1. Introduction

With the explosive growth of data in the information age, the demand for timely processing and response to large-scale data has placed higher requirements on the speed and capacity of storage devices [

1]. However, existing storage systems are increasingly unable to meet current demands due to limitations in DRAM capacity, refresh power consumption, and other factors [

2,

3]. A DRAM storage cell consists of a capacitor and a transistor, where the capacitor is used to store charge representing binary data, and the transistor controls read and write operations. As storage density increases, the reduction in capacitor size results in decreased charge storage capability, leading to shorter data retention times and more severe charge leakage issues. To ensure data reliability, more frequent refresh operations are required, which not only increase system power consumption, but also complicate circuit design. Furthermore, DRAM cells require extremely high precision in manufacturing processes, further constraining their scalability for high-capacity integration.

Due to the challenges of DRAM capacity scaling and refresh power consumption, non-volatile memory (NVM) technologies such as phase-change memory (PCM) [

4,

5,

6] and resistive RAM (RRAM) [

6,

7] are suitable replacement candidates for DRAM due to their low refresh power and better scaling potential. These technologies offer advantages such as high capacity, fast read speeds, and no refresh power consumption, making them promising candidates to replace traditional DRAM as the primary memory in future computing systems. However, compared to DRAM, NVM still has several critical limitations that need to be addressed, the most significant of which being its longer write latency and limited endurance [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The write endurance of NVM cells ranges from

to

, which is significantly lower than the lifetime of DRAM. Since memory systems are subject to highly frequent write operations, NVM can fail after a certain number of writes, leading to system crashes. Therefore, for NVM to be used as memory, the issue of limited lifetime must be addressed.

NVM can only endure a limited number of bit flips, which leads to the issue of limited endurance. Thus, improving its lifetime depends on reducing the number of bit flips in NVM cells. Existing research generally falls into two categories: one approach involves adding flag bits to control bit flips in different regions of the cache line. For example, FNW (Flip-N-Write) [

12] compares old and new data to reduce the number of flipped bits by at least half. Another method, such as FlipMin [

13], increases flag bits to provide alternative encodings for written data. By calculating the Hamming distance between the new data and the existing data during write operations, an encoding is chosen that minimizes the total bit flips, thus reducing bit flips in the region. The second approach reduces the data written to NVM through compression. For example, FPC [

14] matches NVM words to fixed static patterns (such as all-zero blocks, repeated values, or high-order similar values), and when a match is found, it uses a 3-bit encoding to replace the corresponding word, reducing the number of writes to NVM. BDI [

15,

16] performs compression based on cache line similarity by selecting a base value from a data block, calculating the difference (Delta) between each data item and the base value, and storing these differences with a smaller bit width (such as 8-bit or 16-bit), achieving compression. For data that cannot be represented as differences, it is directly stored as immediate values.

However, these methods are limited to specific cache lines or emphasize only intra-cache line similarity, thereby failing to exploit the potential inter-cache line similarity. Therefore, we propose a dynamic approach to track the frequency of words in cache lines, enabling us to match high-frequency words that may appear at different stages of the workload, thereby reducing the amount of data written to NVM. Our main contributions are as follows:

We demonstrate that different high-frequency words may appear at various stages of the workload.

We design a dynamic compression algorithm that can track high-frequency words in cache lines at different stages and dynamically update a high-frequency word table based on the counts.

We implement our algorithm on Gem and NVMain and demonstrate its effectiveness.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the basics of NVM and compression methods as well as the motivation of this paper.

Section 3 presents the design of DCom.

Section 4 shows the experimental setup and evaluation results of DCom.

Section 5 reviews existing work, and

Section 6 concludes this paper.

2. Background and Motivation

This section begins with an introduction to the basics of NVM. Next, we review existing methods for reducing NVM writes. Finally, we present the preliminary study that serves as the motivation for this paper.

2.1. Basics of NVM

Compared to traditional storage technologies, Non-Volatile Memory offers several significant advantages. Firstly, its data persistence is a core feature, enabling data integrity to be maintained even during power outages. This makes NVM particularly suitable for applications where data need to be preserved for long periods while being frequently accessed. Secondly, NVM exhibits lower power consumption since it does not require continuous power supply to retain data, significantly reducing the energy consumption of storage systems. This is especially advantageous for mobile devices and energy-sensitive systems. Additionally, some NVM technologies, such as MRAM and ReRAM, offer read and write speeds close to that of DRAM, allowing NVM to approach the performance of volatile memory. Furthermore, NVM provides high storage density, enabling a larger amount of data to be stored in a smaller area, which meets the growing demand for high-capacity storage [

17,

18].

However, despite its immense potential in storage applications, NVM still faces several limitations [

19,

20]. Firstly, certain NVM technologies suffer from high write latency, with write speeds significantly slower than read speeds, which impacts overall performance. Moreover, limited write endurance remains a critical challenge for NVM, especially for PCM, where the number of read/write cycles that a storage unit can endure is finite. Over time, these storage units may begin to fail. This issue arises because PCM relies on the phase change of chalcogenide materials to represent data, and each write or erase operation involves heating the material to different temperatures to switch it between amorphous and crystalline states [

21]. These high-temperature operations cause thermal stress and material degradation in the memory cells, gradually reducing their ability to undergo reliable phase transitions with repeated write and erase cycles, ultimately leading to failure in data retention. Therefore, addressing the physical wear caused by frequent write operations and enhancing the longevity of NVM is a critical area of ongoing research and optimization.

2.2. Existing Solutions

While NVM offers advantages like data persistence, low power consumption, and high storage density, it also faces challenges such as high write latency and limited write endurance, especially in technologies like PCM, where frequent writes cause thermal stress and material degradation. To address these, optimizing data storage and transfer efficiency is crucial. NVM compression is an effective solution, as it reduces memory traffic, minimizes storage overhead, and lowers write operations, thus alleviating wear on NVM cells [

14,

15,

16,

22].

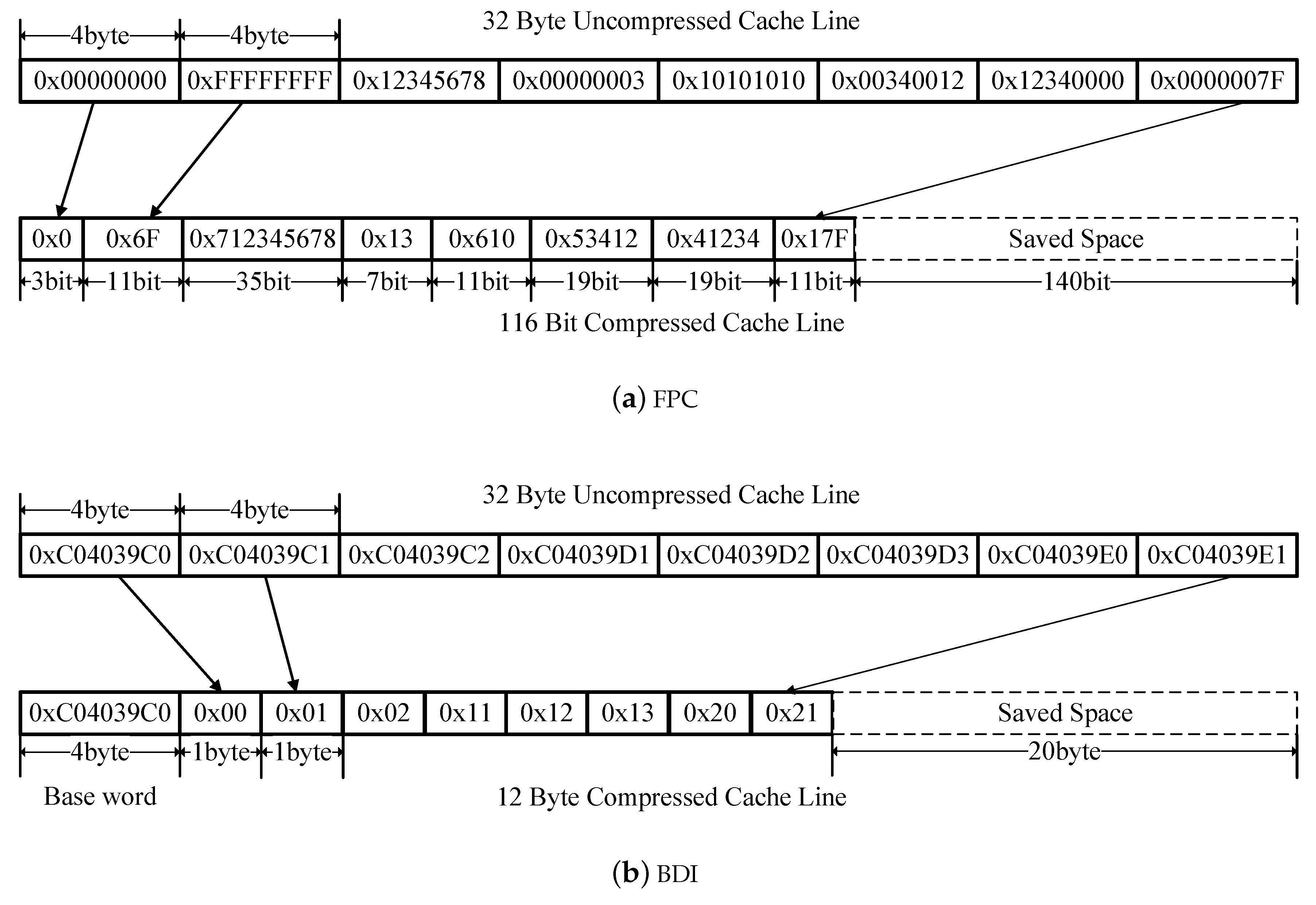

The commonly used cache line compression methods can be broadly categorized into two types. One representative approach is Frequent Pattern Compression (FPC), which compresses cache lines by matching data against a static pattern table. The core compression mechanism of FPC is illustrated in

Table 1, where each data pattern is identified by a specific prefix and encoded using a predefined scheme. For instance, the prefix 000 represents the Zero Run pattern, which is used for 4-byte zero-value data (e.g., 0x00000000). In this case, only 3 bits are required to represent the data, significantly reducing storage overhead. However, it is important to note that the compression efficiency of FPC heavily depends on the data characteristics. For scenarios where the data distribution is relatively random or lacks regularity, the compression efficiency of FPC tends to degrade.

Another widely used method is Base-Delta-Immediate (BDI) compression, which achieves compression for cache lines with a small dynamic range by utilizing a base value and a delta array. The core idea of BDI compression is that for many cache lines, the values stored exhibit a low dynamic range, meaning the differences between these values are relatively small. Therefore, these cache lines can be represented using a base value and an array of differences (i.e., delta array). The delta array stores the differences between each value in the cache line and the base value. Since these differences are typically small, fewer bytes are required to represent them, leading to effective compression. As illustrated in

Figure 1b, an original cache line contains 8 values of 4 bytes each, resulting in a total size of 32 bytes. These values exhibit a certain linear growth relationship, with relatively small differences between consecutive values. In the BDI compression scheme, the first value in the data block is selected as the base value. In this example, the base value is 0xC04039C0. The difference (delta) between each subsequent value and the base is then calculated. For instance, the difference between 0xC04039C1 and 0xC04039C0 is 0x01. Since these deltas are small, they can be represented using fewer bits. In the compressed cache line, the base value occupies 4 bytes, while each of the 8 deltas requires only 1 byte. As a result, the entire cache line is compressed to 12 bytes, saving 20 bytes of storage space. BDI compression is particularly effective for cache lines with a small dynamic range. However, for data with a large dynamic range, BDI compression may fail to achieve significant compression.

2.3. Motivation

The primary reason for the poor compression performance of FPC and BDI lies in the difficulty of a single compression method adapting effectively to diverse workloads. For instance, in workloads related to images or videos where zero values are sparse, BDI often achieves better results than FPC. Conversely, in workloads with abundant zero values, FPC typically performs better.

In workloads like lbm, where zero values are rare, FPC demonstrates suboptimal performance. Similarly, in workloads like tonto, BDI performs poorly due to the low intra-line similarity in cache lines. Furthermore, the high metadata overhead introduced by FPC contributes to its limited effectiveness. FPC performs compression at the word granularity based on static common word patterns stored in a pattern table. If a word in a block matches a pattern in the table, the block is compressed. For each compressible block, FPC assigns prefix bits (3 bits per word) based on word patterns. Consequently, FPC incurs significant metadata overhead, amounting to 3×Total Words per Block.

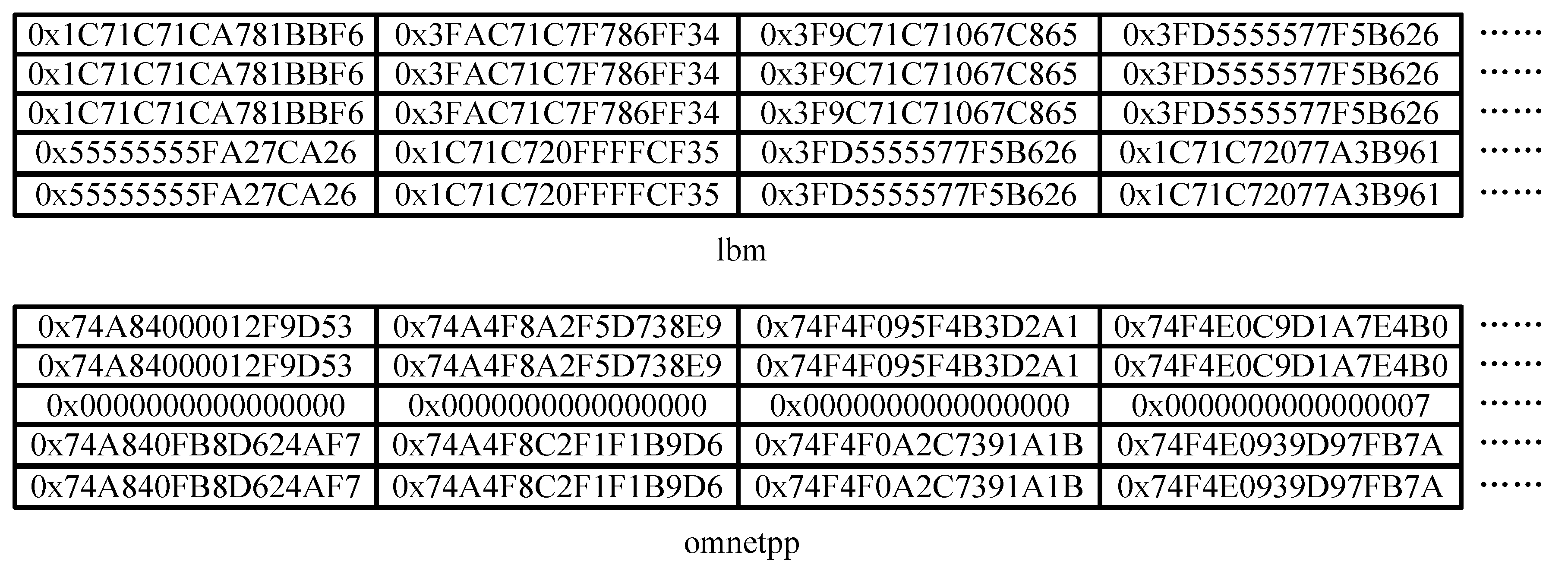

Moreover, there are a large number of duplicate cache lines in the cache memory, which further leads to the lower compression efficiency. For instance, as shown in

Figure 2, the lbm benchmark includes a substantial number of 64-bit floating-point numbers. These floating-point cache lines appear multiple times. For FPC, the low frequency of zero values in floating-point numbers limits compression effectiveness. In the case of BDI, insufficient intra-block similarity hinders the selection of effective bases and deltas. These challenges renders traditional compression techniques less effective in achieving desirable results. Developing a compression scheme that achieves both high coverage and high compression ratios across diverse workloads remains a critical challenge in the field.

Some existing studies have employed dynamic compression techniques to account for the varying data characteristics of different cache lines. DFPC adopts a two-phase approach to improve compression efficiency [

23]. In the first phase, DFPC samples the benchmark workloads using an incomplete FPC compression algorithm while collecting statistics on frequent patterns within each benchmark. This step not only provides data support for subsequent compression but also ensures that the compression strategy aligns closely with the characteristics of the application scenarios. In the second phase, DFPC leverages the frequent patterns collected during the initial phase to perform more precise compression of cache lines. Compared to traditional methods lacking flexibility and adaptability, DFPC considers the unique data characteristics of different cache lines, thereby improving the overall compression ratio. However, this approach does not fully account for inter-line redundancy within cache lines. For example, in benchmarks dominated by image or floating-point data, such as the omnetpp benchmark illustrated in

Figure 2, DFPC exhibits a decrease in compression effect. Additionally, data characteristics may differ across different execution phases of a program. Relying solely on data characteristics from the early stages of program execution may result in reduced compression ratio during later stages.

To investigate the variations in data characteristics between the early and late stages of application execution, we conducted preliminary experiments using the gem5 and NVMain simulators.

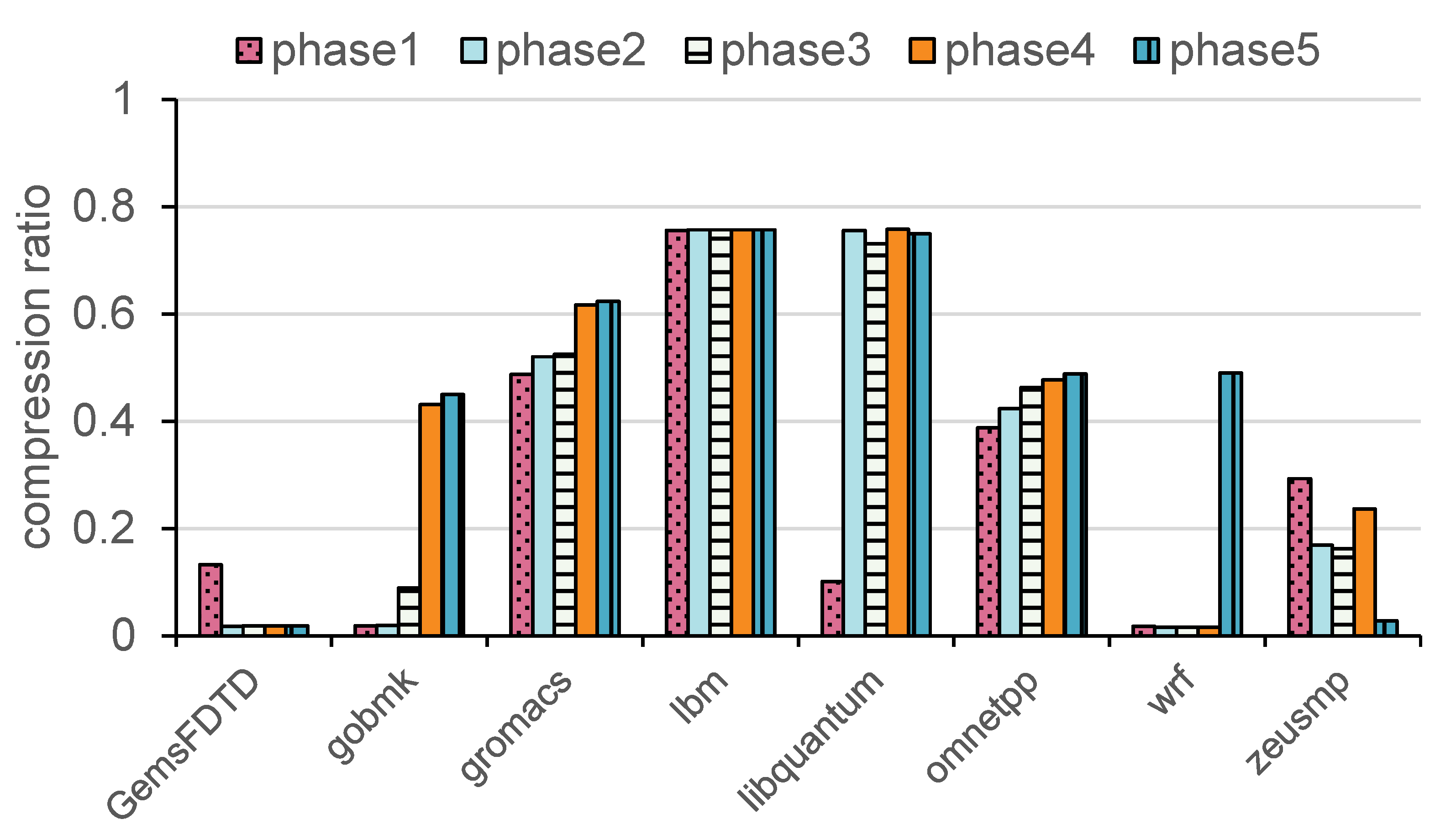

A subset of SPEC CPU2006 benchmarks was executed, running 1 billion instructions for each benchmark. Each benchmark was divided into five phases based on the number of executed instructions. We recorded the compression ratio of DFPC at different phases to determine whether the compression ratio decreases in later phases. The results are shown in

Figure 3, where the x-axis represents the different benchmarks, and the y-axis shows the compression ratio for each phase (compression ratio = compressed cache line length/original cache line length). By analyzing the experimental data from different benchmarks, we found that the DFPC algorithm exhibits a trend of gradually increasing compression ratios in the later stages of program execution, indicating that the data becomes increasingly difficult to compress. For instance, in the libquantum benchmark, the compression ratio rises from 10.14% to 75.81%, demonstrating that in the later stages, the data’s compressibility significantly decreases, and the extracted dynamic data patterns fail to adapt to the changing data characteristics.

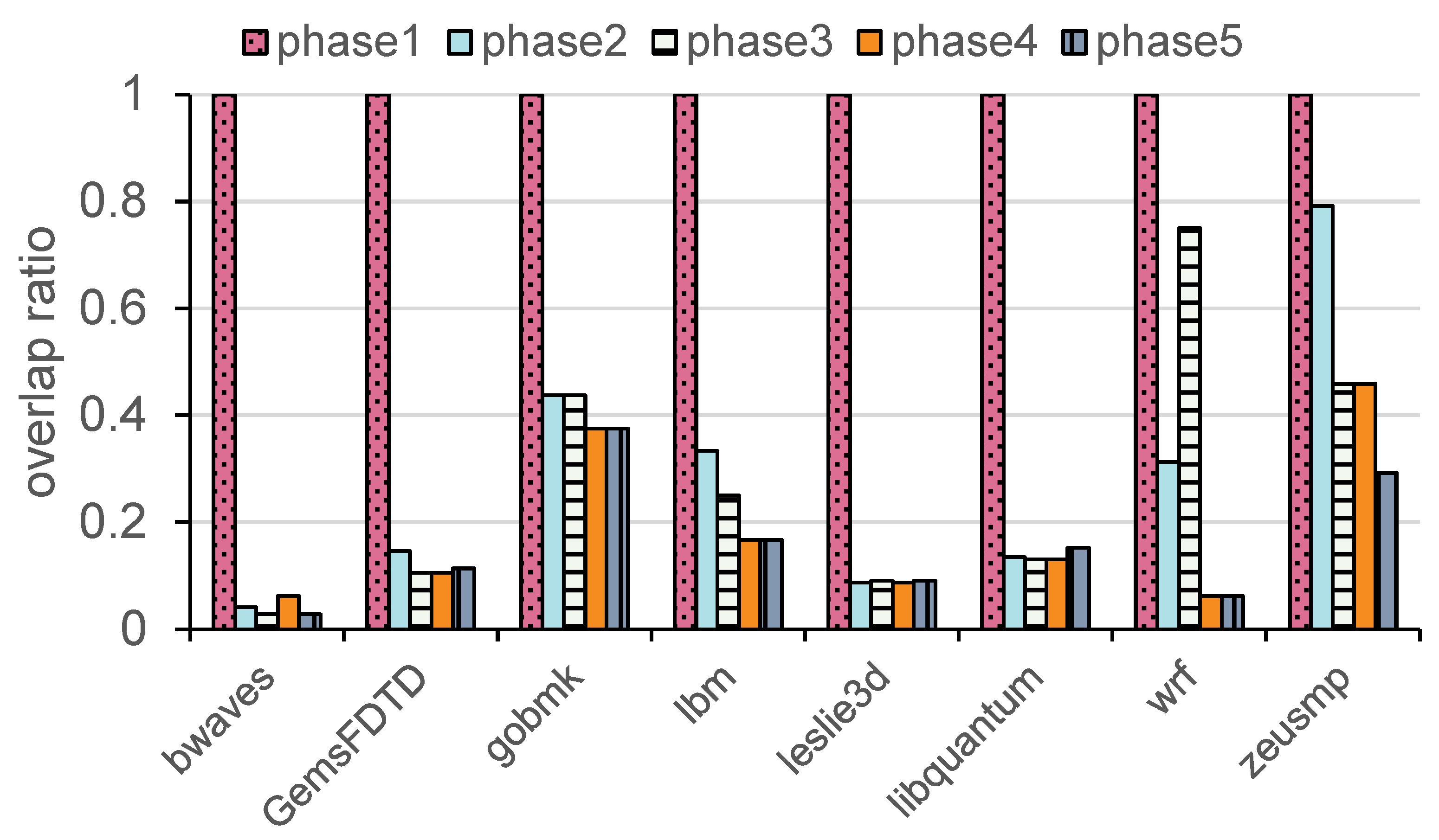

In addition to the above experiments, we collect the proportion of high-frequency words in the cache line in different execution stages. In

Figure 4, the x-axis represents the different benchmarks, while the y-axis shows the proportion of overlap between the high-frequency words in each phase and those from the first phase. From

Figure 4, it is evident that the high-frequency words generated in different phases often differ significantly from those in the first phase, with the overlap ratio consistently remaining low. For instance, in the bwaves benchmark, the overlap proportion drops to 2.7% in phase 3. In the libquantum benchmark, the overlap remains relatively low across phases, with values of 13.4% in phase 2 and 13.1% in phase 4. These low overlap ratios indicate significant changes in memory access patterns as program execution progresses.

These variations are primarily attributed to significant differences in program behavior across different execution stages. In the early stages, programs typically perform initialization tasks, such as resource allocation and loading essential data. Memory access patterns during this phase are often linear or highly repetitive, leading to high-frequency words that are predominantly related to initialization. As execution progresses into the middle and later stages, the focus shifts to core task processing, where memory access patterns become increasingly dependent on specific algorithmic logic and data characteristics. This transition results in significant changes to the high-frequency words, driven by factors such as variations in data loading strategies, compute-intensive operations, loop structures, and conditional branch distributions. Furthermore, some benchmarks may involve resource deallocation or less repetitive operations in the later stages, such as cleaning up complex data structures or performing sparse matrix computations, which further contribute to the observed variations. These results suggest that relying solely on high-frequency patterns from the early stages for compression may not adequately adapt to the evolving data characteristics during program execution. This limitation could lead to a significant reduction in compression ratio in the later phases, ultimately impacting overall performance.

We propose a compression method leveraging inter-cache-line and intra-cache-line similarity. By dynamically modifying words in the high-frequency word table, this approach ensures high coverage and compression ratios across different phases of application execution.

3. System design and implementation

This section provides a detailed introduction to the proposed DCom architecture, including its system design and read/write processes, followed by a discussion of the overhead associated with DCom.

3.1. Overview

To address the limitations of traditional compression methods, which struggle to achieve both high compression ratios and coverage ratios across different workloads, DCom introduces a dynamic architecture that adapts to varying memory access patterns. This architecture is centered around two key components: the half-word cache and the adaptive half-word table.

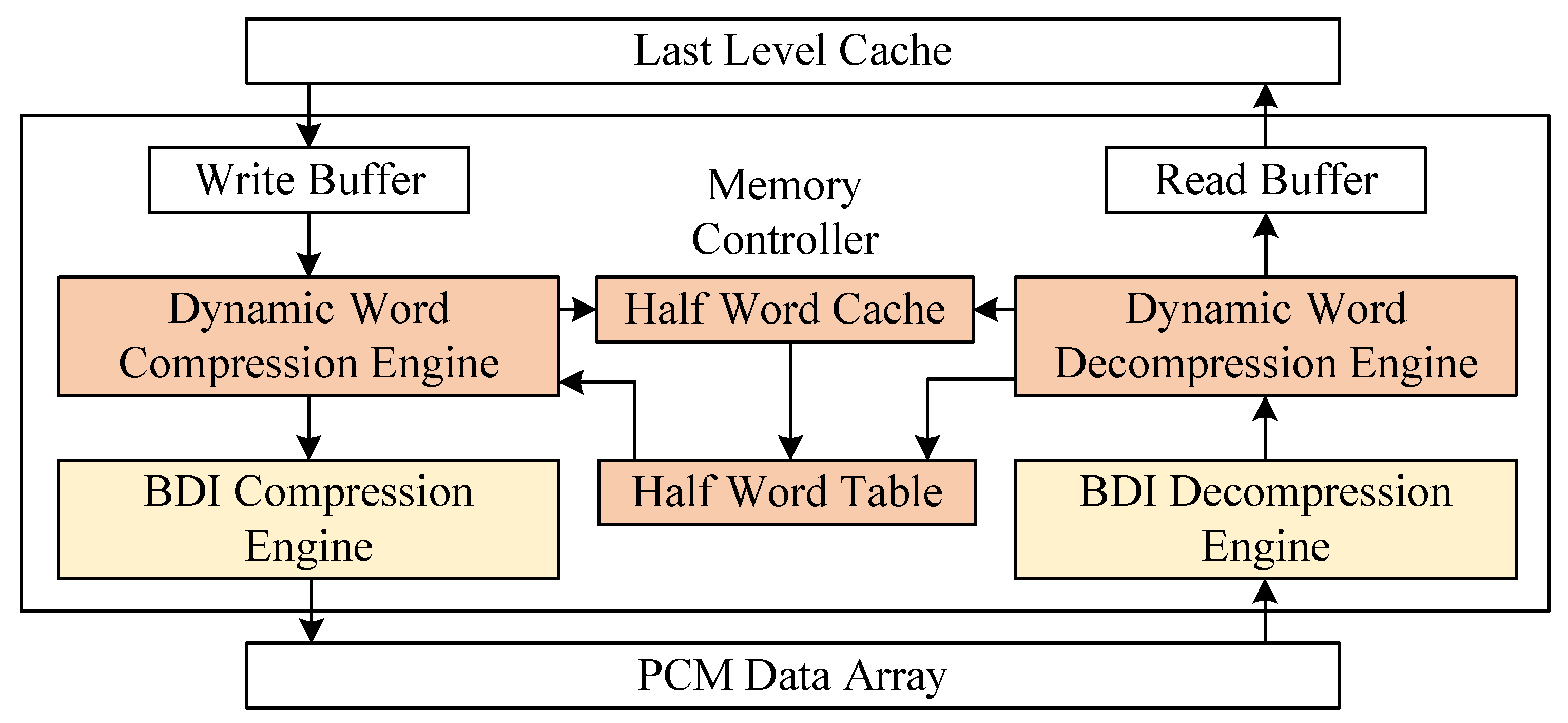

As illustrated in

Figure 5, Half-word cache employs counters for tracking counts. This cache dynamically tracks the frequency of words in memory access streams. Once the frequency of a half-word exceeds a predefined threshold T, the word is added to the adaptive half-word table. The half-word table, which can store up to 16 high-frequency half-words, is responsible for compressing these words by encoding their high bits into compact 4-bit indices, thereby achieving significant compression. Considering the diversity of workloads, DCom incorporates two parallel half-word caches to independently process 32-bit and 64-bit words. Additionally, DCom operates alongside BDI compression, which is used to handle data patterns with low inter-cache-line locality but high intra-cache-line locality. This parallel processing architecture ensures that DCom can effectively handle a wide range of memory access behaviors.

3.2. Operational Workflow

The compression and decompression workflow of DCom involves writing and reading processes, which are designed to work dynamically to minimize compression ratio and adapt to varying memory access patterns. These processes ensure that DCom not only reduces NVM writes effectively but also maintains compatibility with diverse workloads by leveraging its dynamic architecture.

During the write process, as detailed in Algorithm 1, each word in the cache line is analyzed to determine whether it matches an entry in the half-word table, which stores up to 16 high-frequency words. If a match is found, the half-word is replaced by its corresponding 4-bit index, reducing the write to the cache line. If a word is not found in the half-word table, its half-words are stored in the half-word cache, while its frequency count in the cache is incremented. When the frequency of a half-word exceeds the predefined threshold T, the system evaluates its eligibility for promotion to the half-word table. If the table has fewer than 16 entries and the half-word is not already present, the half-word is added to the table, thereby ensuring that DCom dynamically adapts to the current workload. By identifying and promoting high-frequency words over time, DCom achieves a lower compression ratio as execution progresses. Furthermore, to handle data patterns that may not exhibit inter-cache-line locality, DCom operates in parallel with BDI compression. BDI is particularly effective for compressing data with repetitive deltas across cache lines. After processing, the compressed or partially compressed data from the cache line is written to NVM.

|

Algorithm 1 Dynamic Word Compression Algorithm |

- 1:

Input: Write data array D, Old data array , Half-word cache H, Half-word table W, Threshold T

- 2:

Output: Compressed data array

- 3:

Initialize an empty array . - 4:

ifD is all elements in D are zero then

- 5:

; - 6:

Set the All-zero tag. - 7:

else - 8:

for do

- 9:

- 10:

- 11:

if and and then

- 12:

Add w to the half-word table W. - 13:

end if

- 14:

if then

- 15:

Append the index of w to . - 16:

else

- 17:

Append w to . - 18:

end if

- 19:

end for

- 20:

end if - 21:

if All-zero tag of is set to 1 then

- 22:

return . - 23:

else - 24:

Split the cache line and store it in a temporary array T. - 25:

for do

- 26:

if then

- 27:

- 28:

- 29:

end if

- 30:

if then

- 31:

Remove w from H. - 32:

Remove w from W. - 33:

end if

- 34:

end for

- 35:

end if - 36:

return. |

Additionally, before performing a DCW write operation [

24] (Data Comparison Write, First, the old data is read, and the new and old data are compared to avoid redundant writes), DCom collects statistics on the old data to ensure the accuracy of the compression process. For each old cache line marked for compression using DCom, the system retrieves the corresponding half-word from the half-word table and decrements its frequency count in the half-word cache. If the frequency count reaches zero, the word is removed from the half-word cache and, if present, from the half-word table. This systematic clearing of outdated words prevents stale entries from occupying space in the half-word table, ensuring its adaptability and responsiveness to dynamically changing workload patterns.

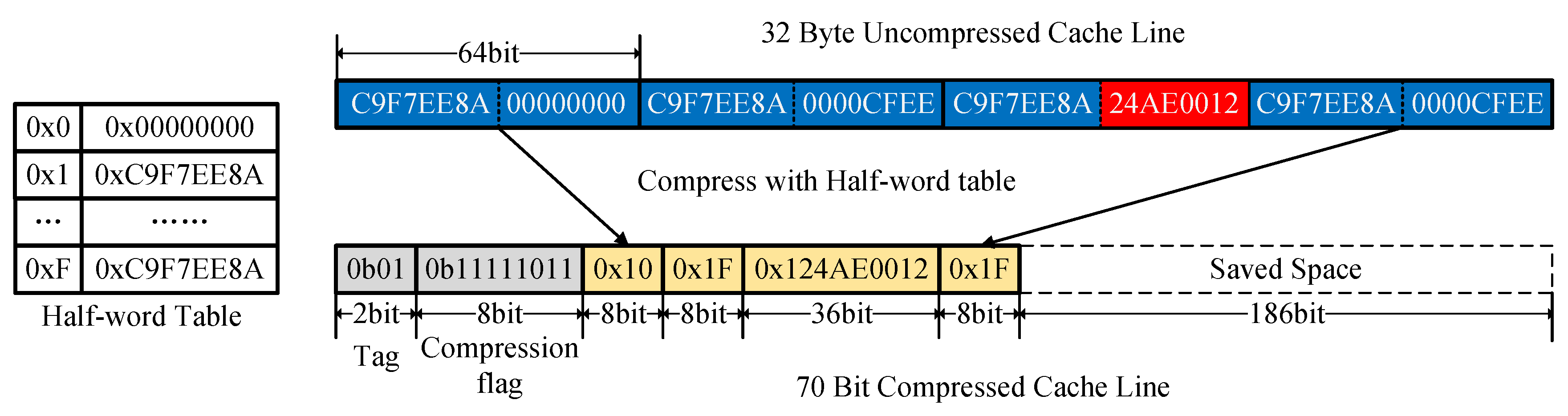

As shown in

Figure 6, an uncompressed cache line consists of 32 bytes. Each unique 4-byte word in the cache line is checked against the entries in the half-word table. If a match is found, the word is replaced with its corresponding index. In this example, the half-word table contains high-frequency words, such as C9F7EE8A and 0000CFEE, allowing these frequently occurring values to be represented more compactly. After compression, the original 32-byte cache line is transformed into a 70-bit compressed cache line, resulting in significant storage savings. This process demonstrates the efficiency of the half-word table in reducing redundant data storage.

In the read process, as detailed in Algorithm 2, compressed data are retrieved from memory along with its associated tag, which indicates whether DCom or BDI was used for compression. Based on the tag, the system selects the appropriate decompression method. For DCom-compressed data, indices in the cache line are matched with entries in the half-word table, and each index is replaced with its corresponding high-frequency half-word to reconstruct the original data. For BDI-compressed data, the base value and deltas are used to restore the original words. Finally, the decompressed data are transferred to the Last-Level Cache (LLC) for subsequent operations.

|

Algorithm 2 Dynamic Word Decompression Algorithm |

- 1:

Input: Compressed data array D, Half-word table W

- 2:

Output: Decompressed data array

- 3:

Initialize an empty array . - 4:

if All-zero tag is set then

- 5:

return . - 6:

end if - 7:

Split the cache line and store it in a temporary array T. - 8:

fordo

- 9:

if then

- 10:

Append the original word of T[i] to . - 11:

else

- 12:

Append to . - 13:

end if

- 14:

end for - 15:

return. |

3.3. Discussion and Overhead Analysis

Due to the dynamic nature of DCom, certain overheads are introduced. The primary sources of overhead include the maintenance of the half-word cache and the adaptive half-word table. Compared to static methods, the half-word cache introduces some additional hardware overhead. Specifically, the half-word cache utilizes a set of counters for tracking counts. We employ 1024 counters to monitor high-frequency words, requiring 8 KB (1024 counters × 8 Bytes (64-bit int)) space. When the counters are exhausted, one counter below the threshold is randomly replaced. The half-word table stores only the 32-bit value. Since the adaptive half-word table only stores 16 entries, its memory overhead is almost negligible.

In addition to the cache and table, other sources of overhead include compression tag and compression flag and all-zero tag. The compression tag is fixed at two bits, where "00" indicates no compression, "01" represents compression using 64-bit DCom, "10" represents compression using 32-bit DCom, and "11" represents compression using BDI. The compression flag indicates whether a half-word has been compressed. For a 64-bit application cache line, the bitmap requires 16 bits, whereas for a 32-bit application cache line, it requires 32 bits. Additionally, an all-zero tag is used to indicate whether the entire cache line consists of zeros and requires one bit.

Regarding computational overhead, the collection of statistics for old data occurs during the DCW stage, where DCW reduces writes by comparing old and new data. As a result, this overhead is nearly negligible. In the memory controller, the average compression time overhead is approximately a few cycles [

25]. In Section IV, we define the access latency as three cycles for compression and two cycles for decompression.

4. Evaluation

In this section, we first present the experimental setup. Then, we explain the results related to compression ratio and lifetime, validating the effectiveness of our experiments. Finally, we provide the results for read/write latency.

4.1. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the effectiveness of the DCom method, we performed a series of experiments on a platform built using gem5 [

26] and NVMain [

27]. gem5 is a versatile simulator widely used for research in computer system architecture, offering support for both system-level architecture and processor microarchitecture. NVMain is a cycle-accurate simulator for main memory, capable of modeling emerging non-volatile memory technologies at the architectural level. In our experiments, gem5 is employed to simulate the CPU along with the two-level cache hierarchy (L1 and L2), while NVMain is used to model Phase Change Memory (PCM) as the primary memory. The cache line size is configured to 512 bits. Through experiments, we selected 200 as the threshold for DCom to insert entries into the half-word table. The other detailed configuration is shown in

Table 2.

We use the SPEC CPU 2006 benchmark suite for evaluation, running each benchmark for 1 billion instructions to ensure a sufficient number of memory accesses. SPEC CPU 2006 is a standardized benchmark suite to evaluate the compute-intensive performance of CPUs through a diverse set of real-world workloads, spanning both integer and floating-point operations. The DCom method is compared against FPC, BDI, and DFPC. FPC primarily reduces write operations by leveraging static patterns, while BDI minimizes writes by compressing data based on the similarity of words within a block. DFPC dynamically collects zero-pattern distributions in cache lines and generates a pattern table for each benchmark at runtime. All methods enable DCW by default during writes to NVM.

4.2. Results of Compression Ratio

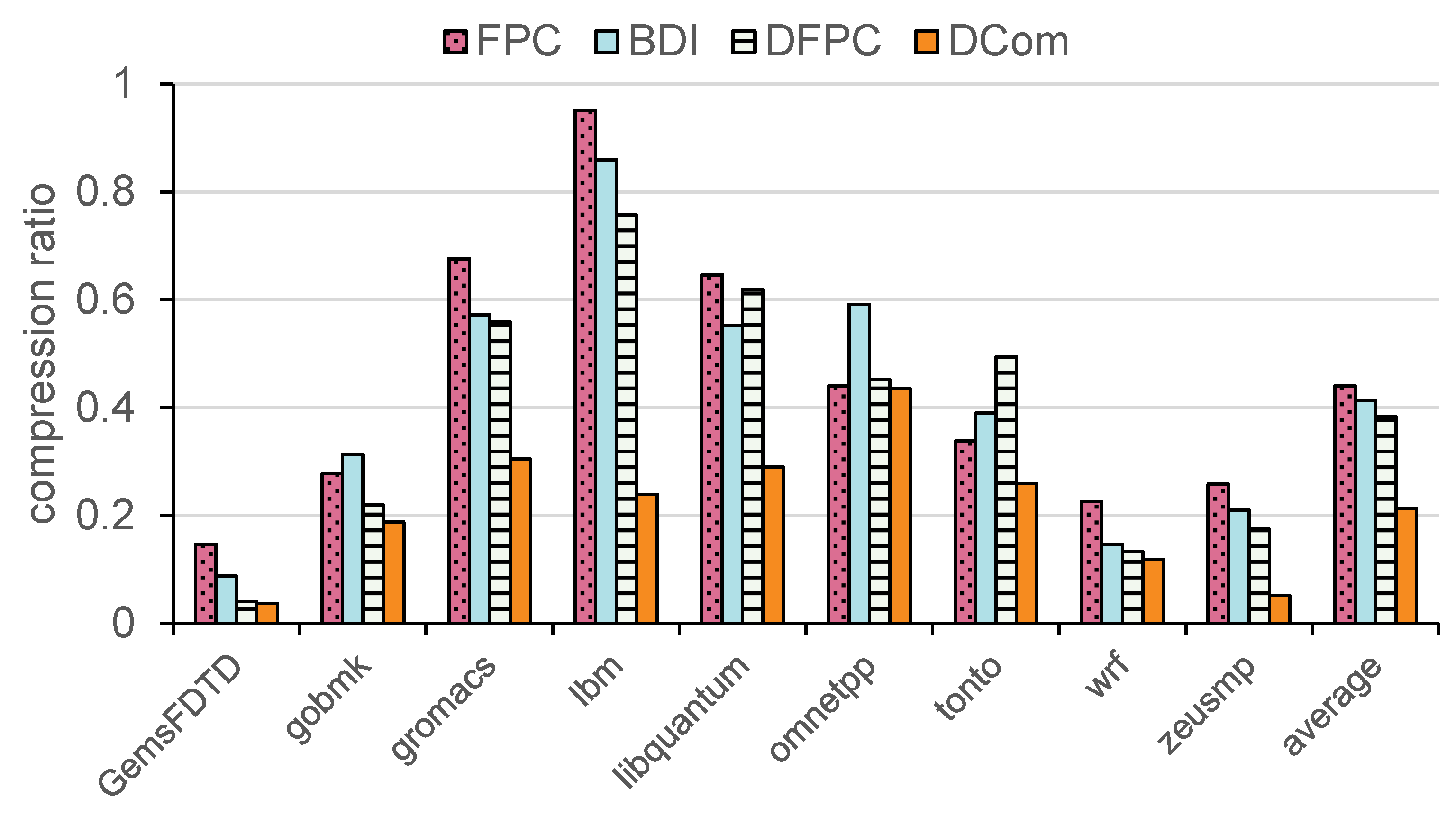

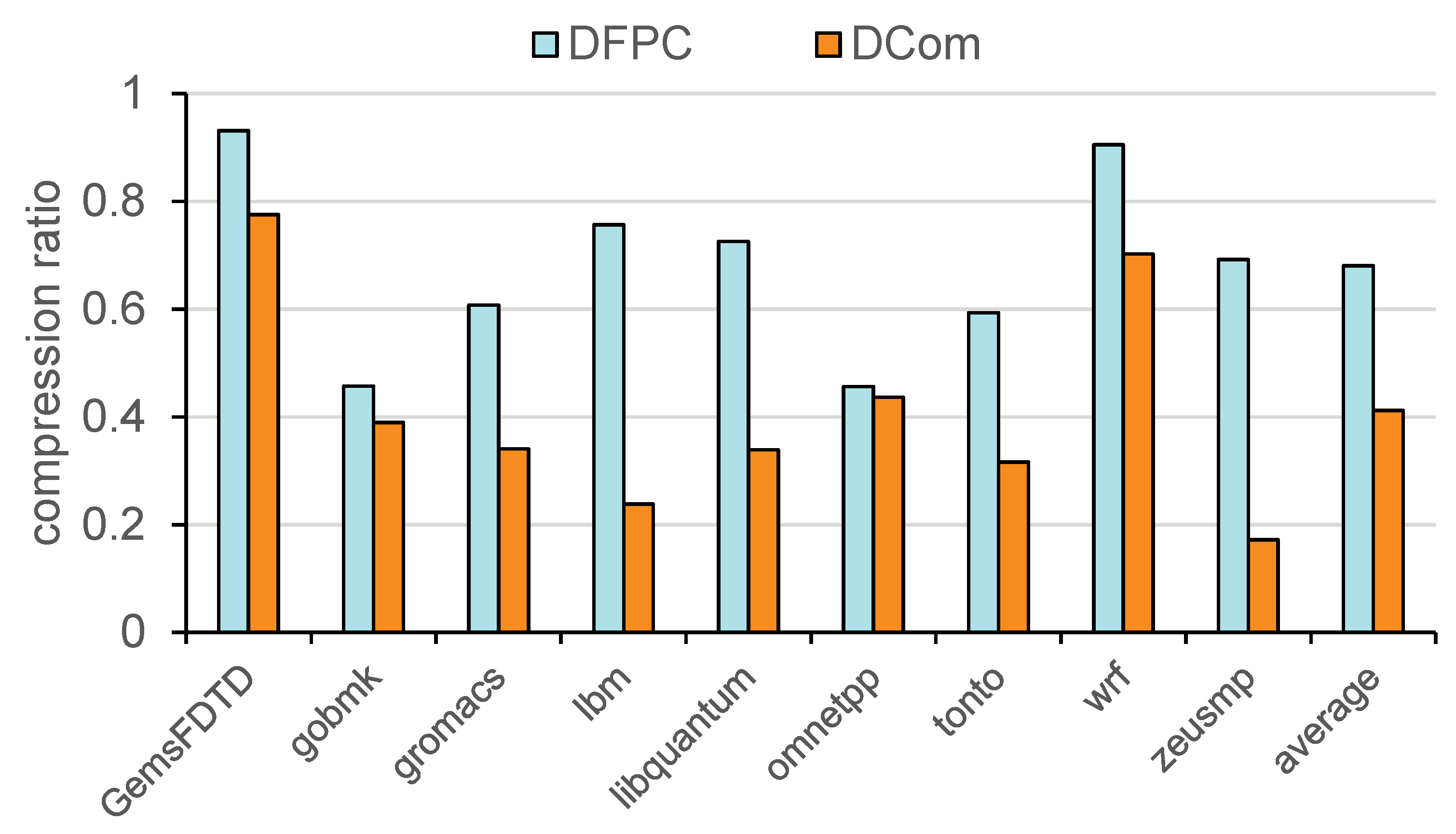

The basic compression ratios of DCom and other methods, including BDI, FPC, and DFPC, are summarized in

Figure 7. DCom achieves an average compression rate of 21.37%, significantly outperforming DFPC (36.32%), FPC (43.99%), and BDI (41.33%). This improvement highlights DCom’s ability to dynamically adapt to high-frequency words within cache lines, enabling more efficient memory utilization compared to traditional methods. However, the advantage of DCom over DFPC is not obvious in some benchmarks. This difference is primarily attributed to the high proportion of all-zero cache lines in certain benchmarks, such as wrf and GemsFDTD, which results in similar compression ratios between the two methods. While DCom effectively compresses these all-zero lines, its relative benefit over DFPC diminishes, as DFPC also achieves near-optimal compression for such data patterns.

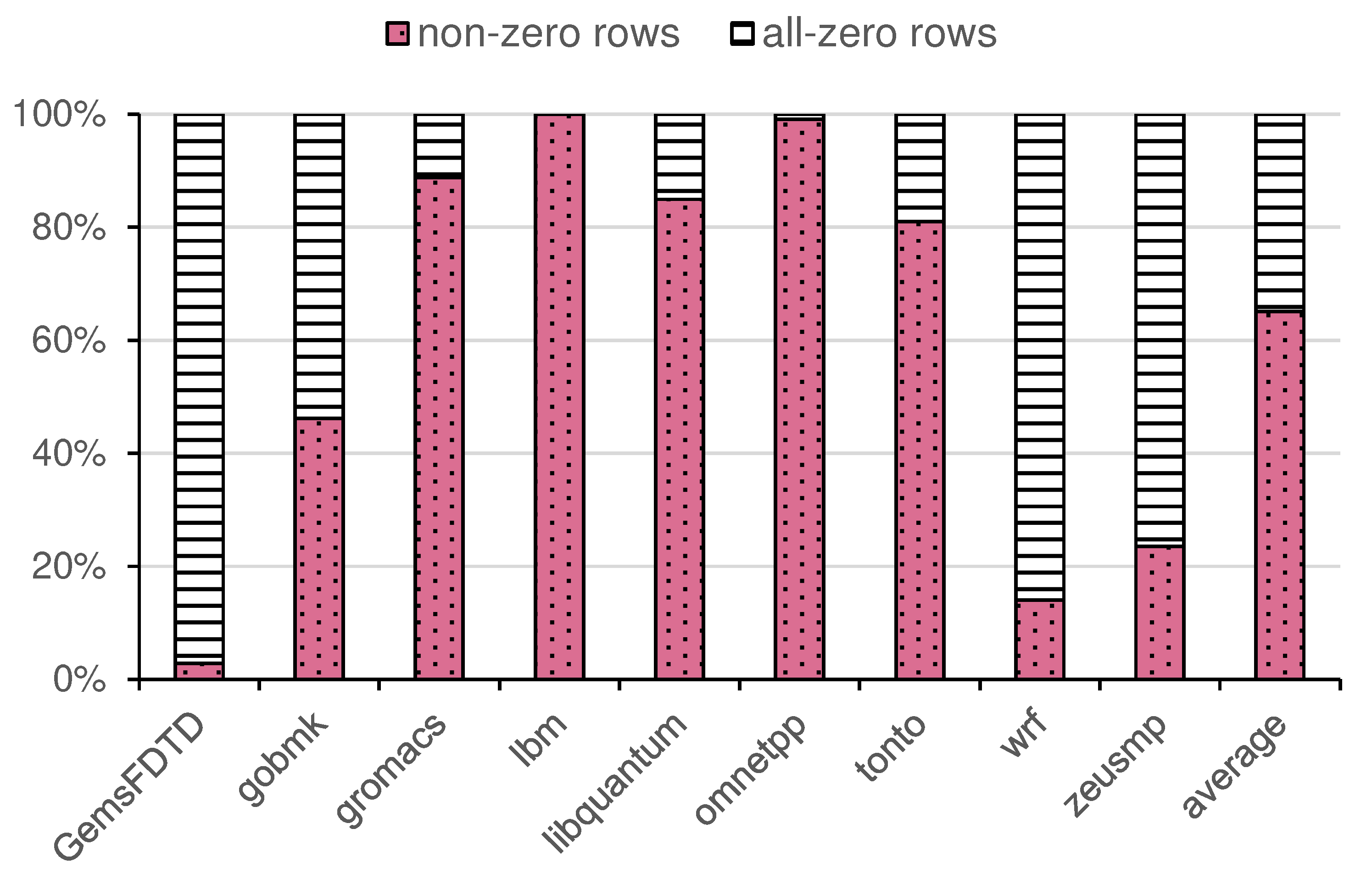

To better understand the impact of all-zero cache lines,

Figure 8 presents the proportion of non-zero and all-zero cache lines for each benchmark. Benchmarks like wrf contain a high number of all-zero cache lines (e.g., GemsFDTD contains about 90% of all-zero rows, while wrf contains about 80% of all-zero rows), which significantly contributes to their high overall compression ratio. Conversely, benchmarks such as lbm and libquantum exhibit a much lower proportion of all-zero lines, highlighting differences in workload characteristics. We believe that the excessive presence of all-zero lines dilutes the advantages brought by DCom’s compression.

In order to show the compression capability of our compression method for non-zero rows, we evaluated its compression rate on non-zero cache lines separately. The results, presented in

Figure 9, reveal a more pronounced improvement. For non-zero cache lines, DCom achieves an average compression ratio of 41.23%, which is lower than the 68.06% achieved by DFPC. This scenario removes the impact of all-zero lines, highlighting DCom’s adaptive mechanism for identifying and compressing high-frequency words within non-zero data. Benchmarks with fewer all-zero lines, such as lbm and libquantum, demonstrate more substantial benefits from DCom, where its dynamic adaptability ensures more efficient compression of complex, non-repetitive patterns. By focusing on non-zero data, DCom shows its strength in handling diverse workloads and dynamic patterns, validating its design as an adaptive and workload-responsive compression method.

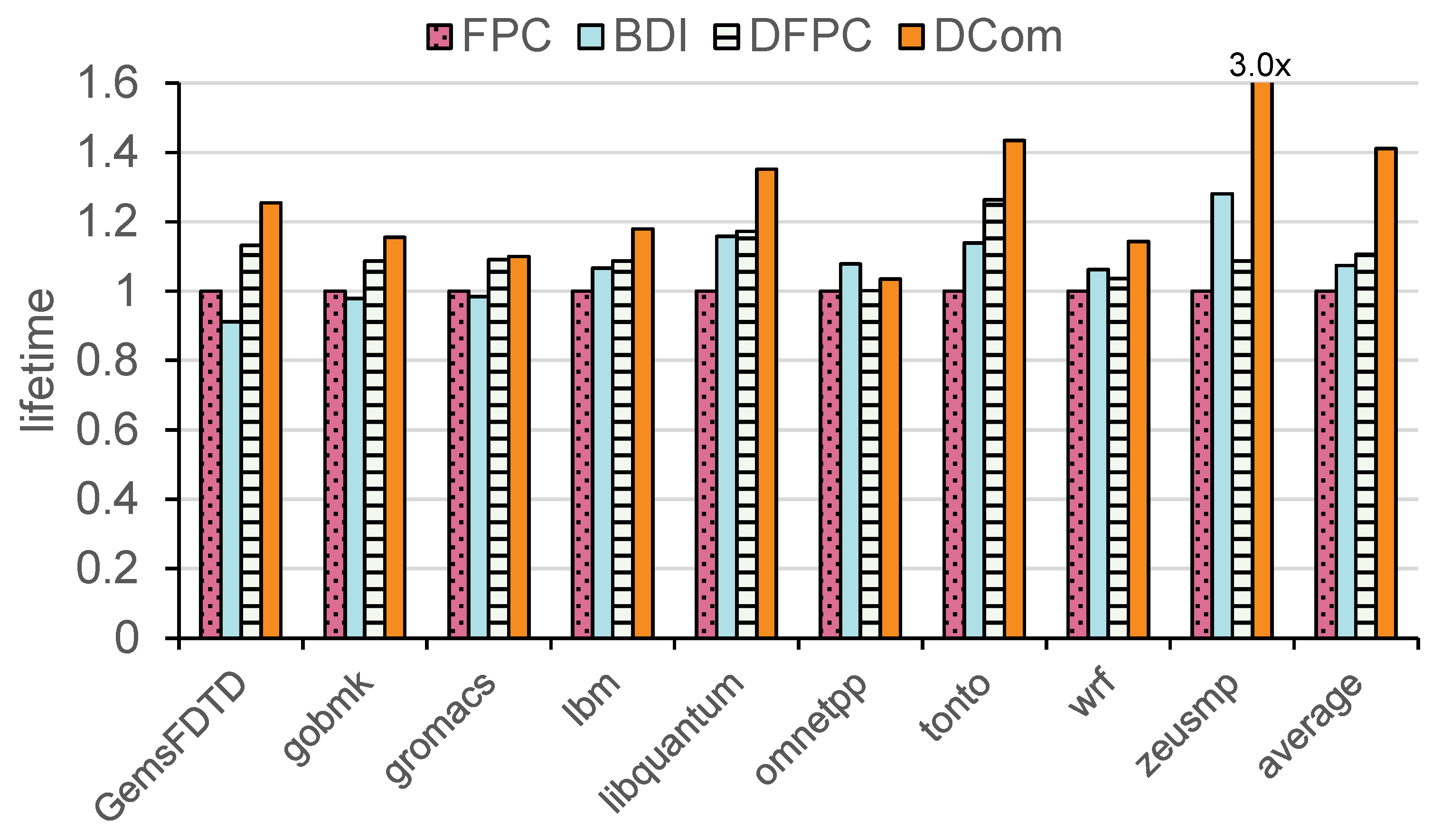

4.3. Results of lifetime

The lifetime of NVM is limited by the number of bit flips it can endure before cells fail. Reducing bit flips in NVM is essential for minimizing cell failures and maximizing its lifetime. For simplicity in evaluating lifetime, we assume wear leveling has been implemented to ensure uniform wear across all cells, and no error correction techniques are employed. Under these assumptions, the lifetime of NVM is inversely proportional to the total number of bit flips. Equation (

1) illustrates the relationship between lifetime and bit flips, where

C is a constant that remains identical across different strategies:

Reducing the total number of bit flips can significantly extend the lifetime of NVM. All methods were evaluated with DCW and FNW methods enabled. The experimental results demonstrate that after normalizing the results to FPC, the lifetime improvements achieved by BDI, DFPC, and DCom are 8.1%, 10.6%, and 41.1%, respectively.

Figure 10 presents a comparison of experimental data under various workloads. Compared to the compression ratio, DCom also performs well under DCW. However, the improvement in lifetime of DFPC is not significant compared to BDI and FPC. We think this may be due to the large difference between new and old data caused by DFPC after using DCW. The compression of DFPC disrupts some locality, thereby partially reducing its compression ratio advantage.

4.4. Results of latency

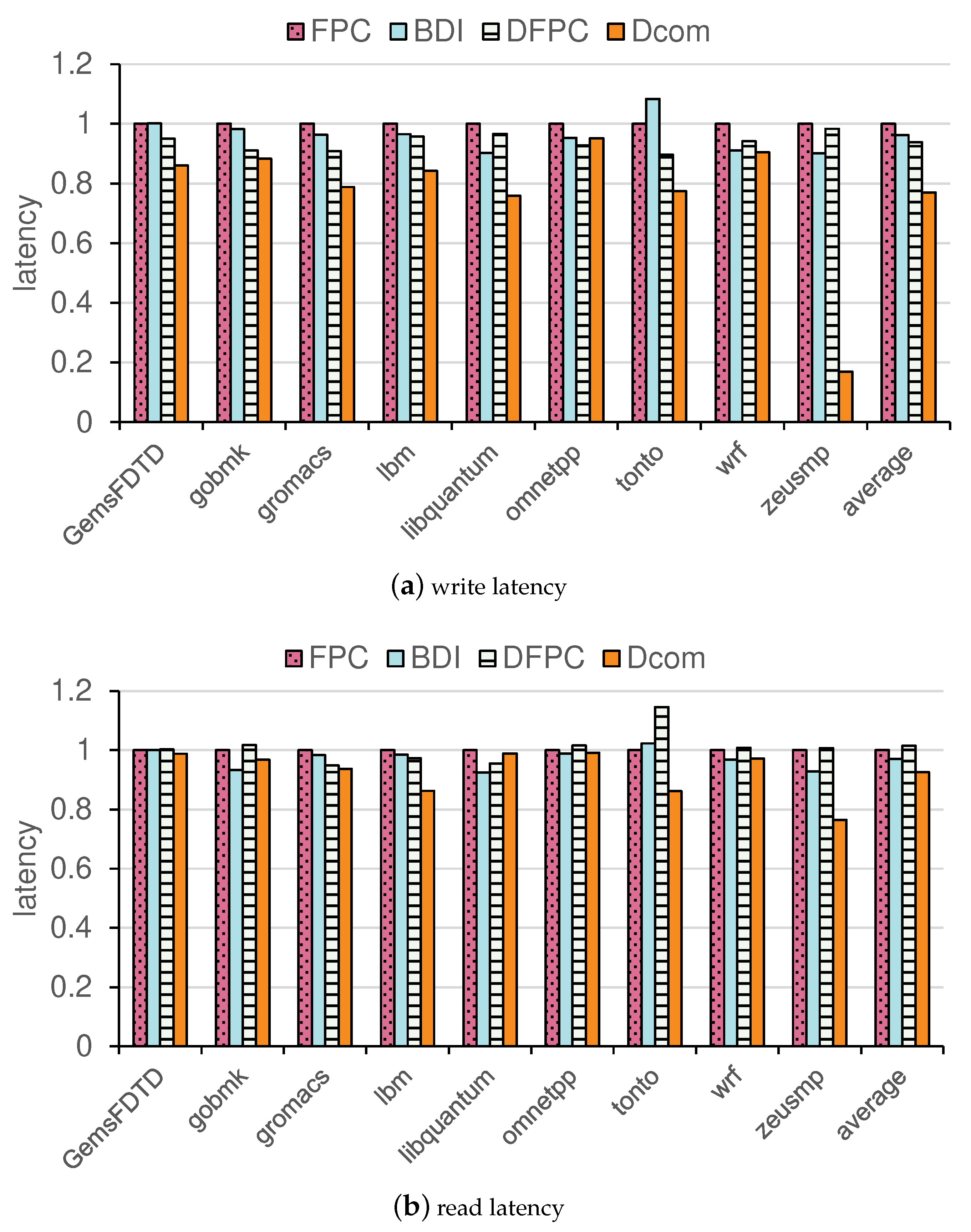

To evaluate the performance of DCom in terms of latency, we measured both write and read latencies across various benchmarks and compared them with FPC, BDI, and DFPC.

Figure 11a summarizes the write latency results, where DCom demonstrates an average write latency of 77.0% relative to FPC, significantly lower than DFPC (93.8%) and BDI (96.2%). This indicates that DCom reduces the write latency by 23.0% compared to FPC and 17.6% compared to DFPC. Notably, benchmarks such as zeusmp and tonto show the most significant improvement, where DCom achieves 16.9% and 77.4% relative to FPC, compared to DFPC’s 98.3% and 89.7%, respectively. These results highlight DCom’s ability to effectively reduce write latency, especially for benchmarks with complex high-frequency word variations The reduction in write latency can be attributed to the compression, which reduces the number of bits that need to be written. By compressing data before write operations, DCom not only minimizes the read latency of the old data but also decreases the total number of words required for each write operation.

The read latency results, presented in

Figure 11b, show a similar trend. DCom achieves an average read latency of 92.6% relative to FPC, which is lower than DFPC (101.5%) and BDI (97.0%). This represents a 7.4% reduction in read latency compared to FPC and an 8.8% reduction compared to DFPC.

5. Related Works

In recent years, research focused on improving the performance and durability of NVM has gained significant attention, especially considering its potential to replace traditional DRAM. One of the main challenges of NVM is its limited write durability, which can lead to system failure due to excessive write operations. To address this, various techniques have been proposed, mainly focusing on reducing the write frequency and extending the lifetime of NVM.

For example, compression techniques are widely used to reduce the amount of data written to memory. Frequent Pattern Compression (FPC) [

14], which compresses data cache lines with predefined pattern tables, can reduce storage overhead and is effective for workloads with simple data patterns. However, FPC performs poorly in complex workloads and introduces significant metadata overhead. Base-Differential Compression (BDI) [

15] represents cache lines using base values and difference arrays, making it suitable for workloads with high locality, but it struggles with complex data types (e.g., floating-point or sparse data). Additionally, Dynamic Frequent Pattern Compression (DFPC) [

23] attempts to overcome these limitations by dynamically adjusting compression strategies based on the observed frequencies during the early execution stages, but it still relies on static early-stage information and cannot adapt to changes in access patterns later in the program’s execution. Dusser et al. [

30] proposed Zero-Content Augmented (ZCA) caching, which uses address tags and valid bits to represent empty cache lines. ZCA caches zero lines separately, reducing the space required for these lines. Liu et al. [

8] introduced Zero Deduplication with Frequent Value Compression (ZD-FVC), which encodes zero and non-zero words with small tags to minimize space usage. ZD-FVC works well for lines with many zeros but incurs overhead when processing non-zero words due to extra tag bits.

In addition, research has also focused on using encoding techniques to reduce NVM write operations. Palangappa et al. [

25] proposed Compression Expansion Coding (CompEx), which integrates static compression techniques such as FPC/BDI with expansion encoding to reduce NVM write latency, energy consumption, and extend the NVM lifetime. Xu et al. [

29] further built on CompEx and introduced COE, which uses the space saved from data compression as a marker for selecting the optimal encoding scheme to minimize bit writes.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed DCom, a dynamic compression algorithm aimed at improving the efficiency of Non-Volatile Memory by reducing write operations and enhancing its lifetime. DCom leverages a dynamic table to track high-frequency words in cache lines, updating the table based on word frequency to maximize compression ratio across different execution phases. This approach effectively addresses the challenges posed by the limited write endurance of NVM, improving both the compression ratio and lifetime compared to existing methods such as FPC and BDI. We implemented DCom on the gem5 and NVMain simulators and evaluated its lifetime and performance across a range of benchmark workloads. The experimental results show that DCom reduces NVM writes significantly and improves the lifetime of NVM without affecting system performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.D.; methodology, J.W. and Z.Y.; software, Z.Y.; validation, Z.Y.; formal analysis, Z.Y.; investigation, Z.Y.; resources, J.W.; data curation, Z.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.W. and Y.D.; visualization, Z.Y.; supervision, Y.D. and J.W.; project administration, Y.D. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reinsel, D.; Gantz, J.; Rydning, J. Data age 2025: the digitization of the world from edge to core. IDC white paper 2018, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, H.; Patel, M.; Kim, J.S.; Yaglikci, A.G.; Vijaykumar, N.; Ghiasi, N.M.; Ghose, S.; Mutlu, O. Crow: A low-cost substrate for improving dram performance, energy efficiency, and reliability. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 46th International Symposium on Computer Architecture; 2019; pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.C.; Sherwood, T.; Chong, F.T.; Li, Y. Protecting page tables from rowhammer attacks using monotonic pointers in dram true-cells. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems; 2019; pp. 645–657. [Google Scholar]

- Rashidi, S.; Jalili, M.; Sarbazi-Azad, H. A survey on pcm lifetime enhancement schemes. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2019, 52, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Jiang, D.J.; Xiong, J.; Sun, N.H. A survey of phase change memory systems. Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2015, 30, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhobza, J.; Rubini, S.; Chen, R.; Shao, Z. Emerging NVM: A survey on architectural integration and research challenges. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems (TODAES) 2017, 23, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinaga, H.; Shima, H. Resistive random access memory (ReRAM) based on metal oxides. Proceedings of the IEEE 2010, 98, 2237–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ye, Y.; Liao, X.; Jin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, W.; He, B. Space-oblivious compression and wear leveling for non-volatile main memories. In Proceedings of the Proc. the 36th International Conference on Massive Storage Systems and Technology; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.; Mei, Y.; Huang, L. Quail: Using nvm write monitor to enable transparent wear-leveling. Journal of Systems Architecture 2020, 102, 101658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakert, C.; Chen, K.H.; Genssler, P.R.; von der Brüggen, G.; Bauer, L.; Amrouch, H.; Chen, J.J.; Henkel, J. Softwear: Software-only in-memory wear-leveling for non-volatile main memory. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2004.03244 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D.; Liu, W. Wear-aware memory management scheme for balancing lifetime and performance of multiple NVM slots. In Proceedings of the 2019 35th Symposium on Mass Storage Systems and Technologies (MSST); IEEE, 2019; pp. 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.; Lee, H. Flip-N-Write: A simple deterministic technique to improve PRAM write performance, energy and endurance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 42nd Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture; 2009; pp. 347–357. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobvitz, A.N.; Calderbank, R.; Sorin, D.J. Coset coding to extend the lifetime of memory. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 19th International Symposium on High Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA); IEEE, 2013; pp. 222–233. [Google Scholar]

- Alameldeen, A. Frequent Pattern Compression: A Significance-Based Compression Scheme for L2 Caches. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pekhimenko, G.; Seshadri, V.; Mutlu, O.; Gibbons, P.B.; Kozuch, M.A.; Mowry, T.C. Base-delta-immediate compression: Practical data compression for on-chip caches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 21st international conference on Parallel architectures and compilation techniques; 2012; pp. 377–388. [Google Scholar]

- Angerd, A.; Arelakis, A.; Spiliopoulos, V.; Sintorn, E.; Stenström, P. GBDI: Going beyond base-delta-immediate compression with global bases. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA); IEEE, 2022; pp. 1115–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.C.; Zhou, P.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Ipek, E.; Mutlu, O.; Burger, D. Phase-change technology and the future of main memory. IEEE micro 2010, 30, 143–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, G.; Shu, J. Protect non-volatile memory from wear-out attack based on timing difference of row buffer hit/miss. In Proceedings of the Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), 2017; IEEE, 2017; pp. 1623–1626. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, M.K.A.; Gurumurthi, S.; Rajendran, B. Phase change memory: From devices to systems; Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2012; Vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, P.; Hua, Y. A write-friendly hashing scheme for non-volatile memory systems. In Proceedings of the Proc. MSST; 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, M.K.; Srinivasan, V.; Rivers, J.A. Scalable high performance main memory system using phase-change memory technology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th annual international symposium on Computer architecture; 2009; pp. 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gupta, R. Frequent value compression in data caches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 33rd annual ACM/IEEE international symposium on Microarchitecture; 2000; pp. 258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Hua, Y.; Zuo, P. DFPC: A dynamic frequent pattern compression scheme in NVM-based main memory. In Proceedings of the 2018 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE); IEEE, 2018; pp. 1622–1627. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.D.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, J.; Lee, S.Y.; Yu, B.G. A low power phase-change random access memory using a data-comparison write scheme. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS); IEEE, 2007; pp. 3014–3017. [Google Scholar]

- Palangappa, P.M.; Mohanram, K. Compex++ compression-expansion coding for energy, latency, and lifetime improvements in mlc/tlc nvms. ACM Transactions on Architecture and Code Optimization (TACO) 2017, 14, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe-Power, J.; Ahmad, A.M.; Akram, A.; Alian, M.; Amslinger, R.; Andreozzi, M.; Armejach, A.; Asmussen, N.; Beckmann, B.; Bharadwaj, S.; et al. The gem5 simulator: Version 20.0+. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2007.03152 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Poremba, M.; Zhang, T.; Xie, Y. Nvmain 2.0: A user-friendly memory simulator to model (non-) volatile memory systems. IEEE Computer Architecture Letters 2015, 14, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Feng, D.; Hua, Y.; Tong, W.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Xu, G.; Chen, Y. Adaptive granularity encoding for energy-efficient non-volatile main memory. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 56th Annual Design Automation Conference 2019; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Feng, D.; Hua, Y.; Tong, W.; Liu, J.; Li, C. Extending the lifetime of NVMs with compression. In Proceedings of the 2018 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE); IEEE, 2018; pp. 1604–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Dusser, J.; Piquet, T.; Seznec, A. Zero-content augmented caches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Supercomputing; 2009; pp. 46–55. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).