1. Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains a major global public health concern, despite the availability of curative treatments. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that approximately 50 million people are chronically infected with HCV worldwide, with up to 1 million new infections annually [

1]. Individuals with chronic HCV infection are at risk of developing liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), contributing to more than 242,000 deaths annually due to HCV-related liver diseases [

1].

HCV is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus, and its RNA polymerase lacks proofreading activity, leading to a high mutation rate (10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁴ nucleotide substitutions per site per year) [

2,

3,

4]. This rapid mutation results in extensive genetic diversity, forming what is known as a quasispecies, which influences viral persistence, immune evasion, and drug resistance. HCV has been recently classified into eight major genotypes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] and 93 subtypes [

5,

6]. HCV genotypes exhibit distinct geographical distributions. For instance, genotypes 1 and 3 are highly prevalent worldwide, while genotype 4 is predominantly found in Africa, and genotype 6 is more common in Asia [

7]. HCV genotyping is essential for epidemiological tracking, outbreak investigation, and clinical management, as treatment responses and disease progression differ by genotype [

8,

9]. Additionally, mixed HCV infections (infections with multiple genotypes) may impact disease course and treatment efficacy [

10].

Despite the availability of pan-genotypic direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), HCV genotyping continues to be clinically relevant due to genotype-specific differences in therapeutic response and disease outcomes. While pan-genotypic DAAs are highly effective, their efficacy can vary across different genotypes. For instance, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir achieve high cure rates across all genotypes but genotype 3 infections, particularly in cirrhotic patients, often require extended treatment durations or the addition of ribavirin to ensure optimal outcomes [

11]. Additionally, certain HCV genotypes also exhibit a higher tendency for resistance-associated substitutions (RASs), which can reduce treatment efficacy. The occurrence and pattern of RASs vary across genotypes and are particularly heterogeneous among subtypes within genotypes 2 through 6 [

12]. Genotype 3 is particularly challenging, as it has higher relapse rates and frequent baseline resistance mutations (e.g., Y93H in NS5A inhibitors), requiring close monitoring and regimen adjustments [

13]. Moreover, genotype variation impacts disease progression, with genotypes 1 and 3 being associated with faster fibrosis progression and an increased risk of HCC, underscoring the importance of early intervention [

14]. Furthermore, mixed-genotype infections can occur, particularly in regions with high HCV diversity, and DAAs may not always exhibit uniform efficacy against such infections, making HCV genotyping valuable in special cases [

10]. Beyond individual patient management, tracking genotype distribution plays a critical role in public health surveillance, helping to monitor transmission trends, detect potential outbreaks, and evaluate the effectiveness of HCV elimination programs. Genotype-specific data also informs policymakers, enabling them to strategically allocate resources for screening, prevention, and treatment, particularly in high-risk populations.

In Thailand, HCV seroprevalence has slightly declined from 2004 to 2014, with a prevalence of ~2% in the general population [

15,

16]. However, HCV seroprevalence increases significantly among HIV-infected individuals with a history of injection drug use (up to 8%) [

17]. Among anti-HCV-positive individuals, 43–75% were HCV RNA-positive, indicating active infection [

18,

19]. Approximately two decades ago, the distribution of HCV genotypes in Thailand was relatively stable, with genotype 3a being the most dominant (39–51%), followed by genotype 1b (20–27%), genotype 6 (9–18%), and genotype 1a (7–9%) [

16,

20]. However, between 2007 and 2012, a shift in genotype prevalence was observed, with genotype 3a still predominant (36%), but followed by an increased proportion of genotype 6 (21%), genotype 1a (20%), genotype 1b (13%), and genotype 3b (10%) [

21]. The northern region of Thailand has reported high HCV prevalence, yet current genotype distribution data remain limited [

22]. Updated genotype surveillance data are urgently needed to inform treatment policies and elimination strategies. Therefore, this study aims to assess the molecular epidemiology of HCV genotypes circulating in northern Thailand.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Data Collection

This retrospective study was conducted at the Clinical Microbiology Service Unit (CMSU) Laboratory, PROMPT Health Center, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Thailand, between April 2016 and June 2024. HCV genotyping data were obtained from patients who underwent routine molecular diagnostic testing for clinical evaluation. Inclusion criteria comprised adults with a detectable HCV viral load exceeding 2,000 IU/mL, as determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Demographic and clinical data, including age, sex, and HCV viral load, were extracted from electronic laboratory information systems and anonymized patient records. For patients with multiple test records, only the earliest sample with complete genotyping results was included in the study.

2.2. RNA Extraction, HCV Viral Load, and Genotyping

HCV RNA was extracted from 200 µL of plasma using the High Pure Viral RNA Kit

® (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of HCV RNA was performed using the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HCV Test v2.0

® (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA, USA), a real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay with a lower limit of detection (LOD) of 15 IU/mL. Genotyping was conducted using two validated molecular methods: Sanger sequencing (n = 809) and reverse hybridization line probe assay (LiPA) (n = 928). For sequencing, viral RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA), followed by PCR amplification of the 5' untranslated region (5'UTR) and core region using standardized primers. Sequencing was performed on an ABI Prism 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Genotypes were assigned using the LANL HCV BASIC BLAST tool (

https://hcv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/BASIC_BLAST/ basicblast.html), with reference to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) classification. For LiPA-based genotyping, the VERSANT HCV Genotype 2.0 Assay® (Bayer Healthcare, Tarrytown, NY, USA) was used. This assay is based on reverse hybridization of amplified HCV RNA fragments to immobilized genotype-specific oligonucleotide probes on a nitrocellulose strip, allowing subtype resolution based on banding patterns.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) after assessment for normality using Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons of HCV viral loads across genotypes were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test due to non-parametric distribution. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA® version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Clinical and laboratory data of 1,737 HCV-infected patients tested between April 2016 and June 2024 were analyzed. Among all HCV-infected patients, 1,121 (65%) were male, 608 (35%) were female. The age of patients was ranging from 18 to 102 years old with a median age of 57 years old (IQR: 49–65). The median value of HCV viral load was 6.15 log

10 IU/mL (IQR: 5.46–6.65) (

Table 1).

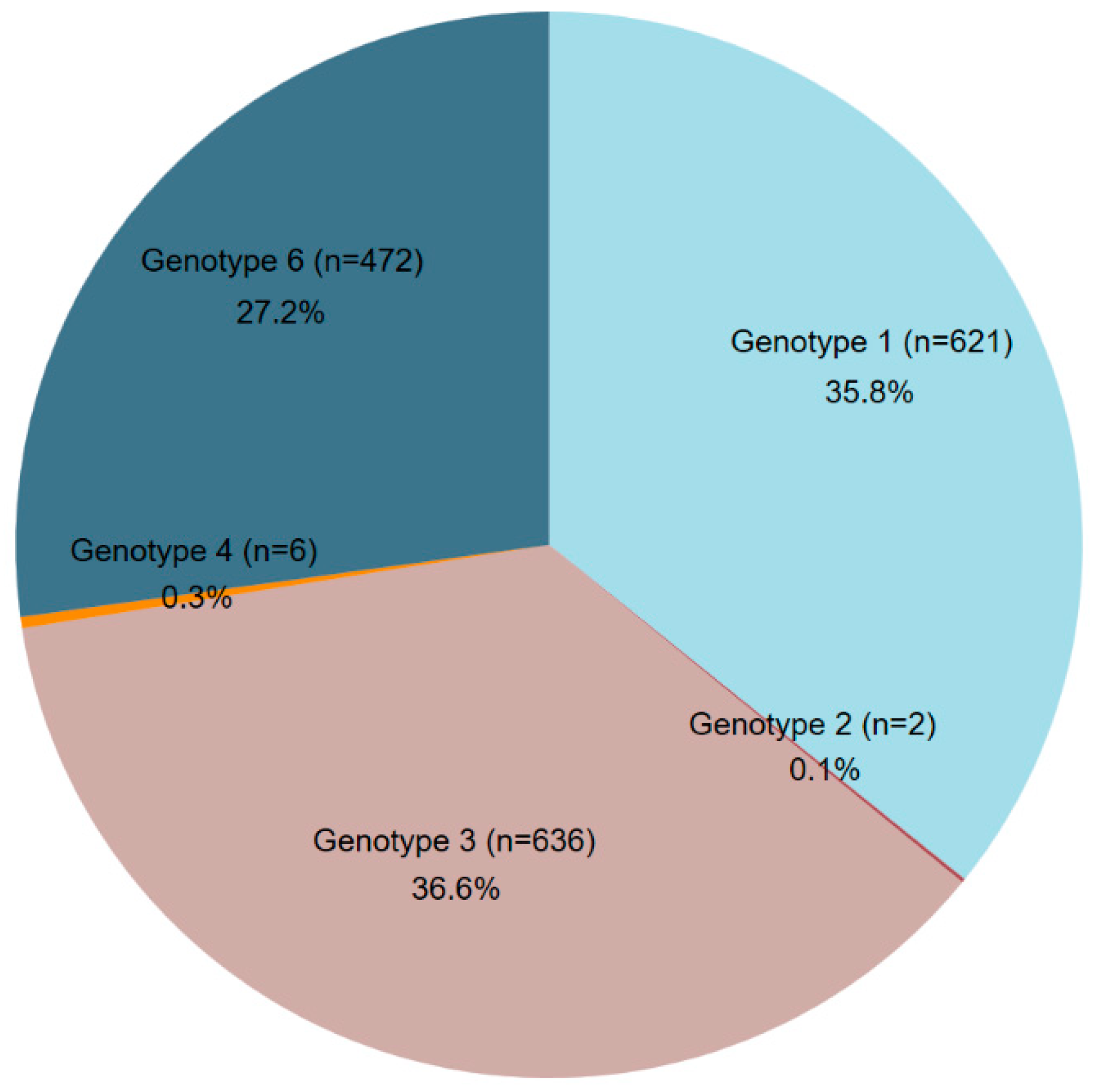

3.2. Distribution of HCV Genotypes and Subtypes

The distribution of HCV genotypes in 1,737 HCV-infected patients showed that genotype 3 was the most prevalent, accounting for 36.6%, followed by genotype 1 at 35.8%. Genotype 6 was also common, representing 27.2% of cases, while other genotypes, including genotypes 2 and 4, were detected at much lower frequencies, comprising 0.1% and 0.3%, respectively (

Figure 1). Further analysis of HCV subtypes revealed a diverse range within each genotype. Among genotype 1, subtypes 1a (22.1%) and 1b (12.6%) were identified, while genotype 3 was primarily composed of subtype 3a (27.2%) and 3b (7.7%). Genotype 6 exhibited multiple subtypes, including 6 (c-l) (13.5%), 6n (6.6%), and 6f (2.1%), reflecting its high genetic diversity in certain populations. The low prevalence of other subtypes, including subtype 2a, 2b, 4d, 6a, 6b, 6e, 6h, 6i, 6j, 6l, 6m, and 6u, was found in <1%. Moreover, mixed infections between subtypes 6a and 6b were also found in <1% (n=1).

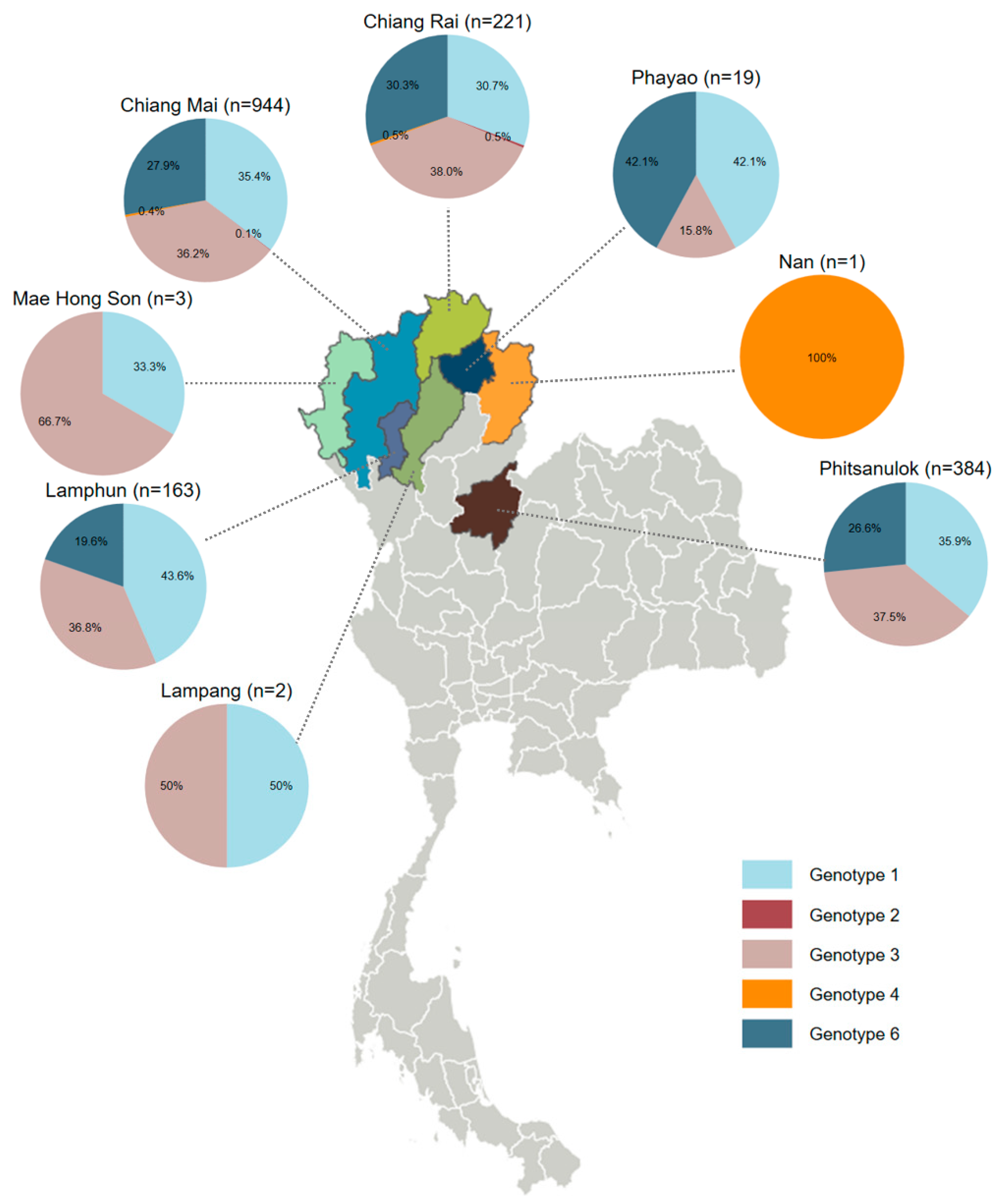

3.3. Geographic Distribution of HCV Genotypes in Northern Thailand

The geographic distribution of HCV genotypes in northern Thailand reveals distinct patterns across provinces (

Figure 2). Chiang Mai and Phitsanulok had the largest sample sizes, providing crucial insights into the regional genotype data with genotypes 1 (35.4–35.9%), 3 (36.2–37.5%), and 6 (26.6–27.9%). In Chiang Rai, genotype 3 was the most common, accounting for 38.0% of cases, while Lamphun exhibited a notable prevalence of genotypes 1 and 3 with 43.6% and 36.8%, respectively. Although there were a low number of cases, genotypes 1, 3, and 6 were found in Phayao; only genotypes 1 and 3 were detected in Mae Hong Son and Lampang.

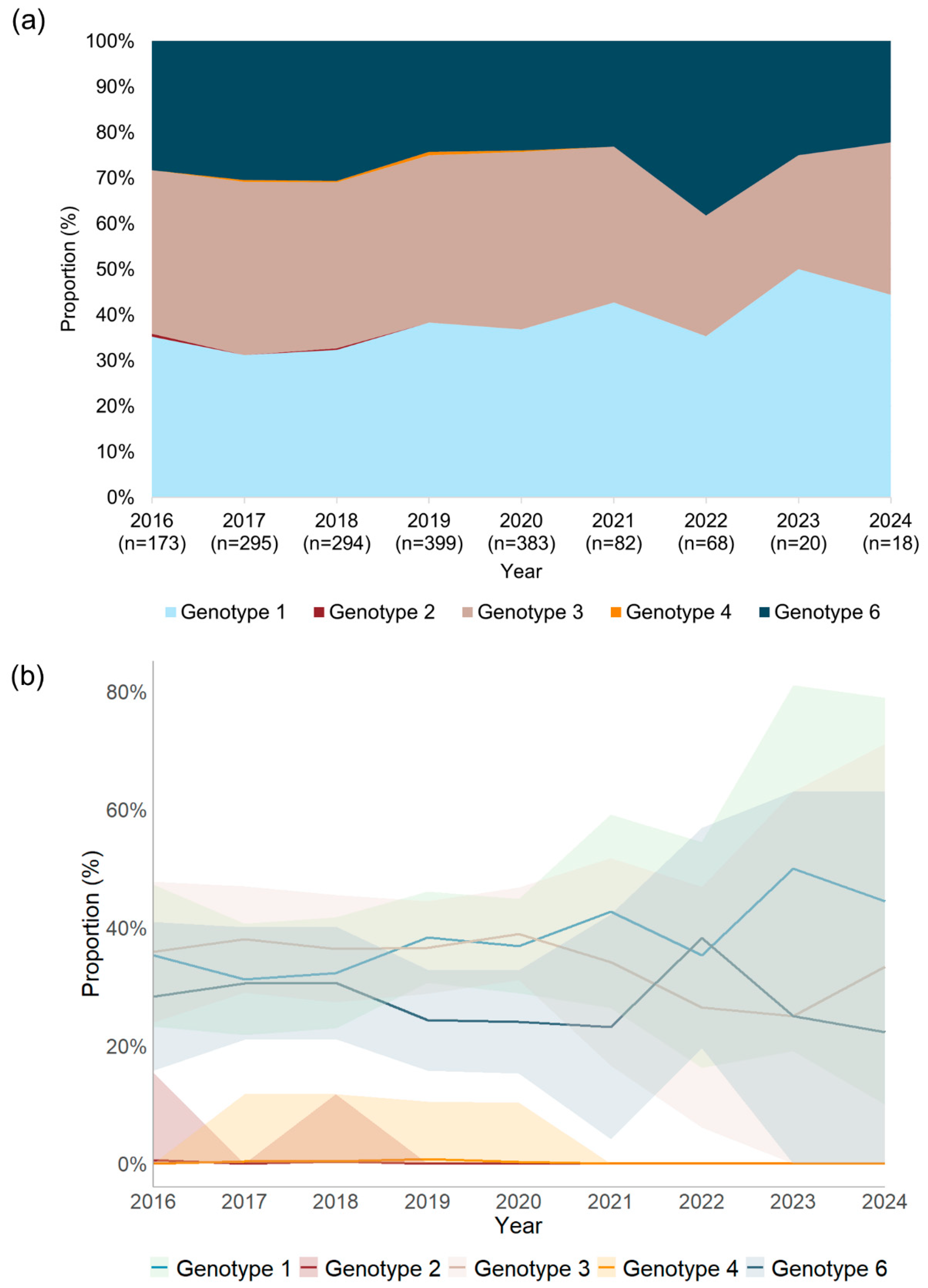

3.4. Temporal Trends in HCV Genotype Distribution

HCV genotype distribution showed notable changes over the study period from 2016 to 2024. Genotype 1 consistently presented across all years from 2016 to 2018 and gradually increased after 2019, while genotype 3 also remained a major contributor, though its proportion varied. A decline in the proportion of genotype 3 was found during 2022 and 2023. Genotype 6 showed a stable trend from 2016 to 2021 but gradually increased the proportion from 2021 onward. Interestingly, genotype 4 exhibited a peak in 2019 before decreasing in subsequent years, whereas genotype 2 was only detected sporadically, with its presence diminishing after 2018 (

Figure 3).

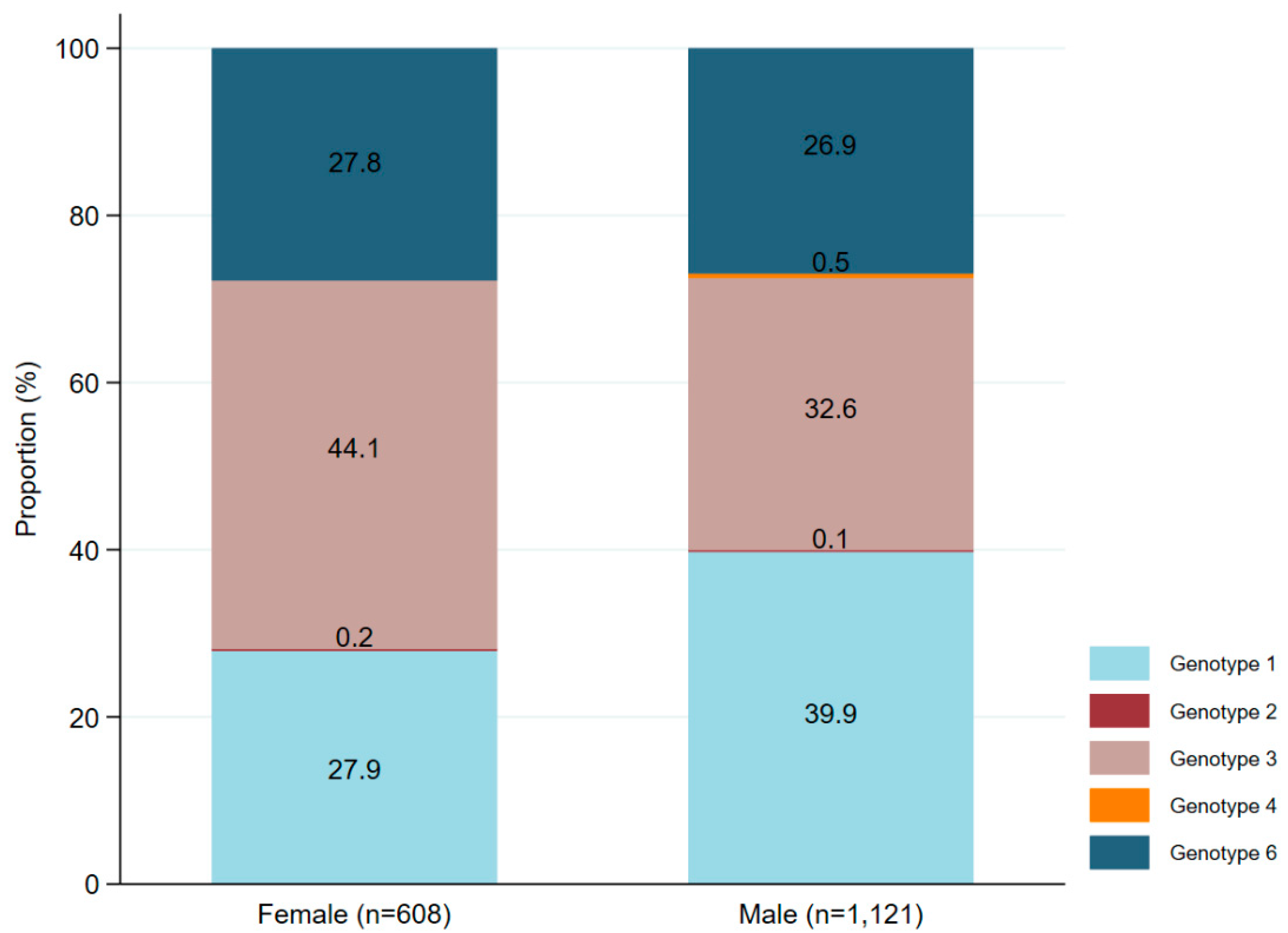

3.5. Distribution of HCV Genotypes by Sex

The prevalence of HCV genotypes was found to be varied by sex. Genotypes 1, 3, and 6 were detected in both males and females, with slightly different proportion between the two groups (

Figure 4). Genotype 1 was found to be significantly higher in males (

p<0.0001), whereas genotype 3 was significantly higher in females (

p<0.0001). Genotype 6 remained consistently present across both sexes in comparable proportions (

p=0.69). In contrast, genotypes 2 and 4 were rare, with only a few cases identified. Interestingly, genotype 4 was found only in males and was absent in females.

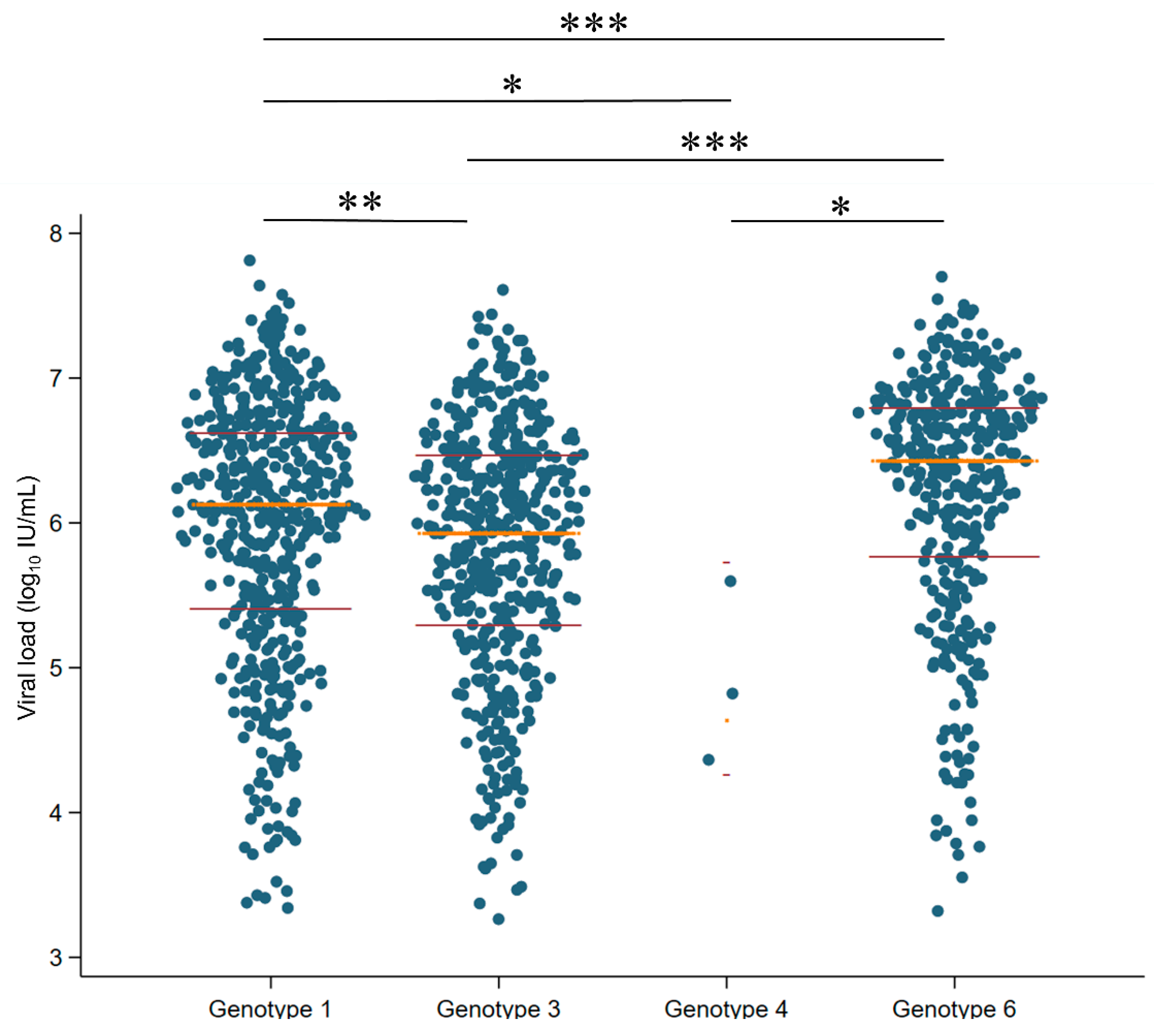

3.6. Association Between Different HCV Genotypes and Viral Load

The association between HCV viral load and different HCV genotypes was analysed (

Figure 5). We found that genotypes 1 and 6 showed high median viral loads with 6.13 and 6.43 Log

10 IU/mL, respectively. Moreover, genotype 6 showed statistically significant differences with genotype 1 (

p<0.0001), genotype 3 (

p<0.0001), and genotype 4 (

p=0.02). Similarly, genotype 1 also showed an association with a higher viral load than genotype 3 (

p=0.003) and genotype 4 (

p=0.04). Despite the low prevalence of genotype 4, it did not show statistically significant differences with genotype 3 in terms of viral load.

4. Discussion

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection continues to pose a significant public health burden in Thailand, particularly in the northern region, where genotype distribution remains diverse. This study provides updated molecular epidemiological data, identifying subtype 3a as the most prevalent, followed by subtypes 1a, 6 (c–l), 1b, and 3b. These findings are consistent with earlier reports that documented the predominance of subtype 3a (39-51%) in Thailand [

16,

20]. Notably, we observed an increasing trend in the prevalence of genotype 6, a pattern that merits further surveillance and clinical evaluation given the limited treatment data available for this genotype [

23]. The observed regional variation in genotype distribution aligns with the known endemicity of genotype 6 in Southeast Asia [

22,

27]. Provinces such as Chiang Mai and Phitsanulok demonstrated high proportions of genotypes 1, 3, and 6, with genotype 3 remaining highly prevalent in high-burden areas. These data support the need for regionally tailored screening and treatment strategies to achieve optimal outcomes.

While pan-genotypic direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have simplified HCV treatment globally, genotype-specific differences remain clinically significant. Genotype 3, particularly in cirrhotic individuals, is associated with suboptimal treatment response and a higher prevalence of baseline resistance-associated substitutions (RASs), such as Y93H in the NS5A region [

12,

13]. Our findings reinforce the dominance of genotype 3a in Thailand but highlight an emerging shift toward greater genotype 6 representation. Given the extensive heterogeneity within genotype 6 and its underrepresentation in clinical trials, further studies are essential to elucidate subtype-specific treatment efficacy, resistance profiles, and long-term clinical outcomes [

24]. The presence of genotype 4, though rare in this cohort, emphasizes the importance of genotyping for detecting atypical or imported strains. Genotype 4, typically endemic in the Middle East and Africa, may reflect migration-linked transmission [

25]. The detection of multiple genotypes also raises considerations regarding diagnostic accuracy and treatment regimen design, especially in high-risk or immunocompromised populations [

10].

Our sex-disaggregated analysis demonstrated a higher HCV prevalence in males (64%), consistent with previous studies indicating increased exposure to behavioural risk factors such as injection drug use and occupational blood exposure [

26,

27]. In contrast, female HCV progression may be modulated by hormonal factors, including estrogen-mediated immunomodulation [

28,

29]. Additionally, most infections were observed in individuals over the age of 35, consistent with past iatrogenic or behavioural exposures prior to the widespread implementation of modern blood safety protocols [

30].

From a virological perspective, genotypes 1 and 3 remain the most strongly associated with advanced liver disease, including cirrhosis and HCC [

14,

31,

32]. Genotype 3 has also been linked to hepatic steatosis, an independent driver of fibrosis progression [

33]. In this study, genotype 1 was more prevalent in males, while genotype 3 was more common among females—a pattern reported in other geographic regions [

34]. Interestingly, genotype 6 was associated with the highest viral load, potentially reflecting higher replication efficiency while other studies have reported higher viral loads in genotype 1 infection [

35]. This variability underscores the need to further investigate genotype 6 virological behaviours and its clinical implications.

Thailand has committed to eliminating HCV as a public health threat by 2030, in line with the WHO Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis. Achieving this goal will require robust screening, early diagnosis, and optimized treatment protocols. Although pan-genotypic regimens have improved treatment access, HCV genotyping remains critical for: 1) guiding treatment duration and adjunctive therapies, especially in genotypes 3 and 6; 2) detecting resistance-associated mutations; 3) identifying mixed-genotype infections; and 4) informing targeted public health responses.

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. First, incomplete demographic data limited the analysis of host factors associated with genotype variation. Second, RAS profiling was not performed, restricting conclusions about genotype-specific resistance. Third, as the study focused on a single geographic region, the findings may not be fully generalizable to other parts of Thailand. Future research should prioritize nationwide genotype surveillance, characterization of RASs, and real-world assessments of DAA efficacy—particularly for genotype 6. Additionally, integration of HCV testing with HIV and HBV screening could improve co-infection management. Finally, expanding access to rapid, affordable genotyping tools remains a critical priority, especially in resource-limited settings.

In conclusion, our findings provide updated insight into HCV genotype distribution in northern Thailand, affirming the dominance of subtype 3a while highlighting a growing burden of genotype 6. These data underscore the ongoing clinical and public health value of HCV genotyping in guiding treatment decisions and elimination strategies. As Thailand moves toward its 2030 elimination target, genotype-informed approaches will be essential for reducing HCV-related morbidity and mortality.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, W.K., N.K.; Methodology, N.K.K., S.P., T.K. and P.P.; Software, N.K.K.; Validation, S.I., K.T., K.P., T.S.C., N.K. and W.K.; Formal Analysis, N.K.K., S.P., T.K. and P.P.; Investigation, All; Resources, S.I., K.T., K.P., T.S.C., N.K. and W.K.; Data Curation, S.P., T.K. and P.P.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, N.K.K., N.K. and W.K.; Writing – Review & Editing, All; Visualization, N.K.K.; Supervision, K.T., K.P., T.S.C., N.K. and W.K.; Project Administration, T.S.C. and N.K.; Funding Acquisition, T.S.C. and N.K.

Funding

The article processing charge (APC) was partially supported by Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University (Approval No: AMSEC-68EM-011).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Chiang Mai University, Thailand for providing financial support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis C. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Nakamura, F.; Takeda, H.; Ueda, Y.; Takai, A.; Takahashi, K.; Eso, Y.; et al. Mutational spectrum of hepatitis C virus in patients with chronic hepatitis C determined by single molecule real-time sequencing. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas, J.M.; González-Candelas, F.; Moya, A.; Sanjuán, R. Effect of ribavirin on the mutation rate and spectrum of hepatitis C virus in vivo. J Virol. 2009, 83, 5760–5764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, R.; Estada, Ú.; Peris, J.B.; Andreu, I.; Bou, J.V.; Garijo, R.; et al. Highly heterogeneous mutation rates in the hepatitis C virus genome. Nat Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgia, S.M.; Hedskog, C.; Parhy, B.; Hyland, R.H.; Stamm, L.M.; Brainard, D.M.; et al. Identification of a Novel Hepatitis C Virus Genotype From Punjab, India: Expanding Classification of Hepatitis C Virus Into 8 Genotypes. J Infect Dis. 2018, 218, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses: ICTV. Flaviviridae: Hepacivirus C Classification. Available online: https://ictv.global/sg_wiki/flaviviridae/hepacivirus (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Petruzziello, A.; Marigliano, S.; Loquercio, G.; Cozzolino, A.; Cacciapuoti, C. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: An up-date of the distribution and circulation of hepatitis C virus genotypes. World J Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 7824–7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, A.M.; Hammad, M.S.; Mabrouk, M.S.; Al-Atabany, W.I. On leveraging self-supervised learning for accurate HCV genotyping. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 15463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keikha, M.; Eslami, M.; Yousefi, B.; Ali-Hassanzadeh, M.; Kamali, A.; Yousefi, M.; et al. HCV genotypes and their determinative role in hepatitis C treatment. Virusdisease. 2020, 31, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, E.B.; Applegate, T.L.; Lloyd, A.R.; Dore, G.J.; Grebely, J. Mixed HCV infection and reinfection in people who inject drugs—impact on therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015, 12, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series(☆). J Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1170–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrazin, C. Treatment failure with DAA therapy: Importance of resistance. J Hepatol. 2021, 74, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlotsky, J.M. Hepatitis C Virus Resistance to Direct-Acting Antiviral Drugs in Interferon-Free Regimens. Gastroenterology. 2016, 151, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F.; Kramer, J.R.; Ilyas, J.; Duan, Z.; El-Serag, H.B. HCV genotype 3 is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer in a national sample of U.S. Veterans with HCV. Hepatology. 2014, 60, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasitthankasem, R.; Posuwan, N.; Vichaiwattana, P.; Theamboonlers, A.; Klinfueng, S.; Vuthitanachot, V.; et al. Decreasing Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Thailand in the Past Decade: Evidence from the 2014 National Survey. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0149362. [Google Scholar]

- Sunanchaikarn, S.; Theamboonlers, A.; Chongsrisawat, V.; Yoocharoen, P.; Tharmaphornpilas, P.; Warinsathien, P.; et al. Seroepidemiology and genotypes of hepatitis C virus in Thailand. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2007, 25, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jatapai, A.; Nelson, K.E.; Chuenchitra, T.; Kana, K.; Eiumtrakul, S.; Sunantarod, E.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among young Thai men. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 83, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratedrat, P.; Nilyanimit, P.; Wasitthankasem, R.; Posuwan, N.; Auphimai, C.; Hansoongnern, P.; et al. Qualitative hepatitis C virus RNA assay identifies active infection with sufficient viral load for treatment among Phetchabun residents in Thailand. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0268728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Geng, N.; Zhu, W.; Liu, H.; Bai, H. Prevalence and characteristics of hepatitis C virus infection in Shenyang City, Northeast China, and prediction of HCV RNA positivity according to serum anti-HCV level: retrospective review of hospital data. Virol J. 2020, 17, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanistanon, D.; Neelamek, M.; Dharakul, T.; Songsivilai, S. Genotypic distribution of hepatitis C virus in different regions of Thailand. J Clin Microbiol. 1997, 35, 1772–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasitthankasem, R.; Vongpunsawad, S.; Siripon, N.; Suya, C.; Chulothok, P.; Chaiear, K.; et al. Genotypic distribution of hepatitis C virus in Thailand and Southeast Asia. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0126764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasitthankasem, R.; Pimsingh, N.; Treesun, K.; Posuwan, N.; Vichaiwattana, P.; Auphimai, C.; et al. Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus in an Endemic Area of Thailand: Burden Assessment toward HCV Elimination. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020, 103, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.M.; Wu, G.Y. Hepatitis C Virus: A Review of Treatment Guidelines, Cost-effectiveness, and Access to Therapy. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016, 4, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vo-Quang, E.; Pawlotsky, J.M. 'Unusual' HCV genotype subtypes: origin, distribution, sensitivity to direct-acting antiviral drugs and behaviour on antiviral treatment and retreatment. Gut. 2024, 73, 1570–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guntipalli, P.; Pakala, R.; Kumari Gara, S.; Ahmed, F.; Bhatnagar, A.; Endaya Coronel, M.K.; et al. Worldwide prevalence, genotype distribution and management of hepatitis C. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2021, 84, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Gawad, M.; Nour, M.; El-Raey, F.; Nagdy, H.; Almansoury, Y.; El-Kassas, M. Gender differences in prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Egypt: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgard, H.; Weir, A.; Palmateer, N.; Lo Re, V., III; Pineda, J.A.; Macías, J.; et al. HCV epidemiology in high-risk groups and the risk of reinfection. J Hepatol. 2016, 65, S33–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, V.; Lebray, P.; Myers, R.P.; Pannier, E.; Paradis, V.; Charlotte, F.; et al. Progression of liver fibrosis in women infected with hepatitis C: long-term benefit of estrogen exposure. Hepatology. 2004, 40, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaglia, M.N.; Harris, J.M.; Smirnov, A.; Burlone, M.E.; Rigamonti, C.; Pirisi, M.; et al. 17β-Oestradiol Protects from Hepatitis C Virus Infection through Induction of Type I Interferon. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasitthankasem, R.; Vichaiwattana, P.; Siripon, N.; Posuwan, N.; Auphimai, C.; Klinfueng, S.; et al. Birth-cohort HCV screening target in Thailand to expand and optimize the national HCV screening for public health policy. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0202991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.J.; Jeong, S.H.; Han, B.H.; Lee, S.U.; Yun, B.C.; Park, E.T. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes and the influence of HCV subtype 1b on the progression of chronic hepatitis C in Korea: a single center experience. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012, 18, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Rao, H.Y.; Yang, W.B.; Gao, Z.L.; Yang, R.F.; Fei, R.; et al. Impact of hepatitis C virus genotype 3 on liver disease progression in a Chinese national cohort. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020, 133, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Patel, K.; Naggie, S. Genotype 3 Infection: The Last Stand of Hepatitis C Virus. Drugs. 2017, 77, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daw, M.A.; El-Bouzedi, A.; Dau, A.A. Geographic distribution of HCV genotypes in Libya and analysis of risk factors involved in their transmission. BMC Res Notes. 2015, 8, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarti, A.; Dogra, G.; Verma, V.; Srivastava, A.P. Distribution pattern of HCV genotypes & its association with viral load. Indian J Med Res. 2011, 133, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).