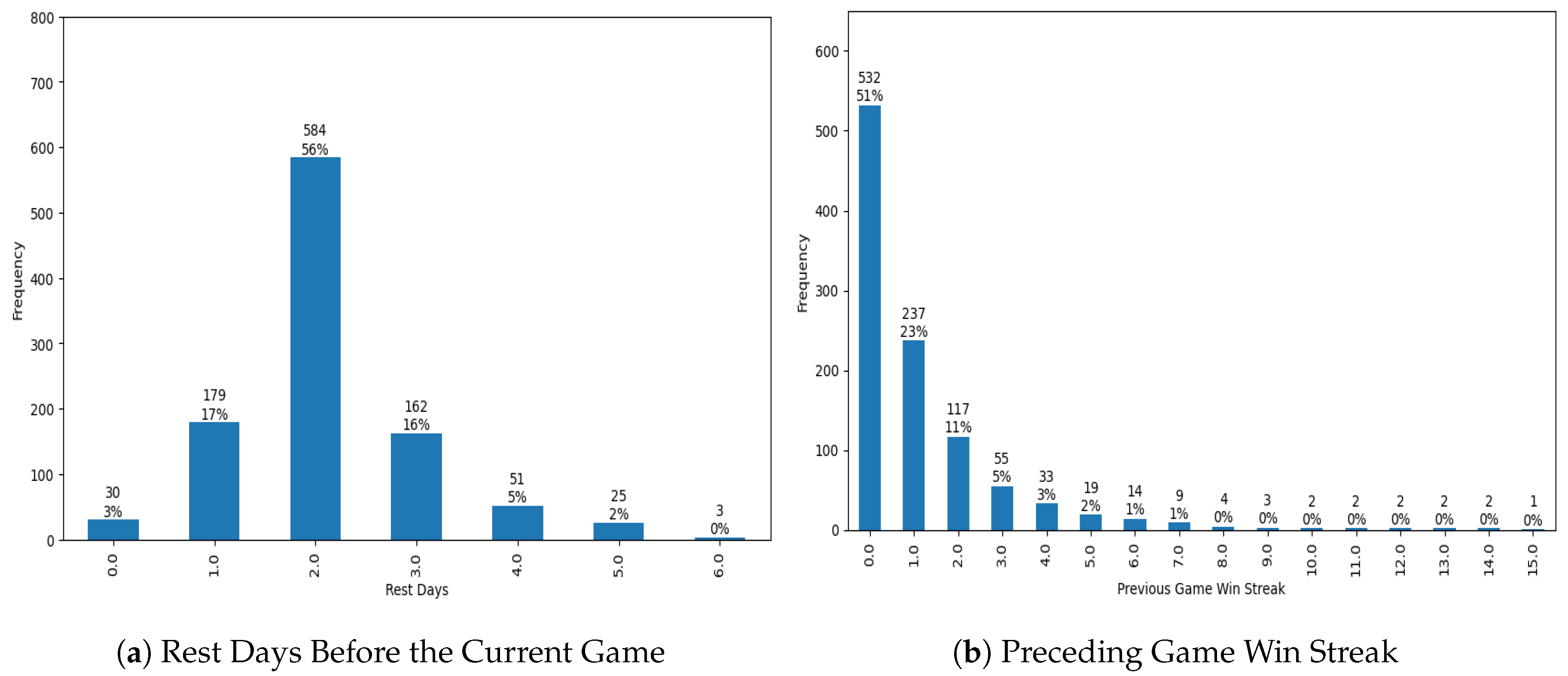

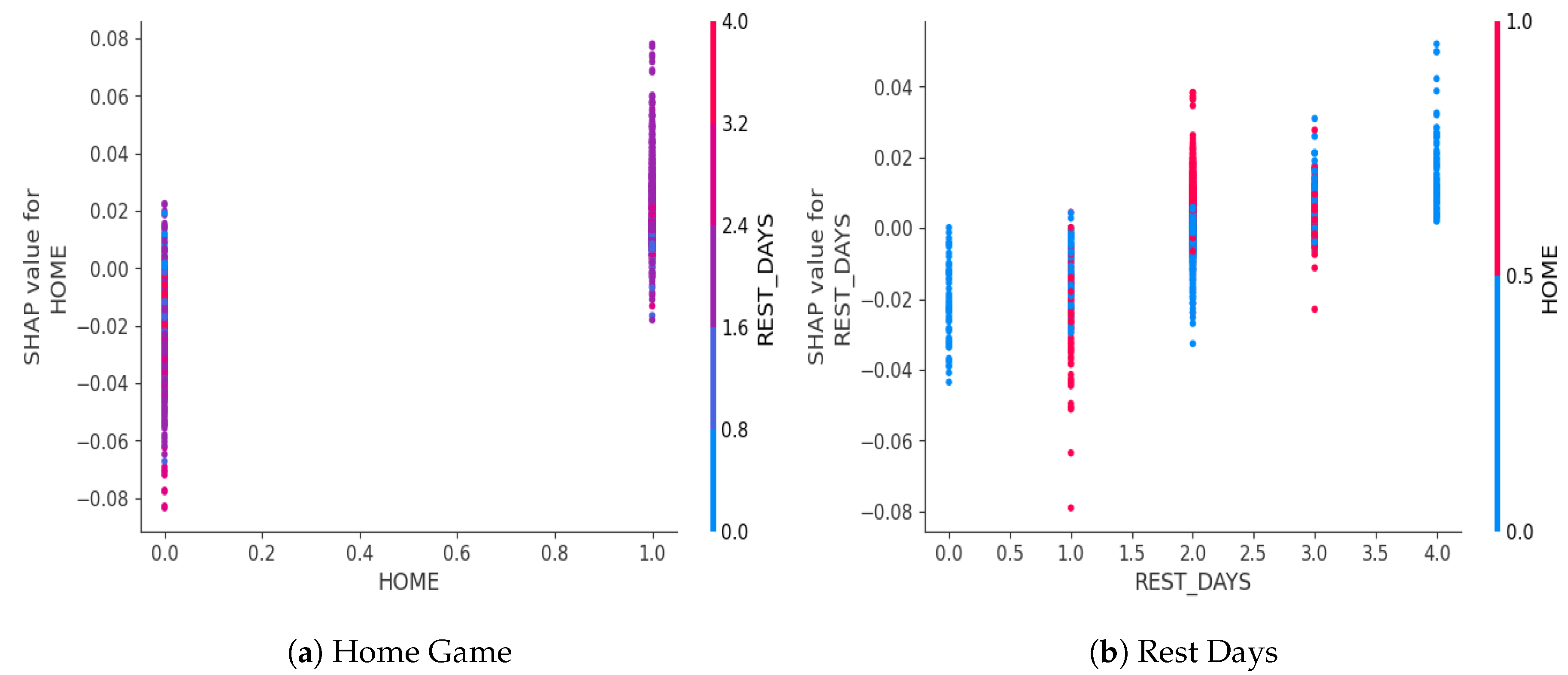

The rest days counter was used to understand the level of team’s fatigue. It was less precise compared to the wearable data. However, it was the best available estimate of fatigue level assuming all other factors including training routines are the same. First, the game log was sorted by game date for each team. Then, the difference between consecutive games was evaluated. The first game for each team did not have the preceding game to compare. Thus, rest days for these games were set to 0.

The home game indicator was created to see if teams are more familiar with their home stadium and how this would impact the game results. In the game-related data, the game match variable showed if the game was a home game (NYK vs. BOS) or away game (NYC @ BOS, which means New York team at Boston’s stadium). Thus, if the variable included ’vs.’ the game was encoded as a home game (1), otherwise as an away game (0).

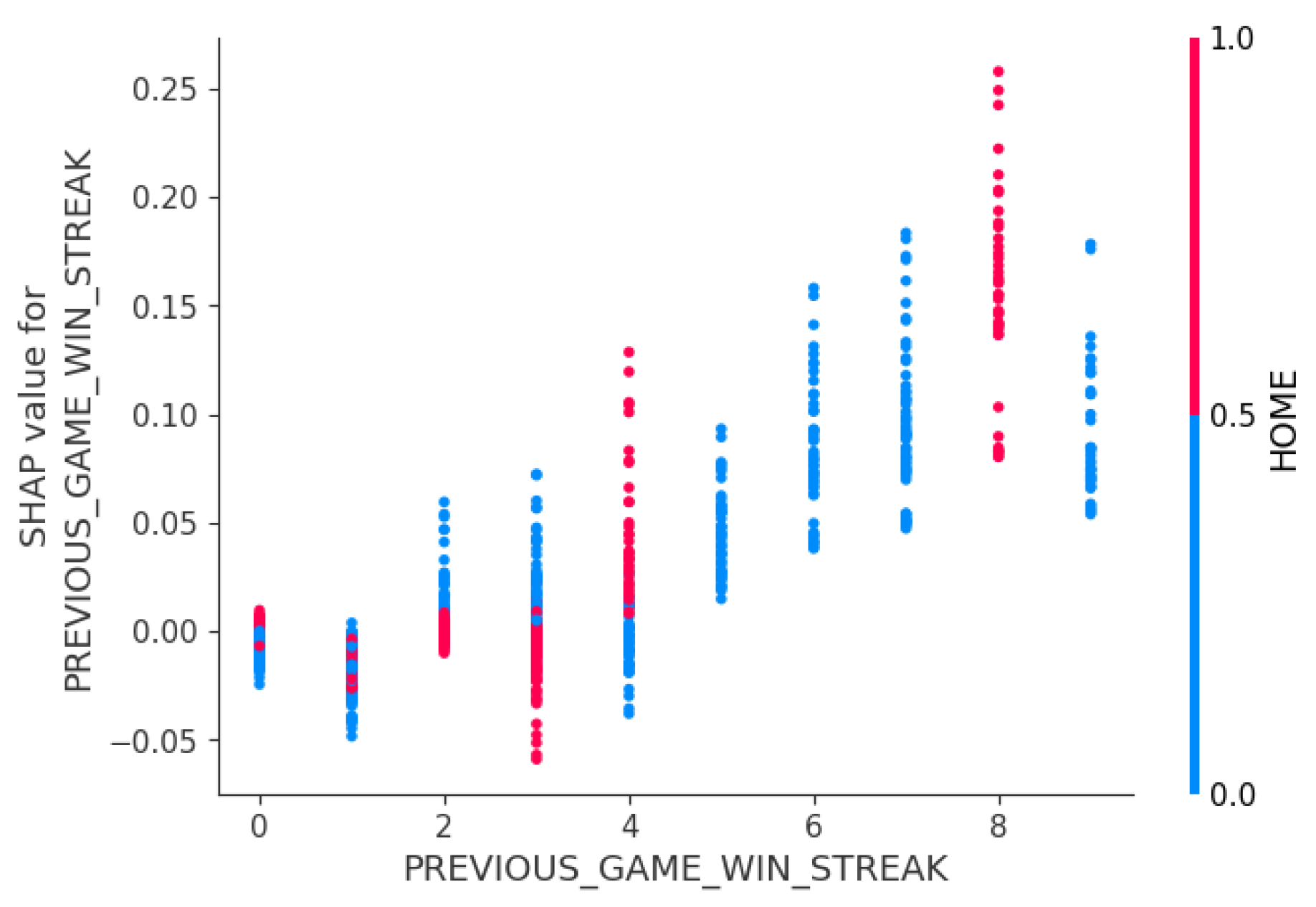

The preceding game win streak was to understand if the consistent recent wins would impact the current game outcome. First, the data were sorted by team identifier and the game date to get the chronological order. For each team, a counter was generated to track the consecutive wins. If the current game result was ’W’ then the counter added 1 and if the current game result was ’L’ then the counter was reset to 0. This variable was appended as a new column for each team and the game. For the previous game win streak, the variable for the current game was shifted down by one game for each team. The first games of the season were set to 0 because these games did not have any previous game results.

The game identifier and player identifier were encoded as the model inputs to make sure each record represented a player and a game, which helped prevent data leakage. This helped the model link the player performance, game condition, and results during the training process. In the testing and validation, the model would see similar patterns in previously unseen players and games.

The data were split into training, validation, and test for the final model. The training set included all the teams except Boston Celtics and New York Knicks, the validation set included only Boston Celtics player and game data, and the test set included New York team player and game data. The split was to evaluate the model’s ability to generalize across different teams. As a result, the proportion for training, test, and validation datasets were was 93%, 3%, and 3% respectively.

The team names were excluded from the model inputs because the model tended to prioritize the higher-performing teams such as Cleveland Cavaliers and Oklahoma City Thunder. Thus, the model was overfitting towards to the performance patterns of these teams using the training set and made it less generalizable when testing and validating on the new sets of data. This also helped the model become less dependent on the team strategies, which was difficult to measure with the current data inputs. Thus, the model was set up to learn the general patterns from the overall player statistics and games-related data without team indicators and predict the game outcomes for specific teams.

3.2. Model Selection and Training

The models were built with XGBoost Classifier and optimized to predict the game outcomes. The final model used only the XGBoost model due to the time limitation. Future suggestions included considering different models to compare and improve model performance. Initially, the base model without optimization was constructed to compare the performance with the optimized model. Then, another model with five random seeds and hyperparameter tuning process, but without systematic feature selection and train-test-validation split strategy. The train-test-validation split was not based on teams but rather on overall player and game data. Lastly, the final model with five random seeds, hyperparameter tuning, systematic feature selection, and a team-based train-test-validation split outperformed the rest of the models.

Five random seeds were generated with a reproducible process. The word "NBA" was converted into a unique large number using the MD5 hashing algorithm provided by the hashlib package. This large number can be linked back to the original input string ’NBA’. The large number was then used to feed the random number generator using the random package. Because this large number was unique, the generated random numbers were reproducible as long as the first input string was the same. Then, ten random numbers were generated within the range of 0 to 2,147,483,647. The first five random numbers were 1578879816, 1978497697, 1190903919, 1878057853, and 1288653849, and were used as seeds for 5 different runs.

The

Optuna package was used to automate feature selection and hyperparameter optimization [

9]. In this study, an

Optuna study object ran 20 trials to search for the best combination of hyperparameters and features. The study was run with five different random seeds to improve the stability of the model predictions. Within

Optuna study object, the process involved four steps including feature selection, initial model training on selected features, hyperparameter optimization, and final model testing.

Various ranges of hyperparameters were considered including the number of parallel trees, maximum tree depth, learning rate, subsample, features sampled for each tree, minimum child weight, gamma, alpha, and lambda [

10]. The optimal number of trees was explored in a range from 50 to 500. Less than 50 trees would introduce high bias and more than 500 trees would introduce overfitting [

10]. [

11] compared the XGBoost model performance across 24 different datasets and the models that produced the highest prediction accuracy were observed when the models used a number of trees in the range of 50 to 500.

The optimal depth for individual trees was explored in a range from 3 to 100 to balance the model complexity. Low tree depth would introduce high bias and high tree depth would introduce overfitting [

10]. The optimal learning rate was explored in a range from

to

to balance the learning speed, as the lower learning rate helps the model to learn stably but slowly and the higher learning rate helps the model to learn faster but less stably [

10]. The optimal subsample and feature sample for each tree were also explored with a range from 0.2 to 1.0. 0.2 means that the individual tree uses a randomly selected 20% of the training dataset or features, while 1.0 means that the individual tree uses the entire train dataset or features to grow the tree [

10]. Using a portion of the train dataset or features would run the model faster but be prone to high bias and using the entire train dataset or features would be slower to run and prone to overfitting [

10]. Minimum weight for child node was explored from a range from 1 to 10. The higher minimum weight makes it harder to further split the child node and leads to lower risk of overfitting, while the lower minimum weight makes it easier to further split the child node and leads to higher risk of overfitting [

10]. Lastly, the optimal gamma, alpha, and lambda were explored with a range from

to 1.0. The higher value for these parameters represents more regularization [

10].

Appendix A summarized final values for hyperparameters that

Optuna determined across the five random seeds.

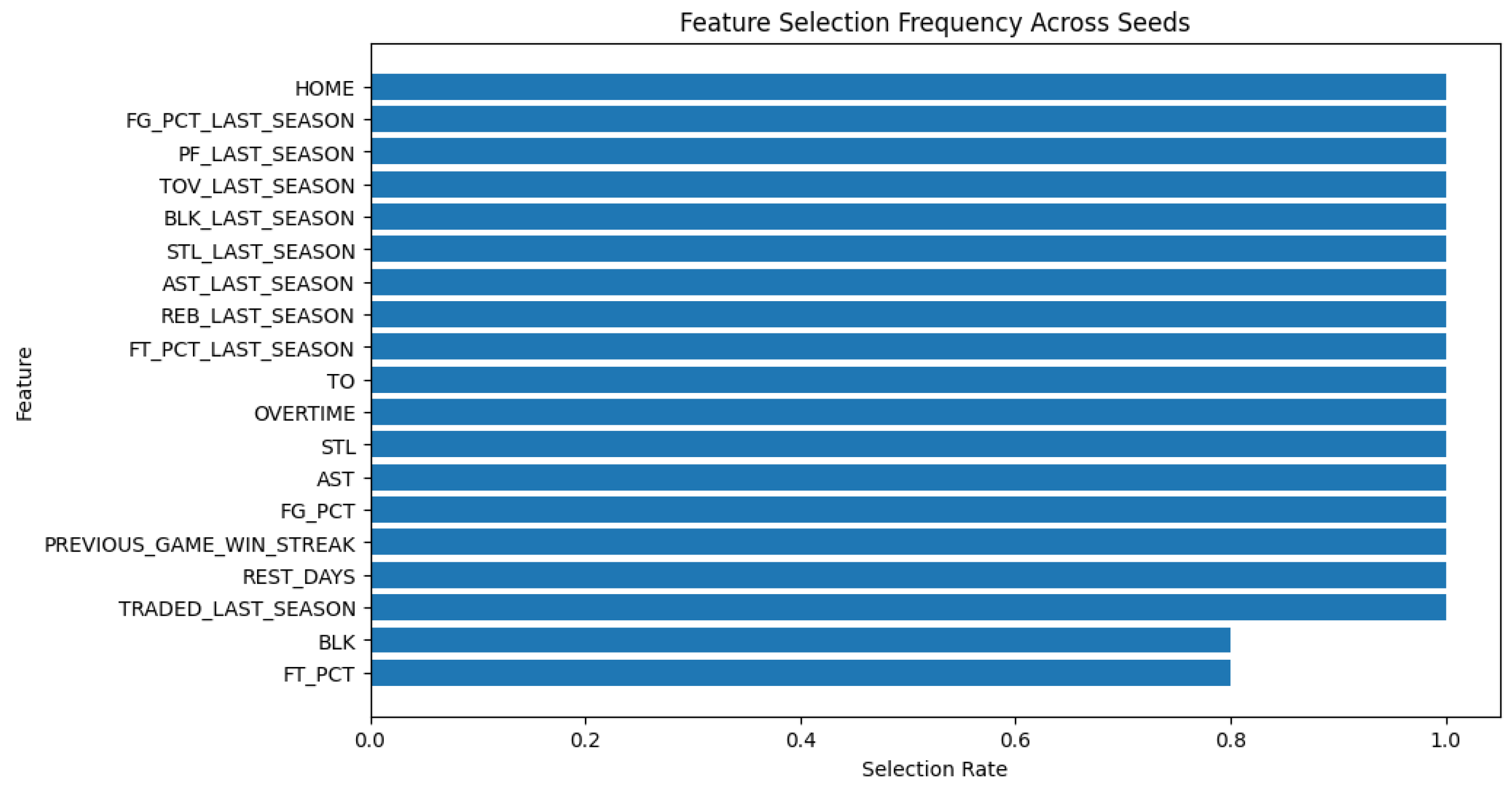

To select the most predictive and relevant features, the XGBoost model was trained with the best parameters selected through the Optuna study on the training dataset. Then, features were selected if their importance scores exceeded the average importance score of all the features. The maximum number of features was limited to 20 to improve model interpretability. The selected features were stored for later processes, including training, testing, and validating the model as well as stability analysis.

With the best-selected features, the Optuna study ran 20 trials again to find the best combination of hyperparameters. The parameters included learning rate, maximum depth, number of estimators, subsample ratio, column sampling per tree, minimum child weight, and regularization factors included gamma, alpha, and lambda. The scale_pos_weight parameter was set as 0.7 to maximize the F1 negative score. The goal of the optimization was to maximize the F1 negative score to balance positive and negative predictions.

In the final model training process, the train and validation sets were merged and filtered to keep only the best-selected features. The final XGBoost model was trained using the best hyperparameters from the Optuna study. Then, the final model was evaluated on the test set that the model had never seen.