1. Introduction

Public spaces are one of the key agents in advancing culture, arts, and education [

5]. In this context, rural public cultural spaces, as an important component of public space, not only bear the functions of promoting art and education but also play a pivotal role in driving the development of cultural tourism. Rural public cultural spaces constitute a systemic field jointly formed by local actors (rural residents), tangible spaces (or virtual spaces), activity domains, and institutional frameworks [

6], and they serve as critical material carriers for the protection of cultural heritage in rural areas.

In recent years, by leveraging characteristics such as publicity, cultural significance, local distinctiveness, and production, rural public cultural spaces have disseminated knowledge of cultural heritage preservation through public cultural communication channels. This has enhanced the local community’s awareness of cultural heritage protection, emerging as a new driving force for the development of the cultural tourism economy in the new era [

6]. However, with the accelerated pace of constructing rural public cultural spaces, multiple challenges have gradually emerged—such as a lack of distinctive cultural characteristics, diminished functionality, and inadequate development of virtual spaces [

7]. These issues have led to the fragmentation and erosion of outstanding traditional culture [

8] and the collapse of its spiritual order [

9], causing a loss of conventional craftsmanship and cultural knowledge, and posing severe challenges to the living transmission of cultural heritage [

8].

More specifically, the challenges in constructing rural public cultural spaces mainly stem from three aspects: inadequate excavation of indigenous traditional culture [

2], unreasonable planning and utilization [

3], and an imperfect mechanism for public participation in the construction process [

4]. As an indispensable component of rural residents’ daily lives and production activities, insufficient exploration of indigenous traditional culture weakens public cultural identity and a sense of belonging, leading to the loss of collective memory and exacerbating the attrition of cultural heritage custodians [

10]; unreasonable planning and utilization of cultural spaces fail to fully meet the diverse cultural needs of the populace, thereby reducing their efficacy [

11]; and an underdeveloped public participation mechanism diminishes the cultural subjectivity of residents, creating tension between a state-centric logic and localized, differentiated approaches [

12].

With the transformation of the cultural economic development model, the critical role of constructing rural public cultural spaces in cultural tourism has become increasingly prominent, drawing the attention of scholars worldwide. For example, G. Brunori and colleagues have placed culture at the forefront of rural economic development, arguing that establishing appropriate governance models and affirming the importance of regional elites are keys to effectively excavating and leveraging indigenous culture during rural development [

13]. J.Y. Do and his team, approaching the issue from a planning perspective, have investigated the construction of rural public cultural spaces, suggesting that the development of rural cultural welfare facilities and strategic spatial planning significantly impact the development of public spaces—especially in addressing the public’s demand for cultural tourism [

14]. In addition, regarding the construction of public participation mechanisms, L. Dilley and others, using the example of rural public cultural space development in South Korea, contend that adjusting the role of government, addressing the emotional needs of rural residents (as seen in Japanese rural areas), and reinforcing the role of non-profit organizations and experts in regional space construction are crucial [

15].

Compared to other nations, China’s vast rural expanses [

16] and deeply rooted traditional cultural foundations have led to more nuanced research on the issues surrounding the construction of rural public cultural spaces. Broadly speaking, Chen Bo and Ding Cheng have noted that current construction efforts in China face challenges such as uneven development, lack of distinctive cultural features, and weakened functionality [

7]. In addressing these issues, further analyses have been conducted by various scholars. For instance, Fang Yaming and Liu Yuanjing suggest that the insufficient intrinsic motivation behind rural public cultural space development is related to the loss of local cultural agency and a crisis in recognizing the value of traditional culture [

17]. Gao Chunfeng proposes corresponding solutions by arguing that refining the cultural characteristics of rural public cultural spaces requires being rooted in local traditions, inheriting and innovating rural cultural heritage, and unearthing unique narratives and cultural expressions centered on traditional values [

18]. Moreover, with regard to unreasonable planning and utilization, Yang Yongheng and Chen Jian emphasize that strengthening the service functions of rural public cultural spaces involves fully harnessing the agency of local residents and leveraging local cultural leaders as pivotal human resources [

19]. Additionally, Geng Da and colleagues, focusing on institutional adjustments, argue that during the construction of rural public cultural spaces in China, the government should recalibrate the interplay between state-centric and peasant-centric logics, nurture villagers’ cultural self-awareness, and enhance the intrinsic mechanisms of rural culture, thereby facilitating a fundamental shift from a government-led “cultural delivery” approach to one that “cultivates culture. [

11]”

Based on these research findings, this paper aims to further strengthen the construction of rural public cultural spaces in China by focusing on three key areas: excavating historical cultural connotations, adjusting planning and utilization, and perfecting public participation mechanisms. Using Moganshan as a case study, the paper explores new pathways for constructing rural public cultural spaces within the context of cultural tourism development in the new era. First, by employing a literature review, the historical development process of the Moganshan region is systematically delineated to identify core cultural elements from different periods. Second, through GIS spatial analysis, the visualization of the spatial distribution of cultural heritage in the Moganshan area is enhanced. The findings from these two methodologies will lay a solid historical and cultural foundation for the innovative construction of rural public cultural spaces in Moganshan. Finally, by utilizing questionnaire surveys, the study examines the impact of public participation mechanisms on the construction of rural public cultural spaces, thereby offering new perspectives for developing rural public cultural space construction.

2. Materials and Methods

Constructing material spaces based on local culture is an important strategy to avoid the ‘one village looking the same’ phenomenon in rural public cultural space development [

10]. Therefore, this study integrates historical research, GIS spatial analysis, and questionnaire surveys to delineate the historical and cultural connotations of the Moganshan region, analyze the spatial distribution characteristics of cultural heritage, and employs linear regression analysis on 300 survey responses from various stakeholders to investigate the genuine perspectives of the public regarding the construction of mechanisms for public participation in rural public cultural spaces.

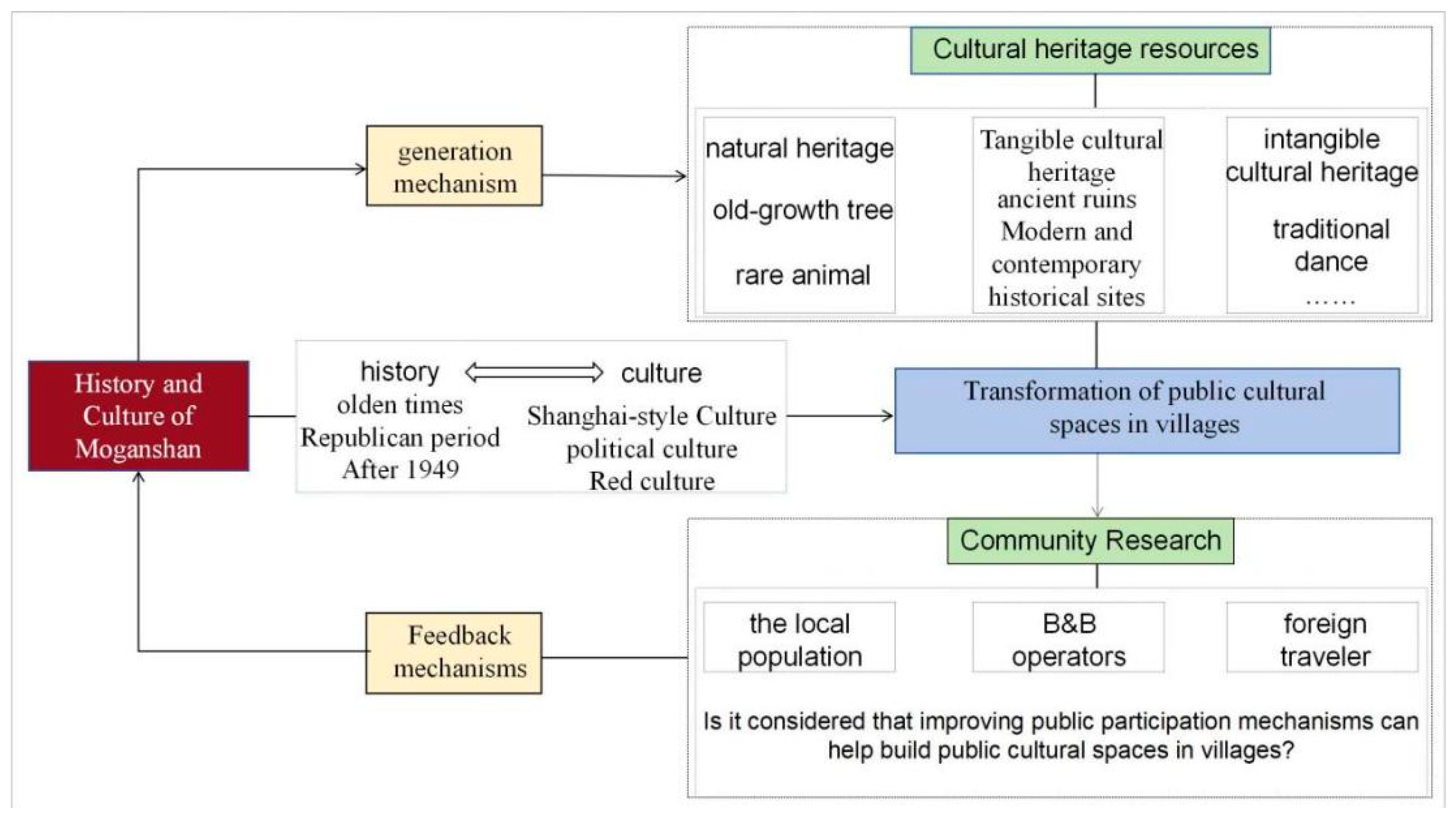

Figure 1.

Research Methods for Constructing Rural Public Cultural Spaces in the Moganshan Region.

Figure 1.

Research Methods for Constructing Rural Public Cultural Spaces in the Moganshan Region.

1. Literature Research Method

The core of the literature research method lies in the organization and analysis of historical materials [

20]. Specifically, this study’s literature research method comprises three key steps: First, collecting and organizing relevant historical materials from the Moganshan region to construct a comprehensive historical and cultural background; second, employing comparative analysis of the literature to explore the similarities and differences in cultural manifestations during various historical periods and to identify the fundamental causes behind these changes; and third, integrating and synthesizing the key information from the literature to extract the cultural characteristics of each historical period and to clarify their evolutionary trajectory.

Multiple types of historical sources are utilized to achieve this research objective. Official documents such as Zhejiang Tongzhi and Wukang County Annals record the basic geographical, historical, political, and cultural information of the Moganshan region. In contrast, local chronicles like Moganshan Annals and Republican-era newspapers such as Zhonghua (Shanghai) provide critical insights into the cultural landscape during specific historical periods.

In addition to material collection, this study further incorporates the theoretical framework of historical development stages to analyze the cultural evolution of the Moganshan region. The theory of historical development stages holds that social and cultural change is propelled by a series of phases, each characterized by unique cultural traits and historical contexts [

21]. Under this framework, the study utilizes comparative literature research to delve into the critical nodes and events of cultural transformation in the Moganshan region. This approach allows for dividing the region’s historical and cultural development into distinct periods and stages, thereby enabling an exploration of the trajectories of cultural change over time.

Finally, by integrating and synthesizing the literature, this research distils the core cultural characteristics of the Moganshan region at different historical stages. This portion of the study is crucial for understanding the historical depth and evolution of the region’s culture. The emergence of distinct cultural characteristics across different historical stages is attributed to the cumulative effect of historical events and the unique socio-historical contexts characterized by political reforms, social transformations, and shifts in cultural ideologies.

2. The ArcGIS Spatial Analysis Method

GIS, or Geographic Information System, is a system that, based on geospatial data and aided by computer technology, collects, manages, manipulates, simulates, analyzes, and displays spatially relevant data. It employs geographic modelling and analytical methods to provide various spatial and dynamic geographic information, forming geospatial information models for geographic research and data organization [

22].

This study employs the GIS method to construct a digital boundary for the Moganshan region and geocode the cultural heritage data within it, thereby establishing a spatial information model of cultural heritage distribution in Moganshan. The development of this model not only facilitates the revelation of the spatial distribution characteristics of cultural heritage in the region and supplies essential geographic information for cultural tourism development. Moreover, applying GIS technology enhances data analysis precision, enabling visitors to gain a comprehensive and intuitive understanding of the geographic features and evolutionary trends of Moganshan’s cultural heritage distribution.

Generating cultural heritage spatial distribution maps and kernel density maps using ArcGIS primarily involves four stages: data preparation, visualization processing, spatial analysis, and final mapping. First, during the data preparation phase, it is necessary to collect cultural heritage point data within the boundaries of Moganshan Town. This dataset includes detailed geographic coordinate information. In addition, administrative boundaries, transportation networks, and topographic data for Moganshan Town are obtained as background support to ensure standardized data formats and a unified coordinate system. Next, the collected data are loaded into ArcGIS, and through symbolization and classification techniques, tangible and intangible cultural heritage elements are differentiated and visually represented on the map. Supplementary map elements such as labels, scale bars, and north arrows are added to enhance readability. This process not only elucidates the geographic distribution pattern of cultural heritage but also establishes a solid foundation for subsequent spatial analysis.

In conducting kernel density analysis, the Kernel Density tool in ArcGIS is utilized to compute the spatial density distribution of cultural heritage points. The relevant calculation formula is as follows:

Where D(x, y) represents the kernel density value at location (x, y), that is, the pixel value of the kernel density distribution map; n denotes the total number of input cultural heritage points; w

i is the weight of the i-th point; h

2 represents the search radius, which corresponds to the spatial extent of Moganshan Town; d

i is the distance from position (x, y) to the i-th point; and K(d

i/h) is the kernel function used to calculate the weight at a given distance d

i. ArcGIS employs the quartic kernel function calculation formula, expressed as follows:

In this context, the standardized distance represents the distance ratio from point i to the analysis point relative to the search radius. The kernel function returns a value of zero when t > 1, meaning that points located beyond the search radius exert no influence on the density value at the given location. By setting an appropriate search radius and grid resolution, this method smooths the distribution of cultural heritage points, thereby producing a kernel density raster. With suitable colour rendering techniques, the resulting heat map delineates the spatial distribution pattern of cultural heritage in Moganshan Town. Furthermore, the underlying formation mechanisms can be effectively analyzed by integrating ancillary elements such as administrative boundaries and transportation networks. Finally, ensuring the map’s completeness and conformity to academic standards is essential during the mapping stage, with the final output exported in high-resolution format.

3. Questionnaire Survey Method

The questionnaire survey method is a quantitative research approach firmly rooted in a positivist epistemology. It involves systematically distributing standardized questionnaires to targeted participants, then carefully collecting, organizing, and statistically analyzing the returned data to derive empirical research findings [

23]. As an empirical social research tool, its very nature necessitates integrating random sampling procedures and robust statistical analyses [

24].

In this study, the questionnaire survey method is adopted to generate critical quantitative data that bridges the gap from qualitative insights to empirical validation, thereby supporting the refinement of public participation mechanisms in constructing rural public cultural spaces in the Moganshan region. On the one hand, the method must be underpinned by a well-defined theoretical framework; on the other, the degree to which abstract constructs are operationalized into concrete measures is paramount for ensuring the validity of the research. Moreover, because human subjects are the primary focus, their intrinsic characteristics inevitably influence the reliability and applicability of the survey instrument.

Framed by the context of cultural tourism development and guided by public participation theory, this study seeks to investigate the perceptions and expectations of different stakeholder groups regarding their involvement in the construction of rural cultural spaces in Moganshan. Accordingly, the questionnaire has been meticulously designed for three distinct groups—residents, tourists, and homestay operators—employing a stratified sampling strategy. Data collection is executed through online survey platforms and offline, in situ distribution, with 100 responses solicited from each group.

In evaluating the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha is employed as the primary reliability metric. At the same time, the Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) is used to assess the reliability of individual items. All survey data are rigorously subjected to tests of both reliability and validity. Once the sample collection is complete, linear regression analysis will be conducted to examine the predictive effects of various factors on the efficacy of the public participation mechanism. Furthermore, by comparing the differences among various stakeholder groups—specifically in terms of their cognitive levels, willingness to participate, and policy recommendations—the study reveals both the shared characteristics and the unique perspectives of each group regarding their involvement in the construction of rural cultural spaces in the Moganshan region. The questionnaire thus addresses the following primary research questions:

1. What are the residents’ perceptions of public participation in constructing rural public cultural spaces?

2. How do homestay operators view the development of rural cultural spaces in the Moganshan region?

3. What attitudes do non-local tourists hold toward constructing rural public cultural spaces in Moganshan?

4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

1. Construction of Recreational Cultural Spaces in the Moganshan Region

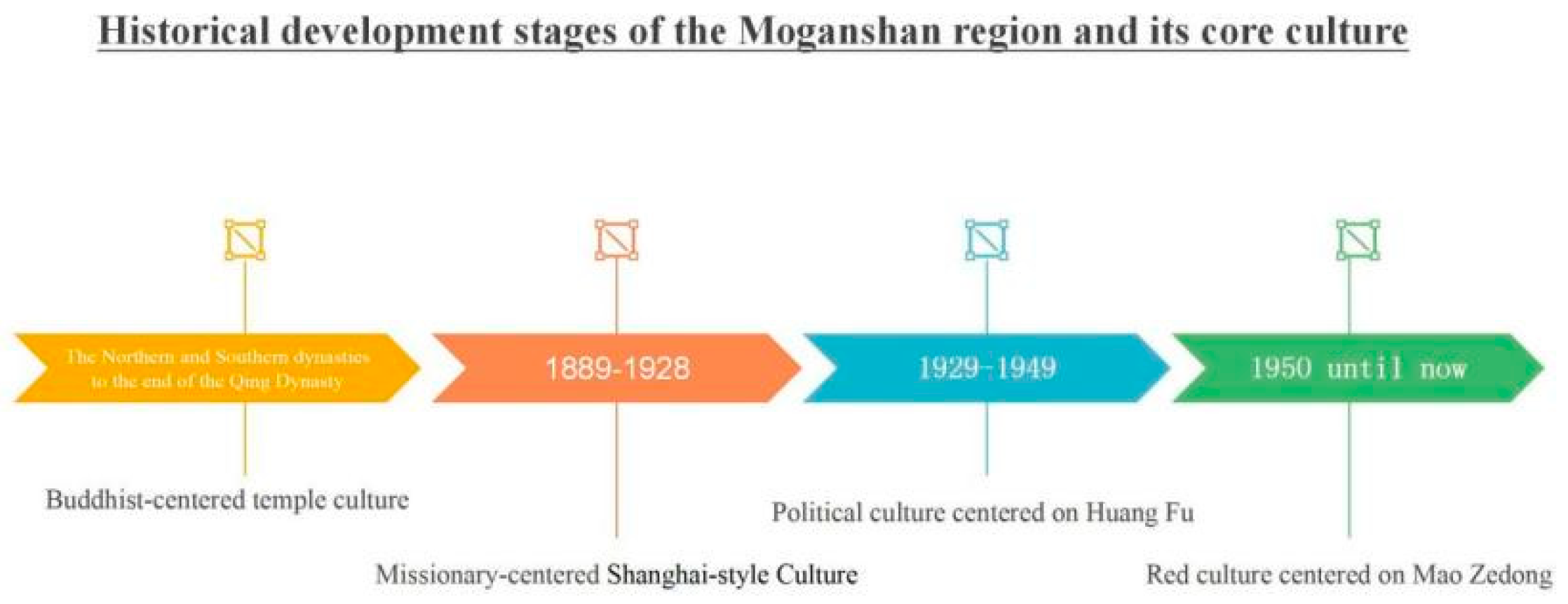

A literature analysis was conducted to examine the long-standing history and diverse cultural heritage of the Moganshan region. This rural culture—centered on village life—constitutes a vital component of community memory, embodying foundational perceptions of society, life, and history, and is a crucial guarantee for maintaining rural social order [

8]. The research reveals that Moganshan has historically been a confluence of cultures. The region’s unique cultural landscape is jointly shaped by Buddhist culture centered on temples, cosmopolitan culture influenced by missionaries, political culture epitomized by figures such as Huang Fu, and red culture centered on Mao Zedong. As an important material manifestation [

46], this cultural landscape typifies the characteristics of historical cultural geography [

47] by encapsulating the intertwined relationships among community, historical culture, and the natural environment. In doing so, it lays the foundation for highlighting the cultural distinctiveness of rural public cultural spaces. It promotes the development of rural cultural tourism, effectively compensating for the previously weak cultural identity in constructing such spaces. Consequently, this study, set against a rural cultural tourism development backdrop, proposes constructing recreational, cultural spaces by capitalizing on Moganshan’s extant cultural landscapes.

Recreational, cultural space is a novel concept that integrates the development of recreational spaces with cultural spaces, simultaneously fulfilling leisure, entertainment, and cultural dissemination functions. Although recreational cultural spaces are human-centered and built around recreational activities [

48]—much like conventional recreational spaces—they differ by primarily focusing on the exhibition of historical cultural landscapes and the provision of traditional cultural experiences. The goal is to maximize the regional cultural advantage during the development of cultural tourism. On one hand, these spaces are designed to provide residents with venues for accessing information about indigenous traditions, thereby strengthening regional cultural identity [

49]. On the other hand, they offer visitors, particularly during holidays, to closely observe and experience Moganshan’s native traditions. As a renowned leisure tourism destination within the Yangtze River Delta [

50], Moganshan boasts natural landscapes—such as bamboo forests, cloud vistas, ancient trees, and mountain springs—that, through thoughtful design and spatial planning, can accommodate various cultural activities. Dynamically, these spaces vividly display the region’s historical and cultural heritage, creating retreats and cultural experience venues removed from the urban clamor and catering to modern tourists’ dual demands for healthful rejuvenation and spiritual nourishment [

51]. Furthermore, recreational cultural spaces may serve as public platforms for non-governmental organizations (e.g., the Homestay Operators Association) to participate in local cultural space development, thereby becoming convergence points for regional ecological protection, historical cultural promotion, and economic development [

52].

It is also noteworthy that planning tourism routes is indispensable in constructing recreational and cultural spaces [

53]. Based on the region’s profound historical and cultural heritage, this study proposes a tourism route planning strategy centered on historical cultural promotion. Such planning, founded on cultural tourism, employs diversified historical themes to interlink multiple recreational and cultural spaces, thereby achieving the dual objectives of protecting historical and cultural landscapes and the natural environment [

54]. By connecting dispersed sites—such as ancient temples or Republican-era edifices—with eco-leisure routes like hiking trails and sightseeing paths, the interplay between linear and nodal spaces is reinforced, enhancing the cultural tourism experience. To this end, optimizing spatial layouts and dynamic route designs is essential. Specifically, historical cultural tourism routes should be planned with strategically located rest points and themed experiential circuits (for example, Chan tea and wellness experiences from the Song Dynasty, architectural tours of Republican cultural heritage, and red cultural mountain explorations) so that tourists can both recuperate physically in natural settings and receive spiritual nourishment through immersive cultural activities. This multidimensional experiential model is well suited to meet the diverse needs of visitors, thereby enhancing the overall competitiveness of rural areas within the context of cultural tourism development.

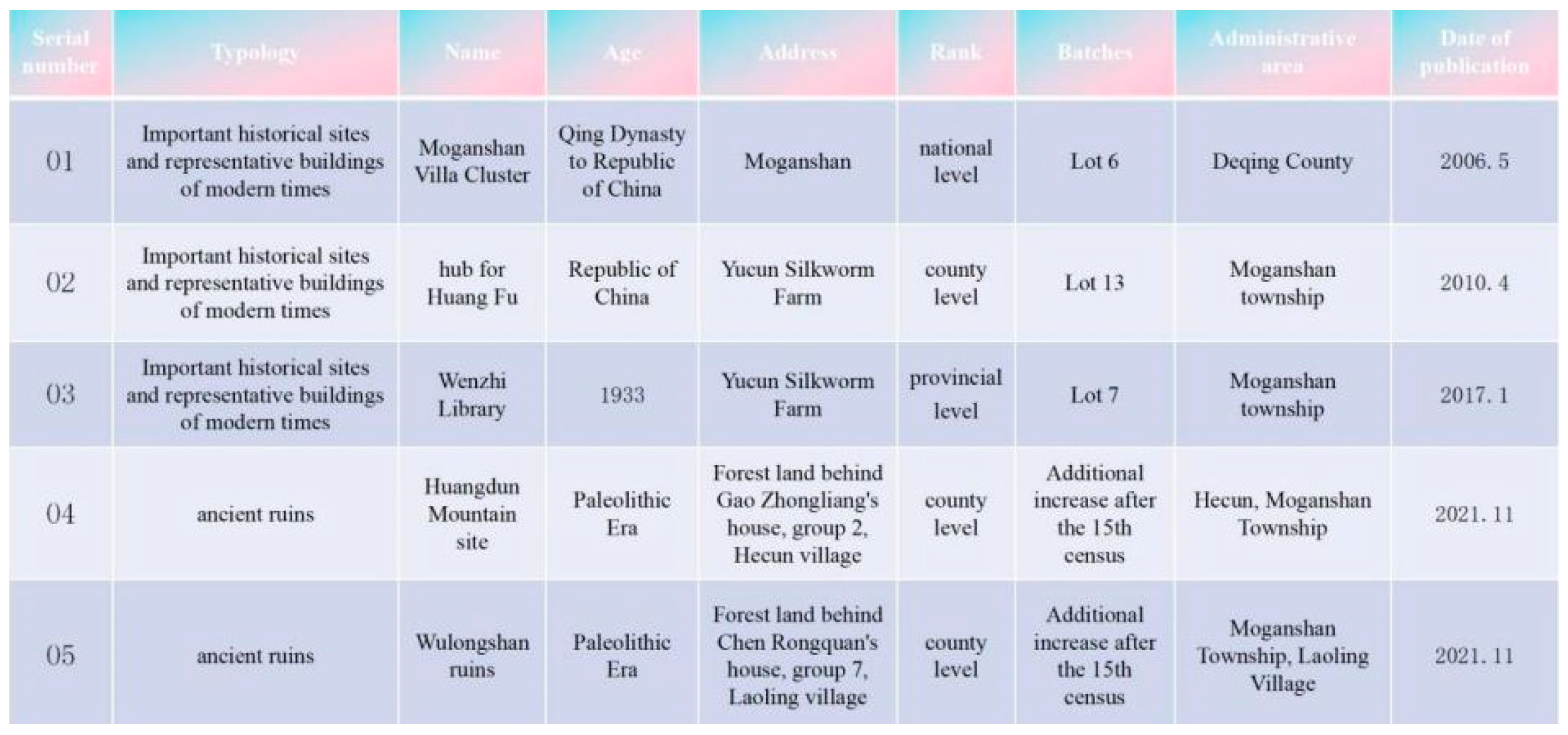

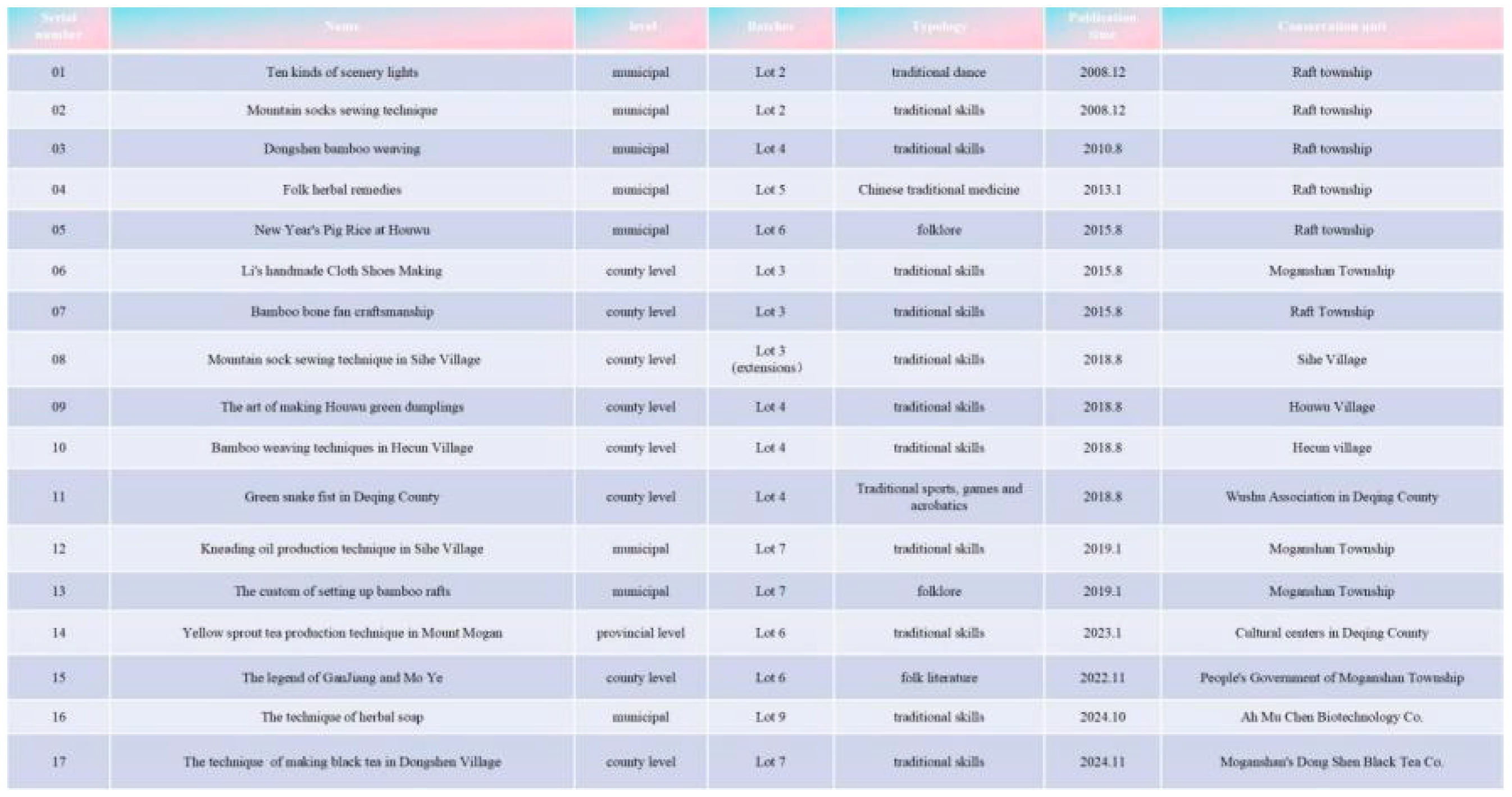

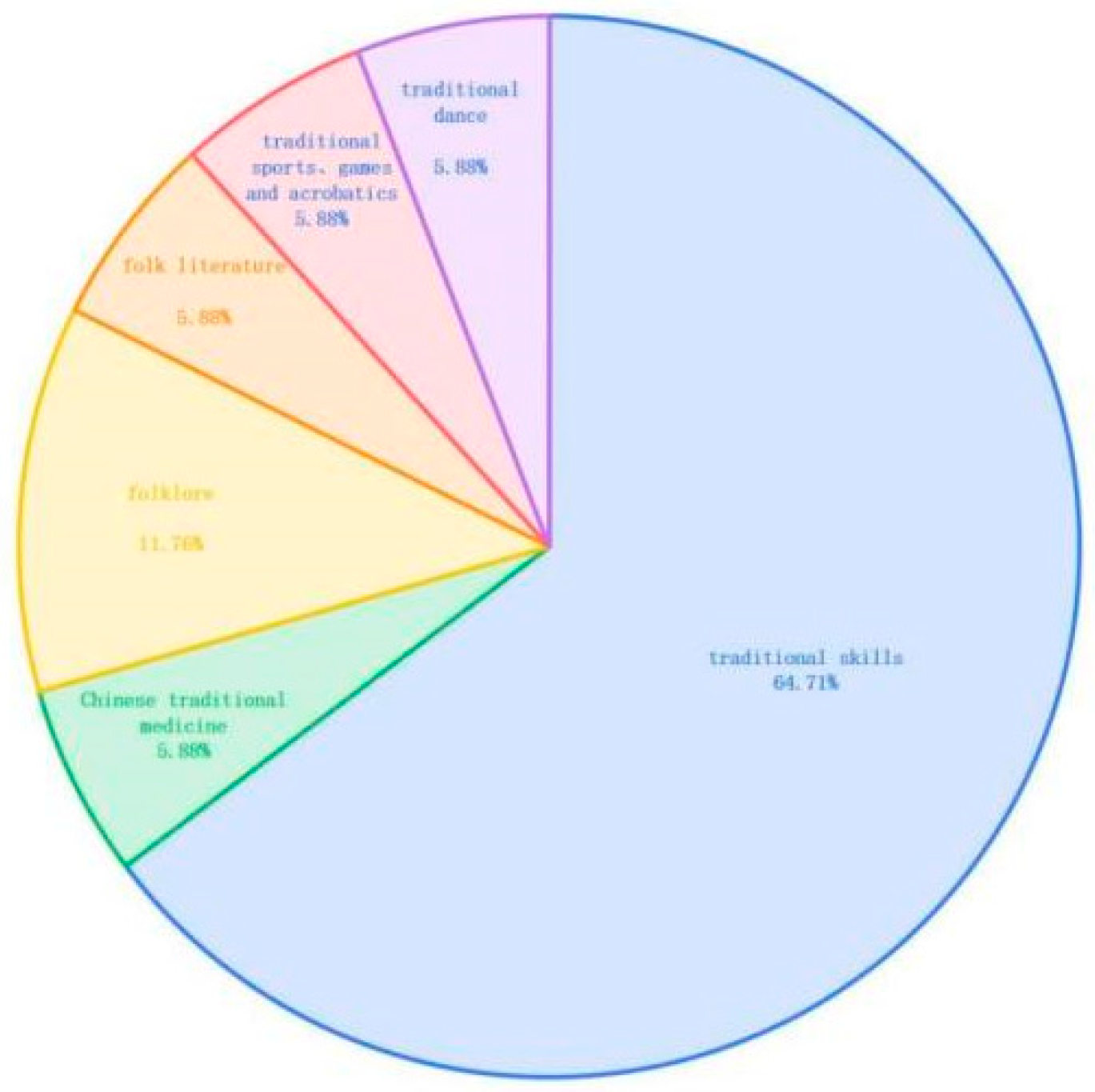

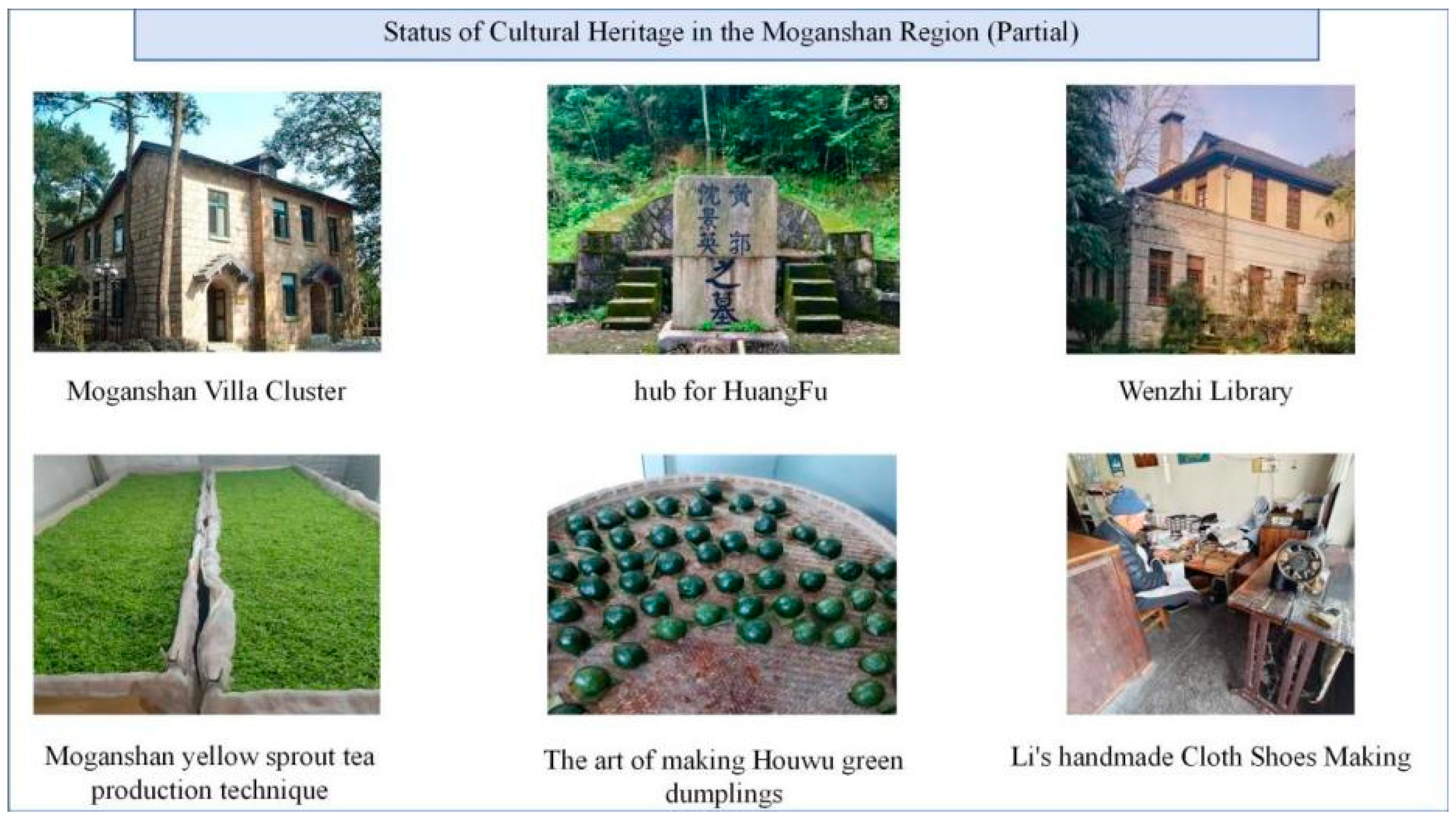

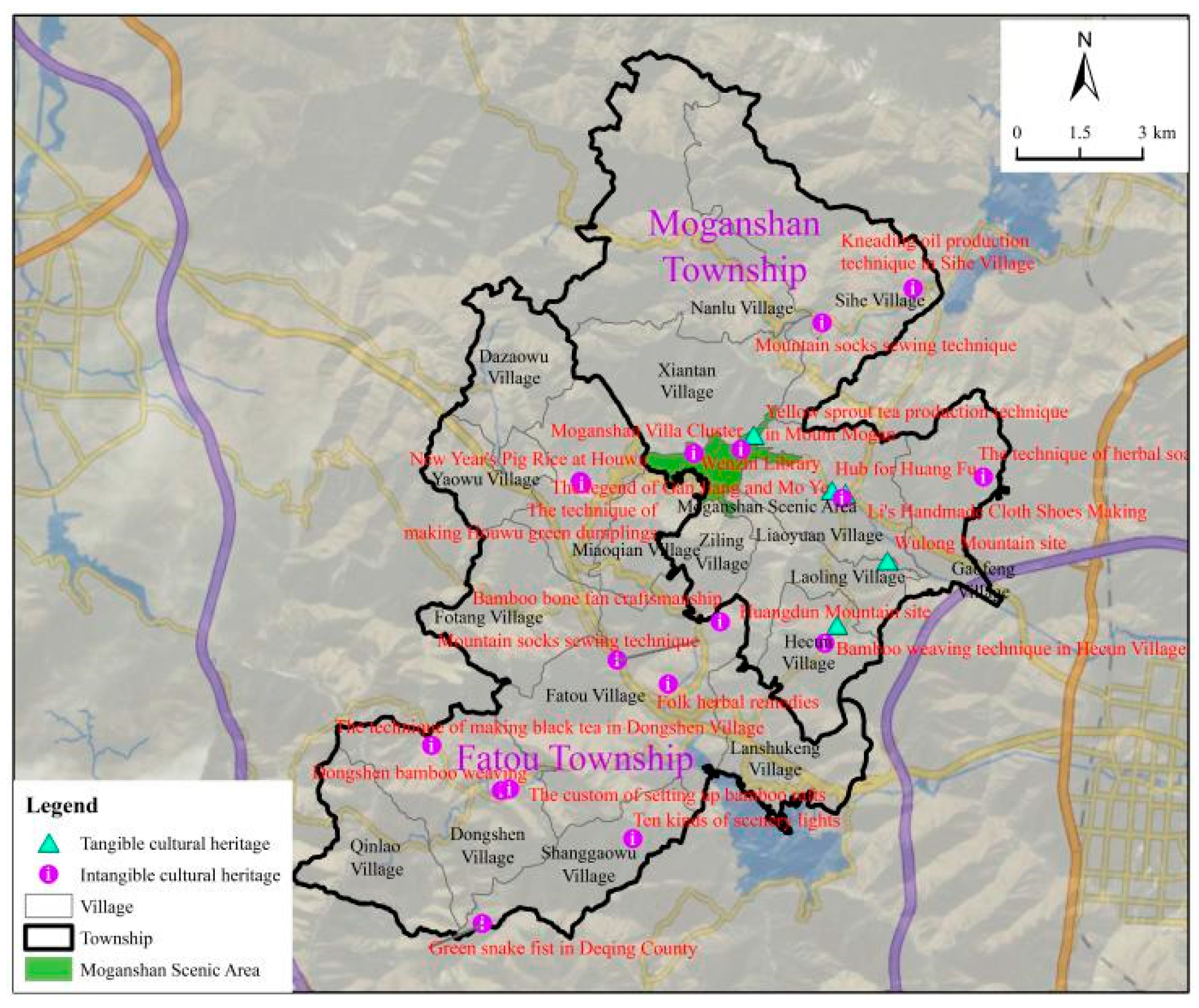

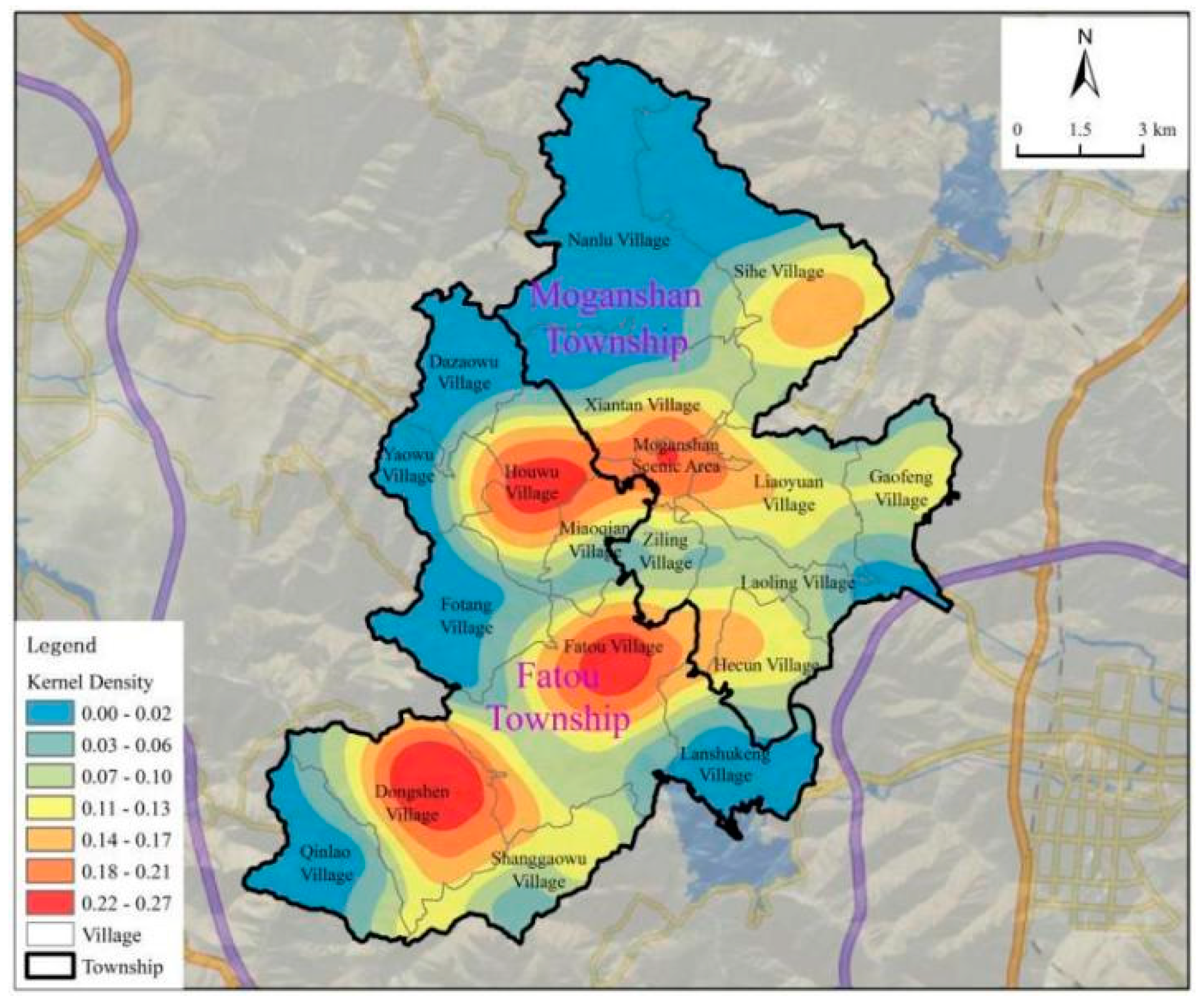

2. Construction of Cultural Heritage Spaces in the Moganshan Region

Using ArcGIS spatial analysis, this study investigates the diverse types of cultural heritage present in the Moganshan region. These cultural heritages are significant carriers of the region’s historical culture and cultural assets passed down through generations among rural communities [

55]. The findings indicate that the distribution of cultural heritage in Moganshan Town is primarily divided into two distinct cultural systems—exhibiting dense concentrations in the south and east and sparser distributions in the north and west. Further analysis reveals that these heritages predominantly cluster within residential village areas and radiate outward from central nodes along transportation routes, reflecting the unique lifestyles and values of Moganshan residents. Notably, intangible cultural heritage is particularly abundant and varied; its spatial distribution, characterized by transmission dynamics and an area-based pattern [

45], offers robust empirical support for optimizing the planning and utilization of rural cultural spaces and addressing the issue of inadequate spatial planning in rural public cultural space development. Accordingly, this study—situated within rural cultural tourism development and based on Moganshan’s existing cultural heritage spatial distribution—proposes constructing cultural heritage spaces, particularly emphasizing intangible cultural heritage workshops.

Intangible cultural heritage workshops represent a paradigmatic type within cultural heritage space construction [

16]. Since their inception, these workshops have been designed to link intangible cultural heritage projects with communities and markets, emphasizing the practical production of intangible cultural heritage products. As a breakthrough model for rural development, they aim to optimize regional planning for rural public cultural spaces by aligning with the growing tourist demand for “cultural experiences,” thereby fostering innovative developments in rural cultural space planning [

55] and promoting new paradigms in rural cultural tourism.

Establishing intangible cultural heritage workshops depends on two essential conditions: cultural substance and appropriate venues. Regarding cultural substance, the intangible heritage skills prevalent in Moganshan’s popular scenic areas are primarily traditional handicrafts—such as bamboo weaving, cloth shoe production, and herbal soap making. Additionally, lacquerware from surrounding towns is actively featured during the intangible cultural heritage festival. However, with the accelerated commercialization of these techniques, there is an increasing risk of excessive packaging and cultural homogenization. Moreover, due to insufficient depth and breadth in public participation, the cultural subjectivity of local communities is gradually eroded, reducing cultural experience to mere consumption and endangering the intergenerational transmission of intangible heritage. This situation underscores the critical importance of constructing dedicated cultural heritage spaces. As pivotal venues for the transmission of intangible cultural heritage, these workshops are well suited for offering training programs in traditional skills, organizing cultural experience courses and festive activities, and transforming intangible cultural heritage from static display to dynamic development via interactive exchanges, thereby bolstering local cultural promotion within the framework of cultural tourism [

56].

Furthermore, visitors’ innovative contributions can further invigorate the heritage’s vitality, positioning these workshops as incubators for cultural branding. In terms of spatial development, the construction of such workshops can be coordinated with local governmental initiatives by utilizing existing historical buildings in the Moganshan region, thus achieving centralized protection of cultural heritage. This approach revives traditional master-apprentice transmission systems within these spaces—preserving the authenticity of intangible cultural heritage—and facilitates their industrialization and commercial operation. It promotes cross-sector collaboration among heritage practitioners, designers, artists, and scholars, creating an innovative public platform for participatory cultural heritage protection. Additionally, as vehicles for the innovative development of rural public cultural spaces, intangible cultural heritage workshops can cooperate with non-governmental organizations such as the Homestay Operators Association to create distinctive cultural attractions, enable autonomous funding operations, and promote the “intangible cultural heritage + tourism” model, further enhancing the rationality of regional rural public cultural space planning.

3. Construction of Cultural Creative Spaces in the Moganshan Region

A questionnaire survey was employed to analyze the perspectives of residents, homestay operators, and visitors regarding the construction of rural public cultural spaces in the Moganshan region. Public cultural participation is critical to the development of these spaces. By considering public opinions and empowering citizens—incorporating their cultural choices and preferences as key indicators for cultural policy—pathways for optimizing rural public cultural space construction can be effectively refined [

57], thus advancing rural cultural tourism development. The survey results indicate that the construction of rural public cultural spaces enjoys broad support. Residents believe that public participation in these projects can effectively disseminate Indigenous traditional culture; homestay operators are convinced that such participation can significantly promote local cultural and economic development, and visitors express considerable interest in developing these spaces. Moreover, regardless of whether they are residents, homestay operators, or external visitors, respondents uniformly expressed their willingness to participate in constructing Moganshan’s rural public cultural spaces. This high level of public engagement provides a solid community foundation for refining participatory mechanisms in public cultural space construction, effectively addressing issues such as insufficient sustainability, order, and dynamism in cultural development [

58]. Consequently, this study—framed within rural cultural tourism development and leveraging the strong basis for public participation in Moganshan—introduces the concept of creative cultural spaces.

Cultural creative spaces were defined by UNESCO in 1988 as “venues that concentrate on folk and traditional cultural activities” [

59]. In her work On the Significance of Cultural Creative Spaces, Professor Jiang Lili of the National University of Singapore posits that cultural creative spaces constitute a form of cultural clustering that integrates specific cultural industries [

59]. Compared with traditional cultural spaces, cultural creative spaces serve as innovative platforms combining cultural creative industries with spatial development, fulfilling dual functions of cultural transmission and industrial agglomeration. Their objective is to organically integrate the three key themes of public participation—namely, the government, non-governmental organizations (e.g., the Homestay Operators Association), and the general public—thus addressing various institutional issues in constructing rural public cultural spaces.

The development of cultural creative spaces in Moganshan is still nascent. Existing spaces include a variety of forms, such as cultural plazas, Republican-era libraries, Wenzhi Cangshulou art exhibitions, Moganshan printmaking galleries, Yucun water streets, and floating stages. Additionally, projects under construction include modern cultural facilities such as art museums and planetariums. Renovated historical buildings retain a strong Republican cultural ambiance while incorporating traditional folk craft display areas that contrast with and complement contemporary art galleries, creating new avenues for cultural consumption within the regional cultural tourism framework. However, due to the current shortcomings in public participation mechanisms, the development of cultural creative spaces in Moganshan faces several challenges. First, insufficient exploration of indigenous traditional culture has led to a shallow integration of culture and space, with overall development trending toward homogenization and overlapping functions in certain areas—this may result in fragmented value systems and heterogeneous community groups, thereby hindering the construction of rural public cultural spaces [

60]. Strengthening public participation mechanisms is imperative; by harnessing the positive engagement of the public as the core of institutional development, it is possible to broadly collect traditional cultural information, enabling citizens to function both as participants and co-constructors in regional cultural tourism development [

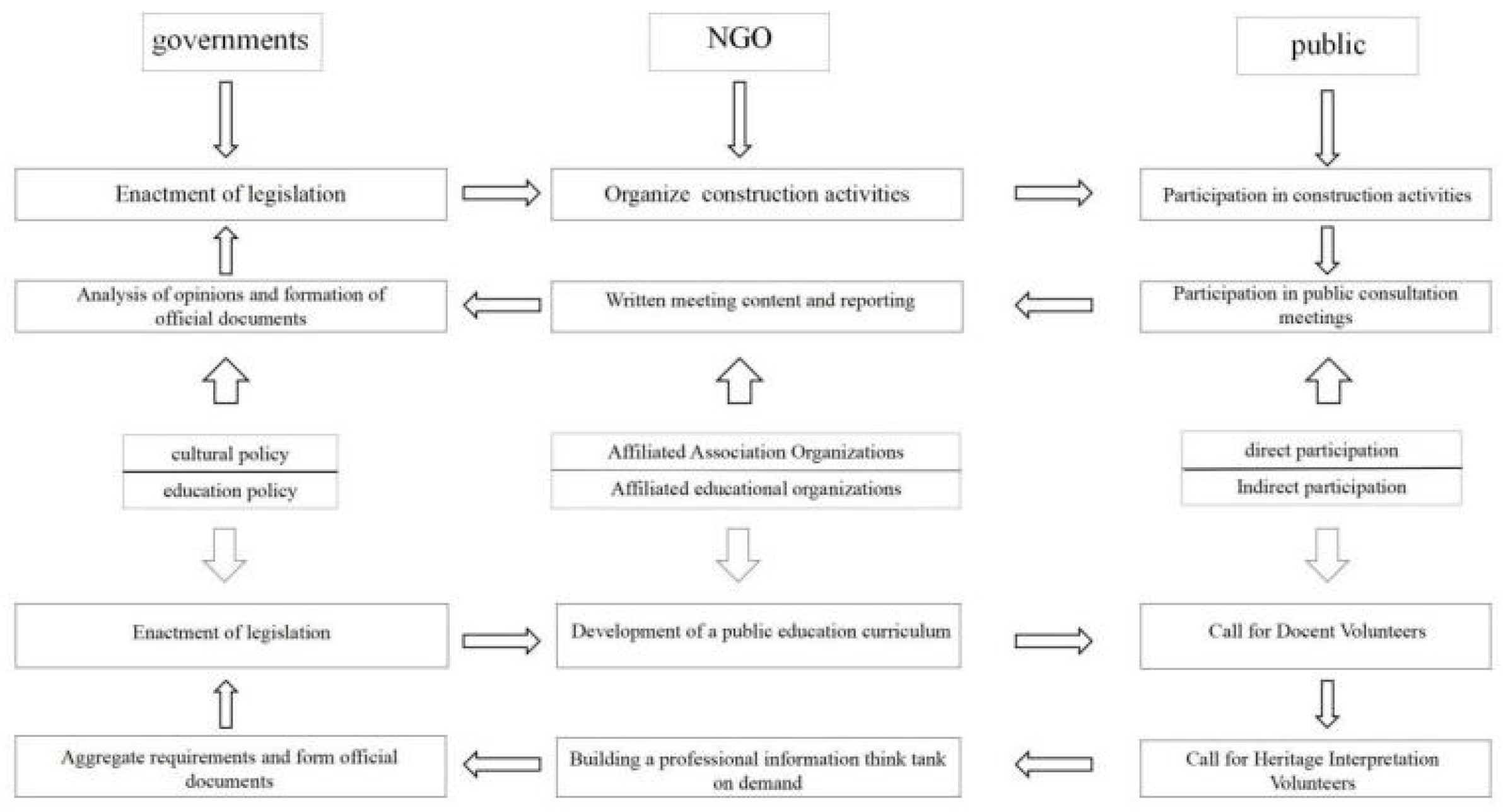

61]. Second, inadequate planning has resulted in insufficient interconnection among cultural creative spaces. For example, the secluded location of the Wenzhi Cangshulou, with its lack of clear signage along tour routes, has led to low visitor numbers. At the same time, the spatial remoteness between the outdoor stage and the water stage at Yucun Plaza hinders effective interaction. In order to address this issue, government authorities must provide improved management mechanisms and timely update relevant cultural policies to the evolving dynamics of regional cultural tourism. Finally, as the primary drivers of cultural creative space commercial development, non-governmental organizations such as homestay associations are expected to serve as vital communication bridges between the government and the public. On the one hand, these organizations—operating as government-appointed working groups—can be commissioned to construct cultural creative spaces and, during the process of space development and cultural product design, collect effective public cultural inputs, thereby broadening the scope of public participation in rural public cultural space construction and allocating part of the generated revenue to local villagers. This approach realizes the goals of community co-construction and shared benefits under the framework of cultural tourism development, fostering a synergistic environment for cultural tourism and economic progress alongside residents. On the other hand, as intermediaries between the public and governmental bodies, these organizations can organize activities and experiential courses centered on cultural creative product design, serving as think tanks that transform public opinions into actionable policy inputs for further planning of cultural creative spaces that align with regional cultural tourism development (the specific process is illustrated in

Figure 9).