Fine-Tuning and Prompt Engineering

As large language models (LLMs) have grown increasingly sophisticated [

1,

2], they show significant applications across diverse fields, materials preparation [

3,

4,

5], drug design [

6,

7], fundamental physics research [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], and engineering [

16,

17]. The unique capability of LLMs to generate detailed, contextually rich responses has made them valuable assets for domain-specific tasks [

18]. However, these benefits often depend on the fine-tuning of models to adapt them to particular fields, ensuring they deliver accurate and relevant responses [

19]. Fine-tuning is a process that tailors the model’s responses to specific requirements or terminologies within a domain, enhancing the model’s contextual understanding and response specificity [

20]. For example, a model fine-tuned in the medical field is better equipped to handle questions regarding diagnostic procedures[

21], whereas a model trained for financial applications might offer more accurate responses related to market trends and economic analysis [

22].

Despite the critical importance of fine-tuning, current fine-tuning practices face significant challenges, particularly regarding data acquisition and manual training [

23]. Fine-tuning typically requires large, domain-specific datasets, which are often costly and time-intensive to gather and annotate [

24]. These datasets must be meticulously curated to ensure data quality, consistency, and relevance [

25]. Additionally, manually training a model with these datasets is resource-intensive and demands substantial computational power and time investment [

26]. These requirements create a bottleneck, slowing down the deployment of specialized LLMs and limiting the frequency with which they can be updated or adapted to emerging domain knowledge [

27].

Prompt engineering has emerged as a promising alternative to traditional fine-tuning [

28]. Rather than modifying the model’s internal parameters with new datasets, prompt engineering involves crafting specific input phrases or "prompts" that guide the model’s responses within the desired context [

29]. Through prompts such as “You are an expert in biochemistry” or “Explain as a quantum mechanics researcher,” models can be steered toward generating responses that align more closely with domain-specific knowledge [

30]. This approach circumvents the need for extensive dataset training, offering a more flexible and cost-effective way to refine the model’s behavior on demand [

31]. Recent advances in prompt engineering indicate that well-crafted prompts can significantly enhance model output quality by leveraging the vast amount of knowledge embedded in LLMs [

32]. However, while prompt engineering can guide model responses, it does not replace the need for fine-tuning when deep, domain-specific knowledge is required [

33]. The challenge lies in whether prompt engineering could enable constrained, domain-specific prompts that autonomously guide the model through a self-training process [

34]. This approach could revolutionize the current paradigm by allowing models to develop expertise dynamically without extensive human intervention, unlocking a future where fine-tuning and prompt engineering coalesce into a seamless, self-training framework [

35].

Concept: Constrained Prompt-Driven Self-Training

Potential of Constrained Prompts to Improve Response Specificity and Relevance

Constrained prompts, or specific instructions that direct a model to respond within a defined domain, hold significant promise in enhancing the specificity and relevance of large language models’ (LLMs) outputs [

36]. A constrained prompt, such as “You are an expert in semiconductor materials,” provides the model with explicit domain context, guiding it to prioritize certain types of information while filtering out irrelevant data. This approach is particularly advantageous in specialized fields where accurate responses require a focused application of relevant knowledge. By narrowing the scope, constrained prompts can increase the likelihood of the model generating responses that meet the high standards expected in technical and scientific disciplines. The impact of constrained prompts extends beyond merely producing better-targeted responses; they can also facilitate a deeper interaction between the model and the prompt’s domain. When an LLM operates under a constrained prompt, it becomes more likely to utilize specialized terminology, reflect on specific methodologies, or draw upon more nuanced insights within the requested domain. For example, a constrained prompt in the field of neuroscience could lead the model to incorporate relevant neuroscientific theories, terminology, or experimental frameworks, which would otherwise be less accessible without the explicit direction. As LLMs continue to expand their knowledge bases through training on extensive datasets, the potential of constrained prompts to leverage this latent domain knowledge becomes even more impactful. Constrained prompts can effectively unlock this potential by targeting responses more precisely, leading to outputs that align better with professional standards and expectations. Despite this promise, constrained prompts do not fully substitute the need for fine-tuning. While they enhance response relevance, they do not modify the underlying model parameters. As such, the model’s inherent limitations, particularly regarding depth and complexity of understanding within a specialized field, remain unchanged. However, with further advancements, constrained prompts could serve as the foundation for a dynamic self-training framework, where the model not only generates contextually relevant responses but also learns and improves autonomously within the constrained domain.

Theoretical Workflow for Achieving Self-Training Through Constrained Prompts

In the envisioned framework of constrained prompt-driven self-training, large models would move beyond static responses to become dynamically adaptive, capable of learning autonomously in response to specified domain prompts. This process would begin with a user-input constrained prompt, such as “You are an expert in biomedical engineering,” which would then trigger a sequence of internal model operations aimed at locating, retrieving, and analyzing relevant data. Initially, the model would parse the prompt to identify the primary domain (e.g., biomedical engineering) and secondary topics within that domain that are relevant to the user’s query. This identification process would draw on the model’s internal knowledge base to set the context and scope for its subsequent operations. Following the initial context-setting phase, the model would autonomously connect to open-access databases or repositories containing domain-specific knowledge. For example, given a constrained prompt in biomedical engineering, the model might access resources like PubMed for research articles or engineering databases for technical data. The goal of this data retrieval stage would be to obtain high-quality, authoritative information that aligns with the user-specified constraints. Using these resources, the model would proceed to a self-training phase in which it could refine its internal parameters based on the newly acquired data. This process could involve machine learning techniques, such as embedding updates or incremental learning, to integrate relevant insights from the domain into the model’s neural network [

1]. Upon completing the data retrieval and self-training phase, the model would be equipped to generate responses that more closely align with the constrained prompt’s intent. This entire workflow would function in real-time, enabling the model to respond dynamically to a wide range of domain-specific questions.

Current Limitations: Inability of Existing Models to Self-Train Autonomously

While the concept of constrained prompt-driven self-training is theoretically sound, existing LLMs are currently unable to execute this process due to several technical limitations [

37]. First, today’s models lack the capability to autonomously retrieve data or access external databases in response to prompts [

38]. Most LLMs are designed to operate on pre-trained data without the ability to fetch or incorporate new information from online or offline databases dynamically [

1]. Consequently, they cannot update their parameters in real-time based on new domain-specific data, which is a fundamental requirement for self-training [

19]. Another significant limitation lies in the model architecture itself [

18]. Current LLMs are designed as static structures; they are unable to modify their internal parameters or neural weights outside of formal retraining cycles [

39]. This design is incompatible with the concept of real-time self-training, where the model would ideally update its understanding incrementally in response to constrained prompts [

25]. Although some research has been directed toward creating adaptive and modular neural networks, the technology is still in its early stages and not yet suitable for large-scale application within LLMs. Moreover, the computational demands of autonomous self-training are considerable [

40]. Achieving self-training would require real-time access to large volumes of domain-specific data and substantial processing power to integrate and update this information [

41]. This would significantly increase operational costs and potentially limit the accessibility of self-training models to well-funded institutions and enterprises. Additionally, without rigorous quality control, allowing a model to autonomously ingest data from external sources could lead to inaccuracies or biases in the model’s outputs, further complicating the development of reliable self-training frameworks.

Conceptual Framework and Illustrations

Flowchart of Self-Training Driven by Constrained Prompts

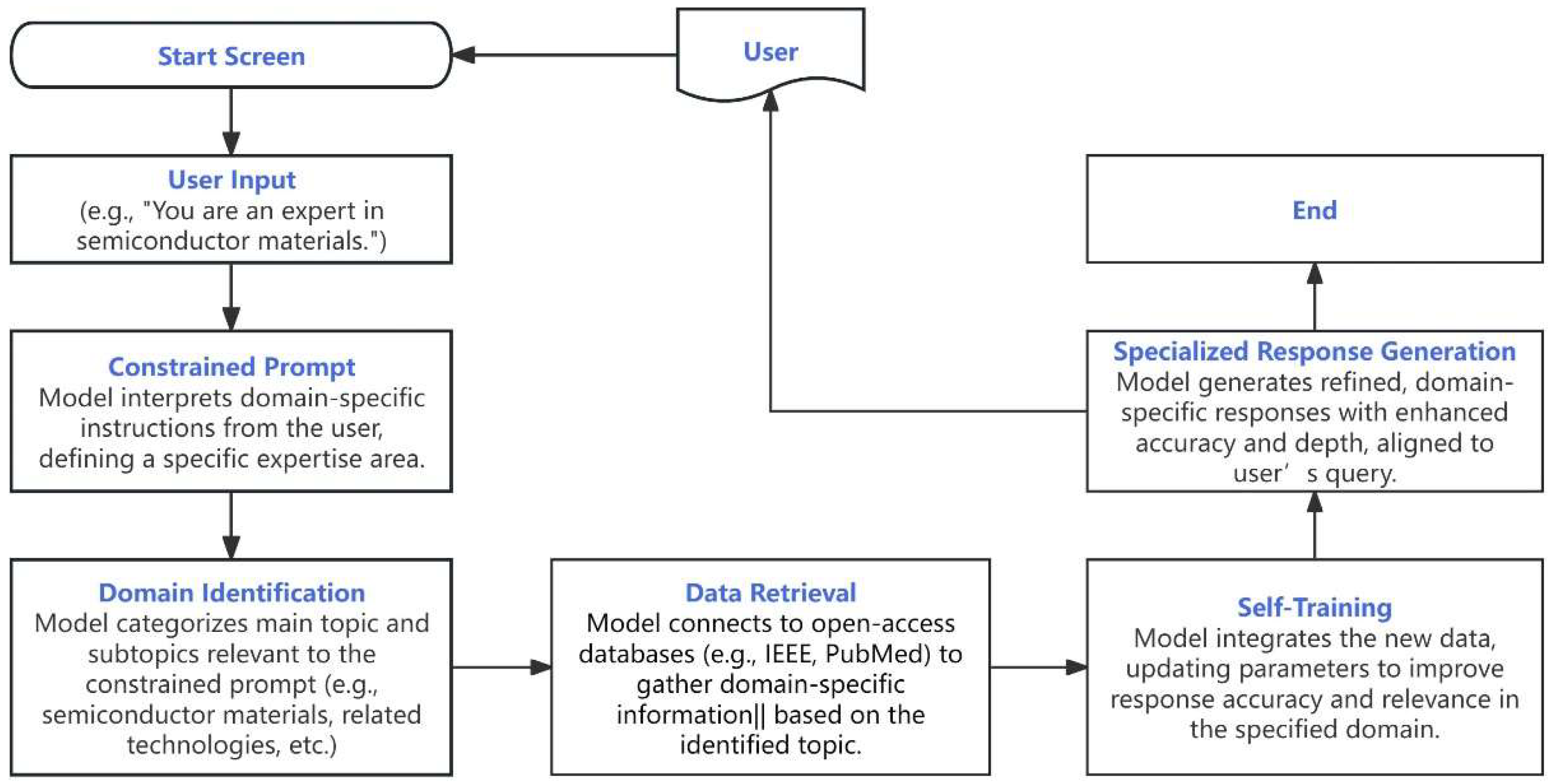

The flowchart for constrained prompt-driven self-training outlines a multi-step process that enables a large language model (LLM) to produce precise, contextually relevant responses within specified domains, driven by user-defined prompts. Here is a detailed breakdown of each step in the workflow:

The process begins with the initiation of a session where a user can input specific instructions, setting the stage for domain-specific guidance. This phase marks the start of a targeted interaction tailored to the user’s needs.

- 2.

User Input

The user provides a constrained prompt, such as “You are an expert in semiconductor materials.” This prompt defines the scope and expected expertise of the model’s response. By framing the model as a specialist in a specific area, the prompt sets a focused direction for subsequent steps, ensuring the response aligns with the domain’s standards and terminologies.

- 3.

Constrained Prompt Interpretation

The model interprets the constrained prompt, understanding the specific area of expertise required. This step involves processing the prompt to identify keywords that define the domain and subtopics, allowing the model to narrow its focus accordingly. For instance, with a prompt in semiconductor materials, the model would focus on technical aspects relevant to that field rather than general scientific information.

- 4.

Domain Identification

Once the constrained prompt is processed, the model categorizes the main topic and subtopics relevant to the user’s specified domain. This categorization refines the model’s understanding, enabling it to limit its attention to specific areas like materials science, semiconductor fabrication, or relevant advancements within the semiconductor industry. By isolating relevant themes, the model prepares itself to retrieve accurate, contextually appropriate data.

- 5.

Data Retrieval

In this phase, the model connects to open-access databases or knowledge repositories to gather authoritative information within the identified domain. For example, if the prompt pertains to medical sciences, the model might access PubMed, while an engineering prompt might lead it to IEEE Xplore. This automated data retrieval allows the model to gather up-to-date, high-quality information, forming the foundation for its self-training.

- 6.

Self-Training

After retrieving relevant data, the model enters the self-training phase, where it integrates the new information and refines its internal parameters. Through processes like embedding updates or incremental adjustments, the model adapts its neural weights to better reflect domain-specific knowledge. This phase is crucial, as it allows the model to learn autonomously from the newly gathered data, enhancing its ability to respond accurately and with specialized insight within the given field.

- 7.

Specialized Response Generation

With its parameters updated and domain knowledge enhanced, the model is now ready to generate responses that closely align with the constrained prompt. The response generation phase produces detailed, contextually accurate answers that use appropriate terminology, reference recent developments, and meet the professional standards expected in the domain. This step marks the culmination of the self-training process, where the model delivers output that is both specific and relevant.

- 8.

End

The process concludes after the model has generated its domain-specific response. At this point, the model is prepared to repeat the cycle if further input is provided, allowing for continuous, prompt-driven adaptation within the specified field.

This structured approach, starting from user input and progressing through data retrieval and self-training to specialized response generation, highlights the potential of combining constrained prompts with self-training to achieve adaptive, domain-focused responses. Each stage is designed to maximize the model’s accuracy and relevance within the chosen area of expertise, offering a flexible and powerful alternative to traditional fine-tuning.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of Self-Training Driven by Constrained Prompts in Large Language Models. This flowchart illustrates a theoretical framework for enabling self-training in large language models (LLMs) through the use of constrained prompts, which guide the model to respond within a specified domain. The process begins with "User Input," where a constrained prompt such as "You are an expert in semiconductor materials" sets a clear context and domain for the model. This leads to the "Constrained Prompt Interpretation" stage, where the model processes and interprets the prompt to identify key topics and subtopics relevant to the specified field. Following this, the "Domain Identification" phase further refines the model’s focus, categorizing the main topic and associated subtopics to ensure targeted responses. The next step, "Data Retrieval," involves the model autonomously accessing open-access databases, gathering relevant and high-quality information to enrich its knowledge base. In the "Self-Training" phase, the model integrates this newly acquired data, updating its parameters to enhance accuracy and specificity within the chosen domain. Finally, the model reaches the "Specialized Response Generation" stage, where it produces refined, domain-specific responses aligned with professional standards. This framework exemplifies the potential of combining constrained prompts and self-training to create adaptive, highly specialized LLMs.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of Self-Training Driven by Constrained Prompts in Large Language Models. This flowchart illustrates a theoretical framework for enabling self-training in large language models (LLMs) through the use of constrained prompts, which guide the model to respond within a specified domain. The process begins with "User Input," where a constrained prompt such as "You are an expert in semiconductor materials" sets a clear context and domain for the model. This leads to the "Constrained Prompt Interpretation" stage, where the model processes and interprets the prompt to identify key topics and subtopics relevant to the specified field. Following this, the "Domain Identification" phase further refines the model’s focus, categorizing the main topic and associated subtopics to ensure targeted responses. The next step, "Data Retrieval," involves the model autonomously accessing open-access databases, gathering relevant and high-quality information to enrich its knowledge base. In the "Self-Training" phase, the model integrates this newly acquired data, updating its parameters to enhance accuracy and specificity within the chosen domain. Finally, the model reaches the "Specialized Response Generation" stage, where it produces refined, domain-specific responses aligned with professional standards. This framework exemplifies the potential of combining constrained prompts and self-training to create adaptive, highly specialized LLMs.

Comparative Illustration: Response Differences with and Without Constrained Prompts

The following illustrates the comparison between responses generated with and without constrained prompts across multiple models, including Kimi, ERNIE Bot, Qwen and ChatGPT 4o. Three questions representing different fields, i.e., physics, biology and materials, are included. The three questions are: ‘How does the contact angle affect the spreading of droplets?’ in

Figure 2, ‘How to synthesize qRBG1/OsBZR5?’ in

Figure 3 and ‘How to synthesize 6, 5 chiral single-walled carbon nanotubes?’ in

Figure 4.

- (1)

Response without Constrained Prompt

When presented with a general question, a model without a constrained prompt can provide a detailed response. Sometimes, the detailed steps for biology and materials also could be given. However, the response is somewhat broad, sometimes overly generalized response. For example, when asked about “How to synthesize 6, 5 chiral single-walled carbon nanotubes?” the model may produce a general step and possible methods, without providing specific information such as materials, experimental conditions, etc. This is not very useful for using these models to directly guide experiments.

- (2)

Response with Constrained Prompt

Using a constrained prompt like “You are an expert in the field of carbon nanotube synthesis.” the model may narrow its focus to advancements in carbon nanotube synthesis, discussing recent methods synthesizing carbon nanotube. Although restrictive prompts were added, the response of the general models did not show significant optimization. The responses are still vague and do not provide detailed steps. As compared to the cases when there are no restrictive prompts, there is a slight improvement in the answer. However, compared to the fine tuned models, the response obtained is still unsatisfactory.

Figure 2.

The comparison of the question ‘How does the contact angle affect the spreading of droplets?’ with and without constrained prompt.

Figure 2.

The comparison of the question ‘How does the contact angle affect the spreading of droplets?’ with and without constrained prompt.

Figure 3.

The comparison of the question ‘How to synthesize qRBG1/OsBZR5?’ with and without constrained prompt.

Figure 3.

The comparison of the question ‘How to synthesize qRBG1/OsBZR5?’ with and without constrained prompt.

Figure 4.

The comparison of the question ‘How to synthesize 6, 5 chiral single-walled carbon nanotubes?’ with and without constrained prompt.

Figure 4.

The comparison of the question ‘How to synthesize 6, 5 chiral single-walled carbon nanotubes?’ with and without constrained prompt.

Discussion and Reflections on Fine-Tuning Approaches

Pros and Cons of Current Fine-Tuning Methods

Current fine-tuning methods for large language models (LLMs) involve retraining the model on domain-specific datasets to improve accuracy and relevance within particular fields. One of the primary advantages of this approach is the high level of precision it can offer in generating responses. By training on curated, domain-specific data, fine-tuned models can develop a detailed understanding of specialized terminology, context, and industry standards, making them well-suited for technical or academic applications. Additionally, fine-tuning allows for continuous improvements in the model’s performance by updating it with recent data, ensuring the model remains relevant and aligned with current advancements. However, traditional fine-tuning also has notable drawbacks. It is often a time-intensive and costly process, requiring large, high-quality datasets that are expensive to collect and annotate. The computational resources needed for fine-tuning are substantial, especially for large models, making it difficult for many organizations to undertake frequent updates. Furthermore, fine-tuning is generally a static process, meaning that any new training requires starting over from the last iteration, which limits flexibility. These factors collectively hinder the adaptability of models and increase the overall cost, posing a challenge for applications that require rapid updates or domain-specific customization.

Feasibility and Potential Impacts of Constrained Prompt-Driven Self-Training

The concept of constrained prompt-driven self-training offers a promising alternative to traditional fine-tuning, leveraging prompt engineering to guide the model’s responses while enabling it to autonomously learn from newly retrieved data. The feasibility of this approach hinges on advancements in model architecture and autonomous learning capabilities. Unlike traditional fine-tuning, which requires substantial human intervention, constrained prompt-driven self-training would allow models to dynamically adapt to domain-specific queries by retrieving relevant data from open-access databases and incrementally updating their internal parameters. The potential impact of this method is significant. By reducing reliance on pre-curated datasets, constrained prompt-driven self-training could lower costs associated with data acquisition and training. Furthermore, the ability to autonomously integrate new information on demand would make LLMs far more flexible, enabling them to stay current with the latest research and developments in their designated fields. This would be particularly beneficial in fast-evolving domains, such as medicine or technology, where up-to-date knowledge is essential. If fully realized, this approach could shift the paradigm of fine-tuning from a static, high-cost process to a dynamic, prompt-driven system, offering an efficient and adaptive solution for domain-specific model enhancement.

Advantages of Self-Training: Cost-Effectiveness, Increased Efficiency, and Enhanced Domain-Specificity

Self-training through constrained prompts has several distinct advantages over traditional fine-tuning, particularly in terms of cost-effectiveness, efficiency, and domain-specificity. By enabling models to autonomously gather and integrate relevant data, self-training reduces the need for manual dataset curation and annotation, lowering operational costs. Additionally, this approach circumvents the need for frequent retraining sessions, making it more efficient and allowing models to adapt quickly to new information without extensive downtime. Another significant advantage of self-training is the enhanced specificity it provides within specialized domains. By dynamically adjusting parameters based on real-time data retrieval, models can produce highly targeted responses that reflect the latest knowledge and terminology within a given field. This continuous adaptation process ensures that the model’s responses are not only accurate but also highly relevant to the user’s needs, providing a level of domain-specific precision that static fine-tuning methods struggle to achieve.

Challenges and Future Directions

Standards and Data Quality in Open Databases for Reliable Self-Training

One of the primary challenges in implementing constrained prompt-driven self-training lies in ensuring the quality and consistency of data retrieved from open-access databases. For self-training to be effective, the model must rely on high-quality, reliable information that aligns with the specific requirements of the constrained prompt. However, open-access databases often vary widely in terms of data accuracy, completeness, and structure. The model’s performance can be significantly affected by these inconsistencies, as inaccurate or outdated information may lead to flawed responses, especially in technical or specialized fields where precision is critical. Establishing standards for data quality in open databases is essential to support reliable self-training. This includes developing criteria for data verification, relevance, and timeliness. Collaborations between database providers, industry experts, and research institutions could help create guidelines and best practices for curating data specifically for LLM training and retrieval. Implementing automated data quality assessment tools, such as consistency checks and relevance scoring, could also enhance the model’s ability to filter and select the most pertinent information, ensuring that self-training leads to trustworthy and accurate responses.

Technical Challenges and the Need for Interdisciplinary Collaboration

The technical complexity of constrained prompt-driven self-training is another significant challenge. Enabling LLMs to autonomously retrieve, filter, and integrate data from external sources requires advancements in model architecture, data retrieval algorithms, and adaptive learning mechanisms. Current LLMs are typically static in design, making them ill-suited for real-time parameter adjustments and incremental learning based on new data inputs. Developing models that can self-tune dynamically will necessitate novel architectural innovations, such as modular or hybrid models that can independently process and integrate external data streams without compromising overall model stability or accuracy. Achieving these technical goals will require interdisciplinary collaboration across fields like machine learning, data science, and domain-specific expertise. For example, integrating domain knowledge into model architectures could help improve the relevance of data retrieval and self-training processes. Partnerships between AI researchers, data engineers, and domain experts will be crucial to addressing these challenges. Interdisciplinary teams can collectively design robust frameworks and test models across different domains, allowing for iterative improvements that balance self-training flexibility with precision.

Future Applications and Technological Outlook: Pathways to Targeted Domain Solutions

The successful implementation of constrained prompt-driven self-training could unlock a range of applications, especially in fields that require tailored, up-to-date knowledge, such as healthcare, finance, engineering, and law. For instance, in healthcare, a self-training model could adapt to the latest medical research, guidelines, and case studies, providing clinicians with timely and evidence-based insights. Similarly, in finance, models could adjust to real-time market data and emerging economic trends, enabling analysts to make informed decisions based on current data without waiting for formal retraining cycles. The technological outlook for constrained prompt-driven self-training is promising. By establishing reliable data pipelines, developing adaptive model architectures, and maintaining interdisciplinary collaboration, LLMs could evolve into powerful tools for specialized problem-solving across multiple sectors. Future research may focus on refining the balance between self-training adaptability and data accuracy, exploring methods such as reinforcement learning to optimize real-time data integration while maintaining model robustness. Furthermore, as AI governance and data ethics advance, ensuring transparency and accountability in self-training processes will be key to achieving trust in these models.

In conclusion, constrained prompt-driven self-training represents a transformative direction for LLM development. While challenges related to data quality, technical complexity, and interdisciplinary collaboration remain, addressing these obstacles could enable large language models to provide precise, domain-specific solutions with unparalleled efficiency and responsiveness, paving the way for a new era of specialized, adaptive AI applications.

Acknowledgments

We thanks Mr. Dan Li for the assistance in the response of ChatGPT 4o in USA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- T. B. Brown. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2005.14165.

- A. Radford. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. OpenAI 2018.

- S. Kim, Y. Jung and J. Schrier. Large language models for inorganic synthesis predictions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 19654–19659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. C. Ramos, C. J. Collison and A. D. White. A review of large language models and autonomous agents in chemistry. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.01603, 2024.

- J. Hu and Z. L. Wang. Crystallization morphology and self-assembly of polyacrylamide solutions during evaporation. arXiv preprint 2024, arXiv:2403.20191.

- P. Qiu, C. Wu, X. Zhang, et al. Towards building multilingual language model for medicine. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, R. A. Roberts, M. Lal-Nag, et al. Ai-based language models powering drug discovery and development. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 2593–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang and Y.-P. Zhao. Wetting and electrowetting on corrugated substrates. Phys. Fluids 2017, 29, 067101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, X. Wang, Q. Miao, et al. Spontaneous motion and rotation of acid droplets on the surface of a liquid metal. Langmuir 2021, 37, 4370–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Holmes, Z. Liu, L. Zhang, et al. Evaluating large language models on a highly-specialized topic, radiation oncology physics. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1219326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, X. Wang, Q. Miao, et al. Realization of self-rotating droplets based on liquid metal. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2001756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. -L. Wang and K. Lin. The multi-lobed rotation of droplets induced by interfacial reactions. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 021705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, E. Chen and Y. Zhao. The effect of surface anisotropy on contact angles and the characterization of elliptical cap droplets. Sci. China Technol. Sc. 2018, 61, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Hu, H. Zhao, Z. Xu, et al. The effect of substrate temperature on the dry zone generated by the vapor sink effect. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 067106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, K. Lin and Y. P. Zhao. The effect of sharp solid edges on the droplet wettability. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 552, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Aluga. Application of chatgpt in civil engineering. East African Journal of Engineering 2023, 6, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Hu and Z. L. Wang. Analysis of fluid flow in fractal microfluidic channels. arXiv preprint 2024, arXiv:2409.12845, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- J. Kenton, M. W. J. Kenton, M. W. Chang, K. Lee, et al. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding in Proceedings of naacL-HLT. 2.

- J. Howard and S. Ruder. Universal language model fine-tuning for text classification. arXiv preprint 2018, arXiv:1801.06146.

- S. Gururangan, A. S. Gururangan, A. Marasović, S. Swayamdipta, et al. Don’t stop pretraining: Adapt language models to domains and tasks. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2004.10964. [Google Scholar]

- P. Rajpurkar. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. arXiv preprint 2016, arXiv:1606.05250.

- U. Khandelwal, O. U. Khandelwal, O. Levy, D. Jurafsky, et al. Generalization through memorization: Nearest neighbor language models. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1911.00172. [Google Scholar]

- S. Ruder, M. E. S. Ruder, M. E. Peters, S. Swayamdipta, et al. Transfer learning in natural language processing in Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: Tutorials. 2019; pp. 15–18.

- M. Lewis. Bart: Denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.13461, 2019.

- Z. Dai. Transformer-xl: Attentive language models beyond a fixed-length context. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.02860, 2019.

- C. Raffel, N. Shazeer, A. Roberts, et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of machine learning research 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- C. Sun, X. C. Sun, X. Qiu, Y. Xu, et al. in Chinese computational linguistics: 18th China national conference, 194-206 (2019).

- L. Reynolds and K. McDonell. in Extended abstracts of the 2021 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 1-7 (2021).

- T. Schick and H. Schütze. It’s not just size that matters: Small language models are also few-shot learners. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2009.07118.

- B. Lester, R. B. Lester, R. Al-Rfou and N. Constant. The power of scale for parameter-efficient prompt tuning. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2104.08691. [Google Scholar]

- T. Shin, Y. T. Shin, Y. Razeghi, R. L. Logan IV, et al. Autoprompt: Eliciting knowledge from language models with automatically generated prompts. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2010.15980. [Google Scholar]

- J. Wei, X. Wang, D. Schuurmans, et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- T. Gao, A. T. Gao, A. Fisch and D. Chen. Making pre-trained language models better few-shot learners. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2012.15723. [Google Scholar]

- J. Wei, M. J. Wei, M. Bosma, V. Y. Zhao, et al. Finetuned language models are zero-shot learners. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2109.01652. [Google Scholar]

- R. Bommasani, D. A. R. Bommasani, D. A. Hudson, E. Adeli, et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2108.07258. [Google Scholar]

- R. T. McCoy. Right for the wrong reasons: Diagnosing syntactic heuristics in natural language inference. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1902.0100797.

- L. Ouyang, J. Wu, X. Jiang, et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- A. Radford, J. Wu, R. Child, et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, et al. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- E. Ganesh and A. McCallum. Energy and policy considerations for modern deep learning research in Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 3693–13696.

- D. Patterson, J. D. Patterson, J. Gonzalez, Q. Le, et al. Carbon emissions and large neural network training. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2104.10350. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).