1. Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is an intractable cancer with a poor prognosis, the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in Japan [

1,

2]. In recent years, surveillance based on known risk factors (e.g., family history, diabetes mellitus, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, chronic pancreatitis, and obesity) and identification of imaging features of early PC [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] have facilitated early detection and improved prognosis [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Improved chemotherapy [

20,

21,

22] and adjuvant therapy in combination with surgery have also improved prognosis [

23,

24,

25,

26].

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection began to spread in December 2019 and eventually became a pandemic [

27]. The mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 have played a major role in controlling the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [

28]. In Japan, two mRNA vaccines, i.e., BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech, New York, NY, USA) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna, Cambridge, MA, USA), were approved in February and May 2021, respectively [

29,

30]. A booster vaccination (third vaccination dose) was initiated for healthcare workers in December 2021 and for the general population in January 2022. In Japan, the total number of vaccinations exceeds 400 million, with a two-dose vaccination rate of 79.8% and a three-dose vaccination rate of 67.3%, and the number of people who received more than four doses exceeds 130 million [

31].

The mRNA vaccine is a new type of vaccine in which synthetic mRNA molecules containing the coding sequence necessary to construct the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein are encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles to enable mRNA delivery to cells [

32,

33], resulting in the production of SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen and subsequent induction of neutralizing antibodies [

34]. While immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) is the main and most abundantly induced immune factor after vaccination [

35,

36], IgG4 level also increases with repeated vaccination over a short period [

37]. Prolonged exposure to the same antigen induces a class switch of B lymphocytes to produce IgG4, resulting in a decrease in fragment crystallizable (Fc) receptor-mediated effector functions, including antibody-dependent cell phagocytosis and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity against cancer, ultimately leading to immune evasion of cancer [

38,

39]. In PC, the total serum IgG4 level is mildly elevated (<2 folds) in approximately 10% of the patients, with only 1% exceeding 280 mg/dL [

40]. Additionally, a high degree of IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration, as revealed by pathological examination after resection, is associated with poor prognosis [

41]. Several studies have reported the association of increased IgG4 level with poor prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer, but not in PC [

39,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Foxp3-positive regulatory T cells (Treg) also play an important role in the IgG4 response and may lead to poor prognosis through immune evasion of cancer [

45,

46].

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination and prognosis in patients with PC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

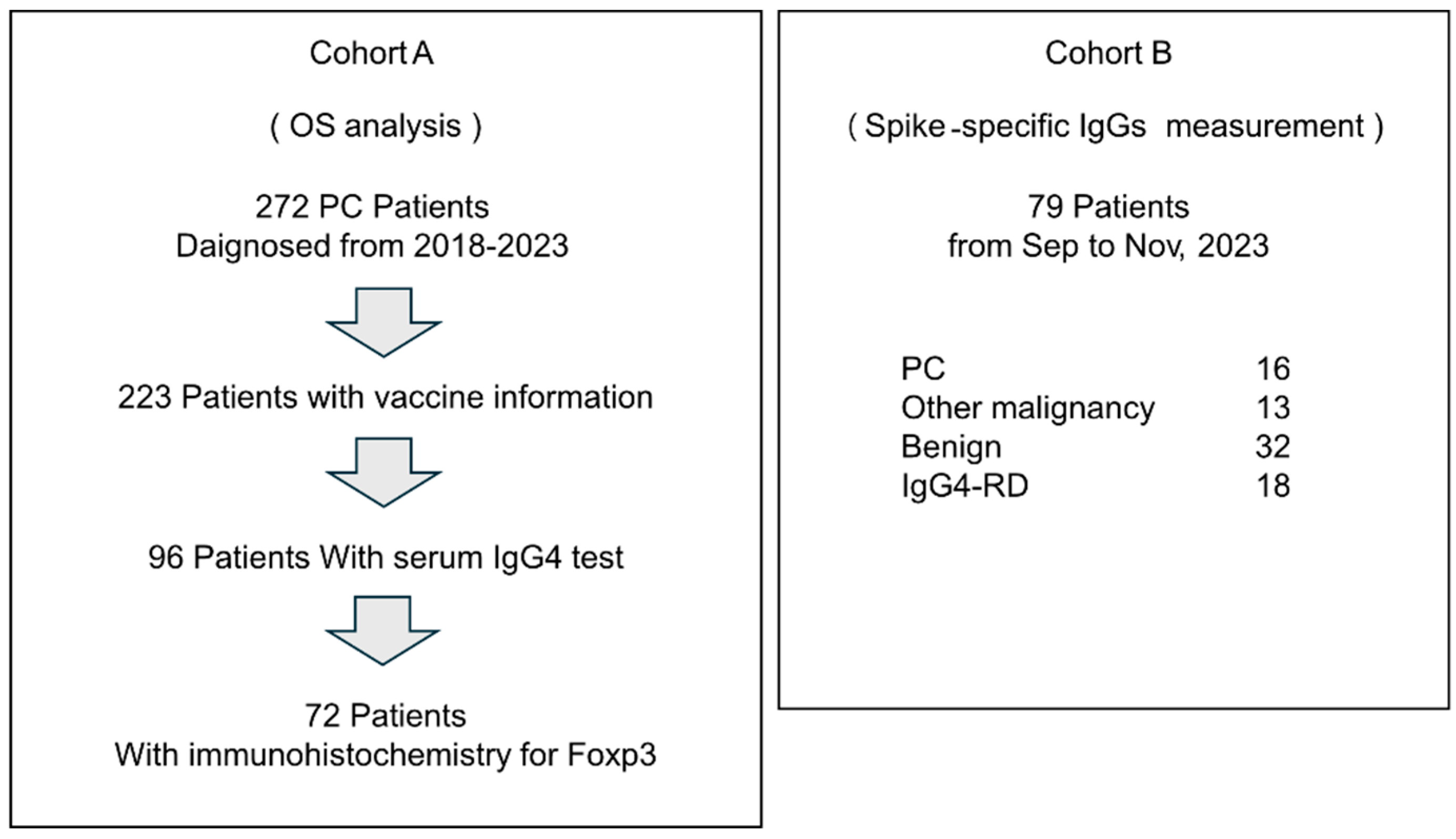

We performed a retrospective analysis at the Department of Gastroenterology, Miyagi Cancer Center, where 272 patients with PCs were enrolled between January 2018 and November 2023 (Cohort A,

Figure 1). Among them, vaccination history information at diagnosis was available for 223 patients, and total IgG and IgG4 levels were determined (turbidimetric and latex turbidimetric immunoassays, respectively; BML, Tokyo, Japan) in 96 patients. Of these 96 patients, biopsies or surgical resections, as well as immunohistochemistry for Foxp3, were performed in 72 patients. The specimens from the 72 cases comprised 30 surgical specimens, 39 endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNA) specimens, and 3 biopsy specimens of the duodenal and bile duct invasion sites, all of which were primary PC.

To measure spike-specific antibodies, a further 79 patients [patients with PC (n = 16), cancer other than PC (n = 13), benign disease (n = 32), and IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) (n = 18)] at the Department of Gastroenterology, Miyagi Cancer Center, between September and November 2023, were registered prospectively (Cohort B, Fig. 1). Blood samples were collected, and total IgG, total IgG4, and spike-specific IgG levels were measured. Information on number of COVID-19 vaccinations received by patients at the time of blood specimen collection was obtained from medical records. We collected tumor information on pathological stage based on the UICC TNM classification of malignant tumors (8th edition). The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (PS) Scale was used to assess the patient's general condition at the initial visit.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for Foxp3 was performed on 72 patients in Cohort A using the Ventana Benchmark system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The primary antibody used in this study was anti-Foxp3 antibody (ab20034; Abcam).

2.3. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Spike-specific IgG (total IgG, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4) levels were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in Cohort B, as described previously, with slight modifications [

47]. Briefly, 96-well plates (#9018, Corning, Corning, NY, USA) were coated overnight at 4°C with SARS-CoV-2 full-length recombinant spike protein (1 μg/ml in bicarbonate buffer [pH 9.8], R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA). For calibration, 96-well plates were coated overnight at 4 °C with purified human IgG1 (ab90283, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, 125 to 8000 ng/ml in bicarbonate buffer [pH 9.8]), IgG2 (ab90284, Abcam, 62.5 to 4000 ng/ml), IgG3 (ab118426, Abcam, 15.63 to 1000 ng/ml), IgG4 (ab183266, Abcam, 31.25 to 2000 ng/ml), and total IgG (143-09501, Fujifilm Wako, Osaka, Japan, 7.81 to 500 ng/ml). After washing with phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween20 (PBS-T), the plates were blocked with PBS-T containing 1% BSA. Next, serum samples were added to the plates at dilutions between 1:10 and 1:10,000, followed by incubation at 32°C for 1 h. Antigen-bound antibodies were then detected with HRP-conjugated mouse anti-human subclass specific antibodies (IgG1: 9054-05, IgG2: 9060-05, IgG3: 9210-05, IgG4 9200-05 and total IgG: 2040-05, Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). The absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 620 nm using a plate reader (Synergy LX; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.4. Statistics Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software v10.1.2(324), San Diego, California, USA). Non-parametric statistical tests, such as the Mann–Whitney test for two groups and the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for multiple independent groups, were used. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the log-rank test or Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test was used for significance testing. In addition, a propensity score matching method was used to reduce the effects of confounding. Matching was performed using R software (4.2.2) with a caliper width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the log of the propensity score, nearest neighbor method, and 1:1 matching protocol without replacement. Variables were selected on the basis of clinical experience, and the success of balancing distributions between two groups. Multivariate analysis of the prognostic factors, including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) [

48], modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) [

49], and Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) [

50], were performed using Cox proportional hazards analysis. The mGPS and PNI were defined as according to previous reports [

49,

50] as follows: C-reactive protein (CRP) level ≤1.0 mg/dl and Alb level ≥ 3.5 g/dl; score 0; CRP level >1.0 mg/dl or Alb level <3.5 g/dl; score 1; CRP level >1.0 mg/dl and Alb level <3.5 g/dl; score 2. PNI =10 × Alb (g/dl) + 0.005 × lymphocyte (/µl)). Cutoff values for NLR, PNI, and IgG4 were determined based on receiver operating characteristic curves. Foxp3-positive cells in immunohistochemistry were observed in a 40x higher power field of view and the number of Foxp3-positive cells in the total cells within 0.01 square millimeter (100 μm x 100 μm) was counted in five areas using NDP.view2 image viewing software (U12388-01, HAMAMATSU). Hematoxylin-positive cells were counted for total cell counts. Scatter plots of spike-specific IgG4 and total IgG4 were created, and regression lines along with coefficients of determination (R

2) were calculated using R software (4.2.2). Statistical significance was set at *P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Repeated COVID-19 Vaccination Worsens the Prognosis of PC Patients

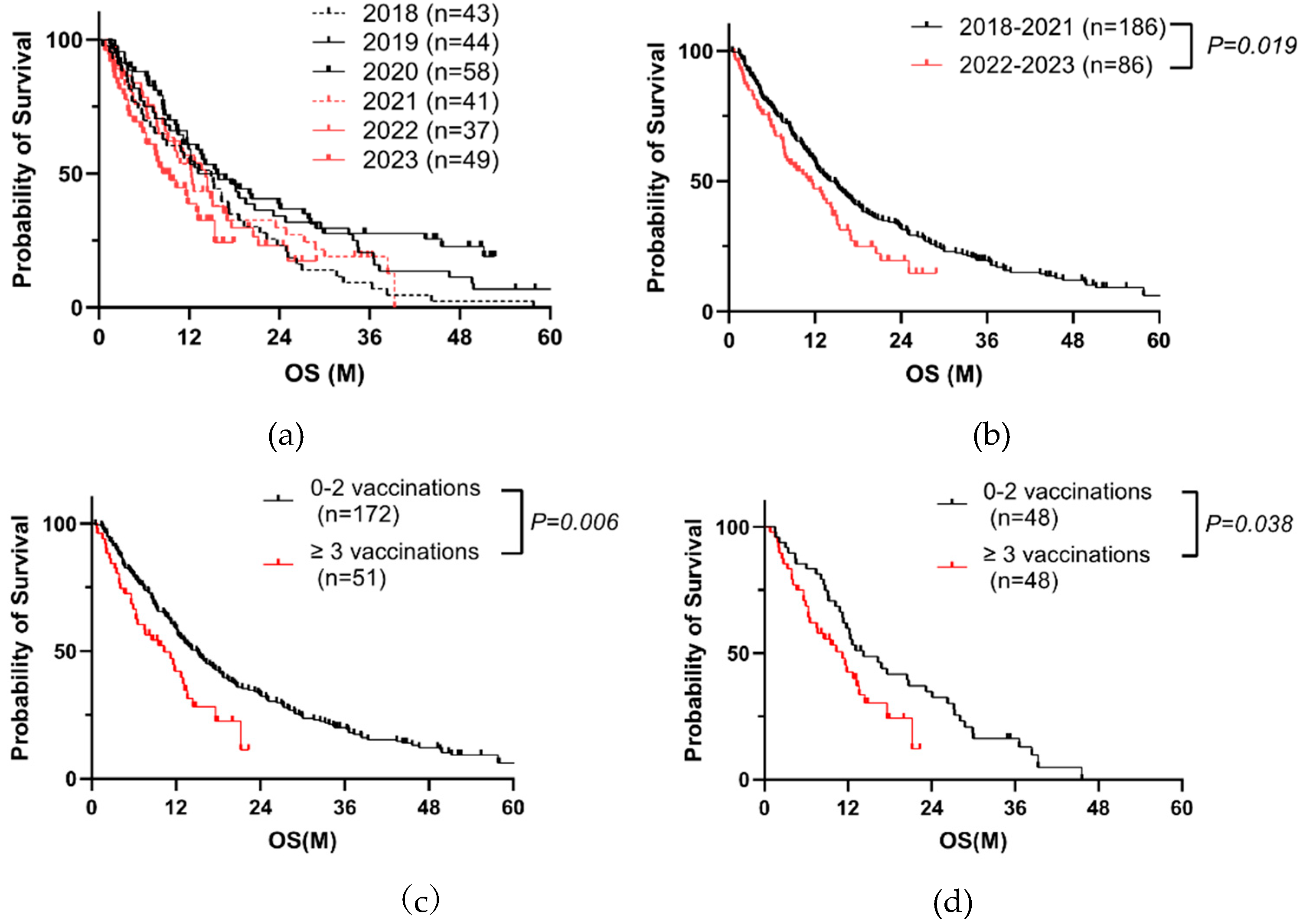

We analyzed the prognosis of PC patients before and after receiving SARS-CoV-2 vaccination from 2018 to 2023 (

Table 1, Cohort A). Patient outcomes had improved each year by 2020; however, it began to deteriorate in 2021 (

Figure 2a). The outcomes in 2022-2023 were significantly worse than those in 2018-2021 (

Figure 2b). Cox proportional hazards analysis indicated that a history of receiving COVID-19 vaccinations (three or more times) at the initial visit, PS, jaundice, high TNM factors, no surgery, no chemotherapy, and high tumor makers including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 significantly affected overall survival (OS) (

Table 2). Of 272 cases, the information of vaccination was recorded in 223 cases. When divided into two groups, 0-2 vaccinations or more than two vaccinations, we found that poorer prognosis in the latter (

Figure 2c). After propensity score matching for TNM factors, surgery, and chemotherapy, we got a similar result (Figure2d,

Table 3). These data suggested that the repeated vaccinations is a negative prognostic factor.

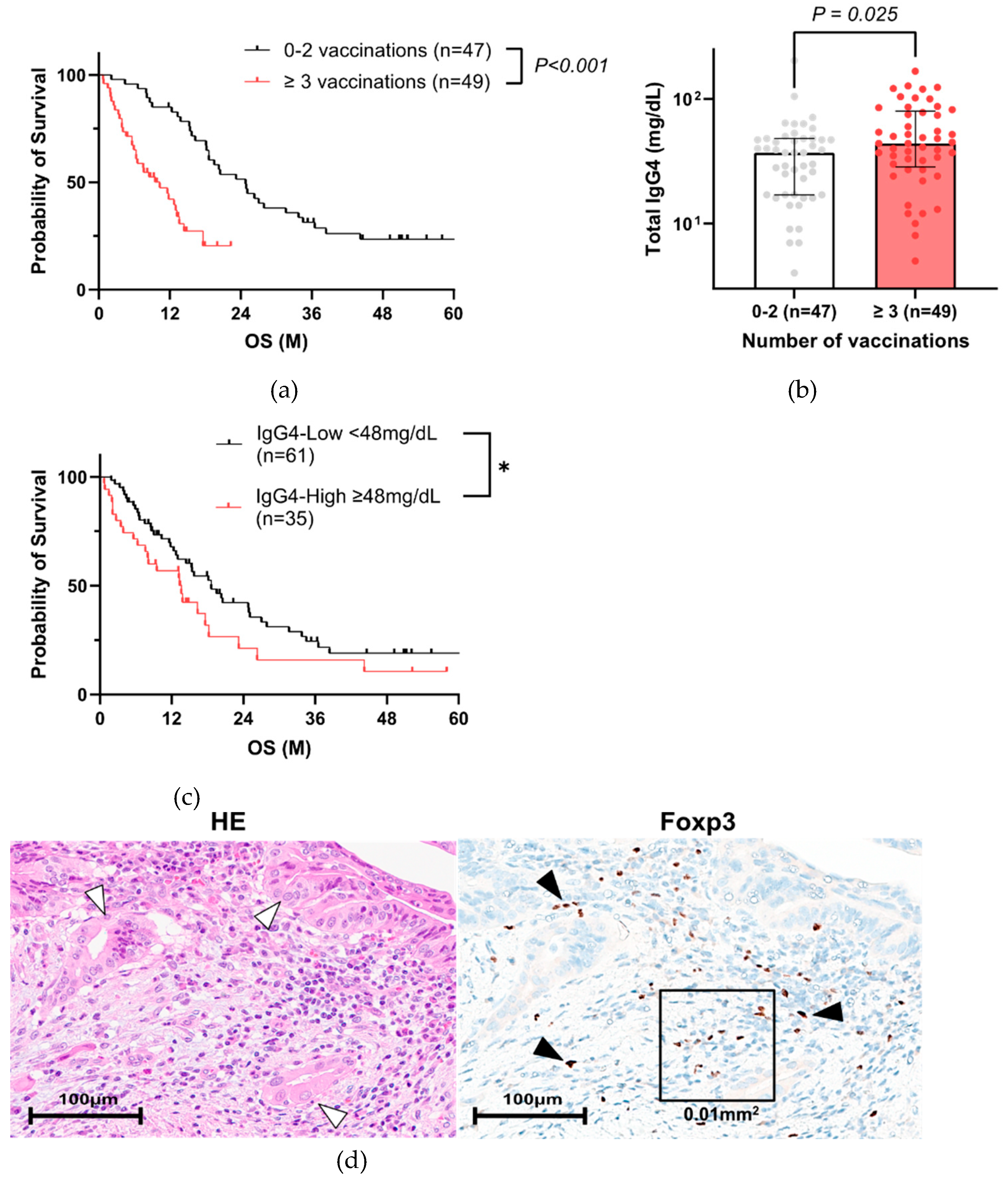

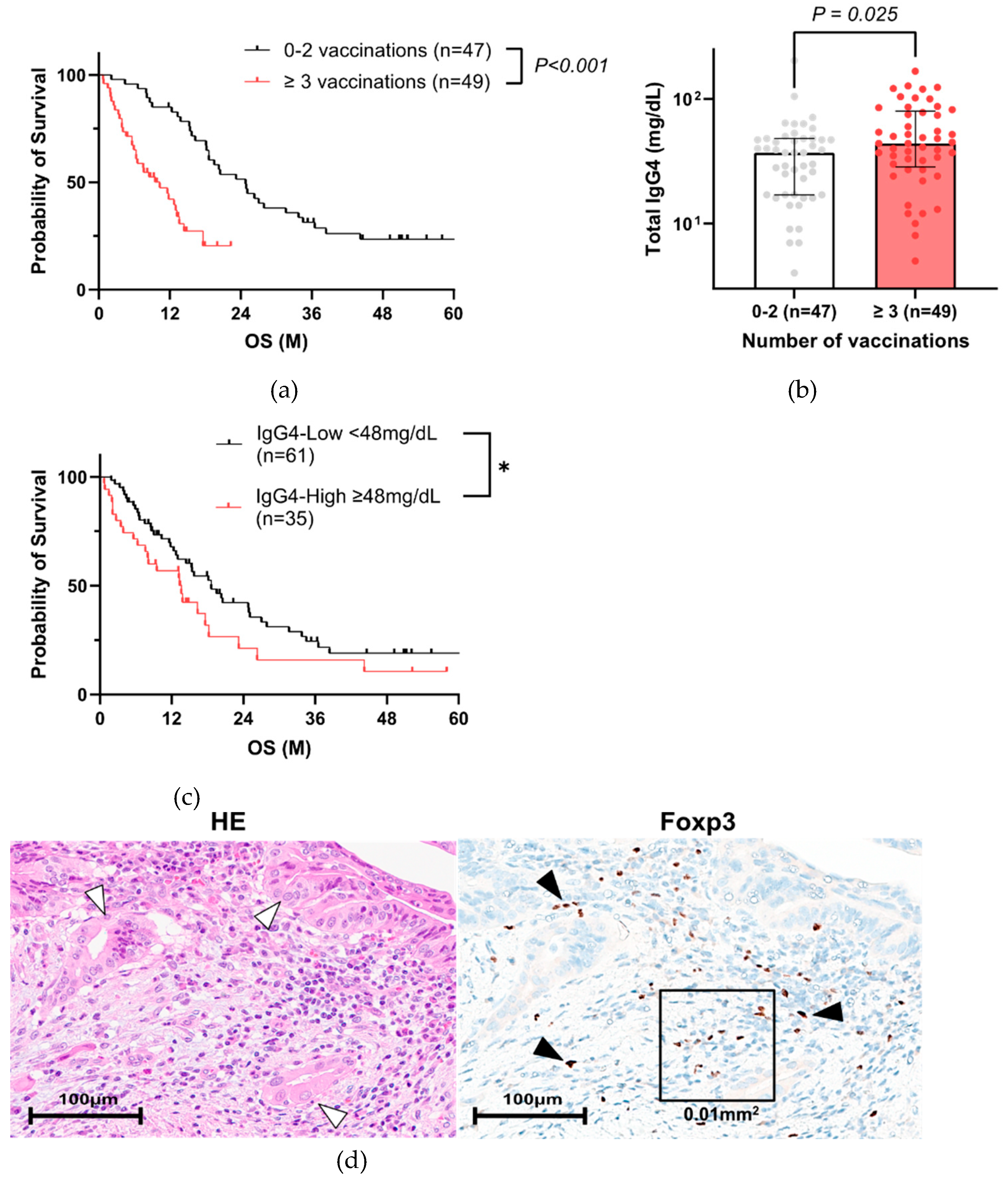

3.2. High Total IgG4 Level Correlates with Poor PC Prognosis

We hypothesized that IgG4, known to be induced by COVID-19 vaccination, deteriorates the prognosis of PC patients. Therefore, we compared the relationship between IgG4 levels and vaccination. Of 223 cases, serum IgG4 value was recorded in 96 patients with vaccination history information (

Table 3). In this population, three or more vaccination group also had a poorer prognosis (

Figure 3a), similar to

Figure 2c. The characteristics of the 96 PC patients in Cohort A are shown in

Table 4. The group with 3 or more vaccinations had significantly higher NLR, lower PNI, which were also extracted as significant factors in the multivariate analysis (

Table 5). The same result was obtained when 66 patients with matched backgrounds were examined, excluding surgical cases (

Supplementary Figure S1, Table S1, S2). Total IgG4 levels were significantly higher in three or more vaccination group (

Figure 3b,

Table 4), particularly in five or more vaccinations (

Supplementary Figure S2). When the patients were divided into two groups based on total IgG4 expression (

Supplementary Table S3), the prognosis was significantly worse in the IgG4-high group (

Figure 3c). When the patients were divided into two groups based on OS, total IgG4 level was also significantly higher in the short OS (< 90 days) group (

Supplemental Figure S3).

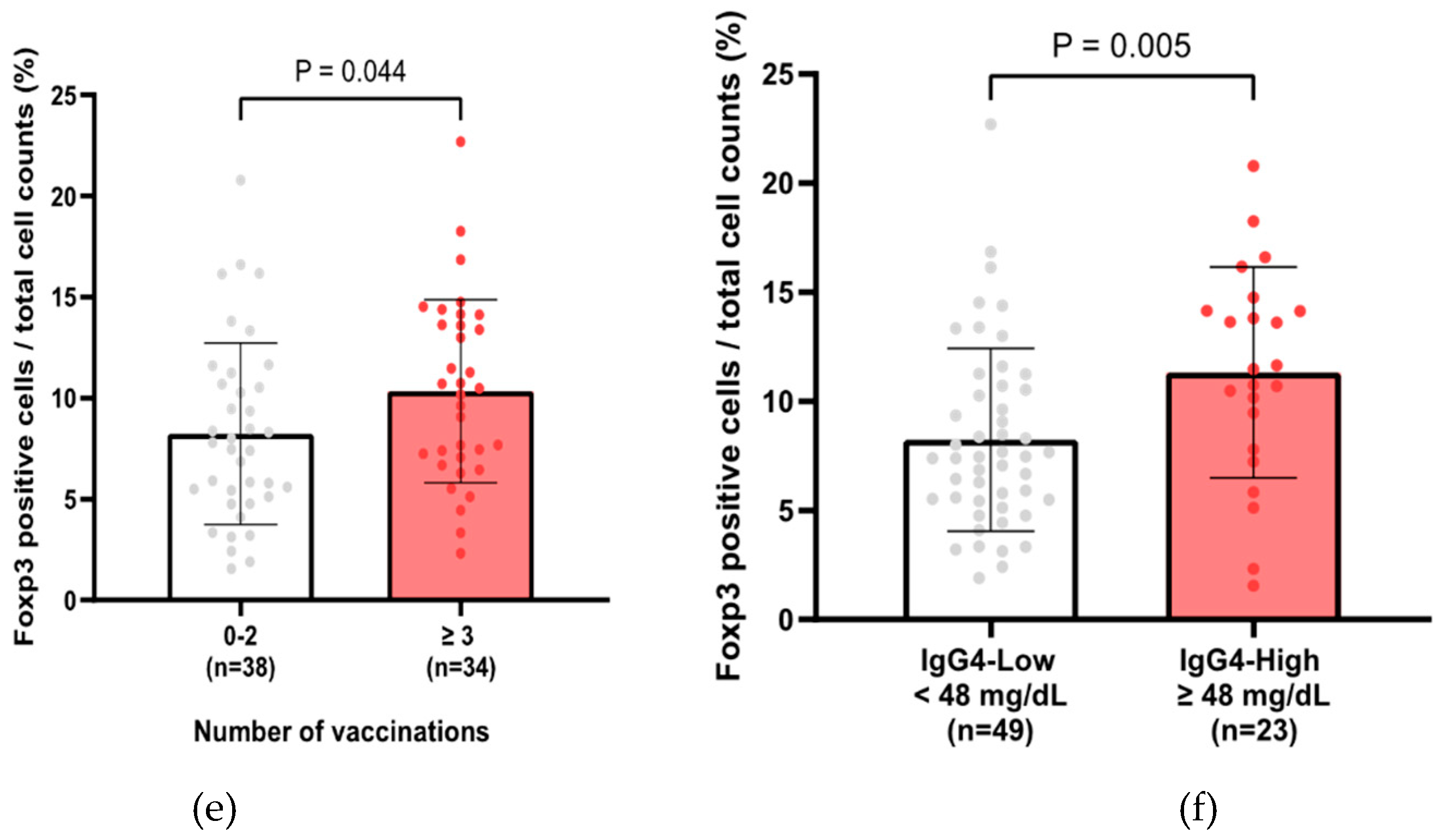

To investigate the relationships between IgG4 and Tregs in patients who have been repeatedly vaccinated, immunohistochemical analysis of Foxp3 was performed in 72 of 96 cases who had undergone surgical resection or endoscopic biopsy (

Supplementary Table S4). Foxp3-positive cells were observed around tumor cells (

Figure 3d). The average percentage of Foxp3-positive cells in total cell counts was a median of 8.3 ± 4.6 % in 72 cases, and the percentage of Foxp3-positive cells in identified in or around the tumor cells was significantly higher in the three or more vaccination groups (

Figure 3e) and in the group with high serum IgG4 levels (

Figure 3f).

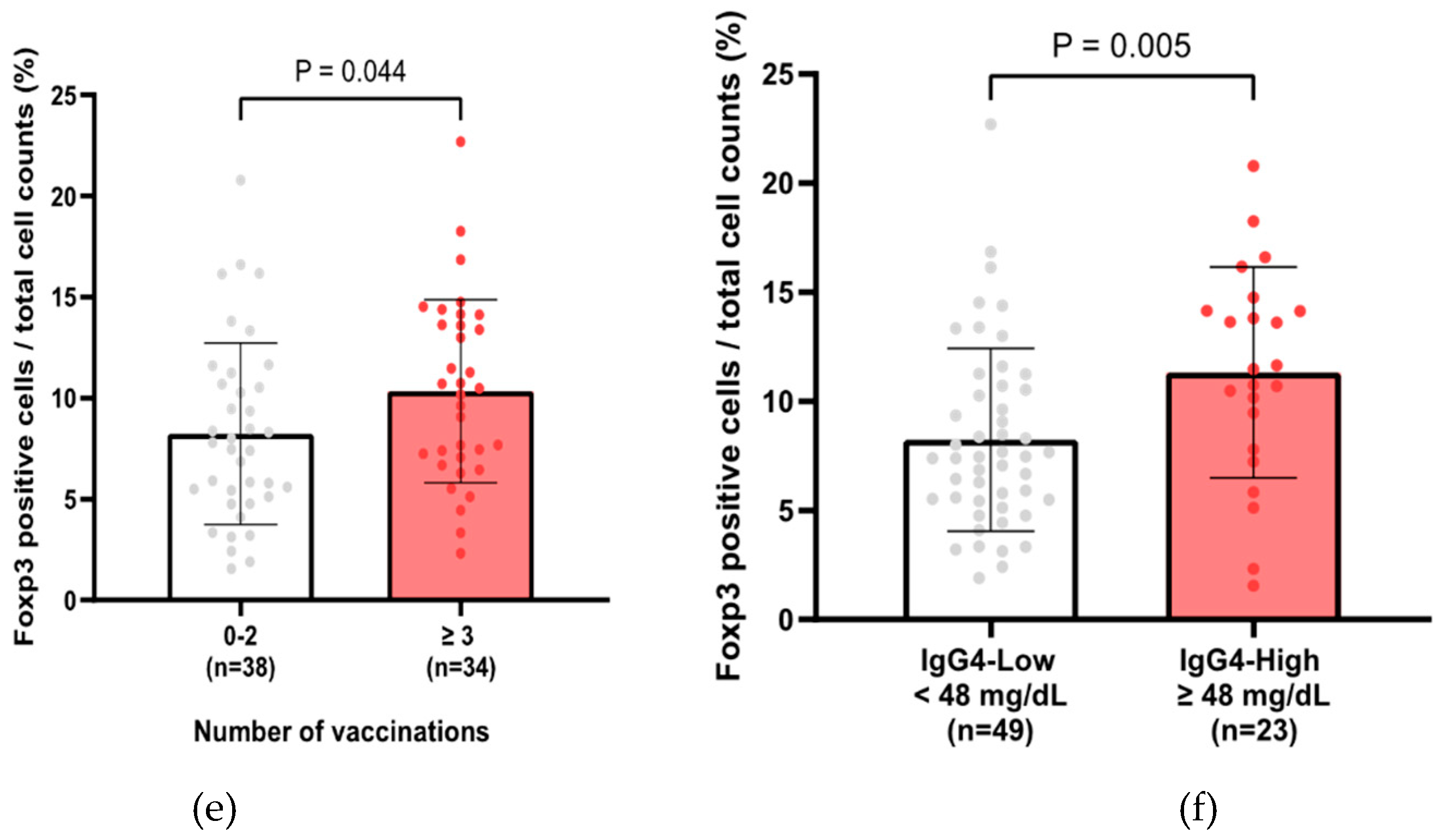

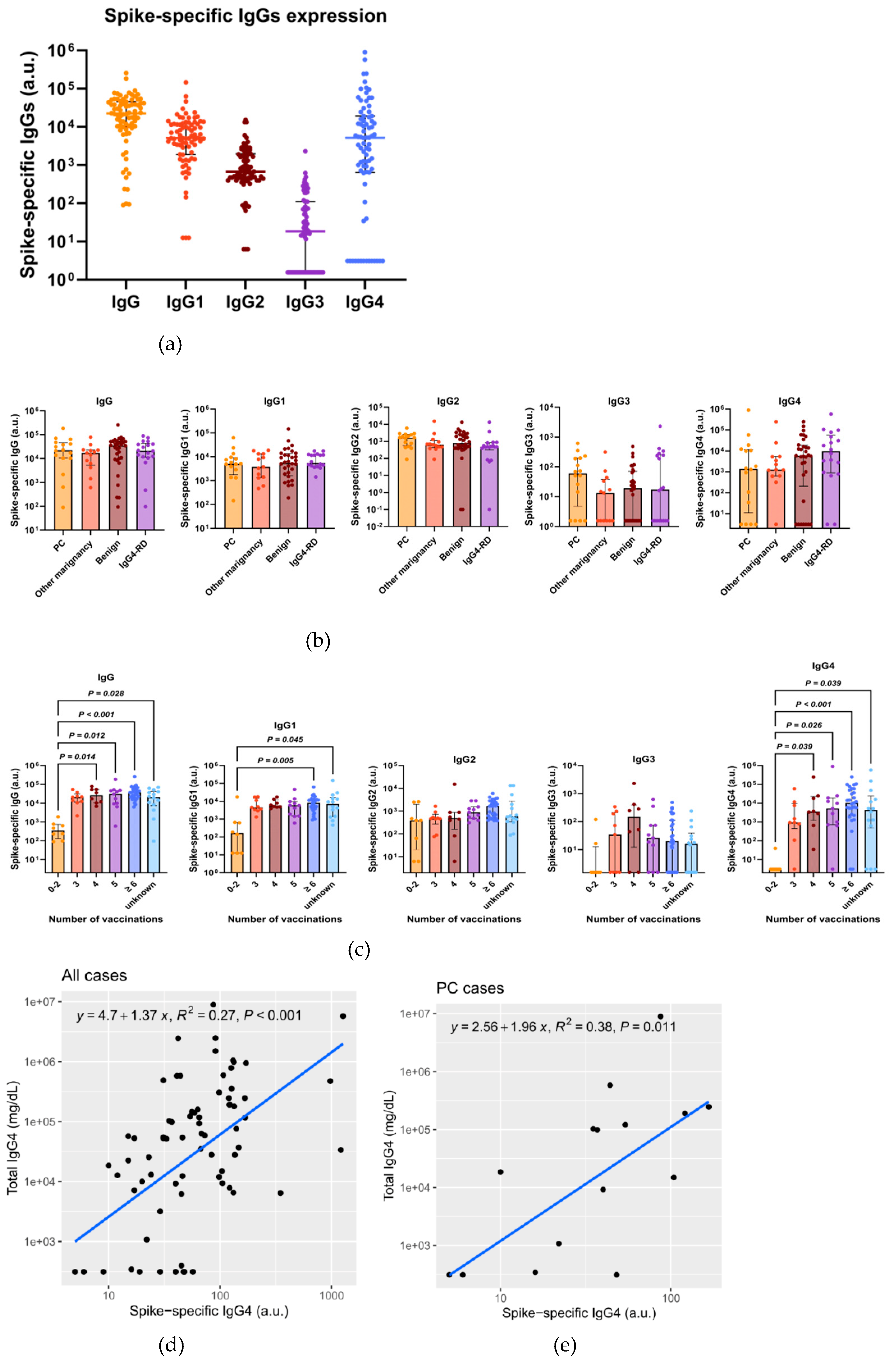

3.3. Total IgG4, Along with Spike-Specific IgG4, Is Increased in Patients with Repeated COVID-19 Vaccination

To confirm that the increase in total IgG4 level was due to spike-specific IgG4, we determined the total and spike-specific IgGs in Cohort B. The characteristics of 79 patients in Cohort B are shown in

Supplementary Table S4. We included malignant and benign diseases other than pancreatic cancer to determine whether the changes in IgGs depends on specific diseases. Spike-specific IgG1 and IgG4 were detected in higher amounts, whereas IgG2 and IgG3 were detected in lower amounts (

Figure 4a). No significant difference was noted in the spike-specific IgG levels, including IgG4, between the disease types (

Figure 4b). Spike-specific IgG4, IgG1, and IgG levels increased in the groups that were vaccinated more than three times (

Figure 4c). Total IgG4 and spike-specific IgG4 levels were positively correlated in both cases (

Figure 4d) and PC patients (

Figure 4e).

4. Discussion

In Japan, the mRNA-type COVID-19 vaccine is mainly used for initial immunization, and additional immunizations are repeatedly administered to prevent severe disease [

31]. However, repeated immunization with the COVID-19 vaccine can accelerate the transition to IgG4 [

51] and increase spike-specific IgG4 levels [

37,

38,

51], which is consistent with our findings. Elevated IgG4 level can promote cancer growth by suppressing cancer immunity and is associated with a poor prognosis [

39,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Only few countries administer more than five doses of vaccinations, and the impact of repeated vaccinations on IgG4 levels against cancer are unclear. In this study, our results demonstrated that more than three vaccination doses correlated with poor prognosis in patients with PC, particularly in those whom the total IgG4 level was increased after vaccination. Higher total IgG4 level also correlated with poor prognosis. There was an overall positive correlation between total IgG4 and spike-specific IgG4 levels. Our findings collectively indicate that spike-specific IgG4 could be correlated to the prognosis of PC patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report a correlation between SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and PC prognosis.

In this study, high NLR, mGPS1-2, and low PNI, all of which are nutritional indices and indicators of poor prognosis in PC [

48,

49,

50,

52], were significantly correlated with poor prognosis. Multivariate analysis revealed that repeated vaccination, but not NLR, mGPS, and PNI, was an independent poor prognostic factor, suggesting that the nutritional indices are confounding factors. Indeed, repeated vaccination was significantly correlated with NLR and PNI. A previous report also demonstrated that vaccination increases NLR [

53]. These data suggest that vaccination influences neutrophils and lymphocytes. Further study should elucidate whether vaccinations alter leukocyte subsets, resulting in increase of IgG4 production.

Vaccination also alters other immune system components, beside IgG4, and potential side effects have been reported in previous preclinical studies. Seneff et al. reported that vaccination suppresses type I interferon signaling and has various adverse effects on human health, including cancer surveillance [

54]. BNT162b2 vaccination led to an increase in Tregs [

55,

56]. Tregs, a subset of CD4+ T cells expressing Foxp3, play critical roles in suppressing immune responses and migrating toward tumors in the presence of chemokines to suppress antitumor immune responses, causing cancer cells to grow and proliferate [

57]. A high infiltration by Tregs has been associated with poor survival in various types of cancer [

58]. In mice, the percentage of CD25+Foxp3+CD4+ Tregs and the levels of immunosuppression cytokines IL-10 were up-regulated after extended RBD vaccine booster vaccination. This may result in reduced activation and differentiation of B cells on antigen stimulation, functional inhibition of antigen-presenting cells, consequential decrease in CD8+T cell activation, and increased PD-1 and LAG-3 expression in these T cells [

59]. Repeat vaccination with the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine booster may be a potential risk for cancer. Some studies have reported the association between SARS-CoV-2 spike and p53 [

60,

61]. This study also showed a significant correlation between serum IgG4 level and Foxp3-positive cell infiltration in tissues, suggesting that Treg could be a factor for poor prognosis in repeated vaccinated patients. Further studies are needed to determine the detailed pathway through which repeated vaccinations affect prognosis.

Previous studies indicate that the number of IgG4-positive plasma cells in the tissues increases in IgG4-RD, with elevated total serum IgG4 levels [

62,

63]. Increased IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration into or around cancer tissues has been associated with poor prognosis in cancers including PC, cholangiocarcinoma, gastric cancer, and esophageal cancer [

39,

41,

42,

43,

44]. The high-level intratumoral infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells is an independent predictor for poor OS in PC patients after curative resection, and M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages within the tumor are associated with IgG4 induction [

41]. In cholangiocellular carcinoma, the involvement of Treg and IL-10 in IgG4 induction has also been reported [

43]. Moreover, elevated total serum IgG4 level, regardless of antigen specificity, may affect the cancer microenvironment [

39]. Repeated COVID-19 mRNA vaccination results in IgG4 class switching and decreased NK cell activation by S1-specific antibodies [

64]. Locally increased IgG4 in cancer microenvironment should inhibit antibody-mediated anticancer responses, allowing cancer to evade local immune attack and indirectly promote cancer growth; moreover, higher levels of IgG4 have been associated with more aggressive cancer progression [

39]. Therefore, identifying spike-specific IgG4 in tumor tissues would facilitate the analysis of the future relationships between vaccination and prognosis.

Limitations

This study was a retrospective, single-center cohort study comprising 96 cases of PC. However, the 79 cases in which anti-spike IgG4 was measured included specimens that were collected in approximately 3 months. The sample size of 96 cases was small, corresponding to 96 out of 272 PC patients treated during the same period, and all PC cases with IgG4 were not measured. Therefore, there is a possibility of bias in the sample selected for IgG4 measurements. All stages of PC were included in this study. The number of vaccinations doses considered in this study did not account for subsequent vaccinations received after the blood collection or history of COVID-19. The study also did not consider potential confounding factors such as patient comorbidities, concurrent treatment, or vaccine type. Future research should incorporate a larger cohort size and investigate additional mechanisms involved in immunity to SARS-CoV-2 following vaccination.

5. Conclusions

Repeated vaccination is a poor prognostic factor in PC patients. Repeated vaccination increased serum total and spike-specific IgG4 levels, which may be associated with poor prognosis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Total IgG4 measured in patients with pancreatic cancer in Cohort A. Serum total IgG4 levels are significantly increased with ≥ 5 vaccinations, compared with 0–2 vaccinations (Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.011); Figure S2: Comparison of the serum IgG4 values between overall survival ≥ 90 days and < 90 days groups (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.033); Table S1: Characteristics of 66 PC patients corrected for the exclusion of surgical cases in Cohort A; Table S2: Cox proportional hazards analysis of factors affecting PC prognosis (non surgical cases n=66); Table S3: Characteristics of high and low IgG4 groups in Cohort A; Table S4: Characteristics of 72 patients performed immunohistochemistry in Cohort A. Table S5: Characteristics of pancreatic cancer patients in Cohort B (n = 79).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., K.O., M.M., and K.T.; methodology, M.A., K.O., M.M., and K.T.; formal analysis, M.A. and K.T.; investigation, M.A., M.M., R.S., and K.T.; resources, K.O., Y.W., W.I., J.K., M.S., S.S., and I.S.; data curation, M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A., M.M., and K.T.; writing—review and editing, K.O, Y.W., W.I., J.K., M.S., S.S., and I.S.; funding acquisition, M.A. and K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. JP: 22K07313, 20K17068) for Cancer Research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Miyagi Cancer Center (approval no. 2023-011, 2024-003). Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study through an opt-out process.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study through an opt-out process.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yasuda (Miyagi Cancer Center Research Institute) for critical suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PC |

Pancreatic cancer |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| PS |

Performance status |

| CEA |

Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| CA19-9 |

Carbohydrate Antigen 19-9 |

| IgG4-RD |

IgG4-related disease |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| NLR |

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| mGPS |

modified Glasgow prognostic score |

| PNI |

Prognostic Nutritional Index |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| OS |

Overall Survival |

References

- American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures 2023. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/2023-cancer-facts-figures.html (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- National Cancer Center Japan Projected Cancer Statistics, 2022. Available online: https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/stat/short_pred_en.html (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Abe, K.; Kitago, M.; Kitagawa, Y.; Hirasawa, A. Hereditary Pancreatic Cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2021, 26, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubayashi, H.; Takaori, K.; Morizane, C.; Maguchi, H.; Mizuma, M.; Takahashi, H.; Wada, K.; Hosoi, H.; Yachida, S.; Suzuki, M.; et al. Familial Pancreatic Cancer: Concept, Management and Issues. World J Gastroenterol 2017, 23, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A.P. Pancreatic Cancer Epidemiology: Understanding the Role of Lifestyle and Inherited Risk Factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Bondy, M.L.; Wolff, R.A.; Abbruzzese, J.L.; Vauthey, J.-N.; Pisters, P.W.; Evans, D.B.; Khan, R.; Chou, T.-H.; Lenzi, R.; et al. Risk Factors for Pancreatic Cancer: Case-Control Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2007, 102, 2696–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitra, A.; Sharma, A.; Brand, R.E.; Van Den Eeden, S.K.; Fisher, W.E.; Hart, P.A.; Hughes, S.J.; Mather, K.J.; Pandol, S.J.; Park, W.G.; et al. A Prospective Study to Establish a New-Onset Diabetes Cohort: From the Consortium for the Study of Chronic Pancreatitis, Diabetes, and Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas 2018, 47, 1244–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Fernández-Del Castillo, C.; Kamisawa, T.; Jang, J.Y.; Levy, P.; Ohtsuka, T.; Salvia, R.; Shimizu, Y.; Tada, M.; Wolfgang, C.L. Revisions of International Consensus Fukuoka Guidelines for the Management of IPMN of the Pancreas. Pancreatology 2017, 17, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vege, S.S.; Ziring, B.; Jain, R.; Moayyedi, P. ; Clinical Guidelines Committee; American Gastroenterology Association American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Asymptomatic Neoplastic Pancreatic Cysts. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas European Evidence-Based Guidelines on Pancreatic Cystic Neoplasms. Gut 2018, 67, 789–804. [CrossRef]

- Kirkegård, J.; Mortensen, F.V.; Cronin-Fenton, D. Chronic Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2017, 112, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.; de la Fuente, J.; Murad, M.H.; Majumder, S. Chronic Pancreatitis Is a Risk Factor for Pancreatic Cancer, and Incidence Increases With Duration of Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2022, 13, e00463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, D.S.; Giovannucci, E.; Willett, W.C.; Colditz, G.A.; Stampfer, M.J.; Fuchs, C.S. Physical Activity, Obesity, Height, and the Risk of Pancreatic Cancer. JAMA 2001, 286, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanno, A.; Masamune, A.; Hanada, K.; Maguchi, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Ueki, T.; Hasebe, O.; Ohtsuka, T.; Nakamura, M.; Takenaka, M.; et al. Multicenter Study of Early Pancreatic Cancer in Japan. Pancreatology 2018, 18, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhi, A.D.; Koay, E.J.; Chari, S.T.; Maitra, A. Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer: Opportunities and Challenges. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 2024–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, S.P.; Oldfield, L.; Ney, A.; Hart, P.A.; Keane, M.G.; Pandol, S.J.; Li, D.; Greenhalf, W.; Jeon, C.Y.; Koay, E.J.; et al. Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 5, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.D.; Canto, M.I.; Jaffee, E.M.; Simeone, D.M. Pancreatic Cancer: Pathogenesis, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 386–402.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goggins, M.; Overbeek, K.A.; Brand, R.; Syngal, S.; Del Chiaro, M.; Bartsch, D.K.; Bassi, C.; Carrato, A.; Farrell, J.; Fishman, E.K.; et al. Management of Patients with Increased Risk for Familial Pancreatic Cancer: Updated Recommendations from the International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium. Gut 2020, 69, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partyka, O.; Pajewska, M.; Kwaśniewska, D.; Czerw, A.; Deptała, A.; Budzik, M.; Cipora, E.; Gąska, I.; Gazdowicz, L.; Mielnik, A.; et al. Overview of Pancreatic Cancer Epidemiology in Europe and Recommendations for Screening in High-Risk Populations. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, T.; Desseigne, F.; Ychou, M.; Bouché, O.; Guimbaud, R.; Bécouarn, Y.; Adenis, A.; Raoul, J.-L.; Gourgou-Bourgade, S.; De La Fouchardière, C.; et al. FOLFIRINOX versus Gemcitabine for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med 2011, 364, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hoff, D.D.; Ervin, T.; Arena, F.P.; Chiorean, E.G.; Infante, J.; Moore, M.; Seay, T.; Tjulandin, S.A.; Ma, W.W.; Saleh, M.N.; et al. Increased Survival in Pancreatic Cancer with Nab-Paclitaxel plus Gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013, 369, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Gillam, A.; Li, C.-P.; Bodoky, G.; Dean, A.; Shan, Y.-S.; Jameson, G.; Macarulla, T.; Lee, K.-H.; Cunningham, D.; Blanc, J.F.; et al. Nanoliposomal Irinotecan with Fluorouracil and Folinic Acid in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer after Previous Gemcitabine-Based Therapy (NAPOLI-1): A Global, Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unno, M.; Motoi, F.; Matsuyama, Y.; Satoi, S.; Matsumoto, I.; Aosasa, S.; Shirakawa, H.; Wada, K.; Fujii, T.; Yoshitomi, H.; et al. Randomized Phase II/III Trial of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with Gemcitabine and S-1 versus Upfront Surgery for Resectable Pancreatic Cancer (Prep-02/JSAP-05). JCO 2019, 37, 189–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettle, H.; Neuhaus, P.; Hochhaus, A.; Hartmann, J.T.; Gellert, K.; Ridwelski, K.; Niedergethmann, M.; Zülke, C.; Fahlke, J.; Arning, M.B.; et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy with Gemcitabine and Long-Term Outcomes among Patients with Resected Pancreatic Cancer: The CONKO-001 Randomized Trial. JAMA 2013, 310, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uesaka, K.; Boku, N.; Fukutomi, A.; Okamura, Y.; Konishi, M.; Matsumoto, I.; Kaneoka, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Nakamori, S.; Sakamoto, H.; et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy of S-1 versus Gemcitabine for Resected Pancreatic Cancer: A Phase 3, Open-Label, Randomised, Non-Inferiority Trial (JASPAC 01). Lancet 2016, 388, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, T.; Hammel, P.; Hebbar, M.; Ben Abdelghani, M.; Wei, A.C.; Raoul, J.-L.; Choné, L.; Francois, E.; Artru, P.; Biagi, J.J.; et al. FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 2395–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Stratton, C.W.; Tang, Y. Outbreak of Pneumonia of Unknown Etiology in Wuhan, China: The Mystery and the Miracle. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 401–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, D.M.; Boyton, R.J. COVID-19 Vaccination: The Road Ahead. Science 2022, 375, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime Minister’s Office of Japan Ongoing Topics, COVID-19 Vaccines. Available online: https://japan.kantei.go.jp/ongoingtopics/index.html (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Verbeke, R.; Lentacker, I.; De Smedt, S.C.; Dewitte, H. The Dawn of mRNA Vaccines: The COVID-19 Case. J Control Release 2021, 333, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, S.P. Review of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines: BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273. J Pharm Pract 2022, 35, 947–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.P.; Zeng, C.; Carlin, C.; Lozanski, G.; Saif, L.J.; Oltz, E.M.; Gumina, R.J.; Liu, S.-L. Neutralizing Antibody Responses Elicited by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination Wane over Time and Are Boosted by Breakthrough Infection. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14, eabn8057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Bai, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhao, W.; Wu, J. The Kinetics of IgG Subclasses and Contributions to Neutralizing Activity against SARS-CoV-2 Wild-Type Strain and Variants in Healthy Adults Immunized with Inactivated Vaccine. Immunology 2022, 167, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidarsson, G.; Dekkers, G.; Rispens, T. IgG Subclasses and Allotypes: From Structure to Effector Functions. Front Immunol 2014, 5, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiszel, P.; Sík, P.; Miklós, J.; Kajdácsi, E.; Sinkovits, G.; Cervenak, L.; Prohászka, Z. Class Switch towards Spike Protein-Specific IgG4 Antibodies after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination Depends on Prior Infection History. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 13166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irrgang, P.; Gerling, J.; Kocher, K.; Lapuente, D.; Steininger, P.; Habenicht, K.; Wytopil, M.; Beileke, S.; Schäfer, S.; Zhong, J.; et al. Class Switch toward Noninflammatory, Spike-Specific IgG4 Antibodies after Repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8, eade2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; et al. An Immune Evasion Mechanism with IgG4 Playing an Essential Role in Cancer and Implication for Immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8, e000661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazale, A.; Chari, S.T.; Smyrk, T.C.; Levy, M.J.; Topazian, M.D.; Takahashi, N.; Clain, J.E.; Pearson, R.K.; Pelaez-Luna, M.; Petersen, B.T.; et al. Value of Serum IgG4 in the Diagnosis of Autoimmune Pancreatitis and in Distinguishing It from Pancreatic Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2007, 102, 1646–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Niu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Pan, B.; Lu, Z.; Liao, Q.; Zhao, Y. Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-Positive Plasma Cell Infiltration Is Associated with the Clinicopathologic Traits and Prognosis of Pancreatic Cancer after Curative Resection. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2016, 65, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, T.; Uehara, T.; Iwaya, M.; Asaka, S.; Nakajima, T.; Kinugawa, Y.; Shimizu, A.; Kubota, K.; Notake, T.; Masuo, H.; et al. IgG4 Expression and IgG4/IgG Ratio in the Tumour Invasion Front Predict Long-Term Outcomes for Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Pathology 2023, 55, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.; Shimoda, S.; Kimura, Y.; Sato, Y.; Ikeda, H.; Igarashi, S.; Ren, X.-S.; Sato, H.; Nakanuma, Y. Significance of Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-Positive Cells in Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Molecular Mechanism of IgG4 Reaction in Cancer Tissue. Hepatology 2012, 56, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyatani, K.; Saito, H.; Murakami, Y.; Watanabe, J.; Kuroda, H.; Matsunaga, T.; Fukumoto, Y.; Osaki, T.; Nakayama, Y.; Umekita, Y.; et al. A High Number of IgG4-Positive Cells in Gastric Cancer Tissue Is Associated with Tumor Progression and Poor Prognosis. Virchows Arch 2016, 468, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka, N.; Onozato, K.; Kosuge, T.; Hirohashi, S. Prevalence of FOXP3+ Regulatory T Cells Increases during the Progression of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Its Premalignant Lesions. Clin Cancer Res 2006, 12, 5423–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, K.; Nakanuma, Y. Cholangiocarcinoma with Respect to IgG4 Reaction. Int J Hepatol 2014, 2014, 803876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkovits, G.; Szilágyi, Á.; Farkas, P.; Inotai, D.; Szilvási, A.; Tordai, A.; Rázsó, K.; Réti, M.; Prohászka, Z. Concentration and Subclass Distribution of Anti-ADAMTS13 IgG Autoantibodies in Different Stages of Acquired Idiopathic Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Long, F.; Jaiswar, M.; Yang, L.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Z. Prognostic Role of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Pancreatic Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaoka, H.; Mizuno, N.; Hara, K.; Hijioka, S.; Tajika, M.; Tanaka, T.; Ishihara, M.; Yogi, T.; Tsutsumi, H.; Fujiyoshi, T.; et al. Evaluation of Modified Glasgow Prognostic Score for Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Pancreas 2016, 45, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Qi, Q.; Sun, M.; Chen, H.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z. Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts Survival and Correlates with Systemic Inflammatory Response in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015, 41, 1508–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N.; Redwan, E.M.; Makis, W.; Rubio-Casillas, A. IgG4 Antibodies Induced by Repeated Vaccination May Generate Immune Tolerance to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Grimes, N.; Farid, S.; Morris-Stiff, G. Inflammatory Response Related Scoring Systems in Assessing the Prognosis of Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Systematic Review. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014, 13, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafeeq, M.; Jabir, M.S.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Jeddoa, Z.M.A.; Jawad, S.F.; Najm, M. a. A.; Almulla, A.F.; Elekhnawy, E.; Tayyeb, J.Z.; Turkistani, A.; et al. Evaluation of the Hematological and Immunological Markers after the First and Second Doses of BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2024, 28, 2605–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneff, S.; Nigh, G.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; McCullough, P.A. Innate Immune Suppression by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccinations: The Role of G-Quadruplexes, Exosomes, and MicroRNAs. Food Chem Toxicol 2022, 164, 113008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbel, R.; Peretz, A.; Sergienko, R.; Friger, M.; Beckenstein, T.; Duskin-Bitan, H.; Yaron, S.; Hammerman, A.; Bilenko, N.; Netzer, D. Effectiveness of a Bivalent mRNA Vaccine Booster Dose to Prevent Severe COVID-19 Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Gualana, F.; Maiorca, F.; Marrapodi, R.; Villani, F.; Miglionico, M.; Santini, S.A.; Pulcinelli, F.; Gragnani, L.; Piconese, S.; Fiorilli, M. Opposite Effects of mRNA-Based and Adenovirus-Vectored SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines on Regulatory T Cells: A Pilot Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Yang, K.; Zhu, L.; Yin, D.; Zhou, Y. Regulatory T Cells as Crucial Trigger and Potential Target for Hyperprogressive Disease Subsequent to PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade for Cancer Treatment. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 132, 111934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohue, Y.; Nishikawa, H. Regulatory T (Treg) Cells in Cancer: Can Treg Cells Be a New Therapeutic Target? Cancer Sci 2019, 110, 2080–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.-X.; Wu, R.-X.; Shen, M.-Y.; Huang, J.-J.; Li, T.-T.; Hu, C.; Luo, F.-Y.; Song, S.-Y.; Mu, S.; Hao, Y.-N.; et al. Extended SARS-CoV-2 RBD Booster Vaccination Induces Humoral and Cellular Immune Tolerance in Mice. iScience 2022, 25, 105479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Bharara Singh, A. S2 Subunit of SARS-nCoV-2 Interacts with Tumor Suppressor Protein P53 and BRCA: An in Silico Study. Transl Oncol 2020, 13, 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; El-Deiry, W.S. Transfected SARS-CoV-2 Spike DNA for Mammalian Cell Expression Inhibits P53 Activation of P21(WAF1), TRAIL Death Receptor DR5 and MDM2 Proteins in Cancer Cells and Increases Cancer Cell Viability after Chemotherapy Exposure. Oncotarget 2024, 15, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawa, S.; Kamisawa, T.; Notohara, K.; Fujinaga, Y.; Inoue, D.; Koyama, T.; Okazaki, K. Japanese Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Autoimmune Pancreatitis, 2018. Pancreas 2020, 49, e13–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Z.S.; Naden, R.P.; Chari, S.; Choi, H.; Della-Torre, E.; Dicaire, J.-F.; Hart, P.A.; Inoue, D.; Kawano, M.; Khosroshahi, A.; et al. The 2019 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for IgG4-Related Disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020, 72, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderloos, A.T.; Verheul, M.K.; Middelhof, I.; de Zeeuw-Brouwer, M.-L.; van Binnendijk, R.S.; Buisman, A.-M.; van Kasteren, P.B. Repeated COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination Results in IgG4 Class Switching and Decreased NK Cell Activation by S1-Specific Antibodies in Older Adults. Immun Ageing 2024, 21, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

A schema of cohorts in this study.

Figure 1.

A schema of cohorts in this study.

Figure 2.

Repeated COVID-19 vaccination correlates with poor prognosis of PC. (a) Kaplan–Meier analysis from 2018 to 2023 in Cohort A by year. (b) Kaplan–Meier analysis of 272 PC patients in Cohort A (Log-rank test, P = 0.019, median 11.2 months vs. median 14.1 months). (c) Kaplan–Meier analysis of 223 PC patients with known vaccination history in Cohort A. (Log-rank test, P = 0.006, median 10.3 months vs. median 14.9 months). (d) Kaplan–Meier analysis of 96 PC patients after propensity score matching for TNM factors, surgery, and chemotherapy in Cohort A (Log-rank test, P = 0.038, median 11.2 months vs. median 14.2 months).

Figure 2.

Repeated COVID-19 vaccination correlates with poor prognosis of PC. (a) Kaplan–Meier analysis from 2018 to 2023 in Cohort A by year. (b) Kaplan–Meier analysis of 272 PC patients in Cohort A (Log-rank test, P = 0.019, median 11.2 months vs. median 14.1 months). (c) Kaplan–Meier analysis of 223 PC patients with known vaccination history in Cohort A. (Log-rank test, P = 0.006, median 10.3 months vs. median 14.9 months). (d) Kaplan–Meier analysis of 96 PC patients after propensity score matching for TNM factors, surgery, and chemotherapy in Cohort A (Log-rank test, P = 0.038, median 11.2 months vs. median 14.2 months).

Figure 3.

IgG4 is a negative prognostic factor in PC patients. (a) Kaplan–Meier analysis of 96 PC patients with known vaccination history and measured IgG4 levels in Cohort A (Log-rank test, P < 0.001, median 10.3 months vs. median 20.8 months). (b) Comparison of total IgG4 levels by number of vaccinations in 96 PC patients of Cohort A (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.025, ≥ 3 vaccinations vs. 0–2 vaccinations). (c) Kaplan–Meier analysis in PC patients with IgG4 test in Cohort A. (*Log-rank test, P = 0.076 and Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test, P = 0.042, IgG4-high group vs. IgG4-low group, cutoff value for IgG4 is 48 mg/dL) (d) Representative images of PC tissues (white arrowheads: tumor cells) with Foxp3-positive lymphocytes (black arrows). A square frame (100 µm x 100 µm) was used to measure the number of Foxp3-positive cells / total cell counts. (e) Comparison of Foxp3-positive cells / total cell counts by number of vaccinations (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.044, ≥ 3 vaccinations vs. 0–2 vaccinations). (f) Comparison of Foxp3 positive cells / total cell counts between high and low serum IgG4 groups (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.005, cutoff value for IgG4 is 48 mg/dL). PC, pancreatic cancer.

Figure 3.

IgG4 is a negative prognostic factor in PC patients. (a) Kaplan–Meier analysis of 96 PC patients with known vaccination history and measured IgG4 levels in Cohort A (Log-rank test, P < 0.001, median 10.3 months vs. median 20.8 months). (b) Comparison of total IgG4 levels by number of vaccinations in 96 PC patients of Cohort A (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.025, ≥ 3 vaccinations vs. 0–2 vaccinations). (c) Kaplan–Meier analysis in PC patients with IgG4 test in Cohort A. (*Log-rank test, P = 0.076 and Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test, P = 0.042, IgG4-high group vs. IgG4-low group, cutoff value for IgG4 is 48 mg/dL) (d) Representative images of PC tissues (white arrowheads: tumor cells) with Foxp3-positive lymphocytes (black arrows). A square frame (100 µm x 100 µm) was used to measure the number of Foxp3-positive cells / total cell counts. (e) Comparison of Foxp3-positive cells / total cell counts by number of vaccinations (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.044, ≥ 3 vaccinations vs. 0–2 vaccinations). (f) Comparison of Foxp3 positive cells / total cell counts between high and low serum IgG4 groups (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.005, cutoff value for IgG4 is 48 mg/dL). PC, pancreatic cancer.

Figure 4.

Total IgG4, along with spike-specific IgG4, is increased in patients with repeated COVID-19 vaccination. (a) Measurement of spike-specific IgGs in Cohort B using ELISA. (b) Comparison of spike-specific IgGs. values between types of diseases. There was no significant difference in the spike-specific IgGs levels between the disease types. (c) Comparison of spike-specific IgGs values based on the numbers of vaccinations. Spike-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG4 levels increased in the groups that were vaccinated more than three times (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.05, vs. 0–2 vaccinations) (d, e) Correlation plot of the total IgG4 and spike-specific IgG4 in all cases (R2 = 0.27, p < 0.001) (d) and PC cases (R2 = 0.38, p = 0.011) (e). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PC, pancreatic cancer.

Figure 4.

Total IgG4, along with spike-specific IgG4, is increased in patients with repeated COVID-19 vaccination. (a) Measurement of spike-specific IgGs in Cohort B using ELISA. (b) Comparison of spike-specific IgGs. values between types of diseases. There was no significant difference in the spike-specific IgGs levels between the disease types. (c) Comparison of spike-specific IgGs values based on the numbers of vaccinations. Spike-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG4 levels increased in the groups that were vaccinated more than three times (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.05, vs. 0–2 vaccinations) (d, e) Correlation plot of the total IgG4 and spike-specific IgG4 in all cases (R2 = 0.27, p < 0.001) (d) and PC cases (R2 = 0.38, p = 0.011) (e). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PC, pancreatic cancer.

Table 1.

Characteristics of pancreatic cancer patients in Cohort A (n = 272).

Table 1.

Characteristics of pancreatic cancer patients in Cohort A (n = 272).

| |

All Case

(n=272) |

2018-2021

(n=186) |

2022-2023

(n=86) |

p-value |

| Age (mean±SD) |

70.9 ± 9.6 |

70.9 ± 9.6 |

70.5 ± 9.9 |

n.s.a |

| Age ≥75, no. (%) |

103 (37.9) |

71 (38.2) |

32 (37.2) |

n.s.b |

| Female, no. (%) |

133 (48.9) |

92 (49.5) |

41 (47.7) |

n.s.b |

| PS ≥ 2, no. (%) |

42 (15.4) |

27 (14.5) |

15 (17.4) |

n.s.b |

| Jaundice, no. (%) |

92 (33.8) |

63 (33.9) |

29 (33.7) |

n.s.b |

| Diabetes Mellites, no. (%) |

144 (52.9) |

97 (52.2) |

47 (54.7) |

n.s.b |

| Location (head), no. (%) |

126 (46.3) |

90 (48.4) |

36 (41.9) |

n.s.b |

| UICC TNM classification |

|

|

|

|

| T (3-4), no. (%) |

148 (54.4) |

95 (51.1) |

53 (61.6) |

n.s.b |

| N, no. (%) |

144 (52.9) |

97 (52.2) |

47 (54.7) |

n.s.b |

| M, no. (%) |

146 (53.7) |

97 (52.2) |

49 (57.0) |

n.s.b |

| Surgery, no. (%) |

61 (22.4) |

51 (27.4) |

10 (11.6) |

0.005b |

| Chemotherapy, no. (%) |

201 (73.9) |

140 (75.3) |

61 (70.9) |

n.s.b |

COVID-19 mRNA

≥ 3 vaccinations

(Yes/No/unknown) |

51/190/31 |

0/186/0 |

51/4/31 |

<0.001b |

Number of vaccination

(3/4/5/6/7) |

12/8/19/9/3 |

- |

12/8/19/9/3 |

|

CEA median

(min-max) ng/mL |

4.8

(0.6-2660.6)

|

4.6

(0.6-2205.1)

|

5.1

(0.6-2660.6)

|

n.s.a |

| CEA ≥10, no. (%) |

77 (28.3) |

55 (29.6) |

22 (25.6) |

n.s.b |

CA19-9 median

(min-max) U/mL |

442.0

(0-150000)

|

449.0

(0-150000)

|

450.2

(0-150000)

|

n.s.a |

| CA19-9 ≥500, no. (%) |

132 (48.5) |

90 (48.4) |

42 (48.8) |

n.s.b |

| a Mann–Whitney test. b Fisher’s exact test. |

| PC, pancreatic cancer. PS, performance status. |

| CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen. CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9. |

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards analysis of factors affecting the prognosis of pancreatic cancer (n = 272).

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards analysis of factors affecting the prognosis of pancreatic cancer (n = 272).

| |

HR |

95%CI |

p-value

(Univariate) |

| Age ≥75 |

0.94 |

(0.71-1.23) |

n.s. |

| Sex (Female/Male) |

1.15 |

(0.88-1.50) |

n.s. |

| PS ≥ 2 |

2.66 |

(1.85-3.74) |

<0.001 |

| Jaundice (Yes/No) |

1.49 |

(1.12-1.97) |

0.005 |

| Diabetes Mellites (Yes/No) |

0.77 |

(0.59-1.00) |

n.s. |

| Location (head/body-tail) |

0.95 |

(0.73-1.24) |

n.s. |

| UICC TNM classification |

|

|

|

| T (3-4/1-2) |

2.31 |

(1.76-3.05) |

<0.001 |

| N (Yes/No) |

1.57 |

(1.22-2.00) |

<0.001 |

| M (Yes/No) |

3.88 |

(2.92-5.19) |

<0.001 |

| Surgery (Yes/No) |

0.19 |

(0.13-0.28) |

<0.001 |

| Chemotherapy (Yes/No) |

0.58 |

(0.43-0.79) |

<0.001 |

COVID-19 mRNA

≥ 3 vaccinations (Yes/No) |

1.72 |

(1.15-2.51) |

0.006 |

| CEA >10 (ng/mL) |

2.06 |

(1.54-2.73) |

<0.001 |

| CA19-9 >500 (U/mL) |

2.04 |

(1.56-2.69) |

<0.001 |

| PC, pancreatic cancer. PS, performance status. |

| CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen. CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9. |

Table 3.

Characteristics of 223 PC patients with vaccination history information in Cohort A.

Table 3.

Characteristics of 223 PC patients with vaccination history information in Cohort A.

| |

Before Matching |

After Matching |

| |

0-2

vaccinations

(n=172) |

≥ 3

vaccinations

(n=51) |

p-value |

0-2

vaccinations

(n=48) |

≥ 3

vaccinations

(n=48) |

p-

value |

| Age (mean±SD) |

70.6 ± 9.7 |

71.4 ± 9.3 |

n.s.a |

69.8 ± 9.5 |

71.4 ± 9.2 |

n.s.a |

| Age ≥75, no. (%) |

65 (37.8) |

23 (45.1) |

n.s.b |

16 (33.3) |

21 (43.8) |

n.s.b |

| Female, no. (%) |

84 (48.8) |

25 (49.0) |

n.s.b |

24 (50.0) |

23 (47.9) |

n.s.b |

| PS ≥ 2, no. (%) |

20 (11.6) |

11 (21.6) |

n.s.b |

8 (16.7) |

11 (22.9) |

n.s.b |

| Jaundice, no. (%) |

60 (34.9) |

21 (41.2) |

n.s.b |

15 (31.3) |

18 (37.5) |

n.s.b |

| Diabetes Mellites, no. (%) |

84 (48.8) |

29 (56.9) |

n.s.b |

28 (58.3) |

28 (58.3) |

n.s.b |

| Location (head), no. (%) |

87 (50.6) |

24 (47.1) |

n.s.b |

22 (45.8) |

21 (43.8) |

n.s.b |

| UICC TNM classification |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T(3-4), no. (%) |

85 (49.4) |

33 (64.7) |

n.s.b |

30 (62.5) |

30 (62.5) |

n.s.b |

| N, no. (%) |

90 (52.3) |

30 (58.8) |

n.s.b |

29 (60.4) |

29 (60.4) |

n.s.b |

| M, no. (%) |

89 (51.7) |

30 (58.8) |

n.s.b |

28 (58.3) |

28 (58.3) |

n.s.b |

| Surgery, no. (%) |

48 (27.9) |

7 (13.7) |

0.043b |

7 (14.6) |

7 (14.6) |

n.s.b |

| Chemotherapy, no. (%) |

128 (74.4) |

33 (64.7) |

n.s.b |

33 (68.8) |

33 (68.8) |

n.s.b |

| CEA ≥10, no. (%) |

50 (29.1) |

10 (19.6) |

n.s.b |

16 (33.3) |

9 (18.8) |

n.s.b |

| CA19-9 ≥500, no. (%) |

82 (47.7) |

25 (49.0) |

n.s.b |

26 (54.2) |

22 (45.8) |

n.s.b |

| IgG4 measurement, no. (%) |

47 (27.3) |

49 (96.1) |

<0.001b |

11 (22.9) |

46 (93.9) |

<0.001b |

| IgG4 (mean ± SD) |

38.6 ± 31.7 |

54.7 ± 37.0 |

0.025a |

44.2 ± 16.5 |

53.6 ± 36.8 |

n.s.a |

Table 4.

Characteristics of pancreatic cancer patients in Cohort A (n = 96).

Table 4.

Characteristics of pancreatic cancer patients in Cohort A (n = 96).

| |

Patients

(n=96) |

0-2

vaccinations

(n=47) |

≥ 3

vaccination

(n=49) |

p-value |

| Age (mean±SD) |

71.4 ± 8.2 |

70.9 ± 9.6 |

70.9 ± 9.6 |

n.s.a |

| Age ≥75, no. (%) |

37 (38.5) |

15 (31.9) |

22 (44.9) |

n.s.b |

| Female, no. (%) |

50 (52.1) |

26 (55.3) |

24 (49.0) |

n.s.b |

| PS ≥ 2, no. (%) |

14 (14.6) |

4 (8.5) |

10 (20.4) |

n.s.b |

| Jaundice, no. (%) |

40 (41.7) |

19 (40.4) |

21 (42.9) |

n.s.b |

| Diabetes Mellites, no. (%) |

53 (55.2) |

25 (53.2) |

28 (57.1) |

n.s.b |

| Location (head), no. (%) |

55 (57.3) |

31 (66.0) |

24 (49.0) |

n.s.b |

| UICC TNM classification |

|

|

|

|

| T(3-4), no. (%) |

44 (45.8) |

13 (27.7) |

31 (63.3) |

<0.001b |

| N, no. (%) |

47 (49.0) |

18 (38.3) |

29 (59.2) |

0.045b |

| M, no. (%) |

41 (42.7) |

12 (25.5) |

29 (59.2) |

0.001b |

| Surgery, no. (%) |

30 (31.3) |

23 (48.9) |

7 (14.3) |

<0.001b |

| Chemotherapy, no. (%) |

67 (69.8) |

36 (76.6) |

31 (63.3) |

n.s.b |

| CEA ≥10, no. (%) |

15 (15.6) |

6 (12.8) |

9 (18.4) |

n.s.b |

| CA19-9 ≥500, no. (%) |

40 (41.7) |

15 (31.9) |

25 (51.0) |

n.s.b |

| Other factors |

|

|

|

|

| NLR (mean ± SD) |

3.8 ± 2.5 |

3.0 ± 1.2 |

4.5 ± 3.2 |

0.008a |

| NLR ≥2.82, no. (%) |

57 (59.4) |

21 (44.7) |

36 (73.5) |

0.007b |

| mGPS (0/1/2) |

68/19/9 |

36/8/3 |

32/11/6 |

n.s.b |

| mGPS ≥1, no. (%) |

28 (29.2) |

11 (23.4) |

17 (34.7) |

n.s.b |

| PNI (mean ± SD) |

45.7 ± 5.4 |

47.3 ± 5.2 |

44.2 ± 5.3 |

0.002a |

| PNI ≥46.8, no. (%) |

41 (42.7) |

28 (59.6) |

13 (26.5) |

0.002b |

| IgG4 (mean ± SD) |

46.8 ± 35.3 |

38.6 ± 31.7 |

54.7 ± 37.0 |

0.025a |

| IgG4 ≥48 mg/dL, no. (%) |

35 (36.5) |

12 (25.5) |

23 (46.9) |

0.035b |

| a Mann–Whitney test. b Fisher’s exact test. |

| PC, pancreatic cancer. PS, performance status. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen. CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9. |

| NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio. mGPS, modified Glasgow prognostic score. PNI, prognostic nutritional index. |

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazards analysis of factors affecting the prognosis of pancreatic cancer (n = 96).

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazards analysis of factors affecting the prognosis of pancreatic cancer (n = 96).

| |

HR |

95%CI |

Univariate

p-value |

Multivariate

p-value |

| Age ≥75 |

0.83 |

(0.49-1.36) |

n.s. |

|

| Sex (Female/Male) |

1.15 |

(0.71-1.88) |

n.s. |

|

| PS ≥ 2 |

9.92 |

(4.70-20.5) |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| Jaundice (Yes/No) |

2.01 |

(1.23-3.30) |

0.006 |

0.011 |

| Diabetes Mellites(Yes/No) |

0.92 |

(0.57-1.49) |

n.s. |

|

| Location (head/body-tail) |

1.39 |

(0.85-2.31) |

n.s. |

|

| UICC TNM classification |

|

|

|

|

| T (3-4/1-2) |

2.40 |

(1.47-3.95) |

<0.001 |

n.s. |

| N (Yes/No) |

1.81 |

(1.12-2.97) |

0.017 |

n.s. |

| M (Yes/No) |

4.52 |

(2.74-7.54) |

<0.001 |

0.010 |

| Surgery (Yes/No) |

0.19 |

(0.10-0.35) |

<0.001 |

0.011 |

| Chemotherapy (Yes/No) |

0.57 |

(0.34-0.97) |

0.033 |

0.035 |

COVID-19 mRNA

≥ 3 vaccinations (Yes/No) |

4.08 |

(2.25-7.59) |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

| CEA >10 (ng/mL) |

2.87 |

(1.53-5.13) |

<0.001 |

0.009 |

| CA19-9 >500 (U/mL) |

2.44 |

(1.48-4.03) |

<0.001 |

n.s. |

| NLR ≥ 2.82 |

2.04 |

(1.24-3.41) |

0.006 |

n.s. |

| mGPS ≥ 1 |

1.67 |

(0.99-2.76) |

0.049 |

n.s. |

| PNI ≥ 46.8 |

0.35 |

(0.20-0.58) |

<0.001 |

n.s. |

| IgG4 ≥ 48 (mg/dL) |

1.57 |

(0.94-2.57) |

0.079 |

n.s. |

| PC, pancreatic cancer. PS, performance status. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen. CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9. |

| NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio. mGPS, modified Glasgow prognostic score. PNI, prognostic nutritional index. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).