1. Introduction

Dental anxiety (DA) is an emotion similar to fear but diffuse, anticipatory, and non-specific, manifested in the dental office. It is essential to differentiate between dental fear, dental phobia, and dental anxiety, which are three different ways of perceiving dental treatment and lead to three different types of reactions to this medical intervention [

1]. Dental fear is a specific fear reaction toward a particular object or clearly defined situation within the context of dental treatment [

2]. The distinction between dental anxiety and dental fear is difficult to make [

1,

2]. Dental phobia goes beyond fear or anxiety, leading to an avoidance behavior toward treatment, which the patient perceives as a disproportionately large threat compared to the actual situation [

3].

A systematic review with meta-analysis [

4] found that the overall estimated prevalence of DA was 23.9%, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 20.4% to 27.3%. When broken down by age group, the pooled prevalence was highest among preschool-aged children at 36.5% (95% CI: 23.8–49.2), followed by school-aged children at 25.8% (95% CI: 19.5–32.1), and adolescents at 13.3% (95% CI: 9.5–17.0). A higher incidence of DA was observed in preschoolers and school-aged children with a history of dental caries and in adolescent girls.

Another systematic review [

5] indicated that approximately 30% of children aged 2 to 6 years exhibited dental fear and anxiety, with the confidence interval ranging from 25% to 36%. The likelihood of experiencing DA was significantly greater in children who had never visited a dentist before (odds ratio: 1.37; 95% CI: 1.18–1.59) and in those who had a history of dental caries (odds ratio: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.09–1.27), compared to children who had previous dental visits or were free of caries.

Baier et al. [

6] stated that 20% of children suffer from dental anxiety, and 21% display negative behavior during treatments. Children with negative, uncooperative behavior tend to have higher levels of dental anxiety, and those who suffer from dental anxiety exhibit negative behavior. Klingberg and Broberg [

7] found that dental anxiety affects 10% of children and adolescents. This negative emotion is prevalent among children, ranging from 5.7% to 19.5%, due to differences in the studied populations and environments. Dental anxiety predominantly affects females and younger children.

Understanding the sources of dental anxiety helps to develop methods or strategies to reduce its intensity. Patients’ phobias are often related to the use of injections and needles (

trypanophobia) [

8]

, to pain [

9], to the sounds made by dental drills, and to the use of handpieces and instruments [

10]. Sometimes, even the smell of dental debris can trigger anxiety [

10]. Patients may have a fear of choking (

pseudo dysphagia) or swallowing small objects handled by the dentist during treatment [

3,

10].

Fear of pain causes experiences in the dental office to be perceived more intensely. Previous painful and unpleasant experiences in the dental setting, or traumatic events and feelings shared by others, influence patients. Researchers have shown that even

scaling and tooth brushing can be strongly associated with the perception of pain [

11]; it is the

anticipation of pain during these procedures, rather than the actual pain itself, that increases patients’ anxiety levels [

12]. A systematic review found a

positive correlation between levels of dental anxiety and fear of dental pain [

13].

Dental anxiety is a common issue in pediatric practice, modulated by various psychological and physiological factors. One of the most significant contributors is temperament, a set of stable, inherited characteristics manifesting early in life and influencing individual responses to stress [

14]. As a modulator of emotional reactivity, temperament plays a key role in how children adapt to fearful or unfamiliar experiences, such as those encountered in the dental office.

Children with impulsive and highly active temperaments are more prone to treatment refusal. These children may become agitated and exhibit negative emotional responses before the clinical encounter begins. In contrast, dental anxiety is often higher in shy children, who may internalize their fear [

14,

15]. Consequently, the pediatric dentist or orthodontist must assess each patient’s capacity for cooperation and communication before initiating treatment, as these factors are essential to performing clinical procedures [

16].

Establishing doctor-patient communication is often compromised when anxiety interferes with the child's ability to build trust with the practitioner [

17]. This interference may result in exaggerated emotional responses, delay or interruption of procedures, and treatment resistance. The anticipation of pain or trauma is typically the root cause of dental anxiety [

18], which in turn amplifies the perception of pain during treatment, creating a vicious cycle that has to be interrupted through appropriate intervention [

19].

The dentist and patient enter this interaction from inherently different positions within a shared stress-laden context: the doctor bears professional responsibility and faces clinical challenges, and the patient is overwhelmed by uncertainty and fear [

20]. A successful therapeutic alliance depends on mutual adjustment, facilitated by communication and an environment designed for minimizing stress [

19,

20]. For this reason, children should not wait too long before treatment begins, as prolonged anticipation exacerbates anxiety [

21]. Psychologically vulnerable cases should ideally be scheduled separately to avoid transmitting distress to other patients [

22].

Creating a welcoming environment in pediatric dental offices may influence children's emotional responses. Dental units shaped like animals or cartoon characters, colorful gowns (as opposed to white ones commonly associated with discomfort), and concealing anesthetic injections from the patient are all strategies that reduce anticipatory fear [

23,

24,

25]. Observing the child’s facial expressions and body language enables the dentist to infer their psychological profile and adapt their approach accordingly. Honest communication is crucial—surprise interventions have been reported to erode trust and intensify fear. Empathy may support building rapport and fostering cooperation [

26,

27].

Anxiety is often a transient emotional state, reflecting a person's perception of their ability to cope with a perceived threat [

27]. Its intensity can vary based on individual constitution, health history, fatigue, mood, and even family environment—whether overly permissive or excessively perfectionistic. While anxiety may arise from past negative experiences, it can also be rooted in temperament, presenting a complex interplay of innate and acquired influences.

Children can display a range of coping behaviors in the dental setting. Some are mildly anxious, remain cooperative, and employ emotion-focused strategies to manage their fears [

28]. Others exhibit guarded behavior, rely on problem-solving solutions, and may present heightened physical reactivity and exaggerated emotional responses that are difficult to modulate [

29].

Physiologically, anxiety activates the autonomic nervous system, particularly the sympathetic branch, resulting in measurable systemic changes. In the respiratory system, this may include hyperventilation, respiratory alkalosis, dyspnea, or sensations of choking or suffocation [

30,

31,

32]. Cardiovascular responses such as elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure and increased peripheral pulse are commonly associated with states of heightened anxiety [

33]. These parameters may serve as objective indicators of physiological arousal and are often used in observational studies to explore associations with emotional states or behavioral strategies, including relaxation techniques [

34].

Normal blood pressure (BP) values vary by age, sex, and height percentile.

Table 1 shows average systolic and diastolic values, which are reasonable for children and adolescents [

35]:

Heart rate (HR) values for children and adolescents, according to Kliegman et al. [

35], are illustrated in

Table 2:

Individual clinical assessment considers additional factors (e.g., height, physical fitness, stress, medication). These values are meant as reference averages—not strict diagnostic cutoffs.

An exception that still falls within the normal range is in athletic adolescents, who may have resting heart rates as low as 40–50 beats per minute. Heart rate increases in situations of anxiety, elevated catecholamine levels, or increased thyroid hormone levels [

35].

The values described are for a state of rest. During physical exertion or stress, heart rate may rise to the upper limit of the normal range for that age.

Over the past decade, non-pharmacological interventions for managing dental anxiety in both children and adults have been getting a significant appraisal. Relaxation techniques have emerged as safe, low-cost alternatives to anxiolytic medications like benzodiazepines, which carry potential side effects [

36]. The clinicians have to be responsible and minimize patient anxiety through the least invasive methods available.

In this study, we employed two techniques: the Breathing Control Technique (BC) [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]and Jacobson’s Progressive Muscle Relaxation (JPM) [

37,

38]. We selected these methods for their simplicity, utility, and accessibility.

The Breathing Control Technique is particularly beneficial during episodes of panic or acute anxiety [

38,

39]. Its primary goal is to relax the body and restore physiological parameters to baseline levels by rebalancing autonomic activity [

38]. It interrupts the cycle of pulmonary hyperventilation and the resulting drop in blood CO₂ that can trigger panic symptoms [

38,

39,

40].

The patient is comfortably seated with full body support, allowing for optimal relaxation of the muscles. The dentist gently guides the child to inhale slowly through the nose over three to four seconds and then exhale calmly over four seconds, either through the nose, mouth, or both, depending on what feels most natural. Breathing should be diaphragmatic to encourage oxygen-carbon dioxide exchange and reduce sympathetic nervous system activity [

40,

42]. This practice, typically lasting between five and eight minutes, helps lower physiological markers of anxiety and improves cooperation. Supporting the technique with a calm voice and, optionally, soft background music enhances its soothing effect [

39]. The effects of controlled breathing in reducing dental anxiety in children have clinical evidence. A study by Peretz and Gluck [

41] demonstrated that structured breathing techniques significantly reduced anxiety levels in pediatric patients during dental treatment, suggesting this method is an accessible and efficient behavior management strategy in clinical practice [

42].

Jacobson’s Progressive Muscle Relaxation, developed by Edmund Jacobson in the early 20

th century, involves systematically tensing and relaxing different muscle groups to promote deep physical and psychological relaxation [

3]. This method requires individuals to intentionally tense specific muscle groups for 6-10 seconds, followed by a gradual conscious release of that tension for 15-20 seconds. The technique is repeated in cycles, helping the patient to be aware of the contrast between muscular tension and relaxation, eventually leading to a full-body calming effect. When learned, JPM takes approximately 15 minutes and can have a profound result because it alleviates muscular tension and reduces anxiety-induced physiological responses (

Appendix A) [

3].

JPM works through both “top-down” and “bottom-up” neurological mechanisms. The “top-down” aspect involves the brain’s higher processing centers—such as the cerebral cortex—which consciously initiate the muscle contractions and subsequent relaxation [

37,

38]. In contrast, the “bottom-up” process begins with sensory feedback from the muscles, which travels through the spinal cord and brainstem, stimulating calming responses in the central nervous system [

36]. This dual mechanism helps induce rapid and noticeable relief from stress and tension.

Both techniques are non-invasive, practical, and applicable in a pediatric dental setting, contributing to better patient cooperation and easier dental care.

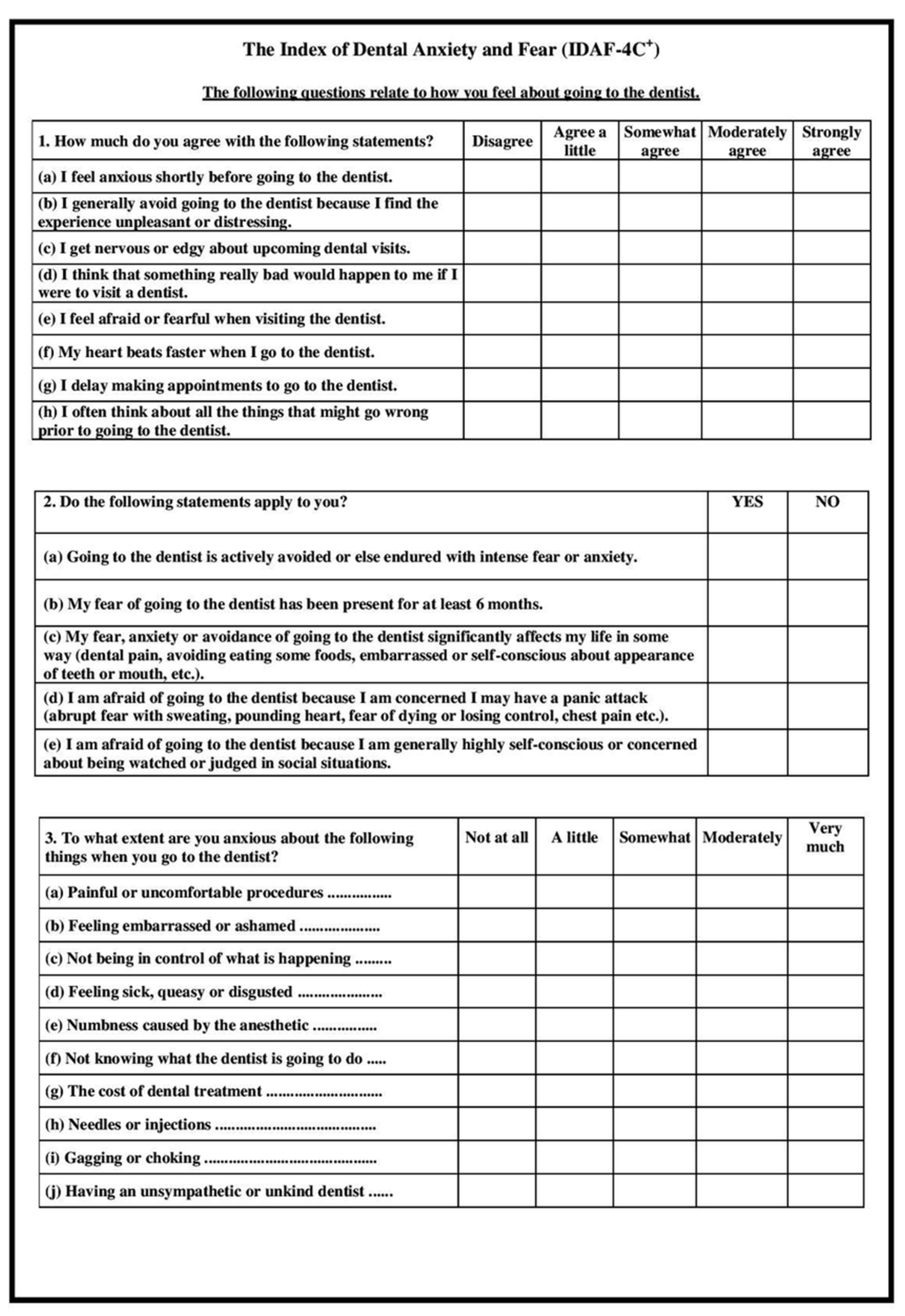

The IDAF-4C+ (Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear) questionnaire, initially formulated by Armfield [

43], serves as a standardized tool to assess individuals’ levels of dental-related fear and anxiety. It comprises three distinct components: the core section, a stimuli-based section, and a phobia-focused module. The core component investigates four domains—cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and physiological reactions—through a series of items rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The stimuli section gauges the intensity of anxiety triggered by ten specific dental-related situations, also using a five-level scale that spans from "not at all" to "very much" [

43]. Meanwhile, the phobia section includes five binary (yes/no) items to identify signs of dental phobia.

Scoring is derived solely from the core section, calculated by averaging the participants' responses. A threshold value of 3 distinguishes between individuals with and without dental anxiety: scores below 3 suggest no significant anxiety, and scores of 3 or above indicate the presence of dental anxiety [

43,

44].

There is a validated Romanian version of the Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF-4C+). A study published in July 2023 assessed its psychometric properties and found that the Romanian version demonstrated good internal validity, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.945, and strong convergent validity, showing positive correlations with the Dental Anxiety Scale and a single-item measure of dental fear. This suggests that the Romanian IDAF-4C+ is a reliable and valid instrument for assessing dental anxiety and fear in the Romanian population [

45].

This study aimed to evaluate the effects of two relaxation techniques, Breathing Control, and Jacobson’s Progressive Muscle Relaxation, on patients’ anxiety in the dental office and compare their utility in reducing anxiety, as indicated by psychological changes investigated by IDAF-4C+ use, and physiological markers such as blood pressure and heart rate.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the efficacy of two non-pharmacological interventions—Jacobson’s Progressive Muscle Relaxation (JPM) and Breathing Control (BC)—in managing dental anxiety and physiological stress markers (blood pressure and heart rate) among children and adolescents aged 8–17. A total of 189 participants were equally allocated into three groups: JPM, BC, and standard care (control). Using a culturally validated Romanian version of the IDAF-4C⁺, alongside physiological indicators, we observed meaningful patterns of anxiety reduction and response variability across both interventions.

JPM emerged as the most effective intervention, producing a mean IDAF-4C⁺ score reduction of 1.23 points (p < 0.001) and a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.12). This substantial improvement reflects JPM's holistic impact on both somatic and cognitive-emotional dimensions of anxiety. Moreover, physiological responses confirmed these findings, with systolic blood pressure decreasing by 9.4 mmHg on average (p < 0.01) and moderate reductions in heart rate, suggesting a shift toward parasympathetic nervous system dominance—a hallmark of somatic de-arousal. These outcomes are consistent with prior studies emphasizing JPM’s utility in procedural anxiety settings in children and adolescents [

37,

46], and they extend this evidence to a Romanian pediatric population using validated psychometric tools.

The BC intervention also led to significant reductions in anxiety (mean Δ = 0.64, p < 0.05), with a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.61). However, these effects were consistently smaller than those achieved through JPM. While slight declines in heart rate were observed, no statistically significant changes in blood pressure were noted. This profile reflects BC’s narrower therapeutic mechanism, emphasizing autonomic modulation through respiratory control, without the full-spectrum cognitive and somatic engagement characteristic of JPM [

37,

38]. As such, BC may serve as a valuable intervention for children with mild anxiety profiles or in resource-limited settings where brief interventions are needed.

The control group, which received routine dental care without psychological intervention, showed no significant changes in IDAF-4C⁺ scores or physiological indicators. This result underscores the necessity of incorporating structured anxiety-reduction techniques into pediatric dental care, particularly for patients with pre-existing anxiety.

Heart rate and blood pressure reductions followed a similar pattern. While both interventions contributed to improvements, only JPM achieved statistically significant inter-group differences in BP. The absence of significant HR differences between groups despite within-group improvements, might be explained by inter-individual variability, younger participants' baseline cardiovascular dynamics, or the shorter exposure to interventions.

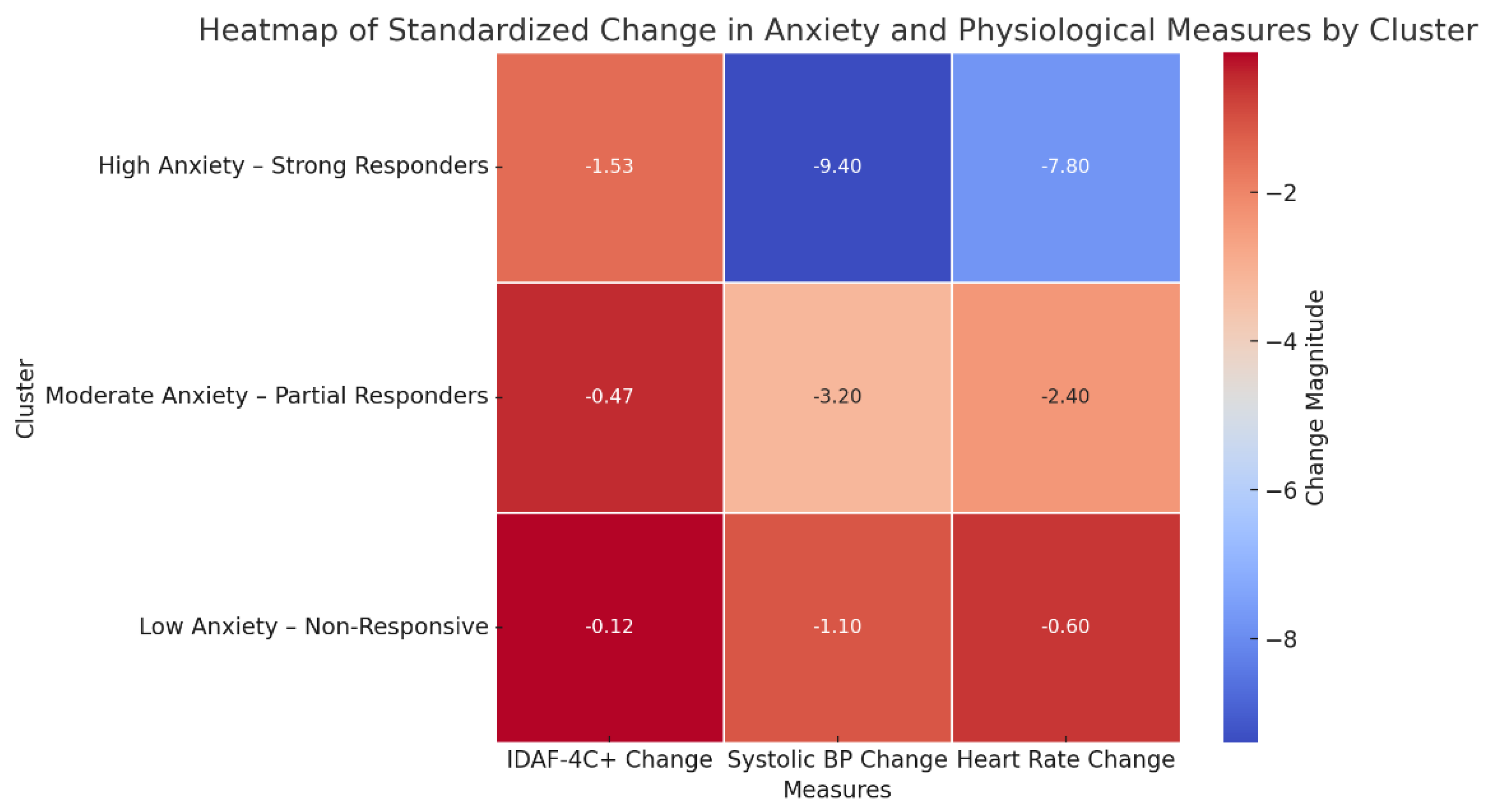

To explore response heterogeneity, hierarchical agglomerative clustering was applied to standardized pre-to-post changes in IDAF-4C⁺, systolic/diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate across all participants. The three-cluster solution offered nuanced, clinically relevant insights:

Cluster 1 – “high anxiety – strong responders” (n = 58): participants in this group showed the most reduction in IDAF-4C⁺ (mean from 3.91 to 2.38), along with significant physiological improvements. Predominantly composed of JPM participants (62%), this cluster included younger adolescents (8–12 years) and a higher proportion of females—demographic factors often associated with increased dental fear and greater reactivity to relaxation techniques [

47,

48]. These children likely exhibit heightened baseline anxiety and respond to multi-modal relaxation techniques that engage both cognitive and somatic components, such as JPM.

Cluster 2 – “moderate anxiety – partial responders” (n = 74) across all study groups, these participants presented with moderate anxiety levels and showed minor reductions in anxiety, without statistically significant physiological change. This cluster suggests that for children having moderate distress, even minimal interventions or exposure to a familiar clinical setting may elicit improvement.

Cluster 3 – “low anxiety – non-responsive” (n = 57): present in all groups, including JPM, this cluster comprised children with consistently low IDAF-4C⁺ scores (<2.5) and negligible physiological or psychological change. These children appear to possess intrinsic emotional resilience, indicating that additional psychological interventions may not be necessary or efficient in such cases.

These results increase ecological validity by demonstrating that not all children benefit equally, an important finding for clinical applications.

This cluster-based approach enriched the interpretation of treatment effects and reinforced the principle that anxiety interventions should be personalized, rather than uniformly applied. It adds depth to the interpretation and increases ecological validity, showcasing that psychological techniques must be tailored to individual needs.

Previous studies have underscored the usefulness of JPM in reducing procedural anxiety in pediatric populations, especially in contexts like preoperative settings, school stress, or behavioral therapy [

48,

49,

50]. Our findings are consistent while contributing novel data through the Romanian-validated version of IDAF-4C⁺, addressing the limitations of previous studies that used unvalidated scales like STAI for children [

51]. Other strengths include the use of exploratory clustering analysis to enhance the personalization of strategies and a controlled design that enables a clear interpretation of therapeutic effects.

The study’s findings reinforce a multi-dimensional understanding of dental anxiety, implicating physiological arousal and cognitive-emotional processing. JPM’s superiority likely stems from its dual-action mechanism: reducing muscle tension while redirecting attention away from threatening stimuli. In contrast, BC appears to primarily modulate autonomic arousal without significantly influencing cognitive or emotional dimensions of anxiety. A controlled design with a sufficient sample size (n = 189), objective physiological measures alongside self-reported anxiety, and cluster analysis to explore heterogeneity in treatment response are clear strengths of this research.

The clinical implications are substantial. Implementing brief relaxation interventions, especially JPM, before dental procedures may significantly reduce patient distress, increase cooperation, and improve procedural efficiency in pediatric dental practices. These approaches are non-invasive, cost-effective, and easily integrated into routine care. Non-uniform treatment responses support the development of pre-treatment screening tools—potentially supported by decision algorithms—to match interventions to patient profiles based on baseline anxiety, age, sex, or dental history [

4,

10,

22,

37,

49].

Given its minimal training requirements, non-invasiveness, and low cost, JPM represents a practical and effective strategy for pediatric dental anxiety. Its integration into routine care could improve both patient experience and procedural cooperation.

Despite its strengths—including controlled group allocation, a culturally validated anxiety measure, and objective physiological data—this study has limitations. The short-term design precludes conclusions about long-term anxiety reduction or behavioral changes. The fidelity of intervention delivery was not formally assessed, potentially introducing variability in therapeutic exposure. Additionally, contextual factors such as parental anxiety, previous trauma, or clinician-child rapport were not measured, yet these could substantially influence outcomes. Physiological data (HR and BP) may also be sensitive to external stressors unrelated to dental anxiety. Finally, while the cluster analysis yielded insights, it was exploratory and lacked external validation; replication in larger samples is necessary.

Future research should employ longitudinal follow-up to assess the durability of anxiety reduction and examine its impact on future dental cooperation. Studies should also investigate behavioral predictors—such as temperament, attachment style, or family dynamics to personalize interventions. Furthermore, digital integration of JPM via mobile applications could enable pre-visit training, increase accessibility, and prepare children outside the clinical setting. Expanding this model to multi-center trials would improve generalizability and allow cross-cultural comparisons, especially in underserved populations.